Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Voyage Plan Execution Monitoring and Charyt Correction

Voyage Plan Execution Monitoring and Charyt Correction

Uploaded by

Joseph GraciousCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- United States Coast Guard: Situational Awareness ExerciseDocument20 pagesUnited States Coast Guard: Situational Awareness ExerciseOllie Evans100% (1)

- 1 Using This Training PackageDocument16 pages1 Using This Training PackageГерман ЯковлевNo ratings yet

- Hydrodynamics & InteractionDocument33 pagesHydrodynamics & InteractionIoana Johanna Cristea100% (1)

- Train The TrainerDocument144 pagesTrain The TrainerjaffersheriffNo ratings yet

- 'Report A Near-Miss - Save A Life' ReferenceDocument38 pages'Report A Near-Miss - Save A Life' ReferenceJoseph Gracious100% (1)

- Hfpa Chapter 4Document27 pagesHfpa Chapter 4Mehroob CheemaNo ratings yet

- Bridge Team Management: Situational AwarenessDocument64 pagesBridge Team Management: Situational AwarenessZitouni FodhilNo ratings yet

- The Mariner Maritme LawDocument113 pagesThe Mariner Maritme LawBi OfficialNo ratings yet

- Team Management Introduction 9Document9 pagesTeam Management Introduction 9ilgarNo ratings yet

- Information Processing Situational AwarenessDocument25 pagesInformation Processing Situational AwarenessZahid AbbasNo ratings yet

- Management 1Document4 pagesManagement 1Brendan Rezz R CilotNo ratings yet

- 2ndyear Unit 1 Lecture 6Document22 pages2ndyear Unit 1 Lecture 6Chellali RabahNo ratings yet

- Flight Safety Article FLT LT SoumitraDocument4 pagesFlight Safety Article FLT LT SoumitraSälmän Md ÄhsänNo ratings yet

- Expect The Unexpected: Evidence-Based TrainingDocument4 pagesExpect The Unexpected: Evidence-Based Trainingdionicio perezNo ratings yet

- 12Document20 pages12Maureen Janelle RemaneaNo ratings yet

- 3 Resume Harvard Business ReviewDocument6 pages3 Resume Harvard Business Reviewana.alantariganNo ratings yet

- FC Training 101Document3 pagesFC Training 101GS HNo ratings yet

- Five Techniques The Navy SEALs Use For Crisis Management.Document6 pagesFive Techniques The Navy SEALs Use For Crisis Management.Ivan Cruz (Navi Zurc)No ratings yet

- Situation Awareness and Its Practical Application in Maritime DomainDocument3 pagesSituation Awareness and Its Practical Application in Maritime DomainNdi Mvogo100% (1)

- Safety Behaviours Human Factor For Pilots 9 Human Information ProcessingDocument24 pagesSafety Behaviours Human Factor For Pilots 9 Human Information ProcessingSonya McSharkNo ratings yet

- Work Learning In: Practices Used in The U.S. Army Can Be Applied To Processes in Your OfficeDocument1 pageWork Learning In: Practices Used in The U.S. Army Can Be Applied To Processes in Your Officeoscar_pinillosNo ratings yet

- Understanding Human DowntimeDocument3 pagesUnderstanding Human DowntimesabahatmohammedNo ratings yet

- ACE Handout May'23Document178 pagesACE Handout May'23ganesh dabholeNo ratings yet

- The Complete Guide To MemoryDocument50 pagesThe Complete Guide To MemoryAllanNo ratings yet

- Leadership and Worker Involvement ToolkitDocument2 pagesLeadership and Worker Involvement Toolkitdarkot1234No ratings yet

- Airbussafetylib FLT Ops Hum Per Seq06Document11 pagesAirbussafetylib FLT Ops Hum Per Seq06Jose RicardoNo ratings yet

- IMCAD036 (Apr 2016) Neurological Assessment of A Diver (14849)Document8 pagesIMCAD036 (Apr 2016) Neurological Assessment of A Diver (14849)Michael NicolichNo ratings yet

- ACE Handout Apr 2022Document176 pagesACE Handout Apr 2022ChinsNo ratings yet

- The Kinogram MethodDocument36 pagesThe Kinogram Methodanon_371204808100% (3)

- Cert Ig Unit6 Jan20114Document73 pagesCert Ig Unit6 Jan20114testNo ratings yet

- Chapter 9 CP Foot TechniquesDocument72 pagesChapter 9 CP Foot TechniquesmarceloNo ratings yet

- Training To Enhance Sutuational AwarenessDocument4 pagesTraining To Enhance Sutuational AwarenessEzell DeLoachNo ratings yet

- TRBC Manual - Fourth Edition - 090408 PDFDocument128 pagesTRBC Manual - Fourth Edition - 090408 PDFMatheus Baños100% (1)

- Dashboard Design WhitePaper StephenFew PDFDocument23 pagesDashboard Design WhitePaper StephenFew PDFfiomaravilhaNo ratings yet

- Solution Manual For Cognitive Psychology Connecting Mind Research and Everyday Experience 5th Edition e Bruce GoldsteinDocument23 pagesSolution Manual For Cognitive Psychology Connecting Mind Research and Everyday Experience 5th Edition e Bruce GoldsteinAngelKelleycfayo100% (93)

- C4 Smeac 6523Document13 pagesC4 Smeac 6523lawtonjake100% (1)

- Steve Jobs: How To Make Faster Decisions: Discover The Skills He Used To Achieve This On A Daily BasisFrom EverandSteve Jobs: How To Make Faster Decisions: Discover The Skills He Used To Achieve This On A Daily BasisNo ratings yet

- Part IIDocument64 pagesPart IIVLONENo ratings yet

- FACILITATOR GUIDE: "It Will Never Happen To Me!": Part A - Preparation For The SessionDocument6 pagesFACILITATOR GUIDE: "It Will Never Happen To Me!": Part A - Preparation For The SessionNicolas BernardNo ratings yet

- Swimming 101 Pre Course WorkbookDocument6 pagesSwimming 101 Pre Course Workbookplpymkzcf100% (2)

- Memory and Learning: The Path To UnderstandingDocument17 pagesMemory and Learning: The Path To UnderstandingDavid HansonNo ratings yet

- DailySafetyMessages PDFDocument3 pagesDailySafetyMessages PDFvkumaranNo ratings yet

- SCIO Manual Ver 12-12-12 SampleDocument10 pagesSCIO Manual Ver 12-12-12 SampleGábor GörfölNo ratings yet

- Special Topic KnowledgeDocument22 pagesSpecial Topic KnowledgecangXXNo ratings yet

- Critical Situations in Dynamic PositioningDocument4 pagesCritical Situations in Dynamic PositioningOrlando QuevedoNo ratings yet

- Preparing For Your OSCE Examination NMC - Test of CompetenceDocument13 pagesPreparing For Your OSCE Examination NMC - Test of CompetenceSteve100% (2)

- Ebook - Funnel - Self Defense - The Fundamental Concepts To Master Before Any Technique Ebook - VOLUME 1.Document49 pagesEbook - Funnel - Self Defense - The Fundamental Concepts To Master Before Any Technique Ebook - VOLUME 1.Jeet Kune DoNo ratings yet

- Bulletproof Memory The Ultimate Hacks to Unlock Hidden Powers of Mind and MemoryFrom EverandBulletproof Memory The Ultimate Hacks to Unlock Hidden Powers of Mind and MemoryNo ratings yet

- 2 CRMDocument24 pages2 CRMrozhinhadi63No ratings yet

- Student WorkbookDocument28 pagesStudent WorkbookmkdkdNo ratings yet

- Leadership / Followership: Instructor ManualDocument108 pagesLeadership / Followership: Instructor ManualAINA SAMNo ratings yet

- Boost Your Memory: Simple and effective techniques to improve your memoryFrom EverandBoost Your Memory: Simple and effective techniques to improve your memoryNo ratings yet

- Microlearning Its Not What You Think It Is EbookDocument41 pagesMicrolearning Its Not What You Think It Is Ebookhim2000himNo ratings yet

- The Importance of Near Miss Reporting - What You Need To KnowDocument6 pagesThe Importance of Near Miss Reporting - What You Need To KnowaneethavilsNo ratings yet

- Studywise Brain Hacking - 2020Document37 pagesStudywise Brain Hacking - 2020Cristian LermaNo ratings yet

- Provide First AidDocument23 pagesProvide First AidKenard100% (6)

- Unit5 LightSearchRescueOperationsDocument34 pagesUnit5 LightSearchRescueOperationsiBooq100% (1)

- Carrier: Xpressbees: Deliver To FromDocument2 pagesCarrier: Xpressbees: Deliver To FromJoseph GraciousNo ratings yet

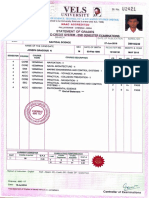

- BNS Semester - 1Document1 pageBNS Semester - 1Joseph GraciousNo ratings yet

- BNS Semester - 4Document1 pageBNS Semester - 4Joseph GraciousNo ratings yet

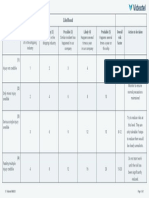

- Risk MatrixDocument1 pageRisk MatrixJoseph GraciousNo ratings yet

- Prevention and Reaction To Marine Oil Spills Marpol Annex 3Document28 pagesPrevention and Reaction To Marine Oil Spills Marpol Annex 3Joseph GraciousNo ratings yet

- Chenna: Choice Based Credit System-End SemesterDocument1 pageChenna: Choice Based Credit System-End SemesterJoseph GraciousNo ratings yet

- 'Report A Near-Miss - Save A Life' ReferenceDocument38 pages'Report A Near-Miss - Save A Life' ReferenceJoseph Gracious100% (1)

- Port State ControlDocument20 pagesPort State ControlJoseph Gracious100% (1)

- Cyber Security at SeaDocument30 pagesCyber Security at SeaJoseph GraciousNo ratings yet

- Background of The StudyDocument33 pagesBackground of The StudyTerrence MateoNo ratings yet

- Needs Analysis by Seedhouse PDFDocument7 pagesNeeds Analysis by Seedhouse PDFjuliaayscoughNo ratings yet

- 0 Test PredictivviithDocument3 pages0 Test PredictivviithmirabikaNo ratings yet

- Enghl p2 Gr11 Memo Nov2020Document21 pagesEnghl p2 Gr11 Memo Nov2020Rebecca GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Unit 9 General TestDocument7 pagesUnit 9 General TestNgoc VanNo ratings yet

- Converting Roman Numerals (A) : MMCXXXV MMDCCXXDocument20 pagesConverting Roman Numerals (A) : MMCXXXV MMDCCXXLobinhaNo ratings yet

- Remember (AhmadYosi) (11IPA1)Document3 pagesRemember (AhmadYosi) (11IPA1)Yona NiNo ratings yet

- MallDocument22 pagesMallZee ZeeNo ratings yet

- How To Motivate Students in Learning English As A Second LanguageDocument2 pagesHow To Motivate Students in Learning English As A Second LanguagebulliinaNo ratings yet

- Consonant Phoneme Chart PDFDocument19 pagesConsonant Phoneme Chart PDFAnaMaríaMorónOcaña100% (1)

- Class - 5 AYAT 1Document9 pagesClass - 5 AYAT 1Tasharif AnsariNo ratings yet

- Assignment - Unit 2 The Study of English: Pronunciation: Intonation, Stress and SoundsDocument12 pagesAssignment - Unit 2 The Study of English: Pronunciation: Intonation, Stress and SoundsSneha JaniNo ratings yet

- Command of EvidenceDocument105 pagesCommand of EvidenceHye Yun LeeNo ratings yet

- Germanic MagicDocument1 pageGermanic MagicoldwyrdthreadNo ratings yet

- The 50 Most Common Irregular VerbsDocument6 pagesThe 50 Most Common Irregular VerbsDaniela BecerraNo ratings yet

- Different Types of NounsDocument4 pagesDifferent Types of NounsSweeqin OoiNo ratings yet

- NataliaDocument5 pagesNataliaMocian Georgeta-MihaelaNo ratings yet

- Alex Byrne - Fact and ValueDocument236 pagesAlex Byrne - Fact and Valuewaarghgarble100% (1)

- Module-1 - Commn ErrorsDocument53 pagesModule-1 - Commn ErrorsSoundarya T j100% (1)

- An Introduction To C++ TraitsDocument6 pagesAn Introduction To C++ TraitsSK_shivamNo ratings yet

- DLL English 10 Q1 - WK 2 - Pre-Assessment - Nick Vucijic - 2019-2020Document7 pagesDLL English 10 Q1 - WK 2 - Pre-Assessment - Nick Vucijic - 2019-2020Jennifer L. Magboo-Oestar100% (1)

- Elizabeth Povinelli - Radical WorldsDocument16 pagesElizabeth Povinelli - Radical WorldsEric WhiteNo ratings yet

- Улсын шалгалт 12р анги 1Document70 pagesУлсын шалгалт 12р анги 1TrixelizedNo ratings yet

- Online Job Portal SystemDocument10 pagesOnline Job Portal SystemArvind singh0% (1)

- G9-English WLPDocument4 pagesG9-English WLPDada Lanuang IgnacioNo ratings yet

- English IDIOMSDocument25 pagesEnglish IDIOMSMarlene Tagavilla-Felipe DiculenNo ratings yet

- Dia Lesson 1 Intro Concepts and MethodsDocument6 pagesDia Lesson 1 Intro Concepts and Methods00laurikaNo ratings yet

- 1 EL 111 - Children and Adolescent As ReadersDocument5 pages1 EL 111 - Children and Adolescent As ReadersAngel RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of English Textbook in Pakistan A Case Study of Punjab Textbook For 9th ClassDocument19 pagesEvaluation of English Textbook in Pakistan A Case Study of Punjab Textbook For 9th ClassMadiha ShehryarNo ratings yet

Voyage Plan Execution Monitoring and Charyt Correction

Voyage Plan Execution Monitoring and Charyt Correction

Uploaded by

Joseph GraciousCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Voyage Plan Execution Monitoring and Charyt Correction

Voyage Plan Execution Monitoring and Charyt Correction

Uploaded by

Joseph GraciousCopyright:

Available Formats

CONTENTS

1 Using this training package

1.1 Learning the training material

1.2 Situational Awareness

1.3 Learning objectives

2 Executing the voyage plan

3 Monitoring the voyage plan

3.1 How is the voyage plan used after departure?

3.2 What do you do when you encounter traffic?

4 Working with VTS

4.1 What happens on approaching or leaving a port?

4.2 How best to communicate with VTS

5 Updating charts

5.1 How best to update charts

5.2 Route monitoring

5.3 Good resource management and the voyage plan

6 Conclusions

7 Further resources

8 Appendix: ALRS volume numbers

© MMXVII KVH Videotel

1 USING THIS TRAINING PACKAGE

Within this Reference there are two devices to help students learn. Firstly, there is the

NOTE which will provide more detail about the subject in question. Secondly, there will

be the more directed EXERCISE which will ask you to apply your knowledge in

practical ways. We hope this will increase your confidence and skills in real life work

situations.

1.1 Learning the training material

If you are responsible for training others then you should aim to follow the instructions

in this section as closely as possible. It will help you to learn how to run effective

training sessions with the crew.

First, read the preliminary section on the principles of situational awareness. As

this approach informs the whole series, it is important to familiarise yourself

with its key concepts and ideas. We will be referring to them throughout.

For each video:

1 Ensure you have watched it all. This does not mean watching the entire video

without pausing – indeed we want to encourage you to use the pause function

where indicated. However, we do feel it is important that you finish one video

before moving onto the next.

2 As you watch, make notes of any areas you feel unsure about or need further

clarification.

3 Consult this Reference. Does it give you the information you need? If not, do

you know where to go to find it?

4 Throughout each part, questions are raised for discussion. Make notes if

necessary.

5 Make a special note of what you feel are the most important learning

objectives for each Reference. These are outlined at the beginning of each

part, but may vary according to the different demands of the crew you are

teaching.

6 Discuss and answer the questions that arise from the case study in some of

the parts. In particular discuss how the conclusions you have reached about

the case study relate to your own ship.

NOTES

You do not have to work through the entire Reference in one sitting. In fact, the case

studies for each part are self-contained, so you can take them separately if you so

wish. However, it is helpful that you read this Reference first.

The content on situational awareness that follows is common to each Reference. We

recommend that, unless you are doing the eight-part training course in one day, you

go through this section each time you come to it, in order to refresh your memory.

© MMXVII KVH Videotel

NOTES

You do not have to work through the entire Reference in one sitting. In fact, the case

studies for each part are self-contained, so you can take them separately if you so

wish. However, it is helpful that you read this Reference first.

The content on situational awareness that follows is common to each Reference. We

recommend that, unless you are doing the eight-part training course in one day, you

go through this section each time you come to it, in order to refresh your memory.

EXERCISE

Look at the graphic above. What do you think is the relationship

between the three different activities - LOOK/THINK/ANTICIPATE?

Write down your response and compare it to the following

description of situational awareness.

1.2 Situational awareness

What is situational awareness?

Situational awareness is a strategy designed to help you make better decisions.

Situational awareness was first developed by the aviation industry to help

airline pilots improve their decision making.

Situational awareness helps to improve mental anticipation of events, giving us

a more systematic way to be aware of our progress in a specific environment.

Situational awareness is included in the Seafarers’ Training, Certification and

Watchkeeping (STCW) Code, 2010, as a key proficiency for all officers in

charge of navigation watch and/or engine room.

Situational awareness can be defined very simply: recognising and responding

to what is going on around you.

Situational awareness draws on three essential activities:

© MMXVII KVH Videotel

1 Gathering information

2 Interpreting information

3 Anticipating a future state

NOTE

Another way of conceiving situational awareness is through three simple questions:

1 Gathering information – What?

2 Interpreting information – So what?

3 Anticipating future states – Now what?

Write those down somewhere convenient and refer to them if necessary.

EXERCISE

Now look at the graphic above again. What do you conclude from

the relationship between the three activities? It’s what we call a

virtuous circle, when one stage leads naturally onto the other to

become a natural flow.

One such example from our daily life would be the skills we

demonstrate in driving safely and efficiently. Can you think of another

example in your own work?

Why do we need better situational awareness?

Our perception of reality can become distorted when we are stressed and overloaded

with sensory information, such as in an emergency. In order to cope with a sudden

flood of data, the brain becomes selective, filtering out information that appears safe to

ignore in order to concentrate on what seems most important. This filtering process

involves assumptions about the way things will probably turn out, based on previous

experience. That is where the danger lies.

Another factor in creating this perception is the way our memory is linked. We have

three kinds of memory:

1 Sensory Memory. This holds information for brief periods of time.

2 Working Memory. This has a limited capacity to store information and is

vulnerable to distraction. Once distracted, it is difficult to return to the task

and to retain that information.

3 Long Term Memory. This holds all the information you have acquired during

your life, including your store of knowledge.

In good situational awareness, you are retrieving information stored in Long Term

Memory and transferring it into Working Memory. Ideally, it helps build our risk

perception into a smooth stream of attention concentrated on avoiding danger long

© MMXVII KVH Videotel

before the event occurs. It also helps to prevent those bad habits that can creep into

our work practice and replace them with better ones.

NOTE

In recent years, the amount of information available to the bridge watchkeeping

officer has multiplied, with electronic charts and Automatic Identification Systems

(AIS). All this has had a positive effect on situational awareness.

Sometimes it seems the hardest part now is not evaluating the information provided

by the navigational instruments, but predicting what the other ship is going to do.

Remember – just looking up and out of the bridge window can give you an

immediate awareness. And do not forget to look abaft the beam.

How to improve your situational awareness

1 WHAT?

Gather information. Understand what you need to be aware of on the bridge, on

board, or in the engine room. Understand also the means by which you gather

that information. Where can those resources be found in any given bridge

and/or engine room?

NOTE

Make a rough list of all the instrumentation available to you on board a typical ship.

Exactly what is that instrumentation?

How might that instrumentation help you gather the information you need? How

might it prevent you?

2 SO WHAT?

Process that information you have now gathered and assess it. Remember,

ships operate in a highly dynamic environment and the situation changes all the

time. So might your assessment.

NOTE

All of us have different ways of looking at the world. Remember, as confidence in

interpreting information increases, so does the temptation to work from certain

assumptions.

We have already considered how we use situational awareness in driving. Now think

of the assumptions we often make when driving. How do those assumptions change

according to traffic or weather conditions?

3 NOW WHAT?

Based on your assessment, think about how the situation may develop in the

future and make a decision about any necessary action. Also, consider how

that action might affect your own ship and others.

© MMXVII KVH Videotel

EXERCISE

A lecturer recently wrote ‘One of the toughest things about learning

navigation is the importance of projecting the future position of the

ship. Navigation is about more than just knowing where you are; it is

about knowing where the ship is going and, more critically, are we

heading into danger.’

Do you agree? Write down three reasons that support, and three

that argue against this proposition.

Other factors in situational awareness

In an ideal world the practice of situational awareness would naturally become part of

best practice. Real life, however, has a tendency to dictate otherwise. Whether you

are a trainer planning to use this Reference for training sessions, or a crew member

learning on your own, you will have to consider some of the following factors:

Culture. How will the different nationalities represented on board approach

situational awareness? For example, how aware are you of the different

attitudes of your fellow crew members?

Language. Just how good can communication be when there are a number of

different languages spoken on board? For example, are you aware of the

official language spoken on board? It should be as stated in the company

regulations, mentioned in the Safety Management System (SMS) as well as the

log book.

Leadership styles. How will different leadership styles accommodate situational

awareness? Can you name what those leadership styles are?

NOTE

These factors are sometimes referred to as soft skills.

Soft skills are defined as personal attributes that enhance an individual’s interactions

and job performance. Unlike hard skills which tend to be focused on a certain type of

task or activity, soft skills are broadly applicable.

From theory to practice

In this Introduction, our learning objective was to teach you the theory of

situational awareness. Now you are familiar with both its principles and the way

it operates, you can go on to read the References in whatever order you wish.

By the end of these References we hope that it will have become an integral part

of your own leadership and team working skills.

© MMXVII KVH Videotel

1.3 Learning objectives

What is the best way of carrying out a voyage plan?

In the Reference to Part 2 you were introduced to two of the four stages of the voyage

plan – Appraisal and Planning. These form the preparation part of voyage planning,

which take place before the ship leaves. This also ensures enough time for the

navigating officer and Master to discuss any changes that need to be made, and to

have those changes approved.

NOTE

Remember, voyage planning is mandatory for all ships under the SOLAS and STCW

Conventions. You should already be familiar with this from Part 2. Review it if necessary.

The video you have just watched looks at the other two stages of the voyage plan

process, which show how you put that plan into action. These are execution and

monitoring. Now watch the video again in conjunction with this Reference and you will

understand the importance of:

incorporating any changes in the voyage plan that are needed to accommodate

new circumstances

allocating resources appropriately

fixing your position according to voyage plan requirements

liaising with Vessel Traffic Service (VTS) when necessary

getting the Master’s approval for all changes to the voyage plan

maintaining high levels of situational awareness

EXERCISE

Now you have prepared a voyage plan and are ready to carry it out.

What do you imagine are any additional factors you may need to

take into consideration at this stage?

Make a note of them now and then read them again at the end of

this Reference. It will be interesting to see how they compare.

2 EXECUTING THE VOYAGE PLAN

What about delays in port?

Sometimes there will be delays in port that will affect departure time. As soon as the

departure time is known the plan must be updated and changed if necessary. What

other knock on effects might it have? Here are some examples.

© MMXVII KVH Videotel

Knock on effects

Delay in departure time Consequence

Change of ETA Change in tide heights and flow

Question position fixing accuracy and

Daytime/night time danger points

method

New weather conditions Different choice of route

Consider alternative routes? Save with primary route and use if necessary

Unacceptable hazard, e.g. tidal

Possible evaluation of route

streams

Reallocate resources, e.g. an

Redeployment of key personnel?

extra lookout

Any new factors need to be taken into

Review risk assessment

consideration?

NOTE

If the voyage plan is done on ECDIS, updating it to a revised departure time is

comparatively easy. However, automatic safety checks should be run again.

It is important that you leave enough time to complete this.

EXERCISE

How straightforward do you think it is to revise a voyage plan in the light

of knock on effects due to delay in departure? What in your opinion

would be the easiest thing to change, and what would be the most

difficult? What would be your reasons why?

Make a list and compare it with your colleagues. Is there a consensus

between you?

Pre-departure checklist

Now the voyage plan has now been finalised and approved by the Master, what

happens next? You need to follow your company procedure, which will include but not

be limited to the following:

1. Inform the deck team. Ensure the watchkeeping officers have signed the plan.

2. Prepare the bridge according to company procedure.

3. Check radars and target tracking equipment are switched on, where permitted.

4. Check voyage data recording, echo sounder, navigation lights and sound

signals.

5. Check engine and steering gear.

© MMXVII KVH Videotel

NOTE

Since every ship is different, there may well be items on the list that are specific to your

ship. It is your responsibility to find out what they are.

3 MONITORING THE VOYAGE PLAN

3.1 How is the voyage plan used after departure?

The ship has set off, and the principal task of the watchkeeping officer is to navigate

and monitor the ship’s progress according to the voyage plan, whilst keeping the ship

out of danger. The best kind of voyage plan is one that is adaptable, responding to the

continual flow of new information that informs good situational awareness, and making

any necessary readjustments.

So what helps to maintain this high level of situational awareness? Can you remember the

three key questions we asked in the introduction – What? So What? Now What? If it is

helpful, refer back to that section.

Here is a checklist of watchkeeping tasks, some of which are automatic and some

manual. All of them need to be part of your ongoing work schedule on board.

Task Manual Automatic

Fixing the ship’s position – this is a key task Yes

Check the echo sounder Yes

Monitor helmsman Yes

Check autopilot Yes Yes

Monitor speed to maintain ETA Yes

ECDIS monitoring route – but double check position

Yes

in confined waters by alternative methods

Maintain awareness of immediate hazards on chart Yes

Comparison of actual weather with forecast – if

different then assess whether forecast timing is Yes

wrong

* When initially going over to automatic steering the monitoring is done manually by the

watchkeeping officer to ensure it is following the same course. Even after the

watchkeeping officer is satisfied the autopilot is operating correctly it is still their

responsibility to monitor it.

NOTE

Much emphasis is placed on double checking any information you rely on by using

alternative methods as back up. Remember, an ECDIS screen can give a false

impression of integrity and thus lead to a false sense of security.

© MMXVII KVH Videotel

The simplest and most effective way of double checking with many watchkeeping tasks

is to regularly check navigation marks whilst keeping a continuous visual lookout for

collision avoidance purposes.

EXERCISE

Can you work out a proper procedure for the efficient and effective

execution of the voyage plan, taking into account the tasks outlined in

the table above?

How would that look? How regularly do those tasks need to be

undertaken? And in what order?

Another important aspect of monitoring the voyage plan is position fixing. It is good

practice every time a position is fixed to estimate where the ship will be at the next fix.

This is easy if the position fixing is done at regular intervals. If the next fix coincides

with the estimated position, you can also check that the ship is maintaining its planned

track and speed.

If it does not coincide then something is wrong and the Watchkeeping Officer should

check the estimated position and then the fix.

EXERCISE

Remember, whether you are working with ECDIS or on paper charts

the Watchkeeping Officer must verify the position by alternate position

fixing methods. What would those be?

3.2 What do you do when you encounter traffic?

In coastal waters, one of the situations that occurs whilst watchkeeping is dealing with

traffic. The Convention on the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at

Sea (ColRegs) have established clear rules that govern these situations.

EXERCISE

The priority when altering course and/or speed is the avoidance of close

quarter situations and grounding. How do you imagine a voyage plan

can address this?

NOTE

Remember. Once any hazard has been passed, the watchkeeping officer should get the

ship back on track safely. For further information on both these points, consult the

ColRegs. You can find them via www.imo.org

© MMXVII KVH Videotel

EXERCISE

There will be a lot of highly useful information in the Navigator’s

Workbook or Mariner’s Notes. How do you propose to:

1. Incorporate it into your voyage plan?

2. Enable it to improve your situational awareness?

Write down some suggestions and share them with your colleagues.

4 WORKING WITH VTS

4.1 What happens on approaching or leaving a port?

As watchkeeping officer, some of the most challenging parts of any voyage take place

whilst approaching or leaving a port. It is then that the bridge team will need to interact with

shore based organisations. An important one is the port area Vessel Traffic Service (VTS).

NOTE

Typical VTS systems use radar, VHF radiotelephony and Automatic Identification

Systems (AIS) to keep track of vessel movements and provide navigational safety in a

limited geographical area.

If the pilot is on board, then the pilot is usually the link between VTS and the ship – for

more information read the Reference for Part 6. However, having the pilot on board does

not relieve the bridge team of their responsibilities – so you must be prepared to deal with

the VTS. In coastal waters with no pilot on board, communication with VTS is your

responsibility.

What advantages do the VTS operators have?

They know the area.

They know the planned movements of the ships.

They know the availability and capability of shore-based services.

What kind of service does VTS provide? There are three distinct and different types.

1. Simple information.

2. Navigational assistance.

3. Traffic organization.

NOTE

Details of what is available and in which ports can be found in the Admiralty List of Radio

Signals (ALRS), Volumes 1, 3 and 6.

See Section 8 Appendix for full details.

© MMXVII KVH Videotel

4.2 How best to communicate with VTS

Since a number of key questions will be asked when you first make contact with VTS, it is

vital to ensure that the information used is accurate.

These questions will include:

1. ship’s name

2. call sign

3. draught

4. ETA

5. hazardous cargoes

6 any defects or limitations in the ship’s equipment that could affect

manoeuvrability

7. often also the number of people on board

NOTE

When communicating with VTS or pilot service it is important to keep things brief and to

the point. To aid clarity it is best to ask the agent what information is required and

confirm once they have it – and that it is correct.

Message markers can also be helpful in this context – these are clear statements of

purpose. Message markers are - Instruction, Advice, Warning, Information, Question,

Answer, Request and Intention. State your marker to avoid misunderstanding.

Remember the emphasis on Closed Loop Communication in Part 1. Review if necessary.

Clarity of communication also helps considerably in the case of an emergency. VTS

will be able to alert the relevant emergency service and broadcast warnings to

manage the traffic in the area.

© MMXVII KVH Videotel

5 UPDATING CHARTS

5.1 How best to update charts

Charts can go out of date quickly due to environmental changes such as lights and

buoys, so you need to update them.

The United Kingdom Hydrographic Office (UKHO) has clear guidelines about how to

correct charts, which can be found via www.admiralty.co.uk

ECDIS CHARTS

Electronic charts can be updated by CD Rom. This should be done in port.

Remote updating is also possible if you have access to the internet. Good

records should still be kept.

Manual updating is possible too, but best avoided. It is only to be undertaken if

an immediate update is essential.

PAPER CHARTS

Time consuming and requires close attention.

A potential need to prioritize, starting with current voyage requirements.

Requires right pens, ink and pencils and drawing aids. These are.

o two pens: a .15 millimetre to put in information and a . 25 millimetre to

delete

o violet ink. To be seen in all light

o HB pencil for updating chart correction list

o 7H pencil/compasses for pinpointing positions

o adhesive for sticking corrections in place

o parallel rule and dividers

o compass with pen attachment for drawing circles

o template for drawing symbols

© MMXVII KVH Videotel

EXERCISE

One good way of ensuring you have all the correct equipment to make

the necessary corrections would be to create your own ‘pack’.

How easily can you collect this equipment? Whose responsibility is it to

maintain it?

There is a set procedure based on UKHO guidelines for making corrections on charts:

1. Always start from the correction as detailed in the Notices to Mariners (NMs).

Tracings do save time and help accuracy.

2. Check the previous correction has been done and the chart is up to date. Read

the NM carefully. Work out the clearest way the correction can be put on the

chart.

3. Line up the tracing accurately using the reference points given on the tracing. The

correction must never be copied down as it appears on the tracing.

4. Only after you have completed all the corrections on a chart should you add to the

correction list at the bottom left-hand corner. Always ensure that the correction

numbers are well separated.

5. When all the corrections on a chart are done, record that on the chart and in the

ship’s list of chart corrections so that the Master, the relief officers and any

inspectors can easily check for themselves that the charts are up to date.

6. Other sources of information vital to voyage planning also need to be corrected.

These include lights, fog signals and radio signals. It is worth checking through

these to ensure that you are aware of those that will affect your ship’s trading

area.

7. Keeping lists of lights, fog signals and radio signals up to date is very important.

As with the charts, accuracy and clarity are vital.

NOTE

For more detailed information about making corrections you can watch the series of

support films on the AdmiraltyTV youtube channel

5.2 Route monitoring

ECDIS makes route monitoring automatic, but you should avoid relying entirely on it.

Always maintain a regular look-out from the bridge, and always keep a navigation log

on paper as well as the automatic ECDIS log.

Other ways of ensuring safe monitoring include:

Whenever possible, have two electronic navigational systems in operation for

establishing your ship’s position.

Set a safe time period for the ECDIS alarm to sound before your ship crosses

any safety boundary or threatens to deviate from its planned route.

© MMXVII KVH Videotel

When linked with radar set a generous distance for the ECDIS alarm to sound

if another ship approaches.

Ensure target tracking devices are set with appropriate safe time and distance

warning limits.

EXERCISE

Here are some questions to consider when deciding what alterations

may be necessary for different parts of the voyage.

1. What needs to be altered to deal with the passing of danger

points in night time rather than daytime?

2. What is the best way of monitoring the voyage plan?

3. When should parallel indexing be used?

4. How does good situational awareness contribute towards the

successful execution and monitoring of the voyage plan?

5.3 Good resource management and the voyage plan

You have now been taken through all four key stages in the voyage plan – Appraisal,

Planning, Execution and Monitoring. You have seen how each of these stages has a

practical application which involves the uses of resources and technology alongside

individual skill and experience. You have also seen how good situational awareness

can make a positive contribution to the voyage plan, and help you achieve best

practice.

EXERCISE

Look back at the notes you made at the beginning of Part 3. How has

your understanding of the voyage plan been changed?

© MMXVII KVH Videotel

6 CONCLUSIONS

Whether digital or paper, accurate and up-to-date charts and navigational information

are vital to every ship because of their importance in voyage planning. As well as

being mandatory under both SOLAS and STCW, a good voyage plan is essential for a

safe and efficient voyage. It needs to be prepared well in advance so, as soon as the

departure time is accurately known, the plan must be adjusted to suit this. This may

mean that alterations are required because the tides, traffic and weather may all be

different for various parts of the voyage. Position fixing methods and bridge manning

may need to be altered to deal with the passing of danger points in night-time rather

than daytime.

Once under way, it is important that the watchkeeping officers put into practice good

resource management while they compare the progress of the voyage against the

voyage plan. This will be especially important in confined waters and challenging

traffic situations.

In difficult circumstances good situational awareness will help watchkeeping officers to

control the situation and minimise the adverse consequences.

© MMXVII KVH Videotel

7 FURTHER RESOURCES

Publications and regulations

Always consult the latest editions of regulations and publications.

IMO Resolution A.817 (19) – Performance Standards for Electronic Chart Display and

Information Systems (ECDIS)

IMO Resolution A.893(21) Guidelines for Voyage Planning

Bridge Team Operations (NauticaI Institute 2012)

International Chamber of Shipping (ICS) Bridge Procedures Guide (Marisec, 5th Edition)

Maritime Training on Board (5th Edition, 2017) – Len Holder, edited by Dr Chris Haughton

(Witherby Seamanship, 2017)

Passage Planning Principles, ISBN 13: 978 185 609 3220, Anwar & Khalique, (Witherby

Seamanship, 2006)

Organisations

Bundesamt für Seeschifffahrt und Hydrographie www.bsh.de

International Centre for Electronic Navigational Charts (ENCs) www.ic-enc.org

International Chamber of Shipping www.ics-shipping.org

International Electrotechnical Commission www.iec.ch

International Hydrographic Organization www.iho.int

International Maritime Organization www.imo.org

International Association of Independent Tanker Owners (INTERTANKO) www.intertanko.com

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office of Coast Survey

www.nauticalcharts.noaa.gov

Nautical Institute www.nautinst.org

PRIMAR www.primar.org

South China Sea Electronic Navigational Charts http://scsenc.eahc.asia

UK Hydrographic Office http://www.gov.uk/ukho

For more information about VTS, go to www.worldvtsguide.org

Related Videotel programmes

Automatic Identification Systems (AIS) (Code 926)

Collision Avoidance CD-ROM (Code 819)

ECDIS Training Course (Code 2000)

Target Tracking Devices (Code 948)

The Safe Use of ECDIS in Practice (Code 1227)

Wind, Waves and Storms, Part 2 – coping with Hazardous Weather (Code 743)

Videotel™, the market-leading provider of training films, computer-based training, and e-Learning

courses, is part of KVH Industries, Inc., a premier manufacturer of solutions that provide global high-

speed Internet, television, and voice services via satellite to mobile users at sea, on land, and in the air.

KVH is also a global news, music, and entertainment content provider to many industries including

maritime, retail, and leisure.

© MMXVII KVH Videotel

8 Appendix: ALRS volume numbers

To purchase ALRS volumes, go to www.amnautical.com

Geographical area

Vol. 1-1 Europe, Africa and Asia (excluding the Far East)

Vol. 1-2 The Americas, Far East and Oceania

Vol. 3-1 Europe, Africa and Asia (excluding the Far East)

Vol. 3-2 The Americas, Far East and Oceania

Vol. 6-1 United Kingdom and Ireland (including European Channel Ports)

Vol. 6-2 Europe (excluding UK, Ireland, Channel Ports and the Mediterranean)

Vol. 6-3 Mediterranean and Africa (including Persian Gulf)

Vol. 6-4 Indian Subcontinent, South East Asia, and Australasia

Vol. 6-5 North America, Canada and Greenland

Vol. 6-6 North East Asia

Vol. 6-7 Central and South America, and the Caribbean

© MMXVII KVH Videotel

You might also like

- United States Coast Guard: Situational Awareness ExerciseDocument20 pagesUnited States Coast Guard: Situational Awareness ExerciseOllie Evans100% (1)

- 1 Using This Training PackageDocument16 pages1 Using This Training PackageГерман ЯковлевNo ratings yet

- Hydrodynamics & InteractionDocument33 pagesHydrodynamics & InteractionIoana Johanna Cristea100% (1)

- Train The TrainerDocument144 pagesTrain The TrainerjaffersheriffNo ratings yet

- 'Report A Near-Miss - Save A Life' ReferenceDocument38 pages'Report A Near-Miss - Save A Life' ReferenceJoseph Gracious100% (1)

- Hfpa Chapter 4Document27 pagesHfpa Chapter 4Mehroob CheemaNo ratings yet

- Bridge Team Management: Situational AwarenessDocument64 pagesBridge Team Management: Situational AwarenessZitouni FodhilNo ratings yet

- The Mariner Maritme LawDocument113 pagesThe Mariner Maritme LawBi OfficialNo ratings yet

- Team Management Introduction 9Document9 pagesTeam Management Introduction 9ilgarNo ratings yet

- Information Processing Situational AwarenessDocument25 pagesInformation Processing Situational AwarenessZahid AbbasNo ratings yet

- Management 1Document4 pagesManagement 1Brendan Rezz R CilotNo ratings yet

- 2ndyear Unit 1 Lecture 6Document22 pages2ndyear Unit 1 Lecture 6Chellali RabahNo ratings yet

- Flight Safety Article FLT LT SoumitraDocument4 pagesFlight Safety Article FLT LT SoumitraSälmän Md ÄhsänNo ratings yet

- Expect The Unexpected: Evidence-Based TrainingDocument4 pagesExpect The Unexpected: Evidence-Based Trainingdionicio perezNo ratings yet

- 12Document20 pages12Maureen Janelle RemaneaNo ratings yet

- 3 Resume Harvard Business ReviewDocument6 pages3 Resume Harvard Business Reviewana.alantariganNo ratings yet

- FC Training 101Document3 pagesFC Training 101GS HNo ratings yet

- Five Techniques The Navy SEALs Use For Crisis Management.Document6 pagesFive Techniques The Navy SEALs Use For Crisis Management.Ivan Cruz (Navi Zurc)No ratings yet

- Situation Awareness and Its Practical Application in Maritime DomainDocument3 pagesSituation Awareness and Its Practical Application in Maritime DomainNdi Mvogo100% (1)

- Safety Behaviours Human Factor For Pilots 9 Human Information ProcessingDocument24 pagesSafety Behaviours Human Factor For Pilots 9 Human Information ProcessingSonya McSharkNo ratings yet

- Work Learning In: Practices Used in The U.S. Army Can Be Applied To Processes in Your OfficeDocument1 pageWork Learning In: Practices Used in The U.S. Army Can Be Applied To Processes in Your Officeoscar_pinillosNo ratings yet

- Understanding Human DowntimeDocument3 pagesUnderstanding Human DowntimesabahatmohammedNo ratings yet

- ACE Handout May'23Document178 pagesACE Handout May'23ganesh dabholeNo ratings yet

- The Complete Guide To MemoryDocument50 pagesThe Complete Guide To MemoryAllanNo ratings yet

- Leadership and Worker Involvement ToolkitDocument2 pagesLeadership and Worker Involvement Toolkitdarkot1234No ratings yet

- Airbussafetylib FLT Ops Hum Per Seq06Document11 pagesAirbussafetylib FLT Ops Hum Per Seq06Jose RicardoNo ratings yet

- IMCAD036 (Apr 2016) Neurological Assessment of A Diver (14849)Document8 pagesIMCAD036 (Apr 2016) Neurological Assessment of A Diver (14849)Michael NicolichNo ratings yet

- ACE Handout Apr 2022Document176 pagesACE Handout Apr 2022ChinsNo ratings yet

- The Kinogram MethodDocument36 pagesThe Kinogram Methodanon_371204808100% (3)

- Cert Ig Unit6 Jan20114Document73 pagesCert Ig Unit6 Jan20114testNo ratings yet

- Chapter 9 CP Foot TechniquesDocument72 pagesChapter 9 CP Foot TechniquesmarceloNo ratings yet

- Training To Enhance Sutuational AwarenessDocument4 pagesTraining To Enhance Sutuational AwarenessEzell DeLoachNo ratings yet

- TRBC Manual - Fourth Edition - 090408 PDFDocument128 pagesTRBC Manual - Fourth Edition - 090408 PDFMatheus Baños100% (1)

- Dashboard Design WhitePaper StephenFew PDFDocument23 pagesDashboard Design WhitePaper StephenFew PDFfiomaravilhaNo ratings yet

- Solution Manual For Cognitive Psychology Connecting Mind Research and Everyday Experience 5th Edition e Bruce GoldsteinDocument23 pagesSolution Manual For Cognitive Psychology Connecting Mind Research and Everyday Experience 5th Edition e Bruce GoldsteinAngelKelleycfayo100% (93)

- C4 Smeac 6523Document13 pagesC4 Smeac 6523lawtonjake100% (1)

- Steve Jobs: How To Make Faster Decisions: Discover The Skills He Used To Achieve This On A Daily BasisFrom EverandSteve Jobs: How To Make Faster Decisions: Discover The Skills He Used To Achieve This On A Daily BasisNo ratings yet

- Part IIDocument64 pagesPart IIVLONENo ratings yet

- FACILITATOR GUIDE: "It Will Never Happen To Me!": Part A - Preparation For The SessionDocument6 pagesFACILITATOR GUIDE: "It Will Never Happen To Me!": Part A - Preparation For The SessionNicolas BernardNo ratings yet

- Swimming 101 Pre Course WorkbookDocument6 pagesSwimming 101 Pre Course Workbookplpymkzcf100% (2)

- Memory and Learning: The Path To UnderstandingDocument17 pagesMemory and Learning: The Path To UnderstandingDavid HansonNo ratings yet

- DailySafetyMessages PDFDocument3 pagesDailySafetyMessages PDFvkumaranNo ratings yet

- SCIO Manual Ver 12-12-12 SampleDocument10 pagesSCIO Manual Ver 12-12-12 SampleGábor GörfölNo ratings yet

- Special Topic KnowledgeDocument22 pagesSpecial Topic KnowledgecangXXNo ratings yet

- Critical Situations in Dynamic PositioningDocument4 pagesCritical Situations in Dynamic PositioningOrlando QuevedoNo ratings yet

- Preparing For Your OSCE Examination NMC - Test of CompetenceDocument13 pagesPreparing For Your OSCE Examination NMC - Test of CompetenceSteve100% (2)

- Ebook - Funnel - Self Defense - The Fundamental Concepts To Master Before Any Technique Ebook - VOLUME 1.Document49 pagesEbook - Funnel - Self Defense - The Fundamental Concepts To Master Before Any Technique Ebook - VOLUME 1.Jeet Kune DoNo ratings yet

- Bulletproof Memory The Ultimate Hacks to Unlock Hidden Powers of Mind and MemoryFrom EverandBulletproof Memory The Ultimate Hacks to Unlock Hidden Powers of Mind and MemoryNo ratings yet

- 2 CRMDocument24 pages2 CRMrozhinhadi63No ratings yet

- Student WorkbookDocument28 pagesStudent WorkbookmkdkdNo ratings yet

- Leadership / Followership: Instructor ManualDocument108 pagesLeadership / Followership: Instructor ManualAINA SAMNo ratings yet

- Boost Your Memory: Simple and effective techniques to improve your memoryFrom EverandBoost Your Memory: Simple and effective techniques to improve your memoryNo ratings yet

- Microlearning Its Not What You Think It Is EbookDocument41 pagesMicrolearning Its Not What You Think It Is Ebookhim2000himNo ratings yet

- The Importance of Near Miss Reporting - What You Need To KnowDocument6 pagesThe Importance of Near Miss Reporting - What You Need To KnowaneethavilsNo ratings yet

- Studywise Brain Hacking - 2020Document37 pagesStudywise Brain Hacking - 2020Cristian LermaNo ratings yet

- Provide First AidDocument23 pagesProvide First AidKenard100% (6)

- Unit5 LightSearchRescueOperationsDocument34 pagesUnit5 LightSearchRescueOperationsiBooq100% (1)

- Carrier: Xpressbees: Deliver To FromDocument2 pagesCarrier: Xpressbees: Deliver To FromJoseph GraciousNo ratings yet

- BNS Semester - 1Document1 pageBNS Semester - 1Joseph GraciousNo ratings yet

- BNS Semester - 4Document1 pageBNS Semester - 4Joseph GraciousNo ratings yet

- Risk MatrixDocument1 pageRisk MatrixJoseph GraciousNo ratings yet

- Prevention and Reaction To Marine Oil Spills Marpol Annex 3Document28 pagesPrevention and Reaction To Marine Oil Spills Marpol Annex 3Joseph GraciousNo ratings yet

- Chenna: Choice Based Credit System-End SemesterDocument1 pageChenna: Choice Based Credit System-End SemesterJoseph GraciousNo ratings yet

- 'Report A Near-Miss - Save A Life' ReferenceDocument38 pages'Report A Near-Miss - Save A Life' ReferenceJoseph Gracious100% (1)

- Port State ControlDocument20 pagesPort State ControlJoseph Gracious100% (1)

- Cyber Security at SeaDocument30 pagesCyber Security at SeaJoseph GraciousNo ratings yet

- Background of The StudyDocument33 pagesBackground of The StudyTerrence MateoNo ratings yet

- Needs Analysis by Seedhouse PDFDocument7 pagesNeeds Analysis by Seedhouse PDFjuliaayscoughNo ratings yet

- 0 Test PredictivviithDocument3 pages0 Test PredictivviithmirabikaNo ratings yet

- Enghl p2 Gr11 Memo Nov2020Document21 pagesEnghl p2 Gr11 Memo Nov2020Rebecca GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Unit 9 General TestDocument7 pagesUnit 9 General TestNgoc VanNo ratings yet

- Converting Roman Numerals (A) : MMCXXXV MMDCCXXDocument20 pagesConverting Roman Numerals (A) : MMCXXXV MMDCCXXLobinhaNo ratings yet

- Remember (AhmadYosi) (11IPA1)Document3 pagesRemember (AhmadYosi) (11IPA1)Yona NiNo ratings yet

- MallDocument22 pagesMallZee ZeeNo ratings yet

- How To Motivate Students in Learning English As A Second LanguageDocument2 pagesHow To Motivate Students in Learning English As A Second LanguagebulliinaNo ratings yet

- Consonant Phoneme Chart PDFDocument19 pagesConsonant Phoneme Chart PDFAnaMaríaMorónOcaña100% (1)

- Class - 5 AYAT 1Document9 pagesClass - 5 AYAT 1Tasharif AnsariNo ratings yet

- Assignment - Unit 2 The Study of English: Pronunciation: Intonation, Stress and SoundsDocument12 pagesAssignment - Unit 2 The Study of English: Pronunciation: Intonation, Stress and SoundsSneha JaniNo ratings yet

- Command of EvidenceDocument105 pagesCommand of EvidenceHye Yun LeeNo ratings yet

- Germanic MagicDocument1 pageGermanic MagicoldwyrdthreadNo ratings yet

- The 50 Most Common Irregular VerbsDocument6 pagesThe 50 Most Common Irregular VerbsDaniela BecerraNo ratings yet

- Different Types of NounsDocument4 pagesDifferent Types of NounsSweeqin OoiNo ratings yet

- NataliaDocument5 pagesNataliaMocian Georgeta-MihaelaNo ratings yet

- Alex Byrne - Fact and ValueDocument236 pagesAlex Byrne - Fact and Valuewaarghgarble100% (1)

- Module-1 - Commn ErrorsDocument53 pagesModule-1 - Commn ErrorsSoundarya T j100% (1)

- An Introduction To C++ TraitsDocument6 pagesAn Introduction To C++ TraitsSK_shivamNo ratings yet

- DLL English 10 Q1 - WK 2 - Pre-Assessment - Nick Vucijic - 2019-2020Document7 pagesDLL English 10 Q1 - WK 2 - Pre-Assessment - Nick Vucijic - 2019-2020Jennifer L. Magboo-Oestar100% (1)

- Elizabeth Povinelli - Radical WorldsDocument16 pagesElizabeth Povinelli - Radical WorldsEric WhiteNo ratings yet

- Улсын шалгалт 12р анги 1Document70 pagesУлсын шалгалт 12р анги 1TrixelizedNo ratings yet

- Online Job Portal SystemDocument10 pagesOnline Job Portal SystemArvind singh0% (1)

- G9-English WLPDocument4 pagesG9-English WLPDada Lanuang IgnacioNo ratings yet

- English IDIOMSDocument25 pagesEnglish IDIOMSMarlene Tagavilla-Felipe DiculenNo ratings yet

- Dia Lesson 1 Intro Concepts and MethodsDocument6 pagesDia Lesson 1 Intro Concepts and Methods00laurikaNo ratings yet

- 1 EL 111 - Children and Adolescent As ReadersDocument5 pages1 EL 111 - Children and Adolescent As ReadersAngel RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of English Textbook in Pakistan A Case Study of Punjab Textbook For 9th ClassDocument19 pagesEvaluation of English Textbook in Pakistan A Case Study of Punjab Textbook For 9th ClassMadiha ShehryarNo ratings yet