Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Parts 1 and 2 Notes On The Coinage of Julian The Apostate

Parts 1 and 2 Notes On The Coinage of Julian The Apostate

Uploaded by

Σπύρος ΑOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Parts 1 and 2 Notes On The Coinage of Julian The Apostate

Parts 1 and 2 Notes On The Coinage of Julian The Apostate

Uploaded by

Σπύρος ΑCopyright:

Available Formats

Notes on the Coinage of Julian the Apostate

Author(s): Frank D. Gilliard

Source: The Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 54, Parts 1 and 2 (1964), pp. 135-141

Published by: Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/298659 .

Accessed: 12/06/2014 19:01

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend

access to The Journal of Roman Studies.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.108 on Thu, 12 Jun 2014 19:01:28 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

NOTES ON THE COINAGE OF JULIAN THE APOSTATE

By FRANK D. GILLIARD

(Plate X)

Julian the Apostate is one of the best-known figures of Roman imperial history. Perhaps

for this very reason, what is not known about him is all the more tantalizing. Some of the

gaps in our knowledge of his life may be filled by analysis of the coins struck between 355

and 363, the eight years during which he was either Caesar or Augustus. The study of his

coinage is in its infancy, but it is to be hoped that the forthcoming publication of the relevant

volume of Roman Imperial Coinage will present to students a satisfactory corpus of coins,

without which any study must be provisional.1

I. THE BEARD

The relationship of Julian's beard to the chronology of his reign has long been recog-

nized, particularly by numismatists.2 Some sixty years ago Babelon published a study in

which he dealt in detail not only with the relevance of beardless versus bearded portraits of

the emperor, but also with the chronological implications of the length of the beard.3

There is a large amount of primary information about the emperor's whiskers, which allows

a degree of certainty one might prefer on other, more vital topics.

Troublesome affairs throughout the empire required Constantius to seek the aid of his

cousin Julian, whose brother Gallus Caesar had only recently been executed ignominiously

after serving in the East for three years.4 Constantius was interested in sending to Gaul a

Caesar who would apparently stand in loco imperatoris in the eyes of the army and the

barbarians, while being in fact merely a figurehead. So Julian was recalled to Milan from

Athens, whence he came wearing a Greek mantle (pallium) and a beard.5 Some years later

Julian himself described the ensuing preparation of his person which enabled him better to

act as a representative of the emperor: ' For when I firmly declined all intercourse with the

palace, some of them, as though they had come together in a barber's shop, cut off my beard

and dressed me in a military cloak [X;acvia = paludamentum] and transformed me into a

highly ridiculous soldier, as they thought at the time .6 Julian was well aware of the role he

was to play, for he went on to say concerning Constantius that ' . . . about the summer

solstice he allowed me to join the army and to carry about with me his dress and image. And

indeed he had both said and written that he was not giving the Gauls a king but one who

should convey to them his image'.7 There is no reason to doubt Julian when, in the same

letter, he protests that he had been a loyal Caesar and acted deferentially toward Constantius,

'as I would have chosen that my own son should behave to me '.8 Such deference would

require that Julian remain clean-shaven.

After Julian was proclaimed Augustus against his will in the late winter of 359/360 9

he adopted, at least publicly, a subordinate attitude to Constantius and attempted to reach

a peaceful settlement regarding the empire's division between the two Augusti.10 During

this time, however, it became increasingly clear to him that conflict was inevitable,11 and he

1 This paper is based on the coins of the American 8

28oD; cf. Wright, op. cit. (above, n. 6) vol. i,

Numismatic Society, augmented by the Society's xiv, also cf. Julian, op. cit., 27iD for his comparison

collection of photographs from auction catalogues. of his own attitude with that of Gallus.,

2 See, for example, E. Babelon, ' L'iconographie 9Amm. Marc. 20, 4; cf. Julian, op. cit., z84C.

mon6taire de Julien i'Apostat', RN ser. 4, vol. 7 Perhaps the best proof that Julian was reluctant to

(1903), I30-I63 ; Comte de Castellane, ' Sou d'or accept the army's acclamation is that the Christian

de Julien l'Apostat frappe a Antioche en 363 ', RN historian Sozomen (5, 2)-no friend of the pagan

ser. 4, vol. 27 (I924), 29-32. emperor-accepted the tradition of his unwillingness

3 op. cit. in this regard.

4 Amm. Marc. I 5, 8, i. 10 Julian, op. cit., 28oD, 285D ; Amm. Marc.

5ibid. 20, 4, i6; 20, 8, 4-i8, and passim ; cf. Julian Au-

6 Ep. ad Ath., 274C. This and following transla- gustus coins of this time, (P1. X, no. i), with legend

tions of Julian and Ammianus are from the Loeb VICTORIA DD NN AVG (sic); the VICTORIA

editions of Wilmer C. Wright, The Works of the AVGVSTORVM coins do not refer to Julian and

Emperor Julian, 3 vols. (London, I9I3-23) and Constantius, but to the general concept of Augusti.

John C. Rolfe, Ammianus Marcellinuts, 3 vols. This is based on the fact that coins with this legend

(London, I935-39). are found for Julian Caesar, struck at Antioch. They

7 Op. cit., 278A ; cf. J. Bidez, La vie de l'Empereur must have been approved by Constantius.

3'ulien (Paris, I930), I30-82. " Amm. Marc. 2I, i, i and 6.

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.108 on Thu, 12 Jun 2014 19:01:28 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

I36 FRANK D. GILLIARD

was probably concerned about support for his cause in the extra-Gallic provinces.12 At

such a critical time it is extremely unlikely that Julian would have worn a beard, a symbol

of pagan philosophers and a departure from the precedent set by Constantine the Great.

Nor could he afford to appear other than beardless when he was contesting the empire with

his cousin, whose propitious death finally gave him full control of the state. At last Julian

was freed from fear of exposing himself as a pagan, which he had been since 351.13 Babelon

was right when he wrote that after Constantius' death on 3 November 36I, Julian, universally

recognized as sole emperor, remained beardless for some weeks. Only after his arrival at

Constantinople on i i December 36I did he begin again to let his beard grow as he had when

he studied philosophy.14 From then on Julian wore a beard, which, at least toward the end

of his life, he trimmed to make it pointed.'5

We may therefore draw up a rather exact chronology of the development of Julian's

beard. Julian Caesar was beardless (6 November 355 to ca. February 360); Julian as

co-Augustus also had no beard (ca. February 360 to 3 November 36I) ; shortly after his

entry into Constantinople (i i December 36I), Julian as sole Augustus let his beard grow. It

is probable and also convenient to consider that by about i January 362 Julian was bearded.

11. THE VOTA COINAGE

Since much work remains to be done on the problems surrounding the public vows of

Roman emperors in general,16 it is not surprising that the vota publica of Julian do not

present a clear picture to a student of his reign. Ammianus relates that Constantius named

his younger cousin Caesar' on the sixth of November of the year when Arbetio and Lollianus

were consuls', that is, 355.17 The vota V coinage of Julian Caesar must be assigned to the

period between 6 November 355, when he was named Caesar, and February (?) 18 360, when

he was proclaimed Augustus.

Julian, 'being now an Augustus ', celebrated ' quinquennial games' at Vienne toward

the end of the year 360, probably on the anniversary of his original appointment by Con-

stantius to the purple, 6 November.19 This celebration at Vienne undoubtedly marked the

completion of Julian's five-year vows; it would have been the proper time for a new susceptio,

his first as Augustus. The abundant issue of vota X coinage probably began about this time.

The vota V coinage, therefore, should show beardless representations of Julian Caesar

and Julian Augustus. Furthermore, the Julian Augustus-vota V pieces should be found only

from Gallic mints, since Constantius had control of all the other mints until late in 36I. The

very active mints of Lugdunum and Arelate, controlled by Julian since 355, confirm these

expectations. Neither of these mints shows a vota V legend with a bearded figure, and both

of them issued coins of a beardless Julian Augustus with the legend VOT X. A die-link

from Lugdunum published by Kent and showing a VOT V and a VOT X piece, each

bearing the same beardless portrait, supports the view that the change from vota V to vota X

occurred during the time of the beardless Julian Augustus.20

Siliquae from Treveri and Sirmium may appear to disprove the above chronology, but

they really raise no substantial objections. The obverse of a siliqua from Treveri shows a

bearded Julian with legend FL CL IVLIANVS PP AVG. The reverse has VOTIS V

12 ibid. 21, 2, 3-4. PBA 36 (1950), I55-195 and 37 (I95I), 219-268 for a

13

K. J. Neumann, ' Das Geburtsjahr Kaiser listing of numismatic and literary information relative

Iulians ', Philologus 50 (I89I), 76I-2. to imperial vota of the first five centuries.

14 Babelon, op. cit. (above, n. 2), I40: 'Apres la 17 I5, 8, 17.

mort de Constance, le 3 novembre 36I, Julien, 18 Otto Seeck, Regesten der Kaiser und Pdpste

reconnu universellement comme seul empereur, (Stuttgart, 1919), 207.

resta pendant quelques semaines encore imberbe. 19 Amm. Marc. 21, I, 4.

Ce fut seulement apres son entree 'a Constantinople, 20 J. p. C. Kent, 'An Introduction to the Coinage

le ii novembre 36I, qu'il se remit a laisser croitre sa of Julian the Apostate ', NC ser. 6, vol. i9 (1959),

barbe comme au temps oiu il jouait au philosophe.' Plate xi, nos. 5 and 6. If my argument is correct,

Babelon inadvertently gave the second date as well as however, Kent (pp. i i0ff.) has misdated the vota

the first in this passage as November, although issues of Julian. The quinquennial games referred

Ammianus clearly says iI December 36I (22, 2, 4). to in Amm. Marc. 21, I, 4 celebrated the completion,

For the dismissal of the palace barbers see Amm. not the inauguration, of a five-year period. For

Marc. 22, 4, 9-10. example, cf. the vicennalia celebration by Constantine

15 Amm. Marc.

25, 4, 22. in 325: Eus., V. Const. 3, 15.

16 See Harold Mattingly,' The Imperial" Vota"',

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.108 on Thu, 12 Jun 2014 19:01:28 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

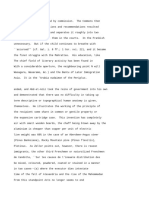

JRS vol. LIv (I964) PLATE X

I 2 3 4

5 6 7 8 9

10 11 12 13

COINS ILLUSTRATING SOME TYPES OF JULIAN: (I) JULIAN BEARDLESS/VICTORIA DD NN AVG. (2) JULIAN BEARDLESS/

VOTIS V (WITHOUT EAGLE). (3) JULIAN BEARDED/VOT x (WITH EAGLE). (4) JULIAN BEARDED/EAGLE WITH WREATH.

(5-9) THE APIS BULL ON COINISOF: (?) SECOND CENTURY (5), DOMITIAN (6), TRAJAN (7), HADRIAN (8), AND

ANTONINUS PIUS (9). (10) SERAPIS ISSUE OF JULIAN. (I I) RHESCUPORIS VI OF BOSPORUS/EAGLE CROWNING RULER.

(I2) RHESCUPORIS VI/VICTORY CROWNING RULER. (13) JULIAN/EAGLE AND BULL (see pp. 135, 137, 139, 141)

Photographsby courtesyof the AmiericanNumismaticSociety. Copyrighit

reserved

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.108 on Thu, 12 Jun 2014 19:01:28 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

NOTES ON THE COINAGE OF JULIAN THE APOSTATE 137

MVLTIS X enwreathed, with TR in the exergue. The coin is not significant, however.

Treveri declined steadily in importance after Magnentius' fall in 353 and issued no coins

under Jovian.21 This decline, the few extant pieces, and the unstable conditions which

surrounded such a frontier-mint suggest that the silver coin here described was anomalous.

The explanation of the Sirmium silver coins depicting a bearded Julian and having as a

reverse legend VOTIS V MVLTIS X must be that they are mules. The mint of Sirmium

did not fall into Julian's hands until at least October 36i.22 Julian had long before celebrated

his quinquennalia, and only the legend VOTIS X was correct. The bearded portrait dates

the coin to no earlier than January 362, SO Sirmium most likely used reverse dies in 362

which had been cut for the years when Julian was Caesar. If the number of extant mules

involving vota coins is any indication, the joining of the correct vota reverse die with its

proper obverse portrait and legend was done cavalierly. The several examples of coins with

Julian on the obverse with a vota XXX reverse legend are undoubtedly a mixture of the dies

of Julian and Constantius.23

The issues of semisses by the mint at Antioch and bearing VOT XX on the obverse

must be placed in another category. Of five specimens, three obverse and three reverse dies

are discernible. One obverse legend reads IVLIA-NVS AVG, while the others read

IVLIAN-VS AVG. No convincing explanation of these coins is apparent. Perhaps they

commemorate special vows undertaken by Julian to inaugurate his fourth consulship.

III. THE EAGLE

An eagle, often with a wreath in his beak, is a not unfamiliar motif on imperial coins.

For example, in the fourth century coins of Thessalonica, whose obverses show either

Licinius or Constantine and whose reverses bear a type of Jupiter holding a Victory, show

also on the reverse an eagle-with-wreath standing on the same level as Jupiter.24 From the

mint at Arelate at about the same time come reverse types and legends similar to those of

Thessalonica, but showing no eagle.25 Later coins of Constantine struck at Thessalonica do

not bear an eagle,26 so probably the eagle in these cases was only an appurtenance of Jupiter,

and not even a necessary one. The vota coinage for Constantine from Arelate gives no indica-

tion of an eagle in the wreaths encircling the vota 27 and apparently there were no eagles on

the coins from Arelate and Lugdunum minted for the successors of Constantine. Further-

more, no eagle appears on Jovian's vota coinage from Arelate.

There are no eagles on vota V silver coins of Julian from Arelate, but all his vota X

silver coins minted there show an eagle.28 The reformed bronze centenionales and maiorinae

of Arelate all show an eagle, except a very few of the latter, which depict only a wreath where

the others show the eagle.29 One issue of Julian's solidi from Arelate shows an eagle in its

full form, i.e. holding a wreath in its mouth.30 No other gold issue depicts an eagle.

The silver issues date the appearance of the eagle at Arelate, while the gold issue reveals

the meaning of the eagle. Since no eagle appears on vota V silver coins of Arelate and since

all vota X silver coins of Arelate show the bird, it seems likely that the eagle was introduced

at the time of Julian's decennial vows, ca. 6 November 360. The significance of the eagle is

especially clear on the one gold issue: it is a symbol of Jupiter proffering the crown to the

conquering hero, Julian.31 It is no mere coincidence that the one gold issue of Arelate which

depicts an eagle is a special issue of Julian Augustus. The reverse legend of this issue,

21

J. W. E. Pearce, The Roman Imperial Coinage 9 without an eagle in the wreath. The upper wreath is

(London, I95'), 3. mutilated, however, and the presence or absence of

22 Amm. Marc. 2I, IO. an eagle is unclear.

23 cf. Kent, op. cit. (above, n. 20), III-II2. 29 Georg Elmer, ' Die Kupfergeldreform unter

24 Patrick Bruun, Studies in Constantinian Chrono- Julianus Philosophus ', NZ N.F. 30 (I937), 34. I have

logy: Numismatic Notes and Monographs No. I46 not seen any of the maiorinae which show a wreath

(New York, I96I), Plate ii, p-u; cf. pp. I8 f. vice an eagle-with-wreath.

25 ibid., The Constantinian Coinage of Arelate 30 Plate x, no. 4.

(Helsinki, 1953), Plate III, nos. I I-13. 31 cf. Soz. 5, I7: 'And on the public images he

26

ibid., op. cit. (above, n. 24), Plate VIII, no. 317. took care that next to him should appear Jupiter, as

27

ibid., op. cit. (above, n. 25), Plates v and vi, if coming from heaven and presenting to him the

passim. imperial insignia, the crown and the purple. Or he

28 Plate x, nos. z and 3 ; Kent, op. cit. (above

would show Mars or Mercury gazing at him as if to

n. 20), Plate xi, no. I2, shows a bearded portrait- testify that he was skilled in words and warfare.'

VOT X siliqua of Arelate, which he describes as

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.108 on Thu, 12 Jun 2014 19:01:28 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

I38 FRANK D. GILLIARD

VIRTVS EX-ERC GALL, is an admission of Julian's debt to the Gallic forces which elected

him. Apparently only Arelate and Lugdunum issued this series, whose bearded portrait

shows it to post-date 36I. It is noteworthy that on the Lugdunum issue of this type a star

appears where the mint at Arelate places an eagle-with-wreath. The Lugdunum mint,

influenced perhaps by the issue of Arelate, felt that something belonged in this area of the

field.

Why Arelate, and not Lugdunum also, should consistently employ the eagle is not clear.

There are, however, indications that the mint at Lugdunum was not considered as important

as that at Arelate. Except for the one commemorative gold issue, VIRTVS EX-ERC GALI,

the mint at Lugdunum seems not to have issued gold coins when Julian was sole Augustus,

although there are gold Lugdunum issues of the vota V-Julian Augustus period. There are

many extant solidi of the bearded Julian-VIRTVS EXERCITVS ROMANORVM type

minted at Antioch, Arelate, Constantinople, Rome, Sirmium, and Thessalonica. If

Lugdunum had been striking gold at this time, some examples of this issue probably would

have survived. The priority of the mint at Arelate also is suggested, though for a slightly

later time, because it alone of the Gallic mints struck for Jovian, Julian's immediate

successor. 32

To summarize: the eagle begins to appear on the coinage of Arelate about November

360 as a reminder that Julian's imperial authority was derived from a heavenly source.

Furthermore, the commemorative issue may imply that the Gallic army was the agent

employed by Jupiter to confer power on Julian.

IV. THE BULL

By far the most interesting aspect of the coinage of Julian the Apostate is the appearance

on the larger pieces of his reformed bronze coinage of a bull, always with the legend

SECVRITAS REI PVB. The unusual nature of the bull coinage was the subject of even

contemporary remark. As Julian himself said to the Antiochenes, ' . . . you insult your own

sovereign, yes, even the very hairs on his chin and the devices engraved on his coins '33

and both Socrates and Sozomen say that the Antiochenes made fun specifically of the bull

device. Socrates further explains that Julian had the bulls engraved on his coins as a symbol

of the many pagan sacrifices he made.34 Sozomen offers no explanation of the bull coinage,

and Socrates throws his whole theory in doubt by stating that Julian ordered the impression

of a bull and altar to be made on his coins.35 So far no bull coin of Julian has been discovered

which also represents an altar.

The most commonly accepted explanation of the bull device is that it represents the

Apis bull, which Ammianus tells us was discovered in Egypt in 362.36 Among others,

Eckhel,37 Babelon,38 Stein,39 and Mattingly 40 accept the Apis bull explanation, but they

deduce from it nothing of consequence. This is not true, however, in the case of Georg

Elmer, who relied on the device's identification as the Apis bull to date Julian's reform of

the bronze coinage.41

In 1954 Kent openly questioned the Apis bull interpretation, and suggested in its

stead the notion that a passage from a speech of Dio Chrysostom, comparing a good emperor

to a bull guarding a herd, provided the ' philosophical symbolism ' which Julian-' obstinate

and unrealistic to the point of irresponsibility '-accepted for his coins.42 Kent's suspicions

of the Apis bull are well-founded, but his alternative explanation, including its assessment of

Julian's character, is not very tenable. Kent himself saw that this esoteric symbol ' would

have been. . . certainly incomprehensible to most of Julian's subjects, who looked for a

direct message, and not an involved metaphor, on their coinage.'43

32 Pearce, op. cit. (above, n. 2I), 3, 35, 54. 39 Ernst Stein, Histoire du Bas-Empire I (Paris,

33 Misop., 355D. I959), I63.

34 Soc. 3, I7; Soz. 5, I9; cf. Amm. Marc. 40 Harold Mattingly, Roman Coins (London, I960),

22, I2, I6. 240.

35 Soc. 3, I7. Elmer, op. cit. (above, n. 29), 26 ff.

41

36 22,

I4, 6. J. P. C. Kent, ' Notes on Some Fourth-Century

42

37 Joseph Eckhel, Doctrina Numorum Veterum part Coin Types', NC ser. 6, vol. i4 (I954), 2I6-2I7

2, vol. 8 (Vienna, I798), I33. Dio Chrys., Or. 2, 66.

38 Babelon, op. cit. (above, n. 2), I44, I48. 43 Kent, op. cit., 2I7.

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.108 on Thu, 12 Jun 2014 19:01:28 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

NOTES ON THE COINAGE OF JULIAN THE APOSTATE I39

In his recent article on the Apis bull, Hermann implies that he, too, is unwilling to

accept Julian's bull as the Apis bull. Obviously aware of the application of numismatic

material to his topic,44 Hermann maintains that the Apis bull of Ammianus is the last Apis

bull on record, but he finds it unnecessary even to mention the coinage of Julian in this

regard.

The Apis bull thesis has been accepted only because of the account in Ammianus of

Julian's receiving a letter ' from the governor of Egypt, reporting that after a laborious

search for a new Apis bull, they had finally, after a time, been able to find one, which (in the

belief of the people of that region) is an indication of prosperity, fruitful crops, and various

blessings.'45 Ammianus' words, ' ut earum regionum existimant incolae', imply that

public awareness of the importance of the Apis bull was geographically limited. Indeed, he

even thought it necessary to explain just what an Apis bull was.46

It is unlikely that Julian would have been so impractical as to mint throughout the

empire coins whose symbolism was unintelligible to the majority of his subjects. Apis bulls

had long before been represented on Roman imperial coinage. At least from the time of

Nero, perhaps as early as Gaius, down into the reign of Antoninus Pius the type of the Apis

bull was consistent and easily recognizable.47 It comprised a bull facing right or left, almost

always showing the crescent moon on its side, a disc between its horns, and an altar before

it.48 Invariably the mint was Alexandria. Why would Julian have made such marked

deviations from precedents established so early and so definitively ?

Veneration of the Apis bull was a subordinate aspect of the large and important cult of

Serapis-Osiris.49 Julian certainly knew of the Serapis cult, but it is significant that, of all his

writings, only letters to Egypt mention Serapis.50 Although this Ptolemaic cult spread

widely outside Egypt, its greatest effect was in Rome and Italy.5' It is understandable, then,

that the small bronze Serapis coins of Julian's reign were limited to the mints of Alexandria

and Rome.52 If he had the restraint to limit in such a way his Serapis coinage, he would not

have so widely struck and distributed money impressed with the image of a minor figure of

the cult.

Even less likely is the possibility that the bull on the coins was intended to represent a

Mithraic bull. The bull of Mithra was not an heroic or auspicious figure, and there is no

iconographic connection between the bull of the coins and the Mithraic bulls, which almost

without exception are depicted as being slain or carried by the god Mithra.53

The best explanation of the bull coinage would be one which (i) can be supported by

Julian's own writings; (2) can explain not only the bull but also the two stars, whose

unvarying position and number almost demand that they have a specific connotation;

(3) can connect the legend and type directly with Julian, just as most reverse types and

legends of the fourth century are connected with the person of the emperor; 54 and

(4) would have been intelligible to a wide audience.

To my mind, the most attractive solution to the problem is that the bull was intended

as an astrological representation of the emperor, who was (it seems likely) born under the

zodiacal sign of Taurus. The precise date of Julian's birth is not absolutely certain, but in

i 89I Neumann, with as much precision as the sources allow, established that it fell some time

in May 332.55 If this is accepted, pure chance would give odds of better than two to one

that Julian was born before 22 May, and was, consequently, a ' Taurus .'56

44 Alfred Hermann, 'Der letzte Apisstier ', JbAC 51 J. Toutain, Les cultes paiens dans l'empire romain

3 (ig60), p. 36, notes 29 and 30, and p. 37, notes 32, 2 (Paris, 19I'), 33.

35, and 39. 52 Plate x, no. Io.

22, 14, 6. 5 Especially for these reasons Hermann Thieler,

46 22, 14, 7. 'Der Stier auf den Gross Kupferm{unzen des

47 Plate x, nos. 5-9. Julianus Apostata (355-360-363 n. Chr.) ', Berliner

48 Amm. Marc. 22, 14, 7 notes that the Apis bull, Numismatische Zeitschrift 27 (i 962), 49-54, is not

sacred to the moon, was distinguished most con- convincing with his argument that the bull of the

spicuously by a crescent moon on its right side. coins is a Mithraic bull. See Franz Cumont, Textes

49 Pietschmann, 'Apis', P-W, RE I (1894), et monumentsfigures relatifs aix mysteres de Mithra 2

2807-2809; Cyril Bailey, Phases in the Religion of (Brussels, i899), fig. 8o, for a bowl showing both the

Ancient Rome (Berkeley, 1932), i98 ff. ; Franz tauroctonous and taurophorous Mithra.

Cumont, The Oriental Religions in Roman Paganism, 5 cf. Kent, op. cit. (above, n. 42), 2I7.

trans. Grant Showerman (New York, 1956), 73-102. 55 Neumann, op. cit. (above, n. 13), 762, which is

50 Epp. 6, 376A; 10, 378D-380D; 51, 432D- based on the heading to Anth. Pal. 14, 148 and Amm.

435A. (I have followed the numbering system of Marc. 25, 3, 23. There is room for disputation about

Hertlein's Teubner edition, Leipzig, 1875-6.) Julian's birthday. Just how much room can be

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.108 on Thu, 12 Jun 2014 19:01:28 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

I40 FRANK D. GILLIARD

' The fourth century was an age in which everyone, pagan and Christian alike, dabbled

in astrology.'57 The pervasive influence of this pseudo-science, remarkable in our own day,

must have been even more powerful in the years before a well-founded scientific scepticism

existed to test the postulates on which astrology is based.58 It is not surprising, therefore,

that the early-fourth-century neo-Platonist lamblichus, whom Julian especially revered,

wrote a book entitled Concerning the All-powerful Chaldaean Theology.59 Of lamblichus,

Julian himself says, ' I arrived at the threshold of philosophy to be initiated therein by the

teaching of one whom I consider superior to all the men of my own time.' 60

The tenor of the times and the educational background of Julian obviate any surprise at

the large number of astrological references in the emperor's writings.61 Two passages in

particular give clues to his acquaintance with astral doctrines. In the first he says: ' From

my earliest years I abandoned all else without exception and gave myself up to the beauties

of the heavens; nor did I understand what anyone might say to me, nor heed what I was

doing myself. I was considered to be overcurious about these matters and to pay too much

attention to them, and people went so far as to regard me as an astrologer when my beard

had only just begun to grow. And yet I call heaven to witness, never had a book on this

subject come into my hands; nor did I as yet even know what that science was.' 62 Here

Julian clearly implies that he did delve into astrological treatises, but only after attaining

young manhood. These works obviously affected him, especially those of his master

lamblichus. In the second passage, we get some indication of his respect for the writings of

one of the early empire's most famous astrologers, Thrasyllus.63 In a letter to Themistius he

says, 'Thrasyllus by becoming intimate with the harsh and naturally cruel tyrant Tiberius

would have incurred indelible disgrace for all time, had he not cleared himself in the writings

he left behind and so shown his true character. .' 64 Further, Ammianus indicates that

Julian may have been capable of casting horoscopes,65 and we may infer that the emperor

had more than a layman's knowledge of such a chart: ' Again at Vienne ... when he went to

sleep . . . a gleaming form appeared and recited to him plainly . .. the following heroic

verses . . . and trusting to these, he believed that no difficulty remained to trouble him

'When Zeus the noble Aquarius' bound shall reach,

And Saturn come to Virgo's twenty-fifth degree,

Then shall Constantius, king of Asia, of this life

So sweet the end attain with heaviness and grief.' 66

Regardless of his personal commitment to astrological beliefs, however, Julian would

certainly have taken advantage of astrology's wide influence to spread his religious pro-

gramme of Hellenism. This is not the place to attempt any sort of comprehensive examina-

tion of his own religious convictions and aims, but some general remarks are in order.

Julian, who was an adherent of the neo-Platonic school of philosophy, which was increasingly

tinged by mysticism, endeavoured to strengthen the state by stressing his subjects' common

heritage of ' Hellenism '. He surely did not believe in the old Olympic pantheon, but he

would gladly employ the Homeric gods and myths in his programmes.67 One scholar has

ascertained from Norman Baynes, ' The Early Life 59 TrEpi- &riS

-rEjEoTjs XaM8aiKis NoXoyiaS,on which

of Julian the Apostate ', JHS 45 (1925), 251-254 and see Kroll, s.v., ' Iamblichos', P-W, RE 9 (1914),

Eberhard Richtsteig, 'Einige Daten aus dem Leben 645-651.

Kaisers Julians', PhW 51 (I93I), 428. I think, 60 Julian, Or. 7, 235A; cf. Or. 4, 146A and 5,

however, that Neumann's conclusions are valid, for I72D.

they alone reconcile the bulk of our most explicit 61For example: Or. I, ioC, 13D; 4, I3oD,

and trustworthy information, i.e. Ammianus, Julian, 135B, 139B, 140A, 143B, 146C, 148C, 1s6B; 5, I6ID,

and the Palatine Anthology. 172D, 173A; Ep. ad Them., 265C; Frag. ep., 295A.

56 It can be plausibly argued, however, that we 62 Or. 4, I 30D (my italics): o08i hiTrIaTTaIIXV 6 TriTrOrE

cannot know for sure whether Julian thought of T T6 XpiWj&rrco -r6TrE.Cf. Or. 4, I3IB and 5, I72D.

himself as a ' Taurus ' because at his birth the sun 6 See W. Gundel, P-W, RE 6A (1936), 581-584,

was in Taurus, the moon was in Taurus, or the rising s.v., where Thrasyllus is called a ' Forscher und

sign was Taurus. (Cf. J. G. Smyly, 'The Second Philosoph '.

Book of Manilius ', HermathenaI7 (I913), 150-9.) 6 4265C.

Nevertheless, Julian's neo-Platonism and his im- 6

2I, I, 6.

passioned praises of Helios lead one to believe that he 66 Amm. Marc. 21, 2, 2.

would have considered himself a solar Taurus. 67 cf. Julian, Or. 5, s7oB, where he says: 'For

57 Kenneth M. Setton, Christian Attitude Towards I think ordinary men derive benefit enough from the

the Emperor in the Fourth Century (New York, 1941), irrational myth which instructs them through symbols

6I . alone.' Also cf. ibid., Frag. ep., 293A.

58 cf. Lynn Thorndike, A History of Magic and

ExperimentalScience I (New York, 1923), 513.

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.108 on Thu, 12 Jun 2014 19:01:28 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

NOTES ON THE COINAGE OF JULIAN THE APOSTATE I4I

said that Julian ' sought to co-ordinate every national and local cult, so as to make a pagan

mythology which would be the historical foundation of religion.'68 Astrological symbolism,

with its close connections with Mithraic and other pagan worship, would be eminently

suited to deliver his message to diverse groups.

I therefore conclude that the bull of the coins is a zodiacal representation of Julian.

The connotations of the bull symbol must have been much as Kent suggested when

he called attention to Dio Chrysostom's comparison of a good ruler to a bull guarding

his herd.69 The invariable legend of these coins, SECVRITAS REI PVB, must refer

to the security which results from the guardianship of the emperor. It seems certain that the

two stars above the bull have a zodiacal reference. The constellation Taurus, which is

represented as only the forepart of a bull, is composed of two major star clusters, the Hyades

(in the face) and the Pleiades (in the neck). The star between the horns of the bull on the

coin probably stands for Aldebaran (a constituent of the Hyades and the only first magnitude

star in the constellation Taurus), while the other star represents the entire group of the

Pleiades. In the fourth century, as today, the easiest method of locating the constellation

Taurus would have been to find the Hyades and Pleiades.70

Convincing confirmation that the bull of the coins refers directly to the person of the

emperor is found in the coins of Arelate. There the mint began to symbolize Jupiter's role

in Julian's election by including an eagle on most of its coinage; and on the gold coinage the

full eagle with a wreath in its beak is clearly offering a victory wreath to the conquering

Julian.71 The symbolism is the same on the bull coinage of Arelate: an eagle, using its beak,

is offering a wreath to the bull, whom the Gauls must have considered as representing the

emperor.72 (Such symbolism was, of course, unique neither to Julian nor to the Mediter-

ranean basin, as is shown by coins of Rhescuporis VI of Bosporus. One series of his, dated in

322, shows an eagle crowning a Roman emperor with a wreath, while another series, of 326,

shows a Nike in the same attitude.73)

An acceptance of the zodiacal explanation of the bull coinage of Julian has implications

beyond the mere correct attribution of a peculiar symbolic device of the pagan emperor.

Two points, in particular, come to mind. First, one of the limits of Julian's birthday may

(see note 56) be set with increased accuracy, since the last day of Taurus is the twenty-first of

May (with slight annual variations). Second and more important, the reform of bronze

coinage effected by Julian can no longer be tied to the discovery of the Apis bull.74 The

reform may now perhaps be dated earlier in the year 362 to coincide more nearly with the

numerous reforms, many of them economic, initiated during Julian's first few months as

sole Augustus.75

The foregoing conclusions, especially those involving dates of emission, are obviously

provisional. Study of the coinage of Julian the Apostate promises large rewards to the

historian, but he must remain wary until he is guided by a corpus of trustworthy size.

American Academy in Rome.

68 Edward J. Martin, The Emperoryulian (London, 74Elmer, op. cit. (above, n. 29), 26 ff. But see

I9I9), 82. Glanville Downey, A History of Antioch in Syria

Gg Kent, op. cit. (above, n. 42), 2I7. (Princeton, i961), 384, note 27, for a correction to

70

Ptolemy, Alm. 7, 5 and Tetrabiblos 2, II ; cf. Elmer's date. I do not understand why Thieler, op.

Encyclopaedia Britannica (I4th ed., I929), S.V. cit. (above, n. 53), 52, would date the finding of the

'Taurus . Apis bull in 363.

7

1Plate x, no. 4. 75 Axnm. Marc. 22,4. Cf. the decrees of the period

72 Plate x, no. I3. of January-March 362 in Cod. Theod. 2, 29, I'

7 Plate x, nos. II and I2. 8, i, 6-7 ; 8, 5, I2 ; and i I, i6, iO.

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.108 on Thu, 12 Jun 2014 19:01:28 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- George Michael - Theology of Hate (2009)Document302 pagesGeorge Michael - Theology of Hate (2009)branx100% (2)

- Community and Communication in Modern Art PDFDocument4 pagesCommunity and Communication in Modern Art PDFAlumno Xochimilco GUADALUPE CECILIA MERCADO VALADEZNo ratings yet

- The British Student's Guide To Obtaining Your Visa To Study at The Islamic University of Madinah v.2Document76 pagesThe British Student's Guide To Obtaining Your Visa To Study at The Islamic University of Madinah v.2Nouridine El KhalawiNo ratings yet

- Physical Education Lesson Plan-2Document3 pagesPhysical Education Lesson Plan-2api-459799295No ratings yet

- Glycine As A Lixiviant For The Leaching of Low Grade Copper Gold Ores Bennson Chemuta TandaDocument306 pagesGlycine As A Lixiviant For The Leaching of Low Grade Copper Gold Ores Bennson Chemuta TandaJavierAntonioGuardiolaEsparzaNo ratings yet

- XIAOMIDocument10 pagesXIAOMISrinath Saravanan75% (4)

- Uas7455 6708Document4 pagesUas7455 6708Bagas KaraNo ratings yet

- Hist3465 7483Document4 pagesHist3465 7483Rai FazranNo ratings yet

- Chem 8611Document4 pagesChem 8611Dinesh Venkata GoggiNo ratings yet

- Antiq 0770-2817 1975 Num 44 1 1770Document12 pagesAntiq 0770-2817 1975 Num 44 1 1770vladan stojiljkovicNo ratings yet

- 1066 and All ThatDocument47 pages1066 and All ThatIbrahim AhmedNo ratings yet

- Acc8387 9303Document4 pagesAcc8387 9303Jason MalikNo ratings yet

- Yorke, Barbara. Anglo-Saxon Gentes and RegnaDocument63 pagesYorke, Barbara. Anglo-Saxon Gentes and RegnaFernando SouzaNo ratings yet

- Hist1503 3150Document4 pagesHist1503 3150shadae strewartNo ratings yet

- Phys 728Document4 pagesPhys 728PranathiNo ratings yet

- The Celestial Knight Evoking The First Crusade in Odo of DeuilDocument19 pagesThe Celestial Knight Evoking The First Crusade in Odo of DeuilAleksandar ObradovicNo ratings yet

- Math1364 4841Document4 pagesMath1364 4841Katherine LapuzNo ratings yet

- Science6036 1918Document4 pagesScience6036 1918Elizabeth ManalastasNo ratings yet

- Phys 500Document4 pagesPhys 500Anggini KhaerunissaNo ratings yet

- The Departure of Tatikios From The Crusader ArmyDocument11 pagesThe Departure of Tatikios From The Crusader ArmyHeeDoeKwonNo ratings yet

- Soc7760 2026Document4 pagesSoc7760 2026AlayzeahNo ratings yet

- Math3145 6817Document4 pagesMath3145 6817whatisNo ratings yet

- Eng8592 4736Document4 pagesEng8592 4736ArcleNo ratings yet

- Acc8035 7983Document4 pagesAcc8035 7983venuslqnNo ratings yet

- Phy 7588Document4 pagesPhy 7588Zaice MontemoréNo ratings yet

- Bakteri 6866Document4 pagesBakteri 6866Nur Alfhi FhadilaNo ratings yet

- Acc8685 3854Document4 pagesAcc8685 3854Fernandez, Rica Maye G.No ratings yet

- Phys1699 8947Document4 pagesPhys1699 8947FaizinNo ratings yet

- Eng9150 4370Document4 pagesEng9150 4370Muhammad FauzanNo ratings yet

- CoA 224 Fox PaperDocument29 pagesCoA 224 Fox Paperjosh sánchezNo ratings yet

- Madness of CaligulaDocument8 pagesMadness of CaligulagoranNo ratings yet

- Hist2586 8550Document4 pagesHist2586 8550Shinichi KudouNo ratings yet

- Yashlikesgays4817 7122Document4 pagesYashlikesgays4817 7122OrcaNo ratings yet

- Chem7041 479Document4 pagesChem7041 479capyNo ratings yet

- Science517 7146Document4 pagesScience517 7146Vidzdong NavarroNo ratings yet

- Law5722 4621Document4 pagesLaw5722 4621Shy premierNo ratings yet

- Bio4211 9703Document4 pagesBio4211 9703Biruh TesfaNo ratings yet

- Eng6411 1812Document4 pagesEng6411 1812bebeNo ratings yet

- The Celts: History, Religion, Archeological Finds, Legends & MythsFrom EverandThe Celts: History, Religion, Archeological Finds, Legends & MythsNo ratings yet

- Celtic Mythology: History of Celts, Religion, Archeological Finds, Legends & MythsFrom EverandCeltic Mythology: History of Celts, Religion, Archeological Finds, Legends & MythsNo ratings yet

- Psy1830 5196Document4 pagesPsy1830 5196Ilhan Rasya PramudianNo ratings yet

- Bhynchsdlausa4969 8964Document4 pagesBhynchsdlausa4969 8964Vivek LasunaNo ratings yet

- Franz Steiner Verlag Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Historia: Zeitschrift Für Alte GeschichteDocument13 pagesFranz Steiner Verlag Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Historia: Zeitschrift Für Alte GeschichteRafael PinalesNo ratings yet

- Psy7132 8727Document4 pagesPsy7132 8727amira najwaNo ratings yet

- Psy3063 1030Document4 pagesPsy3063 1030Rohan BasnetNo ratings yet

- Chem1338 7296Document4 pagesChem1338 7296Kimchee StudyNo ratings yet

- System4253 7189Document4 pagesSystem4253 7189faizin ahmadNo ratings yet

- Eng2304 7726Document4 pagesEng2304 7726Secure ArvejanNo ratings yet

- Soc4519 2558Document4 pagesSoc4519 2558junopisces22No ratings yet

- Eng914 1061Document4 pagesEng914 1061Fajar AlfNo ratings yet

- Acc9500 2291Document4 pagesAcc9500 2291Noodles CaptNo ratings yet

- Eng6364 4615Document4 pagesEng6364 4615toko16bitNo ratings yet

- CELTIC MYTHOLOGY (Illustrated Edition): The Legacy of Celts: History, Religion, Archeological Finds, Legends & MythsFrom EverandCELTIC MYTHOLOGY (Illustrated Edition): The Legacy of Celts: History, Religion, Archeological Finds, Legends & MythsNo ratings yet

- Phys5659 2716Document4 pagesPhys5659 2716Alejandro Contreras mejiaNo ratings yet

- Psych Ass - 26019 - 9932Document4 pagesPsych Ass - 26019 - 9932Krisskross CastanedaNo ratings yet

- Eng1710 1103Document4 pagesEng1710 1103Jennifer AdvientoNo ratings yet

- The Source of Jugurtha's Influence in The Roman SenateDocument4 pagesThe Source of Jugurtha's Influence in The Roman SenatehNo ratings yet

- Assignment4182 3020Document4 pagesAssignment4182 3020DedeNo ratings yet

- Dagli Altari Alla Polvere.' Alaric, Constantine III, and The Downfall of StilichoDocument18 pagesDagli Altari Alla Polvere.' Alaric, Constantine III, and The Downfall of StilichoЛазар СрећковићNo ratings yet

- Psy5750 3681Document4 pagesPsy5750 3681Kathleen Ivy AlfecheNo ratings yet

- Psy1035 2166Document4 pagesPsy1035 2166Mayank ShankarNo ratings yet

- Kappa DRMWN8801 - 2297Document4 pagesKappa DRMWN8801 - 2297Mey WalfordNo ratings yet

- Borg Review On MathewsDocument5 pagesBorg Review On MathewsΣπύρος ΑNo ratings yet

- D. Talbot Rice 1932 Trebizond A Mediaeval Citadel and PalaceDocument9 pagesD. Talbot Rice 1932 Trebizond A Mediaeval Citadel and PalaceΣπύρος ΑNo ratings yet

- Wilson USSRDocument22 pagesWilson USSRΣπύρος ΑNo ratings yet

- Three Portrait GemsDocument14 pagesThree Portrait GemsΣπύρος ΑNo ratings yet

- Roman World, επιμ., Gavrielatos A., 208-39. NewcastleDocument5 pagesRoman World, επιμ., Gavrielatos A., 208-39. NewcastleΣπύρος ΑNo ratings yet

- A Late Antique Imperial Portrait Recently Discovered at IstanbulDocument6 pagesA Late Antique Imperial Portrait Recently Discovered at IstanbulΣπύρος ΑNo ratings yet

- Again The Carmagnola PDFDocument8 pagesAgain The Carmagnola PDFΣπύρος ΑNo ratings yet

- Orthodox Cosmology and Cosmography The Iconographic Mandorla As Imago MundiDocument18 pagesOrthodox Cosmology and Cosmography The Iconographic Mandorla As Imago MundiΣπύρος Α100% (1)

- Society For The Promotion of Roman StudiesDocument2 pagesSociety For The Promotion of Roman StudiesΣπύρος ΑNo ratings yet

- The Ghost of Athens in Byzantine and Ottoman TimesDocument111 pagesThe Ghost of Athens in Byzantine and Ottoman TimesΣπύρος ΑNo ratings yet

- Emcee ScriptDocument6 pagesEmcee ScriptJasper MomoNo ratings yet

- Tekken Corporation: Company GuideDocument9 pagesTekken Corporation: Company Guidehout rothanaNo ratings yet

- IELTS Advantage Reading SkillsDocument153 pagesIELTS Advantage Reading SkillsĐặng Minh QuânNo ratings yet

- Final ExamDocument3 pagesFinal ExamFaidah PangandamanNo ratings yet

- Document Analysis Worksheet: Analyze A PaintingDocument4 pagesDocument Analysis Worksheet: Analyze A PaintingPatrick SanchezNo ratings yet

- The Literature of Bibliometrics Scientometrics and Informetrics-2Document24 pagesThe Literature of Bibliometrics Scientometrics and Informetrics-2Juan Ruiz-UrquijoNo ratings yet

- Reasons For Decision-Appeal Judgment-Mandaya Thomas-V - The QueenDocument4 pagesReasons For Decision-Appeal Judgment-Mandaya Thomas-V - The QueenBernewsAdminNo ratings yet

- Brakes MCQDocument8 pagesBrakes MCQSathistrnpcNo ratings yet

- Motion Regarding Admission of Out of Court Statement 1Document2 pagesMotion Regarding Admission of Out of Court Statement 1WXMINo ratings yet

- Dark Souls 3 Lore - Father Ariandel & Sister Friede - VaatividyaDocument5 pagesDark Souls 3 Lore - Father Ariandel & Sister Friede - VaatividyashaunNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5Document36 pagesChapter 5nsominvz345No ratings yet

- Medical Importance of CulicoidesDocument15 pagesMedical Importance of Culicoidesadira64100% (1)

- Standard Precautions Knowledge and Practice Among Radiographers in Sri LankaDocument8 pagesStandard Precautions Knowledge and Practice Among Radiographers in Sri LankaSachin ParamashettiNo ratings yet

- The Manchester Gamba BookDocument180 pagesThe Manchester Gamba BookFredrik Hildebrand100% (2)

- Zikr-e-Masoom (A.s.)Document262 pagesZikr-e-Masoom (A.s.)Shian-e-Ali Network0% (1)

- Role of Agnikarma in Pain ManagementDocument9 pagesRole of Agnikarma in Pain ManagementPoonam KailoriaNo ratings yet

- Eric Moses Et AlDocument7 pagesEric Moses Et AlEmily BabayNo ratings yet

- A Term Paper On Justice Holmes'S Concept of Law: Adjunct Faculty Mr. Dev Mahat Nepal Law CampusDocument4 pagesA Term Paper On Justice Holmes'S Concept of Law: Adjunct Faculty Mr. Dev Mahat Nepal Law Campusrahul jhaNo ratings yet

- RPH Latest f2 28 and 29 FEB OBSERVEDocument1 pageRPH Latest f2 28 and 29 FEB OBSERVEFaryz Tontok Tinan 오빠No ratings yet

- CME Applique TutorialDocument20 pagesCME Applique TutorialMarittaKarmaNo ratings yet

- Grail Quest 4Document123 pagesGrail Quest 4Tamás Viktor TariNo ratings yet

- Holiday Assignment - GR12 EnglishDocument3 pagesHoliday Assignment - GR12 Englishabhishektatu2007No ratings yet

- Mahadasa Fal For AllDocument5 pagesMahadasa Fal For AllPawan AgrawalNo ratings yet

- HealthcareStudentWorkbook XIIDocument130 pagesHealthcareStudentWorkbook XIIRobin McLarenNo ratings yet