Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Catherine Belton (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2020), 624, Notes, Illustrations, Index

Catherine Belton (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2020), 624, Notes, Illustrations, Index

Uploaded by

Alex MurphyCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Dmitri Trenin - Russia-Polity (2019)Document196 pagesDmitri Trenin - Russia-Polity (2019)Serenas GroupNo ratings yet

- Blowing up Russia: The Book that Got Litvinenko MurderedFrom EverandBlowing up Russia: The Book that Got Litvinenko MurderedNo ratings yet

- Senarai Lembangan Sungai Utama Di MalaysiaDocument11 pagesSenarai Lembangan Sungai Utama Di MalaysiaazirawaniNo ratings yet

- The Shadow of Ryazan: Executive SummaryDocument19 pagesThe Shadow of Ryazan: Executive Summarysweetsour22No ratings yet

- BB Assassinated Hope LostDocument189 pagesBB Assassinated Hope LostSyed Raza AliNo ratings yet

- How To Read Vladimir Putin MindDocument5 pagesHow To Read Vladimir Putin MindSakeẗ JḧaNo ratings yet

- Strongman: Vladimir Putin and The Struggle For Russia), Translated by AlinaDocument7 pagesStrongman: Vladimir Putin and The Struggle For Russia), Translated by AlinaMarian DragosNo ratings yet

- Exile - Kremlin Clan WarfareDocument5 pagesExile - Kremlin Clan WarfareScott JohnsonNo ratings yet

- Books Reviews Rjhis 2 (1) 2015Document6 pagesBooks Reviews Rjhis 2 (1) 2015Marian DragosNo ratings yet

- The New Nobility The Restoration of Russias Security State and The Enduring Legacy of The KGB (Andrei Soldatov Irina Borogan) (Z-Library)Document351 pagesThe New Nobility The Restoration of Russias Security State and The Enduring Legacy of The KGB (Andrei Soldatov Irina Borogan) (Z-Library)Tobi LawaniNo ratings yet

- Putin and His OligarchsDocument6 pagesPutin and His OligarchsRaNo ratings yet

- The Putin Regime Cracks: Tatiana StanovayaDocument11 pagesThe Putin Regime Cracks: Tatiana StanovayaRiana TeifukovaNo ratings yet

- Vladimir PutinDocument45 pagesVladimir Putinbenmack100% (1)

- KremlinologyDocument30 pagesKremlinologyFrau A. Dekadenz100% (1)

- 06 - Russia's New NobilityDocument10 pages06 - Russia's New NobilityAlberto CerqueiraNo ratings yet

- russ.12666Document2 pagesruss.12666Bình Lê vũNo ratings yet

- Bouwmeester Putinsinsaneexpedition 2023Document6 pagesBouwmeester Putinsinsaneexpedition 2023Hari LeeNo ratings yet

- The Ukraine War Has Revealed The Putin Regime Essay Midterm - 9252Document6 pagesThe Ukraine War Has Revealed The Putin Regime Essay Midterm - 9252Imeth Santhuka RupathungaNo ratings yet

- Russian-Influence-In-European-Policies - Content File PDFDocument8 pagesRussian-Influence-In-European-Policies - Content File PDFolha lapanNo ratings yet

- Tucker Carlson Promised An Unedited Putin. The Result Was Boring - The New YorkerDocument11 pagesTucker Carlson Promised An Unedited Putin. The Result Was Boring - The New YorkerFélix Santiago-MartínezNo ratings yet

- Putin Poses As DefenderDocument6 pagesPutin Poses As DefenderRafaelNo ratings yet

- Agents of Influence: How the KGB Subverted Western DemocraciesFrom EverandAgents of Influence: How the KGB Subverted Western DemocraciesNo ratings yet

- The New Spy WarsDocument6 pagesThe New Spy Warsijaz AhmadNo ratings yet

- The Kremlin's Noose: Putin's Bitter Feud with the Oligarch Who Made Him Ruler of RussiaFrom EverandThe Kremlin's Noose: Putin's Bitter Feud with the Oligarch Who Made Him Ruler of RussiaNo ratings yet

- Putins RussiaDocument24 pagesPutins Russiakelvin wachiraNo ratings yet

- FT Putin ProfileDocument6 pagesFT Putin ProfileArmin NiknamNo ratings yet

- MY BLOG DR OLGA LAZIN A Short Psychoanalysis of Vladimir Putin & His Style of NegotiationDocument17 pagesMY BLOG DR OLGA LAZIN A Short Psychoanalysis of Vladimir Putin & His Style of NegotiationOlga M LazinNo ratings yet

- More of The Same Russian Intelligence During The Post Soviet EraDocument8 pagesMore of The Same Russian Intelligence During The Post Soviet EraMarikNo ratings yet

- Russia's Past Is No Sign of Its FutureDocument2 pagesRussia's Past Is No Sign of Its FutureXxdfNo ratings yet

- The Secret Police of Russia: Neglectful Treatment, Cooperation, and Giving in (2022 Guide for Beginners)From EverandThe Secret Police of Russia: Neglectful Treatment, Cooperation, and Giving in (2022 Guide for Beginners)No ratings yet

- Putinism The IdeologyDocument14 pagesPutinism The IdeologyGiuseppe Paparella100% (1)

- 3014 Contemporary Authortarianism Julian McCallumDocument11 pages3014 Contemporary Authortarianism Julian McCallumjulianNo ratings yet

- G8 Summit in Strelna and The Possibilities of A New Global PoliticsDocument8 pagesG8 Summit in Strelna and The Possibilities of A New Global PoliticsJanNo ratings yet

- The Putin Murders: A Brief History of PutintimeDocument10 pagesThe Putin Murders: A Brief History of PutintimeKosutNo ratings yet

- The Putin Corporation: The Story of Russia's Secret TakeoverFrom EverandThe Putin Corporation: The Story of Russia's Secret TakeoverNo ratings yet

- Wagner Chief's Mutiny in Russia - Cautionary Notes On Early AssessmentsDocument6 pagesWagner Chief's Mutiny in Russia - Cautionary Notes On Early AssessmentsMuhammad Zakria 2371-FET/BSEE/F14No ratings yet

- Who Is Vladimir Putin?: Fiona HillDocument9 pagesWho Is Vladimir Putin?: Fiona HillZineil BlackwoodNo ratings yet

- Ecfr 169 - Putins Hydra Inside The Russian Intelligence Services 1513 PDFDocument20 pagesEcfr 169 - Putins Hydra Inside The Russian Intelligence Services 1513 PDFtayo_bNo ratings yet

- Blowing up Ukraine: The Return of Russian Terror and The Threat of World War IIIFrom EverandBlowing up Ukraine: The Return of Russian Terror and The Threat of World War IIINo ratings yet

- BACK - TO - THE - COLD - WAR Update 140314 (Obama, Putin, Ukraine, Crimea, NATO, European Union)Document170 pagesBACK - TO - THE - COLD - WAR Update 140314 (Obama, Putin, Ukraine, Crimea, NATO, European Union)Maro FentoNo ratings yet

- Resrep10345.6 RUSSIA 26Document13 pagesResrep10345.6 RUSSIA 26Reda HelalNo ratings yet

- Russia-Under-Putin-Toward-Democracy By-Or-DictatorshipDocument6 pagesRussia-Under-Putin-Toward-Democracy By-Or-DictatorshipJúlia IreneNo ratings yet

- Vladimir Putin, Russia's Imperial ImpostorDocument11 pagesVladimir Putin, Russia's Imperial ImpostorMendiburuFranciscoNo ratings yet

- 864 SekifepazuDocument3 pages864 SekifepazuTanmay PrajapatNo ratings yet

- 3000581Document22 pages3000581Gabriel QuintanilhaNo ratings yet

- USSR KT3 FactfileDocument2 pagesUSSR KT3 FactfileMaddieNo ratings yet

- TheWallStreetJournal 20220609 A19 0 TDocument3 pagesTheWallStreetJournal 20220609 A19 0 TVignes AgniNo ratings yet

- USSR Long Range VisionDocument4 pagesUSSR Long Range VisionJeff ScottNo ratings yet

- (DONE) (ANOTADO) Threats To The Existing Global Order. Challenges From The East - John W. Young & John KentDocument22 pages(DONE) (ANOTADO) Threats To The Existing Global Order. Challenges From The East - John W. Young & John KentFrancisco GarcíaNo ratings yet

- The Long, Dark History of Russia's Murder, Inc.: Michael WeissDocument8 pagesThe Long, Dark History of Russia's Murder, Inc.: Michael WeissMira GanchevaNo ratings yet

- KGB Infiltration of Israel Part 1Document5 pagesKGB Infiltration of Israel Part 1Joshua SanchezNo ratings yet

- Putin's Virtual War: Russia's Subversion and Conversion of America, Europe and the World BeyondFrom EverandPutin's Virtual War: Russia's Subversion and Conversion of America, Europe and the World BeyondRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- How Vladimir Putin Got Ukraine Wrong - The Washington PostDocument5 pagesHow Vladimir Putin Got Ukraine Wrong - The Washington PostNicole BalkhuysenNo ratings yet

- New Cold Wars: China’s rise, Russia’s invasion, and America’s struggle to defend the WestFrom EverandNew Cold Wars: China’s rise, Russia’s invasion, and America’s struggle to defend the WestNo ratings yet

- Ranielle Joshua C. Manalo: EmailDocument3 pagesRanielle Joshua C. Manalo: EmailJOSHUAMANALO TvNo ratings yet

- Analisis Kimia SPM Kedah 2017Document56 pagesAnalisis Kimia SPM Kedah 2017ismalindaNo ratings yet

- 2nd Form End Term 1-2023 - Science NOURDocument5 pages2nd Form End Term 1-2023 - Science NOURIsland3 TulipsNo ratings yet

- Jinggoy EstradaDocument9 pagesJinggoy EstradaJustine June DuranaNo ratings yet

- SSG Mandated - PPAs - AND - COAsDocument46 pagesSSG Mandated - PPAs - AND - COAsRex LubangNo ratings yet

- Bài tập cơ bản và nâng cao Tiếng Anh 4 UNIT 1Document7 pagesBài tập cơ bản và nâng cao Tiếng Anh 4 UNIT 1Hoàng VânnNo ratings yet

- Bathabile Dlamini's Resignation LetterDocument8 pagesBathabile Dlamini's Resignation LetterMashadi Kekana100% (2)

- Fall 2022-23 P4 Listening and Note-Taking Practice - StudentDocument11 pagesFall 2022-23 P4 Listening and Note-Taking Practice - StudentCeylin Damla OzdilNo ratings yet

- Score SheetDocument12 pagesScore Sheetdenisse gaboNo ratings yet

- Lising, Alliana Czariel C. Macabanti, Patricia Janelle P.: ST RD TH THDocument1 pageLising, Alliana Czariel C. Macabanti, Patricia Janelle P.: ST RD TH THpatricia macabantiNo ratings yet

- National Anthem EnglandDocument13 pagesNational Anthem Englandapi-556082157No ratings yet

- Will The Liberal Order Survive?: The History of An IdeaDocument14 pagesWill The Liberal Order Survive?: The History of An IdeaJuan DíazNo ratings yet

- Reinelt Janelle Beyond BrechtDocument11 pagesReinelt Janelle Beyond BrechtMau VBNo ratings yet

- SM-VIII-Understanding Dynamics of Power and PoliticsDocument27 pagesSM-VIII-Understanding Dynamics of Power and Politicsbharat bhatNo ratings yet

- Indias DemocraciesDocument253 pagesIndias DemocraciesAnil KumarNo ratings yet

- American Stories A History of The United States Combined Volume 1 and 2 1st Edition Brands Solutions ManualDocument24 pagesAmerican Stories A History of The United States Combined Volume 1 and 2 1st Edition Brands Solutions ManualMichaelKimkqjp100% (57)

- Argument SheetDocument124 pagesArgument SheetadmondalNo ratings yet

- Flyer The Queens Commonwealth Essay Competition 2021Document2 pagesFlyer The Queens Commonwealth Essay Competition 2021velangniNo ratings yet

- M.A. Degree Examination - 2013: 651. Government and Politics of Tamil Nadu Since 1900Document2 pagesM.A. Degree Examination - 2013: 651. Government and Politics of Tamil Nadu Since 1900themustwatchNo ratings yet

- 1st Merit List Ma SociologyDocument15 pages1st Merit List Ma Sociologyacct offr maduraiNo ratings yet

- Comparative Cultural StudiesDocument4 pagesComparative Cultural StudiesAwmi Khiangte100% (1)

- Ap Finance Go PDFDocument3 pagesAp Finance Go PDFSuresh Babu ChinthalaNo ratings yet

- Shs NCR EditDocument8 pagesShs NCR EditAmarieDMNo ratings yet

- Class:-10 Democratic Politics Term 2:-Political PartiesDocument4 pagesClass:-10 Democratic Politics Term 2:-Political PartiesSURAJ RAIKARNo ratings yet

- Port Klang Safe Zone (PKSZ) Group 3: Name Matrics NumberDocument18 pagesPort Klang Safe Zone (PKSZ) Group 3: Name Matrics NumberKishore KumarNo ratings yet

- Writing A Biography WorksheetDocument4 pagesWriting A Biography WorksheetDOLLY MARCELA GUTIERREZ CORTESNo ratings yet

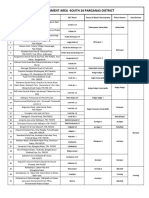

- Containment Area - South 24 Parganas DistrictDocument2 pagesContainment Area - South 24 Parganas DistrictShraddha ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

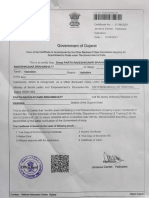

- Scan 12 Apr 2021-CompressedDocument1 pageScan 12 Apr 2021-CompressedParth BrahmbhattNo ratings yet

Catherine Belton (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2020), 624, Notes, Illustrations, Index

Catherine Belton (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2020), 624, Notes, Illustrations, Index

Uploaded by

Alex MurphyOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Catherine Belton (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2020), 624, Notes, Illustrations, Index

Catherine Belton (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2020), 624, Notes, Illustrations, Index

Uploaded by

Alex MurphyCopyright:

Available Formats

Intelligence in Public Media

Putin’s People: How the KGB Took Back Russia and Then Took on the West

Catherine Belton (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2020), 624, notes, illustrations, index.

Reviewed by Matthew J.

In 1954, the Soviet Union created the Committee for gave him status among two of the most important ele-

State Security (KGB) and, as the Cold War intensified, ments in Russian society at the end of the Soviet Union:

the service grew in capability and status, advancing the pro-democracy advocates and the old guard of the KGB,

Kremlin’s interests around the world and stifling dissent who now held sway in the Federal Security Service

at home. The “sword and shield” of the Communist (FSB) and the Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR).

Party—as the organization became known—ceased Political reformers respected Putin’s close relationship

to exist in the wake of the 1991 collapse of the Soviet with Sobchak, while members of the security services

Union, but Catherine Belton demonstrates in Putin’s understood that Putin remained “one of them.” Belton

People that remnants of the KGB remain alive and well. notes that, “true to his KGB training, Putin had reflected

everyone’s views back to them like a mirror: first those

A former Moscow-based reporter for the Financial of his new so-called democratic master, and then those

Times, Belton tells the story of how Russian intelligence of the old-guard establishment he worked with, too. He

officers, particularly Vladimir Putin, maneuvered from would change his colours so fast you could never tell who

the shadows to the corridors of power. Belton begins by he really was.” (49)

tracing Putin’s early years in the KGB and his posting to

Dresden, East Germany, in 1985. While conceding that In 1996, Sobchak lost his reelection bid and Putin

much is still unknown about his time there, Belton argues, moved on from St. Petersburg, taking an administrative

primarily on the basis of interviews, that Putin and the position in the Kremlin for the Boris Yeltsin government.

KGB did much more than just meet with the Stasi and Once in Moscow, he experienced what Belton describes

recruit sources. In her telling, KGB officers in Dresden as a “dizzying rise.” (112) Yeltsin’s aides viewed him as

worked to implement active measures against the West a skillful bureaucrat and within just two years, Yeltsin

by supporting the Red Army Faction. At the very least, appointed Putin to head the FSB. Putin’s stock rose just as

Putin’s time in Germany helped Russia’s future leader Yeltsin’s health, and political standing, declined. Belton’s

cement connections in the intelligence world that later chapter on the political dynamics surrounding Putin’s

helped propel him to the presidency. ascension, “Operation Successor,” is quite good, as she

clearly lays out how—following the dismissal of Prime

Shortly after the fall of the Berlin Wall, Putin was back Minister Yevgeny Primakov, a former head of the KGB—

in Russia and went to Leningrad (which soon afterward Yeltsin was looking for a strong figure with a security

reverted to its original name, St. Petersburg). The KGB background to serve as his second-in-command. Putin

assigned him to work undercover in the rector’s office fit the bill, becoming prime minister in August, 1999,

at Leningrad State University, and he quickly connected and when Yeltsin resigned at the end of that year, he was

with a former professor from his student days, Anatoly named acting president of Russia. One of Yeltsin’s aides

Sobchak. Putin became part of the inner circle and when recalls receiving a warning from Putin’s own mentor,

Sobchak, a key leader in the democracy movement Anatoly Sobchak, about elevating the former KGB man:

sweeping the country, became mayor in June 1991 their “This is the biggest mistake of your life. He comes from

relationship became very important. It is at this point a tainted circle. A komitechik [committee man] cannot

that Belton’s thesis becomes clear: rather than trying to change. You don’t understand who Putin is.” (149)

forestall the Soviet Union’s tilt towards democracy, some

former KGB officers sought to co-opt the movement. Following Putin’s electoral victory in the March

Putin rose to serve as one of the mayor’s deputies and 2000 presidential election, the halls of the Kremlin were

as Belton writes, “Sobchak came to rely on Putin, who littered with former intelligence officials who came with

maintained a network of connections with the top of the the new president from St. Petersburg: Nikolai Patrushev,

city’s [former] KGB.” (87) Putin’s time in St. Petersburg Sergei Ivanov, and Igor Sechin, just to name a few. While

All statements of fact, opinion, or analysis expressed in this article are those of the author. Nothing in the article should be con-

strued as asserting or implying US government endorsement of its factual statements and interpretations.

Studies in Intelligence Vol 64, No. 4 (Extracts, December 2020) 43

Putin’s People

Belton writes that “for the first few years of Putin’s pres- Kremlin-aligned oligarchs looked to Western banks and

idency, these Leningrad KGB men . . . shared an uneasy financial institutions to continue growing their portfolios.

power with the holdovers from the Yelstin regime,” fairly Belton titles one chapter “Londongrad” and argues that

quickly Putin went after the press and oligarchs. (187) He the “companies coming to London were now mainly the

expressed outrage after receiving negative media cov- new behemoths of Putin’s state capitalism, which had

erage for his handling of the Kursk submarine incident zero interest in liberalizing the Russian economy.” (351)

and sought to eliminate the editorial independence of In Belton’s view, Western leaders and institutions were

key Russian media outlets. The Putin regime also tar- too accepting of Russian businessmen, many of whom

geted Mikhail Khodorkovsky, the richest man in Russia were doing the bidding of the Kremlin, writing that

and head of the powerful Yukos oil company, who was “emboldened by the apparent Cold War victory, and the

seeking to integrate his business interests with Western expansion of the European Union into the countries of the

partners, which Putin probably feared meant Western former Eastern Bloc, the West believed in Russia’s global

encroachment on Russia’s energy sector. The conviction integration and opened its markets even wider to it.” (349)

of Khodorkovsky on fraud charges sent a signal that in In fact, the West’s failure to understand that post-Soviet

Putin’s Russia, oligarchs could exist, but they would serve Russia had been become dominated by former KGB offi-

the interests of the state. cers committed to manipulating the economy to help fund

their operations abroad in order to reassert the Kremlin’s

Putin also looked to reestablish Russia as a region- role in the global order is a key theme of Belton’s book.

al power, building “a bridge to its imperial past” as

Belton writes. (273) Putin’s Kremlin focused intently on On balance, this is a useful and thought-provoking

keeping Ukraine within its orbit and when in 2004 the book on the trajectory of post-Soviet Russia and the con-

Orange Revolution prevented a pro-Russian leader from tinued influence of the KGB inside the Kremlin. Belton

taking power in Kiev, Putin was incensed, viewing the probably goes too far at times, though, particularly when

events as being orchestrated by the United States and describing the collapse of the Soviet Union as a byprod-

West European powers. A decade later, following the uct of a coordinated KGB plan to take power (the subject

Euromaidan demonstrations that overthrew a pro-Russian of chapter 2). The truth is more complicated, owing

government in Ukraine, Putin had seen enough. He sent to political realities, economic decline, and, at times,

forces into Crimea, eventually annexing the peninsula happenstance. However, Belton is on much safer ground

and, in August 2014, Russian security services helped with the argument that Putin and his fellow KGB alums

foment an uprising in eastern Ukraine. Belton adeptly have been adept at taking advantage of political oppor-

illustrates how the Kremlin utilized private business to tunities. In explaining the ability of former KGB officers

covertly project power into Ukraine, a hallmark of how to navigate post-Soviet Russia, Belton’s quoting Thomas

the KGB previously waged the Cold War and how Putin’s Graham, former senior director for Russia at the US

Russia now approached foreign policy. The Kremlin National Security Council, is instructive: “The institutions

relied on Konstantin Malofeyev, a Russian businessman the security men worked in did not break down . . . the

who became a billionaire in the 2000s. Belton writes that personal networks did not disappear. What they needed

Malofeyev “was in the middle of it all . . . [his] former simply was an individual who could bring these networks

security chief . . . led the ad hoc Russian forces arriving back together.” (153) Ultimately, trying to understand

in East Ukraine from Crimea . . . [and] Malofeyev was what motivates the top man in the Kremlin will always be

believed to be the linchpin in funneling cash to pro-Krem- a challenge and as Putin begins his third decade in ruling

lin separatists, working through a network of charities.” Russia, Belton’s look back at how he took power and has

(425–26) wielded influence can be instructive for both intelligence

professionals and policymakers.

The final chapters of Putin’s People cover Moscow’s

saturating Western capitals with Russian money, as

v v v

The reviewer: Matthew J. serves in the Office of the Director of National Intelligence.

44 Studies in Intelligence Vol 64, No. 4 (Extracts, December 2020)

You might also like

- Dmitri Trenin - Russia-Polity (2019)Document196 pagesDmitri Trenin - Russia-Polity (2019)Serenas GroupNo ratings yet

- Blowing up Russia: The Book that Got Litvinenko MurderedFrom EverandBlowing up Russia: The Book that Got Litvinenko MurderedNo ratings yet

- Senarai Lembangan Sungai Utama Di MalaysiaDocument11 pagesSenarai Lembangan Sungai Utama Di MalaysiaazirawaniNo ratings yet

- The Shadow of Ryazan: Executive SummaryDocument19 pagesThe Shadow of Ryazan: Executive Summarysweetsour22No ratings yet

- BB Assassinated Hope LostDocument189 pagesBB Assassinated Hope LostSyed Raza AliNo ratings yet

- How To Read Vladimir Putin MindDocument5 pagesHow To Read Vladimir Putin MindSakeẗ JḧaNo ratings yet

- Strongman: Vladimir Putin and The Struggle For Russia), Translated by AlinaDocument7 pagesStrongman: Vladimir Putin and The Struggle For Russia), Translated by AlinaMarian DragosNo ratings yet

- Exile - Kremlin Clan WarfareDocument5 pagesExile - Kremlin Clan WarfareScott JohnsonNo ratings yet

- Books Reviews Rjhis 2 (1) 2015Document6 pagesBooks Reviews Rjhis 2 (1) 2015Marian DragosNo ratings yet

- The New Nobility The Restoration of Russias Security State and The Enduring Legacy of The KGB (Andrei Soldatov Irina Borogan) (Z-Library)Document351 pagesThe New Nobility The Restoration of Russias Security State and The Enduring Legacy of The KGB (Andrei Soldatov Irina Borogan) (Z-Library)Tobi LawaniNo ratings yet

- Putin and His OligarchsDocument6 pagesPutin and His OligarchsRaNo ratings yet

- The Putin Regime Cracks: Tatiana StanovayaDocument11 pagesThe Putin Regime Cracks: Tatiana StanovayaRiana TeifukovaNo ratings yet

- Vladimir PutinDocument45 pagesVladimir Putinbenmack100% (1)

- KremlinologyDocument30 pagesKremlinologyFrau A. Dekadenz100% (1)

- 06 - Russia's New NobilityDocument10 pages06 - Russia's New NobilityAlberto CerqueiraNo ratings yet

- russ.12666Document2 pagesruss.12666Bình Lê vũNo ratings yet

- Bouwmeester Putinsinsaneexpedition 2023Document6 pagesBouwmeester Putinsinsaneexpedition 2023Hari LeeNo ratings yet

- The Ukraine War Has Revealed The Putin Regime Essay Midterm - 9252Document6 pagesThe Ukraine War Has Revealed The Putin Regime Essay Midterm - 9252Imeth Santhuka RupathungaNo ratings yet

- Russian-Influence-In-European-Policies - Content File PDFDocument8 pagesRussian-Influence-In-European-Policies - Content File PDFolha lapanNo ratings yet

- Tucker Carlson Promised An Unedited Putin. The Result Was Boring - The New YorkerDocument11 pagesTucker Carlson Promised An Unedited Putin. The Result Was Boring - The New YorkerFélix Santiago-MartínezNo ratings yet

- Putin Poses As DefenderDocument6 pagesPutin Poses As DefenderRafaelNo ratings yet

- Agents of Influence: How the KGB Subverted Western DemocraciesFrom EverandAgents of Influence: How the KGB Subverted Western DemocraciesNo ratings yet

- The New Spy WarsDocument6 pagesThe New Spy Warsijaz AhmadNo ratings yet

- The Kremlin's Noose: Putin's Bitter Feud with the Oligarch Who Made Him Ruler of RussiaFrom EverandThe Kremlin's Noose: Putin's Bitter Feud with the Oligarch Who Made Him Ruler of RussiaNo ratings yet

- Putins RussiaDocument24 pagesPutins Russiakelvin wachiraNo ratings yet

- FT Putin ProfileDocument6 pagesFT Putin ProfileArmin NiknamNo ratings yet

- MY BLOG DR OLGA LAZIN A Short Psychoanalysis of Vladimir Putin & His Style of NegotiationDocument17 pagesMY BLOG DR OLGA LAZIN A Short Psychoanalysis of Vladimir Putin & His Style of NegotiationOlga M LazinNo ratings yet

- More of The Same Russian Intelligence During The Post Soviet EraDocument8 pagesMore of The Same Russian Intelligence During The Post Soviet EraMarikNo ratings yet

- Russia's Past Is No Sign of Its FutureDocument2 pagesRussia's Past Is No Sign of Its FutureXxdfNo ratings yet

- The Secret Police of Russia: Neglectful Treatment, Cooperation, and Giving in (2022 Guide for Beginners)From EverandThe Secret Police of Russia: Neglectful Treatment, Cooperation, and Giving in (2022 Guide for Beginners)No ratings yet

- Putinism The IdeologyDocument14 pagesPutinism The IdeologyGiuseppe Paparella100% (1)

- 3014 Contemporary Authortarianism Julian McCallumDocument11 pages3014 Contemporary Authortarianism Julian McCallumjulianNo ratings yet

- G8 Summit in Strelna and The Possibilities of A New Global PoliticsDocument8 pagesG8 Summit in Strelna and The Possibilities of A New Global PoliticsJanNo ratings yet

- The Putin Murders: A Brief History of PutintimeDocument10 pagesThe Putin Murders: A Brief History of PutintimeKosutNo ratings yet

- The Putin Corporation: The Story of Russia's Secret TakeoverFrom EverandThe Putin Corporation: The Story of Russia's Secret TakeoverNo ratings yet

- Wagner Chief's Mutiny in Russia - Cautionary Notes On Early AssessmentsDocument6 pagesWagner Chief's Mutiny in Russia - Cautionary Notes On Early AssessmentsMuhammad Zakria 2371-FET/BSEE/F14No ratings yet

- Who Is Vladimir Putin?: Fiona HillDocument9 pagesWho Is Vladimir Putin?: Fiona HillZineil BlackwoodNo ratings yet

- Ecfr 169 - Putins Hydra Inside The Russian Intelligence Services 1513 PDFDocument20 pagesEcfr 169 - Putins Hydra Inside The Russian Intelligence Services 1513 PDFtayo_bNo ratings yet

- Blowing up Ukraine: The Return of Russian Terror and The Threat of World War IIIFrom EverandBlowing up Ukraine: The Return of Russian Terror and The Threat of World War IIINo ratings yet

- BACK - TO - THE - COLD - WAR Update 140314 (Obama, Putin, Ukraine, Crimea, NATO, European Union)Document170 pagesBACK - TO - THE - COLD - WAR Update 140314 (Obama, Putin, Ukraine, Crimea, NATO, European Union)Maro FentoNo ratings yet

- Resrep10345.6 RUSSIA 26Document13 pagesResrep10345.6 RUSSIA 26Reda HelalNo ratings yet

- Russia-Under-Putin-Toward-Democracy By-Or-DictatorshipDocument6 pagesRussia-Under-Putin-Toward-Democracy By-Or-DictatorshipJúlia IreneNo ratings yet

- Vladimir Putin, Russia's Imperial ImpostorDocument11 pagesVladimir Putin, Russia's Imperial ImpostorMendiburuFranciscoNo ratings yet

- 864 SekifepazuDocument3 pages864 SekifepazuTanmay PrajapatNo ratings yet

- 3000581Document22 pages3000581Gabriel QuintanilhaNo ratings yet

- USSR KT3 FactfileDocument2 pagesUSSR KT3 FactfileMaddieNo ratings yet

- TheWallStreetJournal 20220609 A19 0 TDocument3 pagesTheWallStreetJournal 20220609 A19 0 TVignes AgniNo ratings yet

- USSR Long Range VisionDocument4 pagesUSSR Long Range VisionJeff ScottNo ratings yet

- (DONE) (ANOTADO) Threats To The Existing Global Order. Challenges From The East - John W. Young & John KentDocument22 pages(DONE) (ANOTADO) Threats To The Existing Global Order. Challenges From The East - John W. Young & John KentFrancisco GarcíaNo ratings yet

- The Long, Dark History of Russia's Murder, Inc.: Michael WeissDocument8 pagesThe Long, Dark History of Russia's Murder, Inc.: Michael WeissMira GanchevaNo ratings yet

- KGB Infiltration of Israel Part 1Document5 pagesKGB Infiltration of Israel Part 1Joshua SanchezNo ratings yet

- Putin's Virtual War: Russia's Subversion and Conversion of America, Europe and the World BeyondFrom EverandPutin's Virtual War: Russia's Subversion and Conversion of America, Europe and the World BeyondRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- How Vladimir Putin Got Ukraine Wrong - The Washington PostDocument5 pagesHow Vladimir Putin Got Ukraine Wrong - The Washington PostNicole BalkhuysenNo ratings yet

- New Cold Wars: China’s rise, Russia’s invasion, and America’s struggle to defend the WestFrom EverandNew Cold Wars: China’s rise, Russia’s invasion, and America’s struggle to defend the WestNo ratings yet

- Ranielle Joshua C. Manalo: EmailDocument3 pagesRanielle Joshua C. Manalo: EmailJOSHUAMANALO TvNo ratings yet

- Analisis Kimia SPM Kedah 2017Document56 pagesAnalisis Kimia SPM Kedah 2017ismalindaNo ratings yet

- 2nd Form End Term 1-2023 - Science NOURDocument5 pages2nd Form End Term 1-2023 - Science NOURIsland3 TulipsNo ratings yet

- Jinggoy EstradaDocument9 pagesJinggoy EstradaJustine June DuranaNo ratings yet

- SSG Mandated - PPAs - AND - COAsDocument46 pagesSSG Mandated - PPAs - AND - COAsRex LubangNo ratings yet

- Bài tập cơ bản và nâng cao Tiếng Anh 4 UNIT 1Document7 pagesBài tập cơ bản và nâng cao Tiếng Anh 4 UNIT 1Hoàng VânnNo ratings yet

- Bathabile Dlamini's Resignation LetterDocument8 pagesBathabile Dlamini's Resignation LetterMashadi Kekana100% (2)

- Fall 2022-23 P4 Listening and Note-Taking Practice - StudentDocument11 pagesFall 2022-23 P4 Listening and Note-Taking Practice - StudentCeylin Damla OzdilNo ratings yet

- Score SheetDocument12 pagesScore Sheetdenisse gaboNo ratings yet

- Lising, Alliana Czariel C. Macabanti, Patricia Janelle P.: ST RD TH THDocument1 pageLising, Alliana Czariel C. Macabanti, Patricia Janelle P.: ST RD TH THpatricia macabantiNo ratings yet

- National Anthem EnglandDocument13 pagesNational Anthem Englandapi-556082157No ratings yet

- Will The Liberal Order Survive?: The History of An IdeaDocument14 pagesWill The Liberal Order Survive?: The History of An IdeaJuan DíazNo ratings yet

- Reinelt Janelle Beyond BrechtDocument11 pagesReinelt Janelle Beyond BrechtMau VBNo ratings yet

- SM-VIII-Understanding Dynamics of Power and PoliticsDocument27 pagesSM-VIII-Understanding Dynamics of Power and Politicsbharat bhatNo ratings yet

- Indias DemocraciesDocument253 pagesIndias DemocraciesAnil KumarNo ratings yet

- American Stories A History of The United States Combined Volume 1 and 2 1st Edition Brands Solutions ManualDocument24 pagesAmerican Stories A History of The United States Combined Volume 1 and 2 1st Edition Brands Solutions ManualMichaelKimkqjp100% (57)

- Argument SheetDocument124 pagesArgument SheetadmondalNo ratings yet

- Flyer The Queens Commonwealth Essay Competition 2021Document2 pagesFlyer The Queens Commonwealth Essay Competition 2021velangniNo ratings yet

- M.A. Degree Examination - 2013: 651. Government and Politics of Tamil Nadu Since 1900Document2 pagesM.A. Degree Examination - 2013: 651. Government and Politics of Tamil Nadu Since 1900themustwatchNo ratings yet

- 1st Merit List Ma SociologyDocument15 pages1st Merit List Ma Sociologyacct offr maduraiNo ratings yet

- Comparative Cultural StudiesDocument4 pagesComparative Cultural StudiesAwmi Khiangte100% (1)

- Ap Finance Go PDFDocument3 pagesAp Finance Go PDFSuresh Babu ChinthalaNo ratings yet

- Shs NCR EditDocument8 pagesShs NCR EditAmarieDMNo ratings yet

- Class:-10 Democratic Politics Term 2:-Political PartiesDocument4 pagesClass:-10 Democratic Politics Term 2:-Political PartiesSURAJ RAIKARNo ratings yet

- Port Klang Safe Zone (PKSZ) Group 3: Name Matrics NumberDocument18 pagesPort Klang Safe Zone (PKSZ) Group 3: Name Matrics NumberKishore KumarNo ratings yet

- Writing A Biography WorksheetDocument4 pagesWriting A Biography WorksheetDOLLY MARCELA GUTIERREZ CORTESNo ratings yet

- Containment Area - South 24 Parganas DistrictDocument2 pagesContainment Area - South 24 Parganas DistrictShraddha ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- Scan 12 Apr 2021-CompressedDocument1 pageScan 12 Apr 2021-CompressedParth BrahmbhattNo ratings yet