Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Journal 2 Gaming Adiction

Journal 2 Gaming Adiction

Uploaded by

Ilham PrayogoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal 2 Gaming Adiction

Journal 2 Gaming Adiction

Uploaded by

Ilham PrayogoCopyright:

Available Formats

Research

JAMA Psychiatry | Original Investigation

Efficacy of Short-term Treatment of Internet and Computer

Game Addiction

A Randomized Clinical Trial

Klaus Wölfling, PhD; Kai W. Müller, PhD; Michael Dreier, Dipl-Soz; Christian Ruckes, Dipl-Math;

Oliver Deuster, PhD; Anil Batra, MD; Karl Mann, MD; Michael Musalek, MD; Andreas Schuster, PhD;

Tagrid Lemenager, PhD; Sara Hanke, Dipl-Psych; Manfred E. Beutel, MD

Author Audio Interview

IMPORTANCE Internet and computer game addiction represent a growing mental health Supplemental content

concern, acknowledged by the World Health Organization.

OBJECTIVE To determine whether manualized cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), using

short-term treatment for internet and computer game addiction (STICA), is efficient in

individuals experiencing internet and computer game addiction.

DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS A multicenter randomized clinical trial was conducted in

4 outpatient clinics in Germany and Austria from January 24, 2012, to June 14, 2017, including

follow-ups. Blinded measurements were conducted. A consecutive sample of 143 men was

randomized to the treatment group (STICA; n = 72) or wait-list control (WLC) group (n = 71).

Main inclusion criteria were male sex and internet addiction as the primary diagnosis. The

STICA group had an additional 6-month follow-up (n = 36). Data were analyzed from

November 2018 to March 2019.

INTERVENTIONS The manualized CBT program aimed to recover functional internet use.

The program consisted of 15 weekly group and up to 8 two-week individual sessions.

MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES The predefined primary outcome was the Assessment

of Internet and Computer Game Addiction Self-report (AICA-S). Secondary outcomes were

self-reported internet addiction symptoms, time spent online on weekdays, psychosocial

functioning, and depression.

RESULTS A total of 143 men (mean [SD] age, 26.2 [7.8] years) were analyzed based on

intent-to-treat analyses. Of these participants, 50 of 72 men (69.4%) in the STICA group

showed remission vs 17 of 71 men (23.9%) in the WLC group. In logistic regression analysis,

remission in the STICA vs WLC group was higher (odds ratio, 10.10; 95% CI, 3.69-27.65),

taking into account internet addiction baseline severity, comorbidity, treatment center, and

age. Compared with the WLC groups, effect sizes at treatment termination of STICA were

d = 1.19 for AICA-S, d = 0.88 for time spent online on weekdays, d = 0.64 for psychosocial

functioning, and d = 0.67 for depression. Fourteen adverse events and 8 serious adverse

events occurred. A causal relationship with treatment was considered likely in 2 AEs, one in

each group.

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE Short-term treatment for internet and computer game

addiction is a promising, manualized, short-term CBT for a broad range of internet addictions Author Affiliations: Author

affiliations are listed at the end of this

in multiple treatment centers. Further trials investigating the long-term efficacy of STICA

article.

and addressing specific groups and subgroups compared with active control conditions

Corresponding Author: Klaus

are required. Wölfling, PhD, Outpatient Clinic for

Behavioral Addictions, Department

TRIAL REGISTRATION ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01434589 of Psychosomatic Medicine and

Psychotherapy, University Medical

Center of the Johannes

Gutenberg-University Mainz,

Untere Zahlbacher Str. 8, 55131

JAMA Psychiatry. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.1676 Mainz, Germany (woelfling@

Published online July 10, 2019. uni-mainz.de).

(Reprinted) E1

© 2019 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ by a Idaho State University User on 07/17/2019

Research Original Investigation Efficacy of Short-term Treatment of Internet and Computer Game Addiction

I

n 2013, internet gaming disorder was included in the DSM-5

as a condition warranting further research.1 Similar to gam- Key Points

bling disorder,2 criteria encompass preoccupation, with-

Question Is manualized cognitive behavioral short-term therapy

drawal, tolerance, and continued use despite negative conse- an efficient treatment of internet and computer game addiction?

quences. Based on the growing scientific evidence, gaming

Findings In this randomized clinical trial of 143 men, a strong

disorder has recently been introduced as a new diagnosis in

remission rate for internet and computer game addiction was

the International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision, in

noted with cognitive behavioral therapy in the treatment group vs

the section Disorders Due to Substance Use or Addictive a wait-list control group.

Behaviors.3 Other subtypes of internet addiction (IA) will be

Meaning Short-term CBT treatment in outpatient settings

classified as “other specified disorders due to addictive

addressing internet and computer game addiction is effective.

behav iours.” 3 A broad concept of IA was disc ussed

contentiously.4 Notwithstanding, there is also support for a

broader concept.5

The broader concept of IA represents a manifestation of spe- ment for internet and computer game addiction (STICA), a

cific activities in the internet, which might be gaming; the use manualized CBT program combining group and individual

of social network services, such as chats; surfing sites provid- interventions.19,20 The STICA method had been successfully

ing pornographic material; participation in gambling; collect- pretested in a pilot study with 42 patients with IA.20 Pre-post

ing as well as streaming videos or movies; excessive shopping; effect sizes on our main outcome, the scale for the Assess-

or aimless gathering or searching for information. Internet ad- ment of Internet and Computer Game Addiction (AICA-S)21

dition is therefore characterized by (1) impaired control regard- were strong (d = 1.0) when based on intent-to-treat analyses.

ing onset, duration, termination, frequency, intensity, and con-

text; (2) an increased priority given to internet applications to

the extent that these tasks take precedence over alternative life

interests as well as daily activities; and (3) escalating activity,

Methods

despite the occurrence of negative consequences. The indi- Study Design and Implementation

cated behavior is sufficiently severe and causes significant im- A multicenter randomized clinical trial was conducted in 4 out-

pairment in family, social, educational, personal, occupa- patient clinics in Germany and Austria from January 24, 2012,

tional, or alternative relevant areas of functioning.3 to June 14, 2017, including follow-ups. Data were analyzed from

It is widely agreed that IA represents a broader concept.5 November 2018 to March 2019. The outpatient clinic for behav-

Different subtypes sharing core features (eg, loss of control, ioral addictions in Mainz, Germany, developed the CBT pro-

craving, salience, preoccupation.) of IA have been proposed, gram based on a long history of treating patients with gam-

such as gaming, social media, and online pornography.5-7 Pro- bling disorder as well as different subtypes of IA: therapy

ponents of a unitary conception of IA have pointed toward simi- modules that proved effective in clinical experience were first

larities in neurobiological and phenomenological sources with summarized in a manual, then tested in a pilot study with a small

other addictive behaviors.8-11 In males, the most frequent sub- sample size and pre-post design.22 Findings were promising and

type of IA is internet gaming disorder.12 Many empirical find- gave impetus for the design in the present STICA study.

ings on neurobiological mechanisms have supported the con- The study protocol (available in Supplement 1) was ap-

cept of behavioral addiction.8,10,11 proved by the ethics committee of the State Chamber of Medi-

A growing body of research has indicated high preva- cine in Rhineland-Palatinate and the local ethics committees

lence rates for IA of 3% to 6%.13 Epidemiologic studies and data at each site. According to a standardized protocol, an elec-

from predominantly male treatment seekers have linked IA to tronic clinical report form was implemented. Data were docu-

psychosocial problems, psychopathologic disorders, poor mented, monitored, and stored in a database by the Interdis-

physical health, and decreased quality of life.12-15 ciplinary Center for Clinical Trials Mainz, which conducted data

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has been suggested for analyses. Serious adverse events were reported within 24

the treatment of IA, addressing dysfunctional cognitions, so- hours, which is independent of the participating research cen-

cial and behavioral deficits, motivation to change, and re- ters and further processed the serious adverse events reports

establishment of alternative behaviors. 16 A preliminary as requested by ethics committees. An independent data moni-

meta-analysis17 including 16 intervention studies found large toring and safety board was established. Written informed con-

effect sizes of CBT on IA symptoms (g = 1.48; 95% CI, 0.84- sent was required. Participants were offered vouchers for trav-

2.13). Individual vs group, female, older, and North American eling costs but did not receive financial incentives.

participants indicated better treatment responses. As in a more To evaluate STICA’s efficacy, we recruited patients from

recent review on CBT,18 the authors questioned the validity of 2012 to 2016, in specialized outpatient clinics at 4 university

these studies owing to methodologic shortcomings, lack of ran- medical centers in Mainz, Tübingen, and Mannheim, Ger-

domization and adequate controls, inconsistencies of assess- many, and Vienna, Austria. The population was limited to men,

ment, insufficient information on recruitment and samples, who represent 90% of the patients treated or diagnosed in out-

and lack of manualized treatments.18 patient clinics for behavioral addictions. Randomized pa-

To overcome these shortcomings, we conducted a multi- tients fulfilled diagnostic criteria of IA and were allocated to

center randomized clinical trial based on short-term treat- the STICA or a wait-list control (WLC) group. Remission of IA

E2 JAMA Psychiatry Published online July 10, 2019 (Reprinted) jamapsychiatry.com

© 2019 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ by a Idaho State University User on 07/17/2019

Efficacy of Short-term Treatment of Internet and Computer Game Addiction Original Investigation Research

based on predefined criteria was our main end point at termi-

Figure 1. CONSORT Diagram

nation of the intervention. Secondary end points included level

of psychosocial functioning, depressive symptoms, and pre-

187 Patients assessed for eligibility

occupation with online activities.

38 Excluded (multiple

Study Participants exclusions possible)

22 AICA-S

Participants were mostly referred by general practitioners, psy- 10 Comorbid depression

chotherapists, and psychiatrists; fewer were self-referred via 6 IA as primary diagnosis

5 AICA-C

the webpage or media coverage of the trial in local newspa-

4 Ongoing psychotherapy

pers. Men aged 17 to 55 years meeting criteria for IA in the past 3 GAF score <40 points

6 months according to clinical expert ratings (AICA-C) and the 3 Treatment with psychotropic

drugs within past 4 wk and

AICA-S self-report measure were eligible for participation change of dose within

past 8 wk

(eTable 1 in Supplement 2). Additional information on inclu- 1 Severe comorbid disorders

sion can be found in the eMethods in Supplement 2.

149 Randomized

Randomization

Randomization was carried out separately for each site ac-

cording to computer-generated randomization lists by the In- 74 Allocated to intervention 75 Allocated to wait-list control group

72 Received allocated intervention 71 Attended WLC

terdisciplinary Center for Clinical Trials Mainz, the indepen- 2 Withdrawal from study 4 Withdrawal from study

dent randomization unit. Considering a possible group size of

up to 8 patients, up to 16 patients were to be randomized (ra- 12 Lost to t1

62 Lost to t1

tio 1:1) at the same time. After confirmation that a patient ful- 12 Lost to t2

53 Lost to t2

12 Lost to t3

filled all inclusion criteria, the electronic clinical report form

immediately provided the investigator with the randomiza- 72 Analyzed 71 Analyzed

tion results. Patients were subsequently informed about their 11 Primary outcome AICA-S 8 Primary outcome AICA-S

LOCF t1 → t2 LOCF t1 → t2

inclusion and the intervention started shortly after. Observer-

rated outcome measures were assessed by clinicians who were

AICA-C indicates Assessment of Internet and Computer Game Addiction

blinded to the study condition.

self-report; AICA-S, Assessment of Internet and Computer Game Addiction

clinical expert rating; GAF, Global Assessment of Functioning; LOCF, last

Treatment observation carried forward; t1, time factor, midtreatment; t2, time factor,

Short-term treatment for internet and computer game addic- termination; t3, time factor, 6-month follow-up; and WLC, wait-list control.

tion is a 15-week, CBT-based, manualized treatment for IA19,20

The method is based on the integrated process model of in- group only).24 Midterm assessment was carried out to com-

ternet addiction (InPRIA-model23), which conceptualizes IA as pensate for missing data.

resulting from a dynamic interaction of individual factors, fea- The tool used in assessment of the primary outcome was

tures of the online activity, dysfunctional coping strategies, and the AICA-S. This self-report measure assesses the main DSM-5

disorder-specific cognitive biases. eTable 2 in Supplement 2 criteria for internet gaming disorder by 14 items, including the

gives an overview of the treatment phases with 15 group ses- frequency of 8 internet activities (eg, gaming, pornography, so-

sions (100 minutes). Eight individual sessions (60 minutes) are cial media). Scores of 13 or greater (possible range: 0-6.5 [non-

interspersed in the program to promote treatment motiva- pathologic behavior], 7.0-13.0 [moderate, ie, abusive, addic-

tion and provide crisis intervention. tive behavior], >13.0 [addictive behavior]) indicate IA. Cutoff

scores were derived from the general population and clini-

Therapists cally validated12 with good diagnostic accuracy (sensitivity,

Seven (4 women) cognitive-behavioral therapists conducted 80.5%; specificity, 82.4%).

CBT. All therapists held degrees as clinical psychologists or phy- The AICA using expert evaluators (AICA-C24) reliably (Cron-

sicians and had completed their psychotherapeutic training or bach α = 0.9) was used to measure secondary outcomes. The

were undergoing advanced CBT training. Therapists were spe- AICA-C defines 6 core criteria for IA (preoccupation, loss of con-

cifically trained in the treatment manual by the authors (K.W., trol, withdrawal, negative consequences, tolerance, craving) to

K.W.M., M.D., M.E.B.). To maintain treatment fidelity during be rated by a trained clinician on a 6-point scale (0, criterion not

the trial, therapists videotaped sessions and received regular met; 5, criterion fully met). A cutoff score of 13 has yielded the

supervision. These supervisory interactions were conducted best values on diagnostic accuracy (sensitivity, 85.1%; specific-

in a ratio of 1 in 4 group sessions. ity, 87.5%).25 The AICA-S and AICA-C instruments were ad-

opted to assess different subtypes of internet addiction, which

Assessment and Blinding represents a broader concept of the disorder.

As depicted in Figure 1 (CONSORT diagram), the 4 measure- Other instruments used to evaluate the secondary out-

ment points included baseline (pretreatment; t0), midtreat- comes included the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF),

ment (2 months after treatment start; t1), posttreatment after which measures psychosocial functioning on a scale from 0

approximately 4 months (t2), and 6-month follow-up (t3, STICA (insufficient information) to 100 (superior functioning).26 The

jamapsychiatry.com (Reprinted) JAMA Psychiatry Published online July 10, 2019 E3

© 2019 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ by a Idaho State University User on 07/17/2019

Research Original Investigation Efficacy of Short-term Treatment of Internet and Computer Game Addiction

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-I and -II) was ing data were not replaced using multiple imputations, because

administered at t0, t2, and t3 for assessing comorbid mental sensitivity analyses yielded unsatisfactory results. Findings

disorders. The Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II27) as- were considered significant at P < .05. The statistical soft-

sesses depressive symptoms by 21 items on 4-point Likert ware used for analysis was SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Inc)

scales, with possible scores indicating depression of 0 to 13 and SPSS, version 23 (IBM).

(minimal), 14 to 19 (mild), 20 to 28 (moderate), and 29 to 63

(severe); in this trial, comorbid depression was indicated by a

BDI-II score of 26 or higher.

In these additional assessments, only AICA-S, AICA-C,

Results

BDI-II, and GAF were administered. At t0, t1, t2, and t3, the Participants

primary and secondary end points were determined; SCID-I As shown in Figure 1, of 187 patients assessed, 38 did not meet

and SCID-II were administered at t0, t2, and t3. All evalua- inclusion criteria. Thus, 149 patients were randomized (inten-

tions were performed by independent raters blinded to the tion-to-treat). From the intention-to-treat population, 6 pa-

treatment condition (trained psychologists). No study alloca- tients withdrew from participation, resulting in 72 patients in

tion information was revealed to raters. the STICA group and 71 patients in the WLC group. At midtreat-

ment assessment, in STICA, 12 participants dropped out (9 in

Primary and Secondary End Points WLC), and 12 (9 in WLC) dropped out at termination. The pa-

The primary end point was remission of IA based on a cutoff tient distribution to the cohorts was center 1, 126 (100 in-

AICA-S score of less than 7 points.21 Secondary outcomes were cluded; STICA: 50; WLC: 50), center 2, 22 (19 included; STICA:

self-reported internet addiction symptoms, time spent on- 9; WLC: 10), center 3, 16 (9 included; STICA: 4; WLC: 5), and

line on weekdays, psychosocial functioning, and depression. center 4, 23 (21 included; STICA: 11; WLC: 10).

Demographic and medical data did not differ signifi-

Safety and Adverse Events cantly between STICA and WLC participants at baseline

Adverse events were defined as any significant unfavorable (eTable 1 in Supplement 2). Mean (SD) age was 26.2 (7.8) years

change in the patient’s pretreatment mental condition, regard- (range, 17-52 years). Most participants had an advanced edu-

less of its relationship to treatment, particularly the occur- cation (86). Almost half were in training or school, 1 in 3 was

rence of any additional mental disorder. Adverse events and employed, and the rate of unemployment was high (27

serious adverse events were reported to the data safety and [18.9%]). Twelve men (8.4%) were married. The main prob-

monitoring board. Details are available in the eResults of lem applications were online computer games (82 [56.6%]),

Supplement 2. online pornography (23 [16.1%]), generalized IA (29 [20.9%]),

and offline computer games (9 [6.3%]). A correlation analysis

Statistical Analysis revealed IA subtype and age effects as follows: online games:

Sample size calculation was based on the previous open trial with STICA, r = −0.425 (P = .001) and WLC, r = −0.283 (P = .01); of-

33 patients.21 Twenty-four patients had achieved remission ac- fline games: STICA, r = 0.113 (P>.05) and WLC: r = −0.179

cording to the AICA-S cutoff score of less than 7; the dropout rate (P>.05); online pornography: STICA, r = 0.347 (P = .002) and

was 29.7%. A difference in the WLC group of 20% was consid- WLC: r = 0.331 (P = .004); and other: STICA: r = 0.152 (P>.05)

ered clinically relevant. With a power of 90%, 184 patients are and WLC: r = 0.140 (P>.05). A total of 52.4% of the patients met

needed to detect that difference; 192 patients were planned for criteria for at least 1 further mental disorder (mostly mild to

inclusion. To estimate the feasibility of recruitment, treatment moderate depression) according to SCID-I/SCID-II (eTable 3 in

seekers were surveyed over 1 month in all participating centers Supplement 2). Twenty-one patients (14.7%) were receiving

before the main study. The primary end point was remission of stable regimens of psychotropic medication.

IA at treatment completion measured by an AICA-S score of less A total of 100 patients (69.9%) (STICA: 47 [65.3%]; WLC:

than 7 points. Internet addiction was analyzed by a generalized 53 [74.6%]; χ 21 = 7.15; P = .01) finished treatment as sched-

linear mixed-effects model (within and between cluster variance) uled. The most frequent reasons for being classified as a drop-

with treatment status, pretreatment AICA-S score, comorbid out were lack of adherence and having missed a predefined

mental disorders, study center, and age. number of therapy sessions (attended <18 of 23 sessions)

Secondary end points were analyzed as between-participant (STICA: 20 [27.8%]; WLC: 14 [19.7%]).24

(STICA vs WLC) and within-participant comparisons over time.

Baseline-adjusted analyses of covariance, repeated-measure Analysis of Primary End Point

analyses of covariance, 1-tailed paired and unpaired t tests, and Based on AICA-S at posttreatment, 50 of patients (69.4%) re-

χ2 tests were used. Cohen d (dz values adjusted for the intercor- ceiving STICA were classified as achieving remission com-

relations of the dependent variables) were used as effect size in- pared with 17 patients (23.9%) in the WLC group (χ 21 = 29.72;

dicators. Expert rating of IA symptoms (AICA-C<13 points) indi- P < .001; φ = 0.456). Generalized linear mixed-effects model

cating remission were analyzed as a secondary end point. with treatment status, pretreatment AICA-S score, comorbid

Analysis was based on the intention-to-treat population. disorders, center, and age as factors was performed to exam-

Missing data at t2 were replaced by t1 data if available (last ob- ine the primary (Table 1). The adjusted odds ratio for STICA vs

servation carried forward). If t1 data were not available, drop- WLC was 10.10 (95% CI, 0.69-27.65; P < .001). A higher AICA-S

ping out of the study was regarded as treatment failure. Miss- baseline score was associated with less remission.

E4 JAMA Psychiatry Published online July 10, 2019 (Reprinted) jamapsychiatry.com

© 2019 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ by a Idaho State University User on 07/17/2019

Efficacy of Short-term Treatment of Internet and Computer Game Addiction Original Investigation Research

Table 1. Primary End Point in 143 Patients: Generalized Linear Mixed Figure 2. Changes of the Mean Subjective Assessment of Internet and

Model Within and Between Cluster Variancea Computer Game Addiction (AICA-S) Scores Across Measurement Points

Variable Odds Ratio (95% CI) P Value

Short-term treatment of internet

Treatment and computer game addiction

25

STICA vs WLC 10.10 (3.69-27.65) <.001 Wait-list control

AICA-S baseline score 0.84 (0.74-0.94) .003

20

Comorbidity at baselineb

No vs yes 0.96 (0.61-1.5) .61

15

Treatment center 1.01 (0.96-1.10) .87

AICA-S Score

Age, y 0.80 (0.35-1.86) .66

10

Abbreviations: AICA-S, subjective Assessment of Internet and Computer Game

Addiction; STICA, short-term treatment for internet and computer game

addiction; WLC, wait-list control.

5

a

Modeled for the remission rate of the AICA-S. Patients terminating the study

prematurely were modeled based on t1 (time factor, midtreatment) results

(last observation carried forward). 0

b

Determined according to the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-4

Baseline (t0) Mid Treatment (t1) Posttreatment (t2) Follow-up (t3)

(dichotomous categorization).

Comparison of short-term treatment for internet and computer game addiction

group with wait-list control group. The horizontal line in the middle of each box

There were no significant differences of baseline vari-

indicates the median. The diamond within each box indicates the mean. Top

ables between the centers. In addition, the center had no ef- and bottom borders of the box mark the 75th and 25th percentiles,

fect on the primary or secondary outcomes. respectively. The whiskers above and below the box mark the 90th and 10th

Figure 2 shows the numeric AsignificantICA-S scores for percentiles. The circles beyond the whiskers are outliers. t0 indicates time

factor, baseline; t1, time factor, midtreatment; t2, time factor, termination; and

STICA and WLC (modeled according to last observation car- t3, time factor, 6-month follow-up.

ried forward). The greatest declines were observed at midtreat-

ment, and these were consolidated at posttreatment for STICA

with small improvements in the WLC group. Thirty-six par- age, 26 years; range, 17-52 years) with addictive online and

ticipants (50.0%) in the STICA group were contacted 6 months offline gaming or IA. These behaviors address domains

after treatment termination. Of these, 29 respondents (80.6%) beyond the Gaming Disorder Category, which will also be

scored below the cutoff level for IA. provided by upcoming International Classification of Dis-

eases, 11th Revision; nonetheless, these share the under-

Analyses of Secondary End Points standing of behavioral disorders.3 A total of 52.4% of the

Analysis of variance revealed significant main effects for STICA patients had comorbid mental disorders (mostly mild to

(F2,90 = 128.64; P ≤ .001) and WLC (F2,118 = 14.78; P ≤ .001) and moderate depression), and 14.7% were receiving stable regi-

interactions between time (t0, t1, t2) and treatment (STICA, mens of psychotropic medication.

WLC; F2,202 = 33.95; P ≤ .001) for self-reported and expert- Monitored by the Interdisciplinary Center for Clinical Trials,

reported IA scores and time spent online on weekends (Table 2). we randomized 143 patients to STICA or WLC. The primary end

Significant main and interaction effects were also found for point was remission according to AICA-S.12,21 Even though the

STICA regarding online times on weekdays (F2,111 = 151.28; sensitivity and specificity of the AICA-S12 and AICA-C25 are suf-

P ≤ .001) and GAF scores (F2,110 = 17.19; P ≤ .001). Significant ficient, the AICA-C25 has a small advantage in detecting inter-

main effects emerged for depression (STICA: F2,104 = 37.46; net gaming disorder. Nonetheless, AICA-S21 was predefined as

P ≤ .001; and WLC: F2,118 = 10.80; P ≤ .001). the primary outcome of this study.24 Based on intention-to-

eTable 4 in Supplement 2 displays post hoc within-group treat analyses, at termination, 69.4% of the STICA group

tests, effect sizes, and between-group effect sizes. Effect size achieved remission vs 23.9% of the WLC. The odds ratio for

differences between t0 and t2 were in favor of STICA regard- remission was 10.10 in favor of STICA.

ing AICA-S (1.63), AICA-C (1.37), time spent online on week- The STICA group showed strong pre-post effect size dif-

days (1.13), time spent online on weekends 0.96, GAF score ferences at treatment termination compared with the WLC

(0.61), and depression (0.38). group on self-reported IA symptoms (d = 1.19), time spent on-

line (d = 0.88), and psychosocial functioning (d = 0.64). Pre-

post effect sizes for depression were high in STICA (d = 0.90);

however, as depression also was reduced in WLC, differences

Discussion between STICA and WLC were not significant.

To our knowledge, the data reported herein represent the Self-report data were confirmed using external ratings by

first randomized clinical observer blind multicenter trial on trained professionals blinded to the treatment condition.

IA.16 Based on a theoretical model of IA, the published and Analyses of AICA-C, a validated checklist,25 confirmed a sig-

successfully pretested short-term CBT (STICA19,20) was per- nificant decrease of IA symptoms in the STICA compared with

formed at 4 different sites We included a male sample (mean the WLC group with a large effect size (d = 0.80).

jamapsychiatry.com (Reprinted) JAMA Psychiatry Published online July 10, 2019 E5

© 2019 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ by a Idaho State University User on 07/17/2019

Research Original Investigation Efficacy of Short-term Treatment of Internet and Computer Game Addiction

Table 2. Changes of Symptoms Over Time in STICA (n = 72) vs WLC (n = 71) Participantsa

Measurement Point, Mean (SD) Main Interaction Effect

End Point t0 t1 t2 F Valueb P Value

AICA-S Abbreviations: AICA-C, Assessment

STICA 13.1 (3.83) 5.7 (3.99) 4.6 (3.46) F2,90 = 128.64 ≤.001 of Internet and Computer game

Addiction Checklist;

WLC 12.7 (4.14) 11.4 (4.70) 1.5 (4.33) F2,118 = 14.78 ≤.001

AICA-S, subjective Assessment

Interaction (time × treatment) F2,202 = 33.95 ≤.001 of Internet and Computer Game

AICA-Cc Addiction scale; BDI-II, Beck

Depression Inventory II; value

STICA 18.6 (4.9) 8.3 (5.5) 6.3 (6.3) F2,111 = 151.28 ≤.001

(analysis of variance); GAF, Global

WLC 18.6 (5.8) 15.9 (7.4) 13.6 (8.1) F2,103 = 11.92 ≤.001 Assessment of Functioning;

Interaction (time × treatment) F2,231 = 19.88 ≤.001 STICA, Short-term Treatment for

Internet and Computer Game

Time Spent Online (weekday), h/d

Addiction (treatment group);

STICA 6.5 (3.11) 3.4 (3.03) 3.0 (2.21) F2,11 = 46.66 ≤.001 WLC, wait-list control.

a

WLC 5.8 (3.14) 5.8 (3.29) 5.7 (3.09) F2,51 = 0.61 .67 Total of 143 participants evaluated

Interaction (time × treatment) F2,228 = 15.74 ≤.001 in last observation carried forward;

analysis of variance with factors

Time Spent Online (weekend), h/d time (t0, t1, t2) and treatment

STICA 8.4 (3.91) 4.1 (2.82) 3.6 (2.57) F1.7,96.7 = 59.25 ≤.001 (STICA, WLC); t0, baseline;

WLC 7.6 (3.73) 5.6 (3.43) 5.1 (3.17) F2,118 = 7.51 .001 t1, midtreatment; t2 termination.

b

Interaction (time × treatment) F2,230 = 2.89 ≤.001 Determined with analysis of

variance.

d

GAF c

Possible score range: 0 to 6.5

STICA 69.3 (1.00) 75.7 (8.93) 76.4 (1.40) F2,110 = 17.19 ≤.001 (nonpathologic behavior), 7.0 to

WLC 69.5 (9.52) 7.6 (9.25) 69.5 (9.73) F2,118 = 0.89 .412 13.0 (moderate, ie, abusive,

addictive behavior), and greater

Interaction (time × treatment) F2,228 = 9.26 ≤.001

than 13.0 (addictive behavior)

BDI-II indicating IA.

STICA 13.9 (9.54) 8.1 (8.35) 5.8 (7.24) F2,104 = 37.46 ≤.001 d

Measures psychosocial functioning

WLC 15.4 (8.73) 15.0 (9.64) 12.3 (8.97) F2,118 = 10.80 ≤.001 on a scale from 0 (insufficient

information) to 100 (superior

Interaction (time × treatment) F2,230 = 2.61 .08

functioning).

To compare findings with the meta-analysis,17 we also com- cal experience that, in some cases, reduction of the addictive

puted pre-post treatment effect sizes for completers (n = 100). online behavior may also destabilize emotional self-

These exceeded the previously reported effects (g = 1.48). In regulation. Given the often pervasive and chronic maladjust-

favor of STICA, we found pre-post effect sizes of d = 2.57 for ment (eg, high unemployment in this well-educated group),

AICA-S, d = 1.05 for time spent online on a weekday, d = 1.47 deficient self-regulation, social insecurity, and anxiety,12,28,29

response at weekends, and d = 1.10 for BDI-II. Completers and we supplemented group with individual treatment sessions to

noncompleters did not differ significantly in baseline vari- monitor depressive and other psychopathological symptoms

ables except for time spent online on a weekday. and provide crisis intervention.24

Despite the heterogeneity of the treatment group, we found When the trial started, there was no alternative treat-

that our CBT program was effective across this range, regard- ment available; thus, we used a WLC, giving participants the

less of age, comorbidity, or treatment center. These findings option to obtain treatment with a delay of 15 weeks. Partici-

support a unitary concept of IA and point to the flexibility of pation in the WLC had small to moderate effects regarding IA,

the STICA.19,20 Patients seeking treatment for different sub- time spent online, general functioning, and depression. These

types of IA represent the study population. Consideration of effects underscore the necessity to include a control group, and

IA as a broad dysfunction has been controversial.4,5 In this we surmise that previous pre-post analyses have overesti-

study, treatment efficacy within all subtypes of IA supports a mated treatment effects.17 Although we cannot preclude spon-

broader concept of IA. taneous remission, we would argue that inclusion in the trial

We found many of the patients to be ambivalent toward with repeated assessment contacts and the prospect of fu-

engaging in and completing treatment. This resistance indi- ture treatment probably provided structure, motivation, and

cates a core characteristic of IA-affected patients. Given their hope for change, which may have accounted for improve-

low level of conscientiousness and the high level of negative ments in the WLC.

affectivity,28 we found it necessary to promote treatment mo-

tivation. The group intervention appeared to be helpful to en- Limitations

gage patients emotionally, with an opportunity to reflect on Several limitations should be addressed. Pre-post compari-

cognitive distortions and obtain support from group mem- sons may have overestimated the effect of this intervention.

bers. We found that several patients became depressed over The pace of recruitment was slower than expected, as we could

the course of the trial, and a few needed to be transferred to randomize only when a sizable number of patients was re-

inpatient psychotherapy. This finding concurs with our clini- cruited. Some patients dropped out before randomization.

E6 JAMA Psychiatry Published online July 10, 2019 (Reprinted) jamapsychiatry.com

© 2019 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ by a Idaho State University User on 07/17/2019

Efficacy of Short-term Treatment of Internet and Computer Game Addiction Original Investigation Research

Thus, we were not able to reach the planned number of par- stability of the findings need further testing. Thus, follow-up

ticipants. We therefore needed an extended recruitment time assessment 6 months after the end of treatment cannot be in-

with smaller group sizes. However, the statistical power was terpreted. Future studies should put a clear emphasis on col-

sufficient to detect differences in the end points accurately. lecting follow-up data and implement efficient strategies to en-

In this randomized clinical trial, we used self-report sure higher response rates. There is a necessity to put further

as a primary end point. While AICA-S is a validated self- efforts in strengthening the patientś commitment, by, for ex-

assessment for IA, an externally assessed (clinical) rating ample, elaborating on strategies for enhancing the motivation

might confer higher clinical validity as a primary end point. to change before the start of treatment. The WLC group re-

Because participants were limited to men to reflect the pre- ceived no follow-up measure, since the start of treatment would

ponderance of male treatment seekers, results cannot be gen- have been prolonged for 10 months from randomization, which

eralized to female patients. While recent epidemiologic sur- was considered unacceptable for ethical reasons. We decided

veys have shown almost no sex differences regarding the to include a WLC owing to the lack of empirically evaluated

prevalence of IA,30 female patients with IA are seldom repre- alternative treatment programs (ie, treatment as usual) for IA

sented in the help system. Therefore, further clinical trials are at that time. However, a WLC contains limitations (eg, the risk

needed to evaluate the effectiveness of STICA in females. of inflating estimations on therapy effects).

Research has demonstrated that IA is associated with high

rates of comorbidity.14 Although we controlled for the effects

of comorbidity, we had to define exclusion criteria for some

of these conditions (eg, major depression, some personality dis-

Conclusions

orders). Thus, the clinical sample is probably not fully repre- Future trials should consider the effects of accompanying medi-

sentative of the entire population of patients with IA. cation on IA. There are some data on the effects of pharma-

Consistent with a systematic review by Brorson and cotherapy in IA.17 Combining CBT and pharmacotherapy could

colleagues31 on dropout rates of young adults in addiction treat- lead to augmented effects. The study shows that STICA can be

ment (23%-50%), dropout rates were considerable in our sample. effective in treatment of IA. Thus, STICA might be used as a

In case of missing t3 data, we did not use t2 data via last obser- benchmark as a nonpharmacologic intervention and serve as

vation carried forward. Owing to high dropout rates at t3, the a treatment as usual condition in upcoming trials.

ARTICLE INFORMATION Critical revision of the manuscript for important addiction. World Psychiatry. 2016;15(3):297-298.

Accepted for Publication: April 25, 2019. intellectual content: All authors. doi:10.1002/wps.20373

Statistical analysis: Woelfling, Ruckes. 3. World Health Organization. WHO releases new

Published Online: July 10, 2019. Obtained funding: Mueller, Beutel.

doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.1676 International Classification of Diseases (ICD 11).

Administrative, technical, or material support: http://www.who.int/news-room/detail/18-06-

Author Affiliations: Outpatient Clinic for Mueller, Deuster, Batra, Mann, Musalek, Schuster, 2018-who-releases-new-international-

Behavioral Addictions, Department of Lemenager, Hanke, Beutel. classification-of-diseases-(icd-11). Published June

Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy, Supervision: Woelfling, Mueller, Mann, Musalek, 18, 2018. Accessed June 18, 2018.

University Medical Center of the Johannes Schuster, Beutel.

Gutenberg-University Mainz, Mainz, Germany Other - study coordination: Dreier. 4. Starcevic V, Billieux J. Does the construct of

(Wölfling, Müller, Dreier); Interdisciplinary Center Internet addiction reflect a single entity or a

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported. spectrum of disorders? Clinical Neuropsychiatry.

for Clinical Trials Mainz, University Medical Center

of the Johannes Gutenberg-University Mainz, Funding/Support: The study was supported by 2017;14(1):5-10. http://www.clinicalneuropsychiatry.

Mainz, Germany (Ruckes, Deuster); University German Research Foundation grant BE2248/0-1. org/pdf/02Starcevic.pdf. Accessed June 18, 2018.

Hospital of Tübingen, Department of Psychiatry Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The University 5. Brand M, Young KS, Laier C, Wölfling K, Potenza

and Psychotherapy, Section for Addiction Research Medical Center of the Johannes MN. Integrating psychological and neurobiological

and Medicine, Tübingen, Germany (Batra, Hanke); Gutenberg-University Mainz, Mainz, Germany, was considerations regarding the development and

Medical Faculty Mannheim, Department of responsible for design and conduct of the study; maintenance of specific internet-use disorders:

Addictive Behaviour and Addiction Medicine, collection, management, analysis, and an Interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-

Central Institute of Mental Health, Heidelberg interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or Execution (I-PACE) model. Neurosci Biobehav Rev.

University, Mannheim, Germany (Mann, approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit 2016;71:252-266. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.

Lemenager); Department of Psychiatry, Anton the manuscript for publication. The German 08.033

Proksch Institute, Vienna, Austria (Musalek, Research Foundation was not involved in any of the 6. Griffiths MD, van Rooij AJ, Kardefelt-Winther D,

Schuster); Department of Psychosomatic Medicine following points: design and conduct of the study; et al. Working towards an international consensus

and Psychotherapy, University Medical Center of collection, management, analysis, and on criteria for assessing internet gaming disorder:

the Johannes Gutenberg-University Mainz, Mainz, interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or a critical commentary on Petry et al. (2014).

Germany (Beutel). approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit Addiction. 2016;111(1):167-175. doi:10.1111/add.13057

Author Contributions: Drs Wölfling and Müller the manuscript for publication.

7. Petry NM, Rehbein F, Gentile DA, et al.

contributed equally as co–first authors. Drs Wölfling Data Sharing Statement: See Supplement 3. An international consensus for assessing internet

and Beutel had full access to all the data in the gaming disorder using the new DSM-5 approach.

study and take responsibility for the integrity of REFERENCES Addiction. 2014;109(9):1399-1406. doi:10.1111/add.

the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. 1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and 12457

Concept and design: Woelfling, Mueller, Ruckes, Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5).

Mann, Musalek, Beutel. 8. Fauth-Bühler M, Mann K. Neurobiological

Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; correlates of internet gaming disorder: similarities

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All 2013.

authors. to pathological gambling. Addict Behav. 2017;64:

Drafting of the manuscript: Woelfling, Mueller, 2. Mann K, Fauth-Bühler M, Higuchi S, Potenza MN, 349-356. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.11.004

Dreier, Batra, Musalek, Beutel. Saunders JB. Pathological gambling: a behavioral

jamapsychiatry.com (Reprinted) JAMA Psychiatry Published online July 10, 2019 E7

© 2019 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ by a Idaho State University User on 07/17/2019

Research Original Investigation Efficacy of Short-term Treatment of Internet and Computer Game Addiction

9. Kühn S, Gallinat J. Brain structure and functional 17. Winkler A, Dörsing B, Rief W, Shen Y, 25. Wölfling K, Beutel ME, Müller KW. Construction

connectivity associated with pornography Glombiewski JA. Treatment of internet addiction: of a standardized clinical interview to assess

consumption: the brain on porn. JAMA Psychiatry. a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33(2):317-329. internet addiction: first findings regarding the

2014;71(7):827-834. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2012.12.005 usefulness of AICA-C. J Addict Res Ther. 2012;6.

2014.93 18. King DL, Delfabbro PH, Wu AMS, et al. doi:10.4172/2155-6105.S6-003

10. Ko CH, Liu GC, Yen JY, Chen CY, Yen CF, Treatment of internet gaming disorder: an 26. Söderberg P, Tungström S, Armelius BA.

Chen CS. Brain correlates of craving for online international systematic review and CONSORT Reliability of global assessment of functioning

gaming under cue exposure in subjects with evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev. 2017;54:123-133. ratings made by clinical psychiatric staff. Psychiatr

internet gaming addiction and in remitted subjects. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2017.04.002 Serv. 2005;56(4):434-438. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.56.

Addict Biol. 2013;18(3):559-569. doi:10.1111/j.1369- 19. Wölfling K, Jo C, Bengesser I, et al. Video Game 4.434

1600.2011.00405.x and Internet Addiction—A Cognitive Behavioral 27. Beck AT, Steer RA, Braun GK. Beck Depression

11. Zhang JT, Brand M. Neural mechanisms Therapy Concept. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer; 2013. Inventory-II (BDI-II): Manual for Beck Depression

underlying internet gaming disorder. Front Psychiatry. 20. Wölfling K, Müller KW, Dreier M, et al. Internet Inventory-II. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation;

2018;9:404. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00404 addiction and internet gaming Disorder: a Cognitive 1996.

12. Müller KW, Beutel ME, Wölfling K. behavioral psychotherapeutic approach. In: Faust 28. Müller KW, Dreier M, Duven E, Giralt S,

A contribution to the clinical characterization of D, Faust K, Potenza MN, Eds. The Oxford Handbook Beutel ME, Wölfling K. Adding clinical validity to

internet addiction in a sample of treatment seekers: of Digital Technologies and Mental Health. Oxford: the statistical power of large-scale epidemiological

validity of assessment, severity of psychopathology Oxford University; 2015. surveys on internet addiction in adolescence:

and type of co-morbidity. Compr Psychiatry. 2014; 21. Wölfling K, Beutel ME, Müller KW. OSV-S—Skala a combined approach to investigate

55(4):770-777. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.01.010 zum Onlinesuchtverhalten. In: Geue K, Strauß B, psychopathology and development-specific

13. Cheng C, Li AYL. Internet addiction prevalence Brähler E, eds. Diagnostische Verfahren in der personality traits associated with internet

and quality of (real) life: a meta-analysis of 31 Psychotherapie (Diagnostik für Klinik und Praxis). addiction. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78(3):e244-e251.

nations across seven world regions. Cyberpsychol Göttingen: Hogrefe; 2016. doi:10.4088/JCP.15m10447

Behav Soc Netw. 2014;17(12):755-760. doi:10.1089/ 22. Wölfling K, Beutel ME, Dreier M, Müller KW. 29. Leménager T, Hoffmann S, Dieter J, Reinhard I,

cyber.2014.0317 Treatment outcomes in patients with internet Mann K, Kiefer F. The links between healthy,

14. Ko CH, Yen JY, Yen CF, Chen CS, Chen CC. addiction: a clinical pilot study on the effects of a problematic, and addicted internet use regarding

The association between internet addiction and cognitive-behavioral therapy program. Biomed Res comorbidities and self-concept-related

psychiatric disorder: a review of the literature. Int. 2014;2014:425924. doi:10.1155/2014/425924 characteristics. J Behav Addict. 2018;7(1):31-43.

Eur Psychiatry. 2012;27(1):1-8. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy. doi:10.1556/2006.7.2018.13

23. Müller KW, Dreier M, Wölfling K. Excessive

2010.04.011 and addictive use of the internet—prevalence, 30. Rumpf HJ, Vermulst AA, Bischof A, et al.

15. Floros G, Siomos K, Stogiannidou A, related contents, predictors, and psychological Occurrence of internet addiction in a general

Giouzepas I, Garyfallos G. Comorbidity of consequences. In: Reinecke L, Oliver MB, eds. The population sample: a latent class analysis. Eur

psychiatric disorders with internet addiction in Routledge Handbook of Media Use and Well-Being. Addict Res. 2014;20(4):159-166. doi:10.1159/

a clinical sample: the effect of personality, defense New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group; 2016: 000354321

style and psychopathology. Addict Behav. 2014; 223-236. 31. Brorson HH, Ajo Arnevik E, Rand-Hendriksen K,

39(12):1839-1845. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.07.031 24. Jäger S, Müller KW, Ruckes C, et al. Effects of Duckert F. Drop-out from addiction treatment:

16. King DL, Delfabbro PH, Griffiths MD, a manualized short-term treatment of internet and a systematic review of risk factors. Clin Psychol Rev.

Gradisar M. Cognitive-behavioral approaches to computer game addiction (STICA): study protocol 2013;33(8):1010-1024. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2013.07.007

outpatient treatment of internet addiction in for a prospective randomised controlled

children and adolescents. J Clin Psychol. 2012;68 multicentre trial. Trials. 2012;13:43. doi:10.1186/

(11):1185-1195. doi:10.1002/jclp.21918 1745-6215-13-43

E8 JAMA Psychiatry Published online July 10, 2019 (Reprinted) jamapsychiatry.com

© 2019 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ by a Idaho State University User on 07/17/2019

You might also like

- Yasenik and Gardner - Play Therapy Dimensions Model - Chapter 1Document24 pagesYasenik and Gardner - Play Therapy Dimensions Model - Chapter 1artemidi100% (2)

- Efficacy of An Internet-Based Psychological Intervention For Problem GamblingDocument14 pagesEfficacy of An Internet-Based Psychological Intervention For Problem GamblingSlenNo ratings yet

- 2006 Article p159Document9 pages2006 Article p159breiyaprouvellau-8047No ratings yet

- A Randomized Controlled Trial On A Self Guided Internet Based Intervention For Gambling ProblemsDocument12 pagesA Randomized Controlled Trial On A Self Guided Internet Based Intervention For Gambling ProblemsZia DrNo ratings yet

- Internet-Versus Group-Administered Cognitive Behaviour Therapy For Panic Disorder in A Psychiatric Setting: A Randomised TrialDocument10 pagesInternet-Versus Group-Administered Cognitive Behaviour Therapy For Panic Disorder in A Psychiatric Setting: A Randomised TrialSophi RetnaningsihNo ratings yet

- Desensitization of Triggers and Urge ReprocessingDocument9 pagesDesensitization of Triggers and Urge ReprocessingImim100% (1)

- 1 - 1 JurnalDocument16 pages1 - 1 JurnalSuppanadNo ratings yet

- Physical Exercise and iCBT in Treatment of DepressionDocument9 pagesPhysical Exercise and iCBT in Treatment of DepressionCarregan AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Internet-Delivered Psychological Treatment Options For Panic Disorder: A Review On Their Efficacy and AcceptabilityDocument13 pagesInternet-Delivered Psychological Treatment Options For Panic Disorder: A Review On Their Efficacy and AcceptabilityluthfiNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2214782921000932 MainDocument11 pages1 s2.0 S2214782921000932 MainCristina TudoranNo ratings yet

- Fpsyt 11 608896Document20 pagesFpsyt 11 608896shumailaNo ratings yet

- Protocolo SticaDocument8 pagesProtocolo SticaMarcelo NevesNo ratings yet

- Kall Et Al 2020Document10 pagesKall Et Al 2020365psychNo ratings yet

- Jamapsychiatry Papola 2023 Oi 230080 1697118575.84256Document11 pagesJamapsychiatry Papola 2023 Oi 230080 1697118575.84256Renan CruzNo ratings yet

- Optimizing Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy For Social Anxiety Disorder and Understanding The Mechanisms of ChangeDocument9 pagesOptimizing Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy For Social Anxiety Disorder and Understanding The Mechanisms of Changedinda septia ningrumNo ratings yet

- Pros and Cons of Online Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy: ArticleDocument3 pagesPros and Cons of Online Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy: ArticleSakti ManNo ratings yet

- Neurological Disorders Report WebsiteDocument11 pagesNeurological Disorders Report WebsiteOslo SaputraNo ratings yet

- Intrinsic Connectomes Are A Predictive Biomarker of Remission in Major Depressive DisorderDocument13 pagesIntrinsic Connectomes Are A Predictive Biomarker of Remission in Major Depressive DisorderYi-Chy ChenNo ratings yet

- Jama Association Between Physical Activity and Risk of DepressionDocument10 pagesJama Association Between Physical Activity and Risk of DepressiongbfascNo ratings yet

- Artigo NFD Efficacy of Invasive and Non-Invasive Brain ModulationDocument23 pagesArtigo NFD Efficacy of Invasive and Non-Invasive Brain ModulationMarcelo MenezesNo ratings yet

- Pi 2018 08 07 2Document8 pagesPi 2018 08 07 2pangaribuansantaNo ratings yet

- 1745 6215 14 437Document7 pages1745 6215 14 437Gustavo Adolfo Pimentel ParraNo ratings yet

- Association Between Physical Activity and Risk of Depression A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocument10 pagesAssociation Between Physical Activity and Risk of Depression A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisAna Margarida J. - PsicólogaNo ratings yet

- Dissociable Neural Substrates of Opioid and Cocaine Use Identi Fied Via Connectome-Based ModellingDocument11 pagesDissociable Neural Substrates of Opioid and Cocaine Use Identi Fied Via Connectome-Based Modellingnisha chauhanNo ratings yet

- Pyv082 Cognitive Effect SsriDocument13 pagesPyv082 Cognitive Effect SsriRifqi Hamdani PasaribuNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument14 pagesUntitledziqian weiNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Intervensi Keperawatan Pasien Insomnia-DikonversiDocument16 pagesJurnal Intervensi Keperawatan Pasien Insomnia-DikonversiDelladestiyaNo ratings yet

- Kay-Lambkin Et Al 2009Document11 pagesKay-Lambkin Et Al 2009Pedro AugustoNo ratings yet

- jiang et al 2023 pharmacological and behavioral interventions for fatigue in parkinson s disease a meta analysis of (科研通 ablesci.com)Document9 pagesjiang et al 2023 pharmacological and behavioral interventions for fatigue in parkinson s disease a meta analysis of (科研通 ablesci.com)Pei-Hao ChenNo ratings yet

- Antipsychotics For Preventing Delirium in Hospitalized AdultsDocument12 pagesAntipsychotics For Preventing Delirium in Hospitalized AdultsLuis CsrNo ratings yet

- 9.the Role of Inflammation in Suicidal BehaviourDocument12 pages9.the Role of Inflammation in Suicidal BehaviourWendy QuintanaNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Videoconference-Delivered Cognitive Behavioral Therapy For Adults With Psychiatric Disorders: Systematic and Meta-Analytic ReviewDocument16 pagesEffectiveness of Videoconference-Delivered Cognitive Behavioral Therapy For Adults With Psychiatric Disorders: Systematic and Meta-Analytic ReviewlaiaNo ratings yet

- Fpsyt 14 1243826Document16 pagesFpsyt 14 1243826Zia DrNo ratings yet

- Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy For Personal Recovery of Patients With Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocument13 pagesCognitive-Behavioural Therapy For Personal Recovery of Patients With Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisLydia AmaliaNo ratings yet

- 13 The Comparative Efficacy of Multiple InterventionsDocument12 pages13 The Comparative Efficacy of Multiple InterventionsAngela BoschNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness and Feasibility of Internet-Based InterventionsDocument14 pagesEffectiveness and Feasibility of Internet-Based InterventionsBeatriz MaximinoNo ratings yet

- Acps 145 132Document24 pagesAcps 145 132ltconyers66No ratings yet

- Jurnal k3 1Document6 pagesJurnal k3 1RICA APRILIANo ratings yet

- Mills & Tamnes, 2014.methods and Considerations For Longitudinal Structural Brain Imaging Analysis Across DevelopmentDocument10 pagesMills & Tamnes, 2014.methods and Considerations For Longitudinal Structural Brain Imaging Analysis Across DevelopmentSu AjaNo ratings yet

- Efficacy and Moderators of Cognitive Therapy Versus Behavioural Activation For Adults With Depression Study Protocol of A Systematic Review and Meta Analysis of Individual Participant DataDocument7 pagesEfficacy and Moderators of Cognitive Therapy Versus Behavioural Activation For Adults With Depression Study Protocol of A Systematic Review and Meta Analysis of Individual Participant DataGiorgiana TodicaNo ratings yet

- Efeitos Dos Alopáticos Na DepressãoDocument11 pagesEfeitos Dos Alopáticos Na DepressãoTatiane PaulinoNo ratings yet

- Depresi Pada DMDocument1 pageDepresi Pada DMnigoNo ratings yet

- Eclinicalmedicine: Research PaperDocument10 pagesEclinicalmedicine: Research PaperEvelynNo ratings yet

- Internet AddictionDocument13 pagesInternet Addictionanon_313498160No ratings yet

- Actissist: Proof-of-Concept Trial of A Theory-Driven Digital Intervention For PsychosisDocument11 pagesActissist: Proof-of-Concept Trial of A Theory-Driven Digital Intervention For PsychosisOlivia NasarreNo ratings yet

- Salmoirago Blotcher Et Al 2021 Exploring Effects of Aerobic Exercise and Mindfulness Training On Cognitive Function inDocument8 pagesSalmoirago Blotcher Et Al 2021 Exploring Effects of Aerobic Exercise and Mindfulness Training On Cognitive Function indianavmjarproNo ratings yet

- Mindfulness SubstanceDocument17 pagesMindfulness SubstanceMauri Passariello LaezzaNo ratings yet

- BJP 42 04 403Document17 pagesBJP 42 04 403Anonymous kvI7zBNNo ratings yet

- Artículo 1Document12 pagesArtículo 1Jessica BarriosNo ratings yet

- HHS Public AccessDocument25 pagesHHS Public AccessRiska Resty WasitaNo ratings yet

- A Promising Debut For Computerized TherapiesDocument3 pagesA Promising Debut For Computerized TherapiesAdrian AraimanNo ratings yet

- Efficacy and Acceptability of Pharmacological Treat-Ments For Depressive Disorders in Primary Care: Systematic Review and Network Meta-AnalysisDocument11 pagesEfficacy and Acceptability of Pharmacological Treat-Ments For Depressive Disorders in Primary Care: Systematic Review and Network Meta-AnalysisPutri YingNo ratings yet

- Technology and Mental Health The Role of A IDocument4 pagesTechnology and Mental Health The Role of A IMichaelaNo ratings yet

- Psychosocial Interventions and Immune System Function A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical TrialsDocument13 pagesPsychosocial Interventions and Immune System Function A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical TrialsKassandra González BNo ratings yet

- Chemotherapy Related Cog. Dysf.Document9 pagesChemotherapy Related Cog. Dysf.Manuel Guerrero GómezNo ratings yet

- Smartphone-Based Therapeutic Exercises For Men AffDocument11 pagesSmartphone-Based Therapeutic Exercises For Men AffdiegoNo ratings yet

- 1 PB PDFDocument10 pages1 PB PDFMontillajsNo ratings yet

- Transcutaneous Electrical Cranial-Auricular AcupoiDocument17 pagesTranscutaneous Electrical Cranial-Auricular AcupoihmsepehrNo ratings yet

- Jurnal DepresiDocument15 pagesJurnal DepresiDesi PratiwiNo ratings yet

- Terapi TDR InsomniaDocument11 pagesTerapi TDR InsomniavanyoktavianiNo ratings yet

- Your Examination for Stress & Trauma Questions You Should Ask Your 32nd Psychiatric Consultation William R. Yee M.D., J.D., Copyright Applied for May 31st, 2022From EverandYour Examination for Stress & Trauma Questions You Should Ask Your 32nd Psychiatric Consultation William R. Yee M.D., J.D., Copyright Applied for May 31st, 2022No ratings yet

- Fisiologi Hati Dan Kandung EmpeduDocument37 pagesFisiologi Hati Dan Kandung EmpeduIlham PrayogoNo ratings yet

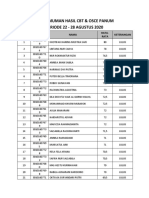

- Pengumuman Hasil PanumDocument8 pagesPengumuman Hasil PanumIlham PrayogoNo ratings yet

- The Research Progress of Acute Small Bowel PerforaDocument5 pagesThe Research Progress of Acute Small Bowel PerforaIlham PrayogoNo ratings yet

- Hasil Seleksi H1 IUP FK Gel 3 2020Document7 pagesHasil Seleksi H1 IUP FK Gel 3 2020Ilham PrayogoNo ratings yet

- FitriDHP - Cardiomegaly Dan Efusion PericardiumDocument40 pagesFitriDHP - Cardiomegaly Dan Efusion PericardiumIlham PrayogoNo ratings yet

- Randomized Between Oral Dinitrate Dosing Development FillingDocument9 pagesRandomized Between Oral Dinitrate Dosing Development FillingIlham PrayogoNo ratings yet

- Dewa Bener NiDocument12 pagesDewa Bener NiIlham PrayogoNo ratings yet

- Master Series Mock Cat 8Document83 pagesMaster Series Mock Cat 8Kunal DasNo ratings yet

- Cognive Behavior Family TherapyDocument16 pagesCognive Behavior Family TherapyAmanda RafkinNo ratings yet

- Neuropsychiatric Aspects of Traumatic Brain Injury.Document34 pagesNeuropsychiatric Aspects of Traumatic Brain Injury.Abhishek Kumar Sharma100% (1)

- Disaster PDFDocument13 pagesDisaster PDFNur AisahNo ratings yet

- Social Isolation and Psychological Distress Among Older Adults Related To COVID-19Document11 pagesSocial Isolation and Psychological Distress Among Older Adults Related To COVID-19Rebe Rodríguez RiosecoNo ratings yet

- AbleTo Psych ServicesDocument1 pageAbleTo Psych ServicesLaluMohan KcNo ratings yet

- Illness Anxiety Disorder, HypochondriasisDocument18 pagesIllness Anxiety Disorder, HypochondriasisSivan AliNo ratings yet

- ! Cognitive Behavioural Therapy Self Help CourseDocument54 pages! Cognitive Behavioural Therapy Self Help CourseKai LossgottNo ratings yet

- Albert Ellis and The Philosophy of RebtDocument13 pagesAlbert Ellis and The Philosophy of RebtJonas C. CardozoNo ratings yet

- Fundamental Research: The Conduct of Agricultural ScienceDocument9 pagesFundamental Research: The Conduct of Agricultural ScienceYemaneDibetaNo ratings yet

- Ecotherapy The Green Agenda For Mental Health Executive Summary PDFDocument6 pagesEcotherapy The Green Agenda For Mental Health Executive Summary PDFMun LcNo ratings yet

- Anxiety in AdolescentsDocument5 pagesAnxiety in Adolescentskahfi HizbullahNo ratings yet

- Generalized Anxiety Disorder: Key SymptomDocument14 pagesGeneralized Anxiety Disorder: Key Symptomジャンロイド ドゥーゴーNo ratings yet

- Abnormal Psychology Notes IB SLDocument41 pagesAbnormal Psychology Notes IB SLHilda Hiong100% (4)

- Existetial Psychotherapy in Cognitive Behavioral ApproachDocument9 pagesExistetial Psychotherapy in Cognitive Behavioral ApproachAnna Mary Joy SumangNo ratings yet

- First Episode Psychosis GuideDocument38 pagesFirst Episode Psychosis Guide'Josh G MwanikiNo ratings yet

- Cognitive PsychologyDocument9 pagesCognitive PsychologyArvella Albay100% (3)

- Cognitive Behavior TherapyDocument5 pagesCognitive Behavior TherapyWonderWomanLadyNo ratings yet

- Treatment of Child Victims of Abuse and NeglectDocument18 pagesTreatment of Child Victims of Abuse and NeglectSri Harsha KothapalliNo ratings yet

- Case Study of A Behavioral Approach To Therapy (Revised)Document13 pagesCase Study of A Behavioral Approach To Therapy (Revised)Bundi IanNo ratings yet

- Directive CounsellingDocument2 pagesDirective CounsellingashvinNo ratings yet

- Universities And/Or Hospitals They Are Affiliated With: Title of The Research StudyDocument1 pageUniversities And/Or Hospitals They Are Affiliated With: Title of The Research StudyADISAINo ratings yet

- A Review of The Transdiagnostic Road Map To Case Formulation and Treatment Planning: Practical Guidance For Clinical Decision MakingDocument2 pagesA Review of The Transdiagnostic Road Map To Case Formulation and Treatment Planning: Practical Guidance For Clinical Decision MakingKAROL GUISELL PATIÑO ATEHORTUANo ratings yet

- Eating Disorders and Psychoeducation - Patients' Experiences of Healing ProcessesDocument7 pagesEating Disorders and Psychoeducation - Patients' Experiences of Healing ProcessesMa José EstébanezNo ratings yet

- PhobiaDocument12 pagesPhobiaDiego Morales SepulvedaNo ratings yet

- Bette ResumeDocument1 pageBette Resumeapi-707499894No ratings yet

- Coping MechanismsDocument32 pagesCoping MechanismsMelissa A. Bernardo100% (1)

- The Behavioral Approach To Psychology - An Overview of Behaviorism - BetterHelpDocument10 pagesThe Behavioral Approach To Psychology - An Overview of Behaviorism - BetterHelpNavneet DhimanNo ratings yet

- Rational-Emotive-Behavior Therapy and Cognitive-Behavior TherapyDocument6 pagesRational-Emotive-Behavior Therapy and Cognitive-Behavior TherapyMary HiboNo ratings yet