Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Book Reviews: Rasul Bakhsh Rais, Imagining Pakistan: Modernism, Lexington Books, 2017), 221

Book Reviews: Rasul Bakhsh Rais, Imagining Pakistan: Modernism, Lexington Books, 2017), 221

Uploaded by

Ameena AimenCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Least Mastered Competencies (Grade 6)Document14 pagesLeast Mastered Competencies (Grade 6)Renge Taña91% (33)

- Service Excellence ManualDocument192 pagesService Excellence ManualAndrés Tomás Couvlaert SilvaNo ratings yet

- Synthesis Outline + Essay TemplateDocument7 pagesSynthesis Outline + Essay TemplatefirdausNo ratings yet

- Polarized Politics: The Challenge of Democracy in Pakistan: Nasreen AkhtarDocument34 pagesPolarized Politics: The Challenge of Democracy in Pakistan: Nasreen AkhtarAsadEjazButtNo ratings yet

- The Soul of An Octopus - Favorite QuotesDocument7 pagesThe Soul of An Octopus - Favorite QuotesTanya RodmanNo ratings yet

- All About SAP - How To Use F110 in Sap - Step by StepDocument3 pagesAll About SAP - How To Use F110 in Sap - Step by StepAnanthakumar ANo ratings yet

- The Failure of Muslim LeagueDocument8 pagesThe Failure of Muslim LeagueAqsa Riaz SoomroNo ratings yet

- BOOK REVIEW - Pakistan Beyond The Crisis State-1Document8 pagesBOOK REVIEW - Pakistan Beyond The Crisis State-1Adeel IftikharNo ratings yet

- Unrisd: Gender, Religion and The Quest For Justice in PakistanDocument42 pagesUnrisd: Gender, Religion and The Quest For Justice in Pakistaneraj.1234.nazNo ratings yet

- Pakistan An Ailing DemocracyDocument3 pagesPakistan An Ailing DemocracyFakhar -ul-ZamanNo ratings yet

- The Extremism in Pakistan A Political STDocument16 pagesThe Extremism in Pakistan A Political STKanwal MuneerNo ratings yet

- Democracy & Governance in PakistanDocument207 pagesDemocracy & Governance in PakistanEman GhazanfarNo ratings yet

- Palestinian Civil Society: A Time For Action by Amal AbusrourDocument11 pagesPalestinian Civil Society: A Time For Action by Amal AbusrourAlex MatineNo ratings yet

- Extremism in PakistanDocument5 pagesExtremism in PakistanIjlal NasirNo ratings yet

- Group Activity, Democracy in South AsiaDocument11 pagesGroup Activity, Democracy in South AsiaSeemal SheikhNo ratings yet

- Extortion (International Dynamics) : Extortion Is Offense Which Occurs When ADocument29 pagesExtortion (International Dynamics) : Extortion Is Offense Which Occurs When ASania YaqoobNo ratings yet

- Ethnic Politics in Pakistan by Nasreen AkhtarDocument23 pagesEthnic Politics in Pakistan by Nasreen AkhtarMajeed UllahNo ratings yet

- Democracy in Pakistan P2Document5 pagesDemocracy in Pakistan P2fayyaz anjumNo ratings yet

- Political DissonanceDocument5 pagesPolitical DissonanceArk RashidNo ratings yet

- Persecuting Pakistan's Minorities: State Complicity or Historic Neglect?Document20 pagesPersecuting Pakistan's Minorities: State Complicity or Historic Neglect?Shams RehmanNo ratings yet

- Pakistan - How To Revisit Political DarknessDocument6 pagesPakistan - How To Revisit Political Darknessikonoclast13456No ratings yet

- Pacific Affairs, University of British Columbia Pacific AffairsDocument15 pagesPacific Affairs, University of British Columbia Pacific AffairsZakir Hussain ChandioNo ratings yet

- Democracy in South AsiaDocument11 pagesDemocracy in South Asiasamihawk812No ratings yet

- Pakistan: Captive State by Oskar VerkaaikDocument17 pagesPakistan: Captive State by Oskar Verkaaikswapan55No ratings yet

- Constitutional Framework For An Islamic Welfare State in PakistanDocument182 pagesConstitutional Framework For An Islamic Welfare State in PakistanFaisalLaghariNo ratings yet

- Circulation of Elite in Pakistans PoliticsDocument15 pagesCirculation of Elite in Pakistans PoliticsDilawar MumtazNo ratings yet

- Cover Story (Full)Document3 pagesCover Story (Full)Laraib ArshadNo ratings yet

- Extradition - Lecture Notes 1 - IL303 - International Law - StuDocuDocument10 pagesExtradition - Lecture Notes 1 - IL303 - International Law - StuDocum zainNo ratings yet

- Democracy and Governance in PakistanDocument207 pagesDemocracy and Governance in Pakistancooll7553950No ratings yet

- Analyzing The Role of ReligionDocument12 pagesAnalyzing The Role of Religionuneebahmed047No ratings yet

- Pakistan A Hard Country (Book Review)Document6 pagesPakistan A Hard Country (Book Review)AysupNo ratings yet

- Is Democracy Suitable For PakistanDocument3 pagesIs Democracy Suitable For PakistanHizbullahNo ratings yet

- Political PolarizationDocument21 pagesPolitical PolarizationMuhammad NabeelNo ratings yet

- Books ReferencesDocument3 pagesBooks ReferencesAsadullah GandapurNo ratings yet

- CSS Essay DemocracyDocument24 pagesCSS Essay DemocracyAtta Dhaku100% (2)

- Musa Bin Naseer - 2k20-Pol SciDocument6 pagesMusa Bin Naseer - 2k20-Pol Scimusa naseerNo ratings yet

- Pakistan Between Mosque and Military ReviewDocument17 pagesPakistan Between Mosque and Military ReviewMuzaffar Abbas SipraNo ratings yet

- A Debacle in PakistanDocument2 pagesA Debacle in Pakistanইউসুফ আলী রুবেলNo ratings yet

- National Security Challenges To Pakistan PDFDocument10 pagesNational Security Challenges To Pakistan PDFJeewan Lal RathoreNo ratings yet

- Pagesfrom Religious Radicalismand Securityin South Asiach 19Document19 pagesPagesfrom Religious Radicalismand Securityin South Asiach 19Sheraz SattarNo ratings yet

- Extremism in Pakistan Causes and RemedieDocument9 pagesExtremism in Pakistan Causes and RemedieM ZainNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 111.68.103.4 On Fri, 22 Jan 2021 13:32:24 UTCDocument7 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 111.68.103.4 On Fri, 22 Jan 2021 13:32:24 UTCzubair kakarNo ratings yet

- DemocracyDocument28 pagesDemocracyRai Mohammad AshfaqNo ratings yet

- RetrieveDocument34 pagesRetrieveAsad LangrialNo ratings yet

- A Case For New Social ContractDocument2 pagesA Case For New Social ContractHussain Mohi-ud-Din QadriNo ratings yet

- Pakistan at the Crossroads: Domestic Dynamics and External PressuresFrom EverandPakistan at the Crossroads: Domestic Dynamics and External PressuresRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Terrorism in PakistanDocument17 pagesTerrorism in PakistanMuhammad ArshadNo ratings yet

- EssayDocument5 pagesEssayHassan SandhuNo ratings yet

- Why Democratic System Is Weak in Pakistan - Causes and SolutionsDocument7 pagesWhy Democratic System Is Weak in Pakistan - Causes and SolutionsOceans AdvocateNo ratings yet

- Anti-Poverty Scheme EssayDocument5 pagesAnti-Poverty Scheme EssayHassan SandhuNo ratings yet

- New Microsoft Office Word DocumentDocument12 pagesNew Microsoft Office Word DocumentHuzaifa Hussain SiddiquiNo ratings yet

- Terrorrism in PakistanDocument9 pagesTerrorrism in PakistanJawadNo ratings yet

- The Pakistan Paradox Instability and ResilienceDocument4 pagesThe Pakistan Paradox Instability and ResilienceTalha GillNo ratings yet

- Literary Essay Terrorism in Pakistan Its Causes Impacts and RemediesDocument11 pagesLiterary Essay Terrorism in Pakistan Its Causes Impacts and Remediesgull skNo ratings yet

- Essay On The Future of PakistanDocument6 pagesEssay On The Future of PakistanItrat WarriachNo ratings yet

- CSS_Essay_on_Terrorism_In_Pakistan_by_Pakistan_Education_ForumDocument23 pagesCSS_Essay_on_Terrorism_In_Pakistan_by_Pakistan_Education_ForumSair KhanNo ratings yet

- 5 - Varying Written Perspectives On Politics of PakistanDocument10 pages5 - Varying Written Perspectives On Politics of PakistanSumaira TahirNo ratings yet

- Democracy in PakistanDocument3 pagesDemocracy in Pakistanمرزا عظيم بيگ33% (3)

- Sadia Kamran - Cynicism in PakistanDocument12 pagesSadia Kamran - Cynicism in PakistanKasteer Gul KhanNo ratings yet

- Fighting The Existential BattleDocument20 pagesFighting The Existential BattleaslamkatoharNo ratings yet

- Terrorism in Pakistan: Its Causes, Impacts and RemediesDocument12 pagesTerrorism in Pakistan: Its Causes, Impacts and RemediesMuhammad TahirNo ratings yet

- Future of Democracy in PakistanDocument10 pagesFuture of Democracy in PakistansabaahatNo ratings yet

- Liberalism and ConservatismDocument3 pagesLiberalism and ConservatismfiazriazNo ratings yet

- GK 2022-MergedDocument32 pagesGK 2022-MergedAmeena AimenNo ratings yet

- Argumentative Essay For o LevelDocument2 pagesArgumentative Essay For o LevelAmeena AimenNo ratings yet

- Orientation 2K23Document1 pageOrientation 2K23Ameena AimenNo ratings yet

- Enterprise Crime: White-Collar Crime, Cyber Crime, and Organized CrimeDocument25 pagesEnterprise Crime: White-Collar Crime, Cyber Crime, and Organized CrimeAmeena AimenNo ratings yet

- Assad Marwat MergedDocument2 pagesAssad Marwat MergedAmeena AimenNo ratings yet

- CSS Writing RulesDocument7 pagesCSS Writing RulesAmeena AimenNo ratings yet

- Argumentative Essay Sample On ImmigrationDocument5 pagesArgumentative Essay Sample On ImmigrationAmeena AimenNo ratings yet

- Chapter 11Document25 pagesChapter 11Ameena AimenNo ratings yet

- Combine PDFDocument2 pagesCombine PDFAmeena AimenNo ratings yet

- National Officers Academy: Mock Exams For CSS-2022 September 2021 (Mock-5) EssayDocument1 pageNational Officers Academy: Mock Exams For CSS-2022 September 2021 (Mock-5) EssayAmeena AimenNo ratings yet

- National Officers Academy: Mock Exams CSS-2022 September 2021 (Mock-5) English (Precis and Composition)Document2 pagesNational Officers Academy: Mock Exams CSS-2022 September 2021 (Mock-5) English (Precis and Composition)Ameena AimenNo ratings yet

- Fee ChallanDocument2 pagesFee ChallanAmeena AimenNo ratings yet

- Islamophobia, Xenophobia and The Climate of Hate: European Race BulletinDocument40 pagesIslamophobia, Xenophobia and The Climate of Hate: European Race BulletinAmeena AimenNo ratings yet

- JMS January June2013 113-125Document13 pagesJMS January June2013 113-125Ameena AimenNo ratings yet

- Dawn VocabularyDocument6 pagesDawn VocabularyAmeena AimenNo ratings yet

- Paragraph Writing BasicsDocument2 pagesParagraph Writing BasicsAmeena AimenNo ratings yet

- ON-Campus Classes (Online During Lockdown)Document2 pagesON-Campus Classes (Online During Lockdown)Ameena AimenNo ratings yet

- International Political Economy.: Theories in IPE: Mercantilism, Economic Liberalism, and MarxismDocument35 pagesInternational Political Economy.: Theories in IPE: Mercantilism, Economic Liberalism, and MarxismAmeena AimenNo ratings yet

- 10 Sep 2021Document1 page10 Sep 2021Ameena AimenNo ratings yet

- Middle East CrisisDocument12 pagesMiddle East CrisisAmeena AimenNo ratings yet

- Free Online Course On PLS-SEM Using SmartPLS 3.0 - Moderator and MGADocument31 pagesFree Online Course On PLS-SEM Using SmartPLS 3.0 - Moderator and MGAAmit AgrawalNo ratings yet

- Canara BankDocument21 pagesCanara BankRajesh MaityNo ratings yet

- If ملخص قواعدDocument2 pagesIf ملخص قواعدAhmed GaninyNo ratings yet

- DMPB 9015 e Rev4Document109 pagesDMPB 9015 e Rev4mohammad hazbehzadNo ratings yet

- Print - Udyam Registration CertificateDocument2 pagesPrint - Udyam Registration CertificatesahityaasthaNo ratings yet

- DS Masteri An PhuDocument174 pagesDS Masteri An PhuPhong PhuNo ratings yet

- Week 1 - The Swamp LessonDocument2 pagesWeek 1 - The Swamp LessonEccentricEdwardsNo ratings yet

- Roger Dale Stafford, Sr. v. Ron Ward, Warden, Oklahoma State Penitentiary at McAlester Oklahoma Drew Edmondson, Attorney General of Oklahoma, 59 F.3d 1025, 10th Cir. (1995)Document6 pagesRoger Dale Stafford, Sr. v. Ron Ward, Warden, Oklahoma State Penitentiary at McAlester Oklahoma Drew Edmondson, Attorney General of Oklahoma, 59 F.3d 1025, 10th Cir. (1995)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Study Session8Document1 pageStudy Session8MOSESNo ratings yet

- Security and Privacy Issues: A Survey On Fintech: (Kg71231W, Mqiu, Xs43599N) @pace - EduDocument12 pagesSecurity and Privacy Issues: A Survey On Fintech: (Kg71231W, Mqiu, Xs43599N) @pace - EduthebestNo ratings yet

- Drill #1 With RationaleDocument12 pagesDrill #1 With RationaleRellie CastroNo ratings yet

- What Love Is ThisDocument2 pagesWhat Love Is Thisapi-3700222No ratings yet

- Stones Unit 2bDocument11 pagesStones Unit 2bJamal Al-deenNo ratings yet

- SBC Code 301Document360 pagesSBC Code 301mennnamohsen81No ratings yet

- Analysis of Old Trends in Indian Wine-Making and Need of Expert System in Wine-MakingDocument10 pagesAnalysis of Old Trends in Indian Wine-Making and Need of Expert System in Wine-MakingIJRASETPublicationsNo ratings yet

- NT Organic FarmingDocument17 pagesNT Organic FarmingSai Punith Reddy100% (1)

- How To Cook Pork AdoboDocument3 pagesHow To Cook Pork AdoboJennyRoseVelascoNo ratings yet

- DoomsdayDocument29 pagesDoomsdayAsmita RoyNo ratings yet

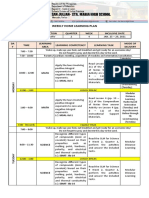

- Weekly Home Learning Plan: Grade Section Quarter Week Inclusive DateDocument3 pagesWeekly Home Learning Plan: Grade Section Quarter Week Inclusive DateMarvin Yebes ArceNo ratings yet

- Multiple Choice - JOCDocument14 pagesMultiple Choice - JOCMuriel MahanludNo ratings yet

- PDFDocument86 pagesPDFAnonymous GuMUWwGMNo ratings yet

- EoI DocumentDocument45 pagesEoI Documentudi969No ratings yet

- The Child and Adolescent LearnersDocument12 pagesThe Child and Adolescent LearnersGlen ManatadNo ratings yet

- OX App Suite User Guide English v7.6.0Document180 pagesOX App Suite User Guide English v7.6.0Ranveer SinghNo ratings yet

- Dual-Band Wearable Rectenna For Low-Power RF Energy HarvestingDocument10 pagesDual-Band Wearable Rectenna For Low-Power RF Energy HarvestingbabuNo ratings yet

Book Reviews: Rasul Bakhsh Rais, Imagining Pakistan: Modernism, Lexington Books, 2017), 221

Book Reviews: Rasul Bakhsh Rais, Imagining Pakistan: Modernism, Lexington Books, 2017), 221

Uploaded by

Ameena AimenOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Book Reviews: Rasul Bakhsh Rais, Imagining Pakistan: Modernism, Lexington Books, 2017), 221

Book Reviews: Rasul Bakhsh Rais, Imagining Pakistan: Modernism, Lexington Books, 2017), 221

Uploaded by

Ameena AimenCopyright:

Available Formats

Book Reviews

BOOK REVIEWS

Rasul Bakhsh Rais, Imagining Pakistan: Modernism,

State, and The Politics of Islamic Revival (Lanham:

Lexington Books, 2017), 221.

Reviewed by Dr Eamon Murphy, Adjunct Professor, School of Media,

Creative Arts and Social Inquiry, Curtin University, Australia.

The central theme of this highly topical insightful book by political

scientist Dr Rasul Bakhsh Rais of the Department of Humanities and

Social Sciences, Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS),

Lahore is the parlous state of Pakistan’s fragile democracy,

particularly the unresolved issue of national identity. The analysis

throughout is characterised by Rais’ high-quality scholarship, his deep

understanding of the country’s society and politics, and his passionate

commitment to the ideal of a strong modern democratic nation. The

six main chapters provide a highly incisive in-depth analysis of the

ideological, historical and political roots of the current crises in

Pakistan’s democracy.

Rais is under no illusion about the many problems facing

Pakistan, one that is often characterised as a dysfunctional nuclear

state, which is facing a crossroad in its history. Among the major

threats he identifies are the failure of state institutions, widespread

poverty, abuses of human rights, a shamefully inadequate mass

education, the breakdown of law and order, a highly corrupt political

system, ethnic and religious violence and regular mob violence fuelled

by Islamic extremists which undercuts the authority of elected

governments.

__________________________________________

@2019 by the Islamabad Policy Research Institute.

IPRI Journal XIX (1): 179-193.

IPRI JOURNAL WINTER 2019 179

Book Reviews

The author excoriates the arrogant traditional landholding feudal

elites who have dominated the country’s political parties, subverted

democracy and plundered the state for personal and family gain. He

clearly identifies the rampant corruption, lack of justice and misrule

which have led to disillusionment and cynicism and have resulted in

despair and frustration, especially among the young which has

contributed to the rise of extremism and terrorism. The second culprit

in the decline of democracy is the authoritarian military which has

dominated politics and ruled Pakistan, either directly through four

military coups, or indirectly interfering in the democratic process, for

much of its history. The most disastrous period of military rule was

that of General Zia-ul-Haq which greatly damaged the democratic

process, resulted in gross abuses of human rights and accelerated the

growth of terrorism and sectarian violence. The third obstacle has

been the emergence of a fundamentalist political Islam with a radical

violent fringe which considers democracy, constitutionalism and the

supremacy of civil law as alien Western concepts. The combination of

an authoritarian military and corrupt political elites, and their

alliances with extremist religious demagogues, have suffocated and

threatened to destroy Pakistan’s democracy altogether.

Rais is adamant that all too often politicians and the media have

blamed outside forces, particularly Pakistan’s archenemy, India. He is

open and frank about sensitive controversial issues. He argues, for

instance, that there must be a negotiated settlement with India over the

highly emotional issue of Kashmir. He also recognises the meddling

of Wahhabi Saudi Arabia and Shia Iran which have long waged a

proxy ideological and strategic war in Afghanistan and Pakistan. He

condemns the cynical and inconsistent policies of the United States

culminating in the disastrous invasions of Afghanistan, and later Iraq,

and the dragging of Pakistan into the ongoing counterproductive failed

War on Terror (WoT). But while geopolitical problems have

significantly contributed to the decline of the state, Rais is adamant

that the solution must be found within Pakistan and must be resolved

by its citizens.

180 IPRI JOURNAL WINTER 2019

Book Reviews

According to the writer, the solution to Pakistan’s crisis is clear.

The country needs to return to the principles of its liberal founders

and to start rebuilding state institutions in order to create a modern

democratic, constitutional and pluralistic state governed by the rule of

law, equality for all citizens and open and fair elections. He contrasts

the current state of democracy, that is far removed from that imagined

by the founders of Pakistan, led by Muhammad Ali Jinnah. Its

founders’ dream was that of a pluralistic, liberal, modern, democratic

state which would protect the rights of the Muslim majority in the

subcontinent but one in which all citizens, irrespective of birth, sect,

ethnic background or religion, would have full rights as citizens.

While the exact position of Islam in the constitution and legal

system of the new state was never clearly set out, Pakistan’s founders

were strongly influenced by Islamic modernism, a rational approach to

Muslim thought and practice leading to the reform of religion through

interpretation (Ijtihad) and consensus (Ijma). They believed that

modernism would restore the strength, dynamism and adaptability of

Muslim societies through modern science, reasoning and technology.

He argues that Islamic modernism is fully compatible with

democracy. Religion, according to this perspective, is to be largely a

private matter and politics best left to the political realm.

Rais is cautiously optimistic that while Pakistan has many of the

symptoms of a failing state, its citizens and society have been

remarkably resilient. Although gravely weakened by patronage

politics, praetorian military rule and extremist Islam, parliamentary

democracy has somehow managed to survive. Elections are regularly

held at local, provincial and central legislatures consequently

maintaining the tradition and practice of democracy. The second

positive factor has been the emergence of a strong and ever-growing

articulate middle class, now over 40 per cent of the population, which

has created a new political dynamic challenging the traditional landed

political elite. In addition, Pakistan has a free highly vibrant critical

nationwide English and Urdu print and electronic media. Yet another

positive indicator has been the findings of opinion polls which support

the view that while many Pakistanis are devout Muslims, the majority

reject terrorism and religious extremism. Religious political parties

IPRI JOURNAL WINTER 2019 181

Book Reviews

have generally polled very poorly in elections as Pakistanis have

demonstrated that they are most concerned about bread and butter

issues such as the cost of living, shortages in basic commodities and

power failures. Finally, despite the growth of fundamentalist Islam,

most Pakistanis still follow the tolerant syncretism Sufi Islam that has

characterised the Islam that took root in the Indian subcontinent.

Imagining Pakistan was published before the victory of Imran

Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (Pakistan Movement for Justice) in

the 2018 General Elections. Analysis of the election results suggests a

changing Pakistan which has started to reject the long-established

political dominance of the landed feudal elites. His many supporters,

especially among the young, were motivated by his promise to root

out corruption, create a new stable prosperous Naya Pakistan (New

Pakistan), tackle poverty, remove the barriers to social mobility and

revitalise its decaying infrastructure. Whether Khan, and the idealists

among his party, will have the courage and authority to be able to

resist the entrenched vested interests of the traditional elite, the power

of the military and the strength of extremist Islam is very much an

open question.

A fundamental question arising from this volume is whether

Pakistan will return to the quasi-secular democratic state as imagined

by its founders or whether there will emerge some sort of a sensible

compromise between strong advocates of modernism, the moderate

clergy who reject violence, and the stability provided by a strong but

largely apolitical military. Whatever the outcome, Rais’ thought-

provoking book is invaluable as it provides a deep understanding of

the complex problems, challenges and prospects facing Pakistan’s

struggling democracy. Such an understanding is a fundamental

prerequisite to initiating effective reform.

182 IPRI JOURNAL WINTER 2019

Book Reviews

Philip Murphy, The Empire’s New Clothes: The Myth

of the Commonwealth (London: Hurst Publishers,

2018), 256.

Reviewed by Ambassador (R) Shahid M. G. Kiani.

Philip Murphy’s book on the Commonwealth, The Empire’s New Clothes,

may be reminiscent of what Dr Mahathir Mohamad, Malaysia’s Prime

Minister, once said in a 2014 interview about this association, which may

not appear very enviable to many. He challenged its very name by calling

it ‘a misnomer’. He went on to elaborate that ‘wealth’ is not ‘common’ at

all. It belongs to only four members and the rest are poor. So, calling it

‘the Commonwealth’, that is common, when obviously wealth is not

common’ is problematic. While Murphy may not be in total agreement

with Mahathir’s estimation of the Commonwealth, his own deep

skepticism about it would not leave many readers cheering.

Post-1945 saw Britain, roaring that it had won the war, but faced

difficulty in admitting a much loosened grip over its colonies, which were

gradually attaining independent status. They were ‘rewarded’ with

membership of the Commonwealth. For the members, the

intergovernmental organisation stood for closer ties to the once ‘rulers’,

with the media splashing news of biennial summits and photos showing a

beaming Nehru of India, Nkrumah of Ghana, Kaunda of Zambia and

Nyerere of Tanzania - freedom struggle stalwarts standing shoulder-to-

shoulder with the Queen. The stalwarts, who had struggled through

peaceful, and at times, democratic means to achieve freedom, may not

have found it dichotomous standing together with their once colonisers in

an intergovernmental institution. Nehru was on record admitting that he

found ‘nothing wrong in being a member of the Commonwealth’ (p. 25) -

added advantage - the Commonwealth also stands for ‘shared values of

democracy’ (Commonwealth Charter). During the early post-World War

II years, Britain was more focused on its domestic issues and struggling to

find its ‘rightful’ place in Europe. The Commonwealth, unsurprisingly,

took a back seat, at least for the British Government. For the Queen and

the other royalty, nostalgia for the ‘empire’ had never diminished.

IPRI JOURNAL WINTER 2019 183

Book Reviews

The author headed the Commonwealth Institute for many years, and

is well placed to give his opinion on the subject. Not only does the author

consider the association having limited significance in British foreign

policy (p.8), but comes down hard on those who led the ‘leave EU

Campaign’, and whose naivety surprises him when they considered that

the Commonwealth could replace the European Union (p. 292). How did

these Brexit supporters come to the conclusion that Commonwealth

member states will welcome its exit from the EU when all estimates

pointed to the contrary. The United Kingdom (UK) for Commonwealth

states is a source of strength as they negotiate agreements, especially

trade. Ironically, Brexit is in one big fix already. As the deadline to leave

the EU approaches, not only does UK’s financial sector shudder, but it

also puts a big question mark on Prime Minister May’s political career,

the leader entrusted to steer it. This could possibly be the end of the road

for her political career.

Murphy should have given more credit to Commonwealth’s

contribution in reducing space for racist regimes in Africa. The 1979

Commonwealth Summit in Lusaka, Zambia was a jolt to Prime Minister

Thatcher’s adamant stand on the Zimbabwe-Rhodesia racist Smith regime.

The Lusaka Declaration, issued against a backdrop of political turmoil in

Zimbabwe, helped contribute to the end of white minority rule in that

country (Fifth Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting

[CHOGM]). The British elite, of which Mrs. Thatcher was a part, had first

hoped that the Commonwealth would preserve and project British

influence. However, it seemed this eagerness decreased as Britain’s

policies came under criticism in the Commonwealth meetings. Ironically,

while the Commonwealth members were adamant that the UK push

sanctions against South Africa’s apartheid regime, it made no difference

to Mrs. Thatcher, as she continued to refuse this demand, even to the

annoyance of the Queen. One cannot also dispute Murphy’s estimation

that public opinion in the UK became negative as immigration from non-

white member states increased. The immigrants’ way of life and culture

added to the negative public opinion.

On the plus side, Murphy explains at length the discussions in

Commonwealth meetings in the context of ‘shared values of democracy’.

184 IPRI JOURNAL WINTER 2019

Book Reviews

The association had suspended several members ‘from the Councils of the

Commonwealth’ for ‘serious or persistent violations’ of the Harare

Declaration of 1989, particularly in abrogating their responsibility to have

a democratic government (p.36). Nigeria and Pakistan took a fair amount

of criticism, for having non-democratic institutions. Moral pressure

remained on Pakistan, as an aide-mémoire of an ‘aberration’, which

needed correction.

Murphy recounts the various phases of the Commonwealth in the

1960s which he describes as efforts to contain the ‘centrifugal forces of

push and pull’ of its members, which robbed it of much of its practical

value (p. 20). The UK’s jugglery to maintain a semblance of ‘grandeur’

and efforts to join the European Economic Community (EEC), only to

face failure in 1963, also added to the Commonwealth woes. The 60s were

a difficult period due to left leaning pro-independence movements in

colonial Africa and self-confident French leader de Gaulle, who left no

opportunity to assail Britain.

Murphy is uncomfortable with the ‘hereditary’ monarch being head

of the Commonwealth. Facts on the ground may be contrary as the Queen

and her family has immense respect in member countries. If not the

British royal family, then who shall head the Commonwealth? This can

trigger another headache of consensus-building, making to the election of

the organisation’s Secretary General, a highly contested one. Prince

Charles, an unconventional royal, succeeding the Queen is also

problematic for Murphy (p.98). However, he ignores the fact that there is

a sea of difference between being a head of state and the symbolic head of

an intergovernmental organisation.

By the end of the book, Murphy sounds the ‘death knell’ for the

Commonwealth and wants its total disbandment (p.232) since he finds

little use of this organisation. Any poll will suggest that this extreme step

shall have no backers. Disbanding the Commonwealth, an institution

which took decades to build, needs very serious soul searching. Reforms

may be the right way. Let the Commonwealth reinvent itself as a major

development partner. Blunting its critics, it can continue welfare

programmes, as it is doing so already. Developed members and member

states who are emerging economies can contribute in funding the

immensely important health and education sectors of the most needy

IPRI JOURNAL WINTER 2019 185

Book Reviews

members. A reformed Commonwealth shall find major supporters, among

all members, as these sectors are numero uno priority for them.

Murphy’s critique on many aspects of the present state of the

Commonwealth is indeed valid and may also resonate with its other

critics. However, it is difficult, if not impossible to support his total

dissolution notion. He finds many weaknesses in the organisation, but

none solidly convincing of its dissolution. Other such global institutions

function, with all their flaws and even flourish. The United Nations (UN)

has its critics, but a world without it will be a very different place. The

Muslim world is even tolerating the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation

(OIC), even though the ‘all important’ global body has hardly any

successes to its credit - part of the Muslim world continues to be aflame,

as OIC stands as a bystander. The rise of right wing parties in Europe

threatens the EU, but there are bigger supporters for its strengthening and

bringing reforms.

53 states straddling the globe ‘own’ the Commonwealth, in one way

or the other. Even if it is only credited in bringing together its 53 leaders

at different intervals, who may otherwise find it challenging to meet and

exchange ideas, it has performed an important function. Given a chance,

the Commonwealth has enough talent for its reform. It can restructure and

thrive!

186 IPRI JOURNAL WINTER 2019

Book Reviews

Sulmaan Wasif Khan, Haunted by Chaos: China’s

Grand Strategy from Mao Zedong to Xi Jinping

(Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2018), 336.

Reviewed by Muhammad Shoaib, COMSATS University, Vehari

Campus, Pakistan.

A state with virtually no boundaries, permanent population, and strong

government did not make sense; yet, Mao Zedong remained resilient in

his conviction to create and rule his state in this fashion. He had a

government, eager to launch an array of reforms and bring change in

society. His was a China conceived within the greater China that had

existed after the Warring States’ period. A moveable China, however, was

eager to forge relations with other parties and states. What remained

important for Mao was the task of ensuring the survival and existence of

the China he had conceived. Fear and ambition shaped his thoughts, for

fear generated ambition. At times, therefore, his targets changed. Nothing

was impossible, ranging from negotiations with Nationalists to war with

them. Mao’s China remained a movable agent with him as the head of the

government and the party that ruled it.

The way to understand Mao’s struggle for Communist China goes

through the Chinese context after 1911. Warlords had their strongholds,

and the government was, in today’s sense, nowhere. (What existed

everywhere was chaos and the power of the barrel - that Mao himself had

embraced). Mao’s China, nevertheless, survived and expanded.

Challenges, after creation of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in

1949, were daunting. Changed context - poverty, war, a longing to

reclaim, and presence of an enemy in the neighbourhood - was a constant

reminder of the importance of an appropriate Grand Strategy.

With circumstance, changed the pillars of Mao’s Grand Strategy.

However, the objective remained the same: survival of the state - possible

only under the rule of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). But now,

Mao’s China had to circumnavigate the rivalry between the United States

(US) and the Soviet Republic. Conflict in the Korean Peninsula troubled

Mao’s calculations (at a time when he was planning to reclaim Taiwan),

but prudence and clarity of purpose prevailed - he sent his Chinese

IPRI JOURNAL WINTER 2019 187

Book Reviews

People’s Volunteers (CPV) into the Korean theatre. A war, started at the

expense of Taiwan, was eventually a win. The Americans were stopped

and sent a message. The war also exposed the strengths and weaknesses of

alliance with Stalin’s Soviet Union -Mao, after the Korean War, would

often test the limits of the Soviets and Americans, but keep his options

open. Almost at the same time, the PRC expanded its circle of friends and

allies and reached virtually all the developing countries. It is this context

that Sulmaan Wasif Khan, Assistant Professor of International History and

Chinese Foreign Relations at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy,

Tufts University, emphasises in his Haunted by Chaos: China’s Grand

Strategy from Mao Zedong to Xi Jinping. According to Khan, Mao’s

Grand Strategy focused on the survival and security of his state that was

only possible under the rule of the CCP. Given Khan’s account of the war

with India, friendship with Pakistan, clash with the Soviet Republic, and

the relationship with the US, the PRC’s Grand Strategy appears apt to

achieve its strategic goals.

Mao’s successors, particularly Deng Xiaoping, too did not forget

the bitter lessons learned in the pre-1949 period. A strong government was

essential to rule a state as large and populous as the PRC. But the

populace was not to be ignored. People had not supported the CCP to

endure hunger, Deng knew. It was, thus, necessary to make the PRC

prosperous; it was necessary for the PRC’s survival - Mao would have

done the same, he advocated. Khan shows in the chapter on Deng that the

latter was daring as well as cautious; he advocated economic liberalism,

trade, and modernisation, but maintained tight control on the state.

Cautious opening and a careful but prudent external policy were his

hallmarks. But for dissent, he had no tolerance. Anyone who threatened

(or could threaten) the survival of the state or party, had to face the PRC

and him. He could be warm towards the British, but unyielding about

anything short of Hong Kong. There was nothing wrong with getting rich

in his China, but everything was wrong with challenging authority, be it a

student group or CCP member.

While Mao and Deng were revolutionaries, their successors were

young who needed to be appropriately indoctrinated, but not charismatic -

because Deng had seen the horrors charisma could cause. What defined

188 IPRI JOURNAL WINTER 2019

Book Reviews

his successors, both Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao, was the virtue of dullness.

Khan’s book provides sufficient evidence on the context in which Deng’s

successors worked to amplify their predecessors’ gains. An interesting

aspect he highlights is the need for ‘doing more’ which Deng’s successors

felt. Jiang brought in indoctrination, nationalism, and rigorous education

along party lines. Dissent was a threat to the state, so was any organised

group.

The virtue of dullness also extended to Hu’s reign. He, too,

emphasised CCP’s control on policymaking, but struggled with the

People’s Liberation Army (PLA) - the latter exceeded its apparent,

constitutional limits and left the leader abashed in front of his guest.1 His

was, however, an era of transition when China started asserting itself. But

the climax was perhaps left for Xi Jinping, son of a veteran CCP member

who endured the calamity of the Cultural Revolution. Xi went a step

ahead of Jiang and Hu. He embarked on a campaign against corruption,

implicated CCP members, PLA veterans, and prosperous businessmen -

partly in an endeavour to consolidate his rule. He played assertively on the

external front, used China’s growing power abroad, launched an ambitious

infrastructure plan, and established new financial institutions that could

provide an alternative to the developing world.

The strength of Haunted by Chaos lies in its use of primary sources

and focus on the generally less emphasised topic of ‘Grand Strategy’. The

clarity of the author’s argument amplifies the gains. From Mao to Xi, all

CCP leaders’ objective has been the same: survival (existence) of the state

- that is synonymous with CCP’s survival. Both are inseparable. However,

Khan also makes it clear that the wise grand strategists of China were

humans too. Cultural Revolution and war with Vietnam were not the

wisest of courses, even if the state survived. Khan does not forget to

highlight the problems in China that shape the context in which Xi rules.

His are not the words of hope, however, and he dismisses the bright side

of China - a country that traversed difficult times and prospered against

the odds.

1

Editor’s Note: China conducted the first test flight of its stealth fighter, in January 2011,

hours before former US Defense Secretary Robert Gates sat down with President Hu

Jintao (who appeared to not have heard about the flight) in Beijing.

IPRI JOURNAL WINTER 2019 189

Book Reviews

Elizabeth C. Economy, The Third Revolution: Xi

Jinping and the New Chinese State (New York: Oxford

University Press, 2018), 360.

Reviewed by Maryam Nazir, Assistant Research Officer, Islamabad

Policy Research Institute (IPRI), Pakistan.

Elizabeth C. Economy is Director of Asia Studies and C.V. Starr Senior

Fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR), New York, USA. In

her recent publication, The Third Revolution: Xi Jinping and the New

Chinese State, Economy explains ‘how the Chinese leadership has moved

forward to advance its objectives and what have been the intended and

unintended consequences of the new approach in recent years’ (p. 12). She

asserts that while China’s influence in world affairs is growing rapidly,

contradictions are inherent in the system as it desires to shape the

predominant liberal world order. Apart from introspecting about Xi’s

personality and his Chinese Dream, the book offers a retrospect on a range

of reforms including political and cyber arenas, the most visible -

environmental pollution, economic concerns such as issues of corruption,

innovation and state-owned enterprises and China’s foreign and security

policies.

The author believes that President Xi has made significant progress

towards achieving his Chinese Dream, and the priorities he has set out for

his next five-year term are the same that he has pursued to date, which

speaks of his consistency. However, with China witnessing its

transformation as a global power, Economy asserts that history is not on

Xi Jinping’s side. ‘Despite a rollback of democracy in some parts of the

world, all the major economies of the world – save China – are all

democracies… world must deal with China as it is today. The strategic

direction of Xi’s leadership is evident and is exerting a profound impact

on Chinese political and economic life and country’s international

presence. Much of the world remains ill-prepared to understand and

navigate these changes’ (p. 19).

190 IPRI JOURNAL WINTER 2019

Book Reviews

Analysing the political persona of President Xi Jinping, Economy

notes that ‘Xi has emerged as the descendent of both Mao and Deng’ (p.

23). She adds that in recent years, Xi has accumulated significant

authority over virtually all policies. By pushing aside decades of collective

and institutionalised decision-making, he has centralised power in his own

hands. Analysts believe that this consolidation is necessary and beneficial

in order to run the clean-up protocol inside the Party, and push for

economic and other reforms in general.

As Xi has committed to eliminating corruption from the core,

Economy asserts that the current system is reversing the trend of reform

and opening up, preventing influx of foreign ideas and narrowing the

space for debate and dissent (p. 53). She believes that the accomplishment

of Xi’s vision requires a detailed recalibration of the state’s relationship

with its citizenry as well as the outside world. Whereby President Xi

makes no distinction between the real and virtual political worlds (i.e.,

both should reflect the same political values, standards and ideals), he

believes that Chinese society and its practices must be a reflection of

Chinese dreams and relevant endeavours (p. 58).

While China has evolved as an economic powerhouse in recent

years, ‘it has [also] developed technological upgrades to increase the

state’s potent capacity to monitor and prevent content from entering and

circulating throughout the country’ (p. 59). The West’s version of the

Internet, which is widely called as ‘Chinanet’ in the country, has been

regarded as an anathema to the values of the Chinese Government, by Xi.

Given the pattern that Chinese Government follows, it can be inferred that

the state wants to control the Internet as a potential source of political

change. The author believes that:

…for the international community, Beijing’s cyber policy is

representative of the challenge that a more powerful China

presents to the liberal world order, which prioritizes political

values such as freedom of speech, as opposed to China’s effort

to constrain the range of ideas on the Internet. It also reflects

the paradox inherent in China’s efforts to promote itself as a

champion of globalization, while simultaneously advocating a

IPRI JOURNAL WINTER 2019 191

Book Reviews

model of Internet sovereignty and closing its cyber world to

information and investment from abroad (p. 90).

Writing broadly about China being an ‘Innovation Nation’,

Economy stresses that Xi has made his unhappiness clear with the current

state of China’s innovation strategy, but as the system incentivises this

strategy, little attention is being given to ‘invention’ as per Western

models. Kevin Wale, Head of General Motors in China describes the

‘Chinese as innovating through commercializing… unlike the Western

methods of research, testing and validation, the Chinese will bring

something to market and innovate based on consumer wants’ (p. 124); and

this works for them.

Economy dedicates a chapter to China’s foreign policy and its

overall global outlook, an area which impacts the world, the most. She

writes that ‘many people around the world might question China’s

peaceful and amiable rise but none would doubt Xi’s assertion that the

lion has awakened’ (p. 186). China has done really well in the numbers

game as it has developed itself in an unimaginable manner over the last

few decades. While global economies witnessed recession and slowing

down, China was able to stand tall independently. According to the

author, in the current world order, China has the desire to use its power to

influence others and establish global rules of the game (p. 187). Xi’s

repeated call for a ‘new type of relationship among major countries’,

creation of parallel forums like the Shanghai Cooperation

Organization (SCO), China Development Bank (CDB) and Asian

Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB); and growing responsiveness in the

United Nations (UN) and World Trade Organization (WTO) are few

examples to quote.

China, in today’s order will definitely like being heard, consulted

and followed as it is an economic and military power with 20 per cent of

the world’s population. In recent years, China has not only come up with

counters, its policy has seen a shift from staking to securing. Its Belt and

Road Initiative (BRI), stance in South and East China Sea and growing

interest in the Arctic region are cases in point. As it turns East now and

witnesses’ ‘fluid’ dynamic of politics in the region, China sees world as its

Oyster. Under its strategy of Cultural Conditioning and use of Soft Power,

192 IPRI JOURNAL WINTER 2019

Book Reviews

the Republic has been able to promote its language and culture

respectively, worldwide (p. 219).

While there exists a lot of literature regarding the United States’

perception of China and how it wants to maintain its relations with an

emerging power, history tells us that the US has always assured China of

mutual cooperation, but simultaneously worked on parallel plans with

regional states to encircle it. Beijing not only sees such advancements as a

counter to its plan, but also detrimental to its interests and influence in the

region. For the moment, President Xi is filing the vacuum of global

leadership left by President Trump’s ‘America First’ policy (p. 229).

Economy’s road forward suggests that ‘diplomacy’ must be given a

chance here. She asserts that as President Trump withdraws from

international accords and preaches his ‘America First’ policy, Xi’s

proposal of collective benefit makes him a more acceptable leader

globally. This makes people skirt the issue of China’s true capabilities to

manage global affairs, whether it is North Korea’s nuclear proliferation or

the refugee crisis in Myanmar. In both cases, Beijing was not able to put

forward a workable solution.

Though China has been successful in managing its economy and

military affairs, it is yet to deal with issues of corruption, state-owned

enterprises, slowing growth, pollution and indigenous innovation. This

book provides a strong overview about Xi Jinping, with detailed historical

background. Suffice to say, just because he has been around the world and

successful in creating a powerful image of China, does not mean that there

are no troubled waters back home.

IPRI JOURNAL WINTER 2019 193

You might also like

- Least Mastered Competencies (Grade 6)Document14 pagesLeast Mastered Competencies (Grade 6)Renge Taña91% (33)

- Service Excellence ManualDocument192 pagesService Excellence ManualAndrés Tomás Couvlaert SilvaNo ratings yet

- Synthesis Outline + Essay TemplateDocument7 pagesSynthesis Outline + Essay TemplatefirdausNo ratings yet

- Polarized Politics: The Challenge of Democracy in Pakistan: Nasreen AkhtarDocument34 pagesPolarized Politics: The Challenge of Democracy in Pakistan: Nasreen AkhtarAsadEjazButtNo ratings yet

- The Soul of An Octopus - Favorite QuotesDocument7 pagesThe Soul of An Octopus - Favorite QuotesTanya RodmanNo ratings yet

- All About SAP - How To Use F110 in Sap - Step by StepDocument3 pagesAll About SAP - How To Use F110 in Sap - Step by StepAnanthakumar ANo ratings yet

- The Failure of Muslim LeagueDocument8 pagesThe Failure of Muslim LeagueAqsa Riaz SoomroNo ratings yet

- BOOK REVIEW - Pakistan Beyond The Crisis State-1Document8 pagesBOOK REVIEW - Pakistan Beyond The Crisis State-1Adeel IftikharNo ratings yet

- Unrisd: Gender, Religion and The Quest For Justice in PakistanDocument42 pagesUnrisd: Gender, Religion and The Quest For Justice in Pakistaneraj.1234.nazNo ratings yet

- Pakistan An Ailing DemocracyDocument3 pagesPakistan An Ailing DemocracyFakhar -ul-ZamanNo ratings yet

- The Extremism in Pakistan A Political STDocument16 pagesThe Extremism in Pakistan A Political STKanwal MuneerNo ratings yet

- Democracy & Governance in PakistanDocument207 pagesDemocracy & Governance in PakistanEman GhazanfarNo ratings yet

- Palestinian Civil Society: A Time For Action by Amal AbusrourDocument11 pagesPalestinian Civil Society: A Time For Action by Amal AbusrourAlex MatineNo ratings yet

- Extremism in PakistanDocument5 pagesExtremism in PakistanIjlal NasirNo ratings yet

- Group Activity, Democracy in South AsiaDocument11 pagesGroup Activity, Democracy in South AsiaSeemal SheikhNo ratings yet

- Extortion (International Dynamics) : Extortion Is Offense Which Occurs When ADocument29 pagesExtortion (International Dynamics) : Extortion Is Offense Which Occurs When ASania YaqoobNo ratings yet

- Ethnic Politics in Pakistan by Nasreen AkhtarDocument23 pagesEthnic Politics in Pakistan by Nasreen AkhtarMajeed UllahNo ratings yet

- Democracy in Pakistan P2Document5 pagesDemocracy in Pakistan P2fayyaz anjumNo ratings yet

- Political DissonanceDocument5 pagesPolitical DissonanceArk RashidNo ratings yet

- Persecuting Pakistan's Minorities: State Complicity or Historic Neglect?Document20 pagesPersecuting Pakistan's Minorities: State Complicity or Historic Neglect?Shams RehmanNo ratings yet

- Pakistan - How To Revisit Political DarknessDocument6 pagesPakistan - How To Revisit Political Darknessikonoclast13456No ratings yet

- Pacific Affairs, University of British Columbia Pacific AffairsDocument15 pagesPacific Affairs, University of British Columbia Pacific AffairsZakir Hussain ChandioNo ratings yet

- Democracy in South AsiaDocument11 pagesDemocracy in South Asiasamihawk812No ratings yet

- Pakistan: Captive State by Oskar VerkaaikDocument17 pagesPakistan: Captive State by Oskar Verkaaikswapan55No ratings yet

- Constitutional Framework For An Islamic Welfare State in PakistanDocument182 pagesConstitutional Framework For An Islamic Welfare State in PakistanFaisalLaghariNo ratings yet

- Circulation of Elite in Pakistans PoliticsDocument15 pagesCirculation of Elite in Pakistans PoliticsDilawar MumtazNo ratings yet

- Cover Story (Full)Document3 pagesCover Story (Full)Laraib ArshadNo ratings yet

- Extradition - Lecture Notes 1 - IL303 - International Law - StuDocuDocument10 pagesExtradition - Lecture Notes 1 - IL303 - International Law - StuDocum zainNo ratings yet

- Democracy and Governance in PakistanDocument207 pagesDemocracy and Governance in Pakistancooll7553950No ratings yet

- Analyzing The Role of ReligionDocument12 pagesAnalyzing The Role of Religionuneebahmed047No ratings yet

- Pakistan A Hard Country (Book Review)Document6 pagesPakistan A Hard Country (Book Review)AysupNo ratings yet

- Is Democracy Suitable For PakistanDocument3 pagesIs Democracy Suitable For PakistanHizbullahNo ratings yet

- Political PolarizationDocument21 pagesPolitical PolarizationMuhammad NabeelNo ratings yet

- Books ReferencesDocument3 pagesBooks ReferencesAsadullah GandapurNo ratings yet

- CSS Essay DemocracyDocument24 pagesCSS Essay DemocracyAtta Dhaku100% (2)

- Musa Bin Naseer - 2k20-Pol SciDocument6 pagesMusa Bin Naseer - 2k20-Pol Scimusa naseerNo ratings yet

- Pakistan Between Mosque and Military ReviewDocument17 pagesPakistan Between Mosque and Military ReviewMuzaffar Abbas SipraNo ratings yet

- A Debacle in PakistanDocument2 pagesA Debacle in Pakistanইউসুফ আলী রুবেলNo ratings yet

- National Security Challenges To Pakistan PDFDocument10 pagesNational Security Challenges To Pakistan PDFJeewan Lal RathoreNo ratings yet

- Pagesfrom Religious Radicalismand Securityin South Asiach 19Document19 pagesPagesfrom Religious Radicalismand Securityin South Asiach 19Sheraz SattarNo ratings yet

- Extremism in Pakistan Causes and RemedieDocument9 pagesExtremism in Pakistan Causes and RemedieM ZainNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 111.68.103.4 On Fri, 22 Jan 2021 13:32:24 UTCDocument7 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 111.68.103.4 On Fri, 22 Jan 2021 13:32:24 UTCzubair kakarNo ratings yet

- DemocracyDocument28 pagesDemocracyRai Mohammad AshfaqNo ratings yet

- RetrieveDocument34 pagesRetrieveAsad LangrialNo ratings yet

- A Case For New Social ContractDocument2 pagesA Case For New Social ContractHussain Mohi-ud-Din QadriNo ratings yet

- Pakistan at the Crossroads: Domestic Dynamics and External PressuresFrom EverandPakistan at the Crossroads: Domestic Dynamics and External PressuresRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Terrorism in PakistanDocument17 pagesTerrorism in PakistanMuhammad ArshadNo ratings yet

- EssayDocument5 pagesEssayHassan SandhuNo ratings yet

- Why Democratic System Is Weak in Pakistan - Causes and SolutionsDocument7 pagesWhy Democratic System Is Weak in Pakistan - Causes and SolutionsOceans AdvocateNo ratings yet

- Anti-Poverty Scheme EssayDocument5 pagesAnti-Poverty Scheme EssayHassan SandhuNo ratings yet

- New Microsoft Office Word DocumentDocument12 pagesNew Microsoft Office Word DocumentHuzaifa Hussain SiddiquiNo ratings yet

- Terrorrism in PakistanDocument9 pagesTerrorrism in PakistanJawadNo ratings yet

- The Pakistan Paradox Instability and ResilienceDocument4 pagesThe Pakistan Paradox Instability and ResilienceTalha GillNo ratings yet

- Literary Essay Terrorism in Pakistan Its Causes Impacts and RemediesDocument11 pagesLiterary Essay Terrorism in Pakistan Its Causes Impacts and Remediesgull skNo ratings yet

- Essay On The Future of PakistanDocument6 pagesEssay On The Future of PakistanItrat WarriachNo ratings yet

- CSS_Essay_on_Terrorism_In_Pakistan_by_Pakistan_Education_ForumDocument23 pagesCSS_Essay_on_Terrorism_In_Pakistan_by_Pakistan_Education_ForumSair KhanNo ratings yet

- 5 - Varying Written Perspectives On Politics of PakistanDocument10 pages5 - Varying Written Perspectives On Politics of PakistanSumaira TahirNo ratings yet

- Democracy in PakistanDocument3 pagesDemocracy in Pakistanمرزا عظيم بيگ33% (3)

- Sadia Kamran - Cynicism in PakistanDocument12 pagesSadia Kamran - Cynicism in PakistanKasteer Gul KhanNo ratings yet

- Fighting The Existential BattleDocument20 pagesFighting The Existential BattleaslamkatoharNo ratings yet

- Terrorism in Pakistan: Its Causes, Impacts and RemediesDocument12 pagesTerrorism in Pakistan: Its Causes, Impacts and RemediesMuhammad TahirNo ratings yet

- Future of Democracy in PakistanDocument10 pagesFuture of Democracy in PakistansabaahatNo ratings yet

- Liberalism and ConservatismDocument3 pagesLiberalism and ConservatismfiazriazNo ratings yet

- GK 2022-MergedDocument32 pagesGK 2022-MergedAmeena AimenNo ratings yet

- Argumentative Essay For o LevelDocument2 pagesArgumentative Essay For o LevelAmeena AimenNo ratings yet

- Orientation 2K23Document1 pageOrientation 2K23Ameena AimenNo ratings yet

- Enterprise Crime: White-Collar Crime, Cyber Crime, and Organized CrimeDocument25 pagesEnterprise Crime: White-Collar Crime, Cyber Crime, and Organized CrimeAmeena AimenNo ratings yet

- Assad Marwat MergedDocument2 pagesAssad Marwat MergedAmeena AimenNo ratings yet

- CSS Writing RulesDocument7 pagesCSS Writing RulesAmeena AimenNo ratings yet

- Argumentative Essay Sample On ImmigrationDocument5 pagesArgumentative Essay Sample On ImmigrationAmeena AimenNo ratings yet

- Chapter 11Document25 pagesChapter 11Ameena AimenNo ratings yet

- Combine PDFDocument2 pagesCombine PDFAmeena AimenNo ratings yet

- National Officers Academy: Mock Exams For CSS-2022 September 2021 (Mock-5) EssayDocument1 pageNational Officers Academy: Mock Exams For CSS-2022 September 2021 (Mock-5) EssayAmeena AimenNo ratings yet

- National Officers Academy: Mock Exams CSS-2022 September 2021 (Mock-5) English (Precis and Composition)Document2 pagesNational Officers Academy: Mock Exams CSS-2022 September 2021 (Mock-5) English (Precis and Composition)Ameena AimenNo ratings yet

- Fee ChallanDocument2 pagesFee ChallanAmeena AimenNo ratings yet

- Islamophobia, Xenophobia and The Climate of Hate: European Race BulletinDocument40 pagesIslamophobia, Xenophobia and The Climate of Hate: European Race BulletinAmeena AimenNo ratings yet

- JMS January June2013 113-125Document13 pagesJMS January June2013 113-125Ameena AimenNo ratings yet

- Dawn VocabularyDocument6 pagesDawn VocabularyAmeena AimenNo ratings yet

- Paragraph Writing BasicsDocument2 pagesParagraph Writing BasicsAmeena AimenNo ratings yet

- ON-Campus Classes (Online During Lockdown)Document2 pagesON-Campus Classes (Online During Lockdown)Ameena AimenNo ratings yet

- International Political Economy.: Theories in IPE: Mercantilism, Economic Liberalism, and MarxismDocument35 pagesInternational Political Economy.: Theories in IPE: Mercantilism, Economic Liberalism, and MarxismAmeena AimenNo ratings yet

- 10 Sep 2021Document1 page10 Sep 2021Ameena AimenNo ratings yet

- Middle East CrisisDocument12 pagesMiddle East CrisisAmeena AimenNo ratings yet

- Free Online Course On PLS-SEM Using SmartPLS 3.0 - Moderator and MGADocument31 pagesFree Online Course On PLS-SEM Using SmartPLS 3.0 - Moderator and MGAAmit AgrawalNo ratings yet

- Canara BankDocument21 pagesCanara BankRajesh MaityNo ratings yet

- If ملخص قواعدDocument2 pagesIf ملخص قواعدAhmed GaninyNo ratings yet

- DMPB 9015 e Rev4Document109 pagesDMPB 9015 e Rev4mohammad hazbehzadNo ratings yet

- Print - Udyam Registration CertificateDocument2 pagesPrint - Udyam Registration CertificatesahityaasthaNo ratings yet

- DS Masteri An PhuDocument174 pagesDS Masteri An PhuPhong PhuNo ratings yet

- Week 1 - The Swamp LessonDocument2 pagesWeek 1 - The Swamp LessonEccentricEdwardsNo ratings yet

- Roger Dale Stafford, Sr. v. Ron Ward, Warden, Oklahoma State Penitentiary at McAlester Oklahoma Drew Edmondson, Attorney General of Oklahoma, 59 F.3d 1025, 10th Cir. (1995)Document6 pagesRoger Dale Stafford, Sr. v. Ron Ward, Warden, Oklahoma State Penitentiary at McAlester Oklahoma Drew Edmondson, Attorney General of Oklahoma, 59 F.3d 1025, 10th Cir. (1995)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Study Session8Document1 pageStudy Session8MOSESNo ratings yet

- Security and Privacy Issues: A Survey On Fintech: (Kg71231W, Mqiu, Xs43599N) @pace - EduDocument12 pagesSecurity and Privacy Issues: A Survey On Fintech: (Kg71231W, Mqiu, Xs43599N) @pace - EduthebestNo ratings yet

- Drill #1 With RationaleDocument12 pagesDrill #1 With RationaleRellie CastroNo ratings yet

- What Love Is ThisDocument2 pagesWhat Love Is Thisapi-3700222No ratings yet

- Stones Unit 2bDocument11 pagesStones Unit 2bJamal Al-deenNo ratings yet

- SBC Code 301Document360 pagesSBC Code 301mennnamohsen81No ratings yet

- Analysis of Old Trends in Indian Wine-Making and Need of Expert System in Wine-MakingDocument10 pagesAnalysis of Old Trends in Indian Wine-Making and Need of Expert System in Wine-MakingIJRASETPublicationsNo ratings yet

- NT Organic FarmingDocument17 pagesNT Organic FarmingSai Punith Reddy100% (1)

- How To Cook Pork AdoboDocument3 pagesHow To Cook Pork AdoboJennyRoseVelascoNo ratings yet

- DoomsdayDocument29 pagesDoomsdayAsmita RoyNo ratings yet

- Weekly Home Learning Plan: Grade Section Quarter Week Inclusive DateDocument3 pagesWeekly Home Learning Plan: Grade Section Quarter Week Inclusive DateMarvin Yebes ArceNo ratings yet

- Multiple Choice - JOCDocument14 pagesMultiple Choice - JOCMuriel MahanludNo ratings yet

- PDFDocument86 pagesPDFAnonymous GuMUWwGMNo ratings yet

- EoI DocumentDocument45 pagesEoI Documentudi969No ratings yet

- The Child and Adolescent LearnersDocument12 pagesThe Child and Adolescent LearnersGlen ManatadNo ratings yet

- OX App Suite User Guide English v7.6.0Document180 pagesOX App Suite User Guide English v7.6.0Ranveer SinghNo ratings yet

- Dual-Band Wearable Rectenna For Low-Power RF Energy HarvestingDocument10 pagesDual-Band Wearable Rectenna For Low-Power RF Energy HarvestingbabuNo ratings yet