Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Bohnert, Herbert Gaylord - The Semiotic Status of Commands

Bohnert, Herbert Gaylord - The Semiotic Status of Commands

Uploaded by

Clarice AraujoCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- AIKEN. The Levels of Moral Discourse PDFDocument15 pagesAIKEN. The Levels of Moral Discourse PDFErnesto CastroNo ratings yet

- Dahl - 1957 - The Concept of PowerDocument15 pagesDahl - 1957 - The Concept of Powermiki7555No ratings yet

- Dahl Power 1957Document15 pagesDahl Power 1957api-315452084No ratings yet

- FIORIN, José Luiz. Argumentação. (Argumentation) - São Paulo: Contexto, 2015. 272 PDocument9 pagesFIORIN, José Luiz. Argumentação. (Argumentation) - São Paulo: Contexto, 2015. 272 PEmerson SaraivaNo ratings yet

- Robert Dahl: The Concept of PowerDocument15 pagesRobert Dahl: The Concept of PowerIvica BocevskiNo ratings yet

- Agamograph Drawing TemplateDocument5 pagesAgamograph Drawing TemplateAbinash MallickNo ratings yet

- 9200 Serial Communications Protocol and ION / Modbus Register MapDocument23 pages9200 Serial Communications Protocol and ION / Modbus Register Mapsahil4INDNo ratings yet

- Burke - RetorikaDocument4 pagesBurke - RetorikaFiktivni FikusNo ratings yet

- Two Traditions of Analogy by WILLIAM R. BROWNDocument12 pagesTwo Traditions of Analogy by WILLIAM R. BROWNBalingkangNo ratings yet

- "Is" and "Ought" in Hume's and Kant 'S PhilosophyDocument7 pages"Is" and "Ought" in Hume's and Kant 'S PhilosophyStarcraft2shit 2sNo ratings yet

- Grice Logic&Conversation WJL 1989Document11 pagesGrice Logic&Conversation WJL 1989Sara EldalyNo ratings yet

- Book-Introduction The Five Key Terms of Dramatism (MDesIxD)Document5 pagesBook-Introduction The Five Key Terms of Dramatism (MDesIxD)T CNo ratings yet

- Inferentialism and Its Discontents: 1 Inferentialism (A Brief Overview)Document26 pagesInferentialism and Its Discontents: 1 Inferentialism (A Brief Overview)Nombre FalsoNo ratings yet

- Mind Association, Oxford University Press MindDocument7 pagesMind Association, Oxford University Press MindsupervenienceNo ratings yet

- Brown 1989 PDFDocument12 pagesBrown 1989 PDFpompoNo ratings yet

- Indicative Conditionals StalnakerDocument18 pagesIndicative Conditionals StalnakerSamuel OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Fodor, J. On Knowing What We Would SayDocument16 pagesFodor, J. On Knowing What We Would SayRodolfo van GoodmanNo ratings yet

- Doing What Comes NaturallyDocument8 pagesDoing What Comes NaturallyellysweetyNo ratings yet

- Attitude Reports, Events, and Partial ModelsDocument73 pagesAttitude Reports, Events, and Partial ModelsChandra Sekhar JujjuvarapuNo ratings yet

- Norm and ActionDocument141 pagesNorm and ActionsaironweNo ratings yet

- Putnam, H. Psychological Concepts, Explication, and Ordinary LanguageDocument8 pagesPutnam, H. Psychological Concepts, Explication, and Ordinary LanguageRodolfo van GoodmanNo ratings yet

- Frege-Geach Objection: Mark Van RoojenDocument10 pagesFrege-Geach Objection: Mark Van RoojenmikadikaNo ratings yet

- A Note On Semantic RealismDocument6 pagesA Note On Semantic RealismfranciscoNo ratings yet

- Converstational Postulate RevisitedDocument9 pagesConverstational Postulate RevisitedIoana CatrunaNo ratings yet

- Ennis - 1982 - IDENTIFYING IMPLICIT ASSUMPTIONSDocument26 pagesEnnis - 1982 - IDENTIFYING IMPLICIT ASSUMPTIONSAntonioNo ratings yet

- 4940-Article Text-16293-2-10-20190606 PDFDocument23 pages4940-Article Text-16293-2-10-20190606 PDFMario Daniel QuevedoNo ratings yet

- The Merits of Incoherence: Analytic Philosophy Vol. 59 No. 1 March 2018 Pp. 112-141Document30 pagesThe Merits of Incoherence: Analytic Philosophy Vol. 59 No. 1 March 2018 Pp. 112-141Andrew LiebermannNo ratings yet

- What Is ArgDocument26 pagesWhat Is ArgRodney Takundanashe MandizvidzaNo ratings yet

- The Delphi MethodDocument32 pagesThe Delphi MethodMinh Hong NguyenNo ratings yet

- Nous - 2014 - Fricker - What S The Point of Blame A Paradigm Based ExplanationDocument19 pagesNous - 2014 - Fricker - What S The Point of Blame A Paradigm Based ExplanationGONZALO VELASCO ARIASNo ratings yet

- A New Light On Non-Deductive Argumentation Schemes: Department of Philosophy University of Hamburg GermanyDocument10 pagesA New Light On Non-Deductive Argumentation Schemes: Department of Philosophy University of Hamburg GermanyAli SalehiNo ratings yet

- Symbolic Logic Odysseus Makridis Full ChapterDocument67 pagesSymbolic Logic Odysseus Makridis Full Chapterpaul.kut532100% (8)

- Carnap Rudolf - The Elimination of Metaphysics Through Logical Analysis of LanguageDocument14 pagesCarnap Rudolf - The Elimination of Metaphysics Through Logical Analysis of LanguageEdvardvsNo ratings yet

- Tyler Burge The Content of Pro-AttitudeDocument7 pagesTyler Burge The Content of Pro-AttitudeAran ArslanNo ratings yet

- Hume and The Lockean Background Induction and The Uniformity PrincipleDocument30 pagesHume and The Lockean Background Induction and The Uniformity PrincipleKbkjas JvkndNo ratings yet

- From Beginning To Irony - Self-Reflection in The Arts and SciencesDocument10 pagesFrom Beginning To Irony - Self-Reflection in The Arts and SciencesQ JoniNo ratings yet

- The Social Anatomy of InferenceDocument7 pagesThe Social Anatomy of InferenceOrlandoAlarcónNo ratings yet

- Etchemendy, J. (1983) - The Doctrine of Logic As FormDocument16 pagesEtchemendy, J. (1983) - The Doctrine of Logic As FormY ́ GolonacNo ratings yet

- The Operational Analysis of Psychological Terms - SkinnerDocument20 pagesThe Operational Analysis of Psychological Terms - Skinnerwalterhorn100% (1)

- Springer: Springer Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To SyntheseDocument23 pagesSpringer: Springer Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To SyntheseNayeli Gutiérrez HernándezNo ratings yet

- Reasons: Joshua GertDocument12 pagesReasons: Joshua GertmikadikaNo ratings yet

- The University of Chicago PressDocument18 pagesThe University of Chicago PressHorman DiatoniNo ratings yet

- Associationism PDFDocument16 pagesAssociationism PDFMuNo ratings yet

- CDCM Quotes 09-9-23 ADocument4 pagesCDCM Quotes 09-9-23 ADanielSacilottoNo ratings yet

- (Palgrave Philosophy Today) Odysseus Makridis - Symbolic Logic-Palgrave Macmillan (2022)Document493 pages(Palgrave Philosophy Today) Odysseus Makridis - Symbolic Logic-Palgrave Macmillan (2022)Marios BeddaweNo ratings yet

- Skinner, Q. (1971) On Performing and Explaining Linguistic ActionsDocument22 pagesSkinner, Q. (1971) On Performing and Explaining Linguistic ActionsKostas BizasNo ratings yet

- T H E Journal of Philosophy Psychology and Scientific MethodsDocument9 pagesT H E Journal of Philosophy Psychology and Scientific MethodsLaura Nicoleta BorhanNo ratings yet

- Ricoeur, Paul. Capabilities and RightsDocument10 pagesRicoeur, Paul. Capabilities and Rightshefestos11No ratings yet

- The Concept of Power: Robert DahlDocument15 pagesThe Concept of Power: Robert DahlNada SalihNo ratings yet

- Jurisprudence PaperDocument9 pagesJurisprudence PaperShaikhNo ratings yet

- Car NapDocument21 pagesCar Napmichael_poageNo ratings yet

- Dahl, Concept of Power (A)Document15 pagesDahl, Concept of Power (A)Vladislava RyabovolovaNo ratings yet

- The Metaphorical Process As Cognition, Imagination, Feling - Paul Ricoeur 1978Document18 pagesThe Metaphorical Process As Cognition, Imagination, Feling - Paul Ricoeur 1978CarlosNo ratings yet

- Conceptual Ethics pt1 - Plunkett-Burgess2013Document11 pagesConceptual Ethics pt1 - Plunkett-Burgess2013Tim HardwickNo ratings yet

- Hartmann 1931Document12 pagesHartmann 1931Matheus Pereira CostaNo ratings yet

- Constanze Peres: On Using Metaphors in PhilosophyDocument9 pagesConstanze Peres: On Using Metaphors in PhilosophymayoshtyNo ratings yet

- Logic, Reasoning, Information: June 2015Document17 pagesLogic, Reasoning, Information: June 2015Ubyy UbongNo ratings yet

- Corcoran Hare and Others On The PropositionDocument26 pagesCorcoran Hare and Others On The PropositionGustavo VilarNo ratings yet

- Some Sub-Atomic Particles of Logic: R. M. HareDocument15 pagesSome Sub-Atomic Particles of Logic: R. M. HareDaniele ChiffiNo ratings yet

- KANTDocument6 pagesKANTPal GuptaNo ratings yet

- Tent A 021220Document9 pagesTent A 021220jkgoyalNo ratings yet

- Dynamic Economic Dispatch Using Model Predictive Control AlgorithmDocument7 pagesDynamic Economic Dispatch Using Model Predictive Control Algorithmselaroth168No ratings yet

- Confidential: Final Examination Semester Ii SESSION 2014/2015 (Solution)Document13 pagesConfidential: Final Examination Semester Ii SESSION 2014/2015 (Solution)marwanNo ratings yet

- Perimeter and Area Lesson Plan McdanielDocument3 pagesPerimeter and Area Lesson Plan Mcdanielapi-242825904No ratings yet

- MGT214 - Chapter 11 Investment Decision CriteriaDocument16 pagesMGT214 - Chapter 11 Investment Decision CriteriaPatty VirayNo ratings yet

- SP47Document177 pagesSP47Venkata Bhaskar DameraNo ratings yet

- Koos Scoring 2012Document3 pagesKoos Scoring 2012rythm_21No ratings yet

- Cot Act. 6Document7 pagesCot Act. 6FRECY MARZANNo ratings yet

- 18CS55 ADP Notes Module 4 and 5Document72 pages18CS55 ADP Notes Module 4 and 5Palguni DS100% (1)

- LPP SimplexDocument107 pagesLPP SimplexAynalemNo ratings yet

- Extreme Values and Saddle PointsDocument35 pagesExtreme Values and Saddle PointsGeorge SimmonsNo ratings yet

- Tablet Press ModelDocument22 pagesTablet Press Modelmarcelo100% (2)

- IE2152 Statistics For Industrial Engineers Problem Solving SessionsDocument57 pagesIE2152 Statistics For Industrial Engineers Problem Solving SessionsKutay ArslanNo ratings yet

- Graphics in PHPDocument31 pagesGraphics in PHPVivekNo ratings yet

- Sets and Venn DiagramsDocument9 pagesSets and Venn DiagramsDominic SavioNo ratings yet

- Number System: Amity School of Engineering and TechnologyDocument103 pagesNumber System: Amity School of Engineering and TechnologyAkanksha ThakurNo ratings yet

- Iv-Day 16Document3 pagesIv-Day 16Florita LagramaNo ratings yet

- Cobol Performance TuningDocument55 pagesCobol Performance TuningApril MartinezNo ratings yet

- Pile Foundation - PresentationDocument39 pagesPile Foundation - PresentationJimmy KalumataNo ratings yet

- DLL-2nd-week 7-12Document6 pagesDLL-2nd-week 7-12cathline austriaNo ratings yet

- Gymnasium Sound Control Solutions: Product OptionsDocument1 pageGymnasium Sound Control Solutions: Product OptionsRenzon SisonNo ratings yet

- Interactive Simulation of Power Systems Etap Applications and TeDocument12 pagesInteractive Simulation of Power Systems Etap Applications and TeMuhammad ShahzaibNo ratings yet

- Phy Maths Integration-Final2 PDFDocument62 pagesPhy Maths Integration-Final2 PDFSimran GuptaNo ratings yet

- Unit V Fourier Transform PDFDocument53 pagesUnit V Fourier Transform PDFRahul JRNo ratings yet

- Precision Rectifiers: Elliott Sound ProductsDocument12 pagesPrecision Rectifiers: Elliott Sound ProductsDRAGAN ANDRICNo ratings yet

- Iso 1328-Agma - Parte 1Document35 pagesIso 1328-Agma - Parte 1bernaldoarnaoNo ratings yet

- Longitudinal Vibration of A Bar ": Presentation OnDocument17 pagesLongitudinal Vibration of A Bar ": Presentation OnamitpatelNo ratings yet

- EE462 Design of Digital Control Systems PDFDocument2 pagesEE462 Design of Digital Control Systems PDFArya RahulNo ratings yet

Bohnert, Herbert Gaylord - The Semiotic Status of Commands

Bohnert, Herbert Gaylord - The Semiotic Status of Commands

Uploaded by

Clarice AraujoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Bohnert, Herbert Gaylord - The Semiotic Status of Commands

Bohnert, Herbert Gaylord - The Semiotic Status of Commands

Uploaded by

Clarice AraujoCopyright:

Available Formats

THE SEMIOTIC STATUS OF COMMANDS

HERBERT GAYLORD BOHNERT

THE PROBLEM

The large number of writers who have in recent years' attacked the problem

of the logical nature of commands appear generally in agreement in accepting

the distinction of common grammar between imperative and declarative sen-

tences as representing, albeit in no clear one-to-one manner, some real differ-

ence in the logical character of the two types of expression, and possibly in the

psychological sign-functioning mechanism itself. The crucial logical difference

adduced is that commands can apparently rot be classified as true or false.

One is then, however, confronted with the problem of interpreting arguments

involving imperatives which appear syllogistic in form, such as:

Keep your promises!

You promised to pay on Wednesday.

Pay on Wednesday!

To this end it is usually assumed that the specifically imperative element

of the command is never utilized in derivations, that it is only its referential

content, the act commanded (variously called by different writers "theme of

demand", "indicative factor", "logical element", "gerundive", etc.) that is

involved. Occasionally an indicative sentence about the state of the speaker

or hearer is offered as the translation. A number of different schemes of corre-

lating indicative sentences representing this referential content or psychological

state with the command, sometimes adding extra restrictive rules to derivations

involving such representative sentences, have been developed. These will be

discussed in the body of the paper. As for the imperative element, its presence

is frequently taken to place the expression in a class with, say, growls and

frowns, gestures evincing feelings but not referring to them, which in turn are

regarded as representative of an entirely different "dimension" of semiosis-the

"motivational" dimension. This notion is then sometimes extended by calling

all declarative sentences which are sufficiently motivational, such as value

statements, "disguised commands". Since commands are considered incapable

of being true or false, this leads to the conclusion that value statements, or at

least some of them, are outside the realm of science-a position which has

unfortunately been capitalized on, and abused by, many basically anti-scientific

philosophies and educational theories. The interpretation of statutory com-

mands, instructional commands, technological commands, commands such as

"Keep this car properly lubricated!" is also rather complicated by the "growl

theory" of imperatives, since it assumes an emotional state of the speaker of

the commands, or at very least a personal will that the command be obeyed,

which differs in some respects from the mere desire that a communication be

See bibliography.

302

This content downloaded from 201.081.210.097 on September 05, 2016 14:24:44 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

SEMIOTIC STATUS OF COMMANDS 303

taken account of, felt by the utterer of a purely declarative sentence. It as-

sumes, in other words, that for there to be an imperative, there must be an

imperator, in some different sense than a declarative sentence requires a declaror,

possibly that the imperator personally enforce or desire to enforce the command.

This is hard to believe with regard to the example given, which appears prac-

tically translatable into the declarative "Either this car is properly lubricated

or it won't run."

PROGRAM OF PAPER

The present paper will endeavor to render plausible quite different conclu-

sions from those sketched above, taking the cue offered by the above example.

First, by means of a rough empirical discussion, it will be argued that all sen-

tences are at least potentially motivational and that although motivational

situations causally give rise to the command form, the command need not say

or assume anything about the desires or fears of the hearer or the speaker;

that motivation by itself does not jeopardize truth value; that in a behavioral

sense commands function as, i.e. are, declarative sentences; that the imperative

factor can also play a role in derivation; that such derivations are genuine

derivations, (not merely pseudo-logical). The attendant psychological phe-

nomena that appear to set commands so apart from declarative sentences will

be "explained" by plausible socio-psychological hypotheses which will serve as

sketches of how real explanations might be sought. Second, a more formal

analysis will then abstract from the empirically "discovered" properties of

commands, and a simpler system of definitions through which to reduce im-

perative reasonings to declarative logic, and which will satisfy or dispel Ross'

criticisms of previous imperative logics will be offered. (The suggested system

may be acceptable as a sufficient interpretation of natural commands even if

not a necessary one, i.e. even if the empirical account given is rejected.) Finally,

the bearing of these conclusions upon certain ethical theories will be discussed.

MOTIVATION

First let us observe that most motivation of animals and men occurs without

the help of uttered signs at all. Living organisms are motivated ultimately by

situations and situations are designated by declarativesentences. They are moti-

vated characteristically (except for involuntary and reflex action) by situations

which promise or threaten to have physiological or psychological consequences

of greater or less desirability than those possible if the individual's behavior

causally intervenes. This suggests that all situations, and hence the sentences

designating them, are at least potentially motivational. Indeed why else do

we acquire knowledge? This description of motivation might be put more

formally and perhaps apparently rationalistically as:

A situation M motivates a behavior B of x only if x believes M and x

can derive from M with the help of other personally believed sentences

"PvB(x)", but not "P" alone, where P is some future situation of directly

unpleasant character.

This content downloaded from 201.081.210.097 on September 05, 2016 14:24:44 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

304 HERBERT GAYLORD BOHNERT

This is of course a weakest form; x would be motivated even more strongly

by "-,P e B(x)" or "B(x):D-~P" and possibly other forms. If P is the non-

attainment of some desired end E, the disjunction becomes ""-EvB(x)" or

"EDB(x)", a frequent form of technological sentence, B being one of a chain

of necessary behaviors to the attainment of E. More fully developed, such a

statement should be made in the form of an equation or an inequality involving

degrees of motivation, degree of belief and the probabilities of the various

sentences and sub-sentences, in which form it would constitute a suggested

program for psychological research but would serve no better in the present

context than the crude qualitative statement given. Indeed, the predicates

used may be considered as defined as holding if the corresponding functions are

in sufficiently high ranges. As for the apparent rationalism of the phrase "can

derive with the help of other . . . sentences", it is not intended to imply that

explicit derivations are ever actually made in the course of being motivated,

but it is a reference to the essential fact that whenever one tries to communicate

one's reasons for a certain behavior he does make or try to make some such

derivation, thereby suggesting that some psychological process in some way

similar to such a derivation really did occur. It is a situation similar to that

discussed in H. Reichenbach's excellent treatment of epistemological logic as

being in the "context of justification" rather than in the "context of discovery".

Note that the one-way implication expressed in "only if" leaves open the prob-

ably desirable possibility of defining "motivates" in such a manner that M

motivates only if apprehension, recall, or realization of M itself is the actual

initiator of the motivated behavior. Also, it allows the postulation of other

conditions (physiological, for example) as also necessary to actual motivation.

PvB(x) will be called the motivating disjunction, M the motivator,B the appro-

priate reaction, and P the penalty. (Identical terminology will be applied to

the expressions designating these entities when no confusion can result. More-

over object and metalanguage will frequently be deliberately mixed in the fol-

lowing to avoid wordiness.) "You run or you burn" is the crucially moti-

vating consequence of "The house is on fire." If one knows additional premisses,

among which might be, for example, "My side of the house is expertly fire-

proofed", with the help of which one can derive "I neither run nor burn", no

direct motivation ensues; or, if, due to some other premiss, no such disjunction

is derivable without "I burn" being derivable independently, then again no

motivation (except of random, involuntary behavior) results. The sentence

"The house is on fire" is then simply a sentence of doom.

ORIGIN OF THE COMMAND FORM IN MOTIVATION SITUATIONS

In speech some very simple rules would seem to govern the utterance and

combination of utterance of the various members of the motivation sentence-

ensemble. In not very urgent situations in which the inference from motivator

to motivating disjunction is very apparent, the motivator will probably be

stated alone as a plain, indicative sentence; "Your shirt tail is hanging out"

As the connecting inference becomes more and more obscure or complicated

This content downloaded from 201.081.210.097 on September 05, 2016 14:24:44 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

SEMIOTIC STATUS OF COMMANDS 305

the appropriate reaction will increasingly tend to be mentioned, usually to-

gether with the motivator (unless the motivator is definitely apparent to the

hearer) connected to it by some metalinguistic or intensional term such as

"hence", "thus", "so", etc., designating an intervening derivation. The

penalty is usually not mentioned since mention of the appropriate reaction

usually makes clear what penalty would attend non-execution of the appro-

priate reaction. The connecting inference, however, connects the motivator

to the disjunction, not the motivator to the appropriate reaction alone, and

hence a grammatical form showing that half a disjunction is missing is required

for the expression of the appropriate reaction if the above intensional or

metalinguistic terms are to retain their normal meaning. It will be held that

the command form does indeed fulfill this function. Consider the following

examples. "Miss Seward will be there, so don't mention Matisse." Here a

number of inferences could presumably be drawn with the help of the motivator

so that the entire command is made to point out one particular one. The

penalty is presumed to be understood so only the appropriate reaction is men-

tioned. "Don't be too casual about using sulfa drugs because they frequently

have toxic effects." Here the penalty is just a "specification" of the motivator.

The appropriate reaction is obvious but the lack of urgency of the situation

permits it to be mentioned. It is a probable hypothesis that the truncated

form for the expression of the appropriate reaction has evolved due to the

conditions of urgency that frequently attend the use of imperatives. As urgency

increases the motivator will tend not to be mentioned at all and only the appro-

priate reaction will be uttered, in typical command form. Under conditions of

urgency all sentences tend to become as short as possible. E.g. "The house is on

fire!" becomes "Fire!", and without losing its functional quality of being true

or false, although like the parent sentence itself, it does not strictly designate

a proposition in the sense that independent of all verbal context it would be

confirmable as true or false. That is, it is an ellipsis. A command is here re-

garded as simply the more serious ellipsis of omitting the entire penalty clause

of the described class of disjunctions, again without sacrificing the truth rules

of a disjunction, which, however, remain, clear, of course, only if the penalty is

understood. "Run!", then is permitted to be considered true if the exhorted

one stays and burns, where the indicative, "You run" would be false.

The foregoing rules of utterance may be suggestively conveyed by saying

that as a monotone increasing function of the two arguments, urgency and

degree of uncertainty as to appropriate reaction, the behavior to be motivated

will first, for low values of the two arguments, tend not to be mentioned, then

will be mentioned along with the motivator, and finally, for high values of both

arguments, it will be mentioned alone, (especially since in urgent situations the

motivator is usually all too evident, or there is not enough time to call attention

to it, e.g. an approaching car). The precise psychological and logical formula-

tion of such a sentence presents, of course, vast difficulties.

Let us note that in the command "Run!", interpreted as "You run or you

burn", the penalty is inflicted by no person but by a condition of the hearer's

This content downloaded from 201.081.210.097 on September 05, 2016 14:24:44 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

306 HERBERT GAYLORD BOHNERT

non-human environment. It would be equally motivational no matter who

uttered it, a child in the street for example, as long as the hearer took it seri-

ously, or even, in this case, since the consequence is obvious, if the motivator

alone were mentioned. There is no enforcing or spontaneously willing

imperator-a condition frequently mentioned as necessary to and characteristic

of all imperatives, as mentioned earlier. It is easily seen that this situation is

common to a great number of commands, technological commands, medical

commands, etc. Commands which are thus self-enforcing will be called im-

personal commands,the other type, personal commands. In personal commands,

and commands in which the enforcer is neither the non-human environment

nor the speaker but a social institution, namely, directives, laws, orders, it will

be noticed that motivator perceived by the hearer is generally identical with

the motivating disjunction itself. The "growl theory" would appear applica-

ble, if at all, only to personal commands and hence not be an adequate account

of commands in general. The "imperative element" is seen to be simply the

unspoken penalty, and to have no necessary connection with the imperator's

feelings. As such, it is obvious how the "imperative element" can play just as

important a role in imperative derivations as the "indicative factor". For

example:

Keep this car properly lubricated!

I will not lubricate this car.

Then the car will soon break down.

The apparently non-logical nature of this inference, which is, however, a

type very commonly occurring in daily life, arises from the fact that an ellipsis

is given as one of the premisses, namely the imperative, understood as "Either

this car is properly lubricated or it will soon break down". Of course, for an

ellipsis to appear in a derivation its missing parts must be presumed to be under-

stood.

FUNCTIONAL ISOMORPHISM OF COMMANDS AND CERTAIN DECLARATIVE

SENTENCES

Having presented a plausible account of how commands may functionally

have origin in declarative sentences, what sort of evidence must be presented

to confirm that behaviorally they are declarative sentences? It is submitted

that the empirical content of such a sentence be provisionally defined as equiva-

lent to the statement that there exists a set of grammatically declarative sen-

tences which can be put in one-to-one correspondence with commands andsuch

that the truth value attributed to the correlated declarative by any hearer,

x, is a significant argument in the function, Behavior of x. Just as if we were

studying a strange tribe, we would not feel that we understood their language

unless we could biuniquely correlate with their speech-forms English sentences

which, judging by the natives' behavior, corresponded also in truth rules. The

criteria involved in such analysis of behavior would, of course, be extremely

involved and would require a close general analysis of purposiveness in animal

This content downloaded from 201.081.210.097 on September 05, 2016 14:24:44 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

SEMIOTIC STATUS OF COMMANDS 307

behavior. Furthermore, the scientific confirmation of the above sentence

concerning commands, even when correctly formulated, would require a large

and difficult experimental undertaking. Under these difficult circumstances,

the author will be forced to rely on the reader's common-sense generalizations

concerning behavior and offer examples which must rely for their weight on

common-sense plausibility.

Consider the broadcast command "Shop at Mandel Brothers!" (an impersonal

command since the unpleasant alternative-missing all the presumed bargains,

excellence of goods, etc.-would not be inflicted by Mandel Brothers) and the

personal command, "Go to bed!" If from past experience, the respective

hearers attribute a high probability (in Carnap's sense of high confirmation)

to the sentences "I shall neither shop at Mandel's nor miss bargains", and "I

shall not go to bed and my father will not punish me" (assuming these to be the

understood unmentioned penalties), then the commands are disobeyed. As

suggested by the phrase "significant argument" in the above sentence pro-

visionally defining (behavioral) declarative sentence, the assertion is not in-

tended that obedience is a function of the believed truth value of the disjunc-

tion alone, or that obedience is the only type of behavior which is a function of

the believed truth value. The penalty may not be feared at all, or the desire

for an action requiring disobedience of the command may outweigh the dis-

pleasure of the penalty. That is, refraining from the appropriate reaction

may be the appropriate reaction in another command involving a greater

penalty. For example, the radio listener may deliberately miss bargains to

attend a movie, and martyrs may suffer torture and death for the hoped-for

ecstasies of salvation. Also, if one alternative be conducive to immediate

short-run happiness and the other to long-run happiness but with poorer im-

mediate prospects, the behavior will depend upon "morale", personal history,

etc. Moreover, a command may be disobeyed even when it is believed and the

penalty feared more than any competing value is desired if it is further believed

that the appropriate reaction and penalty have no causal relation to each other

(an example of this situation is given further on under Causal Relations). It

is asserted, however, that the believed truth value is an important argument in

the function, Total Behavior of x, one whose value must be determined if one

is to predict the measure of obedience or type of disobedience, and that such a

relation to prediction is sufficient for empirical meaningfulness, since, if fully

stated, it would constitute at least a unilateral reduction sentence (in the sense

given to this phrase in Carnap's Testability and Meaning).

PSYCHOLOGICAL IMPERATIVENESS OF COMMANDS

It is frequently objected that translation into the grammatical form of declara-

tive sentences robs commands of their unique, psychologically imperative

character. Although in general true, this is only what must be expected in the

light of the suggested rule that a disjunction is truncated into a command

usually under conditions of urgency. Humans are, therefore, so conditioned

that a command has a tendency to bring about a quick response before much

This content downloaded from 201.081.210.097 on September 05, 2016 14:24:44 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

308 HERBERT GAYLORD BOHNERT

speculation as to its truth can take place. Furthermore, the conditioning may

have proceeded to the point where the reaction to small commands is com-

pletely automatic and subconscious, with no question of truth appearing.

However, one may be confident that in such a case if one were to command

something a bit more onerous the hearer's reaction would quickly became again

a function of how he evaluated the coercive potentialities of the penalty implied

by the command. The truth of the objection, then, does not rob the command

of its truth value, if it is understood that no actual translation is proposed but

only an isomorphism as to truth-values pointed out. On the other hand, a

further example may show that such translation need not always lessen a com-

mand's imperative effect, and that such translation is frequently quite consciously

in mind when a command is made. In a recent war film a Nazi official was

pictured as bawling fierce commands at the population of a Norwegian mining

town to cease a slow-down strike in the mines. Finally, greeted by complete

impassivity, he declared in impressive, deliberate tones, "Either the strike

ceases or no one in this town will eat."

THE FORMAL PROPERTIES OF COMMANDS

It has been urged throughout the foregoing that commands might be regarded

as ellipses for declarative sentences, the sentence usually correlated being a

disjunction with various properties, many pragmatic, some semantic. It will

now be investigated which of these properties are the essential ones and whether

the disjunction is the only type of declarative sentence correlatable. A number

of more formal difficulties which have not yet been mentioned will then be seen

to arise and will be discussed.

EFFECTIVENESS

It has already been pointed out that psychological imperativeness due to

peremptoriness of the voice and the urgency suggested by the command form

itself are no more necessary to the definition of "command" than the aloof

persuasive power of a sentence of mathematics is to that of "sentence of mathe-

matics". Another type of psychological imperativeness, however,-that due

to the fact that the understood "penalty" is a penalty-is a little more basically

characteristic of the commands actually occurring. This is seen in the occa-

sionally suggested translation of commands as "If you desire p then you must

act so that q" (which is, of course, a total begging of the question since the word

"must" appears; the real command being the assertion that p causally requires

q, whether or not p is desired, the apparent conditionality of the command

lying in the belief that if the hearer desires p then he will be motivated by this

information). To require this type of imperativeness (i.e. that the penalty

shall actually be feared), which will here be called effectiveness,as part of the

definition makes a possible psychological theory of the effectiveness of com-

mands awkward since by definition all commands are effective. Certainly it

appears more convenient to regard an expression such as "Don't shoot!",

understood through context as "Either you don't shoot or I shall suffer", ad-

This content downloaded from 201.081.210.097 on September 05, 2016 14:24:44 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

SEMIOTIC STATUS OF COMMANDS 309

dressed to a seasoned triggerman, as a command even though an ineffective one.

Once we raise this restriction we of course open the door to commands whose

penalties are, say, "2 + 2 = 4", but certainly the assertion of a command on

such a basis is a subject for psychological investigation, not logical. Commands

certainly are made in real life in which the penalty is just as little feared. The

variations of request and appeal forms mirror varying strengths of underlying

penalties down to practically zero strength, many requiring strong hearer

sympathy or altruism to be effective at all. If the speaker does usually make

the assumption that the penalty is feared, this is only analogous to the fact

that the speaker of a declarative sentence usually assumes interest on the part

of the hearer, i.e. believes that the sentence is appropriate or relevant.

The fact that a penalty will be feared by some and not by others establishes

a relativity of commands entirely analogous-identical if value statements are

held to be commands-to the "relativity of values". In both cases the state-

ment of what the fears or interests of an individual are and which behaviorally

supersede which may be quite external to the logical content of the command

or value statement (though certainly not outside the province of science, e.g.

psychology).

APPROPRIATE REACTION

In all examples given up to now the alternative of the penalty has been a

behavior of the hearer, the cue for this being taken from the original statement

as to what type of situation motivates. This suggests quite a strong empirical

limitation to our formation rules for commands. However, this is quite un-

necessary since just as the motivator, perhaps a simple declarative sentence

such as "The house is on fire", can motivate, so a disjunction can motivate in

which the proposition commanded to be the case is within the power of the

hearer to effectuate, and the alternative, a future situation which he dislikes,

for example, "This table must be painted today!" understood as "Either the

table is painted today or the party will not be held." Such a command in which

the behavior of no particular person is mentioned will be called a fiat, otherwise

a directive, for it is just this distinction the author believes Hofstadter and

McKinsey to have had inexplicitly in mind when introducing these words.

Their example, "Let there be light!", is then here understood to be an inde-

terminate ellipsis lacking a clear truth value not because it is a command but

just for the same reason that "The house is on fire" printed alone on a page with

no context lacks it, i.e. insufficient information is given for the expression to

determinately designate a proposition. If it is understood as "Either there is

light or John will leave" where the particular individual and time index is

understood, it acquires perfectly clear truth rules. What God meant by the

command is for the theologian to explain, not the logician. A final example:

"Shine on, Harvest Moon!" interpreted from the song context as "Either the

moon continues to shine or 'I don't get no lovin'' " is, according to the termi-

nology here employed, an ineffective fiat even though the moon does in fact

continue to shine, (assuming "person" to mean "living organism"-otherwise

This content downloaded from 201.081.210.097 on September 05, 2016 14:24:44 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

310 HERBERT GAYLORD BOHNERT

the probably trivial distinction between fiat and directive breaks down entirely,

since any natural phenomenon can be addressed as a person).

TEMPORAL RELATIONS

Another peculiarity of commands is that the implied time indices of both

members of the disjunction are usually future to the time of communication.

This is the case because the purpose of the commander is usually to motivate

the hearer, and motivation, according to the statement given in the earlier part

of this paper, requires these time relations. However, if, in reading ancient

history, we come across the expression, "Crush Carthage!" and if we understand

this to mean from context, "Either Carthage is crushed or the Roman Empire

will be eclipsed by Carthage", we certainly would want to call it a command

even though the time indices intended by the speaker are far in the past. We

simply may state as a matter of psychology that such commands do not moti-

vate. If it is held, then, that commands when rendered free of ellipsis designate

propositions in the sense that they are true or false for all time, then no specifica-

tion of necessary time relations can be made, and this again permits a large

number of anomalous commands like "Leave for New York yesterday!", the

restrictions against which, however, may be considered to be practical rather

than logical.

CAUSAL RELATIONS

Another word prominent in the description of motivation and in the dis-

cussion of many of the past examples is "causal". A technological command,

"B(x)!" meaning "-EvB(x)", say, is made and obeyed in the belief that its

transform, "EDB(x)" states that B(x) is a causally necessary condition for the

holding of the end E. A person may disobey the command, "Stop!", understood

through context as, "You stop or I shoot" even though he believes the dis-

junction quite true but believes also that he will be shot anyway, or, more

generally, that there is no causal relation at all between his stopping and being

shot. It was this situation which was intended to be covered in the description

of the motivation situation by the condition that x should not be able to (inde-

pendently) derive the penalty from his believed sentences. But what is pre-

cisely meant here by "derive" is difficult to say since there seem to be some

probability notions involved. Also, the author feels that it is really some

subset of the believed sentences that should be specified but is at a loss at present

to characterize it. The difficulty, however, is not peculiar to commands but

is a general logical problem. When one uses the words "If . . .then . .." in

English he usually means to assert a causal connection, in fact one frequently

repudiates a sentence of the type, "If A then B" without intending to assert

"~A.B" but rather that -A.B is possible. However, the interpretation is

not, it must be repeated, a problem of imperative logic. This point will be

returned to in the discussion of Ross' criticisms of the system of Hostadter and

McKinsey.

This content downloaded from 201.081.210.097 on September 05, 2016 14:24:44 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

SEMIOTIC STATUS OF COMMANDS 311

DISJUNCTIVE ELLIPSIS

We have, then, in order to include all expressions that we want to call com-

mands, reduced the definitional requirements to those of the disjunctive form

itself. That is, we have arrived at the point where we might try to define an

imperative operator as follows:

p!=pvq with the stipulation that q is understood.

What is the logical status, however, of the words in English following the formula?

Ellipses in- natural language are fleeting things. The same command can be

given in a number of different circumstances, each time with a different penalty

understood, just as "The house is on fire" can be uttered a hundred times in

the United States in one day, each time with a different house referred to.

Now every time "The house. . ." is used elliptically, we can imagine the sentence

as part of a sublanguage for which it is specified metalinguistically that "The

house" refers to a house defined by a definite description, i.e. by an expression

containing an iota operator. In any formal communication, such as a contract

or will, precise specifications serving this purpose are indeed given. Likewise,

therefore, to define "p!" we must consider it as part of a system of commands

all employing the same penalty or set of penalties so that in that sublanguage

we define,

p! =pvA,

"A" being an actually stated sentence of the object language. This procedure

is, in effect, followed in the statement of laws, where a penalty is specified for

a whole class of crimes, or in a statement of delegation of powers in an industrial

plant, for example, which may be regarded as the statement that all of a certain

officer's commands in such and such fields of activity have such and such penal-

ties behind them. The basic legal documents of any social institution may be

regarded as providing a very complex meaning-giving reference system for the

commands of its officers.

A further extension of the notion of a command has been implicit in much of

what has been said here, namely that the time, place and person names (or

whatever other type of zero level specification is used) may be replaced by

variables and a universal or existential command asserted, e.g. "No one must

steal!", "Keep (all of) your promises!", "Someone had better call the police!"

The disjunction form is, however, still characteristic of the matrix of these

generalized sentences in the minimal sense that although more complicated

molecular sentences may be understood their "normal form" contains at least

one disjunction.

THE SYSTEM OF HOFSTADTER AND MCKINSEY

If we restrict ourselves to one imperative reference system, i.e. a system in

which all commands are enforced by the same penalty, P, it is significant that

with our interDretation of commands as disjunctions, it is possible to give an

This content downloaded from 201.081.210.097 on September 05, 2016 14:24:44 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

312 HERBERT GAYLORD BOHNERT

interpretation to the Hofstadter and McKinsey system which will render it

analytic, i.e. will make their language Ic identical with I, without involving the

triviality that Alf Ross charges this system with, and without requiring their

own satisfaction functional interpretation of it.

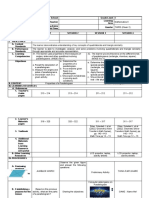

Let us treat P as a propositional constant and make the following definitions:

Definiendum Definiens

iS SVP

IS --S V P

+ V

S1 - S2 S1 : (S2 V P)

S1 > !S2 (SiV P).(S1 >)S2)

It may be easily shown that with this interpretation all primitive sentences

of I, become theorems of primitive sentences of I. The uneasiness one intuitively

feels in seeing, for example, !Si + !S2= !(SIvS2), comes, the author suspects,

from the fact that commands independently stated in natural situations usually

have different penalties, so that each operator appearing in the formula seems

to require a different reference system.

ALF ROSS' OBJECTIONS

The Triviality of the Hofstadter and McKinsey System. With the above

interpretation the operator, !, does indeed become superfluous as Ross suspected,

but not in the way he expected. To quote him: "According to that (Hofstadter

and McKinsey's) interpretation the imperative element has been completely

segregated. The logical element refers solely to the fulfillment of the

demand.... It is not strange that Hofstadter and McKinsey should arriveat

the result that S1 implies !S2or Ii, and that the special mark of the imperative !

is therefore, strictly speaking, superfluous." We have seen, however, that it is

not this fact which renders it superfluous for it is not the case, in general, that

!SilDS, since this is held to be equivalent to (S1vP)DS1. According to our

interpretation, moreover, the imperative element is not "segregated" and the

satisfaction-functional interpretation is not the important one, although of

course commands so interpreted will, in fact, be satisfaction-functional. The

fact that "The door is closed" implies "Close the door!" sounds strange is due

to the fact that such a derivation is hardly ever used, just as it is the case that

if one knows that the door is closed he does not announce the perfectly correct

inference "Either the door is closed or a unicorn is just outside."

Negation. Ross points out that there appear to be two types of negation

with respect to commands. "Close the door!" may be regarded as negated

by either "Don't close the door!" or "It is not your duty to close the door".

One is a contrary command; the other is the denial of the imperativeness of the

command. The first corresponds to !S or -SvP, whereas the second, inter-

pretable also as "Never mind closing the door", appears to be a descriptive,

This content downloaded from 201.081.210.097 on September 05, 2016 14:24:44 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

SEMIOTIC STATUS OF COMMANDS 313

pragmatic, metalinguistic rescindmentof the command, equivalent to the denial

of Russell's "-" sign, that is, the assertion that "SvP" is not asserted. Actually

with the present interpretation there are two other types of repudiation of a

command-the statement ",.P", that is, that there will be no punishment

whatever behavior is taken by the hearer, and --(SvP). The distinguishing

and interpretation of these types of negation present no logical difficulty. It is

sufficient to point out in any context which is meant.

Disjunction. Ross objects that from "Post this letter!" we should not be

able to derive "Post this letter or burn it!" as the Hofstadter and McKinsey

system allows. This seems to return us to the question of causality. When

we assert that the letter is either posted or x is reprimanded, we mean that

posting the letter is a causally necessary (perhaps also sufficient in this case)

condition for avoiding a reprimand. To add an alternative which has perhaps

no or negative causal relation to the avoidance of the reprimand appears to.

pervert imperative meaning, for when we deliberately assert a disjunctive

command, say, "Lubricate this car with / 3 or / 4 type oil!" we mean the whole

disjunction to be a causally necessary condition for the car's proper operation,

not merely one of its members. This objection can, however, be met by noticing

that just as people who know A seldom derive from it AvB, which has less logical

content than A, so a person who is informed of a disjunction in the command

form is not going to behave on less than the total information available by

deriving from it a sentence with an additional alternative and acting onthat.

Indeed, to derive such a super-membered command and then believe that the

additional alternatives have some possibility of replacing the given alternative

in some causal chain sufficient to the avoidance of the penalty would be to

derive much more than was logically contained in the original command.

Implication. Ross objects that in the Hofstadter and McKinsey system

one can construct the following derivation.

Love yourself!

Love your neighbor as yourself!

. Love your neighbor!

But, he states, the second premiss says to love your neighbor as you actually

love yourself, i.e. possibly not at all, and that hence the conclusion does not

follow. The author can only bluntly say that he feels the concluding command

to follow from the conjunction of the two preceding commands (i.e. admittedly

not from the second alone) and that it is provable in the penalty interpretation

of commands. Ross admits that similar examples occur in Rose Rand, Grelling,

J0rgenson, and Grue-Sorenson and that these authors appear to regard this

type of inference as a typical natural imperative inference.

ETHICAL COMMANDS

In view of the position, popular among logicians and empiricists, as to the

ungroundability of ethical commands and those value statements conceived

This content downloaded from 201.081.210.097 on September 05, 2016 14:24:44 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

314 HERBERT GAYLORD BOHNERT

to be commands outlined in the earlier part of this paper, many will hesitate

to accept the position here put forward because it might seem to give cognitive

standing to these commands. However, if ethical commands are considered

to be categorical imperatives, the present interpretation offers just as little

comfort to the transcendental moralist as the more sweeping rejection on the

basis of their being commands, since from the present point of view they appear

to be simply uncritical hypostatizations of an incomplete language form. If

the penalty be given as "or you will be doing evil", it depends on the definition

of "evil" whether the command is to be regarded as metaphysical, L-true or

factual. It would seem no hardship to the empiricists to be thrown back, in

their judgments of ethical commands, upon their criteria for "nonsense" among

declaratives. On the other hand ethical imperatives may be interpreted as

impersonal commands, the penalty clause of which involves society primarily

and the individual only quite indirectly. For example, "Thou shalt not kill!"

might be translated, "Either society's survival value (and hence thy life ex-

pectancy, probable well-being, security, etc.) diminishes or thou dost not (un-

officially) kill." Since such a statement involves only the extremely long run

and is only statistically valid it would seem quite natural to call on God or the

police to enforce it (provide artificial penalties) since there would be too many

negative instances to make it self-enforcing. An alternative formulation might

be, "Either thou dot not kill or thou wilt suffer through emotional sympathy

(role-taking, conscience) with the killed, the bereaved, etc. or through social

reaction." Other formulations are, of course, possible also. It is not intended

to prejudice that issue at this point except as is required by the maintenance of

a non-metaphysical attitude.

The fact that moral imperatives can conflict and still seem individually valid

is probably due to the fact, if we resolve to interpret them empirically, that

every time this genuinely occurs, they involve different penalties, i.e. belong

to different reference systems, and hence may both be true in even the most

narrow causal interpretation simply because the ends involved (the avoidance

of the penalties) may be causally mutually exclusive.

Hofstadter and McKinsey speak about the correctnessof commands, apparently

some sort of ethical concept which they do not discuss fully. Possibly a com-

mand might be considered Correctp (correct with respect to P) if the making

of the command can be shown to be commanded by another true command with

penalty P, i.e. if making the command (with whatever penalty of its own) is a

causally necessary condition to the avoidance of P. The question of whether

a ranking of penalties (or ends, since many penalties would more conveniently

be defined as the non-attainment of positive ends) might show that one penalty

or end was stronger behaviorally than all others and so afford a very stable

reference system for the definition of "Correct" without subscript is not neces-

sary to prejudge for the sake of the first definition, although it may be somewhat

what Hofstadter and McKinsey had in mind.

Chicago, III.

This content downloaded from 201.081.210.097 on September 05, 2016 14:24:44 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

SEMIOTIC STATUS OF COMMANDS 315

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Further references will be found in the articles mentioned below.

BUCHLER, J. "Value Statements", Analysis, vol. 4, April 1937.

CARNAP,R. "Testability and Meaning", Phil. of Sci., vols. 3 and 4, 1936-7.

FEIGL,H. "Logical Empiricism" in Twentieth Century Philosophy, Ed. D. Runes, New

York, 1943.

HOFSTADTER,A. ANDMCKINSEY,

J. C. C. "On the Logic of Imperatives", Phil. of Sci.,

vol. 6, 1939.

J0RGENSON,J. "Imperatives and Logic", Erkenntnis, Band 7, Heft 4.

KAPLAN, A. "Are Moral Judgments Assertions?", Phil. Review, 1942.

MORRIS, C. W. "Foundations of the Theory of Signs", International Encyclopedia of

Unified Science, vol. I, no. 2, Chicago, 1939.

Ross, A. "Imperatives and Logic", Theoria 7, 1941. Also Phil. of Sci., vol. 11, 1944.

This content downloaded from 201.081.210.097 on September 05, 2016 14:24:44 PM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

You might also like

- AIKEN. The Levels of Moral Discourse PDFDocument15 pagesAIKEN. The Levels of Moral Discourse PDFErnesto CastroNo ratings yet

- Dahl - 1957 - The Concept of PowerDocument15 pagesDahl - 1957 - The Concept of Powermiki7555No ratings yet

- Dahl Power 1957Document15 pagesDahl Power 1957api-315452084No ratings yet

- FIORIN, José Luiz. Argumentação. (Argumentation) - São Paulo: Contexto, 2015. 272 PDocument9 pagesFIORIN, José Luiz. Argumentação. (Argumentation) - São Paulo: Contexto, 2015. 272 PEmerson SaraivaNo ratings yet

- Robert Dahl: The Concept of PowerDocument15 pagesRobert Dahl: The Concept of PowerIvica BocevskiNo ratings yet

- Agamograph Drawing TemplateDocument5 pagesAgamograph Drawing TemplateAbinash MallickNo ratings yet

- 9200 Serial Communications Protocol and ION / Modbus Register MapDocument23 pages9200 Serial Communications Protocol and ION / Modbus Register Mapsahil4INDNo ratings yet

- Burke - RetorikaDocument4 pagesBurke - RetorikaFiktivni FikusNo ratings yet

- Two Traditions of Analogy by WILLIAM R. BROWNDocument12 pagesTwo Traditions of Analogy by WILLIAM R. BROWNBalingkangNo ratings yet

- "Is" and "Ought" in Hume's and Kant 'S PhilosophyDocument7 pages"Is" and "Ought" in Hume's and Kant 'S PhilosophyStarcraft2shit 2sNo ratings yet

- Grice Logic&Conversation WJL 1989Document11 pagesGrice Logic&Conversation WJL 1989Sara EldalyNo ratings yet

- Book-Introduction The Five Key Terms of Dramatism (MDesIxD)Document5 pagesBook-Introduction The Five Key Terms of Dramatism (MDesIxD)T CNo ratings yet

- Inferentialism and Its Discontents: 1 Inferentialism (A Brief Overview)Document26 pagesInferentialism and Its Discontents: 1 Inferentialism (A Brief Overview)Nombre FalsoNo ratings yet

- Mind Association, Oxford University Press MindDocument7 pagesMind Association, Oxford University Press MindsupervenienceNo ratings yet

- Brown 1989 PDFDocument12 pagesBrown 1989 PDFpompoNo ratings yet

- Indicative Conditionals StalnakerDocument18 pagesIndicative Conditionals StalnakerSamuel OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Fodor, J. On Knowing What We Would SayDocument16 pagesFodor, J. On Knowing What We Would SayRodolfo van GoodmanNo ratings yet

- Doing What Comes NaturallyDocument8 pagesDoing What Comes NaturallyellysweetyNo ratings yet

- Attitude Reports, Events, and Partial ModelsDocument73 pagesAttitude Reports, Events, and Partial ModelsChandra Sekhar JujjuvarapuNo ratings yet

- Norm and ActionDocument141 pagesNorm and ActionsaironweNo ratings yet

- Putnam, H. Psychological Concepts, Explication, and Ordinary LanguageDocument8 pagesPutnam, H. Psychological Concepts, Explication, and Ordinary LanguageRodolfo van GoodmanNo ratings yet

- Frege-Geach Objection: Mark Van RoojenDocument10 pagesFrege-Geach Objection: Mark Van RoojenmikadikaNo ratings yet

- A Note On Semantic RealismDocument6 pagesA Note On Semantic RealismfranciscoNo ratings yet

- Converstational Postulate RevisitedDocument9 pagesConverstational Postulate RevisitedIoana CatrunaNo ratings yet

- Ennis - 1982 - IDENTIFYING IMPLICIT ASSUMPTIONSDocument26 pagesEnnis - 1982 - IDENTIFYING IMPLICIT ASSUMPTIONSAntonioNo ratings yet

- 4940-Article Text-16293-2-10-20190606 PDFDocument23 pages4940-Article Text-16293-2-10-20190606 PDFMario Daniel QuevedoNo ratings yet

- The Merits of Incoherence: Analytic Philosophy Vol. 59 No. 1 March 2018 Pp. 112-141Document30 pagesThe Merits of Incoherence: Analytic Philosophy Vol. 59 No. 1 March 2018 Pp. 112-141Andrew LiebermannNo ratings yet

- What Is ArgDocument26 pagesWhat Is ArgRodney Takundanashe MandizvidzaNo ratings yet

- The Delphi MethodDocument32 pagesThe Delphi MethodMinh Hong NguyenNo ratings yet

- Nous - 2014 - Fricker - What S The Point of Blame A Paradigm Based ExplanationDocument19 pagesNous - 2014 - Fricker - What S The Point of Blame A Paradigm Based ExplanationGONZALO VELASCO ARIASNo ratings yet

- A New Light On Non-Deductive Argumentation Schemes: Department of Philosophy University of Hamburg GermanyDocument10 pagesA New Light On Non-Deductive Argumentation Schemes: Department of Philosophy University of Hamburg GermanyAli SalehiNo ratings yet

- Symbolic Logic Odysseus Makridis Full ChapterDocument67 pagesSymbolic Logic Odysseus Makridis Full Chapterpaul.kut532100% (8)

- Carnap Rudolf - The Elimination of Metaphysics Through Logical Analysis of LanguageDocument14 pagesCarnap Rudolf - The Elimination of Metaphysics Through Logical Analysis of LanguageEdvardvsNo ratings yet

- Tyler Burge The Content of Pro-AttitudeDocument7 pagesTyler Burge The Content of Pro-AttitudeAran ArslanNo ratings yet

- Hume and The Lockean Background Induction and The Uniformity PrincipleDocument30 pagesHume and The Lockean Background Induction and The Uniformity PrincipleKbkjas JvkndNo ratings yet

- From Beginning To Irony - Self-Reflection in The Arts and SciencesDocument10 pagesFrom Beginning To Irony - Self-Reflection in The Arts and SciencesQ JoniNo ratings yet

- The Social Anatomy of InferenceDocument7 pagesThe Social Anatomy of InferenceOrlandoAlarcónNo ratings yet

- Etchemendy, J. (1983) - The Doctrine of Logic As FormDocument16 pagesEtchemendy, J. (1983) - The Doctrine of Logic As FormY ́ GolonacNo ratings yet

- The Operational Analysis of Psychological Terms - SkinnerDocument20 pagesThe Operational Analysis of Psychological Terms - Skinnerwalterhorn100% (1)

- Springer: Springer Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To SyntheseDocument23 pagesSpringer: Springer Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To SyntheseNayeli Gutiérrez HernándezNo ratings yet

- Reasons: Joshua GertDocument12 pagesReasons: Joshua GertmikadikaNo ratings yet

- The University of Chicago PressDocument18 pagesThe University of Chicago PressHorman DiatoniNo ratings yet

- Associationism PDFDocument16 pagesAssociationism PDFMuNo ratings yet

- CDCM Quotes 09-9-23 ADocument4 pagesCDCM Quotes 09-9-23 ADanielSacilottoNo ratings yet

- (Palgrave Philosophy Today) Odysseus Makridis - Symbolic Logic-Palgrave Macmillan (2022)Document493 pages(Palgrave Philosophy Today) Odysseus Makridis - Symbolic Logic-Palgrave Macmillan (2022)Marios BeddaweNo ratings yet

- Skinner, Q. (1971) On Performing and Explaining Linguistic ActionsDocument22 pagesSkinner, Q. (1971) On Performing and Explaining Linguistic ActionsKostas BizasNo ratings yet

- T H E Journal of Philosophy Psychology and Scientific MethodsDocument9 pagesT H E Journal of Philosophy Psychology and Scientific MethodsLaura Nicoleta BorhanNo ratings yet

- Ricoeur, Paul. Capabilities and RightsDocument10 pagesRicoeur, Paul. Capabilities and Rightshefestos11No ratings yet

- The Concept of Power: Robert DahlDocument15 pagesThe Concept of Power: Robert DahlNada SalihNo ratings yet

- Jurisprudence PaperDocument9 pagesJurisprudence PaperShaikhNo ratings yet

- Car NapDocument21 pagesCar Napmichael_poageNo ratings yet

- Dahl, Concept of Power (A)Document15 pagesDahl, Concept of Power (A)Vladislava RyabovolovaNo ratings yet

- The Metaphorical Process As Cognition, Imagination, Feling - Paul Ricoeur 1978Document18 pagesThe Metaphorical Process As Cognition, Imagination, Feling - Paul Ricoeur 1978CarlosNo ratings yet

- Conceptual Ethics pt1 - Plunkett-Burgess2013Document11 pagesConceptual Ethics pt1 - Plunkett-Burgess2013Tim HardwickNo ratings yet

- Hartmann 1931Document12 pagesHartmann 1931Matheus Pereira CostaNo ratings yet

- Constanze Peres: On Using Metaphors in PhilosophyDocument9 pagesConstanze Peres: On Using Metaphors in PhilosophymayoshtyNo ratings yet

- Logic, Reasoning, Information: June 2015Document17 pagesLogic, Reasoning, Information: June 2015Ubyy UbongNo ratings yet

- Corcoran Hare and Others On The PropositionDocument26 pagesCorcoran Hare and Others On The PropositionGustavo VilarNo ratings yet

- Some Sub-Atomic Particles of Logic: R. M. HareDocument15 pagesSome Sub-Atomic Particles of Logic: R. M. HareDaniele ChiffiNo ratings yet

- KANTDocument6 pagesKANTPal GuptaNo ratings yet

- Tent A 021220Document9 pagesTent A 021220jkgoyalNo ratings yet

- Dynamic Economic Dispatch Using Model Predictive Control AlgorithmDocument7 pagesDynamic Economic Dispatch Using Model Predictive Control Algorithmselaroth168No ratings yet

- Confidential: Final Examination Semester Ii SESSION 2014/2015 (Solution)Document13 pagesConfidential: Final Examination Semester Ii SESSION 2014/2015 (Solution)marwanNo ratings yet

- Perimeter and Area Lesson Plan McdanielDocument3 pagesPerimeter and Area Lesson Plan Mcdanielapi-242825904No ratings yet

- MGT214 - Chapter 11 Investment Decision CriteriaDocument16 pagesMGT214 - Chapter 11 Investment Decision CriteriaPatty VirayNo ratings yet

- SP47Document177 pagesSP47Venkata Bhaskar DameraNo ratings yet

- Koos Scoring 2012Document3 pagesKoos Scoring 2012rythm_21No ratings yet

- Cot Act. 6Document7 pagesCot Act. 6FRECY MARZANNo ratings yet

- 18CS55 ADP Notes Module 4 and 5Document72 pages18CS55 ADP Notes Module 4 and 5Palguni DS100% (1)

- LPP SimplexDocument107 pagesLPP SimplexAynalemNo ratings yet

- Extreme Values and Saddle PointsDocument35 pagesExtreme Values and Saddle PointsGeorge SimmonsNo ratings yet

- Tablet Press ModelDocument22 pagesTablet Press Modelmarcelo100% (2)

- IE2152 Statistics For Industrial Engineers Problem Solving SessionsDocument57 pagesIE2152 Statistics For Industrial Engineers Problem Solving SessionsKutay ArslanNo ratings yet

- Graphics in PHPDocument31 pagesGraphics in PHPVivekNo ratings yet

- Sets and Venn DiagramsDocument9 pagesSets and Venn DiagramsDominic SavioNo ratings yet

- Number System: Amity School of Engineering and TechnologyDocument103 pagesNumber System: Amity School of Engineering and TechnologyAkanksha ThakurNo ratings yet

- Iv-Day 16Document3 pagesIv-Day 16Florita LagramaNo ratings yet

- Cobol Performance TuningDocument55 pagesCobol Performance TuningApril MartinezNo ratings yet

- Pile Foundation - PresentationDocument39 pagesPile Foundation - PresentationJimmy KalumataNo ratings yet

- DLL-2nd-week 7-12Document6 pagesDLL-2nd-week 7-12cathline austriaNo ratings yet

- Gymnasium Sound Control Solutions: Product OptionsDocument1 pageGymnasium Sound Control Solutions: Product OptionsRenzon SisonNo ratings yet

- Interactive Simulation of Power Systems Etap Applications and TeDocument12 pagesInteractive Simulation of Power Systems Etap Applications and TeMuhammad ShahzaibNo ratings yet

- Phy Maths Integration-Final2 PDFDocument62 pagesPhy Maths Integration-Final2 PDFSimran GuptaNo ratings yet

- Unit V Fourier Transform PDFDocument53 pagesUnit V Fourier Transform PDFRahul JRNo ratings yet

- Precision Rectifiers: Elliott Sound ProductsDocument12 pagesPrecision Rectifiers: Elliott Sound ProductsDRAGAN ANDRICNo ratings yet

- Iso 1328-Agma - Parte 1Document35 pagesIso 1328-Agma - Parte 1bernaldoarnaoNo ratings yet

- Longitudinal Vibration of A Bar ": Presentation OnDocument17 pagesLongitudinal Vibration of A Bar ": Presentation OnamitpatelNo ratings yet

- EE462 Design of Digital Control Systems PDFDocument2 pagesEE462 Design of Digital Control Systems PDFArya RahulNo ratings yet