Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Abraham Lincoln & Frederick Douglass - The Story Behind An American Friendship

Abraham Lincoln & Frederick Douglass - The Story Behind An American Friendship

Uploaded by

Gleh Huston AppletonOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Abraham Lincoln & Frederick Douglass - The Story Behind An American Friendship

Abraham Lincoln & Frederick Douglass - The Story Behind An American Friendship

Uploaded by

Gleh Huston AppletonCopyright:

Available Formats

TEXT

Abraham Lincoln & Frederick Douglass: The Story Behind an American

Friendship

Near the end of the Civil War, Frederick Douglass attended Abraham Lincoln’s second inaugural address. Wishing to congratulate Lincoln, Douglass approached the reception at

the White House, where guards refused to let him enter

Grade Level 6-8, 9-12 BY RUSSELL FREEDMAN

Text Type: Informational

Topic: Race & Ethnicity, Class

Subject: History

Social Justice Domain: Diversity, Justice, Action

Social Justice Standard: JU12 , JU13 , AC18 , DI9 , JU11 , AC16 , DI8 , JU14 , JU15

Complexity: Mid to end 7th

Lexile Measure: 1080; 1430; 6; 9.1; 61

Tier 2 terms: Festive, inauguration (inaugural), victoriously, figure, blatted, careworn, deliver, bitter, institution, scourge, retribution, flourish, abolished, bind up, earnest, ventured, insisted, acquaintance, elegant, detain

Tier 3 terms: inauguration (inaugural), figure, deliver, institution, scourge, retribution, earnest, ventured

Web Version: https://www.tolerance.org/classroom-resources/texts/abraham-lincoln-frederick-douglass-the-story-behind-an-american

When Abraham Lincoln was assassinated, Frederick Douglass, in his mid-forties, was America’s most influential

black citizen. For the rest of his long life, he continued in his speeches and writings to be a powerful voice for social

justice, denouncing racism and demanding equal rights for blacks and whites alike. During the Reconstruction era

of the 1870s and 1880s, when many of the rights gained after emancipation were snatched away in the South,

Douglass spoke out against lynchings, the terrorism of the Ku Klux Klan, and the Jim Crow laws that were devised

to keep blacks in their place and away from the ballot box.

As he traveled widely, lecturing on social issues and national politics, Douglass spoke often about Abraham

Lincoln. During the war, he had criticized the president for being slow to move against slavery, for resisting the

enlistment of black soldiers, for inviting blacks “to leave the land in which we were born.” But with emancipation,

and in the aftermath of the war, Douglass had come to appreciate Lincoln’s sensitivity to popular opinion and to

admire the political skills Lincoln employed to win public support. “His greatest mission was to accomplish two

things: first, to save the country from dismemberment and ruin; and, second, to free his country from the great

crime of slavery. To do one or the other, or both,” Douglass said, Lincoln needed “the earnest sympathy and the

powerful cooperation of his fellow countrymen.”

In the 1870s, Douglass moved with his family to Washington, D.C., where he edited a newspaper, held a succession

of federal appointments, and clearly enjoyed his exalted position as an elder statesman of America’s black citizens.

And he continued to denounce injustice and inequality with the undiminished fervor of an old warrior.

His last home was a large, comfortable house called Cedar Hill, perched high on a hilltop looking down at the

Anacostia River and the U.S. capital beyond. Cedar Hill had a spacious library, large enough to hold Douglass’s

collection of some two thousand books. From time to time, as he picked a book from his shelves and settled down

to read, he must have recalled those distant days in Baltimore when he was a young slave named Frederick Bailey,

a determined boy who owned just one book, a single volume that he kept hidden from view and read in secret.

Lincoln had read and studied the same book as a young man in New Salem. That was something they had in

common, a shared experience that helped each of them rise from obscurity to greatness. “He was the architect of

his own fortune, a self-made man,” Douglass wrote of Lincoln. He had “ascended high, but with hard hands and

honest work built the ladder on which he climbed”—words that Douglass, as he was aware, could easily have

applied to himself. (101-103)

_______________________________________________________________________________________

CHAPTER 10: “MY FRIEND DOUGLASS”

On the morning of March 4, 1865, Frederick Douglass joined a festive crowd of 30,000 spectators at the U.S.

Capitol to witness Abraham Lincoln’s second inauguration. Weeks of rain had turned Washington’s unpaved

streets into a sea of mud, but despite the wet and windy weather, the crowd was in a mood to celebrate. Union

troops were marching victoriously through the South. Everyone knew that the war was almost over. When

Lincoln’s tall figure appeared, “cheer upon cheer arose, bands blatted upon the air, and flags waved all over the

scene.”

Douglass found a place for himself directly in front of the speaker’s stand. He could see every crease in

Lincoln’s careworn face as the president stepped forward to deliver his second inaugural address.

The Civil War had cost more than 600,000 American lives. The fighting had been more bitter and lasted far longer

than anyone could have imagined. The “cause of the war” was slavery, Lincoln declared. Slavery was the

one institution that divided the nation. And slavery was a hateful and evil practice—a sin in the sight of God. “This

mighty scourge of war” was a terrible retribution, a punishment for allowing human bondage to flourish on the

nation’s soil. Now that slavery was abolished, the time had come “to bind up the nation’s wounds” and “cherish a

just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.”

Following the “wonderfully quiet, earnest, and solemn” ceremony, Douglass wanted to congratulate Lincoln

personally. That evening he joined the crowd heading to attend the gala inaugural reception at the White House—a

building completed with slave labor just a half century earlier. “Though no colored persons had ever ventured to

present themselves on such occasions,” Douglass wrote, “it seemed, now that freedom had become the law of the

republic, and colored men were on the battlefield, mingling their blood with that of white men in one common

effort to save the country, that it was not too great an assumption for a colored man to offer his congratulations to

the President with those of other citizens.”

At the White House door, Douglass was stopped by two policemen who “took me rudely by the arm and ordered

me to stand back.” Their orders, they told him, were “to admit no persons of my color.” Douglass didn’t believe

them. He was positive that no such order could have come from the president.

The police tried to steer Douglass away from the doorway and out a side exit. He refused to leave. “I shall not go

out of this building till I see President Lincoln,” he insisted. Just then he spotted an acquaintance who was

entering the building and asked him to send word “to Mr. Lincoln that Frederick Douglass is detained by officers

at the door.” Within moments, Douglass was being escorted into the elegant East Room of the White House.

Lincoln stood among his guests “like a mountain pine high above all others.” As Douglass approached through the

crowd, Lincoln called out, “Here comes my friend Douglass.” The president took Douglass by the hand. “I am glad

to see you,” he said. I saw you in the crowd today, listening to my inaugural address. How did you like it?”

Douglass hesitated. “Mr. Lincoln, I must not detain you with my poor opinion, when there are thousands waiting

to shake hands with you.”

“No, no,” said the president. “You must stop a little Douglass; there is no man whose opinion I value more than

yours. I want to know what you think of it.”

“Mr. Lincoln, that was a sacred effort,” Douglass replied.

“I’m glad you liked it!”

And with that, Douglass moved on, making way for other guests who were waiting to shake the hand of Abraham

Lincoln.

TEXT DEPENDENT QUESTIONS

1.

You might also like

- Zurich Cancellation FormDocument1 pageZurich Cancellation Formkilobombo43% (7)

- Offer From InterviewBit To Bikramjeet SinghDocument2 pagesOffer From InterviewBit To Bikramjeet SinghBikramNo ratings yet

- We Are The Ship LPDocument4 pagesWe Are The Ship LPapi-236207520No ratings yet

- Chapter 7 Section 3Document6 pagesChapter 7 Section 3Tsean MattooNo ratings yet

- Galloping The Globe United States PassportDocument18 pagesGalloping The Globe United States Passportmeara22No ratings yet

- Webquest Japanese American InternmentDocument8 pagesWebquest Japanese American Internmentapi-376301141No ratings yet

- Golden Anniversary Celebration of Civil Rights Activities in North LouisianaDocument142 pagesGolden Anniversary Celebration of Civil Rights Activities in North LouisianaAsriel McLainNo ratings yet

- (21152593) 1.21.3.2 NDocument573 pages(21152593) 1.21.3.2 NollieknightNo ratings yet

- Micro-Finance/credit Institution: Its Principles, and Relevance in Liberia's Post-War ReconstructionDocument9 pagesMicro-Finance/credit Institution: Its Principles, and Relevance in Liberia's Post-War ReconstructionGleh Huston Appleton100% (4)

- Notable Books For A Global Society ProjectDocument49 pagesNotable Books For A Global Society Projectapi-488579854No ratings yet

- Benjamin BannekerDocument2 pagesBenjamin BannekerAnonymous 7QjNuvoCpI100% (1)

- Legacy of Greece Student NotebookDocument8 pagesLegacy of Greece Student Notebookapi-233464494No ratings yet

- 1619 Project The Idea of America Part 2Document17 pages1619 Project The Idea of America Part 2api-593462252No ratings yet

- Gloria's Voice: The Story of Gloria Steinem—Feminist, Activist, LeaderFrom EverandGloria's Voice: The Story of Gloria Steinem—Feminist, Activist, LeaderNo ratings yet

- The Call of The Wild: by Jack LondonDocument42 pagesThe Call of The Wild: by Jack Londongjkj100% (1)

- How Marcus Whitman Saved Oregon: A True Romance of Patriotic Heroism Christian Devotion and Final MartyrdomFrom EverandHow Marcus Whitman Saved Oregon: A True Romance of Patriotic Heroism Christian Devotion and Final MartyrdomRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Rebels & Revolutions: Real Tales of Radical Change in AmericaFrom EverandRebels & Revolutions: Real Tales of Radical Change in AmericaNo ratings yet

- A Soldier's Secret: The Incredible True Story of Sarah Edmonds, a Civil War HeroFrom EverandA Soldier's Secret: The Incredible True Story of Sarah Edmonds, a Civil War HeroRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (12)

- Ancient Civilization Project For 6th GradeDocument8 pagesAncient Civilization Project For 6th GradeYamilís González CottoNo ratings yet

- The Duckster Ducklings Go to Mars: Understanding CapitalizationFrom EverandThe Duckster Ducklings Go to Mars: Understanding CapitalizationNo ratings yet

- Uncle Eric Books Lesson PlansDocument6 pagesUncle Eric Books Lesson PlansMelanyNo ratings yet

- Caste System in Ancient IndiaDocument3 pagesCaste System in Ancient IndiaA y u s h100% (1)

- Scholastic Week.1Document22 pagesScholastic Week.1Evita Mae BauNo ratings yet

- One False Note ModuleDocument7 pagesOne False Note ModuleJasmin Ajo100% (1)

- United States History in Rhyme: A Child’s First History Book: a Must Read for All AmericansFrom EverandUnited States History in Rhyme: A Child’s First History Book: a Must Read for All AmericansNo ratings yet

- Treasures: Visible & Invisible: Visible & Invisible SeriesFrom EverandTreasures: Visible & Invisible: Visible & Invisible SeriesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Balderdash!: John Newbery and the Boisterous Birth of Children's BooksFrom EverandBalderdash!: John Newbery and the Boisterous Birth of Children's BooksRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (17)

- Civil War UbdDocument5 pagesCivil War Ubdapi-267445217No ratings yet

- Mini-Reader: © Gilbert Barrera 2019Document20 pagesMini-Reader: © Gilbert Barrera 2019ghadeer alkhayat100% (1)

- Brothers of the Buffalo: A Novel of the Red River WarFrom EverandBrothers of the Buffalo: A Novel of the Red River WarRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Essay Writing Tips UwiDocument4 pagesEssay Writing Tips UwiJosstein MohammedNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To Myth: TH THDocument6 pagesAn Introduction To Myth: TH THAndreas100% (1)

- Chapter 17 Lesson 1 and 5Document9 pagesChapter 17 Lesson 1 and 5api-326911893No ratings yet

- Lunch Counter Sit-Ins: How Photographs Helped Foster Peaceful Civil Rights ProtestsFrom EverandLunch Counter Sit-Ins: How Photographs Helped Foster Peaceful Civil Rights ProtestsNo ratings yet

- Are Indian Reservations Part of the US? US History Lessons 4th Grade | Children's American HistoryFrom EverandAre Indian Reservations Part of the US? US History Lessons 4th Grade | Children's American HistoryNo ratings yet

- The Women Behind Rosie the Riveter: Working for the U.S. War EffortFrom EverandThe Women Behind Rosie the Riveter: Working for the U.S. War EffortNo ratings yet

- History of American Holidays: A Thought-Provoking Glimpse into AmericaFrom EverandHistory of American Holidays: A Thought-Provoking Glimpse into AmericaNo ratings yet

- TDES7001 - Design Thinking - Brief - ENDocument2 pagesTDES7001 - Design Thinking - Brief - ENGleh Huston AppletonNo ratings yet

- Cultural Heritage As A Trigger For Civic Wealth CreationDocument8 pagesCultural Heritage As A Trigger For Civic Wealth CreationGleh Huston AppletonNo ratings yet

- Peach Yellow Grid Mind Map BrainstormDocument1 pagePeach Yellow Grid Mind Map BrainstormGleh Huston AppletonNo ratings yet

- A Place in The Sun Buying Guide Spain 2021Document46 pagesA Place in The Sun Buying Guide Spain 2021Gleh Huston AppletonNo ratings yet

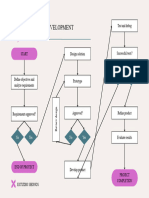

- Beige and Pink Modern Business Process Flowchart DiagramDocument1 pageBeige and Pink Modern Business Process Flowchart DiagramGleh Huston AppletonNo ratings yet

- Gupea 2077 66587 1.pdf JsessionidDocument90 pagesGupea 2077 66587 1.pdf JsessionidGleh Huston AppletonNo ratings yet

- Application - MI - Master of Technology ManagementDocument3 pagesApplication - MI - Master of Technology ManagementGleh Huston AppletonNo ratings yet

- Sponsors Designated Advisors Auditors and Approved Index CalculatorsDocument15 pagesSponsors Designated Advisors Auditors and Approved Index CalculatorsGleh Huston AppletonNo ratings yet

- UN Career Framework EN FINALDocument19 pagesUN Career Framework EN FINALGleh Huston AppletonNo ratings yet

- Catholics and AmericaDocument27 pagesCatholics and AmericaGleh Huston AppletonNo ratings yet

- Codesure Intro - Service - Delivery - Coverage - Tool - MRF - South SudanDocument17 pagesCodesure Intro - Service - Delivery - Coverage - Tool - MRF - South SudanGleh Huston AppletonNo ratings yet

- Ageing and Health: A Briefing On As Part of The 30 September 2021Document27 pagesAgeing and Health: A Briefing On As Part of The 30 September 2021Gleh Huston AppletonNo ratings yet

- America As A Christian NationDocument86 pagesAmerica As A Christian NationGleh Huston AppletonNo ratings yet

- Sps. Rebamonte v. Sps. LuceroDocument4 pagesSps. Rebamonte v. Sps. LuceroTricia Montoya100% (1)

- CompressedDocument60 pagesCompressedshivaprasadssNo ratings yet

- Alcantara vs. Director of PrisonsDocument8 pagesAlcantara vs. Director of PrisonsLea RealNo ratings yet

- Syllabus African Politics Fall2020Document15 pagesSyllabus African Politics Fall2020gusNo ratings yet

- Border Coalition Letter To GOP LeadersDocument2 pagesBorder Coalition Letter To GOP LeadersFox NewsNo ratings yet

- Defenses of The Common CarrierDocument6 pagesDefenses of The Common CarrierXian Alden67% (3)

- Exercise-Power Sharing: Social Science - XDocument1 pageExercise-Power Sharing: Social Science - XVaishnaviNo ratings yet

- Ad 2023-22-18Document7 pagesAd 2023-22-18AbdeslamBahidNo ratings yet

- Forensic Psy OutlineDocument3 pagesForensic Psy OutlineTEOFILO PALSIMON JR.No ratings yet

- Definition of Police ReportDocument5 pagesDefinition of Police ReportMagr EscaNo ratings yet

- Customs-A G - EnterpriseDocument7 pagesCustoms-A G - EnterpriseneelsterNo ratings yet

- Adobe Scan 02-Jun-2021Document11 pagesAdobe Scan 02-Jun-2021paragddNo ratings yet

- Demafiles Vs Commission On Elections, 21 SCRA 1462, G.R. No. L-28396, December 29, 1967Document2 pagesDemafiles Vs Commission On Elections, 21 SCRA 1462, G.R. No. L-28396, December 29, 1967Gi NoNo ratings yet

- Advantages and Disadvantages of RH BILLDocument1 pageAdvantages and Disadvantages of RH BILLKenneth Jabonete59% (22)

- Bylaws (Articles of Incorporation Format - SEC)Document18 pagesBylaws (Articles of Incorporation Format - SEC)Erin GamerNo ratings yet

- L-500 Valvulas Rego Catalogo 2Document218 pagesL-500 Valvulas Rego Catalogo 2Marcio FariaNo ratings yet

- Case 4. Moreno-Lentfer vs. Wolff. GR No. 152317. November 10, 2004Document3 pagesCase 4. Moreno-Lentfer vs. Wolff. GR No. 152317. November 10, 2004eUG SACLONo ratings yet

- Petition To Confirm AADocument11 pagesPetition To Confirm AARosana FernandezNo ratings yet

- Verification - CSWIP Without CswipDocument1 pageVerification - CSWIP Without CswipKarthik DhayalanNo ratings yet

- Interpretation of Mandatory and Directory Statutes: Presented By: Rinkey Sharma Asst. Prof. of Law IilsDocument18 pagesInterpretation of Mandatory and Directory Statutes: Presented By: Rinkey Sharma Asst. Prof. of Law Iilsvenkatesha conapalliNo ratings yet

- The Small Business Standard: The Chartered Quality InstituteDocument4 pagesThe Small Business Standard: The Chartered Quality Institutedrrmm2sNo ratings yet

- Application FinalPrintDocument3 pagesApplication FinalPrintMunavvar AliNo ratings yet

- Tender Review and Documents ChecklistDocument2 pagesTender Review and Documents ChecklistsugamsehgalNo ratings yet

- Journal A NEW TRAINING PROGRAM IN DEVELOPING CULTURAL INTELLIGENCE CAN ALSO IMPROVE INNOVATIVE WORK BEHAVIOUR AND RESILIENCEDocument20 pagesJournal A NEW TRAINING PROGRAM IN DEVELOPING CULTURAL INTELLIGENCE CAN ALSO IMPROVE INNOVATIVE WORK BEHAVIOUR AND RESILIENCEAudrey KalaNo ratings yet

- Document (12) Reaction Paper About JournalsDocument4 pagesDocument (12) Reaction Paper About JournalsKervie Jay LachaonaNo ratings yet

- Memo 097.7 - 061520 - Estimated Increase Cost Construction Safety HealthDocument53 pagesMemo 097.7 - 061520 - Estimated Increase Cost Construction Safety HealthJonah YaranonNo ratings yet

- Articles of The Confederation 1781 PDFDocument13 pagesArticles of The Confederation 1781 PDFRenn DallahNo ratings yet