Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Analysis South African Newspapers

Analysis South African Newspapers

Uploaded by

zeyad altairCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Grade 9 English Home Language Task 5 June Exam ModeratedDocument19 pagesGrade 9 English Home Language Task 5 June Exam Moderated18118100% (5)

- Marshall Cavendish Math5 AB EFDocument283 pagesMarshall Cavendish Math5 AB EFzeyad altair86% (7)

- Apologetics, Kreeft Chapter 9: The Resurrection of Jesus ChristDocument56 pagesApologetics, Kreeft Chapter 9: The Resurrection of Jesus Christrichard100% (2)

- Critical Discourse Analysis of Political PDFDocument32 pagesCritical Discourse Analysis of Political PDFMaged HassanNo ratings yet

- Hybridity and The Rise of Korean Popular Culture in AsiaDocument21 pagesHybridity and The Rise of Korean Popular Culture in AsiaJuan Pablo DelgadoNo ratings yet

- Tata Motors StrategyDocument17 pagesTata Motors StrategyRituraj Sen67% (3)

- Pernicious AnemiaDocument24 pagesPernicious AnemiaArthadian De PeraltaNo ratings yet

- Strategic Alliances or What Alternative The Bia Kud Chum and Community Culture in ThailandDocument22 pagesStrategic Alliances or What Alternative The Bia Kud Chum and Community Culture in Thailandyusrildwiseptiawan123No ratings yet

- African Ngos: The New Compradors?: RoundtableDocument16 pagesAfrican Ngos: The New Compradors?: RoundtableLeah WalsheNo ratings yet

- Discourse & Society: Critical Discourse Analysis of Political Press ConferencesDocument32 pagesDiscourse & Society: Critical Discourse Analysis of Political Press Conferencesnona nonaNo ratings yet

- TSMOs and Protest Participation - Kyle Dodson, 2016Document37 pagesTSMOs and Protest Participation - Kyle Dodson, 2016ClarinNo ratings yet

- Community Psychology in South Africa Ori20160208-28293-O2wd07Document18 pagesCommunity Psychology in South Africa Ori20160208-28293-O2wd07Stephine ngobeniNo ratings yet

- Wasserman, Herman - The Possibilities of ICT For Social Activism in AfricaDocument22 pagesWasserman, Herman - The Possibilities of ICT For Social Activism in AfricaDiego MarquesNo ratings yet

- Post WWI Military Disarmament and Interwar Fascism in SwedenDocument21 pagesPost WWI Military Disarmament and Interwar Fascism in SwedenMarco Fernández FischerNo ratings yet

- The Proposal EconomyDocument23 pagesThe Proposal EconomyZina LaouarNo ratings yet

- Hasbara 20 Israels Public Diplomacyinthe Digital AgeDocument29 pagesHasbara 20 Israels Public Diplomacyinthe Digital Ageboris.rossenNo ratings yet

- Econ 104Document7 pagesEcon 104Adetutu AnnieNo ratings yet

- Africa and International RelationsDocument13 pagesAfrica and International Relationshabt2002No ratings yet

- A Corpus-Assisted Critical Discourse Analysis of TDocument20 pagesA Corpus-Assisted Critical Discourse Analysis of TDr-RedaOsmanNo ratings yet

- Presentatopm Civic EngagementDocument18 pagesPresentatopm Civic EngagementEdrian Joseph AragonNo ratings yet

- History Research Vol.3 No.4Document90 pagesHistory Research Vol.3 No.4Daniela Vásquez Pino0% (1)

- LazarusSeedatNaidooAPAChapter2884-hco-2013-0011-R-EVAuthorEditsDec2014Document46 pagesLazarusSeedatNaidooAPAChapter2884-hco-2013-0011-R-EVAuthorEditsDec2014tata0akhilNo ratings yet

- RichardsonColombo JLPfinalDocument25 pagesRichardsonColombo JLPfinalfacu 123No ratings yet

- Community Media Their Communities and Co PDFDocument13 pagesCommunity Media Their Communities and Co PDFInês Santos MouraNo ratings yet

- Introduction RegionalismDocument14 pagesIntroduction RegionalismLie MarNo ratings yet

- The Discourse of ProtestDocument15 pagesThe Discourse of ProtestCatalina BüchnerNo ratings yet

- Week Four Stevens 2003 Academic Representations of RaceDocument19 pagesWeek Four Stevens 2003 Academic Representations of RaceNtando Mandla MakwelaNo ratings yet

- Backtothe Future Uncovering Deeper Meaningsin Historical Newspaper TextsDocument21 pagesBacktothe Future Uncovering Deeper Meaningsin Historical Newspaper Textssinghk2No ratings yet

- Alexander, Peter 2010 'Rebellion of The Poor - South Africa's Service Delivery Protests - A Preliminary Analysis' RAPE, Vol. 37, No. 123 (March PP., 25 - 40Document17 pagesAlexander, Peter 2010 'Rebellion of The Poor - South Africa's Service Delivery Protests - A Preliminary Analysis' RAPE, Vol. 37, No. 123 (March PP., 25 - 40voxpop88No ratings yet

- Development of A Social Enterprise Typology in A Canadian ContextDocument39 pagesDevelopment of A Social Enterprise Typology in A Canadian ContextMilan IlicNo ratings yet

- Article Arab Imagery FRDocument33 pagesArticle Arab Imagery FRJin LaprixNo ratings yet

- Politics and Governance in Southeast Asia BookDocument11 pagesPolitics and Governance in Southeast Asia BookRicabele MaligsaNo ratings yet

- Zeitzoff Iran Israel JPRDocument16 pagesZeitzoff Iran Israel JPRCarl SmithNo ratings yet

- Search For A New ApproachDocument11 pagesSearch For A New ApproachDeanNo ratings yet

- Developmental RegionalismDocument26 pagesDevelopmental RegionalismCharmy BienthereNo ratings yet

- Master Thesis TwitterDocument4 pagesMaster Thesis TwitterBestCollegePaperWritingServiceUK100% (2)

- Introduction To Ideas of Asian RegionalismDocument14 pagesIntroduction To Ideas of Asian RegionalismJD AmpayaNo ratings yet

- Doing (In) Justice To Iran's Nuke Activities? A Critical Discourse Analysis of News Reports of Four Western Quality NewspapersDocument9 pagesDoing (In) Justice To Iran's Nuke Activities? A Critical Discourse Analysis of News Reports of Four Western Quality NewspapersJohn Michael Barrosa SaturNo ratings yet

- The Dynamics of Orangeism in Scotland: The Social Sources of Political Influence in A Large Fraternal OrganisationDocument44 pagesThe Dynamics of Orangeism in Scotland: The Social Sources of Political Influence in A Large Fraternal OrganisationEric KaufmannNo ratings yet

- Maasai New Clothes A Develop Mentalist Modernity and Its ExclusionsDocument32 pagesMaasai New Clothes A Develop Mentalist Modernity and Its ExclusionstedonneraipasmesinfoNo ratings yet

- Polarized Discourse in The Egyptian News Critical Discourse Analysis PerspectiveDocument31 pagesPolarized Discourse in The Egyptian News Critical Discourse Analysis PerspectiveaymansofyNo ratings yet

- American Political Science AssociationDocument10 pagesAmerican Political Science AssociationCamilo CruzNo ratings yet

- Ethiopia 2002 2Document47 pagesEthiopia 2002 2Tesfaye TadesseNo ratings yet

- Location and Orientation: Introducing Indian Sociology: January 2009Document17 pagesLocation and Orientation: Introducing Indian Sociology: January 2009Rajaram DasaNo ratings yet

- Barrie Sharpe - Review of Literature On JosDocument9 pagesBarrie Sharpe - Review of Literature On JosStephen SparksNo ratings yet

- Anatomies of Protest and The Trajectories of The ADocument20 pagesAnatomies of Protest and The Trajectories of The Ateshome mekonnenNo ratings yet

- The Dynamics of Social Movement Development: Northern Ireland'S Civil Rights Movement in The 1960Document20 pagesThe Dynamics of Social Movement Development: Northern Ireland'S Civil Rights Movement in The 1960Khushi vaziraniNo ratings yet

- Syrian Crisis Research PaperDocument8 pagesSyrian Crisis Research Paperefecep7d100% (1)

- Post Hegemonic RegionalismDocument17 pagesPost Hegemonic RegionalismMarcoHuacoNo ratings yet

- Economic Policy, Distribution and Poverty: The Nature of DisagreementsDocument12 pagesEconomic Policy, Distribution and Poverty: The Nature of DisagreementskNo ratings yet

- Transnational Movement Innovation and Collaboration: Analysis of World Social Forum NetworksDocument19 pagesTransnational Movement Innovation and Collaboration: Analysis of World Social Forum Networksashari fadhilah akbarNo ratings yet

- Symbolic Reparations: A Fractured Opportunity: Ereshnee NaiduDocument20 pagesSymbolic Reparations: A Fractured Opportunity: Ereshnee NaiduLa Tana AdrianaNo ratings yet

- Networked Politics On Cyworld: The Text and Sentiment of Korean Political ProfilesDocument12 pagesNetworked Politics On Cyworld: The Text and Sentiment of Korean Political ProfilesJefka DhamanandaNo ratings yet

- Prusa Igor - Japanese Scandals and Their ProductionDocument19 pagesPrusa Igor - Japanese Scandals and Their ProductionIgor PrusaNo ratings yet

- Rebellion of The Poor: South Africa's Service Delivery Protests - A Preliminary AnalysisDocument17 pagesRebellion of The Poor: South Africa's Service Delivery Protests - A Preliminary AnalysisYuni OconNo ratings yet

- Explaining The Resurgence of Regionalism in World PoliticsDocument29 pagesExplaining The Resurgence of Regionalism in World PoliticsВика КольпиковаNo ratings yet

- ARISTFeb28 2010 FinalDocument56 pagesARISTFeb28 2010 FinalPhanicha ManeesukhoNo ratings yet

- King (2008) Sociology of Southeast AsiaDocument14 pagesKing (2008) Sociology of Southeast AsiaDebbie ManaliliNo ratings yet

- Report Media ConglomeratesDocument4 pagesReport Media ConglomeratesMych Chua100% (1)

- Factions, Parties and Politics in A Maltase VillageDocument14 pagesFactions, Parties and Politics in A Maltase VillageAngelica BenitezNo ratings yet

- Civil Society: January 2020Document12 pagesCivil Society: January 2020FelipeOyarceSalazarNo ratings yet

- 3 Politeness in Political Discourse Face Threatening Acts FTAs in American Israel Public Affairs Committee AIPAC SpeechesDocument14 pages3 Politeness in Political Discourse Face Threatening Acts FTAs in American Israel Public Affairs Committee AIPAC SpeechesMariana NecsoiuNo ratings yet

- Presentation FirstDocument19 pagesPresentation Firstmuzafar123No ratings yet

- Civil Becomings: Performative Politics in the Amazon and the MediterraneanFrom EverandCivil Becomings: Performative Politics in the Amazon and the MediterraneanNo ratings yet

- Syria from Reform to Revolt: Volume 2: Culture, Society, and ReligionFrom EverandSyria from Reform to Revolt: Volume 2: Culture, Society, and ReligionLeif StenbergNo ratings yet

- Sociolinguistics Intro WardhuaghDocument12 pagesSociolinguistics Intro Wardhuaghzeyad altairNo ratings yet

- Language and Social ClassDocument28 pagesLanguage and Social Classzeyad altairNo ratings yet

- Preparation EditedDocument178 pagesPreparation Editedzeyad altairNo ratings yet

- DazzlingDocument86 pagesDazzlingzeyad altairNo ratings yet

- كتاب المعلم كيمياء 12ع جزء أولDocument117 pagesكتاب المعلم كيمياء 12ع جزء أولzeyad altair100% (1)

- Critical Discourse Analysis of Selected Newspaper Articles Addressing The Chapel Hill Shooting IncidentDocument21 pagesCritical Discourse Analysis of Selected Newspaper Articles Addressing The Chapel Hill Shooting Incidentzeyad altairNo ratings yet

- مذكرة انجليزي الصف التاسع الفصل الثاني الأستاذ خالد سليمDocument41 pagesمذكرة انجليزي الصف التاسع الفصل الثاني الأستاذ خالد سليمzeyad altairNo ratings yet

- 402 1897 1 PBDocument4 pages402 1897 1 PBzeyad altairNo ratings yet

- مذكره مراجعه 12 رياضيات الاستاذDocument26 pagesمذكره مراجعه 12 رياضيات الاستاذzeyad altairNo ratings yet

- مذكره مراجعه 12 رياضيات الاستاذDocument26 pagesمذكره مراجعه 12 رياضيات الاستاذzeyad altairNo ratings yet

- Phonetics Test - 1Document6 pagesPhonetics Test - 1zeyad altairNo ratings yet

- Al Rashid Indian School Farwaniya Kuwait: English Worksheet Term 1-2020-2021 Grade - VDocument23 pagesAl Rashid Indian School Farwaniya Kuwait: English Worksheet Term 1-2020-2021 Grade - Vzeyad altairNo ratings yet

- Reports Grade 12.2Document3 pagesReports Grade 12.2zeyad altairNo ratings yet

- Math 5-1Document17 pagesMath 5-1zeyad altairNo ratings yet

- Start Date End Date # of Target Days Chapter # Name of The ChapterDocument7 pagesStart Date End Date # of Target Days Chapter # Name of The Chapterravi kantNo ratings yet

- Christmas Dishes From Around The WorldDocument1 pageChristmas Dishes From Around The WorldAngeles EstanislaoNo ratings yet

- Quaid e AzamDocument7 pagesQuaid e AzamFM statusNo ratings yet

- Rajni Vashisht Ashwani TambatDocument10 pagesRajni Vashisht Ashwani Tambatvaibhav bansalNo ratings yet

- Εγχειρίδιο Χρήσης WiFi - EVA - II - Pro - Wifi - 0 PDFDocument16 pagesΕγχειρίδιο Χρήσης WiFi - EVA - II - Pro - Wifi - 0 PDFZaital GilNo ratings yet

- Twelve Angry Men Act 1 Summary Ans Analysis HandoutsDocument5 pagesTwelve Angry Men Act 1 Summary Ans Analysis Handoutsstale cakeNo ratings yet

- Reading Unit 4 Week 3 3 2 2020-3 6 2020Document10 pagesReading Unit 4 Week 3 3 2 2020-3 6 2020api-422625647No ratings yet

- David Copeland-Jackson IndictmentDocument12 pagesDavid Copeland-Jackson IndictmentWashington ExaminerNo ratings yet

- AnsDocument5 pagesAnsSravani RaoNo ratings yet

- Notes Calendar Free Time Displays No InformationDocument17 pagesNotes Calendar Free Time Displays No InformationfregolikventinNo ratings yet

- Welcome To Anderson Workone. Your Career Starts HereDocument28 pagesWelcome To Anderson Workone. Your Career Starts HereHilary TerryNo ratings yet

- SPM Bi Jan RM 4Document6 pagesSPM Bi Jan RM 4lailaiketongNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2 A and MDocument13 pagesLesson 2 A and MDayana ZappiNo ratings yet

- CP16 Risk AssessmentDocument1 pageCP16 Risk AssessmentJulia KaouriNo ratings yet

- My Consignment Agreement PDFDocument3 pagesMy Consignment Agreement PDFtamara_arifNo ratings yet

- Capital MarketDocument16 pagesCapital Marketdeepika90236100% (1)

- A Natural ReactionDocument19 pagesA Natural ReactionRyzeNo ratings yet

- Flipkart Case StudyDocument9 pagesFlipkart Case StudyHarshini ReddyNo ratings yet

- Zhang Ear Accupuncture Rhinititis Cold PDFDocument391 pagesZhang Ear Accupuncture Rhinititis Cold PDFanimeshNo ratings yet

- Codirectores y ActasDocument6 pagesCodirectores y ActasmarcelaNo ratings yet

- Iycf AsiaDocument68 pagesIycf AsiaYahye CMNo ratings yet

- LC Jumpers Fap 203 Web PDFDocument3 pagesLC Jumpers Fap 203 Web PDFAlejandro Humberto García QuisbertNo ratings yet

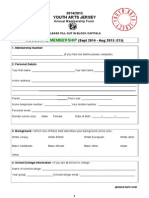

- Youth Arts Jersey - MembershipDocument2 pagesYouth Arts Jersey - MembershipSteve HaighNo ratings yet

- Range CoderDocument11 pagesRange CoderftwilliamNo ratings yet

- Module 9 - Personal Protective EquipmentDocument11 pagesModule 9 - Personal Protective EquipmentSamNo ratings yet

- Journal Date Account Titles Debit CreditDocument9 pagesJournal Date Account Titles Debit CreditFrances Monique AlburoNo ratings yet

Analysis South African Newspapers

Analysis South African Newspapers

Uploaded by

zeyad altairOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Analysis South African Newspapers

Analysis South African Newspapers

Uploaded by

zeyad altairCopyright:

Available Formats

Discourse & Society

http://das.sagepub.com/

Critique Discourses and Ideology in Newspaper Reports: A Discourse

Analysis of the South African Press Reports on the 1998 SADC's Military

Intervention in Lesotho

PULENG THETELA

Discourse Society 2001 12: 347

DOI: 10.1177/0957926501012003004

The online version of this article can be found at:

http://das.sagepub.com/content/12/3/347

Published by:

$SAGE

http://www.sagepublications.com

Additional services and information for Discourse & Society can be found at:

Email Alerts: http://das.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

Subscriptions: http://das.sagepub.com/subscriptions

Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Citations: http://das.sagepub.com/content/12/3/347.refs.html

Downloaded from das.sagepub.com at SOAS London on April 8, 2011

ARTICLE 347

Critique discourses and ideology in newspaper

reports: a discourse analysis of the South African

press reports on the 19 9 8 SADC's military

intervention in Lesotho

Discourse & Society

Copyright 0 2001

SAGE Publications

(London,

Thousand Oaks, CA

and New Delhi)

Vol 12(3): 347--370

[0957-9265

PULENG THETELA (200105) 12:3;

UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD 347-370; 016627]

AB s TR ACT. The present study examines the coverage of the Southern Africa

Development Community's (SADC) military intervention in Lesotho by the

South African newspapers -- how the newspapers articulate conflicting

ideological positions in their reportage of the intervention. Working within the

ideological framework of news production and reception, the article examines

the issue of critique (with emphasis on blame} in these newspapers. Dividing

the news texts into supportive and protest categories (the PINA and AINA,

respectively), the study investigates different perceptions (opinions, feelings,

attitudes, etc.} about South Africa's involvement in the conflict, and how such

perceptions were encoded in the ideologically based discursive patterns (lexical,

metaphorical and intertextual choices). The differences between the newspaper

reports are also seen as establishing two rival social group identities, expressed

through the ideological us versus them binary opposition.

KEY WORDS: AINA, blame, conflict, evaluation, exclusion, identity, intertextuality,

invasion, PINA, SADC, South Africa, text, transitivity

1. Introduction

Much has been written on warfare reporting in media studies (e.g. Hudson and

Stanier, 1997; Young and Jesser, 1997), and linguistic research (e.g. Hackett and

Zhao, 1994; Rojo, 1995), the focus of which has been on major conflicts such as

the Gulf War. This article analyses news discourse, particularly the news reports

in the South African press during the Southern African Community's (SADC)

military intervention in Lesotho. Although the armed conflict never attracted

international media interest, it was a major event in Southern Africa, as it

marked a new role for South Africa (SA) as a major player in the Southern

African sociopolitical and economic situation. The conflict should be seen against

the background of the following:

(i) It occurred towards the end of the first term of office of the first ever demo-

from the SAGE Social Science Collections. AllDownloaded

Rights Reserved.

from das.sagepub.com at SOAS London on April 8, 2011

348 Discourse & Society 12(3)

cratically elected government, after decades of apartheid rule, and only six

months prior to the general election.

(ii) The new SA government had spent its first term engaged in the political,

social and economic restructuring of the country, in order to improve the lives of

the previously disadvantaged black population, a task which had earned the gov-

ernment sharp criticism from both black and white South Africans, the former

complaining of the slow pace of reform, while the latter expressed fears about the

possible discrimination against the white population.

(iii) The intervention was the first foreign military engagement by the newly

transformed SA army, which had incorporated the former liberation armies into

its ranks; and hence had had its name changed from South African Defence Force

(SADF) to the South African National Defence Force (SANDF), to reflect this

transformation. These changes had created bitter rivalry between the black and

white officers, resulting in incidents of mutiny within the army ranks.

(iv) When SA joined the SADC in 1994, the organization structure changed

from being only a development body to that of assuming security powers to pro-

tect democracy in the member states; the Lesotho conflict was the first test of the

SADC's security powers, enshrined in the 1996 Gaborone Protocol.

The above historical and sociopolitical background to the conflict motivated

the study of critique in this article (the term critiquing defined by the Concise

Oxford Dictionary as to 'evaluate in a detailed and analytical way'). Taking the

view that news discourses do not occur in a vacuum, but are products of the

social system within which journalists work, I assumed that the examination of

critique discourses would reveal evidence of the reproduction of the ideologies of

the social system and institutions in SA at the time (i.e. the political and social div-

isions, polarization of opinion, etc.).

The database for this analysis is a corpus of 300 news reports and 19 editorial

sections of newspapers published between June 1998 and April 1999: from the

SA Independent Group newspapers -- The Star, Cape Argus (to be referred to as

CA), Cape Times ( CT) The SA Independent, The Citizen, Business Day (BD) and the

Mail and Guardian (M&G). I divide the reports into two categories: the 'protest' (or

'dissenting') press -to be referred to as the Anti-Intervention Alliance (AINA);

and those which took a 'supportive' (or 'collaborative') stance - the Pro-

Intervention Alliance (PINA); the term alliance is used very loosely to refer to

shared sociocultural values.

2. A brief history of the military intervention

The military intervention in Lesotho took place on 22 September 1998, after all

attempts by the SADC to find a peaceful solution to the Lesotho political crisis had

failed. The crisis was a result of the Lesotho opposition parties' rejection of the

results of the 23 May 1998 general elections, which they claimed had been

rigged in favour of the ruling party. When the SADC Commission of Inquiry, set

up to investigate the opposition allegations, failed to find evidence of fraud, the

Downloaded from das.sagepub.com at SOAS London on April 8, 2011

Thetela: Critique discourses and ideology 349

opposition refused to accept the verdict, and instead turned to the army for sup-

port. This culminated in an attempted military coup, the situation that prompted

the SADC military intervention. The SADC force, which was led by SA, was made

up of the SANDF and the Botswana Defence Force (BDF).

3. Theoretical framework

The study of the production and reception of the news media has been a widely

researched area in linguistics. While some studies have focused on lexicogram-

matical patterns of news reports (e.g. Bagnall, 1993), others have concentrated

on larger discourse patterns (e.g. Van Dijk, 1988a, 1988b; Bell, 1991); yet other

studies (e.g. critical linguistics) have focused on even broader concerns such as

ideology, and various sociocognitive dimensions of news production and

interpretation (e.g. Kress, 1983; Fowler, 1991; Hodge and Kress, 1993; Van Dijk,

1995, 1996). Linguistic studies of the news media have profited from the influ-

ence of the social sciences -the economic, political, social and psychological

aspects of news processing -- these providing 'important insights into the (macro)

conditions of news production and into the uses or effects of mass media report-

ing' (Van Dijk, 1988b: 1). The present study thus derives its theoretical under-

pinning from this interdisciplinary approach; particularly the ideological

framework articulated in Van Dijk (1992, 1995, 1996, 1998); Fowler (1991),

andFairclough(1989, 1992, 1995).

IDEOLOGIES IN THE NEWS

Since news texts are social practices (i.e. they represent the views and actions of

certain social classes or groups), they are subject to the social constraints and

institutional relations within which journalists operate ( Curran and Seaton,

1988; Van Dijk, 1996). The news is not only reported, but it is also interpreted,

and interpreting any event, 'involves the beliefs, opinions, hopes, and aspirations

of those gathering, reporting, and publishing the news', and in that process,

'ideology inevitably co-determines what gets reported, when it is reported, and

how the reporting is done' (Verschueren, 1985: 3). The analysis of news reports in

this study is broadly based on the theoretical framework of ideology defined below:

Ideologies are basic frameworks of social cognition, shared by members of social

groups, constituted by relevant selections of sociocultural values, and organized by

an ideological schema that represents self-definition of a group. Besides their social

function of sustaining the interests of groups, ideologies have the cognitive function

of organizing the social representations ( attitudes, knowledge) of the group, and thus

indirectly monitor the group-related social practices, and hence also the text and talk

of its members. (VanDijk, 1995: 248)

The above framework enables us to investigate and account for discursive pat-

terns of critique, and then speculate on how such patterns function as represen-

tations of the ideologies of social groups within whose midst the news reports

were produced.

Downloaded from das.sagepub.com at SOAS London on April 8, 2011

350 Discourse & Society 12 (3)

NEWS VALUES AND EVALUATION

Research on media studies has shown that not every event reaches the news

columns but that journalists use a paradigm of news values (e.g. frequency,

meaningfulness, threshold, consonance, etc.) to decide on which event is more

newsworthy than others (e.g. Hartley, 1982; Bell, 1991). Decisions on news wor-

thiness also influence linguistic choices in the news: the structure and content of

the headline or lead stories, propositional structures, lexical patterns and other

levels of discourse. Structurally, news stories have also been seen to follow certain

schematic patterns of various genres, such as Labov's ( 19 72) narrative structure,

in which evaluation is seen as an integral part of storytelling, to establish the sig-

nificance of what is being told, focus the events, and justify claiming the audi-

ence's attention ( see Bell, 19 91: 152). The present analysis sees critique

discourses as one particular form of normative judgement on human behaviour,

expressed in 'moral comments or demonstrations of the way the world is, the way

the world ought to be, what proper behaviour is, and the kind of people that the

speaker and addressees are' (Linde, 19 9 7: 153). This study, therefore, investigates

how sociocultural values ( either universal or group values) are integrated into

the news through journalistic choices of the language code - the preference of

certain meanings against a host of other possible meanings.

INTERTEXTUALITY AND CONSENSUS

The study also recognises that news texts have a special value of incorporating

linguistic elements of various kinds from one text type to another or from one

socially situated discourse type to another -- the property often referred to under

the general topic of intertextuality (e.g. Bakhtin, 19 81; Fairclough, 19 8 9, 19 9 2;

Candlin and Maley, 199 7). The intertextual practices of the news stories are real-

ized through the incorporation of interpersonal styles, which organize the news

into persuasive and argumentative construct, and also build the assumption of

consensus, making the news as an agreed notion of unity. Consensus ( discussed

in detail in, for example, Hartley, 19 8 2; Herman and Chomsky, 19 88) is under-

stood here as a set of shared beliefs 'that a society shares all its interests in

common, without division or variations' (Fowler, 1991: 16), the ideology which

is the source of the consensual 'we' pronoun commonly used in political dis-

courses. In this study, therefore, we look at the discourse roles of bringing frag-

ments of discourse from interpersonal discourses, such as oral models

(conversation and narrative structures), and polyphonic practices (incorporation

of multiple voices) into the construction of news stories.

4. Discourse analysis

The analysis of news reports in the study is that of rhetorical patterns

of discourse semantics: the propositional patterns, illustrated through transi-

tivity choices, lexical structure and metaphorical expressions. Critique is also

expressed through the intertextual practices of the news reports --the oral models

Downloaded from das.sagepub.com at SOAS London on April 8, 2011

Thetela: Critique discourses and ideology 351

(e.g. conversational and narrative patterns) and attribution strategies for the

incorporation of newsmakers' voices in the construction of the news stories.

4 .1 TRANSITIVITY CHOICES

In discourse, the content, participants and semantic roles are largely constructed

through language: they are derived from 'the meanings of the discourse associ-

ated with the institutions relevant to the production and consumption of the text'

(Fowler, 1991: 70). It is from this perspective that I investigate the different per-

ceptions of the intervention between the PINA and AINA press, based on choices

from the system of transitivity, a part of the ideational metafunction of language,

which explores differences in meaning between various types of processes (e.g.

Halliday, 1994; Eggins, 1994). This analysis has been widely used by critical lin-

guists to show how newspapers provide abundant examples of the ideological sig-

nificance of transitivity in the study of meaning (e.g. Kress, 1983; Fairclough,

1989; Fowler, 1991; Van Dijk, 1995). In this article, the analysis is applied to

newspaper headlines, the choice of which was motivated by their crucial role in

meaning: as macropropositions, they encapsulate the news stories, and attract

the reader to the story (e.g. Fairclough, 1992; Nir and Roeh, 1992). Given the fact

that they are constructed by news editors after the stories have been written (e.g.

Reah, 1998), news headlines function as opinion manipulators, and are thus

good candidates for the study of the newspapers' ideological positions. For this

analysis, only three of these processes found in our data - the material (processes

of doing), relational (being) and verbal (saying)- are discussed.

Material processes Since the M&G, carrying the highest percentage of the AINA

reports, reported events on the battlefield (e.g. who was doing what to whom), the

majority of their headlines were constructed as material processes.

1. SA forces butcher sleeping Lesotho soldiers at Katse Dam (CA, 12 Oct. 1998).

2. SA abandoned the moral high ground among the mountains ( CT, 1 Oct.

1998).

3. More than 100 die in Lesotho misadventure (CA, 15 Oct. 1998).

4. Was Lesotho sacrificed to appease Mugabe? (M&+G, 12 Oct. 1998).

The semantic definition of a material process is that some entity is doing some-

thing, or undertakes some action. In a material process, the entity or participant

responsible for the process is described as agent (or actor), for example, 'SA forces'

in the first headline (1), 'SA in (2) and 'more than 100' in (3). The actions, on the

other hand, can either be concrete, physical actions (e.g. 'butcher' in [1] or

abstract happenings (e.g. 'abandon the moral high ground' in [2]). While in (1)

the agent is represented as actively responsible for the process, in (2) and (3) the

relationship between the agent and the process is not causative, as both agents

are mere participants in processes over which they have no control. Processes

(irrespective of type) can either be confined to the agent or be extended to other

participants: 'butcher' in (1), for example affects 'sleeping Lesotho soldiers',

Downloaded from das.sagepub.com at SOAS London on April 8, 2011

3 52 Discourse & Society 12 (3)

referred to, in material terms, as patient or goal (the participant suffering the

process). The difference between a confined process in ( 3) and extended one in ( 1)

can be explained through the theory of ergativity (e.g. Halliday, 1994: 163 ff;

Manning, 1996), the discussion of which falls outside the scope of the present

article. In addition to the two obligatory components of any process ( the partici-

pant and the process itself), the clause may choose a third component- the cir-

cumstantial element ( with the same functions across processes) to represent, for

instance, either the location of an event (e.g. 'at Katse Dam' in [l]), the cause of

a process (e.g. 'to appease Mugabe' in [4]), or the manner in which the process is

carried out (e.g. 'satisfactorily').

While transitivity roles are semantic in nature, they can also be impacted upon

by syntactic transformations. While the latter do not necessarily affect the type of

process, they can bring other dimensions of meaning to the discourse. Unlike the

first three headlines, for example, ( 4) is a passive construction, in which the

patient (Lesotho) is in subject ( or thematic) position; and although the verb struc-

ture, 'was sacrificed' has a feature of agency (i.e. we could ask 'who by'?), the

identity of the agent is not revealed in the headline, thus placing the prominence

of the message on the patient and the action suffered.

The preference of abstract happenings as material processes mentioned above

has a very powerful evaluative function. The choices of frequently used verbs by

the M&G and the CA, such as 'botch' and 'blunder', for example, ( as in 'SA botches

the invasion' and 'Yet again, Pretoria blunders', respectively), do not necessarily

tell us about concrete events, but about the headline writer's interpretation and

evaluation of events. The verb 'butcher' in (1), also shows that since headline

stories are also opinion manipulators, even the choice of concrete actions carry

evaluation -in addition to saying what happened, the verbs also evaluate the atti-

tude of the agent to the patient. Thus while 'butcher' normally refers to the

slaughter of animals, its use with reference to human beings carries negative

connotations of cruelty and brutality.

Relational processes These processes encode the meaning of 'being' something is

being said to be something else: either something has a certain quality ascribed to

it (attributive) or something has an identity assigned to it (identifying). Headlines

(5) and (6) below (note that due to the typical telegraphic syntax of headlines, the

verb 'is' in square brackets was absent in the original) illustrate the two types of

relational processes.

5. SA [is] wrong to interfere in Lesotho conflicts ( CA, 13 Oct. 19 9 8).

6. SA's military intervention [is] a mistake (CA, 26 Sept. 1998).

In almost all the relational process headlines, SA was positioned as a major par-

ticipant, and assigned negative attributes and identifying qualities, for example,

the attribute 'wrong' in (5), and the identity 'a mistake' in (6). Attributes and

other qualities can be ascribed to an entity in structures other than the verb 'is'.

A good example is that of the verbs 'cost' and 'deserves' in 'Lesotho Foray cost SA

Downloaded from das.sagepub.com at SOAS London on April 8, 2011

Thetela: Critique discourses and ideology 353

R8 million in first week' (The Star, 12 Oct. 1998) and 'Pretoria deserves world-

wide condemnation for Lesotho fiasco' (M&G, 26 Sept. 1998), respectively, in

which the verb was carried by the circumstantial element, and the attribution by

the nominal group (see Halliday, 1994: 131 ff, for a discussion on circumstantial

processes).

Verbal processes The choice of verbal processes can be seen as one of the distin-

guishing features between the two categories of reports. Unlike in the AINA

reports, the majority of PINA headlines were verbal processes -reporting

speeches by elite people, particularly, government ministers and military officials.

Most of these headlines were found in The Star.

7. Mandela defends military action as coup prevention (The Star, 28 Sept. 1998).

8. Nyanda slams media over distorted Lesotho coverage (The Star, 12 Oct. 1998).

9. Mbeki denies claims about SANDF's botch up (The Star, 29 Nov. 1998).

In these verbal reports, the individual ministers (mentioned by name) are

assigned agency roles (sayer in verbal process terms), whereas other participants

are either receiver (or target) of the process, such as 'media' in (8) or (a part of) the

verbiage (the latter refers to a nominalized statement of the verbal process, such

as 'claims' in [9]). The most common choices of speech verbs in the headlines are

performative verbs (e.g. 'defends', 'slams' and 'denies' above), which characterize

the elite people as speaking from some positions of power through saying cer-

tain things they are also performing certain actions (see, Austin, 1962 on speech

acts). The choice of naming the ministers, as opposed to institutions such as 'gov-

ernment' or 'army', for example, appears to give a human face to institutional dis-

courses, such that the reader identifies with these discourses; thus the headline

stories evoke feelings, such as empathy, patriotism and other human feelings. It is

also worth pointing out that these verbal processes are coded in the present tense,

thereby adding the quality of urgency and relevance to the story, and situating

the message in the here and now.

It should be mentioned that at the height of the conflict when the government

was making use of both the broadcast and press media to rally public support,

papers such as the M&G and CA published response articles the purpose of which

was to counteract what the papers referred to as 'lies' and 'malicious propaganda'

by the government to 'mislead the public'. This was done through the incorpora-

tion of voices from selected sources (e.g. opposition parties, church leaders and

other interest groups), whose versions of events contradicted official ones. Many

of these reports chose verbal process headlines, with the selected sources almost

invariably in agency positions.

(10) Churches and peace bodies take SA to task over incursion (CA 30 Sept.

1998).

(11) Lesotho spin doctor slams SA invasion and lies (CA, 2 Oct. 1998).

(12) SA condemned for cold-blooded murder in Lesotho (M&G, 12 Oct. 1998).

Downloaded from das.sagepub.com at SOAS London on April 8, 2011

354 Discourse & Society 12(3)

The point worth noting here is that in the AINA verbal process headlines, the gov-

ernment (represented through place for institution metonymy, 'SA') was either

omitted from the headline or its role reduced to that of either receiver or (part of)

the verbiage things were either said to (e.g. [12]) or about (e.g. [11]) the gov-

ernment.

The analysis of transitivity above has indicated how, through choices from the

lexicogrammar, certain semantic roles and relationships are reproduced in the

ideologically constructed discursive practices. For example, the choice of SA in

material processes indicated the AINA's perception of the farmer's cruel and other

negative activities. Through positioning of participants and process choices, and

their positioning in the clause, we could reasonably speculate on the ideologies of

the news reports.

4. 2 LEXICAL STRUCTURE

Lexical choices have always been seen as very crucial in the construction of

meaning. They 'mark off socially and ideologically distinct areas of experience'

(Fowler, 1991: 84), and therefore have a categorizing function. In our data, these

choices were the most explicitly distinguishing feature between the PINA and the

AINA, particularly in naming ( or labelling) certain entities. Several studies have

shown labelling as an ideological decision, the most well documented example

being that of the difference between 'freedom fighter' and 'terrorist' (e.g. Kress,

1983; Van Dijk, 1995; Clark, 1998). In the present study, we use similar ideo-

logical considerations to describe the labelling strategies of the SA press.

In the first two days of the war, the unexpected high rate of casualties among

the SANDF soldiers, resulted in heightened tensions and polarized opinions

among the SA public, with many calls for the immediate withdrawal of the SA

troops. These tensions could be seen to have accounted for many terms used to

refer to the human participants the SA government, the SADC, Lesotho, and the

critics -and the events. We start by looking at the use of the terms intervention

and invasion, which dominated parliamentary debates and broadcast interviews

(and were later picked up by the press), with reference to the conflict.

Pl: It was intervention, not an SA invasion (The Star, 6 Oct. 1998)

It is similarly erroneous to blame South Africa for the fact that the people of Lesotho

went on a rampage, looting the centre of Maseru. The fact that these activities took

place concomitantly with the military intervention shows that underlying social ten-

sions had reached a point of no return. It is also not correct to endorse the perception

that the SADC had invaded Lesotho, because our military intervention was repeatedly

requested by Lesotho's own government.

The above statement was attributed to a government minister in a report defend-

ing the government's position. In this extract, there is a juxtaposition of the two

terms, in the headline and the main text. In the former, the preferred term, inter-

vention, occurs in the main clause, whereas the second and minor clause intro-

duces the dispreferred term though a negation 'not'. The positioning of the

former term in the main clause gives the message some prominence. The purpose

Downloaded from das.sagepub.com at SOAS London on April 8, 2011

Thetela: Critique discourses and ideology 355

of the main text can be seen as the justification of why one and not the other term

is appropriate. In the last sentence, for example, although invade comes before

intervention, it is introduced through the negative 'it is also not correct...' after the

reason for its inappropriateness (i.e. 'because') is given. It is worth noting that the

use of these terms in the SA press are suggestive of the opinions that the users

had - with invasion perceived as indicating violence whereas intervention had posi-

tive connotations of peace and mediation.

The context provided in (P 1) above can be used to explain the frequency of the

use of some labels and not others by either the support or protest media. Using

references to the conflict again as an illustration, I collected the labels from all the

papers, arranged them into groups on the basis of synonymy, and then catego-

rized the groups under broad senses that each group seemed to carry (see Al and

P2 below).

(Al) AINA Labels

(i) Conflict as a mistake and/or military failure: 'a terrible mistake', 'clumsy interven-

tion', 'ill-conceived operation', 'the Lesotho debacle', 'dreadful error', 'inept handling

of a complex situation', 'ill-fated intervention', 'the Lesotho misadventure', 'the

Lesotho botch-up', 'an exercise of futility', 'SANDF disaster', 'blunder', 'the Lesotho

shambles', 'SANDF fiasco', 'mayhem', 'mess'.

(ii) Conflict as violent, illegal and/ or immoral: 'invasion', 'ultimate occupation', 'naked

aggression', 'chauvinistic expansionism', 'bully-boy tactics', 'the Rambo nation

approach', 'devilish and bloody invasion', 'cold-blooded murder', 'merciless butcher-

ing', 'illegal occupation'.

(P2) PINA Labels

(iii) Conflict as successful: 'an unqualified success', 'a resounding victory for democracy

and transparency' and 'a triumph for peace', 'a milestone in regional cooperation',

strike a blow for freedom and peace'.

(iv) Conflict as legal and morally justified: 'intervention', 'a noble purpose', 'a vindica-

tion of the initiative of peace-loving African countries', 'a noble sacrifice for peace', 'a

repayment of SA's moral debt', 'a cleaning up of the scourge of coups', 'a liberation of

democracy', 'an attempt to heal the cancer of corruption', 'a wake-up call to an

African Renaissance'.

The categorization indicates a selection of labels by each category, based along

distinct parameters of value -success, peace, legality and morality. The choices in

(i) and (ii), make the AINA's negative perception clear- all these labels carry nega-

tive evaluations: thus the war is perceived as a mistake - unsuccessful, confused,

illegal, violent and immoral. This view conflicts with that of the PINA, in which

the selected labels carry the meanings of success (iii) and legality and morality

(iv). The fact that each category chose labels from the opposite poles of the

good-bad evaluation continuum could be seen as a powerful ideological tool and

a pointer to the ideology of the news reports concerned.

4. 3 THE METAPHOR SYSTEM AND MORALITY

Choices from the metaphor system also indicated the differences between the

Downloaded from das.sagepub.com at SOAS London on April 8, 2011

356 Discourse & Society 12(3)

PINA and AINA press. We examine the use of a distinct group of metaphors

which were used extensively in the press - that of morality - the categorization

broadly based on Lakoff's (1996) view that our metaphorical system is grounded

in our experiential logic of material of well-being (e.g. health, happiness, wealth,

freedom, etc.). An attempt is made to characterize three categories of morality

metaphors (i.e. moral accounting, purity and health), examine the logic behind

their use, and then speculate on their role in critique.

Moral accounting These metaphors are based on our conceptualization of moral

well-being as wealth, the logic of which is rooted in our everyday experience in

which wealth serves as a strong basis on which sociocultural values are based.

We refer to, for example, 'a wealth of information' as a positive value, and 'moral

bankruptcy' as negative. Moral accounting values rely very heavily on the prem-

ise that if someone does something good to you, you are morally 'in debt' to that

person-you 'owe' him/her something, and it is morally right to honour the debt.

In the SA press, these values were represented by the lexical register of financial

transactions: for example, 'owe', 'pay'/'repay'. 'gain'. 'cost', 'loss', 'price', and

similar expressions.

P3: Buthelezi: Petty carping about Lesotho is wrong (SA Independent, 7 Oct. 199 8)

A military intervention is always an extreme, costly and painful action. However, in

this country we have learnt that freedom and liberty always come with a heavy price

tag. I think people should be proud that South Africa, along with other SADC coun-

tries, has chosen to pay this price to protect the freedom and liberty of the people of

Lesotho who, otherwise, today would have been under the yoke of a military junta,

with the possibility of more casualties.

The moral accounting metaphors in the SA press could be seen as based on the

concept of historical, economical and sociocultural relations between Lesotho

and SA. First, Lesotho (which is a small country completely surrounded by SA)

played a major role during the struggle against apartheid (e.g. harbouring SA

exiles, most of whom received higher education and/or military training there).

Second, the country is economically dependent on SA (e.g. the Basotho form a

substantial percentage of SA's workforce, and both countries use the same mon-

etary system). Finally, Sesotho (the language of Lesotho) is one of the major and

official languages of SA, and the people in both countries have families on either

side of the border.

In the PINA press, most moral accounting metaphors were found in statements

attributed to the government and its allies, in the discourses in which SA's involve-

ment in Lesotho was defended. While in ( 3) above, there was an admission that

the intervention was costly (e.g. 'a heavy price'), thus undesirable, the surround-

ing discourse, however, suggests that positive values (e.g. freedom and liberty) are

difficult to achieve, and thus demand sacrifices (e.g. they 'always come with a

heavy price tag). Many PINA reports such as this therefore justify SA's involve-

ment in Lesotho as a sacrifice worth making for the restoration of democratic rule

in the latter. In this manner, S.A's intervention was seen as the repayment of S.A's

Downloaded from das.sagepub.com at SOAS London on April 8, 2011

Thetela: Critique discourses and ideology 357

moral debt to the Basotho. Obviously the AINA did not share this view. To this cat-

egory of papers, the intervention was immoral, and therefore undesirable. The

same metaphorical choices were, therefore, used to show the negative effects of

the war. For instance, the term 'cost' as in 'South Africa's botched military inter-

vention has cost it dearly in terms of its good neighbourly relations with Lesotho'

( CA, 15 Oct. 19 98) expresses a negative image. This is so even of positive

metaphorical expressions such as 'gain': SA's actions were said to have gained the

country 'enemies locally and abroad', a 'bad reputation', and similar negative

attributes.

Moral purity This category is based on the logic of moral essence: society sees

moral purity in terms of purity and cleanliness, whereas immorality 'is concep-

tualized as something disgusting, dirty, and impure' (Lakoff, 1996: 262). In the

SA press, immoral behaviour was conceptualized in terms of human waste ( e.g.

'excrement', 'excreta', 'shit', etc.) and environmental pollution (e.g. 'pollution',

'filthy', mess', 'dirty', 'dereliction', etc.). The two texts, (A2) and (P4) can be used

to compare the AINA and PINA use of moral purity metaphors.

A2: Now find a way out of the mess (M&G, 1 Oct. 1998)

When 'good intentions' land you belt-high in excrement with nothing firm underfoot,

it is probably best to delay wondering what persuaded you to walk into it. Self-

flagellation can come later. Now it is time to plan a way out -So that you emerge as

dry as possible, preferably alive and with your dignity intact.

P4: Defending regional democracy (The Star, 14 Oct. 1998)

As in many West African countries, the goddess of coups has deposited her poisonous,

imperishable excreta in the caves of the mountain kingdom, so that Maseru in particu-

lar now stinks with abomination.

The report (A2), one of the M&+G's response articles to official government broad-

cast statements, appeared the morning after the deputy president's address to the

nation in which he had emphasized SA's 'good intentions' for intervening in

Lesotho. In addition to using the term 'mess' in the headline to show disapproval

of the government's actions, the deputy president's concept, 'good intentions' is

placed in quotation marks, and also positioned in the clause in agent role, with

the government (referred to as 'you') as the beneficiary of this immoral action (i.e.

'land ... belt-high in excrement').

A similar metaphor 'imperishable excreta' is used in (P4), which, although

expressing the same meaning, is aimed at a different target. Here the metaphor of

excrement derives from the SA black culture's logic of moral essence, used in folk-

lore, curses and proverbial expressions, to describe immoral behaviour. For

example, there is a Sesotho proverb 'Do not defecate in a cave' (literal translation),

which is based on folklore accounts of caves as shelters against rains and thun-

derstorms by travellers on foot or horseback. In such stories, leaving faeces in a

cave meant corrupting the shelter, making it unusable for other travellers. In this

way, the writer (who is a black SA journalist) exploits the cultural meaning of

Downloaded from das.sagepub.com at SOAS London on April 8, 2011

358 Discourse & Society 12(3)

excrement and smell (i.e. 'stinks with abomination'), and the personification of

this immoral behaviour as 'the goddess of coups' responsible for the disintegra-

tion of democratic values in Lesotho.

The press also used positive values in their news stories, which were realized

through images of cleanliness. In (A2) above, for instance, getting out of the

'mess' was seen as the equivalent of 'emerging' from the excrement 'as dry as

possible'. The report made specific recommendations on how SA could reclaim its

moral integrity: the immediate withdrawal of SA troops from Lesotho, apologiz-

ing to the Basotho, and helping rebuild Lesotho's economy. For The Star, in par-

ticular, since the purpose of the war was to return Lesotho to democratic rule, it

was seen as a necessary tool for the achievement of moral purity. Further down

the text in (P4), the war is described as 'an eloquent statement that rather than

hold our heads in our hands ... Africa may now be on the road towards cleaning

its own mess' (The Star, 14 Oct. 1998); and in another story as 'the clean up of

the riff-raff so the seeds of stability will germinate and flourish' (The Star, 6 Oct.

19 98), in which the eradication of the coup plotters (i.e. the 'riff-raff') is seen as

enabling the 'germination' and 'flourishing' of seeds of stability, and therefore

implying Lesotho's (or Southern Africa) return to democracy.

Morality as health Several critical linguistic analyses have commented on

metaphorical representations of social problems as diseases in news reports. It

has been argued, for example, that disease metaphors 'tend to take dominant

interests of society as a whole, and construe expressions of non-dominant

interests (strikes, demonstrations, "riots") as undermining (the health) of society

per se' (Fairclough, 1989: 120). In the same way as moral purity, the majority of

disease metaphors were found in the PINA press, in which dissent was dismissed

in disease terms.

P 5: Put the blame on the real culprits (The Star, 2 Oct. 199 8)

Unfortunately a lot of commentary one hears on the Lesotho crisis does not credit the

South Africans for their effort in treating this bleeding ulcer. Those who allow them-

selves to be contaminated by the hysteria being spread by the likes of the Gauteng radio

station might consider this: that radio station did not even cover the Lesotho elections

in May.

The attack on the media by government and its allies, in particular, was a result

of what was seen as partisan reporting (illustrated in verbal process headlines

above). In (P5), for example, the Gauteng radio station was criticized for lack of

patriotism seen in its special interviews with the Lesotho opposition leaders and

anti-war demonstrators. Its behaviour is thus described in disease terms: instead

of supporting good values, expressed by the metaphor of healing (i.e. 'treating' a

'bleeding ulcer'), the radio station 'spreads' 'hysteria' which is seen as dangerous

to (i.e. it can 'contaminate') society's moral health. Similar attacks on the critics

were lexicalized in metaphors such as 'endemic', 'infected', 'epidemic' and

'cancer', all used to refer to treacherous and unpatriotic behaviour.

From our discussion of the three categories of morality metaphors above, we

Downloaded from das.sagepub.com at SOAS London on April 8, 2011

Thetela: Critique discourses and ideology 359

are presented with an interesting phenomenon of blame discourses in which

each category of reports purports to represent mainstream social values. The

morality metaphors appear to manipulate public opinion through appeal to

human feelings such as pity, empathy, disgust, anger, outrage, and so on. By cat-

egorizing the targets of blame as lacking moral values, the metaphors can be seen

to breed exclusion practices in which one group is positioned in discourse as

deviant and thus a danger to mainstream sociocultural values ( exclusion is dis-

cussed later in the article).

4.4 INTERTEXTUAL PRACTICES

Much of the critique in the news text under discussion appears to be carried in

the intertextual patterns of the news discourse. First, critique is expressed

through the incorporation of discourses deriving from oral models (e.g. conver-

sational and narrative discursive patterns), and also through attribution strat-

egies used to bring multiple voices from outside the newsroom into the

journalistic constructions of the news stories.

CONVERSATION

The conversational styles of communication used by newspapers is well docu-

mented in research, and often referred to through terms such as the 'public

idiom' (Hall, 1976; Fowler, 1991) or the 'vox pop' (Hartley, 1982). This style,

through which social values are reproduced in the discursive interaction between

the newspaper text and the reader, is an important source of neutral language

that embodies 'moral' values, and creates 'an illusion in which common sense is

spoken in matters on which there is consensus' (Fowler, 1991: 47).

The press employed an informal and casual style, which mimicked features of

face-to-face conversation. Among these were deictic expressions such as 1st and

2nd person pronominal references ( e.g. 'I', 'we', 'you', 'our government', 'our sol-

diers'), mostly found in appeal to common sense and 'one nation' SA by all sec-

tions of the media. The style is also realized by other rhetorical features:

contractions (e.g. 'we can't and won't sit back'), colloquialisms, slang words and

rhetorical questions. One feature of conversation found in the data is that which

could be called 'journalist invented dialogue' - where a story is presented through

embedded dialogue.

A3: Enter Big Brother SA to a baptism of blood and fire: Lesotho sees our

tough side (CA, 29 Oct. 1998)

Before yesterday, southern Africa had bleated about Big Brother every time South

Africa tried to assert itself; ultra-sensitive to the charge, South Africa backed off every

time. Now it has said, in effect, if you brats can demonstrably not sort out your squabbles,

Big Brother will have to do so.

In journalistic dialogue, we find a replication of speech, without any linguistic

signal on whether the speech was actually made, and in many cases, there is no

source, suggesting that it is the writer's own invention. In (A3), for example, we

see an interplay between simple narration and dialogue: first, the headline

Downloaded from das.sagepub.com at SOAS London on April 8, 2011

360 Discourse & Society 12(3)

consists of two clauses in appositive relationship, with the initial clause in dia-

logue form and the second in narrative form. Thus, the second clause can be seen

as having an equal meaning status with the first (i.e. it can mean 'in other

words'). Thus SA is represented as having said something about its neighbours.

Both examples are negative evaluations of SA's oppressive behaviour (seen as a

'Big Brother' attitude) towards its neighbours - treating them as badly behaved

children (i.e. 'brats') involved in noisy quarrels (i.e. 'squabbles'). It is worth noting

the differences between headlines and main texts: in the former, the unspecified

source appears to address directly the unspecified target (e.g. The Star's headlines

such as 'Put the blame on the real culprits' and 'Put up, or shut up'); in the main

text, the dialogue is attributed to SA through reporting (e.g. the M&G's remark,

'South Africa was looking for an excuse to flex its military muscle and to say, 'I am

the biggest in the region'). In the latter use, SA's activities are negatively evaluated

through verbal processes, in which SA ( or government) is in sayer role, thus put-

ting words into SA's mouth, for the purpose of discrediting her.

NARRATIVE MODELS

The news discourses also showed the presence of lexical devices from the narra-

tive models. Such devices are examined through 'cueing', the process which

implies that 'a model of register or dialect or mode can be assigned to a text even

on the basis of some very small segment(s) within its total language' (Fowler,

1991: 61). As has already been seen in (A3) above, the term 'Big Brother' (which

has origins with reference to the oppressive head of state in George Orwell's 1948

novel, Nineteen Eighty-Four), was used as a negative evaluation of SA's arrogant

behaviour. Terms such as this, stood out from other lexical choices, both ortho-

graphically (i.e. they were capitalized), and also they were characteristic of

extremely hostile reports which made no pretence at objectivity.

Another term used in our data is that of 'Rambo', found in seven reports from

the M&G and two from the CA. This term, originating from the name of a hero of

David Morrel's novel, First Blood has been used in international warfare report-

ing. Fowler (1991: 115), for example, found it used in the criticism of the US and

UK's actions in Libya in 19 8 6, where the Guardian evaluated Margaret Thatcher,

as 'Rambo's daughter', and the Sun referred to Ronald Reagan as 'Rambo

Ronnie'. In one report, the M&G (09 Oct. 1998) refers to SA's policy on Lesotho

as the 'Rambo nation approach', where the evaluative weight of the term is made

even stronger by its satirical dimension. For example, it has a homophonic

relationship with the term 'the Rainbow Nation' introduced by President Nelson

Mandela in his first presidential address in 1994, to mark the emergence of the

new democratic society, with positive values such as political reconciliation and

racial harmony. Thus, evaluating SA's foreign policy as the 'Rambo nation

approach' can be seen as undermining the positive values, which the original

concept, 'the Rainbow nation', stood for.

Another interesting cue is that of the mirror analogy in (A4) below derived

from from the well-known children's fairy tale, Snow White.

Downloaded from das.sagepub.com at SOAS London on April 8, 2011

Thetela: Critique discourses and ideology 3 61

(A4): Mirror, mirror, on the wall ... (M&G, 2 Oct. 1998)

On the present evidence, if we were to hold a mirror to ourselves, the image with

which we are likely to be confronted is a pale reflection of all that we decry in the face

of the Ugly American: a regional giant lured into hypocrisy by arrogance born of the

trappings of power.

The report from which the extract was taken was highly critical on the govern-

ment's arrogance in dealing with criticism by the opposition. Using both the

chorus for the headline, and adding an additional myth of 'the Ugly American'

(from Lederer and Burdick's 1958 book) in the main, the report is intended to

provide a vivid negative image of the SA government.

Through cues from the narrative model paradigm above, we can conclude that

the analogies above call up the reader's knowledge of this paradigm, so that the

values associated with narrative models are successfully transferred into the

news stories to describe values of the social system of a different historical and

sociopolitical era.

NEWSMAKERS' VOICES AND DISCOURSE REPRESENTATION

News reports are stories by newsmakers, who are either witnesses to facts, sup-

plying the journalist with information, or 'news actors' (the term used in Bell,

1991) whose utterances have news value (e.g. politicians, sportsmen, etc). The

newsmaker's voice is usually brought into the story through the process of attri-

bution, the newspapers 'evoke fragments of discourse outside the text either to

show agreement with them, because they are considered transcendental, or to

criticize them or discredit them' (Rojo, 199 5: 54). For our purpose we look at how,

in the process of giving them voice, the newsmakers are characterized and per-

sonalized in the discourse - how their voices are positioned within the text both

in relationship to the journalist and to the broader sociocultural practice.

In the data, there were differences in the individual papers' coverage of similar

events, particularly the treatment of their newsmakers' voices. To illustrate this,

we begin by looking at fragments of two reports on the SA deputy president's

opening speech at a conference on African Renaissance' by The Star (P 7) and the

M&G (A6), and later use fragments from other texts.

(AS) Mirror, mirror, on the wall ... (M&G, 2 Oct. 1998)

[4] Thabo Mbeki made it clear once again at the 'African Renaissance' shindig at

Fourways this week, that loyalty was the standard by which actions in regard to

Lesotho would be judged.

[ 5] Critics of the Lesotho misadventure, he suggested, nurse 'hatred for the forces of

genuine change on our continent'; they 'virtually approve of a coup d'etat in Lesotho

against an elected government, proclaim criminal arson and looting in Lesotho as an

heroic act of resistance, denounce a humane approach by the region's armed forces

which minimised the loss of life, and prostitute the truth in the process, with gay

abandon'.

[6] What rubbish! If ever there was an enemy of change on the continent it is those

who insist on resorting to military action to resolve political problems ....

[8] The proclamation of 'criminal arson and looting' as a 'heroic act of resistance'

Downloaded from das.sagepub.com at SOAS London on April 8, 2011

362 Discourse & Society 12(3)

involves an exercise in sophistry with which the ANC itself, rather than its critics, is

more recently familiar. The 'humanity' of our intervention with armed forces is diffi-

cult to discover amid the tears of the bereaved. And if there has been a prostitution of

the truth the 'streetwalkers' of the analogy are more likely to be found pimping

themselves in alcoves of patronage along the corridors of power than out in the

streets.

P7: Mbeki slams critics of Lesotho intervention (The Star, 12 Oct. 1998)

[1] Deputy President Thabo Mbeki yesterday dismissed critics of South Africa's inter-

vention in Lesotho as opponents of change, and asserted that Africa would not realise

a renaissance until it banished the 'cancer' of corruption from the continent.

[2]Speaking at a conference on the African Renaissance in Johannesburg, he lashed out

at unspecified critics of the Lesotho intervention for 'their hatred for the forces of gen-

uine change on our continent and their determination to defeat us'.

[3] 'You will see these judges virtually approve of a coup d'etat in Lesotho against an

elected government, proclaim criminal arson and looting in Lesotho as an heroic act

of resistance, denounce a humane approach by the region's armed forces which min-

imised the loss of life, and prostitute the truth in the process with gay abandon', the

deputy president said.

[ 4] Mbeki has spoken frequently in recent months on the requisites for an African

renaissance, with increasingly blunt criticism of dictatorship, mismanagement and

corruption.

Direct quotes Although research has shown that journalists turn what their

sources say into indirect reports, it has also been suggested that direct quotes also

play a major role (e.g. Rojo, 1995). Direct quotes in news stories have three pri-

mary purposes: to indicate that the quote is an incontrovertible fact because it is

the newsmaker's own words; to distance and disown the endorsement of what

the source said; and to add to the story the flavour of the newsmaker's own words

(e.g. Tuchman, 1978; Bell, 1991). In our data, however, the three functions are

not mutually exclusive -a single quote can realize more than one function at any

given time.

The two texts above display both similarities and differences in their attribution

strategies. While both use quotations to mark off some sections of the deputy

president's speech (e.g. in paragraphs [2] and [3] in P7, and [SJ in A5), the differ-

ent attitudes of the texts to the speaker is made clear by the surrounding dis-

course. In (A5), for example, some concepts from the original speech are

positioned within the journalistic account as direct quotes - the 'African

Renaissance' in [4] and 'humanity' in [8], the latter picking up the concept of

'humane approach' from the original text. The 'tone' of the text indicates that the

journalist distances himself (and the paper) from the validity of those quotes. This

purpose is reflected in the discourse context in which these quotes occur. For

instance, the i\.frican Renaissance' functions as a modifier to an informal term,

'shindig' (a noisy party), with reference to the forum where the former term was

used - and the absurdity of the concept 'humanity' is shown by contrasting

it with the images of death and bereavement carried in the same sentence.

The M&G's position is different from that of The Star (P7), in which the direct

Downloaded from das.sagepub.com at SOAS London on April 8, 2011

Thetela: Critique discourses and ideology 363

quotation from the deputy president appears to represent the paper's own views,

as there is no refutation of the content of the speech. Instead outside the quota-

tions, the concepts from the speech are treated as generally accepted facts: the

term 'renaissance' in [1]. [2] and [3]) is used without any quotation marks. The

attitude of the paper can also be seen in the preference of the more acceptable

term 'conference' as opposed to 'shindig' in (AS).

Speech verbs In our discussion on transitivity, and direct quotation above, we have

hinted on the heavy reliance of the news reports on verbal processes for their

operation. From the verbal process headlines, for example, we have seen the pref-

erence of performative verbs in reporting elite people's speeches. Here we argue

that speech verbs are particularly significant and can be used to indicate the jour-

nalist's purposes of bringing the newsmaker's voices into the news story. Taking

(P7), for example, although neutral verbs such as 'speaking' and 'said' are used,

the dominant choice is that of performative ( and evaluative) verbs such as

'slams', 'dismissed', asserted' and 'lashed', including the nominalization 'criti-

cism'. In this latter group, there is a fusion of a word and an act, to indicate, for

example, the quoted source's social standing (e.g. his/her elite status), purpose of

saying, and attitude to what he/she is talking about. This view is consistent with

several studies on the crucial role of performatives in the news - they are ideal for

news worthiness, and have the potential to provoke a response of a similar kind

(e.g. Van Dijk, 1988a; Bell, 1991).

Personalization and constructions of 'Otherness' Newsmakers' voices are brought

into the discourse through reference to people - the process of personalization,

which is a socially constructed value. The function of this value is 'to promote

straightforward feelings of identification, empathy or disapproval; to effect a

metonymic simplification of complex historical and institutional processes'

(Fowler, 19 91: 15). In this way, the people positioned in the discourse are repre-

sentative of certain categories of deviant behaviour. Elite people whose voices are

used in the news stories are assigned credentials ( or titles) that embody their

claims to news value. Examples of such accreditation are 'Professor Fink Haysom,

the presidential adviser, commented succinctly, [X]': (The Star, 3 Nov. 1998), or

'The sharpest criticism came from Chief of Special Forces Brigadier-General Borries

Bornman, who observed, [X]' (CA, 10 Oct. 1998), where [X] represents the speech

itself. This suggests that because the reader is likely to believe an 'expert' on a par-

ticular topic, the quoted voices are assigned some authoritative quality or authen-

ticity necessary to legitimize journalist's claims in the news story (e.g. Van Dijk,

1988a).

As has already been seen in (AS) above, personalization is not necessarily

complimentary, as newsmakers can be quoted in order to reject their versions

of events. In the present study, the journalists employ personalization in order

to apportion blame, thus establishing rival groups - the positive image of

'ingroups' and the negative one of 'outgroups' (see Van Dijk, 1995, 1998, on

Downloaded from das.sagepub.com at SOAS London on April 8, 2011

3 64 Discourse & Society 12 (3)

group identity). We now consider the major rival groups created through person-

alization in the press - the 'government vs. the critics', and the 'white vs. black'

racist stereotypes.

SA leaders as the 'Other' The AINA press, from the beginning of the war, blamed

the government for the decision to invade Lesotho, the subsequent crisis and the

latter's attitude to criticism. The apportionment of blame was done through two

main strategies. First, the newsmaker's voices (i.e. the critics) can be used as infor-

mation to support the journalist's own stance-it can take the form of what I call

'implicit collusion', where there is no linguistic signal to suggest that the journal-

ist disagrees with the quoted sources -or through 'explicit collusion' where the

journalist's positive evaluation signals agreement (seen in speech verbs and other

discourse strategies of involvement). The second strategy is that where the jour-

nalist quotes the blame target's voice (i.e. the government) in order to reject it (the

strategy of detachment). Both these involvement and detachment methods have

been seen in the analysis of (AS) and (P7) above.

The AINA press that referred to individual government's ministers ( using their

names and/or titles) are representative of institutional (e.g. the government)

negative values. Thus the ministers (for instance, Thabo Mbeki) were either 'the

government' or 'SA. They were introduced into the discourse as 'he' or 'them', to

be separated from the rival positive 'us' ('us' used for mainstream positive values).

A6: What precisely were our rights and obligations with regard to our own

Constitution and the body of international law which binds us - in particular, should

the presidency ( or to be precise, those passers-by whom the president cares to leave in

charge of the shop while he and his co-proprietor gallivant abroad) have the power to

commit South Africa to foreign adventures without more respect for the demands of

consultation and debate demanded by the democratic ideal? (M&G, 2 Oct. 1998)

One of the major criticisms in the AINA was that at the time of the crisis, both

the president and the deputy president as well as the foreign minister were on

overseas trips, and none of them cut their trips short when the crisis occurred,

leaving the responsibility of authorizing the intervention to the Home Affairs

Minister (as the Acting President). In (A6), for example, the enemy 'them' is

established through a collective label 'the presidency' or 'he' (for the president

himself), to be contrasted with 'us' in the opening clause (e.g. 'our Constitution').

The president and his deputy are represented in business metaphors as 'propri-

etors' (i.e. 'he and his co-proprietor'), whose deviant values are conceptualized

through the 'business vs. pleasure' discourse: the president leaves 'passers-by'

(identified elsewhere in the text as the Home Affairs Minister, Mangosuthu

Buthelezi and Social and Security Minister, Sydney Mufamadi (who failed to

broker a peace agreement between the political parties in Lesotho). The concept

of 'passers-by' implies the latter ministers' inexperience in handling the crisis.

The president and his deputy are characterized as irresponsible leaders, leaving

matters of national interest in the hands of junior ministers, while they pursued

less serious matter abroad (expressed in 'gallivant'). This deviant behaviour is

Downloaded from das.sagepub.com at SOAS London on April 8, 2011

Thetela: Critique discourses and ideology 365

seen as lack of respect for positive values -- 'the demands of consultation and debate

demanded by the democratic ideal'.

The social deviance of the government was also established through what can

be called the 'name = value' expressions, where the name was the ascribed value.

Examples of this can be seen in quoted statements such as 'compromise and fair-