Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Upper Intermediate Student's Book: One Size Doesn't Fit All

Upper Intermediate Student's Book: One Size Doesn't Fit All

Uploaded by

Sereg LeiteCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5825)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Speak Now (Taylor's Version) Digital BookletDocument20 pagesSpeak Now (Taylor's Version) Digital BookletGERES57% (7)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Writing Assessment Criteria: CEFR A1Document2 pagesWriting Assessment Criteria: CEFR A1GERES100% (2)

- Writing Assessment Criteria: CEFR A1Document2 pagesWriting Assessment Criteria: CEFR A1GERES100% (2)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- DisneyDocument18 pagesDisneyMinahus Saniyah Laraswati (Nia)No ratings yet

- Midnights 3am Edition Digital BookletDocument8 pagesMidnights 3am Edition Digital BookletGERES100% (2)

- Reading Part 7 Succeed in CAEDocument2 pagesReading Part 7 Succeed in CAEGERESNo ratings yet

- 4 Piles Cap With Eccentricity ExampleDocument3 pages4 Piles Cap With Eccentricity ExampleSousei No Keroberos100% (1)

- Writing Assessment Criteria: CEFR B2Document10 pagesWriting Assessment Criteria: CEFR B2GERESNo ratings yet

- Upper Intermediate Student's Book: Once Upon A Time ..Document3 pagesUpper Intermediate Student's Book: Once Upon A Time ..Christina MoldoveanuNo ratings yet

- Speaking Assessment Criteria: CEFR B2Document1 pageSpeaking Assessment Criteria: CEFR B2GERESNo ratings yet

- Speaking Assessment Criteria: CEFR C1Document1 pageSpeaking Assessment Criteria: CEFR C1GERESNo ratings yet

- Speaking Assessment Criteria: CEFR A2: Range and Accuracy Fluency and Coherence, Pronunciation 1.0Document1 pageSpeaking Assessment Criteria: CEFR A2: Range and Accuracy Fluency and Coherence, Pronunciation 1.0GERESNo ratings yet

- b1 WritingDocument2 pagesb1 WritingGERESNo ratings yet

- Writing Assessment Criteria: CEFR C1Document2 pagesWriting Assessment Criteria: CEFR C1GERESNo ratings yet

- Speaking Assessment Criteria: CEFR B1Document1 pageSpeaking Assessment Criteria: CEFR B1GERES0% (1)

- Advanced - Unit 9 - Audio - Track 30Document1 pageAdvanced - Unit 9 - Audio - Track 30GERESNo ratings yet

- Extract Two: C He Nearly DiedDocument2 pagesExtract Two: C He Nearly DiedGERESNo ratings yet

- Advanced - Unit 10 - Reading Text - East Meets WestDocument2 pagesAdvanced - Unit 10 - Reading Text - East Meets WestGERESNo ratings yet

- Speaking Assessment Criteria C1Document1 pageSpeaking Assessment Criteria C1GERESNo ratings yet

- Contextualized Online and Research SkillsDocument16 pagesContextualized Online and Research SkillsAubrey Castillo BrionesNo ratings yet

- Catalog - Tesys Essential Guide - 2012 - (En)Document54 pagesCatalog - Tesys Essential Guide - 2012 - (En)Anonymous FTBYfqkNo ratings yet

- 2010 Nissan Versa S Fluid CapacitiesDocument2 pages2010 Nissan Versa S Fluid CapacitiesRubenNo ratings yet

- Lab 1 - Introduction To Abaqus - CE529aDocument14 pagesLab 1 - Introduction To Abaqus - CE529aBassem KhaledNo ratings yet

- Ec&m PPT MirDocument14 pagesEc&m PPT MirAbid HussainNo ratings yet

- Astronomy - 12 - 15 - 18 - 5 - 6 KeyDocument11 pagesAstronomy - 12 - 15 - 18 - 5 - 6 Keykalidindi_kc_krishnaNo ratings yet

- Revision Class QuestionsDocument6 pagesRevision Class QuestionsNathiNo ratings yet

- Business Environment Ch.3Document13 pagesBusiness Environment Ch.3hahahaha wahahahhaNo ratings yet

- Bicycle Owner's Manual: ImportantDocument55 pagesBicycle Owner's Manual: ImportantAnderson HenriqueNo ratings yet

- TLNB SeriesRules 7.35Document24 pagesTLNB SeriesRules 7.35Pan WojtekNo ratings yet

- Accuracy and FluencyDocument4 pagesAccuracy and FluencyahmedaliiNo ratings yet

- Instant Download Exploring Psychology in Modules 10th Edition Myers Test Bank PDF Full ChapterDocument32 pagesInstant Download Exploring Psychology in Modules 10th Edition Myers Test Bank PDF Full Chapterurimp.ricedi1933100% (13)

- CatalogDocument20 pagesCatalogDorin ȘuvariNo ratings yet

- Andrew Mickunas - Teaching Resume PortfolioDocument3 pagesAndrew Mickunas - Teaching Resume PortfolioAndrewNo ratings yet

- List - Parts of Bahay Na Bato - Filipiniana 101Document7 pagesList - Parts of Bahay Na Bato - Filipiniana 101Eriellynn Liza100% (1)

- HRM1Document13 pagesHRM1Niomi GolraiNo ratings yet

- Bengur BryanDocument2 pagesBengur Bryancitybizlist11No ratings yet

- Almario, Rich L. - InvestmentDocument6 pagesAlmario, Rich L. - InvestmentRich Lopez AlmarioNo ratings yet

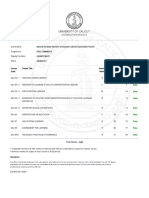

- Bed 2nd Sem ResultDocument1 pageBed 2nd Sem ResultAnusree PranavamNo ratings yet

- Perfetti Van MelleDocument24 pagesPerfetti Van MelleYahya Niazi100% (1)

- 3 Methods For Crack Depth Measurement in ConcreteDocument4 pages3 Methods For Crack Depth Measurement in ConcreteEvello MercanoNo ratings yet

- Thesis MetabolomicsDocument11 pagesThesis Metabolomicsfqh4d8zf100% (2)

- MCQs PPEDocument10 pagesMCQs PPEfrieda20093835100% (1)

- Case Study 1: The London 2012 Olympic Stadium 1. The ProjectDocument15 pagesCase Study 1: The London 2012 Olympic Stadium 1. The ProjectIván Comprés GuzmánNo ratings yet

- E-Auction Sale Notice For UPLOADINGDocument4 pagesE-Auction Sale Notice For UPLOADINGKiran ShindeNo ratings yet

- Acct Lesson 9Document9 pagesAcct Lesson 9Gracielle EspirituNo ratings yet

- Virtual SEA Mid-Frequency Structure-Borne Noise Modeling Based On Finite Element AnalysisDocument11 pagesVirtual SEA Mid-Frequency Structure-Borne Noise Modeling Based On Finite Element AnalysisKivanc SengozNo ratings yet

- R105Document1 pageR105Francisco Javier López BarrancoNo ratings yet

Upper Intermediate Student's Book: One Size Doesn't Fit All

Upper Intermediate Student's Book: One Size Doesn't Fit All

Uploaded by

Sereg LeiteOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Upper Intermediate Student's Book: One Size Doesn't Fit All

Upper Intermediate Student's Book: One Size Doesn't Fit All

Uploaded by

Sereg LeiteCopyright:

Available Formats

Upper Intermediate Student’s Book

Life

3c Page 39 READING TEXT

One size doesn’t fit all

Even if the term ‘appropriate technology’ is a relatively new one, the concept

certainly isn’t. In the 1930s Mahatma Gandhi claimed that the advanced technology

used by western industrialised nations did not represent the right route to progress

for his homeland, India. His favourite machines were the sewing machine, a device

invented ‘out of love’, he said, and the bicycle, a means of transport that he used all

his life. He wanted the poor villagers of India to use technology in a way that

empowered them and helped them to become self-reliant.

This was also the philosophy promoted by E.F. Schumacher in his famous book

Small is Beautiful, published in the 1970s, which called for ‘intermediate

technology’ solutions. Do not start with technology and see what it can do for

people, he argued. Instead, ‘find out what people are doing and then help them to

do it better’. According to Schumacher, it did not matter whether the technological

answers to people’s needs were simple or sophisticated. What was important was

that solutions were long-term, practical and above all firmly in the hands of the

people who used them.

More recently the term ‘appropriate technology’ has come to mean not just

technology which is suited to the needs and capabilities of the user, but technology

that takes particular account of environmental, ethical and cultural considerations.

That is clearly a much more difficult thing to achieve. Often it is found in rural

communities in developing or less industrialised countries. For example, solar-

powered lamps that bring light to areas with no electricity and water purifiers that

work simply by the action of sucking through a straw. But the principle of

appropriate technology does not only apply to developing countries. It also has its

place in the developed world.

For example, a Swedish state-owned company, Jernhuset, has found a way to

harness the energy produced by the 250,000 bodies rushing through Stockholm’s

Life

central train station each day. The body heat is absorbed by the

building’s ventilation system, then used to warm up water that is

pumped through pipes over to the new office building nearby. It’s

old technology – a system of pipes, water and pumps – but used in

a new way. It is expected to bring down central heating costs in the building by up

to twenty per cent.

Wherever it is deployed, there is no guarantee, however, that so-called ‘appropriate

technology’ will in fact be appropriate. After some visiting engineers observed how

labour-intensive and slow it was for the women of a Guatemalan village to shell

corn by hand, they designed a simple mechanical device to do the job more quickly.

The new device certainly saved time, but after a few weeks the women returned to

the old manual method. Why? Because they valued the time they spent hand-

shelling: it enabled them to chat and exchange news with each other.

In another case, in Malawi, a local entrepreneur was encouraged to manufacture

super-efficient wood-burning stoves under licence to sell to local villagers. Burning

wood in a traditional open fire, which is a common method of cooking food in the

developing world, is responsible for 10–20% of all global CO2 emissions, so this

seemed to be an excellent scheme. However the local entrepreneur was so

successful that he went out and bought himself a whole fleet of gas-guzzling cars.

‘We haven’t worked out the CO2 implications of that yet,’ said a spokesman from

the organisation that promoted the scheme.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5825)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Speak Now (Taylor's Version) Digital BookletDocument20 pagesSpeak Now (Taylor's Version) Digital BookletGERES57% (7)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Writing Assessment Criteria: CEFR A1Document2 pagesWriting Assessment Criteria: CEFR A1GERES100% (2)

- Writing Assessment Criteria: CEFR A1Document2 pagesWriting Assessment Criteria: CEFR A1GERES100% (2)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- DisneyDocument18 pagesDisneyMinahus Saniyah Laraswati (Nia)No ratings yet

- Midnights 3am Edition Digital BookletDocument8 pagesMidnights 3am Edition Digital BookletGERES100% (2)

- Reading Part 7 Succeed in CAEDocument2 pagesReading Part 7 Succeed in CAEGERESNo ratings yet

- 4 Piles Cap With Eccentricity ExampleDocument3 pages4 Piles Cap With Eccentricity ExampleSousei No Keroberos100% (1)

- Writing Assessment Criteria: CEFR B2Document10 pagesWriting Assessment Criteria: CEFR B2GERESNo ratings yet

- Upper Intermediate Student's Book: Once Upon A Time ..Document3 pagesUpper Intermediate Student's Book: Once Upon A Time ..Christina MoldoveanuNo ratings yet

- Speaking Assessment Criteria: CEFR B2Document1 pageSpeaking Assessment Criteria: CEFR B2GERESNo ratings yet

- Speaking Assessment Criteria: CEFR C1Document1 pageSpeaking Assessment Criteria: CEFR C1GERESNo ratings yet

- Speaking Assessment Criteria: CEFR A2: Range and Accuracy Fluency and Coherence, Pronunciation 1.0Document1 pageSpeaking Assessment Criteria: CEFR A2: Range and Accuracy Fluency and Coherence, Pronunciation 1.0GERESNo ratings yet

- b1 WritingDocument2 pagesb1 WritingGERESNo ratings yet

- Writing Assessment Criteria: CEFR C1Document2 pagesWriting Assessment Criteria: CEFR C1GERESNo ratings yet

- Speaking Assessment Criteria: CEFR B1Document1 pageSpeaking Assessment Criteria: CEFR B1GERES0% (1)

- Advanced - Unit 9 - Audio - Track 30Document1 pageAdvanced - Unit 9 - Audio - Track 30GERESNo ratings yet

- Extract Two: C He Nearly DiedDocument2 pagesExtract Two: C He Nearly DiedGERESNo ratings yet

- Advanced - Unit 10 - Reading Text - East Meets WestDocument2 pagesAdvanced - Unit 10 - Reading Text - East Meets WestGERESNo ratings yet

- Speaking Assessment Criteria C1Document1 pageSpeaking Assessment Criteria C1GERESNo ratings yet

- Contextualized Online and Research SkillsDocument16 pagesContextualized Online and Research SkillsAubrey Castillo BrionesNo ratings yet

- Catalog - Tesys Essential Guide - 2012 - (En)Document54 pagesCatalog - Tesys Essential Guide - 2012 - (En)Anonymous FTBYfqkNo ratings yet

- 2010 Nissan Versa S Fluid CapacitiesDocument2 pages2010 Nissan Versa S Fluid CapacitiesRubenNo ratings yet

- Lab 1 - Introduction To Abaqus - CE529aDocument14 pagesLab 1 - Introduction To Abaqus - CE529aBassem KhaledNo ratings yet

- Ec&m PPT MirDocument14 pagesEc&m PPT MirAbid HussainNo ratings yet

- Astronomy - 12 - 15 - 18 - 5 - 6 KeyDocument11 pagesAstronomy - 12 - 15 - 18 - 5 - 6 Keykalidindi_kc_krishnaNo ratings yet

- Revision Class QuestionsDocument6 pagesRevision Class QuestionsNathiNo ratings yet

- Business Environment Ch.3Document13 pagesBusiness Environment Ch.3hahahaha wahahahhaNo ratings yet

- Bicycle Owner's Manual: ImportantDocument55 pagesBicycle Owner's Manual: ImportantAnderson HenriqueNo ratings yet

- TLNB SeriesRules 7.35Document24 pagesTLNB SeriesRules 7.35Pan WojtekNo ratings yet

- Accuracy and FluencyDocument4 pagesAccuracy and FluencyahmedaliiNo ratings yet

- Instant Download Exploring Psychology in Modules 10th Edition Myers Test Bank PDF Full ChapterDocument32 pagesInstant Download Exploring Psychology in Modules 10th Edition Myers Test Bank PDF Full Chapterurimp.ricedi1933100% (13)

- CatalogDocument20 pagesCatalogDorin ȘuvariNo ratings yet

- Andrew Mickunas - Teaching Resume PortfolioDocument3 pagesAndrew Mickunas - Teaching Resume PortfolioAndrewNo ratings yet

- List - Parts of Bahay Na Bato - Filipiniana 101Document7 pagesList - Parts of Bahay Na Bato - Filipiniana 101Eriellynn Liza100% (1)

- HRM1Document13 pagesHRM1Niomi GolraiNo ratings yet

- Bengur BryanDocument2 pagesBengur Bryancitybizlist11No ratings yet

- Almario, Rich L. - InvestmentDocument6 pagesAlmario, Rich L. - InvestmentRich Lopez AlmarioNo ratings yet

- Bed 2nd Sem ResultDocument1 pageBed 2nd Sem ResultAnusree PranavamNo ratings yet

- Perfetti Van MelleDocument24 pagesPerfetti Van MelleYahya Niazi100% (1)

- 3 Methods For Crack Depth Measurement in ConcreteDocument4 pages3 Methods For Crack Depth Measurement in ConcreteEvello MercanoNo ratings yet

- Thesis MetabolomicsDocument11 pagesThesis Metabolomicsfqh4d8zf100% (2)

- MCQs PPEDocument10 pagesMCQs PPEfrieda20093835100% (1)

- Case Study 1: The London 2012 Olympic Stadium 1. The ProjectDocument15 pagesCase Study 1: The London 2012 Olympic Stadium 1. The ProjectIván Comprés GuzmánNo ratings yet

- E-Auction Sale Notice For UPLOADINGDocument4 pagesE-Auction Sale Notice For UPLOADINGKiran ShindeNo ratings yet

- Acct Lesson 9Document9 pagesAcct Lesson 9Gracielle EspirituNo ratings yet

- Virtual SEA Mid-Frequency Structure-Borne Noise Modeling Based On Finite Element AnalysisDocument11 pagesVirtual SEA Mid-Frequency Structure-Borne Noise Modeling Based On Finite Element AnalysisKivanc SengozNo ratings yet

- R105Document1 pageR105Francisco Javier López BarrancoNo ratings yet