Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Sexual Harrassment at Workplace

Sexual Harrassment at Workplace

Uploaded by

riv's aquarium0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

54 views22 pagesThis document provides an analysis of the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace Act, 2013 in India. It summarizes the key issues, including that sexual harassment creates an environment that hinders women's professional growth. The Vishaka Guidelines established by the Supreme Court in 1997 addressed this issue until the Act was passed in 2013, 16 years later. The Act aims to prevent and protect women from sexual harassment at work and provide redress for related complaints. It defines sexual harassment and workplaces and establishes complaint committees to address violations.

Original Description:

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

ODT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThis document provides an analysis of the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace Act, 2013 in India. It summarizes the key issues, including that sexual harassment creates an environment that hinders women's professional growth. The Vishaka Guidelines established by the Supreme Court in 1997 addressed this issue until the Act was passed in 2013, 16 years later. The Act aims to prevent and protect women from sexual harassment at work and provide redress for related complaints. It defines sexual harassment and workplaces and establishes complaint committees to address violations.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as ODT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as odt, pdf, or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

54 views22 pagesSexual Harrassment at Workplace

Sexual Harrassment at Workplace

Uploaded by

riv's aquariumThis document provides an analysis of the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace Act, 2013 in India. It summarizes the key issues, including that sexual harassment creates an environment that hinders women's professional growth. The Vishaka Guidelines established by the Supreme Court in 1997 addressed this issue until the Act was passed in 2013, 16 years later. The Act aims to prevent and protect women from sexual harassment at work and provide redress for related complaints. It defines sexual harassment and workplaces and establishes complaint committees to address violations.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as ODT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as odt, pdf, or txt

You are on page 1of 22

Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace: A Primer

on the Law

Prachi Dutta provides an analysis of the Sexual

Harassment of Women at Workplace Act, 2013.

Prachi Dutta

INTRODUCTION

Sexual Harassment is an insidious problem that poses

a serious impediment to society. Particularly, sexual

harassment of women at their place of work is a deep-

rooted problem which has severe negative

repercussions on the productivity, performance,

longevity of women in their careers and jobs. It can

hinder the professional growth of women as it creates

an environment which is not conducive for women to

thrive and evolve in. The problem of sexual

harassment of women at the workplace has been

recognised by Courts and governments, in most

countries across the world, and steps have been taken

to ensure that there are adequate safeguards to

protect women.

SEXUAL HARASSMENT OF WOMEN AT THE WORKPLACE

AND THE LAW IN INDIA

In India, the problem has been attempted to be

addressed by enacting the Sexual Harassment of

Women at Workplace Act (Prevention, Prohibition. and

Redressal) Act, 2013 (“The Act”), colloquially known as

the “POSH Act”. The Act is to prevent and protect

women against sexual harassment at workplace and

provide a redressal mechanism to address complaints

of sexual harassment or connected or incidental

matters.

The Act is a product of the “Vishaka Guidelines” that

were formulated by the Hon’ble Supreme Court of

India (“The Supreme Court”) in the case of Vishaka vs

State of Rajasthan 1 (“Vishaka Case”). This case is

monumental as it started a dialogue about the

problems and perils that women face during the course

of their employment or while trying to carry out their

professional duties and steps that can be taken to

rectify this problem. The Vishaka Case was brought in

as a class action by certain NGOs to focus the

attention towards preventing sexual harassment of

working women in all workplaces through judicial

process. In this case, a social worker, as part of her

professional duties, attempted to stop a child marriage

from taking place and was gangraped by members of a

community as they viewed her intervention as an

“assault” on their customs and traditions. The

Supreme Court realised that the incident reveals the

hazards to which working women may be exposed to

and the depravity to which sexual harassment can

degenerate and the urgency for safeguards by an

alternate mechanism in the absence of the legislative

measures and took the view that such incidents of

sexual harassment are a violation of the fundamental

rights under Article 14 2, 15 3, 21 4 of the Constitution

of India and consequently a violation of the victim’s

fundamental right under Article 19(1)(g) 5. The

Supreme Court also focused on the contents of

international conventions and norms such as the

Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of

Discrimination against Women and the Beijing

Statement of Principles on the Independence of the

Judiciary in the LAWSIA region, for the purpose of

interpreting the aforementioned fundamental rights as

the international conventions enlarge the meaning and

content of these provisions and promote the object of

the constitutional guarantee. Thereafter, the Supreme

Court, under their power under Article 32 and

consequentially Article 141 of the Constitution,

guidelines and norms were laid down which were to be

followed and observed at all workplaces or other

institutions until a legislation was enacted for the same

purpose. The guidelines defined sexual harassment,

mentioned preventive steps to be taken, stated the

procedure of adopting a complaint mechanism and

committee, amongst other crucial steps to be followed.

1. (1997)6 SCC 241

2. Equality before law: The State shall not deny any

person equality before the law or the equal protection

of the laws within the territory of India

3. Prohibition of discrimination on grounds of religion,

race, caste, sex or place of birth

4. Protection of life and personal liberty: No person

shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty expect

according to procedure established by law

5. Protection of certain rights regarding freedom of

speech, etc.: All citizens shall have the right to

practise any profession, or to carry on any occupation,

trade or business

However, the guidelines were not promptly

implemented and a legislation was enacted at an

extremely belated stage and consequently the

Supreme Court observed in the case of Medha Kotwal

Lele v Union of India 6 that the directions are not

supposed to be symbolic but must be followed. The

Supreme Court directed States and Union Territories to

carry out amendments in their respective Civil Services

Conduct Rules, carry out amendments in the Industrial

Employment (Standing Orders) Rules, form adequate

number of Complaints Committees so as to ensure that

they function at taluka level, district level and state

level. Further, organisations such as The Bar Council of

India shall ensure that all bar associations in the

country and persons registered with the State Bar

Councils follow the Vishaka guidelines and Medical

Council of India, Council of Architecture, Institute of

Chartered Accountants, Institute of Company

Secretaries and other statutory Institutes shall ensure

that the organisations, bodies, associations,

institutions and persons registered/affiliated with them

follow the guidelines laid down by Vishaka. Thereafter,

in the Seema Lepcha vs State of Sikkim 7, the

Supreme Court directed all States and Union

Territories to publicise and broadcast the compliances

and committees that they have formed. Further, the

enactment of the Act was thoroughly belated and

prolonged as it was enacted 16 years after the

guidelines were formulated by the Supreme Court. The

Act was also introduced in the Lok Sabha 10 (ten)

years (in 2007) after the guidelines were formulated

and was ultimately passed by the Rajya Sabha, after

an amendment was introduced in 2012, only on

26.02.2013 and it was eventually enacted and in force

on 22.05.2013.

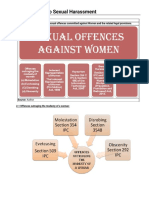

It is pertinent to note that there also exists a penal

provision for sexual harassment under the Indian

Penal Code, 1860 (“IPC”). Section 345A contains the

provisions of what constitutes as “sexual harassment”

and the punishment for it as well. However, it is

pertinent to note that this provision is not only

restricted to those acts of harassment committed in

the workplace and by invoking this provision for a case

of sexual harassment at the workplace, it would take

the form of a regular criminal complaint and the rules

and provisions of the Act would not be applicable.

However, a person can invoke Section 345A IPC and

also file a complaint under the Act as both the

remedies can co-exist in a parallel manner.

SALIENT FEATURES OF THE ACT

It is pertinent to note that the Act is a work in

progress as its provisions are constantly being

interpreted in order to give them a broad and liberal

meaning, so that the actual spirit and intent of the Act

is being fulfilled. Therefore, several definitions in the

Act and in the guidelines are not solely restricted to

the description given in the Act or the guidelines and

their interpretation is constantly evolving and

expanding.

6. (2013) 1 SCC 297

7. (2013) 11 SCC 641

What constitutes as sexual harassment

The Act states certain behaviour, act or

8

circumstances that may amount to sexual

harassment. However, sexual harassment is not only

restricted to such behaviour and through various case

laws, the Courts have enlarged the definition of sexual

harassment to give a broad and liberal interpretation

to behaviour or acts that constitute as sexual

harassment. In the case of Apparel Export Promotion

Council vs AK Chopra 9, the Supreme Court held that

sexual harassment is not just restricted to physical

contact but is a form of sex discrimination projected

through unwelcome sexual advances, request for

sexual favours and other verbal or physical conduct

with sexual overtones, whether directly or by

implication, particularly when submission to or

rejection of such a conduct by the female employee

was capable of being used for effecting the

employment of the female employee. Further, in the

case of Shanta Kumar vs Council of Scientific and

Industrial Research & Ors 10, the Delhi High Court held

that even though physical contact or advances would

constitute sexual harassment, such physical contact

must be a part of the sexually determined behaviour

and be in the context of a behaviour which is sexually

oriented. Plainly, a mere accidental physical contact,

even though unwelcome, would not amount to sexual

harassment. Similarly, a physical contact which has no

undertone of a sexual nature and is not occasioned by

the gender of the complainant may not necessarily

amount to sexual harassment. Therefore, the definition

of sexual harassment and what it constitutes is a grey

and nebulous area, which is not static either; the

definition and ambit is being constantly evolved and

enhanced, in order to ensure that the actual spirit and

intent of the Act is being fulfilled.

What constitutes as a “workplace”

Another important definition is that of

11

“workplace” which is not restricted solely to that

mentioned in the provision and has been interpreted

by Courts in order to ascribe a broader meaning to it.

In the case of Saurabh Kumar Mallick v Comptroller

and Auditor General of India and Anr 12, the Delhi High

Court stated that a narrow and pedantic approach

cannot be taken in defining the term ‘work place’ by

confining the meaning to the commonly understood

expression “office” that is a place where any person of

the public could have access. Therefore, each incident

of sexual harassment at the work place has to be

considered in the facts and circumstances of that

particular case and the definition of workplace cannot

be generalized to include all residences within the

meaning and ambit of work place, at it may lead to

absurdity. Further, the test laid down to determine a

particular place is work place or not (by the Tribunal in

this case), is the proximity from the place of work,

control of management over such place/residence

where working woman is residing; and such a

‘residence’ has to be an extension or contiguous part

of working place. At the same time, for proceeding

against an employee in a departmental inquiry, a

sweeping definition of ‘work place’ is not necessary

where it is interpreted to include the conduct of an

employee which would have no relation to work and

private disputes are not to be included.

That one of the most crucial aspects of the act is the

constitution of an Internal Complaints Committee

(“ICC”) and consequently the guidelines for their

functioning. The Act also provides for the constitution

of a Local Complaints Committee which is a significant

aspect of the Act. A Local Complaints Committee 13 is

one that is to be set up in every district to receive

complaints of sexual harassment from establishments

where the Internal Complaints Committee has not

been set up or the complaint is against the employer.

This provision of a Local Complaints Committee is

extremely crucial as it provides a redressal mechanism

to victims of sexual harassment in the absence of a

redressal mechanism, i.e. the Internal Complaints

Committee in their place of employment. This

provision gives a redressal mechanism to those victims

who are engaged in the “unorganised” sector such as

agricultural workers, labourers, domestic workers, etc.

A detailed analysis of the ICC and its mechanism is

given subsequently in this article.

8. Section 3 of the Act

9. (1997) 77 FLR 918 (Del)

10. (2018) 2 CLR 71

11. Section 2(o) of the Act

12. (2008) 151 DLT 261 (DB)

13. Section 5,6 of the Act

Statute of Limitation

It is pertinent to note that there does exist a period of

limitation in filing a complaint. A victim can file a

complaint only within a period of three months from

the date of the last incident 14. However, this period of

three months can be extended to an additional period

of three months if the Committee is satisfied that the

circumstances were such that they prevented the

victim to file the complaint 15 and the same was held

by the Delhi High Court in the case of Tejinder Kaur v

Union of India 16. Therefore, only in extraneous

circumstances when a victim could not file a complaint

within three months, would the maximum time limit of

filing a complaint be that of 6 (six) months, albeit the

discretion to extend the time limit lies with the

Committee and the Committee can dismiss the

extension request.

Conciliation and Inquiry

The Act also envisages that the Committees should

attempt conciliatory methods to settle the matter

between the concerned parties before proceeding with

conducting an inquiry or investigation however no

monetary settlement can be made as a basis to the

conciliation 17. Thereafter, in the event that the

conciliatory proceedings fail, the Committee is to

conduct an inquiry 18. After this, an inquiry report is to

be submitted to either the District Officer or the

employer, depending on the Committee, within 10

tends of inquiry, with either the fact that the

allegations have not been proved or recommendations

in the event that the allegations against the

Respondent have been proved and the same has to be

acted upon within a period of 60 (sixty) days from the

date of receipt of the report 19.

The Act also safeguards those who are a victim of false

or malicious complaints by directing a punishment in

accordance with the service rules applicable to the

person or in a manner as may be prescribed 20 and the

recommendation will be made only after an inquiry is

carried out. In the event that employers do not comply

with the provisions of the Act, a fine which may extend

to Rs.50,000/- shall be imposed on them 21.

14. Section 9 (1)

15. Proviso to Section 9(1)

16. (2018) 1 CLR 660

17. Section 10 of the Act

18. Section 11 of the Act

19. Section 13 of the Act

20. Section 14 of the Act

21. Section 26 of the Act

WORKING AND MECHANISM OF THE INTERNAL

COMPLAINTS COMMITTEE

Importance of a sound ICC

The ICC is the bedrock of this Act and the smooth and

proper functioning of ICCs is extremely crucial to

ensure that the intent and spirt of the Act is fulfilled. It

is also important for the ICC to be constituted exactly

in accordance with the Act as an improperly

constituted and infirm ICC leads to their

recommendations or decisions being vitiated and set

aside by Courts. Further, a procedurally sound and fair

or just composition of the ICC will attempt to ensure

that a fair inquiry investigation is conducted, a proper

and just recommendation or report is arrived and

both, the victim and the Respondent, get the justice

they deserve.

Further, a properly constituted ICC ensures that a

tangible outcome is arrived at, and this is especially

important in present day, as newer mediums of voicing

one’s “grievances” and alleged “redressal” are

emerging such as narrating one’s grievances on social

media. This itself poses several problems, namely lack

of accountability on part of the victim and lack of

impact or retribution on the “perpetrator” and more

often than not, does not bring any justice to the party

who has been wronged. In order to curb this

problem,ICCs must be constituted and strengthened in

order to provide a proper and adequate redressal

mechanism to victims of sexual harassment or to those

who have been falsely accused of it.

Composition of an ICC

The ICC has to have a presiding officer who shall be a

woman employed at a senior level or in the absence of

a senior level employee, one who is from other offices

or units of the workplace or in the absence of this as

well, a senior level woman employee from any other

workplace of the same employer or organisation or

department 22. It is pertinent to mention that there is

nothing to the contrary to indicate that the “lady

member” is to be senior in rank to the officer against

whom the allegation of sexual harassment are brought

and the same was held by the Allahabad High Court in

the case of Shobha Goswami v State of Rajasthan 23.

Further, there have to be two other members in the

ICC who are employees who are preferably either

committed to the cause of women or who have

experience in social work or legal knowledge 24.

Further, one member of the ICC has to be a person

from an NGO or associations committed to the cause

of women or who is familiar with issues of sexual

harassment 25. This provision of an “external member”

is important and an ICC must adhere to appointing an

external member in consonance with this provision as

the report or the ICC can be vitiated and invalid if the

appointment and qualification of the external member

is not in conformity with the requisite provision. The

Bombay High Court held in the case of Jaya Kodate v.

Rashtrasant Tukdoji Maharaj Nagpur University,

Bombay High Court 26 that the ICC without the

presence of an external member (either dedicated to

the cause of women or having experience in social

work or have legal knowledge related to sexual

harassment) would be illegal and contrary to the

provisions of the Act. Further, In the case of Ruchika

Singh Chhabra v M/S Air France India & Ors. 27, the

Delhi High Court invalidated the report of the ICC and

set it asideas the external member was not associated

with a non-governmental organization and his

qualifications have not been informed to the

complainant.

22. Section 4(2)(a) of the Act

23. 2015 LLR 1038

24. Section 4(2)(b) of the Act

25. Section 4(2)(c ) of the Act

26. [2014 SCC OnLine Bom 814]

27. 2018 LLR 697

Further, the Court stated that the external member is

not protected under Rule 4 of the Sexual Harassment

of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and

Redressal) Rule, 2013 (“Rules 2013”)as they only

apply District Committee under Section 7 because the

constitution of district committees already includes

independent members and not to ICCs. Further, all

ICCs have to have atleast one-half (50%) of their

members as women. The tenure of all the members of

the ICC is three years and any vacancy should be filled

expeditiously. Also, a proper ICC is that it cannot have

less than 3 (three) members and if there are less than

three members, then the recommendation of the ICC

is liable to be vitiated.

Composition of a Local Complaints Committee

The Local Complaints Committee is to have a

composition in which the Chairperson must be a

woman who is an eminent in the field of social work

and committed to the cause of women, one woman

member who is a woman working in the block, taluka,

tehsil or ward or municipality in the district 28. Further,

two other members must be nominated out of which

atleast one is from an NGO or association committed

towards cause of women or person familiar with issues

of sexual harassment 29. Further, out of these

nominees, atleast one must have a background in law

or legal knowledge and atleast one shall belong to

Scheduled Castes or Scheduled Tribes of Other

Backward Classes or minority communities as

notified 30. The tenure of the members is three

years 31.

It is also pertinent and crucial to note that the

proceedings of the ICC shall not be published,

communicated or made known to the public, press and

media 32 and in the event that this is contravened, the

person who does so shall be liable for penalty in

accordance with the service rules or in the absence of

such, in any manner as may be prescribed 33.

ICC and the Principles of Natural Justice

During the inquiry process, an ICC or Local Complaints

Committee is vested with the same powers as that of a

civil court under the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 in

terms of summoning and enforcing attendance of any

person and examine him under oath, discovery and

production of documents or in any other manner as

may be prescribed 34. The inquiry process has to be

completed within a period of 90 (ninety) days, as the

provision for this in the Act is a mandatory

provision 35. The inquiry process must be in accordance

to the service rules applicable or in any other manner

as may be prescribed. Further, the enquiry conducted

by the ICC should be a full-fledged inquiry complying

with the principles of natural justice, as stated in the

case of M/S Air India Represented By Its Chairman and

Managing Director and Others v L.S. Sibu and

Others 36 and also under Rule 7(4) of the Rules 2013.

Further, in enquiry proceedings, strict rules of

evidence are not required to be followed and the

enquiry committee can adopt its own procedure in

conformity with the principles of natural justice, as

held by the Delhi High Court in the case of Gaurav Jain

vs Hindustan Latex Family Planning Promotion Trust &

Ors 37. The principles of natural justice and rules in

conformity with thus would include a sufficient and

reasonable opportunity given to Respondent (accused)

to respond to the allegations made against him 38,

amongst other various principles of natural justice.

28. Section 7 (1) (a) and (b) of the Act

29. Section 7 (1)( c) of the Act

30. Ibid

31. Section 7(1)(2) of the Act

32. Section 16 of the Act

33. Section 17 of the Act

34. Section 11 (3) of the Act

35. Section 11(4) of the Act

36. 2018 SCC OnLine Ker 13878

37. 2015 SCC OnLine Del 11026

38. Ibid

Often decisions or recommendations of an ICC is

challenged in a Court on the grounds of bias in the

proceedings or in the composition of the Committee.

This problem and issue of bias in the ICC inquiry and

report has been adequately addressed by various

courts. In the case of Somaya Gupta v Jawaharlal

Nehru University and Anr. 39, the Delhi High Court held

that a real likelihood of bias must be established and a

mere apprehension in the Petitioner's (victim) mind

would be insufficient for securing such relief. Further,

since there was no allegation that any of the members

of the ICC have any pecuniary or personal interest in

the matter and no material on record which would

even remotely lead to any suspicion that the members

of the ICC have any personal interest that would

conflict in their obligation to conduct an inquiry fairly

and make a fair recommendation, is insufficient to

doubt the integrity or ability of the ICC to render an

unbiased opinion 40. In the case of U.S. Verma,

Principal, DPS & Anr. vs. National Commission for

Women & Ors, 41 the Delhi High Court held that an

elementary principle of natural justice is that the

administrative authority should be free from bias. Bias

or impartiality is fairly easy to comprehend however

there frequently are situations when the dividing line

between what is acceptable, and what is not, is not a

bright one. On such occasions, Courts have chosen to

follow the “reasonable likelihood” of bias standard,

which has now been reiterated as a “strong suspicion”

of bias standard and this, coupled with the sound

aphorism that not only impartiality, but the

appearance of impartiality, should be the guiding

standard, is the criterion which Courts ordinarily

follow 42. In the case of Vidya Akhave v Union of India

& Ors. 43, the Bombay High Court held that the Court

will be slow in interfering with the punishment

imposed by the Disciplinary Authority if the Court does

not conclude that the penalty imposed is shockingly

disproportionate to the misconduct committed by the

employee. Therefore, allegations of bias and

unfairness and absence of adherence of the principles

of natural justice have to be reasonable, strong, likely

and have to be adequately established by the person

alleging it in order to a Court to vitiate the proceedings

of the ICC on grounds of bias.

INTERNAL COMPLAINTS COMMITTEE AND

EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTIONS

Educational institutions, such as school, colleges,

universities also come under the purview of the Act

and therefore are obligated to set up an ICC in their

respective institutions. In schools, all employees,

teachers and non-teaching staff, are covered under the

provisions of the Act since schoolsare within the

definition of “workplace”. It is however pertinent to

note that in schools, the Act only covers the

employees and not the students, since the students

are under the age of 18 years old and therefore any

instance of sexual harassment or violation will attract

the provisions of the Protection of Children From

Sexual Offences Act,2009.

39. (2018) 159 FLR 390

40. Ibid

41. (2009) 163 DLT 557

42. Ibid

43. (2016) 6 AIR Bom R 506

The Government of NCT Of Delhi vide notification

number “NO.F.DE.15/Act-

I/VishakhaGuidelines/2014/25342-47”, dated

28.07.2014, directed all schools to observe guidelines

to protect women from sexual harassment at

workplace and directed all schools, including private

unaided registered school to form an ICC to serve as a

redressal mechanism. Not withstanding these

regulations and guidelines, in the event that a school,

day care centre, nursery or creche does not have a

duly constituted ICC, then the aggrieved woman can

file a complaint with the Local Complaints Committee.

Universities and colleges too fall under the purview of

the Act. The University Grants Commission (“UGC”),

vide letter dated 14.05.2019, bearing number DO. Ni.

F. 91-3/2014(GS)Pt. 1, addressed to the Vice-

Chancellors of all Universities, directing them to

ensure that an ICC and Special Cell is constituted in

their institutions to deal with issues of gender based

violence. Further, the UGC has formulated the

University Grants Commission (Prevention, Prohibition

and Redressal of Sexual Harassment of Women

Employees and Students in High Educational

Institutions) Regulations, 2015 which applies to all

higher educational institutions in India. Under these

regulations, the provisions of the Act are extended to

higher educational institutions and campuses in India.

These regulations direct that an ICC be set up in all

universities and direct that the composition of the ICC

differ in the event that the matter involves students 44.

Further, the regulations explicitly forbade senior

administrative post holders such as the vice-

chancellor, pro-vice Chancellor, Deans, Registrar, etc.

from being members of the ICC 45. The process of

inquiry of the ICC is similar to that in the Act.

However, the punishment is slightly different and

differs when the offender is an employee or a

student 46. These regulations are important as they

ensure that the provisions of the Act are being

implemented and that students and employees in

higher educational institutions have an adequate

redressal mechanism.

APPELLATE REDRESSAL MECHANISM

Any person who is aggrieved by the recommendations

made by the ICC and the Local Complaints Committee,

may prefer an appeal to the Court or tribunal in

accordance with the provisions of the service rules or

in the absence of service rules, any such manner as

may be prescribed, within a period of ninety days since

the recommendations 47. Further, under the Rules

2013, a person may prefer an appeal to the appellate

authority notified under Section 2(a) of the Industrial

Employment (Standing Orders) Act, 1946 48. However,

the problem arises when the appellate authority has

not been set up, particularly given the fact that Courts

do not function as an appellate authority of ICC

decisions. The absence of an appellate authority is

detrimental and negates the very purpose of the Act

as an aggrieved person is denied an appellate

redressal forum in the face of an infirm and

disproportionate verdict. It is crucial that a strong

appellate authority is set up in, especially in the

absence of service rules, so that an aggrieved person

has the option and legal remedy to approach an

appellate authority, in order to rectify any infirmity in

the recommendation of the ICC, so that the purpose

and spirit of the Act are intact and fulfilled.

44. Section 4(1)(c) of the Act

45. Section 4(3) of the Act

46. Section 10(1) and 10(2) of the Act

47. Section 18(1) and Section 18(2) of the Act

48. Rule 11 of the Rules 2013

SEXUAL HARASSMENT ELECTRONIC BOX (SHE-BOX)

The concept of Sexual Harassment Electronic Box or

“She-Box” has been developed by the Government of

India. It is an online platform which is available on the

website of the Ministry of Women and Child

Development. The She-Box was developed to ensure

that the Act is effectively implemented. It provides a

compliant redressal mechanism to all woman working

either in the organised or unorganised, private or

public sector and who have faced instances of sexual

harassment at their respective workplace 49. Any

woman facing sexual harassment at workplace can

register their complaint through this portal and the

complaint is thereafter directly sent to the concerned

authority having jurisdiction to take action into the

matter, such as the ICC of the organisation 50. This is

an important development as it provides an accessible

redressal mechanism to women who are victims of

sexual harassment at their workplace.

CONCLUSION

The enactment of the Act, albeit thoroughly belated,

has been a crucial step towards combating the menace

of sexual harassment at the workplace. The Act

provides for a redressal mechanism in order to ensure

a fair inquiry and consequentially a just and

reasonable recommendation, so that the aggrieved

person gets the justice they deserve. The Act is a work

in progress and its provisions are constantly being

interpreted in a liberal manner by Courts, in order to

broaden the purview and ambit of these provisions, so

that the true intent of the Act is fulfilled.All workplaces

must adhere to the provisions of the Act and ensure

that the spirit of the Act is fulfilled. In order to ensure

this is done, the penalty of non-compliance should be

enhanced to serve as a reasonable deterrence to

employers who do not comply with the Act, especially

in setting up a procedurally sound and fair ICC. It

should also be clarified as to who the fine is paid to, as

the Act is silent on it. Further, employees should

ensure that an inquiry is carried out as expeditiously

as possible and definitely within the period of 90 days,

in order to prevent prolonged mental agony to both

the parties.

Further, the Act is one that is intended to address and

the rectify the problem of sexual harassment at the

workplace faced by women and some lacunae in the

Act are still prevalent. For example, the Act can also

be misused, in the form of a false, vengeful and

frivolous complaint filed by a person. In order to

ensure that the Act is not misused and abused and

that its true intent is intact, the provision regarding

penalty and punishment for false or malicious

complaint (Section 14 of the Ac) must be clarified and

employers should lay down in detail the penalty and

punishment for filing false complaints in the absence

of any service rules. Further, the limitation period of

filing a complaint of 3 months should be enhanced to a

significantly larger time period, as such incidents can

have serious and negative repercussions of the

mental, emotional, physical well-being of a person and

person may lack the courage, strength and mental

bandwidth to come forward to file a complaint within a

period as short as three months from the time when

the incident occurred.

49. http://www.shebox.nic.in/user/about_shebox

50. Ibid

The Act is intended to create a safe space for women

to thrive and work in and therefore all possible efforts

should be made by all stakeholders in ensuring that

the ideals and intent of the Act are upheld. Employees

should conduct workshops and seminars regularly to

acquaint employers with the provisions of the Act and

sensitise them about gender and sexuality, in order to

create awareness about the problems and perils of

sexual harassment. Further, in a broader sense,

conversations and dialogues should take place,

starting from in schools, in order to create awareness

about gender and diversity and consequential to

reduce gender based discrimination and stereotypes

that are often developed at a young age. By doing

thus, the seeds of creating an environment where

women can be safe and can thrive and grow in are

sown at an early stage.

You might also like

- The Vishaka GuidelinesDocument11 pagesThe Vishaka GuidelinesBhavika GholapNo ratings yet

- Sexual Harrassment at WorkplaceDocument9 pagesSexual Harrassment at Workplaceriv's aquariumNo ratings yet

- IntroductionDocument8 pagesIntroductionNishant Singh DeoraNo ratings yet

- Vishakha Vs State of RajasthanDocument13 pagesVishakha Vs State of RajasthanAditya KaranNo ratings yet

- Critical Analysis On Sexual Harassment in Workplace inDocument15 pagesCritical Analysis On Sexual Harassment in Workplace inMeganathNo ratings yet

- This Article Is Written by Samriddhi Kapoor, University of Petroleum & Energy Studies School of LawDocument6 pagesThis Article Is Written by Samriddhi Kapoor, University of Petroleum & Energy Studies School of LawSamriddhi KapoorNo ratings yet

- Sexual HarassmentDocument20 pagesSexual HarassmentAman KumarNo ratings yet

- Vishaka and Others V. State of RajasthanDocument10 pagesVishaka and Others V. State of RajasthanPiyush Nikam MishraNo ratings yet

- Vishakha Vs State of Rajasthan RPDocument5 pagesVishakha Vs State of Rajasthan RPBhavi Ved0% (1)

- Vishaka v. State of RajashtanDocument7 pagesVishaka v. State of RajashtanAvinash Borana89% (18)

- History - Anti Sexual Harassment in IndiaDocument4 pagesHistory - Anti Sexual Harassment in IndiaaishwaryaNo ratings yet

- Posh Act - Implementational ChallengesDocument7 pagesPosh Act - Implementational ChallengesRiya PareekNo ratings yet

- Anushka Gupta Legal AssignmentDocument13 pagesAnushka Gupta Legal AssignmentANUSHKANo ratings yet

- Yash Jain Case3Document2 pagesYash Jain Case3YashJainNo ratings yet

- Case Summary Medha Kotwal Lele Vs Union of India October 2012Document3 pagesCase Summary Medha Kotwal Lele Vs Union of India October 2012Dr. Rakesh KumarNo ratings yet

- Sexual Harassment of Women at Work PlaceDocument21 pagesSexual Harassment of Women at Work PlacehygfttgNo ratings yet

- SamriddhiDocument7 pagesSamriddhiSamriddhi KapoorNo ratings yet

- The Perpetrators of Punished To The Fullest Extent of The LawDocument6 pagesThe Perpetrators of Punished To The Fullest Extent of The LawCharit MudgilNo ratings yet

- VishakhaDocument14 pagesVishakhaaniket aryanNo ratings yet

- CIA 3 - Labour LawDocument6 pagesCIA 3 - Labour LawKhushi LunawatNo ratings yet

- Women and Law: General Class Test-2ndDocument14 pagesWomen and Law: General Class Test-2ndSadhvi SinghNo ratings yet

- 32368legal22291 MDocument19 pages32368legal22291 MratiNo ratings yet

- Vishaka vs. State of RajasthanDocument12 pagesVishaka vs. State of RajasthanRIYA JAINNo ratings yet

- 1.1 Judicial Process as an instrument of social orderingDocument6 pages1.1 Judicial Process as an instrument of social orderingsuryanarayandas1994No ratings yet

- Vishaka CaseDocument3 pagesVishaka CaseVinod JoshiNo ratings yet

- Essay 6 - Sexual HarassmentDocument12 pagesEssay 6 - Sexual HarassmentAsha YadavNo ratings yet

- Efficacy of Laws Relating To Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace in India: StudyDocument10 pagesEfficacy of Laws Relating To Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace in India: StudyKaushiki SharmaNo ratings yet

- Sexual Harassment of Women at The WorkplaceDocument4 pagesSexual Harassment of Women at The WorkplaceABHISHEK ANANDNo ratings yet

- POSH Act JudgementsDocument8 pagesPOSH Act JudgementsDisha BasnetNo ratings yet

- Women and CriminalDocument5 pagesWomen and CriminalAdhiraj singhNo ratings yet

- VIshakha Guidelines & POSHDocument8 pagesVIshakha Guidelines & POSHManish KumarNo ratings yet

- Sexual Hazartment of Women at OfficeDocument3 pagesSexual Hazartment of Women at OfficeMohandas PeriyasamyNo ratings yet

- SBILL CHP 20Document24 pagesSBILL CHP 20Chayank lohchabNo ratings yet

- India:: Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace: A Brief Analysis of The POSH Act, 2013Document4 pagesIndia:: Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace: A Brief Analysis of The POSH Act, 2013Yash SinghNo ratings yet

- Moot 3Document3 pagesMoot 3rudraniNo ratings yet

- Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013 - WikipediaDocument37 pagesSexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013 - WikipediaJAHANGEER AHAM BAHTNo ratings yet

- VISHAKA v. STATE OF RAJASTHAN, AIR 1997 SC 3011Document15 pagesVISHAKA v. STATE OF RAJASTHAN, AIR 1997 SC 3011Shazaf KhanNo ratings yet

- The Meaning of-WPS OfficeDocument5 pagesThe Meaning of-WPS OfficeNaveenNo ratings yet

- Sexual Harassment The Unrecognized Gender 1705512433Document15 pagesSexual Harassment The Unrecognized Gender 1705512433HarshNo ratings yet

- Case Study On Vishaka and Ors. V. State of RajasthanDocument13 pagesCase Study On Vishaka and Ors. V. State of RajasthanABHINAV DEWALIYANo ratings yet

- Project On Harassment of Women at Work PlaceDocument22 pagesProject On Harassment of Women at Work PlaceAbhinav PrakashNo ratings yet

- Shakshi Vs Union of IndiaDocument12 pagesShakshi Vs Union of IndiaTanuj Shankar GaneshNo ratings yet

- Law Related To W&C 200013015023Document10 pagesLaw Related To W&C 200013015023khushi JainNo ratings yet

- RESOURCE - 1 Employee IntroDocument3 pagesRESOURCE - 1 Employee IntrosnzrealtorsNo ratings yet

- Case StudyDocument14 pagesCase StudyAshish pariharNo ratings yet

- 16010125004-The Sexual Harassment of Women at WorkplaceDocument8 pages16010125004-The Sexual Harassment of Women at WorkplaceSudev SinghNo ratings yet

- ConclusionDocument2 pagesConclusionGargi agarwalNo ratings yet

- Sexual Harassment of Women in WorkplaceDocument3 pagesSexual Harassment of Women in WorkplaceMohanrajNo ratings yet

- Presentation Sexual Harassment at WorkplaceDocument21 pagesPresentation Sexual Harassment at WorkplaceRajiv RanjanNo ratings yet

- Sexual Harassment FootnotesDocument15 pagesSexual Harassment FootnotesPriyadarshan NairNo ratings yet

- Vishakha and Others v. State of Rajasthan and Others: CA2.AssignmentDocument6 pagesVishakha and Others v. State of Rajasthan and Others: CA2.Assignmentmayank sachdeva100% (1)

- Law Relating To Sexual Harassment of Women at The Workplace in India: A Critical ReviewDocument23 pagesLaw Relating To Sexual Harassment of Women at The Workplace in India: A Critical ReviewAhmedNo ratings yet

- Vishaka JudgmentDocument11 pagesVishaka Judgmentrashi_misra100% (2)

- Sexual Harrasment at Workplace ActDocument17 pagesSexual Harrasment at Workplace ActLivanshu Garg67% (3)

- MODULE 2 (C) - The Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013Document5 pagesMODULE 2 (C) - The Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013Akshi JainNo ratings yet

- SocioprojDocument13 pagesSocioprojshatakshi152-22No ratings yet

- JPIOSDocument51 pagesJPIOSsastika agrawalNo ratings yet

- Sexual Harassment of Women in WorkplaceDocument3 pagesSexual Harassment of Women in WorkplaceAshwathNo ratings yet

- Case StudyDocument14 pagesCase StudyAshish pariharNo ratings yet

- Vishaka V. State of Rajasthan & Ors.: CourtDocument11 pagesVishaka V. State of Rajasthan & Ors.: CourtTharun PranavNo ratings yet

- UGC Notification On Sexual HarassmentDocument8 pagesUGC Notification On Sexual HarassmentPrayas DansanaNo ratings yet

- 2021iscreducedsyllabusxi Legal StudiesDocument3 pages2021iscreducedsyllabusxi Legal StudiesbhavyaNo ratings yet

- Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013 - WikipediaDocument37 pagesSexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013 - WikipediaJAHANGEER AHAM BAHTNo ratings yet

- P S H W: 1 Internal AssessmentDocument16 pagesP S H W: 1 Internal AssessmentSME 865No ratings yet

- Prachi SharmaDocument79 pagesPrachi SharmaTathay SharmaNo ratings yet

- Case Study On Vishaka and Ors. V. State of RajasthanDocument13 pagesCase Study On Vishaka and Ors. V. State of RajasthanABHINAV DEWALIYANo ratings yet

- Sexual HarassmentDocument20 pagesSexual HarassmentAman KumarNo ratings yet

- MSC Digital Society Sample QuestionsDocument7 pagesMSC Digital Society Sample QuestionsAshis RoutNo ratings yet

- Prevention of Sexual Exploitation at WorkplaceDocument34 pagesPrevention of Sexual Exploitation at WorkplaceShresth GuptaNo ratings yet

- Paper Cutting 6Document71 pagesPaper Cutting 6Vidya AdsuleNo ratings yet

- Critical Analysis of Posh Act 2013 PDFDocument43 pagesCritical Analysis of Posh Act 2013 PDFRamanah V100% (1)

- Jsimla - Sept 2013Document52 pagesJsimla - Sept 2013Anonymous S0H8cqgnfi100% (1)

- Vishaka vs. State of RajasthanDocument12 pagesVishaka vs. State of RajasthanRIYA JAINNo ratings yet

- The Boss Who Was Nice! or Not So?Document35 pagesThe Boss Who Was Nice! or Not So?SAURABH SINGHNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Final ReportDocument24 pagesResearch Paper Final ReportSukrit GandhiNo ratings yet

- BB On Sexual Harassment Against Women at Workplace & It's Effect On Motivatio.Document55 pagesBB On Sexual Harassment Against Women at Workplace & It's Effect On Motivatio.Vishakha Dhotre100% (1)

- Redressal Mechanism: © For BSNL Internal Circulation OnlyDocument20 pagesRedressal Mechanism: © For BSNL Internal Circulation OnlyrttcNo ratings yet

- Case Commentary On Vishakha Vs State of RajasthanDocument6 pagesCase Commentary On Vishakha Vs State of RajasthanDebapom PurkayasthaNo ratings yet

- Sexual Exploitation of A Working WomenDocument18 pagesSexual Exploitation of A Working WomenVansh LalwaniNo ratings yet

- Discrimination at WorkDocument19 pagesDiscrimination at WorkruchikabantaNo ratings yet

- Sexual Harassment of Women in IndiaDocument16 pagesSexual Harassment of Women in IndiaTharun PranavNo ratings yet

- Vishakha GuidelinesDocument10 pagesVishakha GuidelinesSubodh YadavNo ratings yet

- History 1 Position of Women FINAL FINALDocument21 pagesHistory 1 Position of Women FINAL FINALPrabhakar SharmaNo ratings yet

- Prevention of Sexual Harassment at Workplace PDFDocument43 pagesPrevention of Sexual Harassment at Workplace PDFok123No ratings yet

- Sexual Harassment at The WorkplaceDocument8 pagesSexual Harassment at The WorkplaceAmena RizviNo ratings yet

- Presentation On Case Law - Vishaka & Ors Vs State of Rajasthan & OrsDocument24 pagesPresentation On Case Law - Vishaka & Ors Vs State of Rajasthan & OrsDishant Doshi DoshiNo ratings yet

- Offences Against Women - Laws Relating To Sexual Harassment and Rape PDFDocument20 pagesOffences Against Women - Laws Relating To Sexual Harassment and Rape PDFAbdul JalilNo ratings yet