Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Early Acute Respiratory Support For Pregnant.97381

Early Acute Respiratory Support For Pregnant.97381

Uploaded by

Elena Evelyng CastellanosCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- (Bay) Soapie-NcpDocument19 pages(Bay) Soapie-NcpAJ BayNo ratings yet

- The Human Circulatory System: Grade 9 - Sussex - Wennappuwa - ScienceDocument23 pagesThe Human Circulatory System: Grade 9 - Sussex - Wennappuwa - ScienceSwarnapaliliyanageNo ratings yet

- Ultimate Exercise Cheat Sheet - TricepsDocument13 pagesUltimate Exercise Cheat Sheet - TricepsAHMED EMADNo ratings yet

- Bronchopulmonary DysplasiaDocument17 pagesBronchopulmonary DysplasiasnphNo ratings yet

- Influenza Guidelines - 25april 2023 FinalDocument32 pagesInfluenza Guidelines - 25april 2023 FinalQalbiNo ratings yet

- Soluciones de VIDocument2 pagesSoluciones de VILailaNo ratings yet

- Acute Respiratory Failure and Mechanical Ventilation in Women With COVID-19 During PregnancyDocument10 pagesAcute Respiratory Failure and Mechanical Ventilation in Women With COVID-19 During PregnancyJose Francisco Zamora ScottNo ratings yet

- Acog Prono EmbarazoDocument3 pagesAcog Prono EmbarazoRenzo del Oscar Cruz CaldasNo ratings yet

- The Central Role of Clinical Nutrition in COVID-19 Patients During and After Hospitalization in Intensive Care UnitDocument5 pagesThe Central Role of Clinical Nutrition in COVID-19 Patients During and After Hospitalization in Intensive Care UnitReaz MorshedNo ratings yet

- Treatment of Coronavirus Disease 2019.4Document5 pagesTreatment of Coronavirus Disease 2019.4Gaby VillasmilNo ratings yet

- EditDocument10 pagesEditParamitha HarmanNo ratings yet

- Jama Murthy 2020 It 200008Document2 pagesJama Murthy 2020 It 200008jorgeNo ratings yet

- Assoalho Pelvico em Tempos de Covid19Document8 pagesAssoalho Pelvico em Tempos de Covid19Silas CristianoNo ratings yet

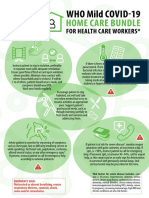

- WHO COVID-19-Home-Care-BundleDocument2 pagesWHO COVID-19-Home-Care-BundleOCSAF - P2LT PUNSALAN MCNo ratings yet

- Efects of Short-Term Breathing Exercises On Respiratory Recovery in Patients With COVID-19: A Quasi-Experimental StudyDocument10 pagesEfects of Short-Term Breathing Exercises On Respiratory Recovery in Patients With COVID-19: A Quasi-Experimental StudymrsikazweNo ratings yet

- Critical Care of Patient With Covid 19Document32 pagesCritical Care of Patient With Covid 19Anonymous Kv0sHqFNo ratings yet

- Care For Critically Ill Patients With COVID-19: Clinical UpdateDocument2 pagesCare For Critically Ill Patients With COVID-19: Clinical UpdateNicole BatistaNo ratings yet

- Corticosteroids in The Management of Pregnant.26Document4 pagesCorticosteroids in The Management of Pregnant.26Luciana Salomé Bravo QuintanillaNo ratings yet

- Nutrients: Nutritional Interventions For COVID-19: A Role For Carnosine?Document5 pagesNutrients: Nutritional Interventions For COVID-19: A Role For Carnosine?Stalin ChandrasekaranNo ratings yet

- I PREVENT COVID FLU RSV SummaryDocument3 pagesI PREVENT COVID FLU RSV SummaryServaas OostrikNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 2213219820313970Document4 pagesPi Is 2213219820313970cuvinhNo ratings yet

- Covid JCDRDocument4 pagesCovid JCDRRoyalelectronics IndiaNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Efficacy of Dexamethasone and Methylprednisolone in Improving Pao2/Fio2 Ratio Among Covid-19 PatientsDocument7 pagesComparison of Efficacy of Dexamethasone and Methylprednisolone in Improving Pao2/Fio2 Ratio Among Covid-19 PatientsNivedanSahayNo ratings yet

- Mja2 50598Document10 pagesMja2 50598Andi Astrid AmaliaNo ratings yet

- Consensus Statement: Safe Airway Society Principles of Airway Management and Tracheal Intubation Specific To The COVID-19 Adult Patient GroupDocument10 pagesConsensus Statement: Safe Airway Society Principles of Airway Management and Tracheal Intubation Specific To The COVID-19 Adult Patient GroupMeska AmeliaNo ratings yet

- Coronavirus Disease 2019 COVID 19 and Pregnancy .2Document4 pagesCoronavirus Disease 2019 COVID 19 and Pregnancy .2Elena Evelyng CastellanosNo ratings yet

- Coronavirus Disease 2019 COVID 19 and Pregnancy .2 PDFDocument4 pagesCoronavirus Disease 2019 COVID 19 and Pregnancy .2 PDFreza1811No ratings yet

- Gibbs2020 2Document14 pagesGibbs2020 2Dan ZhouNo ratings yet

- AnnalsATS 202003-233PSDocument4 pagesAnnalsATS 202003-233PSambitiousamit1No ratings yet

- Int J Clinical Practice - 2021 - Acat - Comparison of Pirfenidone and Corticosteroid Treatments at The COVID 19 PneumoniaDocument12 pagesInt J Clinical Practice - 2021 - Acat - Comparison of Pirfenidone and Corticosteroid Treatments at The COVID 19 PneumoniaRebeca EscutiaNo ratings yet

- Treatment Strategies For Asthma: Reshaping The Concept of Asthma ManagementDocument11 pagesTreatment Strategies For Asthma: Reshaping The Concept of Asthma Managementtegarsh321No ratings yet

- Four Patients With A History of Acute Exacerbations of COPD - Implementing TheDocument7 pagesFour Patients With A History of Acute Exacerbations of COPD - Implementing TheDorothy CasumpangNo ratings yet

- The Journal For Nurse PractitionersDocument5 pagesThe Journal For Nurse Practitionersagstri lestariNo ratings yet

- Accepted: PM&R and Pulmonary Rehabilitation For COVID-19Document25 pagesAccepted: PM&R and Pulmonary Rehabilitation For COVID-19Natalie Zapata CarreraNo ratings yet

- CARTA A FAVORPotential Benefits of Precise Corticosteroids Therapy For Severe EXCELENTEDocument3 pagesCARTA A FAVORPotential Benefits of Precise Corticosteroids Therapy For Severe EXCELENTEWilson Marcial Guzman AguilarNo ratings yet

- Re-Thinking The Early Intubation Paradigm of COVID-19: Time To Change Gears?Document4 pagesRe-Thinking The Early Intubation Paradigm of COVID-19: Time To Change Gears?Gilberto ValenciaNo ratings yet

- Presentasi Dr. Basuki Rachmad, Sp. An. KICDocument39 pagesPresentasi Dr. Basuki Rachmad, Sp. An. KICinstalasi kamar bedah RSMINo ratings yet

- Pharmacological Treatment of Patients With Mild To Moderate COVID-19: A Comprehensive ReviewDocument12 pagesPharmacological Treatment of Patients With Mild To Moderate COVID-19: A Comprehensive ReviewPhạm Trịnh Công BìnhNo ratings yet

- Approach To The Pregnant Patient With A Respiratory InfectionDocument42 pagesApproach To The Pregnant Patient With A Respiratory Infectionmayteveronica1000No ratings yet

- Post Covid Effects On Annavaha Srotas W.S.R To Manasika BhavaDocument5 pagesPost Covid Effects On Annavaha Srotas W.S.R To Manasika BhavaEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- StaffDocument2 pagesStaffandros 77No ratings yet

- Aplicações Da Ventilação Não Invasiva Na UtiDocument5 pagesAplicações Da Ventilação Não Invasiva Na UtiKaroline Pascoal Ilidio PeruchiNo ratings yet

- Remdesivir, Renal Function and Short-Term ClinicalDocument10 pagesRemdesivir, Renal Function and Short-Term ClinicaladenovitaresNo ratings yet

- The GINA 2019 Asthma Treatment Strategy For Adults and Adolescents 12... Download Scientific DiagramDocument1 pageThe GINA 2019 Asthma Treatment Strategy For Adults and Adolescents 12... Download Scientific DiagramFatih AryaNo ratings yet

- Reabilitação Após Doença Crítica de CovidDocument5 pagesReabilitação Após Doença Crítica de CovidCristina BoaventuraNo ratings yet

- COVID-19 Disease - Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome and Prone PositionDocument5 pagesCOVID-19 Disease - Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome and Prone PositionlacundekkengNo ratings yet

- High Incidence of Barotrauma in Patients With Severe Coronavirus Disease 2019Document9 pagesHigh Incidence of Barotrauma in Patients With Severe Coronavirus Disease 2019AMBUJ KUMAR SONINo ratings yet

- Jurnal 1Document3 pagesJurnal 1RyuuzoraNo ratings yet

- Telerehab InterventionDocument12 pagesTelerehab InterventionNelson LoboNo ratings yet

- Review: Key MessagesDocument12 pagesReview: Key MessagesLuis Fernando PantojaNo ratings yet

- Papers Intervencion CovidDocument6 pagesPapers Intervencion Coviddayllyn iglesiasNo ratings yet

- COPD Stepwise DigitalDocument1 pageCOPD Stepwise DigitalJeff CrocombeNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 0099176720304220Document10 pagesPi Is 0099176720304220yasintameganabilaNo ratings yet

- Asma China 2014Document9 pagesAsma China 2014Diego CedamanosNo ratings yet

- 21 - COVID 19 Vaccine Clinical Guidance Rheumatic Diseases SummaryDocument8 pages21 - COVID 19 Vaccine Clinical Guidance Rheumatic Diseases SummaryAnna RiztyNo ratings yet

- Post Op Pul ComplicationDocument10 pagesPost Op Pul ComplicationxxxvrgntNo ratings yet

- Joint-statement-role-RR COVID 19 E CliniDocument17 pagesJoint-statement-role-RR COVID 19 E CliniuzairNo ratings yet

- International Standards For Tuberculosis Care (2) 2006Document16 pagesInternational Standards For Tuberculosis Care (2) 2006Udsanee SukpimonphanNo ratings yet

- Archivo Covid 2Document4 pagesArchivo Covid 2Jorge Ferney Pineda BertelNo ratings yet

- Proof: Intubation and Ventilation Amid The COVID-19 OutbreakDocument16 pagesProof: Intubation and Ventilation Amid The COVID-19 OutbreakIgnacio Luis Ernesto Sepúlveda CabezasNo ratings yet

- Long Term Complications and Rehabilitation of COVID-19 PatientsDocument5 pagesLong Term Complications and Rehabilitation of COVID-19 Patientsmathias kosasihNo ratings yet

- Manejo de Ventilacion Covid 19Document16 pagesManejo de Ventilacion Covid 19FRANZ DE ARMASNo ratings yet

- Long Covid - The Long Covid Book for Clinicians and Sufferers - Away from Despair and Towards UnderstandingFrom EverandLong Covid - The Long Covid Book for Clinicians and Sufferers - Away from Despair and Towards UnderstandingNo ratings yet

- Fecal-Oral Transmission of Sars-Cov-2 in ChildrenDocument2 pagesFecal-Oral Transmission of Sars-Cov-2 in ChildrenElena Evelyng CastellanosNo ratings yet

- COVID 19 in Neonates and Infants Progression And.96180Document2 pagesCOVID 19 in Neonates and Infants Progression And.96180Elena Evelyng CastellanosNo ratings yet

- Coronavirus Disease 2019 COVID 19 and Pregnancy .97349Document4 pagesCoronavirus Disease 2019 COVID 19 and Pregnancy .97349Elena Evelyng CastellanosNo ratings yet

- Coronavirus Disease 2019 COVID 19 and Pregnancy .2Document4 pagesCoronavirus Disease 2019 COVID 19 and Pregnancy .2Elena Evelyng CastellanosNo ratings yet

- Cultural Health Beliefs in A Rural Family Practices A Malaysian PerepectiveDocument7 pagesCultural Health Beliefs in A Rural Family Practices A Malaysian Perepectivemohdrusydi100% (1)

- Hba1C Direct With Calibrator: 30 Days at 2-8°C. Do Not FreezeDocument2 pagesHba1C Direct With Calibrator: 30 Days at 2-8°C. Do Not FreezeSanjay KumarNo ratings yet

- Disengagement TheoryDocument18 pagesDisengagement TheoryApril Mae Magos LabradorNo ratings yet

- Douche: By. Dhanusrii Fourth BnysDocument12 pagesDouche: By. Dhanusrii Fourth BnysN.Darshaniya100% (1)

- Voltfast: Diclofenac Potassium 50mg Powder For Oral SolutionDocument5 pagesVoltfast: Diclofenac Potassium 50mg Powder For Oral Solutionanna lauNo ratings yet

- Ebook Clinical Orthopedic Examination of A Child 1St Edition Nirmal Raj Gopinathan 2 Online PDF All ChapterDocument69 pagesEbook Clinical Orthopedic Examination of A Child 1St Edition Nirmal Raj Gopinathan 2 Online PDF All Chapterelizabeth.byrd950100% (12)

- Jurnal Integritas KulitDocument7 pagesJurnal Integritas KulitNur FaddliNo ratings yet

- History What Is STI? BackgroundDocument4 pagesHistory What Is STI? BackgroundAko Si LibroNo ratings yet

- Fibromyalgia PDFDocument5 pagesFibromyalgia PDFYalile TurkaNo ratings yet

- Nursing Self Assessment ToolkitDocument19 pagesNursing Self Assessment ToolkitJasmeet KaurNo ratings yet

- Funda Lab - Prelim ReviewerDocument16 pagesFunda Lab - Prelim ReviewerNikoruNo ratings yet

- AngioedemaDocument15 pagesAngioedemaYuni IHNo ratings yet

- HallucinogensDocument18 pagesHallucinogensDavyne Nioore Gabriel100% (1)

- Median, Ulnar and Radial Nerve Injuries: University of Baghdad Al-Kindy College of Medicine Fifth Stage / Group ADocument13 pagesMedian, Ulnar and Radial Nerve Injuries: University of Baghdad Al-Kindy College of Medicine Fifth Stage / Group ANoor Al Zahraa AliNo ratings yet

- Anti Asthmatic DrugsDocument8 pagesAnti Asthmatic DrugsNavjot BrarNo ratings yet

- (2020) Primary Dysmenorrhea Diagnosis and TherapyDocument12 pages(2020) Primary Dysmenorrhea Diagnosis and TherapyEderEscamillaVelascoNo ratings yet

- Answer Key: Vital Signs and MonitoringDocument1 pageAnswer Key: Vital Signs and Monitoringmaglit777No ratings yet

- Pharmacokinetics of Drugs in Pregnancy and Lactation Capitulo 31Document23 pagesPharmacokinetics of Drugs in Pregnancy and Lactation Capitulo 31Marylin Acuña HernándezNo ratings yet

- PMVE-002: Pharmacology and ToxicologyDocument4 pagesPMVE-002: Pharmacology and ToxicologySwapnilPagareNo ratings yet

- Application Form Residency & PostRes 2022Document2 pagesApplication Form Residency & PostRes 2022Franz LibreNo ratings yet

- 206897hair Transplant in Turkey ClinicDocument3 pages206897hair Transplant in Turkey ClinichairtransplantmailtronlineabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxNo ratings yet

- Anello2019 PDFDocument2 pagesAnello2019 PDFandreiNo ratings yet

- 2001 Yorkston KM - Evidence-Based Practice Guidelines For Dysarthria Management of Velopharyngeal FunctionDocument18 pages2001 Yorkston KM - Evidence-Based Practice Guidelines For Dysarthria Management of Velopharyngeal FunctionPaulo César Ferrada VenegasNo ratings yet

- Pain Management - 03-07 VersionDocument51 pagesPain Management - 03-07 VersionanreilegardeNo ratings yet

- Hypocalcemia in NewbornsDocument2 pagesHypocalcemia in NewbornsEunice Lan ArdienteNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2589555921000793 MainDocument10 pages1 s2.0 S2589555921000793 Mainelektifppra2022No ratings yet

- Necrotizing Enterocolitis: Pathology and PathogenesisDocument3 pagesNecrotizing Enterocolitis: Pathology and PathogenesisJemarey DeramaNo ratings yet

Early Acute Respiratory Support For Pregnant.97381

Early Acute Respiratory Support For Pregnant.97381

Uploaded by

Elena Evelyng CastellanosOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Early Acute Respiratory Support For Pregnant.97381

Early Acute Respiratory Support For Pregnant.97381

Uploaded by

Elena Evelyng CastellanosCopyright:

Available Formats

Current Commentary

Early Acute Respiratory Support for Pregnant

Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019

(COVID-19) Infection

Luis D. Pacheco, MD, Antonio F. Saad, MD, and George Saade, MD

Downloaded from https://journals.lww.com/greenjournal by BhDMf5ePHKav1zEoum1tQfN4a+kJLhEZgbsIHo4XMi0hCywCX1AWnYQp/IlQrHD3+5UxwP5IFlCULyMzHVv2IR5yFgTmKCwRlFLuAarAlp0= on 05/09/2020

suggest starting oxygen therapy with peripheral SpO2

The present coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pan-

levels below 92% and recommend its use when levels

demic is affecting pregnant patients worldwide. Although

are below 90%.2 Based on physiologic changes in preg-

it appears that the severity of disease is reduced in

nancy (eg, increased oxygen demand and a physiologic

pregnant patients, some are likely to develop severe

disease. Our objective is to summarize the basic initial

increase in partial pressure of oxygen), we suggest start-

respiratory support interventions recommended for ing oxygen therapy in pregnant patients when SpO2

pregnant patients with infection with the severe acute values fall below 94%. Therapy should be titrated to

respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). avoid SpO2 levels above 96%.2 Once oxygen supple-

(Obstet Gynecol 2020;00:1–4) mentation is initiated, obstetricians should involve

DOI: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003929 personnel expert in airway management (eg, an anes-

thesiologist) in case endotracheal intubation is required

D

later. Together with oxygen therapy, asking the patient

espite the fact that most pregnant patients with

to lay down in bed prone (awake self-prone position)

coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection

appears to improve oxygenation (likely by anterior dis-

are likely to have only mild disease, some may require

placement of the mediastinum and improved posterior

some immediate form of respiratory support.1

lung recruitment).3 The latter may be considered in

pregnant patients at less than 20 weeks of gestation.

OXYGEN THERAPY

The initial intervention for hypoxemic pregnant pa-

tients with COVID-19 infection is administration of FLUID THERAPY

oxygen therapy. This may be accomplished by the use It is common practice to limit fluids in patients with

of a conventional nasal cannula or a facemask. Com- respiratory failure. In patients with acute hypoxemic

monly used oxygen-delivery devices are described in respiratory failure, a conservative fluid strategy, as

Table 1. Current guidelines in nonpregnant individuals opposed to liberal fluid administration, has been

shown to reduce the number of days on mechanical

From the Division of Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Department of Obstetrics & ventilation and the number of days in the intensive

Gynecology, and the Division of Surgical Critical Care, Department of Anesthe- care unit.4 Current guidelines suggest a conservative

siology, the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, Galveston, Texas.

fluid strategy in patients with COVID-19 infection,

Editing services were provided by LeAnne Garcia in the Publication, Grant, and

Media Support Office of the Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, the Uni-

aiming for a daily negative balance of 0.5–1 L.2 Dur-

versity of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston. These services are provided to the ing pregnancy, the risk of pulmonary edema in the

authors at no cost as part of their affiliation with the department. setting of lung inflammation may be increased sec-

Each author has confirmed compliance with the journal’s requirements for ondary to increased blood volume and lower oncotic

authorship.

pressure. We recommend that maintenance fluids be

Corresponding author: Luis D. Pacheco, MD, University of Texas Medical avoided in pregnant patients with acute COVID-19

Branch at Galveston, Galveston, TX; email: ldpachec@utmb.edu.

infection and oxygen desaturation (SpO2 less than

Financial Disclosure

The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest. 94%). If daily positive fluid balances are present com-

bined with worsening respiratory status, the use of

© 2020 by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Published

by Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved. furosemide (10–20 mg intravenously every 12 hours)

ISSN: 0029-7844/20 may be indicated.

VOL. 00, NO. 00, MONTH 2020 OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY 1

© 2020 by the American College of Obstetricians

and Gynecologists. Published by Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc.

Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Table 1. Conventional Methods of Oxygen Delivery

Method Description

Conventional nasal cannula Oxygen flow of 1–6 L/min. Provides oxygen concentration between 24% and 40%.

Conventional face mask Oxygen flow should be set between 5 and 10 L/min. Avoid lower oxygen flow, because this may

result in exhaled carbon dioxide rebreathing. Usually provides oxygen concentration of 40%.

Venturi mask Similar to a conventional facemask; however, may provide a more controlled FiO2. May deliver

oxygen concentration between 24% and 50% (chosen by the operator).

Partial rebreather mask Set oxygen flow at least 10 L/min. Provides oxygen concentration of 60–70%.

Nonrebreather mask Set oxygen flow at least 10 L/min. Provides oxygen concentration of 80%.

HIGH-FLOW NASAL CANNULA rable with noninvasive positive pressure ventilation in

High-flow nasal cannula has emerged as an attractive patients with hypoxemic respiratory failure who do

alternative to treat patients with acute hypoxemic not respond to initial oxygen supplementation.

respiratory failure whose respiratory status is not Unlike noninvasive positive pressure ventilation,

improving despite conventional oxygen therapy and high-flow nasal cannula does not appear to increase

who do not have an immediate indication for endo- the risk of respiratory virus transmission (including

tracheal intubation. Patients should be hemodynam- coronavirus) compared with conventional oxygen

ically stable and able to protect the airway (normal therapy.2 This has made high-flow nasal cannula a pri-

mentation, good cough reflex with adequate clearance mary therapeutic option for patients with COVID-19

of secretions). infection.7 Once high-flow nasal cannula is initiated, it

High-flow nasal cannula is similar to a conven- is paramount to closely observe such patients for fur-

tional nasal cannula; however, oxygen flows as high ther deterioration; failure to improve respiratory sta-

as 60 L/min may be provided (air is heated and tus after 30–60 minutes of high-flow nasal cannula (or

humidified). FiO2 may also be titrated more accu- noninvasive positive pressure ventilation) treatment

rately than with a conventional nasal cannula. Com- should warrant immediate reevaluation and consider-

monly used initial parameters are a flow of 50–60 ation of endotracheal intubation and invasive

L/min with an FiO2 of 1.0 (100% oxygen). Once mechanical ventilation. Delays in recognizing early

improvement is noted, the FiO2 should be weaned failure of high-flow nasal cannula or noninvasive pos-

before the flow is decreased, because the flow pro- itive pressure ventilation may result in life-threatening

vides alveolar recruitment (high flow of air results in hypoxemia at the time of induction and intubation

3–5 cmH2O of positive pressure ventilation, keeping (especially in pregnant patients with difficult airway

more alveoli open). We recommend that, once the anatomy).

FiO2 is 0.4–0.5, the flow may be weaned gradually An adequate response usually involves an

by decreases of 5–10 L/min every 4–6 hours as tol- improvement in dyspnea, decreased tachypnea, and

erated to maintain the SpO2 level above 94%. improvement in oxygen saturation. Figure 1 depicts

The efficacy of high-flow nasal cannula compared a high-flow nasal cannula device.

with conventional oxygen therapy and noninvasive

positive pressure ventilation in the form of continuous NONINVASIVE POSITIVE

positive airway pressure or bilevel positive airway PRESSURE VENTILATION

pressure has been addressed previously.5,6 One study Noninvasive positive pressure ventilation is another

compared the three modalities in patients with acute modality commonly used in patients for whom conven-

hypoxemic respiratory failure. Although there was no tional oxygen therapy fails but who are not “sick

difference in intubation rates, mortality was lower in enough” to require tracheal intubation and invasive

the high-flow nasal cannula group.5 A recent system- mechanical ventilation. Noninvasive positive pressure

atic review and meta-analysis concluded that high- ventilation is ideal for patients with cardiogenic pulmo-

flow nasal cannula resulted in lower rates of intuba- nary edema or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

tion compared with conventional oxygen therapy and exacerbations with respiratory acidosis. Unlike high-

no difference when compared with noninvasive posi- flow nasal cannula, the use of noninvasive positive pres-

tive pressure ventilation.6 In summary, current evi- sure ventilation may be associated with an increased risk

dence suggests that high-flow nasal cannula is of disease transmission to health care professionals

superior to conventional oxygen therapy and compa- owing to its aerosol-generating properties.8 This makes

2 Pacheco et al Respiratory Support for Pregnant Patients With COVID-19 OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

© 2020 by the American College of Obstetricians

and Gynecologists. Published by Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc.

Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Fig. 1. High-flow nasal cannula.

Pacheco. Respiratory Support for Pregnant Patients With COVID-

19. Obstet Gynecol 2020.

high-flow nasal cannula the first-line option for patients Fig. 2. Initial respiratory management of a pregnant patient

not responding to conventional oxygen therapy but who with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection (per-

are not yet candidates for endotracheal intubation. In sonal protective equipment must be used for any interac-

resource-limited areas where high-flow nasal cannula is tion with the patient).

not available, the use of noninvasive positive pressure Pacheco. Respiratory Support for Pregnant Patients With COVID-

ventilation may be considered.2 19. Obstet Gynecol 2020.

NEBULIZED TREATMENTS

The use of unnecessary nebulized treatments and nula, we suggest a daily nonstress test as opposed to

sputum-inducing agents should be minimized in continuous monitoring in an attempt to limit repetitive

patients with COVID-19 infection, because they exposure of nursing personnel (eg, needing to adjust

increase the risk of transmission to health care monitors after displacement with maternal movements).

professionals.2 Needless to say, if such treatment is In pregnant patients who require endotracheal

required, ideally it should be performed in an intubation and mechanical ventilation, we suggest con-

airborne-infection isolation room, and all individuals tinuous monitoring after 28 weeks of gestation. From 24

in the room should be wearing full personal protective to 28 weeks of gestation, the decision to monitor may be

equipment. based on estimated fetal weight, neonatology capability,

maternal body habitus, and availability of personal

FETAL MONITORING AND protective equipment, among other factors. If the

DELIVERY CONSIDERATIONS pregnant patient’s respiratory status deteriorates, requir-

It is commonly accepted, based on extremely limited ing maximal ventilatory settings, especially after 28

data, that delivery does not improve the respiratory weeks of gestation, we recommend proceeding with

status of pregnant patients with acute respiratory a controlled delivery (likely cesarean) instead of awaiting

failure.9 Before 23–24 weeks of gestation, we do not fetal distress from refractory hypoxemia and needing an

recommend electronic fetal monitoring for pregnant emergent delivery in the intensive care unit.

patients with COVID-19–related respiratory failure Despite having no data on the use of steroids for

given that the risks of an emergent cesarean delivery fetal lung maturity in the setting of COVID-19

outweigh fetal benefit. Even after this gestational age, infection, current guidelines suggest the use of steroids

the decision to monitor the fetus needs to be indi- in patients with COVID-19 infection and acute

vidualized, because emergent cesarean delivery under respiratory distress syndrome. Until more data are

general anesthesia carries a significant risk to the available, we believe that the use of a single course of

mother as well as to the health care professionals. steroids to induce fetal lung maturity may be reason-

For pregnant patients who are stable on either able when indicated. Figure 2 summarizes our

conventional oxygen therapy or high-flow nasal can- recommendations.

VOL. 00, NO. 00, MONTH 2020 Pacheco et al Respiratory Support for Pregnant Patients With COVID-19 3

© 2020 by the American College of Obstetricians

and Gynecologists. Published by Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc.

Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

REFERENCES 6. Ni YN, Luo J, Yu H, Liu D, Ni Z, Cheng J, et al. Can high-flow

nasal cannula reduce the rate of endotracheal intubation in adult

1. Breslin N, Baptiste C, Gyamfi-Bannerman C, Miller R, Martinez R,

patients with acute respiratory failure compared with conven-

Bernstein K, et al. COVID-19 infection among asymptomatic and

tional oxygen therapy and noninvasive positive pressure venti-

symptomatic pregnant women: two weeks of confirmed presenta-

lation?: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest 2017;151:

tions to an affiliated pair of New York City hospitals. Am J Obstet

764–75.

Gynecol 2020. [Epub ahead of print].

7. Matthay MA, Aldrich JM, Gotts JE. Treatment for severe acute

2. Alhazzani W, Møller MH, Arabi YM, Loeb M, Gong MN, Fan E,

respiratory distress syndrome from COVID-19. Lancet Respir

et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: guideline on the management of

Med 2020. [Epub ahead of print].

critically ill adults with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

Crit Care Med 2020. [Epub ahead of print]. 8. Tran K, Cimon K, Severn M, Pessoa-Silva CL, Conly J. Aerosol

generating procedures and risk of transmission of acute respira-

3. Sun Q, Qiu H, Huang M, Yang Y. Lower mortality of COVID-

tory infections to healthcare workers: a systematic review. PLoS

19 by early recognition and intervention: experience from Jiang-

One 2012;7:e35797.

su Province. Ann Intensive Care 2020;10:33.

9. Lapinsky SE. Management of acute respiratory failure in preg-

4. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Acute Respiratory

nancy. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2017;38:201–7.

Distress Syndrome (ARDS) Clinical Trials Network, Wiede-

mann HP, Wheeler AP, Bernard GR, Thompson BT, Hayden

D, et al. Comparison of two fluid-management strategies in acute

lung injury. N Engl J Med 2006;354:2564–75. PEER REVIEW HISTORY

5. Frat JP, Thille AW, Mercat A, Girault C, Ragot S, Perbet S, et al. Received April 15, 2020. Received in revised form April 20, 2020.

High-flow oxygen through nasal cannula in acute hypoxemic Accepted April 21, 2020. Peer reviews and author correspondence

respiratory failure. N Engl J Med 2015;372:2185–96. are available at http://links.lww.com/AOG/B886.

4 Pacheco et al Respiratory Support for Pregnant Patients With COVID-19 OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

© 2020 by the American College of Obstetricians

and Gynecologists. Published by Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc.

Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

You might also like

- (Bay) Soapie-NcpDocument19 pages(Bay) Soapie-NcpAJ BayNo ratings yet

- The Human Circulatory System: Grade 9 - Sussex - Wennappuwa - ScienceDocument23 pagesThe Human Circulatory System: Grade 9 - Sussex - Wennappuwa - ScienceSwarnapaliliyanageNo ratings yet

- Ultimate Exercise Cheat Sheet - TricepsDocument13 pagesUltimate Exercise Cheat Sheet - TricepsAHMED EMADNo ratings yet

- Bronchopulmonary DysplasiaDocument17 pagesBronchopulmonary DysplasiasnphNo ratings yet

- Influenza Guidelines - 25april 2023 FinalDocument32 pagesInfluenza Guidelines - 25april 2023 FinalQalbiNo ratings yet

- Soluciones de VIDocument2 pagesSoluciones de VILailaNo ratings yet

- Acute Respiratory Failure and Mechanical Ventilation in Women With COVID-19 During PregnancyDocument10 pagesAcute Respiratory Failure and Mechanical Ventilation in Women With COVID-19 During PregnancyJose Francisco Zamora ScottNo ratings yet

- Acog Prono EmbarazoDocument3 pagesAcog Prono EmbarazoRenzo del Oscar Cruz CaldasNo ratings yet

- The Central Role of Clinical Nutrition in COVID-19 Patients During and After Hospitalization in Intensive Care UnitDocument5 pagesThe Central Role of Clinical Nutrition in COVID-19 Patients During and After Hospitalization in Intensive Care UnitReaz MorshedNo ratings yet

- Treatment of Coronavirus Disease 2019.4Document5 pagesTreatment of Coronavirus Disease 2019.4Gaby VillasmilNo ratings yet

- EditDocument10 pagesEditParamitha HarmanNo ratings yet

- Jama Murthy 2020 It 200008Document2 pagesJama Murthy 2020 It 200008jorgeNo ratings yet

- Assoalho Pelvico em Tempos de Covid19Document8 pagesAssoalho Pelvico em Tempos de Covid19Silas CristianoNo ratings yet

- WHO COVID-19-Home-Care-BundleDocument2 pagesWHO COVID-19-Home-Care-BundleOCSAF - P2LT PUNSALAN MCNo ratings yet

- Efects of Short-Term Breathing Exercises On Respiratory Recovery in Patients With COVID-19: A Quasi-Experimental StudyDocument10 pagesEfects of Short-Term Breathing Exercises On Respiratory Recovery in Patients With COVID-19: A Quasi-Experimental StudymrsikazweNo ratings yet

- Critical Care of Patient With Covid 19Document32 pagesCritical Care of Patient With Covid 19Anonymous Kv0sHqFNo ratings yet

- Care For Critically Ill Patients With COVID-19: Clinical UpdateDocument2 pagesCare For Critically Ill Patients With COVID-19: Clinical UpdateNicole BatistaNo ratings yet

- Corticosteroids in The Management of Pregnant.26Document4 pagesCorticosteroids in The Management of Pregnant.26Luciana Salomé Bravo QuintanillaNo ratings yet

- Nutrients: Nutritional Interventions For COVID-19: A Role For Carnosine?Document5 pagesNutrients: Nutritional Interventions For COVID-19: A Role For Carnosine?Stalin ChandrasekaranNo ratings yet

- I PREVENT COVID FLU RSV SummaryDocument3 pagesI PREVENT COVID FLU RSV SummaryServaas OostrikNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 2213219820313970Document4 pagesPi Is 2213219820313970cuvinhNo ratings yet

- Covid JCDRDocument4 pagesCovid JCDRRoyalelectronics IndiaNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Efficacy of Dexamethasone and Methylprednisolone in Improving Pao2/Fio2 Ratio Among Covid-19 PatientsDocument7 pagesComparison of Efficacy of Dexamethasone and Methylprednisolone in Improving Pao2/Fio2 Ratio Among Covid-19 PatientsNivedanSahayNo ratings yet

- Mja2 50598Document10 pagesMja2 50598Andi Astrid AmaliaNo ratings yet

- Consensus Statement: Safe Airway Society Principles of Airway Management and Tracheal Intubation Specific To The COVID-19 Adult Patient GroupDocument10 pagesConsensus Statement: Safe Airway Society Principles of Airway Management and Tracheal Intubation Specific To The COVID-19 Adult Patient GroupMeska AmeliaNo ratings yet

- Coronavirus Disease 2019 COVID 19 and Pregnancy .2Document4 pagesCoronavirus Disease 2019 COVID 19 and Pregnancy .2Elena Evelyng CastellanosNo ratings yet

- Coronavirus Disease 2019 COVID 19 and Pregnancy .2 PDFDocument4 pagesCoronavirus Disease 2019 COVID 19 and Pregnancy .2 PDFreza1811No ratings yet

- Gibbs2020 2Document14 pagesGibbs2020 2Dan ZhouNo ratings yet

- AnnalsATS 202003-233PSDocument4 pagesAnnalsATS 202003-233PSambitiousamit1No ratings yet

- Int J Clinical Practice - 2021 - Acat - Comparison of Pirfenidone and Corticosteroid Treatments at The COVID 19 PneumoniaDocument12 pagesInt J Clinical Practice - 2021 - Acat - Comparison of Pirfenidone and Corticosteroid Treatments at The COVID 19 PneumoniaRebeca EscutiaNo ratings yet

- Treatment Strategies For Asthma: Reshaping The Concept of Asthma ManagementDocument11 pagesTreatment Strategies For Asthma: Reshaping The Concept of Asthma Managementtegarsh321No ratings yet

- Four Patients With A History of Acute Exacerbations of COPD - Implementing TheDocument7 pagesFour Patients With A History of Acute Exacerbations of COPD - Implementing TheDorothy CasumpangNo ratings yet

- The Journal For Nurse PractitionersDocument5 pagesThe Journal For Nurse Practitionersagstri lestariNo ratings yet

- Accepted: PM&R and Pulmonary Rehabilitation For COVID-19Document25 pagesAccepted: PM&R and Pulmonary Rehabilitation For COVID-19Natalie Zapata CarreraNo ratings yet

- CARTA A FAVORPotential Benefits of Precise Corticosteroids Therapy For Severe EXCELENTEDocument3 pagesCARTA A FAVORPotential Benefits of Precise Corticosteroids Therapy For Severe EXCELENTEWilson Marcial Guzman AguilarNo ratings yet

- Re-Thinking The Early Intubation Paradigm of COVID-19: Time To Change Gears?Document4 pagesRe-Thinking The Early Intubation Paradigm of COVID-19: Time To Change Gears?Gilberto ValenciaNo ratings yet

- Presentasi Dr. Basuki Rachmad, Sp. An. KICDocument39 pagesPresentasi Dr. Basuki Rachmad, Sp. An. KICinstalasi kamar bedah RSMINo ratings yet

- Pharmacological Treatment of Patients With Mild To Moderate COVID-19: A Comprehensive ReviewDocument12 pagesPharmacological Treatment of Patients With Mild To Moderate COVID-19: A Comprehensive ReviewPhạm Trịnh Công BìnhNo ratings yet

- Approach To The Pregnant Patient With A Respiratory InfectionDocument42 pagesApproach To The Pregnant Patient With A Respiratory Infectionmayteveronica1000No ratings yet

- Post Covid Effects On Annavaha Srotas W.S.R To Manasika BhavaDocument5 pagesPost Covid Effects On Annavaha Srotas W.S.R To Manasika BhavaEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- StaffDocument2 pagesStaffandros 77No ratings yet

- Aplicações Da Ventilação Não Invasiva Na UtiDocument5 pagesAplicações Da Ventilação Não Invasiva Na UtiKaroline Pascoal Ilidio PeruchiNo ratings yet

- Remdesivir, Renal Function and Short-Term ClinicalDocument10 pagesRemdesivir, Renal Function and Short-Term ClinicaladenovitaresNo ratings yet

- The GINA 2019 Asthma Treatment Strategy For Adults and Adolescents 12... Download Scientific DiagramDocument1 pageThe GINA 2019 Asthma Treatment Strategy For Adults and Adolescents 12... Download Scientific DiagramFatih AryaNo ratings yet

- Reabilitação Após Doença Crítica de CovidDocument5 pagesReabilitação Após Doença Crítica de CovidCristina BoaventuraNo ratings yet

- COVID-19 Disease - Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome and Prone PositionDocument5 pagesCOVID-19 Disease - Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome and Prone PositionlacundekkengNo ratings yet

- High Incidence of Barotrauma in Patients With Severe Coronavirus Disease 2019Document9 pagesHigh Incidence of Barotrauma in Patients With Severe Coronavirus Disease 2019AMBUJ KUMAR SONINo ratings yet

- Jurnal 1Document3 pagesJurnal 1RyuuzoraNo ratings yet

- Telerehab InterventionDocument12 pagesTelerehab InterventionNelson LoboNo ratings yet

- Review: Key MessagesDocument12 pagesReview: Key MessagesLuis Fernando PantojaNo ratings yet

- Papers Intervencion CovidDocument6 pagesPapers Intervencion Coviddayllyn iglesiasNo ratings yet

- COPD Stepwise DigitalDocument1 pageCOPD Stepwise DigitalJeff CrocombeNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 0099176720304220Document10 pagesPi Is 0099176720304220yasintameganabilaNo ratings yet

- Asma China 2014Document9 pagesAsma China 2014Diego CedamanosNo ratings yet

- 21 - COVID 19 Vaccine Clinical Guidance Rheumatic Diseases SummaryDocument8 pages21 - COVID 19 Vaccine Clinical Guidance Rheumatic Diseases SummaryAnna RiztyNo ratings yet

- Post Op Pul ComplicationDocument10 pagesPost Op Pul ComplicationxxxvrgntNo ratings yet

- Joint-statement-role-RR COVID 19 E CliniDocument17 pagesJoint-statement-role-RR COVID 19 E CliniuzairNo ratings yet

- International Standards For Tuberculosis Care (2) 2006Document16 pagesInternational Standards For Tuberculosis Care (2) 2006Udsanee SukpimonphanNo ratings yet

- Archivo Covid 2Document4 pagesArchivo Covid 2Jorge Ferney Pineda BertelNo ratings yet

- Proof: Intubation and Ventilation Amid The COVID-19 OutbreakDocument16 pagesProof: Intubation and Ventilation Amid The COVID-19 OutbreakIgnacio Luis Ernesto Sepúlveda CabezasNo ratings yet

- Long Term Complications and Rehabilitation of COVID-19 PatientsDocument5 pagesLong Term Complications and Rehabilitation of COVID-19 Patientsmathias kosasihNo ratings yet

- Manejo de Ventilacion Covid 19Document16 pagesManejo de Ventilacion Covid 19FRANZ DE ARMASNo ratings yet

- Long Covid - The Long Covid Book for Clinicians and Sufferers - Away from Despair and Towards UnderstandingFrom EverandLong Covid - The Long Covid Book for Clinicians and Sufferers - Away from Despair and Towards UnderstandingNo ratings yet

- Fecal-Oral Transmission of Sars-Cov-2 in ChildrenDocument2 pagesFecal-Oral Transmission of Sars-Cov-2 in ChildrenElena Evelyng CastellanosNo ratings yet

- COVID 19 in Neonates and Infants Progression And.96180Document2 pagesCOVID 19 in Neonates and Infants Progression And.96180Elena Evelyng CastellanosNo ratings yet

- Coronavirus Disease 2019 COVID 19 and Pregnancy .97349Document4 pagesCoronavirus Disease 2019 COVID 19 and Pregnancy .97349Elena Evelyng CastellanosNo ratings yet

- Coronavirus Disease 2019 COVID 19 and Pregnancy .2Document4 pagesCoronavirus Disease 2019 COVID 19 and Pregnancy .2Elena Evelyng CastellanosNo ratings yet

- Cultural Health Beliefs in A Rural Family Practices A Malaysian PerepectiveDocument7 pagesCultural Health Beliefs in A Rural Family Practices A Malaysian Perepectivemohdrusydi100% (1)

- Hba1C Direct With Calibrator: 30 Days at 2-8°C. Do Not FreezeDocument2 pagesHba1C Direct With Calibrator: 30 Days at 2-8°C. Do Not FreezeSanjay KumarNo ratings yet

- Disengagement TheoryDocument18 pagesDisengagement TheoryApril Mae Magos LabradorNo ratings yet

- Douche: By. Dhanusrii Fourth BnysDocument12 pagesDouche: By. Dhanusrii Fourth BnysN.Darshaniya100% (1)

- Voltfast: Diclofenac Potassium 50mg Powder For Oral SolutionDocument5 pagesVoltfast: Diclofenac Potassium 50mg Powder For Oral Solutionanna lauNo ratings yet

- Ebook Clinical Orthopedic Examination of A Child 1St Edition Nirmal Raj Gopinathan 2 Online PDF All ChapterDocument69 pagesEbook Clinical Orthopedic Examination of A Child 1St Edition Nirmal Raj Gopinathan 2 Online PDF All Chapterelizabeth.byrd950100% (12)

- Jurnal Integritas KulitDocument7 pagesJurnal Integritas KulitNur FaddliNo ratings yet

- History What Is STI? BackgroundDocument4 pagesHistory What Is STI? BackgroundAko Si LibroNo ratings yet

- Fibromyalgia PDFDocument5 pagesFibromyalgia PDFYalile TurkaNo ratings yet

- Nursing Self Assessment ToolkitDocument19 pagesNursing Self Assessment ToolkitJasmeet KaurNo ratings yet

- Funda Lab - Prelim ReviewerDocument16 pagesFunda Lab - Prelim ReviewerNikoruNo ratings yet

- AngioedemaDocument15 pagesAngioedemaYuni IHNo ratings yet

- HallucinogensDocument18 pagesHallucinogensDavyne Nioore Gabriel100% (1)

- Median, Ulnar and Radial Nerve Injuries: University of Baghdad Al-Kindy College of Medicine Fifth Stage / Group ADocument13 pagesMedian, Ulnar and Radial Nerve Injuries: University of Baghdad Al-Kindy College of Medicine Fifth Stage / Group ANoor Al Zahraa AliNo ratings yet

- Anti Asthmatic DrugsDocument8 pagesAnti Asthmatic DrugsNavjot BrarNo ratings yet

- (2020) Primary Dysmenorrhea Diagnosis and TherapyDocument12 pages(2020) Primary Dysmenorrhea Diagnosis and TherapyEderEscamillaVelascoNo ratings yet

- Answer Key: Vital Signs and MonitoringDocument1 pageAnswer Key: Vital Signs and Monitoringmaglit777No ratings yet

- Pharmacokinetics of Drugs in Pregnancy and Lactation Capitulo 31Document23 pagesPharmacokinetics of Drugs in Pregnancy and Lactation Capitulo 31Marylin Acuña HernándezNo ratings yet

- PMVE-002: Pharmacology and ToxicologyDocument4 pagesPMVE-002: Pharmacology and ToxicologySwapnilPagareNo ratings yet

- Application Form Residency & PostRes 2022Document2 pagesApplication Form Residency & PostRes 2022Franz LibreNo ratings yet

- 206897hair Transplant in Turkey ClinicDocument3 pages206897hair Transplant in Turkey ClinichairtransplantmailtronlineabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxNo ratings yet

- Anello2019 PDFDocument2 pagesAnello2019 PDFandreiNo ratings yet

- 2001 Yorkston KM - Evidence-Based Practice Guidelines For Dysarthria Management of Velopharyngeal FunctionDocument18 pages2001 Yorkston KM - Evidence-Based Practice Guidelines For Dysarthria Management of Velopharyngeal FunctionPaulo César Ferrada VenegasNo ratings yet

- Pain Management - 03-07 VersionDocument51 pagesPain Management - 03-07 VersionanreilegardeNo ratings yet

- Hypocalcemia in NewbornsDocument2 pagesHypocalcemia in NewbornsEunice Lan ArdienteNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2589555921000793 MainDocument10 pages1 s2.0 S2589555921000793 Mainelektifppra2022No ratings yet

- Necrotizing Enterocolitis: Pathology and PathogenesisDocument3 pagesNecrotizing Enterocolitis: Pathology and PathogenesisJemarey DeramaNo ratings yet