Professional Documents

Culture Documents

It's Not Just Lunch: Extra-Pair Commensality Can Trigger Sexual Jealousy

It's Not Just Lunch: Extra-Pair Commensality Can Trigger Sexual Jealousy

Uploaded by

Nataly MoraOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

It's Not Just Lunch: Extra-Pair Commensality Can Trigger Sexual Jealousy

It's Not Just Lunch: Extra-Pair Commensality Can Trigger Sexual Jealousy

Uploaded by

Nataly MoraCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/229083315

It’s Not Just Lunch: Extra-Pair Commensality Can Trigger Sexual Jealousy

Article in PLoS ONE · July 2012

DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040445 · Source: PubMed

CITATIONS READS

21 102

2 authors, including:

Brian Wansink

Cornell University

550 PUBLICATIONS 20,025 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Behavioral Economics View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Brian Wansink on 03 April 2015.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

It’s Not Just Lunch: Extra-Pair Commensality Can Trigger

Sexual Jealousy

Kevin M. Kniffin*, Brian Wansink

Dyson School of Applied Economics and Management, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York, United States of America

Abstract

Do people believe that sharing food might involve sharing more than just food? To investigate this, participants were asked

to rate how jealous they (Study 1) – or their best friend (Study 2) – would be if their current romantic partner were

contacted by an ex-romantic partner and subsequently engaged in an array of food- and drink-based activities. We

consistently find – across both men and women – that meals elicit more jealousy than face-to-face interactions that do not

involve eating, such as having coffee. These findings suggest that people generally presume that sharing a meal enhances

cooperation. In the context of romantic pairs, we find that participants are attuned to relationship risks that extra-pair

commensality can present. For romantic partners left out of a meal, we find a common view that lunch, for example, is not

‘‘just lunch.’’

Citation: Kniffin KM, Wansink B (2012) It’s Not Just Lunch: Extra-Pair Commensality Can Trigger Sexual Jealousy. PLoS ONE 7(7): e40445. doi:10.1371/

journal.pone.0040445

Editor: Petter Holme, Umeå University, Sweden

Received March 13, 2012; Accepted June 7, 2012; Published July 11, 2012

Copyright: ß 2012 Kniffin, Wansink. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits

unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding: There was no external funding for the current studies.

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

* E-mail: kmk276@cornell.edu

Introduction appear to become more jealous about physical cheating and

women tend to be more jealous about emotional cheating.

‘‘It’s Just Lunch’’ is the name of a matchmaking service that Evolutionary psychologists contend that such a pattern makes

aims to attract potential subscribers with the idea that lunch sense since men – whose role in reproduction is less certain –

provides a non-threatening environment to meet an unfamiliar would sensibly respond more to physical cheating to help ensure

person who shares interest to develop a romantic relationship. Of their paternity of any offspring whereas women tend to respond

course, against the backdrop of studies that substantiate the more to the diversion of attention or resources that might be

importance of commensality – or eating together – within families entailed by emotional cheating [9].

[1,2] and romantic pairs [3–5], it is reasonable to question Commensality is interesting to consider in this context since

whether a meal such as lunch is really just about lunch. In light of eating together involves physical and social components. Most

recognizing that commensality is part of the fabric of people’s most generally, we apply a functional view of jealousy and hypothesize

intimate relationships, it becomes clear that the practice of eating that if extra-pair commensality elicits relatively jealous reactions,

together might have functional significance beyond the concurrent then it suggests that people are evolved to recognize that eating

consumption of calories. together tends to involve, or perhaps lead to, something ‘‘more

Given that communal food procurement, preparation, and than food.’’ More specifically, our studies contribute new subtlety

eating are considered quintessential human activities [6], it is to debates concerning jealousy since our stimuli are not restricted

interesting to recognize that modern technology – such as to contrasts between physical and emotional affairs. For example,

refrigerators and microwaves – and specialized businesses – such while evolutionary psychology predicts that men will tend to

as restaurants and pizza delivery – have unbundled food respond more strongly than women to their mates engaging in

procurement and preparation from consumption. Nevertheless, ‘‘extra-pair copulations’’ [13] – a term that is borrowed from

even though resources exist today to permit eating alone, it biological field studies, our consideration of extra-pair commens-

continues to be a normal practice for people to eat in groups [7,8]. ality broadens the set of activities that might stimulate jealousy

Focusing on romantic pairs, previous researchers have document- within romantic pair bonds. While we could have investigated the

ed the importance of food for courtship and explored questions degree to which jealousy is elicited by other extra-pair activities

relating to specific preferences for type of cuisine, price, and home such as night-club-dancing with someone other than one’s

or restaurant locations [3–5]. romantic partner, we focused on more mundane activities such

In this paper, we explore the degree to which ‘‘extra-pair as eating and drinking since people tend to eat and drink several

commensality’’ – eating without one’s current romantic partner times each day.

with one or more other people – might elicit jealousy and whether

it varies between men and women. While there are robust debates Food Sharing and Social Behavior

concerning the degree to which jealousy is an emotional While food consumption has been heavily studied in relation to

adaptation that helps people guard against cheaters [9–12], the physical outcomes such as weight gain [7,8], it is relatively novel

disagreements have focused on a general pattern whereby men for close attention to be paid to the influence of food upon social

PLoS ONE | www.plosone.org 1 July 2012 | Volume 7 | Issue 7 | e40445

Extra-Pair Commensality

behavior. Among the experiments that have explored this topic, they would respond to hypothetical conditions involving their

Williams and Bargh [14] report that the receipt of warm beverages boyfriend engaging in communication with his ex-girlfriend.

appears to elicit favorable perceptions. Less favorably, researchers Participants were then asked for each question ‘‘On a scale of 1

have found that diet soda consumption appears to contribute to to 5, please estimate how jealous you would be,’’ with 1 equal to

impulsiveness [15] and non-diet soda consumption appears – in a ‘‘Not at all Jealous’’ and 5 equal to ‘‘Very Jealous.’’

survey of urban high school students – to influence the rate of

antisocial behaviors [16]. In a related observational study of Results

judges, Danziger, Levav, and Avnaim-Pesso [17] found that Remarkably, no significant sex differences existed for any of the

judgments were significantly more lenient immediately following conditions and we consequently report means in the upper row of

meal breaks in contrast with decisions that were issued immedi- Table 1 for the full sample. Unsurprisingly, participants estimated

ately prior to meal breaks. higher degrees of jealousy for direct communications. For

Our studies build upon previous research by extending the example, Phone communications elicited significantly more

hypothesis that people regard the communal consumption of food jealousy than Email correspondence (t = 26.01, p,.001).

to have functional significance for social relationships. More With respect to the four eating and drinking vignettes, Lunch

specifically, if commensality were regarded implicitly as a bonding elicited significantly more jealousy than Late Morning Coffee

mechanism, then we would expect that extra-pair commensality

(t = 22.97, p,.01) and Late Afternoon Coffee sparked more

would trigger jealousy within romantic pairs. If commensality were

jealousy than Late Morning Coffee (t = 23.49, p = .001). When

regarded as nothing more than the concurrent, co-located

we collapsed the two coffee and meal variants, we find that Meals

consumption of food, then we would expect that extra-pair

elicit significantly more jealousy than Coffees (t = 2.16, p = .034),

commensality would trigger as much jealousy as other forms of

Meals elicits more than Phone conversations (t = 2.34, p = .022),

face-to-face interaction, such as meeting for coffee.

and Coffees do not elicit more jealousy than Phone conversations.

Moreover, if extra-pair commensality were regarded as

something that is potentially threatening to one’s romantic

relationship, then we can infer – if we accept a common model Experiment 2

of sex-specific patterns of jealousy [9] – that men will react more Independent from researchers arguing that jealousy might serve

strongly than women if eating together is viewed as physical and socially functional or adaptive purposes, common sentiments tend

women will react more strongly if commensality is viewed as to regard jealousy as an undesirable trait [18,19]. With this

primarily emotional or social. background, we conducted a second set of studies to address

concerns about response bias by asking participants to estimate

Ethics Statement how their best friends would respond to the same set of conditions.

For each of the studies that we conducted, participants provided

informed consent orally since our commitment to conduct Method

anonymous analyses did not require written consent. Participants 74 undergraduate students (51 females) at a private university in

acknowledged their understanding of the consent process through the Northeastern United States participated in this study in

gestures and we reminded them that they could end their exchange for partial fulfillment of course credit and a nominal cash

participation at any point during the study without penalty. incentive. 59 participants were between 18 and 22 years old; 9

Our consent form and procedures were approved by the were 23 to 29 years old; 2 were 30 to 39; and, 4 were 40 or older.

Cornell University Institutional Review Board (IRB). The use of

In randomized order, participants were presented the same

verbal consent was approved by the Cornell University IRB and

vignettes with the modification that people were asked to estimate

no written consent form was needed.

how their ‘‘best same-sex friend’’ would respond if his or her

romantic partner engaged in the six activities. As with Study 1,

Experiment 1 male and female participants each received sex-specific questions

Method in which males were asked to estimate how their best male friend

79 undergraduate students (52 males) at a private university in would respond if his girlfriend engaged in communications with

the Northeastern United States participated in this study in her ex-boyfriend and female participants in the study were asked

exchange for a nominal cash incentive. 96.2% of the respondents to estimate how their best female friend would respond if her

reported ages between 18 and 22 years old. boyfriend engaged in communications with his ex-girlfriend.

Participants were informed that ‘‘the next six questions ask you

to imagine how you would react to a variety of hypothetical Results

vignettes’’ and asked ‘‘Consequently, please use your imagination As with Study 1, we did not find sex differences for any

to respond as if the hypothetical event really happened.’’ condition and consequently we report the averages for our full

In randomized order, participants were presented with six sample in the lower row of Table 1. Consistent with response bias

vignettes that each started by noting that ‘‘Recently, your concerns that motivated us to conduct both studies, the average

[romantic partner] was contacted by his/her ex-[romantic self-reported ratings are nominally higher for all six conditions.

partner] and she/he spent approximately one hour’’ (1) corre- Likewise, we replicate the finding that Phone conversations elicits

sponding via email, (2) talking on the phone, (3) meeting for late- more jealousy than Email correspondence (t = 24.90, p,.0001).

morning coffee, (4) meeting for a late-morning meal (or Lunch), (5) More specifically, Dinner draws significantly more jealousy than

meeting for late-afternoon coffee, and (6) meeting for a late- Late Afternoon Coffee (t = 3.94, p,.0001) just as Dinner also

afternoon meal (or Dinner). elicits significantly more jealousy than Lunch (t = .272, p,.01).

In order to personalize the vignettes, male participants were Additionally, we find that Meals elicit more jealousy than Coffees

asked to rate how they would respond to hypothetical conditions (t = 2.72, p,.01) and no significant differences exist between

involving their girlfriend engaging in communication with her ex- Meals and Phone or Coffees and Phone conversations.

boyfriend. Likewise, female participants were asked to rate how

PLoS ONE | www.plosone.org 2 July 2012 | Volume 7 | Issue 7 | e40445

Extra-Pair Commensality

Table 1. Average Jealousy Ratings Estimated for Each Scenario (and Standard Deviations).

Late Morning Late Afternoon

Email Correspondence Phone Conversation Coffee Lunch Coffee Dinner

Self-Reported 2.92 (1.15) 3.37 (1.15) 3.33 (1.19) 3.49 (1.19) 3.51 (1.13) 3.57 (1.17)

Jealousy [Study 1]

Best Friend’s 2.93 (1.15) 3.53 (1.13) 3.49 (1.19) 3.61 (1.15) 3.58 (1.24) 3.86 (1.16)

Jealousy [Study 2]

1 = Not at all Jealous and 5 = Very Jealous.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0040445.t001

Discussion ied as a tool for developing and strengthening social relationships.

For example, while the existence of heterosexual romantic

While our findings concerning Phone and Email communica- relationships poses no puzzle to evolutionary psychologists, our

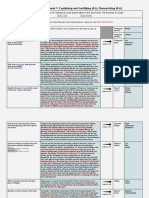

tions are unsurprising, Figure 1 illustrates the interesting pattern studies highlight a candidate mechanism for researchers seeking to

whereby Meals consistently elicit more jealousy than face-to-face understand why genetically unrelated non-kin competitors often

interactions (i.e., Coffees) that do not involve food. These findings opt to cooperate with each other [20–23]. Among other potential

suggest that people believe that commensality involves more than domains where commensality might be closely studied as a

the physical consumption of calories. More specifically, the pattern mechanism for community building, Wilson, Kauffman, and

across both studies suggests that people are attuned to the potential Purdy [24] identify communal eating of meals in a special high

relationship threat that they implicitly expect can be posed by school for at-risk students as part of a success-generating cultural

extra-pair commensality. environment.

Against the backdrop of previous studies concerning jealousy, Of two primary limitations with our studies, the first involves

the absence of sex differences is notable. Given the importance of our reliance on ratings from relatively homogenous samples of

understanding jealousy in relation to aggression [11] and given participants – undergraduate students enrolled at a private

previous studies that have highlighted sex differences, our findings university in the Northeastern United States. As a consequence,

of common attitudes about commensality are helpful. In future studies conducted with more heterogeneous groups of

particular, we can provisionally infer from our studies that people people will be necessary to test the generalizability of our findings.

view commensality as an interaction that involves a mix of physical For example, it is plausible that different patterns would emerge if

and emotional exchanges. these questions were presented to different subgroups within the

Against the backdrop of studies that treat cooperation as a United States and, more broadly, different cultural groups across

puzzle that requires explanation [20–23], our findings highlight a the globe where values related to meals and jealousy are certain to

mechanism – commensality – that has been relatively understud- vary [25].

A second limitation of our studies involves the fact that our

stimuli consistently presented the prospect of one’s current

romantic partner eating, drinking, or communicating with a

former romantic partner. Future studies will need to test the extent

to which comparable patterns might exist when one’s current

romantic partner eats, drinks, or communicates with a potential

romantic partner with whom there is no history of romance. For

example, it should not be assumed that jealousy would be elicited if

a person learned that their romantic partner ate lunch with a

newly hired co-worker and it is unlikely that jealousy would be

elicited if their romantic partner ate with someone such as a

significantly older widow or widower who lives next door and does

not fit the profile of a potential romantic rival.

Beyond recommending research that addresses limitations of

this paper, our focus on the influence of eating on the nature of

social relationships opens several new lines of study. For example,

given previous research that shows the importance of non-physical

traits upon perceptions of physical attractiveness [26], it seems

plausible that strangers who eat with each other might develop

enhanced perceptions of each other’s physical attractiveness after

sharing a meal. In fact, such a pattern is the kind of evidence that

Figure 1. Average Jealousy Ratings Vary With the Social would validate the jealousy elicited in our studies as functional or

Context. When participants were asked to rate how jealous they adaptive responses to a relationship threat. More basically, while

(Study 1) or their best friend (Study 2) would be if their current romantic our studies did not find a difference between men and women with

partner engaged in an array of activities with a former romantic partner, respect to jealousy, it seems plausible that pregnant women might

meals elicited significantly more jealousy than comparably long

interactions involving coffee. Using a scale of 1 (Not At All Jealous) to

demonstrate more jealousy of their partner’s extra-pair commens-

5 (Very Jealous), participants in both studies also reacted more strongly ality if they are especially sensitive to the potential diversion of

to direct communications when compared with email. attention and resources to another person. Similarly, it might be

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0040445.g001 the case that partners who are married tend to be more jealous –

PLoS ONE | www.plosone.org 3 July 2012 | Volume 7 | Issue 7 | e40445

Extra-Pair Commensality

perhaps especially when the couple has children – when meals are Acknowledgments

shared outside of the pair bond just as it might be true that less

jealousy is elicited when both partners are employed outside the We are grateful for helpful communications with Anne Clark, Jim Detert,

William Schulze, David Sloan Wilson, and two anonymous reviewers. We

home and, consequently, less dependent on each other’s income.

thank Dan Connolly, Kevin Krieger, Charles Marquet, Kale Smith, John

Most generally, our current findings contribute to growing Taber, Diana Viglucci, Zach West, and Jubo Yan for help organizing and

interest concerning the influence of food upon individual and administering the studies. We are also grateful for participants in each of

social behavior. While the relative homogeneity of our samples the two studies.

limits the degree to which we can draw broad generalizations, our

studies suggest that the professional match-making company ‘‘It’s Author Contributions

Just Lunch’’ perhaps unknowingly benefits from implicit beliefs

about eating together that helps them to connect people. But Conceived and designed the experiments: KMK BW. Performed the

experiments: KMK. Analyzed the data: KMK BW. Contributed reagents/

moreover, our findings also suggest that a more accurate and

materials/analysis tools: KMK BW. Wrote the paper: KMK BW.

innocuous saying might be ‘‘It’s Just Coffee’’ since people seem to

view drinking coffee during the day as relatively more platonic.

References

1. Sobal J, Nelson MK (2003) Commensal Eating Patterns: A community study. 14. Williams LE, Bargh JA (2008) Experiencing Physical Warmth Promotes

Appetite 41: 181–190. Interpersonal Warmth. Science 322: 606–607.

2. Bove CF, Sobal J, Rauschenbach BS (2003) Food Choices among Newly 15. Wang XT, Dvorak RD (2010) Sweet Future: Fluctuating blood glucose levels

Married Couples: Convergence, conflict, individualism, and projects. Appetite 40: affect future discounting. Psychological Science 21: 183–188.

25–41. 16. Solnick SJ, Hemenway D (2011) The ‘Twinkie Defense’: The relationship

3. Amiraian D, Sobal J (2009) Dating and Eating: How university students select between carbonated non-diet soft drinks and violence perpetration among

eating settings. Appetite 52: 226–229. Boston high school students. Injury Prevention, doi:10.1136/injuryprev-2011-

4. Amiraian DE, Sobal J (2009) Dating and Eating: Beliefs about dating foods 040117.

among university students. Appetite 53: 226–232. 17. Danziger S, Levav J, Avnaim-Pesso L (2011) Extraneous Factors in Judicial

5. Young ME, Mizzau M, Mai NT, Sirisegaram A, Wilson M (2009) Food for Decisions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science USA 108: 6889–6892.

Thought: What you eat depends on your sex and eating companions. Appetite 53: 18. Frank RH (2007) Falling Behind: How rising inequality harms the middle class. Los

268–271. Angeles, CA: University of California Press.

6. Wrangham RE (2009) Catching Fire: How cooking made us human. New York, NY: 19. Kniffin KM (2009) Evolutionary Perspectives on Salary Dispersion within Firms.

Basic Books.

Journal of Bioeconomics 11: 23–42.

7. Wansink B (2004) Environmental Factors that Increase the Food Intake and

20. DeScioli P, Kurzban R (2009) The Alliance Hypothesis for Human Friendship.

Consumption Volume of Unknowing Consumers. Annual Review of Nutrition 24:

PLoS ONE 4(6): e5802.

455–479.

8. Wansink B (2006) Mindless Eating: Why we eat more than we think. New York, NY: 21. Kniffin KM, Wilson DS (2005) Utilities of Gossip across Organizational Levels:

Random House. Multilevel selection, free-riders, and teams. Human Nature 16, 278–292.

9. Buss DM, Larsen RJ, Westen D, Semmelroth J (1992) Sex Differences in 22. Kniffin KM, Wilson DS (2010) Evolutionary Perspectives on Workplace Gossip:

Jealousy: Evolution, physiology, and psychology. Psychological Science 3: 251–255. Why and how gossip can serve groups. Group & Organization Management 35: 150–

10. DeSteno D, Bartlett MY, Braverman J, Salovey P (2002) Sex Differences in 176.

Jealousy: Evolutionary Mechanisms or Artifact of Measurement. Journal of 23. O’Gorman R, Henrich J, van Vugt M (2009) Constraining free-riding in public

Personality and Social Psychology 83: 1103–1116. goods games: Designated solitary punishers can sustain human cooperation.

11. DeSteno D, Valdesolo P, Bartlett MY (2006) Jealousy and the threatened self: Proceedings of the Royal Society B 276: 323–329.

Getting to the heart of the green-eyed monster. Journal of Personality and Social 24. Wilson DS, Kauffman Jr RA, Purdy MS (2011) A Program for At-Risk High

Psychology 83: 1103–1116. School Students Informed by Evolutionary Science. PLoS ONE 6(11): e27826.

12. Harris CR (2000) Psychophsiological Responses to Imagined Infidelity: The 25. Henrich J, Heine SJ, Norenzayan A (2010) The weirdest people in the world?

specific innate modular view of jealousy reconsidered. Journal of Personality and Behavioral and Brain Sciences 33: 61–83.

Social Psychology 78: 1082–1091. 26. Kniffin KM, Wilson DS (2004) The Effect of Nonphysical Traits on the

13. Shackelford TK, Goetz AT (2007) Adaptation to Sperm Comeptition in Perception of Physical Attractiveness: Three naturalistic studies. Evolution and

Humans. Current Directions in Psychological Science 16: 47–50. Human Behavior 25: 88–101.

PLoS ONE | www.plosone.org 4 July 2012 | Volume 7 | Issue 7 | e40445

View publication stats

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5823)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Distress Tolerance Made Easy - Van Dijk Sheri McKay MatthewDocument154 pagesDistress Tolerance Made Easy - Van Dijk Sheri McKay MatthewNarongpong KoshagadNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Forbidden Fire by Charlotte LambDocument138 pagesForbidden Fire by Charlotte LambFatema Nulwala29% (7)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- God's Jealous Love For Us (Sermon)Document4 pagesGod's Jealous Love For Us (Sermon)tsupasatNo ratings yet

- My Last DuchessDocument13 pagesMy Last DuchessixmawelNo ratings yet

- David and SaulDocument4 pagesDavid and SaulFriska SihombingNo ratings yet

- Weebly - Pink Wachirapaet - Formative Assessment 1 - Graphic Design - All Summer in A Day 1Document3 pagesWeebly - Pink Wachirapaet - Formative Assessment 1 - Graphic Design - All Summer in A Day 1api-480730245No ratings yet

- Joshua Fields Millburn, Minimalism - Essential EssaysDocument135 pagesJoshua Fields Millburn, Minimalism - Essential EssaysJohn Leano100% (12)

- Romantic Love and Sexual ExpressionDocument9 pagesRomantic Love and Sexual ExpressionSandra SotoNo ratings yet

- 36 Dramatic SituationsDocument30 pages36 Dramatic SituationsMad Hennessy100% (1)

- The Good Prince Bantugan Story Telling Best LPDocument8 pagesThe Good Prince Bantugan Story Telling Best LPCharmine Neri100% (1)

- Best of Friends and Worst of EnemiesDocument14 pagesBest of Friends and Worst of EnemiesAlison_VicarNo ratings yet

- Ten Commandments For Peace of MindDocument3 pagesTen Commandments For Peace of MindMohamad Shuhmy ShuibNo ratings yet

- Marx Chistian SorinoDocument7 pagesMarx Chistian SorinoBisdak MarkNo ratings yet

- JEALOUSYDocument28 pagesJEALOUSYAntonija KlemencicNo ratings yet

- Undrestanding Personal RelationshipDocument56 pagesUndrestanding Personal RelationshipEdreiNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Toxic Friendship On A Person's CharacterDocument6 pagesThe Impact of Toxic Friendship On A Person's Characteranissashafa9No ratings yet

- 6 Toxic Relationships HabitsDocument5 pages6 Toxic Relationships HabitsClara Pas100% (1)

- Three's A Crowd or Bonus?: College Students' Threesome ExperiencesDocument15 pagesThree's A Crowd or Bonus?: College Students' Threesome ExperiencesMehul JainNo ratings yet

- Kopie Van Miyamoto MusashiDocument12 pagesKopie Van Miyamoto MusashipavanNo ratings yet

- SPM EssaysDocument10 pagesSPM EssaysSnsd Zibo0% (1)

- Seni Melepaskan Berhenti Berpikir Berlebihan Hentikan Spiral Negatif Dan Temukan Kebebasan Emosional Jalan Menuju KetenanganDocument170 pagesSeni Melepaskan Berhenti Berpikir Berlebihan Hentikan Spiral Negatif Dan Temukan Kebebasan Emosional Jalan Menuju KetenanganDamayanti SinagaNo ratings yet

- 4.15 Cula Kamma Vibhanga S m135 PiyaDocument7 pages4.15 Cula Kamma Vibhanga S m135 PiyaZachary ThantNo ratings yet

- Make Any Man Yours For Life SampleDocument30 pagesMake Any Man Yours For Life SampleAdre OliveiraNo ratings yet

- PILSAR Zine #1Document48 pagesPILSAR Zine #1PILSARNo ratings yet

- Conscious Enlightenment and Expansion EbookDocument149 pagesConscious Enlightenment and Expansion EbookPatriciaNo ratings yet

- Shakespeare Speaks: BBC Learning EnglishDocument5 pagesShakespeare Speaks: BBC Learning EnglishRobMi10No ratings yet

- Robert Nelson - The Art of Cold ReadingDocument50 pagesRobert Nelson - The Art of Cold ReadingTerry Weston86% (7)

- Word!Association!Test!Ebook!Part!0!2!Document54 pagesWord!Association!Test!Ebook!Part!0!2!cool Tiwari100% (1)

- Yadlosky & McVey DBT-A Emotion DictionaryDocument10 pagesYadlosky & McVey DBT-A Emotion Dictionaryemilypomer2018No ratings yet

- Shadow Work Journal Prompts Illustrated PDFDocument51 pagesShadow Work Journal Prompts Illustrated PDFkkccNo ratings yet