Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Clerici-2020-Sensitivity of SARS-CoV-2 Detecti

Clerici-2020-Sensitivity of SARS-CoV-2 Detecti

Uploaded by

Nick FloresCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Infection Control Competency QuizDocument7 pagesInfection Control Competency QuizLoo DrBrad100% (1)

- Chapter 3 - Microbiological Methods Analysis in FoodDocument68 pagesChapter 3 - Microbiological Methods Analysis in FoodPuvenez Tamalantan93% (29)

- Jurnal 2Document10 pagesJurnal 2GFORCE .ID.No ratings yet

- Lung Ultrasonography For The Diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 Pneumonia in The Emergency DepartmentDocument10 pagesLung Ultrasonography For The Diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 Pneumonia in The Emergency DepartmentFannyRivera27No ratings yet

- Ejifcc 2022 Vol 33 No 2Document139 pagesEjifcc 2022 Vol 33 No 2Georgiana Daniela DragomirNo ratings yet

- PIIS1198743X20306972Document4 pagesPIIS1198743X20306972KARLA PATRICIA DIAZ LOPEZNo ratings yet

- PEÑA2021 Performance EvaluationDocument5 pagesPEÑA2021 Performance EvaluationOliver Viera SeguraNo ratings yet

- 1.epidem I Kontrola SarsDocument7 pages1.epidem I Kontrola SarsadnanNo ratings yet

- Usefulness of High-Resolution Computed Tomography in Early Diagnosis of Patients With Suspected COVID-19Document7 pagesUsefulness of High-Resolution Computed Tomography in Early Diagnosis of Patients With Suspected COVID-19Israel Parra-OrtegaNo ratings yet

- Ijs DR 2212055Document4 pagesIjs DR 2212055Nicolas CastilloNo ratings yet

- 0 - Basti Andriyoko, DR., SPPK (K) - Diagnostik Molekuler SARS CoV2. PDS PatKLIn 20102020Document20 pages0 - Basti Andriyoko, DR., SPPK (K) - Diagnostik Molekuler SARS CoV2. PDS PatKLIn 20102020SuliarniNo ratings yet

- Reviews: Testing at Scale During The COVID-19 PandemicDocument12 pagesReviews: Testing at Scale During The COVID-19 PandemicAdrija SinghNo ratings yet

- Bulletin PDFDocument5 pagesBulletin PDFrishaNo ratings yet

- False-Negative Results of Initial RT-PCR Assays For COVID-19: A Systematic ReviewDocument19 pagesFalse-Negative Results of Initial RT-PCR Assays For COVID-19: A Systematic ReviewFre mobileNo ratings yet

- Development and Evaluation of A Rapid CRISPR-based Diagnostic For COVID-19Document12 pagesDevelopment and Evaluation of A Rapid CRISPR-based Diagnostic For COVID-19YunaNo ratings yet

- Validasi Rapid AntigenDocument6 pagesValidasi Rapid Antigengaki telitiNo ratings yet

- Ahead of Print: Establishment of Diagnostic Protocols For COVID-19 PatientsDocument6 pagesAhead of Print: Establishment of Diagnostic Protocols For COVID-19 PatientsSana AbbasNo ratings yet

- Id Now NP Rna VLDocument5 pagesId Now NP Rna VLluis achaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal MPIDocument4 pagesJurnal MPIMarini TaslimaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1198743X18308565 MainDocument6 pages1 s2.0 S1198743X18308565 MainYulia Niswatul FauziyahNo ratings yet

- Paper Grupo 5Document12 pagesPaper Grupo 5RobertoVeraNo ratings yet

- s41598 023 33824 6 PDFDocument7 pagess41598 023 33824 6 PDFscribdicinNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1472648320303187 MainDocument17 pages1 s2.0 S1472648320303187 Mainvenny2 tlm polbantenNo ratings yet

- Fimmu 11 595970Document11 pagesFimmu 11 595970Minh Anh VuNo ratings yet

- 10.1515 - DX 2020 0091Document3 pages10.1515 - DX 2020 0091trisna amijayaNo ratings yet

- Ifcc Interim Guidelines On Serological Testing of Antibodies Against Sars Cov 2Document8 pagesIfcc Interim Guidelines On Serological Testing of Antibodies Against Sars Cov 2laboratorio clinico HPASNo ratings yet

- Different Longitudinal Patterns of Nucleic Acid and Serology Testing Results Based On Disease Severity of COVID-19 PatientsDocument5 pagesDifferent Longitudinal Patterns of Nucleic Acid and Serology Testing Results Based On Disease Severity of COVID-19 PatientsagboxNo ratings yet

- Correspondence: Utility of Hyposmia and Hypogeusia For The Diagnosis of COVID-19Document2 pagesCorrespondence: Utility of Hyposmia and Hypogeusia For The Diagnosis of COVID-19Dhyo Asy-shidiq HasNo ratings yet

- Diagnostic Performance of A Sars-Cov-2 Igg/Igm Lateral Flow Immunochromatography Assay in Symptomatic Patients Presenting To The Emergency DepartmentDocument3 pagesDiagnostic Performance of A Sars-Cov-2 Igg/Igm Lateral Flow Immunochromatography Assay in Symptomatic Patients Presenting To The Emergency DepartmentWilmer UcedaNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Infectious Diseases: SciencedirectDocument8 pagesInternational Journal of Infectious Diseases: SciencedirectAntonio Barrios PerezNo ratings yet

- Predicting Infectious Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 From Diagnostic SamplesDocument4 pagesPredicting Infectious Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 From Diagnostic SamplesArum Rahmawatie VirgieNo ratings yet

- The Establishment of Reference Sequence For Sars Cov 2 and Variation AnalysisDocument8 pagesThe Establishment of Reference Sequence For Sars Cov 2 and Variation AnalysisYulaimy BatistaNo ratings yet

- Vaccination Strategy and Anti - Sars-Cov-2 S Titers in Healthcare Workers of The Int - Irccs "Fondazione Pascale" Cancer Center (Naples, Italy)Document10 pagesVaccination Strategy and Anti - Sars-Cov-2 S Titers in Healthcare Workers of The Int - Irccs "Fondazione Pascale" Cancer Center (Naples, Italy)Ioana SoraNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id3902468Document20 pagesSSRN Id3902468JaimeNo ratings yet

- Pruebas Diagnosticas Covid-19Document7 pagesPruebas Diagnosticas Covid-19JADIT YASIRA MENDOZA HERNANDEZNo ratings yet

- Development of Sars Cov 2 Viral Load Assay Using Standard Rna From in Vitro Transcript of Nucleocapsid Gene 624e8872921c0Document11 pagesDevelopment of Sars Cov 2 Viral Load Assay Using Standard Rna From in Vitro Transcript of Nucleocapsid Gene 624e8872921c0ERIE YUWITA SARINo ratings yet

- Predicting Infectious Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 From Diagnostic SamplesDocument4 pagesPredicting Infectious Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 From Diagnostic SamplesmikhaelyosiaNo ratings yet

- Quantifying The Risk of Sars Cov 2 Reinfection Over TimeDocument11 pagesQuantifying The Risk of Sars Cov 2 Reinfection Over TimeJimmy A. Camones ObregonNo ratings yet

- Covid-19 Breakthrough Infections in Vaccinated Health Care WorkersDocument11 pagesCovid-19 Breakthrough Infections in Vaccinated Health Care WorkerskajelchaNo ratings yet

- Covid19 Methods PDFDocument14 pagesCovid19 Methods PDFSulieman OmarNo ratings yet

- Mm695152a3 HDocument6 pagesMm695152a3 HKinja NinjaNo ratings yet

- Ijerph-18-11451 Meta Analysis StudyDocument14 pagesIjerph-18-11451 Meta Analysis StudySumit BediNo ratings yet

- Presence of Mismatches Between Diagnostic PCR Assays and Coronavirus Sars-Cov-2 GenomeDocument17 pagesPresence of Mismatches Between Diagnostic PCR Assays and Coronavirus Sars-Cov-2 GenomeYulaimy BatistaNo ratings yet

- Réponse Immun Covid19Document8 pagesRéponse Immun Covid19Tidiane SibyNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 20Document5 pagesJurnal 20Ahmad Fari Arief LopaNo ratings yet

- JCM 09 02870 v2Document9 pagesJCM 09 02870 v2Syaffa Sadida ZahraNo ratings yet

- Predicting Infectious Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 From Diagnostic SamplesDocument4 pagesPredicting Infectious Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 From Diagnostic SamplesmeNo ratings yet

- Supplement: Change in Saliva RT-PCR Sensitivity Over The Course of Sars-Cov-2 InfectionDocument3 pagesSupplement: Change in Saliva RT-PCR Sensitivity Over The Course of Sars-Cov-2 InfectionAdeline IntanNo ratings yet

- Use of Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence To P 2020 InternationalDocument8 pagesUse of Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence To P 2020 Internationaltshikutu bikengelaNo ratings yet

- Diagnostics For SARS-CoV-2 Infections Bhavesh D. Kevadiya1, Jatin Machhi1, Jonathan Herskovitz1,2, MaximDocument13 pagesDiagnostics For SARS-CoV-2 Infections Bhavesh D. Kevadiya1, Jatin Machhi1, Jonathan Herskovitz1,2, MaximDiego Paredes HuancaNo ratings yet

- Multicenter Evaluation of The Panbio™ COVID-19 Rapid Antigendetection Test For The Diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 InfectionDocument5 pagesMulticenter Evaluation of The Panbio™ COVID-19 Rapid Antigendetection Test For The Diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 InfectionamyNo ratings yet

- Referência 33Document10 pagesReferência 33jmaj jmajNo ratings yet

- Real-Time RT-PCR For COVID-19 Diagnosis: Challenges and ProspectsDocument3 pagesReal-Time RT-PCR For COVID-19 Diagnosis: Challenges and ProspectsAnthony StackNo ratings yet

- 001 Profiling Early Humoral Response To COVID-19 (IDSA 20) READDocument8 pages001 Profiling Early Humoral Response To COVID-19 (IDSA 20) READagboxNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0033350620301141 MainDocument3 pages1 s2.0 S0033350620301141 MainFedrik Monte Kristo LimbongNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Infectious DiseasesDocument3 pagesInternational Journal of Infectious DiseasesDetti FahmiasyariNo ratings yet

- New England Journal Medicine: The ofDocument10 pagesNew England Journal Medicine: The ofSuwandi ChangNo ratings yet

- Journal Pone 0262820Document11 pagesJournal Pone 0262820bioNo ratings yet

- COVID-19 Testing: A Reflection On Test Accuracy in The Real WorldDocument34 pagesCOVID-19 Testing: A Reflection On Test Accuracy in The Real Worldjoeboots78No ratings yet

- D'alessandro 2020Document5 pagesD'alessandro 2020Flip Flop ChartNo ratings yet

- Viruses 13 01116Document9 pagesViruses 13 01116SilviabeatoNo ratings yet

- Culture Media and MethodsDocument49 pagesCulture Media and Methodscj bariasNo ratings yet

- CDC Hiv Consumer Info Sheet Injecting Drugs 101Document2 pagesCDC Hiv Consumer Info Sheet Injecting Drugs 101Babaljeet DhaliwalNo ratings yet

- Oral Sex PamphletDocument2 pagesOral Sex PamphletsaNo ratings yet

- 1) StaphylococciDocument13 pages1) StaphylococciOmar K. FahmyNo ratings yet

- CBC COVID19 Product List 3 - 24 - 2020 PDFDocument11 pagesCBC COVID19 Product List 3 - 24 - 2020 PDFVina DevianaNo ratings yet

- Curing and Smoking Meats For Home Food PreservationDocument6 pagesCuring and Smoking Meats For Home Food PreservationJerin JamesNo ratings yet

- Intestinal Amebiasis: A Concerning Cause of Acute Gastroenteritis Among Hospitalized Lebanese ChildrenDocument9 pagesIntestinal Amebiasis: A Concerning Cause of Acute Gastroenteritis Among Hospitalized Lebanese ChildrenFrancisca OrenseNo ratings yet

- DAILY NATION Saturday July 25, 2020 PDFDocument16 pagesDAILY NATION Saturday July 25, 2020 PDFDixie CheeloNo ratings yet

- Hepatitis B: Journal ReviewDocument41 pagesHepatitis B: Journal Reviewagita kartika sariNo ratings yet

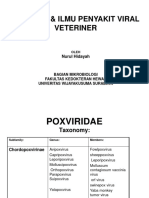

- Virologi & Ilmu Penyakit Viral Veteriner: Nurul HidayahDocument18 pagesVirologi & Ilmu Penyakit Viral Veteriner: Nurul HidayahTeoNo ratings yet

- Basic Medical Microbiology 1St Edition Patrick R Murray Full ChapterDocument67 pagesBasic Medical Microbiology 1St Edition Patrick R Murray Full Chapterjefferson.kleckner559100% (10)

- What's The Difference Between Covid-19 Rapid and PCR TestsDocument2 pagesWhat's The Difference Between Covid-19 Rapid and PCR TestsMedilife DigitalNo ratings yet

- Articulo BiologíaDocument6 pagesArticulo BiologíaJulieta Juárez OchoaNo ratings yet

- Microbiology and Parasitology Laboratory Activity No.1Document8 pagesMicrobiology and Parasitology Laboratory Activity No.1Eloisa BrailleNo ratings yet

- Ranikhet Disease of PoultryDocument22 pagesRanikhet Disease of PoultryNadineNo ratings yet

- OGUK - Flow Charts PDFDocument6 pagesOGUK - Flow Charts PDFvikrant911No ratings yet

- Autotherapy - Charles H. Duncan M. D.Document398 pagesAutotherapy - Charles H. Duncan M. D.Don FloresNo ratings yet

- Corona Virus Pandemic and Its Effects On Students788Document19 pagesCorona Virus Pandemic and Its Effects On Students788Suman MondalNo ratings yet

- Jurnal DBD PDFDocument9 pagesJurnal DBD PDFmarlinNo ratings yet

- H.I.V. Crossword PuzzleDocument3 pagesH.I.V. Crossword Puzzlejackie pascualNo ratings yet

- Avian Influenza (AI) : Synonyms DefinitionDocument16 pagesAvian Influenza (AI) : Synonyms DefinitionDr-Hassan Saeed100% (1)

- Highlight of Immune Pathogenic Response and Hematopathologic Effect in Sars-Cov, Mers-Cov, and Sars-Cov-2 InfectionDocument11 pagesHighlight of Immune Pathogenic Response and Hematopathologic Effect in Sars-Cov, Mers-Cov, and Sars-Cov-2 InfectionNandagopal PaneerselvamNo ratings yet

- Department of Genetics: Covid-19 RT PCRDocument1 pageDepartment of Genetics: Covid-19 RT PCRSahil AnsariNo ratings yet

- Foundations in Microbiology: The Gram-Positive Bacilli of Medical Importance TalaroDocument70 pagesFoundations in Microbiology: The Gram-Positive Bacilli of Medical Importance TalaroAgathaNo ratings yet

- Read The Text and Answer The QuestionsDocument3 pagesRead The Text and Answer The QuestionsSamara FernandesNo ratings yet

- Bio ProjectDocument10 pagesBio ProjectPADMESH DongreNo ratings yet

- Comprehensive Review of Infectious Diseases 1St Edition Andrej Spec Full Chapter PDFDocument69 pagesComprehensive Review of Infectious Diseases 1St Edition Andrej Spec Full Chapter PDFjeydeltaive100% (6)

- WWW Who Int News Room Fact Sheets Detail Immunization CoverageDocument6 pagesWWW Who Int News Room Fact Sheets Detail Immunization CoveragegrowlingtoyouNo ratings yet

Clerici-2020-Sensitivity of SARS-CoV-2 Detecti

Clerici-2020-Sensitivity of SARS-CoV-2 Detecti

Uploaded by

Nick FloresCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Clerici-2020-Sensitivity of SARS-CoV-2 Detecti

Clerici-2020-Sensitivity of SARS-CoV-2 Detecti

Uploaded by

Nick FloresCopyright:

Available Formats

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT

published: 26 January 2021

doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.593491

Sensitivity of SARS-CoV-2 Detection

With Nasopharyngeal Swabs

Bianca Clerici 1 , Antonio Muscatello 2 , Francesca Bai 3 , Donatella Pavanello 4 ,

Michela Orlandi 1 , Giulia C. Marchetti 3 , Valeria Castelli 4 , Giovanni Casazza 5 ,

Giorgio Costantino 4 and Gian Marco Podda 1*

1

Divisione di Medicina Generale II, ASST Santi Paolo e Carlo, Dipartimento di Scienze della Salute, Università degli Studi di

Milano, Milan, Italy, 2 Unità Operativa Complessa di Malattie Infettive, IRCCS Fondazione Ca’ Granda, Ospedale Maggiore

Policlinico, Milan, Italy, 3 Dipartimento di Malattie Infettive, ASST Santi Paolo e Carlo, Università degli Studi di Milano, Milan,

Italy, 4 U.O.C Pronto Soccorso e Medicina D’Urgenza, IRCCS Fondazione Ca’ Granda, Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico,

Università degli Studi di Milano, Milan, Italy, 5 Dipartimento di Scienze Biomediche e Cliniche “L. Sacco”, Università degli Studi

di Milano, Milan, Italy

Background: SARS-CoV-2-infected subjects have been proven contagious in the

symptomatic, pre-symptomatic and asymptomatic phase. The identification of these

patients is crucial in order to prevent virus circulation. No reliable data on the sensitivity

of nasopharyngeal swabs (NPS) are available because of the lack of a shared reference

standard to identify SARS-CoV-2 infected patients. The aim of our study was to collect

data on patients with a known diagnosis of COVID-19 who underwent serial testing to

assess NPS sensitivity.

Edited by: Methods: The study was a multi-center, observational, retrospective clinical study

Marc Jean Struelens,

Université libre de Bruxelles, Belgium with consecutive enrollment. We enrolled patients who met all of the following inclusion

Reviewed by: criteria: clinical recovery, documented SARS-CoV-2 infection (≥1 positive rRT-PCR result)

José Eduardo Levi, and ≥1 positive NPS among the first two follow-up swabs. A positive NPS not preceded

University of São Paulo, Brazil

John Hay,

by a negative nasopharyngeal swab collected 24–48 h earlier was considered a true

University at Buffalo, United States positive. A negative NPS followed by a positive NPS collected 24–48 h later was regarded

*Correspondence: as a false negative. The primary outcome was to define sensitivity of SARS-CoV-2

Gian Marco Podda detection with NPS.

gmpodda@gmail.com

Results: Three hundred and ninety three NPS were evaluated in 233 patients; the

Specialty section: sensitivity was 77% (95% CI, 73 to 81%). Sensitivity of the first follow-up NPS (n = 233)

This article was submitted to

Infectious Diseases - Surveillance,

was 79% (95% CI, 73 to 84%) with no significant variations over time. We found no

Prevention and Treatment, statistically significant differences in the sensitivity of the first follow-up NPS according to

a section of the journal

time since symptom onset, age, sex, number of comorbidities, and onset symptoms.

Frontiers in Public Health

Received: 10 August 2020 Conclusions: NPS utility in the diagnostic algorithm of COVID-19 should

Accepted: 31 December 2020 be reconsidered.

Published: 26 January 2021

Keywords: COVID-19, sensitivity, swab analysis, diagnosis, false negative (FN)

Citation:

Clerici B, Muscatello A, Bai F,

Pavanello D, Orlandi M, Marchetti GC,

Castelli V, Casazza G, Costantino G

BACKGROUND

and Podda GM (2021) Sensitivity of

SARS-CoV-2 Detection With Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is responsible of coronavirus

Nasopharyngeal Swabs. disease 2019 (COVID-19) (1). SARS-CoV-2-infected subjects have been proven contagious in

Front. Public Health 8:593491. the symptomatic, pre-symptomatic, and asymptomatic phase (2, 3). The identification of these

doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.593491 patients is crucial in order to prevent virus circulation. The ideal diagnostic test should be easily

Frontiers in Public Health | www.frontiersin.org 1 January 2021 | Volume 8 | Article 593491

Clerici et al. NPS Sensitivity in COVID-19

accessible, not invasive, with quick results and possibly cheap. Reverse Transcription Real-Time polymerase chain reaction is

Presently, clinicians rely on real time reverse transcription used to confirm the presence of COVID-19 by amplification

polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) tests performed on various of RdRp, E, and N genes. The cut-off Ct value of GeneFinder

biological specimens (4). Lower respiratory tract specimens COVID-19 Plus RealAmp Kit (ELITechGroup, Puteaux,

display the highest sensitivity (5), however their collection France) assay is 40 and the analytical sensitivity of the assay

is not feasible at large scale. The most accessible diagnostic is 1 copy/ µL.

test is rRT-PCR on upper respiratory tract samples, such as

nasopharyngeal swabs. Assuming a 100% specificity (6), no Definitions

reliable data on the sensitivity of nasopharyngeal swabs are A positive nasopharyngeal swab not preceded by a negative

available because of the lack of a shared reference standard to nasopharyngeal swab collected 24–48 h earlier was considered

identify SARS-CoV-2 infected patients. In fact, rRT-PCR-based a true positive (TP). A negative nasopharyngeal swab followed

tests imply known pre-analytical and analytical vulnerabilities by a positive nasopharyngeal swab collected 24–48 h later was

(7). Composite reference standards including clinical and regarded as a false negative (FN) (Figure 1).

radiological features have been used (8, 9), none of which

are however pathognomonic of COVID-19. RNA-positivity Outcomes

of biological specimens has been shown to outlast symptom The primary outcome was to define sensitivity of SARS-CoV-2

resolution (10). For these reasons we decided to collect data on detection with nasopharyngeal swabs. The secondary outcome

patients with a known diagnosis of COVID-19 who underwent was to evaluate nasopharyngeal swab sensitivity over time and

serial testing to assess nasopharyngeal swab sensitivity. the association between the sensitivity of the first nasopharyngeal

follow-up swab and the patient’s age, sex, comorbidities, and

onset symptoms.

METHODS

Study Design and Population Statistical Analysis

The study was a multi-center, observational, retrospective We estimated that the enrollment of 230 patients with

clinical study with consecutive enrollment. Participating centers documented SARS-CoV-2 infection would enable to estimate

included IRCCS Fondazione Ca’ Granda Ospedale Maggiore a 63% sensitivity with an acceptable precision, as quantified

Policlinico and ASST Santi Paolo e Carlo, Università degli Studi by the 95% CI (56 to 69%). Patient data have been recorded

di Milano, both based in Milan. All patients who sequentially on Microsoft Excel and analyzed with STATA 15 (StataCorp.

referred to the two participating centers for follow-up outpatient 2017. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. College Station, TX:

testing with nasopharyngeal swabs between 05/03/2020 and StataCorp LLC). Data were expressed as means ± standard

20/05/2020 were screened for enrollment. We enrolled patients deviation (SD) or medians with interquartile ranges (IQR)

who met all of the following inclusion criteria: clinical recovery as appropriate and sensitivities were compared using the

(apyrexia and no need for supplemental oxygen therapy for Chi-squared test.

3 consecutive days), documented SARS-CoV-2 infection (≥1

positive rRT-PCR result) and ≥1 positive nasopharyngeal swab RESULTS

among the first two follow-up swabs. We excluded patients

whose first two follow-up swabs delivered negative results Patients

(viral clearance). Seven hundred and six patients were screened for enrollment

after referral to the two participating centers for serial

Nasopharyngeal Swab Technique nasopharyngeal swab outpatient testing between 05/03/2020 and

All patients, once clinically recovered, were to undergo the 20/05/2020. Four hundred and seventy-three patients reached

first follow-up swab after 14 days since hospital discharge. In viral clearance after the first two follow-up nasopharyngeal swabs,

case of a positive result, the test was to be repeated after 7 and were therefore excluded. Two hundred and thirty-three

days; in case of a negative result, a second swab was performed patients met all inclusion criteria. All patients had ≥1 positive

24–48 h later. If this was also negative, patient isolation was rRT-PCR test collected at the time of diagnosis of COVID-19.

ended (11); if positive, the test was to be repeated after 7 All patients received the first follow-up swab once clinically

days. No other kind of respiratory specimen was collected for recovered, in most cases 14 days after hospital discharge. The

follow-up purposes. Nasopharyngeal swabs were performed, patients’ median age was 55.3 years (interquartile range, 43.4 to

stored and delivered to the testing laboratory as recommended 64.4), 39% of the patients were women, 74% were Caucasian, 15%

by the CDC and ECDC. Nasopharyngeal swabs were performed were Hispanic, 7% were Maghrebian, Middle Eastern or Arab,

following a standardized procedure (12). Briefly, GeneFinderTM and 3% were Asian. The ethnicity of 4 patients was unknown.

COVID-19 PLUS RealAmp Kit has been used for detection of Clinical data were available for 222 patients. Forty-nine patients

SARS-CoV-2 virus through reverse Transcription and Real- (22%) had no comorbidities, while 169 (78%) had ≥1. One

Time Polymerase Chain Reaction from RNA extracted from hundred and eighty-seven patients (84%) had pneumonia. The

nasopharyngeal swab (ELITe InGenius

R

system; ELITechGroup, most frequent onset symptoms were fever (96%), cough (80%),

Puteaux, France). The extraction volume was 200 µL. One-Step dyspnea (47%), fatigue (45%), ageusia (41%), and anosmia (34%).

Frontiers in Public Health | www.frontiersin.org 2 January 2021 | Volume 8 | Article 593491

Clerici et al. NPS Sensitivity in COVID-19

FIGURE 1 | Definition of true positive and false negative nasopharyngeal swabs. NP, nasopharyngeal.

All patients underwent ≥1 follow-up swab. The median number nasopharyngeal swab sensitivity in patients with known

of TP and FN nasopharyngeal swabs per patient was 1 (range, SARS-CoV-2 infection, based on the presence of symptoms

1 to 6). Of the 233 patients included in our analysis, 182 (78%) and of ≥1 positive rRT-PCR test, who underwent serial testing.

reached viral clearance. At the end of the study period data In our patient population sensitivity was 77% (95% CI, 73

collection was still ongoing for the remaining 51 (22%). The to 81%). Wang et al. evaluated SARS-CoV-2 detectability in

median time to viral clearance was 45.0 days (interquartile range, different biological specimens in a similar cohort of COVID-19

38.0 to 52.7) since symptom onset. patients and found a nasopharyngeal swab sensitivity of 63% (5);

however, this result was based on 8 samples. Kucirka et al. pooled

Sensitivity data from 7 relevant studies on both nasal and throat swabs,

The total number of TP and FN follow-up nasopharyngeal swabs and found that the probability of a false negative result was as

performed in our patient population was 393. Total TP swabs high as 21% even at the optimal testing window (3 days after

were 303; total FN swabs were 90. Of the 233 first follow-up symptom onset) (13). Two of the 7 analyzed studies included

swabs of our data set, 184 were TP and 49 were FN. Overall both rRT-PCR confirmed cases and probable cases, identified

nasopharyngeal swab sensitivity was 77% (95% CI, 73 to 81%). through clinical criteria alone.

Sensitivity of the first follow-up nasopharyngeal swabs (n = 233) Our sensitivity assessment might have been overestimated.

was 79% (95% CI, 73 to 84%) with no significant variations over Firstly, most of the patients included in our study had ≥1 positive

time (Figure 2). We found no statistically significant differences nasopharyngeal swab at time of diagnosis. Secondly, positive

in the sensitivity of the first follow-up nasopharyngeal swab follow-up nasopharyngeal swabs weren’t followed by a second

according to time since symptom onset, age, sex, number of swab 24–48 h later, unlike negative swabs; this might have led to

comorbidities, and onset symptoms. the underestimation of the number of FN nasopharyngeal swabs.

On the other hand, we didn’t perform further nasopharyngeal

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS swabs once viral clearance was reached; this, too, might have

contributed to the underestimation of total FN swabs.

Because of the unavailability of a shared reference standard Our study has some limitations. The fact that nasopharyngeal

for COVID-19 diagnosis there are no reliable data on swab sensitivity varies throughout disease course limits the

nasopharyngeal swab sensitivity. We decided to assess external validity of our findings. Although we might have

Frontiers in Public Health | www.frontiersin.org 3 January 2021 | Volume 8 | Article 593491

Clerici et al. NPS Sensitivity in COVID-19

FIGURE 2 | Nasopharyngeal swab sensitivity over time since symptom onset. Data were analyzed using the Chi-square test.

overestimated true nasopharyngeal swab sensitivity for the in clinical practice. We think that such a strategy should not

aforementioned reasons, sensitivity may be likely higher at the be encouraged since it is time-consuming, requires complex

beginning of the disease, when viral shedding is greater. We did organization and leads to facilities overcrowding and delay

not investigate the association between the antiviral treatment in treatment initiation. An alternative diagnostic strategy is

received during hospitalization and sensitivity of the first follow- urgently needed.

up swab. Lastly, as recommended by the WHO (11), we didn’t

perform further rRT-PCR-based tests after viral clearance was

reached. We cannot exclude that subsequent tests might have

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

shown the recurrence of positive nasopharyngeal swabs at least in The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be

some patients. Finally, it is possible that the sensitivity values of made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

the nasopharyngeal swabs are influenced by pre-analytical and/or

analytical variables; therefore, we cannot exclude that different

RT-PCR methods may be sources of variability in the sensitivity ETHICS STATEMENT

of the nasopharyngeal swabs.

In conclusion, in our large cohort of COVID-19 patients, The studies involving human participants were reviewed and

sensitivity of SARS-CoV-2 detection with rRT-PCR on approved by Comitato Etico Milano Area. All subjects signed

nasopharyngeal swabs was 77% (95% CI, 73 to 81%). For a written informed consent to personal data treatment, which

the purposes of our study, we assumed specificity to be 100%. allowed the anonymous use of clinical data for research purposes.

It is however safe to say that a positive nasopharyngeal swab

indicates SARS-CoV-2 infection. Conversely, with consideration AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

of the 77% sensitivity we found, a negative result alone

cannot rule out infection when this is suspected on clinical AM, FB, DP, MO, GM, and VC provided clinical data and

or epidemiological grounds. This has led to serial retesting revised the manuscript. GMP conceived the study and wrote

Frontiers in Public Health | www.frontiersin.org 4 January 2021 | Volume 8 | Article 593491

Clerici et al. NPS Sensitivity in COVID-19

the manuscript. BC wrote and edited the manuscript. GCo GCa performed the analysis. All authors contributed to the article

conceived and designed the study and revised the manuscript. and approved the submitted version.

REFERENCES 9. Zheng Z, Yao Z, Wu K, Zheng J. The diagnosis of pandemic coronavirus

pneumonia: A review of radiology examination and laboratory test. J Clin

1. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical Virol. (2020) 128. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104396

features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, 10. Wölfel R, Corman VM, Guggemos W, Seilmaier M, Zange S, Müller MA, et al.

China. Lancet. (2020) 395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20) Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID-2019. Nature.

30183-5 (2020) 581:7809. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2196-x

2. Oran DP, Topol EJ. Prevalence of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection: 11. Laboratory Testing of Human Suspected Cases of Novel Coronavirus (nCOV)

a narrative review. Ann Intern Med. (2020) 173:362–7. doi: 10.7326/ Infection. Interim Guidance 10 January 2020. World Health Organization.

M20-3012 Available online at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/330374/

3. He X, Lau EHY, Wu P, Deng X, Wang J, Hao X, et al. Temporal dynamics WHO-2019-nCoV-laboratory-2020.1-eng.pdf

in viral shedding and transmissibility of COVID-19. Nat Med. (2020) 26:5. 12. Collecting, Preserving and Shipping Specimens for the Diagnosis of Avian

doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0869-5 Influenza A(H5N1) Virus Infection. Guide for Field Operations. World Health

4. Cheng MP, Papenburg J, Desjardins M, Kanjilal S, Quach C, Libman Organization. (2006). Available online at: http://www.who.int/csr/resources/

M, et al. Diagnostic testing for severe acute respiratory syndrome-related publications/surveillance/WHO_CDS_EPR_ARO_2006_1/en/index.html.

coronavirus-2: a narrative review. Ann Intern Med. (2020) 172:726–34. 13. Kucirka LM, Lauer SA, Laeyendecker O, Boon D, Lessler J. Variation in

doi: 10.7326/M20-1301 false-negative rate of reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction–based

5. Wang W, Xu Y, Gao R, Lu R, Han K, Wu G, et al. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 tests by time since exposure. Ann Intern Med. (2020) 173:262–7.

SARS-CoV-2 in different types of clinical specimens. JAMA. (2020) 323:18. doi: 10.7326/m20-1495

doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3786

6. Corman VM, Landt O, Kaiser M, Molenkamp R, Meijer A, Chu DKW, Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that the research was conducted in the

et al. Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by real-time RT- absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a

PCR. Eurosurveillance. (2020) 25:3. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.3. potential conflict of interest.

2000045

7. Lippi G, Simundic AM, Plebani M. Potential preanalytical and Copyright © 2021 Clerici, Muscatello, Bai, Pavanello, Orlandi, Marchetti, Castelli,

analytical vulnerabilities in the laboratory diagnosis of coronavirus Casazza, Costantino and Podda. This is an open-access article distributed under

disease (2019). (COVID-19). Clin Chem Lab Med. March (2020). the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use,

doi: 10.1515/cclm-2020-0285 distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original

8. Ai T, Yang Z, Hou H, Zhan C, Chen C, Lv W, et al. Correlation of chest CT author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication

and RT-PCR testing in coronavirus disease 2019. (COVID-19) in China: a in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No

report of 1014 cases. Radiology. (2020) 2020:200642. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020 use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these

200642 terms.

Frontiers in Public Health | www.frontiersin.org 5 January 2021 | Volume 8 | Article 593491

You might also like

- Infection Control Competency QuizDocument7 pagesInfection Control Competency QuizLoo DrBrad100% (1)

- Chapter 3 - Microbiological Methods Analysis in FoodDocument68 pagesChapter 3 - Microbiological Methods Analysis in FoodPuvenez Tamalantan93% (29)

- Jurnal 2Document10 pagesJurnal 2GFORCE .ID.No ratings yet

- Lung Ultrasonography For The Diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 Pneumonia in The Emergency DepartmentDocument10 pagesLung Ultrasonography For The Diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 Pneumonia in The Emergency DepartmentFannyRivera27No ratings yet

- Ejifcc 2022 Vol 33 No 2Document139 pagesEjifcc 2022 Vol 33 No 2Georgiana Daniela DragomirNo ratings yet

- PIIS1198743X20306972Document4 pagesPIIS1198743X20306972KARLA PATRICIA DIAZ LOPEZNo ratings yet

- PEÑA2021 Performance EvaluationDocument5 pagesPEÑA2021 Performance EvaluationOliver Viera SeguraNo ratings yet

- 1.epidem I Kontrola SarsDocument7 pages1.epidem I Kontrola SarsadnanNo ratings yet

- Usefulness of High-Resolution Computed Tomography in Early Diagnosis of Patients With Suspected COVID-19Document7 pagesUsefulness of High-Resolution Computed Tomography in Early Diagnosis of Patients With Suspected COVID-19Israel Parra-OrtegaNo ratings yet

- Ijs DR 2212055Document4 pagesIjs DR 2212055Nicolas CastilloNo ratings yet

- 0 - Basti Andriyoko, DR., SPPK (K) - Diagnostik Molekuler SARS CoV2. PDS PatKLIn 20102020Document20 pages0 - Basti Andriyoko, DR., SPPK (K) - Diagnostik Molekuler SARS CoV2. PDS PatKLIn 20102020SuliarniNo ratings yet

- Reviews: Testing at Scale During The COVID-19 PandemicDocument12 pagesReviews: Testing at Scale During The COVID-19 PandemicAdrija SinghNo ratings yet

- Bulletin PDFDocument5 pagesBulletin PDFrishaNo ratings yet

- False-Negative Results of Initial RT-PCR Assays For COVID-19: A Systematic ReviewDocument19 pagesFalse-Negative Results of Initial RT-PCR Assays For COVID-19: A Systematic ReviewFre mobileNo ratings yet

- Development and Evaluation of A Rapid CRISPR-based Diagnostic For COVID-19Document12 pagesDevelopment and Evaluation of A Rapid CRISPR-based Diagnostic For COVID-19YunaNo ratings yet

- Validasi Rapid AntigenDocument6 pagesValidasi Rapid Antigengaki telitiNo ratings yet

- Ahead of Print: Establishment of Diagnostic Protocols For COVID-19 PatientsDocument6 pagesAhead of Print: Establishment of Diagnostic Protocols For COVID-19 PatientsSana AbbasNo ratings yet

- Id Now NP Rna VLDocument5 pagesId Now NP Rna VLluis achaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal MPIDocument4 pagesJurnal MPIMarini TaslimaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1198743X18308565 MainDocument6 pages1 s2.0 S1198743X18308565 MainYulia Niswatul FauziyahNo ratings yet

- Paper Grupo 5Document12 pagesPaper Grupo 5RobertoVeraNo ratings yet

- s41598 023 33824 6 PDFDocument7 pagess41598 023 33824 6 PDFscribdicinNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1472648320303187 MainDocument17 pages1 s2.0 S1472648320303187 Mainvenny2 tlm polbantenNo ratings yet

- Fimmu 11 595970Document11 pagesFimmu 11 595970Minh Anh VuNo ratings yet

- 10.1515 - DX 2020 0091Document3 pages10.1515 - DX 2020 0091trisna amijayaNo ratings yet

- Ifcc Interim Guidelines On Serological Testing of Antibodies Against Sars Cov 2Document8 pagesIfcc Interim Guidelines On Serological Testing of Antibodies Against Sars Cov 2laboratorio clinico HPASNo ratings yet

- Different Longitudinal Patterns of Nucleic Acid and Serology Testing Results Based On Disease Severity of COVID-19 PatientsDocument5 pagesDifferent Longitudinal Patterns of Nucleic Acid and Serology Testing Results Based On Disease Severity of COVID-19 PatientsagboxNo ratings yet

- Correspondence: Utility of Hyposmia and Hypogeusia For The Diagnosis of COVID-19Document2 pagesCorrespondence: Utility of Hyposmia and Hypogeusia For The Diagnosis of COVID-19Dhyo Asy-shidiq HasNo ratings yet

- Diagnostic Performance of A Sars-Cov-2 Igg/Igm Lateral Flow Immunochromatography Assay in Symptomatic Patients Presenting To The Emergency DepartmentDocument3 pagesDiagnostic Performance of A Sars-Cov-2 Igg/Igm Lateral Flow Immunochromatography Assay in Symptomatic Patients Presenting To The Emergency DepartmentWilmer UcedaNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Infectious Diseases: SciencedirectDocument8 pagesInternational Journal of Infectious Diseases: SciencedirectAntonio Barrios PerezNo ratings yet

- Predicting Infectious Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 From Diagnostic SamplesDocument4 pagesPredicting Infectious Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 From Diagnostic SamplesArum Rahmawatie VirgieNo ratings yet

- The Establishment of Reference Sequence For Sars Cov 2 and Variation AnalysisDocument8 pagesThe Establishment of Reference Sequence For Sars Cov 2 and Variation AnalysisYulaimy BatistaNo ratings yet

- Vaccination Strategy and Anti - Sars-Cov-2 S Titers in Healthcare Workers of The Int - Irccs "Fondazione Pascale" Cancer Center (Naples, Italy)Document10 pagesVaccination Strategy and Anti - Sars-Cov-2 S Titers in Healthcare Workers of The Int - Irccs "Fondazione Pascale" Cancer Center (Naples, Italy)Ioana SoraNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id3902468Document20 pagesSSRN Id3902468JaimeNo ratings yet

- Pruebas Diagnosticas Covid-19Document7 pagesPruebas Diagnosticas Covid-19JADIT YASIRA MENDOZA HERNANDEZNo ratings yet

- Development of Sars Cov 2 Viral Load Assay Using Standard Rna From in Vitro Transcript of Nucleocapsid Gene 624e8872921c0Document11 pagesDevelopment of Sars Cov 2 Viral Load Assay Using Standard Rna From in Vitro Transcript of Nucleocapsid Gene 624e8872921c0ERIE YUWITA SARINo ratings yet

- Predicting Infectious Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 From Diagnostic SamplesDocument4 pagesPredicting Infectious Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 From Diagnostic SamplesmikhaelyosiaNo ratings yet

- Quantifying The Risk of Sars Cov 2 Reinfection Over TimeDocument11 pagesQuantifying The Risk of Sars Cov 2 Reinfection Over TimeJimmy A. Camones ObregonNo ratings yet

- Covid-19 Breakthrough Infections in Vaccinated Health Care WorkersDocument11 pagesCovid-19 Breakthrough Infections in Vaccinated Health Care WorkerskajelchaNo ratings yet

- Covid19 Methods PDFDocument14 pagesCovid19 Methods PDFSulieman OmarNo ratings yet

- Mm695152a3 HDocument6 pagesMm695152a3 HKinja NinjaNo ratings yet

- Ijerph-18-11451 Meta Analysis StudyDocument14 pagesIjerph-18-11451 Meta Analysis StudySumit BediNo ratings yet

- Presence of Mismatches Between Diagnostic PCR Assays and Coronavirus Sars-Cov-2 GenomeDocument17 pagesPresence of Mismatches Between Diagnostic PCR Assays and Coronavirus Sars-Cov-2 GenomeYulaimy BatistaNo ratings yet

- Réponse Immun Covid19Document8 pagesRéponse Immun Covid19Tidiane SibyNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 20Document5 pagesJurnal 20Ahmad Fari Arief LopaNo ratings yet

- JCM 09 02870 v2Document9 pagesJCM 09 02870 v2Syaffa Sadida ZahraNo ratings yet

- Predicting Infectious Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 From Diagnostic SamplesDocument4 pagesPredicting Infectious Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 From Diagnostic SamplesmeNo ratings yet

- Supplement: Change in Saliva RT-PCR Sensitivity Over The Course of Sars-Cov-2 InfectionDocument3 pagesSupplement: Change in Saliva RT-PCR Sensitivity Over The Course of Sars-Cov-2 InfectionAdeline IntanNo ratings yet

- Use of Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence To P 2020 InternationalDocument8 pagesUse of Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence To P 2020 Internationaltshikutu bikengelaNo ratings yet

- Diagnostics For SARS-CoV-2 Infections Bhavesh D. Kevadiya1, Jatin Machhi1, Jonathan Herskovitz1,2, MaximDocument13 pagesDiagnostics For SARS-CoV-2 Infections Bhavesh D. Kevadiya1, Jatin Machhi1, Jonathan Herskovitz1,2, MaximDiego Paredes HuancaNo ratings yet

- Multicenter Evaluation of The Panbio™ COVID-19 Rapid Antigendetection Test For The Diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 InfectionDocument5 pagesMulticenter Evaluation of The Panbio™ COVID-19 Rapid Antigendetection Test For The Diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 InfectionamyNo ratings yet

- Referência 33Document10 pagesReferência 33jmaj jmajNo ratings yet

- Real-Time RT-PCR For COVID-19 Diagnosis: Challenges and ProspectsDocument3 pagesReal-Time RT-PCR For COVID-19 Diagnosis: Challenges and ProspectsAnthony StackNo ratings yet

- 001 Profiling Early Humoral Response To COVID-19 (IDSA 20) READDocument8 pages001 Profiling Early Humoral Response To COVID-19 (IDSA 20) READagboxNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0033350620301141 MainDocument3 pages1 s2.0 S0033350620301141 MainFedrik Monte Kristo LimbongNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Infectious DiseasesDocument3 pagesInternational Journal of Infectious DiseasesDetti FahmiasyariNo ratings yet

- New England Journal Medicine: The ofDocument10 pagesNew England Journal Medicine: The ofSuwandi ChangNo ratings yet

- Journal Pone 0262820Document11 pagesJournal Pone 0262820bioNo ratings yet

- COVID-19 Testing: A Reflection On Test Accuracy in The Real WorldDocument34 pagesCOVID-19 Testing: A Reflection On Test Accuracy in The Real Worldjoeboots78No ratings yet

- D'alessandro 2020Document5 pagesD'alessandro 2020Flip Flop ChartNo ratings yet

- Viruses 13 01116Document9 pagesViruses 13 01116SilviabeatoNo ratings yet

- Culture Media and MethodsDocument49 pagesCulture Media and Methodscj bariasNo ratings yet

- CDC Hiv Consumer Info Sheet Injecting Drugs 101Document2 pagesCDC Hiv Consumer Info Sheet Injecting Drugs 101Babaljeet DhaliwalNo ratings yet

- Oral Sex PamphletDocument2 pagesOral Sex PamphletsaNo ratings yet

- 1) StaphylococciDocument13 pages1) StaphylococciOmar K. FahmyNo ratings yet

- CBC COVID19 Product List 3 - 24 - 2020 PDFDocument11 pagesCBC COVID19 Product List 3 - 24 - 2020 PDFVina DevianaNo ratings yet

- Curing and Smoking Meats For Home Food PreservationDocument6 pagesCuring and Smoking Meats For Home Food PreservationJerin JamesNo ratings yet

- Intestinal Amebiasis: A Concerning Cause of Acute Gastroenteritis Among Hospitalized Lebanese ChildrenDocument9 pagesIntestinal Amebiasis: A Concerning Cause of Acute Gastroenteritis Among Hospitalized Lebanese ChildrenFrancisca OrenseNo ratings yet

- DAILY NATION Saturday July 25, 2020 PDFDocument16 pagesDAILY NATION Saturday July 25, 2020 PDFDixie CheeloNo ratings yet

- Hepatitis B: Journal ReviewDocument41 pagesHepatitis B: Journal Reviewagita kartika sariNo ratings yet

- Virologi & Ilmu Penyakit Viral Veteriner: Nurul HidayahDocument18 pagesVirologi & Ilmu Penyakit Viral Veteriner: Nurul HidayahTeoNo ratings yet

- Basic Medical Microbiology 1St Edition Patrick R Murray Full ChapterDocument67 pagesBasic Medical Microbiology 1St Edition Patrick R Murray Full Chapterjefferson.kleckner559100% (10)

- What's The Difference Between Covid-19 Rapid and PCR TestsDocument2 pagesWhat's The Difference Between Covid-19 Rapid and PCR TestsMedilife DigitalNo ratings yet

- Articulo BiologíaDocument6 pagesArticulo BiologíaJulieta Juárez OchoaNo ratings yet

- Microbiology and Parasitology Laboratory Activity No.1Document8 pagesMicrobiology and Parasitology Laboratory Activity No.1Eloisa BrailleNo ratings yet

- Ranikhet Disease of PoultryDocument22 pagesRanikhet Disease of PoultryNadineNo ratings yet

- OGUK - Flow Charts PDFDocument6 pagesOGUK - Flow Charts PDFvikrant911No ratings yet

- Autotherapy - Charles H. Duncan M. D.Document398 pagesAutotherapy - Charles H. Duncan M. D.Don FloresNo ratings yet

- Corona Virus Pandemic and Its Effects On Students788Document19 pagesCorona Virus Pandemic and Its Effects On Students788Suman MondalNo ratings yet

- Jurnal DBD PDFDocument9 pagesJurnal DBD PDFmarlinNo ratings yet

- H.I.V. Crossword PuzzleDocument3 pagesH.I.V. Crossword Puzzlejackie pascualNo ratings yet

- Avian Influenza (AI) : Synonyms DefinitionDocument16 pagesAvian Influenza (AI) : Synonyms DefinitionDr-Hassan Saeed100% (1)

- Highlight of Immune Pathogenic Response and Hematopathologic Effect in Sars-Cov, Mers-Cov, and Sars-Cov-2 InfectionDocument11 pagesHighlight of Immune Pathogenic Response and Hematopathologic Effect in Sars-Cov, Mers-Cov, and Sars-Cov-2 InfectionNandagopal PaneerselvamNo ratings yet

- Department of Genetics: Covid-19 RT PCRDocument1 pageDepartment of Genetics: Covid-19 RT PCRSahil AnsariNo ratings yet

- Foundations in Microbiology: The Gram-Positive Bacilli of Medical Importance TalaroDocument70 pagesFoundations in Microbiology: The Gram-Positive Bacilli of Medical Importance TalaroAgathaNo ratings yet

- Read The Text and Answer The QuestionsDocument3 pagesRead The Text and Answer The QuestionsSamara FernandesNo ratings yet

- Bio ProjectDocument10 pagesBio ProjectPADMESH DongreNo ratings yet

- Comprehensive Review of Infectious Diseases 1St Edition Andrej Spec Full Chapter PDFDocument69 pagesComprehensive Review of Infectious Diseases 1St Edition Andrej Spec Full Chapter PDFjeydeltaive100% (6)

- WWW Who Int News Room Fact Sheets Detail Immunization CoverageDocument6 pagesWWW Who Int News Room Fact Sheets Detail Immunization CoveragegrowlingtoyouNo ratings yet