Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Global Marketing Contemporary Theory Pra

Global Marketing Contemporary Theory Pra

Uploaded by

Bilal MustafaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Global Marketing Contemporary Theory Pra

Global Marketing Contemporary Theory Pra

Uploaded by

Bilal MustafaCopyright:

Available Formats

Confirming Pages

PART 1

Global Marketing

Environments

1 Understanding Global Markets and Marketing

2 Assessing the Global Marketing

Environment—The Global Economy

and Technology

3 Evaluating Cultural and Social Environments

4 Analyzing Political and Legal Environments

5 Integrating Global, Regional, and National

Markets

alo29279_ch01_001-025.indd 1 11/29/11 3:34 PM

Confirming Pages

1 CHAPTER

Understanding Global Markets

and Marketing

Companies must learn to operate as if the world were one large

market—ignoring superficial regional and national differences.

THEODORE LEVITT

learning objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

■ Understand how globalization impacts marketing strategy.

■ Define what is meant by “global marketing.”

■ Use the CAGE model to understand the differences between countries.

■ Determine how a firm is organized according to the EPRG framework.

■ Identify three approaches to developing a global marketing strategy.

■ Know why a global vision is important in order to develop a global marketing

strategy.

MARKETS ARE BECOMING GLOBAL

Traveling abroad, you encounter familiar brand names like Kentucky Fried Chicken,

Coca-Cola, and McDonald’s that you assumed are American owned (they are). Per-

haps you thought that some of these products tasted a bit different from the ones sold in

the United States, even though the products looked the same. If so, they were adapted

by changing the formula to conform to local tastes. If you were lucky enough to ride

in a Rolls-Royce, you probably assumed it was British (very British, but German-

owned). Maybe you drove a Land Rover, a British landmark; or a Volvo automobile,

Swedish-made; they were sold to Ford Motor Co. The fact that American products can

compete in local markets throughout the world and that European and Asian manu-

facturers can compete in America (who would have thought that Chinese and Indian-

made cars would sell in the United States?) is a consequence of the globalization of

markets and marketing.

Consider this. In Copenhagen, 18-year-old Hanna logs on to a Canadian website,

orders the latest CD recorded by Madonna, and pays for it in Kroner, using a Danish

credit card issued by her local bank. Her cousin Jacques, visiting from France, logs on

to a consumer electronics site, where he notices an advertisement for a new record-

ing gadget developed in Japan but not available in European stores. Jacques enters a

alo29279_ch01_001-025.indd 2 11/29/11 3:34 PM

Confirming Pages

Globalization: The World Is Becoming Smaller 3

BOX 1-1 COUNTRY IN FOCUS: INDIA

Your office phone rings. On the other end is an Delhi. Mr. Singh explains: “We have agreements

unfamiliar voice speaking in accented but very with a number of American CPA firms. We are

good English: “Good morning, sir, my name is linked to their databases, to which we have instant

accountant Bawa Singh and I would like to do your access. Using these databases, our accountants do

personal income tax return.” While you probably the tax returns. The American firms can then con-

will not receive such a phone call—and anyway you centrate on account servicing, customer relations,

have a local accountant doing your tax returns— and the more complicated returns, while we do the

nevertheless, it is very possible that your returns basics at a fraction of the cost.”

are actually filled out by someone like Bawa Singh. In a similar fashion, Indian offshore compa-

While you have never heard of him, he is one of nies do account billing for retail chains and banks

thousands of Indians employed in a string of off- and specialize in building websites and software

shore accounting firms located in Bangladore and development.

search engine and finds that the gadget is available for sale in Macau. He orders the

gadget from a Macau dealer, has it sent to his home address in Paris, pays for it in

euros, and receives a receipt for payment sent to his e-mail address. These transactions

represent global marketing that permits buyers and sellers the world over to meet and

do business online in virtually any language and currency, with ease, precision, secu-

rity, and reliability.

Another phenomenon of global markets is the growth of social networking web-

sites such as Facebook and Twitter. For example, Facebook’s international audience

totaled 34 million people at the beginning of 2008, and at the beginning of 2009 that

number had increased to 95 million. Many of Facebook’s markets are growing by dou-

ble digits every month. Are you connected? These websites have information about

their subscribers’ interests, hobbies and in some cases, consumption habits. In a sense,

Facebook’s analysts may know a lot about people and their friends in terms of what

they may be interested in! This information is very valuable to global advertisers who

choose to communicate via these websites.

All of these examples have occurred mainly as a result of globalization (see

Box 1-1). Globalization, a process of interaction and integration among people, com-

panies, and governments of many nations, is driven by international trade and invest-

ment and has resulted in what some call a global economy.

GLOBALIZATION: THE WORLD IS

BECOMING SMALLER

Businesses in every corner of the world, both large and small, must be aware of

the impact that the global economy is having on their performance. The Internet,

e-commerce, digital communication, and information transparency have led to an

increasingly mobile workforce, more informative customers, and rapidly changing

technologies and business models. As a result, many business organizations must

choose a global marketing strategy to enable them to win market share and capture

alo29279_ch01_001-025.indd 3 11/29/11 3:34 PM

Confirming Pages

4 chapt er 1 Understanding Global Markets and Marketing

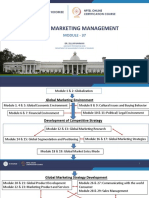

Global Marketing Assessment

Chapters 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6

Global

Marketing

Strategy

Chapters 7, 8, 9,

14, 15, 16

Global

Marketing

Mix

Chapters 10, 11,

12, 13

Figure 1-1 Global Marketing Book Organization

and retain current and prospective customers. Marketing is becoming more important

as organizations around the world strive to develop products and services that appeal

to their customers and aim to differentiate their offering in the increasingly crowded

global marketplace.

We believe that marketing strategy is the key to attaining competitive advantage in

the global marketplace. Therefore, the objective of this book is show how a successful

global marketing strategy can be developed and sustained.

The book is organized around three global marketing activities: assessment, strat-

egy, and the marketing mix. These three steps are shown in Figure 1-1. Before enter-

ing global markets, an assessment must be made of their economic, political, and

cultural environments. After making the assessment, the next step in the determination

of global marketing strategy concerns selecting markets and market entry strategies.

Finally, a marketing mix and product, promotion, distribution, and pricing strategies

are determined for each market. Figure 1-1 shows the sequence of chapters for each of

the three activities.

GLOBALIZATION AND GLOBAL MARKETING

Globalization is changing the competitive environment in which companies must

determine marketing strategy. The growing use of e-commerce, the spread of tech-

nological drivers such as the Internet and mobile phones, improved transporta-

tion facilities, and the removal of political and economic borders in many regions

of the world allows companies to focus not only on domestic markets but on

diverse global markets as well. As global markets become more interconnected and

dynamic over time, effective monitoring of the external environment and maxi-

mum use of company-specific resources will be imperative in order to gain com-

petitive advantage.

The global firm deals constantly with a paradox. On the one hand, global reach

implies general objectives and skills that transcend any particular country. Indeed, a

firm may enter a country because its vision and advanced skill set can make more of

alo29279_ch01_001-025.indd 4 11/29/11 3:34 PM

Confirming Pages

Globalization and Global Marketing 5

that country’s productive resources than local firms. On the other hand, global firms

are challenged by their comparative disadvantage in navigating many features of local

markets. Success means adapting general knowledge to the particular circumstances

of each country. The strategic challenge of the global firm entering a new country is

determining which business tactics and practices to import, which to evolve onsite,

and how to combine them within a working global enterprise.1

The technological advances spurred by globalization have enabled a significant

growth of worldwide outsourcing, as illustrated by the example in Box 1-1. An

example of how globalization affects international corporate culture and strategy

is the emergence of diversified global conglomerates (based in two or more coun-

tries). An example of a conglomerate/merger is Daimler-Benz’s (now Daimler) take-

over of Chrysler, intended to shore up both Daimler and Chrysler in their respective

markets.2

The DaimlerChrysler merger resulted in a large car manufacturing company,

ranked third in the world in terms of revenue, market capitalization, and earnings and

fifth in passenger cars and commercial vehicles sold. However, the merger actually

strengthened their Japanese rival, Toyota. The combined stock market value of both

companies in 2003 was half the sum of their separate valuations before they merged

in 1998.3

Why did the merger fail to reach its objectives? A major reason was the differ-

ence in organizational cultures of the two companies. Because American and German

managerial styles differed widely, a culture clash soon occurred that could not be

resolved even with the use of sensitivity workshops. Another problem was that the

Americans earned significantly higher salaries than their German counterparts, espe-

cially at managerial levels. The disparity in salary levels had made German employ-

ees envious of the Americans—not a good contributing factor to cooperation between

the two sides.

Marketing considerations also played a part. The brand images of both Chrysler

and Daimler-Benz automobiles were quite different. Chrysler’s “image was one of

American excess . . . its brand value lay in its assertiveness and risk-taking cowboy

aura . . . [While] Mercedes-Benz . . . exuded disciplined German engineering cou-

pled with uncompromising quality.”4 In 2007, Daimler sold an 80 percent stake in its

Chrysler brand to Cerberus Capital Management, a private equity investment firm.

However, the financial crisis took its toll when, in 2009, Chrysler filed for bankruptcy.

The bankruptcy allowed Chrysler to conclude an alliance with Italy’s Fiat, which took

a 20 percent stake in the company. The alliance could help Chrysler to survive with a

partner that makes small and midsize passenger cars.

The difficulty with such transatlantic mergers is that they not only transcend coun-

try and cultural boundaries but also necessitate new legal, financial, and managerial

considerations.5 Therefore, in designing strategies for firms operating in the global

age, not only are technological competencies required, but also geographical scope

and expertise for managing and marketing in foreign environments.

1. Calomiris, C. (30 August 2004). What does it mean to have a global vision? Columbia Business School.

2. DaimlerChrysler was ejected from membership in the American Automobile Manufacturers association because Chrysler was

no longer considered to be an “American” producer.

3. The New European order [Special report]. (2 September 2004). The Economist. Retrieved from www.economist.com/

node/3127264.

4. Finkelstein, S. (2002). The DaimlerChrysler merger. Tuck School of Business.

5. Lazer, W., & Shaw, E. (2000). Global marketing management: at the dawn of the new millennium. Journal of International

Marketing, 8(1), 65–77; Meyer, K. (2006). Global focusing: from domestic conglomerates to global specialists. Journal of Man-

agement Studies, 43(5), 1109–1144.

alo29279_ch01_001-025.indd 5 11/29/11 3:34 PM

Confirming Pages

6 chapt er 1 Understanding Global Markets and Marketing

Globalization: Opportunity or Threat?

Globalization—the trend toward a single integrated and interdependent world—is

driven by international trade and made possible largely by information technology.

Globalization may be understood by different perspectives. To the economist, glo-

balization refers to the emergence of global markets. On the other hand, sociologists

see globalization as the convergence of lifestyles and social values. To the political

scientist, globalization reduces national sovereignty. While aspects of globalization

have been around for more than a hundred years, one of the first to recognize it as such

was Marshall McLuhan. He coined the term “global village,” wherein people who are

physically separated by time and space are interconnected by electronic media. This

linkage, while having positive benefits, also carries responsibilities on a global level.6

The world turns into a “global village” as national borders disappear and time

and space distances contract. This contraction has come about because air, sea, and

communication costs have declined significantly during the twentieth century. Aver-

age ocean freight and port charges per ton fell from $95 in 1920 to $60 in 1930 and

fell again to $29 by 1990. Freight costs declined owing mainly to containerization

of cargo, which increased from about 20 percent of total cargo in 1980 to about

65 percent in 2000.

Communication costs declined owing to improvements in information technology.

For example, a three-minute phone call from New York to London cost $245 in 1930;

the same call cost only $3 in 1990. Making a bank transaction by telephone costs

about $0.55; making the same transaction in an ATM machine reduces the cost to

$0.45, and by the Internet to less than $0.10.

What are the opportunities driven by globalization? Trade liberalization means that

the demand for a country’s products is not limited to the home market, while invest-

ment, technology, and know-how move more freely across borders to both developed

and developing countries. Nevertheless, globalization has its detractors, as evidenced

by the some 40,000 protestors who interrupted the Third Ministerial Conference of the

World Trade Organization held in Seattle in late 1999. Much of the discontent con-

cerns the fact that the benefits of globalization have not been spread equally among

peoples and countries.

Yet most people around the world have positive attitudes toward globalization. The

majority of 38,000 people in 35 out of 44 developed and developing countries sur-

veyed by the Pew Global Attitudes Project7 believed that the growth in trade was very

good or somewhat good for their country. While it is not surprising that Americans

and Europeans hold positive attitudes toward globalization, it is surprising to find that

African and Asian respondents had equally if not stronger support for globalization as

compared to people in more developed countries.

The Global Marketing Approach

How to take advantage of the opportunities offered by technological breakthroughs

and the growth of both developed and emerging markets have become a critical

task for management, requiring a global approach to marketing strategy develop-

ment and implementation. A global approach requires the firm to focus its efforts

worldwide, rather than developing marketing strategies on a country-by-country

basis. It also requires the coordination and integration of production, marketing,

and other functional activities across countries. For many firms, a global marketing

6. McLuhan, M. (1964). Understanding media. New York: Mentor.

7. The Pew Global Attitudes Project. (2003). Views of a changing world. The Pew Research Center, Washington, D. C.

alo29279_ch01_001-025.indd 6 11/29/11 3:34 PM

Confirming Pages

The Cage Distance Framework 7

strategy requires a centralized operation to leverage scale advantages and optimize

resources and reduce costs.

Specifically, the objective of global marketing is to attain worldwide coordina-

tion, rationalization, and integration of all marketing activities including target market

selection, marketing-mix decisions, and organizational design and control mechanisms.8

The world-wide integration of marketing activities includes the development of global

products and brands and global communication and distribution strategies.

GLOBAL MARKETING AND GLOBAL MARKETS

Some proponents of global marketing contend that as markets are becoming homo-

geneous, country differences are less important to international marketing decisions.9

Others take an opposite view and claim that global markets are few, so that customizing

marketing strategies to the needs of local markets is still necessary.10 While the forma-

tion of regional, integrated markets such as the European Union, the North American

Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), and Mercosur (Southern Common Market)11 have

indeed brought us further toward a “borderless world,” there are still significant dif-

ferences in consumer motivations and preferences across markets. Therefore, there

is a fundamental difference between global marketing, the integration and control of

marketing activities on a global basis, and global markets, the idea that regional and/or

world markets are converging, allowing for a standardized marketing strategy. Imple-

menting a global strategy depends on the distance (or closeness) between regions and

countries. A framework for measuring distances is discussed below.

THE CAGE DISTANCE FRAMEWORK

According to the CAGE framework, distance between two or more countries can be

measured along four dimensions: Cultural, Administrative, Geographic, and Economic.12

Cultural differences include language, ethnicities, religion, values, and norms. Admin-

istrative distance measures differences in laws, political risk, and government structure.

Geographic distance includes country size, infrastructure, climate, and remoteness from

neighboring countries. Economic distance refers to differences in national income, costs

of doing business, prices, and availability of human and natural resources. These factors

affect not only differences between countries but also between industries.

Which of these factors is most important to international marketing decisions? It

depends. For example, two countries might be close to each other geographically, but

administrative distance might be large because of political hostility. In other cases,

cultural distance might be the dominant factor in creating distance between two coun-

tries, for example, in the case of food products. In other cases, economic distance

may be too great to overcome, such as low consumer income, unless products can

be tailored down and priced accordingly. The relevance of these differences will be

8. Douglas, S., & Craig, C. S. (1989, Fall). Evolution of global marketing strategy: scale, scope and synergy. Columbia Journal

of World Business, 47–59.

9. Sheth, J., & Parvatiyar, A. (2001). The antecedents and consequences of integrated global marketing. International Marketing

Review, 18(1), 16–34.

10. Quelch, J. A., & Hoff, E. J. (1986, May–June). Customizing global marketing. Harvard Business Review, 64, 59–68; Doug-

las, S. P., & Wind, Y. (1987, Winter). The myth of globalization. Columbia Journal of World Business, 19–29.

11. NAFTA members include the United States, Canada, and Mexico; Mercosur members are Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay,

Paraguay, and Venezuela. See Chapter 5 for a detailed discussion of these and other trade agreements.

12. Ghemawat, P. (2001, September). Distance still matters: the hard reality of global expansion. Harvard Business Review,

137–147.

alo29279_ch01_001-025.indd 7 11/29/11 3:34 PM

Confirming Pages

8 chapt er 1 Understanding Global Markets and Marketing

TABLE 1-1 CAGE Distance Dimensions

Number of Countries

Dimension Source Available

1. Cultural Hofstede (2001)

Power distance World Values Survey 68

Uncertainty avoidance (WVS; Inglehart, 2004)13 66

Individualism 69

Masculinity 69

2. Administrative CIA Factbook

Colonizer-colonized link La Porta et al. 199814 198

Common language

Legal system

3. Geographic CIA Factbook 196

Great circle distance

4. Economic World Development Indicators

Income (World Bank) 179

Inflation 157

Exports 165

Imports 165

Source: Adapted from: Berry, H., Guillén, M. F., & Zhou, N. (2010). An institutional approach to cross-national distance.

Journal of International Business Studies, 41(9), 1460–1480.

discussed below and elsewhere in this book. Suggested measures of CAGE distances

may be found in Table 1-1.1314

DOMESTIC AND GLOBAL MARKETING COMPARED

What distinguishes domestic from global marketing? There are three major differ-

ences between the two. Global marketing is characterized by:

1. Greater uncertainty in markets and environments.

Many global strategies do not succeed—either because they are never implemented

or because the business environment changes before the strategy can deliver its full

effect. In a symposium sponsored by the Wharton School, speakers identified two

major factors that determine the future economic environment. The first is “whether

external events that have the potential to affect economics are known and understood

or unknown and surprising” and the second is “whether corporations have the culture,

history and ability to be opportunistic in the face of rapidly changing conditions.”15

Moreover, successful firms understand the difference between taking active risks and

sitting by passively at risk.16

2. Global markets are more diverse and dynamic than domestic, internal markets.

On the downside, economic, legal, social, and cultural differences in global markets

make the task of the international marketing manager much more difficult than in a

domestic market. While there are similarities across markets, the differences may be

13. Inglehart, R. (2004). Human Beliefs and Values. Madrid: Siglo XXI.

14. La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1998). Law and finance. Journal of Political Economy,

106(6), 1113–1155.

15. Knowledge@Wharton. (5 December 2001). Retrieved from http://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article.cfm?>articleid=470.

16. Laudicina, P. (2005, March/April). Managing global risk to seize competitive advantage. Ivey Business Journal, 1–7.

alo29279_ch01_001-025.indd 8 11/29/11 3:34 PM

Confirming Pages

Domestic and Global Marketing Compared 9

greater. On the upside, the diversity of global markets exposes multinational com-

panies to multiple experiences that can be used to gain competitive advantage over

rivals that have not been exposed to the same learning experience. The transfer and

use of such knowledge throughout subsidiaries of a multinational company enables

the multinational firm to be a step ahead of rivals. Best practices, for example, can be

transferred and shared throughout the organization.

Emerging markets provide new opportunities for investment and marketing. For

example, the industrialization of China has been unparalleled in the twentieth and

twenty-first centuries. China has steadily increased its share of global industrial out-

put, including a gradual shift in the production of cheap and simple products to higher

quality ones. Other emerging markets have also shown significant growth. India had

become the world’s leading provider of IT and telecommunication services by the

end of the twentieth century. Emerging countries such as China, India, and Poland

not only provide opportunities, but also a double challenge for global firms; first, the

question of how to penetrate their home markets, and second, how to compete with

emerging market firms in global markets.

Demographic changes have also been significant. A decline in births and an increase

in aging populations has been the case in Europe and Japan. For example, birthrates

in the UK, Japan, and the United States have fallen over the last decade resulting in

zero population growth. Some see this as a positive development. Dr. John Guillebrand,

a retired professor of family planning in the UK, said that lower population growth

will result in less pressure on the planet’s resources and increase the output of green-

house gases. Overall population growth is increasing at a slightly declining rate

(see Figure 1-2), but is expected to increase to nine billion people by 2050. Yet low

birthrates means an aging population, increased pension payments, changes in work

patterns, and increased healthcare costs. These changes will pose a major challenge to

consumption-related sectors of the economy and, of course, the demand for specific

products and services aimed at an aging population.

World Population (Millions)

10000

Millions

5000

0

00

00

19 0

50

19 0

20 0

20 0

20 0

5

7

9

1

3

18

19

19

Year

World population

(Millions)

Figure 1-2 World Population Growth

Source: Data from Internet Geography. Retrieved from www.geography.learnontheinternet.co.uk.

alo29279_ch01_001-025.indd 9 11/29/11 3:34 PM

Confirming Pages

10 chapt er 1 Understanding Global Markets and Marketing

BOX 1-2 TECHNOLOGY IN FOCUS: HOME SHOPPING

Technology and Retail Jobs

“Is home shopping the beginning of an irreversible Most of us will still buy many items at the store, but

trend, with specific TV channels devoted to selling the new approach to shopping could save consum-

every type of merchandise or service? ers money because it will cut out the wholesalers,

While the current channels, with their zircons, distributors, and retailers. As a result, many people

skin creams, and hair-replacement products, may in retail sales could find themselves out of a job.

not look attractive to many consumers, technol- The number of people in delivery jobs who can

ogy and marketing support should eventually make provide speedy service, on the other hand, should

home shopping a sophisticated, viable alternative increase.”

to traditional retailing. Interactive high-definition

televisions will allow you to manipulate a product

onscreen, looking at it from different perspectives Source: Campbell, C. (1994). Where the jobs are: Career survival for Canadians

or zooming in to examine a detail. in the new global economy. Toronto: Macfarlane, Walter & Ross, 6–8.

Another dynamic aspect of global markets is the problem of global overcapacity in

so-called traditional industrial nations such as the United States, Japan, and Western

Europe as production increases in the emerging economies of Eastern Europe, China,

and India. Overproduction increases price competition and lowers profits.

3. Global markets are separated by greater geographical and psychological

distances.

Geographic or Spatial Distance

Spatial distances between domestic and global marketing have been reduced by the

substitution of IT media for face-to-face contact between buyers and sellers. Consum-

ers in one area of the world can be in instantaneous communication with sellers in

another part of the world through the Internet and videoconferencing. Transactions that

once took a long time to consummate can now be accomplished immediately over the

internet. Business meetings that require the presence of people scattered across regions

can now be held through videoconferencing, obviating the need for frequent travel by

managers. The billions of mobile and online Internet users worldwide are creating huge

opportunities for the development of electronic commerce and mobile commerce.

E-commerce revolutionizes the way consumers acquire information about products

and services offered globally. The Internet allows manufacturers the alternative to

shift from standardization to mass customization of products, as in the case of Dell

Computer Corporation, which can offer computers to order. Moreover, the Internet

overcomes global time and space barriers17 and removes many barriers to communica-

tion with customers and employees by eliminating the obstacles created by geography,

time zones, and location, thereby creating a “frictionless” business environment.18

17. Lazar, I. (16 October 2006). Counterpoint: demand for video conferencing seems weak. BCR Magazine. Retrieved from

www.collaborationloop.com/blogs/video-conferencing-market-demand-2.htm.

18. Colony, G., Deutsch, H., & Rhinelander, T. (1995, May). Network strategy service: CIO meets the Internet. The Forrester

Report, 12.

alo29279_ch01_001-025.indd 10 11/29/11 3:34 PM

Confirming Pages

Domestic and Global Marketing Compared 11

Middle East

3%

Africa Oceania /

6% Australia

1%

Latin America &

Caribbean Asia

10% 42%

North America

14%

Europe

24%

Figure 1-3 World Internet Users by Region

Source: Adapted from: Internet World Stats (www.internetworldstats.com/stats.htm). Basis: 1,966,514,816 Internet users on

June 30, 2010. Miniwatts Marketing Group.

Internet usage is pronounced in Asia, North America, and Europe, as shown in

Figure 1-3. Among developed countries, Iceland, Greenland, Norway, and Sweden

had penetration rates (usage as a percent of population) of over 90 percent of the popu-

lation by 2010. Note that these countries have sparse populations separated by land

mass or water, and therefore the use of the Internet and its communication facilities

is very important for human contact. Additional countries with high penetration rates

include Germany (79 percent of the population), Japan (78 percent) and the United

States (77 percent). Considering total Internet users (not as a percent of the popula-

tion), China has more total Internet users than the United States. The world total pen-

etration rate was 28.7 percent in 2010.19

There are constraining factors that may limit the use of telecommunication as a

substitute for travel. An earlier study of the use of telecommunications20 found that

recall was better without face-to-face contact, but that persuasion levels were higher

in face-to-face communication. The fact that the study took place in London may

have influenced the results, as a “lingering Puritan ethic still keeps many people from

accepting the idea that work can be successfully accomplished in a comfortable set-

ting.” A more recent study21 found that videoconferencing growth may be stalled

because people “don’t want to be seen.” Lazar (2006) comments that while videocon-

ferencing makes meetings more effective by forcing individuals to pay attention rather

than check e-mail or surf the web, its growth is constrained by a strong preference for

being heard rather than seen.

One of the most dramatic developments of the start of the new millennium was a

shift of advertising expenditure on traditional media to the Internet (see Table 1-2).

Advertising on television, radio, and print media is growing slowly, while that on the

Internet is increasing at higher rates. For example, the Internet’s share of advertising

expenditure was 19.2 percent of total UK advertising expenditure in 2009, an increase

19. Miniwatts Marketing Group. (2010).

20. Albertson, L. (1977). Telecommunications as a travel substitute—some psychological, organizational, and social aspects.

Journal of Communication, 27(2), 32–45.

21. Lazar, I. (16 October 2006). Counterpoint: demand for video conferencing seems weak. BCR Magazine. Retrieved from

www.collaborationloop.com/blogs/video-conferencing-market-demand-2.htm.

alo29279_ch01_001-025.indd 11 11/29/11 3:34 PM

Confirming Pages

12 chapt er 1 Understanding Global Markets and Marketing

TABLE 1-2 Online Advertising Spending in the United States (2001–2011)

2001 $7.1 (billion)

2002 $6

2003 $7.3

2004 $9.6

2005 $12.5

2006 $16.9

2007 $21.4

2008 $27.5

2009 $32.5

2010 $37.5

2011 $42

Source: Data from eMarketer. (2007, October). Retrieved from www.eMarketer.com.

of 3.7 percent over 2007 (15.5 percent). In 2002, the UK Internet share of mind (a limited

list of products or services that a consumer considers purchasing) was only 1.4 percent.

Growth of Internet advertising in the United States during the same period was also

significant, although less than that of England. In 2002, the United States Internet share

of mind was 2.5 percent, in 2006, 5.6 percent and in 2008, 12.9 percent.

Internet advertising reached double-digit figures in eight countries by the year 2008.

In the United States, Internet advertising increased from $7.1 billion in 2001 to $37.5

billion in 2010 (see Table 1-2). In addition to the UK and the United States, additional

countries include Sweden, Australia, Israel, Japan, Norway, South Korea, and Taiwan.

Psychic/Cultural Distance

The internationalization of the firm often means venturing into the unknown. Part of

this “unknown” relates to the culture of the host nation. When operating in foreign

environments, management must decide whether to adapt to the host culture, with its

language, lifestyle, behavioral standards (ethics, for example), and consumer prefer-

ences, or operate under the rules and assumptions of the home culture. Both the adher-

ence to host or home managerial styles has been used and can be explained by the

EPRG framework discussed below. Before looking at the EPRG framework, however,

a definition of psychic and cultural distances is necessary.

Cultural distance may be defined as some measure of the extent to which cultures

are similar or different. A number of frameworks for this purpose have been sug-

gested and will be discussed in Chapter 3. What is important to understand at this

point is that cultural distance is measured on the country level. It is a given and cannot

be controlled by management. Psychic distance, on the other hand, exists in the mind

of the individual;22 it is the perceptual distance between the home country culture and

the host country culture. Psychic distance occurs when management believes there

are significant differences between home and host cultures. Therefore, it is measured

on the individual level and not the country level, as is the case with cultural distance.

Both cultural and psychic distances affect how management formulates global

marketing strategy. Cultural differences influence consumer behavior and preferences

for various products. Culture-bound products such as food and home furnishings may

therefore have to be adapted to meet differences in consumer needs. Likewise, psychic

22. Sousa, C., & Bradley, F. (2006). Cultural distance and psychic distance: two peas in a pod? Journal of International Marketing,

14(1), 49–70.

alo29279_ch01_001-025.indd 12 11/29/11 3:34 PM

Confirming Pages

Domestic and Global Marketing Compared 13

distance may color managerial beliefs that the greater the distance between two or

more countries, the greater the differences in consumer preferences. While psychic

distance is perceptual, and may not accurately reflect actual differences, or lack of

them, it nevertheless influences managerial decision making. Psychic distance may

also affect a multinational firm’s organization during its internationalization process,

especially entry mode choices and the way it governs its operations abroad. This may

be explained by referring to the EPRG typology developed by Perlmutter (1969).23

The EPRG Framework

The EPRG framework is based on management’s worldview of the firm, which

determines the way in which its foreign market activities are organized. According to

the framework, there are four approaches or orientations by which a firm is managed

in foreign markets. These approaches or orientations also reflect different stages in the

internationalization of the firm, from solely a domestic player to a world competitor.

1. Ethnocentric orientation: In this stage, the focus is on the home market.

Firms holding this view believe that domestic strategies are superior to for-

eign ones, and therefore are applied in overseas operations as well. Overseas

operations are considered secondary to domestic operations. No systematic

marketing screening is made to search for foreign markets. An example of this

approach was the initial expansion of the American pharmaceutical company

Eli Lilly into overseas markets. It established offices in key markets, hired

local nationals to staff them, and maintained tight control by measuring each

country on bottom-line profitability. Operations of foreign subsidiaries were

limited to downstream activities required to support local sales, while market-

ing programs were developed at headquarters.24

2. Polycentric orientation: Unlike ethnocentric firms, those following this

approach use decentralized management, allowing affiliates to develop their

own marketing strategy. However, the mindset of management is focused

on the host country in the belief that because country markets are dissimilar,

marketing strategies must be adapted to the specific needs of each. There is

little room in this orientation for standardized marketing. Overseas markets are

screened individually. Each market operation functions independently without

any meaningful coordination or integration between them. Marketing activi-

ties are organized and carried out country by country, modifying the marketing

mix as necessary to meet the requirements of each market. An example of this

orientation was Ford’s marketing of the Escort. The UK version was differenti-

ated from the American model, not only because the steering apparatus had to

be shifted from the right to the left side, but also because the engine displace-

ment was greater in the United States, and styling was also different.

3. Regiocentric orientation: A particular region is viewed as comprising a

single market. Thus, regional trade areas such as the European Union and

Mercosur may be the focus of marketing activities. An attempt is made to

develop and implement marketing strategy for all countries comprising an

entire region. However, unlike the polycentric approach, emphasis is on coor-

dination of marketing in the region and standardization whenever possible.

23. Perlmutter, H. (1969, January/February). The tortuous evolution of the multinational corporation. Columbia Journal of

World Business, 4, 9–18.

24. Malnight, T. (1995). Globalization of an ethnocentric firm: an evolutionary perspective. Strategic Management Journal, 16,

119–141.

alo29279_ch01_001-025.indd 13 11/29/11 3:34 PM

Confirming Pages

14 chapt er 1 Understanding Global Markets and Marketing

An example of a company organized along regiocentric lines is Toyota. About

45 percent of its sales revenues are generated in Japan, with another 39 percent

originating in North America. Toyota’s success in North America stems from

its customer-driven new product development, aimed at this regional market.

4. Geocentric orientation: Firms adopting this approach view the world as a

potential market. In these markets, an attempt is made to implement global

marketing by integrating worldwide operations. Global products and brands

are produced in large volumes in order to achieve scale economies. A stan-

dardized product, brand, image, and positioning (as well as standardized

advertising whenever possible) with minimal adaptations are offered in all

markets. In both regiocentric and geocentric orientations, the ability to acquire

and share knowledge (such as best practices) among the various components

of the global, corporate network is maximized in order to attain and sustain

competitive advantage. For example, the Tide brand of laundry detergent

marketed in the United States by Procter & Gamble was first developed by its

German subsidiary and then introduced in Germany (under the brand name

Vizer) and later produced and marketed in several other European countries.

The European and later Latin American introduction of Vizer/Tide was made

possible by the experience and knowledge gained by German management

that was shared with other subsidiaries of P&G. Table 1-3 summarizes product

strategy of a multinational firm under each of the above conditions.

Developing Global Marketing Strategies

In order for firms to successfully compete globally, they must achieve significant com-

petitive advantage over their rivals. To do so, a firm must develop a global marketing

strategy. There are three approaches to global marketing strategy: Standardization,

Configuration/Coordination and Integration of the Firm’s Value Chain.

The Standardization versus

Localization–Adaptation School

If we could put together a seminar attended by marketing managers of multinational

corporations, one of the main topics for discussion would be whether a standardized

marketing approach to markets is preferable to a localized (differentiated) approach. A

truly globalized marketing strategy would aim to standardize elements of the market-

ing mix in all markets served by the company. In reality, it is rare to find a completely

standardized marketing mix. Some companies may be able to standardize products but

have to localize advertising campaigns. Others may have to localize product strategy

but are able to standardize advertising. The Dell Computer Company, for example,

standardizes its direct sales strategy in all its markets but localizes advertising strategy.

TABLE 1-3 EPRG and Global Product Strategy

Orientation Product Strategy

Ethnocentric Product development determined by needs of home country customers.

Polycentric Local product development based on local needs.

Regiocentric Standardized within region, but not across regions.

Geocentric Global product with local variations.

Source: Thomson, A. Jr. & Strickland, A. Strategic Management, 13e © 2003 The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.

alo29279_ch01_001-025.indd 14 11/29/11 3:34 PM

Confirming Pages

Domestic and Global Marketing Compared 15

High need

Direct marketing

Website

Advertising

Product strategy

Brand identity

Finance

Low need

Figure 1-4 The Need for Localization Varies by Business Function

Source: Adapted from: ITSMA Viewpoint, June 2005, p. 3.

On the other hand, Nestlé localizes some of its products but attempts to standardize

advertising campaigns as much as possible.

Figure 1-4 illustrates that the degree of localization needed depends on the business

function performed. Most marketing functions need some sort of adaptation across

markets, whereas such functions as finance need very little adjustment. Brand identity

is a function that most companies want to standardize, in order to maintain a uniform

image worldwide.

When is a standardized strategy preferable? There are several reasons why manu-

facturers and service providers prefer standardized marketing strategies on a global

basis. These include gaining economies of scale in production and marketing, lowering

costs—especially high R&D and development costs —and easing pressures exerted by

global customers for the supply of uniform products. In industries that have high devel-

opment and set-up costs and rapid technological obsolescence, it is to their advantage

to develop standardized products that can be rapidly introduced in a large number of

markets in order to recoup investment. Likewise, in industries where learning curve

advantages are important, standardization can lower costs. Global customers can also

pressure their suppliers to offer uniform products to their various manufacturing facili-

ties that are located in a number of countries. For example, global suppliers of paint

products to global car manufacturers must provide a standardized product from their dif-

ferent plant locations to ensure that all cars will have the same exterior finish. Table 1-4

TABLE 1-4 Companies Using Standardized Marketing Strategies

Strategy Company

Product Design Ford (Escort), Nokia Mobile Phones, Gillette (razors),

Kodak (cameras)

Brand Name Heineken, Coca-Cola, Reebok, Nivea, Ikea

Product Positioning Colgate (toothpaste)

Packaging Gillette (razors)

Advertising McDonald’s, Kodak (cameras)

Sales Promotion Thane International (exercise equipment)

Distribution Mary Kay (cosmetics), Ikea

alo29279_ch01_001-025.indd 15 11/29/11 3:34 PM

Confirming Pages

16 chapt er 1 Understanding Global Markets and Marketing

shows selected companies that use standardized marketing strategies. Some may

design products globally but localize distribution (e.g., Gillette razors). Others may

have two or more of the listed standardized strategies (e.g., Kodak).

On the other hand, there are factors working against the ability of firms to standard-

ize marketing strategies: different tastes and customer preferences and performance

requirements and standards across countries inhibit the ability to standardize. When

Nestlé introduced its coffee products into China, it created a blend adapted to the

particular tastes of Chinese consumers. Nestlé’s wafer bar brand Kit Kat generates

roughly $1 billion in sales worldwide. This product is adapted in many markets. For

example, in Russia, its size is smaller than in Western countries and the chocolate is

coarser, while in Japan the flavor is strawberry. Kenichi Ohmae25 writes that “When it

comes to product strategy, managing in a borderless economy doesn’t mean managing

by averages. It doesn’t mean that all tastes run together into one amorphous mass of

universal appeal. And it doesn’t mean that the appeal of operating globally removes

the obligation to mobilize products. The lure of a universal product is a false allure.”

However, in a revised edition,26 Ohmae observes that “young people of the advanced

countries are becoming increasingly nationality-less and more like ‘Californians’ all

over the Triad countries—the United States, Europe, and Japan. . . .” The inference

here is that this particular market segment of young people in developed countries

may be targets for standardized products. We can think of some: Levi’s jeans, iPods,

and Timberland shoes. These are some examples of products that are standardized

across borders.

Even when products are standardized, it may not be possible to standardize other

elements of the marketing mix. A case in point was a Nescafé commercial aired in

Chile. The commercial showed a house by a lake. Inside, the father tries to wake

his son to go fishing, but the son prefers to stay in bed. Soon, the son wakes up and

prepares a cup of coffee. Reinvigorated, he brings a cup of coffee to his father who is

sitting by the lake, disappointed by his son’s decision not to join him. However, father

and son are reunited over a cup of coffee. The message is that coffee helped the rela-

tionship of both. However, the same commercial aired, for example, in Paris, might

simply be viewed as an environmental statement. While coffee tastes may conceivably

be the same in both countries, perception of the same advertising appeal might be

quite different.

Another example of different perceptions of the same advertising message occurred

when a television commercial produced for North American audiences was aired in

several Latin America countries. The idea behind the message was to encourage the

sale of additional telephone sets in two-story homes. A phone call for the husband was

received by his wife who was working in the kitchen. The husband was on the second

floor, without a telephone installation. The housewife shouted to her husband to come

down right away and answer the phone. The ad was perceived negatively because the

wife gave an order to her husband in a very masculine country, and she seemed to be

impatient in a society where orientation to time and urgency were much different than

in North America.

Levitt and the Globalization of Marketing

The late Theodore Levitt (1925–2006), longtime professor at the Harvard Business

School, was one of the first marketers to envisage the possibility of a global market-

ing strategy. His vision contemplated the convergence (the tendency for everything to

25. Ohmae, K. (1990). The borderless world. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, Inc.

26. (1999). The borderless world (Rev. ed.). New York: HarperCollins Publishers, Inc.

alo29279_ch01_001-025.indd 16 11/29/11 3:34 PM

Confirming Pages

Domestic and Global Marketing Compared 17

become more like everything else) of consumer demand worldwide.27 Levitt believed

that accustomed differences in national or regional preferences were a thing of the

past. If marketers could provide high-quality products at reasonable, low prices, they

would appeal to consumers in different countries. The ability of manufacturers to do

so, however, depends on three factors: (1) substantial economies of scale, (2) consumer

sensitivity to price and quality above all other considerations, and (3) homogenization

of consumer desires and tastes across national boundaries. Levitt’s assumptions have

been questioned, especially the second and third above. There are significant differ-

ences between national markets that require adaptation and customization in, if not

all of marketing programs, then at least in some parts, such as product and promo-

tional strategies. Whether consumers everywhere will prefer less expensive, standard-

ized products over differentiated ones (remember Ford’s Model T—“You can choose

any color as long as it’s black”?) has been largely discounted. Levitt himself toned

down his vision and realized that companies had to balance persistent national cul-

tural patterns with the general trend toward the embrace of global brands. Thus, he

acknowledged tactics like McDonald’s supplementing its standard menus with local

fare like vegan meals in India, Coca-Cola varying the sugar content of its soft drinks,

and Nestlé developing products to meet local tastes if a global brand is not acceptable.

Standardization versus Mass Customization

Pine’s (1993) theory28 of “mass customization” challenges the globalization (standard-

ization) of marketing approach. Mass customization has been defined as “a strategy

that creates value by some form of company-customer interaction at the fabrication/

assembly stage of the operations level to create customized products with production

cost and monetary price similar to those of mass-produced products.”29 Pine asserts

that many consumers are unwilling to purchase standardized products even though

they are sold for lower prices. On the contrary, many people are willing to pay more

for customized products that meet specific desires. In effect, the concept of customiza-

tion views each consumer as a segment. Proponents of such an approach maintain that

it is possible owing to the achievement of economies of scale through computer aided

manufacturing (CAM).

Some examples of successful customization of consumer goods and services include:

■ Dell’s famous “build-to-order” model facilitated its rise to dominance in the

PC direct-purchase industry.

■ The Architectural Skylight Company is a firm in Maine that uses CAD to auto-

mate the production of windows to architects’ specifications.

■ Companies throughout the tourism industry have been offering package holi-

day alternatives through mass customization.

Additional examples of mass customization are operational today, such as software-

based products that make it possible to add and/or change functionalities of a core

product or to build fully custom enclosures from scratch. This degree of mass custom-

ization has only seen limited adoption, however. If an enterprise’s marketing depart-

ment offers individual products (atomic market fragmentation) it doesn’t often mean

that a product is produced individually, but rather that similar variants of the same

mass produced item are available.

27. Levitt, T. (1983, May/June). The globalization of markets. Harvard Business Review, 61, 92–102.

28. Pine, B. J. (1993). Mass customization: the new frontier in business competition. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School.

29. Kaplan, A., & Haenlein, M. (2006). Toward a parsimonious definition of traditional and electronic mass customization.

Journal of Product Innovation Management, 23(2), 168–182.

alo29279_ch01_001-025.indd 17 11/29/11 3:34 PM

Confirming Pages

18 chapt er 1 Understanding Global Markets and Marketing

While theoretically feasible, the customization approach has not received much

support in the marketing literature. Some of its drawbacks include longer wait-

ing times for customized products, longer searching times for retail outlets, and of

course higher prices. Many industries have found that lengthy supply chains and the

economics of configurability do not allow them to economically offer mass custom-

ization. Some of the early businesses attempting mass customization (e.g., in bicycle

production) went out of business. Supporters of the mass customization trend gave

Cannondale as the exemplar of the new model. For instance, Wind and Rangaswany30

(2000) cited the Cannondale bicycle company’s ability to mass customize. Although

the company’s subsequent bankruptcy in 2003 was blamed on other causes (including

a failed attempt to enter the motor sports market), the mass customization “revolution”

certainly failed to save it, and it was dropped as a role model by business gurus. The

company later became part of Dorel industries, a multinational leisure and recreational

products (Schwinn and Cannondale bicycles) manufacturer headquartered in Canada

(www.dorel.com).

In spite of these failures, the “customized consumer” does exist as a separate, niche

segment alongside those willing to accept standardized products.31

Managing the Firm’s Value Chain

A key tool for developing and sustaining competitive advantage is configuring and

coordinating the firm’s value chain. Briefly, a value chain is the sequence of activities

required to make a product or provide a service.32 A firm’s survival depends upon its

ability to create value which is demanded by customers. An example of a firm’s value

chain is shown in Table 1-5.

The value chain concept developed by Michael Porter33 is based on the premise

that organizations consist of activities that when linked together provide value to both

the firm and to the final consumer. These activities are categorized as primary, such

as production and marketing, and support activities that provide the facilities that con-

tribute to the effectiveness and efficiency of the firm, such as research and develop-

ment and human resource management. Primary value chain activities are:

■ Inbound Logistics: receiving and warehousing of raw materials and distribu-

tion to manufacturing

■ Operations: transforming inputs into finished products and services

■ Marketing and Sales: identification and satisfaction of customer needs

■ Service: after sales support

Secondary value chain activities support the primary activities. These include:

■ Firm Infrastructure: organization and control mechanisms, company culture

■ Human Resource Management: recruiting, hiring, training, development, and

compensation of employees

■ Technology: development of technology to support value-creating activities

■ Procurement: purchasing material, supplies, and equipment inputs

30. Wind, J., & Rangaswamy, A. (2000). Customerization: the next revolution in mass customization. eBusiness Research Center

Working Paper 06-1999. Penn State School of Information Sciences and Technology.

31. Bardacki, A., & Whitelock, J. (2004). How “ready” are customers for mass customization? An exploratory investigation.

European Journal of Marketing, 38(11/12), 1396–1416.

32. Schmitz, H. (2005). Value chain analysis for policy-makers and practitioners. Geneva: International Labour Office.

33. Porter, M. (1985). Competitive advantage: creating and sustaining superior performance. New York: The Free Press.

alo29279_ch01_001-025.indd 18 11/29/11 3:34 PM

Confirming Pages

Domestic and Global Marketing Compared 19

TABLE 1-5 Value Chain Framework

Primary Activities Support Activities

Inbound Logistics Infrastructure

Operations Human Resource Management

Marketing and Sales Technology Development

Service Procurement

Source: Adapted from: Porter, M. (1985). Competitive advantage: creating and sustaining superior

performance. New York: The Free Press.

Each link in the chain provides value, with some providing more value than oth-

ers. The end result is “margin,” or the difference between the total value (the price

the consumer is willing to pay) and the cost of performing all the activities in the

chain. Margin can be improved by either reducing activity costs or by increasing their

value. It should be emphasized that not all firms perform all activities in a value chain;

some are farmed out, or outsourced to other firms that can provide them more effec-

tively and/or more efficiently; e.g., at lower cost. This is what Porter34 termed a “value

system,” a set of inter-linked firms that perform all the functions in a given value

chain, say for the production of computers. An example of such a chain-value sys-

tem is the design of notebook computers in Taiwan and their assembly in China for

most of the well-known brands sold today. Marketing strategy is planned at company

headquarters. In this example, the design, production, and marketing of the comput-

ers is executed in at least three countries. As a result, the coordination of these value

activities has to be controlled by a strong governance structure because of the risk of

supplier failure to maintain quality and to deliver on schedule. In these cases, there

is usually a “lead firm” that takes control, often the owner of the brand, such as Dell

or Hewlett Packard (HP). Control and coordination are exercised by the lead firm in

defining the products to be produced by suppliers and by providing key resources

needed in the chain. In most cases value chains are producer-driven, as in the case

of notebook computer manufacturers. However, there are buyer-driven chains, which

include industries where large retailers and trading companies are lead firms, such as

the British-headquartered chain Marks & Spencer.

Global Value Chain Configuration

In a global marketing system, there is a growing spatial dispersion of activities that

comprise a value chain. This is one of the major distinctions between a domestic and

international chain. According to Michael Porter, these distinctions revolve around

two dimensions: configuration and coordination of the activities in the chain. Con-

figuration refers to where and how the activities will be located, either concentrated

in one country or dispersed in many countries. Coordination refers to the governance

of the activities, how they are linked together throughout a chain which is dispersed

geographically in different countries. Therefore, configuration and coordination are

the major tools by which a value chain is managed.

Table 1-6 shows two primary activities and one support activity that are configured

and coordinated globally by a multinational manufacturer of high-quality shoes with

corporate headquarters located in Denmark.35 Shoe components (uppers, soles, etc.)

34. Porter, M. (1990). The competitive advantage of nations. New York: The Free Press.

35. Er, M., & MacCarthy, B. (n.d.). Configuration of international supply networks and their operational implications:

Evidences from manufacturing companies in Indonesia. University of Nottingham.

alo29279_ch01_001-025.indd 19 11/29/11 3:34 PM

Confirming Pages

20 chapt er 1 Understanding Global Markets and Marketing

TABLE 1-6 Global Value Chain Configuration

Primary Activities Support Activities

Inbound Logistics Infrastructure

Production in Indonesia, Denmark, Portugal,

Slovakia, and Thailand

Operations Human Resource Management

Marketing and Sales Technology Development

Marketing plans developed in Denmark Product development in Denmark

& Indonesia

Service Procurement

Source: Adapted from: Porter, M. (1985). Competitive advantage: creating and sustaining superior performance.

New York: The Free Press.

are manufactured in five locations: Indonesia, Denmark, Portugal, Slovakia, and

Thailand. However, nearly 50 percent of the upper shoe is produced in Indonesia, and

these parts are then shipped to other facilities where soles are added. Product develop-

ment and marketing strategy, including sales forecasting and production quotas for the

company’s subsidiaries and licensees, is determined by headquarters management in

Denmark. Of course, there are many other activities, such as procurement, distribu-

tion, and services that are configured globally as well, which illustrates the complexity

of a global value chain. Indeed, the competitive advantage of a firm may well depend

on its effectiveness in managing the set of value-adding activities across borders.

Integrating the Firm’s Competitive Strategy

Other marketing scholars argue that the key to competitive advantage and global mar-

keting success is participation in major world markets and integration of competitive

strategies across these markets. Central to this line of reasoning are two tactics: cross-

subsidization of operations in one market by shifting resources (capital, managerial

talent) to other markets and responding to competitive pressures in one market (e.g., a

firm’s home market) by counterattacking competitors in their home market or in other

key markets. By entering a rival’s home market, a global competitor may motivate the

rival to deploy resources in order to defend its home. By allocating resources in defense

of the home market, the rival will have fewer resources to compete in other markets.

Global Competition

Global players can choose where to compete and invest the most resources against

rivals—in their home market, in the competitor’s home market, or in third markets

where both compete. For example, in 1998, Michelin, the French tire manufacturer,

was planning to enter the United States, the home market of Goodyear Tire. At the

time, Michelin had an 18 percent world share of tire sales, compared to 17 percent

for Goodyear. In order to strengthen its European position and compete against Michelin,

Goodyear negotiated a joint venture (JV) with Somitomo, a Japanese manufacturer that

had a 5.5 percent world market share. The JV gave Goodyear control over Somitomo’s

European operations, including more distribution channels. The result for Goodyear

was increased market share in Europe that stalled, for a time, Michelin’s challenge to its

home market in the United States. Michelin had to concentrate resources in Europe in

order to thwart Goodyear’s challenge to its home market.

alo29279_ch01_001-025.indd 20 11/29/11 3:34 PM

Confirming Pages

A Global Marketing Management Framework 21

Another case of global competition is called cross-subsidization. Cross-subsi-

dization is applicable when firms can benefit from sharing costs and/or revenues.36

A global firm can shift resources from more profitable subsidiaries to less profitable

ones. Cost sharing among subsidiaries to support R&D for product development is

another possibility. Knowledge sharing among subsidiaries or affiliates is another area

that can create synergy for firms operating in global industries. A lack of knowledge

sharing resulted in huge losses for Caterpillar—the world’s largest tractor manufac-

turer since the 1960s—during 1982–1984 and 1991–1992, when its Japanese rival

Komatsu gained market share in both European and North American markets. How-

ever, by 1999, Caterpillar was profitable again, owing mainly to a strengthened global

marketing and sales network and strict financial controls.

A GLOBAL MARKETING MANAGEMENT

FRAMEWORK

A number of researchers37 argue that global marketing strategy influences a firm’s

global marketing performance. Global marketing strategy, in turn, is mediated by

external market drivers and internal drivers, which are in effect internal character-

istics of the firm. Studies in industrial economics have shown that a firm’s external

environment influences its strategy and hence its performance.38 Those firms that

are able to “read” and understand these drivers are more likely to perform well. It is

imperative for firms operating globally to respond quickly and effectively to changes

in the economy, competition, consumer requirements, and technology. The boycott of

French wine in the United States briefly during 2003, owing to France’s opposition

to the invasion of American forces in Iraq, and the boycott against Danish products

in Middle Eastern countries stemming from the Danish Mohammed cartoon crisis in

2005, demonstrate the importance of keeping an ear open to such changes. Likewise,

a firm’s success will depend upon the extent to which it develops internal capabilities

and resources to implement its strategy. Needed are managers who both recognize the

importance of internationalizing the firm and who succeed in implementing a global

marketing strategy.

As outlined at the beginning of this chapter, a global strategy is an organization-wide

plan designed to enable the firm to develop a strong global presence, especially in terms

of marketing and production. The elements of a global marketing strategy and its inter-

nal and external drivers are shown in Figure 1-5. Internal drivers are those that ema-

nate from within the firm, and are thus controllable by management, such as a global

vision and firm capabilities and the financing and international experience of execu-

tives. External drivers, on the other hand, are not controllable by the firm, but impact its

ability to determine and execute a global strategy. Among these drivers are the global

economy, culture, political-legal systems, and technology. All of these drivers will be

discussed in the chapters that follow. We begin a discussion of the Global Marketing

framework with attention to the dependent variable: Global Marketing Performance.

36. Ghoshal, S. (1987). Global strategy: an organizing framework, Strategic Management Journal, 8, 425–440.

37. Porter, M. (1986, Winter). Changing patterns of international competition. California Management Review, 28, 9–40;

Ohmae, K. (1989, May/June). Managing in a borderless world. Harvard Business Review, 67, 152–161; Yip, G. (1995). Total

global strategy: managing for worldwide competitive advantage. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; Zou, S., & Cavusgil, T.

(2002, October). The GMS: a broad conceptualization of global marketing strategy and its effect on firm performance. Journal

of Marketing, 66, 40–56; Townsend, J., Yeniyurt, S., Deligonul, S., & Cavusgil, S. (2004, March). Exploring the marketing pro-

gram antecedents of performance in the global company. Unpublished working paper.

38. Porter, M. (1980). Competitive strategy. New York: The Free Press.

alo29279_ch01_001-025.indd 21 11/29/11 3:34 PM

Confirming Pages

22 chapt er 1 Understanding Global Markets and Marketing

Internal Drivers

Global vision

Market orientation

Organizational

Capability Global Marketing

Finances Strategy

International Competitive positioning

Experience Country grouping

Market entry

Country/Market Global

Segmentation Marketing

Marketing mix Performance

Logistics

External Drivers Organizational design

Global economy Coordination of value-

Cultural diversity Added activities

Legal/Political Ethics and social

Systems Responsibility

Market structures

Competition

Country-of-origin

Effect

Technology

Figure 1-5 A Framework for Global Marketing Strategy

Global Marketing Performance

Ambler and Xiucun39 (2003) suggest that marketing effectiveness or performance can

be measured within four dimensions of business activity, as shown in Table 1-7. While

financial outcomes measure overall firm performance, market and consumer-oriented

metrics are better indicators of marketing success. If global marketing strategy takes

into consideration external globalizing drivers, there should be a significant impact on

the firm’s global performance.40 Moreover, there is evidence of a positive relationship

between the development of customer knowledge, new product advantage, and market

performance.41

As shown in Table 1-7, innovativeness also impacts marketing performance. Booz

Allen Hamilton consulting found that firms having the highest rates of R&D spend-

ing as a percentage of sales are more likely than other companies in their industries to

achieve superior gross margins.42 Higher gross margins allow more to be spent on mar-

keting programs, including research and development. Among the world’s top R&D

spenders (R&D/sales) are firms in the health and electronic industries. These include

39. Ambler, T., & Xiucun, W. (2003). Measures of marketing success: a comparison between China and the United Kingdom.

Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 20, 267–281.

40. Zou, S., & Cavusgil, T. (2002, October). The GMS: a broad conceptualization of global marketing strategy and its effect on

firm performance. Journal of Marketing, 66, 40–56.

41. Li, T., & Cavusgil, S. (2000). Decomposing the effects of market knowledge competence in new product export:

a dimensionality analysis. European Journal of Marketing, 34(1/2), 57–79.

42. Jaruzelski, B., Dehoff, K., & Bordia, R. (2006). Smart spenders: the global innovation. Special Report. Booz Allen Hamilton.

alo29279_ch01_001-025.indd 22 11/29/11 3:34 PM

Confirming Pages

A Global Marketing Management Framework 23

TABLE 1-7 Measures of Marketing Performance

Dimension Measure

Market Market share

Advertising share of mind

Promotional share of mind

Consumer Customer penetration

Customer loyalty

New customers gained

Brand recognition

Brand equity

Satisfaction

Purchase intention

Innovativeness New products launched

Revenue from new products/total turnover

Financial Turnover

Contribution margin

Profits

Source: Adapted from: Ambler, T., & Xiucun, W. (2003). Measures of marketing success: a comparison between China and

the United Kingdom. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 20, 267–281.

Roche Holdings (16 percent ratio of R&D/sales), Microsoft (16 percent), Novartis

and Pfizer (15 percent), GlaxoSmithKline (14 percent) and Nokia (14 percent). All of

these firms are large global competitors. Smaller firms must spend a higher propor-

tion of their sales on R&D to compete with them. One way to do this is to outsource

research and development to lower cost regions of the world. A study by Booz Allen

Hamilton and INSEAD43 found that 75 percent of new R&D centers that were planned

were to be located in China and India.

Global Vision—The World Is My Oyster

One of the first perquisites to formulating a global marketing strategy is determining

a global vision. A strategic vision states where a company wants to go, how it will get

there, and why it should be successful in doing so. Global vision is the ability to look

into the future or the capacity to visualize the image that the company is seeking to

create on a worldwide basis. Entrepreneurs need a clear global vision to know where

to go and how to achieve their objectives.

Every year, aspiring entrepreneurs create startups with the hope that they will go

global almost instantly, but few of them survive. In some situations, starting a busi-

ness is not so difficult because entrepreneurs already have sufficient resources, which

include venture capital, a willingness to take risks and to recognize and exploit busi-

ness opportunities in the international economy. But few of them can lead their new

businesses to growth and global expansion owing to the lack of a clear vision and an

appropriate strategy. Without a clear vision, they cannot plan for the future, and thus

they are not prepared for growth, competition, and threats from changes in interna-

tional markets.

A global mission statement is also necessary for well-established firms in order to

plan for the long run. The following example is taken from Matsushita Electric Indus-

trial Company’s report to its stakeholders:

43. Duhoff, K., & Sehgal, V. (2006, Autumn). Innovators without borders. Retrieved from www.strategy-business.com/press/

article/06305.

alo29279_ch01_001-025.indd 23 11/29/11 3:34 PM

Confirming Pages

24 chapt er 1 Understanding Global Markets and Marketing

BOX 1-3 COMPANY IN FOCUS: MATSUSHITA

The current business environment remains uncer- sales ratio of 5 percent or more. . . . Furthermore, to

tain, with volatile conditions expected to continue in achieve global excellence in 2010, Matsushita will

the consumer electronics industry. Guided by its new continue efforts to realize its corporate twin vision

management, Matsushita will bolster proprietary of realizing a ubiquitous networking society and

technologies as the basis for developing competitive coexistence with the global environment. Moreover,

products, focus management resources into strate- we place a high priority on accountability for the

gic businesses, consistently strengthen management benefit of our shareholders, investors, customers,

structures, and further promote global business and all other stakeholders, and will continue efforts

expansion to achieve the targets of the Leap Ahead to further increase corporate value.