Professional Documents

Culture Documents

M1 Phonology 3

M1 Phonology 3

Uploaded by

Magdalena OgielloCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

M1 Phonology 3

M1 Phonology 3

Uploaded by

Magdalena OgielloCopyright:

Available Formats

Phonology 3

The Distance Delta

© International House London and the British Council

The Distance Delta

Phonology 3

Summary

In this input we will be dealing with the major elements of intonation. We will be looking at

the basic tones and the way that these express or reflect certain other language categories,

such as grammar, discourse etc. Through this analysis we will investigate some different

ways in which intonation can be viewed. We will go on to consider whether intonation

should be taught, and considered practical teaching ideas and materials.

Objectives

By the end of this input you will:

Have an awareness of the importance of intonation.

Have knowledge of what intonation actually consists of.

Have knowledge of the basic patterns of intonation.

Have a basic knowledge of the structural, functional, attitudinal and discoursal roles of

intonation.

Have considered some of the objections to making the rules of intonation explicit to

students, in the light of the Lingua Franca Core.

Have considered some practical ideas and materials on how to enable the learner to

recognise and produce the correct intonation patterns in appropriate contexts.

Have had experience of evaluating materials designed both to raise awareness of

intonation and to practise how to use it correctly.

1 © Copyright The Distance Delta

The Distance Delta

Contents

1. Introduction

2. A Definition of Intonation

3. The Terms of Intonation

3.1. Pitch and Range

3.2 Tone and Movement

3.3 Tone Units

3.4. Onset and Tonic Syllables

3.5. Rhythm

4. Basic Rules and Patterns of Intonation

4.1. Grammatical

4.2. Functional and Attitudinal

4.3. Discoursal

5. Intonation and the Lingua Franca Core

6. Conclusion

7. Terminology Review

Reading

2 © Copyright The Distance Delta

The Distance Delta

1. Introduction

Intonation is an area which many teachers feel insecure with. We have probably all hesitated

and wondered if we can correctly identify whether an utterance is rising or falling.

Intonation in particular is one of the most challenging phonological areas to understand. As

we shall see, there are different views as to how much detail we as teachers should go into

in focusing on intonation, if any at all. Some theorists believe the scale of exceptions and

variables involved make this area unteachable, whilst others believe it is quite possible to

identify basic rules and patterns which we can usefully show to students.

You will recall that so far in the course materials you have looked at the following:

Phonology 1: Sounds

Phonology 2: Features of Connected Speech

In Phonology 3 we will add intonation, the third component of phonology. This is not to say

that intonation is third in importance. Intonation is, for example, closely linked to grammar

and even more closely linked to discourse. More to the point, many people believe it has

profound importance for attitude and meaning, and that it can even be seen as the major

carrier of meaning. For example, it is a key component of sarcasm and irony; if we leave a

building without an umbrella and it is pouring with rain we might jokingly say ‘Oh great!’

with a flat and unenthusiastic intonation. We might equally use the same words ironically

with a falsely enthusiastic intonation. The conveying of extreme emotions can depend very

much on intonation. Intonation is even independent of language itself. If we see something

we like very much we might say no words at all, just ‘Mmm!’ Everyday life is full of

conversations in which intonation carries messages of the utmost subtlety; the slightest hint

of movement up or down in intonation is powerful enough to alter meaning.

2. A Definition of Intonation

Thornbury describes intonation thus:

Intonation has been called the ‘music’ of speech. It is the meaningful use that

speakers make of changes in their voice pitch. Intonation is a suprasegmental

feature of pronunciation, meaning that it is a property of whole stretches of

speech rather than of individual segments (such as phonemes) […] Many

3 © Copyright The Distance Delta

The Distance Delta

theories have been advanced as to the function of intonation, and the kinds of

meaning it expresses. The main candidates are:

Grammatical functions, such as indicating the difference between

statements and questions;

Attitudinal function, such as indicating interest, surprise, boredom and so

on […]

Discoursal function, such as contrasting new information with

information that is already known, and hence shared between speakers

Current theories tend to favour the last of these […] It serves both to separate

the stream of speech into blocks of information […], and to mark information

within these blocks as being significant. In English, there is a strong association

between high pitch and new information.

(Thornbury, S. 2006 An A-Z of ELT Macmillan, pp110-111)

3. The Terms of Intonation

In this section we will define the main terms used in the description of intonation.

3.1. Pitch and Range

Pitch means really what it means in the everyday phrases: ‘high-pitched’ and ‘low-pitched’.

(Remember that it has nothing to do with whether the voice is loud or soft, fast or slow).

Pitch is the relative level of speech sounds perceived by the listener.

Pitch range therefore is the distance between a speaker’s customary top and bottom note,

like the range of an opera singer, for example. Note that pitch range is not just a feature of

an individual’s speech. It can apply to languages too. Some languages have a wide pitch

range: English is notably wide, as is Chinese but other languages have a narrower pitch range

e.g. Spanish, or German. If you have experience of teaching Spanish, Italian or Arabic L1

learners you may already be aware of the challenges of widening these learners’ pitch range.

Many people might initially assume this should be the other way round but in fact it is

English, not Italian that is an ‘up and down’ language. The first thing the English learner of

Italian has to do is to flatten his range, while the Italian learner of English needs to widen

hers. On the other hand, if you have experience of teaching Brazilians you may/will know

that they share the wide pitch range of English speakers.

3.2. Tone and Movement

4 © Copyright The Distance Delta

The Distance Delta

A tone is a movement of pitch: In any tone the pitch could be high, mid or low. There are

various tones:

Rise

Fall

Fall-Rise

Rise-Fall

The movement could be rise , or fall, or it could be rise-fall or fall-rise . So a

tone could be a high rise or a low rise, it could rise from a high position (high rise - relatively

less movement) or rise from a low position (low rise - relatively more movement) or a high

fall or a low fall. That is, it could fall from a high position or from a low position.

For more on this, see Wells, J. C. 2006 English Intonation CUP, Chapter 2.

3.3. Tone Units

Spoken language can be divided into tone units. These are chunks of language, broken up

rather like phrases in written English, for example:

If you finish quickly leave the room. (The lack of comma is intentional here)

This can be chunked in 2 ways, depending on context.

a) If you finish / quickly leave the room

b) If you finish quickly / leave the room

If you look at the following utterances, again there are different ways of dividing

them up into tone units.

The man and the woman in the red car had an accident on the way home.

There could be either 3 or 4 tone units here. It depends on how many people are in the

red car.

The man /and the woman in the red car/ had an accident / on the way home.

The man and the woman in the red car /had an accident / on the way home.

Steve said the chef was brilliant.

There could be 2 or 3 tone units here. It depends on who is brilliant.

5 © Copyright The Distance Delta

The Distance Delta

Steve said / the chef was brilliant.

Steve / said the chef / was brilliant.

3.4. Onset and Tonic syllables

Gerald Kelly (in How to Teach Pronunciation, Longman, 2000, p3) reminds us that

utterances are made up of syllables.

The syllable which carries the main stress and where the main pitch movement in an

utterance takes place is the tonic syllable (sometimes also called the tonic or the

nucleus, and a term for this phenomenon is nuclear stress).

The stressed syllable before the tonic syllable is called an onset syllable.

So in the following example:

On MONday it RAINED.

a) MON is the onset syllable, which is conventionally shown in capitals.

b) RAINED is the tonic syllable which is conventionally shown in capitals and underlined,

and which is where the main pitch movement (in this case fall )occurs.

In each tone unit, there is one tonic syllable and pitch movement. The example above is one

tone unit.

3.5. Rhythm

In the section on features of connected speech, we noted that English tends to have what is

called a stress timed rhythm. In such a rhythm the stressed syllables are particularly stressed

and a varying number of unstressed syllables. It could be one, it could be as many as five or

more and they are packed into the intervals. This results in distortions, compressions and

weakening of the weak syllables. Rhythm (or speech rhythm as the Longman Dictionary of

Language Teaching and Applied Linguistics terms it) consists of a pattern of pulses of air

pressure. In English in particular, the regularity of the rhythm of these is related to meaning:

significant words or syllables in the utterance are where these pulses appear. For example,

in:

No! I certainly won’t!

The words in bold are the ones where these pulses appear.

6 © Copyright The Distance Delta

The Distance Delta

As a means of putting terms from this section into practice, look at the dialogue below. Two

people in a cafe notice a new waiter:

Customer A: I haven’t seen him before!

Customer B: No, he must be new. He’s a bit slow, isn’t he?

Customer A: Yes, but he’s probably still learning the ropes.

If we identify the most likely prominent (stressed) syllables, divide the exchange into tone

units and consider which is the most likely tonic syllable in each utterance, we might end up

with the following.

Customer A: I haven’t seen HIM before!

Customer B: NO/ he must be NEW/ He’s a bit SLOW,/ ISN’T he?

Customer A: YES/ but he’s PRObably /still learning the ROPES.

The most likely prominent (stressed) syllables are highlighted in bold, suggested tone units

are denoted by a ‘/’ and the most likely tonic syllables in each utterance are written in

capital letters.

4. Basic Rules and Patterns of Intonation

So far we have established no rules. We have simply seen that various things happen. But of

course they do not happen by chance. Intonation has its own rules, however nebulous they

may appear. It can rise, fall, fall-rise, rise-fall and so on. But what do these patterns

correspond to? There are various correspondences between intonation and other language

systems, most importantly:

Grammatical

Functional

Attitudinal

Discoursal

Of course, the rules we establish are not always reliable: Kelly says that the ‘links [of

intonation] with specific grammatical constructions or attitudes can only be loosely defined’

and furthermore, ‘grammatical and attitudinal analyses of intonation can offer no hard and

fast rules.’ (Kelly, G. 2000 How to Teach Pronunciation, Longman p87). But recall that we

7 © Copyright The Distance Delta

The Distance Delta

are dealing with rules of language here rather than rules of physics. Language is not a

rational system so we need not be dismayed by the idea that rules are not always consistent.

We will now look at how intonation functions and what patterns it displays within each

language system.

4.1. Grammatical

Here (nonetheless!) are some such rules:

Statements tend to go down: ‘He lives in London.’

Imperatives tend to go down: ‘Shut that door!’

Yes/No questions tend to go up: ‘Is she there?’

Wh questions tend to go down: ‘Where’s he gone?’

Question tags seeking confirmation tend to go down: ‘It’s a lovely day, isn’t it?’

Question tags that are only 50% sure tend to go up: ‘The exam’s on Tuesday, isn’t it?’ ’

(or is it Wednesday?)

Lists of items tend to rise on each of the items until the last when the intonation falls:

Think of this sentence: ‘I went to the supermarket and I got some bread, cheese,

pickle and some mineral water .’ There is a fall on water. Note, however, that if

your list tails away unfinished there is not this final fall. Indeed the options appear to be

still open. For example, if I come to your house and you offer me a drink you might say

‘There’s tea, coffee or juice .’ If to this list I replied ‘Have you got any herbal

tea?’, it could be considered that you are being rather awkward. If, on the other hand,

you had given me an unfinished list with a rise on the final item (‘…or juice… ?’, I could

perhaps be permitted to order ‘off menu’.

4.2. Functional and Attitudinal

As you know, functions are language or speech acts: for example, inviting, advising and

complaining are all functions. The question is whether there are connections that can be

made between functions and intonation. The problem here is that functions do not in

themselves express attitude. Intonation is an essential component in functional exponents

but it would be difficult to find a correlation between a functional category and any one

intonation pattern. After all, the same function can be fulfilled in a variety of ways. For

example a parent might say to a teenager:

‘Look, just do your bloody homework!’

8 © Copyright The Distance Delta

The Distance Delta

Or

‘Isn’t it time you got round to doing that homework for tomorrow, darling?’

So, it is therefore not the function that intonation conveys but rather the nuances of

attitude. Indeed by and large intonation expresses the attitudinal aspect of a particular

functional exponent.

Here are some of the major attitude-intonation connections:

Expressing surprise: fall-rise: did you?

Expressing interest: rise

Expressing enthusiasm: high fall

Giving polite advice: fall at the end of utterance

Criticising tactfully: low fall

If you are interested in looking into this in more detail, Wells (op. cit.) provides a very

thorough summary of attitude-intonation connections.

4.3. Discoursal

In the 1980s and 90s, there developed a more discoursal approach to intonation known as

discourse intonation (After Brazil, D., Coulthard, M. & Johns, C. 1980 Discourse Intonation in

Language Teaching Longman; Brazil, D. 1997 The Communicative Value of Intonation in

English CUP). This was a novel system consisting of fewer and simpler constituents than

previous analyses. It is also a more coherent system, and encapsulates intonation succinctly.

Before looking at discourse intonation we perhaps need to remind ourselves of the meaning

of discourse. At its most simple level, discourse is any piece of language above the sentence

level. Discourse, be it spoken or written, is held together by markers indicating shifts of

focus, references backwards and forwards and changes of topic. We have simply to say the

word ‘anyhow’ in conversation, for example, and we are signing a change in gear, signalling,

perhaps, that we are closing some issue and moving on. And intonation also helps flag up

these shifts. If we say:

‘Forget about John , what about….’

9 © Copyright The Distance Delta

The Distance Delta

We are signalling that we are going to talk about someone else. If we say: ‘Well, apparently

….’ we are probably marking the announcement of a bit of gossip. We have already

seen that an intonationally closed or open list of options (tea, coffee …?) has

significantly different meanings. Brazil, in The Communicative Value of Intonation in English

and earlier books, analysed the discoursal role of intonation more methodically. His findings

are usefully summarised in Kelly, G. 2000 How to Teach Pronunciation Longman, pp101-102

if you would like to read further on this topic.

The term ‘proclaiming tone’ refers to an intonation pattern that either rises and then falls, or

just falls. It shows that the speaker is giving new information. ‘Referring tone’ on the other

hand, falls and then rises. This refers to an intonation pattern which shows that the speaker

is referring to something that everybody already knows.

Compare the pronunciation of the name ‘Rob’ in each of the following utterances.

‘When you get to the office, you’ll see a tall man called Rob.’

‘When you see Rob, give him the file.’

In the first utterance, there is a falling tone on Rob. The speaker is expressing information

that is presumed to be new, or adding something to the discussion (so a proclaiming tone).

In the second utterance, the tone is fall/rise – a referring tone, as the speaker is referring to

information that is presumed to be shared.

(Examples from Pronunciation from Advanced Learners of English Brazil CUP 1996)

5. Intonation and the Lingua Franca Core

As we saw in Phonology 1 in the course materials, there has in the last ten years been a

move towards a simplified phonological syllabus for learners. Barbara Seidlhofer and

Jennifer Jenkins, principally, advocate a form (or forms) of English which allow for successful

communication between non-native speakers whilst not insisting on non-essential aspects of

the language which do not affect meaning. One of the features of phonology which is not

necessary to spend a lot of time perfecting is, Jenkins’ research has proven, intonation. For

a start, the nuances involved in intonation are myriad, and it would take an inordinate

amount of classroom time to familiarise students with all the shades of meaning it can carry,

let alone expect students to be able to reproduce them. Furthermore, it has been shown

10 © Copyright The Distance Delta

The Distance Delta

that native speakers do not follow the ‘rules’ of intonation explored earlier. With this in

mind, Jenkins says:

…even experienced teachers regularly have problems in identifying pitch direction

and often find that when they attempt to model a pitch pattern, it becomes

unnatural or even wrong. And if teachers have problems when pitch is brought to

the conscious level, there does not seem to be much hope for the success of their

students in terms of the overt teaching of pitch.

Jenkins, J. 2000 The Phonology of English as an International Language Oxford University

Press, p153

It would appear, then, that intonation is not to be viewed as essential if we teach English as

a Lingua Franca. What does have importance is where the tonic stress falls, however, which

Jenkins suggests is key in carrying meaning. They bought a new car is very different in

meaning to They bought a new car, for instance.

6. Conclusion

Highlighting/identifying complex intonation patterns is difficult for learners and teachers and

it is tempting to neglect intonation. However, it is possible to identify certain trends and

these can have an important impact on communication.

So:

Integrate a focus on intonation into your teaching of grammar, functions etc. A focus on

intonation can make revision of a structure interesting and challenging.

Exaggerate and encourage when modelling and practising intonation.

Distinguish between activities focusing on recognition and production.

Keep it simple. A focus on widening voice range will probably be more effective than

putting lots of energy into very specific intonation patterns.

In focusing on a specific pattern, make the link between form (the intonation) and

meaning (its effect) clear.

Concentrate on patterns relevant to your learners.

Focus on stress and rhythm together, intonation does not exist in a vacuum.

Contrast can be extremely useful for awareness raising, both between good and bad

models, and with monolingual classes, between L1 and English.

11 © Copyright The Distance Delta

The Distance Delta

Mimicry and shadowing can be useful productive practice techniques, it is often difficult

to hear/produce intonation naturally in isolation from a model.

7. Terminology Review

The terms below all refer to aspects of intonation. Can you identify what is being defined?

There is an example provided.

Example: Tonic syllable

The tonic syllable is the most prominent syllable within an utterance which carries the

main stress.

1. Pitch

2. Range

3. Tone Unit (or Tone Group)

Suggested Answers

1. Pitch is the level of the voice as perceived by the listener, either ‘high’, ‘mid’ or ‘low’.

2. Range (or Voice range) is the distance between the lowest pitch of a language and the

highest. The range of English is very wide; other languages less so.

3. Tone unit (or Tone Group) a sub-division of an utterance which contains a tonic syllable.

Tone units are usually represented by slanted lines as in ‘She got here / just after 8.00

o’clock.’ This utterance comprises two tone groups. Longer pauses are sometimes

indicated by double slanted lines.

12 © Copyright The Distance Delta

The Distance Delta

Reading:

Although not essential to your Module 1 preparation, if you would like to explore this area

further we suggest the following:

Suggested Reading

Kelly, G. 2000 How to Teach Pronunciation Longman

Roach, P. 2001 Phonetics OUP

Additional Reading

Bradford, B. 1988 Intonation in Context Cambridge University Press

Brazil, D. 1997 The Communicative Value of Intonation in English Cambridge

Kenworthy, J. 1987 Teaching English Pronunciation Longman

Underhill, A. 1994 Sound Foundations Heinemann University Press

Wells, J. C. 2006 English Intonation CUP

Classroom Teaching Materials

Bradford, B. 1988 Intonation in Context Cambridge University Press

Vaughan-Rees, M. 1994 Rhymes and Rhythm (Intermediate) Prentice Hall

O’Connor, J. D. & Fletcher, C. 1989 Sounds English Longman

Haycraft, B. 1994 English Aloud 1 & 2 Heinemann

Bowler, B. & Parminter, S. 1992 Headway Pre-Intermediate Pronunciation Oxford University

Press

Bowler, B. & Cunningham, S. 1990 Headway Intermediate Pronunciation Oxford University

Press

Bowler, B. & Cunningham, S. 1991 Headway Upper Intermediate Pronunciation Oxford

University Press

13 © Copyright The Distance Delta

You might also like

- Angel Correa-Pedreros - LSA 1 Final Lesson Plan - DELTA Module 2Document19 pagesAngel Correa-Pedreros - LSA 1 Final Lesson Plan - DELTA Module 2ÁngelNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Venn DiagramsDocument2 pagesLesson Plan Venn DiagramsMatet Lara100% (2)

- 4.10. The Data in Table 4.4 Are To Be Fit To An Eq...Document1 page4.10. The Data in Table 4.4 Are To Be Fit To An Eq...Ahmad AbdNo ratings yet

- M1 Exam Training 5Document25 pagesM1 Exam Training 5Mahgoub AlarabiNo ratings yet

- Jungle Listening Teachers PagesDocument21 pagesJungle Listening Teachers PagesAlexandar ApishaNo ratings yet

- M1 Language Systems GrammarDocument16 pagesM1 Language Systems GrammarMahgoub AlarabiNo ratings yet

- Aimcat 1801 Expert ReviewDocument2 pagesAimcat 1801 Expert Reviewmohit kumarNo ratings yet

- International Handbook of Neuropsychological Rehabilitation PDFDocument376 pagesInternational Handbook of Neuropsychological Rehabilitation PDFTlaloc Gonzalez100% (2)

- Up-Selling in Restaurants: Akshay KhannaDocument39 pagesUp-Selling in Restaurants: Akshay KhannaSagar Chougule100% (1)

- M1 Language Systems RevisionDocument10 pagesM1 Language Systems RevisionMagdalena OgielloNo ratings yet

- Speaking: The Distance DeltaDocument23 pagesSpeaking: The Distance DeltaMagdalena OgielloNo ratings yet

- Exam Practice: Unit 7: The Distance DeltaDocument7 pagesExam Practice: Unit 7: The Distance DeltaMahgoub AlarabiNo ratings yet

- Unit 4. Discourse AnalysisDocument21 pagesUnit 4. Discourse AnalysisSamina Shamim100% (1)

- M1 Focus On The LearnerDocument21 pagesM1 Focus On The LearnerMagdalena OgielloNo ratings yet

- M1 Error AnalysisDocument19 pagesM1 Error AnalysisMagdalena OgielloNo ratings yet

- Delta: Syllabus SpecificationsDocument16 pagesDelta: Syllabus SpecificationsSamina ShamimNo ratings yet

- Professional Development Assignment - Reflection and Action: Centre: 10239 The Distance Delta Date: Name: Word CountDocument13 pagesProfessional Development Assignment - Reflection and Action: Centre: 10239 The Distance Delta Date: Name: Word CountDragica ZdraveskaNo ratings yet

- M2 PDA Experimental Practice GuidelinesDocument11 pagesM2 PDA Experimental Practice Guidelinesjorge chaconNo ratings yet

- Delta Module 2 Course ASSIGNMENT LSA 4 LDocument20 pagesDelta Module 2 Course ASSIGNMENT LSA 4 LYeliz IkisNo ratings yet

- Unit1 - Unit 1 Module One Standalone Exam Practice Paper 1 Task Four 12finalDocument2 pagesUnit1 - Unit 1 Module One Standalone Exam Practice Paper 1 Task Four 12finalmcgwart0% (1)

- M1 ListeningDocument37 pagesM1 ListeningMagdalena Ogiello100% (1)

- Resources and MaterialsDocument67 pagesResources and MaterialsLindsey CottleNo ratings yet

- Plagiarism A Guide For Delta Module Three PDFDocument12 pagesPlagiarism A Guide For Delta Module Three PDFSamina ShamimNo ratings yet

- Unit 1. First Language Acquisition TheoryDocument16 pagesUnit 1. First Language Acquisition TheorySamina ShamimNo ratings yet

- Helping Intermediate Learners Manage Interactive ConversationsDocument29 pagesHelping Intermediate Learners Manage Interactive ConversationsChris ReeseNo ratings yet

- Exam Training: General Introduction: The Distance Delta Module OneDocument7 pagesExam Training: General Introduction: The Distance Delta Module OneAlexNo ratings yet

- Grammar BackgroundDocument10 pagesGrammar Backgroundpandreop100% (1)

- Distance Delta Phonology 2Document27 pagesDistance Delta Phonology 2juliaayscoughNo ratings yet

- RitsIILCS 8.1pp.183 193peatyDocument13 pagesRitsIILCS 8.1pp.183 193peatyMartha Peraki100% (1)

- Jenifer Jenkins: Which Pronunciatin NormsDocument8 pagesJenifer Jenkins: Which Pronunciatin NormsHodinarNo ratings yet

- M1 Further Practice 4Document3 pagesM1 Further Practice 4Magdalena OgielloNo ratings yet

- Task Based Learning PDFDocument11 pagesTask Based Learning PDFGerardo Cangri100% (2)

- BG005 005 Ibraimof Internal LSA4 BEDocument13 pagesBG005 005 Ibraimof Internal LSA4 BELiliana IbraimofNo ratings yet

- Sample 1 CollocationsDocument32 pagesSample 1 CollocationsZeynep BeydeşNo ratings yet

- Analysing A Sample LSA (Skills) BEDocument23 pagesAnalysing A Sample LSA (Skills) BECPPE ARTENo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Delta NEW To SubmitDocument8 pagesLesson Plan Delta NEW To SubmitDragica ZdraveskaNo ratings yet

- DELTA - AssumptionsDocument4 pagesDELTA - AssumptionsEmily James100% (1)

- Bell, C 2012 Specialised VocabularyDocument3 pagesBell, C 2012 Specialised VocabularyjuliaayscoughNo ratings yet

- Blank NeedsAnalysisDocument3 pagesBlank NeedsAnalysisBenGreenNo ratings yet

- Exam Practice: Unit 2: The Distance DeltaDocument6 pagesExam Practice: Unit 2: The Distance DeltaMahgoub AlarabiNo ratings yet

- Dogme ELT - What Do Teachers and Students Think?Document12 pagesDogme ELT - What Do Teachers and Students Think?Karolina CiNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Lsa 2 Skills (Speaking) : TitleDocument13 pagesLesson Plan Lsa 2 Skills (Speaking) : TitleZeynep Beydeş100% (1)

- Delta 5a Criteria - BEDocument4 pagesDelta 5a Criteria - BERamsey MooreNo ratings yet

- Read and Answer The Following Questions: Needs AnalysisDocument3 pagesRead and Answer The Following Questions: Needs AnalysisGilberto Maldonado MartínezNo ratings yet

- Background Essay LSA Skills (Speaking)Document12 pagesBackground Essay LSA Skills (Speaking)Zeynep BeydeşNo ratings yet

- Review - Teaching Second Language ReadingDocument3 pagesReview - Teaching Second Language ReadingadamcomNo ratings yet

- Language Analysis (Meaning/Appropriacy/Use Form Phonology) For Each ItemDocument15 pagesLanguage Analysis (Meaning/Appropriacy/Use Form Phonology) For Each Itemgareth118100% (1)

- Helping Intermediate Learners To Develop Their Reading Proficiency Through InferencingDocument10 pagesHelping Intermediate Learners To Develop Their Reading Proficiency Through InferencingAhmed RaghebNo ratings yet

- High Frequency Phrasal Verbs For Elementary Level StudentsDocument14 pagesHigh Frequency Phrasal Verbs For Elementary Level StudentsKhara Burgess100% (1)

- Unit 3. Language Teaching MethodologyDocument21 pagesUnit 3. Language Teaching MethodologySamina ShamimNo ratings yet

- Delta 5a: Module Two Report For The Language Systems and Language Skills AssignmentsDocument9 pagesDelta 5a: Module Two Report For The Language Systems and Language Skills AssignmentsEmily JamesNo ratings yet

- Delta PrepDocument40 pagesDelta PrepJames BruckNo ratings yet

- PronunciationDocument6 pagesPronunciationkirsy_perez100% (1)

- Language Systems Assignment: Raise Awareness of Delexicalised Verbs and Their Collocates To Intermediate Level StudentsDocument9 pagesLanguage Systems Assignment: Raise Awareness of Delexicalised Verbs and Their Collocates To Intermediate Level StudentsEleni Vrontou100% (1)

- D8 Lexis Focus Teaching AssignmentsM2v2Document5 pagesD8 Lexis Focus Teaching AssignmentsM2v2Zulfiqar Ahmad100% (2)

- Warsaw Delta Course DetailsDocument6 pagesWarsaw Delta Course DetailsWalid WalidNo ratings yet

- Language Systems Assignment 4 - Lexis: Helping Lower-Level Learners Understand and Use Phrasal VerbsDocument10 pagesLanguage Systems Assignment 4 - Lexis: Helping Lower-Level Learners Understand and Use Phrasal VerbsEmily JamesNo ratings yet

- M1 Exam Training 6Document34 pagesM1 Exam Training 6Magdalena OgielloNo ratings yet

- UI Learner ProfilesDocument3 pagesUI Learner ProfilesEmily JamesNo ratings yet

- Are Is Alves Process Writing LTMDocument24 pagesAre Is Alves Process Writing LTMM Nata DiwangsaNo ratings yet

- Language Systems Assignment 4 - Lexis: Helping Lower-Level Learners Understand and Use Phrasal VerbsDocument10 pagesLanguage Systems Assignment 4 - Lexis: Helping Lower-Level Learners Understand and Use Phrasal VerbsEmily JamesNo ratings yet

- M1 Further Practice 3Document3 pagesM1 Further Practice 3Magdalena OgielloNo ratings yet

- Speaking: The Distance DeltaDocument23 pagesSpeaking: The Distance DeltaMagdalena OgielloNo ratings yet

- M1 Further Practice 4Document3 pagesM1 Further Practice 4Magdalena OgielloNo ratings yet

- MurderDocument3 pagesMurderMagdalena OgielloNo ratings yet

- Teaching in IrelandDocument1 pageTeaching in IrelandMagdalena OgielloNo ratings yet

- M1 ListeningDocument37 pagesM1 ListeningMagdalena Ogiello100% (1)

- M1 Lexis 2Document33 pagesM1 Lexis 2Magdalena OgielloNo ratings yet

- M1 Methods and Trends in ELTDocument28 pagesM1 Methods and Trends in ELTShaun MulhollandNo ratings yet

- M1 Language Systems RevisionDocument10 pagesM1 Language Systems RevisionMagdalena OgielloNo ratings yet

- M1 Error AnalysisDocument19 pagesM1 Error AnalysisMagdalena OgielloNo ratings yet

- M1 Focus On The LearnerDocument21 pagesM1 Focus On The LearnerMagdalena OgielloNo ratings yet

- MurderDocument3 pagesMurderMagdalena OgielloNo ratings yet

- Object Pronouns: Activity TypeDocument2 pagesObject Pronouns: Activity TypeMagdalena OgielloNo ratings yet

- School of Information Technology and Engineering DA1 - : Registe RNO Name TopicDocument3 pagesSchool of Information Technology and Engineering DA1 - : Registe RNO Name TopicPranav MahalpureNo ratings yet

- Rancangan: Pengajaran Tahunan KSSR Semakan TahunDocument6 pagesRancangan: Pengajaran Tahunan KSSR Semakan TahunNADIA ATMA BINTI AHMAD THAMIN MoeNo ratings yet

- Banco Mundial - Evaluaciones A Gran EscalaDocument163 pagesBanco Mundial - Evaluaciones A Gran EscalaCristian Alejandro Lopez VeraNo ratings yet

- Pedagogical GrammarDocument2 pagesPedagogical GrammarItalia GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Pud Unit 1 - 4 A 6to GradoDocument6 pagesPud Unit 1 - 4 A 6to GradoERIKA VARGASNo ratings yet

- The Concept of CultureDocument14 pagesThe Concept of CultureAleandra Reyno RiveraNo ratings yet

- Introductory Lesson: For The Beginning of Each New YearDocument4 pagesIntroductory Lesson: For The Beginning of Each New YearvskanchiNo ratings yet

- Supervisory Skills: Educational SupervisionDocument30 pagesSupervisory Skills: Educational Supervisionanna100% (1)

- CORE Introduction To Philosophy of The Human Person Q1Week1Document14 pagesCORE Introduction To Philosophy of The Human Person Q1Week1tan2masNo ratings yet

- DLP IdsDocument7 pagesDLP IdsDnnlyn CstllNo ratings yet

- A Detailed Lesson Plan in ComputerDocument4 pagesA Detailed Lesson Plan in ComputerAngela Mari ElepongaNo ratings yet

- Disciplinary LiteracyDocument5 pagesDisciplinary Literacyapi-488067914No ratings yet

- Lyut Become Ana and Makes Abstract Noun When Added To Verbal RootDocument2 pagesLyut Become Ana and Makes Abstract Noun When Added To Verbal RootRam DoyalNo ratings yet

- A World Leading Hypnosis School - Hypnotherapy Training InstituteDocument6 pagesA World Leading Hypnosis School - Hypnotherapy Training InstitutesalmazzNo ratings yet

- Grossing, Staging, and Reporting: An Integrated Manual of Modern Surgical PathologyDocument6 pagesGrossing, Staging, and Reporting: An Integrated Manual of Modern Surgical PathologySOUMYA DEYNo ratings yet

- Thermo 2Document26 pagesThermo 2Marcial Jr. Militante100% (1)

- Indian Medical Association: Family Security SchemeDocument2 pagesIndian Medical Association: Family Security SchemeAmol DhanvijNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 ReadingDocument2 pagesUnit 1 ReadingaNo ratings yet

- Week 3 Diss-Home-Learning PlanDocument6 pagesWeek 3 Diss-Home-Learning PlanMaricar Tan Artuz50% (2)

- Jun 2015Document60 pagesJun 2015Excequiel QuezadaNo ratings yet

- Internal Auditing: Assurance and Advisory Services.3Document10 pagesInternal Auditing: Assurance and Advisory Services.3Alex ChanNo ratings yet

- Testing ClassDocument10 pagesTesting ClassravinyseNo ratings yet

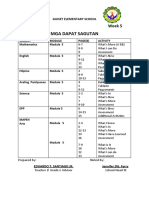

- Mga Dapat Sagutan: Grade 6 - EARTH Week 5Document3 pagesMga Dapat Sagutan: Grade 6 - EARTH Week 5Jhun SantiagoNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Internet Service ProvidersDocument9 pagesLiterature Review On Internet Service Providersafdtlgezo100% (1)

- Nadeem A Khan ResumeDocument3 pagesNadeem A Khan Resumemaxie1024No ratings yet