Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology

Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology

Uploaded by

fulgentius juliCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Lippincott 39 S Anesthesia Review 1001 Questions A PDFDocument429 pagesLippincott 39 S Anesthesia Review 1001 Questions A PDFPeter Kazarin50% (2)

- Neurocritical Care Management of The Neurosurgical Patient (PDFDrive)Document510 pagesNeurocritical Care Management of The Neurosurgical Patient (PDFDrive)Chanatthee KitsiripantNo ratings yet

- Methergine Drug StudyDocument3 pagesMethergine Drug StudyQueenie Puzon80% (5)

- Tulio E. Bertorini - Neuromuscular DisordersDocument466 pagesTulio E. Bertorini - Neuromuscular DisordersLeila Gonzalez100% (1)

- Propofol SynthesisDocument8 pagesPropofol SynthesisGiorgos Doukas Karanasios0% (1)

- LIBRO NEURO UCI 2013 Monitoring in Neurocritical CareDocument602 pagesLIBRO NEURO UCI 2013 Monitoring in Neurocritical CareDiana Reaño RuizNo ratings yet

- C+F-Restraint Methoda For Radiography in Dogs and CatsDocument13 pagesC+F-Restraint Methoda For Radiography in Dogs and Catstaner_soysurenNo ratings yet

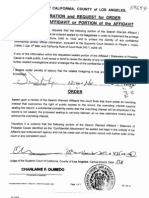

- Search Warrants: Re: Dr. Conrad Murray Manslaughter ChargesDocument47 pagesSearch Warrants: Re: Dr. Conrad Murray Manslaughter ChargesBetsy A. RossNo ratings yet

- DeliriumDocument15 pagesDeliriumRobin gruNo ratings yet

- Clinical Patterns and Biological Correlates of Cognitive Dysfunction Associated To Cancer TreatmentDocument12 pagesClinical Patterns and Biological Correlates of Cognitive Dysfunction Associated To Cancer TreatmentRodolfo BenavidesNo ratings yet

- Neurological Complications of Surgery and AnaesthesiaDocument14 pagesNeurological Complications of Surgery and Anaesthesiarian rantungNo ratings yet

- Preoperative Assessment of The Older Patient: C.L. Pang, M. Gooneratne and J.S.L. PartridgeDocument7 pagesPreoperative Assessment of The Older Patient: C.L. Pang, M. Gooneratne and J.S.L. Partridgealejandro montesNo ratings yet

- A Clinical Update On Delirium: From Early Recognition To Effective ManagementDocument13 pagesA Clinical Update On Delirium: From Early Recognition To Effective ManagementNabila MarsaNo ratings yet

- Postoperative Cognitive Dysfunction and Dementia: What We Need To Know and DoDocument11 pagesPostoperative Cognitive Dysfunction and Dementia: What We Need To Know and Dofulgentius juliNo ratings yet

- Psychiatric Outcomes After Temporal Lobe Surgery in Patients With Temporal Lobe Epilepsy and Comorbid Psychiatric IllnessDocument8 pagesPsychiatric Outcomes After Temporal Lobe Surgery in Patients With Temporal Lobe Epilepsy and Comorbid Psychiatric IllnessFrancisco Javier Fierro RestrepoNo ratings yet

- Bench-To-Bedside Review - Brain Dysfunction in Critically Ill Patients - The Intensive Care Unit and BeyondDocument9 pagesBench-To-Bedside Review - Brain Dysfunction in Critically Ill Patients - The Intensive Care Unit and Beyondthomas.szapiroNo ratings yet

- Frara 2020Document12 pagesFrara 2020anocitora123456789No ratings yet

- Evaluation of The Efficacy of Fascia Iliaca Compartment Block in Maintaining Cognitive Function Post-Surgery in Elderly Individuals With Hip FracturesDocument12 pagesEvaluation of The Efficacy of Fascia Iliaca Compartment Block in Maintaining Cognitive Function Post-Surgery in Elderly Individuals With Hip FracturesInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Markers & RX of Brain Dysfunction. Crit CareDocument9 pagesMarkers & RX of Brain Dysfunction. Crit CareParvathy R NairNo ratings yet

- Jama Vacas 2021 It 210019 1630095346.97965Document2 pagesJama Vacas 2021 It 210019 1630095346.97965Juan Carlos Perez ParadaNo ratings yet

- Sedation, Delirium, and Cognitive Function After Criticall IlnessDocument14 pagesSedation, Delirium, and Cognitive Function After Criticall IlnessPsiquiatría CESAMENo ratings yet

- Cesarean Section in Post-Polio PatientDocument2 pagesCesarean Section in Post-Polio PatientasclepiuspdfsNo ratings yet

- Ancelin 2010Document9 pagesAncelin 2010chuckNo ratings yet

- 2006, Vol.24, Issues 1, Brain Injury and Cardiac ArrestDocument169 pages2006, Vol.24, Issues 1, Brain Injury and Cardiac ArrestKishore Reddy BhavanamNo ratings yet

- Kluger 2019Document3 pagesKluger 2019Ana LopezNo ratings yet

- Critical Care Issues of TheDocument11 pagesCritical Care Issues of TheJEFFERSON MUÑOZNo ratings yet

- Critical Care Issues of TheDocument11 pagesCritical Care Issues of TheJEFFERSON MUÑOZNo ratings yet

- PsychologyDocument7 pagesPsychologyHarish KumarNo ratings yet

- Medico Legal Aspects of Severe Traumatic Brain InjuryDocument17 pagesMedico Legal Aspects of Severe Traumatic Brain InjuryIrv CantorNo ratings yet

- Final Draft-Long-Term Cognitive ImpairmentDocument6 pagesFinal Draft-Long-Term Cognitive Impairmentapi-237094717No ratings yet

- Delirium in The Intensive Care UnitDocument9 pagesDelirium in The Intensive Care Uniton miniNo ratings yet

- Contoh Case StudyDocument11 pagesContoh Case StudyNovitaSariNo ratings yet

- 2018 Imp Roving Long - Te RM Outcomes After SepsisDocument14 pages2018 Imp Roving Long - Te RM Outcomes After SepsisgiseladlrNo ratings yet

- Cardiac Surgery, The Brain, and Inflammation: Expert ReviewsDocument8 pagesCardiac Surgery, The Brain, and Inflammation: Expert ReviewsArif Susilo RahadiNo ratings yet

- A Síndrome de Cuidados Pós-Neurointensivos É Realmente Uma CoisaDocument2 pagesA Síndrome de Cuidados Pós-Neurointensivos É Realmente Uma CoisaMaiquiel MaiaNo ratings yet

- 2019 Article 903Document12 pages2019 Article 903ArolNo ratings yet

- PrintArticle 72003Document7 pagesPrintArticle 72003Sadhi RashydNo ratings yet

- Neuro in The ICUDocument4 pagesNeuro in The ICUEduardo GarciaNo ratings yet

- An Update On Cancer-And Chemotherapy - Related Cognitive Dysfunction: Current StatusDocument8 pagesAn Update On Cancer-And Chemotherapy - Related Cognitive Dysfunction: Current StatusgorklanNo ratings yet

- GMHAT - Cardiac Patients Reino UnidoDocument7 pagesGMHAT - Cardiac Patients Reino UnidoIleana AjaNo ratings yet

- Palliative Care and End-Of-Life Care in Adults With Malignant Brain TumorsDocument10 pagesPalliative Care and End-Of-Life Care in Adults With Malignant Brain TumorsLaras Adythia PratiwiNo ratings yet

- Comp Il CationDocument8 pagesComp Il CationWahyu Permata LisaNo ratings yet

- Chemotherapy Related Cog. Dysf.Document9 pagesChemotherapy Related Cog. Dysf.Manuel Guerrero GómezNo ratings yet

- 2012 Rehabilitation of Brachial Plexus Injuries in Adults and ChildrenDocument24 pages2012 Rehabilitation of Brachial Plexus Injuries in Adults and ChildrenchayankkuNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Impairment in Patients With End-Stage Renal Disease: Accelerated Brain Aging?Document9 pagesCognitive Impairment in Patients With End-Stage Renal Disease: Accelerated Brain Aging?Debora BergerNo ratings yet

- 4-Treatment of Advanced Parkinson Ds - Continuum (2016)Document13 pages4-Treatment of Advanced Parkinson Ds - Continuum (2016)bernarduswidodoNo ratings yet

- Anna PIECZYŃSKA 2022Document9 pagesAnna PIECZYŃSKA 2022PPDS Rehab Medik UnhasNo ratings yet

- A. Discussion of The Health ConditionDocument5 pagesA. Discussion of The Health ConditionPeter AbellNo ratings yet

- Inouye 15 JacsDocument48 pagesInouye 15 JacsPsiquiatría CESAMENo ratings yet

- Pocd 2Document21 pagesPocd 2fulgentius juliNo ratings yet

- Psychosurgery, Epilepsy Surgery, or Surgical Psychiatry: The Tangled Web of Epilepsy and Psychiatry As Revealed by Surgical OutcomesDocument2 pagesPsychosurgery, Epilepsy Surgery, or Surgical Psychiatry: The Tangled Web of Epilepsy and Psychiatry As Revealed by Surgical Outcomesximena sanchezNo ratings yet

- Management of Traumatic Brain Injury PatientsDocument14 pagesManagement of Traumatic Brain Injury Patientsyayaslaras96No ratings yet

- A Missing Piece? Neuropsychiatric Functioning in Untreated Patients With Tumors Within The Cerebellopontine AngleDocument9 pagesA Missing Piece? Neuropsychiatric Functioning in Untreated Patients With Tumors Within The Cerebellopontine AnglejuandellibroNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Cognitive Rehabilitation On Memory Outcome After Temporal Lobe Epilepsy SurgeryDocument8 pagesThe Effects of Cognitive Rehabilitation On Memory Outcome After Temporal Lobe Epilepsy SurgeryLaura Arbelaez ArcilaNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Brain InjuryDocument8 pagesLiterature Review Brain Injuryafdtwudac100% (1)

- Medi 97 E10919Document4 pagesMedi 97 E10919oktaviaNo ratings yet

- Delirium in The Intensive Care Unit: ReviewDocument9 pagesDelirium in The Intensive Care Unit: ReviewCristopher Castro RdNo ratings yet

- Dafang Wu - Clinical Nuclear Medicine Neuroimaging - An Instructional Casebook-Springer (2020)Document394 pagesDafang Wu - Clinical Nuclear Medicine Neuroimaging - An Instructional Casebook-Springer (2020)newhopeclub03reeceNo ratings yet

- Delirium After Deep Brain Stimulation in Parkinson's DiseaseDocument10 pagesDelirium After Deep Brain Stimulation in Parkinson's DiseaseMikeVDCNo ratings yet

- Palliative Care For Neurologically Injured Patients: Why and How?Document8 pagesPalliative Care For Neurologically Injured Patients: Why and How?jumabarrientosNo ratings yet

- Stroke in Terminal Illness Patients: ANDIKA FAHRIAN (J210184101) NAMAYANJA SUMAYIYAH (J210184205)Document15 pagesStroke in Terminal Illness Patients: ANDIKA FAHRIAN (J210184101) NAMAYANJA SUMAYIYAH (J210184205)Namayanja SumayiyahNo ratings yet

- Whittaker Et Al-2022-Scientific ReportsDocument22 pagesWhittaker Et Al-2022-Scientific ReportsAlex WhittakerNo ratings yet

- Neuro-Oncology Practice: Integration of Palliative Care Into The Neuro-Oncology Practice: Patterns in The United StatesDocument5 pagesNeuro-Oncology Practice: Integration of Palliative Care Into The Neuro-Oncology Practice: Patterns in The United StatessiscaNo ratings yet

- Greene 2019 NeurologicDocument18 pagesGreene 2019 NeurologicangelNo ratings yet

- Rapid Sequence Intubation (RSI) Outside of The Operating Room in Children: Medications For Sedation and ParalysisDocument20 pagesRapid Sequence Intubation (RSI) Outside of The Operating Room in Children: Medications For Sedation and ParalysisLORENA ALEJANDRA RUIZ ARDILANo ratings yet

- Therapeutic IndexDocument8 pagesTherapeutic IndexMary Jennel RosNo ratings yet

- Teknik Anestesi UmumDocument128 pagesTeknik Anestesi UmumRiezka HanafiahNo ratings yet

- Drugs at ORDocument16 pagesDrugs at ORAngelo MangibinNo ratings yet

- Types of AnesthesiaDocument27 pagesTypes of Anesthesiasncmanguiat.2202276.chasnNo ratings yet

- Air Medical Journal: David J. Dries, MSE, MDDocument4 pagesAir Medical Journal: David J. Dries, MSE, MDKat E. KimNo ratings yet

- Should Norepinephrine, Rather Than PhenylephrineDocument8 pagesShould Norepinephrine, Rather Than PhenylephrineDiego Andres Rojas TejadaNo ratings yet

- Induction Drugs Used in Anaesthesia - Update 24 2 2008Document5 pagesInduction Drugs Used in Anaesthesia - Update 24 2 2008Alisya NadhilahNo ratings yet

- AnesthesiaDocument10 pagesAnesthesiaMohamed EssamNo ratings yet

- Tintinalli - Chapter 37 Procedural Sedation and Analgesia in AdultsDocument11 pagesTintinalli - Chapter 37 Procedural Sedation and Analgesia in AdultsPgmee KimsNo ratings yet

- Multiple Choice Questions: Childhood Obesity and The AnaesthetistDocument5 pagesMultiple Choice Questions: Childhood Obesity and The AnaesthetistTanishka GargNo ratings yet

- Pocket Anesthesia Pocket Notseries 3Rd Edition PDF Full Chapter PDFDocument53 pagesPocket Anesthesia Pocket Notseries 3Rd Edition PDF Full Chapter PDFheemstgarrow100% (4)

- Anesthesia For Pancreatic DiseaseDocument4 pagesAnesthesia For Pancreatic DiseaseAuan SurapaNo ratings yet

- BenzodiazepinesDocument35 pagesBenzodiazepinesanaeshklNo ratings yet

- Sedation in The Intensive Care Unit: Katherine Rowe MBCHB MRCP Frca Simon Fletcher Mbbs Frca FrcpeDocument6 pagesSedation in The Intensive Care Unit: Katherine Rowe MBCHB MRCP Frca Simon Fletcher Mbbs Frca FrcpeMohammed IrfanNo ratings yet

- Anesthesia of The Equine Neonate in Health and DiseaseDocument19 pagesAnesthesia of The Equine Neonate in Health and DiseaseIsabel VergaraNo ratings yet

- Anesthetic Management of Geriatric Patients: Review ArticleDocument22 pagesAnesthetic Management of Geriatric Patients: Review Articleagita kartika sariNo ratings yet

- Tiva en NiñosDocument22 pagesTiva en NiñosAndre EstupiñanNo ratings yet

- GENERAL ANESTHETICS PDF Document With Practice QuestionsDocument30 pagesGENERAL ANESTHETICS PDF Document With Practice QuestionsFlowerNo ratings yet

- Calculations Master Class 2020Document52 pagesCalculations Master Class 2020Esraa AbdelfattahNo ratings yet

- GA (General Anestesi)Document7 pagesGA (General Anestesi)salfany try nNo ratings yet

- Preanaesthetic Medication Anaesthetic AgentsDocument35 pagesPreanaesthetic Medication Anaesthetic AgentsSubhash BeraNo ratings yet

- Management of Sedation and Delirium in Ventilated ICU PatientsDocument35 pagesManagement of Sedation and Delirium in Ventilated ICU PatientsJheng-Dao YangNo ratings yet

- Anesthesia in Birds and Exotic Pet Animals: Ganga Prasad Yadav M.V.Sc. Veterinary Surgery & RadiologyDocument54 pagesAnesthesia in Birds and Exotic Pet Animals: Ganga Prasad Yadav M.V.Sc. Veterinary Surgery & RadiologygangaNo ratings yet

- Drug StudyDocument9 pagesDrug StudyVicenia BalloganNo ratings yet

Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology

Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology

Uploaded by

fulgentius juliOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology

Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology

Uploaded by

fulgentius juliCopyright:

Available Formats

ISSN: 2469-5858

Detweiler. J Geriatr Med Gerontol 2018, 4:038

DOI: 10.23937/2469-5858/1510038

Volume 4 | Issue 1

Journal of Open Access

Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology

CommentarY

Postoperative Cognitive Dysfunction: What Anesthesiologists Know

That Would Benefit Geriatric Specialists

Mark B. Detweiler1,2,3*

1

Staff Psychiatrist, Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Salem, Virginia, USA Check for

updates

2

Professor of Psychiatry, Via College of Osteopathic Medicine, Blacksburg, Virginia, USA

3

Director Geriatric Research Group, Department of Psychiatry, Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Salem,

Virginia, USA

*Corresponding author: Mark B. Detweiler, MD, MS, Director Geriatric Research Group, Department of Psychiatry, Veter-

ans Affairs Medical Center, Salem, Virginia, USA; Professor of Psychiatry, Via College of Osteopathic Medicine, Blacksburg,

Virginia, USA; Staff Psychiatrist, Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Salem, Virginia, USA, E-mail: mark.detweiler1@va.gov

Post-operative cognitive decline (POCD) in the elder- Some of the more common surgeries associated

ly is well known to the anesthesiologists, but others are with POCD are cardiovascular and orthopedic interven-

not as knowledgeable about this complex phenomenon tions such as hip and spinal interventions. In some cases

and its causes. POCD is characterized by a slowing of of consecutive surgeries in the elderly, there is an incre-

brain processing speed, deficits in memory and exec- mental cognitive decline with each successive surgery,

utive function, in addition to other neuropsychological replicating the step-wise decrement seen in vascular

domains [1]. POCD is also associated with permanent dementia [15] and in persons with multiple traumat-

brain damage, especially in those populations with ic brain injuries [16]. The case dependent risk factors

more vulnerable central nervous systems due to age, for COPD in the elderly such as advanced age, genetic

children under two years of age and, increasingly, the disposition, pre-existing cognitive impairment, pre-ex-

elderly [1-10]. Although the problem of POCD has been isting inflammatory conditions, pattern of diurnal vari-

reported in the literature for over a century and re- ation in cortisol level [12], complexity and duration of

mains an ongoing interest in anesthesia research today surgery and anesthesia, postoperative delirium and in-

[9], it is largely unknown among many clinicians such fection. Several modifiable risk factors include pre- and

as family practitioners, internal medicine specialists and post-surgery pain, use of potentially neurotoxic drugs

geriatricians that have daily contact with the elderly. It and low intraoperative cerebral oxygenation.

has been estimated that approximately 41 percent of

elderly patients demonstrate some cognitive impair- As clinicians, we see many of our geriatric patients

ment following surgery with anesthesia [6,7]. With the emerge from major surgery with both transitory and

increasing number of elderly undergoing surgery with permanent cognitive changes which may cause fear and

general anesthesia worldwide, problems with POCD fol- threaten their independence. The pervasive symptoms

lowing surgery is an important topic in clinical medicine of POCD usually are reported to the family practitioners,

[11,12]. Given the scientific evidence in anesthesia lit- internists and geriatricians as static or progressing men-

erature and the growing anecdotal evidence of POCD, tal status changes along the continuum of cognitive de-

primarily among clinicians treating the elderly, there cline following surgery. Such situations provoke anxiety

appears to be the need for a more interdisciplinary dis- if the patient has not had presurgical education from

cussion regarding the risks and the long term effects of their internist or geriatric clinician about the risks of

POCD that are costly for both health care systems and POCD. This is often due to a lack of medical team knowl-

for the quality of life of the affected individuals [13,14]. edge about POCD sequalae.

Citation: Detweiler MB (2018) Postoperative Cognitive Dysfunction: What Anesthesiologists Know That

Would Benefit Geriatric Specialists. J Geriatr Med Gerontol 4:038. doi.org/10.23937/2469-5858/1510038

Received: July 11, 2017: Accepted: February 22, 2018: Published: February 24, 2018

Copyright: © 2018 Detweiler MB. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the

Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction

in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Detweiler. J Geriatr Med Gerontol 2018, 4:038 • Page 1 of 5 •

DOI: 10.23937/2469-5858/1510038 ISSN: 2469-5858

Frequently the elderly that experience POCD do anesthesia in the inpatient and outpatient settings. The

not discuss their memory problems with their medical choice of anesthesia may reduce cognitive complica-

team as they fear being diagnosed as having “psychi- tions such as delirium and POCD [12]. Some hospitals

atric problems” [17]. When patients present in clinic are routinely utilizing 2,6-diisopropylphenol (propofol)

with reports of POCD, if the treatment team does not with a benzodiazepine, ketamine or fentanyl during

have an explanation or neglects to offer a plan to treat conscious sedation during both ambulatory surgery and

the symptoms, the afflicted individuals remain anxious, inpatient surgery for appropriate elderly patients [35-

fearful and often attempt to ignore their memory loss as 39]. Propofol when used in conjunction with fentanyl

they may be under the impression that there is no med- appears to be a safe, quick, and effective method of pro-

ical explanation or treatment. Unfortunately the stress viding conscious sedation which is advantageous for the

associated with the fears of losing one’s memory and/or elderly, especially during spinal and neurological blocks

having psychiatric problems often accelerates cognitive in the effort to avoid general anesthesia [35]. Propofol

degradation with reduced volumes of the hippocampus, has an attractive pharmacokinetic profile of rapid on-

amygdala, thalamus, hypothalamus, bed nucleus of stria set and offset, but must be employed with caution for

terminalis, nucleus accumbens, and the descending patients with cardiac and respiratory complications and

projections which synapse at the thoracic spinal cord. when egg and soy allergies are present [40]. Propofol

In addition, shorter telomeres in white blood cells may in combination with benzodiazepines such as fluraze-

be an unwelcomed consequence [18-23]. Clinicians also pam facilitates GABA receptor activity and increases the

see worried patients and family members that come apparent GABAA receptor complex affinity for propo-

to clinic with questions about post-operative cognitive

fol, resulting in a synergistic potentiation by the com-

changes, with frequent complaints of, “I’m worried, I

bination [41]. A case control study demonstrated that

can’t remember things that I could before the opera-

both propofol-ketamine (Group I) and propofol-fen-

tion”; or “my memory is not getting better (following

tanyl (Group II) combinations produced rapid, pleasant

surgery)”.

and safe anesthesia. Group I had stable hemodynamics

What do we know about POCD and why is it import- during maintenance phase while Group II recorded a

ant, especially for clinicians treating the elderly? This slight increase in both pulse rate and blood pressure.

commentary is not a tutorial, rather a brief introduction During recovery, ventilation score was better in Group,

to POCD for those readers unfamiliar with the diagnosis, while movement and wakefulness scores were better in

with suggestions for treatment of the memory deficits Group II. The authors concluded that both groups’ anes-

postsurgically. The reader is referred to POCD reviews thesia combinations produce rapid and safe anesthesia

for additional in-depth information [24-27]. with few minor side effects [36].

Anesthesia Blood Brain Barrier

The risk of developing POCD is related to many vari- Aging is often accompanied by changes in blood-

ables including, but not limited to, immune response brain barrier permeability due to chronic inflammatory

to surgery, advanced age, pre-existing cerebral, cardi- processes, a component of POCD pathology. Increasing

ac, and vascular disease, alcohol abuse, low education- blood-brain barrier permeability augments the burden

al level, and intra- and postoperative complications of inflammation, infection and toxins passing into the

[7,13,14,28]. Many randomized controlled studies sug- brain that in turn accelerate degenerative processes

gest the method of anesthesia is also a major variable [42,43], reduce brain reserve [44] and render the brain

associated with prolonged cognitive impairment. There- more susceptible to POCD [45]. Moreover, reduced

fore, one of the first POCD factors investigated was the drug elimination rates contribute to increased episodes

use of volatile gases, such as isoflurane, sevoflurane, of toxic medication effects peripherally [46]. When the

desflurane, nitrous oxide, pentobarbital, midazolam and

toxic medications cross the blood-brain barrier, they es-

ketamine during surgical procedures [29-32]. In vitro

calate the risk of neurodegenerative disorders [34].

and animal studies have demonstrated that inhalational

and intravenous anesthetics are principal components Perioperative considerations

of POCD neuropathology. These anesthetic agents may

Literature regarding the treatment of POCD is pres-

cause neuroapoptosis, caspase activation, neurodegen-

ently limited, in part related to the suspected multifac-

eration, β-amyloid protein (Aβ) accumulation, oligom-

torial pathophysiology. Jildenstål, et al. in 2014 noted

erization and neurocognition impairment [9]. Studies

that anesthesiologists in general have not systemati-

demonstrate that certain volatile anesthetics, such as

cally addressed the reversible and irreversible symp-

desflurane, may have a less harmful neurotoxic profile

toms of POCD in the elderly as they primarily focus on

compared to others in the surgical and clinical settings

minimizing cardiovascular and pulmonary risks and on

[9,12,33,34].

diminishing nausea, vomiting and pain postoperative-

Propofol and other more modern volatile anesthet- ly [10]. A Swedish study sent questionnaires to great-

ics are among the recommended choices for general er than 2500 anesthesiologists and nurse anesthetists.

Detweiler. J Geriatr Med Gerontol 2018, 4:038 • Page 2 of 5 •

DOI: 10.23937/2469-5858/1510038 ISSN: 2469-5858

The survey revealed that postoperative neurocognitive Some clinicians are addressing the complexity of

deficits were not primary outcome indices of anesthe- POCD treatment by utilizing the 36 point ReCODE (re-

sia protocols of the anesthesiologists contacted [10]. versing cognitive decline) protocol which has been

However, anesthesia research regarding perioperative proven to reverse Alzheimer’s disease even for persons

anesthesia sequalae and pain management problems is with two copies of ApoE4 allele. This treatment protocol

ongoing and contributing to an understanding of POCD has been supported by over 200 peer reviewed publica-

pathology [26,36,39,47-51]. Addressing perioperative tions [43]. The ReCODE protocol of Dr. Dale Bredesen

pain management is an important treatment for reduc- and colleagues at the Buck Institute for Research on Ag-

ing the risk of delirium and POCD [49,51]. ing at UCSF address most of the complex issues involved

in precipitating the memory deficits of POCD: Insulin re-

Both pain and the resulting administration of opioids

sistance; inflammation and infections; hormone, nutri-

are notable contributors to delirium and POCD [49,52-

ent and trophic factor optimization; toxins (biological,

55]. Moreover, the elderly have many comorbid med-

chemical, physical); and restoration and protection of

ical conditions, including chronic pain conditions such

damaged synapses [43]. The protocol includes changes

as low back pain, chronic tension-type headaches and

in lifestyle, diet, sleep patterns, and exercise to reverse

fibromyalgia which complicate post-surgery recovery

cognitive decline. Outcomes are measured by cogni-

and return to presurgical cognitive and functional levels

tive scales, homocysteine levels, hippocampal volume

[53,56]. Chronic pain has been associated with changes

changes and other biomedical markers. It is speculated

in global and regional brain morphology and brain vol-

that the ReCODE protocol will provide the treatment

ume loss including structural brain changes in the mid-

advances for POCD in the future.

dle corpus callosum, middle cingulate white matter and

the grey matter of the posterior parietal cortex as well Conclusions

as impaired attention and mental flexibility as measured

POCD is a debilitating surgical sequalae. Understand-

by neuropsychological tests [53,54]. Brain atrophy and

ing its complex physiology and treatment are ongoing

white matter lesions have been shown to be associated

endeavors. Clinicians treating the elderly and infant

with increased risk of delirium which in some cases is

populations need to have a working understanding of

the prodrome to POCD [26,48,54,57]. Studies also sug-

the syndrome in order to treat patients, to educate both

gest that presurgery dementia and post-surgery inten-

the patients and families and to proactively address the

sive care unit admission are more important predictors

symptoms of POCD. In addition to continuing interdis-

of postoperative delirium than are opioid medications

ciplinary research of POCD, more education about this

[55].

clinical entity should be included in the teaching of med-

Anesthesia research is making advances in postsur- ical student, residents and fellows in most specialties.

gical pain management [49,51,52,54]. Minimal incision Moreover, there needs to be more information about

surgery for total hip and total knee arthroplasties with POCD in those journals read by pediatricians, family

closely supervised pain management and physical ther- practitioners, internists and geriatricians to better pre-

apy protocols markedly improved outcome variables pare them when they encounter POCD clinically.

compared to the same interventions with standard inci-

sions [52]. Midwest Orthopedists in Rush surgical teams References

have been advancing protocols to reduce postsurgery 1. Szokol JW (2010) Postoperative cognitive dysfunction. Re-

pain with reduced inpatient hospital narcotic consump- vista Mexicana de Anestesiología 33: S249-S253.

tion, resulting in reduced inpatient nausea, vomiting 2. Anwer HM, Swelem SE, el-Sheshia A, Moustafa AA (2006)

and hospital length of stay [57]. Post-operative cognitive dysfunction in adult and elderly

patrients--general anesthesia vs subarachnoid or epidural

Treatment of POCD analgesia. Middle East J Anaesthesiol 18: 1123-1138.

When the patient comes to the outpatient clinic with 3. Flick RP, Katusic SK, Colligan RC, Wilder RT, Voigt RG, et al.

POCD symptoms, what can be done? The literature gives (2011) Cognitive and behavioral outcomes after early expo-

sure to anesthesia and surgery. Pediatrics 128: e1053-e1061.

clinicians few hints as no protocol or consensus guide-

lines could be found in a literature search. Many clinics 4. Millar K, Bowman AW, Burns D, McLaughlin P, Moores T,

et al. (2014) Children’s cognitive recovery after day-case

go through a differential diagnosis including ongoing general anesthesia: A randomized trial of propofol or isoflu-

postsurgical delirium from comorbid infection, inflam- rane for dental procedures. Paediatr Anaesth 24: 201-207.

mation, metabolic (e.g., Vitamin B12, folate, thyroid

5. Sprung J, Flick RP, Katusic SK, Colligan RC, Barbaresi WJ,

function), medical, psychiatric, pharmacy and substance et al. (2012) Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder after

abuse problems. This replicates the clinical approach of- early exposure to procedures requiring general anesthesia.

ten employed for persons presenting with memory dis- Mayo Clin Proc 87: 120-129.

orders from subjective cognitive impairment (SCI), mild 6. Weiser TG, Regenbogen SE, Thompson KD, Haynes AB,

cognitive impairment (MCI) and the dementias (Alzhei- Lipsitz SR, et al. (2008) An estimation of the global volume

mer’s disease, vascular dementia, Lewy Body dementia, of surgery: A modelling strategy based on available data.

Lancet 372: 139-144.

Parkinson’s Dementia, Frontotemporal dementia, etc.).

Detweiler. J Geriatr Med Gerontol 2018, 4:038 • Page 3 of 5 •

DOI: 10.23937/2469-5858/1510038 ISSN: 2469-5858

7. Monk TG, Weldon BC, Garvan CW, Dede DE, van der Aa 26. Silverstein JH (2014) Cognition, anesthesia, and surgery.

MT, et al. (2008) Predictors of cognitive dysfunction after Int Anesthesiol Clin 52: 42-57.

major noncardiac surgery. Anesthesiology 108: 18-30.

27. Khalil S, Roussel J, Schubert A, Emory L (2015) Postop-

8. Ancelin ML, De Roquefeuil G, Scali J, Bonnel F, Adam JF, erative cognitive dysfunction: An updated review. J Neurol

et al. (2010) Long-term post-operative cognitive decline in the Neurophysiol 6: 290.

elderly: The effects of anesthesia type, apolipoprotein E geno-

28. Grape S, Ravussin P, Rossi A, Kern C, Steiner LA (2012)

type, and clinical antecedents. J Alzheimers Dis 22: 105-113.

Postoperative cognitive dysfunction. Trends in Anaesthesia

9. Vlisides P, Xie Z (2012) Neurotoxicity of general anesthet- and Critical Care 2: 98-103.

ics: An update. Curr Pharm Des 18: 6232-6240.

29. Nishikawa K, Harrison NL (2003) The actions of sevoflu-

10. Jildenstål P, Rawal N, Hallén J, Berggren L, Jakobsson rane and desflurane on the gamma-aminobutyric acid re-

JG (2014) Postoperative management in order to minimise ceptor type A: Effects of TM2 mutations in the alpha and

postoperative delirium and postoperative cognitive dys- beta subunits. Anesthesiology 99: 678-684.

function: Results from a Swedish web-based survey. Ann

30. Sato Y, Kobayashi E, Murayama T, Mishina M, Seo N

Med Surg (Lond) 3: 100-107.

(2005) Effect of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor epsilon1

11. Zuo Z (2012) Are volatile anesthetics neuroprotective or subunit gene disruption of the action of general anesthetic

neurotoxic? Med Gas Res 2: 10. drugs in mice. Anesthesiology 102: 557-561.

12. Rasmussen LS, Steinmetz J (2015) Ambulatory anaesthe- 31. Bianchi SL, Tran T, Liu C, Lin S, Li Y, et al. (2008) Brain

sia and cognitive dysfunction. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 28: and behavior changes in 12-month-old Tg2576 and non-

631-635. transgenic mice exposed to anesthetics. Neurobiol Aging

29: 1002-1010.

13. Androsova G, Krause R, Winterer G, Schneider R (2015)

Biomarkers of postoperative delirium and cognitive dys- 32. Lin D, Zuo Z (2011) Isoflurane induces hippocampal cell

function. Front Aging Neurosci 7: 112. injury and cognitive impairments in adult rats. Neurophar-

macology 61: 1354-1359.

14. Strøm C, Rasmussen LS, Steinmetz J (2016) Practical

management of anaesthesia in the elderly. Drugs Aging 33: 33. Wise-Faberowski L, Raizada MK, Sumners C (2003) Des-

765-777. flurane and sevoflurane attenuate oxygen and glucose

deprivation-induced neuronal cell death. J Neurosurg An-

15. Strub RL (2003) Vascular dementia. Ochsner J 5: 40-43.

esthesiol 15: 193-199.

16. Yee MK, Janulewicz PA, Seichepine DR, Sullivan KA,

34. Montagne A, Barnes SR, Sweeney MD, Halliday MR,

Proctor SP, et al. (2017) Multiple mild traumatic brain in-

Sagare AP, et al. (2015) Blood-Brain barrier breakdown in

juries are associated with increased rates of health symp-

the aging human hippocampus. Neuron 85: 296-302.

toms and gulf war illness in a cohort of 1990-1991 gulf war

veterans. Brain Sci 7. 35. Abeles G, Sequeira M, Swensen RD, Bisaccia E, Scarbor-

ough DA (1999) The combined use of propofol and fentanyl

17. Corrigan PW, Druss BG, Perlick DA (2014) The impact of

for outpatient intravenous conscious sedation. Dermatol

mental illness stigma on seeking and participating in mental

Surg 25: 559-562.

health care. Psychol Sci Public Interest 15: 37-70.

36. Bajwa SJS (2015) Clinical conundrums and challenges

18. Foote SL, Bloom FE, Aston-Jones G (1983) Nucleus locus

during geriatric orthopedic emergency surgeries. Int J Crit

ceruleus: New evidence of anatomical and physiological

Illn Inj Sci 5: 38-45.

specificity. Physiol Rev 63: 844-914.

37. Osman ES, Khafagy HF, Samhan YM, Hassan MM,

19. Walker DL, Toufexis TJ, Davis M (2003) Role of the bed

El-Shanawany FM, et al. (2012) In vivo effects of different

nucleus of the stria terminalis versus the amygdala in fear,

anesthetic agents on apoptosis. Korean J Anesthesiol 63:

stress, and anxiety. Eur J Pharmacol 463: 199-216.

18-24.

20. Bremner JD (2006) Stress and brain atrophy. CNS Neurol

38. Davis N, Lee M, Lin AY, Lynch L, Monteleone M, et al.

Disord Drug Targets 5: 503-512.

(2014) Post-operative cognitive function following general

21. (2011) Depression and chronic stress accelerates aging. versus regional anesthesia: A systematic review. J Neuro-

Umeå University. surg Anesthesiol 26: 369-376.

22. Wikgren M, Maripuu M, Karlsson T, Nordfjäll K, Bergdahl J, 39. Valentim AM, Félix LM, Carvalho L, Diniz E, Antunes LM

et al. (2012) Short telomeres in depression and the gener- (2016) A new anaesthetic protocol for adult zebrafish (Da-

al population are associated with a hypocortisolemic state. nio rerio): Propofol combined with lidocaine. PLoS One 11:

Biol Psychiatry 71: 294-300. e0147747.

23. Kang HJ, Voleti B, Hajszan T, Rajkowska G, Stockmeier 40. Saraghi M, Badner VM, Golden LR, Hersh EV (2013)

CA, et al. (2012) Decreased expression of synapse-related Propofol: An overview of its risks and benefits. Compend

genes and loss of synapses in major depressive disorder. Contin Educ Dent 34: 252-258.

Nat Med 18: 1413-1417.

41. Reynolds JN, Maitra R (1996) Propofol and flurazepam act

24. Mason SE, Noel-Storr A, Ritchie CW (2010) The impact synergistically to potentiate GABAA receptor activation in

of general and regional anesthesia on the incidence of human recombinant receptors. Eur J Pharmacol 314: 151-

post-operative cognitive dysfunction and post-operative 156.

delirium: A systematic review with meta-analysis. J Alzhei-

42. Bredesen DE, Rao RV (2017) Ayurvedic profiling of Alzhei-

mers Dis 22: 67-79.

mer’s disease. Altern Ther Health Med 23: 46-50.

25. Van Harten AE, Scheeren TW, Absolom AR (2012) A re-

43. Bredesen DE, Amos EC, Canick J, Ackerley JM, Raji C,

view of postoperative cognitive dysfunction and neuroin-

et al. (2016) Reversal of cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s

flammation associated with cardiac surgery and anaesthe-

disease. Aging (Albany NY) 8: 1250-1258.

sia. Anaesthesia 67: 280-293.

Detweiler. J Geriatr Med Gerontol 2018, 4:038 • Page 4 of 5 •

DOI: 10.23937/2469-5858/1510038 ISSN: 2469-5858

44. Stern Y (2002) What is cognitive reserve? Theory and re- ent opioids: A systematic review. Drugs Aging 34: 437-443.

search application of the reserve concept. J Int Neuropsy-

52. Nuelle DG, Mann K (2007) Minimal incision protocols for

chol Soc 8: 448-460.

anesthesia, pain management, and physical therapy with

45. Rosenberg GA (2014) Blood-Brain barrier permeability in standard incisions in hip and knee arthroplasties: The effect

aging and Alzheimer’s disease. J Prev Alzheimers Dis 1: on early outcomes. J Arthroplasty 22: 20-25.

138-139.

53. Schmidt-Wilcke T (2008) Variations in brain volume and

46. Kinirons MT, O’Mahony MS (2004) Drug metabolism and regional morphology associated with chronic pain. Curr

ageing. Br J Clin Pharmacol 57: 540-544. Rheumatol Rep 10: 467-474.

47. Bruhn J, Myles PS, Sneyd R, Struys MM (2006) Depth of 54. Buckalew N, Haut MW, Morrow L, Weiner D (2008) Chronic

anaesthesia monitoring: What’s available, what’s validated pain is associated with brain volume loss in older adults:

and what’s next? Br J Anaesth 97: 85-94. Preliminary evidence. Pain Med 9: 240-248.

48. Bryson GL, Wyand A (2006) Evidence-based clinical up- 55. Sieber FE, Mears S, Lee H, Gottschalk A (2011) Postop-

date: General anesthesia and the risk of delirium and post- erative opioid consumption and its relationship to cognitive

operative cognitive dysfunction. Can J Anesth 53: 669-677. function in older adults with hip fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc

59: 2256-2262.

49. Wang Y, Sands LP, Vaurio L, Mullen EA, Leung JM (2007)

The effects of postoperative pain and its management on 56. Newman N, Stygall J, Hirani S, Shaefi S, Maze M (2007)

postoperative cognitive dysfunction. Am J Geriatr Psychi- Postoperative cognitive dysfunction after noncardiac sur-

atry 15: 50-59. gery: A systematic review. Anesthesiology 106: 572-590.

50. Tsai TL, Sands LP, Leung JM (2010) An update on post- 57. (2017) New postoperative spine anesthesia protocol reduc-

operative cognitive dysfunction. Adv Anesth 28: 269-284. ing the need for post-surgical narcotics. Midwest Orthopae-

dics at Rush.

51. Swart LM, van der Zanden V, Spies PE, Rooij SE, van Mun-

ster BC (2017) The comparative risk of delirium with differ-

Detweiler. J Geriatr Med Gerontol 2018, 4:038 • Page 5 of 5 •

You might also like

- Lippincott 39 S Anesthesia Review 1001 Questions A PDFDocument429 pagesLippincott 39 S Anesthesia Review 1001 Questions A PDFPeter Kazarin50% (2)

- Neurocritical Care Management of The Neurosurgical Patient (PDFDrive)Document510 pagesNeurocritical Care Management of The Neurosurgical Patient (PDFDrive)Chanatthee KitsiripantNo ratings yet

- Methergine Drug StudyDocument3 pagesMethergine Drug StudyQueenie Puzon80% (5)

- Tulio E. Bertorini - Neuromuscular DisordersDocument466 pagesTulio E. Bertorini - Neuromuscular DisordersLeila Gonzalez100% (1)

- Propofol SynthesisDocument8 pagesPropofol SynthesisGiorgos Doukas Karanasios0% (1)

- LIBRO NEURO UCI 2013 Monitoring in Neurocritical CareDocument602 pagesLIBRO NEURO UCI 2013 Monitoring in Neurocritical CareDiana Reaño RuizNo ratings yet

- C+F-Restraint Methoda For Radiography in Dogs and CatsDocument13 pagesC+F-Restraint Methoda For Radiography in Dogs and Catstaner_soysurenNo ratings yet

- Search Warrants: Re: Dr. Conrad Murray Manslaughter ChargesDocument47 pagesSearch Warrants: Re: Dr. Conrad Murray Manslaughter ChargesBetsy A. RossNo ratings yet

- DeliriumDocument15 pagesDeliriumRobin gruNo ratings yet

- Clinical Patterns and Biological Correlates of Cognitive Dysfunction Associated To Cancer TreatmentDocument12 pagesClinical Patterns and Biological Correlates of Cognitive Dysfunction Associated To Cancer TreatmentRodolfo BenavidesNo ratings yet

- Neurological Complications of Surgery and AnaesthesiaDocument14 pagesNeurological Complications of Surgery and Anaesthesiarian rantungNo ratings yet

- Preoperative Assessment of The Older Patient: C.L. Pang, M. Gooneratne and J.S.L. PartridgeDocument7 pagesPreoperative Assessment of The Older Patient: C.L. Pang, M. Gooneratne and J.S.L. Partridgealejandro montesNo ratings yet

- A Clinical Update On Delirium: From Early Recognition To Effective ManagementDocument13 pagesA Clinical Update On Delirium: From Early Recognition To Effective ManagementNabila MarsaNo ratings yet

- Postoperative Cognitive Dysfunction and Dementia: What We Need To Know and DoDocument11 pagesPostoperative Cognitive Dysfunction and Dementia: What We Need To Know and Dofulgentius juliNo ratings yet

- Psychiatric Outcomes After Temporal Lobe Surgery in Patients With Temporal Lobe Epilepsy and Comorbid Psychiatric IllnessDocument8 pagesPsychiatric Outcomes After Temporal Lobe Surgery in Patients With Temporal Lobe Epilepsy and Comorbid Psychiatric IllnessFrancisco Javier Fierro RestrepoNo ratings yet

- Bench-To-Bedside Review - Brain Dysfunction in Critically Ill Patients - The Intensive Care Unit and BeyondDocument9 pagesBench-To-Bedside Review - Brain Dysfunction in Critically Ill Patients - The Intensive Care Unit and Beyondthomas.szapiroNo ratings yet

- Frara 2020Document12 pagesFrara 2020anocitora123456789No ratings yet

- Evaluation of The Efficacy of Fascia Iliaca Compartment Block in Maintaining Cognitive Function Post-Surgery in Elderly Individuals With Hip FracturesDocument12 pagesEvaluation of The Efficacy of Fascia Iliaca Compartment Block in Maintaining Cognitive Function Post-Surgery in Elderly Individuals With Hip FracturesInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Markers & RX of Brain Dysfunction. Crit CareDocument9 pagesMarkers & RX of Brain Dysfunction. Crit CareParvathy R NairNo ratings yet

- Jama Vacas 2021 It 210019 1630095346.97965Document2 pagesJama Vacas 2021 It 210019 1630095346.97965Juan Carlos Perez ParadaNo ratings yet

- Sedation, Delirium, and Cognitive Function After Criticall IlnessDocument14 pagesSedation, Delirium, and Cognitive Function After Criticall IlnessPsiquiatría CESAMENo ratings yet

- Cesarean Section in Post-Polio PatientDocument2 pagesCesarean Section in Post-Polio PatientasclepiuspdfsNo ratings yet

- Ancelin 2010Document9 pagesAncelin 2010chuckNo ratings yet

- 2006, Vol.24, Issues 1, Brain Injury and Cardiac ArrestDocument169 pages2006, Vol.24, Issues 1, Brain Injury and Cardiac ArrestKishore Reddy BhavanamNo ratings yet

- Kluger 2019Document3 pagesKluger 2019Ana LopezNo ratings yet

- Critical Care Issues of TheDocument11 pagesCritical Care Issues of TheJEFFERSON MUÑOZNo ratings yet

- Critical Care Issues of TheDocument11 pagesCritical Care Issues of TheJEFFERSON MUÑOZNo ratings yet

- PsychologyDocument7 pagesPsychologyHarish KumarNo ratings yet

- Medico Legal Aspects of Severe Traumatic Brain InjuryDocument17 pagesMedico Legal Aspects of Severe Traumatic Brain InjuryIrv CantorNo ratings yet

- Final Draft-Long-Term Cognitive ImpairmentDocument6 pagesFinal Draft-Long-Term Cognitive Impairmentapi-237094717No ratings yet

- Delirium in The Intensive Care UnitDocument9 pagesDelirium in The Intensive Care Uniton miniNo ratings yet

- Contoh Case StudyDocument11 pagesContoh Case StudyNovitaSariNo ratings yet

- 2018 Imp Roving Long - Te RM Outcomes After SepsisDocument14 pages2018 Imp Roving Long - Te RM Outcomes After SepsisgiseladlrNo ratings yet

- Cardiac Surgery, The Brain, and Inflammation: Expert ReviewsDocument8 pagesCardiac Surgery, The Brain, and Inflammation: Expert ReviewsArif Susilo RahadiNo ratings yet

- A Síndrome de Cuidados Pós-Neurointensivos É Realmente Uma CoisaDocument2 pagesA Síndrome de Cuidados Pós-Neurointensivos É Realmente Uma CoisaMaiquiel MaiaNo ratings yet

- 2019 Article 903Document12 pages2019 Article 903ArolNo ratings yet

- PrintArticle 72003Document7 pagesPrintArticle 72003Sadhi RashydNo ratings yet

- Neuro in The ICUDocument4 pagesNeuro in The ICUEduardo GarciaNo ratings yet

- An Update On Cancer-And Chemotherapy - Related Cognitive Dysfunction: Current StatusDocument8 pagesAn Update On Cancer-And Chemotherapy - Related Cognitive Dysfunction: Current StatusgorklanNo ratings yet

- GMHAT - Cardiac Patients Reino UnidoDocument7 pagesGMHAT - Cardiac Patients Reino UnidoIleana AjaNo ratings yet

- Palliative Care and End-Of-Life Care in Adults With Malignant Brain TumorsDocument10 pagesPalliative Care and End-Of-Life Care in Adults With Malignant Brain TumorsLaras Adythia PratiwiNo ratings yet

- Comp Il CationDocument8 pagesComp Il CationWahyu Permata LisaNo ratings yet

- Chemotherapy Related Cog. Dysf.Document9 pagesChemotherapy Related Cog. Dysf.Manuel Guerrero GómezNo ratings yet

- 2012 Rehabilitation of Brachial Plexus Injuries in Adults and ChildrenDocument24 pages2012 Rehabilitation of Brachial Plexus Injuries in Adults and ChildrenchayankkuNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Impairment in Patients With End-Stage Renal Disease: Accelerated Brain Aging?Document9 pagesCognitive Impairment in Patients With End-Stage Renal Disease: Accelerated Brain Aging?Debora BergerNo ratings yet

- 4-Treatment of Advanced Parkinson Ds - Continuum (2016)Document13 pages4-Treatment of Advanced Parkinson Ds - Continuum (2016)bernarduswidodoNo ratings yet

- Anna PIECZYŃSKA 2022Document9 pagesAnna PIECZYŃSKA 2022PPDS Rehab Medik UnhasNo ratings yet

- A. Discussion of The Health ConditionDocument5 pagesA. Discussion of The Health ConditionPeter AbellNo ratings yet

- Inouye 15 JacsDocument48 pagesInouye 15 JacsPsiquiatría CESAMENo ratings yet

- Pocd 2Document21 pagesPocd 2fulgentius juliNo ratings yet

- Psychosurgery, Epilepsy Surgery, or Surgical Psychiatry: The Tangled Web of Epilepsy and Psychiatry As Revealed by Surgical OutcomesDocument2 pagesPsychosurgery, Epilepsy Surgery, or Surgical Psychiatry: The Tangled Web of Epilepsy and Psychiatry As Revealed by Surgical Outcomesximena sanchezNo ratings yet

- Management of Traumatic Brain Injury PatientsDocument14 pagesManagement of Traumatic Brain Injury Patientsyayaslaras96No ratings yet

- A Missing Piece? Neuropsychiatric Functioning in Untreated Patients With Tumors Within The Cerebellopontine AngleDocument9 pagesA Missing Piece? Neuropsychiatric Functioning in Untreated Patients With Tumors Within The Cerebellopontine AnglejuandellibroNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Cognitive Rehabilitation On Memory Outcome After Temporal Lobe Epilepsy SurgeryDocument8 pagesThe Effects of Cognitive Rehabilitation On Memory Outcome After Temporal Lobe Epilepsy SurgeryLaura Arbelaez ArcilaNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Brain InjuryDocument8 pagesLiterature Review Brain Injuryafdtwudac100% (1)

- Medi 97 E10919Document4 pagesMedi 97 E10919oktaviaNo ratings yet

- Delirium in The Intensive Care Unit: ReviewDocument9 pagesDelirium in The Intensive Care Unit: ReviewCristopher Castro RdNo ratings yet

- Dafang Wu - Clinical Nuclear Medicine Neuroimaging - An Instructional Casebook-Springer (2020)Document394 pagesDafang Wu - Clinical Nuclear Medicine Neuroimaging - An Instructional Casebook-Springer (2020)newhopeclub03reeceNo ratings yet

- Delirium After Deep Brain Stimulation in Parkinson's DiseaseDocument10 pagesDelirium After Deep Brain Stimulation in Parkinson's DiseaseMikeVDCNo ratings yet

- Palliative Care For Neurologically Injured Patients: Why and How?Document8 pagesPalliative Care For Neurologically Injured Patients: Why and How?jumabarrientosNo ratings yet

- Stroke in Terminal Illness Patients: ANDIKA FAHRIAN (J210184101) NAMAYANJA SUMAYIYAH (J210184205)Document15 pagesStroke in Terminal Illness Patients: ANDIKA FAHRIAN (J210184101) NAMAYANJA SUMAYIYAH (J210184205)Namayanja SumayiyahNo ratings yet

- Whittaker Et Al-2022-Scientific ReportsDocument22 pagesWhittaker Et Al-2022-Scientific ReportsAlex WhittakerNo ratings yet

- Neuro-Oncology Practice: Integration of Palliative Care Into The Neuro-Oncology Practice: Patterns in The United StatesDocument5 pagesNeuro-Oncology Practice: Integration of Palliative Care Into The Neuro-Oncology Practice: Patterns in The United StatessiscaNo ratings yet

- Greene 2019 NeurologicDocument18 pagesGreene 2019 NeurologicangelNo ratings yet

- Rapid Sequence Intubation (RSI) Outside of The Operating Room in Children: Medications For Sedation and ParalysisDocument20 pagesRapid Sequence Intubation (RSI) Outside of The Operating Room in Children: Medications For Sedation and ParalysisLORENA ALEJANDRA RUIZ ARDILANo ratings yet

- Therapeutic IndexDocument8 pagesTherapeutic IndexMary Jennel RosNo ratings yet

- Teknik Anestesi UmumDocument128 pagesTeknik Anestesi UmumRiezka HanafiahNo ratings yet

- Drugs at ORDocument16 pagesDrugs at ORAngelo MangibinNo ratings yet

- Types of AnesthesiaDocument27 pagesTypes of Anesthesiasncmanguiat.2202276.chasnNo ratings yet

- Air Medical Journal: David J. Dries, MSE, MDDocument4 pagesAir Medical Journal: David J. Dries, MSE, MDKat E. KimNo ratings yet

- Should Norepinephrine, Rather Than PhenylephrineDocument8 pagesShould Norepinephrine, Rather Than PhenylephrineDiego Andres Rojas TejadaNo ratings yet

- Induction Drugs Used in Anaesthesia - Update 24 2 2008Document5 pagesInduction Drugs Used in Anaesthesia - Update 24 2 2008Alisya NadhilahNo ratings yet

- AnesthesiaDocument10 pagesAnesthesiaMohamed EssamNo ratings yet

- Tintinalli - Chapter 37 Procedural Sedation and Analgesia in AdultsDocument11 pagesTintinalli - Chapter 37 Procedural Sedation and Analgesia in AdultsPgmee KimsNo ratings yet

- Multiple Choice Questions: Childhood Obesity and The AnaesthetistDocument5 pagesMultiple Choice Questions: Childhood Obesity and The AnaesthetistTanishka GargNo ratings yet

- Pocket Anesthesia Pocket Notseries 3Rd Edition PDF Full Chapter PDFDocument53 pagesPocket Anesthesia Pocket Notseries 3Rd Edition PDF Full Chapter PDFheemstgarrow100% (4)

- Anesthesia For Pancreatic DiseaseDocument4 pagesAnesthesia For Pancreatic DiseaseAuan SurapaNo ratings yet

- BenzodiazepinesDocument35 pagesBenzodiazepinesanaeshklNo ratings yet

- Sedation in The Intensive Care Unit: Katherine Rowe MBCHB MRCP Frca Simon Fletcher Mbbs Frca FrcpeDocument6 pagesSedation in The Intensive Care Unit: Katherine Rowe MBCHB MRCP Frca Simon Fletcher Mbbs Frca FrcpeMohammed IrfanNo ratings yet

- Anesthesia of The Equine Neonate in Health and DiseaseDocument19 pagesAnesthesia of The Equine Neonate in Health and DiseaseIsabel VergaraNo ratings yet

- Anesthetic Management of Geriatric Patients: Review ArticleDocument22 pagesAnesthetic Management of Geriatric Patients: Review Articleagita kartika sariNo ratings yet

- Tiva en NiñosDocument22 pagesTiva en NiñosAndre EstupiñanNo ratings yet

- GENERAL ANESTHETICS PDF Document With Practice QuestionsDocument30 pagesGENERAL ANESTHETICS PDF Document With Practice QuestionsFlowerNo ratings yet

- Calculations Master Class 2020Document52 pagesCalculations Master Class 2020Esraa AbdelfattahNo ratings yet

- GA (General Anestesi)Document7 pagesGA (General Anestesi)salfany try nNo ratings yet

- Preanaesthetic Medication Anaesthetic AgentsDocument35 pagesPreanaesthetic Medication Anaesthetic AgentsSubhash BeraNo ratings yet

- Management of Sedation and Delirium in Ventilated ICU PatientsDocument35 pagesManagement of Sedation and Delirium in Ventilated ICU PatientsJheng-Dao YangNo ratings yet

- Anesthesia in Birds and Exotic Pet Animals: Ganga Prasad Yadav M.V.Sc. Veterinary Surgery & RadiologyDocument54 pagesAnesthesia in Birds and Exotic Pet Animals: Ganga Prasad Yadav M.V.Sc. Veterinary Surgery & RadiologygangaNo ratings yet

- Drug StudyDocument9 pagesDrug StudyVicenia BalloganNo ratings yet