Professional Documents

Culture Documents

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

14 viewsThe Fast of The Apostles in The Early CH

The Fast of The Apostles in The Early CH

Uploaded by

Qaramah MihailCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5825)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Deny Senko 2007Document25 pagesDeny Senko 2007Qaramah MihailNo ratings yet

- Avva Kumo VD As RitualDocument12 pagesAvva Kumo VD As RitualQaramah MihailNo ratings yet

- Liturgy at The Great Lavra of St. SabasDocument30 pagesLiturgy at The Great Lavra of St. SabasQaramah MihailNo ratings yet

- The Reserved Sacrament: Nursing Homes, Institutions, Hospitals or at Home. (See P. 115)Document4 pagesThe Reserved Sacrament: Nursing Homes, Institutions, Hospitals or at Home. (See P. 115)Qaramah MihailNo ratings yet

- Some Central Yet Contested Ideas of LituDocument8 pagesSome Central Yet Contested Ideas of LituQaramah MihailNo ratings yet

- Gendering The Baby in Byzantine Prayers On Child-BedDocument6 pagesGendering The Baby in Byzantine Prayers On Child-BedQaramah MihailNo ratings yet

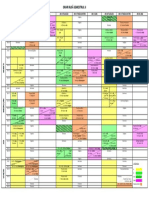

- 15 19 42 12orar Rusa Sem IIDocument1 page15 19 42 12orar Rusa Sem IIQaramah MihailNo ratings yet

- 2Document311 pages2Qaramah MihailNo ratings yet

The Fast of The Apostles in The Early CH

The Fast of The Apostles in The Early CH

Uploaded by

Qaramah Mihail0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

14 views20 pagesOriginal Title

The Fast of the Apostles in the Early Ch

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

14 views20 pagesThe Fast of The Apostles in The Early CH

The Fast of The Apostles in The Early CH

Uploaded by

Qaramah MihailCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

You are on page 1of 20

Maged S. A. Mikhail”

The Fast of the Apostles in the Early Church

and in Later Syrian and Coptic Practice

Abstract

‘The Fast of the Apostles is a post-Pentecost rogation that may span three to forty-nine days. Cur-

rent scholarship places its developed in Rome by the mid-fifth century. This study argues that most

of the alleged evidence has been read out of context or in later recensions, and that scholars have

failed to discern between the Fast of the Apostles proper and short heterogeneous fasts that are

‘marginally attested in the patristic era. It then traces the earliest incontrovertible evidence for this

fast, and charts its development among the West and East Syrians and the Copts of Egypt.

The Fast of the Apostles (or Disciples) is a post-Pentecost rogation that is associa-

ted with the Apostles and their mission (see Mt 28:18-20). It was once observed

from Central Asia to Constantinople, and in a less developed form, all over the

west. The fast remains prominent among several eastern Christian confessions,

where, bereft of uniformity (historically and today), it may span anywhere from

three to forty-nine days. Often, the fast concluded on the Feast of Saints Peter and

Paul (12 July; 29 June, Julian),! a celebration that gained prominence in the East

only after 500 CE.”

This often lengthy and historically pervasive fast has attracted scant scholarly

attention, though it has influenced the interpretation of biblical, apocryphal, and

* Lam grateful to Prof. Dr. Dr. Hubert Kaughold for sharing the references in notes 46 and 47 with

‘me, [am also thankful to the St. Shenouda the Archimandrite Coptic Society (Los Angeles) and

its President, Mr. Hany Takla, for providing me with a digital copy of BN Copte 130 (2), fols 32

31,

1 In Rome, the date commemorated the translation of the relics of the two saints to the catacombs

in the midst of the Decian persecution, but in other regions of the empire the date commemo-

rated the martyrdom of both saints. Gregory Dix, Shape of the Liturgy, New Ecltion (London:

Continuum, 2005), 375-6.

‘Theophanes, Chronicle: Theophanis Chronograph, edltrans. C. de Boor, 2 vols, (Leipzig: BG.

‘Teubner, 1883); C, Mango and R. Scott trans., The Chronicle of Theophanes Confessor (Oxtor

(Oxford University Press, 1999), ani $992 (cE 499-500), pg. 220. Festus, a Roman senator, made a

request to Emperor Anastasios “that the commemoration of the holy aposties Peter and Paul

should be celebrated with greater festivity.”

3. The most detailed discussions of this fast are footnote 448 in George E. Gingras, trans., Egeria.

Diary of a Pilgrimage, ACW 38 (New York: Newman Press, 1970); J. Mateos, Lefya-sapra. Essai

interpretation des matines chaldéennes, OCA 156 (Rome: Pont. Inst. orientalium studiorum,

1958), ch. 6; Karl Holl, Gesemmelte Aufdtze zur Kirchengeschichte, vol. 2, Der Osten (Tabin-

‘gen: J.C. B, Mohr, 1928), 177-80; Anton Baumstark, “Das Kirchenjabr in Antiochia zwischen 512

und 518,” Romische Quartalschrift fir christliche Altertumskunde und Kirchengeschichte

(1897), 31-66, at 65. Also see the dated, though stil valuable entries in Joseph Binghvam’s Ancig-

(Orch 982015)

2 Mihail

patristic texts, along with the drafting of canon laws and the formation of liturgi

calendars and rites for every traditional Christian confession. In the east, the fast

also informed the construction of confessional identities, particularly where mul-

tiple Christian factions, who observed the fast differently, shared the same city or

local. Beyond its marginalization, the Fast of the Apostles [FA hereafter] suffers

from an erroneous double-pronged historiography. Positioning it as the “oldest

fast” and the “Fast of the Church,” the various confessions that remain invested in

this rogation have maintained that it was inaugurated by the first generation of

Christians immediately after Pentecost, and they have long rationalized its obser-

vance through a collage of biblical passages. On the other hand, the few scholars

who have addressed this rogation (typically as a tangent or in a footnote) tend to

rely on a few fourth- and fifth-century patristic passages that have been interpre-

ted out of context. This study challenges the normative assumptions surrounding

this fast, and untangles its rather convoluted historiography. It begins by systema-

tically sifting through the early evidence for its observance and then proceeds to

trace its development among Syrians and Copts.

I. Biblical Evidence?

In the normative literature of the pertinent Orthodox confessions, the FA is ratio-

nalized through reference to a handful of biblical passages (e. g. Mt. 9:14-17, Acts

10:10) and a few patristic citations. Nonetheless, while the biblical references

ities of the Christian Church, 2 vols. (Reeves and Turner, 1878; Eugene: Wipf & Stock, 2006),

41191, 1193; William Smith and Samuel Cheetham, eds, Dictionary of Christian Antiquities, 2

vols. (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1875), s.v. “Apostles Festivals and Fast,” 1109-10,

More generally, see Louis Duchesne, Christian Worship: Its Origins and Evolution (London:

SPCK, 1903), 285-9; F. Cabrol, “Jeunes,” DACL 7:Col, 2481-2501, esp. 493-94, 2498; Thoms J

Talley, The Origins of the Liturgical Year, 2 ed (Collegeville: Liturgical Press, 1991), 57~

Paul F. Bradshaw and Maxwell E. Johnson, The Origins of Feasts, Fasts and Seasons in Early

Onrstanty Collegeville: Liturgical Press, 2011), ch. 8; Paul F. Bradshaw, The Search for the

Origins of Christian Worship, 2° ed, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002) 182-3; Martin F.

Connell, “From Easter to Pentecost,” in Passover and Easter: The Symbolic Structuring of Sacred

Seasons ed, P.F. Bradshaw and L. A. Hoffman (Notre Dame: Univesity of Notre Dame Press,

1999), 94-106; Thomas K. Carroll and Thomas Halton, Liturgical Practice inthe Fathers (Dela-

‘ware: Michael Glazier, 1988), 293-320

4 ML 9:14-17/LK.5:33-S6/Mk, 2:18-20, Acts 1:14; 10:10; 122-3; 13:2-3; 1423; 279, 21, The pais

tic glosses commonly cited by scholars are discussed ia section Il, below. See Emmanuel Fritsch,

“Phe Liturgical Year and the Lectionary ofthe Ethiopian Church: Introduction tothe Temporal,”

Warseawskie Studia Teologicene 122 (1999), 71-116, at 11. These references are ubiquitous in

all Coptic Orthodox literature on the topic. An influential text has been al-Qummus [Hegomen]

‘Yubanna Salimd's a-La’ali” a-nafisa, 2 vols. (Cairo: Maktabat Mart Tis, 1909), 2386-7. Also

sce Kyrills Kyrilus, Apwamand bayn amid wa albagir (Caito: a-Lajnd al-thagatiy® ft al-

anisah, 1982), 78-108; Archbishop Basilos, “Fasting,” Coptic Eneyelopedia 1093-97, at 1093

though these discussions are fraught with historical inaccuracies. The Armenian Orthodox essen

tially observed the same fasting period but ina different context: S. H. Tagizade, “The Iranian

Fast ofthe Apostles in the Early Church and in Later Syrian and Coptic Practice 3

cited demonstrate the importance of fasting and prayer to the carly Christian

community, they fail to demonstrate the existence of a specific post-Pentecost

rogation. At best, the often-quoted Matthew 9:15, “The days will come when the

bridegroom is taken away from,them, and then they will fast” (NRSV), advocates

fasting but does not promote a specific fasting season, and it was in that general

sense that most fourth- and fifth-century authors interpreted the verse.*

On occasion, Latin patristic writings and medieval Coptic Arabic literature

retained a variant reading of Acts 1:14 that sought to legitimize heterogeneous

observances in those regions.” In both, after the Ascension, the followers of Jesus

are said to have gathered secretly, “constantly devoting themselves to prayer and

fasting.” As discussed in the following section, a few bishops in the west pressed

this variant to promote a fast that was introduced after the feast of the Ascension,

though that practice failed to gain acceptance. In Egypt, however, where that rea-

ding is only attested in medieval literature, the application of that variant tradition

consistently strikes a dissonant note. There, in every case encountered, the aug-

mented verse—which describes the activities of the disciples between Ascension

and Pentecost—is quoted to justify a post-Pentecost rogation (the FA); signifi-

cantly, the Egyptian church consistently maintained the integrity of the fifty days

Festivals Adopted by the Christians and Condemned by the Jews,” Bulletin of the School of Ori-

ental and African Studies W03 (1940), 632-653; especially pgs. 644-47.

5 E.g. John Chrysostom, Commentary on Matthew, Sermon 30; F. Field, Joannis Chrysastomi

homiliae in Matthacum, vol. 1 (Cambridge: In Oficina Academica, 1838-39), 422-23; NPNF

1.10: 201-2; Cyril of Alexandria, Commentary on the Gospel of Luke, Sermon 21: J.B. Chabot,

‘S. Oprilli Alexandrini Commentarii in Lucam, CSCO 70 (Patis: E Typographeo Reipublicae,

41012); Latin translation by R.M. Tonneau in CSCO 140 (Louvain, 1953); R, Payne-Smith,

A Commentary upon the Gospel According to S. Luke by Cyril, Patriarch of Alexandria, 2 vols.

(Oxford Oxford University Press, 1859),

6 The addition “and fasting” is lacking in all biblical critical editions surveyed; NA 28, Horner's edi-

‘ions of the New Testament in the Sahidic and Bohairic dialects, along with the Latin and Ethio-

pic versions of Acts. For a critical Ethiopic edition of Acts, see Larry C. Niccum, “The Book of

‘Acts in Ethiopic (with critical text and apparatus) and its Relation to the Greek Textual Tradi-

tion” (Ph. D, Dissertation, Notre Dame, 2000). Tam thankful to Mr. Mazein Krawezuk for sharing,

his reading of the pertinent Ethiopic verses and their critical apparatus with me, For the Coptic,

see George W. Horner, The Coptic Version of the New Testament in the Southern Dialect, vol. 6

(Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1911); idem, The Coptic Version of the New Testament in the North-

ern Dialect, vol. 4 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1905).

7 Imhis Book on Various Heresies, Bishop Filastrius of Brescia (d. 390 CE) quotes the variant as

though it were scripture: V. Bulhart er al, eds, Opera quae supersunt: Diversarum hereseon

liber, CCSL 9 (Turnhout: Brepols, 1957), § 149, p. 312: iefuniis et orationibus insistemtes: The

gloss is frequent in the Arabic literature of the Copts, e.g. Kyrillus, Aswamand, 79, 85. While

prayer and fasting are often linked in the New Testament (c.g. Acts 13:3 and 14:23), singular ref-

erences to “prayer” are frequently rendered “fasting and prayer” in later manuscripts; cf. the

manuscript tradition for Mk. 9:29 and 1 Cor. 7:5.

8 T.J. Talley, Origins, 62, 66-67; P.F. Bradshaw, Search for the Origins, 183; P.F. Bradshaw and

M.E, Johnson, Origins of Feasts, 72; MF. Connell, “From Easter to Pentecost,” 99-101. In some

cases, the fast was from Ascension to Pentecost, at others it was simply the resomption of the

‘Wednesday/Friday observance during those ten days.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5825)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Deny Senko 2007Document25 pagesDeny Senko 2007Qaramah MihailNo ratings yet

- Avva Kumo VD As RitualDocument12 pagesAvva Kumo VD As RitualQaramah MihailNo ratings yet

- Liturgy at The Great Lavra of St. SabasDocument30 pagesLiturgy at The Great Lavra of St. SabasQaramah MihailNo ratings yet

- The Reserved Sacrament: Nursing Homes, Institutions, Hospitals or at Home. (See P. 115)Document4 pagesThe Reserved Sacrament: Nursing Homes, Institutions, Hospitals or at Home. (See P. 115)Qaramah MihailNo ratings yet

- Some Central Yet Contested Ideas of LituDocument8 pagesSome Central Yet Contested Ideas of LituQaramah MihailNo ratings yet

- Gendering The Baby in Byzantine Prayers On Child-BedDocument6 pagesGendering The Baby in Byzantine Prayers On Child-BedQaramah MihailNo ratings yet

- 15 19 42 12orar Rusa Sem IIDocument1 page15 19 42 12orar Rusa Sem IIQaramah MihailNo ratings yet

- 2Document311 pages2Qaramah MihailNo ratings yet