Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Barro On The Ricardian Equivalence Theorem

Barro On The Ricardian Equivalence Theorem

Uploaded by

David C. SantaCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Adp Pay Stub TemplateDocument1 pageAdp Pay Stub TemplateJordan McKenna0% (1)

- Pay Slip - 473995 - Mar-22Document1 pagePay Slip - 473995 - Mar-22Siva Ramakrishna0% (1)

- Philippine Public DebtDocument20 pagesPhilippine Public Debtmark genove100% (3)

- UK Vs USA Common Law Vs Common SenceDocument7 pagesUK Vs USA Common Law Vs Common SenceShlomo Isachar Ovadiah100% (1)

- Barro On The Ricardian Equivalence TheoremDocument6 pagesBarro On The Ricardian Equivalence TheoremvalkriyeNo ratings yet

- On The Determination of The Public DebtDocument33 pagesOn The Determination of The Public DebtFederico Castello RojoNo ratings yet

- On The Determination of The Public DebtDocument32 pagesOn The Determination of The Public DebtPablo SantizoNo ratings yet

- T Rident: Municipal ResearchDocument4 pagesT Rident: Municipal Researchapi-245850635No ratings yet

- Can Democracy Prevent Default?: Sebastian M. SaieghDocument22 pagesCan Democracy Prevent Default?: Sebastian M. SaieghMateus RabeloNo ratings yet

- Are Government Bonds Net Wealth? Robert J. BarroDocument23 pagesAre Government Bonds Net Wealth? Robert J. BarroMaksim Los1No ratings yet

- Elgin y Uras 2012 - Public Debt, Sovereign Default Risk and Shadow Economy PAPER BASEDocument13 pagesElgin y Uras 2012 - Public Debt, Sovereign Default Risk and Shadow Economy PAPER BASEpcefanquNo ratings yet

- Calvo, G (1988) - Servicing The Public Debt - The Role of ExpectationsDocument16 pagesCalvo, G (1988) - Servicing The Public Debt - The Role of ExpectationsDaniela SanabriaNo ratings yet

- A Dynamic Theory of Public Spending, Taxation and DebtDocument36 pagesA Dynamic Theory of Public Spending, Taxation and DebtLuis Carlos Calixto RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Are There Spillover Effects From Munis?: Rabah Arezki, Bertrand Candelon and Amadou N. R. SyDocument19 pagesAre There Spillover Effects From Munis?: Rabah Arezki, Bertrand Candelon and Amadou N. R. SyFerdi GunesNo ratings yet

- Debt Afford Ability PaperDocument21 pagesDebt Afford Ability PaperKen KrizNo ratings yet

- Taxes, Money and Public DebtDocument7 pagesTaxes, Money and Public DebtFerhat AkyüzNo ratings yet

- R-G 0: Can We Sleep More Soundly?: by Paolo Mauro and Jing ZhouDocument32 pagesR-G 0: Can We Sleep More Soundly?: by Paolo Mauro and Jing ZhoutegelinskyNo ratings yet

- Why Have States Partly Lost Their Ability To Tax How Have Governments Been Compensating For Their Fiscal Faults Discuss The Fi 1587138428Document10 pagesWhy Have States Partly Lost Their Ability To Tax How Have Governments Been Compensating For Their Fiscal Faults Discuss The Fi 1587138428AdamNo ratings yet

- BIS Working PapersDocument40 pagesBIS Working PapersAdminAliNo ratings yet

- Financial Accelerator: Economic Activity Can Further Exacerbate The Financial DownturnDocument30 pagesFinancial Accelerator: Economic Activity Can Further Exacerbate The Financial DownturnSasraNo ratings yet

- Restructuring A Sovereign Debtor's Contingent LiabilitiesDocument10 pagesRestructuring A Sovereign Debtor's Contingent Liabilitiesvidovdan9852No ratings yet

- Unit 13Document14 pagesUnit 13Lekhutla TFNo ratings yet

- A Framework For Debt Relief Cum Adjustment Packages 010523Document19 pagesA Framework For Debt Relief Cum Adjustment Packages 010523MANI SNo ratings yet

- R Gov Bonds Net WealthDocument24 pagesR Gov Bonds Net WealthNabil LahhamNo ratings yet

- Meaning:: Public Debt: Meaning, Objectives and Problems!Document5 pagesMeaning:: Public Debt: Meaning, Objectives and Problems!document singhNo ratings yet

- Ifdp 1104Document36 pagesIfdp 1104TBP_Think_TankNo ratings yet

- The Level and Composition of Public Sector Debt in Emerging Market CrisesDocument35 pagesThe Level and Composition of Public Sector Debt in Emerging Market CrisesTBP_Think_TankNo ratings yet

- Bargained Haircuts and Debt Policy Implications: Aloisio Araujo, Marcia Leon and Rafael SantosDocument28 pagesBargained Haircuts and Debt Policy Implications: Aloisio Araujo, Marcia Leon and Rafael SantosFrancisco IsidroNo ratings yet

- Debt Overhang and Recapitalization in Closed and Open EconomiesDocument30 pagesDebt Overhang and Recapitalization in Closed and Open EconomiesPeNo ratings yet

- Calvo Deuda PublicaDocument16 pagesCalvo Deuda PublicaMartin ArrutiNo ratings yet

- Looking Behind The Aggregates: A Reply To "Facts and Myths About The Financial Crisis of 2008"Document18 pagesLooking Behind The Aggregates: A Reply To "Facts and Myths About The Financial Crisis of 2008"StonerNo ratings yet

- Letelier - Municipal Borrowing in Chile (2011)Document17 pagesLetelier - Municipal Borrowing in Chile (2011)rosoriofNo ratings yet

- Problem of Internal Debt and External DebtDocument6 pagesProblem of Internal Debt and External DebtFAISAL KHANNo ratings yet

- Bank Clerks' Exam: EnglishDocument8 pagesBank Clerks' Exam: Englishਰਾਹ ਗੀਰNo ratings yet

- BGLP0007 - EssayDocument5 pagesBGLP0007 - EssayFempower MéxicoNo ratings yet

- Intergovernmental Fiscal Relations Universal Princ PDFDocument43 pagesIntergovernmental Fiscal Relations Universal Princ PDFDesalegn AregawiNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Public DebtDocument8 pagesLiterature Review On Public Debtpxihigrif100% (1)

- TikTok - The Tip of Americas Investment ConundrumDocument51 pagesTikTok - The Tip of Americas Investment ConundrumNew York PostNo ratings yet

- Federal DebtDocument14 pagesFederal Debtabhimehta90No ratings yet

- X. Ejercicios Cap10Document3 pagesX. Ejercicios Cap10Cristina Farré MontesóNo ratings yet

- Odious Debt PaperDocument46 pagesOdious Debt Paperredegalitarian9578No ratings yet

- Intergovernmental Transfers in Developing and TranDocument31 pagesIntergovernmental Transfers in Developing and TranFrancisco cossaNo ratings yet

- Liquidity Crises: Understanding Sources and Limiting Consequences: A Theoretical FrameworkDocument10 pagesLiquidity Crises: Understanding Sources and Limiting Consequences: A Theoretical FrameworkAnonymous i8ErYPNo ratings yet

- How To Assess Fiscal Risks From State-Owned Enterprises - Benchmarking and Stress TestingDocument14 pagesHow To Assess Fiscal Risks From State-Owned Enterprises - Benchmarking and Stress TestingAlexNo ratings yet

- Principles 2e Ch31Document28 pagesPrinciples 2e Ch31AdityaNo ratings yet

- The Real Effects of DebtDocument39 pagesThe Real Effects of DebtCsoregi NorbiNo ratings yet

- Debt Sustainability and The Egyptian DebtDocument13 pagesDebt Sustainability and The Egyptian DebtOmar ShehataNo ratings yet

- Fairness Fees PaperDocument8 pagesFairness Fees PaperRachel SilbersteinNo ratings yet

- Assignment OquaDocument7 pagesAssignment OquaOqua 'Fynebuoy' EtimNo ratings yet

- Pension Reform: Conceptual Foundations and Practical ChallengesDocument36 pagesPension Reform: Conceptual Foundations and Practical ChallengesHoover InstitutionNo ratings yet

- Adrian Et Al - 2013Document56 pagesAdrian Et Al - 2013Gülşah SütçüNo ratings yet

- Public Debt Lesson 6 and 7Document19 pagesPublic Debt Lesson 6 and 7BrianNo ratings yet

- Binder - LL - SecDocument23 pagesBinder - LL - SecMy-Acts Of-SeditionNo ratings yet

- Is It Time To Eliminate Federal Corporate Income TaxesDocument30 pagesIs It Time To Eliminate Federal Corporate Income TaxesEdward C LaneNo ratings yet

- Macroeconomic, Sectoral and Distributional Effects of The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act in The United StatesDocument30 pagesMacroeconomic, Sectoral and Distributional Effects of The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act in The United StatesmmunozlaNo ratings yet

- Local Government and Utility Firms' Debts: Marko Primorac, MaDocument22 pagesLocal Government and Utility Firms' Debts: Marko Primorac, Maninzemz03No ratings yet

- SRao Aiyagari and Albert Marcet and ThomasJ Sargent and Juha Seppälä 2002 Journal of Political EconomyDocument35 pagesSRao Aiyagari and Albert Marcet and ThomasJ Sargent and Juha Seppälä 2002 Journal of Political EconomyHHHNo ratings yet

- Neither A Lender Nor A Borrower Be Richard B. Gold Lend Lease Real Estate Investments Equity ResearchDocument8 pagesNeither A Lender Nor A Borrower Be Richard B. Gold Lend Lease Real Estate Investments Equity ResearchMichael CypriaNo ratings yet

- Asian Development Bank Institute: ADBI Working Paper SeriesDocument12 pagesAsian Development Bank Institute: ADBI Working Paper Seriessami kamlNo ratings yet

- Gabor European Derisking State-1Document30 pagesGabor European Derisking State-1Maximus L MadusNo ratings yet

- Buchanan Thesis of Public DebtDocument7 pagesBuchanan Thesis of Public Debtallysonthompsonboston100% (1)

- The Concept of Odious Debt in Public International Law: No. 185 2007 JulyDocument33 pagesThe Concept of Odious Debt in Public International Law: No. 185 2007 JulyMateus RabeloNo ratings yet

- A Cross-Cultural Analysis of Censorship On CampusesDocument44 pagesA Cross-Cultural Analysis of Censorship On CampusesDavid C. SantaNo ratings yet

- Cross-Cultural Gender Differences in Preference For A Caring MoralityDocument8 pagesCross-Cultural Gender Differences in Preference For A Caring MoralityDavid C. SantaNo ratings yet

- Cash Transfers, Labor Supply, and Gender Inequality Evidence From South AfricaDocument27 pagesCash Transfers, Labor Supply, and Gender Inequality Evidence From South AfricaDavid C. SantaNo ratings yet

- A Meta-Analysis of Procedures To Change Implicit BiasDocument74 pagesA Meta-Analysis of Procedures To Change Implicit BiasDavid C. SantaNo ratings yet

- Cambridge and The Exclusion of Jordan PetersonDocument6 pagesCambridge and The Exclusion of Jordan PetersonDavid C. SantaNo ratings yet

- Women's Employment and Childcare Choices in Spain Through The Great RecessionDocument27 pagesWomen's Employment and Childcare Choices in Spain Through The Great RecessionDavid C. SantaNo ratings yet

- Does Gender Influence The Provision of Fringe Benefits Evidence From Vietnamese SMEsDocument31 pagesDoes Gender Influence The Provision of Fringe Benefits Evidence From Vietnamese SMEsDavid C. SantaNo ratings yet

- Reversal of Fortune-Geography and Institutions in The Making of The Modern World Income DistributionDocument64 pagesReversal of Fortune-Geography and Institutions in The Making of The Modern World Income DistributionDavid C. SantaNo ratings yet

- Free Expression On College CampusesDocument20 pagesFree Expression On College CampusesDavid C. SantaNo ratings yet

- Caste, Kinship, and Life Course Rethinking Women's Work and Agency in Rural South IndiaDocument27 pagesCaste, Kinship, and Life Course Rethinking Women's Work and Agency in Rural South IndiaDavid C. SantaNo ratings yet

- Sage Publications, Inc. Association For Psychological ScienceDocument8 pagesSage Publications, Inc. Association For Psychological ScienceDavid C. SantaNo ratings yet

- From Self-Enhancement To Supporting Censorship-The Third-Person Effect Process in The Case of Internet PornographyDocument27 pagesFrom Self-Enhancement To Supporting Censorship-The Third-Person Effect Process in The Case of Internet PornographyDavid C. SantaNo ratings yet

- The Two Sexes-Growing Up Apart, Coming Together.Document3 pagesThe Two Sexes-Growing Up Apart, Coming Together.David C. SantaNo ratings yet

- Does The Unemployment Rate Affect The Divorce Rate-An Analysis of State Data 1960-2005.Document11 pagesDoes The Unemployment Rate Affect The Divorce Rate-An Analysis of State Data 1960-2005.David C. SantaNo ratings yet

- SSS Phic Pag-IbigDocument5 pagesSSS Phic Pag-IbigLara YuloNo ratings yet

- Lesco 3Document1 pageLesco 3Dr. Tanvir ZaverNo ratings yet

- Business Taxation Past Paper 2019Document2 pagesBusiness Taxation Past Paper 2019Adeel AhmedNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5 v5 RevisedDocument18 pagesChapter 5 v5 RevisedThe makas AbababaNo ratings yet

- Tax ProjectDocument4 pagesTax Projecthritik guptaNo ratings yet

- PWC Tax GuideDocument30 pagesPWC Tax Guideshikhagupta3288No ratings yet

- GA Tax GuideDocument46 pagesGA Tax Guidedamilano1No ratings yet

- The FundamentalDocument15 pagesThe FundamentalDanica ConcepcionNo ratings yet

- Taxation For Self-Employed Ver1.0Document23 pagesTaxation For Self-Employed Ver1.0Xeena HavenNo ratings yet

- Management ScienceDocument2 pagesManagement ScienceManuela MagnoNo ratings yet

- Regular Allowable Itemized Deductions Itemized Deductions From Gross IncomeDocument13 pagesRegular Allowable Itemized Deductions Itemized Deductions From Gross IncomeRosalie Colarte LangbayNo ratings yet

- Week 6 Applied EconomicsDocument14 pagesWeek 6 Applied EconomicsVincent Factor100% (2)

- Instructions For Completing Form 4506-C (Individial Taxpayer)Document1 pageInstructions For Completing Form 4506-C (Individial Taxpayer)GlendaNo ratings yet

- Vanisha Patika Sari - c1c020055 - Tugas Minggu Ke 14 BingDocument7 pagesVanisha Patika Sari - c1c020055 - Tugas Minggu Ke 14 BingVanisha PatikaNo ratings yet

- Ertificat E of D FN Resident For Indone T Withh F R - DGT 2: C O Micile O ON SIA AX Oldin G O M)Document2 pagesErtificat E of D FN Resident For Indone T Withh F R - DGT 2: C O Micile O ON SIA AX Oldin G O M)Reviansyah Machfudin YusufNo ratings yet

- Brief Note On Car Hiring of CarDocument2 pagesBrief Note On Car Hiring of CarDilip AgrawalNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Acc II CH 3 & 4Document13 pagesFundamentals of Acc II CH 3 & 4Sisay Belong To Jesus100% (2)

- Semifinalists in The 2020 National Merit Scholarship ProgramDocument5 pagesSemifinalists in The 2020 National Merit Scholarship Programjmjr30No ratings yet

- Tax Credits and Calculation of Tax: What Is Income Tax?Document59 pagesTax Credits and Calculation of Tax: What Is Income Tax?Moilah MuringisiNo ratings yet

- Health System and Services Profile of JamaicaDocument25 pagesHealth System and Services Profile of JamaicaZineil BlackwoodNo ratings yet

- Circular Refund 142 11 2020Document3 pagesCircular Refund 142 11 2020Gulrana AlamNo ratings yet

- Salary StructureDocument1 pageSalary Structureomer farooqNo ratings yet

- E Liwag 01312007 OLDDocument2 pagesE Liwag 01312007 OLDdaqs06No ratings yet

- Tax Invoice - SL 20-21 142 - 26 - 06 - 20 - EssarDocument1 pageTax Invoice - SL 20-21 142 - 26 - 06 - 20 - EssarsandyNo ratings yet

- AMC BillDocument1 pageAMC BillADVIE4 AllenNo ratings yet

- Pay As You Go (Payg) WithholdingDocument70 pagesPay As You Go (Payg) WithholdingliamNo ratings yet

- Calamba Steel Vs CIR, GR 151857, April 28, 2005Document2 pagesCalamba Steel Vs CIR, GR 151857, April 28, 2005katentom-1No ratings yet

Barro On The Ricardian Equivalence Theorem

Barro On The Ricardian Equivalence Theorem

Uploaded by

David C. SantaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Barro On The Ricardian Equivalence Theorem

Barro On The Ricardian Equivalence Theorem

Uploaded by

David C. SantaCopyright:

Available Formats

Barro on the Ricardian Equivalence Theorem

Author(s): James M. Buchanan

Source: Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 84, No. 2 (Apr., 1976), pp. 337-342

Published by: The University of Chicago Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1831905 .

Accessed: 26/05/2014 16:50

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal

of Political Economy.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 80.109.52.76 on Mon, 26 May 2014 16:50:47 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Barro on the Ricardian Equivalence

Theorem

James M. Buchanan

VirginiaPolytechnicInstituteand State University

Is public debt issue equivalent to taxation? This is an age-old question in

public finance theory. David Ricardo presented the case for the affirma-

tive.1 Professor Robert J. Barro reexamines the question in his recent

paper (1974) without, however, making reference to Ricardo or other

early contributors. Although his discussion is carefully qualified to allow

for exceptions under specified conditions, the thrust of Barro's argument

supports the Ricardian theorem to the effect that taxation and public

debt issue exert basically equivalent effects.

Barro's central emphasis is on demonstrating that, under reasonable

conditions which involve overlapping generations of persons with finite

lives, taxpayers will capitalize the future obligations that public debt

issue embodies. To the extent that this capitalization occurs, government

bonds do not add to the perceived net wealth in the economy. From this

Barro infers that the substitution of debt for tax finance will exert no

expansionary effect on total spending. There are two questions here. Are

the future tax liabilities fully capitalized? And, even if they are, does this

necessarily imply that the fiscal policy shift exerts no effect on total

spending? To establish the second result, it is necessary to examine the

differential impacts of taxation and debt issue, quite apart from the

question of the capitalization of future taxes. Barro wholly neglects this

necessary part of any comparative analysis of the two fiscal instruments,

and, because of this neglect, his conclusion is not nearly so relevant for

policy as it seems to be. This neglect may stem from Barro's failure to

specify properly the inclusive set of transactions that debt issue represents.

I am indebted to my colleagues Gordon Tullock, Nicolaus Tideman, and Richard

Wagner for helpful comments.

I The basic Ricardian discussion is contained in Ricardo (1951, vol. 1, pp. 244-49) and

"Funding System" (vol. 4, pp. 149-200). Antonio De Viti De Marco elaborated the

Ricardian thesis in a somewhat modified setting. His analysis was first developed in De

Viti De Marco (1893). Essentially the same analysis appears in De Viti De Marco (1936,

bk. 5, chap. 1, pp. 377-98). For my own summary discussions, see Buchanan (1958,

pp. 43-44, 114-22).

[Journal of Political Economy, 1976, vol. 84, no. 2]

? 1976 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved.

337

This content downloaded from 80.109.52.76 on Mon, 26 May 2014 16:50:47 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

338 JOURNAL OF POLITICAL ECONOMY

After constructing his overlapping-generations model with no govern-

ment sector, Barro then superimposes an issue of public debt without off-

setting or compensating changes. He states, "Suppose now that the gov-

ernment issues an amount of debt, B, which can be thought of as taking

the form of one-period, real-valued bonds.... It can be assumed, for

simplicity, that the government bond issue takes the form of a helicopter

drop to currently old (generation 1) households" (p. 1101). We are

immediately prompted to inquire why any government would undertake

such an activity. If the purpose is to increase total spending in the

economy, this might be done much more readily by the straightforward

issue of money, which does not involve future payment obligations. Or,

if the purpose is to finance public spending without current taxation or

money creation, bonds must be sold in the private capital market, and

persons who purchase these bonds must draw down private investments

or reduce private consumption. Under this condition, it is impossible that

"the increase in B implies a one-to-one increase in the asset supply. .

(p. 1103).

There are two alternative interpretations of Barro's seemingly bizarre

model of bond issue. The first and more constructive interpretation sug-

gests that Barro introduces the model only because of his concentrated

interest on the wealth effect of debt issue within the strictly Ricardian or

differential-incidence framework. The second interpretation suggests that

Barro's analysis applies only when governments do, in fact, incur future

payment obligations without securing command over funds in the initial

period, a setting which does not apply to public debt as ordinarily con-

ceived but which may apply to the operation of the social security system

in the United States.

These quite separate interpretations may be discussed briefly in turn.

Barro directly follows the first statement cited above with the following:

"Equivalently, it could be assumed that the bonds were sold on a com-

petitive capital market, with the proceeds of this sale used to effect a

lump-sum transfer to generation 1 households" (p. 1101). Superficially,

the two operations are not at all equivalent. If, however, the bonds drop-

ped from the helicopter are marketable, those who get them may, as

desired, convert them into currency. The net effects are the same as the

government's sale of bonds to voluntary purchasers along with the lump-

sum transfer of the proceeds to the same persons who would have received

the bonds in the first model. In either case, the government bonds will

replace private bonds or other assets, and the net-wealth effects of this

substitution must be considered along with the wealth effects embodied

in the capitalization of future tax liabilities. Why might Barro have felt

that he could neglect the first of these considerations? He could have done

so if his interest is exclusively on determining the differential effects of

This content downloaded from 80.109.52.76 on Mon, 26 May 2014 16:50:47 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

COMMUNICATIONS 339

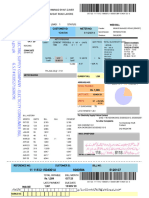

(a)

Taxation

Assets Liabilities

Public assets (?)

Private assets (-)

(b)

Debt Issue

Assets Liabilities

Public assets (+)

Private assets (-)

Government Present value

bonds (+) of tax liabilities (+)

FIG. 1

debt and tax financing, and he is willing to make the severely restrictive

assumption that the source for the ultimate purchase of the government

bonds is identical to the source from which the alternative taxes would

be drawn.

This may be clarified by the following simple t-account comparison.

Under the tax alternative, the t-account adjustments appear as in figure

la. Under either of the debt-issue alternatives, the final t-account adjust-

ments are as shown in figure l b. If we are interested only in comparing the

differential effects of tax and debt finance for a given level of spending,

and if we are willing to make the heroic assumption that the direct

impact of these two fiscal instruments is identical, then the part of figure

lb below the dotted line represents the net difference between the two

combined fiscal operations.

In this interpretation, Barro is simply not concerned either with the

independent effects of debt-financed spending on net wealth or with the

effects of public debt issue in a modified differential-incidence framework.

Does the financing of public spending by genuine public debt increase

aggregate demand in the economy? This is a meaningful and relevant

question that has been more widely discussed than the one which Barro

analyzes. In terms of figure 1, this question requires us to look at the

This content downloaded from 80.109.52.76 on Mon, 26 May 2014 16:50:47 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

340 JOURNAL OF POLITICAL ECONOMY

adjustments in figure lb only, without regard to any comparison with 1a.

Provided that we do not go beyond the simple t-accounts, the net-wealth

effect of debt financing of public outlay seems to depend on the degree

to which future taxes are discounted. But this neglects the possible effects

of the sale of bonds on displaced private borrowers. To the extent that

these borrowers, those who would have secured the funds had not the

government done so, would have applied the same discount factor to the

future payment obligations as that applied by the public borrowers (the

taxpayers), net wealth will not be modified regardless of the degree of

capitalization of future taxes. It seems reasonable to suggest that perceived

net wealth, as relevant for spending behavior, increases with increases in

either private or public debt. But there are offsetting changes, and the

direction of net effect depends on the differences.2

Perhaps the most familiar setting is one that compares the effects of

debt financing with explicit money creation for a given increment in

public outlay. This, too, is a differential-incidence model but one that is

quite separate from the Ricardo-Barro model. The analysis here requires

all of the considerations noted above with respect to independent debt

issue but has the advantage of emphasizing the specific deflationary impact

of debt sales quite apart from the question of future tax capitalization.3

This latter aspect assumes primary importance, of course, when the

principal objective for fiscal policy is to generate an expansion in aggregate

spending.

Barro's analysis may be interpreted in a second and more restrictive

way that takes his explicit model for debt issue at face value and makes

no attempt to generalize it toward meeting the expressed purpose of the

paper. In this view, Barro analyzes the issue of debt by a government

which does not secure funds in the initial period and which does not allow

its debt obligations to be resold in markets. Something analytically

analogous to this sort of operation may take place when legislation is

enacted which commits the government to pay old-age pensions without

at the same time fully financing such obligations with current levies of

taxes. Barro does, in fact, refer to the applicability of his analysis to social

security financing, and he may have been led to generalize too readily

from this somewhat singular example. In this setting, the aggregate

economic effects depend strictly on the relative discounting of future

benefits on the one hand and future taxes on the other.

2 In a strict accounting sense, future obligations that are implicit in any debt issue,

public or private, may be fully capitalized, while at the same time behavior may reflect

the rational intent of borrowers to accelerate spending. In this context, a lending-borrow-

ing transaction must affect aggregate spending quite apart from the absence of change

in measured net wealth. See R. N. McKean (1951, particularly p. 75).

3 See Musgrave (1959, p. 538). For particular emphasis on the deflationary impact of

debt issue see Rolph (1957).

This content downloaded from 80.109.52.76 on Mon, 26 May 2014 16:50:47 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

COMMUNICATIONS 34I

To this point my criticism of Barro's paper has been confined to the

ambiguities in his setting for public debt issue along with the possible

incompleteness of his analysis. I have not challenged his basic conclusion

that future taxes will tend to be fully discounted save under the exceptions

that he notes. Nonetheless, this conclusion may be questioned on empirical

grounds. What evidence might be adduced to suggest that individuals do

not, in fact, modify their behavior fully to adjust for the present values of

the future tax obligations that public debt issue implies?

Consider, first, the social security system which, as indicated, fits more

closely with the narrow interpretation of Barro's results. One implication

of his analysis would be that the social security system as it has operated

should not have modified the rate of private saving in the economy. This

runs counter to the result that has been observed by Martin Feldstein,

who estimates that the rate of private saving has been reduced by some

38 percent.4 Additional evidence may be indirectly available from the

historical record if the basic public choice paradigm is accepted. If

politicians are ultimately responsive to the desires of their constituents,

we may infer something about constituents' evaluations by observing

the behavior of politicians. The 40-year history of social security financing

yields ample evidence that politicians are extremely reluctant to adopt

anything which smacks of full funding for the system. Under the Barro

hypothesis, there should be roughly indifferent public reactions to a fully

funded and to an unfunded pension system.

If we shift to the more general model, governments should be roughly

indifferent as between financing current outlays from taxation and from

genuine debt issue. There should be no effect of debt-financed deficits

on aggregate spending. Direct testing of this hypothesis is difficult because

of the fact that budget deficits are normally financed by some combination

of genuine debt issue and money creation.5 Again, however, the behavior

of legislators seems to offer indirect evidence against the capitalization

hypothesis. Can anyone in the post-Keynesian world of 1975 seriously

question the proclivity of politicians to expand public debt in preference

to tax increases? At the state-local level, where the money-creation

powers do not exist, why should we observe constitutional constraints on

public debts?6 With public as with private finance, the very creation of

debt suggests that borrowers desire to accelerate spending.

4 See Feldstein (1974). It should be noted that, even with full lifetime discounting of

future taxes, a life-cycle model of utility maximization would produce a negative effect

on private saving under a pay-as-we-go public pension system. But, of course, the life-

cycle model itself implies that debt financing necessarily differs from tax financing to

the extent that debt is not retired within a generation.

Kochin (1974) attempted to estimate empirically the impact of deficit spending on

private consumption. His conclusions tend to support the capitalization view.

6 Admittedly, the out-migration prospect for citizens in local jurisdictions offers an

offsetting influence to full discounting.

This content downloaded from 80.109.52.76 on Mon, 26 May 2014 16:50:47 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

342 JOURNAL OF POLITICAL ECONOMY

References

Barro, RobertJ. "Are Government Bonds Net Wealth?" J.P.E. 82, no. 6 (Novem-

ber/December 1974): 1095-1117.

Buchanan, James M. Public Principles of Public Debt. Homewood, Ill.: Irwin, 1958.

De Viti De Marco, Antonio. "La Pressione tributaria dell' imposta e del prestito."

Giornale degli economist 1 (1893): 216-31.

. First Principles of Public Finance. Translated by E. P. Marget. New York:

Harcourt Brace, 1936.

Feldstein, Martin. "Social Security, Induced Retirement, and Aggregate Capital

Accumulation." J.P.E. 82, no. 5 (September/October 1974): 905-26.

Kochin, Lewis. "Are Future Taxes Anticipated by Consumers?" J. Money,

Credit and Banking 6 (August 1974): 385-94.

McKean, R. N. "Liquidity and a National Balance Sheet." J.P.E. 57, no. 6

(December 1949): 506-22. Reprinted in Readingsin MonetaryTheory.Edited

by F. A. Lutz and L. W. Mints. New York: Blakiston, 1951.

Musgrave, R. A. The Theory of Public Finance. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1959.

Ricardo, David. Principles of Political Economyand Taxation, Works and Correspondence.

Edited by Piero Straffa. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1951.

Rolph, Earl. "Principles of Debt Management." A.E.R. 47 (June 1957): 302-20.

This content downloaded from 80.109.52.76 on Mon, 26 May 2014 16:50:47 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Adp Pay Stub TemplateDocument1 pageAdp Pay Stub TemplateJordan McKenna0% (1)

- Pay Slip - 473995 - Mar-22Document1 pagePay Slip - 473995 - Mar-22Siva Ramakrishna0% (1)

- Philippine Public DebtDocument20 pagesPhilippine Public Debtmark genove100% (3)

- UK Vs USA Common Law Vs Common SenceDocument7 pagesUK Vs USA Common Law Vs Common SenceShlomo Isachar Ovadiah100% (1)

- Barro On The Ricardian Equivalence TheoremDocument6 pagesBarro On The Ricardian Equivalence TheoremvalkriyeNo ratings yet

- On The Determination of The Public DebtDocument33 pagesOn The Determination of The Public DebtFederico Castello RojoNo ratings yet

- On The Determination of The Public DebtDocument32 pagesOn The Determination of The Public DebtPablo SantizoNo ratings yet

- T Rident: Municipal ResearchDocument4 pagesT Rident: Municipal Researchapi-245850635No ratings yet

- Can Democracy Prevent Default?: Sebastian M. SaieghDocument22 pagesCan Democracy Prevent Default?: Sebastian M. SaieghMateus RabeloNo ratings yet

- Are Government Bonds Net Wealth? Robert J. BarroDocument23 pagesAre Government Bonds Net Wealth? Robert J. BarroMaksim Los1No ratings yet

- Elgin y Uras 2012 - Public Debt, Sovereign Default Risk and Shadow Economy PAPER BASEDocument13 pagesElgin y Uras 2012 - Public Debt, Sovereign Default Risk and Shadow Economy PAPER BASEpcefanquNo ratings yet

- Calvo, G (1988) - Servicing The Public Debt - The Role of ExpectationsDocument16 pagesCalvo, G (1988) - Servicing The Public Debt - The Role of ExpectationsDaniela SanabriaNo ratings yet

- A Dynamic Theory of Public Spending, Taxation and DebtDocument36 pagesA Dynamic Theory of Public Spending, Taxation and DebtLuis Carlos Calixto RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Are There Spillover Effects From Munis?: Rabah Arezki, Bertrand Candelon and Amadou N. R. SyDocument19 pagesAre There Spillover Effects From Munis?: Rabah Arezki, Bertrand Candelon and Amadou N. R. SyFerdi GunesNo ratings yet

- Debt Afford Ability PaperDocument21 pagesDebt Afford Ability PaperKen KrizNo ratings yet

- Taxes, Money and Public DebtDocument7 pagesTaxes, Money and Public DebtFerhat AkyüzNo ratings yet

- R-G 0: Can We Sleep More Soundly?: by Paolo Mauro and Jing ZhouDocument32 pagesR-G 0: Can We Sleep More Soundly?: by Paolo Mauro and Jing ZhoutegelinskyNo ratings yet

- Why Have States Partly Lost Their Ability To Tax How Have Governments Been Compensating For Their Fiscal Faults Discuss The Fi 1587138428Document10 pagesWhy Have States Partly Lost Their Ability To Tax How Have Governments Been Compensating For Their Fiscal Faults Discuss The Fi 1587138428AdamNo ratings yet

- BIS Working PapersDocument40 pagesBIS Working PapersAdminAliNo ratings yet

- Financial Accelerator: Economic Activity Can Further Exacerbate The Financial DownturnDocument30 pagesFinancial Accelerator: Economic Activity Can Further Exacerbate The Financial DownturnSasraNo ratings yet

- Restructuring A Sovereign Debtor's Contingent LiabilitiesDocument10 pagesRestructuring A Sovereign Debtor's Contingent Liabilitiesvidovdan9852No ratings yet

- Unit 13Document14 pagesUnit 13Lekhutla TFNo ratings yet

- A Framework For Debt Relief Cum Adjustment Packages 010523Document19 pagesA Framework For Debt Relief Cum Adjustment Packages 010523MANI SNo ratings yet

- R Gov Bonds Net WealthDocument24 pagesR Gov Bonds Net WealthNabil LahhamNo ratings yet

- Meaning:: Public Debt: Meaning, Objectives and Problems!Document5 pagesMeaning:: Public Debt: Meaning, Objectives and Problems!document singhNo ratings yet

- Ifdp 1104Document36 pagesIfdp 1104TBP_Think_TankNo ratings yet

- The Level and Composition of Public Sector Debt in Emerging Market CrisesDocument35 pagesThe Level and Composition of Public Sector Debt in Emerging Market CrisesTBP_Think_TankNo ratings yet

- Bargained Haircuts and Debt Policy Implications: Aloisio Araujo, Marcia Leon and Rafael SantosDocument28 pagesBargained Haircuts and Debt Policy Implications: Aloisio Araujo, Marcia Leon and Rafael SantosFrancisco IsidroNo ratings yet

- Debt Overhang and Recapitalization in Closed and Open EconomiesDocument30 pagesDebt Overhang and Recapitalization in Closed and Open EconomiesPeNo ratings yet

- Calvo Deuda PublicaDocument16 pagesCalvo Deuda PublicaMartin ArrutiNo ratings yet

- Looking Behind The Aggregates: A Reply To "Facts and Myths About The Financial Crisis of 2008"Document18 pagesLooking Behind The Aggregates: A Reply To "Facts and Myths About The Financial Crisis of 2008"StonerNo ratings yet

- Letelier - Municipal Borrowing in Chile (2011)Document17 pagesLetelier - Municipal Borrowing in Chile (2011)rosoriofNo ratings yet

- Problem of Internal Debt and External DebtDocument6 pagesProblem of Internal Debt and External DebtFAISAL KHANNo ratings yet

- Bank Clerks' Exam: EnglishDocument8 pagesBank Clerks' Exam: Englishਰਾਹ ਗੀਰNo ratings yet

- BGLP0007 - EssayDocument5 pagesBGLP0007 - EssayFempower MéxicoNo ratings yet

- Intergovernmental Fiscal Relations Universal Princ PDFDocument43 pagesIntergovernmental Fiscal Relations Universal Princ PDFDesalegn AregawiNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Public DebtDocument8 pagesLiterature Review On Public Debtpxihigrif100% (1)

- TikTok - The Tip of Americas Investment ConundrumDocument51 pagesTikTok - The Tip of Americas Investment ConundrumNew York PostNo ratings yet

- Federal DebtDocument14 pagesFederal Debtabhimehta90No ratings yet

- X. Ejercicios Cap10Document3 pagesX. Ejercicios Cap10Cristina Farré MontesóNo ratings yet

- Odious Debt PaperDocument46 pagesOdious Debt Paperredegalitarian9578No ratings yet

- Intergovernmental Transfers in Developing and TranDocument31 pagesIntergovernmental Transfers in Developing and TranFrancisco cossaNo ratings yet

- Liquidity Crises: Understanding Sources and Limiting Consequences: A Theoretical FrameworkDocument10 pagesLiquidity Crises: Understanding Sources and Limiting Consequences: A Theoretical FrameworkAnonymous i8ErYPNo ratings yet

- How To Assess Fiscal Risks From State-Owned Enterprises - Benchmarking and Stress TestingDocument14 pagesHow To Assess Fiscal Risks From State-Owned Enterprises - Benchmarking and Stress TestingAlexNo ratings yet

- Principles 2e Ch31Document28 pagesPrinciples 2e Ch31AdityaNo ratings yet

- The Real Effects of DebtDocument39 pagesThe Real Effects of DebtCsoregi NorbiNo ratings yet

- Debt Sustainability and The Egyptian DebtDocument13 pagesDebt Sustainability and The Egyptian DebtOmar ShehataNo ratings yet

- Fairness Fees PaperDocument8 pagesFairness Fees PaperRachel SilbersteinNo ratings yet

- Assignment OquaDocument7 pagesAssignment OquaOqua 'Fynebuoy' EtimNo ratings yet

- Pension Reform: Conceptual Foundations and Practical ChallengesDocument36 pagesPension Reform: Conceptual Foundations and Practical ChallengesHoover InstitutionNo ratings yet

- Adrian Et Al - 2013Document56 pagesAdrian Et Al - 2013Gülşah SütçüNo ratings yet

- Public Debt Lesson 6 and 7Document19 pagesPublic Debt Lesson 6 and 7BrianNo ratings yet

- Binder - LL - SecDocument23 pagesBinder - LL - SecMy-Acts Of-SeditionNo ratings yet

- Is It Time To Eliminate Federal Corporate Income TaxesDocument30 pagesIs It Time To Eliminate Federal Corporate Income TaxesEdward C LaneNo ratings yet

- Macroeconomic, Sectoral and Distributional Effects of The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act in The United StatesDocument30 pagesMacroeconomic, Sectoral and Distributional Effects of The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act in The United StatesmmunozlaNo ratings yet

- Local Government and Utility Firms' Debts: Marko Primorac, MaDocument22 pagesLocal Government and Utility Firms' Debts: Marko Primorac, Maninzemz03No ratings yet

- SRao Aiyagari and Albert Marcet and ThomasJ Sargent and Juha Seppälä 2002 Journal of Political EconomyDocument35 pagesSRao Aiyagari and Albert Marcet and ThomasJ Sargent and Juha Seppälä 2002 Journal of Political EconomyHHHNo ratings yet

- Neither A Lender Nor A Borrower Be Richard B. Gold Lend Lease Real Estate Investments Equity ResearchDocument8 pagesNeither A Lender Nor A Borrower Be Richard B. Gold Lend Lease Real Estate Investments Equity ResearchMichael CypriaNo ratings yet

- Asian Development Bank Institute: ADBI Working Paper SeriesDocument12 pagesAsian Development Bank Institute: ADBI Working Paper Seriessami kamlNo ratings yet

- Gabor European Derisking State-1Document30 pagesGabor European Derisking State-1Maximus L MadusNo ratings yet

- Buchanan Thesis of Public DebtDocument7 pagesBuchanan Thesis of Public Debtallysonthompsonboston100% (1)

- The Concept of Odious Debt in Public International Law: No. 185 2007 JulyDocument33 pagesThe Concept of Odious Debt in Public International Law: No. 185 2007 JulyMateus RabeloNo ratings yet

- A Cross-Cultural Analysis of Censorship On CampusesDocument44 pagesA Cross-Cultural Analysis of Censorship On CampusesDavid C. SantaNo ratings yet

- Cross-Cultural Gender Differences in Preference For A Caring MoralityDocument8 pagesCross-Cultural Gender Differences in Preference For A Caring MoralityDavid C. SantaNo ratings yet

- Cash Transfers, Labor Supply, and Gender Inequality Evidence From South AfricaDocument27 pagesCash Transfers, Labor Supply, and Gender Inequality Evidence From South AfricaDavid C. SantaNo ratings yet

- A Meta-Analysis of Procedures To Change Implicit BiasDocument74 pagesA Meta-Analysis of Procedures To Change Implicit BiasDavid C. SantaNo ratings yet

- Cambridge and The Exclusion of Jordan PetersonDocument6 pagesCambridge and The Exclusion of Jordan PetersonDavid C. SantaNo ratings yet

- Women's Employment and Childcare Choices in Spain Through The Great RecessionDocument27 pagesWomen's Employment and Childcare Choices in Spain Through The Great RecessionDavid C. SantaNo ratings yet

- Does Gender Influence The Provision of Fringe Benefits Evidence From Vietnamese SMEsDocument31 pagesDoes Gender Influence The Provision of Fringe Benefits Evidence From Vietnamese SMEsDavid C. SantaNo ratings yet

- Reversal of Fortune-Geography and Institutions in The Making of The Modern World Income DistributionDocument64 pagesReversal of Fortune-Geography and Institutions in The Making of The Modern World Income DistributionDavid C. SantaNo ratings yet

- Free Expression On College CampusesDocument20 pagesFree Expression On College CampusesDavid C. SantaNo ratings yet

- Caste, Kinship, and Life Course Rethinking Women's Work and Agency in Rural South IndiaDocument27 pagesCaste, Kinship, and Life Course Rethinking Women's Work and Agency in Rural South IndiaDavid C. SantaNo ratings yet

- Sage Publications, Inc. Association For Psychological ScienceDocument8 pagesSage Publications, Inc. Association For Psychological ScienceDavid C. SantaNo ratings yet

- From Self-Enhancement To Supporting Censorship-The Third-Person Effect Process in The Case of Internet PornographyDocument27 pagesFrom Self-Enhancement To Supporting Censorship-The Third-Person Effect Process in The Case of Internet PornographyDavid C. SantaNo ratings yet

- The Two Sexes-Growing Up Apart, Coming Together.Document3 pagesThe Two Sexes-Growing Up Apart, Coming Together.David C. SantaNo ratings yet

- Does The Unemployment Rate Affect The Divorce Rate-An Analysis of State Data 1960-2005.Document11 pagesDoes The Unemployment Rate Affect The Divorce Rate-An Analysis of State Data 1960-2005.David C. SantaNo ratings yet

- SSS Phic Pag-IbigDocument5 pagesSSS Phic Pag-IbigLara YuloNo ratings yet

- Lesco 3Document1 pageLesco 3Dr. Tanvir ZaverNo ratings yet

- Business Taxation Past Paper 2019Document2 pagesBusiness Taxation Past Paper 2019Adeel AhmedNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5 v5 RevisedDocument18 pagesChapter 5 v5 RevisedThe makas AbababaNo ratings yet

- Tax ProjectDocument4 pagesTax Projecthritik guptaNo ratings yet

- PWC Tax GuideDocument30 pagesPWC Tax Guideshikhagupta3288No ratings yet

- GA Tax GuideDocument46 pagesGA Tax Guidedamilano1No ratings yet

- The FundamentalDocument15 pagesThe FundamentalDanica ConcepcionNo ratings yet

- Taxation For Self-Employed Ver1.0Document23 pagesTaxation For Self-Employed Ver1.0Xeena HavenNo ratings yet

- Management ScienceDocument2 pagesManagement ScienceManuela MagnoNo ratings yet

- Regular Allowable Itemized Deductions Itemized Deductions From Gross IncomeDocument13 pagesRegular Allowable Itemized Deductions Itemized Deductions From Gross IncomeRosalie Colarte LangbayNo ratings yet

- Week 6 Applied EconomicsDocument14 pagesWeek 6 Applied EconomicsVincent Factor100% (2)

- Instructions For Completing Form 4506-C (Individial Taxpayer)Document1 pageInstructions For Completing Form 4506-C (Individial Taxpayer)GlendaNo ratings yet

- Vanisha Patika Sari - c1c020055 - Tugas Minggu Ke 14 BingDocument7 pagesVanisha Patika Sari - c1c020055 - Tugas Minggu Ke 14 BingVanisha PatikaNo ratings yet

- Ertificat E of D FN Resident For Indone T Withh F R - DGT 2: C O Micile O ON SIA AX Oldin G O M)Document2 pagesErtificat E of D FN Resident For Indone T Withh F R - DGT 2: C O Micile O ON SIA AX Oldin G O M)Reviansyah Machfudin YusufNo ratings yet

- Brief Note On Car Hiring of CarDocument2 pagesBrief Note On Car Hiring of CarDilip AgrawalNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Acc II CH 3 & 4Document13 pagesFundamentals of Acc II CH 3 & 4Sisay Belong To Jesus100% (2)

- Semifinalists in The 2020 National Merit Scholarship ProgramDocument5 pagesSemifinalists in The 2020 National Merit Scholarship Programjmjr30No ratings yet

- Tax Credits and Calculation of Tax: What Is Income Tax?Document59 pagesTax Credits and Calculation of Tax: What Is Income Tax?Moilah MuringisiNo ratings yet

- Health System and Services Profile of JamaicaDocument25 pagesHealth System and Services Profile of JamaicaZineil BlackwoodNo ratings yet

- Circular Refund 142 11 2020Document3 pagesCircular Refund 142 11 2020Gulrana AlamNo ratings yet

- Salary StructureDocument1 pageSalary Structureomer farooqNo ratings yet

- E Liwag 01312007 OLDDocument2 pagesE Liwag 01312007 OLDdaqs06No ratings yet

- Tax Invoice - SL 20-21 142 - 26 - 06 - 20 - EssarDocument1 pageTax Invoice - SL 20-21 142 - 26 - 06 - 20 - EssarsandyNo ratings yet

- AMC BillDocument1 pageAMC BillADVIE4 AllenNo ratings yet

- Pay As You Go (Payg) WithholdingDocument70 pagesPay As You Go (Payg) WithholdingliamNo ratings yet

- Calamba Steel Vs CIR, GR 151857, April 28, 2005Document2 pagesCalamba Steel Vs CIR, GR 151857, April 28, 2005katentom-1No ratings yet