Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Burdens of Love

Burdens of Love

Uploaded by

Albert CamusOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Burdens of Love

Burdens of Love

Uploaded by

Albert CamusCopyright:

Available Formats

The Burdens of Love

Author(s): Amelie Rorty

Source: The Journal of Ethics , December 2016, Vol. 20, No. 4 (December 2016), pp. 341-

354

Published by: Springer

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/44077337

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Springer is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of

Ethics

This content downloaded from

111.68.96.36 on Thu, 22 Oct 2020 05:32:53 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

J Ethics (2016) 20:341-354 /fiv

DOI 10.1 007/s 10892-01

The Burdens of Love

Amelie Rorty1,2

Received: 7 December 2015/ Accepted: 4 March 2016 /Published online: 30 April 2016

© Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2016

Abstract While we primarily love individual persons, we also love our work, our

homes, our activities and causes. To love is to be engaged in an active concern for

the objective well-being - the thriving - of whom and what we love. True love

mandates discovering in what that well-being consists and to be engaged in the

details of promoting it. Since our loves are diverse, we are often conflicted about the

priorities among the obligations they bring. Loving requires constant contextual

improvisatory adjustment of priorities among our commitments. Besides delighting

in - and being enhanced by - the presence and existence of another person (a place,

an institution, profession), love requires extended reflection and work.

Keywords Ambivolence • Choice • Commitment • Conflicts • Love • Priorities

...[L]ove (Liebe) is not to be understood as feeling (aesthetisch)...[or]

delight. . .It must rather be thought as. . . active benevolence, . . .which results in

beneficence... Kant, Metaphysics of Morals, H, 1.1. 25-30 (450)

...[L]ove of any variety... consists basically in a disinterested concern for the

flourishing or the well-being of the beloved. It is not driven by any ulterior

purpose. It seeks the good of the beloved as something that is desirable for its

own sake.... The lover identifies with his belo ved.... [He] takes the interests of

his beloved as his own, and consequently he benefits or suffers depending

upon whether those interests are or are not adequately served. Frankfurt

(2001)

CE3 Amelie Rorty

amelie_rorty@hms.harvard.edu

1 Tufts University, Medford, MA, USA

2 Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA

Ô Springer

This content downloaded from

111.68.96.36 on Thu, 22 Oct 2020 05:32:53 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

342 A. Rorty

1 Loving an

Although Imm

contexts, with

true love in its

sexually obsess

the point of in

about the love

referring to M

the mutual lov

Anthony and C

Beatrice, Socr

Such love can -

or o diminution

love can expres

needs and attit

childhood dep

functional/ex

contingent att

expressed, as it

or cautiously. L

Love affects a

and attention

because it requ

Whom or what

turn out: it aff

we receive and

Eulogies to lov

presence of an

jealousies, its f

question the le

distrust radic

psychologists a

etiology and

epistemology a

person or some

is it fungible?

irrational or un

1 In isolating love

complexities and

the Human Unde

character of any p

2 See the essays b

3 See, for exampl

4 See, e.g., Kraut

(2014), Jollimore

Ô Springer

This content downloaded from

111.68.96.36 on Thu, 22 Oct 2020 05:32:53 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Burdens of Love 343

and expression? What

play in our lives? Wh

is feared when we think of its ordeals or loss?

If Kant and Frankfurt - are right, it is no wonder that we want to be loved and

that we fear its loss. Being loved brings an ally to facing the vicissitudes that are the

substance of daily life; we find ourselves lost without the active attentive concern

that is at the core of love. Still, though we want to have the reliable support of

someone who loves us as a species of insurance, we do not want to be loved by just

anybody. The desire for love has its ambivalences: it can be risky to love and be

loved. Even though we long to be loved, we are often rightly hesitant, finicky about

whom we want to love us. It can be dangerous to be loved by someone who does not

understand us, or by someone who does not understand what love commands. It

takes a great deal of intelligent insight - and certainly a lot of time and work - to

love well. We might reasonably want to avoid being led astray by the love of a fool

or a villain who is sincerely and attentively committed to promoting (what they take

to be) our well-being. We want - we need - those who love us to support what is

genuinely best in us and best for us, even if it means trying to redirect or even

eradicate our floating desires. Kant and Ralph Waldo Emerson observed that we

want those who love us to see - to respect and admire-what is best in us; and yet we

also want them to know - and still lovingly to accept - us as we really are foibles,

faults and all.5 We may even want them to find our weaknesses endearing. It is this

tension that marks some of the complex terrain of love - the tension between

wanting those who love us to see us in the persona of our best selves and yet also to

cherish the flawed selves we actually are. With some trepidation, we want those who

love us to respect what is genuinely respect-worthy in us and yet to accept the fact

that we are often unable to live up to their expectations. Love is greedy and

demanding: we want those who love us to express their love appropriately calibrated

to our needs and moods. We also want them to want to love us, to be glad of loving

us, to think of their love as a blessing rather than an entrapment. We want them to

love us steadfastly, for our sakes and not because they love the duties, the pleasures

or the virtues of loving.6

What we want from those who love us may give us some indication of what we

implicitly commit ourselves to undertake when we love. To be sure, what we

want - what we hope to receive from being loved - may be so irrational as to have

no bearing on what we owe to those we love. What is even more unsettling, those

who take themselves to love someone sincerely, might well find themselves ceasing

to love, when they fully realize what it demands of them. In any case, love comes in

many varieties, for example, high passion love and comfortable old shoe love,

possessive love and laissez faire love.7 While dramatic differences in the tonality

and modality of love are centrally significant to its experience and to the role it plays

in the entire economy of a person's life, they do not affect its central core: insofar as

all these varieties of attachments and relationships are varieties of love , they evince

5 See Kant (1963); Emerson (1841).

6 See Stocker (1976, 1979).

7 I am grateful to MindaRae Amiran and Richard Schmitt for stressing this point.

â Springer

This content downloaded from

111.68.96.36 on Thu, 22 Oct 2020 05:32:53 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

344 A. Rorty

care and concer

propose to set

Frankfurt are

"Love is not...

were, it would

attentiveness t

another person

protects." If lo

they are in fo

end with good

will call our l

for Ella's thriv

her life-long, a

successful exer

thought, we do

finding himsel

apprehensive a

life trajectory

interests. It sh

growing love f

a matter of gr

loves someone

What happens

theirs.

Suppose that Abe does come to love Ella, and that he does so as whole heartedly

as anyone does. He becomes actively concerned to protect her, but - independently

of whether his love is returned-, that concern is surely not the end of the matter. As

Frankfurt puts it, "he identifies with [her] ... takes her interests as his own." For

this, much more than a gallant concern for her protection is required. Abe's love sets

him on an extended examination: to begin with, he needs to be fairly clear about his

own interests and commitments, his own conception of thriving and how it might

skew his understanding of Ella's best interests. After all, his conceptions of

happiness might be cast in the frame of his relatively limited understanding of its

general conditions - as it might be for wealth, fame or political power. If he loves

Ella, he cannot just project his own half-baked ideas of happiness on her: he needs

to understand her interests and preferences, her conception of what conduces to her

happiness. But since he is concerned for her objective happiness - her eudaimonia ,

all things considered, - he should not simply be directed by her ideas of her

conceptions of her happiness, her primary interests. After all, her ideas might be just

as half-baked as his. Independently of whether she returns his love, his concern for

her would mandate an attempt to engage her in reflecting on the objective conditions

8 Although personal love by no means exhausts the range of our loves, I shall, for the sake of simplicity,

initially use the example of romantic love to examine the structure and dynamics of generic love. In Sect.

4, I will turn to other, familiar but less often analyzed expressions of love - the love of home, of a

profession or of an activity.

â Springer

This content downloaded from

111.68.96.36 on Thu, 22 Oct 2020 05:32:53 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Burdens of Love 345

for happiness, for e

philosophical inquiry.

Initially this would

constitutes thriving in

time. Reflections of

integrate his active

organize a symposium

the devotion that is p

courses in higher m

conditions for thrivin

of significant choices

city center or in the s

York where she is beg

the process of mutual

success is a matter of

Ella's taste in music an

would be better off, h

an Opera singer. Abe

becomes complex: be

tions, it mandates bo

überhaupt and specific

the contingencies of t

2 Love and Philoso

...Love (cpiMoc) is th

inquiry (epcoTTļcnļ)

Heuristicus, Fragmen

As I have told Abe's

Socrates' report of D

mythological ancestry

beautiful boy, an attr

In a set of quick trans

love from an initial a

possess immortal Beau

proper object. A cru

reproduce or preserve

calls a desire for imm

creativity, in philoso

Beautiful/Good in the

just laws. (209 A, 21 1C

of inquiry that echoe

Ô Springer

This content downloaded from

111.68.96.36 on Thu, 22 Oct 2020 05:32:53 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

346 A. Roity

will also take

moves from t

political expr

focus. (209 A-

lover's desire

3 Love is in the Details

... An ounce of performance is worth pounds of promises. . . It isn't what I do,

but how I do it. It isn't what I say, but how I say it, and how I look when I do it

and say it. Mae West

Diotima's lover moves to ever higher, ever more generic and abstract love, love of

Beauty and the Good. Abe's love also moves him beyond his immediate attraction

to Ella, his desire for her company and affection. If it did not, if all he desired was t

be in her presence, his would be a fantasy of love rather than the real thing. Abe's

love also involves what Frankfurt describes as "a disinterested concern for [her]

flourishing [and] well-being... He "identifies with [Ella and]... take her interests as

his own." In loving Ella, Abe's interests and priorities change (for better or fo

worse) no matter what. His happiness is affected by hers. Without his always being

aware of how much he has changed, her concerns affect his significant choices and

priorities - where he lives, his choice of a profession, his friends and politics, his

recreation and tastes.10

Developing a taste for music or becoming actively interested in politics need not

be caused by his love, as if Abe first found himself loving Ella and then cast abou

finding ways of expressing it by becoming interested in politics and Opera. His lov

is not a psychological event or state, followed by protective care for her well-being

Both his new interests and his active concern for Ella's happiness are constitutive

expressions of his love, rather than effects of his attachment: they grow

simultaneously with his growing love (and vice versa). Like other psychologic

attitudes, it consists in, and is in part identified by its content and characteristic

expression.11

It might seem that in drawing an analogy between Abe's love and that o

Diotima's lover, I have intellectualized and idealized love, claiming that it mandate

considerable focused thinking and deliberation. But as Mae West pungently

9 Plato himself has Socrates describe the Divided Line without introducing the political analysis tha

forms the bulk of the rest of the work. {Republic VI, 509D-513E.) I'll return to the connection between

love and political activism in Sect. 4.

10 See Rorty (1986b).

1 1 The distinction between the causes and constituents of love presupposes a full dress analysis of the

content, structure and dynamics of intentional attitudes that I cannot undertake here. See e.g. Anscomb

(1957), Thalberg (1993), Aquila (1975).

Springer

This content downloaded from

111.68.96.36 on Thu, 22 Oct 2020 05:32:53 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Burdens of Love 347

observed in a somew

pounds of promises."

of everyday life, read

the middle of the nigh

her to hear a perfor

persuading her to see

it... It isn't what I say

Kant may have been t

work of love: the (s

expressed - spontaneou

ing - is typically as in

pervasive, subtle atten

he acts on her behalf

In the best of circum

does on her behalf.

conflict with his, ev

entertaining friends h

in watching late nigh

reasonably sometimes

again. He can fully ac

having to convince hi

4 Love's Conflicts

I would not love thee half so much,

Loved I not Honour more.

Richard Lovelace, "To Lucasta, Going to the Wars"

When things go well, when Abe and Ella are well-matched, their primary interests

are compatible, if not actually identical or complementary. With luck, they can

coordinate their respective occupations and preoccupations reasonably well enough.

However happy their love may be, it is after all only part of their lives. The role it

plays in the total structure and economy of their interests and activities varies: in its

early stages it may be all-consuming. When its patterns are relatively stable, it can

remain in the background of their concerns. Changed as Abe may be by Ella, he

does not become wholly focused on her. He is not a monomaniac. Ella may be the

"love of his life," but she is not his only love. He also loves his ailing parents and

his brother, his work on public radio and the Town Council. He takes their interests

as his own and is actively committed to their thriving: his sense of his well-being is

affected by theirs.

Personal love - the love between parents and children, intimate friends, romantic

love - is only one strand in the rich and complex taxonomy of love that plays a

significant role in a person's priorities. The language of everyday speech is

revealing: "Abe loves going fishing with his brother," "Sam died in the service of

the country he loved," "Laura loved the old home-place," "Arthur loved the

Springer

This content downloaded from

111.68.96.36 on Thu, 22 Oct 2020 05:32:53 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

348 A. Rorty

Tintorettos in

of love varies

loves like the l

(preserving e

distinctive obje

they resemb

attentiveness.13

Abe's love of m

concerns: his e

tastes are chan

falters, his sen

or cause has a

understanding

whether thes

commitment, o

play in the ent

structure and d

examination of

Just as Abe's

objective condi

critical reflect

or political dis

classical music? How should it raise funds? Such reflections affect the details of his

work: it will affect his relation to his colleagues, to the station's financial supporters.

(Similarly Ella's love of singing opera commits her into critical reflection about

how to interpret her role as Brünnhilde: does she represent a benign or malignant

force? Is Wagner using the opera to make a political point? As she interprets the

role, her singing - and perhaps even her voice - changes. Reflecting on the details

of her role, her understanding of - and her relation to - the opera change. Her sense

of the integrity of Opera - and to its cultural and moral impact-change as well.)

12 I am grateful to Bill Ruddick for this example and to Berislav Marusic for objecting that love of causes

and country, activities and professions do not carry the same kind of care and concern of personal love. It

is true, Arthur does not move to Venice or undertake to become a professional art conservationist. But his

love does not just consist in a passing elation during a visit to Venice. For it to be an authentic love rather

than generalized elation, it must be expressed, (as it might be) by his contributing to the Save Venice

Fund and organizing a campaign to prevent the Scuola di san Rocco from selling "The Raising of

Lazarus" to Donald Trump for his private collection. Less dramatically and more subtly, Arthur's love of

Tintoretto would be expressed by changes in his perceptual range, by his increased sensitivity to the

dramas of light and shadows, by his doing some research on Tintoretto's palette and studio.

13 Because I do not understand them, I have omitted two significant directions of love: the love of

God (and God's love of Mankind) described by Augustine (1950, 2002) and the love of Humanity

described by Kant (1996). Augustine thinks the ability to recognize and fulfill the obligation to love

God is itself a gift of grace; Kant believes that fulfilling the duties of the love of Humanity falls to the

rational will.

14 I am grateful to Avner Baz for pointing out that "a commitment to [one's] job is a part of a

commitment to [oneself], while a commitment to one's partner is a commitment to her/him." It's true that

Abe's commitment to Ella is focused on her, rather than on himself as a media consultant, still his

commitment to Ella is an essential part of his self-understanding, to himself-as-loving-Ella.

£) Springer

This content downloaded from

111.68.96.36 on Thu, 22 Oct 2020 05:32:53 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Burdens of Love 349

Being actively engaged

contextualized deliberation about how best to fulfill - and sometimes to revise - its

aims. (I shall return to the re visionary work of love in Sect. 5.)

In loving both Ella and working at NPR, Abe is impelled to yet another level of

critical reflection, one that goes beyond attempting to understand and serve what

best promotes their respective thriving. Loving Ella does not automatically make his

commitment to her happiness his dominant concern, any more than loving his job

makes its demands over-ride his other primary commitments. The fact that their

relative claims on him fluctuate - that their needs for his attention vary - makes his

reflections on his priorities even more complex. Abe's many commitments - his

many loves - stand in a continuous dynamic relation to one another within the entire

configurations of his primary-identity defining interests. Richard Lovelace has his

lover say to his beloved Lucasta as he goes off to war:

True, a new mistress now I chase,

The first foe in the field;

And with a stronger faith embrace

A sword, a horse, a shield.

Yet this inconstancy is such

As thou too shalt adore;

I would not love thee half so much,

Loved I not Honour more.

Faced by a similar choice, E.M. Forster expresses a very different sentiment. "If I

had to choose between betraying my country and betraying my friend, I hope I

should have the gut to betray my country."

The work of love extends beyond that engaged in each individual love: it

involves maintaining the dynamic equilibrium and harmony among the competing

demands of multiple loves. Besides the internal good works that each of Abe's loves

mandate, there is the work of balancing his active engagement among them. In

loving, Ella, music and his work at NPR, Abe is - whether or not he is fully

consciously aware of it - continuously actively assessing and reassessing the

priorities whose satisfaction constitutes his happiness. Since he wants the genuine

objective flourishing of all that he loves, he is effectively trying to determine - and

successfully integrate - their relative importance within a fulfilled eudaimon life.

Because Abe's priorities shift contextually with the contingent concerns of his

loves, the work of prioritizing is never done. Although it is unlikely to be finally

resolved by a careful study of the connection between the Symposium and the

Republic, it is nevertheless a philosophic inquiry into the conditions for eudaimonia,

as it were right on the ground, at a grass level.

Even with the most reflective and sensitive good will, even when their interests

are harmonious and they deliberate well together, Abe and Ella's love may strain

under the weight of its care and concern. The most finely adjusted love can falter if

Ella's singing career takes her Bayreuth for 2 years, or if Abe undertakes the care of

his beloved crack-crazed schizophrenic brother, or if their political loyalties change

radically. That is just on the personal side. The dramas of personal relationships - of

Springer

This content downloaded from

111.68.96.36 on Thu, 22 Oct 2020 05:32:53 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

350 A. Rorty

marriage, frien

scenarios profo

might be affec

degree of surv

individual achi

may heighten a

detailed work o

beyond lovers'

best expression

Suppose Abe an

their differenc

engage Ella in

eudaimonia. At

to improvise w

Exploring and

they may be p

indifferent to

unrequited love

sometimes it c

But as long as h

Sometimes th

overwhelming

Ella's happiness

His own primar

to Ella's needs

continue to lov

can then becom

work for NPR:

station, for ex

concern for pu

attempting to

commitments.

into mutual dis

impervious to t

dramas of trag

5 The Politics of Love

"Philosophers have interpreted love in various ways; the point, however, is for

us to try to bring it about." Andrea Miranda, "A Social History of Love"

As I have told Abe's story so far, it might seem that there is a determinate fact o

the matter about what would best conduce to Ella's eudaimonia; and that in loving

her, Abe is committed to understanding the conditions of her happiness and helpin

her to achieve them. But besides being more mundane and domestic, besid

â Springer

This content downloaded from

111.68.96.36 on Thu, 22 Oct 2020 05:32:53 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Burdens of Love 35 1

remaining relatively co

in its improvisatory dr

object of his love is e

ramified and dynamic,

becomes a poet or legis

instance, a philosophic

a political activist. By c

to construct as well as

discover and adhere t

pattern; they themselv

process of unexpected

Ella's eudaimonia are,

must for instance be m

integrating their intere

life, they continue to

satisfaction constitutes

at the Met, her love of

folk or rap. If they ha

programming, Ella wou

of the Holy Cross. The

change. The adaptive

further determine the

As we cannot choose

loving wisely and well.

by his early experience

affected by the luck o

learns the nuances of h

expression of love from

literature as they repre

in which love is expres

him whether and when

tactful silence or distan

Prone to imitation and

models of the expressi

Someone like Abe can,

appropriateness of co

moral norms; he can re

political and economic

with luck, he can ref

generally, he can revalu

in his political and c

consumer economy aff

15 I am grateful to Richard S

cit. and Benjamin Bagley (2

16 See Held (2006), Haslang

Springer

This content downloaded from

111.68.96.36 on Thu, 22 Oct 2020 05:32:53 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

352 A. Rorty

helpful coopera

marriage, inh

stereotypical r

His being activ

love for Ella... and of his culture.

But we must be careful not to claim too much for love; it does not exhaust the

entire scope of active concern. After all, Abe and Ella have commitments to the care

and well-being of people and causes they do not love. As a dutiful nephew, Abe

undertakes the care of his curmudgeon uncle whose politics and way of life he

despises. As a good citizen Ella is actively concerned about the conditions of the

parks and schools for which she has no particular attachment or affection. They will

do their best to fulfill their obligations because they take it as their duty to do so, like

it or not. As a lover, Abe acts on behalf of Ella's well-being for her sake; for him,

the concerns of love are not a self-imposed moral duty. Like it or not, he acts on her

behalf even when doing so imposes a burden on him, and he does so, as an

expression of his love rather than as a duty imposed by civic concern or

commitment. Abe may continue to be committed to Ella's care and well-being out

of duty even though he has ceased to love her. Ironically, he may be even more self-

exacting and attentive in caring for her out of duty than he was when he loved her.

6 On the Other Hand: Summary Conclusion

One the one hand, I have implied that love is virtually ubiquitous, encompassing

love of professions, places and activities as well as friends and family. On the other

hand, I seem to have made the conditions for its attribution hopelessly stringent,

arguing that love demands challenging care and work. In short, I have tried to show

that we love widely, but rarely wisely and well. I have suggested that certain kinds

of cultural models of love - those presented in highly competitive societies focused

on individual achievement, for instance - may make the work of love difficult. It

might seem that in developing the implications of our authorities' characterization

of love, I have not only idealized its commitments, but also made its work seem so

onerous as to make it appear undesirable.17 After all good-enough love is good

enough: it can be supportive without being self-denying; it can be companionable

without becoming all-encompassing; it can be constructive without being commit-

ted to philosophically based social criticism. Certainly the celebrations of love are

well founded: love brings joy and delight in the reality of another person (a place, an

institution, profession); lovers can be strengthened and enabled, enlarged and

enhanced by their love. For all of that, the upbeat features of love largely depend on

the contingent and continuing mutual compatibility of the lovers, on the luck of the

harmony of their respective modes of thriving in their social-cultural-economic

contexts. The eulogies of love may be so elevated, its commitments so idealized

precisely because its tasks are so difficult.

17 I am grateful to Richard Schmitt and to Robert Frederick for raising this concern.

â Springer

This content downloaded from

111.68.96.36 on Thu, 22 Oct 2020 05:32:53 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Burdens of Love 353

If Kant and Frankfu

distinguished from fa

and detailed care and

conditions for the thr

institution or environ

sometimes revising it

reflection need not t

although it is norma

negotiations of daily

significance. Love is n

when it is well and

eudaimonia. The intrin

distorted expressions.

lived, as well as a guid

after all, on key, an

eudaimonia is among i

References

Anscombe, Elizabeth. 1957. Intention. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Augustine. 1950. The City of God XIV. 7. trans. Marcus Dods, 448-449. New York: Random House.

Augustine. 2002. On the Trinity IX. 2-5, 8, ed. Gareth Matthews, trans. Stephen McKenna, 25-31, 34-35.

Cambridge University Press.

Aquila, Richard E. 1975. Causes and constituents of occurent emotions. The Philosophical Quarterly 25:

346-349.

Badhwar, Neera. 2003. Love. In Practical ethics , ed. H. LaFollette, 42-69. Oxford: Oxford University

Press.

Bagley, Benjamin. 2015. Loving someone in particular. Ethics 125(2): 477-507.

Bowlby, John. 1969/1999. Attachment and loss (vol. 1) (2nd ed.). New York: Basic Books.

Butler, Joseph. Sermon IX.

Emerson, Ralph Waldo. 1841. Love. Essays : First Series.

Frankfurt, Harry. 2001. The dear self. Philosophers Imprint 1(5): 55-78.

Freud, Sigmund. 1947. Contributions to the psychology of love. Freud on war, sex and neurosis , 231.

New York: Arts and Science Press.

Geertz, Clifford, Richard Shweder and Robert Levy. 1984. From the native's point of view. In Culture

theory , ed. Richard Shweder and Robert LeVine, 123-136. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Haslanger, Sally. 2012. Resisting reality : Social construction and social critique. Oxford: Oxford

University Press.

Held, Virginia. 2006. The ethics of care: Personal, political, and global. New York: Oxford University

Press.

Hume, David. Treatise of the human understanding 2.2.9 SB 384-5.

Jollimore, Troy. 2011. Love's vision. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Kant. 1963. Friendship. In Lectures on Ethics, ed. Louis Beck, trans. Louis Infield, 200-209. New York:

Harper and Row.

Kant. 1996. Metaphysics of morals , II, 1.1. 25-30. trans. Mary Gregor, (6:449-6:452) 199-201.

Cambridge University Press.

Kolodny, Nico. 2003. Love as valuing a relationship. The Philosophical Review 11: 135-189.

18 I am grateful to MindaRa

and Ben Sherman for comments.

â Springer

This content downloaded from

111.68.96.36 on Thu, 22 Oct 2020 05:32:53 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

354 A. Rorty

Kraut, Robert. 19

Rorty, Amelie. 198

Midwest Studies

Beacon Press, 19

Rorty, Amelie. (198

it alteration find

Rorty, Amelie. 19

Rosaldo, Renato. 1

Marcus. Berkeley:

Setiya, Kieran. 20

Stocker, Michael.

453-466.

Stocker, Michael. 1979. On desiring the bad: An essay in moral psychology. The Journal of Philosophy

86: 46-83.

Strachey, James, ed. & trans. 1959. Group psychology and the analysis of the ego . New York: Norton.

Thalberg, Irving. 1993. Constituents and causes of emotion and action. The Philosophical Quarterly 23:

137-149.

Velleman, David. 1999. Love as a moral emotion. Ethics 109(2): 338-374.

Springer

This content downloaded from

111.68.96.36 on Thu, 22 Oct 2020 05:32:53 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Five Kinds of SilenceDocument1 pageFive Kinds of SilencewynonajbNo ratings yet

- Learning Exercise 5.9: To Float or Not To FloatDocument2 pagesLearning Exercise 5.9: To Float or Not To FloatZunnel Cortes100% (2)

- Decision Report: (Ethical Breach at Novacib Labs)Document4 pagesDecision Report: (Ethical Breach at Novacib Labs)Pratik SinghNo ratings yet

- Katherine Aumer (Eds.) - The Psychology of Love and Hate in Intimate Relationships-Springer International Publishing (2016) PDFDocument183 pagesKatherine Aumer (Eds.) - The Psychology of Love and Hate in Intimate Relationships-Springer International Publishing (2016) PDFAlicia Sosa100% (1)

- University of Illinois Press, North American Philosophical Publications History of Philosophy QuarterlyDocument15 pagesUniversity of Illinois Press, North American Philosophical Publications History of Philosophy Quarterly321876No ratings yet

- What Is FriendshipDocument21 pagesWhat Is FriendshipMuhammad Dilawar HayatNo ratings yet

- Love PDFDocument30 pagesLove PDFbharathNo ratings yet

- The Concept of Love in Dostoyevsky's White NightsDocument7 pagesThe Concept of Love in Dostoyevsky's White NightsjohnnyNo ratings yet

- Don't Let The Word Love Define Your LOVE": Ethics of Love and Ethics of FamilyDocument6 pagesDon't Let The Word Love Define Your LOVE": Ethics of Love and Ethics of FamilyMagana JaypeeNo ratings yet

- The Philosophy of Love and Relationship CounsellingDocument24 pagesThe Philosophy of Love and Relationship CounsellingTammy Dunn0% (1)

- Phelan Sethe's Choice: "Beloved" and The Ethics of ReadingDocument17 pagesPhelan Sethe's Choice: "Beloved" and The Ethics of ReadingTinkara Uršič FratinaNo ratings yet

- Wojciech Jerzy Borowiecki1Document5 pagesWojciech Jerzy Borowiecki1Wojciech BorowieckiNo ratings yet

- Sources of Violence in Romantic Relationships; with Psychological and Philosophical Guidance on How to Deal with Them.From EverandSources of Violence in Romantic Relationships; with Psychological and Philosophical Guidance on How to Deal with Them.No ratings yet

- Essay ElementaryDocument2 pagesEssay Elementarycabalmobilesample1No ratings yet

- Love, Intimacy, and RelationshipDocument17 pagesLove, Intimacy, and RelationshipLovely Grace Cajegas100% (1)

- Aihua Shao - Final PaperDocument6 pagesAihua Shao - Final Paperaihua shaoNo ratings yet

- Matthes - Love in Spite ofDocument20 pagesMatthes - Love in Spite ofJulia AbrahamNo ratings yet

- ADP 2 Davis Todd Friendships and Love Relationships 79 - 122Document44 pagesADP 2 Davis Todd Friendships and Love Relationships 79 - 122youngNo ratings yet

- Romantic Research PaperDocument5 pagesRomantic Research Paperpukjkzplg100% (1)

- Essay ElementaryDocument2 pagesEssay Elementarycabalmobilesample1No ratings yet

- Love, Reason, and Romantic Relationships: Scholarworks@UarkDocument60 pagesLove, Reason, and Romantic Relationships: Scholarworks@UarkGray LagolosNo ratings yet

- Thesis Statement On Romantic LoveDocument6 pagesThesis Statement On Romantic LoveAlicia Edwards100% (2)

- Dizi Film KöşesiDocument4 pagesDizi Film KöşesibarknlegendNo ratings yet

- The Power of Platonic Love: A Handbook for Modern RelationshipsFrom EverandThe Power of Platonic Love: A Handbook for Modern RelationshipsNo ratings yet

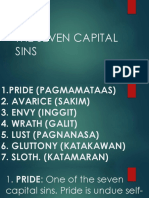

- The Seven Capital SinsDocument89 pagesThe Seven Capital SinsJorea KamaNo ratings yet

- The Meaning of Life - Edited (1) RRDocument6 pagesThe Meaning of Life - Edited (1) RRKafdan KimtaiNo ratings yet

- Phenomenology of Love Term PaperDocument8 pagesPhenomenology of Love Term Paperfnraxlvkg100% (1)

- Bommarito - Inner Virtue - ExcerptsDocument11 pagesBommarito - Inner Virtue - ExcerptsYi ZhangNo ratings yet

- Romantic Love and FriendshipDocument12 pagesRomantic Love and FriendshipThùy DươngNo ratings yet

- Jasmine Gunkel What Is IntimacyDocument38 pagesJasmine Gunkel What Is IntimacyfjxpxbpqkvNo ratings yet

- FFDocument9 pagesFFPen ValkyrieNo ratings yet

- Essay ElementaryDocument2 pagesEssay Elementarycabalmobilesample1No ratings yet

- On Perfect Friendship - An Outline and A Guide To Aristotles PhilDocument74 pagesOn Perfect Friendship - An Outline and A Guide To Aristotles PhilSeymour RodinskyNo ratings yet

- Rebuilding Love as a Couple: Familia, relaciones y sociedadFrom EverandRebuilding Love as a Couple: Familia, relaciones y sociedadNo ratings yet

- Love and Barriers To Love An Analysis For Psychotherapists and OthersDocument17 pagesLove and Barriers To Love An Analysis For Psychotherapists and OthersSaphi SPNo ratings yet

- Marriages Families and Intimate Relationships 4th Edition Williams Solutions Manual 1Document36 pagesMarriages Families and Intimate Relationships 4th Edition Williams Solutions Manual 1nataliecooketmxbrgdkaNo ratings yet

- Research Paper About LoveDocument6 pagesResearch Paper About Lovekpqirxund100% (1)

- WHAT Is LOVE by Isaac Christoher LubogoDocument17 pagesWHAT Is LOVE by Isaac Christoher LubogolubogoNo ratings yet

- Text - The Great Conversation - Aristotle On FriendshipDocument3 pagesText - The Great Conversation - Aristotle On FriendshipKWON BOHYUNNo ratings yet

- Final Love Is Blind EditingDocument47 pagesFinal Love Is Blind EditingMichael WilliamNo ratings yet

- Love Is Blind - EditedDocument10 pagesLove Is Blind - EditedPoet CruzNo ratings yet

- PHR LettersDocument9 pagesPHR Lettersnicolaas.k15No ratings yet

- Friendship Intimacy and HumorDocument14 pagesFriendship Intimacy and Humorammar.alhumoodNo ratings yet

- Why Are Most Guys FriendzonedDocument35 pagesWhy Are Most Guys Friendzonedshauryadhar2016No ratings yet

- Love 3Document7 pagesLove 3Aljhon DelfinNo ratings yet

- We Forge The Conditions of Love: Georgi Gardiner University of TennesseeDocument29 pagesWe Forge The Conditions of Love: Georgi Gardiner University of TennesseesuperveneinceNo ratings yet

- Philosophy Compass - 2014 - Smuts - Normative Reasons For Love Part IDocument11 pagesPhilosophy Compass - 2014 - Smuts - Normative Reasons For Love Part IyoungNo ratings yet

- Thesis About Young LoveDocument4 pagesThesis About Young Loveafcnahwvk100% (1)

- Word 1Document2 pagesWord 1cabalmobilesample1No ratings yet

- Philosophy: 3 Kinds of LoveDocument2 pagesPhilosophy: 3 Kinds of LoveJaenna MacalinaoNo ratings yet

- Erotic Virtue: Res Philosophica October 2015Document22 pagesErotic Virtue: Res Philosophica October 2015limentuNo ratings yet

- Ethics Essay ExampleDocument4 pagesEthics Essay Exampleafabfoilz100% (2)

- GE Elect 2 Lesson 2Document4 pagesGE Elect 2 Lesson 2Krystalline ParkNo ratings yet

- Implicit Personality TheoryDocument20 pagesImplicit Personality TheoryBoboNo ratings yet

- Theo III Morality Human Sexuality Handout 2015Document10 pagesTheo III Morality Human Sexuality Handout 2015Matthew ChenNo ratings yet

- Cultural Determinants of Jealousy: Author's Note: Portions of An Earlier Draft of This Article Were PresentedDocument47 pagesCultural Determinants of Jealousy: Author's Note: Portions of An Earlier Draft of This Article Were PresentedIoni SerbanNo ratings yet

- Essay About MotivationDocument7 pagesEssay About Motivationafabilalf100% (2)

- Frances Berenson, What Is This Thing Colled LoveDocument11 pagesFrances Berenson, What Is This Thing Colled LoveValeriu GherghelNo ratings yet

- 3.3 Attraction and IntimacyDocument40 pages3.3 Attraction and IntimacyAngela YlaganNo ratings yet

- Neil Delaney - Romantic Love and CommitmentDocument19 pagesNeil Delaney - Romantic Love and CommitmentbongofuryNo ratings yet

- Can A Consequentialist Be A True FriendDocument12 pagesCan A Consequentialist Be A True Friendkitty17552100% (1)

- Judicial Affidavit Susan BautistaDocument13 pagesJudicial Affidavit Susan BautistaFrancis DinopolNo ratings yet

- Revision-1-Coded-NSTP 1 - LTS-1-Syllabus-updated SY 22-23Document10 pagesRevision-1-Coded-NSTP 1 - LTS-1-Syllabus-updated SY 22-23Justine LongosNo ratings yet

- Pineda - Lesson 7-9Document6 pagesPineda - Lesson 7-9Joshua PinedaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 7Document4 pagesChapter 7Yogja SinghNo ratings yet

- Student Name(s) Date of Birth/Age Gender (M/F) 1 2 3 4Document5 pagesStudent Name(s) Date of Birth/Age Gender (M/F) 1 2 3 4Javeria AsifNo ratings yet

- General Power of AttorneyDocument9 pagesGeneral Power of AttorneyDon VitoNo ratings yet

- Letter: "Installation of Closed Circuit Television Camera at Muntinlupa Traffic Management Bureau"Document3 pagesLetter: "Installation of Closed Circuit Television Camera at Muntinlupa Traffic Management Bureau"April Delos Reyes TitoNo ratings yet

- 3a.epublit of Tbe Llbflippfnes: Upreme QtourtDocument10 pages3a.epublit of Tbe Llbflippfnes: Upreme QtourtChieNo ratings yet

- Peralihan Hak Atas Tanah Yang Menjadi Objek Sengketa Dalam Perspektif Penegakan HukumDocument26 pagesPeralihan Hak Atas Tanah Yang Menjadi Objek Sengketa Dalam Perspektif Penegakan Hukumdatun kejariNo ratings yet

- Chay Yun Ni (B1900587) Omanisha Sidda (B1900784) Wong Yan Xin (B1900964)Document21 pagesChay Yun Ni (B1900587) Omanisha Sidda (B1900784) Wong Yan Xin (B1900964)Wong Yan XinNo ratings yet

- 1 Succession TSN 2019 2020Document95 pages1 Succession TSN 2019 2020jovelyn davoNo ratings yet

- Step 2: BAS-8 Group 6 - HW2.1: Team AnalysisDocument6 pagesStep 2: BAS-8 Group 6 - HW2.1: Team AnalysisThư NguyễnNo ratings yet

- ICAO SMS Module No 3 Introduction To SMS 2008Document47 pagesICAO SMS Module No 3 Introduction To SMS 2008numanamjad1212No ratings yet

- Military ProfessionalismDocument6 pagesMilitary ProfessionalismJoshua Lander Soquita CadayonaNo ratings yet

- Information Sciences Research Methodology PG (6797) ICT and Engineering Research Methods (9826)Document2 pagesInformation Sciences Research Methodology PG (6797) ICT and Engineering Research Methods (9826)Usama NawazNo ratings yet

- M Flo 000000 Hsog Pro 000043 - 03Document65 pagesM Flo 000000 Hsog Pro 000043 - 03SG LopezNo ratings yet

- Nunes v. LizzaDocument20 pagesNunes v. LizzaLaw&CrimeNo ratings yet

- Guaranty AGREEMENTDocument2 pagesGuaranty AGREEMENTRoy Personal100% (1)

- Pds Form BlankDocument4 pagesPds Form BlankGen EcargNo ratings yet

- Form 2 Ipcr Staff CRDDocument12 pagesForm 2 Ipcr Staff CRDVoltaire BernalNo ratings yet

- Ethics and The Public ServiceDocument23 pagesEthics and The Public ServiceJem SebolinoNo ratings yet

- Nadkarni & Herrmann, 2010Document25 pagesNadkarni & Herrmann, 2010Harshad Vinay SavantNo ratings yet

- 7 Facets of LifeDocument4 pages7 Facets of Liferonan.villagonzaloNo ratings yet

- Critique Paper - The Lottety by ShirleyDocument2 pagesCritique Paper - The Lottety by ShirleyMary Grace MallariNo ratings yet

- Magna Carta Mains 2023Document9 pagesMagna Carta Mains 2023Roshan ShoaibNo ratings yet

- Why The Human Person Is Considered A Moral Agent?Document3 pagesWhy The Human Person Is Considered A Moral Agent?Czarina Mae Quinones TadeoNo ratings yet

- Lab Manual Basic Mechanical Engineering LNCT BhopalDocument237 pagesLab Manual Basic Mechanical Engineering LNCT BhopalDeepakNo ratings yet