Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Advertising Eroticism: Fetishism On Display in Cristina Peri Rossi's "Solitario de Amor" - Christine Hensele

Advertising Eroticism: Fetishism On Display in Cristina Peri Rossi's "Solitario de Amor" - Christine Hensele

Uploaded by

Michael JaimeCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Tarot of The AbyssDocument119 pagesTarot of The Abyssb2linda100% (1)

- Eliade, Mircea - Tales of The Sacred and The Supernatural PDFDocument109 pagesEliade, Mircea - Tales of The Sacred and The Supernatural PDFpooka john100% (4)

- Commedia Dell'arte - Masters, Lovers and Servants: Subverting The Symbolic OrderDocument6 pagesCommedia Dell'arte - Masters, Lovers and Servants: Subverting The Symbolic Ordersmcgehee100% (1)

- Sexual Indifference and Lesbian RepresentationDocument24 pagesSexual Indifference and Lesbian RepresentationA Guzmán MazaNo ratings yet

- Surrealism and The GrotesqueDocument10 pagesSurrealism and The GrotesqueJosh LeslieNo ratings yet

- Barre CombinationDocument3 pagesBarre CombinationAlli ANo ratings yet

- Short Questions FMDocument21 pagesShort Questions FMsultanrana100% (1)

- Dart 381proposal MidtermDocument15 pagesDart 381proposal Midtermapi-298592308No ratings yet

- Existentialism in The Two Gentlemen of VeronaDocument14 pagesExistentialism in The Two Gentlemen of VeronasaimaNo ratings yet

- LHOD and Her HSC English Extension 1 EssayDocument3 pagesLHOD and Her HSC English Extension 1 EssayFrank Enstein FeiNo ratings yet

- Differend Sexual Difference and The SublimeDocument14 pagesDifferend Sexual Difference and The SublimejmariaNo ratings yet

- Final Paper Coen BrothersDocument10 pagesFinal Paper Coen BrothersAndres Nicolas ZartaNo ratings yet

- THE NARRATED AND THE NARRATIVE SELF Examples of Self-Narration in The Contemporary ArtDocument9 pagesTHE NARRATED AND THE NARRATIVE SELF Examples of Self-Narration in The Contemporary ArtPeter Lenkey-TóthNo ratings yet

- Body As The Political Excess PDFDocument11 pagesBody As The Political Excess PDFMariano VelizNo ratings yet

- University of Wisconsin PressDocument19 pagesUniversity of Wisconsin PressSamrat SenguptaNo ratings yet

- Ragland-Sullivan (1991) - 'Psychosis Adumbrated - Lacan and Sublimation of The Sexual Divide in Joyce's 'Exiles''Document17 pagesRagland-Sullivan (1991) - 'Psychosis Adumbrated - Lacan and Sublimation of The Sexual Divide in Joyce's 'Exiles''MikeNo ratings yet

- The Acteon Complex: Gaze, Body, and Rites of Passage in Hedda Gabler'Document22 pagesThe Acteon Complex: Gaze, Body, and Rites of Passage in Hedda Gabler'ipekNo ratings yet

- BJHLZBHDocument4 pagesBJHLZBHHuguesNo ratings yet

- Social Disorganization Theory EssayDocument4 pagesSocial Disorganization Theory Essayafibzdftzaltro100% (2)

- FetishismoDocument10 pagesFetishismo_mirna_No ratings yet

- Christopher S. Wood - Image and ThingDocument22 pagesChristopher S. Wood - Image and ThingSaarthak SinghNo ratings yet

- Adorno SurrealismDocument3 pagesAdorno SurrealismMatthew Noble-Olson100% (1)

- Sk-Interfaces: Telematic and Transgenic Art'S Post-Digital Turn To MaterialityDocument19 pagesSk-Interfaces: Telematic and Transgenic Art'S Post-Digital Turn To MaterialityCássio GuimarãesNo ratings yet

- Skin As A Performance MaterialDocument18 pagesSkin As A Performance MaterialKirsty SimpsonNo ratings yet

- Afterthoughts On Visual PleasureDocument10 pagesAfterthoughts On Visual PleasureJessie MarvellNo ratings yet

- The Aesthetic Revolution and Its Outcomes, Jacques RanciereDocument19 pagesThe Aesthetic Revolution and Its Outcomes, Jacques RanciereTheoria100% (1)

- Do You Think ThatDocument10 pagesDo You Think ThatDialogue Zone NasarawaNo ratings yet

- OverviewDocument6 pagesOverviewmeghasuresh2002No ratings yet

- Ethical Dilemmas in Theater and FilmDocument3 pagesEthical Dilemmas in Theater and FilmjuanNo ratings yet

- HSC Essays (Recovered)Document7 pagesHSC Essays (Recovered)TylerNo ratings yet

- Transcendence in Infinite Jest - Arpon RaksitDocument5 pagesTranscendence in Infinite Jest - Arpon RaksitdupuytrenNo ratings yet

- Intro To Myth PDFDocument7 pagesIntro To Myth PDFKent HuffmanNo ratings yet

- Defining The Grotesque. An Attempt at SynthesisDocument9 pagesDefining The Grotesque. An Attempt at SynthesisJosé Julio Rodríguez PérezNo ratings yet

- AristotleDocument1 pageAristotleShahzadNo ratings yet

- Androgyny EndSemReportDocument17 pagesAndrogyny EndSemReportDhruv SharmaNo ratings yet

- Kara Keeling, "Looking For M"Document19 pagesKara Keeling, "Looking For M"AJ LewisNo ratings yet

- Seiten Aus 411348922-Georg-Lukacs-Essays-on-Realism-MIT-1981-3Document12 pagesSeiten Aus 411348922-Georg-Lukacs-Essays-on-Realism-MIT-1981-3Jason KingNo ratings yet

- AbolfazDocument9 pagesAbolfazAshu TyagiNo ratings yet

- The University of Chicago PressDocument40 pagesThe University of Chicago PressHanna PatakiNo ratings yet

- Variants of Comic Caricature and Their Relationship To Obsessive-Compulsive PhenomenaDocument22 pagesVariants of Comic Caricature and Their Relationship To Obsessive-Compulsive PhenomenablackbellsNo ratings yet

- André Breton's 1 Manifesto of Surrealism (1924)Document5 pagesAndré Breton's 1 Manifesto of Surrealism (1924)Linh PhamNo ratings yet

- K Black Sylvia 2018Document23 pagesK Black Sylvia 2018Phuong Minh BuiNo ratings yet

- Martin Amis - Time - S ArrowDocument2 pagesMartin Amis - Time - S ArrowAndrea MarTen50% (2)

- Dear Joshua, All My LoveDocument12 pagesDear Joshua, All My LovejtobiasfrancoNo ratings yet

- Blade RunnerDocument3 pagesBlade RunnerDuygu YorganciNo ratings yet

- Narrative Voice in Le GuinDocument14 pagesNarrative Voice in Le Guinivankalinin1982No ratings yet

- Gilman - Black Bodies, White Bodies - Toward An Iconography of Female Sexuality in Late Nineteenth-Century Art, Medicine, and LiteratureDocument40 pagesGilman - Black Bodies, White Bodies - Toward An Iconography of Female Sexuality in Late Nineteenth-Century Art, Medicine, and LiteraturesippycuppinqNo ratings yet

- Surrealism HistoricalDocument6 pagesSurrealism HistoricaliskraNo ratings yet

- 05 Mulvey, Laura - Visual Pleasure and Narrative CinemaDocument7 pages05 Mulvey, Laura - Visual Pleasure and Narrative CinemajawharaNo ratings yet

- Aliens, Androgynes, and AnthropologyDocument11 pagesAliens, Androgynes, and Anthropologyvincentroux135703No ratings yet

- Theatres of The Crisis of The Self Theatres of Metamorphosis Theatres of Self and No-SelfDocument9 pagesTheatres of The Crisis of The Self Theatres of Metamorphosis Theatres of Self and No-SelfMarc van RoonNo ratings yet

- Cocker Surrealist ErranceDocument30 pagesCocker Surrealist ErrancedoragreenissleepyNo ratings yet

- Electra: A Gender Sensitive Study of Plays Based on the Myth: Final EditionFrom EverandElectra: A Gender Sensitive Study of Plays Based on the Myth: Final EditionNo ratings yet

- Existential Movement Presents.../finding Peace in the Face of NothingnessFrom EverandExistential Movement Presents.../finding Peace in the Face of NothingnessNo ratings yet

- Queering Visual Cultures: Re-Presenting Sexual Politics on Stage and ScreenFrom EverandQueering Visual Cultures: Re-Presenting Sexual Politics on Stage and ScreenNo ratings yet

- Summary Of "Postmodernity" By Fredric Jameson: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESFrom EverandSummary Of "Postmodernity" By Fredric Jameson: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESNo ratings yet

- The Children's Revolt Against Structures of Repression in Cristina Peri Rossi's "La Rebelión de Los Niños" (The Rebellion of The Children)Document19 pagesThe Children's Revolt Against Structures of Repression in Cristina Peri Rossi's "La Rebelión de Los Niños" (The Rebellion of The Children)Michael JaimeNo ratings yet

- Estado de Exilio by Cristina Peri RossiDocument4 pagesEstado de Exilio by Cristina Peri RossiMichael JaimeNo ratings yet

- Board of Regents of The University of Oklahoma University of OklahomaDocument7 pagesBoard of Regents of The University of Oklahoma University of OklahomaMichael JaimeNo ratings yet

- Board of Regents of The University of Oklahoma University of OklahomaDocument6 pagesBoard of Regents of The University of Oklahoma University of OklahomaMichael JaimeNo ratings yet

- Springer: Springer Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Computers and The HumanitiesDocument12 pagesSpringer: Springer Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Computers and The HumanitiesMichael JaimeNo ratings yet

- Chronology of Latin American Science FictionDocument64 pagesChronology of Latin American Science FictionMichael JaimeNo ratings yet

- Cities of God? Medieval Urban Forms and Their Christian Symbolism - Keith D. LilleyDocument19 pagesCities of God? Medieval Urban Forms and Their Christian Symbolism - Keith D. LilleyMichael JaimeNo ratings yet

- Los Estudios Sobre La Pobreza en América Latina / Studies On Poverty in Latin America - Carlos Barba SolanoDocument42 pagesLos Estudios Sobre La Pobreza en América Latina / Studies On Poverty in Latin America - Carlos Barba SolanoMichael JaimeNo ratings yet

- Reality, Symbolism, Time, and Space in Medieval World MapsDocument13 pagesReality, Symbolism, Time, and Space in Medieval World MapsMichael JaimeNo ratings yet

- Luis Monguió - Historia de La Novela Mexicana en El Siglo XIXDocument4 pagesLuis Monguió - Historia de La Novela Mexicana en El Siglo XIXMichael JaimeNo ratings yet

- Edward Said - Crisis (En El Orientalismo)Document18 pagesEdward Said - Crisis (En El Orientalismo)Michael JaimeNo ratings yet

- Introduction. The Melitian SchismDocument22 pagesIntroduction. The Melitian SchismMarwa SaiedNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Martial Arts RonelDocument2 pagesFundamentals of Martial Arts RonelRodne Badua RufinoNo ratings yet

- G8 Group - Versatile - Topic - Ethics and Basic Principles Governing An Audit - Leader - MD Emran Mia PDFDocument13 pagesG8 Group - Versatile - Topic - Ethics and Basic Principles Governing An Audit - Leader - MD Emran Mia PDFTanjin keyaNo ratings yet

- A Critical Analysis of The Beatitudes From The Gospel According To LukeDocument10 pagesA Critical Analysis of The Beatitudes From The Gospel According To LukejaketawneyNo ratings yet

- 12cheat Sheet - IntegersDocument2 pages12cheat Sheet - IntegersshagogalNo ratings yet

- METHODS OF TEACHING Lesson 1Document19 pagesMETHODS OF TEACHING Lesson 1Joey Bojo Tromes BolinasNo ratings yet

- Applied Economics Syllabus DeclassifiedDocument4 pagesApplied Economics Syllabus DeclassifiedAl Jay MejosNo ratings yet

- TOEIC - Intermediate Feelings, Emotions, and Opinions Vocabulary Set 6 PDFDocument6 pagesTOEIC - Intermediate Feelings, Emotions, and Opinions Vocabulary Set 6 PDFNguraIrunguNo ratings yet

- S/4 HANA UogradeDocument26 pagesS/4 HANA UogradeRanga nani100% (1)

- Factors Affecting The Promotion To ManagerDocument7 pagesFactors Affecting The Promotion To ManagerJohn PerarpsNo ratings yet

- Strategi Positioning Radio Mandiri 98,3 FM Sebagai Radio News and Business PekanbaruDocument8 pagesStrategi Positioning Radio Mandiri 98,3 FM Sebagai Radio News and Business PekanbaruAlipPervectSeihaNo ratings yet

- Long-Lasting Effects of Distrust in Government and Science On Mental Health Eight Years After The Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant DisasterDocument6 pagesLong-Lasting Effects of Distrust in Government and Science On Mental Health Eight Years After The Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant DisasterIkhtiarNo ratings yet

- Laguna Tayabas Bus Co V The Public Service CommissionDocument1 pageLaguna Tayabas Bus Co V The Public Service CommissionAnonymous byhgZINo ratings yet

- Damodaram Sanjivayya National Law University: Project Title: Case Comment On in Re Bischoffchiem (1948) CH 9Document15 pagesDamodaram Sanjivayya National Law University: Project Title: Case Comment On in Re Bischoffchiem (1948) CH 9Kartik BhargavaNo ratings yet

- Principles of Learning and Motivation p11Document3 pagesPrinciples of Learning and Motivation p11Wilson Jan AlcopraNo ratings yet

- HRM PPT EiDocument7 pagesHRM PPT EiKaruna KsNo ratings yet

- Sherlock Holmes SPECKLED BAND COMPLETE.Document12 pagesSherlock Holmes SPECKLED BAND COMPLETE.Fernanda SerralNo ratings yet

- Storification - The Next Big Content Marketing Trend and 3 Benefits Marketers Shouldn't Miss Out OnDocument3 pagesStorification - The Next Big Content Marketing Trend and 3 Benefits Marketers Shouldn't Miss Out OnKetan JhaNo ratings yet

- Parts of Speech: Powerpoint Presentation OnDocument18 pagesParts of Speech: Powerpoint Presentation OnAgung Prasetyo WibowoNo ratings yet

- SynopsisDocument16 pagesSynopsisMohit Saini100% (1)

- Haemato-Biochemical Observations in Emu PDFDocument2 pagesHaemato-Biochemical Observations in Emu PDFMekala LakshmanNo ratings yet

- Max17201gevkit Max17211xevkitDocument24 pagesMax17201gevkit Max17211xevkitmar_barudjNo ratings yet

- Knowledge Base Article: 000517728:: Dsa-2018-018: Dell Emc Isilon Onefs Multiple Vulnerabilities. (000517728)Document3 pagesKnowledge Base Article: 000517728:: Dsa-2018-018: Dell Emc Isilon Onefs Multiple Vulnerabilities. (000517728)Prakash LakheraNo ratings yet

- CRDI ManualDocument14 pagesCRDI ManualVinAy SoNi80% (5)

- TOAD Getting Started GuideDocument50 pagesTOAD Getting Started Guidesmruti_2012No ratings yet

Advertising Eroticism: Fetishism On Display in Cristina Peri Rossi's "Solitario de Amor" - Christine Hensele

Advertising Eroticism: Fetishism On Display in Cristina Peri Rossi's "Solitario de Amor" - Christine Hensele

Uploaded by

Michael JaimeOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Advertising Eroticism: Fetishism On Display in Cristina Peri Rossi's "Solitario de Amor" - Christine Hensele

Advertising Eroticism: Fetishism On Display in Cristina Peri Rossi's "Solitario de Amor" - Christine Hensele

Uploaded by

Michael JaimeCopyright:

Available Formats

Advertising Eroticism: Fetishism on Display in Cristina Peri Rossi's "Solitario de amor"

Author(s): Christine Henseler

Source: Anales de la literatura española contemporánea, Vol. 25, No. 2 (2000), pp. 479-503

Published by: Society of Spanish & Spanish-American Studies

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/27741482 .

Accessed: 21/05/2013 17:23

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Society of Spanish & Spanish-American Studies is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend

access to Anales de la literatura española contemporánea.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 187.252.134.206 on Tue, 21 May 2013 17:23:17 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ADVERTISING EROTICISM: FETISHISM ON

DISPLAY IN CRISTINA PERI ROSSI'S

SOLITARIO DE AMOR

CHRISTINE HENSELER

Cornell University

Todos somos adictos a algo.

Entre dosis y dioses, s?lo

hay una e de diferencia.

(Peri Rossi, Inmovilidad 53)

It is not new to claim that advertising is a fetishistic

medium nor that it uses the eroticized body to sell its

products, but in the eighties and nineties advertising

has begun to use the body to substitute for the product

itself. Ads that include the nude body do not only sell

lotion, soap, gel, shampoo, or lingerie, but they promote

credit cards, swatch watches, and jeans. As ads move

away from traditional creative devices, they leave the

realm of pure product recognition and point to the way

the body comments on its own construction. A Swatch

watch ad that was published in several women's maga

zines (Downtown and Cosmopolitan among others) in

Spain in 1998 exemplifies this phenomenon. The full

page colored ad consists of a female figure and a swatch

479

This content downloaded from 187.252.134.206 on Tue, 21 May 2013 17:23:17 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

480 ALEC, 25 (2000)

watch. The black (and in other versions white) woman

on the left hand side is seemingly surprised by the

camera's fixative stare. Her arms are crossed and her

left leg is pulled toward her body in an attempt to cover

her nudity. Her fingers are extended in ecstasy and her

body retains the wetness of an afternoon swim. She

wears nothing but a watch. The "Skin" Swatch watch on

the right hand side of the page is reproduced from a

frontal and a side view and practically into

disappears

the white background of the ad. The copy reads: "Estoy

desnuda, ?o no lo estoy?" The readers/viewers of this ad

might answer, "yes and no," and wonder if this is a ques

tion concerning the body or thewatch. While thewatch

seems to fade into the whiteness of the paper and lack

body, the contrast of the black female body on thewhite

surface catches our attention. The watch is naked while

the body is clothedwith the visual power ofviewers' ero

tic desires.

At the same time that the female figure attracts the

sexual gaze of the ad's viewers, the image points to its

own coming into being through the product that it is

selling. The woman in the ad "is" because she is wearing

a swatch watch and the watch "is" because its invisibil

ity?its color and thinness?melts into the body that

wears it. The watch becomes the second skin of the

model and as such reflects a m?tonymie association. In

Cristina Peri Rossi's Solitario de amor, as in this ad, the

text re-presents the female body on different levels in

order to fixate it as the ever-present second skin of the

protagonist (or the viewers). The connection that the

novel establishes with the readers is expanded to include

their imaginary and visual faculties in relation to the

system that constructs the body in- and outside the text.

In other words, the "swatch watch woman" herself is a

This content downloaded from 187.252.134.206 on Tue, 21 May 2013 17:23:17 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CHRISTINE HENSELER 481

m?tonymie representation of the second skin that we, as

viewers, would like to either be or have.

Solitario de amor exposes a process of fetishization

through the limited perspective of an individual whose

existence revolves around the desire for his past lover.

The novel highlights, as did the swatch watch ad, the

erotic dimension of the body and places it at the center

of the text's attention. Because of the sexual and exis

tential effects that the body has on the protagonist, the

female figure becomes the site where linguistic powers

and limits are discussed. The body enters into a perfor

mative dimension in the sense that it intends to repeat

and "normalize"?fixate and make real?the narrator's

experience. But the text disrupts its citational dimen

sion through a performance that is defined by Peggy

Phelan as a "reproduction without repetition" (3), that

is, an act inwhich the body cannot be held down and

fixated into one particular image. The singularity of

Solitario lies in its ability to undermine fetishization

and to redelineate the female body fromwithin the text

that constructs it.

In the work of Cristina Peri Rossi, eroticism is a con

stant. Her books of short stories, Los museos abandona

dos and Una

pasi?n prohibida, her novel Solitario de

amor, and most specifically Fantas?as er?ticas establish

her as one of the most important female writers in this

traditionally male field. For Peri Rossi eroticism is not

disconnected from literature since the latter "es un acto

de amor ... un acto m?s de amor" (P?rez-S?n

complejo

chez 64). Similar to theway fetishismworks, Peri Rossi

believes that "la escritura [es] algo que [tiene] que ver

con la magia" (Riera 20). Less magical and more tech

nical is the manner in which Peri Rossi uses erotic lan

guage to undermine preestablished norms of literary and

political sexual control. Elia Kantaris analyzes Peri

This content downloaded from 187.252.134.206 on Tue, 21 May 2013 17:23:17 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

482 ALEC, 25 (2000)

Rossi's work in light of relations of power and alienation

where male sexual politics are construed around "the

desire to possess, and in particular to monopolize the

means of (re)production" (248). Peri Rossi, he says, uses

incoherence and disjunction as ways of

"fragmentation,

escaping from the 'controlling structures' of repression"

(263). Literature and language, he adds, are for Peri

Rossi the arenas for battles of sexual identity.

In poetry and the novel, short story, and essay, Peri

Rossi escapes the control of erotic identity on both a nar

rative and a thematic level. In her poetic work?espe

cially in Descripci?n de un naufragio, Evoh?, and Lin

g??stica general?her dialectics of desire, as Hugo

Verani calls it,moves through four different stages: di

rect erotic expression, irony and sarcasm, playful abun

dance, and the elevation of desire to mythical propor

tions. In other words, desire becomes the motor ofmen

tal liberation, and the body and theword become loci of

rebellion (Verani 12). Graciela Mantaras Loedel calls

Peri Rossi's erotic exposition in Los museos abandonados

a

momento cenital de la existencia. Toda la plenitud

y la profundidad de lo vivo se asumen en ella y el

eros es siempre un ritual, una liturgia, un ejercicio

de misterio. Por eso,

aunque gozoso y perfecto, no

cabr?a llamarle alegre. En todo caso, su alegr?a es

la que se conquista a trav?s del dolor. Se recupera

as? una vivencia y una visi?n dram?ticas del eros.

(36)

In Una pasi?n prohibida the double edge ofdesire is fur

ther explored. This collection of short stories centers

around the way "identity is constructed or deconstructed

at the borders and limits imposed upon desire" (Kantaris

This content downloaded from 187.252.134.206 on Tue, 21 May 2013 17:23:17 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CHRISTINE HENSELER 483

250). de amor, this same desire

In Solitario crosses the

borders of prohibition to expose itself as such: as pure

desire for a female body. The novel establishes a strong

connection?explored by Graciela Mantaras Loedel and

Gabriela Mora?between the erotic, the aesthetic, and

the linguistic.

Fantas?as er?ticas is perhaps Peri Rossi's most reveal

ing erotic display of ideas. The book consists of a series

of essays ranging from a creative piece that takes place

at a gay bar in Barcelona, to the construction of erotic

fantasies through cross-dressing, to prostitution, blow

up dolls, and male/female objectification. In this tract on

eroticism, Peri Rossi, says Rosemary Geisdorfer Feal,

"breaks with traditional notions of that genre as one

dominated by objectivity, rationality, and suppression of

creative writing and of the fictional imagination. To

write of erotica under the erasure of the erotic imagina

tion is exactly what Peri Rossi has refused to do" (215).

Peri Rossi comes full circle as she exposes the position

that has exiled women from the erotic traditionwhile at

the same time opening the topic to the observers' views.

Just as she does not

separate the female

body erotic

from the person, here she does not disassociate the lan

guage she uses from the topic she treats. Fantas?as er?ti

cas "displaces eroticism from the stranglehold ofmascu

. . .and recirculates it through the principal

linity signs

of power" (Feal 216). Peri Rossi writes what many wo

men have not dared to express because "es evidente que

las mujeres no han querido decirles a los hombres la ver

dad. La verdad la dicen las mujeres en la peluquer?a"

(Riera 24). One might say that Peri Rossi is one of the

major female spokespersons for all that eroticism has

kept secret.

Solitario de amor, as one critic put it, is a story with

out a story. Mantara Loedel refers to an histoire that re

This content downloaded from 187.252.134.206 on Tue, 21 May 2013 17:23:17 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

484 ALEC, 25 (2000)

volves around one axle: the infatuation of an anonymous

male narrator with a woman who has left him. Accord

ing to Peri Rossi, the novel was written in six months,

and only threewords were changed in its published ver

sion (Riera 20). The dominant character-focalizer para

phrases his ex-lover Aida's thoughts and interrupts him

self intermittentlywith the discourse ofhis interlocutor,

Ra?l.1 The internal focalization not only is limiting, but

the protagonist'sanonymity?"no tiene nombre. No tiene

cara, estatura, color de pelo, nacionalidad, padres, pasa

do. Su ser no es otro que ser-amante" (Mantaras 39)?

points to the overall theme of the erotic in this novel as

a closed and individual world that does not allow the

protagonist to conceive of a separate existence.2 The

novel reflects the intensity ofpassion on different levels:

the way inwhich the anonymous character perceives his

love and infatuation with A?da, and the manner inwhich

the narrative closes off other points of view to the eyes

of the readers. The narrative act and narrative tech

nique mirror their thematic counterpart.

The protagonist remembers in order to recapture the

love and passion that he has lost. He rearticulates and

relives his intimate experiences with A?da and thereby

comes to realize the inability ofwords to return him to

his past state of amorous fulfillment. Linda Hutcheon

would call this a work of linguistic metafiction, where

self-reflection leads to a realization of the powers and

the limits of language (23). Peri Rossi's novel is more

than self-critical, however, for language is eroticized

through explicitly sexual encounters and an increasing

amount ofmetaphorical references to Aida's body. When

narrative is eroticized, the body instead of the text be

comes the site where metafictional dimensions are dis

cussed. The movement is similar to that in advertising,

where the eroticized body and the fading recognition of

This content downloaded from 187.252.134.206 on Tue, 21 May 2013 17:23:17 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CHRISTINE HENSELER 485

the product ask the readers to think about the construc

tion of the ad. Both advertising and narrative in this

case are based on fetishism,whereby they place the body

at the center of their visual and textual attention.

Passion on the Page

The psychoanalytical tone that underlies fetishism is

strongly present throughout Solitario.3 Love and desire

are already set in a negative relation to each other

through the two epigraphs that launch the novel. The

first one is an excerpt from a poem by Paul Val?ry: "...

los gestos extra?os /que para matar el Amor /hacen los

amantes." The second one reflects on the novel's under

lying Lacanian discourse: "Amar es dar lo que no se

tiene a quien no es." Instead of placing love within its

all-encompassing myth of fulfillment, these quotations

look at love through a negative and destructive light.

Consequently, the novel, as we shall see, puts not only

the female object of desire?A?da?in the position of the

unattainable (M)other, but it connects the desire for the

body to writing

because the Imaginary "behaves in pre

cisely the same way as language: itmoves ceaselessly on

from object to object or from signifier to signifier, and

will never find full and present satisfaction just as

meaning can never be seized as full presence" (Moi 101).

While such a psychoanalytical interpretation is perti

nent, these two epigraphs lend themselves to a reading

through a consumer lens. In advertising, the quotes by

Val?ry and Lacan comment on a product?desire, love?

that needs to be disrupted and rejected before and after

it is possessed. The product is disembodied in the sense

that it resides within yet without the body?the body

stands in for the product. "Amar es dar lo que no se

tiene"?the object or the subject?"a quien no es": the

This content downloaded from 187.252.134.206 on Tue, 21 May 2013 17:23:17 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

486 ALEC, 25 (2000)

product, in theory, is bought foror given to a person who

identifies with the body in the ad. The ad, as does the

novel, refers to a love that does not physically exist.

Existence and nonexistence play tug-of-war between ges

tures that point to corporeal power and corporeal ab

sence. body and the idea, movement

The and stasis, are

interrelated and transformed into an aberration of con

tinuous desire.

At the end of Solitario de amor, the narrator mate

rializes the process of impossible physical embodiment

through the act ofwriting. In a train on his way to his

mother's house, the protagonist flees fromhis feelings

for A?da, who has ended their relationship. He has just

bought a black notebook inwhich he begins towrite. He

compares the acceleration of the train to an erotic inter

lude, or actually climax, of Aida's. Aida's orgasm comes

about at the same time that the train's speed increases

in velocity and at the moment that a second voice, in

italics, interjects itself into the imaginary consciousness

of the narrator's writing process and recites the Hebrew

saying: "Cuando la pasi?n te ciegue, /v?stete de negro /

y vete a donde nadie te conozca." This same voice, pro

jected on the flowers, horses, and lilies in the field, also

repeats three times "te conocemos" (185). Are perhaps

the readers the subjects of this verb? Are we looking

from the outside in? For the first time in the narrative

of the novel, there is a heightened awareness of the

power that love plays in the protagonist's text. Love

blinds. The narrator cannot see the landscape that is

rapidly passing outside his train window. He therefore

goes where nobody knows him and where biological

vision is unnecessary: he escapes into the text and into

the arms of the readers. What he attempts to do there is

to reli(e)ve his erotic relationship with A?da. The process

may be a painful one, but "el dolor es mi ?ltima manera

This content downloaded from 187.252.134.206 on Tue, 21 May 2013 17:23:17 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CHRISTINE HENSELER 487

de estar con A?da, de serle fiel, de prolongar mi pasi?n"

(179). Not onlywriting but A?da becomes the medium

that allows his being to enter into existence for, "si ella

no me nombra, soy un ser an?nimo" (179). The more

erotic the narration, the closer the pen/penis comes to

fulfilling his disembodied love. The last paragraphs of

the novel suggest that the text that we are holding in

our hands may be the same one that the protagonist be

gins towrite in the train as he slowly loses sight of the

landscape and loses himself in erotic memories of pas

sion on the page.

Embodied Language

The logical sequence of language as an objective out

side field of study now lives in a realm of subjective pas

sions: "el lenguaje debi? de nacer as?, de la pasi?n, no de

la raz?n" (18). Writing is not only related to passion and

to eroticism but is specifically linked to the body. To un

derstand fully this connection, it isworth taking a look

at the trajectory that the protagonist attributes to lan

it erupts out of "una oculta caverna, . . . surge,

guage:

revienta del fondo olvidado de mi infancia, estalla con su

fuerza primigenia" (15, 17). Once it leaves the darkness

of the past, it is associated with the touch of the narrator

before it takes on meaning: "la palpo como quien ha de

(re)conocer antesde nombrar" (17). As the narrator

recognizes A?da's body and turns her moans into pleas

urable cries, language?now literally in his hands?is

portrayed as a medium stripped of all ideological bag

gage:

[A?da es] un desnudo limpio, sin residuos noctur

nos, sin adherencias. Como si siempre estuviera re

ci?n salida del ba?o. Entonces las palabras, las vie

This content downloaded from 187.252.134.206 on Tue, 21 May 2013 17:23:17 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

488 ALEC, 25 (2000)

jas palabras de toda la vida, aparecen, s?bita

mente, ellas tambi?n desnudas, frescas, resplande

cientes, crudas, con toda su potencia, con todo su

peso, desprendidas del uso, en toda su pureza, como

si se hubiera ba?ado en una fuente primigenia. (14

15)

Aida's body functions like a pure sheet of paper that is

being stroked by a fountain pen's pristine ink. As the

protagonist heightens Aida's sexual responses through

his caressing words, he also underlines his own exis

tence and his power at creation: "Nazco entre las s?ba

nas de A?da y conmigo nacen otras palabras, otros soni

dos, muerte y resurrecci?n" (14). The eroticization of

narrative points to the female body and to its sexual per

formance as the site where language evolves and allows

for new meanings. Writing takes on a performative

dimension through eroticization.

Not all descriptions ofAida's body are erotic. On the

contrary, there are moments when conventional lan

guage metamorphoses into scientific definitions of her

organs: "el lenguaje convencional estalla. . . .Cobro una

lucidez repentina acerca del lenguaje .... Nazco y me

despojo de eufemismos; no amo su cuerpo, estoy amando

su h?gado membranoso de imperceptible palpito, la

blanca escler?tica de sus ojos, el endometrio sangrante,

el l?bulo agujereado ..." (15-16). The semimedical lan

guage that the protagonist uses goes beyond the skin in

an exaggerated attempt to penetrate the other's body.

Lucidity is related to a feeling of love that is expressed

beyond metaphors and euphemisms and ever more em

phatically connects passion to language and to the body.

The discourse of love?in its scientific or poetic form?is

the only possible manner of communication for the pro

tagonist because "un habla desenamorada ?me resulta

This content downloaded from 187.252.134.206 on Tue, 21 May 2013 17:23:17 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CHRISTINE HENSELER 489

?tono y harto incomprensible" (56). Lovers, he proclaims,

"se aman en lenguas" (22); while this "lengua" may be a

tongue on his lover's skin or his tongue as it scientifi

cally searches for her most inner and minute particles,

it also refers to the useof language as the primary tool

of amorous communication.

The continuous desire to capture the body inwriting

reflects language's own power and limitations. In adver

tising, this dimension, as I have already mentioned, has

come about through the increase in erotic images ofboth

female and male bodies and the decrease in product

recognition and association. In Solitario the metafic

tional process is linked toA?da and to the naming and

the touching ofher body:

Voy poniendo a las partes de A?da,

nombres soy el

primer hombre, asombrado y azorado, balbuceante,

babeante, bab?lico, y en medio de la confusi?n de

mi nacimiento, inmerso en el misterio, murmuro

sonidos viscerales que (re)conocer. Palpo su cuerpo,

imagen del mundo, y bautizo los ?rganos; emocio

nado, saco palabras como piedras arcaicas y las

instalo en las partes de A?da, como eslabones de mi

ignorancia. (18)

A?da's body stirs up emotions and evokes words that are

born out of prehistory. The past and the present as well

as time and space are conflated. The protagonist has a

dual function in this novel: he is the author of the text

we are reading and the author of the body he sculpts.

The word and the image come together in a simul

taneous process of creation and delineation.

This content downloaded from 187.252.134.206 on Tue, 21 May 2013 17:23:17 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

490 ALEC, 25 (2000)

The Erotic in theField ofVision

The protagonist of Solitario lives, he says, in an in

finite time, a time without past, a time ofwaiting, a time

of obsession, an imaginary time in which he is "separado

del resto del mundo, adherido umbilicalmente al tiempo

s?lo por un estrecho cord?n llamado A?da" (73). To the

question "?Pasa el tiempo?" the narratorgives the

answer: "Instalado en una eternidad fija como un lago de

cristal me vuelvo inmutable, perenne: tengo una sola di

mensi?n, la del espacio. Los poros te miran, te miran las

venas, las arterias y las cavidades." His look turns into

a "contemplaci?n est?tica" (12). Just as the protagonist

might stand in front of the nude A?da, we can imagine

ourselves standing?immobile?in front of a billboard

whose image has captured our libidinal attention to the

fullest. We are in a position of static contemplation

where nothing around us exists but this nude figure

before us and our own look that forms and transforms

our identities in the followingmanner:

Mi mirada (mim?ltiple mirada: temiro desde el

pasado remoto del mar

y de la piedra, del hombre

y de la mujer neol?ticos, del antiguo pez que fuimos

una vez lejana, del volc?n que nos arroj?, de la ma

dera tallada, de la pesca y de la caza; te miro desde

otros que no son enteramente yo y sin embargo; te

miro desde la fr?a lucidez de tumadre y la confusa

pasi?n de tu padre, desde el rencor de tu hermano

y la envidia menoscabante de mis amigas; te miro

desde mi avergonzado macho cabr?o y desde mi

parte de mujer enamorada de otra mujer; te miro

desde la vejez que a veces ?"Estoy cansada," di

ces?asoma en tus orejas, en las arrugas de la fren

This content downloaded from 187.252.134.206 on Tue, 21 May 2013 17:23:17 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CHRISTINE HENSELER 491

te), hipnotizada, la sigue, perruna, hambrienta, pa

siva y paciente. . . . (11-12)

The parenthesis that almost entirelymakes up this

quotation extends the simplicity of a particular, passive,

and patient look to one that transcends times, spaces,

forms, and genders. The public nature of the nude image

in an advertisement?even though it is directed toward

a well-researched target market?presents to a itself

similar range of possible spectators and sexual orienta

tions. Thanks to the importance given to transgressions

in Solitario, what seems like another narrative of a

heterosexual man fetishizing a female body opens itself

up to an erotic display of infinite readers and characters.

Peri Rossi's well-known use of the masculine voice in her

work does not only undermine gender assumptions, but

it takes on a variety of forms, among them a woman in

love with another woman.4

The protagonist exposes his narrative through a con

tinuous interior monologue that does not allow the read

ers to pinpoint any specific time or place or identity. The

anonymity and textual openness reflect the purpose of

the narrative: to capture what is absent, the object of de

is thus generated as

sire; or as Brooks puts it: "narrative

both approach and avoidance, the story of desire that

can never speak its name nor quite attain its

quite

object" (103). This is the same motor that propels the

success of advertising. Both are based on desire. And

both Solitario and advertising place the object at the

center and focus on the body as its narrative

of narration

In each case, the readers/viewers do not have a

plot.

stable and fixed image on which to rest their eyes.

Instead,

This content downloaded from 187.252.134.206 on Tue, 21 May 2013 17:23:17 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

492 ALEC, 25 (2000)

De mirar hemos

pasado a ver mirar y donde antes

la mirada se llenaba con la presencia de un objeto

que tend?a a colmarla, ahora encontramos un espa

cio para el despliegue de acercamientos y distan

cias, de identificaciones y rupturas, de tentaciones

y provocaciones, de intimidaciones y seducciones.

(Zunzunegui 14)

The images are in constant flux; they seduce and tease

our imagination. The interior monologue and textual

openness ofSolitario propel the idea that "el universo de

los anuncios no es tanto 'crear necesidades' cuanto reali

mentar esa carencia profunda que nunca podr? ser col

mada" (Zunzunegui 15). In essence, writing is just that:

the need to put into being that which does not exist.

Both advertising and narrative are therefore fetishistic

and by definition m?tonymie processes: "it is as if the

frustrated attempt to fix the body in the field of vision

set off the restless movement of narrative, telling the

story of approach to, and swerve away from, that final

object of sight that cannot be contemplated" (Brooks

103).

Since the narrator cannot hold ontoA?da's body in the

field of vision, he fetishizes vision as such. When he

looks at A?da's

breasts, he thinks of them as a second

pair of eyes: "Siento que me miras con dos pares de ojos:

los de tu cara que se pasean por mi cuerpo desnudo y los

ojos de tus senos, que buscan el rostro, que examinan mi

boca, mi nariz, la frente, las mejillas" (21). Her blouse

becomes a balcony and her breasts, "curiosos, como mu

jeres, se asoman para mirar hacia afuera, no soportan

mucho tiempo la vida de clausura" (21). Her breasts are

personified into the eyes of a woman who, when covered

with clothes, feels imprisoned and blinded. When this

This content downloaded from 187.252.134.206 on Tue, 21 May 2013 17:23:17 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CHRISTINE HENSELER 493

happens, "s?lo te quedan los ojos de la cara para

mirarme, y yo siento nostalgia por los otros" (21). The

conflation ofAida's breasts with her eyes literally takes

place when the protagonist compares her with a painting

by Ren? Magritte: "Provista s?lo con los ojos de la cara,

A?da es una mujer indiferente: le falta algo, como a las

mujeres de los cuadros de Magritte" (21). The quote

brings tomind Magritte's painting "Le Viol." The image

displays a female face that is replaced by female body

parts: breasts represent the eyes, a navel the nose, and

pubic hair stands for the woman's mouth. In this paint

ing, the female body returns the gaze of which she is the

object and renders that gaze (the sexualized gaze)

absurd. The painting disturbs our imagination because

the nude body stands in for the face, and the eyes of the

female look at us provokingly

figure as if to say: "isn't

this what you really want to see?" In advertising, seeing

is an essential component of consumer identity forma

tion that has come about in the following manner:

de mirar hemos a ver mirar ...

pasado [y el] deseo

que se manifiesta,

por definici?n, como el espacio de

la apetencia inagotable, de la pulsi?n operante por

la serie siempre cambiante de objetos de deseo no

ofrecen m?s que nuevos disfraces para una misma

identidad esencial: la del mismo deseo siempre

igual a s?mismo. (Zunzunegui 14)

The body?when denied a head?becomes a costume for

the look that interpellates the desire of the viewers.

Vision is in constant flux and in constant metamorpho

sis; it displays the differentmanifestations of desire.

Visuality is not about trying to see A?da more clearly

but about increasing the desire. It might seem as if

blindness takes away from corporality, but the substitu

This content downloaded from 187.252.134.206 on Tue, 21 May 2013 17:23:17 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

494 ALEC, 25 (2000)

tion of touch for sight?"No la toco: la palpo con la im

prudencia de un ciego" (16)?gives the body a material

form and an erotic dimension that includes an entire

series of sensations not accessible to the eye. This is

where the path splits: itmoves from eroticism to sexual

ity?sexuality being the tactile consequence of erotic

desire?and from eroticism to idealization?idealization

belonging to the sphere where clear, objective vision has

been obscured by desire (sometimes also called "love").

The protagonist now closes his eyes and displaces the

touched to memory: "Los ciegos no ven: reconocen. Los

ojos sin luz de los ciegos no se dirigen a las cosas o a los

seres?que no ven?, sino a unos modelos ideales, abs

tractos. . . .Los los ciegos no est?n a la altura de

ojos de

los objetos terrenales, sino m?s arriba: en el espacio del

sue?o" (16). The touch then questions the validity of

familiarization and of recognition: "el mensaje de las

manos ... es remitido a la memoria de la especie, a unos

modelos ideales de los cuales el objeto es s?lo una de las

posibles representaciones" (16)?as is the object of desire

(be it the product or the body) in an advertisement.

Blindness allows the narrator to reside in difference and

multiplicity. A?da can be transformed into one of many

materializations of an erotic species.

The narrative technique of the novel reflects the con

nection between blindness and memory. Written in the

first-person present tense that refers to a past mo

ment?what is called the historical

present?the novel

plays with the ambiguity and confusion of the past and

the present, ofA?da and her idealized image. The narra

tordoes this by dividing his vision into two simultaneous

looks: "la aparente que recorre la superficie, y la mirada

del ciego, que remite lomirado a la memoria de la espe

cie" (17). When he touches A?da's breast, "la tierra y su

imagen se acercan progresivamente" (17). He collapses

This content downloaded from 187.252.134.206 on Tue, 21 May 2013 17:23:17 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CHRISTINE HENSELER 495

the two realms thatmake up the text as the site forhis

memory. Past and present are joined in matrimonial

harmony. Or so we think. Until A?da declares?through

the narrator's voice?that she does not want to reside in

anybody's mind: "No quise ser el sue?o de mi primer

amante. ... No ser, tampoco, el sue?o [del

quise

segundo]" (148). The narrator realizes that the onlyway

A?da will love him is ifhe has no dream at all. If this is

the case, the image that he remits tomemory, and there

fore to words, must not exist. He must annihilate the

text itself,his entire fiction and the desire to capture her

through language. What thenwould happen toSolitario

de amor?

Advertising Fetishism

Love does not take place through the annihilation of

the text. The text exists because of the absence of the

loved one. The question then is, how does the protago

nist reclaim his passion if not by capturing her body

through an idealized image? This is where the text

comes full circle back to its epigraphs. The object of de

sire is always once removed because it mentally and

visually resides in the shop window, on the billboard, or

in the magazine ad. The protagonist can come closest to

this object by becoming it; he must reduce himself to a

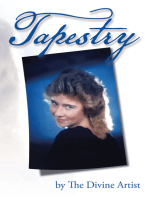

product of desire. The following ad for "Cer?mica Zirco

nio" (see Figure 1, p. 285, courtesy of Delvico Bates)

published in 1988, the same year as Cristina Peri Rossi's

Solitario de amor, shows how he might be able to ap

proach her. The copy reads:

Bella y suave. C?lida y resistente.

Sobria y elegante.

This content downloaded from 187.252.134.206 on Tue, 21 May 2013 17:23:17 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

496 ALEC, 25 (2000)

Es cer?mica Zirconio. Un revestimiento

tan ?ntimo,

adaptable y perfecto como una segunda piel.

La piel de tu casa.

Zirconio. Piel de cer?mica.

The poetic form of the advertising message allows for a

certain degree ofmetaphoric/metonymic liberties. Poetry

becomes the "creative imitation of the sensual" (Kahmen

10). The first two lines create a certain seductive image

of a woman whose soft skin evokes both desire and ele

gant resistance. In effect, the contours of the torso are

very appealing to the eye and create a harmonious com

position through the black and white shading and the

vertical lines of the streched-out arms and legs. This

figure could be thebody of the protagonist's lover inSoli

tario. She is the person whom the narrator is writing

about. The writer ofSolitario is of one identity; "Su ser

no es otro que ser-amante" (Mantaras 39). To insist that

the scriptwriter of the Delvico Bates agency who pro

duced this ad is no other than an anonymous lover-being

would probably not be acceptable?even though he or

she might agree?but one could claim that the ad may be

read as a "ser-amante," a product whose image may be

conceived of as a lover substitute as it tries to fulfillour

imaginary desires through a visual representation.

So, as we sit in a hot, steamy tub filled with scented

bathwater, we may look up and see the image of the sexy

body in the ad reflected on the Zirconio ceramic tiles of

our new and

improved home. In this intimate setting,

the image may be truly adaptable, as the ad says, to the

architecture of our walls or to the preferences of our

imagination. In any case, there it is before us, the per

formance of an ad whose message promised us desire

and fulfillment. We believe we see, through the thicken

This content downloaded from 187.252.134.206 on Tue, 21 May 2013 17:23:17 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CHRISTINE HENSELER 497

ing steam, the female body portrayed on our Zirconio

tiles. But to our dismay, the figure in this ad is not a

perceptible and palpable second skin, as the ad suggests,

but the second skin of our cold bathroom walls, and the

second skin of a tree trunk?in other words, the paper of

themagazines and billboard ads where this image will

forever rest.

Once the image pulls the viewers into the ad or the

narrative through its erotic elements, both men and

women, gay or straight, are themselves in danger of be

coming publicized. We are made aware of the distance

between the body viewed, the body desired, and the body

that exists in real life (as does the narrator). For the

protagonist ofSolitario to close in on the body he sees,

he needs to buy a second skin. This is the onlyway that

he canactually approach A?da since vision can rest

solely on what is not there. To buy a second skin allows

him, he believes, to break down the barrier of distance.

One day, while walking down the street, he sees "un

anuncio en una vitrina [que] muestra a una modelo

cubierta por una malla negra, de nailon, y [se asombra]

de que no sea A?da. [Entra] en la tienda, en seguida, y

[compra] la malla" (122). Thereupon the text exposes a

scene of sexual encounter in which A?da asks him to

cover her: "C?breme ?dice A?da, honda, solemne" (125).

He covers her with his body just like

la malla negra [que] me representa, me simboliza,

ejecuta por m? lo que yo no puedo hacer: no puedo,

aunque quiero, ser nada m?s que un tejido de

nailon bordado, delgado como un hilo, pegado a su

piel. Pero no es otro mi deseo: Quisiera ser la malla,

quisiera ser la tela sobre su cuerpo, no tener m?s

vida ni m?s consistencia que ?sa. Si fuera la malla

This content downloaded from 187.252.134.206 on Tue, 21 May 2013 17:23:17 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

498 ALEC, 25 (2000)

negra, podr?a estar todo el tiempo sobre su piel,

ci??ndola, de los pies al escote. (124)

His sexual act and body stand in for the clothing piece

that he can never be. He knows that the only way for

him to seduce the body on paper, the same body that he

iswriting about and the same body that he is creating

and seducing through vision, is by actually being the

product which the body stands in for in the ad. Adver

tising, says Zunzunegui, "se descubre como un guante

que se ajusta a la perfecci?n a la piel de una sociedad

que, de represora del cuerpo y sus pulsiones, ha pasado

a glorificadora de la dimensi?n sensible de la experien

cia" (6). Similar to this definition of advertising, the pro

tagonist desires tofit the female body like a glove. To his

dismay, his lover pushes him away and resists being

covered by thismale skin "como si la ropa [para A?da]

fuera una segunda piel, inc?moda, un disfraz levemente

opuesto. El vestido es la interdicci?n" (22). A?da rejects

being clothed. She rejects that her visually exposed body

be covered by the product itpromotes. Her nudity in this

case represents her liberation.

When we push the analogy between the "Piel de Cer?

mica" ad and Solitario a littlebit farther,we see that the

protagonist becomes the key that opens the door to the

house. At the beginning of the novel the narrator wishes

to constructAida a home inwhich to live, a home that is

"acogedora como el vientre de una madre" (25). Like the

second skin, A?da rejects this proposition and under

mines the viewer by becoming what he wants to place

her in. If he cannot place her in a house, he will turn her

into one: "El sexo de A?da es una cerradura. Intervengo

en ?l como el extranjero dotado de una llave que abre la

puerta para explorar la casa extra?a" (35). By turning

her into a home, he can have access to her since she is

This content downloaded from 187.252.134.206 on Tue, 21 May 2013 17:23:17 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CHRISTINE HENSELER 499

the lock and he is the key that opens the lock. Just as

she rejected him as her "segunda piel," she also rejects

him as "la piel de tu casa" because both are the same on

a metonymical level and both serve to fetishize her.

At the end of the novel, A?da literally denies him

access to her home: "A?da me ha echado de su casa, de su

?tero, de su habitaci?n, de su cuerpo" (169). In the ad for

Cer?mica Zirconio, the product is reduced to a second

skin, and the second skin is equated to the skin of one's

bathroom walls and one's home. In Solitario de amor the

narrator wishes himself to be the product that covers the

body exposed in the ad?the second skin. Only this time

the tile is a piece of clothing and the body isA?da's. The

visually and verbally eroticized body animates, disrupts,

and seduces an always absent other.

When A?da throws the protagonist out of her house

and her life, she cries out: "?Por fin te he parido!" With

this cry she freesherself from the subject who has been

trying to reproduce her, as we have seen, through vari

ous means. The rupture that these last words represent

is the one that cuts the umbilical cord of fetishism. Simi

lar to the way the body resists being fixated through a

mechanical reproduction, she frees herself from the

sexual reproduction of her biological sex. Even though

A?da has no voice in this novel, the fact that the text

evolves because of her decision to end her relationship

with the protagonist makes her agency present. And

even though her body is the principal site of fetishiza

tion, it continuously resists to be fixated. The text re

flects what Peggy Phelan describes in relation to perfor

mativity as a "reproduction without repetition" (3),

whereby A?da's being only resides in the present of her

own nudity. Her figure can never be reproduced or

pinned down into one determinate signification or source

of desire.

This content downloaded from 187.252.134.206 on Tue, 21 May 2013 17:23:17 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

500 ALEC, 25 (2000)

Solitario de amor allows one "to invent a politically

implicated language of cultural interpretation that

somehow desublimates the inherent voyeurism of the

critic's stare"

fixative (Apter 9). Cristina Peri Rossi's

novel points to the erotic performance of the female body

as a site of resistance. What this resistance permits is a

discourse that opens up new possibilities for female

writers in Spain: it allows for language to defy logical

narrative by associating itself with passion, love, and

sexuality. It transgresses time, space, and genders and

propels an infinite display of spectators and writers. It

rewrites the private into the public sphere and gives new

importance to the visual field as an inherent part of the

system that creates and interprets the liberated nude

body. And it shows how erotic language can create and

resist, at the same time and within the same process, an

act of fetishization.

NOTES

1. The "character-focalizer" is not to be confused with a "narrator

focalizer," who, according to Rimmon-Kennan, is linked to an exter

nal focalization.

2. Peri Rossi responds to the statement "Lo que domina Solitario de

amor es la pasi?n" with "Exactamente. Es un mundo cerrado" (Riera

23).

3. My use of fetishism in this article is based on an aesthetic conver

sion of a part for the whole and on the confusion of a representation

for the real thing. The process is one of loss, of desire, and of subli

mation?with obvious Freudian undertones. William Pietz defines

fetishism in the followingmanner: "The fetish is always a meaningful

fixation of a singular event; it is above all a TiistoricaF object, the en

during material form and force of an unrepeatable event" (Apter 3).

What interestsme here is theway fetishism is related tofixation. On

a psychoanalytical level, fixation "refers to the fact that the libido

attaches itself firmly to persons or imagos, that it reproduces a

particular mode of satisfaction, [and] that it retains an organization

This content downloaded from 187.252.134.206 on Tue, 21 May 2013 17:23:17 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CHRISTINE HENSELER 501

that is in accordance with the characteristic structure of one of its

stages of development" (Laplanche and Pontalis 162). While fetish

ism pertains to the product and to the ultimate goal forwhich Soli

tario is being written?to have a representation ofA?da stand in for

A?da herself?fixation comments on the process and the medium used

to fetishize.

4. Helena Antolin Cochrane says that Peri Rossi, "As a woman

and a lesbian . . . not uses to

author, only language thematically

question depictions of the feminine but frequently also deliberately

adopts a masculine voice in order to undermine automatic gender as

sumptions and to challenge her readers who might suppose that one

can linguistically detect the difference between masculine and femi

nine" (98). Antolin Cochrane also states that Peri Rossi uses the

masculine voice because any other "would be to narrow the potential

identification and empathy with the novel's content" (100). The

question that remains to be answered is if she uses the masculine

voice for promotional purposes or for conscious subversive intentions

(or both).

WORKS CONSULTED

Antol?n Cochrane, Helena. "Androgynous Voices in the Novels of

Cristina Peri Rossi." Mosaic 30 (1997): 97-114.

Apter, Emily, and William Pietz, eds. Fetishism as Cultural Dis

course. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1993.

Brooks, Peter. Body Work: Objects ofDesire inModern Narrative.

Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard UP, 1993.

Feal, Rosemary Geisdorfer. "Cristina Peri Rossi and the Erotic Ima

gination." Reinterpreting the Spanish American Essay: Women

Writers of the 19th and 20th Centuries. Austin: U ofTexas P,

1995. 215-26.

Hutcheon, Linda. Narcissistic Narrative: The Metafictional Paradox.

Waterloo, Ont.: Wilfrid Laurier UP, 1980.

Kahmen, Volker. Erotic Art Today. Trans. Peter Newmark. Green

wich, Conn.: New York Graphic Society, 1972.

Kantaris, Elia. "The Politics ofDesire: Alienation and Identity in the

Work ofMarta Traba and Cristina Peri Rossi." Forum for

Modern Language Studies 25 (1989): 248-64.

Laplanche, J., and J. B. Pontalis. The Language of Psycho-analysis.

Trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith. New York: Norton, 1973.

This content downloaded from 187.252.134.206 on Tue, 21 May 2013 17:23:17 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

502 ALEC, 25 (2000)

Mantaras Loedel, Graciela. "La obra de Cristina Peri Rossi en la lite

ratura er?tica uruguaya." Cristina Peri Rossi, papeles cr?ticos.

Ed. R?muloCosseetal. Montevideo: Linardi y Risso, 1995.31

45.

Moi, Toril. Sexual/Textual Politics. London: Methuen, 1985.

Mora, Gabriela. "Escritura er?tica: Cristina Peri Rossi y Tununa

Mercado." Carnal Knowledge: Essays on the Flesh, Sex, and

Seuxuality in Hispanic Letters and Film. Ed. Pamela

Bacarisse. Pittsburgh: Tres R?os, 1991. 129-40.

P?rez-S?nchez, Gema. "Cristina Peri Rossi." Hispam?rica 24 (1995):

59-72.

Peri Rossi, Cristina. Descripci?n de un naufragio. Barcelona: Lumen,

1975.

_. Evoh?: poemas er?ticos. Montevideo: Gir?n, 1970.

_. Inmovilidad de los barcos. Vitoria: Bassarai, 1997.

_. Fantas?as er?ticas. Madrid: Temas de Hoy, 1992.

_. Ling??stica general: poemas. Valencia: Prometeo, 1979.

_. Los museos abandonados. Barcelona: Lumen, 1974.

_. Una pasi?n prohibida. Barcelona: Seix Barrai, 1986.

_. Solitario de amor. Barcelona: Grijalbo, 1988.

Phelan, Peggy. Unmarked: The Politics of Performance. London:

Routledge, 1993.

Riera, Miguel. "Cristina Peri Rossi: m?dium de s?." Quimera 151

(1996): 15-24.

Rimmon-Kennan, Shlomith. Narrative Fiction: Contemporary Poetics.

London: Routledge, 1983.

Verani, Hugo. "La rebeli?n del cuerpo y el lenguaje." Cristina Peri

Rossi, papeles cr?ticos. Ed. R?mulo Cosse et al. Montevideo:

Linardi y Risso, 1995. 9-21.

Zunzunegui, Santos. Desear el deseo: publicidad, consumo y compor

tamiento. Bilbao: Universidad del Pa?s Vasco, 1990.

This content downloaded from 187.252.134.206 on Tue, 21 May 2013 17:23:17 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

CHRISTINE HENSELER 503

ill

III!'

Figure 1

This content downloaded from 187.252.134.206 on Tue, 21 May 2013 17:23:17 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Tarot of The AbyssDocument119 pagesTarot of The Abyssb2linda100% (1)

- Eliade, Mircea - Tales of The Sacred and The Supernatural PDFDocument109 pagesEliade, Mircea - Tales of The Sacred and The Supernatural PDFpooka john100% (4)

- Commedia Dell'arte - Masters, Lovers and Servants: Subverting The Symbolic OrderDocument6 pagesCommedia Dell'arte - Masters, Lovers and Servants: Subverting The Symbolic Ordersmcgehee100% (1)

- Sexual Indifference and Lesbian RepresentationDocument24 pagesSexual Indifference and Lesbian RepresentationA Guzmán MazaNo ratings yet

- Surrealism and The GrotesqueDocument10 pagesSurrealism and The GrotesqueJosh LeslieNo ratings yet

- Barre CombinationDocument3 pagesBarre CombinationAlli ANo ratings yet

- Short Questions FMDocument21 pagesShort Questions FMsultanrana100% (1)

- Dart 381proposal MidtermDocument15 pagesDart 381proposal Midtermapi-298592308No ratings yet

- Existentialism in The Two Gentlemen of VeronaDocument14 pagesExistentialism in The Two Gentlemen of VeronasaimaNo ratings yet

- LHOD and Her HSC English Extension 1 EssayDocument3 pagesLHOD and Her HSC English Extension 1 EssayFrank Enstein FeiNo ratings yet

- Differend Sexual Difference and The SublimeDocument14 pagesDifferend Sexual Difference and The SublimejmariaNo ratings yet

- Final Paper Coen BrothersDocument10 pagesFinal Paper Coen BrothersAndres Nicolas ZartaNo ratings yet

- THE NARRATED AND THE NARRATIVE SELF Examples of Self-Narration in The Contemporary ArtDocument9 pagesTHE NARRATED AND THE NARRATIVE SELF Examples of Self-Narration in The Contemporary ArtPeter Lenkey-TóthNo ratings yet

- Body As The Political Excess PDFDocument11 pagesBody As The Political Excess PDFMariano VelizNo ratings yet

- University of Wisconsin PressDocument19 pagesUniversity of Wisconsin PressSamrat SenguptaNo ratings yet

- Ragland-Sullivan (1991) - 'Psychosis Adumbrated - Lacan and Sublimation of The Sexual Divide in Joyce's 'Exiles''Document17 pagesRagland-Sullivan (1991) - 'Psychosis Adumbrated - Lacan and Sublimation of The Sexual Divide in Joyce's 'Exiles''MikeNo ratings yet

- The Acteon Complex: Gaze, Body, and Rites of Passage in Hedda Gabler'Document22 pagesThe Acteon Complex: Gaze, Body, and Rites of Passage in Hedda Gabler'ipekNo ratings yet

- BJHLZBHDocument4 pagesBJHLZBHHuguesNo ratings yet

- Social Disorganization Theory EssayDocument4 pagesSocial Disorganization Theory Essayafibzdftzaltro100% (2)

- FetishismoDocument10 pagesFetishismo_mirna_No ratings yet

- Christopher S. Wood - Image and ThingDocument22 pagesChristopher S. Wood - Image and ThingSaarthak SinghNo ratings yet

- Adorno SurrealismDocument3 pagesAdorno SurrealismMatthew Noble-Olson100% (1)

- Sk-Interfaces: Telematic and Transgenic Art'S Post-Digital Turn To MaterialityDocument19 pagesSk-Interfaces: Telematic and Transgenic Art'S Post-Digital Turn To MaterialityCássio GuimarãesNo ratings yet

- Skin As A Performance MaterialDocument18 pagesSkin As A Performance MaterialKirsty SimpsonNo ratings yet

- Afterthoughts On Visual PleasureDocument10 pagesAfterthoughts On Visual PleasureJessie MarvellNo ratings yet

- The Aesthetic Revolution and Its Outcomes, Jacques RanciereDocument19 pagesThe Aesthetic Revolution and Its Outcomes, Jacques RanciereTheoria100% (1)

- Do You Think ThatDocument10 pagesDo You Think ThatDialogue Zone NasarawaNo ratings yet

- OverviewDocument6 pagesOverviewmeghasuresh2002No ratings yet

- Ethical Dilemmas in Theater and FilmDocument3 pagesEthical Dilemmas in Theater and FilmjuanNo ratings yet

- HSC Essays (Recovered)Document7 pagesHSC Essays (Recovered)TylerNo ratings yet

- Transcendence in Infinite Jest - Arpon RaksitDocument5 pagesTranscendence in Infinite Jest - Arpon RaksitdupuytrenNo ratings yet

- Intro To Myth PDFDocument7 pagesIntro To Myth PDFKent HuffmanNo ratings yet

- Defining The Grotesque. An Attempt at SynthesisDocument9 pagesDefining The Grotesque. An Attempt at SynthesisJosé Julio Rodríguez PérezNo ratings yet

- AristotleDocument1 pageAristotleShahzadNo ratings yet

- Androgyny EndSemReportDocument17 pagesAndrogyny EndSemReportDhruv SharmaNo ratings yet

- Kara Keeling, "Looking For M"Document19 pagesKara Keeling, "Looking For M"AJ LewisNo ratings yet

- Seiten Aus 411348922-Georg-Lukacs-Essays-on-Realism-MIT-1981-3Document12 pagesSeiten Aus 411348922-Georg-Lukacs-Essays-on-Realism-MIT-1981-3Jason KingNo ratings yet

- AbolfazDocument9 pagesAbolfazAshu TyagiNo ratings yet

- The University of Chicago PressDocument40 pagesThe University of Chicago PressHanna PatakiNo ratings yet

- Variants of Comic Caricature and Their Relationship To Obsessive-Compulsive PhenomenaDocument22 pagesVariants of Comic Caricature and Their Relationship To Obsessive-Compulsive PhenomenablackbellsNo ratings yet

- André Breton's 1 Manifesto of Surrealism (1924)Document5 pagesAndré Breton's 1 Manifesto of Surrealism (1924)Linh PhamNo ratings yet

- K Black Sylvia 2018Document23 pagesK Black Sylvia 2018Phuong Minh BuiNo ratings yet

- Martin Amis - Time - S ArrowDocument2 pagesMartin Amis - Time - S ArrowAndrea MarTen50% (2)

- Dear Joshua, All My LoveDocument12 pagesDear Joshua, All My LovejtobiasfrancoNo ratings yet

- Blade RunnerDocument3 pagesBlade RunnerDuygu YorganciNo ratings yet

- Narrative Voice in Le GuinDocument14 pagesNarrative Voice in Le Guinivankalinin1982No ratings yet

- Gilman - Black Bodies, White Bodies - Toward An Iconography of Female Sexuality in Late Nineteenth-Century Art, Medicine, and LiteratureDocument40 pagesGilman - Black Bodies, White Bodies - Toward An Iconography of Female Sexuality in Late Nineteenth-Century Art, Medicine, and LiteraturesippycuppinqNo ratings yet

- Surrealism HistoricalDocument6 pagesSurrealism HistoricaliskraNo ratings yet

- 05 Mulvey, Laura - Visual Pleasure and Narrative CinemaDocument7 pages05 Mulvey, Laura - Visual Pleasure and Narrative CinemajawharaNo ratings yet

- Aliens, Androgynes, and AnthropologyDocument11 pagesAliens, Androgynes, and Anthropologyvincentroux135703No ratings yet

- Theatres of The Crisis of The Self Theatres of Metamorphosis Theatres of Self and No-SelfDocument9 pagesTheatres of The Crisis of The Self Theatres of Metamorphosis Theatres of Self and No-SelfMarc van RoonNo ratings yet

- Cocker Surrealist ErranceDocument30 pagesCocker Surrealist ErrancedoragreenissleepyNo ratings yet

- Electra: A Gender Sensitive Study of Plays Based on the Myth: Final EditionFrom EverandElectra: A Gender Sensitive Study of Plays Based on the Myth: Final EditionNo ratings yet

- Existential Movement Presents.../finding Peace in the Face of NothingnessFrom EverandExistential Movement Presents.../finding Peace in the Face of NothingnessNo ratings yet

- Queering Visual Cultures: Re-Presenting Sexual Politics on Stage and ScreenFrom EverandQueering Visual Cultures: Re-Presenting Sexual Politics on Stage and ScreenNo ratings yet

- Summary Of "Postmodernity" By Fredric Jameson: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESFrom EverandSummary Of "Postmodernity" By Fredric Jameson: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESNo ratings yet

- The Children's Revolt Against Structures of Repression in Cristina Peri Rossi's "La Rebelión de Los Niños" (The Rebellion of The Children)Document19 pagesThe Children's Revolt Against Structures of Repression in Cristina Peri Rossi's "La Rebelión de Los Niños" (The Rebellion of The Children)Michael JaimeNo ratings yet

- Estado de Exilio by Cristina Peri RossiDocument4 pagesEstado de Exilio by Cristina Peri RossiMichael JaimeNo ratings yet

- Board of Regents of The University of Oklahoma University of OklahomaDocument7 pagesBoard of Regents of The University of Oklahoma University of OklahomaMichael JaimeNo ratings yet

- Board of Regents of The University of Oklahoma University of OklahomaDocument6 pagesBoard of Regents of The University of Oklahoma University of OklahomaMichael JaimeNo ratings yet

- Springer: Springer Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Computers and The HumanitiesDocument12 pagesSpringer: Springer Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Computers and The HumanitiesMichael JaimeNo ratings yet

- Chronology of Latin American Science FictionDocument64 pagesChronology of Latin American Science FictionMichael JaimeNo ratings yet

- Cities of God? Medieval Urban Forms and Their Christian Symbolism - Keith D. LilleyDocument19 pagesCities of God? Medieval Urban Forms and Their Christian Symbolism - Keith D. LilleyMichael JaimeNo ratings yet

- Los Estudios Sobre La Pobreza en América Latina / Studies On Poverty in Latin America - Carlos Barba SolanoDocument42 pagesLos Estudios Sobre La Pobreza en América Latina / Studies On Poverty in Latin America - Carlos Barba SolanoMichael JaimeNo ratings yet

- Reality, Symbolism, Time, and Space in Medieval World MapsDocument13 pagesReality, Symbolism, Time, and Space in Medieval World MapsMichael JaimeNo ratings yet

- Luis Monguió - Historia de La Novela Mexicana en El Siglo XIXDocument4 pagesLuis Monguió - Historia de La Novela Mexicana en El Siglo XIXMichael JaimeNo ratings yet

- Edward Said - Crisis (En El Orientalismo)Document18 pagesEdward Said - Crisis (En El Orientalismo)Michael JaimeNo ratings yet

- Introduction. The Melitian SchismDocument22 pagesIntroduction. The Melitian SchismMarwa SaiedNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Martial Arts RonelDocument2 pagesFundamentals of Martial Arts RonelRodne Badua RufinoNo ratings yet

- G8 Group - Versatile - Topic - Ethics and Basic Principles Governing An Audit - Leader - MD Emran Mia PDFDocument13 pagesG8 Group - Versatile - Topic - Ethics and Basic Principles Governing An Audit - Leader - MD Emran Mia PDFTanjin keyaNo ratings yet

- A Critical Analysis of The Beatitudes From The Gospel According To LukeDocument10 pagesA Critical Analysis of The Beatitudes From The Gospel According To LukejaketawneyNo ratings yet

- 12cheat Sheet - IntegersDocument2 pages12cheat Sheet - IntegersshagogalNo ratings yet

- METHODS OF TEACHING Lesson 1Document19 pagesMETHODS OF TEACHING Lesson 1Joey Bojo Tromes BolinasNo ratings yet

- Applied Economics Syllabus DeclassifiedDocument4 pagesApplied Economics Syllabus DeclassifiedAl Jay MejosNo ratings yet

- TOEIC - Intermediate Feelings, Emotions, and Opinions Vocabulary Set 6 PDFDocument6 pagesTOEIC - Intermediate Feelings, Emotions, and Opinions Vocabulary Set 6 PDFNguraIrunguNo ratings yet

- S/4 HANA UogradeDocument26 pagesS/4 HANA UogradeRanga nani100% (1)

- Factors Affecting The Promotion To ManagerDocument7 pagesFactors Affecting The Promotion To ManagerJohn PerarpsNo ratings yet

- Strategi Positioning Radio Mandiri 98,3 FM Sebagai Radio News and Business PekanbaruDocument8 pagesStrategi Positioning Radio Mandiri 98,3 FM Sebagai Radio News and Business PekanbaruAlipPervectSeihaNo ratings yet

- Long-Lasting Effects of Distrust in Government and Science On Mental Health Eight Years After The Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant DisasterDocument6 pagesLong-Lasting Effects of Distrust in Government and Science On Mental Health Eight Years After The Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant DisasterIkhtiarNo ratings yet

- Laguna Tayabas Bus Co V The Public Service CommissionDocument1 pageLaguna Tayabas Bus Co V The Public Service CommissionAnonymous byhgZINo ratings yet

- Damodaram Sanjivayya National Law University: Project Title: Case Comment On in Re Bischoffchiem (1948) CH 9Document15 pagesDamodaram Sanjivayya National Law University: Project Title: Case Comment On in Re Bischoffchiem (1948) CH 9Kartik BhargavaNo ratings yet

- Principles of Learning and Motivation p11Document3 pagesPrinciples of Learning and Motivation p11Wilson Jan AlcopraNo ratings yet

- HRM PPT EiDocument7 pagesHRM PPT EiKaruna KsNo ratings yet

- Sherlock Holmes SPECKLED BAND COMPLETE.Document12 pagesSherlock Holmes SPECKLED BAND COMPLETE.Fernanda SerralNo ratings yet

- Storification - The Next Big Content Marketing Trend and 3 Benefits Marketers Shouldn't Miss Out OnDocument3 pagesStorification - The Next Big Content Marketing Trend and 3 Benefits Marketers Shouldn't Miss Out OnKetan JhaNo ratings yet

- Parts of Speech: Powerpoint Presentation OnDocument18 pagesParts of Speech: Powerpoint Presentation OnAgung Prasetyo WibowoNo ratings yet

- SynopsisDocument16 pagesSynopsisMohit Saini100% (1)

- Haemato-Biochemical Observations in Emu PDFDocument2 pagesHaemato-Biochemical Observations in Emu PDFMekala LakshmanNo ratings yet

- Max17201gevkit Max17211xevkitDocument24 pagesMax17201gevkit Max17211xevkitmar_barudjNo ratings yet