Professional Documents

Culture Documents

This Content Downloaded From 52.172.186.233 On Wed, 14 Apr 2021 12:30:47 UTC

This Content Downloaded From 52.172.186.233 On Wed, 14 Apr 2021 12:30:47 UTC

Uploaded by

Amitoz SinghOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

This Content Downloaded From 52.172.186.233 On Wed, 14 Apr 2021 12:30:47 UTC

This Content Downloaded From 52.172.186.233 On Wed, 14 Apr 2021 12:30:47 UTC

Uploaded by

Amitoz SinghCopyright:

Available Formats

The Beauty Myth and Female Consumers: The Controversial Role of Advertising

Author(s): DEBRA LYNN STEPHENS, RONALD PAUL HILL and CYNTHIA HANSON

Source: The Journal of Consumer Affairs , Summer 1994, Vol. 28, No. 1 (Summer 1994),

pp. 137-153

Published by: Wiley

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23859293

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Wiley is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of

Consumer Affairs

This content downloaded from

52.172.186.233 on Wed, 14 Apr 2021 12:30:47 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

SUMMER 1994 VOLUME 28, NUMBER 1 137

DEBRA LYNN STEPHENS, RONALD PAUL HILL,

AND CYNTHIA HANSON

The Beauty Myth and Female Consumers:

The Controversial Role of Advertising

Recently, a small number of consumer researchers have voiced con

cern regarding the question of how and to what degree advertising

involving thin/attractive endorsers is linked with chronic dieting,

body dissatisfaction, and eating disorders in American females. To

explore the broader context of this important and controversial issue,

this paper draws upon a variety of disciplines and suggests directions

for future research. First is a discussion of problems associated with

chronic dieting and the diet industry. Next is an exploration of the

prevalence, concomitants, and origins of body dissatisfaction in

American females. The paper discusses existing advertising research

that gives rise to several important propositions regarding the nature

of the link between advertising and body dissatisfaction. The conclu

sion consists of recommendations for research and a brief discussion

of public policy implications.

Eleven million women and one million men in the United States

suffer from eating disorders—either self-induced semistarvation

(anorexia nervosa) or a cycle of bingeing and purging with laxatives,

self-induced vomiting, or excessive exercise (bulimia nervosa) (Dunn

1992; Fairburn, Cooper, and Cooper 1986).1 A 1990 nationwide

survey of 20 high schools showed that 11 percent of the students have

eating disorders (cited in Dunn 1992). At least nine out of ten eating

disorder sufferers are female (Wolf 1991). According to the Ameri

can Anorexia and Bulimia Association, 150,000 American women

die of anorexia each year (Wolf 1991).

Debra Lynn Stephens is Assistant Professor and Ronald Paul Hill is Professor and Chair

person, College of Commerce and Finance, Villanova University, Villanova, PA. Cynthia

Hanson is Assistant Professor, Division of Business, Greensboro College, Greensboro, NC.

The helpful comments of Morris Holbrook during earlier stages of this research are greatly

appreciated as are the recommendations provided by the reviewers and editor.

The Journal of Consumer Affairs, Vol. 28, No. 1, 1994

0022-0078/0002-137 1.50/0

® 1994 by The American Council on Consumer Interests

'The reason that this manuscript does not address obesity is that there is widespread hesi

tancy among researchers to classify obesity as an eating disorder. This hesitancy stems from

findings indicating that, while anorexia and bulimia are a product of psychological, environ

mental, and cultural factors, obesity is more likely to originate from metabolic and genetic fac

tors (Brownell and Foreyt 1986, 511-512; Sobal and Stunkard 1989). Thus, much of this paper

simply does not apply to the problem of obesity.

This content downloaded from

52.172.186.233 on Wed, 14 Apr 2021 12:30:47 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

138 THE JOURNAL OF CONSUMER AFFAIRS

Research indicates that chronic dieting in th

esteem, adolescent turmoil, and a family his

orders is especially likely to lead to anorexia

1990; Nylander 1971). Most eating-disorder

chronic dieting is, in turn, a direct consequence

on American females to achieve a nearly imp

Biber 1989; Strober 1986). Advertising has b

ing—perhaps even creating—the emaciated s

which girls are taught from childhood to jud

own bodies (Freedman 1984; Nichter and Nic

1992). As Solomon points out, "the pressure t

reinforced both by advertising and by peers.

bombarded by images of thin, happy people

graphic interviews of junior and senior high

"ideal girl" resembles Barbie: 5 feet 6 inches

and "eats whatever she wants and never gain

description of bulimia (Nichter and Nichter 1

Recently, a small number of consumer resea

regarding the question of how and to what de

ing thin/attractive endorsers is linked with chr

satisfaction, and eating disorders in Americ

1987; Richins 1991; Solomon 1992). Richins (1

exposure to ads with highly attractive mode

women's dissatisfaction with their facial and

such exposure does not appear to increase dis

shape in particular. Richins observed that co

ticipated in her study were far less satisfied wi

with their face or overall attractiveness. Thus,

be that "college-age females are already suffic

their bodies that advertising exposure has no

81).

The causality may be reversed: that is, American females with high

levels of body dissatisfaction may respond more positively to prod

ucts in ads featuring physically attractive (hence thin) female endors

ers, when compared to their not-so-dissatisfied counterparts. This

question has not been addressed either theoretically or empirically.

In an attempt to explore the broader context of these important

and controversial issues, this paper draws upon research from a vari

ety of disciplines and suggests directions for future research. First are

a discussion of the diet industry and an examination of the problems

This content downloaded from

52.172.186.233 on Wed, 14 Apr 2021 12:30:47 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

SUMMER 1994 VOLUME 28, NUMBER 1 139

associated with chronic dieting. Next is an explo

lence, concomitants, and origins of body dissatis

females. The paper discusses existing advertising

rise to several important propositions regarding th

between advertising and body dissatisfaction. I

recommendations for research and a brief discus

implications.

FOOD AND DIETING IN AMERICAN CULTURE

Americans share a marked ambivalence toward and preoccu

with food.

On the one hand enjoying rich, luscious, expensive meals is portrayed as a fit

ting reward for hard work, as a way of socializing, and as a way of being sen

sual, indulging a physical appetite. On the other hand, one, especially if that

one is female, is expected to be fit and attractively thin. (Ogletree et al. 1990,

792)

There is an ever expanding repertoire of foods to choose. The crea

tion of a global village has given an unprecedented variety of ethnic

cuisines, and the rise of the middle-class gourmet has resulted in the

crowding of supermarket shelves with a seemingly endless diversity of

flavors and textures in everything from lettuce to ice cream (Brum

berg 1988). More money is spent on food advertising than on most

other products and services in this country; in 1989 the advertising

expenditures of the food industry approached four billion dollars

(Aaker, Batra, and Myers 1992). Food advertisers target people of all

ages, including very young children. For example, food is the focus

of about 60 percent of the commercials shown during Saturday

morning cartoon programming (Ogletree et al. 1990).

The obsessive diet-mindedness of both the editorial content and

advertising in most major women's magazines provides a stark con

trast to this hedonistic attitude toward food (Garner et al. 1980;

Klassen, Wauer, and Cassel 1990-1991). In several such magazines,

even the food advertisements focus more on dieting than on quality

(Klassen, Wauer, and Cassel 1990-1991). Thus there are clear and

quite stringent limits on the degree to which American females may

attempt to satisfy their hedonic impulses toward food. A lean

physique is a sine qua non of physical attractiveness in girls and

women alike (Brumberg 1988; DeJong and Kleck 1986; Franzoi and

This content downloaded from

52.172.186.233 on Wed, 14 Apr 2021 12:30:47 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

140 THE JOURNAL OF CONSUMER AFFAIRS

Herzog 1987). In the words of a Bloomin

womanly shape is "bean lean, slender as

arrow, pencil thin, get the point?" (Fre

This worship of female scrawniness cul

cans' collective taste that began in the e

1980). During the last three decades, fa

pageant contestants, and Playboy center

thinner (Colburn 1992; Garner et al. 198

standard has thinned, the average weig

American women under age 30 has actu

Garner et al. 1980).3 In this widening gulf

and the biological reality, purveyors of

throughout the 1980s, revenues of comm

percent annually, reaching two billion do

clientele are 85 to 90 percent women, m

weight within two years (Sehroeder 1991

Wolf suggests a reason for this instabili

What, finally, is dieting? "Dieting," and, in Gr

trivializing words for what is in fact self-inflicte

of the poorest countries in the world, the very p

ries a day, or 600 more than a Western woman o

1991, 193).

In the Lodz Ghetto in 1941, besieged Jews were allotted starvation rations of

500-1,200 calories a day. At Treblinka, 900 calories was scientifically deter

mined to be the minimum necessary to sustain human functioning. At "the

nation's top weight-loss clinics," where "patients" are treated for up to a

year, the rations are the same (Wolf 1991, 195).

The human body can adapt to a period of caloric restriction by

lowering its basal metabolic rate, so as to conserve energy, glucose,

and protein. There is mounting evidence that when the restriction is

relaxed or lifted metabolic rate may remain below normal, for at least

a few months and perhaps longer (Keys et al. 1950; Kirkley and

Bürge 1989). Thus, when an individual reaches desired low weight

and increases caloric intake, her body may store the added calories as

fat, rather than using them.

2Recent reports from the popular press suggest that this physical "ideal" has negative conse

quences for these women as well ("The Body Game: . . 1993).

3The cause of this change in average weight could reflect changes in body content such as an

increase in the amount of muscle mass among women as a result of the fitness "craze" of the

1980s.

This content downloaded from

52.172.186.233 on Wed, 14 Apr 2021 12:30:47 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

SUMMER 1994 VOLUME 28, NUMBER 1 141

Prolonged semistarvation, whether self-infl

produces a host of symptoms (e.g., irritabili

fatigue, and an obsession with food). Women

below 22 percent commonly experience infert

balances that promote ovarian and endometr

In 1990 the diet industry was hit by a rash of

Weight Loss Center was sued successfully by the

old woman who, while following the plan's low

heart failure as a result of a potassium defici

Nutri/System Inc. and Jenny Craig Inc. were

customers who charged the diets caused gall

strong and Mallory 1992). These lawsuits led

ings on the safety and efficacy of weight-loss

Trade Commission (FTC) has spent the last tw

the promotional efforts of more than a dozen

on claims of long-term efficiency (Miller 1992

Despite these difficulties, the diet industry

1992 sales of diet-related products and service

reached $33 billion (Armstrong and Mallory

tion shows, there is good reason to believe that t

need not worry about dieting becoming pass

future—not when a majority of females asses

how thin they are.

BODY DISSATISFACTION IN AMERICAN FEMALES

Almost as many males as females report being dissatisfi

some aspect of their physique (Cash 1990). However, worr

body weight appear to be a far more common and more im

component of body dissatisfaction experienced by girls and

than that experienced by boys and men (Brumberg 1988; F

Rozin 1985; Rodin, Silberstein, and Striegel-Moore 1985). M

survey data indicate that about one-half to three-quarters of f

who are normal in weight perceive themseives as too heavy,

only about one-quarter of normal weight males consider th

overweight (Blair 1992; Cash 1990; Cash, Winstead, and Jan

This content downloaded from

52.172.186.233 on Wed, 14 Apr 2021 12:30:47 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

142 THE JOURNAL OF CONSUMER AFFAIRS

Klesges 1983; Seligman et al. 1987; Wool

their survey, Cash, Winstead, and Jand

percent of underweight women, compa

underweight men, regarded their weight a

from the Melpomone Institute for Wom

ported that 30 percent of the female p

shape that was 20 percent underweight

chose one that was ten percent underwei

The American female's obsessive, almo

perfect body is both reflected and promot

editorial content of many women's mag

morphoses bordering on the miraculous

comes in a multitude of forms, including

according to one news source "has engen

and another that promises "Buns of Ste

115). She who seeks the perfect body must

tunities to further her quest: "If you drin

tepid, you can burn 10 more calories

[emphasis added]). As discussed in the n

ments and advice to young women nour

with it a disturbing array of psychologi

Concomitants of Body Dissatisfacti

Whether or not they are too heavy, fem

overweight show decreased satisfaction

levels of self-esteem, and lowered psych

pared with males, in general, and with f

themselves overweight (Cash and Hicks

"Normal weight is defined as the range, given a specific

lowest morbidity according to Metropolitan Life Insu

ance Company 1983).

'These surveys ask respondents to report both their we

with it. Studies on the validity of self-reported weight in

their weight by about three pounds (e.g., Tell et al. 1987

tendency to be more pronounced in women than in m

seem to express the consensual view regarding the validi

this magnitude may have little impact on epidemiologi

could have a considerable effect in evaluation of outcome

sizes tend to be small, and mean weight loss limited

tinguish between weight reports and reports of dissatisf

dent may underreport her weight and still express dissa

This content downloaded from

52.172.186.233 on Wed, 14 Apr 2021 12:30:47 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

SUMMER 1994 VOLUME 28, NUMBER 1 143

particularly troubling in light of the fact that b

shows remarkable stability. Formerly overweigh

much dissatisfaction with their physique as tho

weight (Cash, Counts, and Huffine 1990).

Body dissatisfaction in females also appears to encourage dis

turbed eating behaviors. In the survey by Wooley and Wooley (1984),

33,000 females aged 15 to 35 were questioned regarding attitudes

toward their bodies and their methods of weight control. Though

only 25 percent were actually overweight according to weight norms,

75 percent believed that they were fat, with 18 percent using laxatives

or diuretics and 15 percent using forced vomiting to control their

weight. Mintz and Betz (1988) surveyed 643 nonobese, nonanorexic

undergraduate women and found that degree of disturbed eating

depended strongly on level of body dissatisfaction. One-third of their

respondents reported using laxatives or self-induced vomiting at least

once a month for weight-control purposes. Other research suggests

that negative body image predicts severity of eating disturbance more

accurately than other psychological factors including depression,

self-esteem, and psychosocial adjustment (Brown, Cash, and Lewis

1989; Gross and Rosen 1988; Striegel-Moore et al. 1989).

Origins of Female Body Dissatisfaction

This culture's intense preoccupation with weight is undoubtedly

nourished by its stereotype of fat people. Like others classified as

physically unattractive, overweight individuals are expected to be less

intelligent, popular, or outgoing than those who are slimmer. Thus,

according to a review by DeJong and Kleck (1986), heavy individuals

are frequently labeled as lonely, dependent, and greedy for affection.

Moreover, excessive weight is viewed as evidence of a character flaw

associated with self-indulgence or laziness; in short, fat is seen as

"self-induced" (DeJong and Kleck 1986, 74).

This stereotype is one of the "truths." Americans are taught as

young children; as such it so pervades this culture that the individual

never stops to question the assumptions made or to look squarely

upon the thousands of day-to-day cruelties that those assumptions

breed. In their four or five hours a day in front of the television, chil

dren are bombarded with images of thinness-as-beauty, in advertis

ing as well as programs (Nichter and Nichter 1991). As with other

stigmas, many overweight individuals internalize the culture's stereo

This content downloaded from

52.172.186.233 on Wed, 14 Apr 2021 12:30:47 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

144 THE JOURNAL OF CONSUMER AFFAIRS

type starting in early childhood and sp

just with weight, but also with self-bla

Waschull, and Walters 1990; Stager an

Although the fat stereotype seems to

females, the latter are substantially mo

tial explanation for this marked gender d

and boys view their bodies. Researcher

observed that while a boy learns to vi

means of achieving mastery over the

learns that a main function of her body

1968; Freedman 1984; Koff, Rierdan, and Stubbs 1990; Lerner,

Orlos, and Knapp 1976). Children's advertising reflects and but

tresses this lesson. Saturday morning cartoon programming includes

commercials focusing on appearance enhancement, nine out of ten of

which are directed at little girls (Ogletree et al. 1990). Barbie and her

clones join forces with real adult role models—teachers, parents,

older friends, celebrities—to drive the lesson home. As she knows

that she must be thin to be found attractive, puberty-related bodily

changes may be a major blow to a girl's self-esteem. Thus, Freedman

observes that

puberty transforms a girl into a woman without her consent; it betrays her by

making her both more and less feminine at the same time. The hormones that

inflate her breasts, also layer her thighs with "unsightly" fat, and cover her

legs with "superfluous" hair. The size, contours, smells and texture of an

adult woman contradict the soft, sweet childish aspects of feminine beauty

standards emphasized in the media (1984, 36).

In a study of body image among boys and girls aged 11, 13, and 15,

Girgus (1989) illustrates some consequences of this intense preoccu

pation with physical appearance. As girls grow older and their bodies

change, they become increasingly more dissatisfied, consistently

expressing a desire to be thinner. Boys, on the other hand, welcome

bodily changes, viewing them as evidence of muscular development

rather than as signs they are becoming fat. Girgus also indicates that

body dissatisfaction is highly correlated with depression, a malady

that, according to Kandel and Davies (1982), afflicts many more ado

lescent girls than boys. A study by Kaplan, Busner, and Pollack

(1988) lends support to the idea of close interplay among weight,

body dissatisfaction, and depression in teenaged girls. In a survey of

344 junior and senior high school girls, the authors observed signifi

This content downloaded from

52.172.186.233 on Wed, 14 Apr 2021 12:30:47 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

SUMMER 1994 VOLUME 28, NUMBER 1 145

cantly less depression among those who were u

among those whose weight was at or above nor

Women who are very dissatisfied with their ph

ticularly vulnerable to advertising that feature

endorsers or models who exemplify thinness a

feminine beauty. To paint a clearer picture of h

tion might strengthen the persuasiveness of such

on the link between endorser attractiveness and ad

ness must first be examined. Then it will be pos

where body dissatisfaction may come into play.

LINK BETWEEN ENDORSER ATTRACTIVENESS AND AD EFFECTIVENESS

Research on the persuasion process has shown that recipie

persuasive message are often more likely to accept it if they f

communicator or message source to be physically attractive

1986).6 Physical attractiveness of the communicator has bee

to facilitate message acceptance in a wide array of studies diffe

subject population, communication mode, experimental set

message content, and measure of persuasion.

The effect of communicator attractiveness on persuasion

demmonstrated using as subjects male and female high sch

college students (Baker and Churchill 1977; Horai, Nacca

Fatoullah 1974) and nonstudent adults of all ages (Debevec,

den, and Kernan 1986). It occurs both when the communic

physically present as a spokesperson endorsing a view (Chaik

and when she or he is represented in a photograph (Widge

Ruch 1981) or on film (Joseph 1977). Advertisements (K

Homer 1985) as well as advocacy messages (Snyder and Rot

'While a communication source may be perceived as attractive in a number of

respects—for example, as a role model (Kelman 1961) or as a familiar or lika

(McGuire 1969)—this paper focuses exclusively on physical attractiveness. As it

objectively quantifiable trait, level of physical attractiveness is customarily est

"truth of consensus"—that is, by interjudge agreement in ratings of stimulus p

scale that ranges from low to high physical attractiveness (Patzer 1985). This m

measurement is, in Patzer's words, "based on the premise that if a substantial

judges rate a stimulus person as high or low in physical attractiveness, then, for r

poses this stimulus person is interpreted as representative of that respective level

attractiveness" (1985, 17). Indeed, people show remarkable agreement in their ju

others' attractiveness: At the low end is a reliability of r = .49 obtained in a study

752 stimulus persons and four raters (Walster et al. 1966), but typically r value

(Berscheid and Walster 1974; Patzer 1985).

This content downloaded from

52.172.186.233 on Wed, 14 Apr 2021 12:30:47 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

146 THE JOURNAL OF CONSUMER AFFAIRS

1971) have evidenced this link between s

suasion. Further, the link has appeare

(Caballero and Pride 1984; Debevec, Mad

in laboratory contexts (Kahle and Homer 1985; Kamins 1990).

Advertising researchers have found that an attractive model or prod

uct endorser may positively influence the recipient's attitude toward

the ad (Kamins 1990), attitude toward the advertised brand (Kahle

and Homer 1985), purchase intention (Baker and Churchill 1977),

and actual purchase (Caballero and Pride 1984).

It has been suggested that physically attractive individuals tend to

be more persuasive in part because others like them better or credit

them with desirable traits such as sociability, friendliness, warmth,

poise, and kindness (Berscheid and Walster 1974; Chaiken 1986;

Patzer 1985). (Recall the fat-person stereotype discussed previously

for a contrast.) Several of the studies cited provide indirect support

for this speculation. For example, Chaiken (1979) found that attrac

tive communicators were perceived as more likable than unattractive

ones. Debevec, Madden, and Kernan (1986) reported that attractive

ness increased perceived trustworthiness and knowledgeability, both

of which were closely associated with enhanced message evaluations.

Thus, attractive communicators appear to be better at persuading

others, perhaps because they are imbued with socially desirable

traits. However, attractiveness does not matter in all situations. For

example, Joseph (1977) varied communicator expertise as well as

attractiveness and found that while the attractiveness of the non

expert source did affect message acceptance, that of the expert did

not. Kamins (1990) found for both male and female participants, an

attractive male endorser was associated with more positive evalua

tions of an ad for a luxury sports car, but not for ratings of a per

sonal computer ad.

A study by Widgery and Ruch (1981), in which a photo of an

attractive/unattractive "communicator" was coupled with a state

ment that drunken drivers should be jailed, showed a stronger effect

of communicator attractiveness on attitude change in low than in

high Machiavellian individuals. Thus, the impact of source attrac

tiveness on message acceptance may be moderated by other source

characteristics, by the nature of the message theme or product adver

tised, or by attributes of the recipients themselves. The discussion

focuses on how one particular recipient characteristic—body dissatis

faction—might strengthen the influence of source attractiveness on

acceptance of advertising for certain types of products/services.

This content downloaded from

52.172.186.233 on Wed, 14 Apr 2021 12:30:47 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

SUMMER 1994 VOLUME 28, NUMBER 1 147

BODY DISSATISFACTION AND RESPONSES TO ADVERTISING:

DIRECTIONS FOR RESEARCH

It is now possible to focus on the question whether women wh

particularly dissatisfied with their bodies are especially suscepti

persuasion attempts by those whose physical appearances rep

the cultural ideal.7 Research suggests that the question merit

ation. In particular, individuals classified (by themselves or othe

physically unattractive tend to show a reduced ability to res

pressure (Adams 1975, 1977). While fashion models and other

endorsers considered very attractive may not be peers in the eyes of

the "average" female consumer, studies show that male and female

consumers alike use them as standards by which to judge the attrac

tiveness of other, more "ordinary" females (Kenrick and Gutierres

1980; Kenrick, Gutierres, and Goldberg 1989; Richins 1991). For

females, these models constitute an aspirational reference group

(Cocanougher and Bruce 1971). As such, they may play a major part

in many of the product and brand choices of girls and women (Solo

mon 1992). They would be expected to exert influence especially

when the product/service or the results of using it are "socially con

spicuous"—that is, visible to others (e.g., clothing, cosmetics, diet

programs and foods, liposuction surgery) (Bearden and Etzel 1982;

Solomon 1992, 359). It seems plausible that women who are more

dissatisfied with their bodies (and therefore more susceptible to peer

pressure) may be more persuadable by attractive (thin) endorsers of

such products and services. More specifically it is predicted that:

PI. The more dissatisfied a woman is with her body, the more

positively she will evaluate an advertisement for a socially

conspicuous brand, product, or service featuring a physically

attractive female endorser or model.

P2. The more dissatisfied a woman is with her body, the more

positive will be her evaluation of a socially conspicuous

brand, product, or service advertised by a physically attrac

tive endorser.

The Mintz and Betz (1988) study indicates what might motivate a

more positive product, service, or brand evaluation. In their survey

'The extent to which this cultural ideal holds true for important subcultures such as African

Americans and Hispanics has not been addressed in the literature.

This content downloaded from

52.172.186.233 on Wed, 14 Apr 2021 12:30:47 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

148 THE JOURNAL OF CONSUMER AFFAIRS

of the weight-control practices of under

authors found that individuals who used "more serious forms of

weight control" (e.g., laxatives or vomiting) were more likely to be

dissatisfied with their bodies and also to agree with statements

reflecting sociocultural appearance-based stereotypes (such as

"attractive people are more poised and outgoing" or "obese people

are weak-willed and self-indulgent"). This finding indicates that

higher levels of body dissatisfaction are associated with an increased

tendency to attribute socially desirable traits to those who are judged

physically attractive by virtue of being thin. As noted, research indi

cates that such trait attributions may at least partially mediate the

impact of communicator attractiveness on message acceptance.

Thus, Proposition 3 provides an explanation of why more dissatis

fied women might be expected to evaluate a product or brand more

positively if it is advertised by an attractive endorser.

P3. Women who are more dissatisfied with their bodies will be

more likely to ascribe socially desirable traits to a physically

attractive endorser.

The three propositions are illustrated in Figure 1. In sum, it is pre

dicted that women who are especially dissatisfied with their physiques

will be particularly vulnerable to advertising that features representa

tives of the cultural ideal endorsing brands, products, or services that

are socially conspicuous or result in visible changes in appearance.

Studies to test these propositions should use stable measures of

body image and eating-disordered behavior, such as the Eating Dis

orders Inventory (Garner, Olmsted, and Polivy 1983). These

measures could be correlated with measures of the effectiveness of

advertisements involving thin female endorsers. It is important to

FIGURE 1

How Body Dissatisfaction May Affect Responses to Advertisements Featuring

Attractive Models

Body ^ Inferences about ^ Brand

Dissatisfaction

Dissatisfaction —

— ~" —— Model's

""" *T Traits

Model's — —

Traits — —

— —

— —

— —>■ Evaluations

— —Evaluations

I *

I™"™1——Evaluations

Evaluations

Ad

Ad

This content downloaded from

52.172.186.233 on Wed, 14 Apr 2021 12:30:47 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

SUMMER 1994 VOLUME 28, NUMBER 1 149

note that such studies would not provide e

tion between body dissatisfaction and sus

attempts by attractive sources. They would, however, indicate

whether there is an association worth delving into further. As dis

cussed, causality could exist in either—or both—directions.

Research in the immediate future should focus on advertising for

thinness-enhancing products and services as many are potentially

harmful. As previously discussed, there are hazards associated with

diet programs and chronic dieting. Thinness-enhancing surgical tech

niques also carry risks. For example, liposuction, the fastest-growing

cosmetic surgery, was performed on 130,000 American women in

1990; of these, at least 14 died. Intestinal bypass surgery, also per

formed primarily on women, has an even worse track record accord

ing to Wolf.

Intestinal stapling causes 37 possible complications, including severe malnutri

tion, liver damage, liver failure, irregular heartbeat, brain and nerve damage,

stomach cancer, immune deficiency, pernicious anemia, and death. One

patient in ten develops ulcers within six months. Her mortality rate is nine

times above that of an identical person who forgoes surgery; two to four per

cent die within days, and the eventual death toll may be much higher (Wolf

1991, 261).

The procedure was developed for patients more than 100 pounds

overweight, but it has been performed on women weighing as little as

154 (Wolf 1991).

POLICY IMPLICATIONS AND ETHICAL ISSUES

The Federal Trade Commission has a long history of attem

protect vulnerable groups of consumers. This paper suggests th

mental and physical health of young women may be dramatical

negatively impacted by the use of models in advertisements th

the cultural norm for attractiveness/thinness, a stereotype tha

women are unable to attain. Such advertisements may be "

according to the standards set by the FTC (Ford and Calfe

For instance, in the International Harvester case (104 FTC 949,

1062), the Commission noted that "the unfairness statement should

be read as essentially endorsing cost-benefit analysis" (92). Thus, the

Commission looks to see whether the costs derived from an advertis

ing claim outweigh the benefits before acting in the consumers' inter

est. The discussion in this manuscript clearly demonstrates that there

This content downloaded from

52.172.186.233 on Wed, 14 Apr 2021 12:30:47 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

150 the journal of consumer affairs

are substantial costs in terms of

gesting that use of the unfairnes

Of course, additional primary r

order to explore the proposition

others along similar lines. Advertis

beauty stimulates or manipulates

ful models are used to capture the

process advertising messages. In

feminine beauty may act to tem

women and unrealistically suggest

to correct such physical "flaws."

women in this society, the possible

cantly greater.

The Federal Trade Commission c

from this stream of research to aid

rently controversial product cate

that fit this criterion include diet

products such as diet soft drinks

caloric intake. Other less obvious

(e.g., Virginia Slims) and cosmeti

implicit message: "Use our product and you'll be thin!" This

research and regulatory activity may show that the use of more accu

rate and representative portrayals of women in advertisements will

help alleviate this problem, particularly for younger females who are

struggling with new physical and psychological identities as women.

REFERENCES

Aaker, David A., Rajeev Batra, and John G. Myers (1992), Advertising Management,

edition, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Adams, G. R. (1975), "Physical Attributes, Personality Characteristics, and Social Be

An Investigation of the Effects of the Physical Attractiveness Stereotype," unpubl

doctoral dissertation, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Adams, G. R. (1977), "Physical Attractiveness, Personality, and Social Reactions t

Pressure," Journal of Psychology, 96: 287-296.

Armstrong, Larry and Maria Mallory (1992), "The Diet Business Starts Sweating," B

Week (June 22): 22-23.

Baker, Michael J. and Gilbert A. Churchill, Jr. (1977), "The Impact of Physically At

Models on Advertising Evaluations," Journal of Marketing Research, 14: 538-55

Bearden, William O. and Michael J. Etzel (1982), "Reference Group Influences on Pr

and Brand Purchase Decisions," Journal of Consumer Research, 9(2): 183-194.

"However, Congress has acted to limit the FTC's use of the unfairness standard in its regula

tion of advertising during the last decade.

This content downloaded from

52.172.186.233 on Wed, 14 Apr 2021 12:30:47 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

SUMMER 1994 VOLUME 28, NUMBER 1 151

Berscheid, Ellen and Elaine Walster (1974), "Physical Attractivenes

mental Social Psychology, Vol. 7, L. Berkowitz (ed.), New York: Academic Press:

157-215.

Blair, Gwenda (1992), "Eat your heart out, Madonna—I may not have your perfect hard body,

but I'm learning to love the way I look," Self (April): 138-139.

"The Body Game: For Supermodels Kim Alexis, Beverly Johnson, and Carol Alt, Success

Meant a Constant, Gnawing Hunger" (1993), People (January 11): 80-86.

Brown, T. A., T. F. Cash, and R. J. Lewis (1989), "Body Image Disturbances in Adolescent

Female Binge-Purgers: A Brief Report of the Results of a National Survey in the

U.S.A.," Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 30: 605-613.

Brownell, Kelly D. and John P. Foreyt (eds.) (1986), Handbook of Eating Disorders: Physiol

ogy, Psychology, and Treatment of Obesity, Anorexia, and Bulimia, New York: Basic

Books, Inc.

Brumberg, Joan Jacobs (1988), Fasting Girls, Ontario: Penguin Books.

Caballero, Marjorie J. and William M. Pride (1984), "Selected Effects of Salesperson Sex and

Attractiveness in Direct Mail Advertisements," Journal of Marketing, 48: 94-100.

Cash, Thomas F. (1990), "The Psychology of Physical Appearance: Aesthetics, Attributes,

and Images," in Body Images: Development, Deviance, and Change, Thomas F. Cash

and Thomas Pruzinsky (eds.), New York: Guilford Press: 51-71.

Cash, T. F., B. Counts, and C. E. Huffine (1990), "Current and Vestigial Effects of Over

weight Among Women: Fear of Fat, Attitudinal Body Image, and Eating Behaviors,"

Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 12: 157-167.

Cash, Thomas F. and Karen L. Hicks (1990), "Being Fat versus Thinking Fat: Relationships

with Body Image, Eating Behaviors, and Weil-Being," Cognitive Therapy and Research,

14: 327-341.

Cash, Thomas F., Barbara A. Winstead, and Louis H. Janda (1986), "Body Image Survey

Report: The Great American Shape-Up," Psychology Today, 20: 30-37.

Chaiken, Shelly (1979), "Communicator Physical Attractiveness and Persuasion," Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 37: 1387-1397.

Chaiken, Shelly (1986), "Physical Appearance and Social Influence," in Physical Appear

ance, Stigma, and Social Behavior: The Ontario Symposium, Vol. 3, C. Peter Herman,

Mark P. Zanna, and E. Tory Higgins (eds.), Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum: 143-177.

Cocanougher, A. Benton and Grady D. Bruce (1971), "Socially Distant Reference Groups and

Consumer Aspirations," Journal of Marketing Research, 8: 79-81.

Colburn, Don (1992), "The Ideal Female Body? Thin and Getting Thinner," The Washington

Post, Health section (July 28): 5.

Cool, Lisa Collier (1992), "Mirror Image," Fitness (February): 24-26.

Debevec, Kathleen, Thomas J. Madden, and Jerome B. Kernan (1986), "Physical Attractive

ness, Message Evaluation, and Compliance: A Structural Examination," Psychological

Reports, 58: 503-508.

DeJong, William and Robert E. Kleck (1986), "The Social Psychological Effects of Over

weight," m Physical Appearance, Stigma, and Social Behavior: The Ontario Symposium,

Vol. 3, C. Peter Herman, Mark P. Zanna, and E. Tory Higgins (eds.), Hiilsdale, NJ:

Lawrence Erlbaum: 65-87.

Dunn, Don (1992), "When Thinness Becomes Illness," Business Week (August 3): 74-75.

Erikson, E. (1968), Identity: Youth and Crisis, New York: Norton.

Fairburn, Christopher G., Zafra Cooper, and Peter J. Cooper (1986), "The Clinical Features

and Maintenance of Bulimia Nervosa," in Handbook of Eating Disorders: Physiology,

Psychology, and Treatment of Obesity, Anorexia, and Bulimia, Kelly D. Brownell and

John P. Foreyt (eds.), New York: Basic Books, Inc.: 389-404.

Fallon, A. E. and P. Rozin (1985), "Sex Differences in Perceptions of Body Shape," Journal

of Abnormal Psychology, 94: 102-105.

Ford, Gary T. and John E. Calfee (1986), "Recent Developments in FTC Policy on Decep

tion," Journal of Marketing, 50(July): 82-103.

Franzoi, Stephen L. and Mary E. Herzog (1987), "Judging Physical Attractiveness: What

Body Aspects Do We Use?" Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 13: 19-33.

Freedman, Rita (1984), "Reflections on Beauty as It Relates to Health in Adolescent Females,"

Women and Health, 9: 29-45.

This content downloaded from

52.172.186.233 on Wed, 14 Apr 2021 12:30:47 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

152 the journal of consumer affairs

Freedman, Rita (1986), Beauty Bound, Lexingt

Garner, David M., Paul E. Garfinkel, Donald

"Cultural Expectations of Thinness in Wome

Garner, D. M., M. P. Olmsted, and J. Polivy

Multidimensional Eating Disorder Inventory

national Journal of Eating Disorders, 2: 15-3

Girgus, Joan (1989), "Body Image in Girls Push

Turkington in American Psychological Asso

Gross, J. and J. C. Rosen (1988), "Bulimia in A

relates," International Journal of Eating Dis

Harris, Mary B., Stefanie Waschull, and Lauri

Knowledge, and Attitudes of Overweight Wo

1191-1202.

Hesse-Biber, Sharlene (1989), "Eating Patterns and Disorders in a College Population: Are

College Women's Eating Problems a New Phenomenon?" Sex Roles, 20: 71-89.

Horai, Joann, Nicholas Naccari, and Elliott Fatoullah (1974), "The Effects of Expertise and

Physical Attractiveness Upon Opinion Agreement and Liking," Sociometry, 37: 602-606.

Hsu, L. K. G. (1990), Eating Disorders, New York: Guilford Press.

Joseph, W. Benoy (1977), "Effect of Communicator Physical Attractiveness on Opinion

Change and Information Processing," unpublished doctoral dissertation, Ohio State

University, Columbus.

Kahle, Lynn R. and Pamela M. Homer (1985), "Physical Attractiveness of the Celebrity

Endorser: A Social Adaptation Perspective," Journal of Consumer Research, 11:

954-961.

Kamins, Michael A. (1990), "An Investigation into the 'Match-Up' Hypothesis in Celebrity

Advertising: When Beauty May Be Only Skin Deep," Journal of Advertising, 19: 4-13.

Kandel, D. B. and M. Davies (1982), "Epidemiology of Depressive Mood in Adolescents,"

Archives of General Psychiatry, 39: 1205-1212.

Kaplan, S. L., J. Busner, and S. Pollack (1988), "Perceived Weight, Actual Weight, and

Depressive Symptoms in a General Adolescent Sample," International Journal of Eating

Disorders, 7: 107-114.

Kelman, Herbert C. (1961), "Processes of Opinion Change," Public Opinion Quarterly, 25:

57-78.

Kenrick, Douglas T. and Sara E. Gutierres (1980), "Contrast Effects and Judgments of

Physical Attractiveness: When Beauty Becomes a Social Problem," Journal of Personal

ity and Social Psychology, 38: 131-140.

Kenrick, Douglas T., Sara E. Gutierres, and Laurie L. Goldberg (1989), "Influence of Popular

Erotica on Judgments of Strangers and Mates," Journal of Experimental Social Psychol

ogy, 25: 159-167.

Keys, A., J. Brozek, A. Henschel, O. Michelsen, and H. L. Taylor (1950), The Biology of

Human Starvation, Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Kirkley, Betty G. and Jean C. Bürge (1989), "Dietary Restriction in Young Women: Issues and

Concerns," Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 11: 66-72.

Klassen, Michael L., Suzanne M. Wauer, and Sheila Cassel (1990-1991), "Increases in Health

and Weight Loss Claims in Food Advertising in the Eighties," Journal of Advertising

Research (December/January): 32-37.

Klesges, Robert C. (1983), "An Analysis of Body Image Distortions in a Nonpatient Popula

tion," International Journal of Eating Disorders, 2: 35-41.

Koff, Elissa, Jill Rierdan, and Margaret L. Stubbs (1990), "Gender, Body Image, and Self

Concept in Early Adolescence," Journal of Early Adolescence, 10: 56-68.

Lerner, Richard M., James B. Orlos, and John R. Knapp (1976), "Physical Attractiveness,

Physical Effectiveness, and Self-Concept in Late Adolescence," Adolescence, 11:

313-326.

McGuire, William J. (1969), "Nature of Attitudes and Attitude Change," in Handbook of

Social Psychology, G. Lindzey and E. Aronson (eds.), Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Metropolitan Life Insurance Company (1983), Statistical Bulletin, 64: 2-9.

Miller, Cyndee (1992), "Diet Heavyweights Spar With FTC While Trying to KO Competi

tion," Marketing News (October 26): 10.

This content downloaded from

52.172.186.233 on Wed, 14 Apr 2021 12:30:47 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

SUMMER 1994 VOLUME 28, NUMBER 1 153

Mintz, Laurie B. and Nancy E. Betz (1988), "Prevalence and

Behaviors Among Undergraduate Women," Journal of

463-471.

Nichter, Mark and Mimi Nichter (1991), "Hype and Weight," Medical Anthropology, 13:

249-284.

Nylander, I. (1971), "The Feeling of Being Fat and Dieting in a School Population," Acta

Socio-Medica Scandinavia, 1: 17-26.

Ogletree, Shirley M., Sue W. Williams, Paul Raffeld, Bradley Mason, and Kris Fricke (1990),

"Female Attractiveness and Eating Disorders: Do Children's Television Commercials

Play a Role?" Sex Roles, 22: 791-797.

Patzer, Gordon L. (1985), The Physical Attractiveness Phenomenon, New York: Plenum

Press.

Peterson, Robin T. (1987), "Bulimia and Anorexia in an Advertising Context," Journal of

Business Ethics, 6: 495-504.

Richins, Marsha L. (1991), "Social Comparison and the Idealized Images of Advertising,"

Journal of Consumer Research (June): 71-83.

Rodin, J., L. Silberstein, and R. Striegel-Moore (1985), "Women and Weight: A Normative

Discontent," in Psychology and Gender: Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, T. B.

Sonderegger (ed.), Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press: 267-307.

Schroeder, Michael (1991), "The Diet Business Is Getting a Lot Skinnier," Business Week

(June 24): 132-134.

Seid, Roberta Pollack (1989), Never Too Thin: Why Women Are at War with Their Bodies,

New York: Prentice Hall.

Self (1992, April): 115, 147.

Seligman, Jean, Nadine Joseph, Jennifer Donovan, and Mariana Gosnell (1987), "The Littlest

Dieters," Newsweek (July): 48.

Snyder, Mark and Myron Rothbart (1971), "Communicator Attractiveness and Opinion

Change," Canadian Journal of Behavioral Science, 3: 377-387.

Sobal, Jeffery and Albert J. Stunkard (1989), "Socioeconomic Status and Obesity: A Review

of the Literature," Psychological Reports, 105(2): 260-275.

Solomon, Michael R. (1992), Consumer Behavior: Buying, Having, and Being, Boston, MA:

Allyn and Bacon.

Stager, Susan F. and Peter J. Burke (1982), "A Reexamination of Body Build Stereotypes,"

Journal of Research in Personality, 16: 435-446.

Striegel-Moore, R. H., L. R. Silberstein, P. Frensch, and J. Rodin (1989), "A Prospective

Study of Disordered Eating Among College Students," International Journal of Eating

Disorders, 8: 499-509.

Strober, Michael (1986), "Anorexia Nervosa: History and Psychological Concepts," in Hand

book of Eating Disorders: Physiology, Psychology, and Treatment of Obesity, Anorexia,

and Bulimia, Kelly D. Brownell and John P. Foreyt (eds.), New York: Basic Books, Inc.:

231-246.

Tell, Grethe S., Robert Jeffery, F. Matthew Dramer, and Mary K. Snell (1987), "Can Self

Reported Body Weight be Used to Evaluate Long-Term Follow-Up of a Weight-Loss

Program?" Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 87: 1198-1201.

Walster, Elaine, V. Aronson, D. Abrahams, and L. Rottman (1966), "Importance of Physical

Attractiveness in Dating Behavior," Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 4:

508-516.

Widgery, Robin N. and Richard S. Ruch (1981), "Beauty and the Machiavellian," Com

munication Quarterly (Fall): 297-301.

Wolf, Naomi (1991), The Beauty Myth: How Images of Beauty Are Used Against Women,

New York: Anchor Books.

Wooley, Susan and Wayne Wooley (1984), "Feeling Fat in a Thin Society," Glamour (Febru

ary): 198-252.

This content downloaded from

52.172.186.233 on Wed, 14 Apr 2021 12:30:47 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Himena Delgado - Food Synthesis Essay SourcesDocument10 pagesHimena Delgado - Food Synthesis Essay SourcesHimena DelgadoNo ratings yet

- Food Justice A Primer - Saryta RodriguezDocument223 pagesFood Justice A Primer - Saryta RodriguezA Raymundo Despi100% (1)

- Food and Poverty: Food Insecurity and Food Sovereignty among America's PoorFrom EverandFood and Poverty: Food Insecurity and Food Sovereignty among America's PoorNo ratings yet

- Let's Ask Marion: What You Need to Know about the Politics of Food, Nutrition, and HealthFrom EverandLet's Ask Marion: What You Need to Know about the Politics of Food, Nutrition, and HealthRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Student Portal & Mobile Application User ManualDocument23 pagesStudent Portal & Mobile Application User ManualSnehal Singh100% (1)

- Foundations of International Law: History, Nature, Sources, AnswersDocument65 pagesFoundations of International Law: History, Nature, Sources, AnswersGromobranNo ratings yet

- Xthe Relationship Between Media Consumption and Eating DisordersDocument28 pagesXthe Relationship Between Media Consumption and Eating DisordersMaría De Guadalupe ToralesNo ratings yet

- Preventive Medicine: Jerome D. Williams, David Crockett, Robert L. Harrison, Kevin D. ThomasDocument5 pagesPreventive Medicine: Jerome D. Williams, David Crockett, Robert L. Harrison, Kevin D. ThomasFabian StefanNo ratings yet

- Anthropology and Food Policy: Human Dimensions of Food Policy in Africa and Latin AmericaFrom EverandAnthropology and Food Policy: Human Dimensions of Food Policy in Africa and Latin AmericaNo ratings yet

- Wiley Sociological Forum: This Content Downloaded From 85.120.207.252 On Tue, 24 Apr 2018 15:06:24 UTCDocument32 pagesWiley Sociological Forum: This Content Downloaded From 85.120.207.252 On Tue, 24 Apr 2018 15:06:24 UTCBianca GîrleanuNo ratings yet

- Food & Your Health: Selected Articles from Consumers' Research MagazineFrom EverandFood & Your Health: Selected Articles from Consumers' Research MagazineNo ratings yet

- Sociology of Food Security - InsecurityDocument26 pagesSociology of Food Security - Insecuritygiusi.caforio1349No ratings yet

- APA Research Paper SampleDocument7 pagesAPA Research Paper SampleAndrea Pajas Segundo100% (2)

- The Food On Your TableDocument13 pagesThe Food On Your Tableapi-747576312No ratings yet

- A Sociology of Food and EatingDocument6 pagesA Sociology of Food and EatingCeciliaRustoNo ratings yet

- Genetically Altered Foods and Your Health: Food at RiskFrom EverandGenetically Altered Foods and Your Health: Food at RiskRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Breastfeeding Religiosity and Media in The USADocument43 pagesBreastfeeding Religiosity and Media in The USAjoanne_whiteNo ratings yet

- Reconstructing Obesity: The Meaning of Measures and the Measure of MeaningsFrom EverandReconstructing Obesity: The Meaning of Measures and the Measure of MeaningsMegan B. McCulloughNo ratings yet

- Raghunathan 2006Document15 pagesRaghunathan 2006Thư Trần Hoàng AnhNo ratings yet

- Health & Place: Rebekah Fox, Graham SmithDocument10 pagesHealth & Place: Rebekah Fox, Graham Smithsubha005No ratings yet

- WP 2Document13 pagesWP 2api-457920292No ratings yet

- Food Desert Literature ReviewDocument6 pagesFood Desert Literature Reviewea0bvc3s100% (1)

- Warin 2008Document15 pagesWarin 2008CsscamposNo ratings yet

- Tennille Allen. Food Inequalities (2021)Document226 pagesTennille Allen. Food Inequalities (2021)Lorena Peña JiménezNo ratings yet

- The en Cultured Body-BookDocument174 pagesThe en Cultured Body-BooksidorelaNo ratings yet

- Celebrity Vegans and The Lifestyling of Ethical ConsumptionDocument15 pagesCelebrity Vegans and The Lifestyling of Ethical ConsumptionlyzapereiraaNo ratings yet

- Essay On Fast FoodDocument7 pagesEssay On Fast FoodRuslan Lan100% (1)

- Editorial: A Sociology of Food and Eatingwhy Now?Document6 pagesEditorial: A Sociology of Food and Eatingwhy Now?Ivan YvenianNo ratings yet

- Guthman - "If They Only Knew" - Color Blindness and Universalism in California Alternative Food InstitutionsDocument12 pagesGuthman - "If They Only Knew" - Color Blindness and Universalism in California Alternative Food InstitutionsLis Furlani BlancoNo ratings yet

- Final Asharnadeem SynthesispaperDocument17 pagesFinal Asharnadeem Synthesispaperapi-345396720No ratings yet

- Food Security: A Post-Modern PerspectiveDocument16 pagesFood Security: A Post-Modern Perspectivesitizulaika.szNo ratings yet

- Textbook Heavy The Obesity Crisis in Cultural Context 1St Edition Helene A Shugart Ebook All Chapter PDFDocument53 pagesTextbook Heavy The Obesity Crisis in Cultural Context 1St Edition Helene A Shugart Ebook All Chapter PDFkevin.purnell236100% (14)

- Weighty SubjectsDocument17 pagesWeighty SubjectsDaryl Selorm Theodore OWARENo ratings yet

- Unhealthy Food - IMC & PowerDocument18 pagesUnhealthy Food - IMC & PowerWassie GetahunNo ratings yet

- Srs Josephher-1Document24 pagesSrs Josephher-1api-321545357No ratings yet

- World Hunger Research PaperDocument6 pagesWorld Hunger Research Paperofahxdcnd100% (1)

- (Routledge Studies in The Sociology of Health and Illness) Carolyn Mahoney - Health, Food and Social Inequality - Critical Perspectives On The Supply and Marketing of Food-Routledge (2015)Document287 pages(Routledge Studies in The Sociology of Health and Illness) Carolyn Mahoney - Health, Food and Social Inequality - Critical Perspectives On The Supply and Marketing of Food-Routledge (2015)ali hidayatNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Topics Obesity in AmericaDocument5 pagesResearch Paper Topics Obesity in Americagw15ws8j100% (1)

- Food Desert Research PaperDocument6 pagesFood Desert Research Paperzufehil0l0s2100% (1)

- Body ImageDocument18 pagesBody ImagePersephona13No ratings yet

- Media InfluenceDocument16 pagesMedia InfluenceRaudelioMachinNo ratings yet

- Neolib Diet US October SSM 2015 Vol.142Document10 pagesNeolib Diet US October SSM 2015 Vol.142Alvaro Mendonca FiuzaNo ratings yet

- Obesity Research PaperDocument5 pagesObesity Research PaperRyan Washington100% (1)

- Any EssayDocument7 pagesAny Essayafibaubdfmaebo100% (2)

- The Dangers With Health AdvocacyDocument4 pagesThe Dangers With Health Advocacyapi-731474701No ratings yet

- Thesis Obesity in AmericaDocument5 pagesThesis Obesity in Americapatricialeatherbyelgin100% (2)

- 4 Essay QuestionsDocument8 pages4 Essay Questionsdennis ndegeNo ratings yet

- First Page PDFDocument1 pageFirst Page PDFSheila StefaniNo ratings yet

- ObesityDocument8 pagesObesityAreeckans Mathew SNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Childhood ObesityDocument4 pagesLiterature Review Childhood Obesityc5j07dce100% (1)

- Annotated Bibliograpgy - Zach ThomasDocument11 pagesAnnotated Bibliograpgy - Zach Thomasapi-745286430No ratings yet

- The One Best Way?: Breastfeeding History, Politics, and Policy in CanadaFrom EverandThe One Best Way?: Breastfeeding History, Politics, and Policy in CanadaNo ratings yet

- Advertising and Consumerism in The Food IndustryDocument42 pagesAdvertising and Consumerism in The Food IndustryIoana GoiceaNo ratings yet

- Food Poverty - RevisedDocument10 pagesFood Poverty - RevisedP. C. DNo ratings yet

- Unit 4 Reading 1Document4 pagesUnit 4 Reading 1diemquynh210922No ratings yet

- Cross-National NewspapersDocument35 pagesCross-National NewspapersMichelle Ramírez SegoviaNo ratings yet

- Soci 290 Assignment 3Document6 pagesSoci 290 Assignment 3ANA LORRAINE GUMATAYNo ratings yet

- Kompsiko ReviewDocument96 pagesKompsiko ReviewDwinita Ayuni LarasatiNo ratings yet

- Aarogya Setu App - A Test For The Personal Data Protection Bill 2019 - The Law BlogDocument4 pagesAarogya Setu App - A Test For The Personal Data Protection Bill 2019 - The Law BlogAmitoz SinghNo ratings yet

- Nac 26112019 o MP Comm 1692016Document30 pagesNac 26112019 o MP Comm 1692016Amitoz SinghNo ratings yet

- In The High Court of Delhi at New Delhi RFA No. 611/2001 9 March, 2011Document8 pagesIn The High Court of Delhi at New Delhi RFA No. 611/2001 9 March, 2011Amitoz SinghNo ratings yet

- In The High Court of Delhi at New Delhi RFA No. 611/2001 9 March, 2011Document7 pagesIn The High Court of Delhi at New Delhi RFA No. 611/2001 9 March, 2011Amitoz SinghNo ratings yet

- CRM-M 11487 2009 31 08 2009 Final OrderDocument2 pagesCRM-M 11487 2009 31 08 2009 Final OrderAmitoz SinghNo ratings yet

- Short Case Study: Communication Strategies in The WorkplaceDocument3 pagesShort Case Study: Communication Strategies in The WorkplaceGorge Rog Almaden MorillaNo ratings yet

- Philo (Pre Lim) ReviewerDocument14 pagesPhilo (Pre Lim) ReviewerJustine ViloneroNo ratings yet

- Tutorial QuestionsDocument6 pagesTutorial QuestionsEribeta TeiaNo ratings yet

- Arni University::: B.Tech Mechanical II SEMESTERDocument3 pagesArni University::: B.Tech Mechanical II SEMESTERNavneet KumarNo ratings yet

- James Hughes - Orthodoxy and EvolutionDocument63 pagesJames Hughes - Orthodoxy and EvolutionJames L. KelleyNo ratings yet

- Developmental PsychologyDocument77 pagesDevelopmental PsychologyArkan KhairullahNo ratings yet

- OmniSim BrochureDocument4 pagesOmniSim Brochurecchee_longNo ratings yet

- W For WomanDocument7 pagesW For Womanaditi saxenaNo ratings yet

- Example of A Covering Letter: (Continues On Next Page)Document2 pagesExample of A Covering Letter: (Continues On Next Page)The University of Sussex Careers and Employability CentreNo ratings yet

- Dieta Si NutritieDocument57 pagesDieta Si Nutritiejos3phine100% (2)

- Liver Biopsy: Mary Raina Angeli Fujiyoshi, MDDocument10 pagesLiver Biopsy: Mary Raina Angeli Fujiyoshi, MDRaina FujiyoshiNo ratings yet

- Definition of TermsDocument4 pagesDefinition of TermsAgnes Francisco50% (2)

- Principles of Management: Two Marks QuestionDocument18 pagesPrinciples of Management: Two Marks Questionubercool91No ratings yet

- Mayo Medical School: College of MedicineDocument28 pagesMayo Medical School: College of MedicineDragomir IsabellaNo ratings yet

- Topic 5 - Teaching For Understanding - The Role of ICT and E-Learning (By Martha Stone Wiske)Document2 pagesTopic 5 - Teaching For Understanding - The Role of ICT and E-Learning (By Martha Stone Wiske)Hark Herald Cruz SarmientoNo ratings yet

- Kinder New DLL Week 12Document6 pagesKinder New DLL Week 12kenzoNo ratings yet

- Practical Research 2 - Action PlanDocument2 pagesPractical Research 2 - Action Plananon_186395269100% (1)

- Kisi Kisi B.inggris Pts Sem 1 Kelas 9Document5 pagesKisi Kisi B.inggris Pts Sem 1 Kelas 9Stevany TracysiliaNo ratings yet

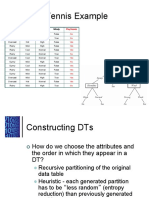

- Play Tennis Example: Outlook Temperature Humidity WindyDocument29 pagesPlay Tennis Example: Outlook Temperature Humidity Windyioi123No ratings yet

- Science Exam With Answer KeyDocument4 pagesScience Exam With Answer KeyMs PaperworksNo ratings yet

- Whirligig Design ChallengeDocument4 pagesWhirligig Design Challengeapi-450232271No ratings yet

- MYP ASSESSMENT GUIDANCE ParentsDocument5 pagesMYP ASSESSMENT GUIDANCE ParentsMatt LimaNo ratings yet

- Lesson 7.3 Explain How The Social System Transform Human RelationsDocument3 pagesLesson 7.3 Explain How The Social System Transform Human RelationsAya100% (1)

- Republic Vs LedesmaDocument2 pagesRepublic Vs LedesmaestvanguardiaNo ratings yet

- The ABCs of DR Desmond Ford S Theology W H JohnsDocument16 pagesThe ABCs of DR Desmond Ford S Theology W H JohnsBogdan PlaticaNo ratings yet

- Navigation SystemsDocument28 pagesNavigation SystemsMaria Alejandra VargasNo ratings yet

- Overview Six Sigma PhasesDocument3 pagesOverview Six Sigma Phaseshans_106No ratings yet

- Coop Learning ActivitiesDocument198 pagesCoop Learning ActivitiesJanine Mosca GonzalesNo ratings yet