Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Language of The Calypso

The Language of The Calypso

Uploaded by

Reem GharbiCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Tower Weights & Foundation DetailsDocument6 pagesTower Weights & Foundation Detailsapi-2588520085% (27)

- Hallelujah by Kelly MooneyDocument3 pagesHallelujah by Kelly MooneyChristopher FrancisNo ratings yet

- Music and Poetry - CastelnuovoDocument11 pagesMusic and Poetry - CastelnuovoGaspare Alessandro Parrino100% (1)

- Herbert Von Karajan A Life in Music by Richard OsborneDocument896 pagesHerbert Von Karajan A Life in Music by Richard OsborneJesús Echeverría100% (2)

- 014 Old ViolinsDocument322 pages014 Old ViolinsPeter Giovanni Melo Flórez100% (3)

- James, Ravel's Chansons Madécasses (MQ 1990)Document26 pagesJames, Ravel's Chansons Madécasses (MQ 1990)Victoria Chang100% (1)

- Exploration of Harmony EbookDocument49 pagesExploration of Harmony EbookPeter Nunez100% (3)

- Invisible Fences Prose Poetry As A Genre in French and American Literature (Monte, Steven)Document310 pagesInvisible Fences Prose Poetry As A Genre in French and American Literature (Monte, Steven)vivianaibuerNo ratings yet

- Boulez On CarterDocument6 pagesBoulez On CarterDylan RichardsNo ratings yet

- Fourteen Notes On The VersionDocument6 pagesFourteen Notes On The VersionAndrei DobosNo ratings yet

- Public Gdcmassbookdig Introductorynote00kent Introductorynote00kentDocument102 pagesPublic Gdcmassbookdig Introductorynote00kent Introductorynote00kentOluwafemi Marvellous ayomideNo ratings yet

- The Complete Poetical Works of Edmund Spenser. Illustrated: The Faerie Queene, Complaints, Daphnaïda, Astrophel, Prothalamion and othersFrom EverandThe Complete Poetical Works of Edmund Spenser. Illustrated: The Faerie Queene, Complaints, Daphnaïda, Astrophel, Prothalamion and othersNo ratings yet

- Pound - A RetrospectDocument8 pagesPound - A RetrospectAndrei Suarez Dillon SoaresNo ratings yet

- Third Thoughts On Translating PoetryDocument11 pagesThird Thoughts On Translating PoetryLorena Díaz GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Black Antigone: Sophocles’ Tragedy Meets the Heartbeat of AfricaFrom EverandBlack Antigone: Sophocles’ Tragedy Meets the Heartbeat of AfricaNo ratings yet

- The Complete Poems of John Keats: Ode on a Grecian Urn, Ode to a Nightingale, Hyperion, Endymion, The Eve of St. Agnes, Isabella, Ode to Psyche, Lamia, Sonnets…From EverandThe Complete Poems of John Keats: Ode on a Grecian Urn, Ode to a Nightingale, Hyperion, Endymion, The Eve of St. Agnes, Isabella, Ode to Psyche, Lamia, Sonnets…No ratings yet

- Poetry SoundsDocument9 pagesPoetry SoundsdoradaramaNo ratings yet

- Poems With DisabilitiesDocument5 pagesPoems With DisabilitiesDavidRooneyNo ratings yet

- The Satires, Epistles, and Art of Poetry by Horace, 65 BC-8 BCDocument119 pagesThe Satires, Epistles, and Art of Poetry by Horace, 65 BC-8 BCGutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- Language Sampler: Edited by Charles BemsteinDocument52 pagesLanguage Sampler: Edited by Charles Bemsteinrooster_atomicNo ratings yet

- Unsur Unsur Puisi LengkapDocument49 pagesUnsur Unsur Puisi LengkapAndhini De AngeloNo ratings yet

- 1908 Thomas Ernest Hulme - Lecture On Modern PoetryDocument3 pages1908 Thomas Ernest Hulme - Lecture On Modern PoetryThomaz SimoesNo ratings yet

- William Wordsworth Appendix To Lyrical Ballads (1802) "By What Is Usually Called Poetic Diction."Document5 pagesWilliam Wordsworth Appendix To Lyrical Ballads (1802) "By What Is Usually Called Poetic Diction."azalea.astralisNo ratings yet

- Anabases 4922Document11 pagesAnabases 4922Armenjy Legue (HD)No ratings yet

- Poetry Literature ReviewDocument4 pagesPoetry Literature Reviewtug0l0byh1g2100% (1)

- The Oxford Book of Latin Verse by H. W. Garrod (1912)Document360 pagesThe Oxford Book of Latin Verse by H. W. Garrod (1912)Per BortenNo ratings yet

- Ballads of Romance and Chivalry: Popular Ballads of the Olden Times - First SeriesFrom EverandBallads of Romance and Chivalry: Popular Ballads of the Olden Times - First SeriesNo ratings yet

- Analysis of PoetryDocument64 pagesAnalysis of Poetryroel mabbayad100% (1)

- Poetic DevicesDocument30 pagesPoetic Devicesanwarbushara3No ratings yet

- Structural Pro Sody Final Final RevDocument21 pagesStructural Pro Sody Final Final RevPragyabgNo ratings yet

- Untitled DocumentDocument7 pagesUntitled DocumentFifa HassanNo ratings yet

- The Continuity of Poetic Language: Studies in English Poetry from the 1540's to the 1940'sFrom EverandThe Continuity of Poetic Language: Studies in English Poetry from the 1540's to the 1940'sNo ratings yet

- Ravel Analysis in 1921Document11 pagesRavel Analysis in 1921Paul Cuffari100% (1)

- A Few Donts by An ImagisteDocument8 pagesA Few Donts by An ImagisteYasmin Wankler Pinheiro MachadoNo ratings yet

- Poetic TechniquesDocument15 pagesPoetic TechniquesVirender SinghNo ratings yet

- A New English Anthology VerseDocument62 pagesA New English Anthology VerseVaqas TajNo ratings yet

- Body Haul SamplerDocument7 pagesBody Haul SamplerCarl JavierNo ratings yet

- The Oxford Book of Latin VerseDocument354 pagesThe Oxford Book of Latin VerseMarcelo Souto Maior Monteiro100% (1)

- University of Malakand Chakdara, Dir LowerDocument10 pagesUniversity of Malakand Chakdara, Dir LowerWaseemNo ratings yet

- Eliot - Poetry and DramaDocument11 pagesEliot - Poetry and DramaCaimito de GuayabalNo ratings yet

- Stylistic AnalysisDocument16 pagesStylistic AnalysisKhalid ShamkhiNo ratings yet

- "Beowulf" in Literary HistoryDocument9 pages"Beowulf" in Literary HistoryAlexanderNo ratings yet

- The Complete Poetry of John Keats: Ode on a Grecian Urn + Ode to a Nightingale + Hyperion + Endymion + The Eve of St. Agnes + Isabella + Ode to Psyche + Lamia + Sonnets and more from one of the most beloved English Romantic poetsFrom EverandThe Complete Poetry of John Keats: Ode on a Grecian Urn + Ode to a Nightingale + Hyperion + Endymion + The Eve of St. Agnes + Isabella + Ode to Psyche + Lamia + Sonnets and more from one of the most beloved English Romantic poetsNo ratings yet

- Anthology of Contemporary PoetryDocument146 pagesAnthology of Contemporary Poetrycatalin_teodoriu83100% (1)

- The Heresy of Connecting Welsh and Semitic, EtcDocument14 pagesThe Heresy of Connecting Welsh and Semitic, Etclonnnet7380No ratings yet

- From The Evaluation of Portraits Towards The Explication of PoemsDocument12 pagesFrom The Evaluation of Portraits Towards The Explication of PoemsSaleem NasimNo ratings yet

- Third World Quarterly: Taylor & Francis, LTDDocument41 pagesThird World Quarterly: Taylor & Francis, LTDReem Gharbi100% (1)

- With A Tassa Blending: Calypso and Cultural Identity in Indo-Caribbean FictionDocument24 pagesWith A Tassa Blending: Calypso and Cultural Identity in Indo-Caribbean FictionReem GharbiNo ratings yet

- Gordon Rohlehr's Forty Years in CalypsoDocument13 pagesGordon Rohlehr's Forty Years in CalypsoReem GharbiNo ratings yet

- Middle PassageDocument41 pagesMiddle PassageReem GharbiNo ratings yet

- Third Periodical Test in MapehDocument7 pagesThird Periodical Test in MapehgeraldNo ratings yet

- GSD Latam It Contact ListDocument1 pageGSD Latam It Contact ListNacho RannieNo ratings yet

- Flora Audition Document PDFDocument4 pagesFlora Audition Document PDFDaniel NixonNo ratings yet

- Women and The Short Stories of Bharati MukherjeeDocument3 pagesWomen and The Short Stories of Bharati MukherjeeArnab MukherjeeNo ratings yet

- Condicionales - Inglés para PerezososDocument1 pageCondicionales - Inglés para PerezososAntonio EspadasNo ratings yet

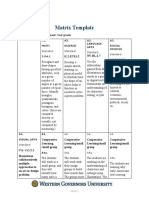

- Matrix Template: K-2-ETS1-2 NV - RL.2.7Document15 pagesMatrix Template: K-2-ETS1-2 NV - RL.2.7Willie HarringtonNo ratings yet

- Chops Mastery 4Document29 pagesChops Mastery 4陳易No ratings yet

- Mason - Clarinet Sonata - Score PianoDocument62 pagesMason - Clarinet Sonata - Score Pianoasweifhje1245No ratings yet

- Resume For Mauricio Franco: November - December 2020Document2 pagesResume For Mauricio Franco: November - December 2020Mauricio FrancoNo ratings yet

- 青花瓷 (指弹)Document3 pages青花瓷 (指弹)X GarryNo ratings yet

- Studio N°6 Abelardo AlbisiDocument5 pagesStudio N°6 Abelardo AlbisiLorenzo Alienware FinocchiNo ratings yet

- MAPEH10 Module 4Document36 pagesMAPEH10 Module 4albaystudentashleyNo ratings yet

- Chester Bennington Tribute: Zakura Linkin ParkDocument5 pagesChester Bennington Tribute: Zakura Linkin ParkcharlescamilloNo ratings yet

- Captain HookDocument1 pageCaptain HookErich PolleyNo ratings yet

- Woodwind in WorshipDocument2 pagesWoodwind in WorshipLydia UtamiNo ratings yet

- Vibraphone Technique Dampening and Pedaling David FriedmanDocument52 pagesVibraphone Technique Dampening and Pedaling David FriedmanLorenzoBertacchiniNo ratings yet

- Traditional Vietnamese Music Has Been Mainly Used For Religious ActivitiesDocument2 pagesTraditional Vietnamese Music Has Been Mainly Used For Religious ActivitiesDuy TrịnhNo ratings yet

- q4 Mapeh 7 WHLP Leap S.test w1 w8 MagsinoDocument39 pagesq4 Mapeh 7 WHLP Leap S.test w1 w8 MagsinoFatima11 MagsinoNo ratings yet

- Hatebreed 2Document4 pagesHatebreed 2frankiepalmeriNo ratings yet

- Dear Guitar Hero OpethDocument3 pagesDear Guitar Hero OpethPedro MirandaNo ratings yet

- Legal Basis of MapehDocument34 pagesLegal Basis of MapehMaeNo ratings yet

- Theory of SongxDocument5 pagesTheory of SongxtiaranasirNo ratings yet

- Rama KausalyaDocument3 pagesRama Kausalyakanya MNo ratings yet

- Beyond Sonata Deformation: Liszt's Symphonic Poem Tasso and The Concept of Two-Dimensional Sonata FormDocument24 pagesBeyond Sonata Deformation: Liszt's Symphonic Poem Tasso and The Concept of Two-Dimensional Sonata FormSamanosuke7ANo ratings yet

- Strauss Trumpet in BBDocument2 pagesStrauss Trumpet in BBStagedoor ManorNo ratings yet

The Language of The Calypso

The Language of The Calypso

Uploaded by

Reem GharbiOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Language of The Calypso

The Language of The Calypso

Uploaded by

Reem GharbiCopyright:

Available Formats

Gordon Rohlehr's 'Sparrow and the Language of the Calypso' –CAM Comment–

Author(s): Edward Brathwaite

Source: Caribbean Quarterly, Vol. 14, No. 1/2, A Survey of the Arts (March - June 1968), pp.

91-96

Published by: University of the West Indies and Caribbean Quarterly

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40653060 .

Accessed: 14/06/2014 08:48

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

University of the West Indies and Caribbean Quarterly are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and

extend access to Caribbean Quarterly.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 194.29.185.109 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 08:48:03 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

IV- Gordon Rohlehr's 'Sparrow and

the Language of the Calypso'

- CAM Comment -

EdwardBrathwaite: Was listeningto the tape of yourtalk this morn-

ing, and came upon this passage towardsthe end:

We cannot help noting how close Sparrow has kept to the

rhythmsand idioms of Trinidadian speech... It seems to me

that there is in the spoken language of Trinidad a potential

of rhythmicorganisationwhich our poets have not yet dis-

covered- or if they have, have not yet exploited... It [the

calypso] may help the West Indian poet to realise the rhythmic

potentialof his ordinaryuse of English, for the calypsonian's

language is prettyclose to standard English,yet his organisa-

tion of language is entirelydifferent. The breakthrough,it

seems to me, can come not only in the use of creole, such as

that which is writtenby Louise Bennett,but throughthe use

of English as it is [transformed]when translated into WI

speech rhythms. . .

Tm takingthis up with you because I too am interestedin critical

standards; and because you have been a great opponent of the

generalisation.Leaving aside your limitationof the above generalisa-

tion to 'the spoken language of T'dad', I really must take you up on

yourstatementon 'the WI poet.'

My pointhere is this: Derek,yourcountrymen LorrimerAlexander

and WordsworthMe Andrewhave all, from time to time, used, quite

successfullyin my view,speech rhythms;and so has Dennis Scott in a

less directway. And of course Rights of Passage is committedto this

approach rightdown the line. I can understandyour thinkingthese

effortsnot worthwhile;but I cannot see you,as a critic,ignoringthem,

in yourcontext,as if they didn't exist. As a matterof fact, on your

own principle of non-generalisation,one would have expected some

little indicationas to why you think these effortsfail.

My own opinion on this kind of discussion is that the academic

start off

criticsI have so far heard on this matterof 'dialect/poetry,'

with the preconceptionthat an artist like Sparrow is in some way an

entirelydifferentbeing froman artist,say, like myselfor Derek or any

of the others; so that in discussion the two types tend to be kept

separate.

91

This content downloaded from 194.29.185.109 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 08:48:03 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

This was surelythe case with your talk on Friday; though I hope

you will understandthat I'm in no way tryingto detract fromyour

positive contribution:the subjection of Sparrow's lyrics to critical

analysis and illumination;the emphasison his truth-telling; the moral

implicationsof his statementsand situations; the ironic twistevident

in so much of his work; and (for me one of the high-spots) the

explanation of the calypsonian'sdramatic eye and I: the fact that 'I'

is not necessarilypersonal,but oftena persona.

But afterall this,the generalisationsabout 'the West Indian poet/

who has not brokenthroughto West Indian speech rhythms,remain.

In ignoringwhat in fact has been attempted,and failingto link these

attempts with Sparrow's achievementand present them for further

discussion,you lost a chance, I think,(which is the final justification

of criticism),to help elucidate the workof the artistsinvolved.

Gordon Rohlehr: I think my point towards the end was not

really grasped because it was so sloppily made, and so

hurriedly sketched in. 'The calypso may help the WI poet to

realise the rhythmicpotential of his ordinaryuse of English.' You

took this to mean that I was implyingthat the WI poet did not realise

this, that no efforthad been made to capture WI speech rhythms,or

that I didn'tthinksuch effortswortheithermentionor even considera-

tion. But this wasn't my point at all. What I was remarkingwas the

calypsonian'sabilityto blend words with extremelycomplex rhythmic

phrases of music and still retain the fluidityand basic rhythmsof

speech. Let me quote fromtwo sentences before. . . 'One doesn't feel

that language is being coerced into the rigidityof form,but that

language is alive and fluid as it plays against the necessarystrictness

of the music'

What I thinkI was sayingis this: Calypso providesus with living

examples of a verycomplexmetricorganisationof language. It is not

simplya matterof using WI speech rhythmsand idioms,but of being

consciousof the syncopateddrum-rhythms in the backgroundof a 4/4

timesignaturebrokendown into semi-quaversso that one has a maxi-

mum of 16 syllablesper bar ... of the extremefreedom which this

createsnot onlyin the music,but in the bendingof wordsto match the

sinuositiesof rhythm. I am probablywrong,but I felt that because

Sparrow'smusical language is so close to that of speech,theremust be

somethingin the speech itselfwhich hearkens towardsmusic.

Now, our poets have always been conscious of WI speech. Derek

Walcott uses it in a poem like

Poopa da was, a fête; ah mean it had

Free rum free whiskyand some fellas beating

Pan fromone o dem band in Trinidad...

to play against the traditionalpentametricalstructureof the English

sonnet. . . Compare the first line of Toopa' with, say, Shakespeare's

'Not marble nor the gilded monuments' (etc.) and you will find a

92

This content downloaded from 194.29.185.109 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 08:48:03 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

beautifulcounterpointing.The ear accustomed to traditionalEnglish

rhythms(and many WI ears are) is continuallysurprisedby the rush

and lightnessof the movementof Walcott's poem which seems, but

only seems, to ignore the martial rigidityof the heroic metre,where

stressesare fairlypredictable,as in a quick-stepor fox-trot. It seems

to me that one assumes the presence of the main stress and forgets

about it ... that (to use a musicalImage) the bass is therein the back-

ground,but no longerto keep time.

Poopa d& was ä fete a mean ¥t had

FreS rum fre£whisky&nd some f&läs béatìhg

Pan frtfmon& ö dem band ïn TrÌnfàad.

Now compare this with say Marlow'sheroic verse

What is beauty saith my sufferingsthen

If all the pens that ever poets held

Had fed the jewels of their masters' thoughts. . .

It is an extremeexample chosen to give an idea of the rigidityof

the heroic metre; but we can see where Walcott departed from this

and at the same time how the older formremains in the background.

One notes e.g. 'a mean it had* at the end of the firstline, where the

verseobeys fora momentthe dictates of traditionalmetrics. And one

notes the completechange of tone and metre in the last part of the

poem

And it was round this part once that the heart

Of a youngchild was torn fromit alive

By two practitionersof native art . .

A change of tone,a change of metre,a swingback to the traditional.

Is it ironicthat the voice of serious reflectionshould be so traditional

and so English?

It seems that I am providingthe best argumentagainst myself.

In fact this poem of Walcott'sis like 'Parang' somethingof an excep-

tion in his work.

I have only just noted, by the way, the similaritybetween the

thumpof heroic verse and the thumpof most English dance rhythms,

which are unsyncopated,simple, and obviously influenced by the

march. . .Pompand Circumstance. The differencebetweenCalypso and

Quick-step,both of which have the same time signature,is similar to

the differencebetweena Sydneysonnet,say, and Walcott's'Poopa! da

was a fête/ The one marches,the other trips.

Now about Rights. Did I mention that I found your calypso

remarkableforits metricorganisationof speech rhythmto suggestthe

syncopationof music? I am sure that I did so in a formerletter,that

I told you or Doris this last weekend. This is, in fact,the best example

I know of the rhythmsof calypso being exploited by a WI poet to

heightenthe rhythmicpotentialof speech. Walcott achieves one kind

93

This content downloaded from 194.29.185.109 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 08:48:03 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

oí counterpoint,you another. Let us thereforelook a littlemoreclosely

at 'Calypso.' You will,of course,appreciatethat my stressesmay vary

fromyours. I mentionedhow I differedfromMaureen Warner when

we tried to determinewhere the strong stresses should be placed in

some of Sparrow'skaisos.

'The stone h&d skidded arc'd and bloomedïnto islands

Cuba and San Dominga.

Problemsimmediately. The strongstress on 'arc'd' detracts from

the strongstress on 'skidded,'plays against it and moderates it. I

would have only a moderatestress on 'islands' and so on.

And #fcourse ¥t was a wonderfultime

time

X profitablehospitable?wéll-wiSrth-yòur

When captains carried receiptsf8r rices.

Accordingto the music rhythms'was' in the firstline ought to be

stressed. Accordingto the speech rhythmsit ought not. The verse

falls back into stricttimewiththe thirdline 'when captains' etc. . . . and

this contrasts with the extra semiquaver passage in 'a profitable

hóspYtable'etc. Compare 'an elSgSnt bètaevtfl#nt rédÔlèhttime' where

a similar thing (but not quite the same) is being achieved. In steel-

band the counterpointstrumfor the line 'a profitablehospitablewell-

worth-your time' wouldbe played by the second pans, and the counter-

point strum for 'an elegant benevolentredolenttime' would be played

by the guitars.

Now let's considera calypso Robberywith V

n8 stage personality

(X man wïth) nó tfrfgftiárfty

They tryingtö m&e me ltfoksmall.

'Make' may be light,heavy or moderatedependingon the mood of

the calypsonian. The rattling (altt#) rhythmrecurs throughoutthe

kaiso and conveysSparrow'sbitternessand contemptforthe king they

chose.

Take another example, Simpson

It w& Simpson,the fiin&a'l agency man

wYd ë cóffíhïn ë han

Yìm mean to sàV ytfudon't kn8wSimpsonthe funeraletc.

That 'You mean to say you don't know' is one of the extremeuses

of the semi-quaverpassage in Sparrow. Gunslingershas a passage

Nearly gveryyoungman ïs S gtínslfngèr

WÏd Ï ràztfrSnd S ste'elknuckle'¿Sn« fíngfr. . .

Again one is uncertainof quantities. But am I making my point

or any worthwhilepoint? My point is that we can create the metrical

equivalent of heroic verse by a consciousnessof the extremevariety

94

This content downloaded from 194.29.185.109 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 08:48:03 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

of our speech rhythmsand our musical rhythms. After all the

Elizabethan Lyric is being read as poetry. . . Are we conscious of this

great variety? Sparrow published a book with 120 calypsoes each of

which meritscarefulmetricalstudyand analysis. There are calypsoes

withlong lines,calypsoeswithshortlines, all sortsof calypsoes.Under-

standinghow they have been organised,determininghow far one can

use some of theirrhythmsto gain veryun-calypsoeffects,or how much

the words can be consideredon their own ... all this remains to be

done. A vast job. I get the feeling that whenever our poets (a

dangerous generalisationI know) consider our speech rhythmsthey

feel like pioneers confrontinga vast unmapped world which promises

to be exciting. I don't know how much they are conscious that this

world has been thoroughlymapped, explored,exploited and presented

to them for their benefitby Sparrow (and by so many others). You

know more about our poets than I, and I was rash to make the kind

of statementI did. But are they conscious? By the way I ought to

have mentionedA. J. Seymour'spoem To a Calypsonian (is that the

name?). It begins... 'A thousand runningradios blare your song...'

and remindsthe calypsonian (Kitch I thinkit is) 'Rememberthat the

childrenneed fatherstoo

Moralityto misery

You celebrate for the world to see.'

It was published in Kyk-over-aland I sometimeswonder why it

has never been anthologised. Seymourtoo uses calypso rhythmscon-

sciouslyand well, to examine the calypso mind.

Finally,you said that academic criticslike myselfwhen discussing

'dialect/poetry'start off with the preconceptionthat an artist like

Sparrowis in some way an entirelydifferent being froman artist like

yourselfor Derek or any of the others. I am really sorrythat this is

the impressionI conveyed,since I thoughtthat by applyingto Sparrow's

workthe strictestacademic standards I was really placing him on par

with any other artist. A distinctioncan obviouslybe drawn fromhis

unself-consciousexploitationof language and rhythmand that of the

'academic poet' who must,because of his great weightof learning,be

self-conscious. But don't get me wrong. I don't think that Sparrow

uses words carelessly,that his art is 'natural,' spontaneous,''native,'

fullof an 'unsophisticatedvitality'etc. I thinkhis mind and ironyare

sophisticatedin the importantsense of the word. They are the result

of a full and alive awareness... I think him a betterartist than most

of our poets. Intellectual patronage was the last thing I wanted to

suggest. If I didn't make the comparisonwith the rest of WI poetry,

that was because I was so sleepy after a night'sworkthat I forgotor

gave up. Moreoveryou see how much time such a comparisonwould

have required,foreven now,I probablyhaven't made myselfclear.

Brathwaite: I agree with you that not enough has been so far

made of our speech rhythmsby our poets - though your qualitative

analysis is revealing. More will be done as 'dialect' becomes

validated by criticssuch as yourself. We've left out of our discussion

95

This content downloaded from 194.29.185.109 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 08:48:03 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

so fartheone undoubted mistressofthisworld- LouiseBennett.Here

thepoemslivein performance do; and thisto me

as the calypsonians'

is themostimportant aspectofthebusiness. I thinktoothatwe must

lookat thecalypsoas onlya partof a muchwiderand richertradition

whichincludesfolksong,folktale and 'oralperformances'suchas tea-

meetingspeeches. I've beentryingto say something aboutthisin my

'Jazzand the WestIndianNovel'at presentappearingin BIM.

96

This content downloaded from 194.29.185.109 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 08:48:03 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Tower Weights & Foundation DetailsDocument6 pagesTower Weights & Foundation Detailsapi-2588520085% (27)

- Hallelujah by Kelly MooneyDocument3 pagesHallelujah by Kelly MooneyChristopher FrancisNo ratings yet

- Music and Poetry - CastelnuovoDocument11 pagesMusic and Poetry - CastelnuovoGaspare Alessandro Parrino100% (1)

- Herbert Von Karajan A Life in Music by Richard OsborneDocument896 pagesHerbert Von Karajan A Life in Music by Richard OsborneJesús Echeverría100% (2)

- 014 Old ViolinsDocument322 pages014 Old ViolinsPeter Giovanni Melo Flórez100% (3)

- James, Ravel's Chansons Madécasses (MQ 1990)Document26 pagesJames, Ravel's Chansons Madécasses (MQ 1990)Victoria Chang100% (1)

- Exploration of Harmony EbookDocument49 pagesExploration of Harmony EbookPeter Nunez100% (3)

- Invisible Fences Prose Poetry As A Genre in French and American Literature (Monte, Steven)Document310 pagesInvisible Fences Prose Poetry As A Genre in French and American Literature (Monte, Steven)vivianaibuerNo ratings yet

- Boulez On CarterDocument6 pagesBoulez On CarterDylan RichardsNo ratings yet

- Fourteen Notes On The VersionDocument6 pagesFourteen Notes On The VersionAndrei DobosNo ratings yet

- Public Gdcmassbookdig Introductorynote00kent Introductorynote00kentDocument102 pagesPublic Gdcmassbookdig Introductorynote00kent Introductorynote00kentOluwafemi Marvellous ayomideNo ratings yet

- The Complete Poetical Works of Edmund Spenser. Illustrated: The Faerie Queene, Complaints, Daphnaïda, Astrophel, Prothalamion and othersFrom EverandThe Complete Poetical Works of Edmund Spenser. Illustrated: The Faerie Queene, Complaints, Daphnaïda, Astrophel, Prothalamion and othersNo ratings yet

- Pound - A RetrospectDocument8 pagesPound - A RetrospectAndrei Suarez Dillon SoaresNo ratings yet

- Third Thoughts On Translating PoetryDocument11 pagesThird Thoughts On Translating PoetryLorena Díaz GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Black Antigone: Sophocles’ Tragedy Meets the Heartbeat of AfricaFrom EverandBlack Antigone: Sophocles’ Tragedy Meets the Heartbeat of AfricaNo ratings yet

- The Complete Poems of John Keats: Ode on a Grecian Urn, Ode to a Nightingale, Hyperion, Endymion, The Eve of St. Agnes, Isabella, Ode to Psyche, Lamia, Sonnets…From EverandThe Complete Poems of John Keats: Ode on a Grecian Urn, Ode to a Nightingale, Hyperion, Endymion, The Eve of St. Agnes, Isabella, Ode to Psyche, Lamia, Sonnets…No ratings yet

- Poetry SoundsDocument9 pagesPoetry SoundsdoradaramaNo ratings yet

- Poems With DisabilitiesDocument5 pagesPoems With DisabilitiesDavidRooneyNo ratings yet

- The Satires, Epistles, and Art of Poetry by Horace, 65 BC-8 BCDocument119 pagesThe Satires, Epistles, and Art of Poetry by Horace, 65 BC-8 BCGutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- Language Sampler: Edited by Charles BemsteinDocument52 pagesLanguage Sampler: Edited by Charles Bemsteinrooster_atomicNo ratings yet

- Unsur Unsur Puisi LengkapDocument49 pagesUnsur Unsur Puisi LengkapAndhini De AngeloNo ratings yet

- 1908 Thomas Ernest Hulme - Lecture On Modern PoetryDocument3 pages1908 Thomas Ernest Hulme - Lecture On Modern PoetryThomaz SimoesNo ratings yet

- William Wordsworth Appendix To Lyrical Ballads (1802) "By What Is Usually Called Poetic Diction."Document5 pagesWilliam Wordsworth Appendix To Lyrical Ballads (1802) "By What Is Usually Called Poetic Diction."azalea.astralisNo ratings yet

- Anabases 4922Document11 pagesAnabases 4922Armenjy Legue (HD)No ratings yet

- Poetry Literature ReviewDocument4 pagesPoetry Literature Reviewtug0l0byh1g2100% (1)

- The Oxford Book of Latin Verse by H. W. Garrod (1912)Document360 pagesThe Oxford Book of Latin Verse by H. W. Garrod (1912)Per BortenNo ratings yet

- Ballads of Romance and Chivalry: Popular Ballads of the Olden Times - First SeriesFrom EverandBallads of Romance and Chivalry: Popular Ballads of the Olden Times - First SeriesNo ratings yet

- Analysis of PoetryDocument64 pagesAnalysis of Poetryroel mabbayad100% (1)

- Poetic DevicesDocument30 pagesPoetic Devicesanwarbushara3No ratings yet

- Structural Pro Sody Final Final RevDocument21 pagesStructural Pro Sody Final Final RevPragyabgNo ratings yet

- Untitled DocumentDocument7 pagesUntitled DocumentFifa HassanNo ratings yet

- The Continuity of Poetic Language: Studies in English Poetry from the 1540's to the 1940'sFrom EverandThe Continuity of Poetic Language: Studies in English Poetry from the 1540's to the 1940'sNo ratings yet

- Ravel Analysis in 1921Document11 pagesRavel Analysis in 1921Paul Cuffari100% (1)

- A Few Donts by An ImagisteDocument8 pagesA Few Donts by An ImagisteYasmin Wankler Pinheiro MachadoNo ratings yet

- Poetic TechniquesDocument15 pagesPoetic TechniquesVirender SinghNo ratings yet

- A New English Anthology VerseDocument62 pagesA New English Anthology VerseVaqas TajNo ratings yet

- Body Haul SamplerDocument7 pagesBody Haul SamplerCarl JavierNo ratings yet

- The Oxford Book of Latin VerseDocument354 pagesThe Oxford Book of Latin VerseMarcelo Souto Maior Monteiro100% (1)

- University of Malakand Chakdara, Dir LowerDocument10 pagesUniversity of Malakand Chakdara, Dir LowerWaseemNo ratings yet

- Eliot - Poetry and DramaDocument11 pagesEliot - Poetry and DramaCaimito de GuayabalNo ratings yet

- Stylistic AnalysisDocument16 pagesStylistic AnalysisKhalid ShamkhiNo ratings yet

- "Beowulf" in Literary HistoryDocument9 pages"Beowulf" in Literary HistoryAlexanderNo ratings yet

- The Complete Poetry of John Keats: Ode on a Grecian Urn + Ode to a Nightingale + Hyperion + Endymion + The Eve of St. Agnes + Isabella + Ode to Psyche + Lamia + Sonnets and more from one of the most beloved English Romantic poetsFrom EverandThe Complete Poetry of John Keats: Ode on a Grecian Urn + Ode to a Nightingale + Hyperion + Endymion + The Eve of St. Agnes + Isabella + Ode to Psyche + Lamia + Sonnets and more from one of the most beloved English Romantic poetsNo ratings yet

- Anthology of Contemporary PoetryDocument146 pagesAnthology of Contemporary Poetrycatalin_teodoriu83100% (1)

- The Heresy of Connecting Welsh and Semitic, EtcDocument14 pagesThe Heresy of Connecting Welsh and Semitic, Etclonnnet7380No ratings yet

- From The Evaluation of Portraits Towards The Explication of PoemsDocument12 pagesFrom The Evaluation of Portraits Towards The Explication of PoemsSaleem NasimNo ratings yet

- Third World Quarterly: Taylor & Francis, LTDDocument41 pagesThird World Quarterly: Taylor & Francis, LTDReem Gharbi100% (1)

- With A Tassa Blending: Calypso and Cultural Identity in Indo-Caribbean FictionDocument24 pagesWith A Tassa Blending: Calypso and Cultural Identity in Indo-Caribbean FictionReem GharbiNo ratings yet

- Gordon Rohlehr's Forty Years in CalypsoDocument13 pagesGordon Rohlehr's Forty Years in CalypsoReem GharbiNo ratings yet

- Middle PassageDocument41 pagesMiddle PassageReem GharbiNo ratings yet

- Third Periodical Test in MapehDocument7 pagesThird Periodical Test in MapehgeraldNo ratings yet

- GSD Latam It Contact ListDocument1 pageGSD Latam It Contact ListNacho RannieNo ratings yet

- Flora Audition Document PDFDocument4 pagesFlora Audition Document PDFDaniel NixonNo ratings yet

- Women and The Short Stories of Bharati MukherjeeDocument3 pagesWomen and The Short Stories of Bharati MukherjeeArnab MukherjeeNo ratings yet

- Condicionales - Inglés para PerezososDocument1 pageCondicionales - Inglés para PerezososAntonio EspadasNo ratings yet

- Matrix Template: K-2-ETS1-2 NV - RL.2.7Document15 pagesMatrix Template: K-2-ETS1-2 NV - RL.2.7Willie HarringtonNo ratings yet

- Chops Mastery 4Document29 pagesChops Mastery 4陳易No ratings yet

- Mason - Clarinet Sonata - Score PianoDocument62 pagesMason - Clarinet Sonata - Score Pianoasweifhje1245No ratings yet

- Resume For Mauricio Franco: November - December 2020Document2 pagesResume For Mauricio Franco: November - December 2020Mauricio FrancoNo ratings yet

- 青花瓷 (指弹)Document3 pages青花瓷 (指弹)X GarryNo ratings yet

- Studio N°6 Abelardo AlbisiDocument5 pagesStudio N°6 Abelardo AlbisiLorenzo Alienware FinocchiNo ratings yet

- MAPEH10 Module 4Document36 pagesMAPEH10 Module 4albaystudentashleyNo ratings yet

- Chester Bennington Tribute: Zakura Linkin ParkDocument5 pagesChester Bennington Tribute: Zakura Linkin ParkcharlescamilloNo ratings yet

- Captain HookDocument1 pageCaptain HookErich PolleyNo ratings yet

- Woodwind in WorshipDocument2 pagesWoodwind in WorshipLydia UtamiNo ratings yet

- Vibraphone Technique Dampening and Pedaling David FriedmanDocument52 pagesVibraphone Technique Dampening and Pedaling David FriedmanLorenzoBertacchiniNo ratings yet

- Traditional Vietnamese Music Has Been Mainly Used For Religious ActivitiesDocument2 pagesTraditional Vietnamese Music Has Been Mainly Used For Religious ActivitiesDuy TrịnhNo ratings yet

- q4 Mapeh 7 WHLP Leap S.test w1 w8 MagsinoDocument39 pagesq4 Mapeh 7 WHLP Leap S.test w1 w8 MagsinoFatima11 MagsinoNo ratings yet

- Hatebreed 2Document4 pagesHatebreed 2frankiepalmeriNo ratings yet

- Dear Guitar Hero OpethDocument3 pagesDear Guitar Hero OpethPedro MirandaNo ratings yet

- Legal Basis of MapehDocument34 pagesLegal Basis of MapehMaeNo ratings yet

- Theory of SongxDocument5 pagesTheory of SongxtiaranasirNo ratings yet

- Rama KausalyaDocument3 pagesRama Kausalyakanya MNo ratings yet

- Beyond Sonata Deformation: Liszt's Symphonic Poem Tasso and The Concept of Two-Dimensional Sonata FormDocument24 pagesBeyond Sonata Deformation: Liszt's Symphonic Poem Tasso and The Concept of Two-Dimensional Sonata FormSamanosuke7ANo ratings yet

- Strauss Trumpet in BBDocument2 pagesStrauss Trumpet in BBStagedoor ManorNo ratings yet