Professional Documents

Culture Documents

029 - 1967-1968 - Law of Contract

029 - 1967-1968 - Law of Contract

Uploaded by

Chakseng chmominOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

029 - 1967-1968 - Law of Contract

029 - 1967-1968 - Law of Contract

Uploaded by

Chakseng chmominCopyright:

Available Formats

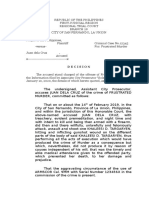

LAW OF CONTRACT*

I. C. SAXENA**

I. Introduction

This is an integrated survey relating to the general principle of law

for the years 1967 and 1968. The codified nature of the law of contract

in this country makes the law certain, and thereby the decisions, predict-

able. It, however, tends to arrest the development of law for the task of

the judiciary is restricted to the applications of principles of law to the

situations, though varying in nature, which come before it from time to

time.

During the survey period, the cases have covered almost all the

important topics of the subject : offer and acceptance, government contra-

cts, consideration, formality of writing and formation of a contract, powers

of a guardian to bind a minor, undue influence, fraud, unlawful agree-

ments including agreements against public policy, agreements restricting

jurisdiction of courts, and agreements in restraint of trade, ambiguous

agreements, time as the essence of contract, law of refund, quasi-contracts

and principles of damages. Herein an attempt is made to deal with these

topics and to show whether or not any new development concerning these

has taken place.

II. Contracts

In one case,' an enactment defined the term contract in a technical

sense for the purposes of that Act. It was contended that this definition!

was controlled by the definition of this term in the Indian Contract Act. It

was held that the definition contained in the former Act was applicable and

that the Indian Contract Act could not detract from the elements of contract

as defined in the former Act.

The Indian Contract Act has no special provrsions relating to the

formulation of government contracts. However, Articles 299(1) of the

• This survey is confined to first is sections of the Indian Contract Act .

•• M.A., LL.M., J.S.D. (Cornell), Reader in Law, University Law School, Jaiput

(Rajasthan).

1. Perfect Pottery Co. v, S.T. Commr., A.I.R., 1967 M.P. 234.

2. See section 4 (1) of the Central Provinces and Berar Sales Tax Act, 1947.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

166 Annual Survey of Indian Law 1967 and 1968

Constitution prescribes the formality which is required to make a govern-

ment contract valid and enforceable. There have been, during the survey

period, two Supreme Court cases," and a few High Court cases.' In view

of these decisions," an unwritten government contract cannot be implied,

since it is required to be in writing. There can, however, be implications

drawn from the written terms of the contract. The Andhra Pradesh, Mysore

and Orissa High Courts were also concerned with the problem whether in

the cases before them the requirements of article 299(1) were complied

with," While the Andhra Court did not consider it necessary to cite, in

support, any case,? the Mysore and Orissa courts cited cases."

On the question of compliance with article 299(1) of the Consti-

tution, there were developments which show that although there may not

be a formal execution of a deed, a contract in writing or by correspondence

would be a sufficient compliance with the constitutional requirements.

III. Offer and Acceptance

The cases which have arisen regarding offer and acceptance deal with

.the following matters : (a) whether the mechanism of an offer and accep-

tance is necessary for the formation of a contract; (b) what constitutes an

offer; (c) formation of a contract and the question of jurisdiction;

(d) formation of an auction-sale contract; and lastly, (e) the scope of

sections 7 and 8.

The Supreme Court case of Andhra Sugar Ltd. v. State of A. P.,'

indicates a trend away from the traditional way of formation of contract

3. K.P. Chowdhry v. State of M.P., A.J.R. 1967 S.C. 203., Mulam Chand v. State

0/ M.P.• A.I.R. 1968 S.C. 1218.

4. Abdul Rahiman v, Sadasiv A.I.R. 1968 OrL 85; Ahmed Mohiuddin v, G. Malia,

A.I.R. 1967 A.P. 26; Firm Lakshminarayana v. State, A.l.R. 1967 Mys, 156.

5. Supra, note 3.

6. Supra, note 4.

7. The case was decided with reference to the Representation of the People Act,

1951.

8. In Firm Lakshminarayana v. State, supra, note 4, the Court followed the decis-

ion of the Supreme Court in Union 0/ India v, Ralhi Ram, A.I.R. 1963 S.C. 1685. There

the written acceptance was signed as : "For Director of Industries and Commerce on

behalf of the Governor of Madras." Id, at 158 (Madras) In the Orissa case of Abdul

Rahiman v, Sadasiv, supra, note 4~ the court followed the Supreme Court case of K.P.

Chowdhury v. State of M.P., A.J.R. 1967 S.C. 203.

9. A.I.R. J968 S.C. 599 ; see also Indian Steel and Wire Products Ltd. v, State of

Madras. A.I.R. 1968 S.C. 478 ; see also the Calcutta High Court decision in Ghollrom

v. State A.I.R. 1967 Cal. 568.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

Law of Contract 167

through offer and acceptance. The Andhra Pradesh Sugarcane (Regulation

of Supply and Purchase) Act, 1961, regulates almost the monopoly of

factory owners to purchase the sugarcane from the cane growers at the

terms dictated by them. The Act disallows the cane growers to make a

direct sale to factory owners. It obliges a factory owner to purchase the

cane offered to him for sale as per the prescribed terms and conditions.

The five-judge bench held that "the (these) agreements are enforceable by

law and are contracts of sale of sugarcane as defined in section 4 of the

Indian Sale of Goods Act."lO

Here the problem arose that if there was a sale of goods, the state

was entitled to tax the sale. Since the pharse sale of goods was passed in

the sense of the Sale of Goods Act, 1930, a contract of sale which included

the formalities of an offer and its acceptance, must exist so that a transaction

may be termed as sale.

In its earlier decision in Madras State v, Gannon Dunkerley P the

Court held that compulsion could not create a valid contract in law. This

earlier decision was explained away in the instant case,1~ by the Court on

the ground that that case did not lay down that where there was a voluntary

offer with an obligation to accept, there was no contract of sale.

The Court admitted that there had been erosion of the philosophy of

laissez-faire in the twentieth century, the Court held that an agreement

made under the compulson of law is not coercion and is, therefore, valid.

It noted that in such a case there is mutual assent and the vitiating causes

such as coercion, undue influence, fraud and misrepresentation or mistake

are absent. But the Court did not refer to the definitions of offer and

acceptance which contemplate willingness on the part of a contracting

party.

The Madras High Court was confronted with the question whether

the words "subject to Madras jurisdiction" printed at the top of the

letter, constituted an offer,"! It was held that it did not, and unless the

offeree made a clear acceptance of it, no contract as to such term was

concluded. The Court also expressed the view that no party could impose

its terms upon the other. This decision cautions that the Court will ascer-'

tain in each case, through examination of the relevant material before it

whether or not there has been an offer or an acceptance.

10. rd. at 604.

11. A.I.R. 1968 S.C. 560.

12. Supra. note 9

13. C. Satyanarayana v. Naraslmham, A.tR.. 1968 AtoP. 330.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

168 Annual Survey of Indian Law 1967 and 1968

In a Mysore case,14 the plaintiff, in response to a call from the

government for tenders, quoted separately rates for two different kinds of

cocoons and deposited Rs, 50/- through challan as required. The

government accepted rates for the one and not for the other. The Court

held that the government's call for tender was an invitation to offer, the

plaintiff's tender was an offer, the government's reply subsequently was an

acceptance. This completed the contract. This analysis is in accordance

with the well-established principles of offer and acceptance as to the tenders

and their application here is sound. Although the judgment does not

mention it, it IS clear that the plaintiff's letter (tender) was not a composite

and integrated offer but a divisible one. Hence the government could

accept the one part and reject the other.

An offer to be capable of acceptance must be definite. It was

thus held 15 that where a person states to the other that he is willing to

purchase the property "at a reasonable price,"l8 it does not constitute an

offer. There is, thus, no question of rejection of it.

In one case," the Delhi High Court had to decide the question of

jurisdiction to try the criminal offence of selling goods obtained under

the actual user's licence. In this case the goods were despatched, under a

.contract, by a firm at Bombay to a firm at Delhi. The proposal was sent

from Bombay and the acceptance, from Delhi. The question before the Court

was where the sale had taken place. The Court held that under section 4

of the Sale of Goods Act, sale is a composite expression and includes

within itself an element of contract, payment of price, passing ofthe title and

delivery of the goods. It further held that since acceptance was despatched

from Delhi, "a part of the agreement of sale, therefore, took place in

Delbi."18 This conclusion is in accordance with the precedents although

the cases were not referred to. 11

In one case," the Patna High Court was concerned with the principles

relating to the formation of an auction-sale contract. The plaintiff made

14. Firm Lakshminarayana v, State, supra note 8. This case also concerned the

question of the compliance with article 299 (1), for which see above.

15. K.S. Thangal v. State, A.I.R. 1968 Ker. 197.

16. Id. at 197.

17. State v. Sinha Govtndji, A.I.R, 1967 Del. 88.

18. u. at 91.

19. Bhagwandas v. Girdharlal & Co., A.I.R. 1966 S.C. 543., Purshottam v, Baroda

Oil Cake Traders, A.1.R. 1954 Born. 491, approved by the Supreme Court in the case

noted herein.

20. Abdul Rahim v, Union of India, A.I.R. 1968 Pat. 433 ; see also the Kerala High

Court case : K.S. Thangal v. State, supra, note IS.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

Law of Contract 169

he highest bid to purchase the evacuee property put to auction by the

government. It was accepted, as per rules, subject to approval by the

Settlement Commissioner. The necessary bid amount of 10 per cent was also

deposited, The plaintiff did not hear of the confirmation for six months,

whereupon he withdrew his bid (offer). Analyzing the situations in

auction sales, the court said that the acceptance may be provisional,

conditional or absolute (in which last-mentioned case, the auctioneer must

have absolute authority to accept). Neither provisional nor conditional

acceptance concludes a contract. The court felt that the matter was

clinched by the Supreme Court case of MIs. Bombay Salt and Chemical

Industries v, L.J. Johnsoni" wherein the sale was subject to approval.

There the Court held that unless the sale was approved, there was no

contract,

In the instant case, the court also referred to an American case,22where-

in an offer of reward was acted upon several years after its advertisment

in a newspaper. It was held that this offer had lapsed and could not be

acted upon, although there was no notice of revocation by the offeror.

The Indian Court cited this case merely to show that the highest

bidder was justified in revoking,23 since his bid was not accepted for six

months. It is submitted that the court could, as well, have decided the

case under section 6 (2) of the Indian Contract Act, according to which an

offer expires after the lapse of a reasonable time. It, however, did not

feel it necessary to do so. This case is an application of the above

dictum of the Supreme Court. It also clearly enunciates the well-known

propositions of law concerning auction-sales, which are the same as in

ordinary offers.

A few cases2' concerned with acceptance by conduct involved references

to sections 7 and 8 of the Indian Contract Act, particularly the latter which

is quoted below:

'Performance of the conditions of a proposal, or the acceptance of

any consideration for a reciprocal promise which may be offered with a

proposal, is an acceptance of the proposal.'

21. A.I.R. 1958 S.C. 289.

22. Loring v. City of Boston, (1844) 7 Metcalf 409

23. Supra, note 20 at 438.

24. Gaddermal v. C. Agarwal & Co., A.I.R. 1968 All. 292; Union of India v, MIS

Babula', A.I.R. 1968 Bam. 294; State v. Inderchand Jain, A.I.R. 1968 Pat. 171.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

110 Annual Survey of Indian Law 1967 and 1968

In the Patna case,25 a government notification stated the minimum

charges for the use of electrical energy in terms of the quantity consumed by

industrial undertakings. The respondents continued to consume the energy,

without demur, at least until they filed the suit. It was rightly held that this

amounted to acceptance by conduct. Here this inference was not difficult.

In the Allahabad case,26 the plaintiff sent to the defendant several standard

forms. They were required to be duly signed and then returned. The

defendant returned some of them duly signed, but others were not returned.

The plaintiff had read over to the defendant the prescribed terms, including

the one referring to compulsory arbitration. There "was prior agreement.. i

that the contract forms if not returned unsigned with a letter shall amount

to acceptance of the transactions noted therein."?'

The question before the court was whether the omission of the defen-

dant to return the unsigned contract forms amounted to acceptance under

section 7 of the Indian Contract Act. The court quoted and examined

sections 7 to 9 of this Act. It held that an acceptance may be either express

or implied; an implied acceptance can be made under section 8, which is

merely illustrative and not exhaustive as shown in an earlier decision

of this court in Gaddarmal v, Tata Industrial Bank, Ltd. 28 The

court opined that acceptance can be made in forms other than those in

sections 7 and 8 and gave an example that if the parties agree they could

validly stipulate that all books sent by a bookseller to a person if not retur-

ned by him within three days shall be deemed to have been purchased. A

contract so formed was, in its opinion, neither against public policy

nor vague or unreasonable. It is submitted that the contract in the above

case is implied under section 9, because, as the section declares, in so fat

as such proposal or acceptance is made otherwise than in words, the promise

is said to be implied.

In the other Bombay case,19 the court examined the scope of

section 8 of the Indian Contract Act. Here, through the negligence of the

railway authorities, certain goods were lost. The plaintiff served notice

on the railways. He also stated that the railways were in the habit of

sending cheques for smaller amounts in satisfaction of the full claim and

indicated that he would accept the cheque only as part-payment.

The railways sent the cheque with the usual printed conditions, as expected.

It was held that the plaintiff by his acceptance under these circumstances

25. State v. lnderchand Jain, A.I.R. 1968 Pat . 171.

26. Gaddarmal, v, C. Agarwal 4 Co., supra note 24.

27. Id. at 295.

28. A.I.R. 1927 All. 407.

29. Union of India V. MIS Babulal, supra, note 24.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

Law of Contract 111

was not barred by section 63, Indian Contract Act, which deals with

remission of performance of promise. The court stated that here sections

7 and 8 were to be read together. A conditional acceptance under section

7 did not operate as an unconditional acceptance under section 8. The

court examined numerous cases before stating this conclusion.

These cases mark the development of the law of acceptance by conduct

and redefine the scope of sections 7 and 8.

In Subbaya v. V. Krishnas" the court held that there was no accord

and satisfaction unless payment was actually made and accepted; mere

agreement is insufficient.

IV. Consideration

Both the Supreme Court and the High Courts dealt with different

situations under this head.

Q. Equitable Estoppel

In Union ofIndia v, Indo-Afghan Agencies," the question before the

court was whether if a person had acted on the representation or assurances

of the government, the government was bound to honour its assurances.

Without discussing the requirements of a valid contract under article

299 (1) of the Constitution and rejecting the doctrine of executive

necessity, Justice Shah, as he then was, delivering the judgment of the

Court, said :

We are unable to accede to the contention that the executive

necessity releases the Government from honouring its solemn

promises relying on which citizens have acted to their

detriment.P

In this case, the Indo-Afghan Agencies at Amritsar exported woollen

goods to Afghanistan under the Export Promotion Scheme of the govern-

ment which entitled it to an Import Entitlement Certificate of a certain

value. The government, however, granted them a certificate of less value.

The Supreme Court allowed the claim of the Agencies on the basis

of the equitable doctrine, which is different from the doctrine of estoppel

in section 115 of the Indian Evidence Act 1872, which is a rule of

evidence.

30. A.I.R. 1967 A.P. 44.

31. A.I.R. 1968 S.C. 718 (change made from UAnglo" to "Indoh ) .

32. Id. at 723.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

Annual Survey of Indian Law 1967 and 1968

The court thus innovated the doctrine of equitable estoppel against

the government if a person had injuriously relied on its assurances or

representations

(b) Past Cohabitation

In D. Nagaratnamma v, Kunuku Ramayya,33 the question of

consideration for past cohabitation arose in connection with the validity

of certain property transactions which had been made by the deceased. Here

a Karta (Manager) transferred the joint family properties by way of sale to

his concubine. On severance of the joint family and after the death of the

Karla the widow and the four sons sought to recover the properties from

the concubine on the ground that the transfer being without consideration

and for immoral purposes was without consideration. It was found that the

transfers were without exchange of any consideration, cash or delivery of

jewels. The High Court 'held that the two deeds, though purported to be

sale-deeds were in reality gifts and were made in view of the past illicit

cohabitation with her, which constituted the motive and not the considera-

tion. The appellant (concubine) contended that her past cohabitation was a

past service and, therefore, a valuable consideration: The Supreme Court

found:

The two agreed to cohabit. Pursuant to the agreement each

rendered services to the other. Her services were given in

exchange for his promise under which she obtained similar

services. In lieu of her services, he promised to give her

services only and not his properties. Having once operated

as the consideration for his earlier promise, her past services

could not be treated under section 2 (d) of the Indian Contract

Act as a subsisting consideration .... 84

Thus while an agreement to transfer property in future would be

void under section 23, there could not be past consideration on the mutual

service theory as in the above case.

(e) Reconveyance Provision

In a Madras case," the question arose whether an agreement to

reconvey property was without consideration and whether the reconveyance

provision amounted to an agreement or merely to a standing offer.

33. A.I.R. 1968 S.C. 253.

34" u. at 254.

35. Board of Revenue v. Annamalai &: Co., A.I.R. 1968 Mad. SO.

36. Safiya Bi v, Shukoor Sahite, A.I.R. 1967 Mad. 375.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

Law of Contract 173

Here the plaintiff'sold property to the first defendant for Rs. 8000. On

the same date, the parties entered into a written agreement whereunder the

latter agreed to reconvey the property to the plaintiff, if the right or

option was exercised beyond a fixed date before the expiry of a specified

date, within a specified date, within a space of five years. The vendee,

within the reconveyance period, sold the property to other defendants

with the reconveyance provisions. The plaintiff exercised his option within

time and claimed back the property. Following the decision of the Judicial

Committee in Sakalaguna Naidu v, Chinna Munusami NayakkarP the

court held that the option provision was not a mere standing offer; that

the offeror could not withdraw his offer; it had all the elements of a

completed contract. As to the consideration, it said:

Under such circumstances the sale deed and counter part must

be read as constituting a total system of rights and obligations,

mutually supported by consideration and that, further, the

undertaking to reconvey was specifically enforceable as such."

The Court also referred to its earlier decisions." Regarding the

validity of reconveyance agreements, the court remarked that a situation

of this kind "is well recognised and, indeed, of almost daily occurrence

in courts".S9 This, no doubt, is true. A reconveyance provision being a

contract and not a mere offer can be legally assigned and does not expire

on the death of the offeror or offeree.

d. Promise to Pay Time-Barred Debts

Section 25 of the Indian Contract Act lays down the rule as to the

requirement of consideration and it also provides tbree exceptions to it.

Under sub-section (3), an agreement, though without consideration, will not

be void if:

it is a promise made in writing and signed by the person to be

charged therewith, or by his agent generally or specially

authorized in that behalf, to pay wholly or in part a debt of

which the creditor might have enforced payment but for the

law for the limitation of suits.

In a Patna case," a money-lender filed a suit for the recovery of the

37. A.lR. 1928P.C. 174.

38. Supra, note 36 at 378.

39. ld. at 380 ; see the cases mentioned by the court.

40. Brij Bihar; v, Bir Bahadur, A.I.R. 1968 Pat. 203 ; see also Darga Prasad v, Fateh

Chand, A.I.R. 1968 Cal. 292.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

174 Annual Survey of Indian Law 1967 and 1968

amount due on the basis of an entry in the chitha (account book) which

had been signed by the debtor.

The question was whether this was a mere acknowledgment, without

being a promise to pay under the above section. The court held that it was

a promise to pay, so that the chitha furnished a cause of action, the suit

having been filed more than three years after the date of the original

loan.

In the Madras case,41 the husband of the defendant had executed

a promissory note in favour of the plaintiff. This bond had become

time-barred, and hence, unenforceable. The defendant then executed a

promissory note in favour of the plaintiff in purported renewal of the said

note. It was held that the defendant's note was without consideration and

further the wife was not the agent of the husband under sub-section (3)

above. The Court followed a Bombay case's which was found to be on

all fours with the instant case.

In the Orissa case,43 the plantiff gave a loan of Rs. 5000 to the

deceased on JUly 9, 1951. The latter executed a handnote one or

two days before 9-7-1954. 4' The handnote was renewed by the deceased

on August 9, 1957, after it was barred by time. It was held that the

promisor was entitled to claim aginst the legal representatives out of the

property received by them from the deceased under section 25 (3), since

all its ingredients were satisfied. The court did not discuss the point at

length, nor did it refer to any authority.

Thus both the Supreme Court cases lay down new doctrines which

make a definite development over the existing state of law. At the High

Court level, the situations in some cases were novel but the courts did

not feel any difficulty in the application of the existing law to these.

v, Formality of Writing

Sometimes the agreement between the parties provides for a writing or

further writing. The question arises whether or not a valid and enforceable

contract has come into existence, if the agreement is not reduced to

writing.

41. Perumayammal v. Chinnammal, A.I.R. 1967 Mad. 189.

42. Pestonji v. Bai Meharbai, A.l.R. 1967 Mad. 189.

43. Mawa]i Ramji v, Premji Kumbhabhai, A.I.R. 1967 os. 158.

44. ld. at 159.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

Law 01Contract 175

In the Supreme Court case of K. Sriramulu v. Aswatha Narayana,"

except the mode of payment of the purchase price, all the terms had been

agreed upon. The Court held that since all the vital terms as to price, the

total area of land and the time for the completion ofthe sale had been fixed

by the parties, the mere omission to state the mode of payment does not

make the contract incomplete. The following principles emerge from the

decision:

1. The mere fact that the parties provided for a formal written

document is not conclusive proof that they had not yet entered

into a binding contract.

2. The court will look into evidence to ascertain the intention of the

parties as to the binding nature of a provision for writing.

3. If the omission to agree upon certain terms is negligible and

the agreement is otherwise complete in all its vital aspects, the

provision for a formal document may be regarded as recommenda-

tory and not commendatory.

In a Madras case,46 the mechanism of offer and acceptance had been

complied with, but one of the conditions in the invitation to tender by the

government had provided for execution of the agreement on a stamped

paper and had also asked for earnest money. It was held that the Jack of

these two things did not detract from the completion of the contract. Here

the court followed the decisions of the Privy Council." The law on the

subject may be regarded as already settled.

VI. Contract of a Hindu Guardian

The powers of a Hindu guardian, natural or de facto, are now

circumscribed by the Hindu Minority and Guardianship Act, 1956. In a

Madhya Pradesh case," the mother, a natural guardian, entered into a

contract in 1961, on behalf of the minors for the purchase of a house for

Rs, 11,000; Rs. 1000 was paid as earnest money and the balance was to

be paid at the time of the execution of the the sale-deed. Since the vendor

refused to execute the deed, the minors, through the mother (natural

guardian), sought the enforcement of the agreement. The court pointed

45. A.I.R. 1968 S.C. 1028.

46. Firm Lakshminarayana v. State, supra, note 4.

47. Currimbhoy & Co. Ltd. v. L.A. Creet, A.l.R. 1933 P.C. 29 ; Harichand v, Govind

Luxman, A.I.R. 1923 P.C. 47.

48. Ramchandra Y.. Manikchand, A,lR. 1968 M.P. 150.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

176 Annual Survey of Indian Law 1967 and 1968

out that after the passing of the Hindu Minority and Guardianship Act,

1956, under section 8 (2), the powers of a natural guardian to transfer the

minor's property for legal necessity can be exercised only with the permission

of the court. It expressed, therefore, that the dictum of their Lordships of

the Privy Council in Subrahmanyam v, Subba Rao,49 yields to that of the

same court (by Lord Mcnaghten) in Mir Sarwarjan v. Fakhruddin": The

Court, thus held that the agreement could not be enforced at the instance

of the minors.

It is submitted that section 8 (2) of the Hindu Minority and

Guardianship Act refers to sales and not to purchase of properties. And

furthermore even in case of a disposal of property in contravenion of the

above requirement, under sub-section 8 (3), such disposal "is voidable at

the instance of the minor or any person claiming under him." In view of

this, the decision and dictum of the court must be accepted with caution.

In one case," the Delhi High Court left the question open whether

under certain circumstances, the guardian can "bind the minor by a

contract for purchase of shares and whether or not such minor can be

placed on the register of members. "51

VII. Undue Influence

A couple of cases63 were concerned with the law of undue influence.

Section 16 (2) of the Indian Contract Act states:

In particular and without prejudice to the generality of the

foregoing principle, a person is deemed to be in a position to

dominate the will of another:

(a) where he holds a real or apparent authority over the other, or

where he stands in a fiduciary relation to the other; or

(b) where he makes a contract with a person whose mental capacity

is temporarily or permanently affected by reason of age, illness,

or mental or bodily distress.

In one Supreme Court case 54, P, who owned land in two villages, bad

two sons and a daughter. One son, the plaintiff, was childless, and the

49. A.T.R. 1948 P.C. 95.

50. (1912) 39 I A. 1.

51. Golconda Industries v. Companies Registrar, A.l.R. 1968 Del. 170.

52. rd. at 172.

53. Subhas Chandra v. Ganga Prasad, A.I.R. 1967 S.C. 878; Ningawwa v, Byrappa.

A.I.R. 1968 S.C. 956.

54. Subhas Chandra v. Ganga Prasad, Ibid,

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

Law of Contract 177

other son had a son, Subhas Chandra. The latter son along with his

family bad always been living with his parents and had never been

employed outside the tOWD. The plaintiff was livinig away from his

parents, and was also looking after the property of his father for some time.

P made a deed of gift in favour of his only grandson (Subhas Chandra)

for the love and affection which he had towards the donee and the respect

which the latter had towards the former. Four years after the death of the

donor and eight years subsequent to the transaction, the plaintiff challenged

the validity of the gift. The High Court held that under the circumstances

of the case and the relationship of the parties, the court should have

made a presumption that "the donee had influence over the donor."55

The Supreme Court held that the law of undue influence was the

same in cases of gifts inter vivos and contracts. It did not agree with the

presumption theory of the High Court. It held that all the ingredients of

undue influence as per section 16 must be proved. Looking to the facts

of the case, the Court held that the donee was not in a position to

dominate the will of the donor: the gift by the grandfather to his grandson

of a portion of his property was not, on the face of it, unconscionable.

The Court also took note of the fact that if the second son wanted to use

influence over their father, he would have liked the gift to operate in hill

own name for the son, on attainment of majority, "may have nothing

to do with his father. "58 The view of the Supreme Court that the essentials

of undue influence should be proved and that presumption could not

be raised is, of course, a sound one. There may, however, be a

circumstance, as in the case of husband and wife, where one is in a

dominant position in relation to the other."

VIII. Fraud

In one case," the Supreme Court pointed out that where there is a

fraudulent misrepresentation as to the nature and character of a document,

the transaction is void. If, however, the misrepresentation relates to the

contents only, it is voidable. In this case, a lady had made a deed of gift

in favour of her husband, but the latter fraudulently included a plot in

-the deed which was not intended to be gifted by the donor. The Court

held that the character of the document being the same, the transaction

was merely voidable. The distinction between "void" and "voidable"

55. Id. at 879.

56. [d. at 884.

57. See Ningowwa v, Byrappa, supra, note 53,

~8. Ibid,

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

178 Annual Survey of Indian Law 1967 and 1968

here is important in view of different legal consequences which follow in

these two cases.

In one Patna case,s, it was pointed out that the father is in a

fiduciary relation to the daughter, so that he is under a duty, as per

illustration (a) of section 17, to disclose all true facts to her. This is,

doubtless, an established principle of law.

IX. Unlawful Agreements: Public Policy

Section 10 of the Indian Contract Act declares that an agreement is

enforceable if it is made "for a lawful consideration and with a lawful

object" and is not "expressly declared to be void." Under section 23 of

the Act, the consideration or object is unlawful if:

it is forbidden by law; or

is of such a nature that, jf permitted, it would defeat the

provisions of any law; or

is fraudulent; or

involves or implies injury to the person or property of another;

or

the Court regards it as immoral, or opposed to public policy.

The section declares such agreements to be void.

During the survey period, numerous cases arose under section 23,

some were entwined with section 28 and some others with section 65

discussed below at appropriate places. Even with regard to agreements

falling solely within the ambit of section 23 there have been several situa..

tions, many traditional, but some novel.

(a) Transfer Cases

The Supreme Court has held that a contract of pre-emption is not

against public policy." There is, obviously, a long usage sanctioning

pre-emption. In another Supreme Court case," there was an agreement

59. Babui Panmato v, Ram Agya Singh, A.I.R. 1968 Pat. In this case, there was a

fraudulent misrepresentation to the petitioner (the daughter) with a view to "procure her

Consent to the marriage". [d. at 192.

60. Ram Baran v, Ram Mohit, A.I.R. 1967 S.C. 744.

~1. Satappa v. Appayya, A.I.R. t9(j8 S,C, 1358.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

Law 0/ Contract 179

between two agriculturists to transfer agricultural land. But if the

agreed land was transferred, the transferee would possess land beyond

the ceiling prescribed in the Bombay Tenancy and Agricultural Lands

Act. The trial court held that if the agreement was enforced, it would

defeat the provision of the Bombay Act. The Supreme Court, however,

held that the object of the agreement was not in itself unlawful, only the

land in excess of the ceiling would vest in the government. In two cases,'1

decided by the High Courts, there were specific enactments which

expressly prohibited transfers. In one of these,63 the defendant who had

a licence to sell liquor in his own name, could not enter into a partnership

to sell liquor because it was a prohibited transfer within the meaning of the

Hyderabad Abkari Act. In the other." a licence under the Indian

Electricity Act, 1910, was held not negotiable. Here the transfer was

prohibited, but no punishment for transfer was provided. The court held

that the provisions of section 23 were, nevertheless, attracted. It also laid

down two more principles: (1) what the law prohibits to be done directly,

cannot be legalised by being done indirectly; (2) the object of the

legislature would be taken in view before knocking the agreement down on

the ground of unlawfulness. An agreement contrary to the policy of the

Act is contrary to public policy. These principles are sound.

Furthermore, a company cannot disclaim its statutory liability to pay

bonus on the basis of a contract with its employees." An agreement between

the co-sharers which leads to peace between them is not against public policy.

Thus where the agreement provided that one of the two co-sharers would

not open a door on the jointly owned plot of land which lies between two

parcels of land belonging to the co-sharers individually, it does not amount

to a surrender of the land to the other, nor does it amount to its usurpation

by the other person."

b. Unlawful Consideration

A promissory note which is based on a wager will not be enforced

for the consideration of the note is unlawful. 67 Again in a Madras case,"

62. Dinshamii v. Abdul Rasool, A.tR. 1967 A.P. 119 ; Murli Prasad v, Parasnath

Prasad, A.I.R. 1967 Pat. 191.

63. Dinshamji v. Abdul Rasool, A.I.R. 1967 A.P. 119.

64. Murli Prasad v. Parasnath Prasad, supra, note 62.

65. U.P. Electric Supply Co. v. n.v. Bowen, A.I.R. 1968 All. 95, see also Administra-

tor H. C. Ltd. v. J.K. Das, A.I.R. 1968 Cal. 146.

66, Chajjulal v. Ram Pal, A.I.R. 1968 AU. 79.

67. Badridas Kothari v. Meghraj Kothari, A.I.R. 1967 Cal. 25.

68. Maniflfa v, MU1!ial1?'nal~ ;\.I.R. 1968 M~~. J92. see also supra, note 33,

,

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

180 Annual Survey of Indian Law 1967 and 1968

the defendant executed a promissory note in favour of the plaintiff, a

married woman, ostensibly for past cohabitation, for Rs. 810. It was

held that there was no valid consideration under section 23 of the Indian

Contract Act. The court stated that whether or not the sexual relationship

between the parties constitutes a criminal offence, both these cases fall

within the above section. The court will promote sexual relationship

within the sphere of matrimony.

c. Agreement Stifling Prosecution

I n a Kerala case,69 the secretary of a co-operative society had

disappeared with the money. The executants of a bond, relatives of the

secretary, sought to protect the secretary. The Court found that the

purpose of the bond was that the police authorities to whom the

information had been conveyed should be told by the president, the

holder of the note, that there was no necessity to proceed with the

case. In fact, the president next day, did accordingly. It was held that

the object and consideration of the bond is to muzzle the prosecution.

Hence money could not be recovered on the note. This principle of law is

well-established; here the court referred to numerous decisions, including a

Privy Council case. 70

d. Government Contract and Public Policy

In one Madras case", it has been held that if a government contract

prohibits assignment and sub-letting, the contract of sub-letting does not

become opposed to public policy, nor does such a contract become ilIlegaI.

This is based on the ground that the Indian Contract Act does not treat

the government contracts, either in their formation or in their

enforceability, on any footing different from ordinary contracts. This is,

no doubt, a novel fact situation.ts and the court rightly demarcated the

scope of section 23.

e. Miscellaneous Cases

A lender is not bound to see to the actual application of the money,

whether for causes promoted by law or for causes prohibited by it.

Similary, where a lender has advanced a loan for a purpose which

ostensibly is not prohibited by law, and yet on examination of the

69. Narayana Ptllai v K.R S. Co-op Society, A.I.R. 1967. Kef. 51..

70. Kamuni Kumar v. Briendra Nath, A.T.R. 1930 P.C. 100.

71. Meikole v. Periasami, A.l.R. 1967 Mad. 449.

72. The court did not refer to any case on the subject.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

Law of Contract 181

situation he would have known the truth, he will not be debarred

from suing on the note. Thus in an Andhra Pradesh case," the lender

advanced a loan to the borrower for the marriage of the latter's daughter.

This marriage was opposed to the provisions of the Child Marriage

Restraint Act, but the recovery was allowed on the above principle. The

court followed its earlier decision on the subject.

An agreement between the married couple to live separately was held

as no answer to the wife's suit for restitution of conjugal rights. Such an

agreement, whether pre-nuptial or post..nuptial, is opposed to the conditions

of Hindu society and, therefore, it would be void under section 23. 74

x. Agreements Concerning Jurisdiction

One of the agreements of common occurrence relates to the choice of

jurisdiction. Such a situation falls for consideration within the scope of

section 23 and 28, read together. Section 28 reads, in part:

Every agreement, by which any party thereto is restricted

absolutely from enforcing his rights under or in respect of any

contract, by the usual legal proceedings in the ordinary tribunals,

or which limits the time within which he may thus enforce his

rights, is void to that extent.

This section saves arbitration agreements. In one Patna case," the

issue was whether the suit could be filed at Patna or Bombay. The

parties, no doubt, preferred Bombay. The trial court held that though the

agreement was not barred by section 28, it was against public policy

under section 23. The Patna High Court referred to the decisions of the

Allahabad, Bombay, Calcutta and Madras High Courts and remarked that

the law on the subject was well settled which upheld the above kind of

agreement between the parties. It, however, noted a single decision of the

Madhya Bharat High Court in Dwarka Rubber works v, Chhotelal," which

held to the contrary. But the court dissented from it. In the instant

case therefore, the Patna Court had no jurisdiction. In a case" during the

survey period, the Rajasthan High Court expressed the view that "it has been

73. Punnakotiah v. Kolikmba, A.I.R. 1967 A.P. 83. Here Lakkimsetti Ranganayaku/u

v. B. Narayanaswami, (1958) Andh. L.T. 14 was followed.

74. Thirumal Naidu v. Rajamunal, A.I.R. 1968 Mad. 201.

75. Ajamera Bros. v. Suraj Mal, A.I.R. 1968 Pat. 44.

76. A.I.R. 1956 Madh. B. 120.

77. Singhal Transport v. Jesaram, A.I.R. 1968 Raj. 89.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

182 Annual Survey of Indian Law 1967 and 1968

held in a number of decisions'?" that such an agreement is not contrary

to public policy. This court also dissented from the Madhya Bharat

case referred to above.

A clause in an agreement providing that legal proceedings may be

instituted within three months of the rejection of the claim by the company

is not hit by section 23 and section" of the Act. It was held that a proper

appreciation of section 28 lay in the recognition of the distinction between

extinction of a right and the loss of a remedy. 7P Section 28 barred only

those agreements which took away the right to sue at any time or for a

limited time.

XI. Restraint of Trade

A solitary case decided by the Supreme Court during the survey

period, dealt with the validity of a service clause vis-a-vis the law

relating to restraint of trade." Here the appellant was appointed as shift

supervisor in the type cord division of Century Rayon. He executed

a contract in a standard form, clause 17 of which read as follows:

In the event of the employee leaving, abandoning or resigning

the service of the company in breach of the terms of

the agreement before the expiry or...

five years he shall not

directly or indirectly engage in or carryon ... the business at

present being carried on by the company and he shall not

serve in any capacity, whatsoever or be associated with a person,

firm or company carrying on such business for the remainder

of the said period... 81

There was a further provision as to payment of liquidated damages,

and also the refund of the expenses incurred on the employee's training.

Under an agreement with a West German firm, the company was

committed to secrecy as to technical know-how. The employee received

the training, including technical knowledge, After serving the company for

less than a year, the employee took up a job in a rival concern. The

employer sought the enforcement of the contractual terms. The appellant

(employee) challenged the agreement, inter alia on the ground that it was in

restraint of trade and, therefore, against public policy.

78. Id. at 92.

79. Kasim Ali v. New India Assurance c«, A.I.R. 1968t J. & K. 39 seealso Sodal'"

Singh v. Sham Kaur A.I.R. 1968 Punj. 341, 343.

80. N.S. Golikari v. Century S. and M. c«, A.I.R. 1967 S.C. 1098.

81. u. at 1099.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

Law of Contract 183

After an examination of several English and Indian decisions, the

Supreme Court upheld the validity of clause 17. It noted the

distinction between restraints applicable during the period of employment

and restraint applicable beyond the service period. It held that a negative

covenant of the first type is not a restraint of trade within section 27,

unless the contract is unconscionable or one-sided. Clause 17 was thus

held valid and not opposed to public policy. The decision of the Supreme

Court is in accordance with the pre-existing law. Its seal of approval,

however, makes the law certain and authoritative.

XII. Ambiguous Agreements

According to section 29 of the Indian Contract Act, an agreement,

the meaning of which is not certain, or capable of being made certain,

is void.

This is reinforced by appropriate illustrations. A couple of cases

arose during the survey period pertaining to this subject. 82 In a Calcutta

case,83 the parties provided the following arbitration clause:

In case of any dispute arising between the parties, the matter

should be referred to the arbitrators, elected by the parties and

their decision on the subject will be final.

It was held that this provision was vague, since the parties had not

provided for the actual number of the arbitrators, nor was this provision

capable of being made certain otherwise. Hence the clause was

unenforceable. In the Gujarat case,84 a compromise decree, inter alia,

provided:

Each party has to sell to the other respective portions of the

properties which have come to their share as above at a price

fixed by two members of the Panchas when either party wants

to seIl its share."

The court held that the word Panchas meant arbitrators." If the

clause meant that the price had to be fixed by the two arbitrators, one to be

appointed by each party, there would be no ambiguity if one party refuses

to appoint its arbitrator. For, in such a case, under section 9 of the

82. Teamco (P) Ltd. v. T.M.S. Mani, A.I.R. 1967 Cal. 168; Bai Mangu v, Bai rou;

A.I.R. 1967 Guj. 81.

83. Teamco (P) Ltd. v, T.M.S. Mani, A.I.R. 1967 Cal. 168.

84. Bai Mangu v. Bai Vij/i, supra, note 82.

85. [d. at 82.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

184 Annual Survey of Indian Law 1967 and 1968

Arbitration Act, a willing party may appoint a sole arbitrator. Even if

the provision meant that the two arbitrators should be appointed with the

mutual consent of the parties, and if they fail to agree, under section 8 of

the Arbitration Act, the Court may appoint an arbitrator. Hence here

the clause was capable of being made certain.

These two cases illustrate section 29 fully. While a court will

do its best to see that agreements are not struck down if they are capable

of being made certain, it will not make a contract for the parties. These

cases apply the statutory provisions to the facts, but do not constitute any

new development of law.

XIII. Time as of the Essence of a Contract

The Supreme Court case of Gomathinayagam Pillai v, Palaniswami

Nadar,86 was concerned with the question whether in the situation at

hand time was of the essence under section 55 of the Indian Contract Act.

Here in March 1959, the parties made an oral agreement for the sale of land.

They had, however, not fixed the time for completion of the sale. The

sellers received some advance and passed over a receipt therefor to the

vendee. On further receipt of the amount, the vendors executed an

agreement in writing stipulating that the sale would be completed by

April 15, 1959. A default clause was provided for either party. The

vendee defaulted. The Supreme Court by majority held:

1. That the agreement did not either expressly or by necessary

implication make the time as of the essence.

2. That the mere fact that the parties had fixed the time for

completion of the contract did not by itself make time as of the

essence.

3. That the default provision did not unambiguously do so.

4. That in transaction of sale of land there is a strong presumption

as to the time not being vital for performance. There must be

strong circumstances to dispel such a presumption.

5. That if the time was originally not of the essence, the vendors

could send a notice to the vendee that he must perform the

contract within the stipulated time and that failure to do so will

cancel the contract.

86. A.I.R. 1967 S.C. 868.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

Law of Contract 18S

In the instant case, the vendors had served no such notice; their

treating the contract as being at an end through a letter was not equivalent

to the above notice.

The defaulting vendee in a suit for specific performance must prove

that he had been ready and willing to perform his part of the contract at

all material times. If he so proves, his delay notwithstanding, a decree of

the specific performance will be gran ted. On the facts, here the vendee's

suit for the specific performance could not be decreed since he was found

not to be ready and willing to perform his part of the contract."

The principles laid down by the Supreme Court will serve as

guidelines to lower courts in India. The fundamental rule of presumption

in case of sale of land was, doubtless, an already established principle.

In a Madras case" reported during the survey period, the same rule

was applied on the basis of a Privy Council decision."

XIV. Frustration of Contracts

Frustration as a mode of discharge of a contract is a well established

principle. In India sections 32 and 56 deal with it. There have been

three Supreme Court cases during the period under review."

In one of these cases." a government notification prohibited future

contracts as to the delivery of sugarcane and gUT from an appointed date,

except with a permit; the outstanding contracts were not affected at all.

The Supreme Court held that mere restraint subject to obtaining of a

permit, was not frustration within the contemplation of section 56 of the

Act. The difficulty in securing a permit was not equivalent to a prohibition

so as to attract this section. This is, no doubt, a correct interpretation.

In the other case,92 the parties agreed to the sale of Pakistan jute,

which was subject to import regulation. On the date of the contract,

87. In his dissenting opinion in this case, Justice Bachawat differed as to the

appreciation of the evidence by the trial court, which had been accepted by the majority

as to the readings and willingness of the vendee to perform his part of the contract.

88. Narayanaswami v. Dhankoti Ammal, A.l.R. 1967 Mad. 220.

89. Jamshed Khodaram v. Burporji Dhunjbhai, A.I.R. 1915 P.C. 83, 84.

90. Mohan Lal v. Grain Chambers, A.I.R. 1968 S.C. 772; Naihati Jute Mills v,

Khyaliram, A.I.R. 1968 S.C. 522; Dhruv Dev v. Harmohinder Singh A.I.R. 1968 S.C.

1024.

91. Mohan Lal v. Grain Chambers, Ibid. See also Umar Noor v. Dayal Saran, A.LR.

1967 All. 253 concerning the obtaining of the sanction of the collector to selJ the

land.

92. Naihati Jut» Mills v. Khyaliram, supra. note 90.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

186 Annual Survey 0/ Indian Law 1967 and 1968

there existed a government notification whereunder the import of jute

from Pakistan was restricted to the absolute minimum. The parties had

clearly foreseen the situation and had envisaged that it was the duty of

the buyers to provide the sellers with a licence. Subsequent to this

agreement, another government notification announced that the licence

would be restricted to import one Maund of Pakistani jute as against five

maunds of purchase of Indian jute by the applicant (i.e. in the ratio of 1:5)

and that the latter should not have stock of goods to last for more than

two months. The application of the buyers for licence was rejected on this

last mentioned ground. ]0 other words, due to default of the buyers, the

lincence could not be granted. It was held that both the parties had foreseen

the difficulties involved in obtaining the licence and since there was no

total prohibition to import the goods in question, there was no

frustration.

The court reiterated its earlier view in Satyabrata v. Mugneeram,a

that section 56 lays down "a rule of positive law and did not leave the

matter to be determined according to the intention of the parties. "94

Section 56 does not apply to those cases where the frustrating event arises

under the implication of the contract. In such a case, frustration occurs

because of the contract. Section 32 would be applicable here, but not

section 56. In cases falling under section 56:

The Court can grant relief on the ground of subsequent

impossibility when it finds that the whole purpose or basis

of the contract was frustrated hy the intrusion or occurrence

of an unexpected event or change of circumstances which was

not contemplated by the parties, at the date of the contract."

Thus if the change of circumstances is so fundamental that it goes to

the root of the contract, the contract would be frustrated under section 56.

Both the language of the section and the illustrations appended thereto

support this construction.

In the third case, the Supreme Court settled one of the vexed

problems in the field of frustration of contract. The Court was called

upon to decide whether the doctrine of frustration applied to (agricultural)

leases. In the very peculiar facts of the case, it answered the question in

the negative. Hitherto, the Indian decisions on the subject were not

93. A.I.R. 1954 S.C. 44.

94. Naihati Jute Mills v. Khyaliram, supra, note 90

95. Id. at 527.

96. Dhruv Dev, v. Harmohinder Singh, supra, note 90.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

Law 01 Contract 181

uniform. Nor did they comprehensively deal with the problem. The

interrelationship between the relevant provision of the Indian Contract Act

and those of the Transfer of Property Act on frustration of leases of

immovable property was not examined in those decisions.

One, Kanwar Rajendra Singh, being minor, was under the court of

wards, and, owned, inter alia, five squares of land in Okara in the district

of Montgomery. The Deputy Commissioner, Kangra, who managed this

esta te, invited tenders for demising the land on lease for "a period of one

year, namely, for Khariff 1947 and Rabi 1948."97 The plaintiff's tender

was accepted, and he paid the whole of the amount of Rs.l1,125 to the

Deputy Commissioner as per the terms of the tender, before February 1947.

The plaintiff held the leased land in the preceding year also. He continued

with the possession of this land under the present demise. After the

partition of India, the above land went to Pakistan. Due to riots, the

plaintiff and some of his Hindu tenants were forced to migrate to East

Punjab in the month of August, 1947. The plaintiff, thus, could not stay

on in Okara to harvest the Khariff crop which would have been ripe

sometime in September. He, therefore, claimed the refund of the lease

money.

Although the Transfer of Property Act does not as such apply in

the Punjab, its principles are generally applied on the basis of equity.

In this case, the Punjab High Court and also the Supreme Court

did consider the application of the following sub-section of this Act to the

situation at hand, although agricultural leases are outside the purview of

the Act unless the state government extends the Act to such leases.

The trial court decreed the plaintiff's claim under the doctrine of

frustration; the High Court, however, reversed the decree, holding that this

doctrine did not apply to leases, and the Supreme Court, by Mr. Justice

Shah, upheld the High Court decision and dismissed the appeal.

The Supreme Court considered the appeal on the following findings

of the High Court:

After obtaining possession of lands from the Court of Wards

the appellant carried on agricultural operations for Khariff

cultivation and 'partly enjoyed benefit therefrom by taking

fodder etc' ; that the right to the demised land continued to

remain vested in the appellant even after he migrated to India,

97. Courtof Wards v, Dharam Dev Chand, A.I.R. 1961 Puni. 143, before the case

reached the Supreme Court as DhruvDev v, Harmohinder Singh, supra, note 90.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

188 Annual Survey of Indian Law 1967 and 1968

that the lands demised were neither destroyed not had they

become permanently unfit for the purpose of agriculture, and

that there was no agreement-express or implied-that the

rent was payable only if the appellant was able personally to

attend to or supervise the agricultural operations."

In order to appreciate the controversy the following statutory

provisions may be quoted. The Transfer of Property Act, 1882, section

108 (e) provides:

If by fire, tempest or flood, or violence of an army of a mob or

other irresistible force, any material part of the property be

wholly destroyed or rendered substantially or permanently unfit

for the purposes for which it was let, the lease shall, at the

option of the lessee, be void:

Provided that, if the injury be occasioned by the wrongful act

or default of the lessee, he shall not be entitled to avail himself

of the benefit of this provision.

Section 56 (2) of the Indian Contract Act, 1872 reads:

A contract to do an act which, after the contract is made

becomes impossible, or by reason of some event which

the promisor could not prevent, unlawful, becomes void when

the Act becomes impossible or unlawful.

The Supreme Court judgment deals with two points: the relevance

of foreign law in the Indian contractual jurisprudence, and the

applicability of frustration to leases.

The Supreme Court reiterated the view stated in its earlier decision

in Satyabrata Ghose v, Mugneeramr" that section 56 exhaustively deals

with frustration of contract. It expressly overruled the contrary holding

of the East Punjab High Court in Parshotam Das v, Batala Municipality P"

The COUlt, therefore, rightly said that the citation only of American and

Scottish decisions served "no useful purpose'U'" Reference, thus, to

foreign jurisprudence and case law are redundant, if an Indian statute

exhaustively deals with a situation. This theme and warning of the

98. Dhruv Dev v. Harmohinder Singh, supra note 90 at 1025.

99. A.I.R. 1954 S.C. 44. see also Ganga Ram v. Firm [Ram Charan, A.I.R. 1952

s.c, 9.

100. A.I.R. 1949 B.P. 301.

101. Dhruv Dev v, Harmohinder Singh, supra, note 90 at 1026..

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

Law of Contract 189

Supreme Court on more than one occasion properly delineates the value

of comparative law, which can be made use of only when a case is not

covered by the existing law or when the law is to be reformed.

The Court refused to apply the contractual doctrine of frustration

to a transfer of property under a lease.

XV. Law of Refund

During the survey poriod numerous cases were reported where

the courts held that since the agreements were against public policy or in

contravention of statutory provisions, the refund of money could not be

allowed under section 65 of the Indian Contract Act, which reads:

When an agreement is discovered to be void, or when a

contract become void, any person who has received any

advantage under such agreement or contract, is bound to restore

it, or to make compensation for it, to the person from whom he

received it.

In the Supreme Court case of Sita Ram v, Radha Bai,102 the court

held that if a person is a party to an illegal or fraudulent agreement,

the court will not enforce the agreement at his instance. Nor shall the

court allow him recovery of money except in exceptional circumstances.

In this regard, the Court imported the various exceptions from Anson's

Principles of English Law of Contract and adopted them in the judgment.V"

One such exception, which permits recovery even in case of an illegal

agreement, applies to those cases where the illegal object or purpose has

not yet been carried out and there is a chance of withdrawal, i.e., locus

penitentiae. During the period under review the High Courts of

Allhabad, Andhra Pradesh, Calcutta and Patna applied this last mentioned

principle and denied the remedy of refund to the plaintiff where the

illegal purpose had been executed and the matter had passed beyond the

stage of mere contracts.w-

The law on the subject, though already well established, gets deeper

roots now. And the authoritative pronouncements of the Supreme

102. A.J.R. 1968 S.C. 534.

103. Id. at 537..38.

104. Seetharama Sastry v. N. Ka/war &. Sons, A.I.R. 1968 A.P. 315; R. Pallamsethi

v. D. Sriramulu AJ.R. 1968 A.P. 375 ; Gauri Shanker v. Chandari Girja Prasad. A.I.R.

1967 All. 262 ; Calcutta National Bank v, Rangaroon Tea Co., A.J.R. 1967 Cal. 294,

following lmmani Apparao v. Ramalingamurthi, A.I.R. 1962 S.C. 370; Kuju Collieries v.

Jhar Khan Mines, A.I.R. 1967 Pat. 72.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

190 Annual Survey of Indian Law 1967 and 1968

Court approving the exceptions stated in Anson's book on law of contract

makes the task of the lower courts easier to apply the set principles to the

situations which come before them from time to time.

XVI. Quasi-Contracts

During the survey period a few cases, not of great significance, were

reported in the erea of quasi-contracts. Sections 68 to 72 of the Indian

Cotract Act deal with the principle of unjust enrichment, The cases

discussed below deal with the application of this principle.

In a Madras case,105 a workman at Port Trust, Madras, presumably

lost the use of both of his legs due to the negligence of the cartman, the

cart being "heavily loaded with iron-mesh."106 The cart belonged to the

defendant company. There was a statutory liability on the Port Trust,

under the Workmen's Compensation Act to pay compensation to the

worker, which it did. It then filed a suit against the defendant for recovery

of the amount paid, inter alia, under section 69 of the Indian Contract

Act which reads:

A person who is interested in the payment of money which

another is bound by law to pay, and who therefore pays it, is

entitled to be reimbursed by the other.

Applying this section, the Madras High Court held that it could

not be said that the Port Trust which was under a statutory liability to

pay compensation was "'merely interested"107 in the payment. Furthermore,

although liablity of the defendant to answer for the negligence of his

cartman might exist in law, at the time of payment by the plaintiff (Port

Trust), he was not bound by the law to pay any ascertained amount.

Three other cases dealt with the application of section 72 of the

India Contract Act, where refund is allowed if money is paid by mistake

or under coercion.l'" In a Patna case 109 refund was refused because

it was paid on a void contract, conrary to the policy of the Act. In

a Supreme Court case,110 a bank credited money to the account of a

105. Port Trust, Madras v. Bombay Company, A.I.R. 1967 Mad. 318.

t 06. ld. at 321.

107. ld. at 326.

108. See infra, note 109, 110, 111.

109. Kuju Collieries v. Jhar Khan Mines, supra, note, 104, Here the payment of

premium was prohibited by statutory Jaw.

110. Jammu & Kashmir v. Attar-ul-Nisa AJ,R. 1967 S,C. 540.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

Law 01Contract 191

person at the instruction of the government. This resulted in double

payment by mistake. The amount deposited in the account of a third

preson, even if by mistake, cannot be withdrawn without the consent of

such third person. Section 72 was held not applicable, because it applies

"when we are dealing with a case of two persons one paying the money

and the other receiving the money on behalf of the person paying it. "111 In

the Calcutta case,112 the government discovered that it had paid the sales-tax:

by mistake. The basis of its claim for recovery was that the money had

been wrongly paid under the contract. The Calcutta High Court held that

neither section 70 nor section 72, which apply in the absence of contract,

governed the present situation. The Court further opined that if the

contract for payment of sales-tax was made on account of mistake of

law, it did not become voidable therefore.

In an Orissa case,113 where refund was sought against a minor, it was

held on the authority of a Patna case,114 that section 70 did not apply to

minors. The Court omitted to cite a Supreme Court case,115 where the

same view had been earlier expressed.

The above cases do not indicate any marked development on the

subject.

XVfi. Damages and Deposit Money

Sections 73 and 74 of Indian Contract Act deal with the principles

of damages. Dicta of the cases may be stated thus:

1. In case of breach of contract of service by the employer, the

proper remedy is a suit for compensation and not a writ.P"

2. The assessment of damages cannot be based on the economic

policy of the country from where the goods are to be imported.P?

3. An arbitrator should not ignore the principles of assessment

of damages laid down in section 73.118

111. Id. at 542.

112. Union of India v, Lal Chand & Sons, A.I.R. 1967 Cal. 310.

113. D. Gurumurty v. Raghu Podhan, A.I.R. 1967 Ori, 68. See Specific Relief Act Ss.

33 (2) (1963).

114. Bankey Behari Pd. v. Mahendra Pd., A.I.R. 1940 Pat. 324.

115. State of West Bengal v. M!S B.X. Mondal & Sons, A.I.R. 1962 S.C. 779, 789.

116. Boo/ Chand v, Kurukshetra University, A.I.R. 1968 S.C. 292.

117. Naihati Jute Mills v, Khyaliram, supra, note 90.

118. Bungo Steel Furniture v, Union of India, A.I.R. 1967 S.C. 378, see also the

minority judgment.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

192 Annual Survey 01 Indian Law 1967 and 1968

4. It has been held in a contract for the sale of land, that where

neither party to the contract is wholly at fault and neither

faultless, no damages can be awarded against the vendor.P"

5. Unless there is a contract to the contrary, damages for breach of

contract are not limited to the cash security deposit.v"

6. Where the consignee received the railway parcel after delay,

expenses incurred by it in sending its representative to Bombay and

on the return journey and on keeping the factory closed cannot be

recovered since these are too remote.P!

All these principles pronounce important points of law of damages;

principle in item 4 seems to have been applied to a relatively novel

situation.

A few cases relate to forfeiture of earnest money. In one case,122 it

was held that unless there is a forfeiture provision, either directly or

indirectly, the deposit cannot be forfeited. In some other cases, the

principle of forfeiture of earnest upon breach by the depositor was stated

to be well established.P" To the date of this writing, however, the law as to

earnest and security deposit has been revolutionized.P'

XVIII. Conclusion

The cases indicate a definite development in the formation of contract

without a voluntary offer and a voluntary acceptance, the compulsion of

law has not been regarded as coercion. The recognition by the Supreme

Court of the doctrines of equitable estoppel, as distinct from the

principle of estoppel in the Indian Evidence Act) and explosion of the

theory of past cohabitation in relation to consideration deserves special

mention. Quantitatively, numerous cases dealt with the question of

public policy and the law of refund.

119. Umor Noor v, Dayal Saran, A.T.R. 1967 All. 253.

120. Bishal Chand v. Chattur Sen, A.I.R. 1967 All. 506.

121. Union of India v. P. W. & G. Mills, A.I.R. 1967 Punj, & Har. 497.

122. R.B. Thakur and Co. v, Shreeram Durgaprasad, A.T.R. 1968 Born. 35.

123. Conservator of Forests v. Sridhara Reddy, A.I.R. 1968 A.P. 198; Halib Ali v.

Ra fikuddin, A.I.R. 1968 A & N. 26. Ram Lal v. Gokalnagar Sugar Mills, A.LR. 1967

Del. 91, 96.

124. r.c. Saxena, Deposite Forfeiture: A Comparative Legal Perspective 12 I.l.L I.

411 (1970).

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

You might also like

- Application For Visitor Visa (Temporary Resident Visa) : Protected When Completed - BDocument6 pagesApplication For Visitor Visa (Temporary Resident Visa) : Protected When Completed - BSergio Daniel Rodriguez100% (1)

- COMPROMISE AGREEMENT Vehicle AccidentDocument2 pagesCOMPROMISE AGREEMENT Vehicle AccidentYves100% (3)

- Simple Guide for Drafting of Civil Suits in IndiaFrom EverandSimple Guide for Drafting of Civil Suits in IndiaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- Sample DecisionDocument3 pagesSample DecisionGeraldine Salazar-LuceroNo ratings yet

- Suntay Vs SuntayDocument3 pagesSuntay Vs SuntayGR100% (1)

- 008 - 1996 - Contract LawDocument16 pages008 - 1996 - Contract LawAnjanaNo ratings yet

- 027 - Mercantile Law (865-900)Document35 pages027 - Mercantile Law (865-900)divya mathurNo ratings yet

- Contracts Promissory Estoppel Research PaperDocument8 pagesContracts Promissory Estoppel Research PaperPARMESHWARNo ratings yet

- Determining Governing Law and Jurisdiction in A Contract PDFDocument3 pagesDetermining Governing Law and Jurisdiction in A Contract PDFNaga NagendraNo ratings yet

- 06-Civil Proced. 2016 PDFDocument40 pages06-Civil Proced. 2016 PDFishikaNo ratings yet

- ADR - Case LawsDocument6 pagesADR - Case LawskeerthivhashanNo ratings yet

- MBA21062 - Sumanth G - LAB Assignment-01Document6 pagesMBA21062 - Sumanth G - LAB Assignment-01Sumanth GNo ratings yet

- Arbitration Law Case CommentaryDocument9 pagesArbitration Law Case CommentaryKoustav BhattacharyaNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court of India Page 1 of 20Document20 pagesSupreme Court of India Page 1 of 20Nisheeth PandeyNo ratings yet

- Arbitration Cases CA2Document11 pagesArbitration Cases CA2shreya pooniaNo ratings yet

- Object and Consideration - Contract Project.Document11 pagesObject and Consideration - Contract Project.AnimeshNo ratings yet

- Dahiben Umedbhai Patel and Others Vs Norman James Hamilton and Others On 8 December, 1982Document10 pagesDahiben Umedbhai Patel and Others Vs Norman James Hamilton and Others On 8 December, 1982Knowledge GuruNo ratings yet

- MemorialDocument12 pagesMemorialPtNo ratings yet

- Cca Assignment 2Document3 pagesCca Assignment 2Esha rajbhojNo ratings yet

- Lexis® India - DocumentDocument12 pagesLexis® India - DocumentSandhya VaradharajanNo ratings yet

- Privity of ContractDocument12 pagesPrivity of ContractR100% (1)

- Severability of ArbitrationDocument4 pagesSeverability of Arbitrationrameshg1960No ratings yet

- Execution of Agreement To Sell and PurchaseDocument58 pagesExecution of Agreement To Sell and PurchaseSarvjeet MoondNo ratings yet

- Intention To Wager: 1 Ibid. 2 Ibid. 3 IbidDocument5 pagesIntention To Wager: 1 Ibid. 2 Ibid. 3 Ibidparul priya nayakNo ratings yet

- List of 20 Notable Cases of Contract Law - IpleadersDocument16 pagesList of 20 Notable Cases of Contract Law - IpleadersDhriti DhingraNo ratings yet

- Ramachandran-Conflict of Laws As To ContractsDocument19 pagesRamachandran-Conflict of Laws As To ContractsSwati PandaNo ratings yet

- 1-Contours of Relief of Specific Performance of Contracts by ACB, Court, RjyDocument16 pages1-Contours of Relief of Specific Performance of Contracts by ACB, Court, RjyaryanNo ratings yet

- Loopholes in ACADocument16 pagesLoopholes in ACAKriti ParasharNo ratings yet

- IRAC Contracts Sec1-75Document12 pagesIRAC Contracts Sec1-75Mokshha SharmaNo ratings yet

- Adr Case AnalysisDocument19 pagesAdr Case AnalysisEswar Stark100% (1)

- ContractsDocument11 pagesContractskrish vikramNo ratings yet

- ARGUMENTSadvancedDocument7 pagesARGUMENTSadvancedjamesmail312No ratings yet

- Stamping Out Uncertainty - The Legal Fiasco of Unstamped Arbitration Agreements in IndiaDocument7 pagesStamping Out Uncertainty - The Legal Fiasco of Unstamped Arbitration Agreements in IndiaAmey KalamkarNo ratings yet

- Session 2 - Case NotesDocument10 pagesSession 2 - Case NotesYash MayekarNo ratings yet

- Certainty of Terms CONTRACTDocument5 pagesCertainty of Terms CONTRACTJannahAimi50% (2)

- CPC Case BriefDocument9 pagesCPC Case BriefPravir Malhotra100% (1)

- 2018 (2) Ac 0293Document4 pages2018 (2) Ac 0293rakesh sharmaNo ratings yet

- Contract ADocument4 pagesContract APararaeNo ratings yet

- DraftingDocument7 pagesDraftingMayank TripathiNo ratings yet

- Compromise of SuitDocument19 pagesCompromise of SuitAbhushkNo ratings yet

- Recent Cases On Arbitration Law in IndiaDocument9 pagesRecent Cases On Arbitration Law in IndiaRayadurgam Bharat Kashyap100% (1)

- ULE OF IschiefDocument19 pagesULE OF Ischiefrheakhandke2001No ratings yet

- Respondent Arbiration PDFDocument14 pagesRespondent Arbiration PDFsamyukthajinuNo ratings yet

- Contract Project .OokkDocument14 pagesContract Project .OokkPriyal AgarawalNo ratings yet

- Case Study (Mohan Krishna)Document19 pagesCase Study (Mohan Krishna)mohanNo ratings yet

- Arbitration Law India Critical AnalysisDocument23 pagesArbitration Law India Critical AnalysisKailash KhaliNo ratings yet

- 008 - 2002 - Contract LawDocument12 pages008 - 2002 - Contract LawManoj dhiranNo ratings yet

- Carlill V Carbolic Smoke Ball Did Attempt To Give An ExplanationDocument9 pagesCarlill V Carbolic Smoke Ball Did Attempt To Give An ExplanationNida KhatriNo ratings yet

- The Specific Relief ActDocument8 pagesThe Specific Relief ActAkash KumarNo ratings yet

- Contract IDocument5 pagesContract ISatyam OjhaNo ratings yet