Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Text of The Iliad (III)

The Text of The Iliad (III)

Uploaded by

Alvah GoldbookOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Text of The Iliad (III)

The Text of The Iliad (III)

Uploaded by

Alvah GoldbookCopyright:

Available Formats

The Text of the Iliad, III

Author(s): T. W. Allen

Source: The Classical Review, Vol. 14, No. 8 (Nov., 1900), pp. 384-388

Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of The Classical Association

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/694642 .

Accessed: 20/06/2014 21:32

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Cambridge University Press and The Classical Association are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve

and extend access to The Classical Review.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 194.29.185.145 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 21:32:29 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

384 THE CLASSICAL REVIEW.

versation, crops out in the change from the series of 'imperfect' infinitives in Thuc. I,

objective present infinitives, 4VX77TELv etc., 3, 2. The passage seems to admit us into

to a future infinitive, flo)O4EcLv: another the very workshop of Thucydides, while he

line or two, and the lively narrative would struggles for absolutely clear and logical

doubtless have taken the second step, and expression, with by no means adequate

become direct quotation: for a Greek is command of graceful style. oKE 8~ /LOL,

he

always tempted toward the more dramatic begins, emphasizing the conjectural nature

form. Then again cYvvGEJveoL repeats a-vvrL- of his whole statement. Then he passes to

OEvraLwith its widest subject, which how- the past tense: 0;i8 'rovoLa r70'r70 $prao4d

ever is instantly cleft with a o' p~hvetc. 70 eXEv. Yet, having thus made the time-

8~

ZEvo4&v comes in a line later, but the relation plain, he is again more anxious to

other generals are not alluded to again. regain the connection with the modest OKEZ,

There is no 'irregularity' here, unless it which now becomes personal and ceases to

be irregular for a man's coat to fit him be parenthetical. So we have an infinitive,

perfectly and be a misfit for his brother. &dXX rh pyv rp 70~E ro

~vaElwvov

Elo vKa vo KaL

Yet it would be impossible to codify these wnVVOV8E TVaL rj avfr/. We may

o ElKX?••OLV

variations, in the width of the subject, by say, that the subject of 8oKo has narrowed,

general rules of grammar. from the whole long sentence to i-'KX~OLV

The next sentence cited is a no less alone. Now, here again the lack of any past

familiar one from Thucydides I, 2, 1. tense to use makes the present, ivaL, less

Kaovbvy oi -Xach

balveras y&p , viv 'EAXX&S striking, like oVo-aL in the other passage.

/Epale oLKov/LCV?, XXaA/pLavaE'rao-'rLoEE Yet even so, besides EXEV,the temporal

ovoca ra

K

7rp&drEpaKaL ~ El "rv TaOoL av?r&v phrase zrph"EMyrvos guards it. It is true,

&TrokELToVrTEV.The brief note in the ex- that two real 'imperfect infinitives' fol-

cellent Classen-Morris-White edition re- low: and KakXeo-OaL. Yet any-

•rapE'XerOaL traces the

marks, that the three participles 'belong one who patiently long sentence

to the imperfect.' Now, of course, the through its windings will be struck, not

imperfect indicative tended to pass into merely with the careful timing references

present participle, if any. But every to the Pelasgians, Hellen, etc., but especially

such transition was liable to produce with the reversion, at the last, to the indica-

ambiguity, which is ' the unpardonable sin' tive, ~8v'varo. The use of an 'imperfect' in-

in style. Hence it is most carefully finitive, then, cannot be denied: but it is a

guarded. In this case, oiKov/Lcv represents delicate crossing line between tenses which

OTLOV 7raXaLoLKLraL, not KETro. To be sure, must not be confounded, and the stylistic

an English translation uses a perfect or past effort for perspicuity is therefore especially

indicative ('It appears that it was per- instructive.

manently settled not long ago,' or 'It The present purpose is, however, to illus-

appears that it has not been settled long'), trate not a particular construction, but the

but this is itself a grave ambiguity found in infinite variableness of all so-called types.

English only. Action continuing from the Nothing can be understood or enjoyed

past into the present is expressed by the aright, when torn out of its proper place.

present, with the proper temporal adverb, in This is true of shell-fish or algae, but cer-

most languages. r• -rpd~rpamakes the real tainly no less true of the delicate perishable

time of oto-aLclear, and yet the apparent organisms we call sentences. They yield

parallelism with may have disguised themselves up wholly only to him who sees

the transition to•rdXaL

the imperfect. Finally, the life in language, ay, the life behind

the close link rE...KaL makes us realise language, steadily, and sees it whole.

without effort that is in the Linguistics is biology, not anatomy.

same time as ovo-aL.KaakOXEtovrE Wi. C. LAWTON.

There is a similarly brief note on the

THE TEXT OF THE ILIAD, III.

I HAVEshown (C.R. March 1899) that a body the members of which diverge from

the existing MSS. of the Iliad, with the each other in different degrees, but in

exception of several fragments of the degree only and not in kind. An apparent

Ptolemaic era, constitute a vulgate, that is, exception to this uniformity, the family h,

This content downloaded from 194.29.185.145 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 21:32:29 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE CLASSICAL REVIEW. 385

was shown (July 1900) to be a special case vulgate, a possible actual descendant of

of the general tradition. Aristarchus or even of a time earlier than

Upon analysis of the readings of the he. I have tried to show (C.R. July 1900)

MSS. (October 1899) it appeared that in that the higher percentage of Aristarchean-

60 cases the modern vulgate was identical ism in this family is due to natural and

with the text to which the ancients gave automatic causes. I venture to propose the

the same name-so far as it can be re- same process as the explanation of the non-

covered; in 16 the reading of the ancient vulgate elemer;t in our Homeric text

vulgate had been displaced by that of Aris- generally. I advance that from late

tarchus, and in the remaining 24 the MSS. classical times at least the lections of the

varied between one and the other. This commentators were written upon the margin

did not imply that the only ancient readings of many of the ordinary copies, and that the

to be found in our text are those of Aris- substitution of these marginal readings for

tarchus, but that considering the predomin- those of the text, in varying proportions,

ant position of Aristarchus as regards his during centuries of transcription, produced

predecessors, and the small number even of the mediaeval text.

his readings that have found their way The evidence for this hypothesis is rather

into even a (•T)

single MS., it seemed probable circumstantial than direct.

that the readings of other ancient critics

where they exist otherwise than sporadi- It may be taken as a general rule that

cally in the vulgate, owe their survival to all, or nearly all, minuscule MSS. of the

their having adopted or coincided with the Iliad are corrected, not clerically, but in

ancient Kowvq. This was most demonstrably substantial particulars. They are corrected

the case with Zenodotus. in different degrees, some occasionally,

There being then in the modern manu- others systematically, and in exactly the

script text 40 per cent. of non-vulgate lines on which known variants occur.

readings, of which 16 per cent. have ex- There being no apparent source for these

pelled their contraries, we have to seek an corrections, it is to be supposed they

explanation of their presence in these pro- proceed from comparison with other manu-

portions. The explanation will at the same scripts (as we are occasionally explicitly

time supply a theory of the genesis of the informed).

actual Homeric text. Marginalia are a more fruitful source of

The old view which started with Wolf textual alteration. We find long scholia,

and may still be met with, that our text is short scholia or-another form of these-lists

that which the Alexandrians formed out of of variants introduced by yp. All of these in-

the vulgate by the exercise of their criticism, fluence a scribe as he copies his archetype,

needs no refutation: the opposite position and induce him to transfer some of them to

that the Alexandrians exercised no influence his text, or to append them as corrections to

on the Homeric text, is in fact correct; it. The effect of scholia, long and short,on the

their influence directly was nil, they did text which they accompany, may be studied

not supplant the ordinary editions with the in the Venetus A; a certain number of

copyists. Yet the Alexandrian readings interlinear corrections can hardly be denied

stand in the ordinary modern text, in cer- to proceed from the marginal or intermar-

tain proportions. ginal scholia (and my remark Journal of

That this partial admixture of Aristar- Philology, xxvii. p. 171, that the scribe did

chean readings is the result of a recension, not pay attention to the scholia, needs

the deliberate choice of a learned man- modification) Compressed scholia with yp.

an idea which may perhaps commend itself are to be found also in T, and in the

to some enquirers-again almost disproves 'scholia minora.' Lists of mere variants

itself: the table which I have given C.R. with yp. are less common, but still are often

1899 p. 432 shows an irregularity in the found: a remarkably consistent example is

survival of Aristarchus' readings far beyond in Ven. 458, a MS. of the h family, which

the possibilities of a recension. This ir- has the non-h readings collected on the

regularity, and the fact that no sort of margin throughout; other noticeable MSS.

merit distinguishes the survivals from the are 'Ang.', Vat. 5, and many more occa-

neglected readings, seem inconsistent with sionally.

any process which involves the idea of In the Ven. A we can watch the process

intention or choice. of the casual attraction of variants into the

As I have said, one family (h) seemed a text; in the others it cannot be doubted

possible exception to the general modern that if they were used as archetypes a

cc2

This content downloaded from 194.29.185.145 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 21:32:29 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

386 THE CLASSICAL REVIEW.

certain proportion of their variants must I will ingenuously confess that I do not

have won a place in the resulting text. In see any valid objection that can be made to

the rare instances where one MS. can be this theory. I can imagine however that it

proved to have been copied from another might be observed that while such a theory ac-

this is the case (e.g. Vat. 27 from Vat. 4.) counts for sporadic or occasional cases ofAris-

The adscription and attraction of variants tarcheanisms in the text, it is hardly able

is a constant feature in minuscule MSS. to explain the presence of the 16 per cent. in

In uncials and papyri also we find correction all MSS., or in other words of the 67 Aris-

and adscription frequent, and as far back as tarchean readings which have found their

the third century B.c. The Ptolemaic frag- way into all MSS. To this I answer (1)

ments have readings superscribed at 1 397, that in this case too, for the reasons given

398 X 152; the Bankes MS. of s. II. A.D. above, no other hypothesis seems admissible.

has corrections and marginal variants, the No recension could have selected exactly

Ambrosian of s. IV.-V. has among many these 67 cases to the exclusion of the other

clerical one or two real corrections; the 664, and it is equally improbable that these

Bodleian papyrus (s. V.) has several mar- 67 readings come from any particular edition

ginalia and a few corrections. which had a special influence upon the

The critical signs also, which occur vulgate. (2) The case of a reading, not

systematically in Ven. A, and system- original, entering and pervading an entire

atically or sporadically and at wide inter- text, is far from an uncommon phenomenon.

vals of time in several uncial and minuscule Upon it rest in fact most modern conjectures;

MSS. (Brit. Mus. pap. 128 s. I. B.c., Bodl. it is assumed without question by the enter-

MS. gr. class. a. 1 (P) s. V. A.D., 'C' prising critic that the graphical corruption,

(s. XI.),' D' (s. XI.), 'T,' Ven. cl. ix. cod. the interpolation, the gloss, which his con-

3 and others) are examples of the tendency jecture is to displace, has entered acbextra

to annotate, according to the material which and conquered the entire tradition. How-

was at hand, the margin. ever unfounded in the case of most con-

We see then the tendency constant, from jectures this assumption may be, it can

our earliest MSS. onward, to annotate the hardly be validly objected to my theory that

margin of a MS. with readings of the a quasi-graphical and mechanical process

opposite sense to those of the text; and we has imposed Aristarchus' readings to the

can sometimes trace, and must often assume, extent of 16 per cent. upon the whole text.

the supplanting of the text by them. A more important consideration is, what

To turn to more general considerations, consequences follow from the adoption of

to account for such a casual and arbitrary this hypothesis I what view of the history of

collection of variants as the Aristarcheanisms the Homeric text does it involve?

of our text, a process is required which con- The hypothesis which I have stated, that

tains the element of chance. Now the the divergences from the ancient vulgate in

operation of copying is admittedly one of our text are due to the gradual and casual

these: the business of a scribe is con- incorporation of variants registered on the

ditioned by semi-conscious and mainly margins of manuscripts, evidently implies

physical circumstances. Graphical similari- that the KOLV)EKOOL~had come to be the one

ties act only at random, the gloss supersedes direct source of tradition, and that the MSS.

the original incalculably, homoeoteleuton, other than the KonLVawere only known, and

homoearchon, and the other principles of only exercised an effect upon the Homeric

criticism now work and now do not. Their text, indirectly and through commentaries

casual operation is no hindrance to any of and scholia. This no doubt is a considerable

them. The incorporation of marginalia assumption, and also the less interesting or

into a text, the correction of a text by com- attractive account. Our modern text loses

parison with other copies of the author, are in interest if it is cut off from all direct

eminently phenomena of this sort. The affiliation to the Alexandrian and prae-

theory therefore suits the fact that in book Alexandrian editions.

A out of 34 Aristarcheanisms the MISS. It is however a conclusion pointed to by

have 2, in B 2 out of 28, in 1 2 out of 25, the whole of the independent evidence. This

in Z 4 out of 19, and so on. evidence consists of the only contemporary

authorities, the papyri and the quotations.

If the hypothesis appears to account for The only papyri which depart in such

the facts in general, we have next to ask if a marked degree from the average as to

thereisany circumstance which contradicts it, deserve exclusion from the KOLV?are the

and what consequences its adoption implies. third century Ptolemaic fragments, published

This content downloaded from 194.29.185.145 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 21:32:29 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE CLASSICAL REVIEW. 387

by MM. Mahaffy, Nicole, Grenfell and Hunt. while he preserves to us many stories

Their number may we hope be increased, but about the text, uses in his quotations MSS.

the vulgate papyri of the first century B.C. mostly of the vulgate type; his variations

and later are already so numerous that we are usually of single words or at most half

should be justified in treating such additions lines. The same remark is true of Diogenes

as exceptions and survivals. Laertius. After him, or more correctly,

The quotations tell the same tale. It may after Plutarch, there is no sign of extensive

be seen from Professor Ludwich's collections variation in the quotations. Plutarch, an

(Ueber Homercitacteaus der Zeit von Aristarch antiquarian, who lived in a country district

bis Didymos, 1897) and from comparison of of continental Greece, will have possessed a

authors not included in that work or in his copy of some ancient edition, but even in

Die Homervulgata als voralexandrinische his day it was an exception; and neither

erwiesen, 1898, p. 71 sq. that the post-Aris- MS. nor quotation suggest such a survival

totelian citations down to Diodorus yield after his time. Ammian and Julian are

very few variations from the vulgate.1 If quite vulgate, and so is Macrobius-a

we were to bow entirely to their evidence valuable witness on account of the range of

we should say that the KOLV) swept the field his quotations. The KOLYv will have gradually

in the second and first centuries B.C. The choked off the sporadic editions, and by the

quotations of the first and second centuries epoch when the first Homeric scholia were

A.D.however show a certain reaction. Strabo collected, it may be doubted if any of them

exhibits a considerable number of omissions survived in the book-market.

and additions, severe grammarian though he My hypothesis therefore, derived from the

is: Apollonius the lexicographer, when analysis of the readings of the mediaeval

every allowance is made for his system of text, agrees with the conclusion of the direct

quotation and the corruption of his text, history of tradition, so far as it is known to

has certain undoubted variants. Dio of us. The book-trade, which had never been

Prusa and Pausanias though they use largely affected by either the special editions

vulgate texts have each occasional valuable nor the criticism of the Alexandrians, con-

information. Plutarch has numerous and tinued in its course of propagating the KOLc ;

important variations (B 413, E 518 a b, I the influence of the other editions was only

458-461, A 451 and 453, S 206, 207, 208) conveyed through the casual aberration of

besides the striking passage 'I 223 sq. the copyist's eye, roving between his text and

confirmed by Bodl. ms. gr. class. b. 3 (P) what he presumed were corrections of it upon

(Greek Papyri, series ii. 1897). Athenaeus, the margin. Genealogical relation therefore

1 Among the prae-Alexandrianwrite:s who contri- between the mediaeval text and the Alexan-

bute variants to the text we have to reckon, beside drian and prae-Alexandrian editions there

Plato, Aristotle,Aeschines,and Lycurgus,not only is none; the actual survivals of the readings

Dioscuridesthe disciple of Isocrates(adds I 119a), of these editions do not suggest any thread

but Chrysippusthe Stoic. Chrysippus,whosename of real connection. The one

occurs frequently in the Homeric scholia (see Bekker's permanent and

index), is quoted by Galen, de plac. Hipp. et Plat. organic element in the text of Homer is the

(ed. I. Miiller, 1874) iii. 114 sq. Galen says (114 KoLv4; the rest is accidental and casual

end, 115) rJirwvaphv yhp rai'ra 7h er?fal rpbs rol'rotsOs accretion.

7

rt%

/IvpCa

E2

rXb

)iop

d'v

XplmtLr7ros 7rapacrtO6e-ra... The value of the collation of Homeric

I.r.pa Tb

•),b

(7rewp 7•v'trCLa 7rapaypcdcotLxL, 7rX~ipo'

iat 6 XplarLrros 3BXorov

Galen's variants MSS. is necessarily affected by this con-

thereforemay be supposed d'r4ripo•wo•.

to representChrysippus' clusion. The Homeric apparatus does not,

text. We findseveralversesnot in ourHomer: as that of most authors, testify to the

? 115 7rpieVr, vvlo'•S~eoEQLv ALb~saXYdv survival of good elements of an original

eptL78VEIOS text: it indicates where and how acci-

ib. Yvw'LxvtL.

o'TE8j7 O'rfl74W V ' &L&aeppevas 'AhEXro ZEbS

(sic). dental adscription has diversified a common

? 134 &hXo8' e'4 vr•eo?ir ~dos /Lr?fs a&~iwv. stock; its value is mainly historical, aid

And these variants: oal consists in the light it throws upon the

115 = 322 d$Bov v'

nature of the clerical transmission of a

'ivifoa"' haaos =

5 ?so0prsosOhXs MSS. -XdOov'o familiar and much-commented author.

iv. ? 153 e'r 'AXLaX s AXy~er6 T. W. ALLEN.

Karc7rep 'aic'a

reJvOov•vros rbV IldT'rpoiKxov

&AA' ire

Frotfl'rls

7r IKALYvad~peYds

re Kop6'QOn

(= 8 541, i• 499). KG•,awVy

POSTSCRIPT.

Immediately after this Galen quotes ?z514, so that

Chrysippus apparently read this verse instead of

?1 513

abrhp drtL ~a ydoto erdpor'ro Gios 'AxtLAXEs.

Professor Arthur Ludwich has honoured

At X 212 the scholia tell us he read 4i3pa

for ad4aa. the first of these articles (March 1899) with

This content downloaded from 194.29.185.145 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 21:32:29 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

388 THE CLASSICAL REVIEW.

some remarks in the very important list of to find them left out in MSS. of no relation-

manuscripts of the Iliad which he has pub- ship, and so they are left out in my L 8,

lished in the Flestschrift fiir C. F. W. L 11, L 12, Ang. Vat. 19, Vat. 25, and

Mliiller (Supplermentbandd. Jahrb. f. klass. other MSS.

Phil. xxvii. p. 31 sq.). It is of course im- The omission of the Catalogue is a very

possible, except in the prolegomena to an striking phenomenon: I know of eleven

edition, to present the details and calcula- MSS. in which it occurs, besides the one

tions upon which a classification of MSS. family o, and most of them have no point

rests, and I agree with the general consider- in common beyond it. The case is not so

ations by which Ludwich (p. 44, 45) is kind simple as the last, for that the Catalogue

enough to explain some differences in our should have been omitted at all is quite

results. The method of distinguishing mysterious, as Ludwich himself has observed

MSS. must be quantitative: where the (Die Homervulgatc, p. 32); but whatever

total of agreements exceeds the total of cause started the omission, it is certainly

differences there is relationship, and I have sporadic in most of the cases where it

generally found agreement in one or two occurs.

striking variants delusive. As I have stated, several of my minor

Ludwich mentions two cases of agree- families have not much stability, and on re-

ment which I have passed over: first, the treatment might be fused into other groups:

omission of B 166-181 in my M 1 and M 9. one I should have added, the combination

These lines were omitted for a graphical G (Vindobonensis 39) Mori (Trinity College,

reason, the identity of 164, 165 and 180, Cambridge) 02 (Barocci 203), which may be

181 and therefore we might have expected called q.

ON THE WORD Ap&Ma.

Two or three years ago something called KE~VYaVpLKV (LaOt KaL oaTvptVLKOVTLVa 6t'wov.

Opr 4. 19

my attention to the use of the word In Xen. Symp. rdrovov eLXyvivr rTOiv

According to Liddell and Scott it is8p&/a.

used ToiL CVELIVand regularly

in o-arVpLKOiv

records of aTXLrTO~

dramatic contests we may

'especially of tragedy,' but I began to

doubt whether in good Attic it was ever presume that stands for CLTVpLKOV

o-aTvpLK•V

used of comedy at all, and my doubts have Cf. Athen. 428 A o4ooKX~7 Iv

only grown stronger, the more I have 8p&txa. oarvpLK (unless, as is likely, a masculine

investigated the matter. Let us clear two name has been lost before o-arvp~Kj, for in

things out of the way at starting. lists of plays etc. o-arvptKO is often made to

The word is sometimes used with no agree with the name, e.g. "Ip8Ls

dramatic or theatrical sense at all. Thus Athen. 451 c, arg.oLarVptK

Aesch.

Schol. ~4•LyyL

Ar. oTa'ptKV

1124

Nesch. Ag. 533 8pGpcaT70o7rdTov Sept.): Frogs Xmpts

and probablyEV;XErc•L

twice "O in the Theaetetus, oarvpLKov. When we recall the close rov

n-'~ov,

as the commentators take it: 150 A 1b TyO connexion of satyric drama and tragedy,

faLOv ro0roTov, EXar'rov 8O roIJaT

8pdC

there is nothing surprising in 8pgLa.

and 169 B 01 &k KaT''Avraiov 70o~ETLO

7T jLOLI/adoXXOV 0- continuing to be used of the former (which

KELs TO pavy. So in the Rhet. ad Alex. was indeed the old form of tragedy), even if

8pata

1438 b 15 E7av JXrLv (= 7rpdcEtL could not be used of comedy.

it

following) rpT Av X•lya8pcita'ra Much later A1- This last is the point which we have now

ciphron seems &Lo/yozvE.

to use it twice in this way: to examine by a scrutiny of the places in

3. 52. 1 i/LEyap KOLVWV?)TcL 7T7 aTowOU good Attic Greek, so far as they are known

&bsvvarov, oV' El IOL(K T7 -pIc4EWs to me, where the word occurs.

dLavrevtLa Aooo- In Aristophanes the word occurs twelve

vatal 8pvb dE1TrpiroE

O 8pTO Epa:3. 62. 2 8'

oL&aO•8phCa Kat b7; times. Ten of these passages refer

o'oV oVKEiSIarKpLvKaTEOp)

T4 8EcTIO7. distinctly to tragedy (Frogs 920, 923, 1021

Secondly in its dramatic sense there is no to Aeschylus: Ach. 415, 470, Frogs 947,

doubt that it was used of satyric plays. Thesm. 849 to Euripides: Peace 795, Thesm.

See Plato Symp. 222 D T ocarvpLKodvo0V 52, 166 to Carcinus, Agathon, and

8pa•la 70o70: Polit. 303 C 'V

o70V70 arXYV~ws Phrynichus respectively) and the other two

fltv )OrrEp8pa•la, KaOaTEp Eppy v) 8V v 1 (fhesm. 149, 151) may reasonably be

This content downloaded from 194.29.185.145 on Fri, 20 Jun 2014 21:32:29 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5822)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Oral Exam RubricDocument1 pageOral Exam RubricRodrigo Remón85% (13)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Dejeuner Du Matin AnalysisDocument2 pagesDejeuner Du Matin AnalysisMegan Thom0% (1)

- Unit 8 Short Test 2A: GrammarDocument2 pagesUnit 8 Short Test 2A: GrammarJeronimo Gangoso Vega0% (1)

- Did Aristarchus of Samothrace Influence Homeric VulgateDocument11 pagesDid Aristarchus of Samothrace Influence Homeric VulgateAlvah GoldbookNo ratings yet

- A New Papyrus Commentary On The IliadDocument6 pagesA New Papyrus Commentary On The IliadAlvah GoldbookNo ratings yet

- Reciprocities in HomerDocument40 pagesReciprocities in HomerAlvah GoldbookNo ratings yet

- Scholia Graeca in Homeri Iliadem (Rec.)Document4 pagesScholia Graeca in Homeri Iliadem (Rec.)Alvah GoldbookNo ratings yet

- Dividing HomerDocument12 pagesDividing HomerAlvah GoldbookNo ratings yet

- On The Homeric Caesura and The Close of The VerseDocument40 pagesOn The Homeric Caesura and The Close of The VerseAlvah GoldbookNo ratings yet

- Zeus in The Iliad and in The Odyssey. A Chorizontic ArgumentDocument3 pagesZeus in The Iliad and in The Odyssey. A Chorizontic ArgumentAlvah GoldbookNo ratings yet

- Divine Epiphanies in HomerDocument28 pagesDivine Epiphanies in HomerAlvah GoldbookNo ratings yet

- To Geloion in The IliadDocument12 pagesTo Geloion in The IliadAlvah GoldbookNo ratings yet

- Timeline of Homer's Iliad PDFDocument1 pageTimeline of Homer's Iliad PDFAlvah GoldbookNo ratings yet

- The Concept of Plot and The Plot of The IliadDocument9 pagesThe Concept of Plot and The Plot of The IliadAlvah GoldbookNo ratings yet

- Vertex Anim Toolset V3:: Quick Start GuideDocument12 pagesVertex Anim Toolset V3:: Quick Start GuideDee .OdztaNo ratings yet

- Project For Bca StudentDocument128 pagesProject For Bca StudentPriya SinghNo ratings yet

- Churuch GoingDocument5 pagesChuruch GoingGum NaamNo ratings yet

- Checking For Paragraph Links /thematic RelationshipDocument3 pagesChecking For Paragraph Links /thematic Relationshipsoola dondour50% (2)

- Reflection About Physical SelfDocument1 pageReflection About Physical SelfJohnrey TapereNo ratings yet

- Report Final CrusoetmDocument21 pagesReport Final CrusoetmAvinash Singh ChauhanNo ratings yet

- b2 s1 SpeakingDocument4 pagesb2 s1 SpeakinglilalilakNo ratings yet

- Determining The Missing Terms in A Sequence of Number - 012002Document3 pagesDetermining The Missing Terms in A Sequence of Number - 012002narrajennifer9No ratings yet

- Sanskrit Refresher LV7Document12 pagesSanskrit Refresher LV7Arun T YltpNo ratings yet

- Demo LessonDocument3 pagesDemo Lessonebanat2626No ratings yet

- Wasted and Severely Wasted: Root Cause Analysis OverviewDocument10 pagesWasted and Severely Wasted: Root Cause Analysis OverviewRoselyn Toriano MakilingNo ratings yet

- GV55 @track Air Interface Firmware Update V1.01Document12 pagesGV55 @track Air Interface Firmware Update V1.01Charly KureñoNo ratings yet

- CM Living Books and Sample ScheduleDocument6 pagesCM Living Books and Sample Scheduleapi-180100364100% (6)

- Libro Oficial Proxmox InglesDocument536 pagesLibro Oficial Proxmox InglesRatzar PerezNo ratings yet

- 10 Appreciation of The Poems - 5 MarksDocument4 pages10 Appreciation of The Poems - 5 Marksgrtgamerz365100% (1)

- Java ExceptionDocument19 pagesJava ExceptionMihaiDurneaNo ratings yet

- Prabodhani: - Shri HariDocument29 pagesPrabodhani: - Shri HariMitul LangadiyaNo ratings yet

- Seniority List Male Lecturers, BPS-18 Male (2018)Document82 pagesSeniority List Male Lecturers, BPS-18 Male (2018)Ammar Ahmed KhanNo ratings yet

- Integrated Review NarrativeDocument55 pagesIntegrated Review NarrativeJescille MintacNo ratings yet

- Eyd CVDocument3 pagesEyd CVEydhome100% (1)

- TC7 - CH4Document110 pagesTC7 - CH4JM MarianoNo ratings yet

- OpenERP Server Developers DocumentationDocument141 pagesOpenERP Server Developers DocumentationPablo Novoa PerezNo ratings yet

- Incremental Load in QlikviewDocument4 pagesIncremental Load in QlikviewNag DhallNo ratings yet

- LM10 Motor Protection System Instruction Manual: MultilinDocument106 pagesLM10 Motor Protection System Instruction Manual: MultilinHectorEspinozaZuigaNo ratings yet

- What Makes A Good Friend (Zadatak Za Sastav, 2. Razred)Document1 pageWhat Makes A Good Friend (Zadatak Za Sastav, 2. Razred)Anja RotimNo ratings yet

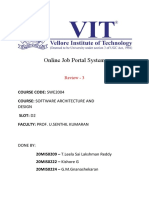

- Online Job Portal SystemDocument5 pagesOnline Job Portal SystemLeela saiNo ratings yet

- French CultureDocument10 pagesFrench CultureSHEONA SHAHNo ratings yet