Professional Documents

Culture Documents

This Content Downloaded From 157.45.249.27 On Fri, 29 Oct 2021 04:01:39 UTC

This Content Downloaded From 157.45.249.27 On Fri, 29 Oct 2021 04:01:39 UTC

Uploaded by

HistorianCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Sandy Hook ReportDocument284 pagesSandy Hook ReportLeakSourceInfoNo ratings yet

- Speech and Hearing Science in Ancient India-A Review of Sanskrit LiteratureDocument47 pagesSpeech and Hearing Science in Ancient India-A Review of Sanskrit LiteratureNeem Plant100% (1)

- Trends and Issues in Nursing EducationDocument23 pagesTrends and Issues in Nursing EducationShivani Tiwari50% (2)

- DPR of School of Nursing Under GimsDocument41 pagesDPR of School of Nursing Under GimsSubha PradhanNo ratings yet

- Trends in Development of Nursing Education in IndiaDocument13 pagesTrends in Development of Nursing Education in IndiaDhAiRyA ArOrA90% (10)

- Medical Encounters in British IndiaDocument82 pagesMedical Encounters in British Indiadarkknight2809100% (1)

- Sympathy and Science: Women Physicians in American MedicineFrom EverandSympathy and Science: Women Physicians in American MedicineRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- History of NursingDocument7 pagesHistory of NursingMahenurNo ratings yet

- Assignment 1Document161 pagesAssignment 1Rashmi C S0% (1)

- Kayla Flaskerud Vsim BP Concept Map, Isbar, ClincialDocument12 pagesKayla Flaskerud Vsim BP Concept Map, Isbar, ClincialCameron Janzen100% (1)

- 3 Week Diet PDFDocument52 pages3 Week Diet PDFMaja Zivanovic100% (1)

- Rural Marketing: Assignment ofDocument8 pagesRural Marketing: Assignment ofNeha GoyalNo ratings yet

- Alavi Islam Healing MasDocument46 pagesAlavi Islam Healing MasCheriCheNo ratings yet

- College of Nursing East Coast Institute of Medical Sciences, PondicherryDocument16 pagesCollege of Nursing East Coast Institute of Medical Sciences, PondicherryRuby Sri100% (1)

- (Neha Ellis) TRENDS and ISSUES in Nursing EducationDocument18 pages(Neha Ellis) TRENDS and ISSUES in Nursing EducationSunanda SharmaNo ratings yet

- Indigenous and Western Medicine in Colonial India (Z-Lib - Io)Document192 pagesIndigenous and Western Medicine in Colonial India (Z-Lib - Io)sarah shaikhNo ratings yet

- Trends & Issues NeDocument16 pagesTrends & Issues NeDhAiRyA ArOrA0% (1)

- Trends in Development of Nursing Education in IndiaDocument22 pagesTrends in Development of Nursing Education in IndiaShyam82% (11)

- Burton CleetusDocument27 pagesBurton CleetusMalavikaNo ratings yet

- Trends in Development of Nursing Education in IndiaDocument22 pagesTrends in Development of Nursing Education in IndiaAthira PS100% (1)

- History Project Sem2Document15 pagesHistory Project Sem2karthik1993No ratings yet

- Historical Developmentof Health Carein IndiaDocument8 pagesHistorical Developmentof Health Carein IndiaChar LeeNo ratings yet

- 20LLB067 History I EssayDocument21 pages20LLB067 History I EssayMahathi BokkasamNo ratings yet

- Trend in Development of Nursing EducationDocument21 pagesTrend in Development of Nursing EducationArchana Sahu0% (1)

- ETHICAL LEGAL PRINCIPLES IN CHNDocument32 pagesETHICAL LEGAL PRINCIPLES IN CHNJEEJANo ratings yet

- Deepak Kumar-Indian Medicin AurvedaDocument19 pagesDeepak Kumar-Indian Medicin Aurvedavivek555555No ratings yet

- A Bird's Eye View On Indian Healthcare SectorDocument9 pagesA Bird's Eye View On Indian Healthcare SectorInternational Journal of Application or Innovation in Engineering & ManagementNo ratings yet

- Struggle For Muslim Women's Rights in 1857-1947Document35 pagesStruggle For Muslim Women's Rights in 1857-1947Salman SafdarNo ratings yet

- Damodaram Sanjivayya National Law University Visakhapatnam, Andhra PradeshDocument22 pagesDamodaram Sanjivayya National Law University Visakhapatnam, Andhra PradeshSiddi SrikarNo ratings yet

- The Malabar ExperienceDocument46 pagesThe Malabar ExperienceBalakrishna GopinathNo ratings yet

- Subrata Pahari - Kaviraj - Daktar ConflictDocument12 pagesSubrata Pahari - Kaviraj - Daktar Conflict\No ratings yet

- Christianity and Nursing in India: A Remarkable ImpactDocument8 pagesChristianity and Nursing in India: A Remarkable ImpactRonald JosephNo ratings yet

- Trends in Development of Nursing Education in Indi1Document21 pagesTrends in Development of Nursing Education in Indi1anjanaNo ratings yet

- Unit I RevisedDocument18 pagesUnit I RevisedprathibaNo ratings yet

- Women Empowerment or Feminism Facts and Myths Abou PDFDocument3 pagesWomen Empowerment or Feminism Facts and Myths Abou PDFApoorv TripathiNo ratings yet

- 10 - Chapter 1 PDFDocument34 pages10 - Chapter 1 PDFRajeshNo ratings yet

- Project - PDocument88 pagesProject - PabbyNo ratings yet

- Ayurveda in The Time of CovidDocument23 pagesAyurveda in The Time of Covidmeera54No ratings yet

- Terminologies: 1. THEORETICAL FOUNDATION OF NURSING - The Central Concept of Health, Person, EnvironmentDocument12 pagesTerminologies: 1. THEORETICAL FOUNDATION OF NURSING - The Central Concept of Health, Person, EnvironmentSofia Yuki SakataNo ratings yet

- SKH April 2015Document147 pagesSKH April 2015Ramesha-NiratankaNo ratings yet

- Medical Ethics in India: February 2018Document20 pagesMedical Ethics in India: February 2018Sravs PanduNo ratings yet

- Essay 1Document5 pagesEssay 1Dalal RidayNo ratings yet

- Nursing India: and inDocument7 pagesNursing India: and inRonald JosephNo ratings yet

- Urdhva Mula - Roots Upwards: An Interdisciplinary Peer Reviewed Women's Studies Journal, Vol. 10, 2017 PDFDocument156 pagesUrdhva Mula - Roots Upwards: An Interdisciplinary Peer Reviewed Women's Studies Journal, Vol. 10, 2017 PDFProf. Vibhuti PatelNo ratings yet

- 14 Chapter 5Document51 pages14 Chapter 5Narasimha Swamy VodapallyNo ratings yet

- Seminar 2 - Historical Development in Medical Surgical Nursing in IndiaDocument90 pagesSeminar 2 - Historical Development in Medical Surgical Nursing in Indiasaranya amuNo ratings yet

- LeslieDocument3 pagesLesliepriyadarshineepratikshya5No ratings yet

- Evolution of Health ServicesDocument8 pagesEvolution of Health ServicesUma ZoomaNo ratings yet

- The Historical Roots of The Feminist Consciousness in The 19th Century Social Reform MovementDocument8 pagesThe Historical Roots of The Feminist Consciousness in The 19th Century Social Reform MovementArchana shuklaNo ratings yet

- AyurvedaDocument108 pagesAyurvedaManoj SankaranarayanaNo ratings yet

- Review A Tte WellDocument4 pagesReview A Tte WellSyed Mohammed AmmarNo ratings yet

- Textbook Ebook Looking Through The Speculum Examining The Womens Health Movement Judith A Houck All Chapter PDFDocument43 pagesTextbook Ebook Looking Through The Speculum Examining The Womens Health Movement Judith A Houck All Chapter PDFpeggy.wilson373100% (8)

- History of Nursing and Their Role in Modern HealthcareDocument8 pagesHistory of Nursing and Their Role in Modern Healthcaresadithyan726No ratings yet

- History of Developmrnt of Nursing ProfessionDocument10 pagesHistory of Developmrnt of Nursing ProfessionHanison MelwynNo ratings yet

- In the Bonesetter's Waiting Room: Travels Through Indian MedicineFrom EverandIn the Bonesetter's Waiting Room: Travels Through Indian MedicineRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- Introduction To Nursing FON-IDocument46 pagesIntroduction To Nursing FON-Imuhammadsalman0317090No ratings yet

- Sexual Rights and Gender Roles in A Religious Context PDFDocument5 pagesSexual Rights and Gender Roles in A Religious Context PDFLorena RodríguezNo ratings yet

- Women and LawDocument18 pagesWomen and LawShubhankar JohariNo ratings yet

- 6 - Brigitte SA Bastia 14 05 2011 PDFDocument30 pages6 - Brigitte SA Bastia 14 05 2011 PDFaatreyaprathibanNo ratings yet

- 6 - Brigitte SA Bastia 14 05 2011 PDFDocument30 pages6 - Brigitte SA Bastia 14 05 2011 PDFaatreyaprathibanNo ratings yet

- Competing For Medical Space: To Cite This VersionDocument30 pagesCompeting For Medical Space: To Cite This VersionaatreyaprathibanNo ratings yet

- Details of The Objectives AchievedDocument2 pagesDetails of The Objectives AchievedabbyNo ratings yet

- Tribal MedicineDocument61 pagesTribal MedicineKuntal ChaudhuryNo ratings yet

- Caring and Curing: Historical Perspectives on Women and Healing in CanadaFrom EverandCaring and Curing: Historical Perspectives on Women and Healing in CanadaDianne DoddNo ratings yet

- 31 07 2021 Planned OutagesDocument5 pages31 07 2021 Planned OutagesHistorianNo ratings yet

- Rolling MM3041Document17 pagesRolling MM3041HistorianNo ratings yet

- 5027 - Analysis of HeatDocument11 pages5027 - Analysis of HeatHistorianNo ratings yet

- 明志科技大學101學年度考試試題 材料工程系碩士班 不分組 材料熱力學Document1 page明志科技大學101學年度考試試題 材料工程系碩士班 不分組 材料熱力學HistorianNo ratings yet

- 29 07 2021 Planned OutagesDocument6 pages29 07 2021 Planned OutagesHistorianNo ratings yet

- Toaz - Info Assign 3 Solutions PRDocument5 pagesToaz - Info Assign 3 Solutions PRHistorianNo ratings yet

- Fanshawe Homework Lab HoursDocument7 pagesFanshawe Homework Lab Hoursafeuqyucd100% (1)

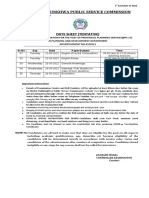

- Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Public Service Commission: Date Sheet (Tentative)Document1 pageKhyber Pakhtunkhwa Public Service Commission: Date Sheet (Tentative)Health Pros tipsNo ratings yet

- CH-1 Hospital and Their OrganizationDocument11 pagesCH-1 Hospital and Their OrganizationrevaNo ratings yet

- Casaol Case Midterm AssessmentDocument4 pagesCasaol Case Midterm AssessmentClaire ZafraNo ratings yet

- Nse IflashDocument4 pagesNse IflashNIGHT tubeNo ratings yet

- Bio AssDocument10 pagesBio AsseliasNo ratings yet

- Gateway LA 4 WhatIsTechnologyChartsDocument4 pagesGateway LA 4 WhatIsTechnologyChartsWilliam YatesNo ratings yet

- Health LessonplanDocument7 pagesHealth LessonplanLimwell Villanueva100% (1)

- Henares, Jr. v. LTFRBDocument4 pagesHenares, Jr. v. LTFRBFrancis Xavier SinonNo ratings yet

- BC Tiempo de Trombina Inserto OWNAG11E05Document6 pagesBC Tiempo de Trombina Inserto OWNAG11E05Isa Mar BCNo ratings yet

- ID NoneDocument12 pagesID Nonefirmansyaharman229No ratings yet

- Scheduled Work Order Report - L3 - 2022-03-07T163611.767Document1 pageScheduled Work Order Report - L3 - 2022-03-07T163611.767Amin CrewNo ratings yet

- 510 (K) Substantial Equivalence Determination Decision Summary Instrument Only Template A. 510 (K) NumberDocument8 pages510 (K) Substantial Equivalence Determination Decision Summary Instrument Only Template A. 510 (K) NumberdamadolNo ratings yet

- Ch-11 - Role of Employees and Customers in Service DeliveryDocument33 pagesCh-11 - Role of Employees and Customers in Service DeliveryYashashvi Rastogi100% (2)

- Pengaruh Formulasi Ekstrak Biji Ketumbar (Coriandrum Sativum) Sebagai Repellent Nyamuk Aedes Sp. Nazilia Rizqi Fitriani, Sri Muryani, S. Eko WindarsoDocument8 pagesPengaruh Formulasi Ekstrak Biji Ketumbar (Coriandrum Sativum) Sebagai Repellent Nyamuk Aedes Sp. Nazilia Rizqi Fitriani, Sri Muryani, S. Eko WindarsoNabilla Kartika SNo ratings yet

- Health Services Delivery: A Concept Note: Juan Tello Erica BarbazzaDocument72 pagesHealth Services Delivery: A Concept Note: Juan Tello Erica BarbazzaPeter OgodaNo ratings yet

- KAN U-08 Policy On Proficiency TestingDocument7 pagesKAN U-08 Policy On Proficiency TestingPrima SatriaNo ratings yet

- Document Confirming Md. Board ReprimandDocument10 pagesDocument Confirming Md. Board ReprimandDaniel MillerNo ratings yet

- A Visit To The DoctorDocument8 pagesA Visit To The DoctorrifkaNo ratings yet

- Choose The Correct Answer: Choose The Correct Answer:: Retention & StabilityDocument29 pagesChoose The Correct Answer: Choose The Correct Answer:: Retention & StabilityMostafa ElsayedNo ratings yet

- Chest TubesDocument34 pagesChest TubesMuhd ShafiqNo ratings yet

- Mbrace Carbon Fibre Laminate (All Grades) MsdsDocument3 pagesMbrace Carbon Fibre Laminate (All Grades) MsdsDoug WeirNo ratings yet

- Understanding Culture, Society, and Politics (WEEK 6-7) : What'S inDocument4 pagesUnderstanding Culture, Society, and Politics (WEEK 6-7) : What'S inRoyce Anne Marie LachicaNo ratings yet

- Formulation and Evaluation of Herbal Shampoo: Suyog Sunil Bhagwat Dr. N. J. Paulbudhe College of PharmacyDocument10 pagesFormulation and Evaluation of Herbal Shampoo: Suyog Sunil Bhagwat Dr. N. J. Paulbudhe College of Pharmacysof vitalNo ratings yet

- Bms Parent HandbookDocument22 pagesBms Parent Handbookapi-297706864No ratings yet

- Research Paper On Hospital AdministrationDocument4 pagesResearch Paper On Hospital Administrationzyjulejup0p3100% (1)

This Content Downloaded From 157.45.249.27 On Fri, 29 Oct 2021 04:01:39 UTC

This Content Downloaded From 157.45.249.27 On Fri, 29 Oct 2021 04:01:39 UTC

Uploaded by

HistorianOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

This Content Downloaded From 157.45.249.27 On Fri, 29 Oct 2021 04:01:39 UTC

This Content Downloaded From 157.45.249.27 On Fri, 29 Oct 2021 04:01:39 UTC

Uploaded by

HistorianCopyright:

Available Formats

WOMEN AND MEDICINE IN COLONIAL INDIA: A CASE STUDY OF THREE WOMEN

DOCTORS

Author(s): Sujata Mukherjee

Source: Proceedings of the Indian History Congress , 2005-2006, Vol. 66 (2005-2006), pp.

1183-1193

Published by: Indian History Congress

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/44145930

REFERENCES

Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/44145930?seq=1&cid=pdf-

reference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Indian History Congress is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

Proceedings of the Indian History Congress

This content downloaded from

157.45.249.27 on Fri, 29 Oct 2021 04:01:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

WOMEN AND MEDICINE IN COLONIAL

INDIA: A CASE STUDY OF THREE WOMEN

DOCTORS

Sujata Mukherjee

Western Science and Western Medicine were formerly often viewed as

indisputable books of colonial rule in India and elsewhere. Scholars have

recently begun to reevaluate the benefits of western medicine in the

former colonies of the western powers. Most historians now-a-days point

out that western medicine helped consolidation and expansion of colonial

rule reducing the mortality and morbidity of Europeans in tropical areas .1

Recent researches in the area of gender and medicine have also showed

how the issues of gender and health care were linked in colonial ideology

and politics and served the "civilizing" agenda of imperial rule by

propagating its paternalistic and benevolent aspects.2 This paper aims at

assessing one aspect of the role of western medicine: namely, growth of

medical education for women in colonial India by focusing on the life

and career of three Indian female doctors and hopes to enrich our

understanding of the interface of colonialism, medicine and women's

issues in British India.

David Arnold has suggested that in the first half of the 1 9th century,

in an essentially male-oriented and male-operated system of medicine,

the primary areas of concern were the army, the jails, and hospitals which

were exclusively male domains.3 The first direct state intervention into

Indian women's health came in the 1860s, in the form of the Contagious

Diseases Act (1868). It was designed to protect the health of the soldiers

and regulated the treatment and quarantine of prostitutes and soldiers in

lock hospitals to mitigate the evil of venereal diseases.4 The status of

Indian women gradually became subject of critical investigation in the

evolving discourses of colonial medicine. The zenana or the women's

quarters in upper class Hindu and Muslim households became the focus

of critical attention. One important part of the civilizing agenda of

western medicine was to break the seclusion of this zenana or

'uncolonized space' and to wage a battle against ignorance about health

and hygiene.

The first group of outsiders to attempt this were women missionaries

from the United States and England who came to India from the late

1860s. Clara Swain, who graduated from the Woman's Medical College

of Pennsylvania, was sent by the American Methodist Episcopal Mission

to Bareilly in 1869. Miss Fanny Butler of England and others established

This content downloaded from

157.45.249.27 on Fri, 29 Oct 2021 04:01:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

1 1 84 IHC: Proceedings , 66th Session , 2005-06

private clinics to provide western health care to Indian women and sought

to train midwives and nurses.5 Sporadic and piecemeal endeavours were

made by private individuals in India to provide institutional training to

Indian midwives and also to bring trained female medical graduates from

abroad. Women physicians in England favoured the proposal for

establishing medical department in India to be exclusively by and for

women.

In 1866 Mary Scharlieb, an English barrister's wife

and took a course in midwifery and then applied for adm

Medical College. In 1875 she, along with three oth

admitted to the three years' certificate course of the

College. In Calcutta Neel Kamal Mitra submitted a

Government in 1875 seeking admission of his grand

Mohini to the course at the Calcutta Medical College. In 1882 Elle

D'Abreu and Abala Das wanted to enter the Calcutta Medical College

but were turned down because they had passed only the First Arts and

not the BA examination. They went to the Madras Medical School and

studied for the certificate degree.

The first systematic and regular official attempt to provide medical

help to Indian Women started in 1885 with the establishment of the

Dufferin Fund or the National Association for Supplying Female Medical

Aid to the Women of India. Mary Scharlieb and Elizabeth Bielby

(missionary doctor at Lahore) personally met and informed Queen

Victoria about lack of medical care for Indian women and the Queen

asked Lady Dufferin, the new vicereine to investigate about the scope

of providing medical help to Indian women. On her initiative, the Fund

was established in August 1885 with 3 aims: to provide medical teaching

and training to women; to organize medical relief; to supply female

nurses and midwives in hospitals and private houses.

It is generally well known that opening of the door of medical

training to aspirant Indian female doctors was supported by enthusiastic

government officials and progressive Indians though opposed by the

members of the medical profession. The Indian middle classes' support

for female education-including medical training-was no doubt partly

prompted by an urge for providing an answer to the imperialist critique

of Hindu male behaviour towards women (which was implicit in the

Dufferin Fund advocates' reference to Indian men as a 'population which

... makes small account of the health or of the lives of women"). There

was also an urge to create compatriot wife who would bring about

discipline, order and hygienic practices in middle class home. The

Bengali male intelligentsia's agenda of social reform in the 19lh century

(as it is well-known) was immediately aimed at improving the lot of

This content downloaded from

157.45.249.27 on Fri, 29 Oct 2021 04:01:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Modem India 1 1 85

women; but it was also addressed to th

functions of middle class family life

restructuring of nation. The issue of educ

area in the agenda of reform women's c

had little to do with economic functions o

of professional expertise, etc. The main

of women's educational project was se

role expected to be played by the new

and social welfare of family members.6 T

to develop as companions to men, as scien

of civil society, they were to remain a

common or lower class women; inhabiti

popular culture.7

Large number of pedagogical texts writ

normative discourse on family which f

guidelines for an ideal housewife for pro

nurturing of children, regulation of diet

environment, etc. Parents, particularly m

themselves to be able to understand and e

to which the family had become exposed.

rearing of children, for proper knowledg

health, you should read appropriate boo

expert physicians...." Women were a

standardized, remodeled style of dom

and education on their part was seen a

family but even to the nation. It was poi

ignorant of rules of the body would no

producing weak and deficient children

Thus with the emergence of famil

restructuring was to be carried out, w

augmented status in remodeling the pr

Indian middle class internalized some of t

/ Hindu domestic life but at the same tim

ideas about bourgeois domesticity, privac

own needs. This became part of the disco

in the 19th century. Comparisons betw

were made by Bengali authors and the

of perfection while the former seemed t

order, discipline and cleanliness. The Be

to counter the notions of bourgeois p

freedom from selfishness. Even when

to be "good wives". The anxiety was p

This content downloaded from

157.45.249.27 on Fri, 29 Oct 2021 04:01:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

1 1 86 IHC: Proceedings , 66th Session , 2005-06

outlook expressed in the print media about educated women who

seemingly neglected other duties. The bhadramohila was expected to

master the technique of becoming a sugrihini by acquiring elementary

knowledge of all sorts of medical remedies for treating at least common

ailments to save the family a lot of expenses in doctors' fees.9

Brahmo reformers like Durgamohan Das, Dwarakanath Ganguly10

were enthusiastic supporters of medical education for women. A number

of newspapers and journals emphasized the need for women doctors

trained in western medicine for women patients. Brahmo Public Opinion

wrote in 1883: "If there be any one country where more than at another,

the want of lady doctors is most keenly felt, it is no doubt India. The

system of zenana seclusion makes it nearly impossible for male doctors

to be very useful in treating female patients. Consequently, a vary large

number of our women face premature death from want of proper medical

attendance... Besides, there are diseases peculiar to them, which it is

simply impossible for male doctors to diagnose or treat." The

Bamabodhini Patrika wrote: "Everyone with prudence will admit that

as for men, medical education is equally necessary for women. There

are certain types of female diseases which can only be appreciated by

women and their treatment by males cannot be as effective as by

females."

We now turn to discuss the story of Dr. Kadambini Ganguly, the

first Indian female practitioner trained in western medicine.10

In 1882, Kadambini Basu and Chandramukhi Basu became the first

graduates of Calcutta University when they finished their BA courses

from Bethune College. Kadambini (1861-1923), daughter of Brajakisore

Basu, was born at Chandsi in the district of Barisal. Her father was an

enlightened zamindar who wanted to give higher education to his

daughter. In 1883 Kadambini applied to Calcutta Medical College for

admission and was admitted when the Lieutenant Governor gave consent,

over ruling the Medical Council. Shortly after entering - Medical

College, Kadambini married thirty nine year old widower Dwarakanath

Ganguly, her teacher and mentor. In 1884 the Government announced a

scholarship of Rs.20 a month for women medical students. Kadambini

received this stipend throughout her medical studies. In 1 886 Kadambini

was awarded a GBMC (Graduate of Bengal Medical College), which

gave her the right to practice. Kadambini passed in all the written papers

for the final medical examination but failed in one essential part of the

practicáis.

In 1888, Kadambini was appointed doctor at the Lady Dufferin

Women's Hospital. She received a monthly salary of Rs.300/-. She set

up a lucrative private practice. Her patients included a member of the

This content downloaded from

157.45.249.27 on Fri, 29 Oct 2021 04:01:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Modem India 1 1 87

Nepalese royal family. In 1893 she w

studies. Kadambini was a victim of racist and sexist outlook. Her life

shows how strong gender bias was in conservative social circles.

Kadambini was only a successful doctor who competed with the male

doctor. She participated in the 1889 session of I.N.C. She entered into a

world which was dominated by men. A section of the conservative Hindu

opinion launched a slander campaign against her. It was feared that her

example would inspire other women to come out and compete with men.

The most virulent criticism was launched by Bangabasi , the journal of

Hindu orthodoxy. Kadambini was called "whore" by the author of an

article published in this journal, in 1891.

Kadambini was not only a successful doctor, she was a very

competent housewife and a mother of three children. But her great

professional success, her participation in social work and politics were

viewed with suspicion. D. Ganguly, Sivnath Sastri, and Nilratan Sarkar

started legal action against the journal and its editor. The editor Mahesh

Chandra Pal was found guilty. He was fined Rs.100 and was sentenced

to 6 months' imprisonment. By established conservative norms of

thought in Hindu society, maintenance of female virtues was

incompatible with social liberty. The male members were not ready to

allow social mobility to women, because they feared that it would slacken

their control and domination over female members. Kadambini was

however a courageous and independent lady and was fortunate to have

the support of her husband and other progressive Brahmos.

She faced not only opposition of Indian male, in workplace she also

suffered from racist bias and discrimination. After 1 885, many hospitals

and dispensaries were opened by the Duffrin Fund. They provided

employment for many women including Kadambini. But these hospitals

practiced racial discrimination. Appointments were given to white

doctors ever when more efficient Indian female doctors were available.

Kadambini held temporary posts at Calcutta zenana hospital but was

not granted a permanent post in 1891. Kadambini also complained that

Indian women were arbitrarily excluded from the best hospital jobs. This

prevented them from developing their skills: "The Indian medical women

will miss all the advantages of such professional duties by their exclusion

from the medical charge of important hospitals, or by being placed in an

inferior position there, for in the inferior class of hospitals few cases of

importance will ever go for treatment, and in the large and important

hospitals the major operations and other important duties will always

be performed by the senior person in charge".11

Kadambini considered the spread of education among women as

the chief means of improving their condition. She became the secretary

This content downloaded from

157.45.249.27 on Fri, 29 Oct 2021 04:01:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

1 188 IHC: Proceedings , 66th Session , 2005-06

of the Bengal Ladies' Association organized the Women's Conference

in Calcutta in 1906 and led a very active social and professional life.

Next we recount the life history of Haimavati Sen. She represented

another group of medical practitioners who received VLMS degree

(Vernacular Licentiate in Medical and Surgery) and served as Hospital

Assistant. They were inferior in qualification than the MB degree holders

of the Calcutta Medical College. She was a student of the Campbell

Medical School (first called the Sealdah Medical School). It was opened

in 1872 and the vernacular medical class was shifted from CMC to

Campbell. In 1853 CMC opened a Bengali language programme but it

became so popular after 2 decades that accommodation became a problem

and so new school was opened. It opened its doors to women in 1888.

Government Officials reported that there were many jobs of hospital

assistants for female candidates in the districts. The district boards could

not offer a salary of more than Rs. 30-40 per month. But medical college

graduates wanted at least Rs.300. So these posts were lying vacant.

Admission rules at Campbell were comparatively easier. Any woman

over age 1 6 could be admitted to this 3 years course. There was no upper

age limit.

In 1888 Campbell school admitted 15 women including Hindus,

Brahmos, native Christians, and Eurasians. In the first 2 years Hindu

women (belonging to Brahmin and Kayastha case) were majority. In 1 891

the first Muslim student was admitted and the second came in 1893.

After 1896 number of Bengali women students when this became a 4

year programme. The examinations became more difficult. Greater

knowledge of English was required. More native Christians, Europeans

and Eurasians entered. During 15 years 1881 - 1905 over 50 Bengali

women graduated from Campbell. The majority of them accepted jobs

in the mofussil towns.

Dr. Haimavati Sen (1866-1933) was a Campbell graduate. She

practiced medicine in Chinsurah from 1894 to 1933. Her maiden name

was H. Mitra. She wrote a memoir, translated into English by Tapan

Raychaudhuri & GeraldineForbes. Haimavati was born in Khulna. Her

father was a wealthy zamidnar. She was married at the age of 10, but

became a widow within a year. Her parents and mother-in-law died. She

was ill-treated by her brother-in-law and went to Benares & became a

teacher at a small school for girls. Hearing about Brahmo Samaj

institutions to educate widows, Haimavati came to Calcutta. She met

Brahmo leaders and remarried a Brahmo, Kunjabehari Sen. In 1891 she

entered the Campbell School. She received a scholarship of Rs.8 per

month from the Government plus school fees. In the first year

This content downloaded from

157.45.249.27 on Fri, 29 Oct 2021 04:01:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Modem India 1189

examination she stood third in her c

the highest marks in 2 papers: An

Medica. She was supposed to receiv

in her class opposed this. Ultimat

accepted silver medals instead.

She had a brilliant academic caree

She was disadvantaged by race & ge

the position of a lady doctor at Hoog

with a low salary. Her salary was R

50/-. She was placed under the sup

the civil surgeon. Her memoir tell

physically assaulted. The assistant

attempted to seduce her and even sen

complained, the civil surgeon reb

another civil surgeon treated her s

harassed her, the civil surgeons co

were appointed supervisors of the

by her. Most of them maltreated h

kindly. She also took up private prac

her income. She endured constant

personal life. She had eight pregn

was sometimes very abusive. She d

Haimavati's life was very unusual

salaried posts (as teacher, as a lady do

acceptable. In all her jobs she becam

She also had to attend to her dutie

memoir tells us a lot about violen

She fought back against all her att

that she accepted male domination

own marriage. She painted her hu

contribute financially for the fam

her money. He also made all decis

apparently she obeyed her husband

One may ask whether her descr

inequality in her memoir may be ter

as a Western ideology that casts wom

their oppression to patriarchy. Sh

organization or read their tracts. Bu

women and the fact that men d

experience as a medical student, m

of race oppression. She also saw g

be termed "radical feminism", becaus

This content downloaded from

157.45.249.27 on Fri, 29 Oct 2021 04:01:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

1 1 90 IHC: Proceedings , 66th Session , 2005-06

beings.

Another lady doctor whom we are going to discuss here is a

Maharashtrian, Anandibai Joshee (1865- 1887). 12 She deserves special

mention because she was the first lady to go abroad for medical education

and obtain an American medical degree (in 1886). She was born into an

orthodox and poor Maharashtrian Brahmin family on March 30, 1 865 in

Kalyan near Bombay. Her maiden name was Yamuna Joshi. She was

one of the 4 children who survived out of the total of 9 born to Ganpatrao

Joshi and his second wife Gangabai. She was pampered by her father

who got her admitted in a school but was treated cruelly by her mother.

She was married off at the age of 10 to Gopalrao Joshee, a 27 year old

widower. He was an eccentric men with reformist ideas. Anandi became

mother at the age of 1 2 but lost her infant son. Her health steadily declined

but she continued to study.

Gaopalrao's personal ambition and his contact with American

missionaries inspired the radical plan of taking Anandibai to America

for higher studies. Apart from her husband, two prominent women played

a crucial roles in Anandi's medical mission. One was B.F. Carpenter of

Rosselle, New Jersey, who facilitated her medical education in the USA

and the other was Pandita Ramabai, a remarkable Maharashtrian social

reformer and an early champion of feminist consciousness', who gave

her all the required moral and social support. Pandita Ramabai set up

the Mahila Arya Samaj in 1 882 to fight the male prejudices and atrocities

against women. She published a book in Marathi in June, 1882, "Stree

Dharma Neeti"' through which she exhorted her fellow Indian women

to obtain education and cultivate self reliance. She made a spirited stand

for women's education, including medical education, and the need to

appoint female teacher and inspectresses for girls' schools because of

male jealousy and tendency to obstruct women's education before the

Hunter Commission on Education, in September 1882 at Pune.

Anandibai was also in close contact with Ms Carpenter who financed

her journey to the U.S.A. on April 7, 1883, the 18 years old Anandi

sailed from Calcutta for U.S.A. She joined the Women's Medical College

of Pennsylvania at Philadelphia in October, 1883. She received her final

degree in March 1886. Pandita Ramabai was present at the ceremony.

Anandi became a victim of tuberculosis. She accepted the post of a lady

doctor in the princely state of Kolhapur in the Bombay Presidency, but

died before she could join (February 29, 1887).

Anandibai is more or less portrayed as a conformist Hindu. Her image

is that of a submissive girl-wife. But she also made progressive statements

regarding many issues. Her interest in medical education and medical

career was a personal commitment aimed at serving her fellow women.

This content downloaded from

157.45.249.27 on Fri, 29 Oct 2021 04:01:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Modem India 1191

Many scholars have pointed out th

was a feminist.

The question arises as to what is feminism or feminist consciousness

and how far this or any other concept is relevant to analyse the historical

significance of these women doctors of colonial India. Despite debates,

it may be said there are three most important elements of feminism: (a)

The belief that women are subordinated to and oppressed by men, (b)

the ideal of gender equality, and (c) action (either private or public)

towards the achievement of this ideal. The same themes surface in

"feminist consciousness" which is said to have evolved historically from

a perception of the distorted way of presenting women, to a questioning

of (patriarchal) tradition, to the final reaching out to other women in

search of sisterhood, and also in the feminist perspective which is an

attempt to describe women's oppression, to explain its causes and

consequences, and to prescribe strategies for women's liberation.

In the 1880's, (in Maharashtra and Bengal) isolated feminist voices

were raised. Women's protests were qualitatively different from the

contemporary male reformist discourse (conducted within a partially

liberal but firmly patriarchal framework and questioned many aspects

of the patriarchal value system and social institutions sustaining them).

In the cases of 60th Anandibai and Haimayati we see that their

submissive wife images apparently valorized the patriarchal ideal no

doubt. It also indicated the limits of women's achievements. But despite

this conformity to convention the education and the career of the three

doctors discussed above also enabled them to carve out a new

emancipatory space within this constricting social structure. Med

education definitely had a positive role in making them self-relian

some extent and thus contributed positively towards the growth

feminist consciousness.

NOTES AND REFERENCES

1. Some of the important studies on different aspects of medicine and colo

are: David Arnold, Colonizing the Body : State Medicine and Epidemic Dise

Nineteenth Century India , Berkley: University of California Press (1989); The

Cambridge History of India, III (5): Science, Technology and Medicine in C

India , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (2000); David Arnold (e

Imperial Medicine and Indigenous Societies, Delhi: Oxford University P

Poonam Bala , Imperialism and Medicine in Bengal : A Socio-Historical Persp

Delhi: Sage Publications (1991); Philip D. Curtin, Death by Migraiton: Eu

Encounter with the Tropical World in the Nineteenth Century ; Cambridge Uni

Press (1 989); Disease and Empire : The Health of European Troops in the Co

of Africa, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (1998); Forbes, Geraldi

Tapanray Chaudhury), The Memoirs of Dr. Haimabati Sen from Child Wid

This content downloaded from

157.45.249.27 on Fri, 29 Oct 2021 04:01:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

1192 IHC: Proceedings , 66th Session , 2005-06

Lady Doctor , New Delhi (2000); Lotus Collection; Mark Harrison, Public Health

in British India: Anglo-Indian Preventive Medicine 1859-1914, Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press (1994); Climiates and Constitutions: Health, Race ,

Environment and British Imperialism in India 1600-1850, Delhi: Oxford University

Press (1999); Daniel R. Headrick, Tools of Empire: Technology and European

Imperialism in the Nineteenth Century, New York: Oxford University Press ( 198 1 );

The Tentacles of Progress: Technology Transfer in the Age of Imperialism, 1850-

1940, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. (1998); Jaffrey, Roger

(1988), The Politics of Health in India , Berkeley, Los Angels and London: University

of California Press; Klein Ira (1972), 'Malaria and Mortality in Bengal, 1840-1921',

The Indian Economic and Social History Review , Vol. IX, No. 2, June; 'Cholera:

Theory and Treatment in Nineteenth Century India', Journal of Indian History ,

No.58, pp.35-51 (1980); 'Plague, Policy and Popular Unrest in British India',

Modern Asian Studies , No.22, pp.723-55; Kumar, Anil (1998), Medicine and the

Raj: British Medical Policy 1835-1911 , New Delhi: Sage Publications; Leslie,

Charles (ed.), (1977), Asian Medical System: A Comparative Study , California:

California University Press; MacLeod, R. and L. Milton (eds.) (1988), Disease,

Medicine and Empire: Perspectives of Western Medicine and the Experiences of

European Expansion, London: Routledge; Mukherjee, Sujata, "Women, Medicine

and Empire: Fenmale Practitioners and Patterns of Health Care in Colonial Bengal' ,

Modern Historical Studies , Vol.2; Pati, Biswamoy and H. Mark (ed.) (2001), Health,

Medicine and Empire: Perspectives on Colonial Indian , Hyderabad: Orient

Longman; Ramanna, Mridula (1995), 'Indian Practitioners of Western Medicine:

Grant Medical College, 1845-1 885 ' Radical Journal of Health, (n.s.) No. 1, pp.1 16-

35; 'Western Medicine and Public Health in Colonial Bombay, 1845-1895',

Hyderabad: Orient Longman (forthcoming); Ramasubban, R. (1982), 'Public Health

and Medical Research in India: Their Origins under the Impact of British Colonial

Policy', SAREC Report, Stockholm; 'Imperial Health in British India 1857-1900',

in R. MacLeod and M. Lewis (eds.), Disease, Medicine and Empire: Perspective

on Western Medicine and the Experience of European Expansion, London:

Routledge, pp.38-60 (1988).

2. Some of the relevant works are: Maneesha Lai, "The Politics of Gender and Medicine

in Colonial India: The Countess of Dufferin's Fund, 1885-1888", Bulletin of History

of Medicine, 68, 1994, pp. 29-66; Malavika Kearlekar, "Kadambini and the

Bhadralok." Economic and Political Weekly , 21, No. 19 (April 26, 1986), pp.WS-

25-31: Judy Whitehead, "Modernizing the Motherhood ARcherype; Public Health

Models and the Child Marriage Restraint Act of 1929", in Social Reform , Patricia

Uberoi, Sexuality and the State , ed. (New Delhi: Sage Publicaitons, 1996), pp.87-

209; Barbara N. Ramusack, "Embattled Advocates: The Debate over Birth Control

in India, 1920-40," Journal of Women's History, 1989, 1:34-64; Geraldine Forbes,

"Medical Careers and Health Care for Indian Women: patterns of control", Women 's

History Review, Vol.3, No.4, 1994-5 15-530, See sections in Geraldine Forbes, The

New Cambridge History of India, IV.2, Women in Modern India, (Cambridge

University Press, First South Asian Paperback Edition, 1998); Meredith Borthwick,

The Changing Role of Women in Bengal, 1849-1951 (Princeton: Princeton

University Press, 1984); Dagmer Engles, Beyond Pundah? Women in Bengal 1890-

1930 (Delhi: OUP, 1999).

3. David Arnold, Colonizing the Body: State Medicine and Epidemic Disease in

Nineteenth Century India (OUP, Delhi, 1993), p.7.

4. Kenneth Ballhatchet, Race, Sex, and Class under the Raj: Imperial Attitudes and

Policies and their Critics, 1893-1905 (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1980). Also

see Mridula Ramanna, "Control and Resistance: The Working of the Contagious

This content downloaded from

157.45.249.27 on Fri, 29 Oct 2021 04:01:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Modem India 1 1 93

Diseases Acts in Bombay Cit y",EPW, Vol.XX

1476.

5. G. Forbes, "Managing midwifery in India", in Dagmer Engels and Shula Marks

ed., Contesting Colonial Hegemony: State and Society in Africa and India , (The

German Historical Institute London 1994), pp. 152-3 13. Also see G. Forbes' article

in this journal.

6. Geraldine Forbes, Women in Modern India ( n.l .), p.41.

7. Sumanta Banerjee, "Marginalization of Women's Popular Culture in Nineteenth

Century Bengal", in recasting Women: Essays in Colonial History , ed., Kumkum

Sangari and Sudesh Vaid (Delhi, Kali for Women, 1989).

8. Pradip Kumar Bose, "Sons of the Nation: Child Rearing in the New Family" in

Texts of Power: Emerging Disciplines in Colonial Bengal , ed. Partha Chatterjee,

(Calcutta, 1996), p. 123.

9. See Malavika Karlekar, "Kadambini and the Bhadralok" (n.3).

10. Female physicians in Britain argued that British women desired and needed treatment

by women and would avoid close medical examination by men. M. Lai. op.cit.,

p. 43.

1 1 . Discussion on Kadambini Ganguli and her background are based on: (a) Malavika

Karlakar: "Kadambini and the Bhadralok .... (see n.2) (b) Meredith Borthwick,

The Changing Role of Women in Bengal, 1849-1905 , Princeton, Princeton

University Press, 1984, (c) Ghulam Murshid, Reluctant Debutanate - Response of

Bengali Women to Modernization , 1849-1905 , Rajshahi, Rajshahi University Press,

1982, (d) Sivnath Sastri, History of the Brahmo S a maj, Vol.1, Calcutta, R.

Chatteijee, 1911 (e) David Kopf, The Brahmo Samaj and the Shaping of the Modern

Indian Mind , New Jersey, Princeton University Press, 1979. Sujata Mukherjee -

"Patronage, Western Medicine: Gender and Health in Nineteenth Century India" in

C. Palit and A. Chatterjee (eds.) Epidemics and Empire; "Disciplinary Century

Bengal, in Deepak Kumar (ed Disease and Medicine in India: A History Overview ,

New Delhi, 2001. Srilata Chatterjee, "Colonial Women, Medicine and Medical

Education in Bengal 1884-1940" in Women's Education and Politics of Gender,

Kolkata, 2004.

12. Account of Anandibai Joshee are based on: (a) Caroline Healey, the Dall, The Life

of Dr. Anandibai Joshee , Roberts Brothers, Boston. Anandi (b) S.S. Joshee Gopal,

Majestic Book Stall, Bombay, 2nd ed. 1970, (c) Meera Kosambi, "Women and

Equality: Pandita Ramabai's Contribution to the Women's Cause", EPW, Vol.XXIII,

as 44, October 29, Review of Women studies, ppWS 38-49. (d) Rosemarie Tong,

Feminist Thought: A Comprehensive Introduction.

This content downloaded from

157.45.249.27 on Fri, 29 Oct 2021 04:01:39 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Sandy Hook ReportDocument284 pagesSandy Hook ReportLeakSourceInfoNo ratings yet

- Speech and Hearing Science in Ancient India-A Review of Sanskrit LiteratureDocument47 pagesSpeech and Hearing Science in Ancient India-A Review of Sanskrit LiteratureNeem Plant100% (1)

- Trends and Issues in Nursing EducationDocument23 pagesTrends and Issues in Nursing EducationShivani Tiwari50% (2)

- DPR of School of Nursing Under GimsDocument41 pagesDPR of School of Nursing Under GimsSubha PradhanNo ratings yet

- Trends in Development of Nursing Education in IndiaDocument13 pagesTrends in Development of Nursing Education in IndiaDhAiRyA ArOrA90% (10)

- Medical Encounters in British IndiaDocument82 pagesMedical Encounters in British Indiadarkknight2809100% (1)

- Sympathy and Science: Women Physicians in American MedicineFrom EverandSympathy and Science: Women Physicians in American MedicineRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- History of NursingDocument7 pagesHistory of NursingMahenurNo ratings yet

- Assignment 1Document161 pagesAssignment 1Rashmi C S0% (1)

- Kayla Flaskerud Vsim BP Concept Map, Isbar, ClincialDocument12 pagesKayla Flaskerud Vsim BP Concept Map, Isbar, ClincialCameron Janzen100% (1)

- 3 Week Diet PDFDocument52 pages3 Week Diet PDFMaja Zivanovic100% (1)

- Rural Marketing: Assignment ofDocument8 pagesRural Marketing: Assignment ofNeha GoyalNo ratings yet

- Alavi Islam Healing MasDocument46 pagesAlavi Islam Healing MasCheriCheNo ratings yet

- College of Nursing East Coast Institute of Medical Sciences, PondicherryDocument16 pagesCollege of Nursing East Coast Institute of Medical Sciences, PondicherryRuby Sri100% (1)

- (Neha Ellis) TRENDS and ISSUES in Nursing EducationDocument18 pages(Neha Ellis) TRENDS and ISSUES in Nursing EducationSunanda SharmaNo ratings yet

- Indigenous and Western Medicine in Colonial India (Z-Lib - Io)Document192 pagesIndigenous and Western Medicine in Colonial India (Z-Lib - Io)sarah shaikhNo ratings yet

- Trends & Issues NeDocument16 pagesTrends & Issues NeDhAiRyA ArOrA0% (1)

- Trends in Development of Nursing Education in IndiaDocument22 pagesTrends in Development of Nursing Education in IndiaShyam82% (11)

- Burton CleetusDocument27 pagesBurton CleetusMalavikaNo ratings yet

- Trends in Development of Nursing Education in IndiaDocument22 pagesTrends in Development of Nursing Education in IndiaAthira PS100% (1)

- History Project Sem2Document15 pagesHistory Project Sem2karthik1993No ratings yet

- Historical Developmentof Health Carein IndiaDocument8 pagesHistorical Developmentof Health Carein IndiaChar LeeNo ratings yet

- 20LLB067 History I EssayDocument21 pages20LLB067 History I EssayMahathi BokkasamNo ratings yet

- Trend in Development of Nursing EducationDocument21 pagesTrend in Development of Nursing EducationArchana Sahu0% (1)

- ETHICAL LEGAL PRINCIPLES IN CHNDocument32 pagesETHICAL LEGAL PRINCIPLES IN CHNJEEJANo ratings yet

- Deepak Kumar-Indian Medicin AurvedaDocument19 pagesDeepak Kumar-Indian Medicin Aurvedavivek555555No ratings yet

- A Bird's Eye View On Indian Healthcare SectorDocument9 pagesA Bird's Eye View On Indian Healthcare SectorInternational Journal of Application or Innovation in Engineering & ManagementNo ratings yet

- Struggle For Muslim Women's Rights in 1857-1947Document35 pagesStruggle For Muslim Women's Rights in 1857-1947Salman SafdarNo ratings yet

- Damodaram Sanjivayya National Law University Visakhapatnam, Andhra PradeshDocument22 pagesDamodaram Sanjivayya National Law University Visakhapatnam, Andhra PradeshSiddi SrikarNo ratings yet

- The Malabar ExperienceDocument46 pagesThe Malabar ExperienceBalakrishna GopinathNo ratings yet

- Subrata Pahari - Kaviraj - Daktar ConflictDocument12 pagesSubrata Pahari - Kaviraj - Daktar Conflict\No ratings yet

- Christianity and Nursing in India: A Remarkable ImpactDocument8 pagesChristianity and Nursing in India: A Remarkable ImpactRonald JosephNo ratings yet

- Trends in Development of Nursing Education in Indi1Document21 pagesTrends in Development of Nursing Education in Indi1anjanaNo ratings yet

- Unit I RevisedDocument18 pagesUnit I RevisedprathibaNo ratings yet

- Women Empowerment or Feminism Facts and Myths Abou PDFDocument3 pagesWomen Empowerment or Feminism Facts and Myths Abou PDFApoorv TripathiNo ratings yet

- 10 - Chapter 1 PDFDocument34 pages10 - Chapter 1 PDFRajeshNo ratings yet

- Project - PDocument88 pagesProject - PabbyNo ratings yet

- Ayurveda in The Time of CovidDocument23 pagesAyurveda in The Time of Covidmeera54No ratings yet

- Terminologies: 1. THEORETICAL FOUNDATION OF NURSING - The Central Concept of Health, Person, EnvironmentDocument12 pagesTerminologies: 1. THEORETICAL FOUNDATION OF NURSING - The Central Concept of Health, Person, EnvironmentSofia Yuki SakataNo ratings yet

- SKH April 2015Document147 pagesSKH April 2015Ramesha-NiratankaNo ratings yet

- Medical Ethics in India: February 2018Document20 pagesMedical Ethics in India: February 2018Sravs PanduNo ratings yet

- Essay 1Document5 pagesEssay 1Dalal RidayNo ratings yet

- Nursing India: and inDocument7 pagesNursing India: and inRonald JosephNo ratings yet

- Urdhva Mula - Roots Upwards: An Interdisciplinary Peer Reviewed Women's Studies Journal, Vol. 10, 2017 PDFDocument156 pagesUrdhva Mula - Roots Upwards: An Interdisciplinary Peer Reviewed Women's Studies Journal, Vol. 10, 2017 PDFProf. Vibhuti PatelNo ratings yet

- 14 Chapter 5Document51 pages14 Chapter 5Narasimha Swamy VodapallyNo ratings yet

- Seminar 2 - Historical Development in Medical Surgical Nursing in IndiaDocument90 pagesSeminar 2 - Historical Development in Medical Surgical Nursing in Indiasaranya amuNo ratings yet

- LeslieDocument3 pagesLesliepriyadarshineepratikshya5No ratings yet

- Evolution of Health ServicesDocument8 pagesEvolution of Health ServicesUma ZoomaNo ratings yet

- The Historical Roots of The Feminist Consciousness in The 19th Century Social Reform MovementDocument8 pagesThe Historical Roots of The Feminist Consciousness in The 19th Century Social Reform MovementArchana shuklaNo ratings yet

- AyurvedaDocument108 pagesAyurvedaManoj SankaranarayanaNo ratings yet

- Review A Tte WellDocument4 pagesReview A Tte WellSyed Mohammed AmmarNo ratings yet

- Textbook Ebook Looking Through The Speculum Examining The Womens Health Movement Judith A Houck All Chapter PDFDocument43 pagesTextbook Ebook Looking Through The Speculum Examining The Womens Health Movement Judith A Houck All Chapter PDFpeggy.wilson373100% (8)

- History of Nursing and Their Role in Modern HealthcareDocument8 pagesHistory of Nursing and Their Role in Modern Healthcaresadithyan726No ratings yet

- History of Developmrnt of Nursing ProfessionDocument10 pagesHistory of Developmrnt of Nursing ProfessionHanison MelwynNo ratings yet

- In the Bonesetter's Waiting Room: Travels Through Indian MedicineFrom EverandIn the Bonesetter's Waiting Room: Travels Through Indian MedicineRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- Introduction To Nursing FON-IDocument46 pagesIntroduction To Nursing FON-Imuhammadsalman0317090No ratings yet

- Sexual Rights and Gender Roles in A Religious Context PDFDocument5 pagesSexual Rights and Gender Roles in A Religious Context PDFLorena RodríguezNo ratings yet

- Women and LawDocument18 pagesWomen and LawShubhankar JohariNo ratings yet

- 6 - Brigitte SA Bastia 14 05 2011 PDFDocument30 pages6 - Brigitte SA Bastia 14 05 2011 PDFaatreyaprathibanNo ratings yet

- 6 - Brigitte SA Bastia 14 05 2011 PDFDocument30 pages6 - Brigitte SA Bastia 14 05 2011 PDFaatreyaprathibanNo ratings yet

- Competing For Medical Space: To Cite This VersionDocument30 pagesCompeting For Medical Space: To Cite This VersionaatreyaprathibanNo ratings yet

- Details of The Objectives AchievedDocument2 pagesDetails of The Objectives AchievedabbyNo ratings yet

- Tribal MedicineDocument61 pagesTribal MedicineKuntal ChaudhuryNo ratings yet

- Caring and Curing: Historical Perspectives on Women and Healing in CanadaFrom EverandCaring and Curing: Historical Perspectives on Women and Healing in CanadaDianne DoddNo ratings yet

- 31 07 2021 Planned OutagesDocument5 pages31 07 2021 Planned OutagesHistorianNo ratings yet

- Rolling MM3041Document17 pagesRolling MM3041HistorianNo ratings yet

- 5027 - Analysis of HeatDocument11 pages5027 - Analysis of HeatHistorianNo ratings yet

- 明志科技大學101學年度考試試題 材料工程系碩士班 不分組 材料熱力學Document1 page明志科技大學101學年度考試試題 材料工程系碩士班 不分組 材料熱力學HistorianNo ratings yet

- 29 07 2021 Planned OutagesDocument6 pages29 07 2021 Planned OutagesHistorianNo ratings yet

- Toaz - Info Assign 3 Solutions PRDocument5 pagesToaz - Info Assign 3 Solutions PRHistorianNo ratings yet

- Fanshawe Homework Lab HoursDocument7 pagesFanshawe Homework Lab Hoursafeuqyucd100% (1)

- Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Public Service Commission: Date Sheet (Tentative)Document1 pageKhyber Pakhtunkhwa Public Service Commission: Date Sheet (Tentative)Health Pros tipsNo ratings yet

- CH-1 Hospital and Their OrganizationDocument11 pagesCH-1 Hospital and Their OrganizationrevaNo ratings yet

- Casaol Case Midterm AssessmentDocument4 pagesCasaol Case Midterm AssessmentClaire ZafraNo ratings yet

- Nse IflashDocument4 pagesNse IflashNIGHT tubeNo ratings yet

- Bio AssDocument10 pagesBio AsseliasNo ratings yet

- Gateway LA 4 WhatIsTechnologyChartsDocument4 pagesGateway LA 4 WhatIsTechnologyChartsWilliam YatesNo ratings yet

- Health LessonplanDocument7 pagesHealth LessonplanLimwell Villanueva100% (1)

- Henares, Jr. v. LTFRBDocument4 pagesHenares, Jr. v. LTFRBFrancis Xavier SinonNo ratings yet

- BC Tiempo de Trombina Inserto OWNAG11E05Document6 pagesBC Tiempo de Trombina Inserto OWNAG11E05Isa Mar BCNo ratings yet

- ID NoneDocument12 pagesID Nonefirmansyaharman229No ratings yet

- Scheduled Work Order Report - L3 - 2022-03-07T163611.767Document1 pageScheduled Work Order Report - L3 - 2022-03-07T163611.767Amin CrewNo ratings yet

- 510 (K) Substantial Equivalence Determination Decision Summary Instrument Only Template A. 510 (K) NumberDocument8 pages510 (K) Substantial Equivalence Determination Decision Summary Instrument Only Template A. 510 (K) NumberdamadolNo ratings yet

- Ch-11 - Role of Employees and Customers in Service DeliveryDocument33 pagesCh-11 - Role of Employees and Customers in Service DeliveryYashashvi Rastogi100% (2)

- Pengaruh Formulasi Ekstrak Biji Ketumbar (Coriandrum Sativum) Sebagai Repellent Nyamuk Aedes Sp. Nazilia Rizqi Fitriani, Sri Muryani, S. Eko WindarsoDocument8 pagesPengaruh Formulasi Ekstrak Biji Ketumbar (Coriandrum Sativum) Sebagai Repellent Nyamuk Aedes Sp. Nazilia Rizqi Fitriani, Sri Muryani, S. Eko WindarsoNabilla Kartika SNo ratings yet

- Health Services Delivery: A Concept Note: Juan Tello Erica BarbazzaDocument72 pagesHealth Services Delivery: A Concept Note: Juan Tello Erica BarbazzaPeter OgodaNo ratings yet

- KAN U-08 Policy On Proficiency TestingDocument7 pagesKAN U-08 Policy On Proficiency TestingPrima SatriaNo ratings yet

- Document Confirming Md. Board ReprimandDocument10 pagesDocument Confirming Md. Board ReprimandDaniel MillerNo ratings yet

- A Visit To The DoctorDocument8 pagesA Visit To The DoctorrifkaNo ratings yet

- Choose The Correct Answer: Choose The Correct Answer:: Retention & StabilityDocument29 pagesChoose The Correct Answer: Choose The Correct Answer:: Retention & StabilityMostafa ElsayedNo ratings yet

- Chest TubesDocument34 pagesChest TubesMuhd ShafiqNo ratings yet

- Mbrace Carbon Fibre Laminate (All Grades) MsdsDocument3 pagesMbrace Carbon Fibre Laminate (All Grades) MsdsDoug WeirNo ratings yet

- Understanding Culture, Society, and Politics (WEEK 6-7) : What'S inDocument4 pagesUnderstanding Culture, Society, and Politics (WEEK 6-7) : What'S inRoyce Anne Marie LachicaNo ratings yet

- Formulation and Evaluation of Herbal Shampoo: Suyog Sunil Bhagwat Dr. N. J. Paulbudhe College of PharmacyDocument10 pagesFormulation and Evaluation of Herbal Shampoo: Suyog Sunil Bhagwat Dr. N. J. Paulbudhe College of Pharmacysof vitalNo ratings yet

- Bms Parent HandbookDocument22 pagesBms Parent Handbookapi-297706864No ratings yet

- Research Paper On Hospital AdministrationDocument4 pagesResearch Paper On Hospital Administrationzyjulejup0p3100% (1)