Professional Documents

Culture Documents

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

13 viewsHow To Manage Early Embryonic Death: Tom A.E. Stout, Vetmb, PHD

How To Manage Early Embryonic Death: Tom A.E. Stout, Vetmb, PHD

Uploaded by

Mittu KurianCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You might also like

- Palos Used Within The Regla Conga and Its Qualities EnglishDocument11 pagesPalos Used Within The Regla Conga and Its Qualities Englishngolo1100% (7)

- Bovine Abortion: General CommentsDocument11 pagesBovine Abortion: General CommentsDio DvmNo ratings yet

- Endometrial Decidualization: The Primary Driver of Pregnancy HealthDocument20 pagesEndometrial Decidualization: The Primary Driver of Pregnancy HealthSherilinne Quiles LópezNo ratings yet

- Immunology of PreeclampsiaDocument13 pagesImmunology of PreeclampsiaRohmantuah_Tra_1826No ratings yet

- Artigo 1 PDFDocument9 pagesArtigo 1 PDFLarissa F SNo ratings yet

- rbjQS9 BREECH PRESENTATION-AN OVERVIEWDocument6 pagesrbjQS9 BREECH PRESENTATION-AN OVERVIEWYosita AuroraNo ratings yet

- Placenta As Witness 07Document15 pagesPlacenta As Witness 07Vetési OrsolyaNo ratings yet

- Etiology, Clinical Manifestations, and Prediction of Placental AbruptionDocument9 pagesEtiology, Clinical Manifestations, and Prediction of Placental AbruptionKadije OanaNo ratings yet

- Etiology of Preeclampsia: An UpdateDocument9 pagesEtiology of Preeclampsia: An UpdateSares DaselvaNo ratings yet

- Differential DiagnosisDocument85 pagesDifferential DiagnosisSayyeda niha AkhtarNo ratings yet

- Proceedings of The 16th Italian Association of Equine Veterinarians CongressDocument6 pagesProceedings of The 16th Italian Association of Equine Veterinarians CongressCabinet VeterinarNo ratings yet

- Fetal and Neonatal Gene Therapy: Benefits and Pitfalls: ReviewDocument6 pagesFetal and Neonatal Gene Therapy: Benefits and Pitfalls: Reviewbhoopendra chauhanNo ratings yet

- A Review On Dystocia in CowsDocument10 pagesA Review On Dystocia in CowsMuhammad JameelNo ratings yet

- Lecture 10 - Repeat BreedingDocument2 pagesLecture 10 - Repeat Breedingkushal NeupaneNo ratings yet

- Abnormal LabourDocument21 pagesAbnormal LabourbetablockersNo ratings yet

- Early Embryonic Mortality Bovine-1Document9 pagesEarly Embryonic Mortality Bovine-1M Huzefa SudaisNo ratings yet

- Etiology of Preeclampsia: An UpdateDocument9 pagesEtiology of Preeclampsia: An UpdateRadi PdNo ratings yet

- Pseudo Pregnancy in DogsDocument11 pagesPseudo Pregnancy in DogsKay ChuaNo ratings yet

- Prematurity, Dysmaturity, Postmaturity PDFDocument8 pagesPrematurity, Dysmaturity, Postmaturity PDFMuhammad YaminNo ratings yet

- The Physiology of Intrapartum Fetal Compromise at Term: Sailesh. Kumar@mater - Uq.edu - AuDocument10 pagesThe Physiology of Intrapartum Fetal Compromise at Term: Sailesh. Kumar@mater - Uq.edu - AuseopyNo ratings yet

- Journal - The Physiology of Intrapartum Fetal Compromise at TermDocument10 pagesJournal - The Physiology of Intrapartum Fetal Compromise at TermbedahfkumiNo ratings yet

- The Placenta: Transcriptional, Epigenetic, and Physiological Integration During DevelopmentDocument10 pagesThe Placenta: Transcriptional, Epigenetic, and Physiological Integration During Developmentpam!!!!No ratings yet

- Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecologic Emergencies 2023Document13 pagesPediatric and Adolescent Gynecologic Emergencies 2023Paola LecuonaNo ratings yet

- Crypt Orchid IsmDocument6 pagesCrypt Orchid IsmJayson Almario AranasNo ratings yet

- Immunology of EclampsiaDocument10 pagesImmunology of EclampsiaTiara AnggianisaNo ratings yet

- BaithaluDocument3 pagesBaithaluRiba FisherNo ratings yet

- Maternal Recognition of Pregnancy'Document9 pagesMaternal Recognition of Pregnancy'Jhoel CbNo ratings yet

- Preterm Birth 1: Epidemiology and Causes of Preterm BirthDocument13 pagesPreterm Birth 1: Epidemiology and Causes of Preterm BirthninachayankNo ratings yet

- Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand - 2011 - TIKKANENDocument9 pagesActa Obstet Gynecol Scand - 2011 - TIKKANENsawsanNo ratings yet

- Pre EclampsiaDocument12 pagesPre EclampsiaJohn Mark PocsidioNo ratings yet

- LactogenesisDocument4 pagesLactogenesisMaría Luz IglesiasNo ratings yet

- Fetal Membrane Healing After Spontaneous and Iatrogenic Membrane Rupture: A Review of Current EvidenceDocument9 pagesFetal Membrane Healing After Spontaneous and Iatrogenic Membrane Rupture: A Review of Current EvidenceNi Wayan Ana PsNo ratings yet

- Antenatal ProfileDocument6 pagesAntenatal ProfileSinchan GhoshNo ratings yet

- Disorders of FoalsDocument96 pagesDisorders of FoalsLaura VillotaNo ratings yet

- Breech Za NigeriaqDocument10 pagesBreech Za NigeriaqRendra Artha Ida BagusNo ratings yet

- 2024 04 23 - PaperDocument20 pages2024 04 23 - PaperdrmanashreesankheNo ratings yet

- Hormonal Causes of RPLDocument9 pagesHormonal Causes of RPLHervi LaksariNo ratings yet

- Intensive Care of The Neonatal FoalDocument32 pagesIntensive Care of The Neonatal FoalAristoteles Esteban Cine VelazquezNo ratings yet

- Molecular Mechanism of ImplantationDocument19 pagesMolecular Mechanism of ImplantationAbunu TilayeNo ratings yet

- Hormonal Causes of Recurrent Pregnancy Loss RPLDocument10 pagesHormonal Causes of Recurrent Pregnancy Loss RPLQONITA PRASTANo ratings yet

- Dekker 2011Document7 pagesDekker 2011tizardwiNo ratings yet

- Abdomina Wall Defects 2Document12 pagesAbdomina Wall Defects 2pamellapesseNo ratings yet

- Joacp 32 153Document7 pagesJoacp 32 153thresh mainNo ratings yet

- The "Vanishing Twin" Syndrome - A Myth or Clinical Reality in The Obstetric Practice?Document3 pagesThe "Vanishing Twin" Syndrome - A Myth or Clinical Reality in The Obstetric Practice?ariniNo ratings yet

- Obgyn SGDocument40 pagesObgyn SGNatalieNo ratings yet

- Early Part ComplicationDocument86 pagesEarly Part ComplicationyewollolijfikreNo ratings yet

- PIIS0002937823001564Document2 pagesPIIS0002937823001564Kalaivathanan VathananNo ratings yet

- Umbilical Cord Prolapse - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfDocument5 pagesUmbilical Cord Prolapse - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelfhermalina sabruNo ratings yet

- GariteDocument3 pagesGariteOkki Masitah Syahfitri NasutionNo ratings yet

- OmphalitisDocument21 pagesOmphalitisdaisukeNo ratings yet

- Pathogenesis of Preeclampsia: The Genetic ComponentDocument9 pagesPathogenesis of Preeclampsia: The Genetic ComponentchandradwtrNo ratings yet

- ProlapseDocument6 pagesProlapseJack GervasNo ratings yet

- EcheverríaSepúlveda2022 Article TheUndescendedTestisInChildrenDocument7 pagesEcheverríaSepúlveda2022 Article TheUndescendedTestisInChildrenMELVIN JOHNNo ratings yet

- IUFDDocument12 pagesIUFDhacker ammerNo ratings yet

- Huppert Z 2008Document7 pagesHuppert Z 2008Alfa FebriandaNo ratings yet

- Pregnancy Losses in MaresDocument29 pagesPregnancy Losses in MaresMittu Kurian100% (1)

- Placental Disease and The Maternal Syndrome of Preeclampsia: Missing Links?Document10 pagesPlacental Disease and The Maternal Syndrome of Preeclampsia: Missing Links?della psNo ratings yet

- Lacto GenesisDocument5 pagesLacto GenesisWISKA VERRENZA -No ratings yet

- Guide to Pediatric Urology and Surgery in Clinical PracticeFrom EverandGuide to Pediatric Urology and Surgery in Clinical PracticeNo ratings yet

- Ovulation Induction and Controlled Ovarian Stimulation: A Practical GuideFrom EverandOvulation Induction and Controlled Ovarian Stimulation: A Practical GuideNo ratings yet

- Equine PlacentaDocument16 pagesEquine PlacentaMittu KurianNo ratings yet

- Dog Behaviour Problems: Why Do They Do It and What Can You Do?Document12 pagesDog Behaviour Problems: Why Do They Do It and What Can You Do?Mittu KurianNo ratings yet

- Intra Partum ConditionsDocument19 pagesIntra Partum ConditionsMittu KurianNo ratings yet

- Impotentia Coeundi and Impotentia Generandi: A Male Infertility (Abstractview - Aspx?Pid 2016-8-2-8)Document15 pagesImpotentia Coeundi and Impotentia Generandi: A Male Infertility (Abstractview - Aspx?Pid 2016-8-2-8)Mittu KurianNo ratings yet

- Pregnancy Losses in MaresDocument29 pagesPregnancy Losses in MaresMittu Kurian100% (1)

- Advances in Equine ReproductionDocument5 pagesAdvances in Equine ReproductionMittu KurianNo ratings yet

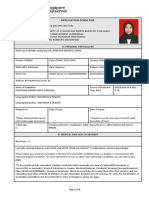

- TF SCALE 2022 Application Form (Students)Document4 pagesTF SCALE 2022 Application Form (Students)Crew TabolangNo ratings yet

- ALS Canada Infographic For Inspiration To OthersDocument1 pageALS Canada Infographic For Inspiration To OtherslukeydimatteoNo ratings yet

- Online Healthcare Information Adoption Assessment Using Text Mining TechniquesDocument6 pagesOnline Healthcare Information Adoption Assessment Using Text Mining TechniquesRizqi AUNo ratings yet

- Pcos ApprovedDocument30 pagesPcos ApprovedEsha BhatiaNo ratings yet

- Blyncsy PATROLL Contest WinnerDocument11 pagesBlyncsy PATROLL Contest WinnerJennifer M Gallagher100% (1)

- Surgically-Assisted Rapid Palatal Expansion For Management of Transverse Maxillary DeficiencyDocument3 pagesSurgically-Assisted Rapid Palatal Expansion For Management of Transverse Maxillary DeficiencyDaniela CastilloNo ratings yet

- J Tmaid 2019 101503Document33 pagesJ Tmaid 2019 101503rivanNo ratings yet

- San Francisco Baseball Old Timers Association "From The Dugout" September 2021 EditionDocument6 pagesSan Francisco Baseball Old Timers Association "From The Dugout" September 2021 EditionKris K KimballNo ratings yet

- Lutfia Papita Derizky R. 1610911120024Document17 pagesLutfia Papita Derizky R. 1610911120024lutfia papitaNo ratings yet

- Peptic Ulcer DiseaseDocument22 pagesPeptic Ulcer Diseaserosamundrae100% (1)

- Antituberculars, Antifungals, and AntiviralsDocument44 pagesAntituberculars, Antifungals, and Antiviralsmam2017No ratings yet

- Class Ii Malocclusion: Usman & MehmoodDocument41 pagesClass Ii Malocclusion: Usman & MehmoodmehmudbhattiNo ratings yet

- Appellant's BriefDocument12 pagesAppellant's BriefGinny PañoNo ratings yet

- 28.04.2021 NTEP - RNTCP Dr. Tanuja PattankarDocument29 pages28.04.2021 NTEP - RNTCP Dr. Tanuja PattankarTanuja PattankarNo ratings yet

- S23 - School Mental Health Programs in IndiaDocument22 pagesS23 - School Mental Health Programs in IndiaSukanya KhanikarNo ratings yet

- The Normal Range of Mouth OpeningDocument2 pagesThe Normal Range of Mouth OpeningMarco CarranzaNo ratings yet

- On The Clear Evidence of The Risks To Children From Smartphone and WiFi Radio Frequency Radiation - FinalDocument20 pagesOn The Clear Evidence of The Risks To Children From Smartphone and WiFi Radio Frequency Radiation - FinalNicolas CasanovaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1198743X17305268 MainDocument14 pages1 s2.0 S1198743X17305268 MainAizaz HassanNo ratings yet

- MAPEH 10 Q1 Week 4-HealthDocument10 pagesMAPEH 10 Q1 Week 4-HealthMyla MillapreNo ratings yet

- Temporo Mandibular JointDocument146 pagesTemporo Mandibular Jointdentistpro.orgNo ratings yet

- Manuskrip - Eng (1) BismillahDocument12 pagesManuskrip - Eng (1) BismillahSinta SamhanaNo ratings yet

- Beta 2 MicroglobulinDocument6 pagesBeta 2 MicroglobulinMohamed FaizalNo ratings yet

- Schizophrenia: Psychiatric Nursing Clinical Case PresentationDocument124 pagesSchizophrenia: Psychiatric Nursing Clinical Case PresentationBenedict James BermasNo ratings yet

- Airvo 2 User Manual Ui 185045495Document220 pagesAirvo 2 User Manual Ui 185045495ST HospitalNo ratings yet

- Pain Disability IndexDocument4 pagesPain Disability Indexapi-496718295No ratings yet

- Phase 1Document20 pagesPhase 1divya oNo ratings yet

- ICH Endorsed Guide For MeDRA User 1 - Mar2014Document51 pagesICH Endorsed Guide For MeDRA User 1 - Mar2014Héctor PincheiraNo ratings yet

- Notes On Forensic MedicineDocument59 pagesNotes On Forensic Medicineranjithreddy916gmailNo ratings yet

- Obstetric Case AnalysisDocument2 pagesObstetric Case AnalysisDud AccNo ratings yet

How To Manage Early Embryonic Death: Tom A.E. Stout, Vetmb, PHD

How To Manage Early Embryonic Death: Tom A.E. Stout, Vetmb, PHD

Uploaded by

Mittu Kurian0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

13 views3 pagesOriginal Title

EED mgt

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

13 views3 pagesHow To Manage Early Embryonic Death: Tom A.E. Stout, Vetmb, PHD

How To Manage Early Embryonic Death: Tom A.E. Stout, Vetmb, PHD

Uploaded by

Mittu KurianCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 3

HOW TO MANAGE THE SUBFERTILE MARE

How to Manage Early Embryonic Death

Tom A.E. Stout, VetMB, PhD

Author’s address: Utrecht University, Department of Equine Sciences, Yalelaan 114, Utrecht, The

Netherlands; e-mail: T.A.E.Stout@uu.nl. © 2012 AAEP.

1. Introduction suggest that inadequate maintenance of CL function

During the past 20 years, per-cycle and per-season is a common cause of EED. Recently, there have

pregnancy rates have improved markedly in well- been attempts to determine factors other than pro-

managed horse farms. By contrast, early embry- gesterone insufficiency that cause or predispose to

onic death (EED) has remained a significant cause of EED.

frustration and economic loss, with approximately

15% of pregnancies detected at day 15 after ovula- Causes of Early Embryonic Death

tion failing to survive to term.1 Moreover, the ma- Factors contributing to EED can be broadly divided

jority (⬎60%) of these losses occur before day 42 into embryonic abnormalities, inadequacy of the ma-

after ovulation, a period when pregnancy mainte- ternal environment and “external” factors. Indeed,

nance is critically dependent on progesterone pro- it is increasingly clear that abnormalities of the

duced by the primary corpus luteum (CL), and when embryo per se account for a significant proportion of

a number of essential developmental events take EEDs. In some cases there may even be ultrasono-

place, including maternal recognition of pregnancy, graphically detectable signs that conceptus develop-

embryogenesis and initial organogenesis, disinte- ment is not progressing normally, such as an

gration of the blastocyst capsule, endometrial cup abnormally small vesicle or failure to develop an

formation, and the onset of definitive (chorio-allan- embryo properly at the appropriate time.3 In addi-

toic) placenta formation.2 Despite its economic im- tion, it appears that a high percentage of equine

pact, surprisingly little is known about why EED embryos contain chromosomally abnormal cells,

occurs and whether, how and to what extent EED mostly in insignificant quantities but occasionally in

can be prevented. This is largely because EED is proportions certain to compromise embryo viabil-

usually diagnosed retrospectively (ie, the conceptus ity.4 Although little is known about the true im-

has already disappeared or is obviously dying), pact of chromosomal abnormalities on fertility and

when it is no longer possible to reliably establish the EED in horses, it is likely that they contribute to the

initiating cause. In addition, there has been a ten- increased incidence of EED characteristic of older

dency to assume that the underlying problem is mares, even when oocyte or embryo transfer is used

probably “progesterone insufficiency,” more because to negate uterine inadequacy,5 and in mares insem-

this is a deficit that can be addressed pharmacolog- inated “too long” after ovulation.6 In addition, it

ically than because there is any real evidence to has recently become apparent that repeated EED

NOTES

AAEP PROCEEDINGS Ⲑ Vol. 58 Ⲑ 2012 331

Orig. Op. OPERATOR: Session PROOF: PE’s: AA’s: COMMENTS ARTNO:

HOW TO MANAGE THE SUBFERTILE MARE

can occur in mares that themselves carry a stable required for conceptus development. Age-related

chromosomal abnormality (eg, a translocation) that endometrial degeneration can also markedly af-

has remained undiagnosed because it causes no fect the supply of nutrients to a conceptus, and

other obvious clinical signs.7 Similarly, it is likely although this classically leads to fetal compromise

that in some of the stallions associated with above- later in gestation, EED can result if endometrial

average rates of EED, the underlying problem is degeneration is severe or if large lymphatic cysts

embryonic chromosome abnormalities arising either impede conceptus migration or nutrient uptake.

from karyotypic abnormalities of the stallion or from Finally, there are reports that stress in the form of

DNA damage or instability in his sperm.8 pain, systemic disease, weaning, transport, changes

”Deficiencies of the maternal environment” is a in group structure, poor nutrition, or extremes of

broad concept encompassing diverse factors such as temperature can predispose to pregnancy loss.10,11

insufficient maternal progesterone; inadequate pro- Although the extent to which stress contributes to

vision of nutrients from an aged, degenerate, or in- EED is not known, it is nevertheless prudent to

adequately synchronized endometrium (eg, after minimize exposure to the potential stressors listed

embryo transfer); and infection/inflammation as a above during early pregnancy.

result of unresolved postbreeding endometritis, en-

dometritis acquired subsequently (ie, ascending or Treatment or Prevention of Embryonic Death

by “reactivation of dormant micro-organisms”) be-

cause, for example, of inadequate closure of the cer- Many of the measures that can be taken to reduce

vix, the vestibular-vaginal “sphincter,” and/or the the risk of EED are nonspecific and involve atten-

vulva. Uterine infection can also be induced during tion to good breeding management (eg, prevent post-

embryo transfer, either because the embryo was re- breeding endometritis and correct anatomical

covered from an infected mare or because of the defects predisposing to pneumovagina or urova-

accidental introduction of bacteria during transfer; gina), selection of mares (eg, retire mares with poor

the limited ability of the diestrous uterus to combat endometrium quality or a badly damaged cervix),

bacterial proliferation explains the relative ease minimizing stress, and minimizing the risk of intro-

with which contamination at this time results in an ducing or spreading infectious disease among

active infection. EED due to endometritis may broodmares.

present as the accumulation of uterine fluid or wide- There are few pharmacological means of prevent-

spread and marked uterine edema, despite the pres- ing EED, and not all of the underlying causes are

ence of a conceptus and subsequent conceptus death amenable to treatment. Progestagen supplementa-

will result either from direct infection of the embryo tion can avert EED when a mare shows clear signs

or via luteolysis due to prostaglandin F (PGF)2␣ of returning to estrus despite the presence of an

release from an inflamed endometrium. apparently normal conceptus in her uterus, has a

Although it is tempting to assume that inadequate history of repeated EED associated with loss of the

maternal progesterone is a major contributor to primary CL, is endotoxemic, or has undergone se-

EED, there is little evidence to support this assump- vere acute stress likely to compromise CL mainte-

tion.2 Indeed, even when maternal recognition of nance. In these cases, the logical approach is to

pregnancy and maintenance of the CL do fail, the supplement with a suitable progestagen (eg, altreno-

failure is often paired with abnormal conceptus de- gesta) from as soon as CL failure is suspected or

velopment (eg, “small for dates” vesicle) such that it systemic disease is identified, or, in the case of re-

is impossible to determine cause and effect. Nev- peated EED, from before day 6 after ovulation.

ertheless, luteal failure certainly does occur and can, When the incident takes place in early gestation,

for example, be induced by PGF2␣ release from or- supplementation should continue until adequate

gans other than the uterus, for example, in the case maternal progesterone production is certain, that is,

of systemic disease involving endotoxemia.9 More- from some time after day 75 of gestation, by which

over, it appears that the day 18 to day 35 pregnant time the placenta has assumed the role as major

mare is particularly vulnerable to luteolysis because provider of the progestagens required to maintain

the inhibition of endometrial PGF2␣ release that pregnancy. Alternatively, progestagen supplemen-

underlies maternal recognition of pregnancy wanes tation can be discontinued from around day 45 if

after the cessation of conceptus mobility on day 17.5 ultrasonographic examination demonstrates forma-

Indeed, various manipulations (eg, twin aspiration) tion of equine chorionic gonadotropin (eCG)-induced

and hormones (eg, oxytocin, estrogen, human chori- accessory CLs or endogenous plasma progesterone

onic gonadotropin [hCG]) have been shown to elicit concentrations exceed 4 ng/mL. Although proges-

endometrial PGF2␣ secretion during the day 18 to terone supplementation clearly has a role in protect-

day 35 period. Although this PGF2␣ release rarely ing pregnancies threatened by maternal

results in complete luteolysis, it is possible that progesterone deficiency or endotoxin- or inflamma-

there is a mare-specific minimum threshold for pro- tion-induced PGF2␣ release, it is important to sub-

gesterone concentrations below which pregnancy sequently monitor the pregnancy for viability

may be endangered because, for example, the because many will fail despite the progestagen ther-

uterus is no longer able to provide the nutrients apy (suggesting an alternative underlying cause),

332 2012 Ⲑ Vol. 58 Ⲑ AAEP PROCEEDINGS

Orig. Op. OPERATOR: Session PROOF: PE’s: AA’s: COMMENTS ARTNO:

HOW TO MANAGE THE SUBFERTILE MARE

and the progestagens will then prevent the mare 2. Allen WR. Luteal deficiency end embryo mortality in the

returning to estrus. mare. Reprod Dom Anim 2001;36:121–131.

3. Vanderwall D, Squires EL, Brinsko SP, et al. Diagnosis and

An additional treatment that has been shown to management of abnormal embryonic development character-

improve pregnancy rates, presumably by preventing ized by formation of an embryonic vesicle without an embryo

EED, is the administration of a single injection of 20 in mares. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2000;217:58 – 63.

to 40 g buserelinb between days 8 and 12 after 4. Rambags BPB, Krijtenburg PJ, Drie HF, et al. Numerical

ovulation. Although this treatment leads to a chromosomal abnormalities in equine embryos produced in

fairly consistent 5% to 10% increase in pregnancy vivo and in vitro. Mol Reprod Dev 2005;72:77– 87.

5. Stout TAE. The early pregnancy. In: Samper JC, editor.

rates,12 it is not known how it exerts its effects, Equine Breeding Management and Artificial Insemination. St

although it does not appear to be by boosting circu- Louis: WB Saunders; 2008:223–239.

lating progesterone concentrations or preventing lu- 6. Newcombe JR, Cuervo-Aranga J. The effect of time of in-

teolysis.13 The utility of systemic antibiotics to semination with fresh cooled transported semen and natural

counter suspected endometritis in early pregnant mating relative to ovulation on pregnancy and embryo loss

mares is less clear; the use of a 5-day course of rates in the mare. Reprod Dom Anim 2011;46:678 – 681.

7. Lear TL, Lundquist J, Zent WW, et al. Three autosomal

broad-spectrum antibiotics to treat embryo transfer chromosome translocations associated with repeated early

recipients that receive an embryo from an obviously embryonic loss (REEL) in the domestic horse (Equus cabal-

infected donor (ie, very cloudy flush) seems to be a lus). Cytogenet Genome Res 2008;120:117–122.

sensible precautionary measure. On the other 8. Kenney RM, Kent MG, Garcia MC. The use of DNA index

hand, if an early pregnant mare shows ultrasono- and karyotype analyses as adjuncts to the estimation of

graphic indications of endometritis (uterine free fertility in stallions. J Reprod Fertil 1991;(Suppl 44):69 –

75.

fluid or marked edema), antibiotics are generally 9. Daels PF, Stabenfeldt GH, Hughes JP, et al. Evaluation of

ineffective at saving the conceptus and more likely progesterone deficiency as a cause of fetal death in mares

to result in false hope and wasted time. with experimentally induced endotoxemia. Am J Vet Res

1991;52:282–228.

2. Conclusions 10. van Niekerk CH, Morgenthal JC. Fetal loss and the effect of

In summary, although EED is a significant cause of stress on plasma progestagen levels in pregnant Thorough-

loss to the horse breeding industry, it is difficult to bred mares. J Reprod Fertil 1982;(Suppl 32):453– 457.

11. van Niekerk FE, van Niekerk CH. The effect of dietary

predict, may occur without any premonitory signs, protein on reproduction in the mare, VII: embryonic devel-

and is, in many cases, not treatable or preventable. opment, early embryonic death, foetal losses and their rela-

While some methods of reducing specific types of tionship with serum progestagen. J S Afr Vet Assoc 1998;69:

pregnancy loss are now commonplace (eg, early de- 150 –155.

tection and resolution of twin pregnancy, maintain- 12. Newcombe JR, Martinez TA, Peters AR. The effect of the

ing a closed broodmare band, progesterone therapy gonadotropin-releasing hormone analog, buserelin, on preg-

nancy rates in horse and pony mares. Theriogenology 2001;

in cases of suspected failure of pregnancy recogni- 55:1619 –1631.

tion/endotoxemia/severe stress), development of 13. Stout TAE, Tremoleda JL, Knaap J, et al. Mid-diestrus

strategies to combat EED has been slowed by inad- GnRH-analogue administration does not suppress the luteo-

equate understanding of the underlying causes. lytic mechanism in mares Theriogenology 2002;8:567–570.

References and Footnotes

a

1. Allen WR, Brown L, Wright M, et al. Reproductive efficiency Regu-Mate®, Intervet Inc., Millsboro, DE 19966.

b

of Flatrace and National Hunt Thoroughbred mares and stal- Receptal, Intervet/Schering-Plough Animal Health, Milton

lions in England. Equine Vet J 2007;39:438 – 445. Keynes, Bucks MK7 7AJ UK.

AAEP PROCEEDINGS Ⲑ Vol. 58 Ⲑ 2012 333

Orig. Op. OPERATOR: Session PROOF: PE’s: AA’s: COMMENTS ARTNO:

You might also like

- Palos Used Within The Regla Conga and Its Qualities EnglishDocument11 pagesPalos Used Within The Regla Conga and Its Qualities Englishngolo1100% (7)

- Bovine Abortion: General CommentsDocument11 pagesBovine Abortion: General CommentsDio DvmNo ratings yet

- Endometrial Decidualization: The Primary Driver of Pregnancy HealthDocument20 pagesEndometrial Decidualization: The Primary Driver of Pregnancy HealthSherilinne Quiles LópezNo ratings yet

- Immunology of PreeclampsiaDocument13 pagesImmunology of PreeclampsiaRohmantuah_Tra_1826No ratings yet

- Artigo 1 PDFDocument9 pagesArtigo 1 PDFLarissa F SNo ratings yet

- rbjQS9 BREECH PRESENTATION-AN OVERVIEWDocument6 pagesrbjQS9 BREECH PRESENTATION-AN OVERVIEWYosita AuroraNo ratings yet

- Placenta As Witness 07Document15 pagesPlacenta As Witness 07Vetési OrsolyaNo ratings yet

- Etiology, Clinical Manifestations, and Prediction of Placental AbruptionDocument9 pagesEtiology, Clinical Manifestations, and Prediction of Placental AbruptionKadije OanaNo ratings yet

- Etiology of Preeclampsia: An UpdateDocument9 pagesEtiology of Preeclampsia: An UpdateSares DaselvaNo ratings yet

- Differential DiagnosisDocument85 pagesDifferential DiagnosisSayyeda niha AkhtarNo ratings yet

- Proceedings of The 16th Italian Association of Equine Veterinarians CongressDocument6 pagesProceedings of The 16th Italian Association of Equine Veterinarians CongressCabinet VeterinarNo ratings yet

- Fetal and Neonatal Gene Therapy: Benefits and Pitfalls: ReviewDocument6 pagesFetal and Neonatal Gene Therapy: Benefits and Pitfalls: Reviewbhoopendra chauhanNo ratings yet

- A Review On Dystocia in CowsDocument10 pagesA Review On Dystocia in CowsMuhammad JameelNo ratings yet

- Lecture 10 - Repeat BreedingDocument2 pagesLecture 10 - Repeat Breedingkushal NeupaneNo ratings yet

- Abnormal LabourDocument21 pagesAbnormal LabourbetablockersNo ratings yet

- Early Embryonic Mortality Bovine-1Document9 pagesEarly Embryonic Mortality Bovine-1M Huzefa SudaisNo ratings yet

- Etiology of Preeclampsia: An UpdateDocument9 pagesEtiology of Preeclampsia: An UpdateRadi PdNo ratings yet

- Pseudo Pregnancy in DogsDocument11 pagesPseudo Pregnancy in DogsKay ChuaNo ratings yet

- Prematurity, Dysmaturity, Postmaturity PDFDocument8 pagesPrematurity, Dysmaturity, Postmaturity PDFMuhammad YaminNo ratings yet

- The Physiology of Intrapartum Fetal Compromise at Term: Sailesh. Kumar@mater - Uq.edu - AuDocument10 pagesThe Physiology of Intrapartum Fetal Compromise at Term: Sailesh. Kumar@mater - Uq.edu - AuseopyNo ratings yet

- Journal - The Physiology of Intrapartum Fetal Compromise at TermDocument10 pagesJournal - The Physiology of Intrapartum Fetal Compromise at TermbedahfkumiNo ratings yet

- The Placenta: Transcriptional, Epigenetic, and Physiological Integration During DevelopmentDocument10 pagesThe Placenta: Transcriptional, Epigenetic, and Physiological Integration During Developmentpam!!!!No ratings yet

- Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecologic Emergencies 2023Document13 pagesPediatric and Adolescent Gynecologic Emergencies 2023Paola LecuonaNo ratings yet

- Crypt Orchid IsmDocument6 pagesCrypt Orchid IsmJayson Almario AranasNo ratings yet

- Immunology of EclampsiaDocument10 pagesImmunology of EclampsiaTiara AnggianisaNo ratings yet

- BaithaluDocument3 pagesBaithaluRiba FisherNo ratings yet

- Maternal Recognition of Pregnancy'Document9 pagesMaternal Recognition of Pregnancy'Jhoel CbNo ratings yet

- Preterm Birth 1: Epidemiology and Causes of Preterm BirthDocument13 pagesPreterm Birth 1: Epidemiology and Causes of Preterm BirthninachayankNo ratings yet

- Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand - 2011 - TIKKANENDocument9 pagesActa Obstet Gynecol Scand - 2011 - TIKKANENsawsanNo ratings yet

- Pre EclampsiaDocument12 pagesPre EclampsiaJohn Mark PocsidioNo ratings yet

- LactogenesisDocument4 pagesLactogenesisMaría Luz IglesiasNo ratings yet

- Fetal Membrane Healing After Spontaneous and Iatrogenic Membrane Rupture: A Review of Current EvidenceDocument9 pagesFetal Membrane Healing After Spontaneous and Iatrogenic Membrane Rupture: A Review of Current EvidenceNi Wayan Ana PsNo ratings yet

- Antenatal ProfileDocument6 pagesAntenatal ProfileSinchan GhoshNo ratings yet

- Disorders of FoalsDocument96 pagesDisorders of FoalsLaura VillotaNo ratings yet

- Breech Za NigeriaqDocument10 pagesBreech Za NigeriaqRendra Artha Ida BagusNo ratings yet

- 2024 04 23 - PaperDocument20 pages2024 04 23 - PaperdrmanashreesankheNo ratings yet

- Hormonal Causes of RPLDocument9 pagesHormonal Causes of RPLHervi LaksariNo ratings yet

- Intensive Care of The Neonatal FoalDocument32 pagesIntensive Care of The Neonatal FoalAristoteles Esteban Cine VelazquezNo ratings yet

- Molecular Mechanism of ImplantationDocument19 pagesMolecular Mechanism of ImplantationAbunu TilayeNo ratings yet

- Hormonal Causes of Recurrent Pregnancy Loss RPLDocument10 pagesHormonal Causes of Recurrent Pregnancy Loss RPLQONITA PRASTANo ratings yet

- Dekker 2011Document7 pagesDekker 2011tizardwiNo ratings yet

- Abdomina Wall Defects 2Document12 pagesAbdomina Wall Defects 2pamellapesseNo ratings yet

- Joacp 32 153Document7 pagesJoacp 32 153thresh mainNo ratings yet

- The "Vanishing Twin" Syndrome - A Myth or Clinical Reality in The Obstetric Practice?Document3 pagesThe "Vanishing Twin" Syndrome - A Myth or Clinical Reality in The Obstetric Practice?ariniNo ratings yet

- Obgyn SGDocument40 pagesObgyn SGNatalieNo ratings yet

- Early Part ComplicationDocument86 pagesEarly Part ComplicationyewollolijfikreNo ratings yet

- PIIS0002937823001564Document2 pagesPIIS0002937823001564Kalaivathanan VathananNo ratings yet

- Umbilical Cord Prolapse - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfDocument5 pagesUmbilical Cord Prolapse - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelfhermalina sabruNo ratings yet

- GariteDocument3 pagesGariteOkki Masitah Syahfitri NasutionNo ratings yet

- OmphalitisDocument21 pagesOmphalitisdaisukeNo ratings yet

- Pathogenesis of Preeclampsia: The Genetic ComponentDocument9 pagesPathogenesis of Preeclampsia: The Genetic ComponentchandradwtrNo ratings yet

- ProlapseDocument6 pagesProlapseJack GervasNo ratings yet

- EcheverríaSepúlveda2022 Article TheUndescendedTestisInChildrenDocument7 pagesEcheverríaSepúlveda2022 Article TheUndescendedTestisInChildrenMELVIN JOHNNo ratings yet

- IUFDDocument12 pagesIUFDhacker ammerNo ratings yet

- Huppert Z 2008Document7 pagesHuppert Z 2008Alfa FebriandaNo ratings yet

- Pregnancy Losses in MaresDocument29 pagesPregnancy Losses in MaresMittu Kurian100% (1)

- Placental Disease and The Maternal Syndrome of Preeclampsia: Missing Links?Document10 pagesPlacental Disease and The Maternal Syndrome of Preeclampsia: Missing Links?della psNo ratings yet

- Lacto GenesisDocument5 pagesLacto GenesisWISKA VERRENZA -No ratings yet

- Guide to Pediatric Urology and Surgery in Clinical PracticeFrom EverandGuide to Pediatric Urology and Surgery in Clinical PracticeNo ratings yet

- Ovulation Induction and Controlled Ovarian Stimulation: A Practical GuideFrom EverandOvulation Induction and Controlled Ovarian Stimulation: A Practical GuideNo ratings yet

- Equine PlacentaDocument16 pagesEquine PlacentaMittu KurianNo ratings yet

- Dog Behaviour Problems: Why Do They Do It and What Can You Do?Document12 pagesDog Behaviour Problems: Why Do They Do It and What Can You Do?Mittu KurianNo ratings yet

- Intra Partum ConditionsDocument19 pagesIntra Partum ConditionsMittu KurianNo ratings yet

- Impotentia Coeundi and Impotentia Generandi: A Male Infertility (Abstractview - Aspx?Pid 2016-8-2-8)Document15 pagesImpotentia Coeundi and Impotentia Generandi: A Male Infertility (Abstractview - Aspx?Pid 2016-8-2-8)Mittu KurianNo ratings yet

- Pregnancy Losses in MaresDocument29 pagesPregnancy Losses in MaresMittu Kurian100% (1)

- Advances in Equine ReproductionDocument5 pagesAdvances in Equine ReproductionMittu KurianNo ratings yet

- TF SCALE 2022 Application Form (Students)Document4 pagesTF SCALE 2022 Application Form (Students)Crew TabolangNo ratings yet

- ALS Canada Infographic For Inspiration To OthersDocument1 pageALS Canada Infographic For Inspiration To OtherslukeydimatteoNo ratings yet

- Online Healthcare Information Adoption Assessment Using Text Mining TechniquesDocument6 pagesOnline Healthcare Information Adoption Assessment Using Text Mining TechniquesRizqi AUNo ratings yet

- Pcos ApprovedDocument30 pagesPcos ApprovedEsha BhatiaNo ratings yet

- Blyncsy PATROLL Contest WinnerDocument11 pagesBlyncsy PATROLL Contest WinnerJennifer M Gallagher100% (1)

- Surgically-Assisted Rapid Palatal Expansion For Management of Transverse Maxillary DeficiencyDocument3 pagesSurgically-Assisted Rapid Palatal Expansion For Management of Transverse Maxillary DeficiencyDaniela CastilloNo ratings yet

- J Tmaid 2019 101503Document33 pagesJ Tmaid 2019 101503rivanNo ratings yet

- San Francisco Baseball Old Timers Association "From The Dugout" September 2021 EditionDocument6 pagesSan Francisco Baseball Old Timers Association "From The Dugout" September 2021 EditionKris K KimballNo ratings yet

- Lutfia Papita Derizky R. 1610911120024Document17 pagesLutfia Papita Derizky R. 1610911120024lutfia papitaNo ratings yet

- Peptic Ulcer DiseaseDocument22 pagesPeptic Ulcer Diseaserosamundrae100% (1)

- Antituberculars, Antifungals, and AntiviralsDocument44 pagesAntituberculars, Antifungals, and Antiviralsmam2017No ratings yet

- Class Ii Malocclusion: Usman & MehmoodDocument41 pagesClass Ii Malocclusion: Usman & MehmoodmehmudbhattiNo ratings yet

- Appellant's BriefDocument12 pagesAppellant's BriefGinny PañoNo ratings yet

- 28.04.2021 NTEP - RNTCP Dr. Tanuja PattankarDocument29 pages28.04.2021 NTEP - RNTCP Dr. Tanuja PattankarTanuja PattankarNo ratings yet

- S23 - School Mental Health Programs in IndiaDocument22 pagesS23 - School Mental Health Programs in IndiaSukanya KhanikarNo ratings yet

- The Normal Range of Mouth OpeningDocument2 pagesThe Normal Range of Mouth OpeningMarco CarranzaNo ratings yet

- On The Clear Evidence of The Risks To Children From Smartphone and WiFi Radio Frequency Radiation - FinalDocument20 pagesOn The Clear Evidence of The Risks To Children From Smartphone and WiFi Radio Frequency Radiation - FinalNicolas CasanovaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1198743X17305268 MainDocument14 pages1 s2.0 S1198743X17305268 MainAizaz HassanNo ratings yet

- MAPEH 10 Q1 Week 4-HealthDocument10 pagesMAPEH 10 Q1 Week 4-HealthMyla MillapreNo ratings yet

- Temporo Mandibular JointDocument146 pagesTemporo Mandibular Jointdentistpro.orgNo ratings yet

- Manuskrip - Eng (1) BismillahDocument12 pagesManuskrip - Eng (1) BismillahSinta SamhanaNo ratings yet

- Beta 2 MicroglobulinDocument6 pagesBeta 2 MicroglobulinMohamed FaizalNo ratings yet

- Schizophrenia: Psychiatric Nursing Clinical Case PresentationDocument124 pagesSchizophrenia: Psychiatric Nursing Clinical Case PresentationBenedict James BermasNo ratings yet

- Airvo 2 User Manual Ui 185045495Document220 pagesAirvo 2 User Manual Ui 185045495ST HospitalNo ratings yet

- Pain Disability IndexDocument4 pagesPain Disability Indexapi-496718295No ratings yet

- Phase 1Document20 pagesPhase 1divya oNo ratings yet

- ICH Endorsed Guide For MeDRA User 1 - Mar2014Document51 pagesICH Endorsed Guide For MeDRA User 1 - Mar2014Héctor PincheiraNo ratings yet

- Notes On Forensic MedicineDocument59 pagesNotes On Forensic Medicineranjithreddy916gmailNo ratings yet

- Obstetric Case AnalysisDocument2 pagesObstetric Case AnalysisDud AccNo ratings yet