Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Original Investigation: Supplement

Original Investigation: Supplement

Uploaded by

Amanda Juditt Portales AyquipaCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Daily Nursing AssessmentDocument2 pagesDaily Nursing Assessmentkiku_laiNo ratings yet

- Pediatric AssessmentDocument5 pagesPediatric AssessmentmitchNo ratings yet

- Impact of Fiscal Policy On Indian EconomyDocument24 pagesImpact of Fiscal Policy On Indian EconomyAzhar Shokin75% (8)

- BIND Score PDFDocument1 pageBIND Score PDFSindhumv GowdaNo ratings yet

- Laboratory Tests For Various AnemiasDocument1 pageLaboratory Tests For Various AnemiasSassySeanNo ratings yet

- Case Studies On Major Concepts: MetabolismDocument37 pagesCase Studies On Major Concepts: MetabolismJek Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Age Case Presentation BSN 2hDocument40 pagesAge Case Presentation BSN 2hjomariNo ratings yet

- Villacorta - Task 1 - Physical Fitness Test WorksheetDocument1 pageVillacorta - Task 1 - Physical Fitness Test WorksheetRoji VillacortaNo ratings yet

- Malnutrition Ug ManualDocument6 pagesMalnutrition Ug ManualJagdish KalsariyaNo ratings yet

- Pentalaksanaan Penyalahgunaan Benzodiazepin, Miras, Methanol-3Document130 pagesPentalaksanaan Penyalahgunaan Benzodiazepin, Miras, Methanol-3Nia PermanaNo ratings yet

- Assessment Baby BookDocument9 pagesAssessment Baby BookWyeth Earl Padar EndrianoNo ratings yet

- Experiment 5 Data Sheet PDFDocument1 pageExperiment 5 Data Sheet PDFMarc CanonizadoNo ratings yet

- Brief CGA TemplateDocument3 pagesBrief CGA TemplateMagister Keperawatan GerontikNo ratings yet

- Physical AssessmentDocument8 pagesPhysical AssessmentCharlene CrisostomoNo ratings yet

- Excellent Good Fair Poor: Grade LevelsDocument1 pageExcellent Good Fair Poor: Grade LevelsDodalyn MananganNo ratings yet

- Complete Urine Analysis 07-03-2022Document1 pageComplete Urine Analysis 07-03-2022RB STNo ratings yet

- Activity 3 - PARQ&YOU and Fitness TestDocument4 pagesActivity 3 - PARQ&YOU and Fitness TestJohn Alexis CabolisNo ratings yet

- College of Nursing and MidwiferyDocument5 pagesCollege of Nursing and MidwiferyKeneth Dave AglibutNo ratings yet

- Beige Modern Business Organization Chart GraphDocument1 pageBeige Modern Business Organization Chart GraphJoyce Apud EurolfanNo ratings yet

- Isolation and Determination of Gliding Bacteria CytophagaDocument30 pagesIsolation and Determination of Gliding Bacteria CytophagaJoseph Paulo L SilvaNo ratings yet

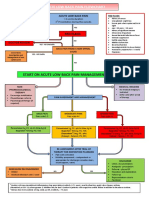

- Acute Low Back Pain Flowchart January 2017Document1 pageAcute Low Back Pain Flowchart January 20171234chocoNo ratings yet

- 3 PRIORITY NURSING CARE PLANS (Intrapartum and Postpartum Periods)Document11 pages3 PRIORITY NURSING CARE PLANS (Intrapartum and Postpartum Periods)Ryan Robert V. VentoleroNo ratings yet

- Urine Routine Examination: B269837 Id No MDocument1 pageUrine Routine Examination: B269837 Id No Mrohanlost20172018No ratings yet

- 7 Physical AssessmentDocument4 pages7 Physical AssessmentMariah Rosette Sison HandomonNo ratings yet

- 7 diabetes WORKSHEETDocument2 pages7 diabetes WORKSHEETLin ChenNo ratings yet

- Apendix 7: Market Segment and Target Customer Market SegmentDocument4 pagesApendix 7: Market Segment and Target Customer Market SegmentVi ChuNo ratings yet

- Cerebrovascular Accident 14Document33 pagesCerebrovascular Accident 14japheth01No ratings yet

- Cerebrovascular Accident: AMA Computer Learning CenterDocument33 pagesCerebrovascular Accident: AMA Computer Learning Centerhermesdave1100% (1)

- Full-Term Pregnancy With Anemia: Arceo, Daniela D. Bicomong, Aedrea Queesha Vhiban VDocument28 pagesFull-Term Pregnancy With Anemia: Arceo, Daniela D. Bicomong, Aedrea Queesha Vhiban VMikes CastroNo ratings yet

- WHO Recommendations PDFDocument1 pageWHO Recommendations PDFlaskarNo ratings yet

- Biology Data: D N A V T N B, BDocument3 pagesBiology Data: D N A V T N B, Bapara_jitNo ratings yet

- Philippine Standard For Quality For Chicken EggsDocument1 pagePhilippine Standard For Quality For Chicken EggsAshley VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- Rubber Property ComparisonDocument1 pageRubber Property ComparisonKrzysztof OkrajekNo ratings yet

- Exposicion TQDocument8 pagesExposicion TQJeisson Fabian Ramirez LopezNo ratings yet

- Exposicion TQDocument8 pagesExposicion TQJeisson Fabian Ramirez LopezNo ratings yet

- Morphology Practical 6Document5 pagesMorphology Practical 6domo- kunNo ratings yet

- AKI - Antibiotic DosingDocument22 pagesAKI - Antibiotic DosingSadiq AchakzaiNo ratings yet

- Gastroenteritis': Dr. Yanga'S Colleges, IncDocument9 pagesGastroenteritis': Dr. Yanga'S Colleges, IncZyren FuentabellaNo ratings yet

- Fluids and ElectrolytesDocument12 pagesFluids and ElectrolytesasdasdasdNo ratings yet

- Cancer Case StudyDocument23 pagesCancer Case StudyJaymica Laggui DacquilNo ratings yet

- Usg 4 Dimensi DR DahonoDocument3 pagesUsg 4 Dimensi DR DahonowmwyusufNo ratings yet

- The Atlantic - July, August 2018Document124 pagesThe Atlantic - July, August 2018Anthony ThomasNo ratings yet

- PHA6112 Lec - Module 3 - Carbohydrates - Data SheetsDocument5 pagesPHA6112 Lec - Module 3 - Carbohydrates - Data SheetsPompeyo BarrogaNo ratings yet

- NAMIA - Reading AssignmentDocument22 pagesNAMIA - Reading AssignmentFeb NamiaNo ratings yet

- Physical Assessment Table: Body Parts Assessed Technique Normal Findings Actual Findings Remarks General SurveyDocument11 pagesPhysical Assessment Table: Body Parts Assessed Technique Normal Findings Actual Findings Remarks General SurveyMia PascualNo ratings yet

- Discussion Practical 3 MicrobeDocument2 pagesDiscussion Practical 3 Microbedomo- kunNo ratings yet

- Medical FormDocument2 pagesMedical Formmomococomomo1000No ratings yet

- Hypoxic Ishemic EncephalopathyDocument4 pagesHypoxic Ishemic Encephalopathydred macaraegNo ratings yet

- Triase Nusantara SehatDocument14 pagesTriase Nusantara SehatWidia Nurul AnisaNo ratings yet

- Idoc - Pub 5 PT Med Surg Brain SheetDocument2 pagesIdoc - Pub 5 PT Med Surg Brain Sheetrazric0809No ratings yet

- Physical AssessmentDocument33 pagesPhysical AssessmentSherry GonzalesNo ratings yet

- 5 - Fluid and ElectrolyteDocument37 pages5 - Fluid and ElectrolyteJek Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Head To Toe Assessment: ST NDDocument3 pagesHead To Toe Assessment: ST NDErick SumicadNo ratings yet

- Sample Id:E Table Illustrating Properties of Minerals Under PPL and XPL in Thin Sections Under Petrographic MicroscopeDocument1 pageSample Id:E Table Illustrating Properties of Minerals Under PPL and XPL in Thin Sections Under Petrographic MicroscopeChristina BagiliyeNo ratings yet

- A Study On Retailer's Perception and Behaviour Towards Amul Fresh Product Division (Responses)Document10 pagesA Study On Retailer's Perception and Behaviour Towards Amul Fresh Product Division (Responses)ds wwNo ratings yet

- Eremblen Toroljuuleliitn ZaawarDocument2 pagesEremblen Toroljuuleliitn ZaawarОюунгэрэл Бархас-ОдNo ratings yet

- Legal Med DeathDocument5 pagesLegal Med DeathYOKESHWARAN DHANDAPANINo ratings yet

- Rubric Wellness Dance 1Document2 pagesRubric Wellness Dance 1Alexa GuidoNo ratings yet

- Acute Low Back Pain Flowchart March 2016Document1 pageAcute Low Back Pain Flowchart March 2016Alfiya HasnaNo ratings yet

- Guru Prasad DubeyDocument2 pagesGuru Prasad DubeyGowtham SivamNo ratings yet

- Sterling Scholar EssaysDocument5 pagesSterling Scholar Essaysapi-255099497No ratings yet

- Rule 112Document645 pagesRule 112Nemei SantiagoNo ratings yet

- Pratibha Revankar PDFDocument2 pagesPratibha Revankar PDFrajasekharsnetxcellNo ratings yet

- 2015 Anesthesia Cases' DiscussionDocument301 pages2015 Anesthesia Cases' Discussionsri09111996No ratings yet

- HHDocument226 pagesHHAstitva ChauhanNo ratings yet

- Lesson 4 - Planning A Written TestDocument20 pagesLesson 4 - Planning A Written TestAndrea Lastaman100% (2)

- Lesson PlanDocument2 pagesLesson Planapi-189222578No ratings yet

- Chapter 16 "How Well Am I Doing?" - Financial Statement AnalysisDocument134 pagesChapter 16 "How Well Am I Doing?" - Financial Statement AnalysisTyra Joyce RevadaviaNo ratings yet

- American Atheist Magazine April 1980Document48 pagesAmerican Atheist Magazine April 1980American Atheists, Inc.No ratings yet

- SSP 186 - The CAN Data BusDocument29 pagesSSP 186 - The CAN Data Busmas20012No ratings yet

- MS DiscussionDocument1 pageMS DiscussionAllyssa Mae DelaRosa UchihaNo ratings yet

- Motion To Reconsider Decision of 4 Discovery MotionsDocument9 pagesMotion To Reconsider Decision of 4 Discovery MotionsLee PerryNo ratings yet

- Caltex Vs PalomarDocument1 pageCaltex Vs PalomarNMNGNo ratings yet

- 5.0 Advanced Troubleshooting PDFDocument1 page5.0 Advanced Troubleshooting PDFAponteTrujilloNo ratings yet

- Comm Studies Ia Expository Lol-1Document4 pagesComm Studies Ia Expository Lol-1BrittanyNo ratings yet

- Malaysia Lead Sex ActiverDocument3 pagesMalaysia Lead Sex ActiverTetuan Ahmad Razali and Partners100% (1)

- Engl 595 Huyssen After The Great DivideDocument3 pagesEngl 595 Huyssen After The Great DivideAdam StrantzNo ratings yet

- Lista Verbos Irregulares (Ingles)Document5 pagesLista Verbos Irregulares (Ingles)luis_javier92100% (2)

- The Hand Maids Tails NotesDocument13 pagesThe Hand Maids Tails NotesgraumanmosheNo ratings yet

- Certificates For Project ReportDocument11 pagesCertificates For Project ReportFiroz KachhiNo ratings yet

- Stats CH 6 Final ReviewDocument3 pagesStats CH 6 Final ReviewIkequan ScottNo ratings yet

- Assignment On Business Statistics (SUBMITION DATE 10/12/2013)Document2 pagesAssignment On Business Statistics (SUBMITION DATE 10/12/2013)Negero ArarsoNo ratings yet

- Assignment Marketing StrategyDocument11 pagesAssignment Marketing StrategyAkshay IratkarNo ratings yet

- Genitive Case Evidence T3Document2 pagesGenitive Case Evidence T3Juan Jose Arcila AlvarezNo ratings yet

- No Mind-Map: Map / Pic Pedalogical Strategies Skills / HOT / Kbat Teaching Aids Noble Values Thinking SkillsDocument2 pagesNo Mind-Map: Map / Pic Pedalogical Strategies Skills / HOT / Kbat Teaching Aids Noble Values Thinking Skillscyberbat2008No ratings yet

- EstimationDocument32 pagesEstimationJester RubiteNo ratings yet

- Phys 111 - Lecture NotesDocument96 pagesPhys 111 - Lecture Notesosmankamara557No ratings yet

- JNTU ANATHAPUR B.TECH Mechanical Engineering R09 SyllabusDocument147 pagesJNTU ANATHAPUR B.TECH Mechanical Engineering R09 Syllabuspavankumar72No ratings yet

Original Investigation: Supplement

Original Investigation: Supplement

Uploaded by

Amanda Juditt Portales AyquipaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Original Investigation: Supplement

Original Investigation: Supplement

Uploaded by

Amanda Juditt Portales AyquipaCopyright:

Available Formats

Intermittent vs Continuous Androgen Deprivation for Prostate Cancer Original Investigation Research

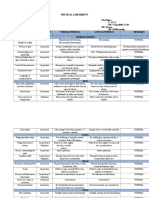

Table 2. Risk of Bias Assessmenta

Blinding of Blinding Incomplete Summary

Sequence Allocation Participants Outcome Outcome Selective Within

Source Outcome Generation Concealment and Personnel Assessment Data Reporting Studies

Hering et al,30 Overall survival Low Unclear Low Low Low Low Unclear

2000 Quality of life NA NA NA NA NA

Time to castration Low Unclear Low Low Unclear

resistance

de Leval et al,29 Overall survival Unclear Unclear NA NA NA NA NA

2002 Quality of life NA NA NA NA NA

Time to castration Low Low Low Low Unclear

resistance

Schasfoort Overall survival Unclear Low Low Low Unclear High High

et al,40 2003 Quality of life High High Low High High

Time to clinical High High Unclear High High

progression

Yamanaka et al,45 Overall survival Unclear Unclear Low Low High High High

2005 Quality of life Unclear Unclear High High High

Biochemical– Low Unclear High High High

relapse-free survival

Tunn et al,41 Overall survival Unclear Unclear NA NA NA NA NA

2007 Quality of life Unclear Unclear Unclear High High

Androgen- Low Low Unclear Low Unclear

independent

progression

Miller et al,35 Overall survival Unclear Unclear Low Low Unclear Low Unclear

2007 Quality of life Unclear Unclear Unclear High High

Time to clinical Unclear Unclear Unclear Low Unclear

and/or biochemical

progression

Irani et al,31 2008 Overall survival Unclear Unclear Low Low Low Low Unclear

Quality of lifeb Unclear Unclear Low Low Unclear

Calais da Silva Overall survival Unclear Unclear Low Low High Low High

et al,27 2009 Quality of life Unclear Unclear High Unclear High

Time to subjective or Unclear Unclear High Low High

objective progression

Crook et al,13 Overall survivalb Low Low Low Low Low Low Low

2012 Quality of life High High Unclear High High

Salonen et al,38,39 Overall survival Low Unclear Low Low Low Low Unclear

2012 Quality of life High High Low Low High

Time to progression Low Low Low Low Unclear

Mottet et al,36 Overall survivalb Unclear Low Low Low High Low High

2012 Quality of life High High Unclear Unclear High

Organ et al,37 Overall survival Unclear Unclear Low Low Low Low Unclear

2013 Quality of lifeb Unclear Unclear High High High

Hussain et al,14 Overall survivalb Unclear Unclear Low Low High Low High

2013 Quality of lifeb Unclear Unclear High Low High

Calais da Silva Overall survivalb Unclear Unclear Low Low Low Low Unclear

et al,15 2013 Quality of life Unclear Unclear Unclear Unclear

Verhagen et al,44Overall survival Unclear Unclear Low Low Unclear High High

2013 Quality of life High High Unclear Low High

Time to PSA Low Low Unclear Unclear Unclear

progression

Abbreviations: NA, not available (ie, the outcome was not evaluated in the study); PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

a

The risk of bias was assessed with the Cochrane Collaboration’s Risk of Bias Tool by 2 reviewers independently for overall survival, quality of life, and the primary

outcome of each of the selected studies.

b

This outcome was the primary outcome of the study.

mation to enable calculation of HRs.36,37 We observed no dif- Quality of Life

ference between intermittent and continuous therapy based Quality of life was assessed by patient self-administered

on pooled results of those 8 trials (5352 patients, HR for death, questionnaires in 13 trials,§ but the disparity of instruments

1.02; 95% CI, 0.93-1.11; I2 = 23%) (Figure 2A). The upper bound- used and the unavailability of quantitative data prevented

ary of the 95% CI was less than the prespecified 1.15 limit, sup- conducting a meta-analysis. Different versions of the

porting our hypothesis that intermittent therapy is not infe- EORTC (European Organization for Research and Treatment

rior to continuous therapy. The small number of trials limited of Cancer) QLQ-C30 questionnaire were used in 9 trials,{

the robustness of sensitivity and subgroup analyses (see eTable including a prostate cancer–specific complementary

1 in the Supplement). A subgroup analysis of metastatic cas- module in 8 of them. 13,15,27,31,36,37,40,44 One trial did not

tration-resistant prostate cancer vs hormone-sensitive pros- mention the instr ument used, 3 5 and the remaining

tate cancer was also performed a posteriori. This analysis did §References 13-15, 27, 31, 32, 35-38, 40, 42, 44

not affect the study results. {References 13, 15, 27, 31, 36, 37, 40, 42, 44

jamaoncology.com (Reprinted) JAMA Oncology December 2015 Volume 1, Number 9 1265

Copyright 2015 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 07/17/2020

Research Original Investigation Intermittent vs Continuous Androgen Deprivation for Prostate Cancer

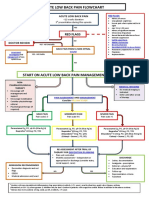

Figure 2. Pooled Survival and Progression Results

A Overall survival

Source Log HR (SE) HR (95% CI) Favors IAD Favors CAD Weight, %

Irani et al,31 2008 0.5128 (0.3950) 1.67 (0.77-3.62) 1.2

Calais da Silva et al,27 2009 0.0392 (0.0870) 1.04 (0.88-1.23) 17.7

Crook et al,13 2012 0.0198 (0.0871) 1.02 (0.86-1.21) 17.6

Mottet et al,36 2012 0.2070 (0.2069) 1.23 (0.82-1.85) 4.2

Hussain et al,14 2013 0.0953 (0.0641) 1.10 (0.97-1.25) 25.9

Organ et al,37 2012 0.3293 (0.3800) 1.39 (0.66-2.93) 1.3

Salonen et al,38,39 2008 –0.1393 (0.1008) 0.87 (0.71-1.06) 14.3

Calais da Silva et al,15 2013 –0.1054 (0.0863) 0.90 (0.76-1.07) 17.9

Total 1.02 (0.93-1.11) 100

0.2 0.5 1 2 5

HR (95% CI)

B Cancer-specific survival

Source Log HR (SE) HR (95% CI) Favors IAD Favors CAD Weight, %

Irani et al,31 2008 0.5108 (0.5004) 1.67 (0.63-4.44) 2.5

Calais da Silva et al,27 2009 0.1275 (0.1707) 1.14 (0.81-1.59) 18.8

Salonen et al,38,39 2008 –0.1570 (0.1304) 0.85 (0.66-1.10) 29.3

Crook et al,13 2012 0.1655 (0.1382) 1.18 (0.90-1.55) 26.7

Calais da Silva et al,15 2013 –0.0726 (0.1523) 0.93 (0.69-1.25) 22.8

Total 1.02 (0.87-1.19) 100

0.2 0.5 1 2 5

HR (95% CI)

C Time to progression

Source Log HR (SE) HR (95% CI) Favors IAD Favors CAD Weight, %

Miller et al,35 2007 –0.3711 (0.1356) 0.69 (0.53-0.90) 20.9

Verhagen et al,44 2013 0.0953 (0.2925) 1.10 (0.62-1.95) 10.6

Calais da Silva et al,27 2009 0.2070 (0.1318) 1.23 (0.95-1.59) 21.2

Crook et al,13 2012 –0.2231 (0.0905) 0.80 (0.67-0.96) 24.5

Calais da Silva et al,15 2013 0.1484 (0.1128) 1.16 (0.93-1.45) 22.8

Total 0.96 (0.76-1.21) 100

0.2 0.5 1 2 5

HR (95% CI)

D Progression-free survival

Hazard ratios (HRs) were either taken

Source Log HR (SE) HR (95% CI) Favors IAD Favors CAD Weight, % directly from the individual studies or

Irani et al,31 2008 –0.0954 (0.2508) 0.91 (0.56-1.49) 5.0 were calculated based on published

Mottet et al,36 2012 –0.3147 (0.1731) 0.73 (0.52-1.02) 10.5 data. The analyses, using the inverse

Salonen et al,38,39 2008 –0.0769 (0.0908) 0.93 (0.78-1.11) 38.0 variance method, were performed

with Review Manager software,

Calais da Silva et al,15 2013 0.0100 (0.0820) 1.01 (0.86-1.19) 46.6

version 5.2 (Cochrane Collaboration)

Total 0.94 (0.84-1.05) 100

using random effect models. CAD

0.2 0.5 1 2 5 indicates continuous androgen

HR (95% CI) deprivation; IAD, intermittent

androgen deprivation.

3 trials used other questionnaires.14,32,38 Most of the trials Secondary Outcomes

assessed quality of life according to a fixed schedule regard- Cancer-Specific Survival

less of treatment intervals. Only 2 trials31,38 evaluated qual- There was no significant difference between the 2 treatment

ity of life with respect to treatment and off-treatment peri- groups with respect to cancer-specific survival based on pooled

ods. Two trials reported a better overall quality of life with results from 5 trials13,15,27,31,39 (3613 patients, HR for death, 1.02;

intermittent therapy,35,42 and 3 trials did not observe any 95% CI, 0.87-1.19; I2 = 14%) (Figure 2B). The results were con-

difference between the 2 methods of administration.36,37,40 sistent in all subgroup and sensitivity analyses (see eTable 2

The other 7 trials observed an increase in quality of life with in the Supplement).

intermittent therapy but only in certain domains. The most

Progression-Free Survival

frequently detected differences related to physical and

Twelve trials reported data on disease progression,# of which

sexual functioning. However, 3 of those 7 trials also noted

5 provided HRs.13,15,27,31,39 Hazard ratios from 3 other trials were

an improvement of some quality-of-life criteria in the

continuous-therapy group.27,31,44 #References 13, 15, 27, 29-31, 35, 36, 39, 40, 42, 44

1266 JAMA Oncology December 2015 Volume 1, Number 9 (Reprinted) jamaoncology.com

Copyright 2015 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 07/17/2020

Intermittent vs Continuous Androgen Deprivation for Prostate Cancer Original Investigation Research

calculated.35,36,44 Progression of the disease was presented as

time to progression in some trials and as progression-free sur- Discussion

vival in other trials, thus precluding combination of these data.

We observed no difference in terms of disease progression be- In this systematic review, we did not observe a difference in

tween intermittent and continuous androgen deprivation overall survival for intermittent compared with continuous an-

therapy based on pooled results of 5 trials for time to progres- drogen deprivation therapy for the treatment of patients with

sion (3523 patients, HR for progression, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.76- prostate cancer. Since the observed upper boundary of the 95%

1.21; I2 = 75%) (Figure 2C) and 4 trials for progression-free sur- CI of the HR for death was lower than the prespecified mar-

vival (1774 patients, HR for progression, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.84- gin, our findings support our hypothesis that intermittent

1.05; I2 = 0%) (Figure 2D). Inferences from sensitivity and therapy is not inferior to continuous therapy. Overall, there were

subgroup analyses are weak considering the small number of minimal differences in patients’ self-reported quality of life be-

trials (eTables 3 and 4 in the Supplement). tween the 2 interventions. However, an improvement in some

quality-of-life criteria was observed with intermittent therapy,

Time to Castration Resistance mostly in relation with physical and sexual functioning. Fi-

Of the 4 trials that evaluated time to castration resis- nally, the use of intermittent androgen deprivation was not as-

tance,13,29,30,42 2 observed a statistically significant differ- sociated with increased time to castration resistance.

ence in favor of intermittent therapy.13,29 The difference was

not significant in the 2 remaining trials. Only 1 trial provided Findings in Relation With Current Knowledge

an HR,13 and the 3 other trials did not provide enough infor- Our results for the overall survival analysis are in accordance

mation to allow HR calculation, thus precluding a pooled with those of 2 large recent randomized clinical trials13,15 but

analysis. in contradiction with 1 other14; all 3 studies were included in

our systematic review and meta-analysis. However, besides the

Adverse Effects disease stage of the study population, important methodologi-

Twelve trials reported data on drug-related adverse effects cal limitations of the contrasting study14 in regard to calcula-

(eTable 5 in the Supplement),** but none evaluated them sys- tion of the noninferiority margin and sample size, number of

tematically. All trials presented adverse effects as the num- participants excluded after randomization, and high inci-

ber of patients in each group who experienced the adverse dence of withdrawal from therapy may explain the discrep-

event at least once during the whole follow-up period. There ancies. Two recent meta-analyses also observed no differ-

was no significant difference between groups for all reported ence in overall survival between intermittent and continuous

adverse effects (eTable 6 in the Supplement). However, as a therapy.46,47 However, these systematic reviews had signifi-

whole, pooled point estimates favored reduced drug-related cant methodological weaknesses, including a limited search

adverse effects with intermittent androgen deprivation. strategy, lack of exhaustiveness, questionable methodolo-

gies and analyses, and no consideration of recent large trials.

Skeletal-Related Events Moreover, inadequate methods of HR calculation were used

Only 1 trial reported only 1 skeletal-related event: fracture.39 for some of the included trials. Furthermore, time to progres-

In this trial, 6.9% vs 5.4% of patients had fracture(s) in the in- sion and progression-free survival data were inappropriately

termittent and the continuous therapy group, respectively. This combined in analyses, thus seriously limiting the validity of

difference was not significant. the results. Regarding time to castration resistance, although

previous trials performed on tumor models8,9 reported an im-

Additional Outcomes portant increase with alternation of testosterone deprivation

Information was available for off-treatment intervals and tes- and replacement compared with definitive castration, those

tosterone levels for the intermittent therapy group in 13†† and findings did not seem to translate into a significant clinical ben-

9‡‡ trials, respectively. However, most of them reported very efit as observed in our systematic review.

few data on those 2 outcomes. Moreover, there was a wide vari- The fact that most trials used a fixed schedule, regardless

ability in the type of data reported. Therefore, we could not of treatment and off-treatment intervals, may explain why no

outline any trend between trials except that most of them ob- major difference was observed between the 2 treatment regi-

served that the duration of off-treatment periods decreased mens in quality-of-life outcomes. Testosterone levels de-

from cycle to cycle. crease rapidly following the introduction of antiandrogen de-

privation therapy and take several months to return to normal

Publication Bias and Quality of Evidence levels once the medication administration is stopped. As long

Visual inspection of a funnel plot of the intervention esti- as patients undergoing intermittent therapy have low testos-

mate vs the standard error for trials that provided an HR for terone levels, we can expect that they will experience the same

overall survival did not reveal evidence of publication bias. Ac- adverse effects as patients undergoing continuous therapy, and

cording to the GRADE methodology,26 the overall strength of that these adverse effects will have a comparable impact on

evidence for overall survival was considered to be moderate. their quality of life. Off-treatment periods in these trials may

not have been long enough to allow a sufficient increase in tes-

**References 13-15, 27, 29, 30, 35, 36, 39, 40, 42, 44

††References 13, 15, 27, 29, 30, 34-37, 39, 40, 42-45 tosterone levels, and this may explain the comparable ad-

‡‡References 13, 27, 30, 31, 34, 36, 37, 39, 43 verse events and quality of life observed. Finally, the lack of a

jamaoncology.com (Reprinted) JAMA Oncology December 2015 Volume 1, Number 9 1267

Copyright 2015 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 07/17/2020

Research Original Investigation Intermittent vs Continuous Androgen Deprivation for Prostate Cancer

systematic method of evaluation of adverse effects in the in- ing pooled analyses. In addition, the high risk of bias and the

cluded trials could mainly explain the statistical heteroge- low methodological quality of the included trials reduced the

neity observed in most pooled estimates and could also partly strength of evidence for our primary outcome measure of over-

explain why we observed no significant difference between the all survival. A high risk of bias was associated with quality-of-

2 interventions. In addition, all trials presented adverse ef- life assessment, which is a highly subjective outcome, consid-

fects as cumulative incidences, which may have contributed ering that participants were not blinded to the treatment

to the underestimation of the effect of the treatment sched- assigned in more than one-third of the trials and that blind-

ule since, as noted, we expect that patients with low testos- ing was not mentioned in the remaining trials. Three trials failed

terone levels have similar adverse effects regardless of the in- to publish their final results in peer-reviewed journals, which

tervention received. increases concern related to internal validity or systematic bias.

Finally, we could not perform all of the planned subgroup and

Strengths and Limitations sensitivity analyses owing to limited data availability.

Our systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted and

reported following established methodological guidelines.16,17

We used an a priori defined protocol and carried out an exten-

sive literature search using multiple databases, including both

Conclusions

scientific and gray literature. We analyzed overall survival In our systematic review, we observed that intermittent an-

using a noninferiority design with a prespecified threshold of drogen deprivation for the treatment of prostate cancer is not

statistical significance allowing us to draw firm conclusions. inferior to continuous therapy with respect to overall sur-

We also examined the effect of the intervention on several vival. No major difference in quality of life was observed be-

secondary end points allowing a comprehensive review of the tween groups, although some criteria seemed improved in the

current knowledge on the effect of intermittent androgen intermittent groups in relation with physical and sexual func-

deprivation. tioning. Intermittent androgen deprivation can be consid-

Our systematic review was limited by the available data, ered as an alternative therapeutic option in patients with pros-

which were sometimes insufficient to conduct pooled analy- tate cancer. However, the high risk of bias observed in some

ses or to include all trials in these analyses. Nevertheless, the trials, the unclear optimal approach to the duration of treat-

pooled estimates of most analyses regrouped a large number ment and off-treatment periods and criteria on which it should

of patients (5352 patients for overall survival) showing a po- be based, and the unknown magnitude of effect according to

tentially high accuracy with narrow CIs. The majority of trials the disease stage warrant further research before it becomes

reported quality of life in a descriptive fashion thus preclud- the mandatory standard of care.

ARTICLE INFORMATION Drafting of the manuscript: Magnan, Zarychanski, Practices Unit of the CHU de Québec Research

Accepted for Publication: June 27, 2015. Turgeon. Center, Université Laval, Québec City, Québec,

Critical revision of the manuscript for important Canada. They were not compensated for their

Published Online: September 17, 2015. intellectual content: Magnan, Zarychanski, Pilote, contributions beyond their normal employment

doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.2895. Bernier, Shemilt, Vigneault, Fradet, Turgeon. compensation.

Author Affiliations: Division of Radiation Statistical analysis: Magnan, Zarychanski, Shemilt,

Oncology, Department of Medicine, CHU de Fradet, Turgeon. REFERENCES

Québec, Université Laval, Québec City, Québec, Obtained funding: Turgeon. 1. Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, et al;

Canada (Magnan, Pilote, Bernier, Vigneault); Administrative, technical, or material support: International Agency for Research on Cancer.

Department of Internal Medicine, Sections of Shemilt. GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, 2013, Cancer Incidence and

Hematology/Medical Oncology and Critical Care, Study supervision: Magnan, Vigneault, Turgeon. Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 11. http:

University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr Vigneault has //globocan.iarc.fr. Accessed February 27, 2014.

Canada (Zarychanski); Department of Haematology received honoraria for consultation for Abvie,

and Medical Oncology, Cancercare Manitoba, 2. Mohler JL, Kantoff PW, Armstrong AJ, et al;

Sanofie, Jansen, Astellas, Peladin, and Amgen. No National comprehensive cancer network. Prostate

Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada (Zarychanski); CHU de other disclosures are reported.

Québec Research Center, Université Laval, Québec cancer, version 1.2014. J Natl Compr Canc Netw.

City, Québec, Canada (Shemilt, Vigneault, Fradet, Funding/Support: Dr Magnan is a recipient of a 2013;11(12):1471-1479.

Turgeon); Division of Urology, Department of Resident Physician Health Research Career Training 3. Green HJ, Pakenham KI, Headley BC, et al.

Surgery, CHU de Québec, Université Laval, Québec Grant from the Fonds de Recherche du Québec– Quality of life compared during pharmacological

City, Québec, Canada (Fradet); Division of Critical Santé (FRQS). Drs Fradet and Turgeon are treatments and clinical monitoring for non-localized

Care Medicine, Department of Anesthesiology and recipients of a Clinician-Scientist Award from the prostate cancer: a randomized controlled trial. BJU

Critical Care Medicine, CHU de Québec, Université FRQS. Int. 2004;93(7):975-979.

Laval, Québec City, Québec, Canada (Turgeon). Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The supporting 4. Herr HW, Kornblith AB, Ofman U. A comparison

Author Contributions: Drs Magnan and Turgeon institution had no role in the design and conduct of of the quality of life of patients with metastatic

had full access to all the data in the study and take the study; collection, management, analysis, and prostate cancer who received or did not receive

responsibility for the integrity of the data and the interpretation of the data; preparation, review or hormonal therapy. Cancer. 1993;71(3)(suppl):1143-

accuracy of the data analysis. approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit 1150.

Study concept and design: Magnan, Vigneault, the manuscript for publication.

5. Herr HW, O’Sullivan M. Quality of life of

Turgeon. Additional Contributions: We are thankful to asymptomatic men with nonmetastatic prostate

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Caroline Léger, PhD, for editing assistance, and cancer on androgen deprivation therapy. J Urol.

Magnan, Zarychanski, Pilote, Bernier, Shemilt, Brice Lionel Batomen Kuimi, MSc, for statistical 2000;163(6):1743-1746.

Fradet, Turgeon. analysis. Dr Léger and Mr Kuimi are both affiliated

with the Population Health and Optimal Health

1268 JAMA Oncology December 2015 Volume 1, Number 9 (Reprinted) jamaoncology.com

Copyright 2015 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 07/17/2020

You might also like

- Daily Nursing AssessmentDocument2 pagesDaily Nursing Assessmentkiku_laiNo ratings yet

- Pediatric AssessmentDocument5 pagesPediatric AssessmentmitchNo ratings yet

- Impact of Fiscal Policy On Indian EconomyDocument24 pagesImpact of Fiscal Policy On Indian EconomyAzhar Shokin75% (8)

- BIND Score PDFDocument1 pageBIND Score PDFSindhumv GowdaNo ratings yet

- Laboratory Tests For Various AnemiasDocument1 pageLaboratory Tests For Various AnemiasSassySeanNo ratings yet

- Case Studies On Major Concepts: MetabolismDocument37 pagesCase Studies On Major Concepts: MetabolismJek Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Age Case Presentation BSN 2hDocument40 pagesAge Case Presentation BSN 2hjomariNo ratings yet

- Villacorta - Task 1 - Physical Fitness Test WorksheetDocument1 pageVillacorta - Task 1 - Physical Fitness Test WorksheetRoji VillacortaNo ratings yet

- Malnutrition Ug ManualDocument6 pagesMalnutrition Ug ManualJagdish KalsariyaNo ratings yet

- Pentalaksanaan Penyalahgunaan Benzodiazepin, Miras, Methanol-3Document130 pagesPentalaksanaan Penyalahgunaan Benzodiazepin, Miras, Methanol-3Nia PermanaNo ratings yet

- Assessment Baby BookDocument9 pagesAssessment Baby BookWyeth Earl Padar EndrianoNo ratings yet

- Experiment 5 Data Sheet PDFDocument1 pageExperiment 5 Data Sheet PDFMarc CanonizadoNo ratings yet

- Brief CGA TemplateDocument3 pagesBrief CGA TemplateMagister Keperawatan GerontikNo ratings yet

- Physical AssessmentDocument8 pagesPhysical AssessmentCharlene CrisostomoNo ratings yet

- Excellent Good Fair Poor: Grade LevelsDocument1 pageExcellent Good Fair Poor: Grade LevelsDodalyn MananganNo ratings yet

- Complete Urine Analysis 07-03-2022Document1 pageComplete Urine Analysis 07-03-2022RB STNo ratings yet

- Activity 3 - PARQ&YOU and Fitness TestDocument4 pagesActivity 3 - PARQ&YOU and Fitness TestJohn Alexis CabolisNo ratings yet

- College of Nursing and MidwiferyDocument5 pagesCollege of Nursing and MidwiferyKeneth Dave AglibutNo ratings yet

- Beige Modern Business Organization Chart GraphDocument1 pageBeige Modern Business Organization Chart GraphJoyce Apud EurolfanNo ratings yet

- Isolation and Determination of Gliding Bacteria CytophagaDocument30 pagesIsolation and Determination of Gliding Bacteria CytophagaJoseph Paulo L SilvaNo ratings yet

- Acute Low Back Pain Flowchart January 2017Document1 pageAcute Low Back Pain Flowchart January 20171234chocoNo ratings yet

- 3 PRIORITY NURSING CARE PLANS (Intrapartum and Postpartum Periods)Document11 pages3 PRIORITY NURSING CARE PLANS (Intrapartum and Postpartum Periods)Ryan Robert V. VentoleroNo ratings yet

- Urine Routine Examination: B269837 Id No MDocument1 pageUrine Routine Examination: B269837 Id No Mrohanlost20172018No ratings yet

- 7 Physical AssessmentDocument4 pages7 Physical AssessmentMariah Rosette Sison HandomonNo ratings yet

- 7 diabetes WORKSHEETDocument2 pages7 diabetes WORKSHEETLin ChenNo ratings yet

- Apendix 7: Market Segment and Target Customer Market SegmentDocument4 pagesApendix 7: Market Segment and Target Customer Market SegmentVi ChuNo ratings yet

- Cerebrovascular Accident 14Document33 pagesCerebrovascular Accident 14japheth01No ratings yet

- Cerebrovascular Accident: AMA Computer Learning CenterDocument33 pagesCerebrovascular Accident: AMA Computer Learning Centerhermesdave1100% (1)

- Full-Term Pregnancy With Anemia: Arceo, Daniela D. Bicomong, Aedrea Queesha Vhiban VDocument28 pagesFull-Term Pregnancy With Anemia: Arceo, Daniela D. Bicomong, Aedrea Queesha Vhiban VMikes CastroNo ratings yet

- WHO Recommendations PDFDocument1 pageWHO Recommendations PDFlaskarNo ratings yet

- Biology Data: D N A V T N B, BDocument3 pagesBiology Data: D N A V T N B, Bapara_jitNo ratings yet

- Philippine Standard For Quality For Chicken EggsDocument1 pagePhilippine Standard For Quality For Chicken EggsAshley VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- Rubber Property ComparisonDocument1 pageRubber Property ComparisonKrzysztof OkrajekNo ratings yet

- Exposicion TQDocument8 pagesExposicion TQJeisson Fabian Ramirez LopezNo ratings yet

- Exposicion TQDocument8 pagesExposicion TQJeisson Fabian Ramirez LopezNo ratings yet

- Morphology Practical 6Document5 pagesMorphology Practical 6domo- kunNo ratings yet

- AKI - Antibiotic DosingDocument22 pagesAKI - Antibiotic DosingSadiq AchakzaiNo ratings yet

- Gastroenteritis': Dr. Yanga'S Colleges, IncDocument9 pagesGastroenteritis': Dr. Yanga'S Colleges, IncZyren FuentabellaNo ratings yet

- Fluids and ElectrolytesDocument12 pagesFluids and ElectrolytesasdasdasdNo ratings yet

- Cancer Case StudyDocument23 pagesCancer Case StudyJaymica Laggui DacquilNo ratings yet

- Usg 4 Dimensi DR DahonoDocument3 pagesUsg 4 Dimensi DR DahonowmwyusufNo ratings yet

- The Atlantic - July, August 2018Document124 pagesThe Atlantic - July, August 2018Anthony ThomasNo ratings yet

- PHA6112 Lec - Module 3 - Carbohydrates - Data SheetsDocument5 pagesPHA6112 Lec - Module 3 - Carbohydrates - Data SheetsPompeyo BarrogaNo ratings yet

- NAMIA - Reading AssignmentDocument22 pagesNAMIA - Reading AssignmentFeb NamiaNo ratings yet

- Physical Assessment Table: Body Parts Assessed Technique Normal Findings Actual Findings Remarks General SurveyDocument11 pagesPhysical Assessment Table: Body Parts Assessed Technique Normal Findings Actual Findings Remarks General SurveyMia PascualNo ratings yet

- Discussion Practical 3 MicrobeDocument2 pagesDiscussion Practical 3 Microbedomo- kunNo ratings yet

- Medical FormDocument2 pagesMedical Formmomococomomo1000No ratings yet

- Hypoxic Ishemic EncephalopathyDocument4 pagesHypoxic Ishemic Encephalopathydred macaraegNo ratings yet

- Triase Nusantara SehatDocument14 pagesTriase Nusantara SehatWidia Nurul AnisaNo ratings yet

- Idoc - Pub 5 PT Med Surg Brain SheetDocument2 pagesIdoc - Pub 5 PT Med Surg Brain Sheetrazric0809No ratings yet

- Physical AssessmentDocument33 pagesPhysical AssessmentSherry GonzalesNo ratings yet

- 5 - Fluid and ElectrolyteDocument37 pages5 - Fluid and ElectrolyteJek Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Head To Toe Assessment: ST NDDocument3 pagesHead To Toe Assessment: ST NDErick SumicadNo ratings yet

- Sample Id:E Table Illustrating Properties of Minerals Under PPL and XPL in Thin Sections Under Petrographic MicroscopeDocument1 pageSample Id:E Table Illustrating Properties of Minerals Under PPL and XPL in Thin Sections Under Petrographic MicroscopeChristina BagiliyeNo ratings yet

- A Study On Retailer's Perception and Behaviour Towards Amul Fresh Product Division (Responses)Document10 pagesA Study On Retailer's Perception and Behaviour Towards Amul Fresh Product Division (Responses)ds wwNo ratings yet

- Eremblen Toroljuuleliitn ZaawarDocument2 pagesEremblen Toroljuuleliitn ZaawarОюунгэрэл Бархас-ОдNo ratings yet

- Legal Med DeathDocument5 pagesLegal Med DeathYOKESHWARAN DHANDAPANINo ratings yet

- Rubric Wellness Dance 1Document2 pagesRubric Wellness Dance 1Alexa GuidoNo ratings yet

- Acute Low Back Pain Flowchart March 2016Document1 pageAcute Low Back Pain Flowchart March 2016Alfiya HasnaNo ratings yet

- Guru Prasad DubeyDocument2 pagesGuru Prasad DubeyGowtham SivamNo ratings yet

- Sterling Scholar EssaysDocument5 pagesSterling Scholar Essaysapi-255099497No ratings yet

- Rule 112Document645 pagesRule 112Nemei SantiagoNo ratings yet

- Pratibha Revankar PDFDocument2 pagesPratibha Revankar PDFrajasekharsnetxcellNo ratings yet

- 2015 Anesthesia Cases' DiscussionDocument301 pages2015 Anesthesia Cases' Discussionsri09111996No ratings yet

- HHDocument226 pagesHHAstitva ChauhanNo ratings yet

- Lesson 4 - Planning A Written TestDocument20 pagesLesson 4 - Planning A Written TestAndrea Lastaman100% (2)

- Lesson PlanDocument2 pagesLesson Planapi-189222578No ratings yet

- Chapter 16 "How Well Am I Doing?" - Financial Statement AnalysisDocument134 pagesChapter 16 "How Well Am I Doing?" - Financial Statement AnalysisTyra Joyce RevadaviaNo ratings yet

- American Atheist Magazine April 1980Document48 pagesAmerican Atheist Magazine April 1980American Atheists, Inc.No ratings yet

- SSP 186 - The CAN Data BusDocument29 pagesSSP 186 - The CAN Data Busmas20012No ratings yet

- MS DiscussionDocument1 pageMS DiscussionAllyssa Mae DelaRosa UchihaNo ratings yet

- Motion To Reconsider Decision of 4 Discovery MotionsDocument9 pagesMotion To Reconsider Decision of 4 Discovery MotionsLee PerryNo ratings yet

- Caltex Vs PalomarDocument1 pageCaltex Vs PalomarNMNGNo ratings yet

- 5.0 Advanced Troubleshooting PDFDocument1 page5.0 Advanced Troubleshooting PDFAponteTrujilloNo ratings yet

- Comm Studies Ia Expository Lol-1Document4 pagesComm Studies Ia Expository Lol-1BrittanyNo ratings yet

- Malaysia Lead Sex ActiverDocument3 pagesMalaysia Lead Sex ActiverTetuan Ahmad Razali and Partners100% (1)

- Engl 595 Huyssen After The Great DivideDocument3 pagesEngl 595 Huyssen After The Great DivideAdam StrantzNo ratings yet

- Lista Verbos Irregulares (Ingles)Document5 pagesLista Verbos Irregulares (Ingles)luis_javier92100% (2)

- The Hand Maids Tails NotesDocument13 pagesThe Hand Maids Tails NotesgraumanmosheNo ratings yet

- Certificates For Project ReportDocument11 pagesCertificates For Project ReportFiroz KachhiNo ratings yet

- Stats CH 6 Final ReviewDocument3 pagesStats CH 6 Final ReviewIkequan ScottNo ratings yet

- Assignment On Business Statistics (SUBMITION DATE 10/12/2013)Document2 pagesAssignment On Business Statistics (SUBMITION DATE 10/12/2013)Negero ArarsoNo ratings yet

- Assignment Marketing StrategyDocument11 pagesAssignment Marketing StrategyAkshay IratkarNo ratings yet

- Genitive Case Evidence T3Document2 pagesGenitive Case Evidence T3Juan Jose Arcila AlvarezNo ratings yet

- No Mind-Map: Map / Pic Pedalogical Strategies Skills / HOT / Kbat Teaching Aids Noble Values Thinking SkillsDocument2 pagesNo Mind-Map: Map / Pic Pedalogical Strategies Skills / HOT / Kbat Teaching Aids Noble Values Thinking Skillscyberbat2008No ratings yet

- EstimationDocument32 pagesEstimationJester RubiteNo ratings yet

- Phys 111 - Lecture NotesDocument96 pagesPhys 111 - Lecture Notesosmankamara557No ratings yet

- JNTU ANATHAPUR B.TECH Mechanical Engineering R09 SyllabusDocument147 pagesJNTU ANATHAPUR B.TECH Mechanical Engineering R09 Syllabuspavankumar72No ratings yet