Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Medicine: Will COVID-19 Be Evidence-Based Medicine's Nemesis?

Medicine: Will COVID-19 Be Evidence-Based Medicine's Nemesis?

Uploaded by

Daniela Mădălina GhețuOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Medicine: Will COVID-19 Be Evidence-Based Medicine's Nemesis?

Medicine: Will COVID-19 Be Evidence-Based Medicine's Nemesis?

Uploaded by

Daniela Mădălina GhețuCopyright:

Available Formats

PLOS MEDICINE

EDITORIAL

Will COVID-19 be evidence-based medicine’s

nemesis?

Trisha Greenhalgh ID*

Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom

* trish.greenhalgh@phc.ox.ac.uk

Once defined in rhetorical but ultimately meaningless terms as “the conscientious, judicious

and explicit use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual

patients” [1], evidence-based medicine rests on certain philosophical assumptions: a singular

truth, ascertainable through empirical enquiry; a linear logic of causality in which interven-

tions have particular effect sizes; rigour defined primarily in methodological terms (especially,

a hierarchy of preferred study designs and tools for detecting bias); and a deconstructive

approach to problem-solving (the evidence base is built by answering focused questions, typi-

cally framed as ‘PICO’—population-intervention-comparison-outcome) [2].

a1111111111 The trouble with pandemics is that these assumptions rarely hold. A pandemic-sized prob-

a1111111111 lem can be framed and contested in multiple ways. Some research questions around COVID-

a1111111111

19, most notably relating to drugs and vaccines, are amenable to randomised controlled trials

a1111111111

a1111111111 (and where such trials were possible, they were established with impressive speed and effi-

ciency [3, 4]). But many knowledge gaps are broader and cannot be reduced to PICO-style

questions. Were care home deaths avoidable [5]? Why did the global supply chain for personal

protective equipment break down [6]? What role does health system resilience play in control-

ling the pandemic [7]? And so on.

OPEN ACCESS Against these—and other—wider questions, the neat simplicity of a controlled, interven-

Citation: Greenhalgh T (2020) Will COVID-19 be tion-on versus intervention-off experiment designed to produce a definitive (i.e. statistically

evidence-based medicine’s nemesis? PLoS Med significant and widely generalisable) answer to a focused question rings hollow. In particular,

17(6): e1003266. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. upstream preventive public health interventions aimed at supporting widespread and sus-

pmed.1003266

tained behaviour change across an entire population (as opposed to testing the impact of a

Published: June 30, 2020 short-term behaviour change in a select sample) rarely lend themselves to such a design [8, 9].

Copyright: This is an open access article, free of all When implementing population-wide public health interventions—whether conventional

copyright, and may be freely reproduced, measures such as diet or exercise, or COVID-19 related ones such as handwashing, social dis-

distributed, transmitted, modified, built upon, or tancing and face coverings—we must not only persuade individuals to change their behavior

otherwise used by anyone for any lawful purpose. but also adapt the environment to make such changes easier to make and sustain [10–12].

The work is made available under the Creative

Population-wide public health efforts are typically iterative, locally-grown and path-depen-

Commons CC0 public domain dedication.

dent, and they have an established methodology for rapid evaluation and adaptation [9]. But

Funding: TG’s research is funded from the evidence-based medicine has tended to classify such designs as “low methodological quality”

following sources: National Institute for Health

[13]. Whilst this has been recognised as a problem in public health practice for some time [11],

Research (BRC-1215-20008), UK Research and

Innovation (COVID-19 Emergency Fund), and the inadequacy of the dominant paradigm has suddenly become mission-critical.

Wellcome Trust (WT104830MA). The funders had Whilst evidence-based medicine recognises that study designs must reflect the nature of

no role in study design, data collection and question (randomized trials, for example, are preferred only for therapy questions [13]), even

analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the senior scientists sometimes over-apply its hierarchy of evidence. An interdisciplinary group of

manuscript.

scholars from the UK’s prestigious Royal Society recently reviewed the use of face masks by

Competing interests: The authors have declared the general public, drawing on evidence from laboratory science, mathematical modelling and

that no competing interests exist.

PLOS Medicine | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003266 June 30, 2020 1/4

PLOS MEDICINE

policy studies [14]. The report was criticised by epidemiologists for being “non-systematic”

and for recommending policy action in the absence of a quantitative estimate of effect size

from robust randomized controlled trials [15].

Such criticisms appear to make two questionable assumptions: first, that the precise quanti-

fication of impact from this kind of intervention is both possible and desirable, and second,

that unless we have randomized trial evidence, we should do nothing.

It is surely time to turn to a more fit-for-purpose scientific paradigm. Complex adaptive

systems theory proposes that precise quantification of particular cause-effect relationships is

both impossible (because such relationships are not constant and cannot be meaningfully iso-

lated) and unnecessary (because what matters is what emerges in a particular real-world situa-

tion). This paradigm proposes that where multiple factors are interacting in dynamic and

unpredictable ways, naturalistic methods and rapid-cycle evaluation are the preferred study

design. The 20th-century logic of evidence-based medicine, in which scientists pursued the

goals of certainty, predictability and linear causality, remains useful in some circumstances

(for example, the drug and vaccine trials referred to above). But at a population and system

level, we need to embrace 21st-century epistemology and methods to study how best to cope

with uncertainty, unpredictability and non-linear causality [16].

In a complex system, the question driving scientific inquiry is not “what is the effect size

and is it statistically significant once other variables have been controlled for?” but “does this

intervention contribute, along with other factors, to a desirable outcome?”. Multiple interven-

tions might each contribute to an overall beneficial effect through heterogeneous effects on

disparate causal pathways, even though none would have a statistically significant impact on

any predefined variable [11]. To illuminate such influences, we need to apply research designs

that foreground dynamic interactions and emergence. These include in-depth, mixed-method

case studies (primary research) and narrative reviews (secondary research) that tease out inter-

connections and highlight generative causality across the system [16, 17].

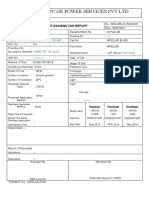

Table 1 lists some philosophical contrasts between the evidence-based medicine and com-

plex-systems paradigms. Ogilvie et al have argued that rather than pitting these two paradigms

Table 1. Evidence-based medicine versus complex systems research paradigms. Adapted under Creative Commons licence from Greenhalgh and Papoutsi [16].

Evidence-based medicine paradigm Complex systems paradigm

Perspective on Singular, independent of the observer, ascertainable through Multiple, influenced by mode of inquiry and perspective taken

scientific truth empirical inquiry

Goal of research Establishing the truth; finding more or less universal and Exploring tensions; generating insights and wisdom; exposing multiple

generalisable solutions to well-defined problems perspectives; viewing complex systems as moving targets

Assumed model of Linear, cause-and-effect causality (perhaps incorporating Emergent causality: multiple interacting influences account for a particular

causality mediators and moderators) outcome but none can be said to have a fixed ‘effect size’

Typical format of “What is the effect size of the intervention on the predefined “What combination of influences has generated this phenomenon? What

research question outcome, and is it statistically significant?” does the intervention of interest contribute? What happens to the system

and its actors if we intervene in a particular way? What are the unintended

consequences elsewhere in the system?”

Mode of Attempt to represent science in one authoritative voice Attempt to illustrate the plurality of voices inherent in the research and

representation phenomena under study

Good research is Methodological ‘rigour’, i.e. strict application of structured and Strong theory, flexible methods, pragmatic adaptation to emerging

characterised by standardised design, conventional approaches to generalisability circumstances, contribution to generative learning and theoretical

and validity transferability

Purpose of theorising Disjunctive: simplification and abstraction; breaking problems Conjunctive: drawing parts of the problem together to produce a rich,

down into analysable parts nuanced picture of what is going on and why

Approach to data Research should continue until data collection is complete Data will never be complete or perfect; decisions often need to be made

despite incomplete or contested data

Analytic focus Dualisms: A versus B; influence of X on Y Dualities: inter-relationships and dynamic tensions between A, B, C and

other emergent aspects

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003266.t001

PLOS Medicine | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003266 June 30, 2020 2/4

PLOS MEDICINE

Fig 1. Ogilvie et al’s model of two complementary modes of evidence generation: evidence-based practice and practice-based

evidence. Reproduced under CC-BY-4.0 licence from authors’ original [9].

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003266.g001

against one another, they should be brought together [9]. As illustrated in (Fig 1), these authors

depict randomized trials (what they call the “evidence-based practice pathway”) and natural

experiments (the “practice-based evidence pathway”) in a complementary and recursive rela-

tionship rather than a hierarchical one. They propose that “. . .intervention studies [e.g. trials]

should focus on reducing critical uncertainties, that non-randomised study designs should be

embraced rather than tolerated and that a more nuanced approach to appraising the utility of

diverse types of evidence is required.” (page 203) [9].

In the current fast-moving pandemic, where the cost of inaction is counted in the grim

mortality figures announced daily, implementing new policy interventions in the absence of

randomized trial evidence has become both a scientific and moral imperative. Whilst it is hard

to predict anything in real time, history will one day tell us whether adherence to “evidence-

based practice” helped or hindered the public health response to Covid-19—or whether an

apparent slackening of standards to accommodate “practice-based evidence” was ultimately a

more effective strategy.

References

1. Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JM, Haynes RB, Richardson WS. Evidence based medicine: what it

is and what it isn’t. Bmj. 1996; 312(7023):71–2. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71 PMID:

8555924

2. Greenhalgh T. How to Read a Paper: The basics of evidence-based medicine and healthcare ( 6th edi-

tion). Oxford: John Wiley and Sons Ltd; 2019.

3. Baden LR, Rubin EJ. Covid-19—the search for effective therapy. New Engl J Med. 2020; 382:1851–2.

https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMe2005477 PMID: 32187463

4. Lurie N, Saville M, Hatchett R, Halton J. Developing Covid-19 vaccines at pandemic speed. New Engl J

Med. 2020; 382:1969–73. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2005630 PMID: 32227757

5. Gordon AL, Goodman C, Achterberg W, Barker RO, Burns E, Hanratty B, et al. COVID in Care Homes

—Challenges and Dilemmas in Healthcare Delivery. Age and Ageing. 2020.

6. Armani AM, Hurt DE, Hwang D, McCarthy MC, Scholtz A. Low-tech solutions for the COVID-19 supply

chain crisis. Nature Reviews Materials. 2020:1–4.

7. Legido-Quigley H, Asgari N, Teo YY, Leung GM, Oshitani H, Fukuda K, et al. Are high-performing

health systems resilient against the COVID-19 epidemic? The Lancet. 2020; 395(10227):848–50.

PLOS Medicine | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003266 June 30, 2020 3/4

PLOS MEDICINE

8. West R, Michie S, Rubin GJ, Amlôt R. Applying principles of behaviour change to reduce SARS-CoV-2

transmission. Nature Human Behaviour. 2020:1–9.

9. Ogilvie D, Adams J, Bauman A, Gregg EW, Panter J, Siegel KR, et al. Using natural experimental stud-

ies to guide public health action: turning the evidence-based medicine paradigm on its head. J Epide-

miol Community Health. 2020; 74(2):203–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2019-213085 PMID:

31744848

10. Glass TA, McAtee MJ. Behavioral science at the crossroads in public health: extending horizons, envi-

sioning the future. Social science & medicine. 2006; 62(7):1650–71.

11. Rutter H, Savona N, Glonti K, Bibby J, Cummins S, Finegood DT, et al. The need for a complex systems

model of evidence for public health. The Lancet. 2017; 390(10112):2602–4.

12. Jefferson T, Del Mar CB, Dooley L, Ferroni E, Al-Ansary LA, Bawazeer GA, et al. Physical interventions

to interrupt or reduce the spread of respiratory viruses. Cochrane database of systematic reviews.

2011;(7).

13. Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE: an emerging

consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Bmj. 2008; 336(7650):924–

6. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD PMID: 18436948

14. DELVE. Face Masks for the General Public. London: Royal Society DELVE (Data Evaluation and

Learning for Viral Epidemics) initiative; 2020. Accessed 4th May 2020 at https://rs-delve.github.io/

reports.html.

15. Science Media Centre. Expert reaction to review of evidence on face masks and face coverings by the

Royal Society DELVE Initiative. London: Science Media Centre; 2020 (4th May). Accessed 7th May

2020 at https://www.sciencemediacentre.org/expert-reaction-to-review-of-evidence-on-face-masks-

and-face-coverings-by-the-royal-society-delve-initiative/.

16. Greenhalgh T, Papoutsi C. Studying complexity in health services research: desperately seeking an

overdue paradigm shift. BioMed Central; 2018. p. 95.

17. Greenhalgh T, Thorne S, Malterud K. Time to challenge the spurious hierarchy of systematic over narra-

tive reviews? European journal of clinical investigation. 2018; 48(6):e12931. https://doi.org/10.1111/eci.

12931 PMID: 29578574

PLOS Medicine | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003266 June 30, 2020 4/4

You might also like

- Delhi Exporter ListDocument41 pagesDelhi Exporter ListAnshu GuptaNo ratings yet

- Observational Study - WikipediaDocument4 pagesObservational Study - WikipediaDiana GhiusNo ratings yet

- Benjamin Chung2017Document16 pagesBenjamin Chung2017734500203No ratings yet

- Cohort and Casecontrol StudiesDocument2 pagesCohort and Casecontrol StudiesCitiNo ratings yet

- Planetary Health As A Laboratory For Enhanced Evid - 2019 - The Lancet PlanetaryDocument3 pagesPlanetary Health As A Laboratory For Enhanced Evid - 2019 - The Lancet PlanetaryCarol Mora PlaNo ratings yet

- kwy280Document6 pageskwy280ThormmmNo ratings yet

- What Matters Most Quantifying An Epidemiology of ConsequenceDocument7 pagesWhat Matters Most Quantifying An Epidemiology of ConsequenceRicardo SantanaNo ratings yet

- Van KesselDocument9 pagesVan KesselJorge Fernández BaluarteNo ratings yet

- Study Designs 5Document51 pagesStudy Designs 5Seare TekesteNo ratings yet

- From Bench To WhereDocument5 pagesFrom Bench To WhereLuminita SimionNo ratings yet

- Types of Medical ResearchDocument31 pagesTypes of Medical ResearchTurkay Yildiz BayrakNo ratings yet

- Why and How Epidemiologists Should Use Mixed MethodsDocument11 pagesWhy and How Epidemiologists Should Use Mixed MethodsAndre LanzerNo ratings yet

- Process-Based Functional Analysis Can Help Behavioral Science Step Up ToDocument19 pagesProcess-Based Functional Analysis Can Help Behavioral Science Step Up ToGabriel TalaskNo ratings yet

- FDA - Pharma R&D - Taxonomy Studies and TrialsDocument4 pagesFDA - Pharma R&D - Taxonomy Studies and TrialsketamacualpaNo ratings yet

- Study Designs 5Document51 pagesStudy Designs 5hlufnegaNo ratings yet

- Converging On Bladder Health Through Design ThinkiDocument17 pagesConverging On Bladder Health Through Design ThinkiNur Faidhi NasrudinNo ratings yet

- Mejora de Validez en Investig Del Tratamiento de ComorbilidadDocument11 pagesMejora de Validez en Investig Del Tratamiento de ComorbilidadDanitza YhovannaNo ratings yet

- Highs and Lows of Research Exploring Value in Research Cases - Oxford HandbooksDocument29 pagesHighs and Lows of Research Exploring Value in Research Cases - Oxford HandbooksJulianaCerqueiraCésarNo ratings yet

- 2004 Beyond RCT - AjphDocument6 pages2004 Beyond RCT - AjphSamuel Andrés AriasNo ratings yet

- 1 - Outcomes ResearchDocument12 pages1 - Outcomes ResearchMauricio Ruiz MoralesNo ratings yet

- Sessler, Methodology 1, Sources of ErrorDocument9 pagesSessler, Methodology 1, Sources of ErrorMarcia Alvarez ZeballosNo ratings yet

- Trust and Public Health Emergency Events A Mixedmethods Systematic ReviewDocument21 pagesTrust and Public Health Emergency Events A Mixedmethods Systematic ReviewPutriNo ratings yet

- HardonDocument6 pagesHardonayakha twalaNo ratings yet

- Causal InferenceDocument11 pagesCausal Inferencejohn949No ratings yet

- WHAT Counts As Evidence: Brought To You by Universite de Montreal - Unauthenticated - Downloaded 02/23/23 06:26 PM UTCDocument16 pagesWHAT Counts As Evidence: Brought To You by Universite de Montreal - Unauthenticated - Downloaded 02/23/23 06:26 PM UTCAbelardo LeónNo ratings yet

- Observational Studies: Why Are They So ImportantDocument2 pagesObservational Studies: Why Are They So ImportantAndre LanzerNo ratings yet

- Transdisciplinary Approaches Enhance The Production of Translational KnowledgeDocument12 pagesTransdisciplinary Approaches Enhance The Production of Translational KnowledgereneNo ratings yet

- 10 Mertz ClusterRCThandhygieneDocument8 pages10 Mertz ClusterRCThandhygieneEddyOmburahNo ratings yet

- McKinlay - Public Health Matters 2000 PDFDocument9 pagesMcKinlay - Public Health Matters 2000 PDFanitaNo ratings yet

- Theoretical Model of Critical Issues in Informed Consent in HIV Vaccine TrialsDocument12 pagesTheoretical Model of Critical Issues in Informed Consent in HIV Vaccine TrialsSamNo ratings yet

- The Economics of Reproducibility in Preclinical Research: Leonard P. Freedman, Iain M. Cockburn, Timothy S. SimcoeDocument9 pagesThe Economics of Reproducibility in Preclinical Research: Leonard P. Freedman, Iain M. Cockburn, Timothy S. SimcoecipinaNo ratings yet

- Systems Science Methods in Public HealthDocument26 pagesSystems Science Methods in Public HealthKaris Lee del CastilloNo ratings yet

- Galea 2012 Causal Thinking and Complex System Approaches in EpidemiologyDocument10 pagesGalea 2012 Causal Thinking and Complex System Approaches in EpidemiologyPrevencion AtencionNo ratings yet

- W1R4 Causal Criteria 1Document34 pagesW1R4 Causal Criteria 1Sauharda DhakalNo ratings yet

- Fogg and Gross 2000 - Threats To Validity in Randomized Clinical TrialsDocument11 pagesFogg and Gross 2000 - Threats To Validity in Randomized Clinical TrialsChris LeeNo ratings yet

- HHS Public AccessDocument20 pagesHHS Public AccessdajcNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1755436517300294 MainDocument3 pages1 s2.0 S1755436517300294 MainBravishhNo ratings yet

- 22 CH 5Document26 pages22 CH 5Isaac AffamNo ratings yet

- Reporting Results of Research Involving Human Subjects - An Ethical ObligationDocument3 pagesReporting Results of Research Involving Human Subjects - An Ethical ObligationAlenka TabakovićNo ratings yet

- Review ArticleDocument9 pagesReview Articlesaasha1753No ratings yet

- Key Concepts of Clinical Trials A Narrative ReviewDocument12 pagesKey Concepts of Clinical Trials A Narrative ReviewLaura CampañaNo ratings yet

- Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand - 2018 - Bhide - A Simplified Guide To Randomized Controlled TrialsDocument8 pagesActa Obstet Gynecol Scand - 2018 - Bhide - A Simplified Guide To Randomized Controlled Trialscogiw65923No ratings yet

- Evidence Based Policymaking A CritiqueDocument16 pagesEvidence Based Policymaking A CritiqueMaria SilviaNo ratings yet

- Clinical Research and Medical CareDocument7 pagesClinical Research and Medical CareNino MdinaradzeNo ratings yet

- Why All Randomised Controlled Trials Produce Biased ResultsDocument11 pagesWhy All Randomised Controlled Trials Produce Biased ResultsSimona BugaciuNo ratings yet

- Assessing Evidence Assessing EvidenceDocument9 pagesAssessing Evidence Assessing Evidencetulus setiawanNo ratings yet

- Taking STOX: Developing A Cross Disciplinary Methodology For Systematic Reviews of Research On The Built Environment and The Health of The PublicDocument8 pagesTaking STOX: Developing A Cross Disciplinary Methodology For Systematic Reviews of Research On The Built Environment and The Health of The Publicujangketul62No ratings yet

- Meilia2020 Article AReviewOfCausalInferenceInFore PDFDocument8 pagesMeilia2020 Article AReviewOfCausalInferenceInFore PDFuchumuhammadNo ratings yet

- Meilia2020 Article AReviewOfCausalInferenceInFore PDFDocument8 pagesMeilia2020 Article AReviewOfCausalInferenceInFore PDFuchumuhammadNo ratings yet

- Framing A Research Question and Generating A Research HypothesisDocument6 pagesFraming A Research Question and Generating A Research HypothesisOluwajuwon AdenugbaNo ratings yet

- A Short Introduction To Epidemiology 2nd EdDocument152 pagesA Short Introduction To Epidemiology 2nd EdTatiana SirbuNo ratings yet

- Descriptive Study DesignsDocument53 pagesDescriptive Study DesignsErmiasNo ratings yet

- 10.Q. Workshop: Evaluating Policy Using Natural Experiments and Quasi-Experimental MethodsDocument2 pages10.Q. Workshop: Evaluating Policy Using Natural Experiments and Quasi-Experimental MethodsAnandyagunaNo ratings yet

- Bioethics - 2023 - Heynemann - Therapeutic Misunderstandings in Modern ResearchDocument15 pagesBioethics - 2023 - Heynemann - Therapeutic Misunderstandings in Modern ResearchPaulo Afonso do PradoNo ratings yet

- Mental Health Services Research Methodology 2002Document8 pagesMental Health Services Research Methodology 2002Kats CoelloNo ratings yet

- MEDECIELO MELO - Chapter 5 SummaryDocument12 pagesMEDECIELO MELO - Chapter 5 SummaryMelo MedecieloNo ratings yet

- The Appraisal of Public Health InterventionsDocument6 pagesThe Appraisal of Public Health InterventionsindrasariyuliantiNo ratings yet

- Research Study DesignsDocument12 pagesResearch Study DesignsDr Deepthi GillaNo ratings yet

- Health Expectations - 2017 - Rojas García - Impact and Experiences of Delayed Discharge A Mixed Studies Systematic ReviewDocument16 pagesHealth Expectations - 2017 - Rojas García - Impact and Experiences of Delayed Discharge A Mixed Studies Systematic ReviewGabriela ObonNo ratings yet

- Environmental EpidemiologyDocument5 pagesEnvironmental EpidemiologyKarthik VkNo ratings yet

- TS Bio Rad Cell - Gene - Therapy Ebook AC V4 D2 FINALDocument8 pagesTS Bio Rad Cell - Gene - Therapy Ebook AC V4 D2 FINALDaniela Mădălina GhețuNo ratings yet

- Metaphase Preparation From Adherent CellsDocument2 pagesMetaphase Preparation From Adherent CellsDaniela Mădălina GhețuNo ratings yet

- Covid Is An Endothelial Disease 2020 SeptDocument7 pagesCovid Is An Endothelial Disease 2020 SeptDaniela Mădălina GhețuNo ratings yet

- A Comparative Study of The Capacity of MesenchymalDocument20 pagesA Comparative Study of The Capacity of MesenchymalDaniela Mădălina GhețuNo ratings yet

- Multifactorial Experimental Designto Optimizethe Anti-Inflammatoryand Proangiogenic Potentialof Mesenchymal Stem Cell SpheroidsDocument13 pagesMultifactorial Experimental Designto Optimizethe Anti-Inflammatoryand Proangiogenic Potentialof Mesenchymal Stem Cell SpheroidsDaniela Mădălina GhețuNo ratings yet

- MicrofluidicaDocument17 pagesMicrofluidicaDaniela Mădălina GhețuNo ratings yet

- Apoptosis and NecrosisDocument8 pagesApoptosis and NecrosisDaniela Mădălina GhețuNo ratings yet

- Advances in Multicellular Spheroids FormationDocument15 pagesAdvances in Multicellular Spheroids FormationDaniela Mădălina GhețuNo ratings yet

- Human Adipose-Derived Stem CellsDocument10 pagesHuman Adipose-Derived Stem CellsDaniela Mădălina GhețuNo ratings yet

- The Use of Telomerized Cells For Tissue Engineering: AnalysisDocument2 pagesThe Use of Telomerized Cells For Tissue Engineering: AnalysisDaniela Mădălina GhețuNo ratings yet

- Epi ParkinsonDocument12 pagesEpi ParkinsonDaniela Mădălina GhețuNo ratings yet

- Genetics of DiabetesDocument10 pagesGenetics of DiabetesDaniela Mădălina GhețuNo ratings yet

- Diabetes Mellitus Genetics PDFDocument13 pagesDiabetes Mellitus Genetics PDFDaniela Mădălina GhețuNo ratings yet

- Primemotiontraining Beeptest GuideDocument6 pagesPrimemotiontraining Beeptest GuideCristian NechitaNo ratings yet

- Review Text of Indonesian MovieDocument8 pagesReview Text of Indonesian Movieadel fashaNo ratings yet

- Big 5Document16 pagesBig 5Anubhav Pratap SinghNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Accountancy, Business, and Management 2 Activity 2Document1 pageFundamentals of Accountancy, Business, and Management 2 Activity 2Joseph CincoNo ratings yet

- Junior Achievement Communication AuditDocument27 pagesJunior Achievement Communication AuditJaren ScottNo ratings yet

- Letter of Request Service Credits Brigada 2022Document2 pagesLetter of Request Service Credits Brigada 2022KEICHIE QUIMCONo ratings yet

- Osgi - Core 5.0.0 PFDDocument408 pagesOsgi - Core 5.0.0 PFDCarlos Salinas GancedoNo ratings yet

- Forfaiting:: Trade Finance FactoringDocument9 pagesForfaiting:: Trade Finance FactoringR.v. NaveenanNo ratings yet

- Database Development ProcessDocument8 pagesDatabase Development ProcessdeezNo ratings yet

- Kill This LuvDocument4 pagesKill This LuvplumribsNo ratings yet

- Mekapay Business ModelDocument38 pagesMekapay Business ModelHerbertNo ratings yet

- Enable or Disable Macros in Office FilesDocument4 pagesEnable or Disable Macros in Office Filesmili_ccNo ratings yet

- The International Successful School Principalship Project - Dr. David GurrDocument12 pagesThe International Successful School Principalship Project - Dr. David Gurryoyo hamNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Ergonomics PDFDocument6 pagesResearch Paper On Ergonomics PDFefdwvgt4100% (3)

- NTPC Ge Power Services PVT LTD: Liquid Penetrant Examination ReportDocument2 pagesNTPC Ge Power Services PVT LTD: Liquid Penetrant Examination ReportBalkishan DyavanapellyNo ratings yet

- Mini-Link Craft Basic SetupDocument15 pagesMini-Link Craft Basic Setupamadou abdoulkaderNo ratings yet

- Law Abiding Citizen (2009) BluRayExt HighDocument25 pagesLaw Abiding Citizen (2009) BluRayExt HighdamiloakinyemiNo ratings yet

- RIEMANN INTEGRATION TabrejDocument48 pagesRIEMANN INTEGRATION TabrejPriti Prasanna SamalNo ratings yet

- A Detailed Lesson Plan in LiteratureDocument8 pagesA Detailed Lesson Plan in LiteratureLevi Rose FajardoNo ratings yet

- Ewa Bukowska, Secret Teaching in Poland in The Years 1939 To 1945Document3 pagesEwa Bukowska, Secret Teaching in Poland in The Years 1939 To 1945kesleycdsNo ratings yet

- Question Bank SUBJECT: GSM (06EC844) Part-A: Unit 1 (GSM Architecture and Interfaces)Document6 pagesQuestion Bank SUBJECT: GSM (06EC844) Part-A: Unit 1 (GSM Architecture and Interfaces)Santhosh VisweswarappaNo ratings yet

- Aspire Budget 2.8 PDFDocument274 pagesAspire Budget 2.8 PDFLucas DinizNo ratings yet

- Investing in India's Green Hydrogen SectorDocument7 pagesInvesting in India's Green Hydrogen SectorAshwaniNo ratings yet

- MSDS Khai Báo PDFDocument8 pagesMSDS Khai Báo PDFViệtDũngNo ratings yet

- Printable Company Profile SampleDocument10 pagesPrintable Company Profile SampleanskhanNo ratings yet

- Farinas Vs Exec SecretaryDocument10 pagesFarinas Vs Exec SecretarySharmila AbieraNo ratings yet

- Macedonians in Contemporary Australia. Najdovski 1997Document229 pagesMacedonians in Contemporary Australia. Najdovski 1997Basil ChulevNo ratings yet

- Scholarship FormDocument3 pagesScholarship FormHammad Yousaf100% (6)

- MIP 2021 (Budget Proposal)Document215 pagesMIP 2021 (Budget Proposal)Yanny ManggugubatNo ratings yet