Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Oral History at A Distance:: Conducting Remote Interviews Webinar

Oral History at A Distance:: Conducting Remote Interviews Webinar

Uploaded by

mobcranbCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Speech Recognition, Digitization, GenerationDocument12 pagesSpeech Recognition, Digitization, GenerationSireesha Tekuru100% (6)

- Ec Axial Fan - Axiblade: Nominal DataDocument1 pageEc Axial Fan - Axiblade: Nominal DataAykut BacakNo ratings yet

- University of Santo Tomas: Faculty of Arts & LettersDocument5 pagesUniversity of Santo Tomas: Faculty of Arts & LettersAnn KimNo ratings yet

- EAGLE LSAR Product GuideDocument26 pagesEAGLE LSAR Product Guidejaved iqbal0% (1)

- Ieee Research Paper On Voice RecognitionDocument8 pagesIeee Research Paper On Voice Recognitionnoywcfvhf100% (1)

- Literature Review VoipDocument7 pagesLiterature Review Voipafduadaza100% (1)

- Voice BiometricsDocument12 pagesVoice BiometricsStephen Mayhew100% (1)

- Video Remote Interpreting: Medical Educational Legal Mental HealthDocument14 pagesVideo Remote Interpreting: Medical Educational Legal Mental HealthjohnmyassNo ratings yet

- Voice Biometrics WhitepaperDocument5 pagesVoice Biometrics Whitepaperjuanperez23No ratings yet

- Marketing Managemen T: ZeeshanDocument5 pagesMarketing Managemen T: ZeeshanirfanarainNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To Speech and Speaker RecognitionDocument8 pagesAn Introduction To Speech and Speaker RecognitionSyam KushainiNo ratings yet

- Ref-Planning An OhpDocument5 pagesRef-Planning An Ohpfemi adi soempenoNo ratings yet

- English Research PaperDocument8 pagesEnglish Research PaperISHAAN SHETTYNo ratings yet

- Fairy Singh Minor ProjectDocument18 pagesFairy Singh Minor Projectfairy singhNo ratings yet

- GU2 - WorksheetDocument4 pagesGU2 - Worksheetgsimpson4927No ratings yet

- Unit 5 Communication Thrugh Electronic ChannelsDocument7 pagesUnit 5 Communication Thrugh Electronic ChannelsChirasvi KuttappaNo ratings yet

- Impact On OrganizationsDocument14 pagesImpact On OrganizationsogakhanNo ratings yet

- FormulacionDocument490 pagesFormulacionAbigail CarbajalNo ratings yet

- Thesis Video ConferencingDocument6 pagesThesis Video Conferencingafknoaabc100% (2)

- Data Collection MethodDocument45 pagesData Collection MethodLili Nur Indah SariNo ratings yet

- Presented By:: Mohammad Tauqeer (Bem/)Document29 pagesPresented By:: Mohammad Tauqeer (Bem/)M.TauqeerNo ratings yet

- Research Papers On Speech Recognition 2013Document6 pagesResearch Papers On Speech Recognition 2013gvw6y2hv100% (1)

- What Is The Difference Transcription and DictationDocument5 pagesWhat Is The Difference Transcription and DictationRakesh Kumar ChandraNo ratings yet

- Video Conferencing Research PapersDocument7 pagesVideo Conferencing Research Paperszyfofohab0p2100% (1)

- Padmashree Institute of Management and Science: Subject: Topic: Submitted To: Submitted byDocument15 pagesPadmashree Institute of Management and Science: Subject: Topic: Submitted To: Submitted byGulnazNo ratings yet

- Web Proposal FinalDocument13 pagesWeb Proposal Finalthanpinado21No ratings yet

- CH 8Document5 pagesCH 8Noni Paramita SudarliNo ratings yet

- Hints and Tips PGR New 2020 Video Streaming Policy 1Document9 pagesHints and Tips PGR New 2020 Video Streaming Policy 1KABIR RAHEEMNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Speech RecognitionDocument6 pagesResearch Paper On Speech Recognitionclwdcbqlg100% (1)

- Research Paper On Speaker RecognitionDocument5 pagesResearch Paper On Speaker Recognitiongz49w5xr100% (1)

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Note On Comparison On IFRS 17 and IAS 19Document2 pagesNote On Comparison On IFRS 17 and IAS 19xinaxulaNo ratings yet

- English Lesson Plan: Early Years EducationDocument3 pagesEnglish Lesson Plan: Early Years EducationManik BholaNo ratings yet

- Unit 9. Preserving The Environment: A. Dis'posalDocument15 pagesUnit 9. Preserving The Environment: A. Dis'posalDxng 1No ratings yet

- Team Members: M.Abarna (10PX01) V. Agasthiya Priya (10PX02) K.Ajeesh (10PX03)Document50 pagesTeam Members: M.Abarna (10PX01) V. Agasthiya Priya (10PX02) K.Ajeesh (10PX03)Ashokkumar Gnanasekar NadarNo ratings yet

- Rachel Quinlan-Advanced Linear Algebra (Lecture Notes) (2017)Document44 pagesRachel Quinlan-Advanced Linear Algebra (Lecture Notes) (2017)juannaviapNo ratings yet

- Dln2 Extender Package 2008-2009Document10 pagesDln2 Extender Package 2008-2009atfrost4638No ratings yet

- The Financial Statements of Divine Company Are Presented Here DivineDocument1 pageThe Financial Statements of Divine Company Are Presented Here Divineamit raajNo ratings yet

- CORENET E-Submission System Training: DetailsDocument2 pagesCORENET E-Submission System Training: DetailsParthiban KarunanidhiNo ratings yet

- (Challenges and Advances in Computational Chemistry and Physics 24) Kunal Roy (eds.) - Advances in QSAR Modeling_ Applications in Pharmaceutical, Chemical, Food, Agricultural and Environmental Science.pdfDocument555 pages(Challenges and Advances in Computational Chemistry and Physics 24) Kunal Roy (eds.) - Advances in QSAR Modeling_ Applications in Pharmaceutical, Chemical, Food, Agricultural and Environmental Science.pdfKamatchi SankarNo ratings yet

- Oem Ap471 - en PDocument2 pagesOem Ap471 - en PAnonymous iDJw3bDEW2No ratings yet

- Test 2Document33 pagesTest 2Rohini BhardwajNo ratings yet

- 2 Terms and Definitions SectionDocument12 pages2 Terms and Definitions SectionJawed AkhterNo ratings yet

- Uruguay The Owners Manual 5th EdDocument240 pagesUruguay The Owners Manual 5th EdlinkgineerNo ratings yet

- School Zone DatabaseDocument18 pagesSchool Zone DatabaseActionNewsJaxNo ratings yet

- Welcome Unit - Basic - Aula 2 e Aula 3 e 4grammarDocument167 pagesWelcome Unit - Basic - Aula 2 e Aula 3 e 4grammarRayane VenceslauNo ratings yet

- Ethics Position PaperDocument4 pagesEthics Position PaperCaila Chin DinoyNo ratings yet

- Mankind and Mother Earth - A Narrative History of The World (PDFDrive)Document680 pagesMankind and Mother Earth - A Narrative History of The World (PDFDrive)Naveen RNo ratings yet

- OmniOMS Output GenerationDocument2 pagesOmniOMS Output Generationnitin.aktivNo ratings yet

- p2c2 ProgressmeasurementDocument19 pagesp2c2 ProgressmeasurementicetesterNo ratings yet

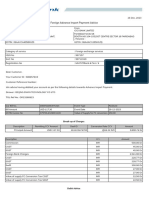

- 2023-08-12Document5 pages2023-08-12nurull.samsiyahNo ratings yet

- MWL 1.0 (Tournament Rules 3.0.2)Document8 pagesMWL 1.0 (Tournament Rules 3.0.2)peterNo ratings yet

- Midterm 2009 Chem 2E03Document9 pagesMidterm 2009 Chem 2E03hanan711No ratings yet

- Naskah Listening Paket 1 KemitraanDocument4 pagesNaskah Listening Paket 1 KemitraanGema Galgani Jumi SNo ratings yet

- Dwnload Full Psychology From Inquiry To Understanding Canadian 2nd Edition Lilienfeld Test Bank PDFDocument36 pagesDwnload Full Psychology From Inquiry To Understanding Canadian 2nd Edition Lilienfeld Test Bank PDFgiaourgaolbi23a100% (10)

- The RunnerDocument31 pagesThe RunnerSlliceire Liguid PlatonNo ratings yet

- Getting To Grips With FDADocument84 pagesGetting To Grips With FDATanishq VashisthNo ratings yet

- FGGHHDocument366 pagesFGGHHJyoti ThakurNo ratings yet

Oral History at A Distance:: Conducting Remote Interviews Webinar

Oral History at A Distance:: Conducting Remote Interviews Webinar

Uploaded by

mobcranbOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Oral History at A Distance:: Conducting Remote Interviews Webinar

Oral History at A Distance:: Conducting Remote Interviews Webinar

Uploaded by

mobcranbCopyright:

Available Formats

Oral History at a Distance:

Conducting Remote Interviews Webinar

Baylor University Institute for Oral History

Oral History Association

Adrienne Cain – Legal/Ethical Implications of Distance Interviewing

Whether done in-person or remotely, it is imperative that oral history practitioners are legally

compliant and ethically sound in their interview work. Although the legal guidelines may vary by

location, the Oral History Association’s Principles and Best Practices provide a useful framework for

ethical considerations (www.oralhistory.org).

With remote interviewing, practitioners are often challenged with building rapport with their

interviewees, especially if the oral historian is unable to conduct a pre-interview. If feasible, the oral

historian should conduct any pre-interview contact or conversations in the same manner that the

interview will be recorded. For example, if the interview will be conducted using an online video

recording platform, use that same platform for the pre-interview. Therefore, once the interview day

arrives, the interviewee will not be distracted or uncomfortable with being confronted with a new

platform. By conducting the pre-interview in the same manner, the practitioner makes the interviewee

more comfortable with the process.

An important part of the pre-interview process is to provide information to participants about the

project, which is referred to as informed consent. Informed consent involves making sure the

interviewee knows the process and procedures of the project, is informed of their rights as a

participant, and understands the necessity of the legal release form. More information about these

particular rights can be found on OHA’s website. One way to help make sure interviewees are informed

is by providing a project design, or a document that spells out the plan and purpose for the project

being conducted.

An additional challenge in conducting remote interviews is obtaining a signed release form. With any

interview—remote or not—it is imperative to obtain a signed release form that includes a donor

agreement, copyright transfer, and future use statement. There are several ways to secure this form such

as email, electronic signature, scanning, or even traditional “snail mail.” It is essential to have this form

because there are several rights covered by copyright that are needed in order to complete oral history

projects as well as the potential outcomes and materials that will derive from these interviews.

In closing, with remote interviews there are several legal and ethical considerations that should be

made for oral history projects. For those in the U.S., John Neuenschwander’s Oral History and the Law is a

great resource that surveys the various legal components of oral history projects. If outside of the U.S.,

practitioners should become familiar with the copyright laws of their country, region, and/or territory.

A great resource to use to become more familiar with these laws is the World Intellectual Property

Organization’s website (www.wipo.org).

Stephen Sloan – Interviewing at a Distance

The collaborative work between interviewer-interviewee to create an oral history undergoes some

fundamental changes when participants engage in the process at a distance. It is essential for

practitioners to think through the ways this shapes their exchange, weighing research goals, shifted

interviewer and narrator frameworks, and desired outcomes.

After considering the implications of taking interviews to a remote format, oral historians should then

consider the new frameworks for the interviewer-narrator interaction. Interviewers can often employ

distance interviews to save time and money, expand the geographic distribution of their interviewees,

accelerate the pace of their project, and make scheduling easier. The interviewer can work from a more

predictable setting and be situated where their behavior, even something as simple as note taking or

managing recording devices, can be less distracting.

For the narrator, distance interviewing can, at times, be more empowering by giving them more control

over the scheduling and location of the interview. It is also easier for them to terminate the oral history

and they may feel less social pressure with the setup. For the narrator, they also have more control of

the pace of how they share their story as the interview can be continued or rescheduled for another day.

In considering the remote interviewer-narrator relationship, there are additional factors to weigh.

Studies on distance interviews draw conflicting conclusions on whether the distance format enhances

phenomena such as truth-telling or dealing with sensitive topics. While distance interviews can seem

less invasive and more private, the introduction of more technology between the two parties and

concerns of surveillance/security may be at play in the oral history as well. All the dynamics of

increasing the social distance between interviewer and interviewee influence the oral history, from

establishing trust, to maintaining motivation and keeping concentration, to limiting the data passed

between interviewee and interviewer to verbal elements. The new format also passes more control to

the narrator and diminishes the control the interviewer has over the exchange, including the narrator’s

recording environment.

For a host of reasons—development of technology, rising costs and declining budgets, growth in

transnational studies, work with at-risk populations—distance interviewing is a tool that will be

increasingly used by oral historians. As this evolves, careful consideration is needed to adapt established

best standard and practices to this new form. Although it seems familiar, even at a distance, the

position of the interviewer and narrator shifts the character of the exchange in many critical ways.

Steven Sielaff – Recording Remote Interviews

Any discussion of remote interviewing technology for oral history should begin with a reminder of best

practices for recording preservation-quality audio for long-term archival holdings. In general, audio

practitioners should aim for uncompressed WAV format recordings at “CD Quality” or better (16

bit/44.1kHz). For video there are still several acceptable options (MP4/MOV/AVI/AVCHD) so that

typically you are choosing a format your archiving institution is familiar with and/or a format that is as

uncompressed as you can afford when considering total preservation server space investment. Storage

estimates for one-hour interviews range from 1GB for WAV audio to 10-30GB for HD video.

Professional audio recorder companies currently offer entry-level models in the $250-350 range, some of

which feature quality on-board microphones or free XLR external microphones. Digital storage during

your project should follow the concept of LOCKSS (Lots of Copies Keeps Stuff Safe) and is most often

achieved through a variety of on-board, portable physical, and cloud-based storage solutions.

When considering remote interviewing options, one should always focus on best practices to determine

if their choices in technology measure up to these preservation standards. The most frequent offenders

are file type (many recording apps only record in MP3) and storage logistics (do you have enough local

storage space/can you easily offload the file to your venue of choice?). In addition, one should consider if

extant professional-grade equipment should be used in place of built-in cameras/microphones of lesser

quality. For example, does it make more sense to allow a video conferencing application to record an

interview or should you place near/link up professional equipment to record the conversation

separately? Keep in mind that your interviewee’s equipment and internet bandwidth issues may play

into this equation as well. Also, consider how you might handle the introduction of video into an audio-

only project. It is typically advantageous to see the interviewee to connect during the session, while the

actual recorded video can be converted to an audio file afterwards as needed.

Technology to enable your remote interviews falls under the following categories:

• Landline telephone calls – requires physical adapters to run telephone signals to a professional

recorder or a call recording service that sends you the recording afterwards

• Cellular telephone calls – requires a smartphone application capable of recording calls in WAV

format, physical adapters to run telephone signals to a professional recorder, or a call recording

service that sends you the recording afterwards

• Video conference calls – requires microphones and/or cameras for both participants on either a

desktop, laptop, tablet, or smartphone device, video conferencing software, and the ability to

record the conversation either natively within the software or with separate screen/audio

capture software on the interviewer’s system

Recording from your computer can be aided through the purchase of USB microphones, external

webcams, and headphones/headsets. Testing the equipment and recording functions beforehand with

friends or as part of a pre-interview process is recommended. In addition, please consider potential

security risks of allowing recordings of your oral history interviews to be processed by third-party

companies or placed on cloud storage servers. In general, the more at-risk your project topic, the more

local you should make your recordings (either conducting the interview in-person or only recording

remote interviews on your local device).

You might also like

- Speech Recognition, Digitization, GenerationDocument12 pagesSpeech Recognition, Digitization, GenerationSireesha Tekuru100% (6)

- Ec Axial Fan - Axiblade: Nominal DataDocument1 pageEc Axial Fan - Axiblade: Nominal DataAykut BacakNo ratings yet

- University of Santo Tomas: Faculty of Arts & LettersDocument5 pagesUniversity of Santo Tomas: Faculty of Arts & LettersAnn KimNo ratings yet

- EAGLE LSAR Product GuideDocument26 pagesEAGLE LSAR Product Guidejaved iqbal0% (1)

- Ieee Research Paper On Voice RecognitionDocument8 pagesIeee Research Paper On Voice Recognitionnoywcfvhf100% (1)

- Literature Review VoipDocument7 pagesLiterature Review Voipafduadaza100% (1)

- Voice BiometricsDocument12 pagesVoice BiometricsStephen Mayhew100% (1)

- Video Remote Interpreting: Medical Educational Legal Mental HealthDocument14 pagesVideo Remote Interpreting: Medical Educational Legal Mental HealthjohnmyassNo ratings yet

- Voice Biometrics WhitepaperDocument5 pagesVoice Biometrics Whitepaperjuanperez23No ratings yet

- Marketing Managemen T: ZeeshanDocument5 pagesMarketing Managemen T: ZeeshanirfanarainNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To Speech and Speaker RecognitionDocument8 pagesAn Introduction To Speech and Speaker RecognitionSyam KushainiNo ratings yet

- Ref-Planning An OhpDocument5 pagesRef-Planning An Ohpfemi adi soempenoNo ratings yet

- English Research PaperDocument8 pagesEnglish Research PaperISHAAN SHETTYNo ratings yet

- Fairy Singh Minor ProjectDocument18 pagesFairy Singh Minor Projectfairy singhNo ratings yet

- GU2 - WorksheetDocument4 pagesGU2 - Worksheetgsimpson4927No ratings yet

- Unit 5 Communication Thrugh Electronic ChannelsDocument7 pagesUnit 5 Communication Thrugh Electronic ChannelsChirasvi KuttappaNo ratings yet

- Impact On OrganizationsDocument14 pagesImpact On OrganizationsogakhanNo ratings yet

- FormulacionDocument490 pagesFormulacionAbigail CarbajalNo ratings yet

- Thesis Video ConferencingDocument6 pagesThesis Video Conferencingafknoaabc100% (2)

- Data Collection MethodDocument45 pagesData Collection MethodLili Nur Indah SariNo ratings yet

- Presented By:: Mohammad Tauqeer (Bem/)Document29 pagesPresented By:: Mohammad Tauqeer (Bem/)M.TauqeerNo ratings yet

- Research Papers On Speech Recognition 2013Document6 pagesResearch Papers On Speech Recognition 2013gvw6y2hv100% (1)

- What Is The Difference Transcription and DictationDocument5 pagesWhat Is The Difference Transcription and DictationRakesh Kumar ChandraNo ratings yet

- Video Conferencing Research PapersDocument7 pagesVideo Conferencing Research Paperszyfofohab0p2100% (1)

- Padmashree Institute of Management and Science: Subject: Topic: Submitted To: Submitted byDocument15 pagesPadmashree Institute of Management and Science: Subject: Topic: Submitted To: Submitted byGulnazNo ratings yet

- Web Proposal FinalDocument13 pagesWeb Proposal Finalthanpinado21No ratings yet

- CH 8Document5 pagesCH 8Noni Paramita SudarliNo ratings yet

- Hints and Tips PGR New 2020 Video Streaming Policy 1Document9 pagesHints and Tips PGR New 2020 Video Streaming Policy 1KABIR RAHEEMNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Speech RecognitionDocument6 pagesResearch Paper On Speech Recognitionclwdcbqlg100% (1)

- Research Paper On Speaker RecognitionDocument5 pagesResearch Paper On Speaker Recognitiongz49w5xr100% (1)

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Mobile Survey ToolkitDocument24 pagesMobile Survey ToolkitOxfamNo ratings yet

- Note On Comparison On IFRS 17 and IAS 19Document2 pagesNote On Comparison On IFRS 17 and IAS 19xinaxulaNo ratings yet

- English Lesson Plan: Early Years EducationDocument3 pagesEnglish Lesson Plan: Early Years EducationManik BholaNo ratings yet

- Unit 9. Preserving The Environment: A. Dis'posalDocument15 pagesUnit 9. Preserving The Environment: A. Dis'posalDxng 1No ratings yet

- Team Members: M.Abarna (10PX01) V. Agasthiya Priya (10PX02) K.Ajeesh (10PX03)Document50 pagesTeam Members: M.Abarna (10PX01) V. Agasthiya Priya (10PX02) K.Ajeesh (10PX03)Ashokkumar Gnanasekar NadarNo ratings yet

- Rachel Quinlan-Advanced Linear Algebra (Lecture Notes) (2017)Document44 pagesRachel Quinlan-Advanced Linear Algebra (Lecture Notes) (2017)juannaviapNo ratings yet

- Dln2 Extender Package 2008-2009Document10 pagesDln2 Extender Package 2008-2009atfrost4638No ratings yet

- The Financial Statements of Divine Company Are Presented Here DivineDocument1 pageThe Financial Statements of Divine Company Are Presented Here Divineamit raajNo ratings yet

- CORENET E-Submission System Training: DetailsDocument2 pagesCORENET E-Submission System Training: DetailsParthiban KarunanidhiNo ratings yet

- (Challenges and Advances in Computational Chemistry and Physics 24) Kunal Roy (eds.) - Advances in QSAR Modeling_ Applications in Pharmaceutical, Chemical, Food, Agricultural and Environmental Science.pdfDocument555 pages(Challenges and Advances in Computational Chemistry and Physics 24) Kunal Roy (eds.) - Advances in QSAR Modeling_ Applications in Pharmaceutical, Chemical, Food, Agricultural and Environmental Science.pdfKamatchi SankarNo ratings yet

- Oem Ap471 - en PDocument2 pagesOem Ap471 - en PAnonymous iDJw3bDEW2No ratings yet

- Test 2Document33 pagesTest 2Rohini BhardwajNo ratings yet

- 2 Terms and Definitions SectionDocument12 pages2 Terms and Definitions SectionJawed AkhterNo ratings yet

- Uruguay The Owners Manual 5th EdDocument240 pagesUruguay The Owners Manual 5th EdlinkgineerNo ratings yet

- School Zone DatabaseDocument18 pagesSchool Zone DatabaseActionNewsJaxNo ratings yet

- Welcome Unit - Basic - Aula 2 e Aula 3 e 4grammarDocument167 pagesWelcome Unit - Basic - Aula 2 e Aula 3 e 4grammarRayane VenceslauNo ratings yet

- Ethics Position PaperDocument4 pagesEthics Position PaperCaila Chin DinoyNo ratings yet

- Mankind and Mother Earth - A Narrative History of The World (PDFDrive)Document680 pagesMankind and Mother Earth - A Narrative History of The World (PDFDrive)Naveen RNo ratings yet

- OmniOMS Output GenerationDocument2 pagesOmniOMS Output Generationnitin.aktivNo ratings yet

- p2c2 ProgressmeasurementDocument19 pagesp2c2 ProgressmeasurementicetesterNo ratings yet

- 2023-08-12Document5 pages2023-08-12nurull.samsiyahNo ratings yet

- MWL 1.0 (Tournament Rules 3.0.2)Document8 pagesMWL 1.0 (Tournament Rules 3.0.2)peterNo ratings yet

- Midterm 2009 Chem 2E03Document9 pagesMidterm 2009 Chem 2E03hanan711No ratings yet

- Naskah Listening Paket 1 KemitraanDocument4 pagesNaskah Listening Paket 1 KemitraanGema Galgani Jumi SNo ratings yet

- Dwnload Full Psychology From Inquiry To Understanding Canadian 2nd Edition Lilienfeld Test Bank PDFDocument36 pagesDwnload Full Psychology From Inquiry To Understanding Canadian 2nd Edition Lilienfeld Test Bank PDFgiaourgaolbi23a100% (10)

- The RunnerDocument31 pagesThe RunnerSlliceire Liguid PlatonNo ratings yet

- Getting To Grips With FDADocument84 pagesGetting To Grips With FDATanishq VashisthNo ratings yet

- FGGHHDocument366 pagesFGGHHJyoti ThakurNo ratings yet