Professional Documents

Culture Documents

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

13 viewsChapter 12

Chapter 12

Uploaded by

Rameesha Noman12

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5825)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Non Recognition of Print Advertising Emotion Arousal and Gender EffectsDocument20 pagesNon Recognition of Print Advertising Emotion Arousal and Gender EffectsRameesha NomanNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 and 3Document56 pagesChapter 1 and 3Rameesha NomanNo ratings yet

- Learning Strategy & Process 300621Document13 pagesLearning Strategy & Process 300621Rameesha NomanNo ratings yet

- Larkana Sat Vi ResultDocument1,862 pagesLarkana Sat Vi ResultRameesha NomanNo ratings yet

- Khairpur Sat Vi Result-2Document1,095 pagesKhairpur Sat Vi Result-2Rameesha Noman100% (1)

- Sukkur Sat Vi Result-2Document624 pagesSukkur Sat Vi Result-2Rameesha NomanNo ratings yet

- Assignment No 2Document4 pagesAssignment No 2Rameesha NomanNo ratings yet

- Kambar Sat Vi ResultDocument775 pagesKambar Sat Vi ResultRameesha NomanNo ratings yet

Chapter 12

Chapter 12

Uploaded by

Rameesha Noman0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

13 views12 pages12

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Document12

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

13 views12 pagesChapter 12

Chapter 12

Uploaded by

Rameesha Noman12

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

You are on page 1of 12

280 _ HRM AND CONTEMPORARY ISSUES

O Opening Case Study Localisation in the Gulf States

|As you wil see in this chapter, ‘talent’is interpreted in diferent ways across different organisations and cultures,

Broadly speaking, it can mean exceptional skils relative to others, for example a talented sportswoman has bet-

ter skills than others in her field, or it can mean the particular, idiosyncratic abilities that people have. This case

leans towards the idea of talent as idiosyncratic rather than relative.

A serious economic problem facing the Gulf States is the employment of locals in place of migrants and expatri-

ate workers. Gulf populations are young and growing. Young Saudis and Omanis, for example, want good jobs

and a career, but the working populations of the Guif States contain large numbers of foreign workers. The tra-

ditional way of finding jobs for locals has been to expand the public sector with cash from oll revenues. Public

sector jobs are attractive to locals because they offer high status and are well paid and secure. But the public

sectors in the Gulf cannot keep expanding ~ employing locals in the private sector is a priority.

‘To catalyse the employment of locals, Gulf countries and others have created localisation policies (e.g. Saudisa~

tion, Omanisation).In essence, these require employers to employ a percentage of locals in their workforce, with

the percentage varying by sector and depending upon economic importance and past progress. So, we can see

localisation as a particular form of talent management that focuses not on finding the best of the bunch but on

deploying the talents of local people in decent jobs and laying the foundations for social and economic progress.

But progress towards localisation has been slow. A key question therefore centres around the barriers to locali-

sation: what are they and why do they persist?

‘Some barriers are well known. They include a lack of management and leadership training for locals, poor train-

ing, poor English language training, and negative perceptions of private sector employment by locals. New

research, however, has revealed some more complex structural problems (Al Nahdi and Swalles, 2016). Bearing

in mind that many foreign managers have influence over staffing decisions and that many private organisations

are owned by locals, additional barriers to employing local talent include:

» Networking among expatriate managers suppresses the employment of locals.

» Local owners and managers preferring to employ foreign workers because they are perceived as being more

productive.

» Inter-fath barriers - most foreign workers are not Muslim and observe different religious practices at work.

» Local owners and managers preferring to employ foreigners with whom they can maintain a greater social

distance because of differences in language and customs.

Local talent therefore, in its broadest sense, is being suppressed by a lack of opportunity. Despite long-standing

efforts by governments to increase the percentage of locals in the workforce, there are some deep-rooted bar-

Tiers that impede progress. Some changes seem relatively easy, such as prioritising better language and man-

agement training, but some of these barriers will not be overcome in the short term. Foreigners prefer to employ

foreigners because they are seen as more productive and easier to manage, and some locals who are owners

and/or managers can control their businesses more easily through foreigners than through other locals by lever-

aging differences in language and culture.

Social barriers of this kind are not easily dismantled, and the case illustrates the sorts of issues that arise in tal-

ent identification and that can be extrapolated to talent management in organisations. Identifying talent is fraught

with impressions, feelings, and biases.

Questions

1. Why can cash-tich governments not continue to expand the public sector to employ locals?

2 To what extent would you agree with the suggestion that foreign workers in the Gulf States are more efficient

and productive than local workers?

‘3. What types of prejudices might exist against local workers in the Gulf and Middle East?

is often given asthe influential book The War jor Talen

INTRODUCTION (Michaels, Handfeld-Jones and Axelrod, 2001). The ide

‘A quick look through the management literature might that corporations were fighting a war for talent and com

suggest that talent management is a recent phenom- _ peting with each other for high-quality employees spreac

enon, Most articles postdate 2000, and the starting point quickly through the boardrooms of corporate Americ

and Norther Europe. Good people were in short supply,

orso itwas assumed.

However, althouigh talk of ‘talent’ and talent manage-

ment’ in the context of everyday work was uncommon

before 2000, the benefits of talented people to organi-

sations and society had been recognised long before

(Swailes, 2016). By the middle of che twentieth century,

there was much interest in identifying promotable execu

tives and the characteristics that gave them their pro-

motability (Bowman, 1964; Randle, 1956). What is clea,

however is that there has been a shift in the emphasis that

domestic and multinational organisations now put on

managing talent.

‘An extensive study by the Boston Consulting Group

(8CG, 2013) of executives across 34 countries found that

while talent management was the most pressing HRM

priority for companies, it was also the one in which their

capabilities were the lowest. Similar findings came out

ofa large Pricewaterhouse Coopers survey of executives

(PwC, 2014), which reported that 63 per cent of execu

tives felt that skills shortages were a serious problem

but only 34 per cent felt that their employee selection

systems were ‘well prepared’ for the challenges that lie

ahead.

Despite the heavy rhetoric about the importance of

talent identification, many companies do not run talent

programmes. Factors positively influencing the adop-

tion of talent management in multinationals are size of

the firm, whether products/services are standardised,

whether the firm has a global HR approach, and whether

the firm operates in relatively low technology sectors

(McDonnell etal, 2010). Thereis no shortage of prescrip

tive advice on how to design and operate talent pro-

grammes, and we do not repeat that advice here. Instead,

we set out a more critical analysis of talent management

in an effort to better appreciate the practical operating

problems that could arise when talent programmes are

attempted.

DEFINITIONS

Incommon with other HR practices such as performance

related pay, organisations are free to choose whether

they engage with talent management or not. If they do

engage with it, then they are free to define it and to oper-

ate it in any way they wish to suit their own outlook on

how people should be managed and their market posi-

tion. An organisation might run a talent programme but

prefer to call it something else that better fits with the

organisation's language and culture, What this means is,

that organisations may run what they see as talent pro-

‘grammes but that do not match definitions used by

academics.

‘TALENT MANAGEMENT: CRITICAL PERSPECTIVES 281

Talent and talent management

First, what is talent? In the context of gifted children,

Howe, Davidson and Sloboda (1998) argued that talent

has five properties. These include: a partly innate and

‘genetically transmitted component, that talent is some-

thing confined to a minority, and that talents are domain-

specific, for example, music or dance. They refer to the

genetic component as the ‘talent account’ but conclude

that the main determinants of excellence are differences

in early experiences, opportunities, training, and practice.

Extending this theory to organisations suggests that:

«employees showing exceptional talent will make-up

only a small proportion of the workforce;

‘+ employees will need ample opportunities to hone and

practice their talents; and,

«employees will use social capital accumulated in early if.

In telation to talent and giftedness in art, sport and other

domains, ‘talent is often taken as meaning the top 10 per

cent ofan ability group compared to their age peers (Gagne,

2000), The link to age is important since, for example, itis

inappropriate to compare the best pianists aged 16-18

with the best pianists aged 30-40 simply because the older

group has more experience. A similar philosophy is usually

applied in workplaces where talent might be sought across

various levels of seniority and different operational areas.

The easiest way of looking at talent management is to

see it a5 differentiating between current and porential

employees in terms of their performance, contribution,

and especially their potential; sorting the ‘best from the

rest’ Potential is a key factor because, although high per-

formance is important, not all high performers are deemed

to have the potential to go further in the organisation. This

leads usto an exclusive or elitist view ofa workforce and the

labour markets that supply new employees: itis exclusive

because most employees are excluded from the talent poo.

Following the elitist line, only a small proportion of

‘employees will be deemed as talented. Although research on

talent management has been impeded by a lack of consen-

sus around a definition, the dusts starting to settle now and

‘we suggest that, fr eltist talent management, the definition

provided by Collings and Mellahi (2009:305) capeures it wel,

‘As they see it, organisational talent management isthe

activities and processes that involve the systematic

identification of key positions which differentially con-

tribute to the organisation's sustainable competitive

advantage, the development of a talent poo! of high

potential and high performing incumbents to fill these

roles, and the development ofa differentiated human

resource architecture to facilitate filling chese positions

with competent incumbents and to ensure their con-

tinued commitment to the organisation.

282 HRM AND CONTEMPORARY ISSUES

‘Three things are emphasised in this definition: high poten-

tial people, sets of human resource management practices

to leverage and further develop their potential, and fitting

‘these people into key or pivotal roles where ther skis will

rmake the greatest impact on the organisation. This approach

is unashamedly elitist. It assumes that some people are of

‘more use than others and that some roles have more influ-

ence on organisational success than others. Pivotal roles

are not just the most senior however; people in lower level,

ccustomer-facing roles can have big effects on organisational

performance.

@ Class Activity

New research suggests that in sport and arts

‘a small proportion of super-performers make

disproportionately high impact on organisational

performance,

» To what extent might this result generalise to more

traditional work sectors?

» Are there any characteristics of the nature of dif-

ferent types of work that make this finding more or

less likely?

Global talent management

Global talent management is essentially the same philoso-

phy and approach but applied across a much larger scale.

Because ofthe larger scale global talent managements more

‘complex as it has to respond to an organisation’ differing

strategic priorities globally and be sensitive to cross-national

and regional differences in beliefs about how people should

bbe managed, Scullion and Collings (2011) give the following.

reasons for the emergence of global talent management asa

key strategic issue for multinational corporations.

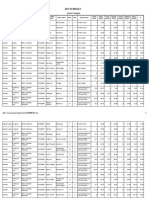

Table 12.1 Talent management and human resource management

+ Agrowing belietamong executives that global business,

success rests on globally competent talent.

«+ Agrowing bei that there are shortages of management

and leadership talent on an international scale while rec-

ognising that talented employees may be located (hid-

den) in complex global operations. Ways of surfacing the

latent talent in a workforce are therefore priority

Global talent searches are needed to identity the peo-

ple who are capable of managing very diverse work

forces brought about by rising gender diversity in the

workplace and much easier mobility of labour wit

and across labour markets Easier mobility also makes

it easier for high potential people to work elsewhere —

so retaining them has become more ofa priority

The increasing shift to knowledge-based and service

sectors in which human capital has more direct con-

nections to organisational success because of the

increasingly intellectual nature of work.

Inclusive talent management

‘As mentioned above, talent management is usually viewed

through an elitist lens, but it can be approached in a vari-

ety of ways. Some organisations, perhaps because of sen-

sitivity to possible criticism of elitism or perhaps because

‘of genuine concerns about the morality of elitism, operate

more inclusive strategies. Inclusive talent strategies appear

to be much less common than elitist versions, however,

and raise questions about how they might differ from

good but standardised human resource management

practices. To get a better understanding of what inclusive

talent management could be like we need to appreciate

how exclusive approaches differ from human resource

management (see Table 121).

Human resource management focuses on all employees

for the whole of their employment with the organisation,

Dimension | HRM

"| Exclusive talent management.

Scope | Coversall employees from recruitment through

to termination of employment.

Focuses ona minority of employees forso long as they arena

talent poo

organisation should be lke. Includes strategies,

polices, and practices unique tothe organisation.

Heavily influenced by the ways that line managers

incerpret and implement policies,

Functions | Coversall HR remits(eg, reward, employment | Focuses on identifying high potential employees and delivering

relations and performance management)and | a differentiated development experience. emphasises career

compliance with employment lav. development and succession planning.

Purpose | Looksforconstencyofexperenceacossjobs, | Focuses on succession planning for key positions and filing key

‘aces and roles during theliftime ofempoymen. | positions with high potenial people.

Drivers | Visions of what employment with the Talk of scarcity and competitive advantage. Closely inked

to the resource-based view n choosing whom to develop.

Conformance to sector and labour marker expectations. Heavily

influenced by senior managers, consultants, and a talent team in

designing the approach.

Itcovers a wider range of functions than talent manage-

rent and operates those functions across all roles and

grades. The human resource management experience is

heavily dependent upon the individual's relationship with

his/her line manager, whereas the talent experience is

overlaid with exposure to senior managers and other high

potential people.

If inclusive talent management is to be more than 2

seandard human resource management experience on

offer to all employees, then it has to offer something dif-

ferent, Recent theoretical consideration of what inclusive

talent management could entail (Swailes, Downs; and Orr,

2014) proposes the following characteristics:

«Inclusive talent management has to focus on all (or at

least most) employees.

+ Talent in inclusive talent management in seen as an

absolute characteristic ofa person, not something that

is relative to the talent of others.

‘Organisations must try to identify and deploy the

unique talents of all employees. Talent deployment on

a larger scale requires greater organisational willingness

to rotate people through jobs as a way of helping to

discover where talents are best deployed.

‘s Wherea person's talent cannot be effectively deployedin

an organisation then reasonable efforts should be made

to help the individual deploy their talents ‘elsewhere.

In sharp contrast to the elitist definition, inclusive talent

management has been defined as, ‘the recognition and

acceptance that all employees have talent together with

the on-going evaluation and deployment of employees

in positions that gives the best fit and opportunity (via

participation) for employees to use those talents (Swailes

et al, 2014: 533). This approach to talent management is

unlikely to become widespread, however, because of the

costs of implementing it. Nevertheless itis in many ways

a more accurate description of ‘true’ talent management

since it recognises and tries to use the abilities, interests,

and skills of an entire workforce rather than a small part

‘of one. Indeed, Swailes and colleagues (2014) argued that

conventional, elitist talent management is better seen as

partial talent management since it only addresses part of

the talent available to an organisation.

St2P4y, Questions

“2, 1. Of the forms of talent programme

|= desorbed above, which do you think

(3 has the strongest moral basis and why?

2. Asan employee, which type of

programme would you prefer to be

part of?

TALENT MANAGEMENT: CRITICAL PERSPECTIVES 283

THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVES

Strategic human resource management

Eltse approaches to talent management fit very well with

classic theory around strategic human resource manage-

ment. In particular, eitist talent management fits with and

brings life to the idea of workforce differentiation (Huseid

and Becker, 2011). In the differentiated workforce, not all

‘employees are thought to contribute equally. Some jobs

are assumed to be more important than others that, while

they may be essential, do not add as much value to the

“organisation and may be easily staffed or contracted-out.

‘Theory suggests that a differentiated workforce needs a

differentiated human resource architecture to get the best

‘out of it (Becker and Huselid, 2006). Failure to recognise

differentiation impedes the organisation's competiveness

and competitive advantage. The key question this poses

is whether organisational competitiveness derives from

the average performance of a majority of employees or

the ‘super’ performance of a minority. New research is

‘very clear that, in some sectors, employee performance is

not normally distributed but follows a power distribution

(Aguinis and O'Boyle, 2014; O’Boyle and Aguinis, 2012).

Put simply, outstanding performance by a minority has

a massive effect impact on organisational performance.

‘Much mote research is needed to test the extent to which

thisappliesin other business sectors and cultures, however.

Talent management is aform of human resource devel-

opment and, like most HRD, exists largely for the benefit

of organisations not individuals. This is consistent with

human capital theory and the resource-based view (Bar-

rey, 1991; Wright, Dunford and Snell, 2001) which assume

that it is not worthwhile for organisations to develop

employees unless it serves the organisation to do so and

even then they may leave (Bryson, 2007). Human capital

theory has been influential in explaining why organisa-

tions should engage in HRD, and it recognises two types

of sis general and firm-specific. General skills are usable

to other organisations whereas firm-specific sils by defi-

nition, are not. From a human capital perspective, it only

rmakes sense to run talent programmes that develop firm-

specific skills as these give ahigher return on investment.

‘The resource-based view shifted explanations of competi-

tive advantage away from external factors, such as social

and economic trends, towards greater recognition of the

role of internal factors. To give sustained competitive

advantage, resources need to be rare, valuable, inimitable

and integrated into the business (organised) and the more

of these characteristics that a resource has the more use-

ful it becomes. This makes sense because, for example, a

resource that is easily obtained by competitors (not rare)

andJor which is easily copied by competitors will not give

competitive advantage for long.

284

HRM AND CONTEMPORARY ISSUES

Resources can be many things such as natural resources,

capital, and inter-firm relationships, and we need to ask:

what is the resource in talent management? At a simple

level itis the people named as talent who are the resource.

‘We use ‘named’ here because in this context to say ‘denti-

fied’ as talent suggests that talent is objectifiable, some-

thing that can be identified with precision such that

‘anyone not identified as talent is not talented. With that

‘caveat in mind, the resource has to be more than simply

the people and much more about what they bring. The

resource is better seen as social structures that the ‘tal

ented! create and use to benefit the organisation, itis their

relationships and their networks and their ability to use

them effectively tha lie atthe heart ofthe true resource.

The distinctive social architecture that develops among

people is rare in the sense that no other identical archi-

tecture or configuration exists and its inimitable because

other organisations cannot copy the same architecture. If

this unique social structure is well organised, then the con-

ditions for talent management to contribute a distinctive

resource are met. There is some evidence for this theory

from research on what happens to stars’ when they move

between organisations (Groysberg, Lee and Nanda, 2008;

Groysberg, Nanda and Nohrria, 2004). Groysberg and col-

leagues found that the performance of'stars' dipped when

theyswitchedtoanother organisation, and thisisexplained

by a loss or fracture of the networks that sustained the

stars before switching. While some of a star's network

remains in place, important aspects of it are lost and with

it the ability to perform at the same very high level. This

also explains why organisations often recruit whole teams,

for example research and development teams or teams of

traders, Recruiting a whole team improves the chances of

preserving the social architecture that sustained the high

performing team, and the chances of impor ilar

high levels of performance are maximised.

Now that we know why talent management should

work, wo related questions arise. First, are there other rea-

sons why organisations pursue it? Second, why do some

organisations not adopt it? Reasons for not adopting tal-

‘ent management include:

+ Managers being satisied with organisational perfor.

mance to the extent that deliberate employee differ-

entiation strategies are judged unnecessary

‘¢ Managers believing that there are more pressing pri-

orities to boost performance than talent management.

+ Traditions of collectivism and equality in organisa-

tional cultures that would cash with the philosophy

of elitist talent management. This explains why tal-

ent programmes occur less often in the public sector

which tends to be sensitive to hard performance evalu-

ation and explicit valuation of employee contributions,

accelerated promotion, and reward (Boyne, Jenkins

and Pools, 1999).

+ In large organisations, the sheer complexity of design-

ing a fair international talent operation may be a

disincentive.

‘© The (in)abilty of senior HR managers to understand

business needs to the extent that ausefultalentsystem

could be designed and operated.

Oz ical Thinking 12.1 Geographical variation

in philosophy

Later inthis chapter we refer to a ‘dark side’ to sum-up

possible negative consequences of talent manage-

ment. Think of the basics: A small number of employ-

‘208 is selected for special development aimed at

accelerating ther careers. The majorty of employees

are not. We would like you to think about possible dark-

side effects and how organisations could minimise the

risks of a dark side occurring. To help you do this

Questions

1. Organisation cultures are all different, so what

types of culture could accentuate a dark side?

2 What features could organisations design into talent

programmes to minimise the risk ofa dark side?

3. How could organisations assess the extent to

which a dark side is occurring?

Institutionalism

In relation to why organisations adopt or do not adopt

talent systems, there is a compelling explanation over and

above the resource-based view. In essence, some organi-

sations adopt talent management because others do.

‘This explanation relies on organisational insttutionalism

theory, which explains why organisations operating in the

same sector are often very similar in the ways that they

structure and operate. Think of banks and universities, for

‘example, Every organisation operates in afield of organisa-

tions providing the same or similar products or services.

Ina field, organisations source new employees from the

same labour markets, access the same supply chains and

have similar stakeholder configurations. Fields create pres-

sues for organisations to behave and function in the same

or similar ways. Failure to conform to institutional pres-

sures and look the same can be problematic for an organi-

sation, a its reputation inthe field could be tarnished by

‘nonconformity

Institutions are not organisations and should not be

confused with them, An institution is, ‘the more or less

taken for granted repetitive social behaviour that is under-

pinned by normative systems and cognitive understand-

ings that give meaning to social exchange and thus enable

selfreproducing social order (Greenwood et al, 2008: 4).

Talent management arose in a particular corporate con-

text in che United States. efits with the American tradition

of individualism ancl comparatively light unionisation and

employment relations legislation. Organisations in Scandi-

ravia, Southern Europe, and South America, for example,

‘operate in very different contexts. All countries operate d=

ferent social security systemsand have diferent approaches

to the role and extent of unionisation, worker involvement

and collective bargaining. National-level factors like this

have inspired the study of comparative human resource

management, because of concerms over the generalsabilty

‘of Anglo-American approaches to managing people,

Institutional environments come with a unique history

shaped by culture and values, traditions, habits and inter-

ests (Jafee, 2001). This means that organisations do not

behave in rationally economic ways but conform to the

social expectations of an institutional field. Organisational

behaviour, such as choices about how to manage people,

is notsimply a response to market pressures but aso insti-

tutional pressures (Paauwe and Bosele, 2007). Conform-

ing to the expectations ofthe field helps organisations to

gain legitimacy and increases the likelihood of survival

(Greenwood and Hinings, 1996).

In institutional theory, the mechanism that explains why

organisations lookalike isisomorphism (DiMaggio and Pow-

ell, 1983), which manifessin three ways ~ coercive, mimetic

and normative isomorphism, Coercive mechanisms involve

‘employment legistation and the role of government in bus-

ness organisation, Recent government interes in the ways

that banks operate is an example. Mimetic mechanisms

refer tothe imitation (miming) of competitors. A multina-

tional corporation, for instance, that sees its competitors

running talent programmes and whose current and pro-

spective employees are looking for talent programmes wil

feel under pressure to respond even though there may not

bea clear business case To some extent, talent management

could be a fashionable rather than a rational response. Nor-

‘mative isomorphism is shaped by the influence ofthe pro-

fessions on organisations. Different professions, for example

finance, engineering, and law, have their own norms about

how knowledge is created and transmitted and about

career structures. Aspiring tax consultants or lawyers will

have views about the career development that employers

should be offering, and those views may push the organisa-

tion towards some sort of talent strategy. Failure to respond

‘would make the organisation look out of synch in the sector

and tarnish ts legitimacy.

Furthermore, all business sectors contain executives

who move between firms and who meet at informal and

TALENT MANAGEMENT: CRITICAL PERSPECTIVES 285)

formal events. As the network of interactions between

people grows, then the occurrence of rationalised myths

increases. These myths then diffuse throughout a sector

through ‘relational networks’ (Greenwood etal, 2008: 3)

What is deemed as rational, however, is set by the intitu-

tional context. What appears as rational in one sector is

not necessarily seen as rational in another. Furthermore,

hile practices can differ widely between sectors, they can

also differ widely within sectors when the same sector is

viewed across national borders. Most developed countries

have a university sector, for instance, but there are big dif

ferences in the ways that universities operate between

‘countries and the differences are caused by political and

cultural overlays

Whether talent management has become an insti

tution is itself debateable. It perhaps has further to go

before it becomes one, but in sectors where ic is widely

implemented without much thinking itis getting close

to becoming one (Zucker, 1983). This insight from insti

tutionalism tells us that, in some sectors, talent man-

agement, which is essentially an idea about how people

should be managed, is probably adopted:

‘eto gain or maintain legitimacy;

+ toappear rational and normal; and

«© to offer something different from other organisations

but also to conform with other organisations (Sahlin

and Weddin, 2008).

@ Class Acti

Look on the internet for examples of talent pro-

{grammes in multinational companies.

» What are the philosophies behind the programmes,

what areas of the workforce are covered, and what,

development programmes are available to people

intalent pools?

a oe eg

Celebrity society

Another critical view of the spread of talent manage-

ment relies on ideas from the notion of celebrity society

(van Krieken, 2012) and the ways that it has extended to

organisations. Increases in the pay and rewards given to

chief executives have outstripped those given to other

employees, and alongside this many chief executives have

sought andJor achieved corporate celebrity status. With

constant pressure to deliver business improvements and a

media hungry for stories, organisations are always looking

cout for success stories and individuality. Corporate insid-

ersare often assumed to be too far steeped in problematic

286 HRM AND CONTEMPORARY ISSUES

organisation cultures to risk at the top, and so outsiders

are often preferred. Attracting attention, making bold

decisions, publicising successes, winning prizes and awards

are now an indispensible part of life at the top and have

become part of what it means to be talented.

‘Alongside the increasing importance of celebrity, the

‘management of large organisations has become more

complex. Intemational and global scale operations are

‘more common, labour markets are much more fluid, capi-

tal is more easily available, and the power of investors is

stronger. Talent management is logical response to man-

aging complex situations; find the smartest people and set

them to work on taking the organisation forward, Those

who pass the talent auditions and perform wel will also

become minor celebrities on the organisational stage and

maybe, someday, a big’star: Talent pools symbolise what

‘one has to do to be successful in an organisation. They

are a touchstone, a reference point, for revealing one's

identity in an otherwise large, complex and anonymous

organisation,

Van Krieken (2012) argues that in celebrity society

there is an oversupply of information and a scarcity of

attention. Creating talent pools is a way of concentrating

executive attention on a few people and interpreting per-

formance through them rather than dealing with a mul-

titude of employees and the countless interactions that

‘occur between them. Talent management can be seen

therefore as a way of helping to simplify the management

cof very complex situations.

5f0P.4, Think about the reasons for the growth

.°,, and spread of talent management given

|) above, Which reason(s) do you think is

r3' the most compelling and why? To help

you do this, you might think about and

discuss this statement: Talent manage-

ment is much more about top managers

playing-out their own visions of what

high performers should be doing than it

is about making a measurable difference

to organisational performance,’

IDENTIFYING TALENT

Nine-box grids

Talent is usually seen as a combination of recent and

‘current performance together with future potential, A

‘common method of visualising a workforce on these

dimensions is through a nine-box grid where the nine

boxes are combinations of three levels of performance and

three levels of potential ~ see Figure 12.1. na large organi-

sation, the grids are completed at departmental and local

levels and/or by functional areas. ey re then aggregated

upwards to provide talent analysts and planners with a

picture of organisational talent across the organisation by

level and area. The end-of-chapter case study shows how

2 large company used the nine-box approach and the sys-

tems that support it.

In Figure 12.1, each box is labelled according to the

assessment of performance and potential based on the

criteria used in the organisation, The implications of

being located ina particular box depend on the organi-

sation’s HR policies. Only occupants of the ‘super-

star’ box might be deemed ‘talented’ in a very elitist

scheme. ‘Stars’ and ‘future stars’ might be included in

42 more inclusive but still elitist scheme. The majority

of employees are likely to be located on the first and

second rows.

Grids of this type can be problematic because indi

vidual performance can be erratic for reasons such as

changing personal circumstances. Even though perfor.

mance can be evidence based, it is also partially ilu-

sory, and underperformance is perhaps more likely to

be recognised than excellent performance. In complex

and fast-changing business conditions, assessments

of high potential can be shortived as environmental

changes act to make them redundant. Effective grid

use also requires open conversations with people, for

example asking questions about their intent to leave the

organisation.

The grid approach is highly managerial and performa-

tive. Ie utilises the concept of human value which in this

instance assumes that different employees posses dif-

ferent values because they are capable of rendering dif-

ferent levels of service in the future. Borrowing directly

from economics, the value of people is defined as the

expected value of the services that they will deliver to

the organisation in the future. Future services are a func-

tion of aperson’s productivity their transferability, their

promotabilty, and the likelihood that they will stay

with the organisation (Flamholtz, 1999). In economic

terms, the human value of an employee depends upon

the value of what he/she could do in the coming year

or two, Each of the four levels of service represents a

‘service state’ (Famholtz, 1999: 180). For example, an

employee who stays in his/her current position occu-

pies one service state; an employee who is promoted to

a higher position, and in theory who gives more value to

the organisation, occupies a different service state. The

nine-box grid is a qualitative way of capturing talent by

scanning actoss a workforce and allocating employees to

different service states according to their perceived value

to the organisation,

‘TALENT MANAGEMENT: CRITICAL PERSPECTIVES 287

Promotability timescale

eee

‘Uncertain Medium term Short term

Potential star Future star ‘Superstar

a Combines under Solid performance and | Outstanding performance

ey performance with high shows high potential inall areas and shows

p potential. high potential

Promising ‘One to watch ‘Star

promotable | Peformance improvement | Solid perormanceand | Excellent performer and

| needed to confirm showssome potential | shows some potential

potential.

Under performing Reliable performer Excellent performer

Not

promorable |) Peformance management Steady-state Keep

interventions needed.

Underperforming Good ‘Outstanding

fs

Figure 12.1. Example nine-box grid

Biasing factors in talent identification

A limitation of manageralist methods such as the grid is

that they mask a lot of irational behaviour that affects,

how employees are viewed. Sources of bias are summa-

ised below.

Physical differences

A small but noticeable effect comes from personal attrac-

tiveness. Better-looking people tend to earn more than

others. This does not apply everywhere, but it does in

sectors where looks are more likely to enhance productiv

ity, such as sales or consulting, Indeed, the best-looking

people are more likely to self-sort into occupations where

their looks will work to their advantage (Hamermesh and

Biddle, 1994). Physical height also correlates with career

success and higher earnings (Judge and Cable, 2004). This

is explained by nutrition, which correlates with height and

cognitive abilities (Schick and Steckel, 2015), although

apparent height/earnings effects may be accentuated by

Performance rating,

very short people sorting into low-pay occupations (Lun-

berg, Nystedt and Rooth, 2014).

Upwards influence and liking

‘A supervisor's ratings of promotabilty are affected by the

upwards influence tactics used by subordinates such as rea-

soning, ingratiation, assertiveness, and bargaining, Trying to

influence supervisors, however, is a risky game for subordi-

nates because they do not know how supervisors will react

(Thacker and Wayne, 1995). Upwards influence tactics are

likely to vary across cultures and may be related to power-

distance and individualism-collectvism (Terpstra-Tong and

Ralston, 2002). Impression management is a closely related

concept, and men and women have different approaches to

the use of impression management, which leaves younger

‘women in particular at a disadvantage (Singh, Kurnra and

Vinnicombe, 2002). Selfpresentation is a powerful tactic

in the workplace, and people who exhibit political sil will

progress faster than those who do not (Blickle et al, 2012).

288 HRM AND CONTEMPORARY ISSUES

In addition to influence tactics, performance ratings are

highly correlated with the extent to which raters lke the

people they are rating (interpersonal affect). Research

shows a substantial overlap between rater liking and per-

formance rating, although this is to some extent a refiec-

tion of true differences in ratee performance (Sutton et al,

2013; Varma and Pichler, 2007). A plausible explanation is

that raters tend to like high performers more than others.

‘In the News Class matters!

‘Top law and accountancy firms in the UK are ‘side-

lining’ working-class job applicants in favour of can-

didates from privileged backgrounds - according to

‘a survey published in 2015. In their search for talent,

firms used criteria such as the amount of travelling

that candidates have done, their confidence, and a

‘posh’ accent, These and other factors were more

likely seen in graduates from ‘top universities where

recruitment was focused. Graduates from working-

class backgrounds who are less likely to travel and

be involved in prestigious social events were less

likely to be recruited.

Read more at http://www.bbe.co.uk/news!

education-33109052.

Gender

Gender isan important variable in leadership research and

is a source of potential bias within talent management.

Women continue to be disadvantaged at work (Acker,

2012; Calas and Smicich, 2006; Chartered Management

Institute, 2014) and tend to lose out in terms of an endur-

ing gender pay gap, an association with lower status and

less stable part-time or flexible work (Durbin and To

son, 2014; Wilson, 2013), and both horizontal and vertical

segregation of obs. Horizontally, men and women tend to

be located in different types of work that become associ-

ated with a particular gender, typically to the detriment

‘of work that is seen as largely populated by women, Verti-

cally, there are far more men at the top of organisations

and the professions than women. Even very senior women

tend to lose out through political processes in organisa-

tions, which can became a double-bind since politcal

behaviour is seen as congruent with a male norm and thus

deemed inappropriate for women (Doldor, Anderson and

Vinnicombe, 2013).

‘Acker (1990, 1992) suggested that inequality is inher-

cent in organisations that are themselves gendered. Organi-

sations are seen to have an inherent preference for male

workers who ate typically seen to be'‘unencumbered!’ and

thus ideal workers. Acker (1990, 1992) identified four ke

processes through which organisations remain gendere

‘The first, gender divisions, refers to notions of horizont

and vertical segregation noted above. The second refe

to the manner in which ‘symbols, images and forms «

consciousness’ (Acker, 1992: 253) produce and reproduc

a gendered order. Thus, language and communicatio

in organisations typically rely on notions of masculi

ity and making oneself heard, to the advantage of me

The third process, interactions between organisation

stakeholders, works to reinforce images of gender’ (Acke

1992: 253) and ensures that hierarchies supporting an

highlighting male dominance are maintained. The fourt

process, ‘internal mental work’ (Acker, 1992: 253), relate

to actions at both an individual and collective level ch:

adhere to (or otherwise) gender-appropriate person

with all four processes working together to reinforce

gendered organisation ‘substructure’ (Acker, 1992: 255

‘Women in modern organisations (fluid, focused on ind

vidual success) may be at an even greater disadvantag

through these four processes, since career structures an

ascendancy through the ranks are now less formalised an

more subject individual self-promotion and line mar

ager sponsorship (Williams, Muller and Kilanski,2012),

Such sel and line manager promotion is relevant t

talent management that focuses on leadership taler

and high leadership potential (De Vos and Dries, 2013

Talent identification processes, therefore, struggle to b

gender-neutral (Famdale, Scullion and Sparrow, 201(

and are particularly prone to gender bias. The CIPD (201

‘conducted a mixed-method study of talent managemer

from the perspective of the talent managed and foun

that the manner in which talent is identified is increa:

ingly reliant on opaque processes and aspects such

social networking, Other research supports this view an

Points to the central role of informal networks in taler

Progression decisions (Handley, 2014; Tansley and Tietz

2013; Williams et al, 2012). However, women - particular!

those in part-time employment (Durbin and Tomlinsot

2014) - do not benefit from mentors and networks to th

same extent as men (Al Ariss, Cascio and Paauwe, 2014).

On the basis of in-depth interviews with ‘high

Potentials, Ibarra, Carter and Silva (2010) conclude

that women are far les likely than men to benefit fror

mentoring, largely because their mentors tend not to b

as senior and, therefore, are less influential and les likel

to open up Key network links for women. Linehan an.

Scullion (2008) identified similar difficulties facing senic

female managers who were found to miss out on opporet

nities for promotion due toa lack of effective mentorsan,

sponsors and a more limited access to powerful network

compared to male managers. The female managers i

their study explicitly referred to difficulties in succeedin

ina ‘man’s world’ (Linehan and Scullion, 2008: 29) high-

lighting the continuing relevance of Acker (1990, 1992,

2012) model. Thus, women are les likely to benefit from

mentoring and useful networks which may have a detr-

rental impact on their chances of being identified and

included in talent pools and of progressing upwards.

‘As outlined above, talent management tends to focus

con leadership or managerial talent. The notion of man:

agement or leadership itself, however, can be seen to be

gendered because ofan enduringnotion of heroic’ ormas-

culine leadership (Billing, 2011; Broadridge and Simpson,

2011; Ford, Burkinshaw and Cahill, 2074), thus calling nto

question the equity of talent management approaches,

‘Makeld et al, (2010) found evidence of two processes in

global talent management; ‘online’ (characterised by

recorded and demonstrated prior experience and feed-

back) and ‘offline’ (more furure-oriented) processes. The

second, offline, stage was seen to be particularly limited

due to cultural distance between HQ and subsidiaries

and homophily or similarity bias (the tendency to sup-

port or promote those who are similar to ourselves) and

ako because of network position (propinquity). People

who were included in more central networks, who were

loser or more visible to, and perceived as similar to, cen-

tral decision-makers were more likely to be included in the

talent pool. This has obvious implications for gender bias;

women are less likely to benefit from powerful or central

informal networks and, because they are less likely to

comply with a masculine leadership construct, are more

likely to be disadvantaged.

‘Ackers nation of the ideal masculine unencumbered

worker permeates other aspects of the talent manage-

ment process. Festing, Knappert and Kornau (2015), for

example, ater research across five countries, concluded

that global performance management (one potential ele-

‘ment of talent identification and selection) is more closely

aligned with the preferences of male managers. Such

processes are reinforced through the exposure of those

included in talent pools to strategic language’ and ways of

talking to which the excluded are seldom if ever exposed.

This can become a virtuous circle, whereby those identi

fied as talented become perceived by others as ever more

talented (as they are using strategic language) and, indeed,

conduct identity work to reinforce this position (Tansley

and Tietze, 2013). As women are les likely to be identi

fied as talent and less likely to be senior managers, their

exposure to such language will be restricted and their dis-

advantage potentially intensified.

Five aspects or elements of talent management that

have an impact on the likely extent of gender bias have

been observed in German media organisations (Festing,

Kornau and Shafer, 2014). Gender bias was deemed more

likely in an organisation that has:

TALENT MANAGEMENT: CRITICAL PERSPECTIVES 289

a prevailing masculine talent/management stereotype:

«hierarchical or vertical career orientation, with a model

of linear career paths;

‘© greater focus on technical (rather than personal devel-

‘opment) sil in talent development programmes;

an elite (rather than inclusive) approach to talent

management;

amore ‘discriminatory’ talent management approach,

for example male-dominated talent selection teams

and opaque processes.

Thus, talent management, whist potentially adding value

for organisations, may have several unanticipated and

potentially undesirable consequences for women.

® ical Thinking 1

‘As you can see, there are some serious biasing

effects that might be introduced into talent pro-

‘grammes simply because of a person's gender and

the idea of the gendered organisation. We would like

you to think about the following questions:

Questions

1. To what extent do you think that gender is a real

issue in the faimess of talent identification?

2 Do you think itis possible to overcome gender

bias in talent management programmes?

‘8. What practices could organisations put in place

to minimise gender bias?

4. Can you suggest any additional factors to the five

identified by Festing and colleagues (2014) that

‘would accentuate gender bias?

——_——

Talent identification in multinational

companies

Inaddition to the general problems in talent identification,

some issues arise specifically in MNCs. One obvious differ

fence is the interaction of management styles emanating

from the parent country and the host countries in which

subsidiaries are based. Subsidiaries in different countries

are influenced by different institutional effects (see above)

that push towards isomorphism and in effect push to keep

staffing systems apart. Vo (2009), for instance, found that

Usand Japanese MNCs operating in Vietnam followed dif-

ferent staffing polices. The American firm was more wil-

to employ locals in management roles and mirrored

its home country practices by fast tracking high potential

staff. In contrast, the Japanese MNC followed a traditional

‘model of relying more on expatriate managers long se

vice and late promotion ifjustfied. The Japanese firm also

290 HRM AND CONTEMPORARY ISSUES

effectively restricted locals to going no further than mid-

dle management positions.

Analysing the British takeover of a French firm, Bousse-

baa and Morgan (2008) found major incompatibility

problems. French managers saw the British approach of

‘measuring performance and potential as leading to a ‘rat

race’ in contrast to a much preferred esprit de corps. The

whole philosophy of talent identification was different in

France and grounded in the idea that a managerial elites

developed outside the firm in the grand écoles system. A

British approach of seeking potential talent clashed with a

French approach of employing proven talent.

Selection for talent pools in MNCS is, as well as per-

formance, influenced by cultural diferences, similarities

(homophily) between high performing employees and

the talent decision-makers, and the network position of

staffsuch that higher visibility increases the chances of ta

tent recognition (Make, Bjorkman and Ehrnrooth, 2010).

‘Another specific barter isthe failure of MNCs to manage

talent in subsidiaries, which is aggravated by managers in

subsidiaries suppressing talented staff in an effort to keep

them in the subsidiary (Mellahi and Collings, 2010).

Large and fast-moving economies

Large and fast-moving economies such as Brazil, Rus-

sia, India and China face a particular challenge arising

from the type and availability of the human capital open

to them. Concerns centre mostly around country-level

effects such as the mobility of talented people (broadly

defined as people with skills and qualifications). For India

and China in particular, Doh et al. (2014) identified four

uunderiying talent issues:

1 Population growth and shifts in the working age that

will ‘exacerbate generational differences within a

workforce’ (227). Expanding university education is

producing more graduates, but companies face chal-

lenges responding to graduate expectations. Talent

programmes will need to accommodate both local

and expatriate ways of thinking about management.

2. Specialist skills could be in shore supply despite rising

university output.

3. The nature of work in India and China is chang-

ing, moving from labour-intensive to more capital-

intensive and knowledge-based sectors. This requires

far more interaction with other organisations and

other countries, so cross-cultural competences will be

ata premium,

4 Increasing interactions will push for convergence of HR

systems, including talent management. Sharp differ-

‘ences in talent practices between Western and Eastern

firms could be problematic.

(One of the big debates in HRM is whether it actual

makes any difference to organisational performanc

Of course, many organisations assume that it does, bu

demonstrating a link empirically is very dificult pare

for methodological reasons. However, the consenst

now is that there are links between HR practices an

organisational performance (Birdi et al, 2008; Croc

et al, 2011). The question arises, however: will the sarr

HR practices and architectures that work in the We

migrate with the same effects to very different cultun

and economic conditions? Or are different HR archite

‘tures required? What is becoming clear is that whatev

HR systems are used, they have to be matched with qua

ity skil, expertise) of the local labour and the strateg

of the firm (Li etal, 2015). Successful talent systems w

also need to address local cultural norms such as coh

siveness and collaboration in China (Zhou et al, 2013

employees who can act as boundary spanners such :

Japanese immigrants in Brazil (Furusawa and Brewste

2015), and running separate HR practices for manageri

and non-managerial employees where needed (Fey an

Bjorkman, 2001).

‘A central question in cross-country studies of tar

management is how the concept varies between cout

tries. On what dimensions might ideas about talent di

fer? Inclusion versus exclusion seems an obvious on

‘Attitudes to age may differ - can older people till be re

ognised as talent? Expectations of the jobs that wome

should do and the roles that are appropriate for them m:

also differ starkly between West and East. Views towart

sourcing talent from inside and outside may also var

However, we suggest that differences within countrie

wherever you look, will be greater than the differenc

between countries.

‘A comparative study of India and China found th:

both were comfortable with an elitist approach in con

‘mon with the West; talent was seen in terms of youn

promotable people, but the extent to which firms wou

see the need for distinctive programmes to manage te

cent may diffe. Cooke et a, (2014) concluded that talet

‘management has to be contingency-based such that tt

particular design ofa programme will be contingent upc

local customs, norms, and HR practices.

TALENT MANAGEMENT: THE

DARK SIDE

Sources of bias in talent identification processes a

one example of the ‘dark side’ of talent managemer

Figure 12.2 summarises some of the unanticipated cons:

quences for employees who are included in or exclude

from talent pools,

Included in the talent pool

# Silo mentality

© Political and obtuse

source: Adapted from Handley (2014)

Potentially undesirable consequences for those who

have not been identified as talent might include feelings,

ofinsecutity because they fel less valued, disappointment

particularly if individuals have been rejected, or frustra-

tion, all of which could have a negative impact on their

performance (Ford, Harding and Stoyanova, 2010). Those

included in the talent pool might also experience negative

consequences: they may feel that they are being treated

simply as a ‘resource’ (and so dehumanised) or, alterna-

tively, they may feel that promised opportunities have not

materialised, causing individuals to become disengaged

(Mellahi and Collings, 2010; Huang and Tansley, 2012;

Vaiman et al, 2012).

The processes through which talent is identified and/or

selected are a key contributor to such feelings through the

biasing effects identified earlier in this chapter. In addition,

team working may become problematic in elitist work

cultures (Meliahi and Collings, 2010; Thunnissen, Boselie

and Fruytier, 2013), Divisional, regional, or local manag:

cers may also have a vested interest in retaining their own

talent and not putting their better performing or high

potential people forward for central talent development

(Farndale, Scullion and Sparrow, 2010). Political behaviour

amongst those who might potentially be included in the

talent pool, in addition to their line managers, may create

significant bartiers to effective implementation of talent

Disengagement ifno challenging projects

+ Selffulilling prophecy through exposure to

better leadership and strategic language

Process

Figure 12.2 The'dark side’ of talent management

‘TALENT MANAGEMENT: CRITICAL PERSPECTIVES 291

Not included in the talent pool

~ Insecurity, reduced performance

Frustration

Both: dehumanisation

© Elise culture, teamworking difficult

‘© Talent identification bias,

management and intensify unanticipated consequences

for both the individual and the organisation (CIPD, 2010;

Huang and Tansley, 2012; Malik and Singh, 2014).

CONCLUSION

Talent management is an. evolving and complex field

that is fraught with political overlays and interests. Some

organisations have explicit talent programmes; others

avoid explicit programmes but maintain ‘hidden’ talent

lists of staff and others avoid the practice altogether. The

reasons why organisations adopt @ particular approach

ate mired in assumptions about good leadership, what it

Jooks ike and how leaders should be developed, and each

business sector has its own set of influencing factors that

govern the extent and form of talent initiatives. Despite

the investments that many organisations make in talent

programmes, their effects on business performance are

not well understood, For many organisations, talent pro-

grammes are an act of faith rather than a demonstrable

influence on performance. The reasons why some people

are identified as talent, the effects of talent programmes

cn performance, and the ways that organisations evaluate

the success of talent programmes are important topics for

future research,

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5825)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Non Recognition of Print Advertising Emotion Arousal and Gender EffectsDocument20 pagesNon Recognition of Print Advertising Emotion Arousal and Gender EffectsRameesha NomanNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 and 3Document56 pagesChapter 1 and 3Rameesha NomanNo ratings yet

- Learning Strategy & Process 300621Document13 pagesLearning Strategy & Process 300621Rameesha NomanNo ratings yet

- Larkana Sat Vi ResultDocument1,862 pagesLarkana Sat Vi ResultRameesha NomanNo ratings yet

- Khairpur Sat Vi Result-2Document1,095 pagesKhairpur Sat Vi Result-2Rameesha Noman100% (1)

- Sukkur Sat Vi Result-2Document624 pagesSukkur Sat Vi Result-2Rameesha NomanNo ratings yet

- Assignment No 2Document4 pagesAssignment No 2Rameesha NomanNo ratings yet

- Kambar Sat Vi ResultDocument775 pagesKambar Sat Vi ResultRameesha NomanNo ratings yet