Professional Documents

Culture Documents

L2 Tense and Time Reference

L2 Tense and Time Reference

Uploaded by

Bách Tất PhanOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

L2 Tense and Time Reference

L2 Tense and Time Reference

Uploaded by

Bách Tất PhanCopyright:

Available Formats

Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages, Inc.

(TESOL)

L2 Tense and Time Reference

Author(s): Eli Hinkel

Source: TESOL Quarterly, Vol. 26, No. 3 (Autumn, 1992), pp. 557-572

Published by: Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages, Inc. (TESOL)

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3587178 .

Accessed: 21/06/2014 12:26

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages, Inc. (TESOL) is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize,

preserve and extend access to TESOL Quarterly.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.158 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 12:26:38 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

TESOL QUARTERLY,Vol.26, No.3, Autumn1992

L2 Tenseand TimeReference

ELI HINKEL

The OhioStateUniversity

The meanings and formsoftensesarecomplexand oftendifficult

fornonnativespeakersto acquire.The conceptsassociatedwith

timewhichdifferamonglanguagecommunities can presentan

additionallevel of complexityforlearners.In a survey,130ESL

studentswereaskedto describethemeanings ofEnglishtensesin

termsof timeconceptsused in ESL grammartexts.The results

suggestthatspeakersof Chinese,Japanese,Korean,Vietnamese,

and Arabic associatedifferent temporalrelationships withthe

termsrightnow, present,and past thando nativespeakers.An

implicationof thisfindingis thatgrammarteachingthatutilizes

descriptionsoftimeacceptedin English-speaking communitiesto

explainusagesand meaningsof Englishtensescan producea low

rateoflearnercomprehension.

Few ESL researchersdoubt thatlearners'L1 conceptualizationof

time and lexical and/orgrammaticaltime markershave an impact

on their acquisition of English tense. In all languages, time is

referred to in some fashion. However, time attributes (i.e.,

perceptual,conceptual and culturaldivisionsof time) differamong

societies. One obvious example of thisis the boundaryof a day. In

nonsecularMuslimand Jewishcultures,days begin at sunsetand not

at midnightas in Westerncivil convention.On the otherhand, the

Japanese considersunrisethe beginningof a new day.

Time attributesare bound to reflecton thesystemsthroughwhich

languages representthese divisions (Levinson, 1983). Linguistic

referencesto timeattributescan take manyforms:Some languages,

such as Chinese and Japanese referto time lexicallyby employing

nouns and adverbs; others,like English, also utilize grammatical

references(i.e., verb tense). If both Li timeattributesand theirlin-

guisticreferencesdifferfromthose in L2, learnersmay findthem-

selves in an environment wheretheycannotpick out thetemporalat-

tributeto whichtenseis a grammaticalreference(Donnellan,1991).

English aspect can be morphologicallymarked as well. For

example, theverbs in both sentencesHe runsand He is runningare

557

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.158 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 12:26:38 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

in the presenttense. However,the presentsimplerunscarries

iterative(or habitual)implicature,whereas -ing in the second

sentenceimpartsprogressive implicature to theverb'spresenttense

meaning. Aspects, which Comrie (1976), Lyons (1977), and

Richards(1987)viewas additionalfeatures oftimedeixis(or means

of locating events in time), can present the same potential

dichotomy betweenthetimeattributable and itsreference.

In orderto gaininsightintohow ESL learnersacquiremorpho-

logical tense, numerousstudies have examined the order of

morphemeacquisition(e.g., Andersen,1977; Bailey,Madden, &

Krashen,1974;Dulay & Burt,1974;Larsen-Freeman, 1976;Makino,

1979;Pienemann,1985). In addition,a greatdeal of researchhas

been devotedto ESL learneracquisitionof tenseand morpheme

meaning (Andersen,1983; Bailey, 1989a, 1989b; Hatch, 1978).

Whereassomespecialistson languageand tenseacquisitionbelieve

thatlearnersacquire tensemeaningsbeforetheirmorphological

forms,othershold theoppositeview. This paper willaddressthe

issue of whethernonnativespeakers(NNSs) who have received

extensiveL2 trainingand have achieved a relativelyhigh L2

proficiency intuitivelyperceiveEnglishconceptualization of time

and itsgrammatical references to deictic(orindexical)time,thatis,

morphologicaltense,in ways similarto native speakers(NSs).

Anotherfocus of this study is NNSs' perceptionsof English

aspectualimplicature.

ESL teachersandL2 researchers recognizethatEnglishtensesare

to acquire(DeCarrico,1986;Richards,1981;Riddle,1986).

difficult

Guiora(1983) notesthatspeakersof Hebrew encounterdifficulty

mastering themeaningsand usagesof severalof theEnglishpast

tenseswhich,to them,seem redundantand withoutan easily

discerniblefunction.He alsonotesthatspeakersofChinesemaybe

faced withestablishing an entirely new hypothesis of how timeis

used and referredto. SharwoodSmith(1988) indicatesthathis

Polishstudents had difficulty relatingtothepastprogressive and its

form.Richards(1981) discussesthe complexityof introducing

Englishprogressive tensesand theirexplicitand impliedmeanings.

DialectvariationsevenwithinEnglish-speaking societiesmakefor

differences

significant in tenseusageand meanings(Leech,1971).

Coppetiers(1987),who conducteda studyof highlyeducated

NNSs withnear-native proficiency in French,foundthatwhereas

theyhad obviouslyacquiredtenseforms, theirperceptions oftense

meaningswere not NS-like.Coppetiers contends thatthe NNSs'

perceptionsof tense meanings were strongly affected by tense

meanings in the L1 so that the speakers of Romance languages

interpreted themeanings ofFrenchtensesdifferently fromspeakers

of Germanicand tenseless languages(pp. 560-561).

558 TESOL QUARTERLY

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.158 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 12:26:38 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

To date,whetherspeakersof themanylanguageswithoutmor-

phologicaltensescan fullymasterthe Englishverbal systemof

tenseshas notbeendetermined. Richards(1973)observesthatESL

omissions

learners' of tense markers representa damagingand

confusing typeof error.

Chappel and Rodby (1983)notethatESL

students'tense-relatederrorsoften detract from the overall

comprehensibilityof theirtext.Theyfurther mentionthatdespite

thefactthatverbtensesoccupya prominent rolein theteachingof

ESL, studentsseemto chooseverbtensesarbitrarily. In theirview,

tenseerrorsmayresultfromthelearners'lack of understanding of

theimpactoftenseon text.

BACKGROUND: PRAGMATICS OF TIME AND TENSE

The issueoftherelationship betweengrammatical tenseandtime

and the acquisitionof tense systems *is complex. Whethera

connectionexistsbetweenthedetailedmarkingof timein English

and itsmorphological tenseas a grammaticalcategoryhasnotbeen

establishedwithcertainty. Comrie (1985) mentionsthatvarious

culturalgroups "have radicallydifferent conceptualizationsof

time"(p. 3) and onlysomemeasuretimeand occurring eventswith

exactitude.Fillmore(1975) notesthat,in mostlanguages,lexical

markers,such as today,tomorrow, and yesterday,can referto a

varietyoftimelengths withina relevant

span.Theserelevant spans,

however,differfromone languageto another.Levinson(1983)

claimsthatin "languageswithouttruetenses,forexampleChinese

or Yoruba"(p. 78), theconceptof timeis realizedthrough adverbs

and implicitand contextual assumptions.SoutheastAsianlanguages

require a strictdiscourse frame which delineates time and,

therefore, thetimereference.

The numerousstudiesof the meaningrelationships in English

betweenattributeand reference-thethingand its name-have

demonstratedthat they are vague (Bach, 1981) and language

specific.Kripke(1991) viewsnotionsof meaningsas "determined

by theconventions of thelanguage"whichcan be treatedonlyin

conjunction withtherelatedlinguistic phenomenaof thelanguage

(p. 84). Bach (1981)advancesthisargument that,in orderto

stating

be understood,the speakerand his audience musthave mutual

contextualbeliefs.Linguisticmeaningsof tensealso includethe

mutualbeliefsand sharedperceptions of themembersof a speech

community. The expression ofsuchbeliefsandperceptions maynot

be sharedby membersofotherspeechcommunities (Searle,1979).

As Donnellan (1991) notes,if descriptionsof time are used

thesubjectstowhomthesedescriptions

referentially, areaddressed

L2 TENSE AND TIME REFERENCE 559

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.158 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 12:26:38 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

are thusenabled to "pick out" (p. 60) the referencesand their

attributes.However,if the referencedoes not fit the subjects'

perceptionsof the attribute, theymay be unable to establisha

correspondence between them.

For example,if theNS instructor statesthatthemorpheme-ed

markstheverbforpast simpletensebut thestudent's conceptual-

izationofpastdiffers fromtheinstructor's, thestudentmaynotuse

thismorpheme inthecontexts wheretheinstructor would.Learners'

abilitiesto establishthereferential relationships between L2 time

deixis,tense, and morphological markers necessarily affects their

perceptions ofthemeaningsand functions of tensemorphemes.

Recanti's (1991) availabilityprincipleassumes that linguistic

meanings must be available or accessible to our "ordinary,

consciousintuitions" (p. 106).Becausetime-span conceptualizations

and theirlexical referencesdifferfor NSs and NNSs, English

grammatical references to timemay not be readilyavailablefor

pragmaticinterpretation by speakersof tenselesslanguages.If this

is thecase,morphological timereference meaningof

(i.e.,linguistic

tense)may notbe accessible to thesespeakers' conscious intuitions.

Anothercomplication is thateven developedmorphological tense

structures in twolanguagesmaydiffer greatly(Fillmore,1975).

Levinson (1983) sees English time referenceas calendrical

reckoning and observesthatmostAmerindian languages,Japanese,

and Hindidifferfromit and one anotherin namesand lengthsof

days and time spans. In his briefexamination of how the time

attribute corresponds to tense,Levinsonmentions thatinlanguages

withtense,sentencesare anchoredto a contextby morphological

tense,whereasotherlanguagesutilizeotherlinguisticand social

meansof contextual anchoring. If mutualcontextual beliefs(Bach,

1981) and calendrical time deixis(Levinson,1983) necessaryfor

are

picking out a time attribute and its morphologicalreferencein

English, NNSs lacking intuitions and access to knowledge

associatedwiththeEnglishtimedeixisand linguistic tensemayface

in

problems using and interpreting English time references.

Usually,instructors teachtensesby presenting rules,explaining

the meaningsof tenses,and by identifying the timedeixis and

lexicalcontextsin whichcertaintensesare called for(Eisenstein,

1987).Such presentations are usuallyaccompaniedby exercisesin

whichthestudentsare expectedto applytheinstructor's explana-

tions.In orderto do so successfully, thestudents haveto perform a

seriesof tasks.Theyneed to be aware of thelexicaland syntactic

markers oftimeandtheirenvironments inthesentence, understand

theirmeaningsand implications, analyzethemfortimeand tense

560 TESOL QUARTERLY

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.158 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 12:26:38 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

referenceand aspectimplicature,pickoutone ormorecorrespond-

ing auxiliariesor morphemes, put themin therelevantform,and

producea correctverbalstructure.In thisstudy,ESL students

were

asked in a questionnaireto reversethisprocessand describethe

meaningsand implications whichtensesand aspectshaveforthem

through the reference terms associatedwithEnglishtimedeixis.

(The descriptions Englishtime deixisand the framework

of of

temporality were adopted followingLeech, 1971, and Comrie,

1985.)

METHOD

Questionnaire Design

In the questionnaire, the studentswere asked to describefour

sentencesforeachofthe8 Englishtensesexcludingfuture, a totalof

32 sentences:4 present(presentsimple,presentprogressive, pres-

entperfect,and presentperfectprogressive) and 4 past (past sim-

ple, past progressive,past perfect,and past perfectprogres-

sive). If responsesfor2 sentenceswiththesame tenseand aspect

differed, theywereaveragedindependently fortenseandaspect.In

orderto circumvent theissue of therespondents' possibleconfu-

sionwhenperforming therequiredtask,responsesto thefirst2 sen-

tencesper tensewere consideredinvalidand excludedfromdata

analysis.

In the questionnaire, timeattributesand references were listed

withtheimmediatepresentfirst, moving back to the pastperfect,

whichis themostdeicticallydistantfromthepresentmoment.To

assurethatthetensedescriptors wereaccessibleto theNNSs, the

selectionof termsdescribingthemeaningsof tensesand aspectual

implicatures were chosenfromintermediate/advanced ESL and

grammartexts:rightnow (Azar, 1989) and at the momentof

speaking(Leech, 1971); in the presentand in the past (Leech &

Svartvik,1975);in the past and beforeanotherpast event(Azar,

1989;Leech,1971;Leech& Svartvik, 1975);progressive (Azar,1989;

Leech, 1971; Leech & Svartvik,1975); and repetitive/habitual

(Azar,1989;Leech & Svartvik, 1975).

The semanticsofthecontextsweremade uniform forgrammat-

ical gender,animacy,and number.The choiceof sentencesin the

questionnaire reflected severalconsiderations:

1. The verbs did not carrymomentary or durationalmeanings

(Leech, 1971) (as in,respectively,blinkor love) and onlythree

verbswereused:walk,talk,and visit.

L2 TENSE AND TIME REFERENCE 561

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.158 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 12:26:38 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2. Explicit time markers were excluded, with the exception of

before, to motivatethe past perfecttenses (Azar, 1989; Leech,

1971).

3. Vocabulary was restrictedto fewer than 100 high-frequency

words.

(See theAppendixfora listingof thequestionnairesentences.These

are presented in an order differentfrom that in the actual

questionnaire.)

The NNS and theNS controlswere instructedto choose however

many of the multiple-choiceitems theywished and thusdescribe

theirown perceptionsof temporal referencesand the progressive

and iterative/habitual aspects (Comrie, 1985; Leech, 1971;

Richards, 1981). However, true to the multiple-choice testing

tradition,almost all participants selected only one answer per

multiple-choiceselection.The firstmultiple-choiceselectionhad a

generalheading,The timeof theactionis, and requiredthesubjects

to identifythe English verb time referenceregressivelyfromthe

presentto thepast. The second selectionhad theheading The action

is and dealt with the respondents' perceptions of aspect. The

aspects addressed in the questionnaireincluded the progressive

aspect and the iterative/habitualaspect. The perfectiveaspect and

0 aspect were not included and, for the purposes of thisstudy,are

termednonprogressive/nonhabitual. (The selectionin the question-

naire correspondingto these aspects was none of the above.) The

multiple-choiceoptionsremaineduniformforall 32 sentences.

For example, the studentsread the sentenceBob is talkingto his

brother.Then theysaw two multiple-choiceselectionsfortenseand

aspect descriptors,respectively:

1. The timeoftheactionis:

a. rightnow/atthemomentofspeaking

b. inthepresentand inthepast

c. inthepast

d. beforeanotherpastevent

e. cannotdecide

2. The actionis:

a. progressive

b. repetitive/habitual

c. noneoftheabove

d. cannotdecide

The survey was administeredat the conclusion of the Autumn

Quarter,immediatelyfollowing9 weeks of instructionin daily or

thrice-weeklyESL classes. There was no timelimitforthe subjects

to respond to the questions.

562 TESOL QUARTERLY

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.158 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 12:26:38 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Subjects

Of the 130 ESL studentswho participatedin thisstudy,70

studentswere speakersof Chinese (CH); 17, Korean (KR); 13,

Japanese(JP);11,Vietnamese(VT); 12,Spanish(SP); and7, Arabic

(AR). Of the21 NS includedas controls,

19 weregraduatestudents

enrolledin variousdepartmentsat The Ohio State University

(OSU), most of whom had minimaltrainingin linguistics. The

remaining 2 were ESL instructors.

The totalnumber of participants

was 151.

AllNNS participants had beenadmittedto OSU and weretaking

classesat theuniversity.

TheirTOEFL scoresrangedfrom500 to

617, with a mean of 563. Unlike the majorityof NNSs, the

Vietnameseand somespeakersofSpanishwereU.S. resident aliens

or citizensand thuswerenotrequiredto taketheTOEFL.

The NNS subjects'ESL trainingrangedfrom4 to 18 yearswitha

meanof9.6 years.AllNNS students includedin thestudy,withthe

exceptionof the Vietnamese, had been residingin theU.S. fora

periodof timerangingfrom2.5 to 30 months,witha meanof 6.3

months.The Vietnamesestudents'residencein the U.S. ranged

from4 to 11 years,withan averageof5.7 years,and thedurationof

theirformalESL training rangedfrom9 to 33 months, witha mean

of 10.3months.

RESULTSAND ANALYSIS

The sizes of theNNS groupswerenotequalized.Afterthedata

werecompiledforeach sentence, theywereconvertedto percent-

ages. The NS valueswerecomparedto thoseforothergroups.The

temporalreference foreach tensechosenby thehighest numberof

NSs was acceptedas thetensetemporalreference againstwhichall

thoseoftheNNSswerecompared.(See Table 1.)

Onlyin thepresentprogressive werethe NNSs' perceptionsof

tensemeaningsclose to thoseof NSs. Otherwise,NSs generally

chose descriptionsof temporalreferencessubstantially

differently

from members of all groups of trained NNSs. In fact, the

differences betweenNSs and NNSs were statistically significant

(p < .01) foreach row of Table 1 exceptthepresentprogressive,

whichis not significant.-The NNSs' temporalreferenceforthe

presentprogressive rightnow/atthemomentofspeakingindicates

1 This is based on Fisher's

exact testforeach row, groupingall NNSs together.A chi-square

test forindependence would not have been appropriatedue to small cell sizes associated

with percentagesnear 0 or 100%.Since resultsfor2 sentenceswere used and averaged in

Table 1, care was takento performthe testseparatelyforeach sentence.

L2 TENSE AND TIME REFERENCE 563

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.158 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 12:26:38 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

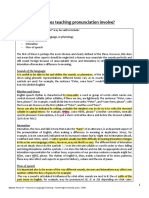

TABLE1

Reference

Temporal (%)

(N= 151)

NS CH KR JP VT SP AR

(n=21) (n=70) (n=17) (n=13) (n=11) (n=12) (n=7)

Rightnow/atthemoment

ofspeaking

Present

progressive 100 90 88 85 100 100 100

In thepresentandinthepast

Present

simple 95 40 24 38 0 83 72

Present

perfect

progressive 96 49 64 62 9 75 72

In thepast

Present

perfect 97 34 29 23 36 58 57

Pastprogressive 100 60 71 85 46 67 57

Pastsimple 100 81 88 0 55 58 57

Beforeanother

pastevent

Pastperfect

progressive 95 41 35 92 27 58 86

Pastperfect 98 61 70 85 27 67 71

that,forthem,itis themostintuitively accessibledeicticpoint.This

finding is consistent with thatof Olshtain (1979) whosecase study

showedthatevena speakerof a languagewithoutaspectacquired

the presentprogressive earlierthanothertenses.The past simple

attributeprovides the second most easily available point of

referencebecause present,past, and futureare the basic tense

meaningswithinthe conceptualizationsof linear temporality

(Comrie,1985). The unanimity of the Japanese,none of whom

perceived it to mark the past,maybe explainedby theJapanese

of

system naming a certainnumberofdaysback fromtodaywhich

can be includedinboththepresentand thepast (Fillmore,1975).

The Chineseperceivedthedeictictimeofthepresentprogressive

and past simplemost nearlyapproximating NS perceptions.In

terms of distance from the NS values, these two tenseswere

followedby the past perfectand the past progressive, thenthe

presentsimple,presentperfectprogressive, past perfectprogres-

sive,and presentperfect,respectively. thevaluesfor

Interestingly,

Koreans followed approximately thesame pattern. Vietnamese

The

values for the presentprogressive and past simpleare also the

highest for this group and are similarlyfollowed by thepast pro-

gressive.As has been the

mentioned, Japanese are somewhat differ-

ent.

564 TESOL QUARTERLY

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.158 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 12:26:38 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Withthe exceptionof the speakersof Spanishand Arabic,the

valuesfortheotherpresenttensesreflect theconsiderable difficulty

most NNSs had when choosingthe temporaldescriptions listed

withinthe selections.The past perfecttenses presentedless

difficulty, which can be partiallyexplainedby the lexical (as

opposed to grammatical)referenceof before.Levinson (1983)

indicatesthat most tenselesslanguagesprovide for lexical and

discoursesentenceanchors.In thiscase, the adverb beforeis an

explicit lexical markercongruentwith the concepts of time

reference availableto thespeakersofsuchlanguages.

intuitively

Linear conceptualizations of timemay not be commonto all

societies(von Stutterheim & Klein,1987).Amongthe6 groupsof

NNSs, onlythespeakersof Spanishand Arabicwere speakersof

languageswithdevelopedmorphological tenses.The veryfactthat

Spanish and Arabic have deictic time referenceprovides an

establishedconceptual structureand morphologicaltemporal

reference whichthespeakersoftheselanguagescan drawon when

exposedto L2 conceptualizations of timeand morphological tense.

To somedegree,theysharemoremutualconceptualizations oftime

withNSs and weremoresuccessfulin pickingout appropriateL2

timeattributes thanspeakersof Chinese,Korean,Japanese,and

Vietnamese.

The NSs' behaviorin the analysisof tense-marked temporality

demonstratesthat they appear to know that auxiliariesand

morphemesrepresent deictictimereference and were,therefore,

able to pick out themoreappropriatetimeattribute(Donnellan,

1991).Theyappearto have access to thelinguistic meaningswhich

auxiliariesand morphemes encodeinEnglish.The NNSs,however,

do notseem to have theNS-likeintuitive knowledgeofthelinear

conceptualization of time and itslinguistic references.

Morphological references to deictictimeare inextricably linked

to tense reference.If a grammaticalreferenceto temporality

impliesa deictictime,we assumethattheNNS knowsand intends

thatmeaning(Recanti,1991);thatis,we assumethatNNSs' choice

ofmorphemes impliestheirknowledgeofmorphological meanings.

Even if theNNSs' intuitive knowledgeof deictictimeattribute is

NS-likebuttheirchoiceofmorphemes is not,theirNS-likeintuitive

knowledgeofdeictictimewouldstillappearseriously flawed.

In thesecondtask,thestudyparticipants wererequestedtoassign

aspectual implicature(Comrie, 1976, 1985) to each temporal

reference oftense.The implicature oflineartemporalaspectstends

to increasethedistancebetweentheNS and NNS perceptionsof

temporality. (See Table 2.)

L2 TENSE AND TIME REFERENCE 565

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.158 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 12:26:38 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

TABLE2

Aspectual (%)

Implications

(N= 151)

NS CH KR JP VT SP AR

(n=21) (n=70) (n= 17) (n= 13) (n= 11) (n= 12) (n=7)

Progressive

Present

progressive 100 64 59 100 36 75 86

Present

perfect

progressiw 95 56 65 85 0 67 71

Pastprogressive 99 53 71 92 27 50 71

Pastperfect

progressive 96 49 65 85 27 58 43

Interactive/habitual

Present

simple 97 47 59 77 18 50 85

Nonprogressive/nonhabitual

Presentperfect 97 34 29 23 36 42 43

Pastsimple 98 47 82 62 46 42 86

Pastperfect 96 56 53 38 28 34 57

The NNSs' perceptionsof aspectualimplicatureindicatedby

theirchoiceswere also analyzedagainstthechoicesmade by the

majorityof NSs. NSs chose descriptions of aspectualimplicature

significantlydifferently(p<.01) from NNSs in every case,

includingpresentprogressive (based on Fisher's exacttest).A cell-

by-cellcomparison of same-tense values associated withtheNNSs'

perceptions of L2 aspectualimplicature(see Table 2) shows an

average declineof 7.8% compared to values associated withNNSs'

of

perceptions temporality (see Table 1). This is

finding consistent

withBailey's(1989a, 1989b) accountof NNS acquisitionof past

simpleand pastprogressive, whichnotesthattheprogressive aspect

combinedwiththemeaningof thepastpresentsan additionallevel

of complexityfor L2 learners.The NNSs' perceptionsof the

progressiveaspectweregenerally closerto thoseof NSs thanwere

theirperceptionsofthehabitualandnonprogressive/nonhabitual.

Durativeand continuative, and iterative and repetitiveaspects,in

someform,can be foundin all LUsrepresented inthedata withthe

exception of Vietnamese. NNSs whose Lis have aspect as

referential

implicature thushave access to theassociatedlinguistic

conceptualization.Chinese (Li & Thompson,1981) and Spanish

(Comrie,1976,1985) have the durativeand continuative; Korean

(Joo Hwang, 1987), Japanese(Inoue, 1984), and Arabic (Kaye,

1987) have both of

types implicature-durative and continuative,

and repetitive.

and iterative However,theaspectualimplicature in

566 TESOL QUARTERLY

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.158 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 12:26:38 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

theselanguagesis different fromthatof English-so muchso that,

as thecitedauthors indicate,itis rather difficulttodescribeinterms

of English.Vietnamese, is

however, unique in thatitdoes nothave

tensesor aspects,and itswordorderis thesole meansofindicating

grammatical relations(Nguyen,1987).

The NNS perceptionsof aspectand temporality in thepresent

perfectarethemostdistantfromthoseof NSs. Amongthespeakers

of tenselesslanguages,theKoreansand theJapanesemoreclosely

approximated NS valuesovertherangethandid theChinese,who

have onlydurativeLi aspect.In turn,thevalues fortheChinese

werenearerNS valuesthantheVietnamese. The factthattheSpan-

ishcontinuative and thesituational repetitiveare notsimilarto the

Englishprogressive and iterative (Comrie,1976,1985) is presum-

ably reflectedin thevaluesfor the Spanishspeakers.

Leech (1971) and Comrie(1976,1985) strongly be-

distinguish

tweenthebasic meaningsof tensesand thesecondarymeaningsof

aspects.The NNSs' interpretations of L2 timedeixisthatare, in

Donnellan's(1991)framework, restricted bytheirLi conceptualiza-

tionare made additionally difficult by theneed to inferaspectual

implicature.The fact that the distancebetween NNS and NS

perceptionswas greater inregardtoaspectualimplicature thanwith

temporal reference supports the earlierobservation that NNSs'

intuitions

regarding morphological referencesto deictictemporality

maynotbe fullydevelopedby yearsofL2 training.

CONCLUSION

Independentof the NNSs' perceivedmeaningsof timespans,

morphological references to timeimposeobviousconstraints on L2

learnerperformance. The factthatNNSs withextensivelanguage

training and TOEFL scoresabove 500 consistently made temporal

referenceanalysesand choices of time attributessignificantly

different fromthoseofNSs innearlyall cases can be accountedfor

by fourinterrelatedhypotheses whichrequirefurther investigation.

1. NNSs' intuitiveconceptualizations of timeare notlinearand/or

deicticand,therefore, removedfromthoseofNSs. ExtensiveL2

instruction may diminishthis conceptualdistanceonly to a

limitedextent.

2. BecauseEnglish,unlikesomeotherlanguages,requiresmorpho-

logicalreference to timedeixis,NNSs' intuitions

associatedwith

deictictensemaynotbe based on lineartemporality and mor-

phological tenseas fullyas thoseof NSs are.

L2 TENSE AND TIME REFERENCE 567

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.158 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 12:26:38 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

3. Despitetheiryearsoflanguagetraining,comparedtoNSs,NNSs

have limitedaccess to themeansof interpretingmorphological

deictictime.

4. As is apparentfromthedata fortheVietnamesespeakers,many

yearsof exposureto L2, combinedwithinstruction, mayhave a

limitedimpacton NNSs' perceptions of L2 deictictense.

The markeddifferences whichhavebeen notedbetweentheNS

and NNS perceptionsof timeand its associatedmorphologyas

describedinthetermsacceptedinL1 researchand L2 methodology

can also implythattense-related does notalwaysstrike

instruction

a familiarchordor providefora pointof reference in NNSs' con-

ceptualizationsof timeand itsgrammaticalencoding.

FOR TEACHING

IMPLICATIONS

in thisstudyare preliminary

The data presented and require

further For thisreason,onlysomegeneralsuggestions

investigation.

forteachingcan be offered.The substantial

and implications

differencesbetweenNS and NNS perceptionsof tensemeanings

seem to indicatethatNSs and NNSs view timespans and their

divisionsand measurements If this is the case, the

differently.

teachercannotassumethattheterminology and theconceptualiza-

tionsassociatedwithEnglishtimedeixisare understoodby NNS

studentsinthesamewayas theyareunderstood by NSs. Specifical-

ly and thoroughlyexplainingEnglishtimeattributes and notions,

thereference termsused to describethem,and theirimpacton the

meaningsoftensescan possiblyhelpL2 learnersassociatetheword

labelsand morphemes whichrefertotimedivisions.

The data furthershowthatfortheseL2 learners, thepresentpro-

gressive,past simple,and past progressive, respectively,repre-

sentedthemostaccessibledeictictimespans.It is reasonablethat

theteachingof Englishtensesshouldbeginwiththesethreetenses.

Ashasbeennoted,Japanesespeakersmayhaveparticular difficulty

withthemeanings and morphology associatedwiththepastsimple.

Because NNSs tendto relyon lexicaltimemarkerssuchas before

and afterwheninterpreting themeaningsof tensesand theirmor-

phological references, these may be included in the initial

explanationsof the Englishtense systemto facilitatethelearners

of

understanding time-span and tensemeanings.

relationships

Because morphologicaltense markersimpose constraints on

learnerperformance, be

theymay specially addressed in conjunc-

tionwithtensemeanings. The speakersofSpanishseemtohavedif-

ficultydistinguishingbetween Englishtense-related morphemes

568 TESOL QUARTERLY

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.158 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 12:26:38 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

and false cognates associated withthe Spanish tense systemand its

morphology (Andersen, 1983; Comrie, 1985). The intuitionsof

Vietnamese speakers regardingtense morphologicalmarkersseem

to be notably differentfromthose of other groups of NNSs, pre-

sumablydue to theabsence of morphologicaldeixisin theirL1. For

speakers of Arabic,as opposed to Chinese and Korean,Englishno-

tionsof temporalityseem to impose somewhatreduced constraints

associated with notionsof temporality.However, theiracquisition

of the meaningsand formsfor the perfecttenses,such as the past

perfect,past perfectprogressive,and presentperfect,appears to

presentsubstantialdifficulty. In verygeneralterms,the teachingof

English conceptual notionsof time,its divisions,and the relation-

ships between these divisions can underlie or even precede the

teachingof the tensesystemand itsmorphologicalreferences.

THE AUTHOR

Eli HinkelreceivedherPhD inlinguistics

fromThe UniversityofMichiganin1984

and has taughtin intensive

and ITA-training

programsforthepast10 years.Her

researchinterests

includeconcept-based and L2 teachingmethodologies.

transfer

She is employedas Coordinator of theESL CompositionProgramat The Ohio

StateUniversity.

REFERENCES

Andersen, R. (1977).The impoverished stateofcross-sectionalmorpheme

acquisition/accuracymorphology. In C. Henning(Ed.), Proceedingsof

theLos AngelesSecondLanguageResearchForum(pp.308-320).Los

Angeles:University ofCalifornia.

Andersen, R. (1983). Transferto somewhere.In S. Gass & L. Selinker

(Eds.), Languagetransfer in languagelearning(pp. 177-202).Rowley,

MA: NewburyHouse.

Azar,B. (1989). Understanding and usingEnglishgrammar(2nd ed.).

EnglewoodCliffs,NJ:PrenticeHall.

Bach,K. (1981).Referential/attributive.Synthese, 49,219-244.

N., Madden,C., & Krashen,

Bailey, S. (1974).Is therea "natural

sequence"in

adultsecondlanguage learning?LanguageLearning, 27,235-244.

Bailey,N. (1989a). Theoreticalimplicationsof the acquisitionof the

English simple past and past progressive.In S. Gass, C. Madden,

D. Preston, & L. Selinker (Eds.), Variation in second language

acquisition:Vol. 2. Psycholinguistic issues (pp. 109-124).Clevedon,

England:Multilingual Matters.

L2 TENSE AND TIME REFERENCE 569

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.158 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 12:26:38 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Bailey,N. (1989b). Discourse conditionedtense variation:Teacher

implications.In M. Eisenstein(Ed.), The dynamicinterlanguage:

Empiricalstudiesinsecondlanguagevariation (pp. 279-295).New York:

PlenumPress.

Chappel,V., & Rodby,J. (1983). Verb tenseand ESL composition:A

discourse-level approach.In M. A.Clarke& J.Handscombe(Eds.), On

TESOL '82. Pacificperspectiveson languagelearningand teaching

(pp. 309-320).Washington, DC: TESOL.

Comrie,B. (1976).Aspect:An introduction to thestudyof verbalaspect

and relatedproblems.Cambridge:CambridgeUniversity Press.

Comrie,B. (1985).Tense.Cambridge:CambridgeUniversity Press.

Coppetiers, R. (1987).Competencedifferences betweennativeand non-

nativespeakers.Language,63,544-573.

DeCarrico,J. (1986). Tense, aspect and time in the Englishmodality.

TESOL Quarterly, 20(4),665-682.

Donnellan,K. (1991). Referenceand definitedescriptions. In S. Davis

(Ed.), Pragmatics (pp.52-64).Oxford:OxfordUniversity Press.

Dulay,H., & Burt,M. (1974).Naturalsequencesin childsecondlanguage

acquisition. LanguageLearning, 24,37-53.

Eisenstein, M. (1987). Grammaticalexplanationsin ESL: Teach the

student, notthemethod.In M. Long& J.Richards(Eds.), Methodology

in TESOL. New York:NewburyHouse.

Fillmore, C. (1975).Santa Cruz lectureson deixis.Bloomington: Indiana

University Linguistics Club.

Guiora,A. (1983).The dialecticoflanguageacquisition. LanguageLearn-

ing,33,3-12.

Hatch,E. (1978).Discourseanalysisand secondlanguageacquisition.In

E. Hatch (Ed.), Second language acquisition:A book of readings.

Rowley,MA: NewburyHouse.

Inoue,K. (1984). Some discourseprinciplesand lengthysentencesin

Japanese.In S. Miyagawa& C. Kitagawa(Eds.), Studiesin Japanese

languageuse. Edmonton, Canada: Linguistic Research.

JooHwang,S. J.(1987).DiscoursefeatureofKoreannarration. Dallas,TX:

The SummerInstitute ofLinguistics.

Kaye,A. (1987).Arabic.In B. Comrie(Ed.), The world'smajorlanguages.

Oxford:OxfordUniversity Press.

Kripke, S. (1991).Speaker'sreference and semanticreference. In S. Davis

(Ed.), Pragmatics (pp.77-96).Oxford:OxfordUniversity Press.

Larsen-Freeman, D. (1976).An explanation of themorphemeacquisition

orderofsecondlanguagelearners. LanguageLearning, 26,125-134.

Leech,G. (1971).Meaningand theEnglishverb.London:Longman.

Leech,G., & Svartvik, J. (1975). A communicative grammarof English.

London:Longman.

Levinson, S. (1983).Pragmatics. Cambridge:CambridgeUniversity Press.

Li,C., & Thompson, S. (1981).MandarinChinese.A functional reference

grammar. Berkeley: University ofCaliforniaPress.

Lyons,J. (1977). Semantics(Vols. 1 & 2). Cambridge: Cambridge

UniversityPress.

570 TESOL QUARTERLY

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.158 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 12:26:38 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Makino,T. (1979). English morphemeacquisitionorder of Japanese

secondaryschoolstudents. TESOL Quarterly, 13(3),428-449.

Nguyen, D-H. (1987).Vietnamese. In B. Comrie(Ed.), The world'smajor

languages.Oxford:OxfordUniversity Press.

Olshtain,E. (1979). The acquisitionof the Englishprogressive: A case

study of a seven-year-oldHebrew speaker. WorkingPapers in

Bilingualism, 18,81-102.

Pienemann,M. (1985). Learnabilityand syllabus construction.In

K. Hyltenstam & M.Pienemann(Eds.), Modelingand assessingsecond

languageacquisition. San Diego, CA: College-HillPress.

Recanati,F. (1991). The pragmaticsof what is said. In S. Davis (Ed.),

Pragmatics (pp.97-120).Oxford:OxfordUniversity Press.

Richards,J.C. (1973). Erroranalysisand second languagestrategies. In

J.W.Oller & J.C. Richards(Eds.), Focus on the learner:Pragmatic

perspectives forthelanguageteacher.Rowley,MA: NewburyHouse.

Richards, C.

J. (1981). Introducing the progressive.TESOL Quarterly,

15(4),391-402.

Richards,J.C. (1987).Introducing theperfect:An exercisein pedagogic

grammar.In M. H. Long & J.C. Richards(Eds.), Methodologyin

TESOL. New York:NewburyHouse.

Riddle,E. (1986). Meaningand discoursefunctionof the past tensein

English.TESOL Quarterly, 20(2),267-286.

Searle,J.(1979).Referentialand attributive.Monist,62,190-208.

SharwoodSmith, M. (1988).Imperative versusprogressive:Anexercisein

contrastive pedagogicallinguistics.In W.Rutherford & M. Sharwood

Smith(Eds.), Grammarand second languageteaching.New York:

NewburyHouse.

von Stutterheim, C., & Klein,W. (1987).A concept-oriented approachto

secondlanguagestudies.In C. Pfaff(Ed.), Firstand secondlanguage

acquisitionprocess.Cambridge,MA: NewburyHouse.

L2 TENSE AND TIME REFERENCE 571

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.158 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 12:26:38 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

APPENDIX

SENTENCESUSED IN THE QUESTIONNAIRE

Usedfordataanalysis Excludedfromdataanalysis

1. Bob is talking

tohisbrother. 1. Bob is visiting

hiscousin.

2. Johnwalkstoschool. 2. JohntalkstoPeter.

3. The studenttalkedto his friendabout 3. The studentwalkedto schoolfromthe

thenewmovie. meeting.

4. The studentshad been talkingto Bob 4. Peterhad been walkingquicklybefore

beforethemeeting. meeting Bob.

5. Peterwas walkingquietly. 5. Johnwas talking quietly.

6. Peterhaswalkedtoschool. 6. Bob hastalkedto Peter.

7. Johntalks to his brotherabout his 7. The student at school.

visitshisbrother

friends.

8. Bob is walkingto themovies. 8. Johnis talkingtoa friend.

9. Johnhas been talkingto Bob on the 9. Peterhas been visitinghis brotherin

phone. Hawaii.

10. Johnhad been visitingBob before 10. The studenthad been walkinghome

leavingforschool. beforetherain.

11. Johnhasvisitedhisbrother at school. 11. Bob hastalkedabouthisnewschool.

12. Bob hasbeenwalking. 12. Johnwalkedto themeeting.

inHawaii.

13. Petervisitedhisbrother 13. Peterhasbeentalking on thephone.

14. The studenthad visitedBob before 14. The studenthad talkedto Bob before

goingto school. goinghome.

15. Johnhad talkedtoPeterbeforelunch. 15. Bob had walked to school before

talkingto Peter.

to Bob.

16. Johnwas talking 16. Peterwas Bob.

visiting

572 TESOL QUARTERLY

This content downloaded from 91.229.229.158 on Sat, 21 Jun 2014 12:26:38 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Indian EnglishDocument10 pagesIndian Englishlung_fengNo ratings yet

- Lexical Priming Explicit Instruction Scheffler ELTJ2015Document4 pagesLexical Priming Explicit Instruction Scheffler ELTJ2015Allai JoesenNo ratings yet

- Unit 6: Past TensesDocument11 pagesUnit 6: Past TensesTommy DelkNo ratings yet

- Hinkel L2TenseTime 199265 6 2024Document17 pagesHinkel L2TenseTime 199265 6 2024JohnRakotoHacheimNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Collocation Instruction On The Reading Comprehension andDocument29 pagesThe Effects of Collocation Instruction On The Reading Comprehension andUMUT MUHARREM SALİHOĞLUNo ratings yet

- Experimental and Intervention Studies On Formulaic Sequences in A Second LanguageDocument29 pagesExperimental and Intervention Studies On Formulaic Sequences in A Second LanguageMelissa FeNo ratings yet

- Vocabulary-Learning Strategies of Foreign-Language StudentsDocument35 pagesVocabulary-Learning Strategies of Foreign-Language StudentsPiyakarn SangkapanNo ratings yet

- Grammar Learning and Teaching Time, Tense and VerbDocument9 pagesGrammar Learning and Teaching Time, Tense and VerbHend AhmedNo ratings yet

- 07 Spelling and MorphologyDocument4 pages07 Spelling and MorphologySofhie LemarNo ratings yet

- Pointing Out Phrasal VerbsDocument22 pagesPointing Out Phrasal VerbsElaine Nunes100% (1)

- Article - Second Language Acquisition Research - A Resource For Changing Teachers' Professional CulturesDocument15 pagesArticle - Second Language Acquisition Research - A Resource For Changing Teachers' Professional CulturesDespina KalaitzidouNo ratings yet

- Teachers of English To Speakers of Other Languages, Inc. (TESOL)Document26 pagesTeachers of English To Speakers of Other Languages, Inc. (TESOL)Trần ĐãNo ratings yet

- Prince 1996Document17 pagesPrince 1996Adriana InomataNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Linguistic Approaches To Teaching Vocabulary Assessment and Integration - Boers F. (2013)Document17 pagesCognitive Linguistic Approaches To Teaching Vocabulary Assessment and Integration - Boers F. (2013)Zaro YamatoNo ratings yet

- Rod Ellis - Current Issues in Teaching Grammar and SLA Perspective PDFDocument26 pagesRod Ellis - Current Issues in Teaching Grammar and SLA Perspective PDFYumi MeeksGiz Sawabe100% (4)

- Williams and Locatt 2003 - Phonolo G Ical Memory and Rule LearningDocument55 pagesWilliams and Locatt 2003 - Phonolo G Ical Memory and Rule LearningLaura CannellaNo ratings yet

- Teaching Grammar in Writing ClassesDocument18 pagesTeaching Grammar in Writing ClassesVasile VaganovNo ratings yet

- The Vocabulary-Learning Strategies PDFDocument35 pagesThe Vocabulary-Learning Strategies PDFJulio201010No ratings yet

- Johnson 1981,1982Document19 pagesJohnson 1981,1982Kharisma KaruniaNo ratings yet

- 2010 - Tyle & Ho - Applying Cognitive Linguistics To Instructed L2 Learning The English ModalsDocument20 pages2010 - Tyle & Ho - Applying Cognitive Linguistics To Instructed L2 Learning The English ModalsNguyen HoangNo ratings yet

- Tense and Aspect in Second Language AcquDocument22 pagesTense and Aspect in Second Language AcquKim ThaoNo ratings yet

- Boers WebbDocument27 pagesBoers WebbDrGeePeeNo ratings yet

- Keyword Method Application ArticleDocument18 pagesKeyword Method Application ArticleMerve TohmaNo ratings yet

- Local Media4840794288878912363Document15 pagesLocal Media4840794288878912363lerorogodNo ratings yet

- TESOL MA Essay Use of Mnemonics in Learning NovelDocument9 pagesTESOL MA Essay Use of Mnemonics in Learning NovelNur Adlina Shatirah Ahmad ZainudinNo ratings yet

- Teacher Language Awareness: A Discursive EssayDocument19 pagesTeacher Language Awareness: A Discursive EssayEstherRachelThomas100% (1)

- Rod Ellis - The Structural Syllabus and Language Acquisition PDFDocument24 pagesRod Ellis - The Structural Syllabus and Language Acquisition PDFYumi MeeksGiz Sawabe50% (2)

- Mnemonic Effectiveness of CL Motivated P PDFDocument12 pagesMnemonic Effectiveness of CL Motivated P PDFElaine NunesNo ratings yet

- CAPAROSODocument7 pagesCAPAROSOSofia NicoleNo ratings yet

- Statistical Learning of SyntaxDocument43 pagesStatistical Learning of SyntaxktyasirNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 61.92.158.55 On Sun, 28 Apr 2024 09:09:00 +00:00Document9 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 61.92.158.55 On Sun, 28 Apr 2024 09:09:00 +00:00voxa0827No ratings yet

- Teaching VocabularyDocument8 pagesTeaching VocabularyDesu AdnyaNo ratings yet

- Auerbach - Burguess 1985 - The Hidden CurriculumDocument22 pagesAuerbach - Burguess 1985 - The Hidden CurriculumFanni LeczkésiNo ratings yet

- Scandinavian J Psychology - 2023 - Dujardin - Vocabulary and Reading Comprehension What Are The Links in 7 To 10 Year OldDocument13 pagesScandinavian J Psychology - 2023 - Dujardin - Vocabulary and Reading Comprehension What Are The Links in 7 To 10 Year OldDiego LourençoNo ratings yet

- Issues in Applied Linguistics: TitleDocument8 pagesIssues in Applied Linguistics: TitleBunda Haidar AliNo ratings yet

- Written Report On Sentence ProcessingDocument5 pagesWritten Report On Sentence ProcessingAlfeo OriginalNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0749596X04000579 MainDocument18 pages1 s2.0 S0749596X04000579 MainTran Ngo TuNo ratings yet

- The Most Frequently Used Spoken American English IdiomsDocument31 pagesThe Most Frequently Used Spoken American English Idioms7YfvnJSWu100% (1)

- Bennett, P. (2017) - Using Cognitive Linguistic Principles To Encourage Production of Metaphorical Vocabulary in WritingDocument9 pagesBennett, P. (2017) - Using Cognitive Linguistic Principles To Encourage Production of Metaphorical Vocabulary in Writingddoblex doblexNo ratings yet

- A Cognitive Grammar Perpective On Tense and AspectDocument41 pagesA Cognitive Grammar Perpective On Tense and AspectnedrubNo ratings yet

- Carol Fraser 1999Document17 pagesCarol Fraser 1999Pedro Pernías PérezNo ratings yet

- Toward A Meaningful Definition of Vocabulary Size: Journal of Reading Behavior 1991, Volume XXIII, No. 1Document14 pagesToward A Meaningful Definition of Vocabulary Size: Journal of Reading Behavior 1991, Volume XXIII, No. 1ivanilldatvr.09gmail.comNo ratings yet

- A Review of Research Into Vocabulary Learning and AcquisitionDocument9 pagesA Review of Research Into Vocabulary Learning and Acquisitionman_dainese100% (1)

- Boers (2013) Cognitive Linguistic Approaches To Teaching Vocabulary Assessment and IntegrationDocument18 pagesBoers (2013) Cognitive Linguistic Approaches To Teaching Vocabulary Assessment and IntegrationEdward FungNo ratings yet

- Conceptual Metaphor Within Invariant Meaning The Learning of Phrasal Verbs Among Malaysian Esl LearnersDocument23 pagesConceptual Metaphor Within Invariant Meaning The Learning of Phrasal Verbs Among Malaysian Esl LearnersGlobal Research and Development ServicesNo ratings yet

- The Frequency and Use of Lexical Bundles in Conversation and AcadDocument17 pagesThe Frequency and Use of Lexical Bundles in Conversation and Acad谷光生No ratings yet

- An Inductive Approach To Young Learner Grammar: David E. Shaffer (Chosun University) Disin@chosun - Ac.krDocument8 pagesAn Inductive Approach To Young Learner Grammar: David E. Shaffer (Chosun University) Disin@chosun - Ac.krdindaNo ratings yet

- 2015 Hatami Journal Teaching Formulaic SequencesDocument18 pages2015 Hatami Journal Teaching Formulaic SequencesLautaro AvalosNo ratings yet

- Current Issues in The Teaching of GrammarDocument26 pagesCurrent Issues in The Teaching of GrammarEduardoNo ratings yet

- A Corpus-Based Analysis of Collocations in Tenth Grade High School English TextbooksDocument33 pagesA Corpus-Based Analysis of Collocations in Tenth Grade High School English TextbooksbotiralixNo ratings yet

- Phraseology and Second LanguageDocument21 pagesPhraseology and Second LanguageCennet EkiciNo ratings yet

- Comprehensible Input and Second Language AcquisitionDocument21 pagesComprehensible Input and Second Language AcquisitionJuan Andrés Molina CastroNo ratings yet

- Fotos and Ellis - Communicating ABout Grammar A Task Based Approach PDFDocument25 pagesFotos and Ellis - Communicating ABout Grammar A Task Based Approach PDFYumi MeeksGiz Sawabe0% (1)

- 4) Chapter IiDocument28 pages4) Chapter IiOktaNo ratings yet

- JSSP 2015 179 193 PDFDocument16 pagesJSSP 2015 179 193 PDFChiosa AdinaNo ratings yet

- Artikel 2Document20 pagesArtikel 2Alina ЧернышоваNo ratings yet

- Alvin Cheng-Hsien ChenDocument33 pagesAlvin Cheng-Hsien ChenJaminea KarizNo ratings yet

- Verb-Noun Collocations in Second Language Writing: A Corpus Analysis of Learners' EnglishDocument26 pagesVerb-Noun Collocations in Second Language Writing: A Corpus Analysis of Learners' EnglishenviNo ratings yet

- Teachers of English To Speakers of Other Languages, Inc. (TESOL)Document9 pagesTeachers of English To Speakers of Other Languages, Inc. (TESOL)Juan Carlos LugoNo ratings yet

- Lesson Essential QuestionsDocument5 pagesLesson Essential Questionsapi-243783580No ratings yet

- Fast Track 100 Grammar PointsDocument54 pagesFast Track 100 Grammar Pointsbianet13No ratings yet

- TESOL Study Guide 2010Document31 pagesTESOL Study Guide 2010Amera SherifNo ratings yet

- Semantic and Lingua-Cultural Features of English and Uzbek Medical PeriphrasesDocument6 pagesSemantic and Lingua-Cultural Features of English and Uzbek Medical PeriphrasesResearch ParkNo ratings yet

- First and Second ConditionalDocument3 pagesFirst and Second ConditionalNataliia VerkhulevskayaNo ratings yet

- Quantitative Study of Speech PDFDocument59 pagesQuantitative Study of Speech PDFFariha PromyNo ratings yet

- Curr304 LessonsDocument9 pagesCurr304 Lessonsapi-308387789No ratings yet

- 工程英语对话 1Document3 pages工程英语对话 1Li YongNo ratings yet

- Social N Regional NotesDocument5 pagesSocial N Regional NotesAhmad KamilNo ratings yet

- What Does Teaching Pronunciation Involve?: Sounds of The LanguageDocument4 pagesWhat Does Teaching Pronunciation Involve?: Sounds of The LanguageesthefaniNo ratings yet

- GEO261 Answers 4Document4 pagesGEO261 Answers 4Sakib MahmudNo ratings yet

- соч 6 в 2 четвертьDocument13 pagesсоч 6 в 2 четвертьSagyngan Abdketegi ZhetpiskyzyNo ratings yet

- Lexical Bundles in Mainstream FilmsDocument30 pagesLexical Bundles in Mainstream Filmshamidmostafa833No ratings yet

- Facilitating Integrative Performance Task - Longos National High SchoolDocument67 pagesFacilitating Integrative Performance Task - Longos National High SchoolAngelo EspirituNo ratings yet

- English Grade 4Document5 pagesEnglish Grade 4Aiman Bhatti Rasool BhattiNo ratings yet

- Word FormationDocument5 pagesWord FormationAddi MuhammadNo ratings yet

- 10th English Guide - Unit 1 and 2 by Penguin PublicationDocument165 pages10th English Guide - Unit 1 and 2 by Penguin Publicationsaoud khanNo ratings yet

- Module 5 6 Week 5 6Document17 pagesModule 5 6 Week 5 6Jirah Joy PeañarNo ratings yet

- Fina DemoDocument3 pagesFina DemoShirley TinaweNo ratings yet

- 1stmarch Updated Version - February, New Topics, Presentation Online Course 2021Document27 pages1stmarch Updated Version - February, New Topics, Presentation Online Course 2021Радомир МутабџијаNo ratings yet

- EFN D - Summary of Focus Group 1-7Document49 pagesEFN D - Summary of Focus Group 1-7Fifi FirdianaNo ratings yet

- Programación Ingles FinalDocument47 pagesProgramación Ingles FinalJose Luis Juan DominguezNo ratings yet

- What Is Phonetics?Document27 pagesWhat Is Phonetics?faisal sayyarNo ratings yet

- Portuguese Phrase BookDocument132 pagesPortuguese Phrase BookVinicius Passos100% (13)

- English For Mechanical Engineering Student's Book 3: 1. Overall ObjectivesDocument13 pagesEnglish For Mechanical Engineering Student's Book 3: 1. Overall ObjectivesQuang Pham NgocNo ratings yet

- Eapp Q1 Week 1 and 2Document13 pagesEapp Q1 Week 1 and 2Donna Mendoza Comia0% (2)

- A Brief History of EnglishDocument3 pagesA Brief History of EnglishAlfauje MoradNo ratings yet