Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Dependence of Mathematical Knowledge On Culture: Rajesh Swaminathan

Dependence of Mathematical Knowledge On Culture: Rajesh Swaminathan

Uploaded by

Uncharted FireOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Dependence of Mathematical Knowledge On Culture: Rajesh Swaminathan

Dependence of Mathematical Knowledge On Culture: Rajesh Swaminathan

Uploaded by

Uncharted FireCopyright:

Available Formats

Dependence of Mathematical Knowledge on Culture

Rajesh Swaminathan

Candidate Code : D 001188 - 034

February 16, 2005

10. Is knowledge in mathematics and other Areas of Knowledge dependent on culture to the same

degree and in the same ways?

Knowledge in mathematics and other areas of knowledge is dependent on culture in the same

ways, but not to the same degree, with a few noteworthy exceptions. Mathematics has proven to

be highly accurate from the time it began to be studied and put to use. However, knowledge from

mathematics can be derived only if the cultural setting encourages it, and only if this knowledge

and understanding promotes development of the culture. This makes mathematics more dependent

on culture when compared with other areas and fields of knowledge. Although knowledge in other

areas of knowledge is also dependent, to an extent, on culture in the same ways as mathematics,

the degree of dependence is found to be much lesser than that of mathematics. Cultural needs

bring about an interest and curiosity to develop mathematical knowledge, and although this is the

case with other fields, the extent to which these fields are dependent is not as large as it is in

mathematics.

In order to accurately answer the question at hand, we begin with the rather over-generalized

premise that for any area of knowledge to develop and progress, the presence of interest and cu-

riosity is unconditional. We then proceed to look at early mathematics, its development and the

factors that gave birth to its rise and maturation. Was culture a prominent factor? We run into

problems with this because there is no easy way to recognize culture as a factor, and even if we

do, it is difficult to gauge its importance. Time acts as an obstacle to our knowing because mathe-

matics has been practiced for time immemorial. Questions of validity and reliability spontaneously

arise when looking at anything in a historical perspective. However, it is possible to look at the

birth and rise of modern mathematics, analyze its factors and extrapolate these results to ancient

mathematical development.

In probing for a connection between knowledge and culture, we may ask ourselves a set of simple

and relevant questions whose answers have the potential of providing better insight into the prob-

lem: a) Can culture provoke interest and curiosity? b) Can culture hinder interest and curiosity?

c) Are there any noticeable similarities/differences in the relationship between culture and other

Swaminathan, Rajesh 1 Candidate Code : D 001188 - 034

areas of knowledge, and between culture and mathematics? The answers to all of these questions

are certainly, yes! What then is it about the nature of mathematical knowledge that makes it so

susceptible to cultural influence, especially in terms of content and acquisition? Will Durant notes

that “as soon as a field of inquiry yields knowledge, it is called science.”1 Mathematics is a branch

of science too. Thus without an “inquiry” or an active pursuit of knowledge—triggered by inquis-

itiveness and guided by curiosity—mathematics will have never attained the level of supremacy

it enjoys today. This may be a debatable conclusion, but it nevertheless helps demarcate, among

others, the influence on mathematics as caused by culture.

Counter-claims exist that it is not the cultural desire to enhance mathematical knowledge that

led to its development, but rather its usefulness and consistency. Necessity leads to invention,

no doubt, and this necessity can by all means be a cultural one. Early arithmetics enabled com-

merce; consequently, a culture actively engaged in trade and banking will have a more defined

set of mathematical principles. Cultural differences spur mathematical development in one envi-

ronment and hinder it in an other. If for instance the study of genetics and the science of cloning

can be shunned by certain cultures, why cannot a similar cultural clash inhibit or promote math-

ematical knowledge? Sadly, the above counter-claim fails to justify the existence of pockets of

“mathematically-intelligent” cultures as well as terminally “mathematical-illiterate” cultures.

A fine example would be that of the Egyptian culture. This rich and reputed culture had the practice

of burying the dead in tombs, which were in a giant triangular-like structure called a pyramid. The

building of pyramids, no doubt, called for an in-depth understanding of geometry and motivated

Egyptians mathematicians to discover the properties of pyramidal structures. On the other hand,

if the Egyptians, like most other cultures, simply buried the dead five-foot under the ground, they

would not have any urgent need to understand and develop their mathematical knowledge in this

fashion.

Now that we have established the exact relationship between mathematics and culture, we can

proceed to compare the degree of dependence on culture between mathematics and other areas

1

Durant, Will. The Pleasures of Philosophy. http://www.willdurant.com/pleasures.htm. Retrieved January 22,

2005.

Swaminathan, Rajesh 2 Candidate Code : D 001188 - 034

of knowledge. Admittedly, the dependence of knowledge in culture is less evident in the current

world, mostly because knowledge and information are shared so openly among the various cultures

in the world. In assessing this dependence, it may be wise to once again ask ourself a pertinent

question whose answer may shed some light on the problem at hand: Do the specific culture’s prac-

tices and beliefs have any effect in the amount of knowledge they gain from the different areas of

knowledge? The problem with ascertaining the correlation between culture and knowledge is that

some areas of knowledge are far more evenly spread out than the others. Dr. Brian Donohue-Lynch

comments that “cultural evolution (eg. from barbarism to civilization) [has prompted] humans

to devise countless ways to catalog human diversity. Most often these supposed patterns reflect

judgements in relation to one’s own cultures’ beliefs and practices.”2

An all important question to answer is: would development in any area of knowledge break down

if culture did? If it did, we can then conclude that there is an indubitable bond between knowledge

gathering and culture. If obtaining knowledge from any area of knowledge simply slowed down as

a result of culture break-down, then the degree of dependence is not as definite. In the realm of

mathematics, it is the culture’s historical background, its beliefs and practices that determine the

degree of reliance. For example, a more architecture-oriented culture is likely to have a much wider

set of mathematical principles than a culture which isn’t. This claim is exemplified by the fact that

when the Mogul emperor Shah Jahan decided to build the Taj Mahal, his architects and engineers

had to first study the mathematics behind domes, and also required to have an elaborate knowledge

on the various conic sections. We can attribute this finding to the Mogul culture, and the emperor’s

specific practice of honouring the dead. Indeed, these kind of examples are numerous in our

own history. The ancient Babylonians had a better understanding of contemporary mathematical

principles. Why? Because their cultural and geographical setting required them to tame rivers and

the devastating floods caused by them. This incited a need to engineer canals and dams which

could not have been possible without an in-depth understanding of mathematics. It is this cultural

necessity that motivates and spurs people to augment their mathematical knowledge. Does the

same thing happen with other areas of knowledge? Why, yes! Archaeology would be nowhere today

2

Donohue-Lynch, Brian. Types of Cultures. http://www.qvctc.commnet.edu/brian/typcult.html. Retrieved January

22, 2005.

Swaminathan, Rajesh 3 Candidate Code : D 001188 - 034

had cultures decided it was “unethical” or “injudicious” to unearth the dead. Astronomy was this

close to being dismissed as a crank due to the then prevailing culture’s anti-zealous preponderance.

But is it to the same degree that this reliance on cultural needs, beliefs and practices exists for areas

of knowledge excluding mathematics? I would argue not.

Drawing from personal experience, I have noticed that my interest and curiosity in mathematics

may be, loosely speaking, attributed to my ancestors’ cultural practice of working as accountants

under the rich land-owners. Bookkeeping was almost always the default profession, and accoun-

tants often had to perform several calculations in their heads instantly. This incited them to devise

clever mathematical “short-cuts”, observe patterns and use nature as a calculating tool. Further-

more, our culture’s religious practices require us to repeatedly chant mantras on a day-to-day basis

as part of a routine. This encourages us to memorize objects and lists by rote, whilst people foreign

to our culture might to do it in other ways. These are just a few of a plethora of instances where cul-

ture and cultural practices promote the development of a specific area of knowledge, while hinder

others and cause people to disregard the rest. There is thus an untold dependency between culture

and knowledge, and although this dependence occurs in the same manner, it is clearly evident, as

elicited by my argument, that it is not to the same degree. At the same time, it is important to

note that culture can have an influence only in various areas of knowledge but not in various ways

of knowing.

As is the case with every theory of knowledge argument, we also have exceptions to this claim that

‘cultural dependence occurs in the same ways, but not to the same degree.’ Art, for example, is one

of the oldest areas of knowledge that is still extant today. Drawing, painting, sculpting and other

forms of art are highly dependent on culture in the same ways as mathematics: they are both driven

by necessity, beliefs, practices, curiosity, inclination and affinity. But an important difference is that

art would not break down if culture did. This, I assert, is not the case with mathematics. If culture

broke down, there would be little or no motivation to further one’s mathematical knowledge. He

would be much like an unemployed carpenter who sees no immediate need to enhance his toolbox.

Knowledge in mathematics and other areas of knowledge are thus unarguably dependent on cul-

Swaminathan, Rajesh 4 Candidate Code : D 001188 - 034

ture for their improvement. Although knowledge in other areas of knowledge are dependent in the

same ways as is knowledge in mathematics, the extent and degree of this dependence is far greater.

Mathematics without culture would form as incomplete a picture as man without society.

Word Count: 1592

Swaminathan, Rajesh 5 Candidate Code : D 001188 - 034

You might also like

- Wisdom and Eloquence: A Christian Paradigm for Classical LearningFrom EverandWisdom and Eloquence: A Christian Paradigm for Classical LearningRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (10)

- Meaning and Relevance of HistoryDocument25 pagesMeaning and Relevance of Historyxmen 2014100% (3)

- Why Should We Hire YouDocument10 pagesWhy Should We Hire YouDixit Nagar0% (1)

- Phonics Lesson Plan-2Document3 pagesPhonics Lesson Plan-2api-300554601100% (2)

- TOK Essay Sem 3Document5 pagesTOK Essay Sem 3TJNo ratings yet

- AI Generated TOK EssayDocument6 pagesAI Generated TOK Essaychantal kitakaNo ratings yet

- Argumentative Essay - Why Study HistoryDocument1 pageArgumentative Essay - Why Study Historytanxir ahmedNo ratings yet

- Floridi 2013Document5 pagesFloridi 2013AndresNo ratings yet

- Mathematics Education and Its Cultural ContextDocument14 pagesMathematics Education and Its Cultural ContextSonia GalliNo ratings yet

- SERTSDocument13 pagesSERTSIan EncarnacionNo ratings yet

- GESTS01XDocument4 pagesGESTS01XChristian Kyle BeltranNo ratings yet

- Laura Mol Master Thesis SC Final-SmallDocument53 pagesLaura Mol Master Thesis SC Final-SmallAmanda Arruda100% (1)

- PHD Thesis in Cultural HeritageDocument6 pagesPHD Thesis in Cultural HeritageCustomPapersSingapore100% (2)

- Theory of Knowledge AOKsDocument15 pagesTheory of Knowledge AOKsRaynaahNo ratings yet

- Beltran-Written#1-Blue ScholarDocument4 pagesBeltran-Written#1-Blue ScholarChristian Kyle BeltranNo ratings yet

- The Program Ethnomathematics and The Challenges of GlobalizationDocument9 pagesThe Program Ethnomathematics and The Challenges of GlobalizationRizka AmaliaNo ratings yet

- Synthesis EssayDocument4 pagesSynthesis EssayЭльжан БалгаринаNo ratings yet

- D'ANDRADE, Roy. The Cultural Part of Cognition. Cognitive ScienceDocument17 pagesD'ANDRADE, Roy. The Cultural Part of Cognition. Cognitive ScienceCarolina ChabelaNo ratings yet

- Cogware AI RevisitedDocument9 pagesCogware AI RevisitedrkasturiNo ratings yet

- Etec 521 - Discussion PostsDocument11 pagesEtec 521 - Discussion Postsapi-555446766No ratings yet

- Name: Syeda Tooba Naqvi REG ID: 12895 SociologyDocument5 pagesName: Syeda Tooba Naqvi REG ID: 12895 SociologySyeda ToobaNo ratings yet

- Intro To IB TOKDocument7 pagesIntro To IB TOKptzpwpjk7gNo ratings yet

- Science Culture Language and Education in America 1St Ed Edition Emily Schoerning All ChapterDocument67 pagesScience Culture Language and Education in America 1St Ed Edition Emily Schoerning All Chapterelizabeth.kinne645100% (11)

- TOK ExhibitionDocument5 pagesTOK ExhibitionpapudjievNo ratings yet

- InglesDocument3 pagesInglesSantiago Enrique Pineda MeléndezNo ratings yet

- History News: Vol. 1 Why History Is Important 5 November 2013Document7 pagesHistory News: Vol. 1 Why History Is Important 5 November 2013brouhard123No ratings yet

- Considering The Current State of Our SocietyDocument2 pagesConsidering The Current State of Our SocietyLara May Basilad100% (1)

- Thesis Eleven RankingDocument8 pagesThesis Eleven Rankingkimtagtowsiouxfalls100% (2)

- Thesis Title DefenseDocument8 pagesThesis Title Defenselancedatol2No ratings yet

- Relevance of Learning History of MathematicsDocument14 pagesRelevance of Learning History of MathematicsAnjaliprakashNo ratings yet

- Fostering Love For Science and MathematicsDocument2 pagesFostering Love For Science and MathematicsLor RainaNo ratings yet

- Examples of A Argumentative EssayDocument7 pagesExamples of A Argumentative Essayezmt6r5c100% (2)

- Yumang Ge-102 M1 L1Document4 pagesYumang Ge-102 M1 L1GAM3 BOINo ratings yet

- 5 ConclusionsDocument12 pages5 ConclusionsCarolina PaezNo ratings yet

- How Did Society Shape Science and How Did Science Shape SocietyDocument2 pagesHow Did Society Shape Science and How Did Science Shape SocietyAngilene Lacson Cabinian100% (1)

- Culture EssayDocument7 pagesCulture Essayrlxaqgnbf100% (2)

- General Remarks On Ethnomathematics: ZDM 2001 Vol. 33 (3) AnalysesDocument3 pagesGeneral Remarks On Ethnomathematics: ZDM 2001 Vol. 33 (3) AnalysesMuzakkir SyamaunNo ratings yet

- The Use and Abuse of Science in Education: Life's Origins and Religious FaithDocument25 pagesThe Use and Abuse of Science in Education: Life's Origins and Religious FaithPhysicsDancerNo ratings yet

- KARNOOUH, Claude. Culture and Development (1984)Document12 pagesKARNOOUH, Claude. Culture and Development (1984)Marco Antonio GavérioNo ratings yet

- CultureDocument5 pagesCulturePhạm KhánhNo ratings yet

- DOT Essay (Michael Gwee) : Q2: Over Time Knowledge Has Become More Accurate'. DiscussDocument5 pagesDOT Essay (Michael Gwee) : Q2: Over Time Knowledge Has Become More Accurate'. DiscussMichael GweeNo ratings yet

- 1 Formac Researchers ManualDocument70 pages1 Formac Researchers ManualScribdTranslationsNo ratings yet

- Current Trends in Mathematics and Future Trends in Mathematics Education (Peter J Hilton)Document18 pagesCurrent Trends in Mathematics and Future Trends in Mathematics Education (Peter J Hilton)Mary Jane AnarnaNo ratings yet

- Ethnomathematics: Why, and What Else?: Abstract: Ethnomathematics - We All Have Some Notions ofDocument4 pagesEthnomathematics: Why, and What Else?: Abstract: Ethnomathematics - We All Have Some Notions ofPajar Reza PitriaNo ratings yet

- The Measurement of Civic Scientific LiteracyDocument22 pagesThe Measurement of Civic Scientific Literacyolyn.rcmNo ratings yet

- Activity 1Document2 pagesActivity 1Kate CabreraNo ratings yet

- Uas Basing Mei and ElisaDocument7 pagesUas Basing Mei and Elisa2107 Mei Shinta PrisciliaNo ratings yet

- Values of Teaching HistoryDocument6 pagesValues of Teaching HistoryKampo AkhangNo ratings yet

- Complete ListDocument109 pagesComplete ListИлья ЛыковNo ratings yet

- Human FlourishingDocument3 pagesHuman FlourishingYapoc SandaraNo ratings yet

- IntellectualDocument5 pagesIntellectualHeart EspineliNo ratings yet

- Sage: The C NC PT of Polítical D Ve LopmentDocument7 pagesSage: The C NC PT of Polítical D Ve LopmentJosé ChaoNo ratings yet

- STS Act 2Document3 pagesSTS Act 2Nica HannahNo ratings yet

- Essays On Climate Change and Global WarmingDocument7 pagesEssays On Climate Change and Global Warminghtzmxoaeg100% (2)

- Villanueva Reaction PaperDocument2 pagesVillanueva Reaction PaperJohnmark Villanueva50% (2)

- Muhammad Alam - TOK EssayDocument8 pagesMuhammad Alam - TOK EssayMuhammad AlamNo ratings yet

- FST01 Unit 1 To 10Document180 pagesFST01 Unit 1 To 10sumit prajapatiNo ratings yet

- Philosophy SampleDocument6 pagesPhilosophy SampleCharles Mwangi WaweruNo ratings yet

- Textbook How Does Government Listen To Scientists Claire Craig Ebook All Chapter PDFDocument53 pagesTextbook How Does Government Listen To Scientists Claire Craig Ebook All Chapter PDFrita.gonzalez174100% (13)

- PT 1Document3 pagesPT 1FOURNo ratings yet

- Opening Hours PHS and DUB30Document2 pagesOpening Hours PHS and DUB30Uncharted FireNo ratings yet

- CamScanner 11-18-2022 01.48Document1 pageCamScanner 11-18-2022 01.48Uncharted FireNo ratings yet

- 6325757Document2 pages6325757Uncharted FireNo ratings yet

- Section A: M21/5/MATHX/SP1/ENG/TZ2/XX/MDocument13 pagesSection A: M21/5/MATHX/SP1/ENG/TZ2/XX/MUncharted FireNo ratings yet

- IB Questionbank Physics 1Document3 pagesIB Questionbank Physics 1Uncharted FireNo ratings yet

- Chemistry: BACHELOR 2022-2023Document4 pagesChemistry: BACHELOR 2022-2023Uncharted FireNo ratings yet

- Enthalpy of Reaction Via Hess' Cycle: Standard Level: 5.1, 5.2, 5.3Document27 pagesEnthalpy of Reaction Via Hess' Cycle: Standard Level: 5.1, 5.2, 5.3Uncharted FireNo ratings yet

- Metallic Bonding & Giant Metallic Structures 2022Document31 pagesMetallic Bonding & Giant Metallic Structures 2022Uncharted FireNo ratings yet

- Prep Sheet Chem 2022 Mock Date: Thursday 24th MarchDocument6 pagesPrep Sheet Chem 2022 Mock Date: Thursday 24th MarchUncharted FireNo ratings yet

- Higher Level: 15.1 & 15.2: Student NameDocument64 pagesHigher Level: 15.1 & 15.2: Student NameUncharted FireNo ratings yet

- Welcome To: University College MaastrichtDocument46 pagesWelcome To: University College MaastrichtUncharted FireNo ratings yet

- Instructions For Motivation Video: There Is One Mandatory Question That You Should AddressDocument2 pagesInstructions For Motivation Video: There Is One Mandatory Question That You Should AddressUncharted FireNo ratings yet

- Aisb Ib DP Examinations 2022 Schedule: April 28 - May 20, 2022Document3 pagesAisb Ib DP Examinations 2022 Schedule: April 28 - May 20, 2022Uncharted FireNo ratings yet

- Grade 11 Chemistry IBDocument8 pagesGrade 11 Chemistry IBUncharted FireNo ratings yet

- The Area Under A Curve: Opening ProblemDocument8 pagesThe Area Under A Curve: Opening ProblemUncharted FireNo ratings yet

- Higher: GradeDocument6 pagesHigher: GradeUncharted FireNo ratings yet

- Internal Assessment Criteria IB Mathematics SL Analysis and ApproachesDocument4 pagesInternal Assessment Criteria IB Mathematics SL Analysis and ApproachesUncharted FireNo ratings yet

- Paper 2 Mock HL '21Document19 pagesPaper 2 Mock HL '21Uncharted FireNo ratings yet

- Unit 11 - Paper 1 and 2 HLDocument13 pagesUnit 11 - Paper 1 and 2 HLUncharted FireNo ratings yet

- Sweetsugar: +3 Bonus On SavesDocument6 pagesSweetsugar: +3 Bonus On SavesUncharted FireNo ratings yet

- Transition Metals: Name: - Class: - TeacherDocument20 pagesTransition Metals: Name: - Class: - TeacherUncharted FireNo ratings yet

- IB Questionbank Physics 1Document2 pagesIB Questionbank Physics 1Uncharted FireNo ratings yet

- (Total 1 Mark) : IB Questionbank Physics 1Document4 pages(Total 1 Mark) : IB Questionbank Physics 1Uncharted FireNo ratings yet

- IB Questionbank Physics 1Document5 pagesIB Questionbank Physics 1Uncharted FireNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2 - 12.1 Probability WaveDocument21 pagesLesson 2 - 12.1 Probability WaveUncharted FireNo ratings yet

- 12A ''Metallic Bonding & Giant Metallic Structures'Document31 pages12A ''Metallic Bonding & Giant Metallic Structures'Uncharted FireNo ratings yet

- Resistances - PoisonDocument6 pagesResistances - PoisonUncharted FireNo ratings yet

- Wizard 10 User-101439424: Saving Throw Modifiers TotalDocument4 pagesWizard 10 User-101439424: Saving Throw Modifiers TotalUncharted FireNo ratings yet

- Soyster Copy 2Document1 pageSoyster Copy 2Uncharted FireNo ratings yet

- Light Crossbow 2x Dagger +4 1d8+2 +4 1d4+2 Eldritch B +5 1d10+3Document1 pageLight Crossbow 2x Dagger +4 1d8+2 +4 1d4+2 Eldritch B +5 1d10+3Uncharted FireNo ratings yet

- 9990 Example Candidate Responses Paper 1 (For Examination From 2018)Document30 pages9990 Example Candidate Responses Paper 1 (For Examination From 2018)Mtendere Joseph ThomboziNo ratings yet

- Personality & Professional Development PlanDocument2 pagesPersonality & Professional Development PlanDavid CornejoNo ratings yet

- Love Leo BDocument29 pagesLove Leo BAnonymous R8JBpwNo ratings yet

- Practice Teaching Narrative Report 2018Document99 pagesPractice Teaching Narrative Report 2018Reymund GuillenNo ratings yet

- Module 1: Relationship of Psychology To Education in The Indian ContextDocument17 pagesModule 1: Relationship of Psychology To Education in The Indian ContextZeeNo ratings yet

- CV Resume Educ 290Document3 pagesCV Resume Educ 290api-608483341No ratings yet

- NMAC 2nd Round FormDocument2 pagesNMAC 2nd Round FormRabey The physicist100% (2)

- OB Sunday FINAL EXAM (Subjective Paper)Document2 pagesOB Sunday FINAL EXAM (Subjective Paper)NarinderNo ratings yet

- Health Educ QuizDocument3 pagesHealth Educ QuizLois DanielleNo ratings yet

- Information Bottleneck MethodDocument11 pagesInformation Bottleneck MethodAzamatNo ratings yet

- Triangle of Knowledge of Education: Teachers, Students and ParentsDocument12 pagesTriangle of Knowledge of Education: Teachers, Students and ParentsSaeed Ahmed ShaikhNo ratings yet

- Angelicum Academy of Heritage Marilao - Activity PDFDocument8 pagesAngelicum Academy of Heritage Marilao - Activity PDFArnel AcojedoNo ratings yet

- Digital School PDFDocument240 pagesDigital School PDFRahib KadilNo ratings yet

- Rubric EnglishDocument2 pagesRubric EnglishAgnes Gebone TaneoNo ratings yet

- Homeroom Narrative Report PTA MeetingsDocument9 pagesHomeroom Narrative Report PTA Meetingselenor may chantal l. messakaraeng100% (2)

- Made By: Nikita Yadav - PsychologistDocument26 pagesMade By: Nikita Yadav - PsychologistendahNo ratings yet

- Art of DelegationDocument19 pagesArt of DelegationDilip Dhage100% (1)

- Brochures LessonDocument9 pagesBrochures Lessonapi-236084849No ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines PolytechnicDocument5 pagesRepublic of The Philippines PolytechnicEduardo TalamanNo ratings yet

- Chanda's SecretsDocument34 pagesChanda's SecretsManal SalNo ratings yet

- Batting Tute NotesDocument3 pagesBatting Tute Notesapi-391215738No ratings yet

- Functions of Education Towards IndividualDocument2 pagesFunctions of Education Towards IndividualJonah ScottNo ratings yet

- مراجعة Math للصف الرابع الابتدائيDocument7 pagesمراجعة Math للصف الرابع الابتدائيEslam MansourNo ratings yet

- The Nature of Industrial BuyingDocument40 pagesThe Nature of Industrial Buying99862123780% (1)

- Cases and QuestionsDocument16 pagesCases and QuestionsLyleThereseNo ratings yet

- Turbo MachineDocument5 pagesTurbo MachineHarish KumarNo ratings yet

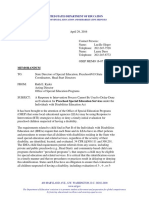

- Memorandum: United States Department of EducationDocument3 pagesMemorandum: United States Department of EducationKevinOhlandtNo ratings yet

- Anaesthesia Syllabus BfuhsDocument22 pagesAnaesthesia Syllabus BfuhsHarshit ChempallilNo ratings yet