Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Diabetes Empowerment Scale: A Measure of Psychosocial Self-Efficacy

The Diabetes Empowerment Scale: A Measure of Psychosocial Self-Efficacy

Uploaded by

Sokhifatun NajahOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Diabetes Empowerment Scale: A Measure of Psychosocial Self-Efficacy

The Diabetes Empowerment Scale: A Measure of Psychosocial Self-Efficacy

Uploaded by

Sokhifatun NajahCopyright:

Available Formats

Clinical Care/Education/Nutrition

O R I G I N A L A R T I C L E

The Diabetes Empowerment Scale

A measure of psychosocial self-efficacy

ROBERT M. ANDERSON, EDD JAMES T. FITZGERALD, PHD In 1991, we conducted a randomized

MARTHA M. FUNNELL, MS, RN, CDE DAVID G. MARRERO, PHD controlled trial to evaluate the effectiveness

of a patient empowerment program for

adults that focused entirely on psychosocial

issues such as managing stress, obtaining

family support, negotiating with health care

OBJECTIVE — The purpose of this study was to assess the validity, reliability, and utility of professionals and employers, and dealing

the Diabetes Empowerment Scale (DES), which is a measure of diabetes-related psychosocial

self-efficacy.

with uncomfortable emotions (23). Because

we were unable to identify a measure of dia-

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS — In this study (n = 375), the psychometric betes-related self-efficacy for adults that

properties of the DES were calculated. To establish validity, DES subscales were compared with focused on these important psychosocial

2 previously validated subscales of the Diabetes Care Profile (DCP). Factor and item analy- areas, we developed the Diabetes Empow-

ses were conducted to develop subscales that were coherent, meaningful, and had an accept- erment Scale (DES), which is a 37-item Lik-

able coefficient a. ert-type questionnaire (24), and we used it

in that study. The study showed that the

RESULTS — The psychometric analyses resulted in a 28-item DES (a = 0.96) with 3 sub- program resulted in both psychosocial and

scales: Managing the Psychosocial Aspects of Diabetes (a = 0.93), Assessing Dissatisfaction and blood glucose level improvements.

Readiness To Change (a = 0.81), and Setting and Achieving Diabetes Goals (a = 0.91). Con-

sistent correlations in the expected direction between DES subscales and DCP subscales pro-

vided evidence of concurrent validity. RESEARCH DESIGN AND

METHODS

CONCLUSIONS — This study provides preliminary evidence that the DES is a valid and

reliable measure of diabetes-related psychosocial self-efficacy. The DES should be a useful out- Instrument development

come measure for various educational and psychosocial interventions related to diabetes. The pilot version of the DES had 8 sub-

scales that were keyed to the major content

Diabetes Care 23:739–743, 2000 areas of the patient empowerment and edu-

cation program (23,24). The structure of

the DES and the patient empowerment

atients with diabetes must make a various behavioral challenges including pre- program were based on our earlier work in

P series of daily decisions involving

nutrition, physical activity, medica-

tion, blood glucose monitoring, and stress

management. Patients must also interact

ventive and disease management behaviors

(5–15). Studies in diabetes have demon-

strated the effect of perceived self-efficacy on

the adherence behavior of adolescents

patient empowerment (25–27). In an ear-

lier study (25), we defined the purpose of

the empowerment approach to diabetes

education as helping patients make

effectively with the health care system, their (16,17), African-American women with dia- informed choices about their diabetes self-

family members, friends, and employers betes (18), adults with complex insulin reg- management. In that study, we offered a

to obtain the support necessary to manage imens (18,19), and adults with type 1 or 4-step behavior change model: 1) patient

their diabetes (1). Thus, enhancing the per- type 2 diabetes (20–22). However, in these identification of problem areas, 2) explo-

ceived self-efficacy of patients to self-man- studies, self-efficacy has been defined pri- ration of the emotions associated with

age their diabetes is an important goal of marily as the perceived ability to engage in those problems, 3) development of a set of

diabetes care and education. various situation-specific self-management goals and strategies to overcome the barri-

Perceived self-efficacy has become an tasks such as blood glucose monitoring and ers to achieving those goals, and 4) deter-

important and useful construct in psychol- ordering meals in a restaurant, or the stud- mining patients’ motivation to make a

ogy (2–4) because it is related to the will- ies have focused on the needs of particular commitment to the behavior change plan.

ingness and the ability of people to engage in group of patients (e.g., adolescents). That approach to facilitating behavior

change in diabetic patients was adapted

from earlier work in counseling psychology

(28–31). Most of the patient empower-

From the Department of Medical Education (R.M.A., J.T.F.) and the Michigan Diabetes Research and Train-

ing Center (M.M.F.), University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, Michigan; and the Diabetes

ment program and DES subscales were

Research and Training Center (D.G.M.), Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, Indiana. derived from that behavior change model.

Address correspondence and reprint requests to Robert M. Anderson, EdD, Department of Medical Edu- The remaining 2 subscales (Managing Stress

cation, University of Michigan Medical School, G1116 Towsley Center 0201, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-0201. and Obtaining Psychosocial Support) were

E-mail: boba@umich.edu. added to the patient empowerment pro-

Received for publication 2 August 1999 and accepted in revised form 15 February 2000.

Abbreviations: DCP, Diabetes Care Profile; DES, Diabetes Empowerment Scale. gram and the DES because these areas have

A table elsewhere in this issue shows conventional and Système International (SI) units and conversion been identified as major barriers and/or

factors for many substances. facilitators (see the third step above) of

DIABETES CARE, VOLUME 23, NUMBER 6, JUNE 2000 739

The Diabetes Empowerment Scale

Table 1—Demographic information for survey self-reported positive adjustment to diabetes Statistical methods

respondents (n = 375) (23). A test–retest reliability score of 0.79 for A principal components factor analysis was

the DES was calculated by correlating the used to identify an empirically derived set

baseline scores of a no-treatment wait-listed of subscales. The factor structure was then

Age (years) 50.4 ± 15.8

control group with the group’s scores at the rotated using the Varimax method. Factor

Men/women 45/55

end of the control period 6 weeks later (23). loadings (the correlations of items with the

Type of diabetes

Because only 3 of the 8 subscales on factors) $0.50 were considered significant

Type 1 25

the pilot version of the DES had internal (because of the large sample size, factor

Type 2 using insulin 57

consistency scores (coefficient a) $0.80, loadings of smaller magnitude could be

Type 2 not using insulin 18

we reviewed the wording of the items to statistically significant) and were used to

Years since diabetes diagnosis 16.9 ± 10.8

determine whether we could improve the define factors. An iterative process of factor

Received diabetes patient 66

psychometric properties of the instrument. analyses and item analyses was used to

education

The items in the pilot version of the DES compare forced 6-, 5-, 4-, 3-, and 2-factor

Years of school completed

did not relate the self-efficacy items specif- solutions. This iterative process was used to

Eighth grade or less 2

ically to diabetes. We reasoned that making identify the smallest number of psycholog-

Some high school 5

each DES item specific to diabetes would ically coherent and meaningful factors,

High school graduate 21

be likely to make the DES a more valid and with the smallest number of items having a

Some college 73

reliable instrument. For example, in the coefficient a $0.80. A Pearson correlation

Ideal body weight (%)

pilot version of the DES, the item worded matrix was used to examine relationships

Men 117.2 ± 244

“In general, I believe that I can choose real- among the DES subscales. Pearson correla-

Women 136.8 ± 38.9

istic goals” was changed to read “I can tions were also used to examine the rela-

Data are means ± SD or %. choose realistic diabetes goals.” tionships between each DES subscale and

For the study reported herein, the DES the DCP Positive Attitude, Negative Atti-

was mailed or given to a convenience sam- tude, and Diabetes Understanding scales

behavior change and psychosocial adapta- ple of patients with diabetes involved in and level of education.

tion to diabetes (32). various Michigan Diabetes Research and

In our earlier study (23), the pilot ver- Training Center outreach programs. The RESULTS — Table 1 presents demo-

sion of the DES was completed before the sampling strategy was chosen to ensure graphic information for the patients who

patient empowerment program, at the com- that the sample contained an adequate rep- completed the questionnaire. The original

pletion of the 6-week program, and at a 6- resentation of patients with diabetes in sample of patients who participated in the

week follow-up visit. Evidence for the terms of sex, age, and type of diabetes to earlier patient empowerment program

validity of the pilot version of the DES was carry out a sound psychometric analysis of study (23) had significantly more women

provided by consistent correlations among the completed DES questionnaires. We did and patients with type 1 diabetes than the

the pre- and postempowerment program not use multiple mailings or other similar sample in this study. Demographically, the

change scores on the DES and change scores strategies to maximize return rates because patients in this larger sample more closely

on independent measures of positive and our intention was not to generalize the resembled the randomly selected cohorts of

negative attitudes toward having diabetes as results of this study to a larger group of patients that we have studied in our com-

measured by the Diabetes Care Profile patients with diabetes. munity-based studies (38,39).

(DCP) (33) and by glycosylated hemoglobin

levels. The DCP Positive Attitude and Neg-

ative Attitude scales were chosen because Table 2—DES subscales

they have proven to be consistent and reli-

able measures of patients’ overall psychoso- Subscale Sample items

cial adjustment to diabetes (34–36). These

DCP subscales were also correlated with Managing the Psychosocial Aspects of Diabetes: “In general, I believe that I can ask for support

several the subscales of the Short Form-36, This subscale assesses the patients’ perceived for having and caring for my diabetes when I

which is a well-known quality-of-life mea- ability to obtain social support, manage stress, need it.”

sure (37). We reasoned that an overall mea- be self-motivating, and make diabetes-related “In general, I believe that I know what helps me

sure of psychosocial adjustment to diabetes decisions that are “right for me.” stay motivated to care for my diabetes.”

should correlate with measures of psy- Assessing Dissatisfaction and Readiness to “In general, I believe that I know what part(s) of

chosocial self-efficacy. A sample item from Change: This scale assesses patients’ perceived taking care of my diabetes that I am dissatisfied

the DCP Negative Attitude scale is “I am ability to identify aspects of caring for diabetes with.”

afraid of my diabetes.” A sample from the that they are dissatisfied with and their ability to “In general, I believe that I know what part(s) of

DCP Positive Attitude scale is “I can do just determine when they are ready to change their taking care of my diabetes that I am ready to

about anything I set out to do.” diabetes self-management plan. change.”

Finally, in the earlier study (23), baseline Setting and Achieving Diabetes Goals: This scale “In general, I believe that I can choose realistic

scores on the pilot version of the DES also assesses patients’ perceived ability to set realistic diabetes goals.”

correlated significantly in the expected direc- goals and reach them by overcoming the barri- “In general, I believe that I am able to decide

tion with patients’ self-reported comfort in ers to achieving their goals. which way of overcoming barriers to my

asking questions of their physician and their diabetes goals works best for me.”

740 DIABETES CARE, VOLUME 23, NUMBER 6, JUNE 2000

Anderson and Associates

Table 3—Descriptive statistics for DES subscales (n = 375) direction of the correlations between the

DES subscale scores and the Positive Atti-

tude, Negative Attitude, and Diabetes

Standardized Variance Eigen

Scale name n Means ± SD (range) item a ± SEM (%) value Understanding subscales of the DCP. Fur-

ther evidence for the validity and utility of

Managing the Psychosocial 9 3.91 ± 0.70 (1.44–5.00) 0.93 ± 0.04 45 16.6 the DES is provided by the positive corre-

Aspects of Diabetes lations between improved glycosylated

Assessing Dissatisfaction 9 3.96 ± 0.53 (1.78–5.00) 0.81 ± 0.03 6 2.1 hemoglobin change scores and improved

and Readiness to Change DES subscale change scores found in our

Setting and Achieving 10 3.96 ± 0.62 (1.80–5.00) 0.91 ± 0.03 5 1.9 earlier study (23).

Diabetes Goals Preliminary evidence for the test–retest

reliability of the DES is provided by the

test–retest correlation (0.79) between DES

scores when the pilot version instrument

Psychometric tests and scale to 0.59; the correlations between the 3 was administered to the same group of

statistics DES subscales and level of education subjects at the beginning and at the end of

A principal components factor analysis ranged from 0.10 to 0.17; and the corre- the 6-week no-treatment control period.

yielded 6 factors with eigen values $1.0. lations between the 3 DES subscales and The strength of the intercorrelations among

After examining the various factor solu- the self-reported Diabetes Understanding the DES subscales suggests that the instru-

tions, we judged the 3-factor solution to be scale ranged from 0.39 to 0.43. ment is measuring related but separate

the best. It yielded a 28-item DES (coeffi- The correlations with the Positive Atti- domains of psychosocial self-efficacy. Each

cient a = 0.96) with 3 subscales, which tude scale indicated that the patients coefficient a for the overall DES and the 3

accounts for 56% of the total variance. Fac- reporting greater levels of psychosocial self- subscales was good. The somewhat lower-

tor 1, entitled “Managing the Psychosocial efficacy had a more positive outlook about than-expected correlations between DES

Aspects of Diabetes” (a = 0.93), contains their life and diabetes. The correlations scores and level of education could be

items that describe patients’ perceived abil- with the Negative Attitude scale indicated because of lack of variability; 94% of the

ity to obtain needed social support, manage that the patients reporting greater levels of sample graduated from high school and/or

diabetes-related stress, be self-motivated, psychosocial self-efficacy have a less nega- had some college education. The relation-

and make diabetes care-related decisions. tive outlook on their life and diabetes. ship between these variables may be rela-

Factor 2, entitled “Assessing Dissatisfaction Finally, the DES had positive correlations tively weak. Further study will be required

and Readiness To Change” (a = 0.81), with the self-reported Diabetes Under- to determine the explanation.

assesses patients’ perceived ability to iden- standing scale and small positive correla-

tify areas of their diabetes self-management tions with level of education. Patients Specificity

plan that are unsatisfactory and to know reporting greater levels of psychosocial self- An important conceptual issue raised by

when they are prepared to make changes in efficacy also report having a better under- the DES study is the relationship of psy-

their self-management plans. Factor 3, enti- standing of diabetes. chosocial self-efficacy to diabetes-related

tled “Setting and Achieving Diabetes Goals” health behavior. Previous research related

(a = 0.91), assesses patients’ perceived self- CONCLUSIONS to self-efficacy suggests that, for self-efficacy

efficacy in identifying relevant and achiev- scores to have a strong predictive value

able diabetes goals and overcoming the Validity and reliability related to particular behaviors, the items

barriers to the achievement of those goals. The study described in this article provides must be very specific. However, specificity

See Table 2 for sample items. Descriptive preliminary support for the validity, relia- is not a dichotomous construct but rather is

statistics for the 3 DES subscales are pre- bility, and utility of the DES. The content a continuous one. For example, one could

sented in Table 3. The DES subscale corre- validity of the DES is supported by the fact ask about a patient’s perceived self-efficacy

lation matrix is presented in Table 4. The that it was derived from our previous the- related to exercise by creating items that

correlations among the subscales range oretically based work in patient empower- stated “I am very confident in my ability to:

from a low of 0.64 to a high of 0.75. ment. The concurrent validity of the DES is 1) exercise regularly to improve my blood

supported by the strength, consistency, and glucose control, 2) walk 4 times a week to

DES subscales and correlations with

validating measures

Moderate correlations were demonstrated Table 4—Pearson product-moment correlations between DES subscales (n = 375)

between the DES subscales and the 3 val-

idating subscales from the DCP (i.e., Pos- Managing the Psychosocial Assessing Dissatisfaction

itive Attitude, Negative Attitude, and Scale name Aspects of Diabetes and Readiness to Change

Diabetes Understanding) (Table 5). The

correlations between the 3 DES subscales Assessing Dissatisfaction 0.67 —

and the Positive Attitude scale ranged and Readiness to Change

from 0.32 to 0.59; the correlations Setting and Achieving 0.75 0.64

between the 3 DES subscales and the Diabetes Goals

Negative Attitude scale ranged from 0.38 All correlations are significant at P , 0.0001.

DIABETES CARE, VOLUME 23, NUMBER 6, JUNE 2000 741

The Diabetes Empowerment Scale

Table 5—Correlations among the DES subscales, the DCP subscales, and education level tion 90:767–772, 1995

10. Stephens RS, Wertz JS, Roffman RA: Self-

efficacy and marijuana cessation: a con-

DCP self-reported struct validity analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol

DCP Positive DCP Negative Education Diabetes Understanding 63:1022–1031, 1995

DES subcales Attitude scale* Attitude scale* level†§ scale*‡ 11. Boehm S, Coleman-Burns P, Schlenk EA,

Managing the Psychosocial 0.59 (363) 20.59 (362) 0.10 (357) 0.43 (364) Funnell MM, Parzuchowski J, Powell IJ:

Prostate cancer in African American men:

Aspects of Diabetes

increasing knowledge and self-efficacy.

Assessing Dissatisfaction 0.32 (367) 20.38 (366) 0.17 (360) 0.39 (368) J Commun Health Nurs 12:161–169, 1995

and Readiness to Change 12. Davis P, Busch AJ, Lowe JC, Taniguchi J,

Setting and Achieving 0.42 (368) 20.45 (367) 0.11 (361) 0.39 (369) Djkowich B: Evaluation of rheumatoid

Diabetes Goals arthritis patient education program: impact

Data are correlation coefficients (n). n varies slightly because not every respondent answered every item. *P . on knowledge and self-efficacy. Patient Educ

0.001; †education levels: 1, eighth grade or less, 2, some high school, 3, high school graduate, and 4, some col- Counsel 24:55–61, 1994

lege or technical school; ‡scores range from 1 (poor) to 7 (excellent); §P . 0.05. 13. Taal E, Rasker JJ, Seydel ER, Wiegman O:

Health status, adherence with health rec-

ommendations, self-efficacy and social sup-

port in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

improve my blood glucose control, 3) walk explore the validity, reliability, and utility of Patient Educ Counsel 20:63–76, 1993

2 miles 4 times a week to improve my this new measure. 14. Wigal JK, Stout C, Brandon M, Winder JA,

blood glucose control, and 4) walk 2 miles McConnaughy K, Creer TL, Kotses H: The

in 30 min 4 times a week to improve my knowledge, attitude, and self-efficacy

blood glucose control.” Acknowledgments — This study was sup- asthma questionnaire. Chest 104:1144–

Previous research related to self-effi- ported in part by National Institutes of Health 1148, 1993

Grant 5P60-DK-20572 and 5RO1-DK- 15. Lin CC, Ward SE: Perceived self-efficacy

cacy indicates that the more specifically 53994-02. and outcome expectancies in coping with

worded items are more predictive of spe- The DES and permission to use it can be chronic low back pain. Res Nurs Health 19:

cific behaviors. However, in our judgment, downloaded from www.med.umich.edu/mdrtc. 299–310, 1996

the DES should be considered a measure 16. Littlefield CH, Craven JL, Rodin GM, Dane-

of higher-order self-efficacy. Trying to be man D, Murray MA, Rydall AC: Relation-

overly specific in describing perceived abil- References ship of self-efficacy and binging to

ity related to items such as social support, 1. American Diabetes Association: Report of adherence to diabetes regimen among ado-

goal setting, and coping with emotions the Task Force on the Delivery of Diabetes lescents. Diabetes Care 15:90–94, 1992

does not make sense to us. We realize that Self-Management Education and Medical 17. Grossman HY, Brink S, Hauser ST: Self-effi-

the structure of the DES may limit its abil- Nutrition Therapy. Diabetes Spectrum 12: cacy in adolescent girls and boys with

ity to predict very specific behaviors. How- 44–47, 1999 insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Dia-

2. Bandura A: Self-efficacy. In Social Founda- betes Care 10:324–329, 1987

ever, in our judgment, the primary tions of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive 18. Skelly AH, Marshall JR, Haughey BP, Davis

purpose and value of the DES will be as a Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, Prentice-Hall, PJ, Dunford RG: Self-efficacy and confidence

measure of psychosocial self-efficacy 1986, p. 39–453 in outcomes as determinants of self-care

viewed as an outcome of successful clinical 3. Bandura A: Self-efficacy: toward a unifying practices in inner-city, African American

or educational interventions. We believe it theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev women with non-insulin-dependent dia-

may also be a useful measure of successful 842:191–215, 1977 betes. Diabetes Educ 21:38–46, 1995

adaptation to and self-management of dia- 4. Lawrence L, McLeroy KR: Self-efficacy and 19. Hurley AC, Shea CA: Self-efficacy: strategy

betes. Further study will be required to health education. J School Health 56: for enhancing diabetes self-care. Diabetes

determine whether these assertions will be 317–321, 1986 Educ 18:146–150, 1992

supported by data. 5. Dennis KE, Goldberg AP: Weight control 20. Rubin R, Peyrot M, Saudek CD: The effect

self-efficacy types and transitions affect of a diabetes education program incorpo-

In summary, these data provide pre- weight-loss/outcomes in obese women. rating coping skills training on emotional

liminary support that the DES has good Addict Behav 21:103–116, 1996 well-being and diabetes self-efficacy. Dia-

potential to add to our understanding of a 6. DuCharme KA, Brawley LR: Predicting the betes Educ 19:210–214, 1993

relatively understudied area of psychoso- intentions and behavior of exercise initiates 21. Kavanagh DJ, Gooley S, Wilson PH: Pre-

cial adjustment to diabetes, psychosocial using two forms of self-efficacy. J Behav Med diction of adherence and control in dia-

self-efficacy. This study provides prelimi- 18:479–497, 1995 betes. J Behav Med 16:509–522, 1993

nary support for the reliability and validity 7. Fontaine KR, Shaw DF: Effects of self-effi- 22. Johnson JA: Self-efficacy theory as a frame-

of the DES. Further research with different cacy and dispositional optimism on adher- work for community pharmacy-based dia-

samples of diabetic patients will be ence to step aerobic exercise classes. Percep betes education programs. Diabetes Educ

required to confirm the factor structure Motor Skills 81:251–255, 1995 22:237–241, 1996

8. Stuart K, Borland R, McMurray N: Self- 23. Anderson RM, Funnell MM, Butler P, Arnold

and subscale reliability of the DES. We do efficacy, health locus of control, and smok- MS, Fitzgerald JT, Feste C: Patient empow-

not believe that viewing the instrument as ing cessation. Addict Behav 19:1–12, 1994 erment: results of a randomized control trial.

“final” is either possible or desirable based 9. Gulliver SB, Hughes JR, Solomon LJ, Dey Diabetes Care 18:943–949, 1995

on our research to date. We look forward AN: An investigation of self-efficacy, partner 24. Anderson RM, Fitzgerald JT, Funnell MM,

to further research conducted by our own support and daily stresses as predictors of Feste C: Diabetes empowerment scales

group and other investigators to further relapse to smoking in self-quitters. Addic- (DES): a measure of psychosocial self-effi-

742 DIABETES CARE, VOLUME 23, NUMBER 6, JUNE 2000

Anderson and Associates

cacy (Abstract). Diabetes 46:269A, 1997 30. Combs A, Avila D, Purkey W: Helping Rela- 12:135–140, 1986

25. Anderson RM, Funnell MM, Barr PA, tionships. Boston, MA, Allyn & Bacon, 1978 36. Fitzgerald JT, Anderson RM, Funnell MM,

Dedrick RF, Davis WK: Learning to 31. Combs A: A Personal Approach to Teaching: Arnold MS, Davis WK, Aman LC, Jacober

empower patients: the results of a profes- Beliefs That Make a Difference. Boston, MA, SJ, Grunberger G: Differences in the impact

sional education program for diabetes edu- Allyn & Bacon, 1982 of dietary restrictions on African Ameri-

cators. Diabetes Care 14:584–590, 1991 32. Rubin RR, Peyrot MP: Psychosocial prob- cans and Caucasians with NIDDM. Diabetes

26. Funnell MM, Anderson RM, Arnold MS, lems and interventions in diabetes: a review Educ 23:41–47, 1997

Barr PA, Donnelly MB, Johnson PD, Taylor- of the literature. Diabetes Care 15:1640– 37. Anderson RM, Fitzgerald JT, Wisdom K,

Moon D, White N: Empowerment: an idea 1657, 1992 Davis WK, Hiss RG: A comparison of

whose time has come in diabetes educa- 33. Fitzgerald JT, Davis WK, Conell CC, Hess global versus disease-specific quality-of-life

tion. Diabetes Educ 17:37–41, 1991 GE, Hiss RG: Development and validation measures in patients with NIDDM. Dia-

27. Anderson RM: Patient empowerment and of the diabetes care profile (DCP). Eval betes Care 20:299–305, 1997

the traditional medical model: a case of Health Professions 19:208–230, 1996 38. Hiss RG, Anderson RM, Hess GE, Stepien

irreconcilable differences? Diabetes Care 18: 34. Davis WK, Hess GE, Harrison RV, Hiss RG: CJ, Davis WK: Community diabetes: a ten-

412–415, 1995 Psychosocial adjustment to and control of year perspective. Diabetes Care 17:1124–

28. Rogers C: Client-Centered Therapy. Boston, diabetes mellitus: differences by disease type 1134, 1994

MA, Houghton Mifflin, 1965 and treatment. Health Psychol 6:1–14, 1987 39. Anderson RM, Hess GE, Davis WK, Hiss

29. Rogers C: Freedom to Learn for the 809s. 35. Hess GE, Davis WK, Harrison RV: A dia- RG: Community diabetes care in the 1980s.

Columbus, OH, Merrill, 1983 betes psychosocial profile. Diabetes Educ Diabetes Care 11:519–526, 1988

DIABETES CARE, VOLUME 23, NUMBER 6, JUNE 2000 743

You might also like

- He Still Chose Me 2024Document4 pagesHe Still Chose Me 2024Susan Bauer Martire MagliocchiNo ratings yet

- Gottman Institute - Renew Your Love-Love Letter ExchangeDocument4 pagesGottman Institute - Renew Your Love-Love Letter ExchangeDiah RahmiNo ratings yet

- Catalog 2017Document88 pagesCatalog 2017Danilo Choir StuffNo ratings yet

- Mi Jesus Mi Amado, Sax EbDocument2 pagesMi Jesus Mi Amado, Sax EbLeo DNo ratings yet

- See, Nature Rejoicing: From The Ode To Queen MaryDocument10 pagesSee, Nature Rejoicing: From The Ode To Queen MaryMichael FabianNo ratings yet

- Uno para El Otro Tercer CieloDocument2 pagesUno para El Otro Tercer CieloeduardguitarproNo ratings yet

- Jay Z FT MR Hudson Forever YoungDocument2 pagesJay Z FT MR Hudson Forever YoungfernandoNo ratings yet

- Correré DrumsDocument2 pagesCorreré DrumsEdwin CujcuyNo ratings yet

- The Olive Tree PartituraDocument7 pagesThe Olive Tree PartituraTadeu MontenegroNo ratings yet

- Shine Barbie in The 12 Dancing PrincessesDocument3 pagesShine Barbie in The 12 Dancing PrincessesLucas PortelaNo ratings yet

- Otče Ťa Chválim: B Eb/B B F Eb/F B2 BDocument1 pageOtče Ťa Chválim: B Eb/B B F Eb/F B2 BdzadekNo ratings yet

- I Am A Child of GodDocument5 pagesI Am A Child of Godapi-19854402No ratings yet

- Cantemos Al Amor de Los AmoresDocument1 pageCantemos Al Amor de Los AmoresSaúl Hernández ÁlamoNo ratings yet

- Is There Room Sailiata Fano JR Is There Room Tenor 1Document3 pagesIs There Room Sailiata Fano JR Is There Room Tenor 1CRISTINA SOL ASARNo ratings yet

- A Standardized Program For Analyzing Temperament Its Development and Assessment in Gauging Individual Personality CharacteristicsDocument3 pagesA Standardized Program For Analyzing Temperament Its Development and Assessment in Gauging Individual Personality CharacteristicsJoshua StanNo ratings yet

- Is There Room Sailiata Fano JR Is There Roomtenor 2Document3 pagesIs There Room Sailiata Fano JR Is There Roomtenor 2CRISTINA SOL ASARNo ratings yet

- A Higher Call LyricsDocument7 pagesA Higher Call LyricsNota Belz100% (1)

- Amar Y Querer Eb PDFDocument3 pagesAmar Y Querer Eb PDFanon_808306552No ratings yet

- Las Mañanitas en SOLDocument1 pageLas Mañanitas en SOLEmma Jeannette RAmírezNo ratings yet

- Digno de AlabanzaDocument9 pagesDigno de AlabanzaDanilo Flores VillalobosNo ratings yet

- He Is My All Solo or Mezzo Baritone DuetDocument5 pagesHe Is My All Solo or Mezzo Baritone DuetIvan CabellonNo ratings yet

- When The Morning Comes: Q in The Sweet by and byDocument12 pagesWhen The Morning Comes: Q in The Sweet by and byMarcos Antonio MachadoNo ratings yet

- Canto Mi Vida TenDocument6 pagesCanto Mi Vida TenMiiry AkeNo ratings yet

- You Are The ChristDocument2 pagesYou Are The ChristEduardo Pastor100% (1)

- Aunque Ruja La Tormenta: PianoDocument2 pagesAunque Ruja La Tormenta: PianoSergio Fernandez100% (1)

- Oh How I Love Jesus: PianoDocument2 pagesOh How I Love Jesus: PianoNeanderNo ratings yet

- He Came For Me - TransposedDocument5 pagesHe Came For Me - TransposedDaniel LittellNo ratings yet

- 2009 12 0030 A Childs Prayer SpaDocument2 pages2009 12 0030 A Childs Prayer Spamoronick920100% (1)

- Porque Ele ViveDocument7 pagesPorque Ele ViveJonatasCostaNo ratings yet

- Sweet Hour of Prayer PDF Sheet MusicDocument5 pagesSweet Hour of Prayer PDF Sheet MusicLisandra SantinNo ratings yet

- Goodness of GodDocument7 pagesGoodness of GodDavidNo ratings yet

- Born To Wear A Crown SsatbDocument5 pagesBorn To Wear A Crown SsatbBabalola SundayNo ratings yet

- Santo, Santo, Santo (Variaciones) - Violin - IDocument1 pageSanto, Santo, Santo (Variaciones) - Violin - IMagetzy Mejia SoteloNo ratings yet

- Come Thou Fount (Above All Else) - Live (D)Document1 pageCome Thou Fount (Above All Else) - Live (D)Wim SupergansNo ratings yet

- Inyow: LDRL Cacdrgds GyefabDocument7 pagesInyow: LDRL Cacdrgds GyefabMark Albert Gatdula RaqueñoNo ratings yet

- 030201Document4 pages030201Nezer VergaraNo ratings yet

- 271 - Pdfsam - Guitarra Volumen 1 - Flor y Canto - JPR504 PDFDocument1 page271 - Pdfsam - Guitarra Volumen 1 - Flor y Canto - JPR504 PDFJuan Pablo GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Messiah - For Unto Us A Child Is Born PDFDocument10 pagesMessiah - For Unto Us A Child Is Born PDFMicaeli Rourke du PlessisNo ratings yet

- Bach BWV 538Document12 pagesBach BWV 538P-o FaalandNo ratings yet

- List of Recommended Songs For The Sundays of Lent Until Good FridayDocument28 pagesList of Recommended Songs For The Sundays of Lent Until Good FridayRussel Matthew PatolotNo ratings yet

- In The Upper Room: (TTBB and Cello)Document7 pagesIn The Upper Room: (TTBB and Cello)Pablo CastilloNo ratings yet

- 415 - Room at The Cross: Lead SheetDocument2 pages415 - Room at The Cross: Lead SheetSamuel ThibaultNo ratings yet

- To God Be The GloryDocument3 pagesTo God Be The GloryGarcia Emi0% (1)

- Love - Song-PianoDocument2 pagesLove - Song-PianorhodesjanNo ratings yet

- Amor de Mis Amores - Trumpet 1 - .PDF TRUM 1Document2 pagesAmor de Mis Amores - Trumpet 1 - .PDF TRUM 1Juanca Chugchilan100% (1)

- Dame Un Nuevo CorazónDocument3 pagesDame Un Nuevo CorazónPriscila TorresNo ratings yet

- This Is The DayDocument1 pageThis Is The DayruelbelloNo ratings yet

- Serenata Schubert. Dos Flautas y PianoDocument5 pagesSerenata Schubert. Dos Flautas y PianoconchiviolaNo ratings yet

- Hark! The Herald Angels Sing: Arr. Pentatonix 108Document15 pagesHark! The Herald Angels Sing: Arr. Pentatonix 108Anna ŚwięcickaNo ratings yet

- 向祢舉手 Lord I Stretch My Hands to You Jay AlthouseDocument5 pages向祢舉手 Lord I Stretch My Hands to You Jay Althouse蔡育霖No ratings yet

- Levanto Mis Manos EbDocument1 pageLevanto Mis Manos EbJAIRO EUCEDANo ratings yet

- Whole AgainDocument3 pagesWhole AgainLeon Odarniem Saniraf EtelpNo ratings yet

- The - Church's - One - Foundation - AURELIA Full Score-ChoralDocument7 pagesThe - Church's - One - Foundation - AURELIA Full Score-Choralpowell_scottNo ratings yet

- Cargador Bateria Chicago Electric 66783 PDFDocument12 pagesCargador Bateria Chicago Electric 66783 PDFRicardo JimenezNo ratings yet

- Born On Christmas Day (Coro de Niños) - Voz 3Document1 pageBorn On Christmas Day (Coro de Niños) - Voz 3SebastianIbarraNo ratings yet

- Modulo5. Behavior Change-2021Document20 pagesModulo5. Behavior Change-2021Armin Arceo DuranNo ratings yet

- Lifestyle Management S47: Evidence For The Bene FitsDocument50 pagesLifestyle Management S47: Evidence For The Bene FitsEvelyn CóndorNo ratings yet

- Diabetics Self Management PDFDocument56 pagesDiabetics Self Management PDFwsergio0072No ratings yet

- Foundations of Care: Education, Nutrition, Physical Activity, Smoking Cessation, Psychosocial Care, and ImmunizationDocument11 pagesFoundations of Care: Education, Nutrition, Physical Activity, Smoking Cessation, Psychosocial Care, and ImmunizationrakolovaNo ratings yet

- The Confidence in Diabetes Self-Care Scale (Adultos) (Alemania y USA)Document6 pagesThe Confidence in Diabetes Self-Care Scale (Adultos) (Alemania y USA)Verónica MelgarejoNo ratings yet

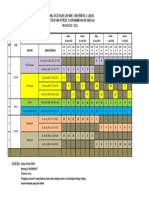

- Jadwal Ujian Proposal Skripsi - MaternitasDocument2 pagesJadwal Ujian Proposal Skripsi - MaternitasSokhifatun NajahNo ratings yet

- Defibrillation & Cardioversion: Ns. Retno Setyawati, M.Kep., SP - KMBDocument34 pagesDefibrillation & Cardioversion: Ns. Retno Setyawati, M.Kep., SP - KMBSokhifatun NajahNo ratings yet

- Jadwal Osce Online Lab KMB 3, Maternitas 2, Gadar Semester V Dan Vi Prodi S1 Keperawatan Fik Unissula TAHUN 2020 / 2021Document1 pageJadwal Osce Online Lab KMB 3, Maternitas 2, Gadar Semester V Dan Vi Prodi S1 Keperawatan Fik Unissula TAHUN 2020 / 2021Sokhifatun NajahNo ratings yet

- Biostatik Siti Ulfatun N C 30901800172Document3 pagesBiostatik Siti Ulfatun N C 30901800172Sokhifatun NajahNo ratings yet

- 07mjms25032018 Oa5Document11 pages07mjms25032018 Oa5Sokhifatun NajahNo ratings yet

- Calculation and Analyzing of Braces ConnectionsDocument71 pagesCalculation and Analyzing of Braces Connectionsjuliefe robles100% (1)

- Rai Community ProposalDocument11 pagesRai Community ProposalshekharNo ratings yet

- Student Handbook 2019-2020Document30 pagesStudent Handbook 2019-2020Gaetan HammondNo ratings yet

- BusEthSocResp Weeks 3-4Document6 pagesBusEthSocResp Weeks 3-4Christopher Nanz Lagura CustanNo ratings yet

- Coupling - Machine DesignDocument73 pagesCoupling - Machine DesignAk GamingNo ratings yet

- Afghan Girl: in Search of TheDocument2 pagesAfghan Girl: in Search of TheSon PhamNo ratings yet

- Photo Essay PDFDocument2 pagesPhoto Essay PDFMartha Glorie Manalo WallisNo ratings yet

- Simple Past Full ExercisesDocument6 pagesSimple Past Full Exercisespablo1130No ratings yet

- Becker Textilwerk: Preparation SheetDocument2 pagesBecker Textilwerk: Preparation Sheetabeer fatimaNo ratings yet

- Worksheet 8 Gread Number1Document3 pagesWorksheet 8 Gread Number1nknbjjqh5gNo ratings yet

- PETRONAS RETAILER Price List - W.E.F 10-10-23Document2 pagesPETRONAS RETAILER Price List - W.E.F 10-10-23Mujeeb SiddiqueNo ratings yet

- Office of The Punong Barangay Barangay Certification of AcceptanceDocument1 pageOffice of The Punong Barangay Barangay Certification of AcceptanceMah Jane DivinaNo ratings yet

- Notes On TennysonDocument2 pagesNotes On TennysonDonatella Di LelloNo ratings yet

- 1b Reading Output 2Document1 page1b Reading Output 2Elisha Maurelle AncogNo ratings yet

- CESPL - Profile1Document93 pagesCESPL - Profile1Satvinder Deep SinghNo ratings yet

- Forest Laws and Their Impact On Adivasi Economy in Colonial India1Document12 pagesForest Laws and Their Impact On Adivasi Economy in Colonial India1NidhiNo ratings yet

- Inorganic Chemistry 1 - Alkali Metals RevisioDocument7 pagesInorganic Chemistry 1 - Alkali Metals RevisioAshleyn Mary SandersNo ratings yet

- Chapter 14 NotesDocument21 pagesChapter 14 NotesnightdazeNo ratings yet

- Welcome To Good Shepherd Chapel: Thirty-Third Sunday in Ordinary TimeDocument4 pagesWelcome To Good Shepherd Chapel: Thirty-Third Sunday in Ordinary Timesaintmichaelpar7090No ratings yet

- Event Management NotesDocument24 pagesEvent Management Notesatoi firdausNo ratings yet

- Wild Amazon Cradle of Life Film TestDocument2 pagesWild Amazon Cradle of Life Film TestQuratulain MustafaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 13 Lecture 1 Career OptionsDocument24 pagesChapter 13 Lecture 1 Career OptionseltpgroupNo ratings yet

- Errata Sheet 1.7 - Dropzone Commander Official Update: NEW ADDITIONS/ CHANGES FROM VERSION 1.6 Highlighted in RedDocument2 pagesErrata Sheet 1.7 - Dropzone Commander Official Update: NEW ADDITIONS/ CHANGES FROM VERSION 1.6 Highlighted in RedTecnocastoroNo ratings yet

- The Power of Faith Confession & WorshipDocument38 pagesThe Power of Faith Confession & WorshipLarryDelaCruz100% (1)

- The Cannibalization of Jesus and The Persecution of The Jews.Document193 pagesThe Cannibalization of Jesus and The Persecution of The Jews.DrChris JamesNo ratings yet

- FAGL TcodesDocument3 pagesFAGL TcodesRahul100% (2)

- Factors Influencing Savings Mobilization by Commercial BanksDocument81 pagesFactors Influencing Savings Mobilization by Commercial BanksNicholas Gowon100% (7)

- Cape Sewing - Industrial Sewing TechnologyDocument33 pagesCape Sewing - Industrial Sewing TechnologyMonika GadgilNo ratings yet

- Neonatal Intubation: Past, Present, and Future: Practice GapsDocument9 pagesNeonatal Intubation: Past, Present, and Future: Practice GapskiloNo ratings yet

- CIRFormDocument3 pagesCIRFormVina Mae AtaldeNo ratings yet