Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Rice Prudence 1981 Evolution of Specialized Pottery Production A Trial Model-3

Rice Prudence 1981 Evolution of Specialized Pottery Production A Trial Model-3

Uploaded by

Dante .jpgOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Rice Prudence 1981 Evolution of Specialized Pottery Production A Trial Model-3

Rice Prudence 1981 Evolution of Specialized Pottery Production A Trial Model-3

Uploaded by

Dante .jpgCopyright:

Available Formats

CURRENT ANTHROPOLOGY Vol. 22, No.

3, June 1981

@ 1981 by The Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research 0011-3204/81/2203-0002$02.25

Evolution of Specialized Pottery Production:

A Trial Model1

by Prudence M. Rice

ARCHAEOLOGISTS have until quite recently given less attention 5. Why do certain kinds of specializations appear in certain

to production than to inter- and intraregional distribution (cf. parts of a region and not in others?

Morris 1974, Arnold 1975a, van der Leeuw 1976, Rice 1976a). 6. Why, when there are several communities involved in the

Although the methods of physicochemical analysis that are same craft product, may each have its own distinctive specialty?

used to identify sources of raw material can provide a basis for 7. How can the evolution of craft specialization be fitted into

a study of the manufacture of archaeological objects, they have general schemes of cultural evolution?

been used primarily to study trade. Provenience studies have 8. What are the implications of part-time versus full-time

been largely concerned with "macroprovenience," that is, specialization, and how can they be differentiated archaeo-

characterizations of local versus foreign or trade materials on logically?

a regional level. "Microprovenience" analyses, the kind that 9. Is control of production centralized or decentralized?

are necessary for study of production within a local area, are This paper is an effort to address some of these questions with

somewhat less common. reference to pottery production.

The study of specialist production involves a number of

interrelated theoretical and methodological questions, among

them the following: GENERAL THEORETICAL CONSIDERATIONS

1. What are the environmental and sociopolitical precondi-

tions of specialization? Economic specialization is a generally accepted concomitant of

2. What congruence can be established between archaeologi- social complexity. Cross-cultural studies of social complexity

cal definitions of specialization and ethnographic ones? How have suggested significant relationships between occupational

can specialization be defined archaeologically? Processually? specialization, urbanization (measured by settlement size), and

Sociopolitically? cumulative information content of the culture (Tatje and

3. What is the nature of the evidence for specialized produc- Naroll 1973, McNett 1973). From an ecological and evolution-

tion? What criteria can be used to identify specialist production ary perspective, social stratification and economic specialization

and/or the products of specialists? reflect the differential distribution of resources and the societal

4. What kinds of "forcing conditions," environmental or management of these resources.

sociocultural, select for specialization? Ethnographic and ethnoarchaeological research has often

focused on production, frequently emphasizing a society's

1 This paper is a revised and expanded version of a paper presented manufacturing techniques or learning patterns. Identification

at a workshop on craft production held in the Department of Anthro- of economic specialists may be by any one or a combination of

pology, Arizona State University, on April 19, 1979, and a shorter

version presented in a symposium on the same topic at the 44th the following criteria: amount of time spent performing the

annual meeting of the Society for American Archaeology, Vancouver, occupation; the proportion of subsistence obtained through the

April 23, 1979. I would like to thank L. Jill Loucks for performing occupation; the existence of a recognized title or native name

most of the computations. for the specialty; and the payment of money or giving of a

gift in exchange for the product (Tatje and Naroll 1973).

Archaeological definitions of craft specialization are poorly

PRUDENCE M. RrcE is Assistant Professor of Anthropology at the developed and virtually impossible to correlate with these

University of Florida (Gainesville, Fla. 32611, U.S.A.) and Assis- criteria. Additionally, it has been difficult to understand how

tant Curator of Archaeology at the Florina State Museum. Born

in 1947, she was educated at Wake Forest University (B.A., 1969; the manufacture of pottery evolved from what may have been

M.A., 1971) and at the Pennsylvania State University (Ph.D., a typical activity performed by self-sufficient households along

1976). Her research interests are pottery studies and Lowland with a variety of other tasks into a specialized economic pursuit

Maya archaeology. Her publications include "Ceramic Con- carried out by a small number of skilled practitioners who did

tinuity and Change in the Valley of Guatemala," in The Ceramics

of Kaminaljuyu, Guatemala, edited by R. K. Wetherington (Uni- little if anything else to earn a living. It is clear that some

versity Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1978); with operational definition of craft specialization needs to be de-

E. S. Deevey, D. S. Rice, and others, "Maya Urbanism: Impact veloped for and by archaeologists.

on a Tropical Karst Environment" (Science 206:298-306); and, Craft specialization is here considered an adaptive process

with D. S. Rice, "The Northeast Peten Revisited" (American

Antiquity 45:432-54). (rather than a static structural trait) in the dynamic interrela-

The present paper was submitted in final form 3 vu 80. tionship between a nonindustrialized society and its environ-

Vol. 22 • No. 3 • June 1981 219

This content downloaded from

140.116.20.237 on Thu, 25 Nov 2021 15:13:31 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ment. Through this process, behavioral and material variety in panied by a shift from small, scattered craft shops to larger

extractive and productive activities is regulated or regularized. centralized shops (Wright and Johnson 1975:279). In a number

(This is not to say that in simpler societies there are no regu- of areas of Europe, sherds can be traced to particular kiln sites

larities in production, but only to suggest that in complex or known manufacturers (Poole and Finch 1972, Widemann

societies the variety is regulated in different ways and to differ- et al. 1975). However, the proportion of such sites is small com-

ent degrees.) This paper is based on the hypothesis that such pared with the number of ceramic-bearing sites or cultures

variety regulation is focused on the patterns of access to or (e.g., Maya, Halaf, Anasazi, Weeden Island) in which, on the

utilization of some resource, following Fried's (1967: 191) ob- basis of other indicators of social complexity, some degree of

servations on the correlation between social differentiation and specialization seems likely. The problem is how to detect spe-

the differentiation of access to resources. In other words, craft cialization in this kind of site.

specialization represents a situation in which access to a certain For pottery, there are a number of traditional lines of evi-

kind of resource is restricted to a particular social segment. dence for specialized production. Some of these suggest simply

In nonranked, egalitarian, or acephalous societies, access to that production was in the hands of a small number of particu-

resources is largely unlimited. It may be bounded by division larly skilled producers: apparent proficiency of manufacture of

of labor on the basis of age or sex. Economies are charac- certain kinds of pottery (types, forms, decorative styles; e.g.,

teristically underproductive, only a small proportion of the Maya human-figure polychromes), apparent mass production,

labor force being oriented toward "surplus" (Sahlins 1972). suggested by large numbers of identical artifacts and/or

In ranked societies, with larger absolute population size and standardized size or appearance (Morris 1974; e.g., sized bowls

greater population density, some differentiation of resource ac-, for grain distribution [Wright and Johnson 1975], homogeneity

cess may be noted (e.g., Northwest Coast fishing rights). Divi- [Adams 1970], interchangeable mold-made parts [Rathje 1975],

sion of labor is still by age and sex, and, although there may be sized Roman bowls [Rottlander 1967]), and potters' fingerprints

some low-level or incipient specialization on the basis of skill, in the clay [Barbour 1977]). In other cases, the evidence suggests

interest, or need, "no political power derives from such spe- areas of production within a site: concentrations of tools used

cialization" (Fried 1967: 115). Reciprocal gift-giving and pres- in manufacture (such as molds [Wright and Johnson 1975]), of

tation are important among ethnographically known societies, raw materials, of unfired vessels or fired vessels of identical

and prestige and leadership accrue to those who accumulate kinds (form, type, etc.), or of overfired, misfired, or broken

goods and dispose of them generously (Sahlins 1960, Firth 1965, ceramic objects (Menzel 1976). Where specific loci (such as

Oliver 1955). individual sites or residence compounds) for the manufacture

In stratified societies, division of labor is formalized and ac- of particular pottery cannot be identified, broader regions of

cess to basic or productive resources is limited. Fried (1967: production have been hypothesized on the basis of regional dis-

188-89) points to two means by which access can be restricted: tribution patterns of design microstyles (e.g., the distribution of

(1) by assigning direct rights to the use of a particular resource different widths of incised cross-hatched bands on Uruk pottery

to particular individuals or groups (generally in exchange for [Johnson 1975, Wright and Johnson 1975], Postclassic Highland

something either tangible, e.g., products of that resource, or Polychrome painting styles in Guatemala [Wauchope 1970],

intangible, e.g., loyalty) and (2) by demanding a greater return Classic Maya polychrome mortuary pottery [Adams 1970],

in goods or labor for access to specific resources on the part of Nazca-Ica polychromes [Proulx 1968]), distribution of dis-

those not granted direct use rights. tinctive technological characteristics (e.g., Maya Fine Orange

In the products and/or in the productive activities, the ob- pottery [Sayre, Chan, and Sabloff 1971], Thin Orange pottery

jective results of such regulation of access may take the form [Sotomayor and Castillo-Tejera 1963], Plumbate pottery [Shep-

of standardization (reduction in variety), elaboration (increase ard 1948], Palenque pottery [Rands 1967]), or correlation of

in variety), or both. Standardization may emphasize reduced technological and stylistic variables (e.g., Rio Grande glaze

variety in behavior and in the product. Standardization of paint wares [Shepard 1942], Late Classic Tikal pottery [Fry

utilization of raw materials, standardization or simplification 1969, Fry and Cox 1974]).

of manufacturing methods (mass production, routinization), For the study of craft specialization in pottery, more detailed

standardization of shapes, sizes, colors, etc., all would fall into attention to the raw materials and to the ceramic products

this realm. Elaboration may be exhibited in an increase in the themselves, beyond standard typological analysis, will be use-

number of kinds of goods produced (Mortensen's [1973] "in- ful. Trace-elemental studies and microscopic examination of

novation curve") and also in unusual forms, in decorative mineral constituents provide precise characterization of the

styles or motifs, and in utilization of new (and possibly rare) ceramic raw materials at a particular site and of the fired pot-

raw materials. tery recovered in excavations. What is lacking is some sort of

Thus, in complex societies, producers, production means, and theoretical structure within which these kinds of technical data

the products themselves reflect the inherent internal variety of can provide a basis for inferring the existence of specialists.

a diverse or segmented social system. Different social segments What follows is an attempt to create such a framework.

will have different demands and different degrees of ability or Variability in preindustrial ceramic products exists, first, for

means to satisfy them. It is hypothesized that the demand for the same reasons it exists in any other aspect of material cul-

such variety and the ability to obtain it will begin at the upper ture: over time and space, replication of a "mental template"

end of the social continuum. The existence of variety in kinds is never perfect. There are numerous producers with different

of goods or services and in elaboration of their appearance or skills, multiple incidents of production, multiple raw materials,

composition should vary more or less directly with social status and multiple procedures. Variability may also be the conse-

(Otto 1975). quence of social and economic processes: production of different

Identification of specialist production has been fairly straight- objects for different consuming segments; class, ritual, or ethnic

forward in complex civilizations or states (e.g., Teotihuacan, associations of decoration or form; different rates of production;

Uruk, Inca), where the socioeconomic differentiation was etc. Variability in material culture as a topic of archaeological

formalized to the extent that occupational barrios, wards, or or ethnographic study certainly has not been ignored, but at-

even shops can be found. At Teotihuacan, for example, where tempts to put it into a theoretical framework have been rela-

an estimated 25-35% of the populace was involved in craft tively few. One of the most thorough studies of variability in

production, evidences of lapidary, obsidian-working, and pot- archaeological data is Clarke's (1968) Analytical Archaeology,

tery craft barrios were located (Millon 1970). On the Susiana which treats patterned variability in attributes, artifacts, and

Plain, the shift to statehood in Early Uruk times was accom- assemblages as coded information about variability in the cul-

220 CURRENT ANTHROPOLOGY

This content downloaded from

140.116.20.237 on Thu, 25 Nov 2021 15:13:31 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

tural systems of which they are a part. 2 Rathje (1975) has pro- Rice: EVOLUTION OF SPECIALIST PRODUCTION

posed a model of changing resource management behavior

through time that is based heavily on standardization vs. vari- point in time. This may be conceptualized as the analysis of

ability in archaeological data. He suggests a change from gen- the distribution of observations on particular technological or

eral variability through standardization (mass production) to stylistic characteristics of pottery expressed as a histogram or

local instances of elaboration and diversity in the course of a a distribution curve (Clarke 1968, Johnson 1975, Rice 1978a,

system's evolution. Mortensen (1973) has developed a cumu- Stark 1979; see figure 1). Although Clarke holds that skew

lative frequency curve that shows changes in percentages of curves indicate "noise" or random error, I feel that deviations

new types (forms, styles, etc.) through time at a site, but he from the normal curve of particular attributes in a supposedly

does not suggest why these occur. Investigations of a plantation homogeneous population may indicate underlying heterogeneity

site in the southeastern United States by Otto (1975) have that can aid in identifying restricted or specialized production.

shown that higher-status residences (those of the owners) have I hypothesize that, where production of certain vessel classes

greater variability in kinds of material items in their household (ceremonial/utilitarian, stylistic, functional, formal, or what-

inventories than lower-status residences (those of overseers and ever) is limited and in the hands of specialist producers, (1) the

slaves). distribution curve of properties for that class of pottery will

Balfet (1965) has studied contemporary North African pot- be skew, with a narrow peak, (2) the curve will be multimodal

tery manufacture and found that individual household manu- and capable of being broken down into several smaller distribu-

factures tend to be diverse and variable, in contrast to the tions, which will be skew and/or positively kurtotic, or (3) both

standardized appearance of products of specialist groups. Foster of the above may be true.

(1965: 58) uses ethnographic data from Tzintzuntzan, Mexico, In all cases, the range or scale of the curve will likely be con-

to place creative innovation in a social milieu, but at the same ditioned to a large degree by two factors. One is the properties

time he stresses the role of the individual: of the resources available to and used by potters (e.g., degree

in a period of pottery style and production technique stability, all of redness by iron content, hardness by vitrification point, etc.).

knowledge will tend to become universal, and there will be no trade If specialization reflects in part restricted or regulated access

secrets. Under these conditions, pottery styles are not likely to die to resources, then the products of such specialization should

out as a consequence of what happens to only a few people [death, have a narrow range of variation in properties, reflecting the

moving out of a community, end of productive abilities, etc.]. Con- range inherent in the raw materials. Unimodality may indicate

versely, in a period of active experimentation to develop new styles the degree of consistency in achieving a desired result; multi-

and improved techniques, pottery secrets will appear which will in- modality may reflect the existence of multiple producers, each

crease the probability of loss of techniques and styles after very short

periods of production, as a consequence of something happening to with his own slightly distinctive product, or a predetermined

the person or people who alone control the secret. set of variants consistently being produced. The second factor

conditioning the range of the distribution curve is the hetero-

Clearly, variability (and its converse, standardization) may geneity of the data set chosen by the analyst. For example, is

be observed and measured in all manner of nominal, ordinal, it pottery from one site or a large region, from a 200-year phase

and metric attributes of pottery: quantity, color, form, dimen- or a 1,500-year one? The direction and degree of skewness (cen-

sions, composition (kind, size, quantity of constituents), degree tral tendency) suggests the general standard or modal product(s).

of firing, and a host of observations on manufacturing tech- It will show the existence and direction of controllable or un-

nology. Observations on variability may be made essentially controllable deviations from this standard or from concepts

synchronically (e.g., numbers of different forms, colors, or about what a particular kind of pot looks like or how it is made

decorative styles, range or standard deviation of dimensions) by particular producers (e.g., the skewing may indicate some

or diachronically (in the sense of elaboration, substitution, tendency toward overfiring, or some undersized jars, or what-

addition, or subtraction of the attribute states within any at- ever, around the modal category). The kurtosis or peakedness

tribute category through time in the ceramic complexes of a

site or region). Frequency

To examine the possibility of craft specialization, some

determination may be made of the relative amounts of variety

within segments of an archaeological ceramic complex at any

2 The following are the salient points of his work: (a) variety is in-

formation entering the system, either from outside or from a sub-

system (p. 89); (b) it may be accepted or rejected (p. 90); (c) it stems

"partly from human whim and partly from human inability to

reproduce repeatedly and exactly a given set of conditions" (p. 161);

(d) within a single artifact type and a short time period, each attribute

has a unimodal dispersion approximated by a curve varying between

the normal and a skew distribution (p. 161); (e) all the normal dis-

tributions of all the attributes can be visualized as a solid bell curve

integrating intersecting distributions arranged radially around the

centralizing values (p. 159); (f) distribution curves may vary from

the normal in skewness, kurtosis, and multimodality (p. 152); (g) a

skew curve for a homogeneous population of a given attribute may

be illusory or due to sampling errors, scale errors, and/or deliberate

directionality of error (p. 154); (h) all the states of an attribute are

simply alternative or disjunctive variety (p. 180); (i) the system

can change by increasing or decreasing the number of attributes

and/or by varying the number of attributes per artifact (increasing

or decreasing output of artifacts during the system's time trajectory

is a separate aspect at a separate level) (p. 165); (j) there is a tendency

toward increasing physical elaboration of the artifact type up to a

certain point, beyond which a tendency toward simplicity sets in

(p. 167); (kl a complex culture system is one in which more artifacts

are produced, implying a greater information content or variety FIG. 1. A model of change through time in the distribution curve of a

available for regulatory "insulation" in environmental interactions particular attribute, with changing mode, kurtosis, and spread (after

(p. 91). Clarke 1968:171, fig. 33).

Vol. 22 • No. 3 • June 1981 221

This content downloaded from

140.116.20.237 on Thu, 25 Nov 2021 15:13:31 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

of the curve indicates the degree of consistency with which this ceptable ceramic vessel in any category and (2) increasing skill

standard or mean is being achieved, or the variability or dis- of potters in achieving that standard. Multimodality vs. uni-

persion around that standard. modality in distribution may be interpretable as indicating the

Another means of conceptualizing variety is in terms of di- existence of multiple production units or single ones: in other

versity. Diversity is a descriptive concept widely used in eco- words, craft specialists.

logical studies to refer to the number, size, and/or proportion I shall propose an evolutionary model for pottery specializa-

of species in a community-its complexity or structure. A num- tion elaborated from a general sequence proposed on the basis

ber of indices exist for summarizing the complexity of a set of of study of Highland Guatemala whitewares (Rice 1976a). This

data (Pielou 1974). These indices permit measurement through model shares some general points with Rathje's (1975:414-15)

categorical or qualitative observations (e.g., species) of a in that it is based on degrees of standardization or variety in

property analogous to variance, which can be calculated only pottery. It differs, however, in stressing the incorporation of

on quantitative data. Diversity has two major components: ceramic technological data as an inferential tool in assessing

the number of species, or "richness," and the distribution of resource access and standardization of behavior and product.

individuals among the species, or "evenness." In ecology, the In this it is akin to Balfet's (1965) observations concerning

concept of diversity has a number of interpretations. High diversity versus standardization in modern North African

diversity indicates high complexity, since the existence of more pottery, comparing individual versus specialist group manu-

species permits more varied kinds of interactions. Somewhat facture.

controversial is the view that high diversity also indicates

stability-the ability to tolerate disturbance-and maturity,

reflecting the idea that at least some types of ecological com- A TRIAL MODEL

munities become more diverse (complex) as they mature.

Diversity indices have also been interpreted in terms of domi- For purposes of discussion, this evolutionary sequence is

nance (the probability that randomly selected pairs of indi- broken down into steps, but these divisions are purely artificial.

viduals will belong to the same species) and as indicators of A distinction is made between "elite" and "utilitarian" pottery,

competition and predation (the probability of an individual's but clearly a variety of overlapping functions and patterns of

encountering a member of another species) (Hurlburt 1971). production and usage are subsumed in these two categories.

Several archaeological studies in the southeastern United The terms are simply a shorthand notation, the former referring

States have used one such measure of diversity, the Shannon- to pottery that is a luxury, high-status, or prestige commodity,

Weiner (also called Shannon-Weaver, or Shannon) index, with ceremonial or special function, high value, low consump-

principally to analyze diversity of faunal remains (Wing 1963, tion, and some kind of restricted distribution, while the latter

Kohler 1978, Cumbaa 1975), but also to study diversity in refers to low-status ceramic goods of widespread occurrence,

kinds of pottery (using "types" as "species") found at a site low value, and high consumption.

with respect to living areas of Indians vs. Spanish (Kohler Step 1. Pottery making was no doubt initially a typical ac-

1978, Loucks and Kohler 1978). The interpretive potential of tivity in nearly every household. A simple technology, equal

such indices is considerable: comparison of diversity (richness access to resources, and minimal division of labor are charac-

and evenness) of assemblages from different contexts can indi- teristic of primitive economies (the "domestic mode of pro-

cate differential or preferential access to goods or patterns of duction"; Sahlins 1972). In an egalitarian or acephalous society,

exploitation or distribution. The measures of diversity could in which access to resources and consumption of goods are

also be brought into comparison of archaeological assemblages largely undifferentiated, pottery production at the household

through time or on a wider regional level for the purpose of level will likely be unstandardized, and more or less random

studying production and inferring patterns of distribution, variations are likely to occur, reflecting individual differences

status, and activity areas. Diversity of types and varieties in raw-material sources and/or methods of production.

within ceramic groups or wares or diversity of decorative styles Expectations, or test implications, for a prespecialization or

or forms within types, groups, or wares could be compared site- nonspecialization level of ceramic production would include

to-site, area-to-area, phase-to-phase, or complex-to-complex. the following:

For example, the diversity of elite vs. low-status, ceremonial 1. There should be little uniformity in technological charac-

vs. utilitarian, early vs. late, or site-center vs. site-peripheral teristics such as kinds and proportions of clays and tempers

pottery could be explored in terms of utilization of or differ- and (perhaps because of incomplete knowledge) firing condi-

ential access to, or distribution of, resources and products. tions.

There are obvious analogies to such ecological terms for popula- 2. Although similar styles of decoration and form reflect cur-

tion interactions as predation, competition, niche apportion- rent ideas ("mental templates") of what a bowl or jar should

ment-interactions which are increasingly complex in more look like, there should be variation based on idiosyncratic fac-

complex (diverse) systems. tors (skill, time spent, etc.).

Considered in terms of the distribution-curve model dis- 3. Although "use"-functional distinctions should be ap-

cussed earlier, richness indirectly reflects the range or number parent (e.g., among forms), "social"-functional (i.e., status-

of categories represented, while evenness is a more precise mea- reinforcing) differences should not be evident. There should be

sure of the peakedness of the curve (skewness would not enter no class of pottery which can be inferred to be "elite" by virtue

in directly). In the context of pottery specialization, then, high

of unusual appearance or unusual depositional context.

richness and high evenness in technological, decorative, and 4. There should be small (e.g., household) concentrations of

formal data would tend to suggest use of a variety of resources

similar paste, form, design, not an even distribution of these

and/or the existence of numerous producers; low richness and

traits over the site.

low evenness would suggest restricted access to resources, a

Step 2. Gradually potters may develop some form of low-

smaller number of producers, and/or mass production.

Thus, I suggest that the study of variety in artifacts through level informal specialization, for example, interhousehold ex-

time, conceptualized in terms of distribution curves or quanti- change of pottery where one household cannot or chooses not to

tative indices of diversity, may be a useful approach to the make pottery. Increasingly, individuals or families who by

study of production. An increase in skewness or kurtosis, or a chance or design live closer to clay sources or are better potters

decrease in evenness, is hypothesized to involve minimally (1) find themselves making more and more pottery, with which they

an increasingly narrow concept or standard, on the part of may enter into exchange relationships or gift giving. Pottery

manufacturers and buyers alike, of what constitutes an ac- manufacture may be associated with a lineage or other kin

222 CURRENT ANTHROPOLOGY

This content downloaded from

140.116.20.237 on Thu, 25 Nov 2021 15:13:31 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

group which claims some territorial and probably heritable Rice; EVOLUTION OF SPECIALIST PRODUCTION

prerogative to the exploitation of the clay deposits.

Test implications for an incipient-specialization stage would ary, ceremonial, elite residence). (c) Imitation elite pottery

include the following: may overlap the distribution of the elite/ceremonial/high-value

1. There should be increasing standardization of paste com- ware.

position in some categories of pottery, perhaps reflecting 5. Comparison of the total pottery complex of this stage

greater exploitation of particular kinds of clays or tempers that with that of preceding stages should show a significant increase

work satisfactorily and/or to which potters have use rights. in variety (diversity and "innovation curve") as increasing

2. There should be somewhat greater skill evident in the differentiation and complexity in the system itself generate

technology of production and/or more consistency in manu- increasing variety in the ceramic subsystem. (Technological

facturing and firing. standardization appears in elite pottery; in other kinds, increas-

3. Decorative motifs and styles should be less variable, with ing rather than decreasing richness and evenness reflect com-

accepted conventions as to motif, color, placement, and execu- petition for resources, or status, for buyers.)

tion. Step 4. In stratified societies, social and economic variety are

4. There should be wider areal distributions of the increas- highly evolved toward standardization of behavior and prod-

ingly standardized products. ucts. Much economic interaction may be taking place not as

Step 3. Over the long term, socioeconomic differentiation and free exchange but as tribute exacted by a chief. Sahlins (1972)

ranking proceed; goods are accumulated and disposed of by has called attention to the relationship between increasingly

certain more highly competitive, productive, and upwardly centralized leadership and the beginning of surplus production.

mobile sectors of the society. Productive resources are generally It is at the point when an elite begins forcibly extracting pottery

controlled by "localized self-sufficient kin-oriented social units" as tribute and/or for trade that intensified rural production

(Dumond 1972:299). Gradually such control may be appropri- begins. Some contemporary peasants, for example, will intensify

ated by emerging elites as part of the basis for their emergence; production and specialize toward the creation of a "surplus"

resource control is "the geographical expression of social struc- only if compelled to by the forcible removal of such surpluses

ture" (Nash 1966:34). "Pooling" of goods (Pires-Ferreira and by a coercive higher power as a political elite or ritual structure

Flannery 1976; cf. Peebles and Kus 1977) is likely and will be (Smith 1974, Wolf 1966).

evident earliest in elite or prestige commodities and/or scarce Test implications for this stage would include the following:

resources. Because of the systemic interrelationships of all seg- 1. It should be possible to identify standardized locations of

ments of society, these changes eventually make their impress pottery making (craft "wards" or "barrios") and perhaps,

on pottery. Competition and rapid differentiation among social through time, a reduction in their number and an increase in

groups may result in great innovation and elaboration of pot- their size.

tery. For potters this may be a time of growing insecurity or 2. There should be indications of mass production such as

pressure as the demand for elite, ritual, or mortuary pottery (a) tools facilitating rapid and uniform production (e.g., molds),

increases and perhaps calls for increased production. The con- (b) standardized form dimensions, details, and/or sizes, par-

sequences are likely to be felt first in the area of elite goods. ticularly in utilitarian wares, (c) vessel forms that stack or nest

Commodities based on scarce resources are probably increas- easily for compact storage and transport, and (d) storage areas

ingly channeled into the hands of the emerging elite, both in for raw materials and finished products in quantity.

terms of access to the resources for their manufacture and in 3. There should be a broad distribution of standardized

terms of use of the finished product (personal use, gift giving, forms, types, etc.

trade). Thus,'the production of elite or special-function or high- 4. Nonelite classes of pottery should show standardized

value ceramic goods is the first in which specialization will take pastes.

place. Exchange of these goods may be through a system of 5. There should be evidence for elaboration in decorative

circulation distinct from that of subsistence goods (Bohannan aspects of elite/ceremonial/high-value pottery: more colors

1955, Salisbury 1962), further reinforcing social distance and used, more decorative motifs, greater freedom or elaboration

ranking distinctions. Also, elite goods may be traded out of in their placement and combination, greater variety in their

the society through networks controlled and maintained by the mode of execution (painting, incising, modelling), and so forth.

elite. (This is the ceramic expression of the third stage of Rathje's

Expectations or test implications for this stage would include [1975:415] trajectory: the generation of increased variety in

some of the following: specific products at the local-in this case, elite-level.)

1. There should be unequal distributions of classes of pottery, These four steps are summarized in table 1.

that is, an association of certain classes of pottery with elite

and related lineages (the beginnings of "social" functional or

status-reinforcing distinctions in pottery). A TEST OF THE MODEL

2. Elite/ceremonial/high-value goods should be distinguish-

able in part by decorative characteristics-a greater variety A test of some of, these propositions was attempted using the

of kinds and complexity of decoration, greater skill in execu- ceramic analysis and typological descriptions of material from

tion, and perhaps rare or exotic materials (e.g., paints) or the Maya site of Barton Ramie in Belize (Gifford 1976). The

motifs. ceramic descriptions were tabulated in a number of relevant

3. These elite/ceremonial/high-value goods should be dis- categories for each of five complexes in the sequence; a sixth

cernible technologically: (a) Within classes (e.g., form), paste complex, Floral Park, which marks the apparent intrusion of

characteristics should be relatively standardized or uniform. foreign elements into the indigenous tradition, was eliminated

(b) New pastes in standard elite formal or decorative styles from the calculations. Tabulations included variability in the

may appear, suggesting imitation wares and/or competition following classificatory (type-variety system) and descriptive

among producers. data: (1) number of wares; (2) number of groups; (3) number

4. Elite/ceremonial/high-value goods (as defined techno- of types; (4) number of varieties; (5) number of different

logically above) should also be distinguishable with respect to details of form noted for vessels within a type (including such

their uneven areal distribution: (a) Pottery with standardized categories as different kinds of bowls, jars, etc., but also details

paste should be found in more restricted areas of a site or of rim and lip and presence of handles, supports, or flanges);

region than pottery with more variable composition. (b) Such (6) number of different characteristics of pastes, including vari-

pottery should also be found in particular contexts (e.g., mortu- ants of temper, color, texture, thickness, firing, etc.; (7) number

Vol. 22 • No. 3 • June 1981 223

This content downloaded from

140.116.20.237 on Thu, 25 Nov 2021 15:13:31 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

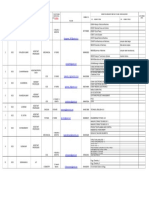

TABLE 1

CERAMIC VARIABILITY AS AN INDICATOR OF SPECIALIST PRODUCTION

CERAMIC ATTRIBUTE CLASS

CULTURE PASTE DECORATION"

COMPLEXITY

CONTINUUM Utilitarian Elite/ Ceremonial Utilitarian Elite/ Ceremonial

Arephr Variable Variable

Less variable Variable Standard motifs and

execution

Ranked

Competitive variety Standardized Competitive variety

l

Stratified Standardized (mass-

produced)

Standardized Standardized (mass-

produced)

Elaborated

NOTE: The cells represent continua rather than discrete steps.

• Including comparatively minor variations in details of form (lip, base, etc.).

of decorative variants, excluding motifs but including method The evenness component of diversity presents a slightly

of execution, such as incising, punctation, painting, and decora- different picture (fig. 3). In the Preclassic the unslipped groups

tive additions (e.g., flanges, appliques). have greater evenness than the slipped, reaching a peak in the

Variability between complexes was compared by calculating Late Preclassic and declining thereafter. Slipped groups have

richness and evenness for each complex using the Shannon- an undulating curve, peaking in the Early Classic, declining in

Weaver diversity index, with natural log base (the resultant the early Late Classic, and then rising above the curve for the

figure expressed in units called "nats"). Richness was mea- unslipped in the late Late Classic. High evenness suggests the

sured by the formula ii= - "I-(n1/N) log (n1/N) and evenness existence of a broad spectrum of acceptable ceramic categories,

by the formula H/Hmax• Form, technological, and decorative with little preference for or selection of particular ones. A

variability were calculated as the number of variants divided variety of products, a variety of producers, and/ or lack of

by the number of sherds in the major type of a ceramic group, standardization are possible explanations for such a situation.

multiplied by 1,000, i.e., as number of variants per 1,000 Low evenness suggests greater selectivity, functional or status

sherds. Except in the decorative variant calculations, groups specialization of certain kinds of products, the existence of

containing fewer than 225 sherds were excluded to avoid dis- specialized producers, and/ or the standardization of certain

tortions caused by excessively small sample size. The trends categories of products. By such logic, it would appear that at

exhibited in these calculations are shown in table 2 and figures Barton Ramie greater evenness in the Preclassic unslipped

2 through 7. The scale of the x-axis is in years, subdivided into

the phases identified for the site. The figures obtained by the 1.7

calculations have been placed at the midpoints of each phase.

Comparing the complexes as a whole through time, it is clear 16

that the richness component of diversity increases (table 2);

there are more wares, groups, and types represented in the col- 15

lections, as well as more sherds in general. The number of

varieties stays roughly the same, however. The ceramic system 1.4

is becoming more complex, with more and larger units. More

pottery is being made, filling a greater variety of more special- 1J

ized functions for a greater body of consumers.

12

Variability within complexes may be compared by calcu-

lating richness (ii.) for slipped versus unslipped ceramic groups

in each complex. The slipped wares (fig. 2) show increasing

diversity, reaching a peak in the Early Classic, declining in the

10

early Late Classic, then rising again. The unslipped groups

likewise peak in the Early Classic but decline steadily in sub-

sequent phases, and their diversity is considerably below that

of the slipped groups.

TABLE 2

NUMBERS OF STANDARD TYPOLOGICAL UNITS IDENTIFIED FOR

EACH CERAMIC COMPLEX AT BARTON RAMIE

VARIETIES

CERAMIC

COMPLEX SHERDS WARES GROUPS TYPES Named Total

800 700 600 500 400 JOO 200 100 0 100 200 JOO 400 500 600 700 800

Mount Hope- T,- Spanish

Jenney Creek . 7,452 3 6 15 15 41

Barton Creek. 8,065 3 6 17 7 42

Jenney Creek

Middle

Barton Creek

Late

Floral Park

Termtnal

Hermitage

Early

'"

R"" Lookout

Late

Hermitage._ .. 29,211 4 12 25 21 42 Preclass1c Classic

Tiger Run .... 21,014 3 11 24 18 43

Spanish

FIG. 2. Ceramic group richness as expressed by ii. Solid line, slipped;

Lookout. .. _ 57,703 6 17 42 28 so broken line, unslipped.

224 CURRENT ANTHROPOLOGY

This content downloaded from

140.116.20.237 on Thu, 25 Nov 2021 15:13:31 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Rice: EVOLUTION OF SPECIALIST PRODUCTION

followed by an increase, then a similar sharp decline and rise in

unslipped, then black, and finally polychrome (no rise is noted

I0 in this last category). It is interesting that the unslipped groups

exhibit a marked rise in variability in the Late Preclassic, prior

to the decline, suggesting an increase in producers, resources

used, and/or manufacturing methods prior to rapid stan-

dardization.

Decorative variability was measured in two ways. One way

was analogous to measurement of form and technological

variability-i.e., simply by counting the number of decorative

j modes and dividing by the number of sherds per type (fig. 6).

Unslipped groups are very low in decorative variability, as

might be expected. Both black and red groups rise sharply in

decorative variability from the Middle to the Late Preclassic,

after which red groups rise further to a peak in Tiger Run, then

decline markedly in Spanish Lookout. Black pottery declines

in decorative variability to a low in Tiger Run and then

increases. Polychromes likewise drop from Early Classic to

early Late Classic, then rise steeply in Spanish Lookout.

The second way of looking at decorative variability was

somewhat less direct. This was to count the number of named

and unspecified varieties within all groups in a complex (i.e.,

the number of varieties within red groups, within unslipped

800 700 600 500 400 300 200 100 0 100 200 300

400 500 600 ' 1'00 800

groups, etc.), on the premise that the formal naming of varieties

Jenney Creek

I Barton Creek

I

Mount Hope-

Floral Park Hermitage IT1-

ii~n

Spanish

Lookout or designation of potential' varieties is often (though certainly

Middle I Late I Terminal Early I Late not always) on the basis of decorative variation. In these cal-

Preclass1c Classic culations (fig. 7), the unslipped show a sharp rise in the Late

Preclassic (like the rise in technological variability in unslipped

FIG. 3. Ceramic group evenness as expressed by ii/ H max.; Solid line, groups at this time) and then a sharp decline, followed by a

slipped; broken line, unslipped. slight rise in Spanish Lookout. Red groups decline continuously

throughout all phases, reaching lows close to that of unslipped

groups in the Late Classic. The decorative variability curve of

groups argues for a lack of specialization or standardization black groups closely corresponds to the curve for form vari-

and the existence of a variety of producers, whereas by the Late ability, declining from the Late Preclassic to the Early Classic,

Classic production of all ceramic categories was probably far

more standardized. Explanation of what is going on in slipped

groups, especially the rise in evenness in the Late Classic, is

more complex. A greater number of slipped groups occurring

in approximately equal quantities suggests more producers

competing in manufacturing a greater variety of products for 30

a greater variety of consumers or functions. I suggest that this

elaboration parallels the elaboration within the social hierarchy

that was occurring in the Late Classic period (cf.Joyce Marcus's 25

[personal communication) observation that the site hierarchy

in the lowlands evolves from two to four levels). Competition

for status is likely to be reflected in competition in producing 20

more and different kinds of status goods, slipped pottery being

among these goods.

Form variability was examined for unslipped, red, black,

15

and polychrome groups (fig. 4). It is lower in the unslipped

groups in all but the Late Preclassic and Early Classic com-

plexes, showing a gradual decline from Jenney Creek to Tiger

Run, at which point it levels off. The slipped groups show a IO

pattern of decline in variability, slight increase, then decline

again. The increase occurs earliest in red pottery, in the Early

Classic. If the model holds true, the slipped groups, red first,

may be elite wares beginning the trend toward standardization.

The transition occurs more gradually in the unslipped groups

(perhaps unslipped pottery continued to be made by a variety

of producers), but these are ultimately more standardized than

any of the slipped wares save the polychromes. In the Late

Classic, red wares serve a variety of utilitarian functions (per- Jenney Creek Barton Creek

Mount Hope-

Floral Park Hermitage

Ti-

il~n

Spanish

Lookout

haps storage/serving-forms are primarily large bowls and Middle Late Termmal Early Late

jars) and in their variability may be more like unslipped than Predass1c Classic

like black and/ or polychrome.

In technological characteristics (paste composition, texture, FIG. 4. Form variability of major type in each group. Solid line, black;

color, firing, thickness) a similar sort of pattern emerges (fig. 5). broken line, red; broken and dotted line, polychrome; dotted line, un-

There is a sharp decline in paste variability in red wares earliest, slipped.

Vol. 22 • No. 3 • June 1981 225

This content downloaded from

140.116.20.237 on Thu, 25 Nov 2021 15:13:31 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

and the Late Preclassic. This increase occurs in paste and

40

\ decoration though not in form. I suggest that at this time red

\ wares as an elite, special-access or special-function class of

35

\ pottery may have 'been manufactured by fewer people, but a

large number of potters were making unslipped utilitarian

\ wares. Forms were becoming slightly standardized, but a wide

\

30

\

,.

"1 range of technological characteristics and decorative styles (in-

cluding incising, appliques, painting, polishing, etc.) suggest a

lack of pressure toward conformity, a variety of acceptable

\ I \ I: styles or personal tastes, and probably a large number of pro-

25 \ I

I \

\ ducers. Additional insights into this phenomenon come from

\,' ' \ I: the fact that the Late Preclassic has in many areas been de-

I

,\ \

\

\ I

scribed as a period of population growth, land shortage, and

general social stress. One response to this kind of stress may

20

I

I

\ \

\ have been for a greater number of people to go into the pottery

I

I

I

\

\

\ I business, especially producing low-value/high-consumption

---

\

I goods.

15

I

I \ \

y_......___l"-. \

\ I

The other deviation is that in form and paste (and, in black

I

I

\....- \

\

\ :, groups, in decoration) the sharp decline in variability noted

\ first in red groups is followed characteristically by an increase

IO

\ x'\ in variability, which in most cases then declines further (an

\ ____ / \1 exception is the increase in paste variability in black and un-

\I slipped groups in Spanish Lookout). These peaks of variability

may represent the competitive variety generation noted in

800 700 600 500 400 300 200 100 0 100 200 300 400 500 600 Joo 800

Step 3 of the model following initial standardization of elite

I wares, or Rathje's (1975) increased diversity on local levels. In

Jenney Creek

I Barton Creek

I

Mount Hope-

Floral Park Hermitage

Ti-

ii~n

Spanish

Lookout

black groups and in polychromes this increase occurs in the

Middle

I Late I Termmal Early I Late

Preclassic Classic

Classic following the Floral Park intrusion (whose potential

ceramic consequences have been ignored in this exercise), and

FIG. 5. Technological variability of major type in each group. Solid some of the increased variety may be due to forces in the

line, black; broken line, red; broken and dotted line, polychrome; ceramic system created by that intrusion. Another view of this

dotted line, unslipped. increased variability may again tie in to competition within

the social system. As a new class of ceramics (for example, poly-

chromes) enters the system and is identified primarily as an

rising in the early Late Classic, then declining again in Spanish elite or special-function good, other ceramic categories (e.g.,

Lookout. Polychromes, predictably, show the highest decora-

tive variability throughout the Classic, but even that declines

in Spanish Lookout.

How might all these computations be construed as a test of 180

the model? In very general terms, the x-axis on the graphs

represents time, the y-axis variability. Peaks in the graphed

I

lines for each ceramic category (e.g., group) indicate increased

variability, and the position of each category relative to

160

I

others indicates relative variability on particular characteristics 140 I

(e.g., form, paste, decoration) vis-a-vis other categories.

Through time, diversity in the sense of richness, i.e., more

120 \/ :

iv

differentiation through more categories, has been seen to in-

crease, except on the varietal level. But when variability in three - J\ A

major ceramic attribute classes (form, paste, decoration) is 100 ,--- - ·-✓ .I

measured through time, controlled by the size (number of / I

sherds) of the ceramic units involved, patterns of increasing I

standardization can be seen.

80

/ I

Red groups show the earliest and most abrupt decline, one I I

that occurs in all variables (paste, form, and one of the decora- 60

tive measurements) considered. This may indicate the re-

I

stricted access to resources and earliest standardization of elite I

or special-function categories of pottery hypothesized in Step 2

40

I

of the model. Similar sharp declines in all categories of vari-

ability show up successively in unslipped, then black, and 20

finally polychrome groups as the manufacture of these becomes

increasingly routinized. It is perhaps significant that by Spanish

IO

--- ----

Lookout the red groups are at the same level of variability as

utilitarian unslipped groups (and in paste variability are even 800 700 600 500 400 300 200 100 0 100 200 300 400 500 600 roo 800

lower); given the kinds of forms represented (jars and large Mount Hope- T1- Spamsh

bowls), this suggests that sometime during the Classic red

Jenney Creek

I Barton Creek

I Floral Park Hermitage Jil:n Lookout

Middle I Late I Tennmal Early I Late

wares became major utilitarian types (perhaps still elite or high- Prec\ass1c Classic

status).

Two exceptions to the general trend toward standardization FIG. 6. Decorative variability of major type in each group. Solid line,

through time may be seen. One occurs in unslipped groups, black; broken line, red; broken and dotted line, polychrome; dotted line,

where there is a sharp increase in variability between the Middle unslipped.

226 CURRENT ANTHROPOLOGY

This content downloaded from

140.116.20.237 on Thu, 25 Nov 2021 15:13:31 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Rice: EVOLUTION OF SPECIALIST PRODUCTION

90

further difficulty is that the test of some of the model's proposi-

80 tions was not performed on an ideal data set.

The advantage of the model is its capacity for making craft

70

specialization operational for archaeological study diachroni-

cally and synchronically. It combines new kinds of ceramic

technometric methods and data (on paste composition and

60 I

"\

I \

firing) with more traditional types of ceramic analysis (form,

I \

I \ decoration, "typology," style). A major synchronic focus is on

50

I

I \

\ \ the study of ceramic variability through the distribution, range,

I \

/ \ and covariation of measurements of certain properties, such as

"-._ I \ amount of temper, hardness, degree of firing, color, mineralogy,

'- I \

40 Y, \ and chemical composition. This identifies the standards or cus-

I '-... \

--

I '-.. \ toms which potters recognized and more or less consistently

JO

/ ........

..__ \

\

adhered to through differential exploitation of raw materials

and the skilled manipulation of those materials. Further, since

\

\

-....-.\.... many of these variables may be related directly to raw materials,

20

\-\ comparable measurements on properties of raw clays and fired

pottery can undeniably be useful in trying to pinpoint areas of

\ \ manufacture by identifying resources used.

10

\ \ Pottery specialization is hypothesized to begin in the area of

\ .... _,,,,,,,.,,,,.

"'><

elite/ceremonial/high-value products as a function of differen-

tial access to resources and increasing concentration of power

or wealth in a particular social segment. It is hypothesized to

be first manifested in standardized paste attributes (composi-

Jenney Creek Barton Creek

Mount Hope--

Floral Park

tion and firing). While the test of the model showed that in red

Middle Late Terminal Early Late groups at Barton Ramie reduction in paste variability was ac-

Preclass1c Classic companied by reduction in form and decorative variability, it

might be argued that the ca. 900 years from the beginning of

FIG. 7. Decorative variability of major type in each group. Solid line, the Middle Preclassic (Jenney Creek) to the end of the Late

black; broken line, red; broken and dotted line, polychrome; dotted line, Preclassic (Barton Creek) does not provide sufficient temporal

unslipped. sensitivity to demonstrate the primacy of technological stan-

dardization.

With growing sociocultural differentiation there are probably

black wares) may increase in elaboration to meet the demand idiosyncratic fluctuations of periods of competitive variability

for such elaborated or status goods, perhaps in "middle-class" in terms of exploitation of new resources, new methods, new

goods or by a sort of hybridization process. In any case, the forms. or new decorations. In stratified societies behavior,

increased ceramic variety reinforces the idea of heightened methods, pastes, and forms are highly standardized, particu-

variability in general resulting from a progressively more di- larly in low-value/high-consumption utilitarian goods, with

verse and complex cultural system. It also suggests the existence pottery production increasingly an exercise in mass production

of competition between producers and/ or the organizers of pro- and cost control. Elaboration exists chiefly in the area of elite

duction for resources and for status, the existence of imitations, or ceremonial goods, where access to rare resources and the

the creation of new specialized functions in which pottery is financial rewards for skilled artisans or innovators can make

necessary, and so forth. such costly (in time and resources) activities feasible.

SUMMARY

Comments

The model proposed here considers ceramic craft specialization

as a systemic process evolving in tandem with the other social, by WILLIAM Y. ADAMS

political, and demographic changes subsumed under the head- Department of Anthropology, University of Kentucky, Lex-

ing of sociocultural evolution, differentiation, and complexity. ington, Ky. 40506, U.S.A. 2 XI 80

It represents the process of gradual selection of or restriction I cannot evaluate the reliability of Rice's model with reference

to a particular occupational mode out of the alternative possi- to her own Maya data, except to suggest that her "test" seems

bilities presented by environmental diversity or scarcity and to involve a good deal of intuitive judgment. In the broadest

the culturally conditioned perceptions of that environment. sense the model does seem applicable to the Old World ceram-

Specialization is an evolving part of the processes of centraliza- ics that are more familiar to me. Here the emergence of state-

tion and segmentation, not merely the result of these processes. level society was concurrent with the introduction of the pot-

It is an adaptive process of regularized socioeconomic inter- ter's wheel (Childe 1954:198-204), supplementing but not

relationships for productive utilization of a society's environ- fully supplanting the older technique of building by hand. The

ment. result was a quantum increase in the sheer volume of pottery

A number of questions have not been addressed by this and, of course, in the variety of forms and wares, while at the

model: the role of part-time vs. full-time specialists and how to same time the products of individual factories came to show

distinguish them archaeologically; whether control is central- a high degree of standardization.

ized or decentralized; what the motivations are for intensifica- A practical limitation in Rice's approach would appear to

tion and surplus production. In addition, the model, in its crude lie in the difficulty, in many areas, of defining appropriate

formulation here, essentially presupposes unilineal evolution boundaries within which to measure ceramic variability. Her

from acephalous through ranked to stratified societies. A own material is, I take it, all derived from one site in Belize,

Vol. 22 • No. 3 • June 1981 227

This content downloaded from

140.116.20.237 on Thu, 25 Nov 2021 15:13:31 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

but we are not specifically told that this is a meaningful unit concepts from the realm of biotic-community ecology to that

of study. I know of a good many individual sites in which the of sociocultural behavior, and Rice's employment of the rich-

ceramics do not provide an accurate reflection of variability ness/evenness measures to some extent illustrates why. Apart

in the surrounding region (Adams 1978), even though there from the selective-adaptive implications of the measure, it

was a close systemic integration between the town and its en- seems questionable whether archaeological ceramic richness

virons. and evenness can be interpreted in terms of degree of pro-

Ceramic material from ancient Egypt suggests another im- duction specialization rather than as a function of various

portant caution: the emergence of social and political elites interacting factors involving availability, marketing, access,

does not invariably result in the production of "elite" pottery and deposition as well as production mode and desirability.

wares. During most of Egyptian history, and down at least to Rice makes innovative and imaginative use of published

Roman and Byzantine times, pottery was not developed as an type-variety data in her own "test" of the proposed model and

artistic medium or as a status symbol. Even the royal tombs by so doing instructively demonstrates the potential of such

have not yielded vessel forms or styles that cannot also be typological data for manipulation and use beyond what their

found in the tombs and dwellings of peasants. The blue- generator may have had in mind. I must question the conclu-

painted "Amarna ware" of the 18th Dynasty (Lucas and Har- siveness or even the validity of her test, however, on the

ris 1962 :384-85) represents a partial exception, but it is the grounds that the Barton Ramie ceramic-complex richness and

proverbial exception that proves the rule. evenness distributions described by her are far more likely

The author is clearly aware that her model provides only attributable to depositional and use-related factors than to

a partial explanation for increases ( or decreases) in ceramic those of production mode. Rice's model fails to allow for the

diversity and standardization. Viewed from the opposite di- filter effect on the archaeological record of such factors as

rection, this means that such increases cannot themselves be intercommunity marketing modes, intracommunity access limi-

viewed a priori as evidence for the development of more com- tations, item availability, and item consumption levels, among

plex and differentiated socioeconomic systems. My own work others, while her Barton Ramie test ignores the effects of

with medieval Nubian ceramics has demonstrated that there intrasettlement social and functional variability and archaeo-

were major fluctuations in the amount of diversity and of logical sample derivation. That her richness/evenness indices

standardization that were unaccompanied by significant changes have some interpretive significance I do not question. What

in the social, political, or economic spheres (Adams 1979). At I doubt is that this is in any direct and facile manner relatable

some periods nearly all vessels were decorated (thereby pre- to production mode. Similarly, Rice's model overall is valuable

senting added scope for stylistic diversity), while at other as a trial step toward addressing a research question of de-

periods the majority were undecorated; at some periods the cided interest to prehistorians. What it requires by way of

Nubians were receiving pottery from several different factories, improvement is a clearer, more sophisticated recognition of

while at others their material came nearly all from one source. and means to control for the numerous factors generally oper-

Within a span of a few centuries the number of vessel forms ating between the systemic production and the archaeological

in regular use fluctuated between a low of about 20 and a high recovery of prehistoric pottery vessels.

of about 80.

The ultimate limitation of Rice's model, in my view, is ex-

pressed in the first paragraph of her summary. "The model ... by WHITNEY M. DAVIS

considers ceramic craft specialization as a systemic process Department of Egyptian and Ancient Near Eastern Art,

evolving in tandem with the other social, political, and demo- Boston Museum of Fine Arts, 475 Huntington Ave., Boston,

graphic changes subsumed under the heading of sociocultural Mass. 02115, U.S.A. 10 x 80

evolution, differentiation, and complexity." But evolving craft Although unnecessarily encumbered with jargon, this paper

specialization does not have entirely predictable results in the does ask the right questions. The conclusions, however, do not

areas of stylistic diversity and uniformity, because to some particularly advance understanding, although in the current

extent style always marches to its own drummer. The anthro- climate of theory this is not wholly Rice's fault. In this short

pologist Kroeber ( esp. 1944) and the sociologist Sorokin space I cannot adequately substantiate my criticisms, as I

( 193 7) stand almost alone among social scientists in their cannot detail the alternatives.

efforts to deal with the problem of variable creativity in other One fundamental difficulty arises from assuming too close

than material terms. Their efforts have often been condemned a connexion between social complexity, social stratification,

as unscientific (cf. Harris 1968:330-31), but in my view they and craft specialization. Cross-cultural study shows that craft

deserve praise rather than blame for venturing onto ground specialization may appear in what the author's evolutionary

where few of their colleagues have dared to tread. In a more scheme would call a "simple" society. Here, the economically

limited way I have tried also to deal with certain troubling or technologically simple basis of specialization may conceal

patterns of stylistic fluctuation in Nubian culture that do not extremely complex relations of some other kind. In the lan-

respond readily to determinist explanations (Adams 1977: guage of this paper, economically "equal" individuals can be,

671-78). and often are, differentiated by other determinants. Rice makes

Rice has developed, I would conclude, a useful ad hoc model passing reference to some of these-"skills, interests, and

to frame her own data, but its practical applicability in other needs"-and I wish she had developed the point. Within the

areas remains somewhat doubtful. narrow frame of reference she adopts it seems a contradiction

to speak of "specialization" in a simple society: yet as the

point must be made empirically, our theory must allow for it.

by JOSEPH w. BALL "Skills, interests, and needs," unpredictable at the most vul-

Department of Anthropology, San Diego State University, gar (and uninteresting) economic level, vary from individual

San Diego, Calif. 92115, U.S.A. 14 XI 80 to individual for powerful biological and psychological as well

Rice's paper represents an interesting and worthwhile approach as social and cultural reasons and may leave an archaeological

to a question of much concern but little resolution among pre- trace only very indirectly. Nonetheless, a discussion of the

historians. Her background review of nonsubsistence produc- origins and evolution of craft specialization would take these

tion specialization is useful, and her model itself, if not exactly seemingly irrational intangibles as a better point of departure

innovative, is thought-provoking and deserving of field testing. than the peculiar formalization Rice has adopted. This ac-

I am frequently left uncomfortable by the facile transfer of count, assumed with little supporting argument, apparently

228 CURRENT ANTHROPOLOGY

This content downloaded from

140.116.20.237 on Thu, 25 Nov 2021 15:13:31 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

regards craft specialization as a certain rational organization Rice: EVOLUTION OF SPECIALIST PRODUCTION

of labour in relation to resources and goes so far as to claim

that segments of society "grant" one another "resource rights." that assumed from the beginning. Apart from the fact that the

Although I am aware of the anthropological tradition from situation varies widely from culture to culture, we face a

which these ideas come, this is appallingly muddy. We are not problem in the idea of a "type" which becomes more or less

told, for example, who within a society holds these notions "standard" in craft production. What we can detect quanti-

about his own activity or circumstances or why he should tatively about the type may suggest to some observers that

do so. Rational motives may of course operate unconsciously, production is standardized, but standardized "types" and

but in this more important regard we are not told whether the "styles" may be themselves canonical or precanonical, conven-

rational self-interest of a particular ( and dominant?) social tional or unconventional. We should want to give each of these

group or a rational division of labour adopted by all self- possibilities a different index of value in interpretation. In

interested groups in a society should be held responsible for other words, the social or historical context may not be pre-

this "regulated and regularized" system of access to resources. dictable from the so-called quantitative data, and production

Defining craft specialization as a pattern of access to re- per se may reveal nothing about meaning or context.

sources in which "a certain kind of resource is restricted to a Adding this statistically useful but dangerously simplifying

particular social segment" allows the author to launch various notion of variability to the "access-to-resources" definition of

schematic and statistical proposals-although the reader won- craft specialization, we get a remarkably involuted hypothesis:

ders about various possibilities which seem to have been tacitly "if specialization reflects in part restricted or regulated access

discounted. How do we talk about two crafts using the same to resources, then the products of such specialization should

resource, or about two competing branches of one craft using have a narrow range of variation in properties, reflecting the

multiple resources? And how widely do we want to understand range inherent in the raw materials." The logic or necessity

a "resource"? Should labour be included? What about items of this proposition eludes me. Perhaps it is only a tautology:

manufactured by others but required in further manufacture? by definition, a resource cannot "produce" a manufactured

In technologically "simple" societies, the subtleties of private item with properties it is impossible to develop from that re-

interdependence, from which political structures and ritual source. No matter how specialized or learned, the alchemists

activities often derive, may be based upon such "layering" of couldn't make gold from stones. That the products of special-

resources and kinds of access to them. And in the complex ization should have narrow ranges of properties (from example

"stratified" societies, many different resources are exploited to example) because of the restricted access to resources does

for the subordinate as well as for any elite group: indirectly not follow at all and says nothing about the fact that some

but no less importantly, society as a whole possesses "access" resources are almost infinitely plastic and the repertory of

to resources which may be confronted materially by only a finished products may exhibit (statistically) an incredible

small segment of society. A more generous notion of "access" variability. Exactly where pottery's possibilities and limitations

to resources would enable us to see that the effect-and pur- may fall in this regard, although crucial to the argument, is

pose ?-of craft specialization is to broaden, manyfold, overall a matter not really addressed. And finally, specialization as

social access to resources. Furthermore, the segments of so- such has nothing necessarily to do with variability, at least by

ciety engaged in material contact with the unworked resources the terms of this proposition; the products of nonspecialists

to some often critical degree are constrained by those seg- could be just as determined by the inherent properties of and

ments which obtain only indirect access but use the worked access to the resources as specialist products.

resources. There is thus no special reason to expect craft spe- Perhaps Rice senses the slipperiness of all of this; next we

cialization to be simply or specifically associated with an elite are introduced to variability slightly redefined as "diversity."

capable of extracting obedience from other social groups. Possibly "comparison of diversity ... of assemblages from dif-

Social groups exercising other than elite political or eco- ferent contexts can indicate differential or preferential access

nomic power-for instance, religious, ritual, artistic, or bio- to goods or patterns of exploitation or distribution." The

logical power-may command access to certain resources and problem would then be to derive specialization from this re-

directly or indirectly constitute a craft specialty. Rice's model lationship. Here, not surprisingly, we fall back again on the

will not help us to predict or identify such cases; only full- identity of standardization and specialization adopted earlier:

scale analysis of the routine, the social, the- artistic, and the "low richness and low evenness would suggest restricted access

psychological function and meaning of the various products to resources, a smaller number of producers, and/or mass pro-

will do. (Social structure and material culture can be mutually duction." Once again, one can conceive of craft specializations

illuminating, but a level of meaning always mediates.) Sadly, in which the mirror reverse holds true, with "high richness"

the meaning of what is made is hardly approached in this (that is, many types) at "high evenness" (that is, almost

paper. equally dividing up the total number of individual examples

Clearly, many of the author's assumptions have been adopted made at any given time). Examples of what I mean here would

because they might help us to predict what sort of trace a include many classical and earlier Mediterranean pottery work-

craft specialty will leave in the archaeological record. Rice shops and, interestingly, many early flint- or stone-working

seems to me to move beyond the problematic initial definitions sites.

to phrase the archaeological problem clearly. Other determi- Although theoretically absolute diversity is possible, and

nants (not ideal in themselves) are now brought in. Even at theoretically "richness" and "evenness" are useful character-

this level, however, the narrow conception of stratification and izations of this "world," for other reasons having to do with

specialization creeps in. genetic, functional and morphological, and environmental con-

Rice feels that variability results from slight deviations ac- straints actual observed habitation occupies very narrow cor-