Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Weight-Based, Insulin Dose - Related Hypoglycemia in Hospitalized Patients With Diabetes

Weight-Based, Insulin Dose - Related Hypoglycemia in Hospitalized Patients With Diabetes

Uploaded by

Puri PuriCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Cambridge Research ProposalDocument3 pagesCambridge Research ProposalRocky Balbowa100% (1)

- Stuxnet and Its Hidden Lessons On The Ethics of CyberweaponsDocument9 pagesStuxnet and Its Hidden Lessons On The Ethics of CyberweaponsprofcameloNo ratings yet

- Insulin Therapy For Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus.Document11 pagesInsulin Therapy For Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus.Clarissa CozziNo ratings yet

- Practical Insulin: A Handbook for Prescribing ProvidersFrom EverandPractical Insulin: A Handbook for Prescribing ProvidersRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- ReligionsDocument4 pagesReligionsPia Flores67% (3)

- Weight-Based, Insulin Dose - Related Hypoglycemia in Hospitalized Patients With DiabetesDocument6 pagesWeight-Based, Insulin Dose - Related Hypoglycemia in Hospitalized Patients With DiabetesPuri PuriNo ratings yet

- Insulin Analogs Versus Human Insulin in The Treatment of Patients With Diabetic KetoacidosisDocument6 pagesInsulin Analogs Versus Human Insulin in The Treatment of Patients With Diabetic KetoacidosisrosieveliaNo ratings yet

- Indikasi Insulin InfusionDocument7 pagesIndikasi Insulin InfusionnikeNo ratings yet

- Marvin Et Al 2016 Minimization of Hypoglycemia As An Adverse Event During Insulin Infusion Further Refinement of TheDocument7 pagesMarvin Et Al 2016 Minimization of Hypoglycemia As An Adverse Event During Insulin Infusion Further Refinement of TheChanukya GvNo ratings yet

- Insulin Pump Therapy in Children and Adolescents - Improvements in Key Parameters of Diabetes Management Including Quality of LifeDocument5 pagesInsulin Pump Therapy in Children and Adolescents - Improvements in Key Parameters of Diabetes Management Including Quality of Lifeasdv eqdNo ratings yet

- VHRM - 6098 - Inhaled Insulin - An Overview of A Novel Form of Inhaled Ins - 011310Document12 pagesVHRM - 6098 - Inhaled Insulin - An Overview of A Novel Form of Inhaled Ins - 011310Rubana Reaz TanaNo ratings yet

- J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012 97 16 38Document23 pagesJ Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012 97 16 38rizwan234No ratings yet

- Gracia Ramos2016Document8 pagesGracia Ramos2016Rahmanu ReztaputraNo ratings yet

- Premixed Insulin Analogue Compared With Basal-Plus Regimen For Inpatient Glycemic ControlDocument9 pagesPremixed Insulin Analogue Compared With Basal-Plus Regimen For Inpatient Glycemic ControlAbraham RamonNo ratings yet

- Fully Closed Loop Insulin Delivery in Inpatients RDocument10 pagesFully Closed Loop Insulin Delivery in Inpatients Rmutiara prasastiNo ratings yet

- Glucosa 2012Document6 pagesGlucosa 2012martynbbNo ratings yet

- Pollom 2010Document11 pagesPollom 2010Jeanette LuevanosNo ratings yet

- NONE BDocument11 pagesNONE BPincelito21No ratings yet

- Khowaja2018 Article GlycemicControlInHospitalizedP PDFDocument9 pagesKhowaja2018 Article GlycemicControlInHospitalizedP PDFMade Dedy KusnawanNo ratings yet

- Diabetes Artigo 04Document19 pagesDiabetes Artigo 04Júlio EpifanioNo ratings yet

- Continuous Insulin InfusionDocument6 pagesContinuous Insulin Infusionbobobo22No ratings yet

- Insulin Autoimmune Syndrome Induced by Exogenous Insulin Injection: A Four-Case SeriesDocument6 pagesInsulin Autoimmune Syndrome Induced by Exogenous Insulin Injection: A Four-Case SeriesFeni Nurmia PutriNo ratings yet

- Ratner 2011 Preprandial Vs Postprandial GlulisineDocument7 pagesRatner 2011 Preprandial Vs Postprandial GlulisineKusumaNo ratings yet

- V Diabetic Medicine - 2009 - Smart - Children and Adolescents On Intensive Insulin Therapy Maintain Postprandial GlycaemicDocument7 pagesV Diabetic Medicine - 2009 - Smart - Children and Adolescents On Intensive Insulin Therapy Maintain Postprandial GlycaemicReeds LaurelNo ratings yet

- InsulinaDocument8 pagesInsulinaClaudiu SufleaNo ratings yet

- What Are The Disadvantages of Sliding-Scale Insulin?: BriefreportDocument3 pagesWhat Are The Disadvantages of Sliding-Scale Insulin?: BriefreportT.A.BNo ratings yet

- Closed-Loop Insulin Delivery For Treatment of Type 1 DiabetesDocument9 pagesClosed-Loop Insulin Delivery For Treatment of Type 1 DiabetesPreda ManuelaNo ratings yet

- Original Article: Nancy J. Wei, MD, MMSC David M. Nathan, MD Deborah J. Wexler, MD, MSCDocument8 pagesOriginal Article: Nancy J. Wei, MD, MMSC David M. Nathan, MD Deborah J. Wexler, MD, MSCAnggie AnggriyanaNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 7 - Inpatient Management of Diabetes and HyperglycemiaDocument6 pagesCHAPTER 7 - Inpatient Management of Diabetes and HyperglycemiaenesNo ratings yet

- Https:/zero Sci-Hub Se/5089//boulet2016Document10 pagesHttps:/zero Sci-Hub Se/5089//boulet2016Caroline QueirogaNo ratings yet

- New Technologies and Therapies in The Management of DiabetesDocument8 pagesNew Technologies and Therapies in The Management of DiabetesArhaMozaNo ratings yet

- International Journal Insulin DosingDocument12 pagesInternational Journal Insulin DosingMutia Ramadini91No ratings yet

- Glycaemic Control On Nutritional Support FindingDocument2 pagesGlycaemic Control On Nutritional Support Findingmutiara prasastiNo ratings yet

- Insulin Resistance IcuDocument18 pagesInsulin Resistance IcuLucero GutierrezNo ratings yet

- Diabetes DietDocument8 pagesDiabetes DietkitchaaNo ratings yet

- Co 2019 Controle Glicemico IntDocument8 pagesCo 2019 Controle Glicemico InthauhauNo ratings yet

- Timing of Insulin Injections Adherence and GlycemiDocument12 pagesTiming of Insulin Injections Adherence and GlycemiOlesiaNo ratings yet

- Desantis 2006Document15 pagesDesantis 2006Hoàng ThôngNo ratings yet

- Ketogenic Diet and Type One DMDocument9 pagesKetogenic Diet and Type One DMLara Z. AbuShqairNo ratings yet

- Ajuste Con Dosis PreviasDocument23 pagesAjuste Con Dosis PreviasOscar AlfonsoNo ratings yet

- Pilot Study of A Model-Based Approach To Blood Glucose Control in Very-Low-Birthweight NeonatesDocument9 pagesPilot Study of A Model-Based Approach To Blood Glucose Control in Very-Low-Birthweight NeonatesMoch Rizki DestiantoroNo ratings yet

- Treatment of Patients With Type 1 Diabetes Insulin Pumps or Multiple Injections 2016 Biocybernetics and Biomedical EngineeringDocument8 pagesTreatment of Patients With Type 1 Diabetes Insulin Pumps or Multiple Injections 2016 Biocybernetics and Biomedical EngineeringJose J.No ratings yet

- Burs Lem 2021Document13 pagesBurs Lem 2021ERINSONNo ratings yet

- Original Paper: World Nutrition JournalDocument6 pagesOriginal Paper: World Nutrition JournalSaptawati BardosonoNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Pharmaceutics: Lia Bally, Hood Thabit, Roman HovorkaDocument10 pagesInternational Journal of Pharmaceutics: Lia Bally, Hood Thabit, Roman HovorkaBrasoveanu GheorghitaNo ratings yet

- Goebel Fabbri 2008 Diabetes and Eating DisordersDocument3 pagesGoebel Fabbri 2008 Diabetes and Eating Disordersfilmstudio0510No ratings yet

- Glucose InsulineDocument5 pagesGlucose Insulinesaadshahab622No ratings yet

- Case StudyDocument3 pagesCase StudyAnnie Laiza BacayNo ratings yet

- Management of Hyperglycemia in Critical Care.5Document10 pagesManagement of Hyperglycemia in Critical Care.5nicho927No ratings yet

- Nutrisi Glikemik Kontrol 2Document11 pagesNutrisi Glikemik Kontrol 2Fera Ayu FitriyaniNo ratings yet

- Prevalence, Biochemical and Hematological Study of Diabetic PatientsDocument6 pagesPrevalence, Biochemical and Hematological Study of Diabetic PatientsOpenaccess Research paperNo ratings yet

- Why Is Premixed Insulin The Preferred Insulin? Novel Answers To A Decade-Old QuestionDocument3 pagesWhy Is Premixed Insulin The Preferred Insulin? Novel Answers To A Decade-Old QuestionDanielShenfieldNo ratings yet

- Hyperglycemia After Cardiac Surgery - Hebson2013Document6 pagesHyperglycemia After Cardiac Surgery - Hebson2013Dr XNo ratings yet

- Practice Tips: Insulin Protocols For Hospital Management of DiabetesDocument2 pagesPractice Tips: Insulin Protocols For Hospital Management of DiabetesEen AmaliaNo ratings yet

- Insulina DM2 PDFDocument11 pagesInsulina DM2 PDFGabriel VargasNo ratings yet

- HypoglicemicDocument20 pagesHypoglicemicAndreea CreangaNo ratings yet

- Title of The Research: Diabetes Mellitus By: Abdelrahman Gamal Course Title: Pharmacology Academic Year: Fourth 2019-2020Document11 pagesTitle of The Research: Diabetes Mellitus By: Abdelrahman Gamal Course Title: Pharmacology Academic Year: Fourth 2019-2020LAZKILLERNo ratings yet

- TM 15Document8 pagesTM 15Alfi LafitNo ratings yet

- Medicine: Allopurinol Use and Type 2 Diabetes Incidence Among Patients With GoutDocument7 pagesMedicine: Allopurinol Use and Type 2 Diabetes Incidence Among Patients With GoutGrady CoolNo ratings yet

- Garber 2007Document6 pagesGarber 2007Diana SamuezaNo ratings yet

- PAMW 2014-04 - WrobelDocument7 pagesPAMW 2014-04 - WrobelDiana SamuezaNo ratings yet

- How To Manage Steroid Diabetes in The Patient With CancerDocument5 pagesHow To Manage Steroid Diabetes in The Patient With CancerMade Dedy KusnawanNo ratings yet

- Carter 2020Document6 pagesCarter 2020oanadubNo ratings yet

- Feasibility Study Project Proposal RequirementsDocument2 pagesFeasibility Study Project Proposal RequirementsErick NgosiaNo ratings yet

- Unit3&4 Network TheoramsDocument73 pagesUnit3&4 Network TheoramsBALAKRISHNA PERALANo ratings yet

- Resource Guide For New ChrosDocument23 pagesResource Guide For New Chroslane.a.mcfNo ratings yet

- Full Download PDF of Test Bank For Exploring Marriages and Families, 3rd Edition, Karen Seccombe All ChapterDocument26 pagesFull Download PDF of Test Bank For Exploring Marriages and Families, 3rd Edition, Karen Seccombe All Chapterroosennwosu100% (4)

- What Every Musician Needs To Know About The Body: The Practical Application of Body Mapping To Making Music Bridget JankowskiDocument70 pagesWhat Every Musician Needs To Know About The Body: The Practical Application of Body Mapping To Making Music Bridget Jankowskicmotatmusic100% (6)

- MLD 201aDocument13 pagesMLD 201aChaucer19No ratings yet

- Attach 8 - CPDS Type 2ADocument401 pagesAttach 8 - CPDS Type 2AGlenn Adalia BonitaNo ratings yet

- Sfdunj Jkon PH 1F 3DM Mep 000014Document1 pageSfdunj Jkon PH 1F 3DM Mep 000014Syauqy AlfarakaniNo ratings yet

- Principal 5svbk8Document56 pagesPrincipal 5svbk8badillojdNo ratings yet

- Art AppreciationDocument10 pagesArt AppreciationJasmine EnriquezNo ratings yet

- (1142) Grade XI Admissions 2016-17Document7 pages(1142) Grade XI Admissions 2016-17Naveen ShankarNo ratings yet

- SUN - MOBILITY - PRIVATE - LIMITED - 2022-23 - Financial Statement - XMLDocument109 pagesSUN - MOBILITY - PRIVATE - LIMITED - 2022-23 - Financial Statement - XMLTanishq ChourishiNo ratings yet

- 3rdquarter Week7 Landslide and SinkholeDocument4 pages3rdquarter Week7 Landslide and SinkholeNayeon IeeNo ratings yet

- COT1-3rd HirarkiyaDocument49 pagesCOT1-3rd HirarkiyaRommel LasugasNo ratings yet

- Cyanotype Day 2 LessonDocument3 pagesCyanotype Day 2 Lessonapi-644679449No ratings yet

- Product Demo Feedback FormDocument1 pageProduct Demo Feedback FormVarunSharmaNo ratings yet

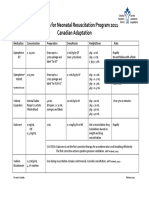

- Medications For Neonatal Resuscitation Program 2011 Canadian AdaptationDocument1 pageMedications For Neonatal Resuscitation Program 2011 Canadian AdaptationrubymayNo ratings yet

- Some, No, Any, EveryDocument2 pagesSome, No, Any, Everyvivadavid100% (1)

- METRIX AUTOCOMP - Company ProfileDocument2 pagesMETRIX AUTOCOMP - Company ProfileVaibhav AggarwalNo ratings yet

- What Is CommunicationDocument4 pagesWhat Is CommunicationsamsimNo ratings yet

- Puzzles: The Question: There Is Only One Correct Answer To This Question. Which Answer Is This? AnsDocument7 pagesPuzzles: The Question: There Is Only One Correct Answer To This Question. Which Answer Is This? AnsSk Tausif ShakeelNo ratings yet

- Nihongo Lesson FL 1Document21 pagesNihongo Lesson FL 1Lee MendozaNo ratings yet

- Essentials of Educational Psychology Big Ideas To Guide Effective Teaching 6Th Edition Jeanne Ellis Ormrod Full ChapterDocument67 pagesEssentials of Educational Psychology Big Ideas To Guide Effective Teaching 6Th Edition Jeanne Ellis Ormrod Full Chaptermarion.wade943No ratings yet

- Submarine Cable Installation ContractorsDocument19 pagesSubmarine Cable Installation Contractorswiji_thukulNo ratings yet

- Chapter 7 - Non Verbal CommunicationDocument7 pagesChapter 7 - Non Verbal CommunicationCarolyn NacesNo ratings yet

- Practice Quiz - Managing CollaborationDocument2 pagesPractice Quiz - Managing CollaborationMohamed RahalNo ratings yet

- Ruskin Bonds "THE KITE MAKER"Document14 pagesRuskin Bonds "THE KITE MAKER"Dhruti Galgali38% (8)

Weight-Based, Insulin Dose - Related Hypoglycemia in Hospitalized Patients With Diabetes

Weight-Based, Insulin Dose - Related Hypoglycemia in Hospitalized Patients With Diabetes

Uploaded by

Puri PuriOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Weight-Based, Insulin Dose - Related Hypoglycemia in Hospitalized Patients With Diabetes

Weight-Based, Insulin Dose - Related Hypoglycemia in Hospitalized Patients With Diabetes

Uploaded by

Puri PuriCopyright:

Available Formats

Clinical Care/Education/Nutrition/Psychosocial Research

O R I G I N A L A R T I C L E

Weight-Based, Insulin Dose–Related

Hypoglycemia in Hospitalized Patients

With Diabetes

1

DANIEL J. RUBIN, MD, MSC GHEORGHE DOROS, PHD3 of hypoglycemia with higher weight-

DENIS RYBIN, PHD2 MARIE E. MCDONNELL, MD4 based doses has not been established. A

better understanding of the relationship

between insulin dose and hypoglycemia

OBJECTIVE—To determine the association of weight-based insulin dose with hypoglycemia may facilitate more effective dosing, thus

in noncritically ill inpatients with diabetes. reducing the risk of hypoglycemia and

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS—We performed a retrospective, case-control hyperglycemia.

study of 1,990 diabetic patients admitted to hospital wards. Patients with glucose levels ,70 We performed a retrospective, case-

mg/dL (case subjects) were matched one to one with nonhypoglycemic control subjects on the control study of patients with diabetes

basis of the hospital day of hypoglycemia, age, sex, and BMI. admitted to general hospital wards to

investigate the relationship between insulin

RESULTS—Relative to 24-h insulin doses ,0.2 units/kg, the unadjusted odds of hypoglyce- dose and hypoglycemia. It was hypothe-

mia increased with increasing insulin dose. Adjusted for insulin type, sliding-scale insulin use, sized that higher weight-based insulin

and albumin, creatinine, and hematocrit levels, the higher odds of hypoglycemia with increasing

insulin doses remained (0.6–0.8 units/kg: odds ratio 2.10 [95% CI 1.08–4.09], P = 0.028; .0.8

doses are associated with a greater risk of

units/kg: 2.95 [1.54–5.65], P = 0.001). The adjusted odds of hypoglycemia were not greater in hypoglycemia. Furthermore, we predicted

patients who received 0.2–0.4 units/kg (1.08 [0.64–1.81], P = 0.78) or 0.4–0.6 units/kg (1.60 that the association of insulin dose with

[0.90–2.86], P = 0.11). Although the relationship between insulin dose and hypoglycemia did hypoglycemia varies by type of insulin

not vary by insulin type, patients who received NPH trended toward greater odds of hypogly- regimen, with glargine-based regimens

cemia compared with those given other insulins. being associated with less hypoglycemia

than NPH-based regimens.

CONCLUSIONS—Higher weight-based insulin doses are associated with greater odds of hypo-

glycemia independent of insulin type. However, 0.6 units/kg seems to be a threshold below which the

odds of hypoglycemia are relatively low. These findings may help clinicians use insulin more safely. RESEARCH DESIGN AND

METHODS

Diabetes Care 34:1723–1728, 2011

Study sample

T

reatment with insulin in hospitalized insulin therapy for hospital-ward patients Abstracting data from electronic medical

patients is a well-recognized risk (4–6), in which one approach to deter- records, we retrospectively selected a

factor for hypoglycemia. Although mining insulin dose is based on weight sample of adult inpatients who received

this clearly has been demonstrated in (i.e., total daily units per kilogram of insulin at Boston Medical Center, most

critically ill patients treated with contin- body weight). The initial daily insulin of whom had a diagnosis of diabetes,

uous intravenous insulin (1), evidence doses of basal-bolus protocols vary admitted between 1 July 2005 and 31

regarding subcutaneous insulin in non– widely, from 0.3 to 1.5 units/kg (5,7– December 2009. Diabetes was defined by

critical-care settings is lacking. Physicians 10). Rates of hypoglycemia in random- any one of the following: 1) administra-

may underdose insulin in fear of hypogly- ized trials using 0.4–0.5 units/kg/day of tion of an oral antidiabetes medication

cemia because there is uncertainty about insulin range from 3 to 33% of subjects (metformin, a thiazolidinedione, or a sul-

the dose-response relationship between (9,11). Furthermore, these studies ex- fonylurea) during hospitalization; 2) a di-

insulin and hypoglycemia in noncritically cluded patients with known risk factors abetes ICD-9 code of 250.xx; or 3) an A1C

ill inpatients with diabetes (2,3). for hypoglycemia, such as renal impair- .6.5%. Patients were excluded if they

Current guidelines on inpatient di- ment. Despite the use of relatively high were aged ,18 years, were admitted to

abetes management call for basal-bolus insulin doses in clinical practice, the risk an intensive care unit, had a primary di-

agnosis of hypoglycemia, had hypogly-

c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c cemia (any blood glucose ,70 mg/dL)

From the 1Section of Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Metabolism, Temple University School of Medicine, within 24 h of admission, or had no

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; the 2Data Coordinating Center, Boston University School of Public Health, point-of-care (POC) capillary glucose val-

Boston, Massachusetts; the 3Department of Biostatistics, Boston University School of Public Health, ues. The sample was restricted to only the

Boston, Massachusetts; and the 4Section of Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Nutrition, Boston University

School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts.

first admission per patient, and data sub-

Corresponding author: Daniel J. Rubin, djrubin@temple.edu. sequent to the first hypoglycemic event

Received 26 December 2010 and accepted 24 May 2011. after 24 h were excluded. Only POC

DOI: 10.2337/dc10-2434 values were used to measure glucose

This article contains Supplementary Data online at http://care.diabetesjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10. because of variability among different

2337/dc10-2434/-/DC1.

© 2011 by the American Diabetes Association. Readers may use this article as long as the work is properly glucose assays.

cited, the use is educational and not for profit, and the work is not altered. See http://creativecommons.org/ Case subjects were defined by a POC

licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ for details. glucose ,70 mg/dL after the first 24 h of

care.diabetesjournals.org DIABETES CARE, VOLUME 34, AUGUST 2011 1723

Inpatient insulin and hypoglycemia

admission. The time period examined for as the first POC glucose value within 24 h Approximately 50% of the patients were

each case was 24 h prior to the first hypo- of admission. given metformin, 33% were given a sulfo-

glycemic event in order to include all rel- nylurea, and 13% were given a thiazolidi-

evant doses of insulin. Control subjects, Statistical analysis nedione. The sample was racially diverse:

defined by a POC glucose $70 mg/dL, Summaries of categorical variables in- 40.6% were African American, 34.1% were

were matched one to one on the basis of cluded counts and percentages, whereas white, 13.9% were Hispanic, and 11.4%

the hospital day of hypoglycemia, age for continuous variables means and SDs were of other race/ethnicity. The mean

(18–30, 31–64, or 65–80 years), sex, were used. Comparability between the A1C was 8.1 6 2.2%, and mean serum

and BMI (,18.5, 18.5–25, 25–30, or case and control groups for categorical creatinine was 1.5 6 1.7 mg/dL. Length

.30 kg/m2). Matching on hospital day variables was determined using the x2 test of stay averaged 7.6 6 7.0 days. Of the

of hypoglycemia provided a control time for categorical variables and the two- 1,990-patient sample, 1,418 (71.3%)

frame as well as controlled for variation in sample t test for continuous variables. g were not on insulin as an outpatient.

clinical status during hospitalization. Regression was used for length of stay Hypoglycemic patients were more

because this continuous, positive variable likely to be given glargine or NPH and

Variable definitions was not normally distributed. less likely to be given only SSI or no in-

The exposure was defined as the total Conditional logistic regression was sulin than control subjects (P , 0.001).

insulin dose per body weight (units/kg) used to examine the unadjusted and the SSI plus scheduled insulin was more

over the 24-h study period. Insulin doses adjusted association of insulin dose with common, whereas SSI without scheduled

were stratified into nonoverlapping ranges, hypoglycemia. The initial adjusted model insulin was less common, among case

as follows: 0, ,0.2, 0.2–0.4, 0.4–0.6, included all variables that were associated subjects than control subjects (P ,

0.6–0.8, and $0.8 units/kg. The exposure with hypoglycemia, as well an interaction 0.001). Hypoglycemic patients had a

was grouped by insulin regimen type as term for dose by regimen to assess effect lower albumin and hematocrit and higher

follows: 1) glargine plus any other insulin, modification by insulin regimen type on creatinine and length of stay than nonhy-

2) NPH plus any other insulin, 3) lispro the relationship between insulin dose and poglycemic patients (P , 0.001 for each

and/or regular insulin only, and 4) no in- hypoglycemia. We then performed back- comparison). Case subjects also had higher

sulin. For 11 patients who received both ward selection with the a level to keep comorbidity index scores than control

glargine and NPH in 1 day, group assign- variables in the model set at 0.2 (13). subjects (P , 0.001). There was no differ-

ment was on the basis of whichever insulin A P value , 0.05 was considered statisti- ence in mean A1C (8.0 6 2.1 vs. 8.1 6

dose was greater. For two patients who cally significant. All analyses were per- 2.3%, P = 0.44) or admission glucose

received the same total 24-h dose of glar- formed using SAS (version 9.2; SAS (199.8 6 109.5 vs. 193.6 6 96.9 mg/dL,

gine and NPH, group assignment was on Institute, Cary, NC). The Boston Univer- P = 0.20) between case and control sub-

the basis of the insulin given closest to the sity Medical Center Institutional Review jects. Higher insulin doses were associated

hypoglycemic event. Guidelines for insu- Board approved the protocol. with progressively higher blood glucose

lin dosing at Boston Medical Center have levels (Supplementary Table 2). Within

been published (10). RESULTS—Of 6,376 eligible patients each dose range, the mean glucose levels

The following known predictors of abstracted from hospital records, 1,012 of case subjects were lower than the mean

hypoglycemia and potential confounders (15.8%) had hypoglycemia. After match- glucose levels of control subjects.

were examined: weight, race, serum cre- ing, 995 case subjects (98.3%) and 995 Relative to insulin doses ,0.2 units/

atinine, albumin, liver function (aspartate nonhypoglycemic control subjects re- kg, the unadjusted odds of hypoglycemia

aminotransferase and alanine amino- mained (Supplementary Table 1). Com- increased with increasing insulin dose

transferase), A1C, white blood cell count, pared with 4,386 unmatched patients, the (Table 2). Adjusted for insulin regimen,

hematocrit, use of sliding-scale insulin matched control sample was older (aged SSI use, and albumin, creatinine, and he-

(SSI), fasting, length of stay, service (med- 63.3 vs. 60.6 years, P , 0.001), had lower matocrit levels, the higher odds of hypo-

ical or surgical), and disease severity de- weights (86.1 vs. 91.4 kg, P , 0.001), glycemia with increasing insulin doses

fined by the Charlson Comorbidity Index were less obese (BMI 31.2 vs. 33 kg/m2, remained (Table 3 and Fig. 1). Patients

(12). A higher comorbidity index repre- P , 0.001), had a higher proportion of who received insulin doses of $0.6

sents a greater burden of comorbid dis- African Americans (39.4 vs. 36.6%, P = units/kg were at increased odds of hypo-

ease. Use of SSI was categorized as only 0.04 for race), and a had lower proportion glycemia. In contrast, the adjusted odds

SSI, no SSI, or SSI plus scheduled insulin. of Hispanics (12.7 vs. 16.1%). The of hypoglycemia were not higher in pa-

Data were collected during hospitaliza- matched and unmatched control subjects tients who received 0.2–0.6 units/kg. The

tion, except for missing values that were were similar in terms of sex distribution association of insulin dose with hypogly-

substituted by the closest value up to and mean A1C. cemia did not vary by regimen type, as

3 months prior to admission. BMI values The median time from admission to indicated by a statistically nonsignificant

,10 or .100 kg/m 2 , weight ,20 or the first hypoglycemic event in case sub- interaction term in the multivariate model

.400 kg, and height ,100 or .300 cm jects was 2.7 days (range 1.0–33.7). Dur- (P = 0.524).

were considered erroneous and were de- ing the index 24-h period, glargine was In addition to insulin dose, there were

leted. No height was available for 195 pa- the most frequently administered insulin several significant predictors of hypogly-

tients (9.8%). For these individuals, the (31.7%), followed by short-acting insulin cemia, including creatinine and hematocrit.

average height of the sample for each sex (28.4%), no insulin (24.0%), and NPH in- The odds of hypoglycemia were threefold

was imputed (174.2 6 9.6 cm for male sulin (15.9%) (Table 1). SSI only was less greater among those who did not receive

subjects and 160.8 6 8.5 cm for female common than SSI plus scheduled insulin SSI relative to those who did. Patients who

subjects). Admission glucose was defined and no SSI at all (25.3, 37.0, and 37.7%). received SSI plus scheduled insulin or SSI

1724 DIABETES CARE, VOLUME 34, AUGUST 2011 care.diabetesjournals.org

Rubin and Associates

Table 1—Sample characteristics of unmatched factors by case status

All patients Case subjects Control subjects P*

n 1,990 995 995

Insulin regimen

Glargine 630 (31.7) 38.1 25.2 ,0.001

NPH 316 (15.9) 22.4 9.3

Lispro and/or regular only† 566 (28.4) 19.5 37.4

None 478 (24.0) 20.0 28.0

Basal-to-total insulin dose ratio

0.00 566 (28.4) 19.5 37.4 ,0.001

0.01–0.39 99 (5.0) 4.5 5.4

0.40–0.59 267 (13.4) 16.3 10.6

0.60–1.00 580 (29.1) 39.7 18.6

No insulin 478 (24.0) 20.0 28.0

SSI use

SSI only 503 (25.3) 16.6 34.0 ,0.001

SSI plus scheduled insulin 737 (37.0) 42.9 31.2

No SSI 750 (37.7) 40.5 34.9

Medication use in hospital

Metformin 417 (54.3) 49.9 58.8 0.086

Sulfonylureas 254 (32.8) 35.7 30.3

Thiazolidinediones 97 (12.6) 14.4 10.8

Glucocorticoids 210 (10.6) 10.2 11.0 0.558

Weight (kg) 85.6 6 27.0 85.2 6 27.7 86.1 6 26.2 0.301

Race

African American 799 (40.6) 41.8 39.4 0.167

White 671 (34.1) 32.2 36.0

Hispanic 274 (13.90 15.1 12.7

Other 225 (11.4) 11.0 11.9

Laboratory studies

A1C (%) 8.1 6 2.2 8.0 6 2.1 8.1 6 2.3 0.438

Albumin (g/dL) 3.5 6 0.6 3.4 6 0.6 3.5 6 0.5 ,0.001

Alanine aminotransferase (units/L) 34.6 6 99.3 34.6 6 101.2 34.5 6 97.4 0.867

Aspartate aminotransferase (units/L) 41.3 6 219.9 40.1 6 172.9 42.6 6 260.7 0.937

Creatinine (mg/dL) 1.5 6 1.7 1.7 6 2.0 1.3 6 1.2 ,0.001

Hematocrit (%) 32.8 6 5.2 32.1 6 5.0 33.6 6 5.3 ,0.001

WBC (k/UL) 8.4 6 4.1 8.4 6 4.4 8.5 6 3.7 0.553

Fasting within prior 24 h‡ 403 (20.3) 50.6 49.4 0.774

Primary service‡

Medicine 1,404 73.5 68.1 0.008

Surgery 580 26.5 31.9

Comorbidity index

0 107 (5.40) 4.6 6.1 ,0.001

1–2 803 (40.4) 36.4 44.3

3–4 682 (34.3) 36.4 32.2

5–6 282 (14.2) 17.3 11.1

.6 116 (5.8) 5.3 6.3

Length of stay (days) 7.6 6 7.0 8.1 6 8.2 7.1 6 5.5 ,0.001

Data are n (%), percentages, or means 6 SD. *P values for categorical variables were generated by x2 tests. P values for continuous variables were generated by t tests.

†Hypoglycemia prevalence among patients who received lispro was similar to that among patients given regular insulin (31.8 vs. 36.1%). ‡Excludes six patients with

missing values.

alone had higher blood glucose levels To investigate whether the risk of in the odds of hypoglycemia between

than patients who did not receive SSI hypoglycemia depends on the ratio of basal ratios .0.6 or 0 and 0.4–0.6. Fur-

(203 6 64, 185 6 52, and 128 6 33 basal insulin (NPH or glargine) relative thermore, there was no interaction of basal

mg/dL, P , 0.001). There was a trend to- to the total daily dose, a post hoc anal- ratio with the insulin dose–hypoglycemia

ward higher odds of hypoglycemia among ysis revealed that basal ratios ,0.4 confer relationship.

patients who received NPH compared lower odds of hypoglycemia than 0.4–0.6 Hypoglycemia was not more com-

with patients given glargine or short-acting (odds ratio 0.50 [95% CI 0.25–0.97], P = mon among patients given insulin with an

insulin. 0.040). In contrast, there was no difference oral diabetes medication compared with

care.diabetesjournals.org DIABETES CARE, VOLUME 34, AUGUST 2011 1725

Inpatient insulin and hypoglycemia

Table 2—Distribution of insulin dose by case status threshold, patients given SSI are hyper-

glycemic by design. Patients who did not

All patients Case subjects Control subjects P* receive SSI may have been given excessive

scheduled insulin, resulting in more fre-

n 1,990 995 995 quent hypoglycemia. Together, these data

Insulin dose (units/kg) suggest that the insulin program with the

0 478 (24.0) 20.0 28.0 ,0.001 lowest risk of hypoglycemia consists of

,0.2 595 (29.9) 22.2 37.6 scheduled insulin plus SSI at total daily

0.2–0.4 285 (14.4) 15.0 13.7 doses ,0.6 units/kg.

0.4–0.6 263 (13.2) 16.5 9.9 Our findings are broadly consistent

0.6–0.8 161 (8.1) 11.4 4.8 with other studies of insulin use in non–

$0.8 208 (10.5) 15.0 5.9 intensive care unit inpatients that show

Data are n (%) or percentages. *P value by x2 test. that insulin is a risk factor for hypoglyce-

mia (14,15). These studies, however, did

those on insulin alone (49.4 vs. 54.6%, A1C .6.5%. A sensitivity analysis ex- not examine how the risk of hypoglyce-

P = 0.13). However, of the 201 patients cluding these patients yielded similar mia varies by insulin dose or type. The

who did not receive insulin but did re- results. lack of a clear difference in the odds of

ceive an oral agent, sulfonylureas were hypoglycemia between glargine and NPH

more common among hypoglycemic pa- is similar to data from a randomized trial

tients than in control subjects (27.4 vs. CONCLUSIONS—This retrospective, comparing weight-based analog insulins

16.4%, P , 0.001). Patients who received matched, case-control study of 1,990 with NPH and regular insulins that found

only SSI were more likely to be given an hospital-ward patients with diagnosed no difference in hypoglycemia rates be-

oral agent than those on SSI plus sched- or probable diabetes shows that higher tween the treatment groups (11). Also con-

uled insulin and those not given SSI weight-based insulin doses are associated sistent with other studies are our findings

(54.5, 28.1, and 38.3%, P , 0.001). with greater odds of hypoglycemia, in- that high creatinine and low hematocrit

Although hypoglycemia was propor- dependent of the types of insulin used. levels are independently associated with

tionately more common on medical serv- Adjusted for insulin regimen, SSI use, and hypoglycemia (16,17).

ices than on surgical services (Table 1, P = albumin, creatinine, and hematocrit levels, The frequent use of oral agents was

0.008), this variable was not significant in patients given at least 0.8 units/kg within surprising given that our medication

the multivariate model. There was no dif- a 24-h period are at threefold-higher odds guideline for hospitalized patients with

ference in mean blood glucose in medical of hypoglycemia than patients who re- diabetes encourages the discontinuation

versus surgical patients (173 6 62 vs. ceive ,0.2 units/kg. However, 0.6 units/kg of oral agents. However, we support the

168 6 59, P = 0.12). However, medical seems to be a threshold below which the judicious use of oral diabetes medications

patients received more insulin than surgi- odds of hypoglycemia are relatively low. In in patients who are eating regularly, who

cal patients (0.35 6 0.88 vs. 0.26 6 0.38 addition, patients who do not receive SSI are no longer acutely ill, and/or who

units/kg, P = 0.013). In addition, SSI only are at threefold-greater odds of hypoglyce- preparing for discharge, consistent with

was less common among medical patients mia than patients who receive SSI with some expert opinions (1,18). Our data

(20.9 vs. 36.0%, P , 0.001). The sample or without scheduled insulin. Because provide evidence for the safety of this ap-

included 77 patients (3.9%) without a SSI typically is administered in response proach in terms of hypoglycemia.

diagnosis of diabetes who had an inpatient to a glucose value above a predetermined A number of limitations must be

acknowledged. Generalizability is limited

by the inclusion of only one medical

Table 3—Predictors of hypoglycemia in the multivariate conditional logistic regression model center. Also, bias cannot be completely

accounted for by matching and multivar-

Odds ratio (95% CI) P iate analysis of retrospective data. The use

of POC glucose values at the exclusion

Insulin dose 0.005 of serum glucose values may under-

0.2–0.4 vs. ,0.2 1.08 (0.64–1.82) 0.777 estimate the occurrence of hypoglycemia.

0.4–0.6 vs. ,0.2 1.60 (0.90–2.86) 0.109 This effect, however, is likely to be small

0.6–0.8 vs. ,0.2 2.10 (1.08–4.09) 0.028 because almost all inpatients with diabe-

.0.8 vs. ,0.2 2.95 (1.54–5.65) 0.001 tes are ordered POC testing four times

Insulin regimen 0.062 daily, and a POC glucose is more likely to

Glargine vs. lispro/regular 1.58 (0.67–3.74) 0.297 be checked on a patient with hypoglyce-

NPH vs. lispro/regular 2.38 (0.97–5.87) 0.059 mic symptoms than a serum glucose.

NPH vs. glargine 1.51 (1.00– 2.27) 0.050 Another limitation is that a case-control

SSI ,0.001 design precludes the calculation of hy-

No SSI vs. SSI only 3.04 (1.23–7.51) 0.016 poglycemia rates; however, the odds ratio

SSI plus scheduled insulin vs. SSI only 0.83 (0.36–1.88) 0.648 provides a reasonable estimate of relative

No SSI vs. SSI plus scheduled insulin 3.68 (2.25–6.03) ,0.001 risk. An additional limitation is our in-

Albumin level 0.80 (0.60–1.08) 0.143 ability to classify the sample by diabetes

Creatinine level 1.14 (1.02–1.28) 0.018 type because of unavailable data. How-

Hematocrit level 0.96 (0.93–0.99) 0.013 ever, at least 90% of the sample is estimated

1726 DIABETES CARE, VOLUME 34, AUGUST 2011 care.diabetesjournals.org

Rubin and Associates

the effect of basal ratio in scheduled in-

sulin doses across heterogeneous in-

patient populations. Another question is

whether higher insulin doses cause hypo-

glycemia more quickly than lower insulin

doses.

In conclusion, we found that higher

weight-based insulin doses are associated

with greater odds of hypoglycemia, and

this association does not differ by the type

of insulin used. Insulin doses ,0.6 units/

kg confer a lower odds of hypoglycemia,

whereas doses .0.6 units/kg are associ-

ated with higher odds of hypoglycemia.

These data imply that 0.4–0.6 units/kg

may be the optimal dose range. Given

that insulin is recommended for most hos-

pitalized patients with diabetes (4), and

hypoglycemia is associated with increased

length of stay and mortality (15), strategies

to reduce hypoglycemia are of critical im-

portance. Our findings provide additional

information to help clinicians dose insulin

more safely for inpatients with diabetes.

Acknowledgments—No potential conflicts of

interest relevant to this article were reported.

D.J.R. designed the study, researched data,

and wrote the manuscript. D.R. designed the

study, researched data, and reviewed and

edited the manuscript. G.D. and M.E.M. de-

signed the study and reviewed and edited the

manuscript.

Figure 1—Multivariate-adjusted odds of hypoglycemia at different insulin doses in 995 case

Parts of this study were presented in abstract

subjects vs. 995 matched control subjects. Error bars represent 95% CIs. OR, odds ratio.

form at the 93rd Annual Meeting of The Endo-

*P , 0.05 by conditional logistic regression.

crine Society, Boston, Massachusetts, 4–7 June

2011.

The authors thank Linda Rosen of the Boston

to have type 2 diabetes, in keeping with control subjects had similar admission Medical Center for her help with data collection.

national estimates (19). Finally, the focus of glucose values and because we adjusted

our study was hypoglycemia, and we did for numerous potential confounders, it is

not examine the association of insulin dose likely that we have isolated the effect of References

with hyperglycemia. inpatient insulin dose on hypoglycemia. 1. Inzucchi SE. Clinical practice: management

Although lower-dose insulin regimens Matching case subjects on the basis of of hyperglycemia in the hospital setting.

may confer a lower risk of hypoglycemia, hospital day, age, sex, and BMI created a N Engl J Med 2006;355:1903–1911

they may be associated with a higher risk of comparable control group. Furthermore, 2. Trujillo JM, Barsky EE, Greenwood BC, et al.

hyperglycemia. The weight-based insulin no published study has investigated the Improving glycemic control in medical

inpatients: a pilot study. J Hosp Med 2008;

dose that minimizes both hypoglycemia association of weight-based insulin with 3:55–63

and hyperglycemia remains unclear. These inpatient hypoglycemia across a range of 3. Matheny ME, Shubina M, Kimmel ZM,

data, however, suggest that 0.4–0.6 units/kg, doses and insulin types. Pendergrass ML, Turchin A. Treatment

a dose range tested in randomized con- Our research leads to additional ques- intensification and blood glucose control

trolled trials and recommended by the tions. One is whether the risk of hypo- among hospitalized diabetic patients. J Gen

American Diabetes Association (5,9,11), glycemia depends on the ratio of basal Intern Med 2008;23:184–189

may be the highest dose at which the risk insulin relative to the total daily dose, 4. Moghissi ES, Korytkowski MT, Dinardo

of hypoglycemia remains low. To deter- which is an important component of M, et al. American Association of Clinical

mine a starting dose of insulin within this insulin protocols (9–11). Post hoc analy- Endocrinologists and American Diabetes

range for a specific patient, clinicians must sis of our data revealed that basal ratios Association consensus statement on in-

patient glycemic control. Diabetes Care

balance the presence of hypoglycemia ,0.4 confer a lower odds of hypoglyce- 2009;32:1119–1131

risk factors with the benefits of achieving mia than basal ratios of 0.4–0.6. This may 5. Clement S, Braithwaite SS, Magee MF, et al.;

glycemic control. reflect a higher proportion of patients American Diabetes Association Diabetes in

Despite these limitations, strengths who received SSI, who are by definition Hospitals Writing Committee. Management

of our study include a large sample size hyperglycemic as discussed above. Pro- of diabetes and hyperglycemia in hospitals.

spanning 4.5 years. Because the case and spective studies are necessary to determine Diabetes Care 2004;27:553–591

care.diabetesjournals.org DIABETES CARE, VOLUME 34, AUGUST 2011 1727

Inpatient insulin and hypoglycemia

6. King AB, Armstrong DU. Basal bolus of an academic hospital. Endocr Pract ML. Hypoglycemia and clinical outcomes

dosing: a clinical experience. Curr Dia- 2010;16:512–521 in patients with diabetes hospitalized in

betes Rev 2005;1:215–220 11. Umpierrez GE, Hor T, Smiley D, et al. the general ward. Diabetes Care 2009;32:

7. Chen HJ, Steinke DT, Karounos DG, Lane Comparison of inpatient insulin regi- 1153–1157

MT, Matson AW. Intensive insulin pro- mens with detemir plus aspart versus 16. Kosiborod M, Inzucchi SE, Goyal A, et al.

tocol implementation and outcomes in neutral protamine hagedorn plus regular Relationship between spontaneous and

the medical and surgical wards at a Vet- in medical patients with type 2 diabetes. iatrogenic hypoglycemia and mortality in

erans Affairs Medical Center. Ann Phar- J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009;94:564–569 patients hospitalized with acute myo-

macother 2010;44:249–256 12. D’Hoore W, Bouckaert A, Tilquin C. cardial infarction. JAMA 2009;301:1556–

8. Maynard G, Lee J, Phillips G, Fink E, Practical considerations on the use of the 1564

Renvall M. Improved inpatient use of basal Charlson comorbidity index with ad- 17. Kagansky N, Levy S, Rimon E, et al. Hy-

insulin, reduced hypoglycemia, and im- ministrative data bases. J Clin Epidemiol poglycemia as a predictor of mortality in

proved glycemic control: effect of struc- 1996;49:1429–1433 hospitalized elderly patients. Arch Intern

tured subcutaneous insulin orders and an 13. Budtz-Jørgensen E, Keiding N, Grandjean P, Med 2003;163:1825–1829

insulin management algorithm. J Hosp Med Weihe P. Confounder selection in environ- 18. Korytkowski MT. Treatment options for

2009;4:3–15 mental epidemiology: assessment of health safely achieving glycemic targets in the

9. Umpierrez GE, Smiley D, Zisman A, effects of prenatal mercury exposure. Ann hospital. ACP Hospitalist, 2009;(Suppl.)

et al. Randomized study of basal-bolus Epidemiol 2007;17:27–35 Chapter 3:15–23

insulin therapy in the inpatient man- 14. Wexler DJ, Meigs JB, Cagliero E, Nathan 19. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

agement of patients with type 2 diabetes DM, Grant RW. Prevalence of hyper- National Diabetes Fact Sheet: General In-

(RABBIT 2 trial). Diabetes Care 2007;30: and hypoglycemia among inpatients with formation and National Estimates on Dia-

2181–2186 diabetes: a national survey of 44 U.S. hos- betes in the United States, 2007. Atlanta,

10. Pietras SM, Hanrahan P, Arnold LM, pitals. Diabetes Care 2007;30:367–369 GA, U.S. Department of Health and Human

Sternthal E, McDonnell ME. State-of-the- 15. Turchin A, Matheny ME, Shubina M, Services, Centers for Disease Control and

art inpatient diabetes care: the evolution Scanlon JV, Greenwood B, Pendergrass Prevention, 2008

1728 DIABETES CARE, VOLUME 34, AUGUST 2011 care.diabetesjournals.org

You might also like

- Cambridge Research ProposalDocument3 pagesCambridge Research ProposalRocky Balbowa100% (1)

- Stuxnet and Its Hidden Lessons On The Ethics of CyberweaponsDocument9 pagesStuxnet and Its Hidden Lessons On The Ethics of CyberweaponsprofcameloNo ratings yet

- Insulin Therapy For Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus.Document11 pagesInsulin Therapy For Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus.Clarissa CozziNo ratings yet

- Practical Insulin: A Handbook for Prescribing ProvidersFrom EverandPractical Insulin: A Handbook for Prescribing ProvidersRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- ReligionsDocument4 pagesReligionsPia Flores67% (3)

- Weight-Based, Insulin Dose - Related Hypoglycemia in Hospitalized Patients With DiabetesDocument6 pagesWeight-Based, Insulin Dose - Related Hypoglycemia in Hospitalized Patients With DiabetesPuri PuriNo ratings yet

- Insulin Analogs Versus Human Insulin in The Treatment of Patients With Diabetic KetoacidosisDocument6 pagesInsulin Analogs Versus Human Insulin in The Treatment of Patients With Diabetic KetoacidosisrosieveliaNo ratings yet

- Indikasi Insulin InfusionDocument7 pagesIndikasi Insulin InfusionnikeNo ratings yet

- Marvin Et Al 2016 Minimization of Hypoglycemia As An Adverse Event During Insulin Infusion Further Refinement of TheDocument7 pagesMarvin Et Al 2016 Minimization of Hypoglycemia As An Adverse Event During Insulin Infusion Further Refinement of TheChanukya GvNo ratings yet

- Insulin Pump Therapy in Children and Adolescents - Improvements in Key Parameters of Diabetes Management Including Quality of LifeDocument5 pagesInsulin Pump Therapy in Children and Adolescents - Improvements in Key Parameters of Diabetes Management Including Quality of Lifeasdv eqdNo ratings yet

- VHRM - 6098 - Inhaled Insulin - An Overview of A Novel Form of Inhaled Ins - 011310Document12 pagesVHRM - 6098 - Inhaled Insulin - An Overview of A Novel Form of Inhaled Ins - 011310Rubana Reaz TanaNo ratings yet

- J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012 97 16 38Document23 pagesJ Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012 97 16 38rizwan234No ratings yet

- Gracia Ramos2016Document8 pagesGracia Ramos2016Rahmanu ReztaputraNo ratings yet

- Premixed Insulin Analogue Compared With Basal-Plus Regimen For Inpatient Glycemic ControlDocument9 pagesPremixed Insulin Analogue Compared With Basal-Plus Regimen For Inpatient Glycemic ControlAbraham RamonNo ratings yet

- Fully Closed Loop Insulin Delivery in Inpatients RDocument10 pagesFully Closed Loop Insulin Delivery in Inpatients Rmutiara prasastiNo ratings yet

- Glucosa 2012Document6 pagesGlucosa 2012martynbbNo ratings yet

- Pollom 2010Document11 pagesPollom 2010Jeanette LuevanosNo ratings yet

- NONE BDocument11 pagesNONE BPincelito21No ratings yet

- Khowaja2018 Article GlycemicControlInHospitalizedP PDFDocument9 pagesKhowaja2018 Article GlycemicControlInHospitalizedP PDFMade Dedy KusnawanNo ratings yet

- Diabetes Artigo 04Document19 pagesDiabetes Artigo 04Júlio EpifanioNo ratings yet

- Continuous Insulin InfusionDocument6 pagesContinuous Insulin Infusionbobobo22No ratings yet

- Insulin Autoimmune Syndrome Induced by Exogenous Insulin Injection: A Four-Case SeriesDocument6 pagesInsulin Autoimmune Syndrome Induced by Exogenous Insulin Injection: A Four-Case SeriesFeni Nurmia PutriNo ratings yet

- Ratner 2011 Preprandial Vs Postprandial GlulisineDocument7 pagesRatner 2011 Preprandial Vs Postprandial GlulisineKusumaNo ratings yet

- V Diabetic Medicine - 2009 - Smart - Children and Adolescents On Intensive Insulin Therapy Maintain Postprandial GlycaemicDocument7 pagesV Diabetic Medicine - 2009 - Smart - Children and Adolescents On Intensive Insulin Therapy Maintain Postprandial GlycaemicReeds LaurelNo ratings yet

- InsulinaDocument8 pagesInsulinaClaudiu SufleaNo ratings yet

- What Are The Disadvantages of Sliding-Scale Insulin?: BriefreportDocument3 pagesWhat Are The Disadvantages of Sliding-Scale Insulin?: BriefreportT.A.BNo ratings yet

- Closed-Loop Insulin Delivery For Treatment of Type 1 DiabetesDocument9 pagesClosed-Loop Insulin Delivery For Treatment of Type 1 DiabetesPreda ManuelaNo ratings yet

- Original Article: Nancy J. Wei, MD, MMSC David M. Nathan, MD Deborah J. Wexler, MD, MSCDocument8 pagesOriginal Article: Nancy J. Wei, MD, MMSC David M. Nathan, MD Deborah J. Wexler, MD, MSCAnggie AnggriyanaNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 7 - Inpatient Management of Diabetes and HyperglycemiaDocument6 pagesCHAPTER 7 - Inpatient Management of Diabetes and HyperglycemiaenesNo ratings yet

- Https:/zero Sci-Hub Se/5089//boulet2016Document10 pagesHttps:/zero Sci-Hub Se/5089//boulet2016Caroline QueirogaNo ratings yet

- New Technologies and Therapies in The Management of DiabetesDocument8 pagesNew Technologies and Therapies in The Management of DiabetesArhaMozaNo ratings yet

- International Journal Insulin DosingDocument12 pagesInternational Journal Insulin DosingMutia Ramadini91No ratings yet

- Glycaemic Control On Nutritional Support FindingDocument2 pagesGlycaemic Control On Nutritional Support Findingmutiara prasastiNo ratings yet

- Insulin Resistance IcuDocument18 pagesInsulin Resistance IcuLucero GutierrezNo ratings yet

- Diabetes DietDocument8 pagesDiabetes DietkitchaaNo ratings yet

- Co 2019 Controle Glicemico IntDocument8 pagesCo 2019 Controle Glicemico InthauhauNo ratings yet

- Timing of Insulin Injections Adherence and GlycemiDocument12 pagesTiming of Insulin Injections Adherence and GlycemiOlesiaNo ratings yet

- Desantis 2006Document15 pagesDesantis 2006Hoàng ThôngNo ratings yet

- Ketogenic Diet and Type One DMDocument9 pagesKetogenic Diet and Type One DMLara Z. AbuShqairNo ratings yet

- Ajuste Con Dosis PreviasDocument23 pagesAjuste Con Dosis PreviasOscar AlfonsoNo ratings yet

- Pilot Study of A Model-Based Approach To Blood Glucose Control in Very-Low-Birthweight NeonatesDocument9 pagesPilot Study of A Model-Based Approach To Blood Glucose Control in Very-Low-Birthweight NeonatesMoch Rizki DestiantoroNo ratings yet

- Treatment of Patients With Type 1 Diabetes Insulin Pumps or Multiple Injections 2016 Biocybernetics and Biomedical EngineeringDocument8 pagesTreatment of Patients With Type 1 Diabetes Insulin Pumps or Multiple Injections 2016 Biocybernetics and Biomedical EngineeringJose J.No ratings yet

- Burs Lem 2021Document13 pagesBurs Lem 2021ERINSONNo ratings yet

- Original Paper: World Nutrition JournalDocument6 pagesOriginal Paper: World Nutrition JournalSaptawati BardosonoNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Pharmaceutics: Lia Bally, Hood Thabit, Roman HovorkaDocument10 pagesInternational Journal of Pharmaceutics: Lia Bally, Hood Thabit, Roman HovorkaBrasoveanu GheorghitaNo ratings yet

- Goebel Fabbri 2008 Diabetes and Eating DisordersDocument3 pagesGoebel Fabbri 2008 Diabetes and Eating Disordersfilmstudio0510No ratings yet

- Glucose InsulineDocument5 pagesGlucose Insulinesaadshahab622No ratings yet

- Case StudyDocument3 pagesCase StudyAnnie Laiza BacayNo ratings yet

- Management of Hyperglycemia in Critical Care.5Document10 pagesManagement of Hyperglycemia in Critical Care.5nicho927No ratings yet

- Nutrisi Glikemik Kontrol 2Document11 pagesNutrisi Glikemik Kontrol 2Fera Ayu FitriyaniNo ratings yet

- Prevalence, Biochemical and Hematological Study of Diabetic PatientsDocument6 pagesPrevalence, Biochemical and Hematological Study of Diabetic PatientsOpenaccess Research paperNo ratings yet

- Why Is Premixed Insulin The Preferred Insulin? Novel Answers To A Decade-Old QuestionDocument3 pagesWhy Is Premixed Insulin The Preferred Insulin? Novel Answers To A Decade-Old QuestionDanielShenfieldNo ratings yet

- Hyperglycemia After Cardiac Surgery - Hebson2013Document6 pagesHyperglycemia After Cardiac Surgery - Hebson2013Dr XNo ratings yet

- Practice Tips: Insulin Protocols For Hospital Management of DiabetesDocument2 pagesPractice Tips: Insulin Protocols For Hospital Management of DiabetesEen AmaliaNo ratings yet

- Insulina DM2 PDFDocument11 pagesInsulina DM2 PDFGabriel VargasNo ratings yet

- HypoglicemicDocument20 pagesHypoglicemicAndreea CreangaNo ratings yet

- Title of The Research: Diabetes Mellitus By: Abdelrahman Gamal Course Title: Pharmacology Academic Year: Fourth 2019-2020Document11 pagesTitle of The Research: Diabetes Mellitus By: Abdelrahman Gamal Course Title: Pharmacology Academic Year: Fourth 2019-2020LAZKILLERNo ratings yet

- TM 15Document8 pagesTM 15Alfi LafitNo ratings yet

- Medicine: Allopurinol Use and Type 2 Diabetes Incidence Among Patients With GoutDocument7 pagesMedicine: Allopurinol Use and Type 2 Diabetes Incidence Among Patients With GoutGrady CoolNo ratings yet

- Garber 2007Document6 pagesGarber 2007Diana SamuezaNo ratings yet

- PAMW 2014-04 - WrobelDocument7 pagesPAMW 2014-04 - WrobelDiana SamuezaNo ratings yet

- How To Manage Steroid Diabetes in The Patient With CancerDocument5 pagesHow To Manage Steroid Diabetes in The Patient With CancerMade Dedy KusnawanNo ratings yet

- Carter 2020Document6 pagesCarter 2020oanadubNo ratings yet

- Feasibility Study Project Proposal RequirementsDocument2 pagesFeasibility Study Project Proposal RequirementsErick NgosiaNo ratings yet

- Unit3&4 Network TheoramsDocument73 pagesUnit3&4 Network TheoramsBALAKRISHNA PERALANo ratings yet

- Resource Guide For New ChrosDocument23 pagesResource Guide For New Chroslane.a.mcfNo ratings yet

- Full Download PDF of Test Bank For Exploring Marriages and Families, 3rd Edition, Karen Seccombe All ChapterDocument26 pagesFull Download PDF of Test Bank For Exploring Marriages and Families, 3rd Edition, Karen Seccombe All Chapterroosennwosu100% (4)

- What Every Musician Needs To Know About The Body: The Practical Application of Body Mapping To Making Music Bridget JankowskiDocument70 pagesWhat Every Musician Needs To Know About The Body: The Practical Application of Body Mapping To Making Music Bridget Jankowskicmotatmusic100% (6)

- MLD 201aDocument13 pagesMLD 201aChaucer19No ratings yet

- Attach 8 - CPDS Type 2ADocument401 pagesAttach 8 - CPDS Type 2AGlenn Adalia BonitaNo ratings yet

- Sfdunj Jkon PH 1F 3DM Mep 000014Document1 pageSfdunj Jkon PH 1F 3DM Mep 000014Syauqy AlfarakaniNo ratings yet

- Principal 5svbk8Document56 pagesPrincipal 5svbk8badillojdNo ratings yet

- Art AppreciationDocument10 pagesArt AppreciationJasmine EnriquezNo ratings yet

- (1142) Grade XI Admissions 2016-17Document7 pages(1142) Grade XI Admissions 2016-17Naveen ShankarNo ratings yet

- SUN - MOBILITY - PRIVATE - LIMITED - 2022-23 - Financial Statement - XMLDocument109 pagesSUN - MOBILITY - PRIVATE - LIMITED - 2022-23 - Financial Statement - XMLTanishq ChourishiNo ratings yet

- 3rdquarter Week7 Landslide and SinkholeDocument4 pages3rdquarter Week7 Landslide and SinkholeNayeon IeeNo ratings yet

- COT1-3rd HirarkiyaDocument49 pagesCOT1-3rd HirarkiyaRommel LasugasNo ratings yet

- Cyanotype Day 2 LessonDocument3 pagesCyanotype Day 2 Lessonapi-644679449No ratings yet

- Product Demo Feedback FormDocument1 pageProduct Demo Feedback FormVarunSharmaNo ratings yet

- Medications For Neonatal Resuscitation Program 2011 Canadian AdaptationDocument1 pageMedications For Neonatal Resuscitation Program 2011 Canadian AdaptationrubymayNo ratings yet

- Some, No, Any, EveryDocument2 pagesSome, No, Any, Everyvivadavid100% (1)

- METRIX AUTOCOMP - Company ProfileDocument2 pagesMETRIX AUTOCOMP - Company ProfileVaibhav AggarwalNo ratings yet

- What Is CommunicationDocument4 pagesWhat Is CommunicationsamsimNo ratings yet

- Puzzles: The Question: There Is Only One Correct Answer To This Question. Which Answer Is This? AnsDocument7 pagesPuzzles: The Question: There Is Only One Correct Answer To This Question. Which Answer Is This? AnsSk Tausif ShakeelNo ratings yet

- Nihongo Lesson FL 1Document21 pagesNihongo Lesson FL 1Lee MendozaNo ratings yet

- Essentials of Educational Psychology Big Ideas To Guide Effective Teaching 6Th Edition Jeanne Ellis Ormrod Full ChapterDocument67 pagesEssentials of Educational Psychology Big Ideas To Guide Effective Teaching 6Th Edition Jeanne Ellis Ormrod Full Chaptermarion.wade943No ratings yet

- Submarine Cable Installation ContractorsDocument19 pagesSubmarine Cable Installation Contractorswiji_thukulNo ratings yet

- Chapter 7 - Non Verbal CommunicationDocument7 pagesChapter 7 - Non Verbal CommunicationCarolyn NacesNo ratings yet

- Practice Quiz - Managing CollaborationDocument2 pagesPractice Quiz - Managing CollaborationMohamed RahalNo ratings yet

- Ruskin Bonds "THE KITE MAKER"Document14 pagesRuskin Bonds "THE KITE MAKER"Dhruti Galgali38% (8)