Professional Documents

Culture Documents

This Content Downloaded From 140.203.230.47 On Tue, 16 Nov 2021 21:06:35 UTC

This Content Downloaded From 140.203.230.47 On Tue, 16 Nov 2021 21:06:35 UTC

Uploaded by

Paul LynchCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Chapter 8 - System Oriented TheoryDocument8 pagesChapter 8 - System Oriented Theoryvitria zhuanita100% (1)

- Buchanan (1986) - Cultural Evolution and Institutional ReformDocument13 pagesBuchanan (1986) - Cultural Evolution and Institutional ReformMatej GregarekNo ratings yet

- Key Aspects of Corporate Organization Operating Policies and ControlDocument3 pagesKey Aspects of Corporate Organization Operating Policies and ControlConnie Miole Estrella50% (6)

- Amazon Case StudyDocument14 pagesAmazon Case StudyIvylize Pontes100% (1)

- Ebin - Pub - Politics in The Republic of Ireland 9781138119444 9781138119451 9781315652313 113811944xDocument445 pagesEbin - Pub - Politics in The Republic of Ireland 9781138119444 9781138119451 9781315652313 113811944xPaul LynchNo ratings yet

- Management (Chapter 11)Document9 pagesManagement (Chapter 11)JmNo ratings yet

- Business Policy 3Document20 pagesBusiness Policy 3Manish SinghNo ratings yet

- MB0052 - Strategic Management and Business Policy - Set 2Document10 pagesMB0052 - Strategic Management and Business Policy - Set 2Abhishek JainNo ratings yet

- Besr 1Document25 pagesBesr 1Kiko PontiverosNo ratings yet

- James S. Coleman - Constructed Organization. First PrinciplesDocument18 pagesJames S. Coleman - Constructed Organization. First PrinciplesJorgeA GNNo ratings yet

- Transaction Cost EconomicsDocument48 pagesTransaction Cost EconomicsvenkysscribeNo ratings yet

- Controladoria Texto InglesDocument26 pagesControladoria Texto InglesmarcosaalacerdaNo ratings yet

- The Past and Present of The Theory of The Firm: A Historical Survey of The Mainstream Approaches To The Firm in EconomicsDocument207 pagesThe Past and Present of The Theory of The Firm: A Historical Survey of The Mainstream Approaches To The Firm in Economicspwalker_25No ratings yet

- Wiley American Finance AssociationDocument26 pagesWiley American Finance AssociationBenaoNo ratings yet

- The Social Dimensions of EntrepreneurshipDocument44 pagesThe Social Dimensions of EntrepreneurshipPablo SelaNo ratings yet

- W2:Keohane - The Demand For International Regimes PDFDocument32 pagesW2:Keohane - The Demand For International Regimes PDFSnowyJcNo ratings yet

- Coase 1988 - The Nature of Firm - InfluenceDocument16 pagesCoase 1988 - The Nature of Firm - InfluenceAngélica AzevedoNo ratings yet

- University of Minnesota Law School: Legal Studies Research Paper Series Research Paper No. 16-38Document26 pagesUniversity of Minnesota Law School: Legal Studies Research Paper Series Research Paper No. 16-38Aditya GuptaNo ratings yet

- Vita e Pensiero - Pubblicazioni Dell'università Cattolica Del Sacro CuoreDocument30 pagesVita e Pensiero - Pubblicazioni Dell'università Cattolica Del Sacro Cuorekonsultan_rekanNo ratings yet

- Understanding Business Systems An Essay On The EcoDocument39 pagesUnderstanding Business Systems An Essay On The EcoLaura AquinoNo ratings yet

- The Theory of The Firm and The Evolutionary Games PDFDocument11 pagesThe Theory of The Firm and The Evolutionary Games PDFGaribello Zorrilla CamiloNo ratings yet

- What's "New" About New Forms of OrganizingDocument20 pagesWhat's "New" About New Forms of OrganizingAndrea VelazcoNo ratings yet

- A - I. Ogus - Law and Spontaneous Order - Hayek's Contribution To Legal TheoryDocument18 pagesA - I. Ogus - Law and Spontaneous Order - Hayek's Contribution To Legal TheoryedduardNo ratings yet

- M HBBDocument23 pagesM HBBsinginiwizNo ratings yet

- Organizational EconomicsDocument15 pagesOrganizational EconomicsbadriahNo ratings yet

- HamiltonDocument11 pagesHamiltonMonica BurgosNo ratings yet

- What Is A CorpDocument28 pagesWhat Is A CorpMrWaratahsNo ratings yet

- JeanMichelSahutMartaPeris-Ortiz Introduction SBE 10Document12 pagesJeanMichelSahutMartaPeris-Ortiz Introduction SBE 10kkkmmmNo ratings yet

- 8aa2 PDFDocument41 pages8aa2 PDFCooperMboromaNo ratings yet

- JeanMichelSahutMartaPeris-Ortiz Introduction SBE 10Document11 pagesJeanMichelSahutMartaPeris-Ortiz Introduction SBE 10soe sanNo ratings yet

- Properties of Emerging OrganizationsDocument14 pagesProperties of Emerging OrganizationsRafael LemusNo ratings yet

- Session 1Document16 pagesSession 1Mayank RunthalaNo ratings yet

- AMR - What's New About New FormsDocument20 pagesAMR - What's New About New FormsCatherine CifuentesNo ratings yet

- Corporate Governance: Western and Islamic Perspectives: January 2008Document20 pagesCorporate Governance: Western and Islamic Perspectives: January 2008Dila Fadiya FarrasNo ratings yet

- Stakeholder TheoryDocument20 pagesStakeholder Theorykuna9100% (1)

- Received January 1976, Revised Version Received July 1976Document55 pagesReceived January 1976, Revised Version Received July 1976nadiaNo ratings yet

- Economic Analysis of Law: January 2016Document7 pagesEconomic Analysis of Law: January 2016William TosinNo ratings yet

- The New Institutional EconomicsDocument12 pagesThe New Institutional EconomicsJean Carlo Lino ArticaNo ratings yet

- Accounting, Economics, and Law: Firm, Property and Governance: From Berle and Means To The Agency Theory, and BeyondDocument57 pagesAccounting, Economics, and Law: Firm, Property and Governance: From Berle and Means To The Agency Theory, and BeyondstuffsofasavantNo ratings yet

- 2003 IRAS 2003 Liberal BureaucracyDocument27 pages2003 IRAS 2003 Liberal BureaucracyYard AssociatesNo ratings yet

- Sem 12 Economics - of - Hybrids JITE 2004Document32 pagesSem 12 Economics - of - Hybrids JITE 2004Edna PossebonNo ratings yet

- Nahapiet 1997Document26 pagesNahapiet 1997mercylilianaNo ratings yet

- The Nature of FirmDocument21 pagesThe Nature of FirmMuhammad UsmanNo ratings yet

- North NewInstitutionalEconomics 1986Document9 pagesNorth NewInstitutionalEconomics 1986Prieto PabloNo ratings yet

- Journal of Financial Economics Volume 3 Issue 4 1976 (Doi 10.1016 - 0304-405x (76) 90026-x) Michael C. Jensen William H. Meckling - Theory of The Firm - Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and OwnersDocument56 pagesJournal of Financial Economics Volume 3 Issue 4 1976 (Doi 10.1016 - 0304-405x (76) 90026-x) Michael C. Jensen William H. Meckling - Theory of The Firm - Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and OwnersDiploma IV KeuanganNo ratings yet

- Modern Structural OrganizationsDocument20 pagesModern Structural OrganizationsAngelo PanilaganNo ratings yet

- Turnbull S, 1997 Corporate GovDocument27 pagesTurnbull S, 1997 Corporate GovMila Minkhatul Maula MingmilaNo ratings yet

- Freeman 2002Document20 pagesFreeman 2002Matheus ToledoNo ratings yet

- c1 PDFDocument10 pagesc1 PDFhumide sugaNo ratings yet

- Some Reflections On The Theoretical Concepts Involved in Corporate GovernanceDocument14 pagesSome Reflections On The Theoretical Concepts Involved in Corporate GovernancesunilkNo ratings yet

- The Firm As A Community of PersonsDocument13 pagesThe Firm As A Community of PersonsMaria H. KruytNo ratings yet

- Theory of IO, Sungjun Cho - ResumeDocument46 pagesTheory of IO, Sungjun Cho - ResumeHandy PraharjaNo ratings yet

- Jensen MecklingDocument71 pagesJensen MecklingAllouisius Tanamera NarasetyaNo ratings yet

- Aula 5. Item 2. Theory of The FirmDocument56 pagesAula 5. Item 2. Theory of The FirmJosie TotesNo ratings yet

- Scapens & Varoutsa 2010Document56 pagesScapens & Varoutsa 2010Derek DadzieNo ratings yet

- Suggestions For A Sociological Approach To The Theory of OrganizationsDocument16 pagesSuggestions For A Sociological Approach To The Theory of OrganizationsAmani MoazzamNo ratings yet

- Ai With More and More KMPsDocument75 pagesAi With More and More KMPsAyushman SinghNo ratings yet

- Ontracts As Rganizations: D. Gordon Smith & Brayden G. KingDocument45 pagesOntracts As Rganizations: D. Gordon Smith & Brayden G. KingANAS DAHHAKNo ratings yet

- Org TheoryDocument12 pagesOrg TheoryAyantika GangulyNo ratings yet

- Corporate Governance Lessons from Transition Economy ReformsFrom EverandCorporate Governance Lessons from Transition Economy ReformsNo ratings yet

- Microeconomics: Behavior, Institutions, and EvolutionFrom EverandMicroeconomics: Behavior, Institutions, and EvolutionRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (9)

- Research in Organizational BehaviorFrom EverandResearch in Organizational BehaviorB.M. StawRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- Reflexive Governance for Research and Innovative KnowledgeFrom EverandReflexive Governance for Research and Innovative KnowledgeNo ratings yet

- After the Flood: How the Great Recession Changed Economic ThoughtFrom EverandAfter the Flood: How the Great Recession Changed Economic ThoughtNo ratings yet

- Hayek's Tensions: Reexamining the Political Economy and Philosophy of F. A. HayekFrom EverandHayek's Tensions: Reexamining the Political Economy and Philosophy of F. A. HayekNo ratings yet

- The Use of Carbon Tax Funds 2020Document39 pagesThe Use of Carbon Tax Funds 2020Paul LynchNo ratings yet

- Jean-Baptiste Say and Spontaneous OrderDocument27 pagesJean-Baptiste Say and Spontaneous OrderPaul LynchNo ratings yet

- Spontaneous OrderDocument29 pagesSpontaneous OrderPaul LynchNo ratings yet

- FuelpricesHistory Sept 2021Document15 pagesFuelpricesHistory Sept 2021Paul LynchNo ratings yet

- Energies: Decoupling Economic Growth From Fossil Fuel Use-Evidence From 141 Countries in The 25-Year PerspectiveDocument21 pagesEnergies: Decoupling Economic Growth From Fossil Fuel Use-Evidence From 141 Countries in The 25-Year PerspectivePaul LynchNo ratings yet

- Adult Learning Prospectus 2020-Pages-26Document1 pageAdult Learning Prospectus 2020-Pages-26Paul LynchNo ratings yet

- Networks and States The Global Politics of Internet GovernanceDocument306 pagesNetworks and States The Global Politics of Internet GovernancePaul LynchNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Sociology in Our Times The Essentials 9th Edition KendallDocument40 pagesTest Bank For Sociology in Our Times The Essentials 9th Edition KendallKevinMillerbayi100% (34)

- Types of Matrix Organizational StructuresDocument3 pagesTypes of Matrix Organizational StructuresadrianeNo ratings yet

- Strategic Management 2 Strategic ManagementDocument48 pagesStrategic Management 2 Strategic ManagementMichael AsfawNo ratings yet

- Evidence 9 Workshop Cultural Awareness As A Key Element To NegotiateDocument8 pagesEvidence 9 Workshop Cultural Awareness As A Key Element To NegotiateMilton EscobarNo ratings yet

- Unit I Challenges of Organizational Behavior in IndiaDocument9 pagesUnit I Challenges of Organizational Behavior in IndiaDeepaPandeyNo ratings yet

- Portland Zone Guides (Updated 040824)Document16 pagesPortland Zone Guides (Updated 040824)Maine Trust For Local NewsNo ratings yet

- NBQP-Criteria For EnMS ConsultantDocument21 pagesNBQP-Criteria For EnMS ConsultantChandra KumarNo ratings yet

- Paper PR Ethics AustralianJournalDocument12 pagesPaper PR Ethics AustralianJournalReasat AhmedNo ratings yet

- Program Development ProcessDocument37 pagesProgram Development ProcessLeah NarneNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document51 pagesChapter 2CHANDHRIKKA RNo ratings yet

- Fom - Function of Management in SamsungDocument20 pagesFom - Function of Management in SamsungPooja ShekhawatNo ratings yet

- Leadership in Business: "Chapter 11 - Summary" "Leadership in Teams and Decision Groups"Document7 pagesLeadership in Business: "Chapter 11 - Summary" "Leadership in Teams and Decision Groups"Eka DarmadiNo ratings yet

- Administrative Law (Meaning, Definition and Scope)Document3 pagesAdministrative Law (Meaning, Definition and Scope)Ritesh kumarNo ratings yet

- Management Operation - Assignment 1 - BTEC HND - Semester 2020/ 2021Document17 pagesManagement Operation - Assignment 1 - BTEC HND - Semester 2020/ 2021tra nguyen thuNo ratings yet

- TM Decision GuideDocument14 pagesTM Decision GuideMahmoud Abd El GwadNo ratings yet

- EtopDocument7 pagesEtopAnilBahugunaNo ratings yet

- Teacher and The Community School Culture and Organizational LeadershipDocument74 pagesTeacher and The Community School Culture and Organizational Leadershipcha100% (2)

- SSP Template For Low Impact SysDocument22 pagesSSP Template For Low Impact Sysmatildabeecher3605No ratings yet

- Strategic-Management-Project-For-Tourism-Lecture01 2Document88 pagesStrategic-Management-Project-For-Tourism-Lecture01 2Lois RazonNo ratings yet

- Imap Job Description 917175737Document2 pagesImap Job Description 917175737reinlerNo ratings yet

- Journal of Information Technology Management: ISSN #1042-1319 A Publication of The Association of ManagementDocument14 pagesJournal of Information Technology Management: ISSN #1042-1319 A Publication of The Association of ManagementDessy Tjahyawati AtminegariNo ratings yet

- Leadership Final ReportDocument8 pagesLeadership Final ReportBitta Saha HridoyNo ratings yet

- Manuintro Bs PharmDocument27 pagesManuintro Bs Pharmheyyo ggNo ratings yet

- ChandlerDocument9 pagesChandlerSerwanga DavisNo ratings yet

This Content Downloaded From 140.203.230.47 On Tue, 16 Nov 2021 21:06:35 UTC

This Content Downloaded From 140.203.230.47 On Tue, 16 Nov 2021 21:06:35 UTC

Uploaded by

Paul LynchOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

This Content Downloaded From 140.203.230.47 On Tue, 16 Nov 2021 21:06:35 UTC

This Content Downloaded From 140.203.230.47 On Tue, 16 Nov 2021 21:06:35 UTC

Uploaded by

Paul LynchCopyright:

Available Formats

Orders and Organizations: Hayekian Insights for a Theory of Economic Organization

Author(s): Stavros Ioannides

Source: The American Journal of Economics and Sociology , Jul., 2003, Vol. 62, No. 3

(Jul., 2003), pp. 533-566

Published by: American Journal of Economics and Sociology, Inc.

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3487810

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The American Journal of

Economics and Sociology

This content downloaded from

140.203.230.47 on Tue, 16 Nov 2021 21:06:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

NOVEL INSIGHTS ABOUT ORGANIZATION

Orders and Organizations

Hayekian Insights for a Theory of Economic

Organization

By STAVROS IOANNIDES*

ABSTRACT. We explore the relevance to the theory of economic

organization of the distinction introduced by Hayek between two

kinds of social order: spontaneous orders and organizations. We argue

that Hayek's ideas lead to an understanding of the business firm

as a process, which comes very close to some of the core notions of

the evolutionary theory of the firm, while they still view the firm as

the outcome of a contract among asset owners. First of all, we put

forth a simple conceptual schema in order to differentiate between

contracts that lead to the formation of an organization and ordinary

market contracts. We then explore the conditions for an understand-

ing of the firm as a set of interconnected processes, rather than as an

end state. Finally, we introduce the concept of purposeful direction

as an important condition for the existence of the firm and we show

the history-contingent character of the firm's growth.

Introduction

ACCORDING TO THE standard periodization of Hayek's work, we have

to distinguish between early Hayek, the analytical economist, and the

*The author is Associate Professor of Economics at the Department of Political

Science and History, Panteion University, Athens, Greece. E-mail address:

stioan~panteion.gr. His research focuses on Austrian economics, evolutionary a

tutional economics, and the theory of the firm. A first version of this paper was pre-

sented to the Austrian Economics Colloquium at New York University in April 1999

and to the conference "Economic Analysis and Political Economy in the Thought of F.

A. Hayek" in Paris in May of the same year. The author wishes to thank David Harper,

Sanford Ikeda, Israel Kirzner, Roger Koppl, Mario Rizzo, Frederic Sautet, and Joe

Salerno for helpful comments. The usual disclaimer applies.

American Journal of Economics and Sociology, Vol. 62, No. 3 (July, 2003).

C 2003 American Journal of Economics and Sociology, Inc.

This content downloaded from

140.203.230.47 on Tue, 16 Nov 2021 21:06:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

534 American Journal of Economics and Sociology

mature Hayek, who focused on wider spheres of the social sciences

like social philosophy, political theory, and cognitive psychology.1

Taken literally, this periodization seems to imply that it is his early

period that may be of relevance for today's analytical economics. Con-

trary to this view, we will argue that contemporary economics has a

lot to learn even from that part of Hayek's work that is not purely

economic.

We focus here on Hayek's distinction between two types of social

order: spontaneous orders and organizations. Although he introduced

the two concepts in his effort to distinguish between the organizing

principles of the "Great Society" and those that pertain to purposeful

associations, we will argue that this distinction offers an important

starting point for a theory of economic organization, and especially

of the business firm. Of course, given that Hayek never attempted to

construct a theory of economic organization,2 our task here is not to

find in his work ideas that are simply not there but, rather, to "extract"

some insights from his analysis that are of central importance in the

modern theory of the firm.

This raises the question of how these insights relate to the two per-

spectives into which modern research on the firm is divided. The first

stems from the work of Coase (1937), Alchian and Demsetz (1972),

and Williamson (1975, 1985a) and is usually described as "contrac-

tarian." What unifies this work is that it views the firm as an optimal

contractual arrangement for the cooperation of a bundle of assets,

which comes about through a contracting process among their

owners. The second perspective comprises the "capabilities" theories

of the firm that stem from the work of Penrose (1959), Richardson

(1972), and Nelson and Winter (1982). This views the firm as a bundle

of capabilities, which are largely tacit and shared by the human assets

that constitute it. The latter strand has also developed an "evolution-

ary" branch, which, among other issues, emphasises (a) the endoge-

nous nature of the creation of the firm's capabilities, (b) the constant

emergence of variety in the characteristics of firms, and (c) the history-

contingent character of the firm's growth.3

We will show how Hayek's ideas lead toward this latter evolution-

ary approach to the study of business firms.4 Much more importantly,

however, we will argue that the insights we can extract from his

This content downloaded from

140.203.230.47 on Tue, 16 Nov 2021 21:06:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Hayek and a Theory of Economic Organization 535

distinction between spontaneous orders and organizations allow us

to construct an evolutionary approach to the firm that is character-

ized by two attributes. First, it introduces an understanding of the

business firm as a process, in contrast to the static outlook of con-

tractarian theories, while still allowing us to describe the firm as the

outcome of a contracting process among asset owners. The impor-

tance of this line of analysis cannot be overestimated, because it indi-

cates the possibility of constructing a unified theoretical framework

for the analysis of firms, in which the concepts of contracts, growth

processes, capabilities, and historical contingency can be applied

simultaneously to the study of business organization.

Our analysis proceeds as follows. We begin (Section II) with a pres-

entation of Hayek's distinction between spontaneous orders and

organizations, as it appears in his mature work and especially in

Volume 1 (1973) of his Law, Legislation and Liberty. We then proceed

(Section III) to put forth a simple conceptual schema in order to

differentiate between contracts that lead to the formation of an

organization and ordinary market contracts. In Section IV we set the

conditions for an understanding of the firm as a process, rather than

as an equilibrium phenomenon, as conceptualized by contractarian

theorists. Section V introduces the concept of purposeful direction as

an important condition for the existence of the firm and establishes

the history-contingent character of its exercise. Finally, Section VI

summarizes our conclusions.

II

Hayek on Spontaneous Order and Organization

ONE OF THE FEATURES of Hayek's work that makes it especially relevant

for the study of economic organization is the fact that, in his mature

work, he abandoned the concept of equilibrium of mainstream eco-

nomics in favor of that of order. Hayek explains the reasons for this

conceptual innovation as follows:

The concept of an "order" which ... I prefer to that of equilibrium, has

the advantage that we can speak about an order being approached to

varying degrees, and that order can be preserved throughout a process of

change. (1968:184)

This content downloaded from

140.203.230.47 on Tue, 16 Nov 2021 21:06:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

536 American Journal of Economics and Sociology

At least three points must be noted in the above statement. The

first is that the concept of order is entirely compatible with "a process

of change," therefore, it is independent of end states and has time as

an essential element. The second is that an order can be approached

"to varying degrees." In other words, we may describe a phenome-

non as forming an order even though, at any point in time, it

may not display all the characteristics that the theorist considers as

describing-belonging to-that order. Finally, if an order is produced

through human action it must also be constantly maintained and

reproduced through that action.5

The fact that an order is perceived as a continual process unfold-

ing in real time means that its essence must not be sought in the

uniformity of the actions of the individuals that constitute it, nor in

the physical continuity of the individuals themselves. Rather, the con-

tinuity must be sought in the general character of the actions that the

social scientist observes in its functioning.6 On this basis, Hayek

proceeds to define an order:

[Als a state of affairs in which a multiplicity of elements of various kinds

are so related to each other that we may learn from the acquaintance with

some spatial or temporal part of the whole to form correct expectations

concerning the rest. (1973:36)

Let us note here Hayek's emphasis on the notion of acquaintance,

which opens up a whole series of epistemological questions on how

the social scientist "gets acquainted" with the patterns of actions that

arise in a spatial or temporal part of an order and how he or she pro-

ceeds to construct mentally the overall order on that basis. However,

epistemological considerations aside, Hayek does raise a problem that

this acquaintance faces, which arises from the character of the order

itself. Thus, he introduces the distinction between "abstract" and "con-

crete" orders. Regarding the former, and taking the market order as

a case in point, Hayek maintains that:

We cannot see, or otherwise intuitively perceive, this order of meaning-

ful actions, but are only able mentally to reconstruct it by tracing the rela-

tions that exist between the elements. We shall describe this feature by

saying that it is an abstract and not a concrete order. (1973:38)

By contrast, the orders that he describes as "concrete" can be per-

ceived intuitively by inspection, i.e., without the social scientist having

This content downloaded from

140.203.230.47 on Tue, 16 Nov 2021 21:06:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Hayek and a Theory of Economic Organization 537

to mentally reconstruct their function or having to construct a theory

in order to explain them. Taking now man-made order, rather than

spontaneous order, as a case in point, Hayek proceeds to describe

concrete orders:

Such orders are relatively simple or at least necessarily confined to such

moderate degrees of complexity as the maker can still survey; they are

usually concrete in the sense just mentioned that their existence can be

intuitively perceived by inspection; and, finally, having been made delib-

erately, they invariably do (or at one time did) [our emphasis] serve a

purpose of the maker. (1973:38)

There are a number of points that need to be stressed in connec-

tion with Hayek's distinction between abstract and concrete orders.

First, in the above two quotations, spontaneous and man-made orders

are depicted as examples of abstract and concrete orders, respectively.

However, they are just that: examples or illustrations. Hayek does not

mean that there is a one-to-one relation between these concepts, i.e.,

that spontaneous orders are necessarily abstract and man-made orders

necessarily concrete.7 In fact, he stresses (ibid.) that what distinguishes

spontaneous from man-made orders is the degree of complexity they

can achieve. Therefore, their respective abstractness or concreteness

is directly linked to their complexity.

There is a second point that is even of greater interest in the second

of the above quotations. Hayek seems to suggest that one reason that

explains the concreteness of a man-made order is the fact that it is a

deliberately constructed arrangement, which thus serves a purpose of

its maker. However, he immediately qualifies this position when he

says, as we have emphasised, "or at one time did." What he means

is that even man-made orders can develop to such a degree of com-

plexity that their character may change from concrete to abstract.

There is a third important consideration. If man-made orders can

evolve to an ever increasing degree of complexity-and, therefore,

abstractness-and if they can evolve to be independent of purpose,

as Hayek implies, can their character change through that process to

that of a spontaneous order? Hayek's statement does not seem to pre-

clude such an eventuality. On the other hand, that would entirely

undermine his insistence-which, after all, constitutes the cornerstone

of his social theory-on a rigid distinction between the two types of

This content downloaded from

140.203.230.47 on Tue, 16 Nov 2021 21:06:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

538 American Journal of Economics and Sociology

order. Given this, we interpret his statement as meaning that, as a

man-made order develops in complexity, the purpose that it serves,

or the original agency behind the original purpose, may change. On

this account, therefore, purpose remains a distinguishing feature of

man-made orders, even though the purpose itself may change as

the complexity of the order increases. The importance of these con-

siderations for a theory of economic organization will become evident

in Section V below.

We have already touched upon Hayek's distinction between two

broad categories of order: "grown" and "man-made" orders or, accord-

ing to the terminology he chooses after the brief introduction of this

distinction: spontaneous orders and organizations. Note that both

categories are simply divisions of the same general concept, that of

order. This is important because, to the extent that we agree with

Hayek that the concept of order constitutes an alternative to that of

equilibrium, then the concept of order becomes relevant for a theory

that attempts to explain economic organization not in terms of static

equilibrium but rather in terms of dynamic processes. But before we

proceed to examine how Hayek's ideas might help us in that direc-

tion, it is important that we examine in greater detail how he

supports the distinction between the two types of order.

The key here is the role of purposeful agency. A spontaneous order

is one that is produced and reproduced through the actions of indi-

viduals, although the exact form of the resulting order was not, and

could not have been, designed by any one individual. By contrast,

the distinguishing element of organizations is precisely the fact that

they are, both in their creation as well as in their operation, the result

of a directing intelligence. Hayek makes the distinction starkly:

The distinction of this kind of order [i.e., spontaneous] from one which

has been made by somebody putting the elements of a set in their places

or directing their movements is indispensable for any understanding of

the processes of society as well as for social policy. (1973:37)8

If the existence or non-existence of a directing intelligence consti-

tutes the major element on which Hayek builds the distinction

between the two types of order, the question of how order is created

and maintained is only relevant for that class of orders that he

This content downloaded from

140.203.230.47 on Tue, 16 Nov 2021 21:06:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Hayek and a Theory of Economic Organization 539

describes as spontaneous. Organizations, on the other hand, are

both created and maintained through the purposeful action of a com-

manding authority that puts "the elements of a set in their places."

Hayek's answer is that "the formation of spontaneous orders is the

result of their elements following certain rules in their responses to

their immediate environment" (ibid., p. 43). This statement raises

further questions that concern the nature of these rules, their origin,

and the exact ways in which their following leads to the formation

of spontaneous orders.

The first point that must be stressed concerning the nature of the

rules of conduct is that they are largely tacit. Although, as we will

see below, Hayek admits that some part of the rules governing the

behavior of the elements of a spontaneous order may be formally

constituted and, thus, explicit, he insists that there must always exist

a sub-stratum of tacit rules for a spontaneous order to exist:

[T]he term rule is used for a statement by which a regularity of the conduct

of individuals can be described, irrespective of whether such a rule is

known to the individuals in any other sense than that they normally act

in accordance with it. (1967:67)

Therefore, although rules of conduct have to be known by the ele-

ments of a spontaneous order, for only if they are known can they

be obeyed, this knowledge need not be articulable. In fact, it cannot

be an entirely articulable kind of knowledge, for, if it were, rules

could be scrutinized rationally and thus become the object of collec-

tive action, a possibility that would undermine the character of

spontaneous orders as independent of a directing intelligence.

Secondly, the rules of conduct must be largely negative rather than

positive; i.e., they must mostly determine what range of actions is

permissible in a specific situation, rather than particular actions.

Again, if rules were to prescribe particular actions, then we might as

well not talk about spontaneous order but rather about the unifor-

mity of all actions in specific circumstances. Hayek makes the point

explicitly:

[Rules] will often merely determine or limit the range of possibilities within

which the choice is made consciously. By eliminating certain kinds of

action altogether and providing certain routine ways of achieving the

object, they merely restrict the alternatives on which a conscious choice

This content downloaded from

140.203.230.47 on Tue, 16 Nov 2021 21:06:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

540 American Journal of Economics and Sociology

is required.... [The] rules which guide an individual's action are better

seen as determining what he will not do rather than what he will do.

(1967:56)

Precisely because the nature of the rules of conduct is negative

rather than positive, Hayek often refers to them as abstract. In fact,

he directly links the abstract character of the rules individuals follow

with the abstract nature of the resulting order.9 Indeed, we have

already seen that the abstractness of the resulting order is linked to

its complexity. Therefore, if the rules were not abstract-i.e., if they

prescribed concrete actions-the resulting order would be neither

abstract nor of any significant degree of complexity. In turn, the

abstractness of the rules of conduct implies also that they must be

general, in the sense that they must be valid for all individuals and

that they must be applicable to an infinite number of future instances.

We can now turn to the problem of the origins of the rules

of conduct. Hayek maintains that these rules originate from three

different sources:

Some such rules all individuals of a society will obey because of the

similar manner in which their environment represents itself to their minds.

Others they will follow spontaneously because they will be part of their

common cultural tradition. But there will be still others which they may

have to be made to obey, since, although it would be in the interest of

each to disregard them, the overall order in which the success of their

actions depends will arise only if these rules are generally followed.

(1973:45)

Some discussion of the three sources of rules of conduct is now

needed. The first source lies outside the objects of social science, as

it relates to human physiology. By contrast, the second source is,

according to Hayek, the object of social science. In fact, he bases

his whole social theory on this type of rules and on how they have

evolved spontaneously through the ages. Now, the third source is

interesting because it comprises rules, the obedience to which must

be enforced. The significance of this category of rules lies in the fact

that, since they have to be enforced by some public authority, they

must be explicit rather than tacit.

It is important to note that what in fact Hayek proposes in the

above quotation is only a classification of the various origins of the

This content downloaded from

140.203.230.47 on Tue, 16 Nov 2021 21:06:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Hayek and a Theory of Economic Organization 541

rules, and not a hierarchical ranking of the importance of each for

the formation of spontaneous orders. Of course, the primacy of the

first source-human physiology-is self-evident. With reference to the

other two sources of rules, however, things are not so straightforward.

Furthermore, Hayek maintains that it is conceivable that a sponta-

neous order may rest entirely on rules that have been deliberately

designed:

Although undoubtedly an order originally formed itself spontaneously

because the individuals followed rules which had not been deliberately

made but had arisen spontaneously, people gradually learned to improve

those rules; and it is at least conceivable that the formation of a sponta-

neous order relies entirely on rules that were deliberately made. The spon-

taneous character of the resulting order must therefore be distinguished

from the spontaneous origin of the rules on which it rests, and it is

possible that an order which would still have to be described as spon-

taneous rests on rules which are entirely the result of deliberate design.

(1973:45-46, emphasis added)"0

There are two points worth stressing here. The first is Hayek's dis-

tinction between the spontaneous origins of the rules on which an

order rests and the spontaneous character of the order itself. The

significant argument here is that, even if all rules are deliberately

designed, a spontaneous order may still result provided that these

rules have all the attributes that we have discussed above, i.e.,

abstractness, generality, and independence of purpose.

But there is a second point, which is of special relevance for a

theory of economic organization. As we have emphasised, Hayek

maintains that a spontaneous order "undoubtedly" formed itself

originally through the obedience of individuals to rules of conduct,

which were themselves spontaneous. He adds, however, that people

gradually learned to improve these rules, thus transforming them to

deliberately designed rules. What Hayek seems to imply here, there-

fore, is that a spontaneous order resting on deliberately designed rules

is only conceivable if these rules are merely improvements of the

original spontaneous rules that gave rise to the order in the first place.

Therefore, to the original criterion for the characterization of orders-

spontaneous orders resting on abstract rules, organizations resting on

specific commands-he now adds a further criterion: whether the

This content downloaded from

140.203.230.47 on Tue, 16 Nov 2021 21:06:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

542 American Journal of Economics and Sociology

origins of each type of order are spontaneous or deliberately

designed. What is implied here is an ontogenetic approach to the for-

mation of orders, where the original traits are supposed to determine

fully the final character of every structure, at least as far as the general

class of structures to which it will belong-i.e., spontaneous orders

or organizations-is concerned.

There remains a final issue concerning the role of rules of conduct:

the way in which the following of rules leads to the creation of an

order. Central for this are Hayek's views on ignorance, as the condi-

tion that may best describe the situation that every agent faces when

contemplating what sort of action to pursue. The fact that humans

are depicted as acting in conditions of ignorance means that whether

their actions will lead to the formation of an order or, possibly, to

complete disorder depends on whether the social environment

allows them to pursue actions that tend to be coordinated or not.

Fleetwood describes precisely this link between ignorance and

coordination:

Any notion of order that is more than a formal description of the condi-

tions necessary for equilibrium must explain how agents initiate actions

that are relatively spatio-temporally coordinated with one another under

the really existing situation of incomplete knowledge ... Hayek reasons

that actions may be coordinated if plans are coordinated, which depends

upon the coordination of expectations, which in turn is based upon agents

having access to knowledge ... of what others are doing or intend to do.

(1995:94)

What Fleetwood in fact describes here is the knowledge require-

ments for the creation of an order. It is precisely these requirements

that are met by the obedience to rules. In the case of organizations,

the creation of order is ensured by the fact that the commands that

actually create them flow from one central intelligence. In the case

of spontaneous orders, on the other hand, no such central intelligence

exists. Therefore, in this case, the obedience to rules of conduct helps

agents cope with the perennial condition of ignorance in which they

inescapably find themselves, by augmenting the knowledge at their

disposal in a double sense: first, by allowing them to draw from the

experience of dealing with specific situations that is embodied in

these rules, and second, by making the actions or expected actions

This content downloaded from

140.203.230.47 on Tue, 16 Nov 2021 21:06:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Hayek and a Theory of Economic Organization 543

of other agents intelligible, for the simple reason that they themselves

are based on obedience to the same rules of conduct.

Therefore, rules help the spontaneous creation of orders through

the coordination of the plans and actions of individual agents. In turn,

this is achieved because rules assist agents to pierce through the igno-

rance in which they find themselves and to obtain knowledge-or to

act as ifthey possessed knowledge, which in actual fact they do not.

Thus, it is not only that rules facilitate action by dispersing the veil

of ignorance that confronts individual action, but they also allow

agents to make fuller use of the tacit knowledge that they uncon-

sciously possess. It follows that, the more abstract and negative the

rules are, i.e., the more they do not restrict freedom of action, the

more complex the resulting order, in the sense that the observed

range of actions will tend to be greater.

We have seen that, according to Hayek, the issue of rules versus

commands constitutes the major distinguishing characteristic of

spontaneous orders and organizations. However, he feels the need to

somewhat qualify this statement by accepting a role for rules in

organizations, although in this case the rules differ in important

respects from the rules that lead to the formation of spontaneous

orders. For a theory of the firm this is an important conceptual

development because, as we have argued elsewhere (loannides

1999a), the acceptance of even a limited role of rules in the firm takes

us away from the neoclassical view of the firm as a production

function-an arrangement in which all the elements obey a single

will in pursuing the maximization of profits. In terms of Hayek's

schema, this is an important qualification for a further reason. An

organization run entirely by commands could only reach a limited

degree of complexity, as it would be unable to make use of the

tacit knowledge possessed by its members. Therefore, as Hayek

maintains:

Every organisation in which the members are not mere tools of the organ-

iser will determine by commands only the function to be performed by

each member, the purpose to be achieved, and certain general aspects of

the methods to be employed, and will leave the detail to be decided by

the individuals on the basis of their respective knowledge and skills.

(1973:49)

This content downloaded from

140.203.230.47 on Tue, 16 Nov 2021 21:06:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

544 American Journal of Economics and Sociology

Hayek admits that even in organizations, and depending on the

degree of complexity the commanding authority wishes to achieve,

the latter may also employ rules rather than merely commands for

the operation of the organization:

The more complex the order aimed at, the greater will be the part of the

separate actions which will have to be determined by circumstances not

known to those who direct the whole, and the more dependent control

will be on rules rather than on specific commands. In the most complex

types of organizations, indeed, little more than the assignment of partic-

ular functions and the general aim will be determined by commands of

the supreme authority, while the performance of these functions will be

regulated only by rules. (1973:50)

However, Hayek adds that "[r]ules of organization are thus sub-

sidiary to commands, filling in the gaps left by commands" (ibid., p.

49). Thus, he implies that the rules of organization are themselves the

creation of purposeful authority, and can only develop on a substra-

tum of authority relations. Furthermore, the fact that the rules of

organization originate in authority means that their character is essen-

tially different from that of the rules that lead to the formation of

spontaneous orders. Therefore, Hayek (ibid., p. 48) maintains that the

rules in the context of organizations are characterized by three attrib-

utes that distinguish them from the rules that are pertinent in the case

of orders: (1) they are not as abstract, since they must still guide the

actions of agents in specific directions; (2) they are not tacit but

explicit, since the commanding authority needs to ensure that all

agents will obey them; and (3) they are specific to the particular posi-

tion in the organization that an agent occupies.

III

In the Beginning There Were Markets?

THE TIThE OF THIS SECTION is derived from Oliver Williamson's (1975:20)

well-known remark. The deeper meaning of this statement, which

incidentally is shared by all theorists in the contractarian per-

spective on the firm, is that any form of economic organization,

including the business firm, must be thought of as having evolved

out of market exchange. Implicit in this statement is, therefore, a

This content downloaded from

140.203.230.47 on Tue, 16 Nov 2021 21:06:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Hayek and a Theory of Economic Organization 545

demand on theory to explain under what conditions resources with-

draw from the market in order to commit themselves to an organi-

zation. Coase (1937) explains it on the basis of the concept of

transaction costs. Alchian and Demsetz (1972), on the other hand,

explain it on the basis of the increase in technical efficiency brought

about by "team production." The former thus describes the emergence

of the firm as involving the supercession of the market, while the latter

view the firm itself as a quasi-market. The important thing to note,

however, is that for both approaches, it is the market that is given

conceptual priority.

Hayek's position on this issue is less straightforward. The sponta-

neous order of the market is a rather recent historical phenomenon.

Arguably, therefore, in historical time organizations may have pre-

ceded orders that approached the ideal of spontaneity. One can think

of a whole array of such organizations, some of them still around

today, from clans, families, states, and armies, to amateur sport

teams.11 In each of these cases the central characteristic of organiza-

tion is present-members are subject to a command structure-but

their emergence may have taken place in contexts that have nothing

to do with the spontaneous market order.

However, here we are interested in one specific kind of organiza-

tion: the business firm. Although, historically, firm-like forms may

have emerged in institutional frameworks that differ greatly from the

spontaneous market order as we know it today, there can be little

doubt that the modern business firm presupposes the existence of

that order, i.e., it is embedded in it. There are two attributes of the

firm that necessitate this. The first is that it is an organization whose

membership is entirely voluntary.12 The second stems from the fact

that it constitutes a unitary actor in the markets for inputs and outputs.

Therefore, its operation in these markets presupposes an institutional

framework that makes this operation possible. Thus, there seems to

be a prima facie similarity between the views of Hayek and those of

contractarian theorists.

And yet that would be a misleading conclusion. The fact that the

organization of the modern business firm is embedded in the spon-

taneous market order should not be taken to mean that it has emerged

out of ordinary market contracting. But this only begs the question:

This content downloaded from

140.203.230.47 on Tue, 16 Nov 2021 21:06:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

546 American Journal of Economics and Sociology

In what way does the contracting process that brings the firm into

existence differ from ordinary contracting in the marketplace? The

answer we can derive from Hayek's distinction between orders and

organizations is that the latter are always characterized by the exis-

tence of a purpose or, to put it in different terms, that an organiza-

tion presupposes an "organizer," not necessarily as a physical person

but certainly as a locus of purpose. Therefore, while we can envis-

age the firm as coming about through a process in which various

resource owners contract, in the organization, its existence itself

hinges on something distinct from this contracting process: the

fact that the organization is already-i.e., even before its formal

emergence-infused with a purpose.

Let us try to work out the microanalytics of this assertion. Imagine

three types of agents (A, B, and C), who all enter into contracts for

the exchange of resources, goods, and services with agent D. For our

purposes here, we can think of agent D as constituting the legal

person of "the firm." Agents of type A enter into spot transactions

with D; thus we can think of them either as suppliers or as customers

of D. Each transaction between a type A agent and agent D is always

perceived by both as an one-off deal that does not build a relation

between them after its completion. Agents of type B enter into long-

term relations with D, in the sense that, although they remain the

owners of their assets, the value of those assets is affected by D's

behavior. Their relation with D may be upstream (e.g., subcontrac-

tors, long-term suppliers, creditors, workers, etc.) or downstream

(e.g., customers of D who value the continued relation with the firm).

Finally, type C agents enter into a special kind of contractual relation

with D under which they transfer the ownership of their assets to

D in exchange for a share of D. Obviously, the value of this share

is affected by D's behavior. Table 1 summarizes the major attributes

of these three types of contracts.

The important thing to note is that the contracts between any type

of A, B, or C agents and agent D can be thought of as standard con-

tracts governing the exchange of property rights to assets or final

goods and services. Presumably, every agent must be considered as

having his or her own purpose for entering such a contract. However,

there is an important difference between A-D contracts, on the one

This content downloaded from

140.203.230.47 on Tue, 16 Nov 2021 21:06:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Hayek and a Theory of Economic Organization 547

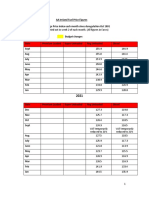

Table 1

Type of Character of Submission to Exit or voice options for

contract exchange D's authority agents A, B, and C

A-D Spot NO (symmetry Exit

of agents'

purposes)

B-D Long-term YES (asymmetry Voice but possibility

of agents' of exit on contract

purposes) completion

C-D Transfer of YES (asymmetry Voice but possibility

ownership of agents' of exit by abandoning

purposes) ownership of D

hand, and B-D and C-D, on the other. The former, having as they do

the character of spot exchanges, are characterized by a symmetry of

the agents' purposes, in the sense that neither party in the contract

can impose his or her purposes on the other. In contrast, the latter

are characterized by an asymmetry, for although both parties in the

contract have their own purposes for entering it, it is D's purposes

that acquire special importance as soon as the contract is entered into,

i.e., expostfacto.

The above schema is very close to the idea described by Williamson

(1985a:61) as the "fundamental transformation" in contractual rela-

tions, which stems from the fact that contracts have both ex ante as

well as ex postfacto implications for the relations between the con-

tracting parties."3 With Williamson, we view B-D and C-D contracts

as giving rise to an organization, whereas A-D contracts do not.

However, unlike Williamson-who insists that this transformation can

be explained by transaction cost considerations-and with Hayek, we

consider this transformation to arise from the fact that agent D is in

a special position through which he or she is able to subject the

resources of agents B and C to his or her purposes. Therefore, agent

D must be viewed as a special kind of agent: an entrepreneur. Note

that this description is consistent both with Israel Kirzner's (1973)

This content downloaded from

140.203.230.47 on Tue, 16 Nov 2021 21:06:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

548 American Journal of Economics and Sociology

theory of entrepreneurship as well as with that of Ludwig Lachmann

(1956). For the former, the major characteristic of entrepreneurial

behavior is the discovery of profit opportunities, while, for the latter,

the entrepreneur is the agent who decides the structure of capital

goods in a process of production.14 Obviously, agent D can do exactly

that with the resources that agents B and C contribute.

However, in Hayek's ideas, whose relevance for economic organ-

ization we are exploring here, organizations are not only character-

ized by purpose, but also by the fact that they constitute command

structures. Actually, it is the fact that commands are needed for the

running of the organization that ensures that purpose will always be

a distinguishing characteristic of this type of order. But how consis-

tent is the fact that organizations are run by commands with the frame-

work proposed above? Or, to put the same question in different terms,

how can the concept of authority-which the notion of command

implies-be reconciled with the idea of voluntary participation in the

organization, which is implied by the fact that all agents enter into

their contracts with agent D entirely voluntarily?

In fact, the ideas of voluntary contracting and authority can be rec-

onciled if we consider the submission to the authority of agent D to

be part of the contract that agents B and C decide to accept.15 There-

fore, in order that type B-D and C-D contracts do not amount to an

abolition of voluntary contracting, we have to assume that the parties

to these contracts retain the option to exit the arrangement at con-

tract completion. In fact, we can think of type A-D, B-D, and C-D

contracts as a continuum from arrangements that grant priority to the

exit option, to arrangements that represent mixes of both exit and

voice options.16 It is precisely because the possibility to exit the organ-

ization remains open that the fact that the parties agree to a contract,

which gives agent D effective authority over their resources, does not

violate the voluntary nature of the contracting process, nor does it

thereby cancel the fact that organizations must still be viewed as

springing from spontaneous orders.'7

Is the above schema consistent with Hayek's views on spontaneous

orders and organizations? We believe that it is, as it retains two of his

key ideas: first, that organization springs from spontaneous order and

second, that the major distinguishing characteristic of organization is

This content downloaded from

140.203.230.47 on Tue, 16 Nov 2021 21:06:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Hayek and a Theory of Economic Organization 549

that it is infused with a purpose. In this account, therefore, business

firms must be viewed both as emerging from the market process and

as being something distinct from the spontaneous market order. The

question we now have to address is how this account of the nature

of business firms compares with the ideas of the contractarian

perspective on the firm.

The nexus-of-contracts strand of the contractarian perspective

(Alchian and Demsetz 1972; Jensen and Meckling 1986; Fama 1980)

views the firm as a quasi-market. Agents participating in the firm are

thus viewed as entering into spot contracts with it, through which

they are able to effectively control the value of their resources and

to ensure optimization. Because contracts binding all parties are

viewed as ensuring efficiency ex ante, there is no such thing as a

"fundamental transformation." Thus purpose is not seen as an essen-

tial element of the organization, except in the trivial sense that it is

diffused among all contracting parties in the same sense that all

market dealings presuppose that agents have their own purposes for

conducting them. On these grounds, in the original formulation of

this approach, Alchian and Demsetz (1972:779) explicitly criticize

Coase (1937) for admitting a role for authority in his account of the

nature of the firm.'8 Viewing the firm as a nexus-of-contracts, this

approach considers the exit option as the only available option for

contracting parties, quite in line with standard market exchanges.

By contrast, our Hayekian view of the business firm seems to share

important insights with the transaction costs approach. The empha-

sis on the issue of authority was already explicit in the first formula-

tion of the paradigm by Coase (1937:393), where he describes the

firm as coming about through the decisions of asset owners to assign

the use of their resources to an entrepreneur-organizer, based on

transaction costs considerations. This attitude is also evident in

Williamson's notion of the fundamental transformation of contractual

relations (1985a), which we have already mentioned.'9 It is also

evident in the "incomplete contracts" theory of the firm (Grossman

and Hart 1986; Hart 1995)-arguably an off-shoot of the transaction

costs approach-which does not merely emphasize ownership but

also argues that which of the parties in a vertical relationship becomes

the owner of joint assets has vast efficiency implications. The rele-

This content downloaded from

140.203.230.47 on Tue, 16 Nov 2021 21:06:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

550 American Journal of Economics and Sociology

vance of the latter approach for our Hayekian schema are even more

important, as Hart's account seems to be in a position to decisively

link the locus of command with that of purpose.

However, unlike transaction costs theory, the Hayekian approach

that we are developing here does not depend on the type of trans-

actions that the parties contract for and the costs associated with them.

In our account, what distinguishes economic organizations such as

the firm from the market is the special purpose of a specific agent to

set up an organization (agent D in our schema), i.e., the entre-

preneurial element in firm creation. It follows that, although the

specific attributes of a transaction may indeed have important impli-

cations for the organizational arrangement that the parties will seek

to establish, the business firm as a general category of economic

organization must be thought of as independent of these specific

attributes of transactions.

Let us sum up our discussion in this section. Hayek's approach to

organizations is certainly consistent with the view that "in the begin-

ning there were markets." However, the "in the beginning" part of

this sentence has a different meaning for Hayek. It does not merely

refer to the fact that the contracting process that brings the firm into

existence is taking place within the context of market institutions-

i.e., the spontaneous market order-but, most importantly, that this

contracting process is driven by the purpose of an agency that is

aiming to set up an organization.

IV

The Firm: Equilibrium or Order?

WHAT UNIFIES THE contractarian perspective on the firm as a research

program is that it attempts to analyze the existence, function, and

scope of economic organization by applying the tools of standard

neoclassical theory.20 Prominent among these is the notion of equi-

librium. This prominence is most evident in what is usually described

as the nexus-of-contracts approach to the firm. Thus, Demsetz

(1988:194) describes the theory of the firm as the theory of the equi-

librium business organization. Jensen and Meckling argue that "the

behavior of the firm is like the behavior of a market: i.e., the outcome

of a complex equilibrium process" (1986:220). However, transaction

This content downloaded from

140.203.230.47 on Tue, 16 Nov 2021 21:06:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Hayek and a Theory of Economic Organization 551

costs theory broadly shares this preoccupation with equilibrium, as it

is evident from Coase's (1937) account of the determination of the

boundaries of firms. By contrast, we have seen that Hayek explicitly

introduces the concept of order as an alternative to that of equilib-

rium. In his account, as we have also seen, what distinguishes orders

from equilibrium states is, first, that they must be conceived of as

processes unfolding in real time and, second, that they must be

thought of as structures within which the operation of their con-

stituent elements is constantly coordinated. Based on Hayek's concept

of order, and bearing in mind that organizations constitute orders of

a special kind, the question that arises is in what way this view differs

from the equilibrium account of the business firm of contractarian

approaches.

We will now attempt to construct a concept of the business firm

as an order. We may begin by establishing the factors that must be

thought of as maintaining the firm as a productive organization.

Obviously, the benchmark we propose here is one that says that the

firm will either exist or not, and, if the former is the case, we need

to establish the conditions for its existence in a dynamic framework.

This means that these conditions must not be thought of as static

requirements for the firm to exist, but that they must be themselves

perceived as processes.

Condition 1

Agent D-i.e., the "firm"-must maintain positive participation rents

for agents of types A, B, and C, in order to ensure their continued

participation in the organization. Note that the concept of rent is here

used in a subjectivist sense, i.e., it relates to the subjective opportu-

nity remuneration that each agent believes to be feasible. It follows

that what is important for the maintenance of the firm as a produc-

tive organization is not the continuity of the participation of specific

agents but, rather, the continuity of the supply of specific services.

Condition 2

Agent D must be in a position to coordinate the actions of agents A,

B, and C. There are two senses in which agent D must be thought

This content downloaded from

140.203.230.47 on Tue, 16 Nov 2021 21:06:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

552 American Journal of Economics and Sociology

of as coordinating the actions of others. First, this coordination must

bring about a structure of the resources that agents A, B, and C

contribute, which is appropriate for the attainment for the firm's

objectives-i.e., agent D's purpose, as we discussed in the previous

section. Second, agent D must be in a position to (a) absorb the

knowledge obtained by the constituents of the firm in the process of

production, (b) take this knowledge into consideration in the pursuit

of his or her purpose and, most importantly, (c) revise the initial

purpose on the basis of it.21 It is obviously in this latter sense that the

idea of coordination acquires a really dynamic quality.

Condition 3

The purpose of agent D, the "firm," must be accepted by the market;

to put it another way, the firm's products must find customers. Note

that this is not meant to signify anything more than that, somehow,

the objectives of the firm do not prove to be entirely unsustainable

by the market environment, an eventuality that would mean that the

firm has no reason to exist. On the other hand, it is not supposed to

signify anything more than that; it is not a statement on whether the

price that the products fetch in the market and the quantity that the

firm sells are acceptable. Let us describe this condition as "the market

test."

Let us point out that all three conditions are genuinely "dynamic"

in the sense that each one of them constitutes a "process." Further-

more, the three processes are obviously interconnected; thus each

one of them affects the way the other two unfold in real time. For

example, if Condition 1 is not met, the firm will lose assets, which

will affect the coordination of its resources and, of course, the effi-

cacy with which it meets the market test. If Condition 2 is not met-

i.e., if the firm coordinates its resources poorly-its position in the

market for outputs will deteriorate and, with it, its ability to ensure

rents for its assets. Finally, if the firm performs badly in output

markets, this will affect both its ability to pay rents, as well as the

way its resources will be coordinated in the future.

How do the above relate to the equilibrium conceptualization

of the firm? To answer this question, we need to establish the exact

This content downloaded from

140.203.230.47 on Tue, 16 Nov 2021 21:06:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Hayek and a Theory of Economic Organization 553

conditions of the contractarian conceptualization. According to Foss

(1998:182-83), there are three such conditions:22 (1) an implicit

assumption that alternatives are given, thus depicting agents as having

to choose among a very clearly defined set of contractual alternatives;

(2) a suppression of process, which implies a view that the optimal

solution to the contract-design problem continues to be optimal

throughout contract execution; (3) a set of strong knowledge assump-

tions, thus leaving no room for theory to conceptualize the discov-

ery by agents of what was hitherto unimagined. Obviously, all three

problems have a special bearing on the concept of equilibrium, in

the standard neoclassical meaning of the term. The first abolishes

uncertainty; the second ensures the static nature of the analytical

framework; and the third rules out the possibility that agents may

behave entrepreneurially, in the Kirznerian sense.

By contrast, the conceptualization we have introduced avoids these

problems, thus transcending the equilibrium notion of the firm. Let

us see why. Our Condition 1 implies that the firm must strive to retain

its resources. Obviously this striving must really be understood as a

process, for the rents that must be paid to the members are not given

and known to the firm in any relevant sense, first, because they are

constantly affected by market developments-the competitive strug-

gle for resources by other firms-and second, because we have char-

acterized rents as subjective estimates, which may change as agents'

subjective expectations of opportunity rents change. Therefore, in

terms of Condition 1, the maintenance of the firm as an order depicts

a ceaseless process unfolding in real time in conditions of uncertainty

and, thus, creating the need for entrepreneurial discovery, even in

the simplest sense of trying to keep one step ahead of developments

in the markets for resources.

Our second condition calls for the coordination of resources within

the firm. Again, we have here a conception that avoids the problems

of the contractarian perspective that Foss points out. First, the fact

that the firm must coordinate its resources to achieve its purpose and,

more importantly, to coordinate the knowledge created in the process

of production means that the process of coordination itself constantly

creates novel situations that the firm must "learn" in order to be able

to coordinate successfully. This is the really complex problem that

This content downloaded from

140.203.230.47 on Tue, 16 Nov 2021 21:06:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

554 American Journal of Economics and Sociology

precludes a view of coordination as the optimal ex ante solution to

a principal-agent setup. Second, our Condition 2 describes a situation

where novelty-not only in the market but even within the firm

itself-is created and thus has to be discovered and exploited if coor-

dination is to be effective.

Finally, our third condition introduces entrepreneurship in output

markets as an essential factor for the existence of the firm. In the

dynamic perspective we are trying to develop, the firm's market per-

formance cannot but be entrepreneurial, for the simple reason that

the market is perceived as a process that creates novelty. In this

context, therefore, the idea that the firm has to choose among a clearly

defined and especially bounded set of alternatives cannot be sus-

tained. Moreover, our schema implies that profit opportunities are no

only "out there"-in the marketplace-for the firm to discover and

exploit, but are also to be found within the firm. They are created by

the learning processes set in motion by the firm's specific production

activities; thus, creating capabilities and the discovery of their poten-

tial is as an entrepreneurial a function as that of the discovery of

opportunities in the market proper.

The approach we are proposing here in order to conceptualize the

firm as an order rather than an equilibrium phenomenon is essen-

tially an "evolutionary" one in the sense that we referred to that strand

in the Introduction. The emphasis on entrepreneurship and, espe-

cially, on the internal capabilities of the firm as objects of entrepre-

neurial discovery establishes that change must be perceived as an

endogenous phenomenon, rather than as response to exogenous

shocks. On the other hand, the fact that the resources employed by

the firm are heterogeneous and yield multiple capabilities, that the

firm's success in coordinating them may be variable and that the firm's

behavior is itself entrepreneurial, in the sense of unpredictable on a

priori considerations, means that the operation of firms tends con-

stantly to produce a variety of characteristics. Finally, it is precisely

this variety of characteristics that forms the "pool" on which the selec-

tion process-i.e., the market test-operates.23

Let us sum up our discussion in this section. We have attempted

to construct a conceptualization of the firm as an order, rather than

as an equilibrium phenomenon. We have thus proposed a view of

This content downloaded from

140.203.230.47 on Tue, 16 Nov 2021 21:06:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Hayek and a Theory of Economic Organization 555

the firm as a set of interconnected processes. The analysis here has

been inspired by Hayek's distinction between spontaneous orders and

organizations and his insistence that the latter constitute a special class

of the general category of order. The relevance of this analysis for a

theory of the firm stems from the fact that it highlights such issues as

entrepreneurship, endogenous change, variety, and the importance

of the capabilities of the firm. On these grounds, a conception of the

firm based on Hayek's notion of order, signifying a process unfold-

ing in real time, leads to a view of the firm that differs significantly

from the static outlook of contractarian theories.

Rules, Commands, and Purposefil Direction

So FAR, OUR ARGUMENT has proceeded taking Hayek's distinction

between spontaneous orders and organizations-the former resting

on rules, the latter on commands-literally; i.e., our discussion of the

business firm has been compatible with a view of its essence merely

as a command structure. However, we have seen that Hayek admits

a role for rules in organizations, although he argues that the charac-

ter of these rules will have important differences from the rules that

lead to the formation of spontaneous orders. We now broaden the

analysis and introduce rules as an essential element for the running

of business firms.

The introduction of rules in organizations raises two distinct but

interrelated questions. The first concerns the reasons for this intro-

duction and the ways that it affects the nature of economic organi-

zation. The second, and perhaps more fundamental, question is

whether the introduction of rules blurs the distinction between spon-

taneous orders and organizations as proposed by Hayek. If the latter

is indeed the case, the question that naturally arises is whether

rule-following behavior within organizations may transform their

character into that of spontaneous orders.

We address these questions in turn. The necessity of rules in organ-

izations stems essentially from the same knowledge argument-we

could equally well interpret it as an ignorance argument-that per-

meates the whole of Hayek's social theory.24 If business firms were

This content downloaded from

140.203.230.47 on Tue, 16 Nov 2021 21:06:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

556 American Journal of Economics and Sociology

to be run on the basis of commands alone, the commanding author-

ity would have to concentrate the knowledge possessed by its

members in order to be able to come up with the most appropriate

specific command for every instance. Although such an operation is

not unthinkable in the context of small-scale business organizations,

it obviously becomes increasingly difficult as the firm grows both in

size and, especially, in complexity. It is not just the fact that the sheer

volume of knowledge with which the commanding authority would

have to cope would set limits to that growth. More importantly, a firm

operating on commands alone would lose the possibility to tap

two sources of knowledge: (a) the tacit knowledge possessed by its

human assets25 and (b) the discovery, again by the firm's human

assets, of new opportunities for more effective use of the firm's

resources. In other words, just as in the case of spontaneous orders,

rules in organizations promote the effective use of knowledge.

But while the introduction of rules increases the level of complex-

ity that the organization may attain, this complexity itself cannot but

affect the balance between rules and commands in a variety of ways.

To begin with, the more complex the organization becomes, the more

commands will tend to acquire a character of generality, thus blur-