Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Special Article: Twentieth Century Nutrition: Public Health Nutrition and Food Safety, 1900-1999

Special Article: Twentieth Century Nutrition: Public Health Nutrition and Food Safety, 1900-1999

Uploaded by

annisa syahfitriOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Special Article: Twentieth Century Nutrition: Public Health Nutrition and Food Safety, 1900-1999

Special Article: Twentieth Century Nutrition: Public Health Nutrition and Food Safety, 1900-1999

Uploaded by

annisa syahfitriCopyright:

Available Formats

Special Article: December 1999: 368-372

Twentieth Century Nutrition

Public Health Nutrition and Food Safety, 1900-1999

Editorial Note: Whatever your preference for terms such as to prevent goiter. The 1921-1929 Maternal and Infancy

“public nutrition, ” “internationalnutrition, ” or “public health Act enabled state health departments to employ nutri-

nutrition, ” there can be consensus that this century has wit- tionists and, during the 1930s, the federal government

nessed monumental achievements in public health through ap-

developed food relief and food commodity distribution

plication of advancing nutrition science. The enclosed selection

from a recent catalogue of these accomplishments, collected by programs, including school feeding and nutrition educa-

federal agencies, will be a useful citation of achievements and tion programs and national food consumption surveys.

challenges as the year 2000 approaches. At Nutrition Reviews, Pellagra is a good example of the translation of scien-

we intend to elaborate on many of these milestones in the coming tific understanding to public health action to prevent nu-

year as we havefor thepast half-century. Thispublication origi- trition deficiency.Pellagra, a classic dietary deficiency dis-

nally appeared in a slightly dzyerent form in the Morbidity and ease caused by insufficient niacin, was noted in the south-

Mortaliry WeeklyReport, October I S , 1999;48(40):905-13.

4

ern United States after the Civil War. Then considered

infectious, it was known as the disease of the four Ds:

Nutrition in Public Health

diarrhea, dermatitis, dementia, and death. The first out-

At the start of the century nutrition sciences were in their break was reported in 1907.In 1909,greater than 1000cases

infancy. Unknown was the concept that minerals and vita- were estimated to have occurred based on reports from 13

mins were necessary to prevent diseases caused by di- states. One year later, approximately3000 cases were sus-

etary deficiencies.Recurring nutrition deficiency diseases, pected nationwide based on estimates from 30 states and

including rickets, scurvy, beri-beri, and pellagra were the District of Columbia. By the end of 1911, pellagra had

thought to be infectious diseases. By 1900, biochemists been reported in all but nine states, and prevalence esti-

and physiologists had identified protein, fat, and carbo- mates had increased nearly n i n e f ~ l dDuring

.~ 1906-1940,

hydrates as the basic nutrients in food. By 1916 , new data approximately 3 million cases and approximately 100,000

led to the discovery that food contained vitamins, and the deaths were attributed to ~ e l l a g r aFrom

. ~ 1914 until his

lack of “vital amines” could cause disease. These scien- death in 1929,Joseph Goldberger,a Public Health Service

tific discoveries and the resulting public health policies, physician, conducted groundbreaking studies that dem-

such as food fortification programs, led to substantial re- onstrated that pellagra was not infectious but was associ-

ductions in nutrition deficiency diseases during the first ated with poverty and poor diet. Despite compelling evi-

half of the century. The focus of nutrition programs shifted dence, his hypothesis remained controversial and uncon-

in the second half of the century from disease prevention firmed until 1937. The near elimination ofpellagra by the

to control of chronic conditions, such as cardiovascular end of the 1940s(Figure 1) has been attributed to improved

disease and obesity. diet and health associated with economic recovery during

The discovery of essential nutrients and their roles in the 1940s and to the enrichment of flour with niacin. To-

disease prevention was instrumental in almost eliminating day, most physicians in the United States have never seen

nutrition deficiency diseases such as goiter, rickets, and pellagra although outbreaks continue to occur, particu-

pellagra in the United States. During 1922-1 927, with the larly among refugees and during emergencies in develop-

implementation of a statewide prevention program, the ing c o ~ n tr ie s. ~

goiter rate in Michigan fell from 38.6% to 9.0%.’ In 1921, The growth of publicly funded nutrition programs

rickets was considered the most common nutrition dis- was accelerated during the early 1940sbecause of reports

ease of children, affecting approximately 75% of infants in that 25% of draftees demonstrated evidence of past or

New York City? In the 1940s,the fortificationof milk with present malnutrition; a frequent cause of rejection from

vitamin D was a critical step in rickets control. military service was tooth decay or loss. In 1941, Presi-

Because of food restrictions and shortages during dent Franklin D. Roosevelt convened the National Nutri-

the First World War, scientific discoveriesin nutrition were tion Conference for Defense, which led to the first recom-

quickly translated into public health policy. For example, mended dietary allowances of nutrients and resulted in

in 1917, the United States Department of Agriculture issuance of War Order Number One, a program to enrich

(USDA) issued the first dietary recommendations based wheat flour with vitamins and iron. In 1998, the most re-

on five food groups and in 1924, iodine was added to salt cent food fortification program was initiated; folic acid, a

368 Nutrition Reviews@,Vol. 57, No. 12

1920 1925 1930 1935 1940 1945 1950 1955 1960

Year

Figure 1. Number of reported pellagra deaths, by sex of decedent and year-United States, 192C1960.

water-soluble vitamin, was added to cereal and grain prod- lar disease.

&

ucts to prevent neural tube defects. The most urgent challenge to nutrition health during

While the first half of the century was devoted to the 2 1 st century will be obesity. In the United States, with

preventing and controlling nutrition deficiency disease, an abundant, inexpensive food supply and a largely sed-

the focus of the second half has been on preventing entary population, overnutrition has become an impor-

chronic disease with initiation of the Framingham Heart tant contributor to morbidity and mortality in adults. AS

Study in 1949. This landmark study identified the contri- early as 1902, U_SDA’sW.O. Atwater linked dietary intake

bution of diet and sedentary lifestyles to the development to health, noting that “the evils of overeating may not be

of cardiovascular disease, and the effect of elevated se- felt at once, but sooner or later they are sure to appear-

rum cholesterol on the risk for coronary heart disease. perhaps in an excessive amount of fatty tissue, perhaps in

With increased awareness,public health nutrition programs general debility,perhaps in actual disease.”1° In U.S. adults,

sought strategies to improve diets. By the 197Os, food overweight (body mass index [BMI] of greater than or

and nutrition labeling and other consumer information equal to 25 kg/m2)and obesity (BMI greater than or equal

programs stimulated the development of products low in to 30 kg/m2)have increased markedly, especially since the

fat, saturated fat, and cholesterol. Since then, persons in 1970s.In the third National Health and Nutrition Examina-

the United States significantly decreased their dietary in- tion Survey (NHANES 111,1988-1 994), the crude preva-

takes of total fat fiom approximately 40% of total calorie lence of overweightfor adults age 20 and older was 54.9%.

intake in 1977-1978 to 33%in 1994-1996, approachingthe From 1976-1980(”ES 11)to 198fS1994 ( ” E S W ,

recommended 30%.6Intakes of saturated fat and levels of the prevalence of obesity increased fiom 14.5%to 22.5%.”

serum cholesterol also decreased.’ Prevention efforts, in- Overweight and obesity increase risk for and compli-

cluding changes in diet*and lifestyle and early detection cations of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, coro-

and improved treatment, contributed to impressive de- nary heart disease, osteoarthritis, and other chronic dis-

clines in mortality from heart disease and ~ t r o k e . ~ orders; total costs attributable to obesity are an estimated

Populations with diets rich in fruits and vegetables $100 billion annually.12 Obesity is a growing problem in

have a substantially lower risk for many types of cancer. developing countries where it is associated with substan-

In 199 1, the National Cancer Institute and the Produce for tial morbidity and where malnutrition, particularly defi-

Better Health Foundation launched a program to encour- ciencies of iron, iodine, and vitamin A, affects approxi-

age consumption of at least five servings of fruits and mately 2 billion people. Increasing physical activity in the

vegetables daily. Although public awareness of the “5 A U.S. population is an important step,” but effective pre-

Day” message did increase, only approximately 36% of vention and control of overweight and obesity will re-

persons ages two and older in the United States achieved quire concerted public health action.

the daily goal of five or more servings of h i t s and veg-

etables.EA diet rich in fruits and vegetables that provides Food Safety

vitamins, antioxidants (including carotenoids), other

phytochemicals, and fiber is associated with additional During the early 20th century, contaminated food, milk,

health benefits, including decreased risk for cardiovascu- and water caused many foodborne infections, including

Nutrition Reviews”, Vol. 57, No. 12 369

typhoid fever, tuberculosis, botulism, and scarlet fever. In

1906, Upton Sinclair described in his novel The Jungle the

unwholesome working environment in the Chicago

meatpacking industry and the unsanitary conditions un-

der which food was produced. Public awareness dramati-

cally increased and led to the passage of the Pure Food

and Drug Act.I4 Once the sources and characteristics of

foodborne diseases were identified-long before vaccines

or antibiotics-they could be controlled by handwashing,

sanitation, refrigeration, pasteurization, and pesticide ap- 1920 1930 1940 1950 1980

Year

plication.

Figure 2. Incidence per 100,000 population oftyphoid fever, by

Healthier animal care, feeding, and processing also yea-United States, 192&1960.

improved food supply safety. In 1900, the incidence of

typhoid fever was approximately 100 per 100,000people;

by 1920, it had decreased to 33.8, and by 1950,to 1.7 (Fig- labeled products. During the 1950s and 1960s, pesticide

ure 2). During the 194Os, studies of autopsied muscle regulation evolved to establish maximum allowable resif

samples showed that 16% of persons in the United States due levels of pesticides on foods and to deny registra-

had trichinellosis; 3 0 0 4 0 0 cases were diagnosed every tions for unsafe or ineffective products. During the 197Os,

year, and 10-20 deaths occurred.I5Since then, the rate of acting under these strengthened laws, the newly formed

infection has declined markedly; from 1991 through 1996, Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) removed DDT

three deaths and an average of 38 cases per yet' were and several other highly persistent pesticides from the

reported.I6 marketplace. In 1996, the Food Quality Protection Act set

Perishable foods contain nutrients that pathogenic a stricter safety standard and required the review of older

microorganisms require to reproduce. Bacteria such as allowable residue levels to determine whether they were

Salmonella sp., Clostridium sp., and Staphylococcus sp. safe. In 1999, federal and state laws required that pesti-

can multiply quickly to sufficient numbers to cause ill- cides meet specific safety standards; the EPA reviews and

ness. Prompt refrigeration slows bacterial growth and registers each product before it can be used and sets lev-

keeps food fresh and edible. els and restrictions on each product intended for food or

At the turn of the 20th century, consumers kept food feed crops.

fresh by placing it on a block of ice or, in cold weather, Newly recognized foodborne pathogens emerged in

burying it in the yard or storing it on a windowsill outside. the United States since the late 1970s; contributing fac-

During the 1920s,refrigerators with freezer compartments tors include changes in agricultural practices and food

became available for household use. Another process that processing operations and the globalization of the food

reduced the incidence of disease was invented by Louis supply (Table 1). Seemingly healthy food animals can be

Pasteur: pasteurization. Although the process was applied reservoirs of human pathogens. During the 1980s, for ex-

first in wine preservation, when milk producers adopted ample, an epidemic of egg-associated Salmonella sero-

the process, pasteurization eliminated a substantial vec- type Enteritidis infection spread to an estimated 45% of

tor of foodborne disease. In 1924, the Public Health Ser- the nation's egg-laying flocks, which resulted in a large

vice created a document to assist Alabama in developing increase in egg-associated foodborne illness within the

a statewide milk sanitation program. This document United state^.'^.^^ Escherichia coli 0 157:H7, which can

evolved into the Grade A Pasteurized Milk Ordinance, a cause severe infections and death in humans, produces

voluntary agreement that established uniform sanitation no signs of illness in its nonhuman hosts.21In 1993, a

standards for the interstate shipment of Grade A milk and severe outbreak of E. coli 0157:H7 infections attributed

now serves as the basis of milk safety laws in the 50 states to consumption of undercooked ground beepZresulted in

and Puerto R i ~ 0 . l ~ 50 1 cases of illness, 151 hospitalizations,and three deaths,

Along with improved crop varieties, insecticides and and led to a restructuring of the meat inspection process.

herbicides have increased crop yields, decreased food The most common foodborne infectious agent may be the

costs, and enhanced the appearance of food. Without calicivirus (a Norwalk-like virus), which can pass fiom the

proper controls, however, the residues of some pesticides unwashed hands of an infected foodhandler to the meal

that remain on foods can create potential health risks.'* of a consumer. Animal husbandry and meat production

Before 1910, no legislation existed to ensure the safety of improvements that contributed to reducing pathogens in

food and feed crops that were sprayed and dusted with the food supply include pathogen eradication campaigns,

pesticides. In 1910, the first pesticide legislation was de- the Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point (HACCP)

signed to protect consumers from impure or improperly programs,Z3better animal feeding regulation^,^^ the use of

370 Nutrition Reviews", Vol. 57, No. 12

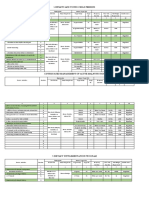

Table 1. Newly RecognizedPathogens Identified As tigations, the public health system can rapidly identifir

Predominantly Foodborne and control outbreaks. The Food and Drug Administra-

Campylobacter coli tion, CDC, USDA, other federal agencies, and private or-

Campylobacterjejuni ganizations are enhancing food safety by collaborating in

Campylobacterfetus ssp. fetus education, training, research, technology, and transfer of

Cvptosporidium parvum

Cyclospora cayetanensis information and by considering food safety as a whole-

Escherichia coli 0 157:H7 and related E. coli (e.g., from farm to table.

0111:NMand0104:H21)

Listeria monocytogenes Demographicsand Public Health Nutrition

Norwalk-like viruses

Nitschia pungens (cause of amnesic shellfish poisoning) As the U.S. population ages, attention to both nutrition

Salmonella serotype Enteritidis and food safety will become increasingly important. Chal-

Salmonella serotype TyphimuriumDT 104

Vibrio cholerae Non-01 lenges will include maintaining and improving nutrition

Vibrio vulnificus status, because nutrient needs change with aging, and

Vibrio parahaemolyticus assuring food quality and safety, which is important to an

Yersinia enterocolitica older, more vulnerable population. Continuing challenges

for public health action include reducing iron deficiency,

uncontaminated water in food p r o c e s ~ i n gmore

, ~ ~ effec- especially in infants, young children, and women of child-

tive food preservatives,26improved antimicrobial prod- bearing age; improving initiation and duration of

ucts for sanitizing food processing equipment and facili- breastfeeding; improving folate status for women of child-

ties, and adequate surveillanceof foodhandling and prepa- bearing age; and applying emerging knowledge about

ration methods.27HACCP programs also are mandatory nutrition on dietary patterns and behavior that promote

for the seafood industry.28 health and reduce risk for chronic disease. Behavioral re-

Improved surveillance, applied research, and outbreak search indicates that successful nutrition promotion ac-

investigations elucidated the mechanisms of contamina- tivities focus on specific behaviors, have a strong con-

tion that are leading to new control measures for foodborne sumer orientatian, segment and target consumers, use

pathogens. In meat-processing the incidence of multiple reinforcing channels, and continually refine the

Salmonella and Campylobacter infections has decreased. messages.34These techniques form a paradigm to achieve

In 1998, however, apparently unrelated cases of Listeria public health goals and to communicate and motivate con-

infections were linked when an epidemiologic investiga- sumers to change their behavior.

tion indicated that isolates from all cases shared the same

genetic DNA fingerprint; approximately 100 cases and 22 Reported by: Environmental Protection Agency; United

deaths were traced to eating hot dogs and deli meats pro- States Department ofAgriculture; Center for Food Safety

duced in a single manufacturingplant?O In 1998,a multistate and Applied Nutrition, Food and Drug Administration;

outbreak of shigellosis was traced to imported parsley.” Division of Nutrition Research Coordination,National In-

During 1997-1998 in the United States, outbreaks of stitutes of Health; National Center for Health Statistics,

cyclosporiasis were associated with mesclun mix lettuce, National Center for Environmental Health, National Cen-

basil and basil-containingproducts, and Guatemalan rasp- ter for Infectious Diseases, National Center for Chronic

berries.32These instances highlight the need for measures Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC.

that prevent food contamination closer to its point of pro-

duction, particularly if the food is eaten raw or is difficult 1. Langer PL. History of goitre. In: Endemic goitre.

Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization,

to wash.33 1960;9-25(WHO Monograph Series No 44)

Any 2 1st century improvementwill be accelerated by 2. Hess AF. Newer aspects of some nutritional disor-

new diagnostic techniques and the rapid exchange of in- ders. JAMA 1921;76:693-700

formation through use of electronic networks and the 3. Lanska DJ. Stages in the recognition of epidemic

Internet. PulseNet, for example, is a network of laborato- pellagra in the United States: 1865-1 960. Neurol-

ogy 1996;47:829-34

ries in state health departments, Centers for Disease Con-

4. Bollet AJ. Politics and pellagra: the epidemic of

trol and Prevention (CDC), and food regulatory agencies. pellagra in the US in the early twentieth century.

In this network, the genetic DNA fingerprints of specific Yale J Biol Med 1992;65:211-21

pathogens can be identified and shared electronically 5. Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Outbreak of

among laboratories, enhancing the ability to detect, in- pellagra among Mozambican refugees-Malawi,

vestigate, and control geographically distant, yet related, 1990. MMWR 1991;40:209-13

6. Tippett KS,Cleveland LE. How current diets stack

outbreaks.Another example of technology is DPDx, a com- up: comparison with dietary guidelines. In: Frazao

puter network that identifies parasitic pathogens. By com- E, ed. America’s eating habits: changes and con-

bining PulseNet and DPDx with field epidemiologic inves- sequences (Agricultural Information Bulletin No

Nutrition Reviews”, Vol. 57, No. 12 371

750). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agricul- teritidis in humans and animals: epidemiology,

ture, Economic Research Service, Food and Rural pathogenesis and control. Ames, IA: Iowa State

Economics Division, 1999;51-70 University Press, 1999;341-52

7 Ernst ND, Sempos ST, Briefel RR, Clark MB. Con- 21. Griffin PM. Epidemiology of shiga toxin-producing

sistency between US dietary fat intake and serum Escherichia coli infections in humans in the United

total cholesterol concentrations:the National Health States. In: Kaper JB, O'Brien AD, eds. Escherichia

and Nutrition Examination surveys. Am J Clin Nutr coli 0157:H7 and other Shiga-toxin producing E.

1997; 66(sup p I) :965s-72s coli strains. Washington, DC: American Society for

8. Crane NT, Hubbard VS, Lewis CJ. American diets Microbiology, 1998;15-22

and year 2000 goals. In: U.S. Department of Agri- 22. Bell BI? Goldoft M, Griffin PM, et al. A multistate

culture. America's eating habits: changes and con- outbreak of Escherichia coli 0 157:H7-associated

sequences. Washington, DC: US. Department of bloody diarrhea and hemolytic uremic syndrome

Agriculture, Economic Research Service, Food and from hamburgers: the Washington experience.

Rural Economics Division, 1999;111-32(AgricuI- JAMA 1994;272:1349-53

tural Information Bulletin No 750) 23. Amendment to the Federal Meat InspectionAct and

9. CDC. Decline in deaths from heart disease and the Poultry Products Inspection Act to Ensure the

stroke-United States, 1900-1 999. MMWR 1999; Safety of Imported Meat and Poultry Products. .I

48: 649-56 Ensuring the Safety of Imported Meat and Poultry

10. Atwater WO. Foods: nutritivevalue and cost. Wash- Act of 1999. H.R. 2581, July 21, 1999

ington, DC: US. Department of Agriculture, 1894 24. CDC. Trichinella spiralis infection-United States,

(Farmers' Bulletin No 23) 1990. MMWR 1991;40:35

11. Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kuczmarski RJ, Johnson 25. CDC. Outbreaks of cyclosporiasis-United States

CL. Overweight and obesity in the United States: and Canada, 1997. MMWR 1997;46:521

prevalence and trends, 1960-1994. Int J Qbesity 26. Binkerd EF, Kolari OE. The history and use of ni-

1998;22:39-47 trate and nitrite in the curing of meat. Food & Cos-

12. Wolf AM, Colditz GA. Current estimates of the eco- metics Toxicology 1975;13:655-61

nomic cost of obesity in the United States: whither? 27. CDC. Multistate surveillance for food handling,

Obesity Res 1998;6:97-106 preparation, and consumption. MMWR 1998;47

13. CDC. Physical activity and health: a report of the (SS-4):33-57

Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US. Department of 28. Shapiro RL, Altekruse S, Hutwagner L, et al. The

Health and Human Services, CDC, 1996. role of Gulf Coast oysters harvested in warmer

14. Young JH. Pure food: securing the Federal Food months in Vibrio vulnificus infections in the United

and Drugs Act of 1906. Princeton, NJ: Princeton States, 1988-1996. J Infect Dis 1998;178:752-9

University Press, 1989 29. CDC. Incidence of foodborne illnesses: preliminary

15. Schantz PM. Trichinosis in the United States- data from the Foodborne Disease Active Surveil-

1947-1 981. Food Techno1 1983;37:83-6 lance Network (FoodNet)-United States, 1998.

16. Moorhead A. Trichinellosis in the United States, MMWR 1999;48:189-94

1991-1 996: declining but not gone. Am J Trop Med 30. CDC. Update: multistate outbreak of listeriosis-

Hyg 1999;60:66-9 United States, 1998-1999. MMWR 1999;47:1117-

17. Public Health Service. 1924 United States Pro- 8

posed Standard Milk Ordinance. Public Health 31. CDC. Outbreaks of Shigella sonnei infection asso-

Reports, Washington, DC: Public Health Service, ciated with eating fresh parsley-United States and

November 7, 1924. Canada, July-August, 1998. MMWR 1999;48:285-

18. Fan AM, Jackson RJ. Pesticides and food safety. 9

Regulatory Toxicology & Pharmacology. 1989;9: 32. Herwaldt BL, Ackers ML, Cyclospora Working

158-74 Group. An outbreak in 1996 of cyclosporiasis as-

19. St. Louis ME, Morse DL, Potter ME, et al. The emer- sociated with imported raspberries. N Engl J Med

gence of grade A eggs as a major source of Salmo- 1997;336:1548-56

nella enteritidis infections: new implications for the 33. Osterholm MT, Potter ME. Irradiation pasteuriza-

control of salmonellosis. JAMA 1988;259:2103-7 tion of solid foods: taking food safety to the next

20. Ebel ED, Hogue AT, Schlosser WD. Prevalence of level. Emerging Infectious Diseases 1997;3:575-

Salmonella enterica serovar enteritidis in unpas- 7

teurized liquid eggs and aged laying hens at 34. Contento I, Balch GI, Bronner YL, et al. The effec-

slaughter: implications on epidemiology and con- tiveness of nutrition education and implications for

trol of the disease. In: Saeed AM, Gast RK, Potter nutrition education policy, programs and research:

ME, Wall PG, eds. Salmonella enterica serovar en- a review of research. J Nutr Edu 1995;27:279-83

372 Nutrition Reviews", Vol. 57, No. 12

You might also like

- FortifiedFunctional Packaged Food in VietnamDocument12 pagesFortifiedFunctional Packaged Food in VietnamCuongNo ratings yet

- Mozaffarian D 2018 History of Modern Nutrition ScienceDocument6 pagesMozaffarian D 2018 History of Modern Nutrition ScienceLee EstoqueNo ratings yet

- Morden NutritionDocument6 pagesMorden NutritionTan Hau Vo100% (1)

- History of NutrDocument6 pagesHistory of Nutrlaura gomezNo ratings yet

- Obesity and The Modern LifestyleDocument5 pagesObesity and The Modern LifestyleFabio MorenoNo ratings yet

- MalnutritionDocument27 pagesMalnutritionOviya DharshiniNo ratings yet

- Historical Milestone in NutritionDocument4 pagesHistorical Milestone in NutritionRussel Kate SulangNo ratings yet

- FGKFD NewDocument18 pagesFGKFD Newharshit03022004No ratings yet

- The ABCs of VitaminsDocument3 pagesThe ABCs of VitaminsAnonymous 2rNFWzNo ratings yet

- Nutrition, Physiological Capital and Economic GrowthDocument32 pagesNutrition, Physiological Capital and Economic GrowthAlejandro Martinez EspinosaNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Malnutrition - AmritaDocument4 pagesResearch Paper On Malnutrition - Amritaapi-341211173100% (6)

- Health Economics Week 1 Lesson 3Document8 pagesHealth Economics Week 1 Lesson 3Kpop n DramaNo ratings yet

- Obesity: Body Mass Index (BMI) Waist-Hip Ratio Percentage Body FatDocument6 pagesObesity: Body Mass Index (BMI) Waist-Hip Ratio Percentage Body FatRichmond AmuraoNo ratings yet

- Malnutrition: A Secular Challenge To Child Nutrition: Review ArticleDocument13 pagesMalnutrition: A Secular Challenge To Child Nutrition: Review ArticleAdi ParamarthaNo ratings yet

- Group 3Document13 pagesGroup 3Ayuhmi MarquezNo ratings yet

- Methodology of Nutritional SurveyDocument11 pagesMethodology of Nutritional SurveyАмар ЭрдэнэцогтNo ratings yet

- The Potential Impact of Reducing Global Malnutrition On Poverty Reduction and Economic DevelopmentDocument29 pagesThe Potential Impact of Reducing Global Malnutrition On Poverty Reduction and Economic DevelopmentWulan CerankNo ratings yet

- Solving Population-Wide Obesity - Progress and Future ProspectsDocument4 pagesSolving Population-Wide Obesity - Progress and Future ProspectsOumaima Ahaddouch ChiniNo ratings yet

- Agriculture and Nutrition ArticleDocument8 pagesAgriculture and Nutrition ArticleYekhetheloNo ratings yet

- Poverty and Malnutrition-1Document3 pagesPoverty and Malnutrition-1Dane PukhomaiNo ratings yet

- Covid-19 and The Right To Thrive ResilienceDocument2 pagesCovid-19 and The Right To Thrive ResilienceMaria Lourdes VelardeNo ratings yet

- Food and Nutrition in EmergencyDocument44 pagesFood and Nutrition in EmergencyStefania WidyaNo ratings yet

- Nestle On PaleodietDocument8 pagesNestle On PaleodietdrjeckyNo ratings yet

- Inquiry On Socio Political ProblemsDocument25 pagesInquiry On Socio Political ProblemsLara Mae AguilarNo ratings yet

- Food SecurityDocument15 pagesFood SecurityLYKA JOY CABAYUNo ratings yet

- Introduction Large-Scale Fortification, An ImportantDocument5 pagesIntroduction Large-Scale Fortification, An ImportantMuhitAbirNo ratings yet

- Global Food SecurityDocument14 pagesGlobal Food SecurityJohn MajanNo ratings yet

- Rift Valley University Department of General Public HealthDocument11 pagesRift Valley University Department of General Public HealthKedir DayuNo ratings yet

- New Concepts of A Balanced Diet: by JamesDocument3 pagesNew Concepts of A Balanced Diet: by JamesVivekananthan NwbNo ratings yet

- Malnutrition Refers ToDocument2 pagesMalnutrition Refers Tor97756598No ratings yet

- NutriMedical PharmaceuticalDocument4 pagesNutriMedical PharmaceuticalNutriMedical.gr PharmaceuticalNo ratings yet

- Hunt JurnalDocument29 pagesHunt JurnalLily NGNo ratings yet

- The Food Guide Pyramid: Will The Defects Be Corrected?: Alice Ottoboni, Ph.D. Fred Ottoboni, M.P.H., PH.DDocument5 pagesThe Food Guide Pyramid: Will The Defects Be Corrected?: Alice Ottoboni, Ph.D. Fred Ottoboni, M.P.H., PH.DJhonatan VélezNo ratings yet

- Importance of NutritionDocument14 pagesImportance of NutritionCristina AdolfoNo ratings yet

- Infections and Immunity: A Week On The Concord and Merrimuck RiversDocument24 pagesInfections and Immunity: A Week On The Concord and Merrimuck RiversRatna Nanaradi CullenNo ratings yet

- The COVID-19 Nutrition Crisis:: What To Expect and How To ProtectDocument4 pagesThe COVID-19 Nutrition Crisis:: What To Expect and How To Protectvipin kumarNo ratings yet

- Glossary: Public Health HistoryDocument2 pagesGlossary: Public Health Historyujangketul62No ratings yet

- Excerpt: "The Information Diet A Case For Conscious Consumption," by Clay JohnsonDocument9 pagesExcerpt: "The Information Diet A Case For Conscious Consumption," by Clay Johnsonwamu885No ratings yet

- The Soft Science of Dietary Fat: Science 30 March 2001: Vol. 291 No. 5513 Pp. 2536-2545Document14 pagesThe Soft Science of Dietary Fat: Science 30 March 2001: Vol. 291 No. 5513 Pp. 2536-2545Luiz PauloNo ratings yet

- 06 Eknoyan History Obesity..Document7 pages06 Eknoyan History Obesity..Alejandro Martinez EspinosaNo ratings yet

- Global Food SecurityDocument21 pagesGlobal Food SecurityFelipe RamonNo ratings yet

- Human Health and Nutrition: How Isotopes Are Helping To Overcome"hidden Hunger"Document10 pagesHuman Health and Nutrition: How Isotopes Are Helping To Overcome"hidden Hunger"Irish zyrene RocilNo ratings yet

- Vol. I43: Carbohydrates and NutritionDocument7 pagesVol. I43: Carbohydrates and NutritionNurmaNo ratings yet

- ASSIGNMENT Reading ComprehensionDocument5 pagesASSIGNMENT Reading ComprehensionSILVIA AMANDA ZAHRA 1No ratings yet

- Reviews: Global Obesity: Trends, Risk Factors and Policy ImplicationsDocument15 pagesReviews: Global Obesity: Trends, Risk Factors and Policy ImplicationsAlejandro BarrazaNo ratings yet

- What Are The Major Food and Nutrition Challenges Impacting Human and Environmental Health?Document2 pagesWhat Are The Major Food and Nutrition Challenges Impacting Human and Environmental Health?Alejandra ZelaNo ratings yet

- Vegeterian NutritionDocument37 pagesVegeterian NutritionIva BožićNo ratings yet

- Contemporary World FinalsDocument2 pagesContemporary World FinalsdharylleaaronNo ratings yet

- Obesity in America - A Paradigm ShiftDocument11 pagesObesity in America - A Paradigm Shiftapi-253633649No ratings yet

- Phillipines IDDDocument9 pagesPhillipines IDDsuluteroNo ratings yet

- Review: Recognition of The Challenge of DiabetesDocument9 pagesReview: Recognition of The Challenge of DiabetesJulia OlanNo ratings yet

- Mortality DeclineDocument13 pagesMortality DeclineKathrina GabrielNo ratings yet

- History of Nutrition (ppt.2)Document47 pagesHistory of Nutrition (ppt.2)Ricamae BalmesNo ratings yet

- The Three Way StreetDocument5 pagesThe Three Way Streetapi-27071967No ratings yet

- Objective 1 FULLDocument8 pagesObjective 1 FULLPartnerCoNo ratings yet

- Food, Genes, and Culture: Eating Right for Your OriginsFrom EverandFood, Genes, and Culture: Eating Right for Your OriginsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- Food Processing A Century of ChangeDocument17 pagesFood Processing A Century of Changemidimaia1002No ratings yet

- Food Fortification Today PDFDocument9 pagesFood Fortification Today PDFmphil.rameshNo ratings yet

- Impact of Nutrition On Health and Healthy LivingDocument5 pagesImpact of Nutrition On Health and Healthy LivingOyedotun TundeNo ratings yet

- Essay EssayDocument8 pagesEssay Essayapi-302389464No ratings yet

- Contoh Artikel RevieDocument11 pagesContoh Artikel RevieGharyn Adzkia BudimanNo ratings yet

- Food For Calcium & VitaminsDocument2 pagesFood For Calcium & Vitaminsjit_gosaiNo ratings yet

- My Plate For The Day-20-12-2022Document4 pagesMy Plate For The Day-20-12-2022Vijay KumarNo ratings yet

- Resolution - Adopting Food Fortification ActDocument2 pagesResolution - Adopting Food Fortification ActMelvz BallesterosNo ratings yet

- Rice Technical HandbookDocument24 pagesRice Technical HandbookgavirneniNo ratings yet

- Micronutrient Survey 2019-20Document116 pagesMicronutrient Survey 2019-20Tareq HasanNo ratings yet

- 1.infants and Young Child FeedingDocument21 pages1.infants and Young Child FeedingAnn Jelaine NovenoNo ratings yet

- Fortifications in Ice-Cream With Enhanced FunctionDocument9 pagesFortifications in Ice-Cream With Enhanced FunctionRosalin nathNo ratings yet

- Nutri QuizDocument10 pagesNutri QuizDarvin Riel OnahonNo ratings yet

- Vitamin A Stability in Nigerian Wheat Flour PDFDocument8 pagesVitamin A Stability in Nigerian Wheat Flour PDFMalak BattahNo ratings yet

- Folic AcidDocument13 pagesFolic Acidzhelle2No ratings yet

- URC SR 2016 Products Pp76-101 HiRes DigitalDocument26 pagesURC SR 2016 Products Pp76-101 HiRes DigitalDark ShadowNo ratings yet

- Folic Acid in PregnancyDocument3 pagesFolic Acid in PregnancybdianNo ratings yet

- Vitamins Report Usda 2015 PDFDocument35 pagesVitamins Report Usda 2015 PDFsahtehesabmNo ratings yet

- Current Topics in Anemia PDFDocument260 pagesCurrent Topics in Anemia PDFrukman kiswari0% (1)

- Food Processing BackgroundDocument9 pagesFood Processing Backgroundthe dark knightNo ratings yet

- Chapter 11 - Nutrition Through The Life Span: Pregnancy and LactationDocument12 pagesChapter 11 - Nutrition Through The Life Span: Pregnancy and LactationMario MagtakaNo ratings yet

- Afghanistan Market (Altai Consulting) PDFDocument95 pagesAfghanistan Market (Altai Consulting) PDFMalik Mussadique100% (1)

- BBAG2 - English Mid Q1Document3 pagesBBAG2 - English Mid Q1Jenessa BarrogaNo ratings yet

- DOH Programs EEINC Newborn Screening BEmONC CEmONC NutritionDocument46 pagesDOH Programs EEINC Newborn Screening BEmONC CEmONC NutritionKRISTINE ANGELIE PANESNo ratings yet

- Loss of Vitamin A During CookingDocument6 pagesLoss of Vitamin A During CookingNusrat ShaheenNo ratings yet

- Enhancement of Nutritional and Functional Characteristics of Noodles by Fortification With Protein and Fiber: A ReviewDocument7 pagesEnhancement of Nutritional and Functional Characteristics of Noodles by Fortification With Protein and Fiber: A ReviewLITTLE ANGELNo ratings yet

- Nutrition AssignmentDocument2 pagesNutrition AssignmentRoy MutahiNo ratings yet

- Food Fortification in India: Enriching Foods, Enriching LivesDocument18 pagesFood Fortification in India: Enriching Foods, Enriching LivesSagar SharmaNo ratings yet

- D Symposium - Vitamin D Insufficiency - CALVO, WHITINGDocument3 pagesD Symposium - Vitamin D Insufficiency - CALVO, WHITINGytreffalNo ratings yet

- Nutrition of Adolescent Girls in Low and Middle Income CountriesDocument12 pagesNutrition of Adolescent Girls in Low and Middle Income CountriesmanalNo ratings yet

- Micronutrient Fortification of FoodDocument51 pagesMicronutrient Fortification of FoodKalpesh RathodNo ratings yet

- PDRI TablesDocument7 pagesPDRI TablesCamille Chen100% (1)