Professional Documents

Culture Documents

11nassaji 2003 L2 Vocabulary

11nassaji 2003 L2 Vocabulary

Uploaded by

lenebenderOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

11nassaji 2003 L2 Vocabulary

11nassaji 2003 L2 Vocabulary

Uploaded by

lenebenderCopyright:

Available Formats

L2 Vocabulary Learning From Context:

Strategies, Knowledge Sources, and

Their Relationship With Success in

L2 Lexical Inferencing

HOSSEIN NASSAJI

University of Victoria

Victoria, British Columbia, Canada

This study examines the use of strategies and knowledge sources in L2

lexical inferencing and their relationship with inferential success. Data

consist of introspective and retrospective think-aloud protocols of 21

intermediate ESL learners who attempted to infer new word meanings

from context. Analysis reveals that (a) overall, the rate of success was

low even when learners used the strategies and knowledge sources they

had at their disposal, (b) different strategies contributed differentially

to inferencing success, and (c) success was related more to the quality

rather than the quantity of the strategies used. Findings challenge a

unidimensional conception of the role of strategies in L2 lexical

inferencing and instead support an inferencing model that distin-

guishes between strategies and the ability to use them appropriately and

effectively in conjunction with various sources of knowledge in lexical

inferencing. This article discusses the pedagogical as well as theoretical

implications of the ndings for an integrated model of lexical

inferencing.

M any ESOL teachers assume that an important process in learning

new vocabulary is the inference learners make about word mean-

ing when they encounter an unknown word in a text. Indeed, compel-

ling evidence suggests that L1 learners acquire much of their vocabulary

from inferring from context on the basis of multiple clues that might be

available to them. L2 learners’ lexical inferencing and its link with

vocabulary acquisition is not as well understood and therefore has

recently become the focus of much research (de Bot, Paribakht, &

Wesche, 1997; Dubin & Olshtain, 1993; Fraser, 1999; Haynes, 1993; Joe,

1995; Lewis, 1993; Morrison, 1996; Nation, 1990; Paribakht & Wesche,

1999; Parry, 1993; Prince, 1996). In L2 learning, much of this research

TESOL QUARTERLY Vol. 37, No. 4, Winter 2003 645

has failed to provide strong evidence; therefore, L2 professionals need

more information about this potentially important process if they are to

make good decisions about vocabulary teaching. This study examines the

success of intermediate ESL learners’ inferencing when they come across

unknown words in a written text. Through the use of think-aloud

protocols, I obtained evidence about the strategies and knowledge

sources learners rely on during the inferencing process. Knowledge

about these mechanisms helps in developing a theory of L2 vocabulary

learning from context as well as an effective and ef cient approach to

teaching and learning vocabulary in L2 classrooms.

L2 LEARNERS’ LEXICAL INFERENCING

Although evidence from L1 research suggests that L1 learners learn

much of their vocabulary from context, the results of L2 research in this

area are inconclusive. There is uncertainty among L2 researchers

regarding the role of lexical inferencing as an ef cient L2 vocabulary

learning strategy (Bensoussan & Laufer, 1984; Carter & McCarthy, 1988;

Haynes, 1993; Hulstijn, 1992; Scherfer, 1993). However, many research-

ers would agree that, if successful, inferencing can aid comprehension

and contribute to, if not lead to, immediate learning and retention of

lexical and semantic information about words (Ellis, 1997; Hulstijn,

1992; Paribakht & Wesche, 1999). Yet little is known about the exact

mechanisms underlying successful inferencing and, in particular, how

different strategies and knowledge sources used to infer word meanings

from context relate to ultimate success in lexical inferencing.

Inferencing Strategies in Reading

L2 reading comprehension processes are heavily in uenced by the

ef ciency of the lower level textual process (Nassaji, 2002, 2003).

Evidence from studies on L2 reading comprehension suggests that

encountering many unknown words in a text may negatively in uence

the reading comprehension of L2 readers. Unknown words may also

partly account for the observation that L2 readers read texts word by

word (e.g., Bernhardt, 1991; Bernhardt & Kamil, 1995; Carrell, 1988;

Clarke, 1980). Skilled L2 readers, on the other hand, due to their skills in

lower level word identi cation processes and higher level syntactic and

semantic processes, can read and understand the text more ef ciently

than unskilled L2 readers (Nassaji, 2003). In addition, research investi-

gating more speci c causes suggests that L2 readers are also weaker in

using effective strategies in reading and dealing with new words than are

646 TESOL QUARTERLY

L1 readers (e.g., Auerbach & Paxton, 1997; Block, 1992; Carrell, 1988;

Devine, 1993; Hudson, 1982; Kern, 1989). Thus, the type of strategies L2

learners use may be related to their ability to comprehend and infer

words successfully from context.

Research suggests that readers use a variety of strategies when they

encounter new words. These strategies include ignoring unknown words,

consulting a dictionary for their meaning, writing them down for further

consultation with a teacher, or attempting to infer their meaning from

context (Fraser, 1999; Harley & Hart, 2000; Sanaoui, 1995). Among

various word-learning strategies, lexical inferencing has been found to

be the strategy most widely used by L2 learners, a process that “involves

making informed guesses as to the meaning of an utterance in light of all

available linguistic cues in combination with the learner’s general

knowledge of the world, her awareness of context and her relevant

linguistic knowledge” (Haastrup, 1991, p. 40).

Fraser (1999) and Paribakht and Wesche (1999) found that lexical

inferencing was the most frequent and preferred strategy their adult L2

learners used to learn the meanings of new words when reading. Fraser

found that lexical inferencing alone accounted for 58% of the cases

where learners encountered a new word. Other strategies were used at a

lower percentage: consulting a dictionary (39%), ignoring (32%), and

not paying attention to the word (3%). Paribakht and Wesche found that

almost 80% of the strategies their university ESL students used in dealing

with new words were lexical inferencing, with all other strategies ac-

counting for about 20% of the learner’s strategy use. Inferencing has also

been reported to be the major processing strategy when learners attempt

to derive and learn idiomatic and gurative meanings in reading.

Cooper (1999) found that 28% of the time, readers used inferring from

context as a strategy to identify the meaning of idioms. This percentage

was higher than that of all other strategies, including analyzing the idiom

(24%), using literal meaning (19%), requesting information (8%),

paraphrasing and repeating (7%), using background knowledge (7%),

and using L1 or other strategies (7%). In view of the dominance of this

strategy in L2 reading, its value for lexical acquisition for ESOL should

be further investigated.

Successful Vocabulary Inferencing

Studies investigating what is involved in inferencing have identi ed

many factors that play an important role in successful inferencing. These

factors include the nature of the word and the text that contains the

word (Paribakht & Wesche, 1999; Parry, 1993), the kind of information

available in the text (Chern, 1993; Haastrup, 1991; Haynes, 1993), the

L2 VOCABULARY LEARNING FROM CONTEXT 647

importance of the word to the comprehension of the text (Brown, 1993),

the degree of cognitive and mental effort involved in the task (de Bot

et al., 1997; Fraser, 1999; Joe, 1995), and the degree of textual informa-

tion available in the surrounding context (Dubin & Olshtain, 1993).

Successful inferencing has been shown to depend heavily on learners’

prior knowledge as well as their ability to make effective use of extratextual

cues (de Bot et al., 1997; Haastrup, 1991). It also has been shown to

depend on learners’ having large vocabulary recognition knowledge, for

example, of around 5,000 word families (Coady, Magoto, Hubbard,

Graney, & Mokhtari, 1993; Laufer, 1997), and their ability to compre-

hend most of the words, at least 95%, in the text (Hirsh & Nation, 1992;

Laufer, 1988, 1989; Liu & Nation, 1985).

Successful inferencing strategies range from those related to the

internal structure of the words and their components, including the

various phonemic, phonetic, graphemic, and morphemic clues (Chern,

1993; Haynes 1993), to the information about the syntactic and semantic

relationship among words, and even to the various higher order,

extratextual, and discoursal clues (de Bot et al., 1997; Huckin & Bloch,

1993). In a recent study, de Bot et al. (1997) found that L2 readers used

knowledge sources ranging from knowledge of grammar, morphology,

phonology, and knowledge of the world, to knowledge of punctuation,

word association, and cognates.

Based on the results of an exploratory study on inferring word

meanings from context by three intermediate Chinese students, Huckin

and Bloch (1993) proposed a cognitive processing model of L2 lexical

inferencing. The model incorporates two separate components: a gen-

erator and evaluator component and a metalinguistic control compo-

nent. The generator and evaluator component includes numerous

interconnected knowledge-based modules, such as a vocabulary knowl-

edge module, a text schema module, a syntax and morphology module,

and a text representation module. The function of the generator and

evaluator component is to generate and evaluate hypotheses about the

meaning of the word encountered based on the various knowledge

sources in the module. The metalinguistic control component includes a

sequence of serial and parallel decision-making steps that the learner

goes through when trying to generate and test hypotheses. These

processes help the learner decide when and how to proceed and seek

help from context and various sources of knowledge available.

Huckin and Bloch (1993) showed that learners appealed to various

knowledge sources and employed various cognitive strategies in their

attempts to infer word meanings from context. They also provided

evidence for the degree to which these processes were used and how they

related to success. Paribakht and Wesche (1999) found that their

university ESL readers also appealed to a variety of linguistic and

648 TESOL QUARTERLY

nonlinguistic knowledge sources when attempting to derive the mean-

ings of new words from context. They also found that the use of these

knowledge sources was affected by a number of other factors, such as

type of text (summary vs. question), text characteristics (e.g., topic,

content, genre), and word characteristics (e.g., verb, adjective, noun).

This approach to explaining inferences is consistent with that of

Pressley, Borkowski, and Schneider (1987), who distinguish between

learners’ cognitive strategies and their knowledge base, but go a step

further to explain the relationship between strategy use and success.

Pressley et al. conceived of ve factors that were considered important in

successful strategy use: (a) having a wide repertoire of general as well as

domain-speci c strategies; (b) having the ability to use strategies appro-

priately and in appropriate contexts; (c) having an extensive task-

relevant knowledge base, ranging from general knowledge of the world

to knowledge about speci c strategies and their causes of success and

failure; (d) being able to automatically execute and coordinate the use

of strategies with various knowledge sources; and (e) having an aware-

ness that, although success is related to efforts, efforts alone may not be

enough. In this context, Pressley et al. (1987) made a distinction

between “effort attribution and strategic effort attributions” (p. 104),

according to which, good strategy users realize that what matters is not

just efforts but efforts that are strategic and task matching.

Strategies, Knowledge, and Success

A fundamental question that has remained unanswered throughout

this research concerns the relationship between the range of strategies

and knowledge sources learners use and their success in lexical

inferencing. Most of the studies conducted so far on the role of learners’

strategies have been descriptive, so to what extent the strategies assist

them in deriving word meaning from context is not known. To address

this question and better understand these processes and their contribu-

tions to success in inferencing, the present study was designed to

determine (a) how successfully intermediate ESL learners infer word

meanings from context in a reading text, (b) what strategies and

knowledge sources they use to do so and to what extent, and (c) whether

there is any relationship between the range of strategies and knowledge

sources they use and their lexical inferencing success.

METHOD

I chose introspective methods for the research because the object of

investigation was the set of strategies and knowledge deployed during

L2 VOCABULARY LEARNING FROM CONTEXT 649

the reading process. I carefully selected the participants and reading

passage to ensure an appropriate level match.

Participants

Twenty-one adult ESL learners (10 males, 11 females) voluntarily

participated in the study. They represented ve different language

backgrounds, including Arabic (2), Chinese (8), Persian (6), Portuguese

(2), and Spanish (3). They had all recently arrived in Canada and were

enrolled in a 12-week intermediate ESL program to improve their

English. All had met Level 4 of the Canadian Language Benchmark test

(e.g., Citizenship and Immigration Canada, 1996), which evaluates the

ESL pro ciency of adult newcomers to Canada for the purpose of

instructional placement. Using task- and performance-based criteria, the

test assesses learners in three language skills areas (speaking and

listening, reading, and writing) on a continuum of 1–12 benchmarks

(see Peirce & Stewart, 1997).

The Reading Passage

Because the research concerned successful inferencing, I had to nd

a text that contained a minimum number of words that the participants

would know (e.g., Laufer, 1989; Liu & Nation, 1985; Nation, 2001). As

mentioned earlier, research suggests that readers should know a high

percentage (at least 95%) of the words in the text in order to be able to

infer successfully (Liu & Nation, 1985). The text also had to match the

comprehension ability of the intermediate readers. Among the passages

I examined, including those used in previous research, I chose the one

used in Haastrup’s (1991) study (see the Appendix). The passage

contained 374 words, 10 of which were target words that I used to focus

on inferencing strategies. The target words were all content words

consisting of four nouns, four verbs, and two adjectives.

I organized a panel of three ESL teachers who were working with the

students to determine the appropriateness of the passage in terms of its

reading level and content. To further check the appropriateness, I

piloted the passage with a group of ESL students assumed to be similar to

the participants in the main study with respect to language pro ciency

and level of reading comprehension measured in terms of the Canadian

Language Benchmark. The students were asked to underline any words

they did not know when reading the passage and further con rm them

in retrospective interviews. The percentage of unknown words was then

calculated for each student by dividing the total number of words they

650 TESOL QUARTERLY

reported as unknown by the total number of words in the passage

multiplied by 100.

The pilot study revealed that the students had a good comprehension

of the text. Their mean scores on a comprehension test consisting of 10

questions was 7.6, and the number of unknown words for them,

including the 10 target words, ranged from 4.27% to 2.67% (which was

less than 5%). This percentage was later found to be very close to the

percentage obtained in the main phase of the study (4.01% to 1.06%).

Data Collection

Data were collected in individual sessions in which the researcher met

with each learner in a quiet room for about 45–60 minutes. To guarantee

the equality of procedures, I conducted all the data collection sessions.

Think-aloud techniques, which were used as the main data collection

tool, are procedures requiring participants to verbalize and report the

content of their thoughts while doing a task. Despite some criticism of

the think-aloud procedure, it is a common methodology used in strategy

research (Ericsson & Simon, 1993; Pressley & Af erbach, 1995). More-

over, such data, if not a true re ection of, have at least been assumed to

be associated with the processes participants use in processing language

(Olson, Duffy, & Mack, 1984). Introspective and immediate retrospective

reports were also used in this study. However, the data about the use of

strategies and knowledge sources derive mainly from the introspective

reports because they involve more direct and online reporting of what

learners are doing at the time of the task than do retrospective reports,

which ask learners to recall what they had done before (Olson, Duffy, &

Mack, 1984). The retrospective reports were used mainly to nd out if

the learners had additional comments on their familiarity with the words

or their inferencing processes.

At the beginning of each session, I informed learners of the general

purpose of the study. They then participated in a training and practice

period in which I introduced them to the think-aloud procedure and

explained how they were to verbalize their thoughts. Participants also did

role plays using pictures as well as similar reading texts for training

purposes. After the training and practice period, when I felt that the

learners knew how to think aloud, I presented the reading passage and

instructed them to read it out loud. As they encountered each italicized

target word in the text, I asked them to try to infer its meaning from the

context, verbalizing and reporting whatever came to their mind. I also

asked them to underline and try to infer the meaning of any other words

whose meaning they did not know. I advised them that they could refer

back at any time to an unknown word to try to infer its meaning again.

L2 VOCABULARY LEARNING FROM CONTEXT 651

When they nished reading, I asked them to review the passage and

make any additional comments they wished about any new words and

their thinking processes. For transcription purposes, I audiotaped the

think alouds and retrospective reports.

RESULTS

Results indicate that the intermediate-level ESL learners were not very

successful at inferring word meanings from context in a reading text.

More speci cally, the results show what strategies and knowledge sources

these learners used during the process of inferencing in addition to the

relationship between strategies, knowledge, and inferencing success.

Success of Lexical Inferencing

To determine the degree to which learners were successful at

inferencing, I and an experienced native-English-speaking teacher inde-

pendently rated their responses to each of the unknown words using a

3-point scale (2 = successful, 1 = partially successful, 0 = unsuccessful ).

Successful inferencing was de ned as responses that were semantically,

syntactically, and contextually appropriate. A successful response could

be a word representing an accurate semantic meaning of the target word

(e.g., a synonym) or an appropriate de nition of the word. Because it

was possible to arrive at a completely accurate semantic meaning of a

word and yet associate the word with a wrong syntactic category (Gass,

1999), for rating purposes, we classi ed responses that were semantically

appropriate but syntactically deviant, or vice versa, as partially successful.

In order not to underestimate learners’ success, if the meaning or the

de nition they provided made sense in the context but when judged out

of context was not the meaning of the word, we still considered the

response partially successful. In cases where the response did not meet

any of the above conditions, we considered it unsuccessful.

During initial rating, we obtained an interrater agreement of 94%. We

then resolved disagreements through subsequent discussion to reach

100% interrater agreement on all items.

The question about success was addressed by looking at individual

lexical items. Because the 21 participants each responded to the 10

target lexical items, the initial data set contained 210 responses of

interest. However, the initial set of responses was reexamined in view of

some participants’ indications during the reading and retrospective

interviews that they knew some of the target words. Omitting the

responses for individual participants on the speci c words they indicated

652 TESOL QUARTERLY

knowing reduced the number of target words to 199, for which responses

could be interpreted as inferencing of an unknown word.

Of the total 199 inferential responses, 51 (25.6%) were successful, 37

(18.6%) were partially successful, and 111 (55.8%) were unsuccessful.

The percentage of unsuccessful inferences indicates that more than half

of the time, students went completely wrong in their attempts to infer

the meanings of the new words from context. A chi-square test con-

ducted on the raw frequency of the data revealed that the frequency of

the unsuccessful versus the successful and partially successful inferences

was signi cantly greater than the expected distribution would be ( 2 =

46.59, df = 2, p .0001).

An item-by-item analysis of the individual words indicated that the

degree of successful inferencing for each of the individual words was

quite low, ranging from 9.5% to 38.1%, with the mean percentage for all

the items being 25.6% (see Table 1). Results also showed that where at

least 95% of the words in the text were familiar, there was still a

signi cant correlation between the learner’s inferential success (ob-

tained by adding up the success scores the learner gained for each

unknown word in the 3-point scale system) and the percentage of the

remaining unknown words in the surrounding context (obtained by

calculating the number of unknown words for each individual learner

and dividing them by the total number of words multiplied by 100) (r =

2.46, p = .03). The correlation coef cient is negative because success was

correlated with the density of unknown words, thus indicating that the

higher the proportion of unknown words in the surrounding context,

the lower the likelihood of success. This nding highlights the impor-

tance of lexical density, or the ratio of known to unknown words in the

context of an unfamiliar word, and suggests that with a large proportion

of words already familiar in the text (at least 95%), ne-tuned knowledge

of the remaining words in the context is still a crucial factor in the

successful inferencing of unknown words.

Learners’ success seemed also to be related to the physical form of the

words and how they looked. Among the items guessed, the most dif cult

one was permeated, followed by squalor, afuence, and waver. The percent-

age of successful inferencing for these items ranged from 9.5% to 23.8%

(the mean percentage of correct responses being 16.65%). On average,

83.35% of the time these words were either unsuccessfully or partially

successfully inferred. The problem with these words may be related to

their misleading nature and confusion with similar-looking words. An

analysis of the learners’ protocols showed that many of the learners who

guessed the meanings of these words wrongly interpreted them by

confusing them with other similar-looking but semantically unrelated

words. For example, many of these learners mistakenly related permeated,

to meat, waver to wave, and afuence to inuence. Although some of these

L2 VOCABULARY LEARNING FROM CONTEXT 653

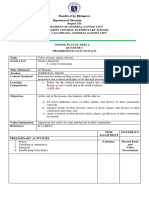

TABLE 1

Successful, Partially Successful, and Unsuccessful Inferences for Unknown Words

Inferences

Partially

Successful successful Unsuccessful

Total number

Unknown words of responses n % n % n %

1. permeated 21 2 9.5 1 4.8 18 85.7

2. squalor 21 3 14.3 4 19.0 14 66.7

3. af uence 21 4 19.0 5 23.9 12 57.1

4. waver 21 5 23.8 9 42.9 7 33.3

5. contract 19 5 26.3 0 0.0 14 73.7

6. sewage 21 6 28.6 8 38.1 7 33.3

7. curative 19 6 31.6 4 21.1 9 47.4

8. assessing 15 5 33.3 0 0.0 10 66.7

9. hazard 20 5 35.0 7 25.0 8 40.0

10. unfathomable 21 8 38.1 1 4.8 12 57.1

Total n and mean % 51 25.6 37 18.6 111 55.8

words may be etymologically and historically related, they are currently

used in quite different semantic elds. The following excerpt from the

protocol of one of the students who was attempting to infer the meaning

of the word permeated illustrates the typical problem with such words.

Permeated . . . meated . . . is a kind of meat . . . I think there are something

related with meat and the body . . . permeated with such things as chemical

and radio active.

This nding suggests that the words’ appearance and their similarity with

other unrelated words may be a major source of problems in inferring

word meanings from context (see also Bensoussan & Laufer, 1984;

Laufer & Sim, 1985). It may also suggest that precise inferencing of

words may be related to how accurately learners recognize and decode

the orthographic form of the word (Ryan, 1997).

Strategies and Knowledge Sources

Following Pressley, Borkowski, and Schneider’s (1987) distinction

between learners’ cognitive strategies and knowledge base and Huckin

and Bloch’s (1993) distinction between knowledge sources and

metalinguistic decision-making strategies in their model of inferring

word meanings from context, this study makes a distinction between the

654 TESOL QUARTERLY

use of knowledge sources and strategies. I de ned strategies as conscious

cognitive or metacognitive activities that the learner used to gain control

over or understand the problem without any explicit appeal to any

knowledge source as assistance. In contrast, I de ned appeals to knowledge

sources as instances when the learner made an explicit reference to a

particular source of knowledge, such as grammatical, morphological,

discourse, world, or L1 knowledge.

To determine the different types of strategies and knowledge sources

learners used, I had all the introspective think-aloud protocols initially

transcribed verbatim before being carefully examined and coded twice,

once by me and then by a colleague. For coding categories, I consulted

the literature on vocabulary learning and lexical inferencing strategies

(e.g., de Bot et al., 1997; Haastrup, 1991; Huckin & Bloch, 1993; Parry,

1991, 1993; Schmitt, 1997). However, the coding scheme I used derives

mainly from the data and re ects the thinking of the learners participat-

ing in the study rather than from pre-existing categories imposed on the

data. Coding involved reading and rereading the protocols and identify-

ing in an inductive manner the kind of inferencing strategies and

knowledge sources used. I established the reliability of the coding by

calculating an intercoder agreement on a sample of 20% of the data,

selected from every fth participant. The intercoder agreement for that

20% of the data was 89%. The second coder and I resolved discrepancies

through discussion to achieve 100% agreement. I then examined and

coded the remaining data.

I identi ed a total of 11 categories of strategy types and knowledge

sources. Knowledge sources used included grammatical knowledge,

morphological knowledge, knowledge of L1, world knowledge, and

discourse knowledge. Strategy types included repeating, verifying, ana-

lyzing, monitoring, self-inquiry, and analogy. Repeating was further

divided into, and coded as, word repeating when the learner repeated

the word alone and as section repeating when the learner repeated a

bigger section in which the word had occurred, such as the clause or the

sentence. Table 2 presents the categories of knowledge sources and

strategy types identi ed, along with de nitions and examples from the

transcripts.

Of all the knowledge sources, students used world knowledge most

frequently (46.2%), followed by morphological knowledge (26.9%).

They did not use grammatical knowledge very widely (11.5%), and they

used discourse knowledge (8.7%) and L1 knowledge (6.7%) least

frequently (Table 3). The ndings also showed variation among students

in terms of the types of knowledge sources they used. For example,

whereas 71% of the students used world knowledge, only 33% used

discourse knowledge. Due to the number of participants in the study, I

did not further analyze individual variations and their consequences.

L2 VOCABULARY LEARNING FROM CONTEXT 655

TABLE 2

De nitions and Transcript Examples of Knowledge Sources and Strategies

Students Used to Make Lexical Inferences

Knowledge source De nition Example

Grammatical Using knowledge of grammatical “curative effect of medicine.” . . .

knowledge functions or syntactic categories, According to it is adjective . . .

such as verbs, adjectives, or adverbs mmm . . . it is something before

the effect.

Morphological Using knowledge of word “unfathomable.” . . . I don’t know

knowledge formation and word structure, unfathomable . . . ‘un’ . . . it is

including word derivations, negative of fathomable.

in ections, word stems, suf xes,

and pre xes

World knowledge Using knowledge of the content or I think the “sewage” is like

the topic that goes beyond what is something that is produces, . . .

in the text because of some of some illness

that these people have, they are

talking about some problems that

the people have in Africa.

L1 knowledge Attempting to gure out the “assessing . . . .” I forgot the idea

meaning of the new word by . . . Oh I got the meaning . . . I got

translating or nding a similar it in Chinese, like if I want to apply

word in the L1 for position of professional

engineer I should pass the the

assessment of some organizations

like the professional engineering

organization.

Discourse Using knowledge about the “far from being mysterious and

knowledge relation between or within unfathomable . . .” unfathomable is

sentences and the devices that like mysterious something that is

make connections between the not known for everybody. Because

different parts of the text they are talking about the causes of

some disease and they they are

saying they are mysterious.

Continued on page 657

This question can be addressed in future research using more in-depth

case studies of individual learners (see Huckin & Bloch, 1993; Parry,

1991, 1993).

Of all the strategies, students used repeating (including word repeat-

ing and section repeating) most frequently, accounting for about two

thirds (63.7%) of the strategies used. Of the two types of repeating,

students used word repeating much more frequently than section

repeating (39.7% vs. 24%). Other strategies students used much less

frequently were analogy (8.5%), verifying (7.9%), monitoring (7.2%),

self-inquiry (7.2%), and analyzing (5.5%) (see Table 4). Moreover,

whereas all learners used repeating, only 66.6% used self-inquiry, 61.9%

656 TESOL QUARTERLY

TABLE 2 (Continued)

De nitions and Transcript Examples of Knowledge Sources and Strategies

Students Used to Make Lexical Inferences

Strategies De nition Example

Repeating Repeating any portion of the text, “our beliefs waver . . . waver . . .

including the word, the phrase, or waver . . . .” May be . . . waver is

the sentence in which the word has something “beliefs waver . . .”

occurred

Verifying Examining the appropriateness of “but when we ourselves become ill,

the inferred meaning by checking our beliefs waver . . .” our beliefs

it against the wider context change . . . change . . . when we

become ill our beliefs change . . .

yeah.

Self-inquiry Asking oneself questions about the “hazards . . .” should it be pollution

text, words, or the meaning already according to the sentence?

inferred “pollutions?” No no . . . it should

not be that . . . it may be

something different.

Analyzing Attempting to gure out the “and smell of sewage in their

meaning of the word by analyzing noses . . .” sew, age . . . should be a

it into various parts or components kind of smell. But sew is

something, may be it is a kind of

plant, wood.

Monitoring Showing a conscious awareness of “contract some of the serious and

the problem or the ease or infectious diseases . . .” contract . . .

dif culty of the task I think contract is is make from

boss and the staff . . . contract . . .

yes . . . this is easy . . . this easy . . .

maybe it’s dif cult, I am not sure.

Analogy Attempting to gure out the “squalor . . .” may be it is like

meaning of the word based on its square . . . square . . . It should be

sound or form similarity with other something like that.

words

used verifying, 79.19% used analogy, 61.9% used analyzing, and 80.95%

used monitoring, suggesting that not all the students used all the

strategies and that there was variation among students in terms of types

of strategies used.

Relationship of Strategies to Success

To determine the relationship between successful inferencing and the

strategies and knowledge sources used, I rst calculated the percentage

of successful, partially successful, and unsuccessful inferences for each

L2 VOCABULARY LEARNING FROM CONTEXT 657

TABLE 3

Students’ Use of Knowledge Sources

Knowledge source n %

World knowledge 48 46.2

Morphological knowledge 28 26.9

Grammatical knowledge 12 11.5

Discourse knowledge 9 8.7

L1 knowledge 7 6.7

Total 104 100

strategy type and knowledge source. I then calculated a mean of success

for each strategy type and knowledge source. To that end, I divided the

sum of the scores obtained for success in inferencing the target words by

the total frequency of each strategy or each knowledge source used to

infer the meaning of those words.

Among the knowledge sources used (see Table 5), morphological

knowledge had the highest mean of success (.93), followed by world

knowledge (.83). These knowledge sources were associated with more

successful inferences than other knowledge sources (morphological

knowledge: 35.7% successful; world knowledge: 29.2% successful). L1

knowledge had the lowest mean of success (14.3%) and was least

associated with successful inferences. Statistical comparison of the means

of the knowledge sources and a two-way chi-square test on the frequency

of these knowledge sources and the degree of their success revealed no

statistically signi cant differences in the contribution of different knowl-

edge sources—analysis of variance (ANOVA): F(4, 99) = .355, p = .84; 2 =

2.53, df = 8, p = .96. This indicates that whereas some of the knowledge

TABLE 4

Students’ Use of Strategies

Strategies n %

Word repeating 187 39.7

Section repeating 113 24.0

Analogy 40 8.5

Verifying 37 7.9

Monitoring 34 7.2

Self-inquiry 34 7.2

Analyzing 26 5.5

Total 471 100

658 TESOL QUARTERLY

TABLE 5

Knowledge Sources and Inferential Success

Inferential success

Partially

Successful successful Unsuccessful Total

Knowledge M of

source success SD n % n % n % n %

Grammatical .67 .89 3 25.0 2 16.7 7 58.3 12 100

Morphological .93 .90 10 35.7 19 21.4 12 42.9 28 100

L1 .57 .79 1 14.3 6 28.6 4 57.1 7 100

World .83 .86 14 29.2 6 25.0 22 45.8 48 100

Discourse .78 .83 2 22.2 3 33.3 2 44.4 9 100

Total .82 .86 30 28.8 25 24.0 49 47.1 104 100

sources contributed more to successful inferencing than others, success

did not depend much on what kind of knowledge source was used.

Table 6 displays the means as well as the percentages of successful

inferences for the different types of strategies used. Among strategies,

verifying, self-inquiry, and section repeating were associated with higher

means of success than were other strategies. The means of success for

these strategies were 1.51, 1.15, and 1.05, respectively. Verifying and self-

inquiry were associated with the highest means of success and the

greatest proportion of successful inferences as compared to other

strategies (67.6% and 52.9%, respectively). Of the two subcategories of

TABLE 6

Types of Strategies and Inferential Success

Inferential success

Partially

Successful successful Unsuccessful Total

Knowledge M of

source success SD n % n % n % n %

Word repeating .66 .84 45 24.1 33 17.6 109 58.3 187 100

Section

repeating 1.05 .91 50 44.2 19 16.8 44 38.9 113 100

Verifying 1.51 .77 25 67.6 6 16.2 6 16.2 37 100

Analogy .40 .71 5 12.5 6 15.0 29 72.5 40 100

Self-inquiry 1.15 .96 18 52.9 3 8.8 13 38.2 34 100

Analyzing .73 .92 8 30.8 3 11.5 15 57.7 26 100

Monitoring .94 .92 13 38.2 6 17.6 15 44.1 34 100

Total .86 .91 164 34.8 76 16.1 231 49.0 471 100

L2 VOCABULARY LEARNING FROM CONTEXT 659

repeating, section repeating in comparison to word repeating was

associated with a higher mean of success (1.05 vs. .66) and a higher

percentage of successful inferencing (44.2% vs. 24.1%). Analogy was

associated with the lowest mean of success (.40) and the least proportion

of successful inferences (12.5%). An ANOVA conducted on the means of

success for strategies and a two-way chi-square test conducted on the

strategy types and their proportion of success revealed a statistically

signi cant difference in the contribution of the different strategies—

ANOVA: F(6, 464) = 8.85, p .001; 2 = 51.10, df = 12, p .001. These

ndings indicate that success in inferencing depended signi cantly on

what kind of strategy learners used.

Further analysis of the data showed, however, that none of the

strategies and knowledge sources, even the most successful one, was

100% successful alone. In fact, none of the means of success reached 3

(i.e., fully successful). I also found variations in strategy use both within

individual participants and across items guessed. This suggests that

successful inferencing may be the result not of using one strategy or

knowledge source over and above other strategies but of the extent to

which various kinds of strategies and knowledge sources converge and

link. Due to the number of participants in the study, however, I did not

analyze such individual variations. This question can be addressed in

future research using more in-depth case studies of individual learners

(see Huckin & Bloch, 1993; Parry, 1991).

Another point concerns the relationship of success with the number

versus the kind of strategies used. Out of the total number of strategies

used (n = 471), about half (231) were associated with unsuccessful

inferencing. However, out of the total number of strategies associated

with unsuccessful inferencing (231), about half (109) were word repeat-

ing, with fewer instances of the other more elaborative strategies. In the

case of successful inferences, on the other hand, relatively more in-

stances of section repeating (50), verifying (25), and self-inquiry (18)

can be seen. These ndings suggest that success in inferencing may not

be related as much to the quantity as to the quality of the strategies used

(see also Vann & Abraham, 1990).

DISCUSSION

The results of this research offer some insight into the process of

inferencing vocabulary meaning during L2 reading and guidance for

teaching vocabulary through reading.

660 TESOL QUARTERLY

Explanation of L2 Inferencing

The ndings of this research can be explained through a combination

of the cognitive model of vocabulary learning from context developed by

Huckin and Bloch (1993) and the model of good strategy users (GSU)

by Pressley et al. (1987). Huckin and Bloch’s model includes knowledge

sources and strategies as the explanatory factors for vocabulary inferencing

in general, whereas the GSU model attempts to explain the differential

effects of strategy use.

Knowledge Sources

Among knowledge sources, students used general knowledge of the

world most frequently, indicating that they were very dependent on this

kind of knowledge when inferencing word meanings from context and

that this knowledge provided an important knowledge base for their

judgments. Students did not use grammatical knowledge very often,

which may indicate that information about the grammatical function of

the words was not something they needed to infer the meanings of the

new words from context. However, even when used, this knowledge

source was not associated with much success.

This nding is consistent with what Parry (1993) found about the

usefulness of grammatical knowledge in a longitudinal study that investi-

gated how a Japanese student extracted the meaning of unknown words

from an academic text. Parry found a greater semantic than syntactic

relationship between the words and their inferred meanings. In her

study, the learner almost always had been able to infer the syntactic

information about the unfamiliar words even in cases where the inferred

meaning was a wrong meaning. This, then, may suggest that knowing the

grammatical function of a word or that a word belongs to certain

syntactic categories such as verbs, adjectives, or adverbs may not lead to

an accurate semantic representation of the word in context. Interpreted

that way, it may provide support for the idea that the process of

extracting an accurate conceptual meaning about an unknown word

from context is a lemma construction process (de Bot et al., 1997), in

which word meaning may not develop simply from resort to the syntactic

information about the word, something which can be done very easily by

most skilled learners. Rather, it may develop from a nal semantic

speci cation, which should be accessed and matched with the concep-

tual information existing in the learner’s conceptual system.

L2 VOCABULARY LEARNING FROM CONTEXT 661

Strategies

The strategies learners used included repeating, verifying, monitor-

ing, self-inquiry, analyzing, and analogy. Within Huckin and Bloch’s

(1993) model, the role of these strategies can be seen as examples of

cognitive decision-making processes learners use while interacting with

the text and formulating and testing their word meaning hypotheses.

Results showed that learners used repeating as the major strategy. The

fact that they used this strategy very often is not surprising because

repeating can aid both comprehension of and re ection on the content.

However, of the two types of repeating, section repeating led to signi -

cantly higher means of success and was more associated with successful

inferencing than word repeating. The advantage of section repeating

may in part relate to the role of this strategy in assisting the learner to

relate the word to the phrase or sentence in which it has occurred and to

use the potential cues available in those contexts. Thus, it seems to

support the idea that success in inferencing is more related to the degree

to which the learner’s strategy in processing the word is global than local

(Dubin & Olshtain, 1993; Haynes, 1993; Huckin & Coady, 1999; Nation,

1990).

Among strategies, however, verifying and self-inquiry were related

more to successful inferencing than other strategies. This nding seems

to provide evidence for the important role of these metacognitive

strategies in lexical inferencing. The advantage of these strategies may in

part relate to the role of these processes in assisting learners to examine

the accuracy of their guesses and revise or reevaluate them against the

information provided in the wider context. Self-inquiry, in particular,

may help learners to concentrate on their inferences by actively ques-

tioning them and then looking for alternative solutions in cases where

they nd them to be wrong. Several research studies in L1 have shown

the potential bene ts of using self-inquiry in reading and understanding

whole texts (Andre & Anderson, 1978; Frase & Schwartz, 1975; Singer &

Donlan, 1982). These studies suggest that self-inquiry may lead to more

active processing of materials being read and the activation of relevant

background knowledge (Wong, 1985). It is possible that the use of this

strategy in lexical inferencing may do the same. It may also make

students more conscious of the problem and then better enable them to

research solutions.

Analysis showed, however, that although some of the strategies were

more related to successful inferencing than others, the overall contribu-

tion of these strategies was partial and limited. This suggests that success

in inferencing may not depend just on the use of certain strategies but

also on how effectively the use of strategies is combined and coordinated

662 TESOL QUARTERLY

with the use of other sources of information in and outside the text. In

the present study, for example, students used word repeating and

analogy very often, but these efforts were not associated with much

success. Within Pressley et al.’s (1987) framework, these strategies could

be taken as examples of nonstrategic attempts.

Other examples of nonstrategic attempts were evident in the heavy

reliance on word repeating that may re ect a narrow word-based

approach to lexical inferencing used by these intermediate-level ESL

students, which may have contributed to the overall low rate of success as

well (see Qian, 1998, for similar results). Indeed, repeating the word

itself can be a helpful strategy, particularly, when it can help the student

access the meaning of a word through eliciting a phonological or

orthographic representation of the word in the lexicon (Ellis & Beaton,

1993). However, this strategy turned out to be ineffective in this study,

partly because most of the target words in the text were low-frequency

words and words that were completely unknown to the students. When

the word is completely unknown, students are unable to get much out of

repeating the word itself simply because there is little conceptual

reference for the word in their lexicon.

Analogy can also be a helpful strategy and can sometimes be used as a

means of retrieving the meaning of a word through associating it with

other neighboring words. However, it may fail if there are pseudo-similar

words in the text and if students fail to distinguish the word from those

that are deceptively similar (Bensoussan & Laufer, 1984; Haynes, 1984,

Huckin & Bloch, 1993). In such cases, analogy may lead to what Huckin

and Bloch (1993) called a “mistaken ID” (p. 166), a process whereby the

student takes a word for another similar-looking word.

Pedagogical Implications

This study demonstrated that the ESL students experienced dif culty

in successfully inferring the meanings of unknown words from context,

even though they reported knowing most of the words in the text and

used the strategies and knowledge sources they had at their disposal.

This nding adds to and con rms the literature in both L1 and L2

learning that inferring new word meanings from context is not an easy

task (e.g., Bensoussan & Laufer, 1984; Kelly, 1990; Prince, 1996; Schatz &

Baldwin, 1986; Shu, Anderson, & Zhang, 1995). The low mean percent-

age of correct inferences found in this study (25.6%) seems to replicate

the ndings of Bensoussan and Laufer’s (1984) study, in which context

helped L2 learners with guessing only 24% of the words with no positive

effect on the remaining 76% of the words. These ndings call into

L2 VOCABULARY LEARNING FROM CONTEXT 663

question the ef cacy of contextual inferencing in L2 vocabulary acquisi-

tion and consequently lend support to theories that posit a central role

for instructed L2 vocabulary learning.

This nding suggests that in ESL learning classrooms, students should

not be pushed to rely too much on context to learn the meanings of new

words. Teachers should devote part of the class time to identifying,

de ning, and explaining the new words to the students. I do not mean,

however, to downplay the role of context in L2 vocabulary learning. Two

distinctions are important here: rst, between using context for learning

the meaning of words based on a single exposure and using context as a

means of providing multiple exposures to the same word, and second,

between using context as a means of generating new knowledge and as a

means of consolidating known knowledge. Although the results of this

study may call into question the ef cacy of context in the former sense

(i.e., generating new knowledge and learning words based on a single

exposure), there seems to be little question about the importance of

context in providing frequent exposure and a framework for consolidat-

ing and reinforcing vocabulary knowledge. This suggests that even if

explicit instruction of vocabulary is essential, it should always be consid-

ered a starting point (Schmitt & McCarthy, 1997). Once this initial stage

is undertaken, students must encounter the word in diverse contexts if

they are to build the various kinds of links and knowledge components

required for developing the full meaning of a word.

As for strategies, the study showed that successful strategies were those

that were evaluative and context-based rather than local and word-based

and that successful inferences were made by students who monitored,

considered, and judged the usefulness of the information present in the

wider context. These ndings seem to suggest a need for training

learners and helping them use such strategies when attempting to derive

word meanings from context. Teachers should help students develop a

critical awareness of the problems of local and word-based strategies by

making them aware of the fact that these strategies alone may not be very

reliable sources of information for inferring word meaning from con-

text. Students should be encouraged to adopt a more context-based

approach by going beyond the word and paying attention to the phrase,

clause, sentence, and even the paragraph in which the word is located.

Teachers should also encourage students to always make sure that their

inferences are correct by checking and verifying them against the

existing clues in the wider context.

Among the different activities teachers might use to promote these

skills in language classrooms is the use of segmented texts. Teachers

could present students with short, segmented texts. The students could

infer the meanings of certain target words in each segment as they see

each new segment of the text. As they read each segment, they could

664 TESOL QUARTERLY

evaluate the information presented in the upcoming segment and their

relationship with their inferences and then verbalize their evidence for

their responses. As Porte (1988) suggested, students could initially be

presented with a sentence or segment of a text, including a target word.

When nished with the rst segment, they could receive a series of

written prompts or questions that they should answer in a step-by-step

manner. Questions could include those about the kind of information

and clues in the rst segment, whether they used them, and also the kind

of information or clues they expect to nd in the next segment. They

would also be asked to write down their initial guesses based on the

evidence they have collected so far. They would then be presented with

the next segment of the text, followed by a series of other questions

asking them whether they want to change or to stay with their initial

responses in light of the new information, and if so why. This cycle would

then continue for each target word in each segment of the text.

The assumption here is that by virtue of these explicit efforts, learners

may become more conscious of the role of contextual clues and

strategies and, hence, more active in gaining control over their search

for relevant information and knowledge sources in the wider section of

the text. However, the value and effectiveness of these activities should

be explored in empirical research. In addition, instruction focusing on

using strategies without taking into account the range of other mediating

variables may not be very effective. In the past, researchers have

conducted many studies of the effectiveness of training learners to use

comprehension and inferencing strategies. Although some have found a

positive effect for strategy training on reading comprehension and

inferencing ability (e.g., Carrell, Pharis, & Liberto, 1989; Fraser, 1999,

Kern, 1989), others have failed to produce such strong effects (e.g.,

Barnett, 1988). Thus, learners should be trained to use effective strate-

gies but should realize that inferencing is complex and that its success

involves not only the use of appropriate strategies but also the combina-

tion and coordination of those strategies with many other skills and

knowledge sources both inside and outside the text. Lexical inferencing

also depends heavily on students’ language and comprehension skills,

the types of tasks and texts, and the nature of the word as well as a host

of other individual and learner-related variables and differences.

CONCLUSION

Investigating the cognitive structures and processes of ESL students is

a revealing enterprise, offering important insights to ESOL teachers. At

the same time, results should be interpreted in view of the tentative

nature of the data examined in the research. First, the very act of asking

L2 VOCABULARY LEARNING FROM CONTEXT 665

students to report the use of strategies may have pushed them to use or

to report to have used strategies they may not have actually used.

Students were also asked to report their thinking in their L2, English.

This decision was made because the participants were of various L1

backgrounds and it was hard to collect, translate, and compare data in

different languages. However, the decision to require the use of one

language or another adds a particular set of challenges for the learners.

In using the L2, learners may not be able to fully articulate and report

their thought processes. Second, in attempting to gain depth into the

inferencing processes, I chose a relatively short passage. This decision

was made due to the qualitative nature of the research methodology and

the amount of time involved in collecting, transcribing, and analyzing

think-aloud data. Future research might include more extended, and if

possible, diverse types of reading passages. The use of different types of

reading passages, in particular, would allow the researcher not only to

explore the various strategies learners use but also to compare the use

and effectiveness of those strategies across different types of text.

With respect to the results about success, the relationship shown in

this study between some of the strategies and the students’ success

should not be taken as cause and effect relationships. As discussed

earlier, inferencing is a process consisting of multiple components and

involving a complex interaction and coordination of a number of skills,

strategies, and knowledge sources. Studies have also shown a relationship

between students’ use of inferencing strategies and their general learn-

ing styles (Parry, 1993, 1997; see also Ehrman & Oxford, 1990), which

suggests that studies are also needed to examine how success in lexical

inferencing interacts with and is mediated by other learner-related

variables, such as learners’ general cognitive and learning style prefer-

ences. The research reported here should prove useful in conceptualiz-

ing and conducting such future research on L2 inferencing.

THE AUTHOR

Hossein Nassaji is assistant professor of applied linguistics in the Department of

Linguistics at the University of Victoria. His research interests include L2 reading

comprehension and vocabulary acquisition, focus on form instruction and negoti-

ated feedback, L2 classroom discourse, and the application of sociocultural ap-

proaches to second language acquisition.

REFERENCES

Andre, M., & Anderson, T. (1978). The development and evolution of a self-

questioning study technique. Reading Research Quarterly, 14, 605–623.

Auerbach, E. R., & Paxton, D. (1997). “It’s not the English thing”: Bringing reading

research into the ESL classroom. TESOL Quarterly, 31, 237–261.

666 TESOL QUARTERLY

Barnett, M. A. (1988). Reading through context: How real and perceived strategy use

affects L2 comprehension. Modern Language Journal, 72, 50–62.

Bensoussan, M., & Laufer, B. (1984). Lexical guessing in context in EFL reading

comprehension. Journal of Research in Reading, 7, 15–31.

Bernhardt, E. B. (1991). Reading development in a second language. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Bernhardt, E. B, & Kamil, M. L. (1995). Interpreting relationships between L1 and

L2 reading: Consolidating the linguistic threshold and the linguistic interdepen-

dence hypotheses. Applied Linguistics, 16, 15–34.

Block, E. L. (1992). See how they read: Comprehension monitoring of L1 and L2

readers. TESOL Quarterly, 26, 319–343.

Brown, C. (1993). Factors affecting the acquisition of vocabulary: Frequency and

saliency of words. In T. Huckin, M. Haynes, & J. Coady (Eds.), Second language

reading and vocabulary learning (pp. 263–286). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Carrell, P. L. (1988). Some causes of text-boundedness and schema interference in

ESL reading. In P. L. Carrell, J. Devine, & D. E. Eskey (Eds.), Interactive approaches

to second language reading (pp. 101–113). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Carrell, P. L., Pharis, B. G., & Liberto, J. C. (1989). Metacognitive strategy training for

ESL reading. TESOL Quarterly, 23, 647–678.

Carter, R. A., & McCarthy, M. J. (1988). Vocabulary and language teaching. London:

Longman.

Chern, C.-L. (1993). Chinese students’ word-solving strategies in reading in English.

In T. Huckin, M. Haynes, & J. Coady (Eds.), Second language reading and vocabulary

learning (pp. 67–85). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Citizenship and Immigration Canada. (1996). Canadian Language Benchmarks: English

as a second language for adults/English as a second language for literacy learners

[Working document]. Ottawa, Ontario: Ministry of Supply and Services Canada.

Clarke, M. (1980). The short circuit hypothesis of ESL reading—or when language

competence interferes with reading performance. Modern Language Journal, 64,

203–209.

Coady, J., Magoto, J., Hubbard, P., Graney, J., & Mokhtari, K. (1993). High frequency

vocabulary and reading pro ciency in ESL readers. In T. Huckin, M. Haynes, &

J. Coady (Eds.), Second language reading and vocabulary learning (pp. 217–226).

Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Cooper, T. C. (1999). Processing of idioms by L2 learners of English. TESOL

Quarterly, 33, 233–262.

de Bot, K., Paribakht, T. S., & Wesche, M. B. (1997). Toward a lexical processing

model for the study of second language vocabulary acquisition: Evidence from

ESL reading. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 19, 309–329.

Devine, J. (1993). The role of metacognition in second language reading and

writing. In J. Carson & I. Leki (Eds.), Reading in the composition classroom: Second

language perspectives (pp. 105–121). Boston: Heinle & Heinle.

Dubin, F., & Olshtain, E. (1993). Predicting word meanings from contextual clues:

Evidence from L1 readers. In T. Huckin, M. Haynes, & J. Coady (Eds.), Second

language reading and vocabulary learning (pp. 181–202). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Ehrman, M. E., & Oxford, R. L. (1990). Adult language learning styles and strategies

in an intensive training setting. Modern Language Journal, 74, 311–327.

Ellis, N. C. (1997). Vocabulary acquisition: Word structure, collocation, word-class,

and meaning. In N. Schmitt & M. McCarthy (Eds.), Vocabulary: Description,

acquisition and pedagogy (pp. 122–139). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ellis, N., & Beaton, A. (1993). Factors affecting the learning of foreign language

vocabulary: Imagery keyword mediators and phonological short-term memory.

Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 46A, 3, 533–558.

L2 VOCABULARY LEARNING FROM CONTEXT 667

Ericsson, K. A., & Simon, H. A. (1993). Protocol analysis: Verbal reports as data (rev. ed.).

Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Frase, J., & Schwartz, B. (1975). Effect of question production and answering on

prose recall. Journal of Educational Psychology, 67, 628–635.

Fraser, C. A. (1999). Lexical processing strategy use and vocabulary learning through

reading. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 21, 225–241.

Gass, S. (1999). Discussion: Incidental vocabulary learning. Studies in Second Language

Acquisition, 21, 319–333.

Haastrup, K. (1991). Lexical inferencing procedures or talking about words: Receptive

procedures in foreign language learning with special reference to English. Tubingen,

Germany: Gunter Narr.

Harley, B., & Hart, D. (2000). Vocabulary learning in the content-oriented second-

language classroom: Student perceptions and pro ciency. Language Awareness, 9,

78–96.

Haynes, M. (1993). Patterns and perils of guessing in second language reading. In

T. Huckin, M. Haynes, & J. Coady (Eds.), Second language reading and vocabulary

learning (pp. 46–64). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Hirsh, D., & Nation, P. (1992). What vocabulary size is needed to read unsimpli ed

texts for pleasure? Reading in a Foreign Language, 8, 689–696.

Huckin, T., & Bloch, J. (1993). Strategies for inferring word meaning in context. In

T. Huckin, M. Haynes, & J. Coady (Eds.), Second language reading and vocabulary

learning (pp. 153–178). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Huckin, T., & Coady, J. (1999). Incidental vocabulary acquisition in a second

language. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 21, 181–193.

Hudson, T. (1982). The effects of induced schemata on the “short circuit” in L2

reading: Non-decoding factors in L2 reading performance. Language Learning, 23,

1–31.

Hulstijn, J. (1992). Retention of inferred and given word meanings: Experiments in

incidental vocabulary learning. In P. Arnaud & H. Bejoint (Eds.), Vocabulary and

applied linguistics (pp. 113–125). London: Macmillan.

Joe, A. (1995). Text-based tasks and incidental vocabulary learning. Wellington, New

Zealand: English Language Institute.

Kelly, P. (1990). Guessing: No substitute for systematic learning of lexis. System, 18,

199–207.

Kern, R. G. (1989). Second language reading strategy instruction: Its effect on

comprehension and word inference ability. Modern Language Journal, 73, 135–148.

Laufer, B. (1988). What percentage of text-lexis is essential for comprehension? In

C. Lauren & M. Nordmann (Eds.), Special language: From humans thinking to

thinking machines (pp. 316–323). Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters.

Laufer, B. (1989). A factor of dif culty in vocabulary learning, deceptive transpar-

ency. AILA Review, 10–20.

Laufer, B. (1997). What’s in a word that makes it hard or easy: Some interalexical

factors that affect the learning of words. In N. Schmitt & M. McCarthy (Eds.),

Vocabulary: Description, acquisition and pedagogy (pp. 140–180). Cambridge: Cam-

bridge University Press.

Laufer, B., & Sim, D. D. (1985). Taking the easy way out: Non-use and misuse of

contextual clues in EFL reading comprehension. English Teaching Forum, 23, 7–10,

20.

Lewis, M. (1993). The lexical approach. Hove, England: Language Teaching Publica-

tions.

Liu, N., & Nation, I. S. P. (1985). Factors affecting guessing vocabulary in context.

RELC Journal, 16, 33–42.

668 TESOL QUARTERLY

Morrison, L. (1996). Talking about words: A study of French as a second language

learners’ lexical inferencing procedures. Canadian Modern Language Review, 53,

41–75.

Nassaji, H. (2002). Schema theory and knowledge-based processes in second

language reading comprehension: A need for alternative perspectives. Language

Learning, 52, 439–481.

Nassaji, H. (2003). Higher-level and lower-level text processing skills in advanced ESL

reading comprehension. Modern Language Journal, 87, 261–276.

Nation, I. S. P. (1990). Teaching and learning vocabulary. New York: Newbury House.

Nation, I. S. P. (2001). Learning vocabulary in another language. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Olson, G. M., Duffy, S. A., & Mack, R. L. (1984). Thinking-out-loud as a method for

studying real-time comprehension processes. In D. E. Kieras & M. A. Just (Eds.),

New methods in reading comprehension research (pp. 253–286). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Paribakht, S., & Wesche, M. (1999). Reading and “incidental” L2 vocabulary

acquisition: An introspective study of lexical inferencing. Studies in Second Lan-

guage Acquisition, 21, 195–224.

Parry, K. (1991). Building a vocabulary through academic reading. TESOL Quarterly,

25, 629–653.

Parry, K. (1993). Two many words: Learning the vocabulary of an academic subject.

In T. Huckin, M. Haynes, & J. Coady (Eds.), Second language reading and vocabulary

learning (pp. 109–129). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Parry, K. (1997). Vocabulary and comprehension: Two portraits. In J. Coady &

T. Huckin (Eds.), Second language vocabulary acquisition: A rationale for pedagogy (pp.

55–68). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Peirce, B. N., & Stewart, G. (1997). The development of the Canadian language

benchmarks assessment. TESL Canada Journal, 14, 17–31.

Porte, G. (1988). Poor language learners and their strategies for dealing with new

vocabulary. ELT Journal, 42, 167–172.

Pressley, M., & Af erbach, P. (1995). Verbal protocols of reading: The nature of the

constructively responsive reading. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Pressley, M., Borkowski, J. G., & Schneider, W. (1987). Cognitive strategies: Good

strategy users coordinate metacognition and knowledge. Annals of Child Develop-

ment, 4, 89–129.

Prince, P. (1996). Second language vocabulary learning: The role of context versus

translations as a function of pro ciency. Modern Language Journal, 80, 478–493.

Qian, D. (1998). Depth of vocabulary knowledge: Assessing its role in adults’ reading

comprehension in English as a second language. Unpublished PhD thesis, OISE/

University of Toronto.

Ryan, A. (1997). Learning the orthographical form of L2 vocabulary—a receptive

and a productive process. In N. Schmitt & M. McCarthy (Eds.), Vocabulary:

Description, acquisition and pedagogy (pp. 181–198). Cambridge: Cambridge Univer-

sity Press.

Sanaoui, R. (1995). Adult learners’ approaches to learning vocabulary in second

languages. Modern Language Journal, 79,15–28.

Schatz, E. K., & Baldwin, R. S. (1986). Context clues are unreliable predictors of word

meanings. Reading Research Quarterly, 21, 439–453.

Scherfer, P. (1993). Indirect L2 vocabulary learning. Linguistics, 31, 1141–1153.

Schmitt, N. (1997). Vocabulary learning strategies. In N. Schmitt & M. McCarthy

(Eds.), Vocabulary: Description, acquisition and pedagogy (pp. 199–227). Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Schmitt, N., & McCarthy, M. (1997). Introduction. In N. Schmitt & M. McCarthy

L2 VOCABULARY LEARNING FROM CONTEXT 669

(Eds.), Vocabulary: Description, acquisition and pedagogy (pp. 1–5). Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Shu, H., Anderson, R. C., & Zhang, H. (1995). Incidental learning of word meanings

while reading: A Chinese and American cross-cultural study. Reading Research

Quarterly, 30, 76–95.

Singer, H., & Donlan, D. (1982). Active comprehension: Problem solving schema

with question generation for comprehension of complex short stories. Reading

Research Quarterly, 27, 166–186.

Vann, R. J., & Abraham, R. G. (1990). Strategies of unsuccessful language learners.

TESOL Quarterly, 24, 177–198.

Wong, B. (1985). Self-questioning instructional research: A review. Review of Educa-

tional Research, 55, 227–268.

APPENDIX

Health in the Rich World and in the Poor

An American journalist, Dorothy Thompson, criticises the rich world’s health programmes in

the poor world. She describes her trip to Africa where she got food poisoning and her friend

malaria:

The town is very dirty. All the people are hot, have dust between their toes and the smell

of sewage in their noses. We both fell ill, and at ten o’clock in the morning I got frightened

and took my friend to the only private hospital in town, where you have to pay. After being

treated by a doctor, we caught the next aeroplane home.

Now, I believe that the money of the World Health Organisation (WHO) should be spent

on bringing health to all people of the world and not on expensive doctors and hospitals for

the few who can pay. But when we ourselves become ill, our beliefs waver. After we came

back to the States we thought a lot about our reaction to this sudden meeting with health

care in a poor country. When assessing modern medicine, we often forget that without more

money for food and clean water to drink, it is impossible to ght the diseases that are caused

by infections.

Doctors seem to overlook this fact. They ought to spend much time thinking about why

they themselves do not contract some of the serious and infectious diseases that so many of

their patients die from. They do not realize that an illness must nd a body that is weak

either because of stress or hunger. People are killed by the conditions they live under, the

lack of food and money and the squalor. Doctors should analyze why people become ill

rather than take such a keen interest in the curative effect of medicine.

In the rich world many diseases are caused by afuence. The causes of heart diseases, for

instance, are far from being mysterious and unfathomable—they are as well known as the

causes of tuberculosis. Other diseases are due to hazards in the natural conditions in which

we live. Imagine the typical American worker on his death-bed: every cell permeated with such

things as chemicals and radio-active materials. Such symptoms are true signs of an unhealthy

world.

From Haastrup, 1991, p. 234. Used with permission.

670 TESOL QUARTERLY

You might also like

- Chapter 1 - Assessment Concepts and IssuesDocument21 pagesChapter 1 - Assessment Concepts and IssuesRaita JuliahNo ratings yet

- DELTA Module II LSA 2 Developing PlanninDocument11 pagesDELTA Module II LSA 2 Developing PlanninSam SmithNo ratings yet

- Subject Practice Activities: Content & Language Integrated LearningDocument10 pagesSubject Practice Activities: Content & Language Integrated LearningJohnny SanchezNo ratings yet

- Lightbown, P., and Spada, N. (1998) - The Importance of Timing in Focus On Form - Focus On Form in Classroom PDFDocument20 pagesLightbown, P., and Spada, N. (1998) - The Importance of Timing in Focus On Form - Focus On Form in Classroom PDFAgustina Victoria BorréNo ratings yet

- Swain 1988 Manipulating and Complementing Content TeachingDocument16 pagesSwain 1988 Manipulating and Complementing Content TeachingCharles CorneliusNo ratings yet

- Beyond Explicit Rule LearningDocument27 pagesBeyond Explicit Rule LearningDaniela Flórez NeriNo ratings yet

- Task 5 BadnaswersDocument1 pageTask 5 BadnaswersDale CoulterNo ratings yet

- Ippd 2015-2016Document3 pagesIppd 2015-2016Arman Villagracia94% (34)

- 1994 Clement Dornyei Noels LLDocument17 pages1994 Clement Dornyei Noels LLaamir.saeed100% (2)

- Analysis of a Medical Research Corpus: A Prelude for Learners, Teachers, Readers and BeyondFrom EverandAnalysis of a Medical Research Corpus: A Prelude for Learners, Teachers, Readers and BeyondNo ratings yet

- Are Is Alves Process Writing LTMDocument24 pagesAre Is Alves Process Writing LTMM Nata DiwangsaNo ratings yet

- A Rasch Analysis On Collapsing Categories in Item - S Response Scales of Survey Questionnaire Maybe It - S Not One Size Fits All PDFDocument29 pagesA Rasch Analysis On Collapsing Categories in Item - S Response Scales of Survey Questionnaire Maybe It - S Not One Size Fits All PDFNancy NgNo ratings yet

- Helping Intermediate Learners Manage Interactive ConversationsDocument29 pagesHelping Intermediate Learners Manage Interactive ConversationsChris ReeseNo ratings yet

- Seedhouse ArticleDocument7 pagesSeedhouse ArticleDragica Zdraveska100% (1)

- Izumi & Bigelow (2000) Does Output Promote Noticing and Second Language Acquisition PDFDocument41 pagesIzumi & Bigelow (2000) Does Output Promote Noticing and Second Language Acquisition PDFAnneleen MalesevicNo ratings yet

- Nakatani - The Effects of Awareness-Raising Training On Oral Communication Strategy Use PDFDocument16 pagesNakatani - The Effects of Awareness-Raising Training On Oral Communication Strategy Use PDFOmar Al-ShourbajiNo ratings yet

- A Flexible Framework For Task-Based Lear PDFDocument11 pagesA Flexible Framework For Task-Based Lear PDFSusan Thompson100% (1)

- Lantolf 1994 Sociocultural Theory and Second Language Learning - Introduction To The Special IssueDocument4 pagesLantolf 1994 Sociocultural Theory and Second Language Learning - Introduction To The Special IssuehoorieNo ratings yet

- Roger HawkeyDocument33 pagesRoger HawkeyAna TheMonsterNo ratings yet

- Wray Alison Formulaic Language Pushing The BoundarDocument5 pagesWray Alison Formulaic Language Pushing The BoundarMindaugas Galginas100% (1)

- Ticv9n1 011Document4 pagesTicv9n1 011Shafa Tiara Agusty100% (1)