Professional Documents

Culture Documents

How The Greeks Sailed Into The Black Sea

How The Greeks Sailed Into The Black Sea

Uploaded by

onrOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

How The Greeks Sailed Into The Black Sea

How The Greeks Sailed Into The Black Sea

Uploaded by

onrCopyright:

Available Formats

How the Greeks Sailed into the Black Sea

Author(s): Benjamin W. Labaree

Source: American Journal of Archaeology , Jan., 1957, Vol. 61, No. 1 (Jan., 1957), pp.

29-33

Published by: Archaeological Institute of America

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.com/stable/501077

REFERENCES

Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article:

http://www.jstor.com/stable/501077?seq=1&cid=pdf-

reference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Archaeological Institute of America is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and

extend access to American Journal of Archaeology

This content downloaded from

62.29.13.150 on Thu, 27 Aug 2020 13:08:29 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

How the Greeks Sailed into the Black Sea

BENJAMIN W. LABAREE

Oth. .... Like to the Pontic sea, with their own colonies and with other peoples set-

Whose icy current and compulsive course tled along the shores of the Black Sea.4 Thucydides

Ne'er feels retiring ebb, but keeps due on

traced these developments,5 and Isocrates among

To the Propontic and the Hellespont. ....

others indicated that the presence of Greek trading

IN THE leading article of the Symposium on Homer

vessels in the Black Sea was by no means unusual.6

(AJA 52 [1948] i-io), Rhys Carpenter raisesIfthe the Bosporus was impassable to the merchants'

question of how Greek shipping penetrated the vessels, how was this trade carried on?

sailing

Black Sea.2 He cites three basic factors which Carpenter

make goes on to say that it was only with

this voyage difficult: i) during the sailing months

the development of the first powerfully-oared ves-

of the late spring and summer, winds in the sel,Bos-

the pentekonter, that the Greeks possessed a

porus prevail from the northeast, that is, from the

ship of sufficient speed to overcome the Bosporean

current. He demonstrates how it must have been

Black Sea into the Sea of Marmara; 2) a formidable

current runs through the Bosporus into thethe Seapentekonter,

of not the trireme, which was the

Marmara, representing the excess water from invention

the of Ameinokles in about 68o B.c. This is

several large rivers which flow into the Black Sea,

a welcome new suggestion. With a vessel at their

in particular, the Dnieper, Bug, Dniester, and

disposal which could be propelled independently

Danube rivers: this current is at its strongest,of the winds, Greek merchants no longer found the

aver-

aging four knots, during the sailing season,Bosporus

partly an impassable barrier. Carpenter con-

because the northeast winds help to pile upcludeswaterthat only with this powerfully-oared vessel

at the Bosporus end of the Black Sea, further in-the region beyond the Bosporus be reached

could

creasing its level in relation to the Sea of Marmara;

by water, thus explaining why there is no evidence

3) the ancient sailing vessel, rigged withofbut colonization

a in the Black Sea area before about

680 B.c.

single square sail, could not beat against the north-

east winds, nor was its rowing speed nearly great

The difficulty is that, according to the thesis,

enough to overcome this four-knot current.not

Hence

only the first penetration of the Black Sea, but

likewise all subsequent passages through the Bos-

"... it was never possible to sail through the straits.

porus could have been negotiated only by a power-

Yet it is well known that from the seventh cen-

fully-oared vessel such as the pentekonter or the

trireme. This assumption must be made because

tury on the Greeks established and regularly traded

1 Othello III, iii. trade often preceded actual colonial settlement. For all this

2 The present author is deeply grateful to Professor Sterling

see T. J. Dunbabin, The Western Greeks (Oxford 1948). For

Dow, of Harvard University, for suggesting this reexamination

Greek colonization of the Black Sea shores E. H. Minns, Scy-

of the problem raised in Carpenter's article and for assisting

thians and Greeks (Cambridge, Eng. 1913); M. Rostovtzeff,

him with references to the several secondary works cited.

Iranians and Greeks in South Russia (Oxford 1922). On the

8 Rhys Carpenter, "Greek Penetration of the Black Sea," AJAand varied fifth- and fourth-centuries trade to and

extensive

52 (1948) I. from South Russia, see M. Rostovtzeff, Social and Economic

41It need only be mentioned here that the openingHistory

of theof the Hellenistic World (Oxford 1926) 105-111 and

Black Sea was frequently reflected in mythology, most con-

notes. For the south shore, especially what was later the King-

spicuously in the story of the Argonauts and the wanderings

dom of Pontos, see D. Magie, Roman Rule in Asia Minor

of Odysseus before western adventures were added.(Princeton

An ex- 1950) 182-186. For summary see CAH III, 657-

cellent summary of these myths is contained in H. J. Rose,

668. To the bibliography (755-756) much is to be added. For

A Handbook of Greek Mythology (New York 1929)instance,196ff it has been shown that in the Tribute Assessment

for the Argonauts and 243ff for Odysseus. Decree of 425/4 the cities assessed in the Euxine panel re-

In the present study, it is not my purpose to attempt

quiredthe

not forty-four lines (meaning very nearly forty-four

establishment of a date for the earliest penetration of the Black

cities) but rather from forty-eight to fifty-one lines. S. Dow,

Sea but merely to show that from the first development TAPAof the

72 (1941) 83-84.

sailing vessel such penetration was possible. The actual dateI3-14.

5 Lines

on which this was first accomplished can only be established

I Isocrates, Trapeziticus 57. See also Aristotle, Economicus

on the basis of archaeological evidence from Black Sea settle-

2.1I; Herodotus 4.24, and 7.I47.

ments. In fact, recent study of western colonies has shown that

This content downloaded from

62.29.13.150 on Thu, 27 Aug 2020 13:08:29 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

30 BENJAMIN W. LABAREE [AlA 61

0.0-BLACK S

as 94

HE

,No

NW~ONDI~CH

This content downloaded from

62.29.13.150 on Thu, 27 Aug 2020 13:08:29 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

1957] HOW THE GREEKS SAILED INTO THE BLACK SEA 31

Not affecting

there were no fundamental changes only did the presence

the of rowers eliminate

basic performance of sailing vessels

thethroughout the

possibility of combining swift propulsion with

ancient period. In short, Carpenter's argument

cargo-carrying, but theis:cost of operating a rowed

throughout antiquity, no vessel could sail into the

vessel was prohibitive to all but a very few wealthy

Black Sea. individuals. The monthly payroll for a trireme in

Other readers must have felt the objection to commission has been estimated by Thucydides at

this conclusion which prompted the present study.the rate of a drachma a day for each sailor."3 On

Pentekonters and other rowed vessels were devel- this basis it would have cost well over one talent

oped for a specific purpose: to provide a high-speed to maintain a pentekonter during the sailing season,

vessel, not dependent upon the winds, with whichan extremely high fixed cost for any merchant. The

to gain control of the seas by force. The very de-very factors which gave the long ship its admirable

sign of these ships departed radically from the de- fighting qualities rendered it unfit for use as a

sign of the typical merchantman. Where the latter commerce carrier.

was broad of beam and deep of hold to provide If the long ships were unsuited for trade and

maximum cargo space, the warship was long, nar-the round ships incapable of sailing to windward,

row, and of shallow draught to permit high-speedespecially against a strong current, how then did

propulsion. The distinction reveals itself in manythe Greeks carry on commercial relations with the

ways, perhaps most clearly in the names given byPontus? In order to answer this question, we must

the Greeks to each type of vessel. The merchantclosely examine conditions in the Bosporus.

ship was generally referred to as the round ship,' The current which renders these straits difficult

the largest being known as the tubs.8 War vessels,of passage is caused principally by two factors."

on the other hand, were called long ships,9 withThe several rivers of Eastern Europe which flow

various types given such names as the shark?0 or into the Black Sea carry their largest amount of

the racehorses.n" waters when draining off the melted snows of their

The reason for this distinction has always been watersheds. This excess brings the Black Sea to its

clear. Speed and maneuverability were priority re-maximum level from the latter part of June to the

quirements for the warship, whereas economy ofend of August.' The second, and much more im-

operation was of secondary importance. Sea-borneportant, element is the action of winds blowing

trade, on the contrary, demanded a merchant ves-from the northeast during this season. These winds

sel of large capacity and low-cost operation. Neither tend to push the surface water of the Black Sea

of these prerequisites could be obtained by the usein a southwesterly direction-toward the Bosporus

of the long ship, since the very factors making for -while at the same time the Sea of Marmara is

swiftness meant a reduction in capacity and an in-similarly concentrated at its Hellespont end. A con-

crease in cost of maintenance. The long, narrow siderable current is therefore produced as Black

shape of its hull provided a minimum of space, Sea waters rush through the narrows to seek a

almost entirely occupied by the many rowerslower level in the Sea of Marmara. The interaction

needed to attain high speed. So crowded were con-of these two factors can be simply stated: while

ditions on board a trireme that few provisions forthe excess of Black Sea water gives the Bosporus

the crew could be carried along. When such a its "average" current of about three knots,"' it is

vessel was used as a cavalry transport, only sixty primarily the northeast winds which accelerate its

oars could be operated, since the cargo of thirtyvelocity to the five or six knots sometimes observed

horses entirely filled the hold.'2 A rowing vessel,in parts of the channel.7

then, when converted to a cargo carrier, could no Since the major rivers flow into the northern half

longer enjoy its original speed. of the Black Sea, their waters will be affected by

7 C. Torr, Ancient Ships (Cambridge 1894) 23, footnote 59. Pilot relative to currents in the Bosporus a

(arporfb16x). of observations made by the British naval ve

s ibid. 113. (yav"Xot). the periods August 17 to 26 and October 1

9 ibid. 23, footnote 59. (~caKpd). fact that these are not "up-to-date" findin

lOibid. 121. ( rplareLt) I ibid. io8. (KeX'r7a). bearing on the applicability of these conclus

1 ibid. 14. 13 6.31. of Bosporean currents in ancient times.

14 U.S. Hydrographic Office, Black a5

Sea ibid. 10 ibid.

Pilot (Washington

1926) 45. References to conclusions17 made

ibid. 49. in the Black Sea

This content downloaded from

62.29.13.150 on Thu, 27 Aug 2020 13:08:29 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

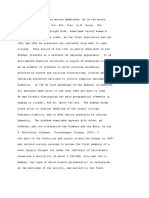

32 BENJAMIN W. LABAREE [AJA 61

wind conditions herecanas

be rated

wellas probable

assailing

over days, while

the 5.4 Bospo

On nearly twelve daysremain

in asthe

ideal. Theaverage

following table indicates sail-

sailing mon

a northeast wind blows over

ing conditions the

for the six upper

months of the sailing Black

area to assist the flow of water down toward the season:

Bosporus; whereas on ten days southwesterly winds Sailing inds AlAug. Sept.

actually tend to hold back the water from thisConditions Winds Apr. May June July Aug. Sept.

course. On the remaining days of the month the IDEAL Bosp.: southerly

winds are calm, thus not affecting this southwester- BI. Sea: southerly 7.4 7.3 5.4 3.0 2.6 3.5

PROBABLE Bosp.: southerly

ly drift.18

BI. Sea: northerlv 5.6 4-7 3.6 2.0 2.4 3.5

Winds at Istanbul are far more important, how-

IMPOss. Bosp.: northerly I7 19 21 269 26 23

ever. Not only do they directly affect the velocity

of current in the Bosporus, but they also constitute These figures represent as clearly as possible

the force upon which sailing vessels depend for "normal" conditions in the Bosporus over a six-

movement.? Southwesterly winds here not only month period. They do not take into account, how-

tend to check the current through the straits, but ever, unusual situations created by storms. For ex-

at the same time they become the favorable "fol- ample, a strong northeast storm over the Black Sea

lowing winds" which enable square-rigged vessels area will drive more than the normal amount of

to sail through the passage into the Black Sea be- water down through the Bosporus. As a result, for

yond.20 Such a wind in fact does blow on more the next few days thereafter, almost no adverse

than eight days during the average sailing month. current is to be found in the strait, because it takes

Sailing through the Bosporus depends, then, on a some time for the level of the Black Sea to rise

combination of wind conditions both in that strait again above that of the Sea of Marmara. If a north-

and over the Black Sea as a whole. With this knowl- east gale were to be followed immediately by fresh

edge we can determine both definite and probable southerly winds, a current might even flow north

sailing days for each month of the sailing season by through the Bosporus into the Black Sea."21 These

the following method: from the number of days are exceptional occurrences, however, and are men-

of southerly winds in the Bosporus (the essential tioned here mainly to show how important in this

condition for sailing through) subtract those days problem is the behavior of the wind.

during which it is probable that northerlies over These calculations based on observations taking

the Black Sea are increasing the current in the place in the late nineteenth century22 are not neces-

strait. Thus, if, as in the month of June, northerlies sarily applicable to the ancient period, with which

blow over the northern part of the Black Sea on we are primarily concerned here. And yet in

twelve of thirty days (or forty percent.) then on the absence of evidence to the contrary, we can

forty percent. of the "southwesterly days" at the only assume that conditions were basically the same

Bosporus currents can be expected to be of above- then as now. Carpenter cites one possible difference,

average velocity. Of the nine days in June with viz. that climatologists believe the first millennium

southwesterlies in the Bosporus, therefore, 3.6 days B.c. to have been unusually wet, and that therefore

18 The number of days each month during which winds inin Black Sea Pilot Ap

the northwest part of the Black Sea blow from the two prin- winds marked "north

cipal directions with which we are concerned has been de-the Bosporus, while

termined by averaging the results of wind observations at Var-There are no days of

na, Odessa, and Sevastopol (underlined on the accompanying Istanbul Apr. May June July Aug. Sept.

map). See Black Sea Pilot Appendix III, 426 (Varna) 428

(Odessa) and 430 (Sevastopol). In the following table, winds northerlies 17 19 21 26 26 23

marked "northerly" blow toward the Bosporus, those marked southerlies i 13 12 91 5 5 7

"southerly" away from this area:

21 ibid. 49.

Northwest Black Sea Apr. May June July Aug. Sept. 22 The meteorological tables to be found in Appendix III

northerlies 13 12 12 13 15 15 of the Black Sea Pilot were taken from the British Admiralty

Sailing Directions and are based on various periods of observa-

southerlies 12 13 13 12 11 10

tion as noted above each table. As in the case of the observa-

calm 5 6 5 6 5 5

tions on currents in the Bosporus (see footnote 14), it makes

19 ibid. 45, 49. little difference to the present study that these observations

20 The number of were not recently made. each

days month du

Istanbul blow from the two principal di

This content downloaded from

62.29.13.150 on Thu, 27 Aug 2020 13:08:29 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

1957] HOW THE GREEKS SAILED INTO THE BLACK SEA 33

the Black Sea received even more water than in Leucon ... has granted exemption from duty to

the modern period. This possibility, on the other

those who export to Athens ... When he made a

new harbor at Theodosia [in the Crimea] ... he

hand, is countered by the fact that centuries of cul-

tivation have stripped the natural vegetation fromgave us [Athenians] the exemption there also."24

the watersheds of the great rivers flowing into the To be sure, triremes and other galley-type ves-

Black Sea. One might conclude from this that sels a entered the Black Sea, but not as cargo car-

higher percentage of precipitation, unchecked by riers. Rather, as is suggested by Aristotle and De-

mosthenes, the role of the warship was to protect

forest and undergrowth, now drains into the rivers.

Whatever the precise amount of water flowing into the grain fleet from attack by the inhabitants of

the Black Sea in ancient times, the behavior of the

Byzantium and Chalcedonia.25

winds remains the basic factor affecting navigation One can easily see how these merchantmen

of the Bosporus. There is no evidence that winds passed through the tricky straits on their voyage

into the Black Sea. After several stops along the

in ancient times differed from the pattern observed

in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. route, they arrived off the Bosporus prepared to

The strongest evidence from antiquity to wait

be for the appearance of a favorable wind to

take them through. In the spring, when Greek mer-

found influencing this question of penetration into

the Black Sea is the fact that the Greeks wrote chants would most likely send their vessels in for

the Black Sea grain crop, this delay might be ex-

about vessels sailing to the Pontus as if there were

no particular problem involved. Demosthenes' Ora- pected to last four or five days at most. In summer

a

tion Against Lacritus deals specifically with a law- week or more might pass before a southwest

suit arising from the following agreement: wind came up. With a good breeze from behind

and the current slowed to two knots, or perhaps

Androcles of Sphettus and Nausicrates of Carystus

have lent to Artemo and Apollodorus, both of Pha-less, the typical merchantman could negotiate the

seventeen-mile passage in eight or nine hours, un-

selis, three thousand drachms in silver from Athens

to Mende or Scione and thence to Bosporus [in the der sail alone. One may conclude, therefore, that it

Crimea], or, if they please, on the left coast as far

was regularly possible to sail through the Bosporus.

as the Borysthenes [the Dnieper River] and back

In no other way could the Greeks carry on an ac-

to Athens, at interest of two hundred and twenty-

tive trade with the Pontus.2

five for the thousand ... .23

In another oration Demosthenes notes that "... HARVARD UNIVERSITY

23 Demosthenes, Oration Against Lacritus. Greek settlements inside the Black Sea. Evidence from the

24 Demosthenes, Against the Law of Leptines. Black Sea Pilot seemed to support the theory that sailing through

25 Aristotle, Economicus, 2.1x; Demosthenes, the

50.6, 17 and

Bosporus was a difficult undertaking. His failure to realize

5.25. For alleged imperial Athenian development that

fromprevailing

a sea-winds do not necessarily blow every day of the

season, however,

route to the Black Sea as opposed to an alleged land-route to led him to his erroneous conclusion that at

the Hebros see ATL I, 465 and references. no time could a vessel sail through the Bosporus. His preoc-

26 Briefly, it would appear that Rhys Carpentercupation with the problem of conditions at the Bosporus ob-

went astray

in the following manner. Having determined that scured the more

it was the fundamental point that the pentekonters

pentekonter and not the trireme which was developedcouldby

notAmei-

successfully be used for trading purposes under any

circumstances.

nokles around 680 B.c., Carpenter decided to investigate whether

this date had any bearing on the problem of dating the earliest

This content downloaded from

62.29.13.150 on Thu, 27 Aug 2020 13:08:29 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Kritovoulos M History of Mehmed The ConquerorDocument159 pagesKritovoulos M History of Mehmed The ConqueroralibNo ratings yet

- Midnight at The Pera PalaceDocument413 pagesMidnight at The Pera PalaceRecep Samet Gürel86% (7)

- Reading Part 7 Succeed in CAEDocument2 pagesReading Part 7 Succeed in CAEGERESNo ratings yet

- Archaeological and Geographic Evidence For The Voyage of WenamunDocument36 pagesArchaeological and Geographic Evidence For The Voyage of WenamunDebborah Donnelly100% (2)

- Between Europe and Asia: A Brief History of IstanbulDocument3 pagesBetween Europe and Asia: A Brief History of IstanbulAmir SaliNo ratings yet

- West - 2003 - 'The Most Marvellous of All Seas' The Greek EncouDocument17 pagesWest - 2003 - 'The Most Marvellous of All Seas' The Greek EncouphilodemusNo ratings yet

- Hiller - Mycenaeans in Black SeaDocument15 pagesHiller - Mycenaeans in Black SeaFrancesco BiancuNo ratings yet

- North OdisseasDocument18 pagesNorth OdisseasparanormapNo ratings yet

- Drews, R. - The Earliest Greek Settlements On The Black SeaDocument15 pagesDrews, R. - The Earliest Greek Settlements On The Black Seapharetima0% (1)

- SADDINGTON Twon Notes On Roman GermaniaDocument6 pagesSADDINGTON Twon Notes On Roman GermaniaNicolás RussoNo ratings yet

- Sci1235708 6076Document4 pagesSci1235708 6076Vidzdong NavarroNo ratings yet

- Carpenter, Rhys - The Greek Penetration of The Black SeaDocument12 pagesCarpenter, Rhys - The Greek Penetration of The Black SeapharetimaNo ratings yet

- Where The Lord of The Sea Grants Passage To Sailors Through The Deep Blue Mere No More - The Greeks and The Western SeasDocument20 pagesWhere The Lord of The Sea Grants Passage To Sailors Through The Deep Blue Mere No More - The Greeks and The Western SeasLuisaNo ratings yet

- Phoenician Shipwrecks of The 8th To The 6 TH Centuries AcDocument8 pagesPhoenician Shipwrecks of The 8th To The 6 TH Centuries AcSérgio ContreirasNo ratings yet

- The Story of Extinct Civilizations of the WestFrom EverandThe Story of Extinct Civilizations of the WestNo ratings yet

- Ista 0000-0000 1996 Act 613 1 1488Document8 pagesIsta 0000-0000 1996 Act 613 1 1488Vitoria EduardaNo ratings yet

- On The Raids of Themoslems in The Aegean in The Ninth and Tenth Centuries and Their Alleged Occupationof AthensDocument10 pagesOn The Raids of Themoslems in The Aegean in The Ninth and Tenth Centuries and Their Alleged Occupationof AthensΝικολαος ΜεταξαςNo ratings yet

- A. B. Bosworth - Arrian and The AlaniDocument40 pagesA. B. Bosworth - Arrian and The AlaniDubravko AladicNo ratings yet

- Bradbury. Kpn-Boats, Punt Trade, and A Lost EmporiumDocument25 pagesBradbury. Kpn-Boats, Punt Trade, and A Lost EmporiumBelén CastroNo ratings yet

- N. G. L. Hammond - The Battle of PydnaDocument18 pagesN. G. L. Hammond - The Battle of PydnaViktor LazarevskiNo ratings yet

- The Nomenclature of The Persian GulfDocument38 pagesThe Nomenclature of The Persian GulfygurseyNo ratings yet

- 04 SeascapeDocument290 pages04 Seascapegvavouranakis100% (1)

- Eco1389 3764Document4 pagesEco1389 3764Arlord MarieNo ratings yet

- Text3076 5075Document4 pagesText3076 5075Jinong JuNo ratings yet

- Bio9637 3171Document4 pagesBio9637 3171Kenn AzulNo ratings yet

- Math7881 7145Document4 pagesMath7881 7145Shilla Mae BalanceNo ratings yet

- Bio236 947Document4 pagesBio236 947Tea sisNo ratings yet

- Yzantium Ast and EST: Project 67: China and The Mediterranean WorldDocument290 pagesYzantium Ast and EST: Project 67: China and The Mediterranean WorldAndoni CushaNo ratings yet

- India Euxine v5bDocument16 pagesIndia Euxine v5bvivek.vasanNo ratings yet

- Economic Position of CyrenaicaDocument41 pagesEconomic Position of Cyrenaicaelsharif74No ratings yet

- Adobe Scan 10-Oct-2023Document7 pagesAdobe Scan 10-Oct-2023Sachin singhNo ratings yet

- Edson 1947 TopographyofThermeDocument19 pagesEdson 1947 TopographyofThermerybrybNo ratings yet

- Phoenician Shipwrecks of The 8 TH To The PDFDocument8 pagesPhoenician Shipwrecks of The 8 TH To The PDFariman567No ratings yet

- Legendary Islands of the Atlantic: A Study in Medieval GeographyFrom EverandLegendary Islands of the Atlantic: A Study in Medieval GeographyNo ratings yet

- The Second Punic War at SeaDocument10 pagesThe Second Punic War at SeaAggelos MalNo ratings yet

- sjsdcmd9107 7537Document4 pagessjsdcmd9107 7537dcuhjdNo ratings yet

- Still Om Pimespo Forklift Xd25 Xd30 Spare Parts Catalogue deDocument22 pagesStill Om Pimespo Forklift Xd25 Xd30 Spare Parts Catalogue degarrettmartinez090198pxz100% (110)

- Egyptian Red Sea Trade: An International Affair in The Graeco-Roman PeriodDocument74 pagesEgyptian Red Sea Trade: An International Affair in The Graeco-Roman PeriodDebborah Donnelly100% (2)

- Florin Curta THE NORTH-WESTERN REGION OF THE BLACK SEA DURING THE 6TH AND EARLY 7TH CENTURY ADDocument38 pagesFlorin Curta THE NORTH-WESTERN REGION OF THE BLACK SEA DURING THE 6TH AND EARLY 7TH CENTURY ADGulyás BenceNo ratings yet

- 23 Kingdoms of Bosporus and PontusDocument74 pages23 Kingdoms of Bosporus and PontusDelvon TaylorNo ratings yet

- Wachsmann (1998) Seagoing Ships and Seamanship in The Bronze Age LevantDocument423 pagesWachsmann (1998) Seagoing Ships and Seamanship in The Bronze Age LevantMaja KalebNo ratings yet

- Singer Society-And-Economy-In-The-Eastern-Mediterranean-C - Annas-Archive - Zlib-21636002-126-132Document7 pagesSinger Society-And-Economy-In-The-Eastern-Mediterranean-C - Annas-Archive - Zlib-21636002-126-132Άρτζη ΠαπάNo ratings yet

- Black Sea PiracyDocument15 pagesBlack Sea PiracypacoNo ratings yet

- Math9509 8288Document4 pagesMath9509 8288John Paul CabreraNo ratings yet

- Taylor, E. G. R. - John Dee and The Map of North-East Asia (1955, 'Imago Mundi', Vol. 12)Document17 pagesTaylor, E. G. R. - John Dee and The Map of North-East Asia (1955, 'Imago Mundi', Vol. 12)Rowa WaroNo ratings yet

- Soc5445 2247Document4 pagesSoc5445 2247Jervis AugustoNo ratings yet

- DSFDSSDFDocument37 pagesDSFDSSDFSanthosh PNo ratings yet

- Family Med5312 - 1676Document4 pagesFamily Med5312 - 1676lailaNo ratings yet

- J. Davis 1992. Review of Aegean Prehisto PDFDocument59 pagesJ. Davis 1992. Review of Aegean Prehisto PDFEfi GerogiorgiNo ratings yet

- Boats and Ships of The Old Kingdom: Transportation For The People and For The GodsDocument35 pagesBoats and Ships of The Old Kingdom: Transportation For The People and For The GodsDebborah DonnellyNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument4 pagesUntitledAARAV SHAHNo ratings yet

- Econ5158 8411Document4 pagesEcon5158 8411Kimchee StudyNo ratings yet

- Hist1379 7070Document4 pagesHist1379 7070Falda DodolangNo ratings yet

- Influence of The Middle Kingdom of Egypt in Western Asia, Especially in ByblosDocument6 pagesInfluence of The Middle Kingdom of Egypt in Western Asia, Especially in ByblosScheit SonneNo ratings yet

- Atlantis (In: Timaeus CritiasDocument11 pagesAtlantis (In: Timaeus CritiasMuhammad Nomaan ❊No ratings yet

- Hist6474 1571Document4 pagesHist6474 1571SukaFilm 27No ratings yet

- Bio5933 163Document4 pagesBio5933 163Nezer VergaraNo ratings yet

- Jordanes - The Origin and Deeds of The GothsDocument47 pagesJordanes - The Origin and Deeds of The GothsLaurynas KurilaNo ratings yet

- Transactions of The Society For The Promotion of Hellenic Studies. The Session of 1884-5 (Pp. Xli-Liv)Document15 pagesTransactions of The Society For The Promotion of Hellenic Studies. The Session of 1884-5 (Pp. Xli-Liv)pharetimaNo ratings yet

- Into The Hinterland - The Middle Bronze Age Building at Toprakhisar H - y - K, Alt - N - Z - Hatay, Turkey (#743855) - 1122842Document36 pagesInto The Hinterland - The Middle Bronze Age Building at Toprakhisar H - y - K, Alt - N - Z - Hatay, Turkey (#743855) - 1122842onrNo ratings yet

- Aegean Art, JansonDocument10 pagesAegean Art, JansononrNo ratings yet

- Aegeans and Anatolians A Trojan PerspectDocument14 pagesAegeans and Anatolians A Trojan PerspectonrNo ratings yet

- A. Sampson 2018 He Mesolithic Hunter-GaDocument26 pagesA. Sampson 2018 He Mesolithic Hunter-GaonrNo ratings yet

- Grey Wares As A Phenomenon FULLTEXTDocument14 pagesGrey Wares As A Phenomenon FULLTEXTonrNo ratings yet

- Stone Vessels From Franchthi and Other Greek Neolithic SitesDocument58 pagesStone Vessels From Franchthi and Other Greek Neolithic SitesonrNo ratings yet

- Troy and The Troad in The Second MillennDocument21 pagesTroy and The Troad in The Second MillennonrNo ratings yet

- Provenance of The Grey and Tan Wares FroDocument20 pagesProvenance of The Grey and Tan Wares FroonrNo ratings yet

- Prehistoric Paleolithic and Neolithic MyDocument5 pagesPrehistoric Paleolithic and Neolithic MyonrNo ratings yet

- CAPE GELIDONYA A Bronze Age ShipweckDocument178 pagesCAPE GELIDONYA A Bronze Age ShipweckonrNo ratings yet

- 4 Days Trip in İstanbul, TurkeyDocument2 pages4 Days Trip in İstanbul, TurkeyPratham GarodiaNo ratings yet

- Istanbul Walks Confidential Tarif PDFDocument40 pagesIstanbul Walks Confidential Tarif PDFNicoNo ratings yet

- From Pole To PoleA Book For Young People by Hedin, Sven AndersDocument280 pagesFrom Pole To PoleA Book For Young People by Hedin, Sven AndersGutenberg.org100% (1)

- 23 Kingdoms of Bosporus and PontusDocument74 pages23 Kingdoms of Bosporus and PontusDelvon TaylorNo ratings yet

- Iranica AntiquaDocument43 pagesIranica AntiquaEduard_rungNo ratings yet

- Third Bosphorus Bridge Greisch Jy Del FornoDocument92 pagesThird Bosphorus Bridge Greisch Jy Del FornoMuhammad Umar Riaz100% (1)

- How The Greeks Sailed Into The Black SeaDocument6 pagesHow The Greeks Sailed Into The Black Seaonr100% (1)

- Turkey PA PDFDocument287 pagesTurkey PA PDFRizalNo ratings yet

- Shades of Turkey - Guided TourDocument24 pagesShades of Turkey - Guided TourSheyanNo ratings yet

- QustuntuniaDocument3 pagesQustuntuniaShaheen AizadNo ratings yet

- Navigation in Special ConditionsDocument41 pagesNavigation in Special ConditionsoLoLoss m100% (1)

- Hub Port Potential of Marmara Region in Turkey by Network-Based ModellingDocument17 pagesHub Port Potential of Marmara Region in Turkey by Network-Based ModellingAnna SaeediNo ratings yet

- LP - TurkeyDocument13 pagesLP - TurkeyVigneswaranNo ratings yet

- IstanbulDocument20 pagesIstanbulYağmur AysudaNo ratings yet

- H7Document3 pagesH7Punky BrewsterNo ratings yet

- Selling Building Partnerships 7th Edition Weitz Test BankDocument25 pagesSelling Building Partnerships 7th Edition Weitz Test BankPatrickJohnsonepad100% (45)

- Komatsu Wheel Loader Wa900 8r Shop Manual Sen06750 04 2020Document22 pagesKomatsu Wheel Loader Wa900 8r Shop Manual Sen06750 04 2020brianwong090198pni100% (16)

- 2009 Present Marmaray Tunnel Project 1Document29 pages2009 Present Marmaray Tunnel Project 1demirmesut7575No ratings yet

- EERI Sozen Oral History ONLINEDocument129 pagesEERI Sozen Oral History ONLINEMustafa KutanisNo ratings yet

- Vdoc - Pub - Midnight at The Pera Palace The Birth of Modern IstanbulDocument401 pagesVdoc - Pub - Midnight at The Pera Palace The Birth of Modern IstanbulBhuvana K Gowda100% (1)

- Dơnload Rimward Stars Castle Federation 05 Glynn Stewart Et El Full ChapterDocument24 pagesDơnload Rimward Stars Castle Federation 05 Glynn Stewart Et El Full Chaptermacolajuong100% (5)

- The Muslim Empires: How Do Muslims Celebrate Their Beliefs?Document26 pagesThe Muslim Empires: How Do Muslims Celebrate Their Beliefs?Joseph N. Lewis Jr100% (1)

- ACCOBAMS ConservingWDP Web-EditDocument164 pagesACCOBAMS ConservingWDP Web-EditMarcela MaregaNo ratings yet

- GK & CA & Essays by Tahir HabibDocument150 pagesGK & CA & Essays by Tahir HabibTahir HabibNo ratings yet

- Fires Bulletin 2021-1-3Document48 pagesFires Bulletin 2021-1-3Egberto da SilvaNo ratings yet

- Part 3: Test Yourself: I. Find The Word Which Has A Different Sound in The Underlined PartDocument7 pagesPart 3: Test Yourself: I. Find The Word Which Has A Different Sound in The Underlined PartHAnhh TrầnnNo ratings yet