Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Adaptability

Adaptability

Uploaded by

Jaya BhasinOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Adaptability

Adaptability

Uploaded by

Jaya BhasinCopyright:

Available Formats

Article

Policy Futures in Education

Internationalisation of higher 0(0) 1–20

! Author(s) 2016

education: Conceptualising the Reprints and permissions:

sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav

antecedents and outcomes DOI: 10.1177/1478210316645017

pfe.sagepub.com

of cross-cultural adaptation

Azadeh Shafaei

School of Educational Studies, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Malaysia

Nordin Abd Razak

School of Educational Studies, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Malaysia

Abstract

The increase in higher education internationalisation has called for finding possible ways to

understand and improve its related issues. Despite the financial, cultural, and social benefits

that international students bring to host countries’ educational institutions, the challenges they

encounter in a new environment are hard to deal with, especially acculturative stress and

adjustment problems in a new environment. As international students are at the heart of

education internationalisation, it is crucial to understand and address their adjustment issues

for a sustainable education management. Therefore, this study develops a conceptual

framework to portray international students’ adjustment issues in a host country from

perspectives of field theory and cross-cultural adaptation theory. The proposed conceptual

model not only considers factors influencing international students’ cross-cultural adaptation in

a host country, but it also highlights the outcomes of such adaptation which can provide

managerial implications for sustaining higher education mobility growth.

Keywords

Conceptual framework, cross-cultural adaptation, internationalisation of higher education,

psychological adaptation, sociocultural adaptation, strategic institutional management of

internationalisation

Introduction: towards developing a conceptual framework

Internationalisation of higher education refers to the integration process of international/

intercultural dimension into the teaching, research, and service functions of an institution

Corresponding author:

Azadeh Shafaei, School of Educational Studies, Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM), 11800 Penang, Malaysia.

Email: Azadeh.shafaei@gmail.com

Downloaded from pfe.sagepub.com by guest on April 28, 2016

2 Policy Futures in Education 0(0)

(Knight, 1993). This process among higher education services emerged in the early 1990s and

has dramatically increased till present (Terry, 2011). Higher education services have pushed

the territorial boundaries away with the advent of globalisation, advancement in

information technology, and increase in international travel (Arokiasamy, 2010). At the

heart of higher education internationalisation lies cross-border student movement, which

can foster global competition among educational institutions (Marginson and Van Der

Wende, 2007). The number of students pursuing their education in a country outside their

home country (i.e. international students) was 1.75 million in 1999 which raised to nearly 3

million in 2007, according to a report by World Trade Organization (2010). Additionally,

Gürüz (2008) reported that the overall number of students enrolled in various disciplines in

educational institutions outside their home country was about 3 million, which is expected to

increase to almost 6 million by 2020 and 8 million by 2025.

The trend shows that a substantial factor for higher education institutions’ success in the

global education competition is recruiting a growing number of foreign (or international)

students (Qiang, 2003). Universities and educational institutions around the world strive to

boost their reputation in order to attract more international students and increase their share

of education market (Mayo, 2009). As such, higher education globalisation has become a

prevalent market for both developed and developing countries especially in Asia

(Arokiasamy, 2010). It is worth noting that international movement of students to other

countries for the purpose of pursuing education can be a considerable source of business,

and economic growth for host countries (Marginson, 2006). For instance, international

students through their expenditures on food, housing, books, and tuition fees can bring

additional revenue for universities and local communities.

Along with the economic growth, higher education internationalisation can result in

social, and cultural benefits for host countries (Dobson and Hölttä, 2001; Terry, 2011).

By sharing a wide variety of perspectives and views, international students can contribute

to host countries’ social and cultural diversity (Zeszotarski, 2001). These benefits have

stimulated educational institutions around the world to compete for growing their

countries’ economy by focusing on producing knowledge and moving towards higher

education internationalisation (Arokiasamy, 2010; Wilkins, 2014). Although this is the

case, it is crucial to emphasise and consider the essential role of international students’

successful transition to a new cultural environment (or cross-cultural adaptation)

(Lamprianou and Sunker, 2014). This is the prerequisite for higher education institutions

in order to attract more international students, achieve prosperity, and remain reputable in

the global education market.

Transition to higher education in an unfamiliar cultural environment is an unavoidable

cause of anxiety and unease for international students irrespective of social class or other

categorisations (Clayton et al., 2009). As highlighted by Berry (2006), cultural differences

and rigorous academic work are the potential causes of pressure and frustration that

international students experience. Perhaps, insufficient knowledge and lack of

understanding about the values and norms of the new culture together with cultural gap

between international students’ ethnic and host countries could result in stress and anxiety

for international students (Yang and Clum, 1994). This can result in negative consequences

for both individuals and host society (Sumer, 2009). Apart from cultural, social, and

financial contributions of international students to host countries, challenges they face in

a host country might lead them towards frustration and social problems (Sumer, 2009).

Therefore, by overcoming their difficulties and problems, international students can

Downloaded from pfe.sagepub.com by guest on April 28, 2016

Shafaei and Abd Razak 3

experience ‘successful transition’ (i.e. adapt) to a new environment, which can prevent

adversity and its negative impacts from host societies (Earley and Ang, 2003; Molinsky,

2007). Since international students’ cross-cultural adaptation to a new environment can

directly influence their psychological and social well-being, it is essential to be prioritised.

To this end, the issue of cross-cultural adaptation has engaged many researchers from

various contexts (Berry and Sabatier, 2010; Demes and Geeraert, 2014; Jibeen and Khalid,

2010; Masgoret, 2006; Ward and Kennedy, 1994). Accordingly, several acculturation models

have been proposed in an attempt to portray individuals’ adaptation as well as the factors

contributing to this process. For instance, Ward et al. (2001) proposed the ABCs of the

acculturation process by emphasising stress and coping framework, cultural learning

approach, and social identification theories concerning with affective, behavioural, or

cognitive aspects of individuals’ adjustment. Berry (2006) first developed the stress and

coping framework to explain the factors influencing cross-cultural adaptation.

Furthermore, distinction between the two facets of adaptation (i.e. psychological and

sociocultural adaptations) was suggested by Ward and colleagues (Searle and Ward, 1990;

Ward and Kennedy, 1992). In their framework, the aspects of stress and coping, cultural

learning, and social identification from Berry’s (2006) framework were integrated along with

an emphasis on social and cultural specific skills, which help individuals in adjustment

process. Moreover, in line with the frameworks proposed by Berry (2006) and Ward et al.

(2001), Arends-Toth and Van de Vijver (2006) and Safdar et al. (2003) developed

comprehensive models where they incorporated the mentioned three theories to explain

individuals’ acculturation. In the model developed by Arends-Toth and Van de Vijver

(2006), and Safdar et al. (2003), the aspects of individuals’ characteristics, and host

society’s characteristics, as well as hassle predictors were highlighted; however, the

framework developed by Arends-Toth and Van de Vijver (2006) had an extra element of

the society of origin’s characteristics. Similarly, both of the mentioned models, focused on

psychological and sociocultural adaptations as the consequences of adjustment and

acculturation attitude as the predictor linking the antecedents and outcomes.

Although the above-mentioned models proposed some antecedents for cross-cultural

adaptation that might be relevant to international students, there is a necessity to focus

specifically on international students and consider factors with aspects of cognition,

behaviour and perception (Smith and Khawaja, 2011). Particularly, with the increase in

international mobility in higher education, there is not a specific conceptual framework to

understand and address international students’ needs in a new environment. Although the

extant literature suggests several individual (personal) factors and situational

(environmental) factors that assist individuals to achieve successful adaptation in a new

environment, still there is a need to identify situational (environmental) factors specifically

for the context of international students (Smith and Khawaja, 2011). This can enrich

understanding towards international students’ cross-cultural adaptation. Since the above-

mentioned models were not developed precisely for the context of international students, the

proposed outcomes of cross-cultural adaptation in these models are limited. This limitation

signals that further investigation is required to suggest specific outcomes in the context of

international students because they play crucial roles in sustaining higher education growth.

Additionally, the extant literature mainly considers the perspectives of organisations and

educational institutions in improving policies (e.g., Bartell, 2003; Knight, 2004; Qiang, 2003).

The uni-dimensional assessment for policy improvement, which is based on educational

institutions’ viewpoint, may not account for the needs of their main customers

Downloaded from pfe.sagepub.com by guest on April 28, 2016

4 Policy Futures in Education 0(0)

(international students). Overlooking international students’ perspectives and requirements

in designing and improving policies may impede educational institutions from reaching their

goal of becoming reputable education service providers in the global education market. Since

international students are at the core of international education mobility and considered as

the main customers of global education sector, it is paramount to pay attention to their

needs, and take into account their perspectives in improving policies and practices. This

approach could benefit both educational institutions and international students to achieve

prosperity and success. It is the aim of this paper to bridge this gap in the literature by

proposing an alternative conceptual model which is based on international students’ cross-

cultural adaptation needs.

Furthermore, prior acculturation models in the literature are rooted in three renowned

theories: (a) stress and coping theory (SCT); (b) culture learning theory (CLT); and (c) social

identification theories (SIT). These theories elaborate ‘Affective’, ‘Behavioural’ and

‘Cognitive’ aspects individuals’ adaptation process to a new cultural environment

respectively (Zhou et al., 2008). However, despite providing insightful support, ‘field

theory’ (Lewin, 1951) and ‘cross-cultural adaptation theory’ (Kim, 2001) have not been

applied to explain individuals’ adaptive behaviours and cross-cultural adaptation to a new

environment. The main rationale for integrating field theory and cross-cultural adaptation

theory and using them as the governing theories in this paper is that these two theories can

explain the nexus of antecedents–adaptation–outcomes with the emphasis on cognition.

Moreover, field theory by focusing on the equation of behaviour as the function of a

person and the environment (B ¼ P, E) makes it possible to divide the antecedents of

cross-cultural adaptation into individual and situational factors. In addition, using cross-

cultural adaptation theory offers support for investigation of the outcomes of cross-cultural

adaptation that can provide managerial and practical contributions to education

policymakers and authorities in higher education.

Thus, it is the aim of this study to present an alternative conceptual framework that

considers both wide and narrow perspectives in explaining international students’

adaptation process based on field theory and cross-cultural adaptation theory. Then, a

conceptual model in consensus with the prior models, but extended from them is

developed to be applied in exploring international students’ adaptation and its outcomes

in a new cultural environment. This can be beneficial to higher education institutions. The

proposed framework focuses on international students, those who pursue higher education

in a country outside their home country. The framework also examines antecedents and

outcomes of international students’ cross-cultural adaptation. The proposed model can be

employed by emerging countries competing towards higher education internationalisation

through attracting more international students. The following sub-sections elaborate the

notion of cross-cultural adaptation from the lens of field theory and cross-cultural

adaptation theory.

Cross-cultural adaptation

Generally, the dynamic change process that happens to individuals upon their relocation to a

new environment is defined as cross-cultural adaptation (Kim, 1988, 2001). Three main

facets namely functional fitness, psychological health, and intercultural identity

development are involved in cross-cultural adaptation. However, Kim (1990) only

considered functional fitness and psychological health (Wang and Sun, 2009). In line with

Downloaded from pfe.sagepub.com by guest on April 28, 2016

Shafaei and Abd Razak 5

Kim’s definition, Beiser et al. (1988) defined cross-cultural adaptation as the changes that

take place during acculturation. Two types of changes were outlined as ‘short-term’ and

‘long-term’ changes. Specifically, the former would be sometimes negative, whereas the latter

would be mostly positive, resulting in adaptation. Berry (1997) in response to Beiser et al.

(1988) claimed that the long-term changes could highly vary ranging from poorly adapted to

well-adapted. In addition, Aycan and Berry (1995) proposed a similar definition for cross-

cultural adaptation as Kim’s definition by focusing on the dynamic change process and the

three facets of cross-cultural adaptation.

Meanwhile, Ward and colleagues proposed a definition for cross-cultural adaptation in

line with Kim’s definition. They stated that when individuals move to a new environment,

the dynamic process of change causes individuals to adapt both psychologically and

socioculturally to the new society (Searle and Ward, 1990; Ward, 1996; Ward and

Kennedy, 1993a). Therefore, they formulated the two key concepts of psychological

adaptation and sociocultural adaptation into cross-cultural adaptation. In fact, the terms

psychological adaptation and sociocultural adaptation concur respectively with

psychological health, and functional fitness suggested by Kim (Wang and Sun, 2009).

Cross-cultural adaptation from the lens of field theory

Rooted in social psychology, field theory was developed by Lewin (1951) to overcome the

limitations of traditional way of thinking through merely psychology (Atkinson, 1964).

Through his broad system of topological concept, Lewin represented the idea of

encompassing emotions, values, thoughts, social relationships, and behaviours through

psychological situations (Chak, 2002). Therefore, he formulated his field theory to explain

human’s behaviour from the perspective of social psychology by stating a person’s behaviour

is related to his/her personal characteristics as well as the social situation in which he/she

finds him/herself (Lewin, 1951).

In particular, field theory focuses on humans’ actions as a result of their behaviour, which

occurs in a ‘force field’. Field is defined as mutually interdependent coexisting facts or forces

which represent different aspects of an individual’s coexisting environment. In other words,

humans are influenced by surrounding factors in the field. These factors could determine

individuals’ behaviour. Thus, behaviours occur as the result of various interactions in the

field and between the fields of other individuals (Neill, 2004). Every individual possesses a

field and since individuals have a lot of differences, their fields are different from each other.

As individuals gain more information and knowledge about the environment, their field

changes to accommodate them (Cronshaw and McCulloch, 2008).

Moreover, Lewin stated that a person’s behaviours occur within a psychological field,

which is called ‘life-space’ (Schultz and Schultz, 2004). The term ‘life-space’ refers to every

force in the field both from inner and outer environment that shapes up an individual such as

the places an individual goes, the people an individual meets and the feelings an individual

has about the places or people (Lewin et al., 1944). As Lewin believed, understanding the

relations of all factors in one’s life-space is crucial because those are the elements which play

important roles in helping or blocking people from accommodating to a new environment

(Sorrentino, 2013). The equation for life-space is ‘B ¼ f (P, E)’, which indicates that

individuals’ behaviour (B) can be explained by considering both the person (P) and their

environment (E). The environment here does not refer to the physical environment, but

rather the psychological environment perceived by the person (Sorrentino, 2013).

Downloaded from pfe.sagepub.com by guest on April 28, 2016

6 Policy Futures in Education 0(0)

Additionally, the person and environment are interdependent and that creates a dynamic

and complex field of interaction which help individuals learn more about themselves and

their environment (Daniels, 2003). Therefore, Lewin (1951) regarded field as a continuous

state of adaptation.

Field theory explains the influence of several individual and situational factors on

individuals’ behaviours; however, it lacks detailed explanations and operationalisation of

individuals’ cross-cultural adaptation in a new environment. Therefore, Kim’s cross-cultural

adaptation theory is needed to precisely operationalise this notion by proposing a clear

explanation for cross-cultural adaptation process of individuals in a new environment and

its relative outcomes.

Cross-cultural adaptation theory

Kim (2001) developed an integrative theory of communication and cross-cultural adaption,

which can be considered as one of the most detailed theoretical frameworks applied in

adaptation process. At the heart of this theory lies the notion of transformation process

when an individual relocates to a new and culturally unfamiliar environment. As such, cross-

cultural adaptation is defined as a dynamic process owing to individuals’ constant

interaction with their environment in this theory (Hamad and Lee, 2013). In other words,

as individuals have to face and accept the differences between their ethnic culture and that of

the host culture, they might face challenges when entering a new environment. In facing

challenges, dynamic human nature struggles for an internal balance through acquiring new

cultural communication practices, participating actively in the interpersonal and mass

communication processes of the local community and being competent in host

communication system (Hamad and Lee, 2013). The struggle for internal balance or

stability causes all individuals to go through a transformation process, which is called

cross-cultural adaptation (Kim, 2001).

In fact, individuals are open, complex, and evolving systems that constantly search for

stability through establishing, re-establishing, and maintaining relatively stable and

functional relationships with their new environment (Kim, 2005). In addition, Anderson

(1994) believed that the adaptation process is a continuum that can result in positive or

negative outcomes. It also involves building and rebuilding of identity since sense of self and

self-esteem of individuals can be shaken in a culturally unfamiliar environment.

Consequently, a gradual personal identity transformation occurs as a result of successful

adaptation. Although the old identity can never be completely replaced with the new one, it

can be transformed into something that will always contain some of the old and the new side

by side, to form a new perspective that allows more openness and acceptance of differences

in people (Kim, 1988, 2001).

As mentioned earlier, the two facets of cross-cultural adaptation proposed by Kim

correspond with the two notions of psychological (emotional/affective) adaptation and

sociocultural (behavioural) adaptation proposed by Ward and colleagues (e.g., Searle and

Ward, 1990; Ward, 1999; Ward and Kennedy, 1994). Kim’s theory can explain individuals’

adaptation phenomenon through psychological and sociocultural adaptations, and also

focus on outcomes of such adaptation (Kim, 2001). Therefore, it is applied in the

proposed conceptual framework in this paper. The integration of the two mentioned

theories can provide a better understanding of cross-cultural adaptation from a

theoretical perspective.

Downloaded from pfe.sagepub.com by guest on April 28, 2016

Shafaei and Abd Razak 7

The proposed conceptual framework

The proposed conceptual framework in this paper is mainly formulated based on field theory

and cross-cultural adaptation theory. Both of these theories provide support by emphasising

the important role of several individual and situational factors in facilitating international

students’ adaptive behaviours [field theory] and their constant search for achieving stability

or equilibrium [field theory and cross-cultural adaptation theory] which results in cross-

cultural adaptation and its outcomes [cross-cultural adaptation theory]. As antecedents

and outcomes of adaptation are equally important, integration of field and cross-cultural

adaptation theories complement each other in providing a platform to explore the factors

contributing to international students’ cross-cultural adaptation, and its outcomes in a new

environment (i.e. the nexus of antecedents–adaptation–outcomes).

In particular, field theory emphasises on life-space as a perceived psychological

environment that involves both inner and outer factors influencing adaptive behaviours of

individuals. Inner and outer factors are conceptualised as the psychological environment

that international students perceive from their inner and outer environment in field theory.

Therefore, perception and cognition are crucial to shape up international students’ adaptive

behaviours in a new society (Sorrentino, 2013). Additionally, the inner and outer factors are

operationalised, respectively, as individual/personal and environmental/situational factors in

the field theory. Perception, cognition, and attitude play vital roles in individuals’ adaptation

process (Tajfel, 1981). Besides, it is essential to find out factors that take into account aspects

of cognition, behaviour, and psychology in the setting of international students (Smith and

Khawaja, 2011). As such, field theory can greatly contribute in designing and developing the

conceptual framework in this paper.

Since field theory incorporates the components of psychology, cognition, and

behaviour, it allows for identifying both individual (inner) and situational (outer) factors

contributing to international students’ adaptation from a theoretically sound perspective.

Although in the above-mentioned models both personal characteristics and society

characteristics (i.e. host and ethnic) have been considered as the antecedents of

adaptation process, the specification of these factors considering international students is

yet to be explored (Smith and Khawaja, 2011). Hence, the current conceptual framework

is proposed to address the existing gap in the literature of international students by

employing field theory and cross-cultural adaptation theory to open up new directions

for further studies.

Although field theory provides support for developing the conceptual framework in this

paper, crucial role of cross-cultural adaptation theory is undeniable. In line with the prior

models, two key notions of psychological and sociocultural adaptations (Searle and Ward,

1990; Ward, 1999; Ward and Kennedy, 1994) assist to understand the process of

international students’ cross-cultural adaptation. According to cross-cultural adaptation

theory, successful cross-cultural adaptation can result in several outcomes (Wang and

Sun, 2009). This aspect of cross-cultural adaptation theory allows to identify several

outcomes relevant to the setting of international students and how the identified outcomes

could contribute to the sustainability and success of higher education. As outcomes of

international students’ adaptation are as important as the antecedents influencing this

process, cross-cultural adaptation theory is employed along with field theory to build the

proposed conceptual framework in this paper. Table 1 summarises the explanation of field

theory and cross-cultural adaptation theory as well as their contributions to the proposed

conceptual framework.

Downloaded from pfe.sagepub.com by guest on April 28, 2016

8 Policy Futures in Education 0(0)

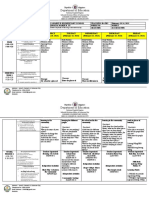

Table 1. Summary of the field theory and cross-cultural adaptation theory.

Contribution to the

Theory Explanation proposed framework

Field Theory Every individual possesses a field (life - Several individual and situational

space) (Schultz and Schultz, 2004). factors influence a person’s

- The field is the perceived environment behaviour

of individuals (Sorrentino, 2013). - Constant interaction of individuals

- Co-existing forces in the field form with their environment

individual behaviours (Cronshaw and - Individuals’ continuous search for

McCulloch, 2008). equilibrium

- Life space equation is B ¼ F (P, E) - Behaviour is the function of the

which constitute all the inner and person and environment

outer forces in forming individuals’

behaviour (Sorrentino, 2013).

- Individual and situational factors

influence a person’s behaviour in the

environment (Chak, 2002).

-Individuals’ constant interaction with

the environment causes continuous

change in order to achieve

equilibrium (Daniels, 2003).

Cross-Cultural - Sojourners face challenges in a new - Sojourners face challenges in a new

Adaptation Theory environment (Kim, 2001). and culturally unfamiliar

- Sojourners try to overcome their environment.

difficulties by acquiring some skills - Sojourners’ search for stability leads

and interaction with their new them to adaptation.

environment (Hamad and Lee, - Influence of various factors on

2013). sojourners’ cross-cultural

- Several factors make individuals adaptation.

change while seeking for stability - Continuous interaction between the

(Kim and Gudykunst, 1988). individuals and their new

- Sojourners’ constant search for environment.

stability in a new environment leads - Cross-cultural adaptation consists of

them to cross-cultural adaptation psychological and sociocultural

(Kim, 2005). adaptation.

- Adaptation is a dynamic process and it - Positive outcomes of successful

has three facets which coincide with adaptation.

the two concepts of psychological

and sociocultural adaptation (Wang

and Sun, 2009).

- Positive results will be achieved by

successful adaptation (Kim, 2001).

The two mentioned theories explain international students’ cross-cultural adaptation to a

new environment, and the antecedents (i.e. individual and situational factors) and outcomes

of such adaptation. However, field theory and cross-cultural adaptation theory do not

specify individual and situational factors in adaptation process. As such, to draw

potential individual and situational factors that influence psychological and sociocultural

Downloaded from pfe.sagepub.com by guest on April 28, 2016

Shafaei and Abd Razak 9

Figure 1. Proposed conceptual framework.

adaptations, this paper, similar to prior models in the literature, adopts stress and coping

theory (SCT), culture learning theory (CLT), and social identification theories (SIT). These

three theories can provide a comprehensive, broad and conceptual basis for intercultural

contact and change studies (Ward et al., 2001). Nonetheless, classification and identification

of the suggested factors by SCT, CLT, and SIT into individual and situational factors is

carried out from the perspective of field theory in this paper. Figure 1 depicts the proposed

conceptual framework.

The ‘‘ABC’’ theories

Stress and coping theory

In stress and coping theory, Lazarus and Folkman (1984) focus on the idea that various

phenomena can be understood through an organising concept of ‘stress’. Therefore,

psychological stress is defined as ‘a particular relationship between a person and the

environment that is appraised by the person as exceeding his or her resources and

endangering his or her well-being’ (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984: 19). In fact, appraisal

processes determine whether a situation is stressful or not (Schuster et al., 2003). In

particular, the stress process is shaped up by the relationship between stimulus and

individuals’ response where they try to evaluate and cope with it. In addition, difficulties

and challenges faced by individuals in a new environment cause a lot of stress for individuals

and the way they manage these challenges is defined as coping process (Decker and Borgen,

1993). Consequently, there is a need to engage people in cross-cultural encounters to make

them resilient, adapt, and develop coping strategies and tactics (Aldwin, 1994; Lazarus,

1990).

Culture learning theory

Culture learning theory emphasises the behavioural aspect of intercultural contact and

highlights the role of social interaction as a skilled behavioural performance (Argyle,

1969). Lack of social skills and having difficulties in dealing with daily life interactions

such as norms, rules, values, as well as verbal and non-verbal communication owing to

Downloaded from pfe.sagepub.com by guest on April 28, 2016

10 Policy Futures in Education 0(0)

cross-cultural differences are the main causes of stress for individuals in a new environment

(Masgoret and Ward, 2006). Inasmuch as cultural differences make adaptation process

difficult, culture learning theory concentrates on finding ways to diminish intercultural

misunderstandings. Thus, having connections with host nationals is pivotal for individuals

according to this theory. This is because through interactions with host nationals,

individuals can learn a series of culturally relevant skills in order to enhance their

psychological and social success (Furnham, 2004).

Social identification theories

Based on theories of social cognition and social identity (Tajfel and Turner, 1986), the

cognitive aspect of intercultural contact is mainly focused. In particular, individuals’

ethnical and cultural identification of themselves and the ways they interact with in and

out groups is crucial. The ways individuals perceive their cultural identity and the

relationships they have with co-nationals and host nationals can significantly impact their

adaptation process. The notions of cognitive, mental and internal processes such as

attitudes, perceptions, expectations, and values (Ward et al., 2001) are the core elements

of this theory. Hence, two major concepts, namely acculturation and social identity theory,

are associated with social identification theories (Phinney, 1990).

Overall, the detailed investigation and examination of the individual and situational

factors that influence psychological and sociocultural adaptations of international

students require incorporation of SCT, CLT, and SIT since they offer a comprehensive,

longitudinal, dynamic, and systemic domain for examination of the influence of different

variables on cross-cultural adaptation (Zhou et al., 2008). Table 2 illustrates the factors

proposed by SCT, CLT and SIT in the literature. These factors have been grouped as

individual and situational factors in this paper.

Figure 2 shows the proposed conceptual model in the context of international students

which has the potential to be explored and studied to shed some light on the issue of

international students’ cross-cultural adaptation and its outcomes.

The proposed conceptual model incorporates two governing theories, namely field theory

and cross-cultural adaptation theory in order to explain the nexus of antecedents–

adaptation–outcomes. For the variables derivation, SCT, CLT, and SIT are employed.

Specifically, the proposed framework aims to make a connection between individual and

situational factors with cross-cultural adaptation of international students. It also intends to

link international students’ cross-cultural adaptation to their perceived academic

satisfaction. As satisfaction is an important outcome of the balance between

characteristics of a person and the environment (i.e. adaptation), in the context of

international students, academic satisfaction, which refers to how satisfied international

students are with their overall academic performance in a host country, is pivotal to be

considered (Goštautaite_ and Bučiuniene_, 2010). Moreover, the evidence shows that positive

word of mouth resulted from good academic experience can increase the number of

international students in host countries (Cheng et al., 2013).

Concluding remarks

As international students are at the core of international mobility in higher education, it is

crucial to understand the issues they encounter in a new environment. This could pave the

Downloaded from pfe.sagepub.com by guest on April 28, 2016

Table 2. Proposed factors by SCT, CLT and SIT.

Individual and situational factors

Shafaei and Abd Razak

Theory Individual factors Situational factors proposed in the study

Stress and Coping Theory (SCT) Degree of life change (Lin et al., 1979), Social support (Adelman, 1988; Lewis Situational Factors

personality factors, coping strategies Hall et al., 2006) -Social support

(Bardi and Ryff, 2007; Ward and

Kennedy, 1994)

Culture Learning Theory (CLT) General knowledge about a new culture Cultural distance (Ward and Kennedy, Individual Factors:

(Ward and Searle, 1991), length of 1993a, 1993b), especially cultural - Language Proficiency

residence in the host culture (Ward, differences of norms, values, verbal and - Media Usage

et al. 1998), language or non-verbal communication (Masgoret - Intention to Stay in a Country

communication competence (Furnham, and Ward, 2006) outside the Home Country

1993), quantity and quality of contact after Graduation

with host nationals (Bochner, 1982), Situational Factors:

friendship networks (Bochner et al., - Perceived complexity

1977), temporary versus permanent

residence in a new country (Ward and

Downloaded from pfe.sagepub.com by guest on April 28, 2016

Kennedy, 1993a)

Social Identification Theories (SIT) Cultural identity, intergroup attitudes Existence of prejudice and discrimination, Individual Factors:

(Ward and Searle, 1991), and and cultural diversity in a society (Ward - Acculturation attitude

acculturation modes (Ward and et al., 2001), perceived prejudice and Situational Factors:

Kennedy, 1994) discrimination during their interaction - Perceived stereotype image

with host nationals (Sodowsky and

Plake, 1992) which forms a negative

inter-group stereotypes over time

(Stroebe et al.,1988)

11

12 Policy Futures in Education 0(0)

Figure 2. Conceptual model.

way for higher education institutions to achieve success and attract more international

students. The main reason is when international students are able to accommodate

themselves in a host country, the possibility of achieving academic satisfaction would be

higher (Kulik et al., 1987) that can lead to positive word of mouth in promoting higher

education institutions to others. As mentioned by Rust and Oliver (2000) satisfaction is a

remarkable motivator for speaking well about services. Therefore, students’ satisfaction

should be at the centre of every education policy (Mark, 2013).

Despite the profound properties of field theory and cross-cultural adaptation theory,

literature has provided little insights into the area of cross-cultural adaptation through

these two theoretical perspectives. Therefore, the current paper built on the existing

lacuna by designing a conceptual framework on the basis of field theory and cross-

cultural adaptation theory that can explain international students’ cross-cultural

adaptation, its antecedents, and outcomes in a new context.

The conceptual framework developed in this paper proposed a model in the area of cross-

cultural adaptation of international students. The conceptual model is consistent, but

extended from the prior models (Arends-Toth and Van de Vijver, 2006; Berry, 2006;

Safdar et al., 2003; Ward et al., 2001) with specific focus on international students.

Similar to the earlier models, SCT, CLT, and SIT are applied in the proposed conceptual

framework. In contrast with the earlier models that were mainly developed to tackle the

issues of migrants’ and refugees’ acculturation process, the current paper proposed a

conceptual framework and model to target international students and look at their cross-

cultural adaptation’ antecedents and outcomes from the lens of field theory and cross-

cultural adaptation theory. Furthermore, the previous models in the literature considered

psychological and sociocultural adaptations as the outcomes of acculturation. However, in

the proposed conceptual model in this paper, outcomes of adaptation refer to the other

factors resulting from successful achievement of psychological and sociocultural

Downloaded from pfe.sagepub.com by guest on April 28, 2016

Shafaei and Abd Razak 13

adaptations. Hence, the implications of this paper that make it distinguishable from the

previous studies are outlined as the following.

Implications to theory

Building upon field theory helps to view the individual (inner) and situational (outer) factors

influencing international students’ adaptive behaviours in a new environment from different

viewpoints. Moreover, field theory makes it possible to identify antecedents of cross-cultural

adaptation with cognitive aspects since the key role of perception is emphasised in this

theory. As cognition plays a vital role in adjustment process (Tajfel, 1981), international

students’ perceptions of their new psychological environment in a new culture is essential to

understand their adaptation. This is a missing link in the extant literature. Field theory’s

contribution to the proposed conceptual framework in this paper led to identifying some

important factors to bridge the existing gap in the literature on international students’ cross-

cultural adaptation. Moreover, by integrating field theory and cross-cultural adaptation

theory both antecedents and outcomes of cross-cultural adaptation are taken into

account. Unlike the previous models, employing cross-cultural adaptation theory in this

paper helps to go beyond the existing models by suggesting several outcomes rather than

merely focusing on psychological and sociocultural adaptations as the outcomes.

Thus, the conceptual framework proposed in this study takes a different approach and

looks at internationalisation of higher education from a new angle by placing international

students at the heart of this phenomenon and suggests a channel through which both

international students and host countries’ educational institutions can prosper and benefit.

Overall, this study is distinctive owing to several reasons: first, systematic classification of

the antecedents into individual and situational factors is in accordance with field theory

which emphasises the role of perception and cognition. Second, since international

students are the target group for developing the conceptual framework, more context-

specific outcomes (i.e. perceived academic satisfaction and positive word of mouth)

related to this group are suggested. Last, the conceptual framework developed in this

paper has the potential to be studied and examined empirically in relation with

international students’ cross-cultural adaptation and it can open up new horizons in the

area of higher education mobility.

Implications to research

As mentioned by Smith and Khawaja (2011), there is a need to develop a model specifically

for the context of international students because the current models primarily concentrate on

refugees and migrants. Besides, there is a gap in the literature regarding the identification of

individual and situational factors contributing to international students’ adaptation with

cognition, psychology, and behaviour components. Therefore, the proposed conceptual

model in this paper requires further empirical scrutiny concerning international students.

Future research should test each identified antecedents proposed in the model in relation

with psychological and sociocultural adaptations. The proposed model should be empirically

tested in various contexts on international students who move to a new country for the

purpose of pursuing their higher education. In particular, the relationships among the

variables in the proposed conceptual framework can be tested quantitatively using

questionnaires in order to get insights from a large number of international students. It is

Downloaded from pfe.sagepub.com by guest on April 28, 2016

14 Policy Futures in Education 0(0)

suggested that Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) technique could be applied for data

analysis since SEM provides an appropriate and the most efficient estimation technique for a

series of separate multiple regression equations to be estimated simultaneously. Moreover,

SEM incorporates multi-item scales in the analysis and accounts for the measurement error

associated with each of the scales (Hair et al., 2010). SEM as a second generation data

analysis technique provides a platform to model multiple independent and dependent

constructs’ relationships simultaneously and enables researchers to answer interrelated

research questions through a comprehensive, systematic, and single analysis (Gefen et al.,

2000). Since the proposed model in this paper is exploratory in nature (i.e. the relationships

among the variables in the model have not been tested before), Partial Least Squares

technique (PLS-SEM) is deemed appropriate to be employed.

The proposed conceptual model could be tested in various contexts using sample of

international students from different backgrounds. Owing to social, cultural, and

educational discrepancies that exist among international students, it would be insightful to

empirically examine the model in different contexts. It could also be informative to separate

international students based on geographical regions they come from and identify specific

factors which could facilitate their cross-cultural adaptation. Additionally, length of stay in a

host country, friendship network, and field of study could be assessed in the proposed

conceptual model to portray a detailed picture of international students’ needs in a host

country. It is also suggested to test the model for both private and public educational

institutions in order to compare and contrast their effective policies and practices

concerning international students. Through employing various statistical tests, more

interpretation of the relationships in the proposed model could be achieved.

Furthermore, with the strong support from theories mentioned in this paper, more

antecedents of psychological and sociocultural adaptations can be explored and

incorporated into the proposed model with regards to international students. It is also

crucial to identify and examine other outcomes of psychological and sociocultural

adaptations in the context of international students, since it could contribute to the

growth of higher education mobility.

Implications to higher education

This paper provides strategic managerial insights for academicians, education policymakers,

and university administrators of the emerging countries that compete to attract more

international students. Given the impact of internationalisation of higher education and

the competition among new players in the global education market to attract more

international students, positive word of mouth is essential to bring more international

students to host country’s educational institutions. Mainly for the new players in the

market that are competing with well-established educational institutions, it is substantial

to build a good reputation which can convey a positive image to customers and stakeholders

of an organisation. Positive reputation can be a basis for competitive advantage that can

help an organisation attract and retain customers (Thomaz, 2010). As such, it is timely for

emerging countries to boost their educational institutions’ good reputation in order to

remain competitive in the global education market. Higher education institutions should

prioritise international students’ adaptation issues. This not only ensures successful

transition of international students, but also assists new players to attract more

international students through their existing customers’ positive word of mouth.

Downloaded from pfe.sagepub.com by guest on April 28, 2016

Shafaei and Abd Razak 15

International

Students' Cross-

Individual Factors Cultural Situational Factors

Adaptation

Increase in the Perceived

Number of Academic

International Satisfaction

Students

Positive Word

of Mouth in

Recommending

Host Countries'

Educationsl

Institutions

Figure 3. Managerial contribution of the proposed conceptual model.

Since most of the conceptual frameworks in the area of education internationalisation

consider educational institutions and organisations’ perspectives in handling and addressing

the issues involved in international students’ mobility, this study helps higher education

authorities to view the phenomenon of higher education internationalisation from a

different angle. This proposed approach offers new path through which international

students’ psychological and sociocultural needs are taken into consideration as well as

their positive outcomes which could contribute to higher education management and

improvement in host countries. In particular, international students’ successful cross-

cultural adaptation can lead to higher academic satisfaction which would result in positive

word of mouth in promoting host countries’ educational institutions to others. In addition,

by empirically implementing the proposed model, higher education institutions especially the

new players in the global education market can devise suitable human capital management

strategies tailored for meeting specific needs of international students. Figure 3 depicts the

implications of this study to higher education.

This is an alternative marketing strategy for emerging countries. By meeting and

addressing international students’ needs, higher education institutions can enhance their

international students’ academic satisfaction and willingness to promote host country’s

educational institutions to others through positive word of mouth. In the process of

marketing education services, it is essential to consider the receivers’ wants and needs

(Schofield et al., 2013). Given that the process of internationalisation is cyclical (Qiang,

2003), further planning and reforming of the existing programmes and policies contribute

to the refinement of higher education internationalisation cycle and ensure sustainability of

higher education mobility.

In moving towards internationalisation of higher education and its growth, the issue of

cross-cultural adaptation, which is the main source of stress and anxiety for the international

students, should be understood and addressed well by education policymakers and

Downloaded from pfe.sagepub.com by guest on April 28, 2016

16 Policy Futures in Education 0(0)

academicians. As proposed in this paper, international students’ successful cross-cultural

adaptation, known as ‘successful transition’, can lead to satisfaction with their academic

performance which can ultimately result in positive word of mouth in promoting host

country’s educational institutions to others. As such, it is suggested to higher education

institutions to apply the proposed model for their existing students in order to find out

the areas which require more attention and refinement. The results can then be translated

into tactics and strategies for prospective students. In fact, this is a never ending process

which can stimulate higher education institutions’ progressive transformation towards

excellence. By developing a conceptual model, this paper offers an alternative path to

propel competing countries towards education internationalisation, and transforming their

higher education to a centre of excellence through attracting more international students.

The alternative channel suggested in this paper not only tackles the issues of international

students’ adaptation, but it also helps competing countries grow and sustain their higher

education market.

This paper is not being considered concurrently for publication elsewhere nor has it been

published in any language before. All the authors have contributed significantly and are in

agreement with the content of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The first author is a recipient of USM Global Fellowship. The authors also acknowledge the support of

Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM) through Research University Grant (Grant Number: 1001/PGURU/

816267).

References

Adelman MB (1988) Cross-cultural adjustment: A theoretical perspective on social support.

International Journal of Intercultural Relations 12(3): 183–204.

Aldwin C (1994) Stress, Coping and Development. New York: Guilford Press.

Anderson LE (1994) A new look at an old construct: Cross-cultural adaptation. International Journal

of Intercultural Relations 18(3): 293–328.

Arends-Toth J and Van de Vijver FJR (2006) Issues in the conceptualization and assessment of

acculturation. In: Bornstein MH and Cote LR (eds) Acculturation and Parent–Child

Relationships: Measurement and Development. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates,

pp.33–62.

Argyle M (1969) Social Interaction. London: Methuen.

Arokiasamy ARA (2010) The impact of globalization on higher education in Malaysia. Available at:

http://www.nyu.edu/classes/keefer/waoe/aroka.pdf (accessed 20 January 2015).

Atkinson JW (1964) An Introduction to Motivation. Princeton, NJ: Van Nostrand.

Aycan Z and Berry JW (1995) Cross-cultural adaptation as a multifaceted phenomenon. In: 4th

European congress of psychology. Athens: Greece.

Bardi A and Ryff CD (2007) Interactive effects of traits on adjustment to a life transition. Journal of

Personality 75(5): 955–984.

Bartell M (2003) Internationalization of universities: A university culture-based framework. Higher

Education 45(1): 43–70.

Beiser M, Barwick C, Berry JW, et al. (1988) Menial Health Issues Affecting Immigrants and Refugees.

Ottawa: Health and Welfare Canada.

Berry JW (1997) Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Applied Psychology 46(1): 5–34.

Downloaded from pfe.sagepub.com by guest on April 28, 2016

Shafaei and Abd Razak 17

Berry JW (2006) Stress perspectives on acculturation. In: Sam DL and Berry JW (eds) The Cambridge

Handbook of Acculturation Psychology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp.43–57.

Berry JW and Sabatier C (2010) Acculturation, discrimination, and adaptation among second

generation immigrant youth in Montreal and Paris. International Journal of Intercultural

Relations 34(3): 191–207.

Bochner S (1982) Cultures in contact: Studies in Cross-Cultural Interaction. Oxford: Pergamon Press.

Bochner S, McLeod BM and Lin A (1977) Friendship patterns of overseas students: A functional

model 1. International Journal of Psychology 12(4): 277–294.

Chak A (2002) Understanding children’s curiosity and exploration through the lenses of Lewin’s field

theory: on developing an appraisal framework. Early Child Development and Care 172(1): 77–87.

Cheng MY, Mahmood A and Yeap PF (2013) Malaysia as a regional education hub: a demand-side

analysis. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management 35(5): 523–536.

Clayton J, Crozier G and Reay D (2009) Home and away: risk, familiarity and the multiple

geographies of the higher education experience. International Studies in Sociology of Education

19(3-4): 157–174.

Cronshaw SF and McCulloch AN (2008) Reinstating the Lewinian vision: From force field analysis to

organization field assessment. Organization Development Journal 26(4): 89–103.

Daniels V (2003) Kurt Lewin notes. Available at: http://www.sonoma.edu/users/d/daniels/

lewinnotes.html (accessed 20 September 2013).

Decker PJ and Borgen FH (1993) Dimensions of work appraisal: Stress, strain, coping, job

satisfaction, and negative affectivity. Journal of Counseling Psychology 40(4): 470–478.

Demes KA and Geeraert N (2014) Measures matter scales for adaptation, cultural distance, and

acculturation orientation revisited. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 45(1): 91–109.

Dobson IR and Hölttä S (2001) The internationalisation of university education: Australia and

Finland compared. Tertiary Education & Management 7(3): 243–254.

Earley PC and Ang S (2003) Cultural Intelligence: Individual Interactions Across Cultures. Palo Alto,

CA: Stanford University Press.

Furnham A (1993) Communicating in foreign lands: The cause, consequences and cures of culture

shock. Language, Culture and Curriculum 6(1): 91–109.

Furnham A (2004) Education and culture shock. Psychologist 17(1): 16–19.

Gefen D, Straub DW and Boudreau M-C (2000) Structural equation modeling techniques and

regression: Guidelines for research practice. Communications of the Association for Information

Systems 4(1): 2–77.

Goštautaite_ B and Bučiuniene_ I (2010) Integrating job characteristics model into the person-

environment fit framework. Economics & Management 2010(15): 505–511.

Gürüz K (2008) Higher Education and International Student Mobility in the Global Knowledge

Economy. Albany: State University of: New York Press.

Hair JF, Black WC, Babin BJ, et al. (2010) Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed. New Jersey: Pearson

Prentice Hall Inc.

Hamad R and Lee CM (2013) An assessment of how length of study-abroad programs influences

cross-cultural adaptation. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment 23(5): 661–674.

Jibeen T and Khalid R (2010) Predictors of psychological well-being of Pakistani immigrants in

Toronto, Canada. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 34(5): 452–464.

Kim YY (1988) Communication and Cross-Cultural Adaptation: An Integrative Theory. Clevedon,

United Kingdom: Multilingual Matters.

Kim YY (1990) Communication and adaptation: The case of Asian Pacific refugees in the United

States. Journal of Asian Pacific Communication 1(1): 191–207.

Kim YY (2001) Becoming Intercultural: An Integrative Theory of Communication and Cross-Cultural

Adaptation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Kim YY (2005) Adapting to a new culture: An integrative communication theory. In: Gudykunst WB

(ed.) Theorizing about Intercultural Communication. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, pp.375–400.

Downloaded from pfe.sagepub.com by guest on April 28, 2016

18 Policy Futures in Education 0(0)

Kim YY and Gudykunst WB (1988) Cross-Cultural Adaptation: Current Approaches. London: Sage

Publications, Inc.

Knight J (1993) Internationalization: management strategies and issues. International Education

Magazine 9: 6–22.

Knight J (2004) Internationalization remodeled: Definition, approaches, and rationales. Journal of

Studies in International Education 8(1): 5–31.

Kulik CT, Oldham GR and Hackman JR (1987) Work design as an approach to person-environment

fit. Journal of Vocational Behavior 31(3): 278–296.

Lamprianou I and Sunker H (2014) Transition to higher education: Social and political perspectives.

Policy Futures in Education 2: 629–632.

Lazarus RS (1990) Theory-based stress measurement. Psychological Inquiry 1(1): 3–13.

Lazarus RS and Folkman S (1984) Stress, Coping and Appraisal. New York: Springer.

Lewin K (1951) In: Dorwin Cartwright D (ed). Field Theory in Social Science. New York: Harper and

Brothers.

Lewin K, Dembo T, Festinger L, et al. (1944) Level of aspiration. In: Hunt JM (ed.) Personality and

the Behavior Disorders. Oxford: Ronald Press, pp.333–378.

Lewis Hall ME, Edwards KJ and Hall TW (2006) The role of spiritual and psychological development

in the cross-cultural adjustment of missionaries. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 9(2): 193–208.

Lin K-M, Tazuma L and Masuda M (1979) Adaptational problems of Vietnamese refugees: I. Health

and mental health status. Archives of General Psychiatry 36(9): 955–961.

Marginson S (2006) Dynamics of national and global competition in higher education. Higher

Education 52(1): 1–39.

Marginson S and Van Der Wende M (2007) Globalisation and higher education. OECD Education

Working Papers, No. 8. OECD Publishing (NJ1).

Mark E (2013) Student satisfaction and the customer focus in higher education. Journal of Higher

Education Policy and Management 35(1): 2–10.

Masgoret A (2006) Examining the role of language attitudes and motivation on the sociocultural

adjustment and the job performance of sojourners in Spain. International Journal of Intercultural

Relations 30(3): 311–331.

Masgoret A and Ward C (2006) Culture learning approach to acculturation. In: Sam DL and Berry

JW (eds) The Cambridge Handbook of Acculturation Psychology. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press, pp.58–77.

Mayo P (2009) Competitiveness, diversification and the international higher education cash flow: the

EU’s higher education discourse amidst the challenges of globalisation. International Studies in

Sociology of Education 19(2): 87–103.

Molinsky A (2007) Cross-cultural code-switching: The psychological challenges of adapting behavior

in foreign cultural interactions. Academy of Management Review 32(2): 622–640.

Neill J (2004) Kurt Lewin field theory. Available at http://wilderdom.com/theory/FieldTheory.html

(accessed 15 September 2013).

Phinney JS (1990) Ethnic identity in adolescents and adults: review of research. Psychological Bulletin

108(3): 499–514.

Qiang Z (2003) Internationalization of higher education: towards a conceptual framework. Policy

Futures in Education 1(2): 248–270.

Rust RT and Oliver RL (2000) Should we delight the customer? Journal of the Academy of Marketing

Science 28(1): 86–94.

Safdar S, Lay C and Struthers W (2003) The process of acculturation and basic goals: Testing a

multidimensional individual difference acculturation model with Iranian immigrants in Canada.

Applied Psychology 52(4): 555–579.

Schofield C, Cotton D, Gresty K, et al. (2013) Higher education provision in a crowded marketplace.

Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management 35(2): 193–205.

Schultz D and Schultz S (2004) A History of Modern Psychology. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Downloaded from pfe.sagepub.com by guest on April 28, 2016

Shafaei and Abd Razak 19

Schuster RM, Hammitt WE and Moore D (2003) A theoretical model to measure the appraisal and

coping response to hassles in outdoor recreation settings. Leisure Sciences 25(2-3): 277–299.

Searle W and Ward C (1990) The prediction of psychological and sociocultural adjustment during

cross-cultural transitions. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 14(4): 449–464.

Smith RA and Khawaja NG (2011) A review of the acculturation experiences of international students.

International Journal of Intercultural Relations 35(6): 699–713.

Sodowsky GR and Plake BS (1992) A Study of Acculturation Differences Among International People

and Suggestions for Sensitivity to Within-Group Differences. Journal of Counseling & Development

71(1): 53–59.

Sorrentino RM (2013) Looking for B ¼ f (P, E): The exception still forms the rule. Motivation and

Emotion 37(1): 4–13.

Stroebe W, Lenkert A and Jonas K (1988) Familiarity may breed contempt: The impact of student

exchange on national stereotypes and attitudes. In: Stroebe W, Bar-Tal D and Hewstone M (eds)

The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations. New York: Springer, pp.167–187.

Sumer S (2009) International students’ psychological and sociocultural adaptation in the United

States. Counseling and Psychological Services Dissertations. Paper 34.

Tajfel H (1981) Human Groups and Social Categories: Studies in Social Psychology. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Tajfel H and Turner J (1986) The social identity theory of intergroup behaviour. In: Austin W and

Worchel S (eds) The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Chicago: Nelson-Hall, pp.7–24.

Terry L (2011) International initiatives that facilitate global mobility in higher education. Michigan

State Law Review 2012(1): 305–356.

Thomaz JC (2010) Identification, reputation, and performance: Communication mediation. Latin

American Business Review 11(2): 171–197.

Wang Y and Sun S (2009) Examining Chinese students’ Internet use and cross-cultural adaptation:

Does loneliness speak much? Asian Journal of Communication 19(1): 80–96.

Ward C (1996) Acculturation. In: Landis D, Bennett J and Bennett M (eds) Handbook of Intercultural

Training, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, pp.124–147.

Ward C (1999) Models and measurements of acculturation. In: Lonner WI, Dinner DL, Forgays DK,

et al. (eds) Merging Past, Present and Future in Cross Cultural Psychology. Netherlands: Swets and

Zeitlinger, pp.221–230.

Ward C, Bochner S and Furnham A (2001) The Psychology of Culture Shock. Hove: Routledge,

Psychology Press.

Ward C and Kennedy A (1992) Locus of control, mood disturbance, and social difficulty during cross-

cultural transitions. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 16(2): 175–194.

Ward C and Kennedy A (1993a) Acculturation and cross-cultural adaptation of British residents in

Hong Kong. Journal of Social Psychology 133(3): 395–397.

Ward C and Kennedy A (1993b) Psychological and socio-cultural adjustment during cross-cultural

transitions: A comparison of secondary students overseas and at home. International Journal of

Psychology 28(2): 129–147.

Ward C and Kennedy A (1994) Acculturation strategies, psychological adjustment, and sociocultural

competence during cross-cultural transitions. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 18(3):

329–343.

Ward C, Okura Y, Kennedy A, et al. (1998) The U-curve on trial: A longitudinal study of

psychological and sociocultural adjustment during cross-cultural transition. International Journal

of Intercultural Relations 22(3): 277–291.

Ward C and Searle W (1991) The impact of value discrepancies and cultural identity on psychological

and sociocultural adjustment of sojourners. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 15(2):

209–224.

Wilkins S (2014) Internationalization of higher education in East Asia: trends of student mobility and

impact on education governance. Asia Pacific Journal of Education 34(3): 384–387.

Downloaded from pfe.sagepub.com by guest on April 28, 2016

20 Policy Futures in Education 0(0)

World Trade Organization (2010) Secretariat Report, supra note 3.

Yang B and Clum GA (1994) Life stress, social support, and problem-solving skills predictive of

depressive symptoms, hopelessness, and suicide ideation in an Asian student population: A test

of a model. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 24(2): 127–139.

Zeszotarski P (2001) ERIC review: Issues in global education initiatives in the community college.

Community College Review 29(1): 65–78.

Zhou Y, Jindal-Snape D, Topping K, et al. (2008) Theoretical models of culture shock and adaptation

in international students in higher education. Studies in Higher Education 33(1): 63–75.

Azadeh Shafaei is a PhD research fellow at School of Educational Studies, Universiti Sains

Malaysia (USM). She is a recipient of USM Global Fellowship. Her current research

interests include cross-cultural adaptation among international students, education

mobility, and education internationalisation.

Nordin Abd Razak is currently an Associate Professor at School of Educational Studies,

Universiti Sains Malaysia. He is a member of Malaysian Psychometric Association and a

member of Research Committee for TIMSS and PISA by the Curriculum Development

Division, Ministry of Education. His areas of interest are in measurement, scale

development and validation, multivariate and multilevel analysis, large-scale assessment

secondary data analysis (TIMSS and PISA), as well as investigating organisational

behaviour from the socio-psychological perspective.

Downloaded from pfe.sagepub.com by guest on April 28, 2016

You might also like

- The State of Mentoring - Change Agents ReportDocument31 pagesThe State of Mentoring - Change Agents ReportIsaac FullartonNo ratings yet

- SWOT Analysis On International Business and Economics Program University of Syiah KualaDocument8 pagesSWOT Analysis On International Business and Economics Program University of Syiah KualaCindy AngelaNo ratings yet

- Fostering A Culture of Quality Across Marinduque State College ProgramsDocument9 pagesFostering A Culture of Quality Across Marinduque State College ProgramsArmando ReyesNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Asian Social Science: Learning in Education, 2013Document16 pagesInternational Journal of Asian Social Science: Learning in Education, 2013Mohammed Mohammed Shoukry NaiemNo ratings yet

- The Role of Technology in The New Model of Literacy in TaiwanDocument5 pagesThe Role of Technology in The New Model of Literacy in TaiwanbarmarwanNo ratings yet

- Akareem, Hossain - 2016 - Open Review of Educational Research - Determinants of Education Quality What Makes Students' Perception DifferentDocument17 pagesAkareem, Hossain - 2016 - Open Review of Educational Research - Determinants of Education Quality What Makes Students' Perception DifferentPauloParenteNo ratings yet

- WTO/GATS and The Global Governance of Education: A Holistic Analysis of Its Impacts On Teachers' ProfessionalismDocument16 pagesWTO/GATS and The Global Governance of Education: A Holistic Analysis of Its Impacts On Teachers' ProfessionalismIreneNo ratings yet

- Ramaswamy, Et Al., 2021Document19 pagesRamaswamy, Et Al., 2021Anonymous 0aUZdm6kGGNo ratings yet

- SWOT Analysis On International Business and Economics Program University of Syiah KualaDocument7 pagesSWOT Analysis On International Business and Economics Program University of Syiah KualaCindy AngelaNo ratings yet

- Impacts of The Movement of Sps and Sls Facilities From GK To Bosso Campus On Student Well-BeingDocument34 pagesImpacts of The Movement of Sps and Sls Facilities From GK To Bosso Campus On Student Well-BeingMicheal kingNo ratings yet

- 8 PJES Internationalization Towards Fostering School Culture of Quality Practices and Perceived Impact 25072023Document25 pages8 PJES Internationalization Towards Fostering School Culture of Quality Practices and Perceived Impact 25072023Keith E. CunananNo ratings yet

- 2017 Oinam Student - Centered Approach To Teaching and Learning in Higher Education For Quality EnhancementDocument4 pages2017 Oinam Student - Centered Approach To Teaching and Learning in Higher Education For Quality Enhancementahbi mahdianing rumNo ratings yet

- Cynthia - Joseph - 2012 - Internationalizing The Curriculum-Pedagogy For Social JusticeDocument19 pagesCynthia - Joseph - 2012 - Internationalizing The Curriculum-Pedagogy For Social Justicemella kepriyantiNo ratings yet

- 15+article +sharipov+Document12 pages15+article +sharipov+José MelrinhoNo ratings yet

- Developing Inclusive Education Systems The Role of Organisational Cultures and LeadershipDocument17 pagesDeveloping Inclusive Education Systems The Role of Organisational Cultures and LeadershipHoracio Andrés Cornejo GarcésNo ratings yet

- Propasal Ed Full EditedDocument23 pagesPropasal Ed Full Editedidi kapatiNo ratings yet

- Difficultiesin Making Professional Science Teacherinthe 21 THDocument8 pagesDifficultiesin Making Professional Science Teacherinthe 21 THGulzhanNo ratings yet

- 2023 10 2 6 SudhanaDocument16 pages2023 10 2 6 SudhanaSome445GuyNo ratings yet

- School Leadership and Management Literature ReviewDocument5 pagesSchool Leadership and Management Literature ReviewafmzndvyddcoioNo ratings yet

- Adefila Et Al. - 2023 - Developing Transformative Pedagogies For TransdiscDocument25 pagesAdefila Et Al. - 2023 - Developing Transformative Pedagogies For TransdiscAraceli MartínezNo ratings yet

- 3developing Inclusive Education Systems The Role of Organisational Cultures and Leadership PDFDocument17 pages3developing Inclusive Education Systems The Role of Organisational Cultures and Leadership PDFVivi SalinasNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Educational Development: Serena Masino, Miguel Nin O-Zarazu ADocument13 pagesInternational Journal of Educational Development: Serena Masino, Miguel Nin O-Zarazu AJoy ValerieNo ratings yet

- 21st Century Skills ReportDocument20 pages21st Century Skills Reportapi-396616332No ratings yet

- Role of The Government in The Establishment of World-Class Universities in ChinaDocument15 pagesRole of The Government in The Establishment of World-Class Universities in ChinaDiệp TửNo ratings yet

- Global Citizenship Education and The Development of Globally Competent - Michael A Kopish - 2017Document40 pagesGlobal Citizenship Education and The Development of Globally Competent - Michael A Kopish - 2017Aprilasmaria SihotangNo ratings yet

- Online Enrollment System of Liceo de CagDocument19 pagesOnline Enrollment System of Liceo de CagSteven Vincent Flores PradoNo ratings yet

- 449-Article Text-1566-1-10-20200201Document11 pages449-Article Text-1566-1-10-20200201Pan PanNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document3 pagesChapter 2leniejuliNo ratings yet

- Katherine 1Document5 pagesKatherine 1Jeraldine RamisoNo ratings yet

- EJ1332422Document11 pagesEJ1332422Loulou MowsNo ratings yet

- Making A Road by talking-Wijeysingha&Emery-Final Draft-29Nov16Document17 pagesMaking A Road by talking-Wijeysingha&Emery-Final Draft-29Nov16VincentWijeysinghaNo ratings yet

- PDF Knight-2012-Student Mobility and Internationalization Trends PAPERDocument15 pagesPDF Knight-2012-Student Mobility and Internationalization Trends PAPERJuan Carlos Benavides BenavidesNo ratings yet

- Guest Editorial: Ijem 32,2Document4 pagesGuest Editorial: Ijem 32,2cansuNo ratings yet

- Era GlobalisasiDocument6 pagesEra Globalisasiwulianwawa84No ratings yet

- Is Teacher Education at Risk A Tale of Two Cities Hong Kong and MacauDocument17 pagesIs Teacher Education at Risk A Tale of Two Cities Hong Kong and Macauk_189114847No ratings yet

- What Are Inclusive Pedagogies in Higher Education A Systematic Scoping Review PDFDocument18 pagesWhat Are Inclusive Pedagogies in Higher Education A Systematic Scoping Review PDFsandra milena bernal rubioNo ratings yet

- New Phase of Internationalization of Higher Education and Institutional ChangeDocument20 pagesNew Phase of Internationalization of Higher Education and Institutional ChangevakifbankNo ratings yet

- Reflections On Educational Practice COVIDocument6 pagesReflections On Educational Practice COVILuis Eduardo MolinaNo ratings yet

- 浙江大学2022开卷考试(国际组织教育政策)Document6 pages浙江大学2022开卷考试(国际组织教育政策)LINNo ratings yet

- Asian International Students' College Experience: Relationship Between Quality of Personal Contact and Gains in LearningDocument26 pagesAsian International Students' College Experience: Relationship Between Quality of Personal Contact and Gains in LearningSTAR ScholarsNo ratings yet

- Reading Assignment 1Document16 pagesReading Assignment 1VanessaCastilloNo ratings yet

- Socio-Economic, Environmental and Personal Factors in The Choice of Country and Higher Education Institution For Studying Abroad Among International Students in MalaysiaDocument27 pagesSocio-Economic, Environmental and Personal Factors in The Choice of Country and Higher Education Institution For Studying Abroad Among International Students in Malaysiawangjieqing1228No ratings yet

- Is PISA Counter-Productive To Building Successful Educational SystemsDocument6 pagesIs PISA Counter-Productive To Building Successful Educational SystemsSandro DevidzeNo ratings yet

- Erika - Cakrawala - 39357 114353 4 PBDocument15 pagesErika - Cakrawala - 39357 114353 4 PBHerNo ratings yet

- Husain 2021 To What Extent Emotion Cognition and Behaviour Enhance A Student S Engagement A Case Study On The MajaDocument12 pagesHusain 2021 To What Extent Emotion Cognition and Behaviour Enhance A Student S Engagement A Case Study On The MajaalcadozovientomaderaNo ratings yet

- AbDocument2 pagesAblievNo ratings yet

- 89-Enhancing The Role of Alumni in The Growth of Higher Education Institutions-1636480355Document9 pages89-Enhancing The Role of Alumni in The Growth of Higher Education Institutions-1636480355K60 Phạm Khánh HuyềnNo ratings yet

- Academic PhrasebankDocument11 pagesAcademic PhrasebankAdnan AlfaridziNo ratings yet

- Jones 2020Document10 pagesJones 2020rarhamudiNo ratings yet

- Iranian Faculty Members' Metaphors of The Internationalization of Medical Sciences EducationDocument19 pagesIranian Faculty Members' Metaphors of The Internationalization of Medical Sciences Educationdigitalsystem23No ratings yet