Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Fragmented Frame: The Poetics of The Split-Screen: Draft

The Fragmented Frame: The Poetics of The Split-Screen: Draft

Uploaded by

brozacaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Fragmented Frame: The Poetics of The Split-Screen: Draft

The Fragmented Frame: The Poetics of The Split-Screen: Draft

Uploaded by

brozacaCopyright:

Available Formats

DRAFT

The Fragmented Frame:

The Poetics of the Split-Screen

Jim Bizzocchi

School of Interactive Arts and Technology

Simon Fraser University

<jimbiz@sfu.ca>

Abstract

The split-screen has a long, yet relatively under-theorized, place in the history of the

moving image. Salt finds examples as early as 1901 - including several instances of the

use of the split-screen to simultaneously represent two sides of a telephone call. Gance

used the split-screen spectacularly in the closing sequence to his masterpiece, Napoleon.

The use of this technique has never disappeared, but despite a brief flowering in the late

sixties and early seventies, it has generally remained a minor trope in the poetics of the

moving image. However, it is more in evidence in a range of contemporary films,

sometimes as a tour-de-force (Timecode, The Tracey Fragments), but more commonly

integrated and subordinated within the overall single-screen aesthetic.

This resurgence of the split-screen is supported by ongoing cultural changes in the

production, distribution and reception of the moving image. The computer desktop,

electronic games, television news, print comics and graphic novels have accustomed us to

reading the many-windowed visual screen. The video short forms (commercials, music

videos and series opening sequences) have acted as a testbed and incubator for the

development of more hyper-mediated visual grammars - including the split-screen.

Contemporary domestic media technologies privilege the pleasure of complex moving

image narratives and visual constructions. Larger high-definition video screens provide

the effective real estate for the display of multiple images, and ever-increasing home

playback options support the repeated viewing of more intricately faceted storylines and

imagery.

Some contemporary media theorists recognize the power and the potential of this form of

cinematic expression. Manovich argues that the twentieth century moving image

Jim Bizzocchi, 2009 P. 1

DRAFT

devalued what he calls “spatial montage” but that the digital imperative of this century -

both technical and cultural - are favorable to a more spatialized aesthetic that includes the

split-screen. Spielman maintains that the digital moving image uniquely privilege the

collaged and the spatial. Willis notes that contemporary filmmakers such as Greenaway

and Figgis use digital capabilities to break what Greenaway calls "the tyranny of the

frame" and make expressive use of a multi-windowed cinematic environment.

However, there is little theoretical work on the poetics or cinematic design of the split-

screen. This paper argues for a robust approach to the deconstruction and analysis of

split-screen sequences. This approach examines the phenomenon at three levels: the

narrative, the structural and the graphic. The narrative level considers the relationship of

the split-screen sequence to critical story parameters such as plot, character and

storyworld. The structural level investigates the formal relationships between the frames,

including the treatment of cinematic time and space, the identification of any overall

master-frame or figure-ground relationship, and the relationship of the split-images to the

sound track. The graphic level is a closer look at the design details, considering variables

such as frame shapes, number, layout, sequence initiation, and treatment of motion. This

three-level analysis is applied in a close-reading of Norman Jewison’s Thomas Crown

Affair (1968).

The Split-Screen: Critical Background

My research is concerned with the poetics - the design - of media works. In this regard,

the cinematic split-screen is an interesting - and somewhat puzzling phenonomenon.

Despite its long history, the cinematic split-screen has attracted relatively limited

attention in the literature of film history or film style. Much of film literature either

ignores the form, or relegate it to brief and passing mention. Those few texts that do

consider it, generally do not examine the poetics of the form as it has been used by film

artists.

Jim Bizzocchi, 2009 P. 2

DRAFT

Salt1 goes further than most in his overview of cinematic styles and technologies, where

he devotes two paragraphs in separate parts of the book, the first referring to two early

silent works, the second referring to three examples from the 60's. However, he has no

significant explication of the aesthetics in back of the stylistic choice.

Manovich2 has helped to trigger a more substantive examination of the expressive

possibilities of the form. He grounds his analysis in the tradition of Eisenstein's

"montage within the frame"3, and argues that the new digital technologies support a

"spatial montage", where multiple cinematic frames offer narrative paths where "montage

in time [editing] is no longer privileged over montage [in space]".4 This is a relatively

bold position for Manovich to take. The essence of the filmmaking art is the plasticity

and therefore the power inherent in cinema’s ability to present and juxtapose events – that

is to say, shots – in time. His claim for a co-equal cinematic “spatial montage” is a

significant departure, but is supported by Spielman, who argues that the digital moving

image privileges the spatial, the morph and the collage. 5

Willis6 agrees with Manovich’s formulation, noting that filmmakers such as Peter

Greenaway7 and Mike Figgis8 use digital capabilities to break what Greenaway calls "the

tyranny of the frame" and make expressive use of a multi-windowed cinematic

environment. Rhodes applies an ontological framework to the split-screen spatial

montage, arguing that the viewer of “multi-channel” films actively constructs meaning

out of the separate channels using a model related to metonymy.9 Friedberg situates the

split-screen in the history of screen practices, and constructs a taxonomy of

“multiplicity”: the use of a “frame within the frame” strategy in standard single-screen

1

Salt, Film Style and Technology: History and Analysis

2

Manovich, Language of New Media

3

Eisenstein, Film Form

4

Manovich, Language of New Media

5

Spielman, L., "Aesthetic Features in Digital Imaging: Collage and Morph", Wide Angle, Vol. 21, No. 1,

(1999)]

6

Willis, New Digital Cinema - Reinventing the Moving Image, pgs. 38 - 41

7

Greenaway, The Pillow Book, The Tulse Luper Suitcases, and others

8

Figgis, Timecode

9

Rhodes, G.A., Metonymy in the Moving Image, MFA Dissertation, State University of New York,

Buffalo, 2005. Available online at <http://www.garhodes.com/writing.html> - viewed March 15, 2009.

Jim Bizzocchi, 2009 P. 3

DRAFT

diegesis (“Rear Window”10), the self-conscious construction of separate split-screens as

sub-frames within a master frame, and the projection of films onto multiple screens

(Gance’s Napoleon, “expanded cinema” such as Vanderbeek’s videodrome, and the

tradition of World’s Fairs and international expositions).11

Unfortunately, these theorists offer little detail on the actual or the potential poetics of a

split-screen cinema. Sergei Eisenstein is more helpful in this regard, with his detailed list

of the visual “dynamics” – or to use his term: “conflicts” - that can be utilized for

building a montage within the frame. He lists the following (among others):

• Conflict of graphic directions

• Conflict of planes

• Conflict of volumes

• Conflict of scales and masses

• Close shots and long shots

• Conflict of depths

• Conflicts of light and darkness 12

These dynamics were intended for standard single-screen cinematic compositions, but as

general guidelines, they also apply to the world of the fragmented frame – the split-screen

History

Filmmakers have paid more attention to the possibilities of the split-screen than the

theorists. The split-screen device has never been wildly popular, but it has been around

for a long time, and despite periods of waxing and waning, has never gone away. The

most famous early example is Able Gance's triple-screen ending to Napoleon, which

switches between a stitched and unified Cinerama look and an alternative triptych

arrangement, with the two side screens providing commentary and amplification of the

10

Hitchcock, Rear Window

11

Friedberg, A., The Virtual Window: from Alberti to Microsoft, 2006, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

12

Eisenstein, op cit, pg. 38 - 39

Jim Bizzocchi, 2009 P. 4

DRAFT

images and themes of the dominant central screen. Barry Salt13 describes even earlier

films that used the split-screen to show both sides of a telephone conversation, a standard

convention which has survived through Pillow Talk down to the television series 24.

Hager argues that the depiction of the shared-but-separate telephonic space is one of three

major technological influences that have motivated the exploration of cinematic split-

screens.

The split-screen form had a renaissance in the late 60's and 70's, with such examples as

The Thomas Crown Affair, Woodstock, The Boston Strangler, The Longest Yard, More

American Graffiti, and Sisters and many others not shown such as Carrie, The Twilight's

Last Gleaming, and The Andromeda Strain - all of which can be characterized as having

an aggressive stance towards the use of split-screens as an integral part of the film's

dramatic and visual structure.

The experimentation with the device seemed to diminish significantly over the next two

decades, but its use is being actively revisited in many contemporary films dating from

the end of the 90's until today. Among many others, these more recent examples include

Timecode, Run Lola Run, Rules of Attraction, The Hulk, Requiem for a Dream, and

Phone Booth - plus others such as City of God, Snatch, The Pillow Book, Tulse Luper

Suitcase, Conversations with other Women, The Tracey Fragments, and the television

series 24, Trial and Retribution, and CSI-Miami.

Interestingly, the current rebirth differs from the 60's/70's renaissance in that the split-

screens today are used with comparatively more restraint. They tend to act as a

punctuation within a film's broader style, rather than as a defining visual motif as in the

earlier period. Notable exceptions to this trend are the television series examples, and the

films Timecode, Conversations with other Women, and in particular The Tracey

Fragments. These works foreground the commitment to the split-screen device as a

stylistic hallmark.

13

Salt, op cit

Jim Bizzocchi, 2009 P. 5

DRAFT

One might ask - why this checkered history? Part of the answer goes back to the defining

forces at the beginning of cinema. The early dominant form was not the cinema of

narrative to which we are now accustomed, but what Gunning calls “the Cinema of

Attractions”. Early commercial film exhibition consisted of a series of shorts, often

actuality films – primitive documentaries. These shorts initially featured relatively

mundane subjects, but were nonetheless “attractions” for viewers not used to cinema. A

series of “attractions” such as “Workers Leaving the Factory”, “Demolition of a Wall”, or

the famous “Arrival of a Train” were strung together to form the program. The power of

these attractions is reflected in the famous apocryphal story about the Train film.

Sophisticated turn-of-the-century Parisians were alleged to run out of the cinema in fear

of the oncoming train. The longevity of this patently absurd tale is an indication of the

power that early cinematic attractions did have over their audience. Other famous

attractions include the Edison films “The Kiss” and “Electrocution of an Elephant” –

even then sex and violence were compelling attractions for cinematic content. A film

program would consist of a heterogeneous series of these shorts – with no overarching

theme or story to join them. The draw was the “attraction” of both the content of the

films and the experience of the novel technology.

The cinema of attractions eventually lost out as the dominant cultural and economic form.

The cinema of attractions never disappeared, but became subordinated within a stronger

imperative towards a monolithic cinema of seamless narrative. Led by Hollywood, and

copied by other national cinemas globally, the narrative feature film became the

mainstream cinematic form. This form has traditionally relied on the erasure of visible

craft in order to privilege what Bolter and Grusin call the transparent and immediate

pleasure of story. The split-screen is some ways a throwback - a hypermediated

attraction that calls attention to itself, and therefore to the process of mediation. In doing

so, the split-screen breaks the suspension of disbelief and the commitment to

transparency and narrative.

If this is so, why the initial renaissance of the split-screen in the 60's and 70's? The

answer may lie in broader cultural and marketing realities. Hagener recognizes the late

Jim Bizzocchi, 2009 P. 6

DRAFT

60’s split-screen phenomenon, and argues that it was cinema’s response to the threat of

television.14 He sees the split-screen as the marker for cinema’s “otherness” vis-à-vis

television, which lacked the size and resolution needed to effectively display multiple

windows. I agree with this analysis of the importance and the expressive quality of the

split-screen in this era, but disagree with the conclusion about the economic motivation.

The threat from television was most directly felt in the fifties. The film industry’s

response from that era did include some split-screen works. However, this minor

direction (along with the other cinematic novelty - 3D films) was overshadowed by that

decade’s far more emphatic moves to color and to a variety of wide-screen processes. It

is interesting to note that all of these innovations are an appeal to the “cinema of

attractions” - displaying filmic visual attractions that the new competing medium of

television could not match.

In the late 60's on the other hand, the hegemony of cinema within popular culture was

threatened most acutely by a vibrant youth culture – one that was strongly oriented

towards music. The release of the next Beatles (or Dylan, Rolling Stones or Jimi

Hendrix) album was a more significant cultural event than the release of the next

Hollywood blockbuster movie - even if the star was the popular Steve McQueen.

However, in the context of the 60's and 70's, an aggressive commitment to the split-

screen was a cinematic attraction that was capable of "blowing the minds" and capturing

the attention of a youth culture comfortable with expanded consciousness and oriented

towards the visceral pleasures of the sensorium.

The rebirth of the cinematic split-screen today may be rooted in a similar dynamic.

Cinema's rivals for ascendancy within popular culture are more varied now than ever

before - video games, the internet, high-definition home theatre, a variety of mobile video

platforms - with more combinations appearing every year. As in earlier struggles for

cultural dominance, a general shift to a more hypermediated aesthetic is one tactic cinema

will employ.

14

Hagener, M., “The Aesthetics of Displays: How the Split Screen Remediates Other Media”, Refractory:

A Journal of Entertainment Media, <http://blogs.arts.unimelb.edu.au/refractory/2008/12/24/the-aesthetics-

of-displays-how-the-split-screen-remediates-other-media-–-malte-hagener/>, viewed March 12, 2009

Jim Bizzocchi, 2009 P. 7

DRAFT

There are also specific ongoing trends that have acclimated us to a multi-windowed

visual narrative environment. Most direct is perhaps the cumulative effect of 30 years of

the video short form. Commercials, rock-videos, and television series openers are

hypermediated forms that aggressively combine the cinema of visual attractions with the

cinema of narrative. They have developed the art of narrative compression and in the

process have taught us to see and follow faster and more visually complicated

presentations of story. In a slower paced, but just as hypermediated fashion, news and

sports programming has built up an acceptance of frames and windows as an integral part

of our televisual world. Finally, both Manovich15 and Bolter and Grusin16 point out that

the interactive screen has become a dominant cultural paradigm, and as such has the

power to reshape – in their terms “remediate” our expectations of other forms such as

cinema. An audience that is capable of switching among the multiple screens of the

computer desktop's standard Graphic User Interface, or the more rapid oscillation

between the control and display frames of a video game, is certainly on the way to

parsing a controlled and well-crafted multi-framed cinematic narrative.

All of this, of course is somewhat removed from the discourse of cinema. If film theory

hasn't addressed the split-screen options now readily available to filmmakers, what theory

will help? One place to look is in the histories of multi-screened film/video installations.

There is good writing on this domain, in a discursive arc that stretches from Gene

Youngblood's "Expanded Cinema"17 to Shaw's and Weibel's "Future Cinema"18.

However, there are few texts that include a detailed analysis of the expressive use of the

multiplied screen. They don’t reveal a concrete multi-screen poetics that could be tested

against the actual use of split-screens within a single-frame cinematic context.

15

Manovich, op. cit

16

Jay Bolter & Richard Grusin, Remediation

17

Youngblook, Expanded Cinema

18

Shaw and Weibel, Future Cinema

Jim Bizzocchi, 2009 P. 8

DRAFT

There may be more immediate help in the world of graphic media. Guides to visual arts

production and layout1920 stress stylistic concepts such as balance, unity, proportion, and

the dynamic between consistency & experimentation. These parameters should interest

filmmakers who wish to develop an effective layout of frames within a moving image.

Another rich source is the medium of comics. Both Greg Smith21 and Michael Cohen22

see the connection between the poetics of the film frame and those of comics, with Cohen

arguing that the use of split-screen in the cinematic Hulk is part of a conscious effort to

recreate the aesthetic of the comic inside the film. As it should be with cinema, the

relationship of comic book frames to the overall narrative is a crucial variable. The DC

Comics Guide to Pencilling Comics23 maintains that whether using a grid or a more free-

form panel layout, the comic book artist must avoid unclear flow, and take responsibility

for panels that are "arranged and designed in a comprehensible way [to pull] the eye of

the reader" through the story.

Practical guidelines on how a filmmaker can meet that objective in a moving medium

should be found in critical and practical texts on television – although again the literature

is surprisingly light. Herbert Zettl does address the design of split-screens within the

televisual world and gives some specifics to consider:

• the relationship between the primary and secondary frame

• the effect of directional vectors in the various frames

• the treatment of time and space across the frames.24

Thomas Crown Affair

We need to bridge from these general guidelines to a more robust understanding of the

expressive parameters of the multi-framed cinematic aesthetic. This paper relies on a

19

Parker, R., The Aldus Guide to Basic Design

20

White, Alex W., The Elements of Graphic Design

21

Greg M. Smith, Shaping Time: Expressivity and the Comics Frame, SCMS presentation, March 2006,

London

22

Michael Cohen, Panel Beating: Adapting Comics to Cinema Through 'Panelling', "Holy Men in Tights:

A Superheroes Conference", Melbourne, June 2005

23

Klaus Janson, The DC Comics Guide to Pencilling Comics

24

Herbert Zettl, Sight, Sound and Motion

Jim Bizzocchi, 2009 P. 9

DRAFT

close reading of an archetypal work of split-screen film to do so. Let’s consider the 1968

Thomas Crown Affair, directed by Norman Jewison, with Pablo Ferro as the split-screen

designer. A careful examination of the role of the split-screen within this work reveals

creative design decisions at three separate but complementary levels: the narrative level,

the structural level, and the graphic level.

On the narrative level, let's first examine the role that the split-screen sequences play in

the overall development of plot and story. There are four major split-screen segments

within the film, and each one serves a clear set of narrative functions.

The first split-screen segment is the title sequence. In addition to the production credits,

the split-screen images provide initial impressions of the two protagonists (Thomas

Crown and Vicky Anderson), hints at their ultimate romantic connection, and begin to

build the storyworld within which Crown lives - a world of money and privilege with a

dark side underneath.

The second split-screen segment of the film is concerned with the major caper of the film

- a daring business-district daylight robbery. The 6 separate split-screen sequences in this

segment are intercut with longer running full frame shots and sequences. The split-screen

sequences support both plot and character development. They show the preparations and

the aftermath of the robbery, and in the process they introduce the members of the gang.

At the same time the sequences make it clear that the gang members are mere agents of

Crown's will.

The third split-screen segment comes about half way through the film. This complicated

and highly hypermediated segment is also intercut with full frame shots and sequences,

but the split-screen portions dominate this segment. The 21 separate split-screen

sequences within this segment support the development of both plot and character. In

this scene, Vicky reveals herself to Thomas, and captures his initial attention. At the

same time the split-screen images reinforce the active and forceful nature of his character,

Jim Bizzocchi, 2009 P. 10

DRAFT

and the flirtatious and bold nature of hers. The complex play of the small inset screens

reinforce a growing sense of their mutual attraction.

The fourth and final split-screen segment comes near the end of the film. In this segment,

consisting of 8 short split-screen sequences intercut with full-frame shots, we see the

second robbery of the film. This segment is designed to directly service plot - we learn

nothing new about any of the characters, but we do see the final robbery.

It's clear from this high-level overview that split-screen segments can be used to support

broad narrative concerns: plot, character, and storyworld. However, a closer view will

help identify the detailed work of the split-screen at various levels:

• first, the narrative level,

• second - the structural level of formal relationships - such as the treatment of time

or space across the frames,

• and finally, the visual - or graphic - level.

Let's start with a sequence from early in the film. Scene one ends with a hidden Thomas

Crown interviewing one of his prospective minions who is blinded by an array of harsh

spotlights. This leads directly into scene two, which is dominated by a series of split-

screen sequences.

Fig. 1 - Thomas Crown Affair - sequence 2 - open

Jim Bizzocchi, 2009 P. 11

DRAFT

Let’s deconstruct this scene from our three perspectives: narrative, structural, and

graphic. This sequence serves several narrative functions. The first half of the scene

introduces the members of Crown's gang. (See Figure 1 above) It also advances the plot,

showing them in motion, presumably with a common goal. In the process, it reinforces

the sense of Crown's character - the controller of the subsidiary players. The second half

of the scene goes to storyworld - it reveals Crown's location, and the destination of the

gang members. (See Figure 2 below)

Fig. 2 - Thomas Crown Affair - sequence 2 - later

At a structural level, the formal relationships of the treatment of time and space in the

split-frames support the narrative goals. In the first part of the sequence, the split-frames

are introduced sequentially, but diegetically they share a common timeline, and imply a

convergent space. This reinforces the sense of shared purpose for these men. The central

landscape later in the sequence has the dominant position in the frame. This feature

further reinforces both their shared purpose and the location of their spatial convergence.

Jim Bizzocchi, 2009 P. 12

DRAFT

The graphic decisions in this sequence play their part as well. Despite their sequential

introduction, the first half of the sequence carefully builds a strong sense of informal

balance to the layout of the frames. (see Figure 3 below)

Fig. 3 - Thomas Crown Affair - sequence 2 - early

Note the informal balance

(Split-screen frame boundaries emphasized in Yellow by the author)

This informal balance is reinforced by the role played by the directional vectors - both

explicit motion vectors and implicit look vectors. (see Figure 4 below)

Jim Bizzocchi, 2009 P. 13

DRAFT

Fig. 4 - Thomas Crown Affair - sequence 2 - early

Note the motion vectors (Red) and the look vectors (Yellow)

In the second half of this segment, the balance is more formal. The combination of the

color values, the relative clarity of the frame lines, the position of the key frame at the

fulcrum of the balance, the zoom forward within that key frame - all combine to form a

figure-ground relationship which draws the eye in to the center and the Boston landscape

which forms the location of the next scene. (See figure 5 below)

Jim Bizzocchi, 2009 P. 14

DRAFT

Fig. 5 - Thomas Crown Affair - sequence 2 - later

Note the Combination of Formal Balance & Zoom Motion Vectors

This reading of one short sequence from the Thomas Crown demonstrates the detail and

care that can go into the design of a split-screen sequence. In order to fully analyze and

understand such a sequence, it is useful to review three inter-connected but still distinct

levels of cinematic decision-making:

First, consider the narrative level. What is the overall narrative arc of the film, and what

particular narrative aspects (plot, character, storyworld, emotion) does the split-screen

sequence support? At a finer level of granularity, what is the narrative flow within the

split-screen sequence itself?

Second, consider the structural level - the formal relationships between the frames.

How is time represented in the various frames? How is space represented? Do some

frames combine to form larger images? Are specific images repeated or duplicated? Is

Jim Bizzocchi, 2009 P. 15

DRAFT

there a dominant master frame? If so, what is the relationship between the master frame

and the subordinate frames? How do the split-screen visuals relate to the sound track?

Finally, consider the frames as graphic elements. How many frames are there? What

shape are the frames? What is the layout of the small frames within the full cinematic

frame? What are the individual and overall dynamics of the frames' directional vectors

such as look space or subject motion? Do the frames themselves move or change size or

shape? Are there other strong graphic variables (color, shape) within the frames? What

was the visual flow of the split sequence: how was it introduced, how did it evolve, how

was it phased out?

Broader Considerations

Finally, I want to complicate the common understanding of the experience the moving

image. We call this experience “linear”, in opposition to other experiences, which we

term “interactive”. However, the differences are more subtle than this dichotomy would

suggest, and my claim is that they are shrinking in the face of new technologies.

Watching a film has always been an interactive experience. The viewer actively

participates in the process. Besides a long tradition of reader-response media theorists

ranging from Bakhtin25 to Umberto Eco26, we can rely on one of the foremost authors in

the area of game design. Eric Zimmerman maintains there are four levels of interactivity:

cognitive or interpretive interactivity, functional or utilitarian interactivity, explicit

interactivity, and meta or cultural interactivity.27 28

Any film (or book/poem/painting/dance) operates at level one – but the level one

interactive demands of split-screen films are higher than most. The multi-framed film

offers a visualized version of increased narrative bandwidth. This style of presentation

25

Bakhtin, M.M. "Discourse in the Novel", The Dialogic Imagination, 1981, University of Texas Press,

Austin, TX

26

Eco, U. The Open Work, 1989, Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA

27

Zimmerman, E. “Against Hypertext”, <http://www.ericzimmerman.com/texts/Against_Hypertext.htm>

28

Zimmerman, E., “Narrative, Interactivity, Play, and Games: Four Naughty Concepts in Need of

Discipline”, in First Person, eds. Wardrip-Fruin and Harrigan, 2004, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

Jim Bizzocchi, 2009 P. 16

DRAFT

puts more pressure on the viewer to actively work in order to keep up with the story.

(Allegedly, this was part of Figgis’s motivation for filming TimeCode in a four-way split

- he wanted the viewer to have to pay close attention in order to follow all four visual

streams.)

However, let's look at Zimmerman's second level of interactivity: functional interactivity.

He defines functional interactivity as a combination of mental and physical acts we

perform when we are interacting with a text and its medium, be that text a film, painting,

or a book. With a book the supports for functional interactivity are the pages and the

binding (the "codex" that supplanted the papyrus roll), the numbers on each page, the

TOC, the index, the footnotes. Each of these affords certain types of user interaction.

This combination of artifact affordance and user interaction is what Zimmerman labels

functional interactivity. I argue that through this definition, we can see yet another

connection to the pleasure of split-screen cinema.

Consider the modes of functional interactivity that are available to film viewers today:

• the multiplex theatre - with multiple locations & viewing times

• standard television release, with multiple channels and broadcast time slots

• pay-per-view television

• DVD – both standard and Blu-Ray - with a full range of motion controls (forward,

reverse, fast, slow, freeze, plus chapter stops and a limited random access

capability

• legal (or quasi-legal) digital files on TiVo and other PVR devices

• rogue ripped versions on the internet – either excerpts or entire works

These devices afford possibilities for increasingly rich narrative constructions of the

moving image. These possibilities include:

• the split-screen examples that are the subject of this paper,

• the use of heavily layered digital constructions such as Pan’s Labyrinth or

MirrorMask,

Jim Bizzocchi, 2009 P. 17

DRAFT

• and the use of convoluted plot structures such as in Run Lola Run, or the films of

Quentin Tarentino and his many imitators.

The first two opportunities for complexity – split screens and rich CGI storyworlds – are

supported even further by the increasing adoption of larger and larger HD screens in the

home – the venue where intense viewer manipulation and control is possible. In any

case, the ability to easily control the playback and the frequency of moving image

presentation enables all of these more complex forms, and in the process turns the

experience into a more explicitly interactive process. Certainly, the full visual richness

of The Thomas Crown Affair can only fully be realized after repeated playback and

viewing. The Tracey Fragments is an example of an even more complex multi-

channeled visual construction, carrying with it a stronger imperative for playback review

in order to comprehend the filmic text.

This is not to say that the pleasures of traditional narrative and suspension of disbelief

will go away. These traditional cinematic pleasures are far too satisfying for that to

happen. However that experience will increasingly be supplemented with the more

hypermediated pleasure of unriddling the complex visual and narrative constructions that

filmmakers can now build into their cinematic works.i

Jim Bizzocchi, 2009 P. 18

You might also like

- The Architecture of the Screen: Essays in Cinematographic SpaceFrom EverandThe Architecture of the Screen: Essays in Cinematographic SpaceRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Krauss 2 Moments From The Post-Medium ConditionDocument8 pagesKrauss 2 Moments From The Post-Medium ConditionThomas GolsenneNo ratings yet

- Ansi Bhma A156.40 2015 PDFDocument34 pagesAnsi Bhma A156.40 2015 PDFShawn DeolNo ratings yet

- Build Your Own Recumbent TrikeDocument242 pagesBuild Your Own Recumbent TrikeArte Colombiano100% (4)

- Film in LiteratureDocument10 pagesFilm in LiteratureChikiarifuka OzaleaNo ratings yet

- Animated Documentary - Technological Change and Experimentation - India Mara MartinsDocument3 pagesAnimated Documentary - Technological Change and Experimentation - India Mara MartinsMatt GouldNo ratings yet

- EenbergDocument9 pagesEenbergSylwia KaliszNo ratings yet

- Rick Warner - "Go-For-Broke Games of History Chris Marker Between 'Old' and 'New' Media'"Document13 pagesRick Warner - "Go-For-Broke Games of History Chris Marker Between 'Old' and 'New' Media'"xuaoqunNo ratings yet

- Expanding The Space, Breaking The Time: A Research of The Audio-Visual Language of Multi-Screen Video InstallationDocument13 pagesExpanding The Space, Breaking The Time: A Research of The Audio-Visual Language of Multi-Screen Video InstallationAyoub MHNo ratings yet

- Brian Jacobson, "Constructions of Cinematic Space: Spatial Practice at The Intersection of Film and Theory"Document146 pagesBrian Jacobson, "Constructions of Cinematic Space: Spatial Practice at The Intersection of Film and Theory"MIT Comparative Media Studies/WritingNo ratings yet

- Beyond Interactive Cinema - InteractDocument8 pagesBeyond Interactive Cinema - InteractCristina BirladeanuNo ratings yet

- Rediscovering Iconographic StorytellingDocument11 pagesRediscovering Iconographic Storytellingjuan acuñaNo ratings yet

- Match Frame and Jump CutDocument11 pagesMatch Frame and Jump Cuttoth.gergelyNo ratings yet

- History of FilmDocument15 pagesHistory of FilmJauhari Alfan100% (1)

- Anthony Vidler - The Explosion of Space PDFDocument17 pagesAnthony Vidler - The Explosion of Space PDFRomulloBarattoFontenelleNo ratings yet

- The Hollywood War Film: Critical Observations from World War I to IraqFrom EverandThe Hollywood War Film: Critical Observations from World War I to IraqRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Modernity Thesis CinemaDocument7 pagesModernity Thesis Cinemasallysteeleeverett100% (1)

- Vertov Architecture Vidler 1 PDFDocument17 pagesVertov Architecture Vidler 1 PDFtang_bozenNo ratings yet

- Film Studies (General)Document17 pagesFilm Studies (General)nutbihariNo ratings yet

- The Veiled Genealogies of Animation and Cinema: Donald CraftonDocument18 pagesThe Veiled Genealogies of Animation and Cinema: Donald CraftonLayke ZhangNo ratings yet

- Auto Motivations Digital Cinema and KiarDocument11 pagesAuto Motivations Digital Cinema and KiarDebanjan BandyopadhyayNo ratings yet

- Dynamic Drawings and Dilated Time Framing in Comics and FilmDocument22 pagesDynamic Drawings and Dilated Time Framing in Comics and FilmIvette NophalNo ratings yet

- 10/40/70: Constraint as Liberation in the Era of Digital Film TheoryFrom Everand10/40/70: Constraint as Liberation in the Era of Digital Film TheoryRating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (1)

- From Dimensional Effects'Document8 pagesFrom Dimensional Effects'Layke ZhangNo ratings yet

- Montage - The Hidden Language of FilmDocument4 pagesMontage - The Hidden Language of FilmAyoub MHNo ratings yet

- University of California Press Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Film QuarterlyDocument3 pagesUniversity of California Press Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Film QuarterlytaninaarucaNo ratings yet

- Film MakingDocument36 pagesFilm Makingআলটাফ হুছেইনNo ratings yet

- A. Kaes - Silent CinemaDocument12 pagesA. Kaes - Silent CinemaMasha KolgaNo ratings yet

- Two Moments From The Post-MediumDocument9 pagesTwo Moments From The Post-MediumpipordnungNo ratings yet

- Good by Dragon inDocument11 pagesGood by Dragon inSebastian Morales100% (1)

- Cinema Against SpectacleDocument348 pagesCinema Against SpectacleValida Baba100% (3)

- A Cinema in The Gallery, A Cinema in Ruins: ErikabalsomDocument17 pagesA Cinema in The Gallery, A Cinema in Ruins: ErikabalsomD. E.No ratings yet

- Edgar Neville - La Vida en UnhiloDocument11 pagesEdgar Neville - La Vida en UnhiloPablo Rubio GijonNo ratings yet

- Cowan, Michael - Cutting Through The ArchiveDocument40 pagesCowan, Michael - Cutting Through The Archiveescurridizox20No ratings yet

- Tony Conrad Bowed Film 1974Document15 pagesTony Conrad Bowed Film 1974Renan CamiloNo ratings yet

- Three Phantasies of Cinema-Reproduction, Mimesis, AnnihilationDocument16 pagesThree Phantasies of Cinema-Reproduction, Mimesis, AnnihilationhandeNo ratings yet

- Johann N. Schmidt - Narration in FilmDocument13 pagesJohann N. Schmidt - Narration in FilmMacedonianoNo ratings yet

- Principles of Visual AnthroDocument59 pagesPrinciples of Visual Anthrogetachew.tilahun123No ratings yet

- Jonathan Walley - The Material of Film and The Idea of Cinema. Contrasting Practices in Sixties and SeventiesDocument17 pagesJonathan Walley - The Material of Film and The Idea of Cinema. Contrasting Practices in Sixties and Seventiesdr_benway100% (1)

- Cinema As Dispositif - Between Cinema and Contemporary Art - André Parente & Victa de CarvalhoDocument19 pagesCinema As Dispositif - Between Cinema and Contemporary Art - André Parente & Victa de CarvalhoFet BacNo ratings yet

- Death of CinemaDocument39 pagesDeath of Cinemapratik_bose100% (1)

- A Cinema in The Gallery A Cinema in RuinsDocument17 pagesA Cinema in The Gallery A Cinema in RuinsjosepalaciosdelNo ratings yet

- How Does The Film Metropolis Visually Handle Dystopian Themes and What Are Its Main InfluencesDocument7 pagesHow Does The Film Metropolis Visually Handle Dystopian Themes and What Are Its Main InfluencesCiaranJCaulNo ratings yet

- Cannes Dispatch, Pt. 1 - Notes - E-FluxDocument3 pagesCannes Dispatch, Pt. 1 - Notes - E-FluxPaolo TizonNo ratings yet

- Birgit Hein Structural FilmDocument13 pagesBirgit Hein Structural FilmJihoon Kim100% (1)

- Decker, Christof - Interrogations of Cinematic NormsDocument23 pagesDecker, Christof - Interrogations of Cinematic Normsescurridizox20No ratings yet

- Concrete AnimationDocument16 pagesConcrete AnimationNexuslord1kNo ratings yet

- 16 02 2017 - Foreshadow PDFDocument11 pages16 02 2017 - Foreshadow PDFJessica GonçalvesNo ratings yet

- Dynamic Drawings and Dilated Time Framing in Comics and FilmDocument22 pagesDynamic Drawings and Dilated Time Framing in Comics and FilmcmalavogliaNo ratings yet

- Denny, Deconstructing DepthDocument21 pagesDenny, Deconstructing DepthMark TrentonNo ratings yet

- Between Stillness and Motion - Film, Photography, AlgorithmsDocument245 pagesBetween Stillness and Motion - Film, Photography, AlgorithmsMittsou100% (2)

- 1.2 Literature and Motion PicturesDocument31 pages1.2 Literature and Motion PicturesBogles Paul FernandoNo ratings yet

- ch20Document20 pagesch20Hương NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Towards A Poetics of The Cinematographic Frame PDFDocument14 pagesTowards A Poetics of The Cinematographic Frame PDFBAGAS REYHANU ADAM ADAMNo ratings yet

- Film Language by Christian Metz 1Document6 pagesFilm Language by Christian Metz 1Mihaela SanduloiuNo ratings yet

- James Leo Cahill - AnacinemaDocument12 pagesJames Leo Cahill - AnacinemaFrederico M. NetoNo ratings yet

- Kohut MRZDocument25 pagesKohut MRZbrozacaNo ratings yet

- Orientalism, Star Power and Cinethetic Racism in Seventies Italian Exploitation CinemaDocument15 pagesOrientalism, Star Power and Cinethetic Racism in Seventies Italian Exploitation CinemabrozacaNo ratings yet

- Aldrich 1977Document8 pagesAldrich 1977brozacaNo ratings yet

- Greimas 1977Document19 pagesGreimas 1977brozacaNo ratings yet

- Weird Movie List 01Document30 pagesWeird Movie List 01brozacaNo ratings yet

- 10 22492 Ijcs 4 2 05Document23 pages10 22492 Ijcs 4 2 05brozacaNo ratings yet

- Panel 11Document69 pagesPanel 11brozacaNo ratings yet

- Metaphor and The Psychoanalytic Situation (The Psychoanalytic Quarterly, Vol. 48, Issue 3) (1979)Document24 pagesMetaphor and The Psychoanalytic Situation (The Psychoanalytic Quarterly, Vol. 48, Issue 3) (1979)brozacaNo ratings yet

- Metropolitan Museum of Art Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To The Metropolitan Museum of Art BulletinDocument7 pagesMetropolitan Museum of Art Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To The Metropolitan Museum of Art BulletinbrozacaNo ratings yet

- The Hellenization of Ishtar: Nudity, Fetishism, and The Production of Cultural Differentiation in Ancient ArtDocument14 pagesThe Hellenization of Ishtar: Nudity, Fetishism, and The Production of Cultural Differentiation in Ancient ArtbrozacaNo ratings yet

- University of Illinois PressDocument18 pagesUniversity of Illinois PressbrozacaNo ratings yet

- South Atlantic Modern Language AssociationDocument11 pagesSouth Atlantic Modern Language AssociationbrozacaNo ratings yet

- International Forum of PsychoanalysisDocument5 pagesInternational Forum of PsychoanalysisbrozacaNo ratings yet

- Smut Peddler ZineDocument36 pagesSmut Peddler Zinebrozaca100% (1)

- Theology and Sexuality: Jouissance, Generation and The Coming of GodDocument29 pagesTheology and Sexuality: Jouissance, Generation and The Coming of GodbrozacaNo ratings yet

- Sites: The Journal of Twentieth-Century/ Contemporary French Studies Revue D'études FrançaisDocument6 pagesSites: The Journal of Twentieth-Century/ Contemporary French Studies Revue D'études FrançaisbrozacaNo ratings yet

- Board of Regents of The University of OklahomaDocument2 pagesBoard of Regents of The University of OklahomabrozacaNo ratings yet

- Falling: Jouissance or Madness: Studies in Gender and SexualityDocument5 pagesFalling: Jouissance or Madness: Studies in Gender and SexualitybrozacaNo ratings yet

- Ekstasis As (Beyond?) Jouissance: Sex, Queerness, and Apophaticism in The Eastern Orthodox TraditionDocument20 pagesEkstasis As (Beyond?) Jouissance: Sex, Queerness, and Apophaticism in The Eastern Orthodox TraditionbrozacaNo ratings yet

- Modern Language Association Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To PMLADocument5 pagesModern Language Association Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To PMLAbrozacaNo ratings yet

- Third Text: To Cite This Article: Derek Conrad Murray (2007) Obscene Jouissance, Third Text, 21:1, 31-39, DOIDocument10 pagesThird Text: To Cite This Article: Derek Conrad Murray (2007) Obscene Jouissance, Third Text, 21:1, 31-39, DOIbrozacaNo ratings yet

- Studies in Gender and SexualityDocument13 pagesStudies in Gender and SexualitybrozacaNo ratings yet

- Journal of Sex ResearchDocument15 pagesJournal of Sex ResearchbrozacaNo ratings yet

- University of California Press Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To RepresentationsDocument7 pagesUniversity of California Press Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To RepresentationsbrozacaNo ratings yet

- Scale Structure, Coercion, and The Interpretation of Measure Phrases in JapaneseDocument39 pagesScale Structure, Coercion, and The Interpretation of Measure Phrases in JapanesebrozacaNo ratings yet

- Sho Ogawa's Thesis On Pinku Eiga FilmsDocument88 pagesSho Ogawa's Thesis On Pinku Eiga FilmsbrozacaNo ratings yet

- Textual Practice: To Cite This Article: Karma Lochrie (1999) Presumptive Sodomy and Its ExclusionsDocument18 pagesTextual Practice: To Cite This Article: Karma Lochrie (1999) Presumptive Sodomy and Its ExclusionsbrozacaNo ratings yet

- Studies in Gender and Sexuality: To Cite This Article: Jeffrey R. Guss M.D. (2010) The Danger of Desire: Anal Sex andDocument18 pagesStudies in Gender and Sexuality: To Cite This Article: Jeffrey R. Guss M.D. (2010) The Danger of Desire: Anal Sex andbrozacaNo ratings yet

- Journal of HomosexualityDocument12 pagesJournal of HomosexualitybrozacaNo ratings yet

- The Semantics of Even and Negative Polarity Items in JapaneseDocument10 pagesThe Semantics of Even and Negative Polarity Items in JapanesebrozacaNo ratings yet

- ComboFix Quarantined FilesDocument1 pageComboFix Quarantined FilesJoseph FoxNo ratings yet

- The Problem of Increasing Human Energy - Nikola Tesla PDFDocument27 pagesThe Problem of Increasing Human Energy - Nikola Tesla PDFKarhys100% (2)

- BU ProspectusDocument40 pagesBU ProspectusVikram YadavNo ratings yet

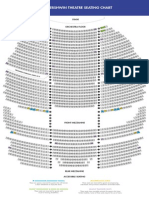

- The Gershwin Theatre Seating Chart: StageDocument1 pageThe Gershwin Theatre Seating Chart: StageCharles DavidsonNo ratings yet

- Chart Patterns: Symmetrical Triangles The Ascending TriangleDocument8 pagesChart Patterns: Symmetrical Triangles The Ascending TriangleGene Stanley100% (1)

- 16 Karlekar Purva DTSP Assi 3Document14 pages16 Karlekar Purva DTSP Assi 3Purva100% (1)

- Activation PDFDocument270 pagesActivation PDFPedro Ruiz MedianeroNo ratings yet

- SPM (SEN 410) Lecturer HandoutsDocument51 pagesSPM (SEN 410) Lecturer HandoutsinzovarNo ratings yet

- Admission CriteriaDocument2 pagesAdmission CriteriaDr Vikas GuptaNo ratings yet

- Don Quijote Unit Summative AssessmentDocument1 pageDon Quijote Unit Summative AssessmentMaria MontoyaNo ratings yet

- Efhkessa PDF 1698096163Document16 pagesEfhkessa PDF 1698096163Antoni GarciaNo ratings yet

- WWI 1st Infantry DivisionDocument62 pagesWWI 1st Infantry DivisionCAP History Library100% (1)

- Active and Passive VoiceDocument3 pagesActive and Passive VoiceCray CrayNo ratings yet

- TIFDDocument1 pageTIFDAtulNo ratings yet

- Kubernetes CKA 0100 Core Concepts PDFDocument77 pagesKubernetes CKA 0100 Core Concepts PDFShobhit SrivastavaNo ratings yet

- Homestay Application FormDocument4 pagesHomestay Application FormlazikotoshpulatovaNo ratings yet

- Teens ProblemDocument56 pagesTeens ProblemLazzie LPNo ratings yet

- Configuring Resilient Ethernet Protocol: Information About Configuring REPDocument12 pagesConfiguring Resilient Ethernet Protocol: Information About Configuring REPGabi Si Florin JalencuNo ratings yet

- Longitudinal Vibration of Marine Propeller-Shafting SystemDocument15 pagesLongitudinal Vibration of Marine Propeller-Shafting SystemAli Osman BayirNo ratings yet

- PDBA Operations Course OutlineDocument12 pagesPDBA Operations Course OutlineQasim AbrahamsNo ratings yet

- Varsity KA Class & Exam Routine (Part-01)Document2 pagesVarsity KA Class & Exam Routine (Part-01)Yousuf JamilNo ratings yet

- Corporatedatabase 44Document74 pagesCorporatedatabase 44Dhirendra PatilNo ratings yet

- English Holiday HomeworkDocument18 pagesEnglish Holiday Homeworkzainab.syed017No ratings yet

- SGL 3 (Haematinics)Document32 pagesSGL 3 (Haematinics)raman mahmudNo ratings yet

- Aircraft Material & Production - MANUALDocument45 pagesAircraft Material & Production - MANUALKV Yashwanth100% (1)

- Final Report: Asteroid Deflection: Page 1 of 42Document42 pagesFinal Report: Asteroid Deflection: Page 1 of 42Shajed AhmedNo ratings yet

- Job Stress QuestionnaireDocument5 pagesJob Stress QuestionnaireRehman KhanNo ratings yet

- Analytical Programming Project 2Document11 pagesAnalytical Programming Project 2Kyrsti DeaneNo ratings yet