Professional Documents

Culture Documents

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

13 viewsBuilding and Maintaining Relationships

Building and Maintaining Relationships

Uploaded by

AAAThe document discusses building and maintaining relationships. It covers the value of social capital derived from relationships, theories for why we form relationships including social exchange theory and needs theory. It also discusses characteristics related to needs for inclusion, control, and affection. Additionally, it outlines stages relationships go through in coming together (initiating, experimenting, intensifying, integrating, bonding) and coming apart (differentiating, circumscribing, stagnating, avoiding, terminating). Factors that predict relationship failure include criticism, contempt, defensiveness, and stonewalling. The document also discusses self-disclosure and intimacy in relationships.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You might also like

- Marriages and Families Diversity and Change 8th Edition Schwartz Solutions Manual 1Document11 pagesMarriages and Families Diversity and Change 8th Edition Schwartz Solutions Manual 1tracey100% (48)

- Adler - Interplay Chapter 09 - PPTDocument34 pagesAdler - Interplay Chapter 09 - PPTCassandra100% (1)

- MODULE 9 Personal RelationshipsDocument59 pagesMODULE 9 Personal RelationshipsThomas Maverick85% (26)

- Communication In Relationships: How To Build And Maintain Bonds With People In Life, Love, And The WorkplaceFrom EverandCommunication In Relationships: How To Build And Maintain Bonds With People In Life, Love, And The WorkplaceNo ratings yet

- Goal-Attainment Theory by Imogene KingDocument55 pagesGoal-Attainment Theory by Imogene KingGrace Lyn Borres Impas100% (2)

- Signed Off - Introduction To Philosophy12 - q2 - m6 - Intersubjectivity - v3 PDFDocument34 pagesSigned Off - Introduction To Philosophy12 - q2 - m6 - Intersubjectivity - v3 PDFRaniel John Avila Sampiano73% (15)

- 2nd LessonDocument21 pages2nd LessonArjay Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Social Penetration TheoryDocument5 pagesSocial Penetration TheoryKayla Mae AbutayNo ratings yet

- Adler - Interplay Chapter 09 - PPTDocument34 pagesAdler - Interplay Chapter 09 - PPTGrant DeanNo ratings yet

- The Stages of Interpersonal RelationshipDocument5 pagesThe Stages of Interpersonal RelationshipItaLim50% (2)

- Development: Prepared By: Galuh Kusuma Hapsari, M.Ikom Dosen Prodi Ilkom Universitas Multimedia NusantaraDocument36 pagesDevelopment: Prepared By: Galuh Kusuma Hapsari, M.Ikom Dosen Prodi Ilkom Universitas Multimedia Nusantaralisa riatiNo ratings yet

- Module 9: Personal RelationshipDocument8 pagesModule 9: Personal RelationshipKristel Anne GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Interpersonal RelationsDocument8 pagesInterpersonal RelationsajayrajvyasNo ratings yet

- Interpersonal Attraction & Close RelationshipsDocument7 pagesInterpersonal Attraction & Close RelationshipsOliviaDroverNo ratings yet

- Skills On Interpersonal RelationshipsDocument19 pagesSkills On Interpersonal Relationshipsjideofo100% (1)

- Chapter 4: Social Relationships and Interaction: Learning ModuleDocument24 pagesChapter 4: Social Relationships and Interaction: Learning Modulemchenlie asherNo ratings yet

- E RelationshipDocument24 pagesE RelationshipRameshNo ratings yet

- InterDocument8 pagesInterShraddha RaiNo ratings yet

- Social PenetrationDocument3 pagesSocial PenetrationIgnes DeaNo ratings yet

- Saint James High SchoolDocument4 pagesSaint James High SchoolrebodemcrisNo ratings yet

- 3.4 Love, Relationship, Live in and Break Ups Psychology General AssignmentDocument11 pages3.4 Love, Relationship, Live in and Break Ups Psychology General AssignmentAman DanielNo ratings yet

- Personal Relationship Hand OutDocument5 pagesPersonal Relationship Hand OutZaza May VelascoSbNo ratings yet

- Interpersonal Relationship SkillsDocument4 pagesInterpersonal Relationship Skillssharan786100% (1)

- Personal Development ReviewerDocument10 pagesPersonal Development Reviewerjanicesebio61No ratings yet

- PerDev ReviewerDocument3 pagesPerDev ReviewerMariette ChuaNo ratings yet

- Personal Relationship - 10Document17 pagesPersonal Relationship - 10Mandy Xi100% (2)

- Personal Relationship Attraction Love andDocument25 pagesPersonal Relationship Attraction Love andHelios FzhNo ratings yet

- Describe How The Four Affect The Way You Feel, and Hence Your Communication in An Important SituationDocument9 pagesDescribe How The Four Affect The Way You Feel, and Hence Your Communication in An Important SituationglNo ratings yet

- pERSONAL RELATIONSHIPSDocument20 pagespERSONAL RELATIONSHIPSGHIEKITANENo ratings yet

- Interpersonal - Notetinterpersonal Skillextlec VeitDocument5 pagesInterpersonal - Notetinterpersonal Skillextlec VeitFadriansyah FarisNo ratings yet

- Psychology NotesDocument7 pagesPsychology NotesAshiNo ratings yet

- PerDev Lesson 1Document86 pagesPerDev Lesson 1Mitchelle RaborNo ratings yet

- Final Exam QuestionsDocument8 pagesFinal Exam Questionsapi-408647155No ratings yet

- Personal Relationship: Attraction, Love, and CommitmentDocument43 pagesPersonal Relationship: Attraction, Love, and CommitmentApollo Freno0% (1)

- Learning Activity Sheets Personal Development Q1Document5 pagesLearning Activity Sheets Personal Development Q1Frich Dela PazNo ratings yet

- Conflict Resolution - Fet YmoosaDocument21 pagesConflict Resolution - Fet YmoosaYasaar MoosaNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2Document76 pagesLesson 2Jeddah Lynn AbellonNo ratings yet

- PerDev - Q2 - Module 7 - Personal-Relationship - Ver2Document9 pagesPerDev - Q2 - Module 7 - Personal-Relationship - Ver2ROSE YEENo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Live in RelationshipDocument5 pagesResearch Paper On Live in Relationshipxhzscbbkf100% (1)

- PRE-2 Quarter Exam Guide Scosci 61 (Personality Development) Building and Maintaining RelationshipsDocument2 pagesPRE-2 Quarter Exam Guide Scosci 61 (Personality Development) Building and Maintaining RelationshipsLyca Venancio BermeoNo ratings yet

- Final Review - Quality and Intimate RelationshipsDocument16 pagesFinal Review - Quality and Intimate Relationshipssaruji_sanNo ratings yet

- Personal RelationshipDocument119 pagesPersonal RelationshipCarl Anthony Lague PahuyoNo ratings yet

- Personal RelationshipDocument10 pagesPersonal RelationshipDeign Rochelle CastilloNo ratings yet

- M18 M19 Quarter 2 PERDEVDocument30 pagesM18 M19 Quarter 2 PERDEVPatrick De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Interpersonal RelationsajscbaksDocument8 pagesInterpersonal RelationsajscbaksThomas RajanNo ratings yet

- Lesson 18Document18 pagesLesson 18LANIE JANE BRUCALNo ratings yet

- 1 Personal RelationhipsDocument32 pages1 Personal Relationhipsjzwf8m82gjNo ratings yet

- Understanding The 4 Communication Styles - What's YoursDocument12 pagesUnderstanding The 4 Communication Styles - What's YoursJAYPEE LAPIRA100% (2)

- Perdev-L8 3Document39 pagesPerdev-L8 3sembranjohnmike77No ratings yet

- ZZZZZZZZZZZDocument13 pagesZZZZZZZZZZZJoseph besanaNo ratings yet

- PerDev 2nd P. PART 2Document7 pagesPerDev 2nd P. PART 2Ronie Mark F. BatoonNo ratings yet

- Gender & Society Midterm LessonsDocument21 pagesGender & Society Midterm LessonsMary Joy AliviadoNo ratings yet

- NotessDocument5 pagesNotessalonsabenadiNo ratings yet

- 1Document6 pages1Michael MimsNo ratings yet

- Perdev1 2Document12 pagesPerdev1 2Candy PadizNo ratings yet

- Nurture Your RelationshipDocument2 pagesNurture Your RelationshipMary Biscocho100% (1)

- Advance Social Psychology A Report By: Miss Crisavil C. CatubayDocument45 pagesAdvance Social Psychology A Report By: Miss Crisavil C. CatubaypaolosleightofhandNo ratings yet

- Establishing Positive Relationships: Christine Foster, MA, LLPC, NCCDocument18 pagesEstablishing Positive Relationships: Christine Foster, MA, LLPC, NCCGr3y D3ngu3100% (1)

- Interpersonal RelationshipsDocument51 pagesInterpersonal RelationshipsNeeraj Bhardwaj86% (14)

- Final Rev PerdevDocument16 pagesFinal Rev PerdevCleo GrayNo ratings yet

- Relationships - Mark MansonDocument25 pagesRelationships - Mark MansonMervin Wong75% (4)

- Attraction and IntimacyDocument3 pagesAttraction and Intimacysigfridmonte100% (1)

- Chapter TwoDocument18 pagesChapter Twotokumaunity2No ratings yet

- Critical Thinking Review 1-5Document8 pagesCritical Thinking Review 1-5AAANo ratings yet

- Group Decision-Making: Leadership and ProcessDocument5 pagesGroup Decision-Making: Leadership and ProcessAAANo ratings yet

- CMN1148 Chapter6Document5 pagesCMN1148 Chapter6AAANo ratings yet

- Managing Conflict and Practicing CivilityDocument9 pagesManaging Conflict and Practicing CivilityAAANo ratings yet

- CMN1148 Chapter3Document4 pagesCMN1148 Chapter3AAANo ratings yet

- Communicating Nonverbally: (Examples Textbooks)Document4 pagesCommunicating Nonverbally: (Examples Textbooks)AAANo ratings yet

- ADM1300 Chapter13Document14 pagesADM1300 Chapter13AAANo ratings yet

- CMN1148 Chapter5Document3 pagesCMN1148 Chapter5AAANo ratings yet

- Self-Image-How We See OurselvesDocument4 pagesSelf-Image-How We See OurselvesAAANo ratings yet

- Understanding, Navigating, and Managing Our IdentitiesDocument5 pagesUnderstanding, Navigating, and Managing Our IdentitiesAAANo ratings yet

- Managers and CommunicationDocument10 pagesManagers and CommunicationAAANo ratings yet

- ADM 1300 Chapter1 NotesDocument4 pagesADM 1300 Chapter1 NotesAAANo ratings yet

- ADM 1300 Chapter9Document4 pagesADM 1300 Chapter9AAANo ratings yet

- Chapter 4: Global Perspective: Home HostDocument5 pagesChapter 4: Global Perspective: Home HostAAANo ratings yet

- ADM 1300 Chapter10Document12 pagesADM 1300 Chapter10AAANo ratings yet

- Designing Organizational StructureDocument10 pagesDesigning Organizational StructureAAANo ratings yet

- ADM 1300 Management HistoryDocument4 pagesADM 1300 Management HistoryAAANo ratings yet

- Siegel Interpersonal NeurobiologyDocument28 pagesSiegel Interpersonal NeurobiologyMaria Kompoti100% (3)

- Social StyleDocument20 pagesSocial Styleshenmugapriyalakshmanan5353No ratings yet

- Alden, Taylor - 2004 - Interpersonal Processes in Social Phobia PDFDocument26 pagesAlden, Taylor - 2004 - Interpersonal Processes in Social Phobia PDFJulian LloydNo ratings yet

- 116 Hum Rel Syl SPR 10Document9 pages116 Hum Rel Syl SPR 10akindrickNo ratings yet

- First Semester English NoteDocument30 pagesFirst Semester English Noterohan joshiNo ratings yet

- Arundale R.face As Relational & Interactional (2006)Document26 pagesArundale R.face As Relational & Interactional (2006)Виктор_Леонтьев100% (3)

- Measuring Social Intelligence-The MESI MethodologyDocument9 pagesMeasuring Social Intelligence-The MESI MethodologyLuiza Naca0% (1)

- The Johari Window A ReconceptualizationDocument4 pagesThe Johari Window A ReconceptualizationAdeliaNo ratings yet

- The Advantages and Disadvantages of Preventing Students in Engaging Relationship at SFESDocument45 pagesThe Advantages and Disadvantages of Preventing Students in Engaging Relationship at SFESKnth Arhnfold Ugalde BonggoNo ratings yet

- Document Code Revision / Version ID Rev. 00 Date Created / Updated May. 2019Document4 pagesDocument Code Revision / Version ID Rev. 00 Date Created / Updated May. 2019fordmayNo ratings yet

- The Role of Nonverbal Communication in Service EncountersDocument18 pagesThe Role of Nonverbal Communication in Service EncountersIrina CosteaNo ratings yet

- OD Unit 4Document20 pagesOD Unit 4dhivyaNo ratings yet

- Basic Concepts of SelfDocument31 pagesBasic Concepts of SelfJeanzy Anne GupitNo ratings yet

- How To Prevent Juvenile DelinquencyDocument21 pagesHow To Prevent Juvenile DelinquencyEdward Pagar AlamNo ratings yet

- Life Stress and BurnoutDocument14 pagesLife Stress and BurnoutCammille AlampayNo ratings yet

- Teori ChickeringDocument15 pagesTeori ChickeringMohamad Iskandar100% (1)

- LMR 1Document11 pagesLMR 1Jecel EranNo ratings yet

- THERACOM!Document4 pagesTHERACOM!CHi NAiNo ratings yet

- Model of Pedagogical Political ProjectDocument4 pagesModel of Pedagogical Political Project4gen_1No ratings yet

- SW 3402 Course BookDocument379 pagesSW 3402 Course BookNurjehan A. DimacangunNo ratings yet

- Factors Strengthening Marriage A Review On What Binds Couples Together-2019-01!09!10-12Document10 pagesFactors Strengthening Marriage A Review On What Binds Couples Together-2019-01!09!10-12Impact JournalsNo ratings yet

- Abstract Sull'Assertivita'Document45 pagesAbstract Sull'Assertivita'Gabriella Mae Magpayo ValentinNo ratings yet

- Health and Family Life Education Curriculum Guides (2009)Document77 pagesHealth and Family Life Education Curriculum Guides (2009)Brent GlasgowNo ratings yet

- Organisational BehaviourDocument41 pagesOrganisational BehaviourDr-Isaac JNo ratings yet

- Team Building ModuleDocument3 pagesTeam Building ModuleLuis Jun NaguioNo ratings yet

- The Role of Brand Love in Consumer Brand RelationshipsDocument9 pagesThe Role of Brand Love in Consumer Brand RelationshipsIrfan QadirNo ratings yet

- Enide ManuscriptDocument34 pagesEnide ManuscriptDon James VillaroNo ratings yet

Building and Maintaining Relationships

Building and Maintaining Relationships

Uploaded by

AAA0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

13 views5 pagesThe document discusses building and maintaining relationships. It covers the value of social capital derived from relationships, theories for why we form relationships including social exchange theory and needs theory. It also discusses characteristics related to needs for inclusion, control, and affection. Additionally, it outlines stages relationships go through in coming together (initiating, experimenting, intensifying, integrating, bonding) and coming apart (differentiating, circumscribing, stagnating, avoiding, terminating). Factors that predict relationship failure include criticism, contempt, defensiveness, and stonewalling. The document also discusses self-disclosure and intimacy in relationships.

Original Description:

Original Title

CMN1148 Chapter8

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThe document discusses building and maintaining relationships. It covers the value of social capital derived from relationships, theories for why we form relationships including social exchange theory and needs theory. It also discusses characteristics related to needs for inclusion, control, and affection. Additionally, it outlines stages relationships go through in coming together (initiating, experimenting, intensifying, integrating, bonding) and coming apart (differentiating, circumscribing, stagnating, avoiding, terminating). Factors that predict relationship failure include criticism, contempt, defensiveness, and stonewalling. The document also discusses self-disclosure and intimacy in relationships.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

13 views5 pagesBuilding and Maintaining Relationships

Building and Maintaining Relationships

Uploaded by

AAAThe document discusses building and maintaining relationships. It covers the value of social capital derived from relationships, theories for why we form relationships including social exchange theory and needs theory. It also discusses characteristics related to needs for inclusion, control, and affection. Additionally, it outlines stages relationships go through in coming together (initiating, experimenting, intensifying, integrating, bonding) and coming apart (differentiating, circumscribing, stagnating, avoiding, terminating). Factors that predict relationship failure include criticism, contempt, defensiveness, and stonewalling. The document also discusses self-disclosure and intimacy in relationships.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

You are on page 1of 5

Building and maintaining relationships

The value of relationships

Social capital: A resources based on interpersonal connections that can be converted into

economic and other benefits

Bonding social capital: benefits that result from close relationships with parents,

children, and other family members

Bridging social capital: benefits that result from connections with friends and close

associates

Linking social capital: benefits that result from relationships with in positions of power

who are outside of other usual network

Reasons for forming relationships

Social exchange theory

Use an economic model to weigh the perceived costs and benefits associated with a

relationship

Predicts that we will leave a relationship in which the costs outweigh the benefits

Needs theory (FIRO: Fundamental interpersonal relations orientation)

Need for inclusions

Need to be connected to other people

Need for control

Need to influence our relationships, decisions, and activities and to let others

influence us

Need for affection

Need to feel liked by others, which will lead to greater level of openness in

interactions

Need for inclusion

Ideal personal characteristics

Individual who has the ability to enjoy being with others or being along

Over social characteristics

Individual who has tendency to work extra hard to seek attention and interactions with

others

Under social characteristics

Individual who has a tendency to avoid interaction with others

Need for control

Ideal personal characteristics

Individual alternates between exercising control and allowing others to exercise control

Individual feels comfortable leading at times and following at other times

An healthy aspect of control is setting of relationships boundaries—physical, emotional,

or other

Need for affection

Ideal personal type

Individual who wants to be liked but feels comfortable in situations that may result in dislike

Under personal type

Individual who feels undervalued and seeks to avoid close relationships

Over personal type

Individual who seeks to establish close relationships with everyone, regardless of whether

others show interest

Origins of relationships

Relationship of circumstance

Relationships that develop because of situations or circumstances in which we find ourselves

Relationship of choice

Relationships we actively seek out and choose to develop

Relationship contexts

Family

Development of internal working models

Friends

Childhood, adolescence, early adulthood, middle adulthood

Work colleagues

Relationship of circumstance, relationship of choice, working and social friendships,

romantic relationships

Romantic partners

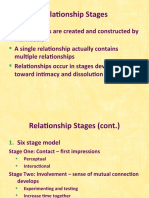

Stages of romantic relationship

Knapp identified ten stages through which relationship move: five ‘coming together’ stages

and five ‘coming apart’ stages

Beebe, Beebe and Redmond compared the stages of relationships to an elevator ride, where

we may

Get off each floor, look around, and maybe stay for a short or long time

Skip floors and take a fast ride upward to intimacy

Fail to find what we have been looking for, turn around, and go down again

The relational elevator: going up or down?

Coming together

Initiating

Experimenting

Intensifying

Integrating

Bonding

Coming apart

Differentiating

Circumscribing

Stagnating

Avoiding

Terminating

Coming together: initiating

You notice the other and form a first impression based on verbal and nonverbal elements

E.g., appearance and dress, body language, and speech

You talk about superficial topics such as current events and the weather

you try to gather information about the other person, which will enable you to decide if you

want to move forward with the relationship

if you decide to pursue the relationship, you move to the next level

Coming together: experimenting

You look for common ground by sharing information on school, hobbies, work, etc.

In the effort to find common ground, you ask and respond to a lot of routine questions such

‘Where are you from?’ ‘What do you do for a living?’ ‘What do you like to do in your free

time?’

To move to the next level of the relationship, both of you must show an interest in moving

forward

Coming together: intensifying

You spend more time together in shared activities

Your increase physical contact—e.g., more shows of affection in public—and look for signs of

commitment

You take bigger risks by disclosing more personal or intimate information such as ‘I am

worried about failing that course and getting kicked out of school’ or ‘I am afraid I might lose

my job.’

You are in a position to move to the next stage if the other person responds well to your self-

disclosures and self-discloses in response

Coming together: integrating

You become a social unit in the eyes of others, sharing activities, interests, and holidays

You receive invitations and attend events as a couple

You develop restricted language codes (‘insider language’) and share daily rituals

You may adopt a similar dress code or even dress like the other person

You think in terms of shared property—ours, not yours or mine

Coming together: bonding

You communicate the statues of your relationship in a more formal and public way

You move in together or get engaged or married

Your trust that the other will accept your ‘real self’

You talk about your commitment to be present for the other person through difficult times

Coming apart: differentiating

You may experience a decrease in physical contact and interaction at the differentiating

stage

You may start to use words such as I, me, and mine instead of we, us , and ours

You experience a shift toward individual instead of shared identities

The move toward individual identities can sometimes add a spark to the relationship as you

share new interests and adventures; but if you start to prefer time away from the other, you

may be taking the elevator to a lower floor

Coming apart: circumscribing

You communicate less often with the other person

Your talk revolves around safe and impersonal topics

Your share fewer of your problems with the other person

You commitment to the relationship declines, but others do not see the decline

Coming apart: stagnating

Your relationship has become shallow and predictable: same friends, same routines, same

conversations

You spend less time with the other person

You go through the motions, but you no longer care

Your lack of interest becomes more obvious—to the person and to outsiders

You can still recover the relationship, but it will take a lot of work and serious mutual

commitment

Coming apart: avoiding

You ignore or avoid the person altogether

You may leave the room or just tune out

You may be superficially polite or openly hostile

You no longer depend on the other for confirmation of self-value

Coming apart: terminating

You or your partner decides to end the relationship

Your notice of intention may take the form of a letter, phone call, text message, tweet, social

media posting, legal document, or even a note left on the bathroom mirror

Subsequent conversations revolve around practical matters such as division of property

Endings can be positive or negative

Predicting relationship failure by analyzing communication patterns

Experiments with ‘love lab’ involved 3000 participants engaged in a simulated dispute

The researchers observed and analyzed physiological and verbal patterns that characterized

the disputant behaviors

The researchers developed the ability to predict separation or divorce in 94 percent of the

cases, based on how disputants engaged in arguments

They concluded that constructive arguments, focused on the problem and not the people,

are healthy and normal responses to conflict they do not predict separation or divorce

What predicts relationship failure?

What does predict relationship failure?

Criticism—attack upon personality or character of the other

Contempt—insults and other signs of disrespect

Defensiveness—reaction based on perception that you are a victim

Stonewalling—withdrawing and disengaging from the conflict instead of addressing the

problem

Social penetration theory

Social penetration theory says that closeness in relationship comes from sharing information

about ourselves

As we share increasingly personal info, we build intimacy

Breadth—the number of conversational topics that allow you to reveal aspects of yourself

(e.g., hobbies, career, ambitions, health, sports played, and other interests)

Depth—the amount of information available on any topic (e.g., superficial info about a

hobby or more intimate info about a fear of losing your scholarship)

The internal drive to self-disclose

Reward centers in the brain light up more when we talk about ourselves than when we talk

about others

Volunteers in experiments accept less money in exchange for the chance to talk about

themselves

Writing about traumatic, stressful , or emotional events boosts our emotional and physical

health

People enjoy sharing secrets, as witnessed by the PostSecret.com website

PostSecret.com: a way to self-disclose?

Begun by Frank Warren in 2004

Working on national suicide line

Learned of people’s deep need to share

Handed out 3000 postcards to strangers in D.C. & asked them to return cards with secrets

never before shared

Received more than a million cards since that time

The dangers of self-disclosure

Voyeurism—spying into the private lives of others, especially prevalent in age of social

media

Physical safety concerns—e.g., stalking

Financial concerns—e.g., stolen financial records and identities

Psychological and emotional concerns—e.g., stresses associated with cyber bullying

Tips for building and maintaining relationships

Show interest in others, ask questions, and avoid talking too much about yourself

Be realistic about the people who populate your home, social, and work life

Instead of dwelling on the irritating habits of a co-worker, roommate, or family member,

note the good qualities of that person

Work at seeing the other person’s perspective rather than explaining others’ behavior from

your own point of view

Recognize that you and others will have differences of opinion, but you do not need to

address all of these differences

Use your words and nonverbal communication to make what John Gottman calls ‘repair

attempts’ when you see a conflict developing

Self-disclose to build intimacy

Set boundaries

Don’t let electronic devices replace or interfere with face-to-face interaction

You might also like

- Marriages and Families Diversity and Change 8th Edition Schwartz Solutions Manual 1Document11 pagesMarriages and Families Diversity and Change 8th Edition Schwartz Solutions Manual 1tracey100% (48)

- Adler - Interplay Chapter 09 - PPTDocument34 pagesAdler - Interplay Chapter 09 - PPTCassandra100% (1)

- MODULE 9 Personal RelationshipsDocument59 pagesMODULE 9 Personal RelationshipsThomas Maverick85% (26)

- Communication In Relationships: How To Build And Maintain Bonds With People In Life, Love, And The WorkplaceFrom EverandCommunication In Relationships: How To Build And Maintain Bonds With People In Life, Love, And The WorkplaceNo ratings yet

- Goal-Attainment Theory by Imogene KingDocument55 pagesGoal-Attainment Theory by Imogene KingGrace Lyn Borres Impas100% (2)

- Signed Off - Introduction To Philosophy12 - q2 - m6 - Intersubjectivity - v3 PDFDocument34 pagesSigned Off - Introduction To Philosophy12 - q2 - m6 - Intersubjectivity - v3 PDFRaniel John Avila Sampiano73% (15)

- 2nd LessonDocument21 pages2nd LessonArjay Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Social Penetration TheoryDocument5 pagesSocial Penetration TheoryKayla Mae AbutayNo ratings yet

- Adler - Interplay Chapter 09 - PPTDocument34 pagesAdler - Interplay Chapter 09 - PPTGrant DeanNo ratings yet

- The Stages of Interpersonal RelationshipDocument5 pagesThe Stages of Interpersonal RelationshipItaLim50% (2)

- Development: Prepared By: Galuh Kusuma Hapsari, M.Ikom Dosen Prodi Ilkom Universitas Multimedia NusantaraDocument36 pagesDevelopment: Prepared By: Galuh Kusuma Hapsari, M.Ikom Dosen Prodi Ilkom Universitas Multimedia Nusantaralisa riatiNo ratings yet

- Module 9: Personal RelationshipDocument8 pagesModule 9: Personal RelationshipKristel Anne GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Interpersonal RelationsDocument8 pagesInterpersonal RelationsajayrajvyasNo ratings yet

- Interpersonal Attraction & Close RelationshipsDocument7 pagesInterpersonal Attraction & Close RelationshipsOliviaDroverNo ratings yet

- Skills On Interpersonal RelationshipsDocument19 pagesSkills On Interpersonal Relationshipsjideofo100% (1)

- Chapter 4: Social Relationships and Interaction: Learning ModuleDocument24 pagesChapter 4: Social Relationships and Interaction: Learning Modulemchenlie asherNo ratings yet

- E RelationshipDocument24 pagesE RelationshipRameshNo ratings yet

- InterDocument8 pagesInterShraddha RaiNo ratings yet

- Social PenetrationDocument3 pagesSocial PenetrationIgnes DeaNo ratings yet

- Saint James High SchoolDocument4 pagesSaint James High SchoolrebodemcrisNo ratings yet

- 3.4 Love, Relationship, Live in and Break Ups Psychology General AssignmentDocument11 pages3.4 Love, Relationship, Live in and Break Ups Psychology General AssignmentAman DanielNo ratings yet

- Personal Relationship Hand OutDocument5 pagesPersonal Relationship Hand OutZaza May VelascoSbNo ratings yet

- Interpersonal Relationship SkillsDocument4 pagesInterpersonal Relationship Skillssharan786100% (1)

- Personal Development ReviewerDocument10 pagesPersonal Development Reviewerjanicesebio61No ratings yet

- PerDev ReviewerDocument3 pagesPerDev ReviewerMariette ChuaNo ratings yet

- Personal Relationship - 10Document17 pagesPersonal Relationship - 10Mandy Xi100% (2)

- Personal Relationship Attraction Love andDocument25 pagesPersonal Relationship Attraction Love andHelios FzhNo ratings yet

- Describe How The Four Affect The Way You Feel, and Hence Your Communication in An Important SituationDocument9 pagesDescribe How The Four Affect The Way You Feel, and Hence Your Communication in An Important SituationglNo ratings yet

- pERSONAL RELATIONSHIPSDocument20 pagespERSONAL RELATIONSHIPSGHIEKITANENo ratings yet

- Interpersonal - Notetinterpersonal Skillextlec VeitDocument5 pagesInterpersonal - Notetinterpersonal Skillextlec VeitFadriansyah FarisNo ratings yet

- Psychology NotesDocument7 pagesPsychology NotesAshiNo ratings yet

- PerDev Lesson 1Document86 pagesPerDev Lesson 1Mitchelle RaborNo ratings yet

- Final Exam QuestionsDocument8 pagesFinal Exam Questionsapi-408647155No ratings yet

- Personal Relationship: Attraction, Love, and CommitmentDocument43 pagesPersonal Relationship: Attraction, Love, and CommitmentApollo Freno0% (1)

- Learning Activity Sheets Personal Development Q1Document5 pagesLearning Activity Sheets Personal Development Q1Frich Dela PazNo ratings yet

- Conflict Resolution - Fet YmoosaDocument21 pagesConflict Resolution - Fet YmoosaYasaar MoosaNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2Document76 pagesLesson 2Jeddah Lynn AbellonNo ratings yet

- PerDev - Q2 - Module 7 - Personal-Relationship - Ver2Document9 pagesPerDev - Q2 - Module 7 - Personal-Relationship - Ver2ROSE YEENo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Live in RelationshipDocument5 pagesResearch Paper On Live in Relationshipxhzscbbkf100% (1)

- PRE-2 Quarter Exam Guide Scosci 61 (Personality Development) Building and Maintaining RelationshipsDocument2 pagesPRE-2 Quarter Exam Guide Scosci 61 (Personality Development) Building and Maintaining RelationshipsLyca Venancio BermeoNo ratings yet

- Final Review - Quality and Intimate RelationshipsDocument16 pagesFinal Review - Quality and Intimate Relationshipssaruji_sanNo ratings yet

- Personal RelationshipDocument119 pagesPersonal RelationshipCarl Anthony Lague PahuyoNo ratings yet

- Personal RelationshipDocument10 pagesPersonal RelationshipDeign Rochelle CastilloNo ratings yet

- M18 M19 Quarter 2 PERDEVDocument30 pagesM18 M19 Quarter 2 PERDEVPatrick De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Interpersonal RelationsajscbaksDocument8 pagesInterpersonal RelationsajscbaksThomas RajanNo ratings yet

- Lesson 18Document18 pagesLesson 18LANIE JANE BRUCALNo ratings yet

- 1 Personal RelationhipsDocument32 pages1 Personal Relationhipsjzwf8m82gjNo ratings yet

- Understanding The 4 Communication Styles - What's YoursDocument12 pagesUnderstanding The 4 Communication Styles - What's YoursJAYPEE LAPIRA100% (2)

- Perdev-L8 3Document39 pagesPerdev-L8 3sembranjohnmike77No ratings yet

- ZZZZZZZZZZZDocument13 pagesZZZZZZZZZZZJoseph besanaNo ratings yet

- PerDev 2nd P. PART 2Document7 pagesPerDev 2nd P. PART 2Ronie Mark F. BatoonNo ratings yet

- Gender & Society Midterm LessonsDocument21 pagesGender & Society Midterm LessonsMary Joy AliviadoNo ratings yet

- NotessDocument5 pagesNotessalonsabenadiNo ratings yet

- 1Document6 pages1Michael MimsNo ratings yet

- Perdev1 2Document12 pagesPerdev1 2Candy PadizNo ratings yet

- Nurture Your RelationshipDocument2 pagesNurture Your RelationshipMary Biscocho100% (1)

- Advance Social Psychology A Report By: Miss Crisavil C. CatubayDocument45 pagesAdvance Social Psychology A Report By: Miss Crisavil C. CatubaypaolosleightofhandNo ratings yet

- Establishing Positive Relationships: Christine Foster, MA, LLPC, NCCDocument18 pagesEstablishing Positive Relationships: Christine Foster, MA, LLPC, NCCGr3y D3ngu3100% (1)

- Interpersonal RelationshipsDocument51 pagesInterpersonal RelationshipsNeeraj Bhardwaj86% (14)

- Final Rev PerdevDocument16 pagesFinal Rev PerdevCleo GrayNo ratings yet

- Relationships - Mark MansonDocument25 pagesRelationships - Mark MansonMervin Wong75% (4)

- Attraction and IntimacyDocument3 pagesAttraction and Intimacysigfridmonte100% (1)

- Chapter TwoDocument18 pagesChapter Twotokumaunity2No ratings yet

- Critical Thinking Review 1-5Document8 pagesCritical Thinking Review 1-5AAANo ratings yet

- Group Decision-Making: Leadership and ProcessDocument5 pagesGroup Decision-Making: Leadership and ProcessAAANo ratings yet

- CMN1148 Chapter6Document5 pagesCMN1148 Chapter6AAANo ratings yet

- Managing Conflict and Practicing CivilityDocument9 pagesManaging Conflict and Practicing CivilityAAANo ratings yet

- CMN1148 Chapter3Document4 pagesCMN1148 Chapter3AAANo ratings yet

- Communicating Nonverbally: (Examples Textbooks)Document4 pagesCommunicating Nonverbally: (Examples Textbooks)AAANo ratings yet

- ADM1300 Chapter13Document14 pagesADM1300 Chapter13AAANo ratings yet

- CMN1148 Chapter5Document3 pagesCMN1148 Chapter5AAANo ratings yet

- Self-Image-How We See OurselvesDocument4 pagesSelf-Image-How We See OurselvesAAANo ratings yet

- Understanding, Navigating, and Managing Our IdentitiesDocument5 pagesUnderstanding, Navigating, and Managing Our IdentitiesAAANo ratings yet

- Managers and CommunicationDocument10 pagesManagers and CommunicationAAANo ratings yet

- ADM 1300 Chapter1 NotesDocument4 pagesADM 1300 Chapter1 NotesAAANo ratings yet

- ADM 1300 Chapter9Document4 pagesADM 1300 Chapter9AAANo ratings yet

- Chapter 4: Global Perspective: Home HostDocument5 pagesChapter 4: Global Perspective: Home HostAAANo ratings yet

- ADM 1300 Chapter10Document12 pagesADM 1300 Chapter10AAANo ratings yet

- Designing Organizational StructureDocument10 pagesDesigning Organizational StructureAAANo ratings yet

- ADM 1300 Management HistoryDocument4 pagesADM 1300 Management HistoryAAANo ratings yet

- Siegel Interpersonal NeurobiologyDocument28 pagesSiegel Interpersonal NeurobiologyMaria Kompoti100% (3)

- Social StyleDocument20 pagesSocial Styleshenmugapriyalakshmanan5353No ratings yet

- Alden, Taylor - 2004 - Interpersonal Processes in Social Phobia PDFDocument26 pagesAlden, Taylor - 2004 - Interpersonal Processes in Social Phobia PDFJulian LloydNo ratings yet

- 116 Hum Rel Syl SPR 10Document9 pages116 Hum Rel Syl SPR 10akindrickNo ratings yet

- First Semester English NoteDocument30 pagesFirst Semester English Noterohan joshiNo ratings yet

- Arundale R.face As Relational & Interactional (2006)Document26 pagesArundale R.face As Relational & Interactional (2006)Виктор_Леонтьев100% (3)

- Measuring Social Intelligence-The MESI MethodologyDocument9 pagesMeasuring Social Intelligence-The MESI MethodologyLuiza Naca0% (1)

- The Johari Window A ReconceptualizationDocument4 pagesThe Johari Window A ReconceptualizationAdeliaNo ratings yet

- The Advantages and Disadvantages of Preventing Students in Engaging Relationship at SFESDocument45 pagesThe Advantages and Disadvantages of Preventing Students in Engaging Relationship at SFESKnth Arhnfold Ugalde BonggoNo ratings yet

- Document Code Revision / Version ID Rev. 00 Date Created / Updated May. 2019Document4 pagesDocument Code Revision / Version ID Rev. 00 Date Created / Updated May. 2019fordmayNo ratings yet

- The Role of Nonverbal Communication in Service EncountersDocument18 pagesThe Role of Nonverbal Communication in Service EncountersIrina CosteaNo ratings yet

- OD Unit 4Document20 pagesOD Unit 4dhivyaNo ratings yet

- Basic Concepts of SelfDocument31 pagesBasic Concepts of SelfJeanzy Anne GupitNo ratings yet

- How To Prevent Juvenile DelinquencyDocument21 pagesHow To Prevent Juvenile DelinquencyEdward Pagar AlamNo ratings yet

- Life Stress and BurnoutDocument14 pagesLife Stress and BurnoutCammille AlampayNo ratings yet

- Teori ChickeringDocument15 pagesTeori ChickeringMohamad Iskandar100% (1)

- LMR 1Document11 pagesLMR 1Jecel EranNo ratings yet

- THERACOM!Document4 pagesTHERACOM!CHi NAiNo ratings yet

- Model of Pedagogical Political ProjectDocument4 pagesModel of Pedagogical Political Project4gen_1No ratings yet

- SW 3402 Course BookDocument379 pagesSW 3402 Course BookNurjehan A. DimacangunNo ratings yet

- Factors Strengthening Marriage A Review On What Binds Couples Together-2019-01!09!10-12Document10 pagesFactors Strengthening Marriage A Review On What Binds Couples Together-2019-01!09!10-12Impact JournalsNo ratings yet

- Abstract Sull'Assertivita'Document45 pagesAbstract Sull'Assertivita'Gabriella Mae Magpayo ValentinNo ratings yet

- Health and Family Life Education Curriculum Guides (2009)Document77 pagesHealth and Family Life Education Curriculum Guides (2009)Brent GlasgowNo ratings yet

- Organisational BehaviourDocument41 pagesOrganisational BehaviourDr-Isaac JNo ratings yet

- Team Building ModuleDocument3 pagesTeam Building ModuleLuis Jun NaguioNo ratings yet

- The Role of Brand Love in Consumer Brand RelationshipsDocument9 pagesThe Role of Brand Love in Consumer Brand RelationshipsIrfan QadirNo ratings yet

- Enide ManuscriptDocument34 pagesEnide ManuscriptDon James VillaroNo ratings yet