Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Temple2018 - Mediterranean Diet

Temple2018 - Mediterranean Diet

Uploaded by

Andreea MihalacheCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Solution Manual of Modern Semiconductor Devices For Integrated Circuits (Chenming Calvin Hu)Document122 pagesSolution Manual of Modern Semiconductor Devices For Integrated Circuits (Chenming Calvin Hu)hu leo86% (7)

- CH 10Document30 pagesCH 10Narendran KumaravelNo ratings yet

- Credit Policy Sample: Accounts Receivable AnalysisDocument3 pagesCredit Policy Sample: Accounts Receivable AnalysisAlinaNo ratings yet

- Giraffe Blood CirculationDocument9 pagesGiraffe Blood Circulationthalita asriandinaNo ratings yet

- 4 Roadtec 600 Cummins QSXDocument24 pages4 Roadtec 600 Cummins QSXdavidNo ratings yet

- Article: Effects of A Mediterranean-Style Diet On Cardiovascular Risk FactorsDocument15 pagesArticle: Effects of A Mediterranean-Style Diet On Cardiovascular Risk FactorsBunga dewanggi NugrohoNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0002916522012357 MainDocument9 pages1 s2.0 S0002916522012357 MainSalvia Elvaretta HarefaNo ratings yet

- Risk Factors Associated With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and The Frequency of Nafld Affected PatientsDocument5 pagesRisk Factors Associated With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and The Frequency of Nafld Affected PatientsIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Anti Inflammatory Effects of The Mediterranean Diet The Experience of The Predimed StudyDocument8 pagesAnti Inflammatory Effects of The Mediterranean Diet The Experience of The Predimed StudyAprilia MutiaraNo ratings yet

- The Role of Diet Therapy and ECG Monitoring in Preventing Cardiovascular Diseases in Diabetes Mellitus: A ReviewDocument4 pagesThe Role of Diet Therapy and ECG Monitoring in Preventing Cardiovascular Diseases in Diabetes Mellitus: A ReviewIJRDPM JOURNALNo ratings yet

- A Mediterranean Diet and Risk of Myocardial Infarction, Heart Failure and StrokeDocument6 pagesA Mediterranean Diet and Risk of Myocardial Infarction, Heart Failure and StrokeSalome GarciaNo ratings yet

- A Contemporary Review of The Relationship BetweenDocument7 pagesA Contemporary Review of The Relationship BetweenJohn SammutNo ratings yet

- Nutrients: Mediterranean Diet E Prevention, Disease Progression, and Related Mechanisms. A ReviewDocument15 pagesNutrients: Mediterranean Diet E Prevention, Disease Progression, and Related Mechanisms. A ReviewEDER YAHIR MONROY MENDOZANo ratings yet

- The Mediterranean Diet, Its Components, and Cardiovascular DiseaseDocument20 pagesThe Mediterranean Diet, Its Components, and Cardiovascular DiseaseCristian Camilo Cardona GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Ioi 40810Document7 pagesIoi 40810jimmyneutron1337No ratings yet

- Update On Importance of Diet in GoutDocument20 pagesUpdate On Importance of Diet in GoutAngela CuchimaqueNo ratings yet

- Glycemic Index, Glycemic Load, and Blood Pressure: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled TrialsDocument15 pagesGlycemic Index, Glycemic Load, and Blood Pressure: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled TrialsLisiane PerinNo ratings yet

- Adua Et Al-2017-Clinical and Translational MedicineDocument11 pagesAdua Et Al-2017-Clinical and Translational MedicineSam Asamoah SakyiNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0002870320302143 MainDocument9 pages1 s2.0 S0002870320302143 MaindeepNo ratings yet

- Meal Timing, Meal Frequency and Metabolic SyndromeDocument10 pagesMeal Timing, Meal Frequency and Metabolic SyndromebryanleonardoripacontrerasNo ratings yet

- Cardiovascular Safety Profile of Currently Available Diabetic DrugsDocument17 pagesCardiovascular Safety Profile of Currently Available Diabetic Drugsvina_nursyaidahNo ratings yet

- Strokeaha 114 006306Document5 pagesStrokeaha 114 006306prayogarathaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0022316622164783 MainDocument10 pages1 s2.0 S0022316622164783 Mainbesti verawatiNo ratings yet

- 2016 Lacroix S Nutrition in CV RehabDocument7 pages2016 Lacroix S Nutrition in CV RehabHumamuddinNo ratings yet

- Journal Hipertensi 2Document9 pagesJournal Hipertensi 2zariaNo ratings yet

- Vegetarian Diet, Seventh Day Adventists and Risk of CardiovascularDocument7 pagesVegetarian Diet, Seventh Day Adventists and Risk of CardiovascularJohn SammutNo ratings yet

- Breakfast Skipping and CADDocument5 pagesBreakfast Skipping and CADadip royNo ratings yet

- Human C-Reactive Protein and The Metabolic SyndromeDocument13 pagesHuman C-Reactive Protein and The Metabolic SyndromeEmir SaricNo ratings yet

- Dci 210017Document3 pagesDci 210017Gloria WuNo ratings yet

- Heart Disease Literature ReviewDocument9 pagesHeart Disease Literature Reviewjyzapydigip3100% (1)

- Metabolically Healthy Obesity, Metabolic Syndrome, andDocument19 pagesMetabolically Healthy Obesity, Metabolic Syndrome, anderikafebriyanarNo ratings yet

- Fish Consumption & Risk of Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality From 58 CountriesDocument19 pagesFish Consumption & Risk of Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality From 58 CountriesSY LodhiNo ratings yet

- Adherence To The Mediterranean Diet Is Associated With Lower Platelet and Leukocyte CountsDocument8 pagesAdherence To The Mediterranean Diet Is Associated With Lower Platelet and Leukocyte CountsSotir LakoNo ratings yet

- 10 DemarinDocument12 pages10 DemarinDijana Dencic NalovskaNo ratings yet

- REVIEW - Legume-Consumption-And-Cvd-Risk-A-Systematic-Review-And-Meta-AnalysisDocument10 pagesREVIEW - Legume-Consumption-And-Cvd-Risk-A-Systematic-Review-And-Meta-AnalysisLaiane GomesNo ratings yet

- Pa Nag Iot Akos 2008Document10 pagesPa Nag Iot Akos 2008Chris ChrisNo ratings yet

- Metabolic Syndrome 2017 Diabetes Reversal by Plantbased Diet A Review Article Biswaroop Roy Chowdhury Indo Vietnam Medical BoardDocument2 pagesMetabolic Syndrome 2017 Diabetes Reversal by Plantbased Diet A Review Article Biswaroop Roy Chowdhury Indo Vietnam Medical Boardali shahidNo ratings yet

- Journal Pbio 3001561Document23 pagesJournal Pbio 3001561philosophy-thoughtNo ratings yet

- C-Dieta10añosStero 230217 100842Document9 pagesC-Dieta10añosStero 230217 100842Juan Carlos Plácido OlivosNo ratings yet

- Dietary in Ammatory Potential and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease Among Men and Women in The U.SDocument13 pagesDietary in Ammatory Potential and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease Among Men and Women in The U.SRoxana CristeaNo ratings yet

- Nihms 1020972Document11 pagesNihms 1020972Carlos Alfredo Pedroza MosqueraNo ratings yet

- ADO in BRCDocument10 pagesADO in BRCVlahtNo ratings yet

- Potato Consumption Does Not Increase Blood Pressure or Incident Hypertension in 2 Cohorts of Spanish AdultsDocument10 pagesPotato Consumption Does Not Increase Blood Pressure or Incident Hypertension in 2 Cohorts of Spanish AdultsMitha Annisa PramelyaNo ratings yet

- dm2 SubtiposDocument13 pagesdm2 SubtiposCesar GuilhermeNo ratings yet

- Dietary Patterns and Longevity: EditorialDocument2 pagesDietary Patterns and Longevity: EditorialLaura MoralesNo ratings yet

- Update On Importance of Diet in Gout: ReviewDocument6 pagesUpdate On Importance of Diet in Gout: ReviewIoana IonNo ratings yet

- NutritionDocument10 pagesNutritionDani ursNo ratings yet

- Platelets Distribution Width As A Clue of Vascular Complications in Diabetic PatientsDocument3 pagesPlatelets Distribution Width As A Clue of Vascular Complications in Diabetic PatientsDr. Asaad Mohammed Ahmed BabkerNo ratings yet

- Diabetes Treatment Literature ReviewDocument7 pagesDiabetes Treatment Literature Reviewafmzatvuipwdal100% (1)

- A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Ayurvedic Herbal Preparations For HypercholesterolemiaDocument24 pagesA Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Ayurvedic Herbal Preparations For HypercholesterolemiaSotiris AnagnostopoulosNo ratings yet

- Intakes of Dietary Fiber, VegetablesDocument7 pagesIntakes of Dietary Fiber, VegetablesaureliaricidNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Ketogenic Diet On Shared Risk Factors of Cardiovascular Disease and CancerDocument22 pagesThe Effect of Ketogenic Diet On Shared Risk Factors of Cardiovascular Disease and CancerCierra NolenNo ratings yet

- Prediabetes: Why Should We Care?: Ashkan Zand, M.D. Karim Ibrahim, M.D. Bhargavi Patham, M.DDocument9 pagesPrediabetes: Why Should We Care?: Ashkan Zand, M.D. Karim Ibrahim, M.D. Bhargavi Patham, M.DCharlotte KeckhutNo ratings yet

- Current Trends in Epidemiology of Cardiovascular Disease and Cardiovascular Risk Management in Type 2 DiabetesDocument10 pagesCurrent Trends in Epidemiology of Cardiovascular Disease and Cardiovascular Risk Management in Type 2 DiabetesAKASH BISWASNo ratings yet

- Diabetes, Pancreatogenic Diabetes, and Pancreatic CancerDocument8 pagesDiabetes, Pancreatogenic Diabetes, and Pancreatic CancerTeodoraManNo ratings yet

- Eat Nuts, Live LongerDocument3 pagesEat Nuts, Live LongerHolubiac Iulian StefanNo ratings yet

- A Changing View On Sfas and Dairy: From Enemy To Friend: EditorialDocument2 pagesA Changing View On Sfas and Dairy: From Enemy To Friend: EditorialCaio Whitaker TosatoNo ratings yet

- Effect of Mediterranean Diet in Diabetes Control and Cardiovascular Risk Modification A Systematic ReviewDocument8 pagesEffect of Mediterranean Diet in Diabetes Control and Cardiovascular Risk Modification A Systematic Reviewgizi.mapsNo ratings yet

- Control GlicemicoDocument20 pagesControl GlicemicomiguelalmenarezNo ratings yet

- Vitamin D Supplementation and Prevention of Type 2 Diabetes: Original ArticleDocument11 pagesVitamin D Supplementation and Prevention of Type 2 Diabetes: Original ArticleChristine BelindaNo ratings yet

- Cardiovascular Risk in Obese Patients With Chronic PeriodontitisDocument8 pagesCardiovascular Risk in Obese Patients With Chronic PeriodontitisThais DezemNo ratings yet

- Excess Protein Intake Relative To Fiber and Cardiovascular Events in Elderly Men With Chronic Kidney DiseaseDocument6 pagesExcess Protein Intake Relative To Fiber and Cardiovascular Events in Elderly Men With Chronic Kidney Diseaseluis Gomez VallejoNo ratings yet

- Metabolic Syndrome and Insulin Resistance: Perioperative ConsiderationsDocument18 pagesMetabolic Syndrome and Insulin Resistance: Perioperative ConsiderationsBig TexNo ratings yet

- Long-Term Dietary Adherence and Changes in Dietary Intake in Coronary Patients After Intervention With A Mediterranean Diet or A Low-Fat Diet The CORDIOPREV Randomized TrialDocument12 pagesLong-Term Dietary Adherence and Changes in Dietary Intake in Coronary Patients After Intervention With A Mediterranean Diet or A Low-Fat Diet The CORDIOPREV Randomized Trialzainab asalNo ratings yet

- Partnerships BritAc & MoL Kate Rosser FrostDocument16 pagesPartnerships BritAc & MoL Kate Rosser FrostCulture CommsNo ratings yet

- Catalogo BujesDocument120 pagesCatalogo BujesJason BurtonNo ratings yet

- New TIP Course 1 DepEd Teacher PDFDocument89 pagesNew TIP Course 1 DepEd Teacher PDFLenie TejadaNo ratings yet

- Push Button Typical WiringDocument12 pagesPush Button Typical Wiringstrob1974No ratings yet

- Advancements in Concrete Design: Self-Consolidating/Self-Compacting ConcreteDocument4 pagesAdvancements in Concrete Design: Self-Consolidating/Self-Compacting ConcreteMikhaelo Alberti Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Porter's Five Forces Model of Competition-1Document14 pagesPorter's Five Forces Model of Competition-1Kanika RustagiNo ratings yet

- 2014 Table Clinic InstructionsDocument19 pages2014 Table Clinic InstructionsMaria Mercedes LeivaNo ratings yet

- C & C++ Interview Questions You'll Most Likely Be AskedDocument24 pagesC & C++ Interview Questions You'll Most Likely Be AskedVibrant PublishersNo ratings yet

- The Truth About The Truth MovementDocument68 pagesThe Truth About The Truth MovementgordoneastNo ratings yet

- Sports and Entertainment Marketing: Sample Role PlaysDocument36 pagesSports and Entertainment Marketing: Sample Role PlaysTAHA GABRNo ratings yet

- HX Escooter Repair ManualDocument3 pagesHX Escooter Repair Manualpablo montiniNo ratings yet

- Doctor Faustus: (1) Faustus As A Man of RenaissanceDocument7 pagesDoctor Faustus: (1) Faustus As A Man of RenaissanceRavindra SinghNo ratings yet

- Aventurian Herald #173Document6 pagesAventurian Herald #173Andrew CountsNo ratings yet

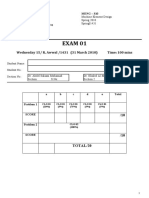

- Meng 310 Exam 01 Spring 2010Document4 pagesMeng 310 Exam 01 Spring 2010Abdulrahman AlzahraniNo ratings yet

- Throwing EventsDocument11 pagesThrowing Eventsrovel shelieNo ratings yet

- 50 HaazinuDocument6 pages50 HaazinuTheodore James TurnerNo ratings yet

- Pembelajaran Literasi Membaca Di Pondok Pesantren Sidogiri Kraton PasuruanDocument17 pagesPembelajaran Literasi Membaca Di Pondok Pesantren Sidogiri Kraton Pasuruanpriyo hartantoNo ratings yet

- Media Converter Datasheet: HighlightsDocument2 pagesMedia Converter Datasheet: HighlightsJames JamesNo ratings yet

- Codemap - 2021 No-Code Market ReportDocument34 pagesCodemap - 2021 No-Code Market ReportLogin AppsNo ratings yet

- Composition 1 S2 2020 FinalDocument46 pagesComposition 1 S2 2020 Finalelhoussaine.nahime00No ratings yet

- Objective of ECO401 (1 22) Short NotesDocument11 pagesObjective of ECO401 (1 22) Short Notesmuhammad jamilNo ratings yet

- Fyp PPT FinalDocument18 pagesFyp PPT FinalasadNo ratings yet

- Ultrasound in Obstretics PDFDocument40 pagesUltrasound in Obstretics PDFcarcobe3436100% (1)

- Marking ToolsDocument14 pagesMarking ToolsFabian NdegeNo ratings yet

- Good To Great in Gods Eyes. Good To Great in God's Eyes (Part 1) Think Great Thoughts 10 Practices Great Christians Have in CommonDocument4 pagesGood To Great in Gods Eyes. Good To Great in God's Eyes (Part 1) Think Great Thoughts 10 Practices Great Christians Have in Commonad.adNo ratings yet

Temple2018 - Mediterranean Diet

Temple2018 - Mediterranean Diet

Uploaded by

Andreea MihalacheOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Temple2018 - Mediterranean Diet

Temple2018 - Mediterranean Diet

Uploaded by

Andreea MihalacheCopyright:

Available Formats

Review Article

The Mediterranean Diet and Cardiovascular Disease

Gaps in the Evidence and Research Challenges

Norman J Temple, PhD,* Valentina Guercio, PhD,† and Alessandra Tavani, SciD‡

Abstract: In this article, we critically evaluate the evidence relating to the

meat but has small amounts of legumes and only 2 to 3 servings

effects of the Mediterranean diet (MD) on the risk of cardiovascular disease

per days of fruits and vegetables. While the MD varies from one

(CVD). Strong evidence indicating that the MD prevents CVD has come

country to another around the Mediterranean Sea, its key features

from prospective cohort studies. However, there is only weak supporting

are as follows2,3: high consumption of legumes; high consumption

evidence from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) as none have compared

of grains and cereals; high consumption of fruits, vegetables, and

subjects who follow an MD and those who do not. Instead, RCTs have tested

nuts; low consumption of meat and meat products and low or mod-

the effect of 1 or 2 features of the MD. This was the case in the Prevenciόn

erate amounts of fish; low or moderate consumption of milk and

con Dieta Mediterránea (PREDIMED) study: the major dietary change in the

dairy products; the use of olive oil as the main fat in food prepara-

intervention groups was the addition of either extravirgin olive oil or nuts.

tion (and therefore a high monounsaturated/saturated fat ratio); and

Meta-analyses generally suggest that the MD causes small favorable changes

low to moderate alcohol consumption (especially red wine consumed

in risk factors for CVD, including blood pressure, blood glucose, and waist

mainly at meals).

circumference. However, the effect on blood lipids is generally weak. The MD

Trichopoulou et al4 developed an adherence score that esti-

may also decrease several biomarkers of inflammation, including C-reactive

mates the extent to which diets adhere to the MD. This methodology

protein. The 7 key features of the MD can be divided into 2 groups. Some

is now commonly used. However, as discussed later, many variants

are clearly protective against CVD (olive oil as the main fat; high in legumes;

have occurred in the calculation of the adherence score to the MD.

high in fruits/vegetables/nuts; and low in meat/meat products and increased

in fish). However, other features of the MD have a less clear relationship with THE MEDITERRANEAN DIET AND

CVD (low/moderate alcohol use, especially red wine; high in grains/cereals; CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE

and low/moderate in milk/dairy). In conclusion, the evidence indicates that the

MD prevents CVD. There is a need for RCTs that test the effectiveness of the Epidemiological Evidence

MD for preventing CVD. Key design features for such a study are proposed. A meta-analysis of 14 prospective cohort studies reported that

Key Words: cardiovascular disease, Mediterranean diet, olive oil, nuts

people with a higher adherence to the MD are at a significantly lower

risk of CVD incidence and mortality.5 A more recent meta-analysis

(Cardiology in Review 2019;27: 127–130) of 20 cohort studies produced similar results.6 We recently carried

out a meta-analysis of cohort studies.7 Our search was conducted in

2016 (3 and 2 years, respectively, later than the previous meta-analy-

ses) and included 21 cohort studies. We calculated the pooled relative

risk for the highest versus the lowest category of the MD adherence

I nterest in the Mediterranean diet (MD) started in the 1960s when

it was realized that populations that consume the MD have much

lower rates of cardiovascular disease (CVD) than do populations from

score: for coronary heart disease (CHD) it was 0.70 (based on 11

cohort studies), for stroke it was 0.73 (6 studies), and for unspecified

CVD it was 0.81 (11 studies). We also included 5 case-control studies

Northern Europe that consume a typical Western diet. This discovery in the meta-analysis. The relative risk was 0.41 for CHD (2 studies)

sparked much research. Cohort studies reveal that persons who have and 0.13 for stroke (1 study).

a high adherence to the MD are at lower risk of CVD. These findings Observational studies are prone to important sources of error.

have been extended to total mortality and several diseases, including This may occur in the estimation of usual food intake.8 Another prob-

cancer, type 2 diabetes, and cognitive impairment.1 lem is that foods are often classified in a way that makes it prob-

The focus of this paper is CVD. The objectives are, first, to iden- lematic to accurately calculate an adherence score for the MD. For

tify gaps in the evidence regarding the relationship between the MD example, red meat and related meat products have been grouped with

and CVD; and second, to discuss the challenges in conducting research poultry in some studies, nuts have sometimes been grouped with fruit

studies that help fill the gaps in our knowledge. Much of what is argued or legumes, while some studies have failed to state the intake of milk,

here is also pertinent to other diseases related to the MD. milk products, or fish.9

The MD has major differences from the typical Western diet. Several additional problems have been identified in the calcu-

The latter is high in sugar (including sugar-sweetened beverages), lation of the adherence score for the MD:

refined cereals (such as white bread), and red meat and processed

1. The amount consumed of each class of foods is typically catego-

rized as being above or below the median intake within the stud-

From the *Centre for Science, Athabasca University, Alberta, Canada; †Depart- ied population. However, the actual amount of different types of

ment of Clinical Sciences and Community Health, Università degli Studi di food consumed varies greatly between different countries. This

Milano, Milan, Italy; and ‡IRCCS-Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche “Mario

Negri”, Milan, Italy. makes comparisons between countries difficult to interpret and is

Disclosure: The author declares no conflict of interest. a limitation when pooling results in meta-analyses.

Correspondence: Norman J. Temple, PhD, Centre for Science, Athabasca Univer- 2. Many variants have been used in the calculation of the adherence

sity, Athabasca, Alberta T9S 3A3, Canada. E-mail: normant@athabascau.ca. score to the MD.10 Zaragoza-Martí et al11 recently made a com-

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

ISSN: 1061-5377/19/2703-0127 parison of 28 different adherence scoring systems. With respect

DOI: 10.1097/CRD.0000000000000222 to alcoholic beverages, some studies have included all alcoholic

Cardiology in Review • Volume 27, Number 3, May/June 2019 www.cardiologyinreview.com | 127

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Temple et al Cardiology in Review • Volume 27, Number 3, May/June 2019

beverages, some have included wine only, while others have in- randomly assigned 7400 persons at high risk for CVD (but who were

cluded red wine only. Seemingly, minor changes can have a strong free of CVD) to 1 of 3 groups: MD plus extravirgin olive oil (EVOO),

impact on the findings concerning the relationship between the MD plus mixed nuts, and a control group who were advised to reduce

adherence score and the risk of disease. This was demonstrated by dietary fat. An editorial that accompanied the paper pointed out that

Agnoli et al9 in an investigation of the relationship between the MD the diet consumed by the control group was essentially a variation

and risk of stroke. Two scoring systems were used: (1) the original of the MD.22

method devised by Trichopoulous et al4 (the Greek Mediterranean The following data were obtained from Tables S6 and S7 of the

Index score); and (2) an adaptation of this for the Italian diet (the supplementary appendix of the PREDIMED publication (available

Italian Mediterranean Index score). There are several differences from the authors). The fat content of the diet eaten by the control group

in the way the 2 scores were calculated. For example, the Italian was only slightly lower than the 2 intervention diets (37% vs 41% of

score added olive oil and butter as separate components instead energy). The intake of saturated fat was marginally higher in the inter-

of using monounsaturated-to-saturated fat ratio and used tertiles vention diets (by 0.2% of energy) while dietary fiber was higher (by

of intake rather the median intake. These differences resulted in 1.7 g/d in the EVOO group and 3.3 g/d in the nuts group). The total

very different conclusions: the MD adherence score was inversely intake of fruit and vegetables was higher in the intervention diets (by

related to the risk of stroke using the Italian index but not with the 0.2 servings/d in the EVOO group and by 1.1 servings/d in the nuts

Greek index. group). There was no difference in intake of meat/meat products, whole

3. Foods may be misclassified. One key component of the MD is a grains, or refined grains. The 2 intervention groups (compared with the

high consumption of grains and cereals; all grains are considered control group) had a modestly higher intake of legumes and fish, by

together, both whole grains and refined grains. However, whole 0.4 and 0.3 servings per week, respectively. By comparison, in order to

grains rather than all grains have sometimes been used as part of receive 1 point for legumes and fish on the adherence scale used by the

the MD adherence score. In the meta-analysis carried out by Sofi PREDIMED researchers, a subject must consume 3 or more servings

et al5,12,13 on the association between the MD and risk of total mor- per week of each food.23 The dominant difference between the 3 diets

tality, CVD, and cancer, 6 of 24 of the cohort studies based their was in a single food. At the end of follow-up, the average energy intake

estimation of the adherence score on whole grains rather than re- from olive oil was 22.0% in the group receiving EVOO (vs 16.4% in

fined grains. However, strong evidence suggests that the 2 types the control group); the average energy intake from nuts was 8.2% in

of grains have distinct effects on the risk of CVD (and of other the group receiving nuts (vs 1.6% in the control group). This RCT was

diseases): whole grains are protective, whereas refined grains are therefore, in essence, a study of whether CVD can be reduced by either

not protective and may even increase the risk of CVD.14–16 Basing (1) an increased intake of olive oil, combined with the replacement of

the estimation of the adherence score on whole grains rather than regular olive oil by EVOO; or (2) an increased intake of nuts. Remark-

all grains is likely to exaggerate the magnitude of the inverse as- ably, CVD was reduced by approximately 30% in both intervention

sociation between the adherence score and the risk of CVD. This groups after 4.8 years of follow-up.

can materially affect the results, especially where most grains are This study is often cited as demonstrating that the MD pre-

refined. That is the case in many countries, such as the United vents CVD. However, apart from the large increase in intake of

States.17 A survey in Italy reported that the mean intake of whole EVOO and nuts, the other dietary changes were either small or neg-

grains among Italian adults is only 3.7 g/d.18 ligible, and it is therefore very unlikely that they could account for

more than a small proportion of the dramatic reduction in risk of

Another problem with the research evidence is that meta-anal- CVD. For that reason, the most plausible interpretation of the find-

yses and systematic reviews that have evaluated the effect of the MD ings is that the addition of EVOO or nuts to the diet is highly effective

on risk of CVD have often failed to follow proper procedures.19 for preventing CVD. The most likely explanation for the beneficial

action of these foods is their content of phytochemicals.24–26 Nuts are

Randomized Controlled Trials also rich in polyunsaturated fat, including alpha-linolenic acid (an

The effectiveness of the MD for the prevention of CVD has n-3 fatty acid).

also been investigated in randomized controlled trials (RCTs). A

Cochrane review published in 2013 assessed this evidence based on

11 RCTs that were carried out on healthy adults and adults at high THE MEDITERRANEAN DIET AND RISK FACTORS

risk of CVD.20 However, the review classified intervention diets as FOR CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE

being an “MD” even if they included only 2 of the 7 features of the The impact of the MD on risk factors for CVD has been inves-

MD. A key finding is that no well-designed RCT was found that actu- tigated in both observational studies (cohort studies and case-control

ally investigated whether a diet that contains most or all of the com- studies) and RCTs. Dinu et al1 recently published an analysis of

ponents of the MD produces a lower risk of CVD when compared the available findings. The MD often brings about small reductions

with a non-MD diet. in blood pressure, body weight and waist circumference, and total

The following RCT illustrates the limitations of the findings blood cholesterol. It may also lower the blood glucose and improve

of the Cochrane review. The Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) was glycemic control. Weaker evidence suggests that the MD may also

included in the review as it provided some limited evidence.21 The help lower the blood triglyceride level and increase the high-density

WHI was carried out in the United States and investigated whether lipoprotein cholesterol. However, there seems to be no impact on the

a diet that has an increased amount of fruit and vegetables and of blood level of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Several of these

cereals is effective for preventing CVD in 48,800 postmenopausal risk factors are known collectively as the metabolic syndrome. These

women. This dietary change represents a partial move from a typi- include increased blood pressure and waist circumference, elevated

cal American diet to an MD. However, the diet also reduced the blood levels of triglyceride and blood glucose, and a depressed blood

consumption of monounsaturated fat which is a step away from level of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Adherence to the MD

the MD. No reduction in risk of CVD was seen after 8 years of was found to have a weak inverse association with the development

follow-up. of the metabolic syndrome.

The RCT that has attracted the most attention is Prevenciόn C-reactive protein is a biomarker of inflammation and is asso-

con Dieta Mediterránea (PREDIMED).2 This study was excluded ciated with the risk of CVD.27 The MD leads to a decrease in C-reac-

from the above Cochrane review. The study, conducted in Spain, tive protein, as well as several other biomarkers of inflammation.1

128 | www.cardiologyinreview.com © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Cardiology in Review • Volume 27, Number 3, May/June 2019 Mediterranean Diet and CVD

Taken as a whole, the above evidence indicates that the CHD.15,31 However, foods that are often rich in saturated fat, espe-

MD brings about favorable changes in the level of a range of risk cially meat, are linked to the risk of CHD.15

factors for CVD. However, findings have not been consistent.

Various factors may account for these inconsistencies, including 1. High consumption of legumes

that the “MD” in many studies had only 2 or 3 of the 7 features 2. High consumption of fruits, vegetables, and nuts

of the MD. 3. Low consumption of meat and meat products and increased con-

sumption of fish.

AN OVERVIEW OF THE EVIDENCE Much evidence demonstrates that these last 3 features of the

MD are protective against CVD.15,16

There is little doubt that if everyone who presently eats a West-

ern diet switched to the MD, rates of CVD would be reduced. However, Components of the Mediterranean Diet Where the

there are notable gaps and weaknesses in the evidence. The strongest Relationship With Risk of CVD Is Complex

evidence demonstrating the efficacy of the MD for the prevention

of CVD has come from cohort studies. However, those studies have 1. Low to moderate alcohol consumption (especially red wine).

various limitations. No RCT has been carried out that clearly demon- Numerous epidemiological studies have reported that alcohol

strates that the MD prevents CVD. This gap in the evidence is of major consumption, in moderation, is protective again CHD. There has

importance as a well-designed RCT is potentially a powerful tool for been much speculation that wine, particularly red wine, may be

investigating the extent to which the MD prevents CVD. Instead, cur- more potent than beer or spirits in preventing CHD. This is largely

rently available RCTs, such as the PREDIMED study, tested only 2 or based on findings from ecological studies (ie, countries with a

3 components of the MD. This problem extends to some meta-analyses high intake of wine tend to have relatively low rates of CHD).32

of RCTs: even if only 2 of the 7 key features of the MD were part of As France is the country most closely associated with this obser-

the dietary change, then the diet as a whole was classed as an MD.20 vation, it has often been referred to as the “French paradox.” The

Moreover, no RCT has tested whether a complete MD diet favorably popularity of red wine in that country has been suggested as be-

affects risk factors for CVD. ing responsible for this. However, findings from case-control and

Because of these various gaps and weaknesses in the evidence, cohort studies show no clear trend for one type of alcohol to be

there is still much uncertainty over important questions, in particular more consistently associated with protection from CHD.32–34 This

the magnitude of the decrease in risk of CVD and which components suggests, therefore, that all types of alcoholic beverages—wine,

of the MD are most responsible for the benefit. beer, and spirits—are equally effective for the prevention of CHD.

But in one respect, red wine, as part of the MD, may indeed

WHICH FOODS IN THE MEDITERRANEAN DIET be protective against CVD: it is typically consumed in moderate

PREVENT CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE? amounts before or during meals rather than in large quantities at a

Although the research evidence strongly supports the health single session (“binge drinking”). This drinking pattern is associated

benefits of the MD in comparison with the Western diet, this does with a lower risk of CHD.35,36

not imply that the MD is the ideal diet for the prevention of CVD.

Indeed, common sense tells us that while it is well within the laws of 1. High consumption of grains and cereals. The MD combines

chance that the population of a particular geographical region con- together all types of grain, both whole grains and refined

sumes a diet that leads to low rates of CVD, it is extremely unlikely grains. But, as noted earlier, the effects of whole grains and

that a population will fortuitously select a diet that is optimal for the refined grains on CVD risk are quite distinct. Based on these

prevention of CVD. Not surprisingly, therefore, a careful evaluation considerations, it is therefore unwarranted to conclude that

of the components of the MD reveals that while several components when a study shows an inverse association between the ad-

of the diet are protective against CVD, others are not. herence score to the MD and risk of CVD, this implies that all

The introduction to this paper lists the 7 features of the MD. grains, including refined grains, are protective against CVD.

These can be divided into 2 distinct groups based on the totality of 2. Moderate consumption of milk and dairy products. Our best evi-

the research evidence regarding their relationship with CVD. dence is that milk and other dairy foods have little association

with CVD although confirmation of this is required.15 This sug-

Components of the Mediterranean Diet That Are gests that a relatively high intake of milk and dairy products does

Protective Against CVD not increase risk of CVD.

1. The use of olive oil as the main fat in food preparation. Strong The evidence examined above demonstrates that it is an

evidence indicates that olive oil is protective against CVD.28,29 oversimplification to characterize the MD as being ideal for the

Olive oil appears to exert beneficial effects on endothelial func- prevention of MD. It is more accurate to say that several compo-

tion and on markers of inflammation.30 The PREDIMED study nents of the MD are protective against CVD, whereas others are

suggests that EVOO may have an especially strong protective not. A recent review by D’Alessandro and De Pergola10 came to a

benefit against CVD.2 similar conclusion. This has implications for the design of future

RCTs in this area.

A feature of the MD diet is its relatively high content of mono-

unsaturated fat and relatively low content of saturated fat. This is

because the MD usually includes much olive oil (which has a high DESIGN OF FUTURE RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED

content of monounsaturated fat) and relatively low amounts of foods TRIALS

rich in saturated fat (meat, meat products, milk, and dairy products). As stressed earlier, a major gap in the evidence concerning

However, it is a mistake to make the assumption that these fats have the efficacy of the MD in the prevention of CVD is that no RCT has

more than a minor effect on the risk of CVD. A more plausible inter- been carried out that clearly demonstrates this. Carrying out such

pretation of the evidence is that foods rich in monounsaturated are a study should therefore be a priority. Based on the evidence and

protective while foods rich in saturated fat increase risk. Indeed, cur- arguments presented in this paper, an RCT should have the follow-

rent evidence indicates that saturated fat has little association with ing design features:

© 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved. www.cardiologyinreview.com | 129

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Temple et al Cardiology in Review • Volume 27, Number 3, May/June 2019

1. The intervention group would be instructed to consume a modified 12. Sofi F, Abbate R, Gensini GF, et al. Accruing evidence on benefits of adher-

MD that emphasizes only those features of the MD where there is ence to the Mediterranean diet on health: an updated systematic review and

meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92:1189–1196.

strong evidence for a protective benefit against CVD. Accordingly, the

13. Sofi F, Cesari F, Abbate R, et al. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and health

intervention group would be instructed to base their diet mainly on status: meta-analysis. BMJ. 2008;337:a1344.

legumes (such as, beans, lentils, and peas), fruits, vegetables, nuts, 14. Tavani A, Bosetti C, Negri E, et al. Carbohydrates, dietary glycaemic

and whole grains (but low in refined grains). The diet should be low in load and glycaemic index, and risk of acute myocardial infarction. Heart.

meat/meat products but increased in fish. Olive oil, especially EVOO, 2003;89:722–726.

would serve as the main fat. The intake of added sugar, especially 15. Mozaffarian D. Dietary and policy priorities for cardiovascular disease, diabe-

sugar-sweetened beverages, should be much reduced. tes, and obesity: a comprehensive review. Circulation. 2016;133:187–225.

2. Carrying out an RCT in a Mediterranean country creates problems as 16. Bechthold A, Boeing H, Schwedhelm C, et al. Food groups and risk of coronary

most subjects are likely to be consuming a diet similar to the MD. This heart disease, stroke and heart failure: a systematic review and dose-response

meta-analysis of prospective studies. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2017;57:1–20.

was the problem with the PREDIMED study that was done in Spain.

17. Krebs-Smith SM, Reedy J, Bosire C. Healthfulness of the U.S. food sup-

The study population should, therefore, be one that consumes a typical ply: little improvement despite decades of dietary guidance. Am J Prev Med.

Western diet rather than an MD. For that reason, the trial should be 2010;38:472–477.

done in Northern Europe or North America. Martínez-González et al37 18. Sette S, D’Addezio L, Piccinelli R, et al. Intakes of whole grain in an Italian

suggested how the MD could be adapted to North America. Their sug- sample of children, adolescents and adults. Eur J Nutr. 2017;56:521–533.

gestions are also highly valid for Northern Europe. 19. Huedo-Medina TB, Garcia M, Bihuniak JD, et al. Methodologic quality of

meta-analyses and systematic reviews on the Mediterranean diet and cardio-

A major challenge in conducting RCTs along the lines sug- vascular disease outcomes: a review. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;103:841–850.

gested above is ensuring adherence to the prescribed dietary changes. 20. Rees K, Hartley L, Flowers N, et al. ‘Mediterranean’ dietary pattern for the

The WHI provides some assurance that such RCTs are feasible.21 The primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

subjects in that study followed several major dietary changes and 2013;8:CD009825.

adhered to the intervention diet for 8 years. 21. Howard BV, Van Horn L, Hsia J, et al. Low-fat dietary pattern and risk of

cardiovascular disease: the Women’s Health Initiative Randomized Controlled

Dietary Modification Trial. JAMA. 2006;295:655–666.

CONCLUSIONS 22. Appel LJ, Van Horn L. Did the PREDIMED trial test a Mediterranean diet? N

Engl J Med. 2013;368:1353–1354.

The MD is effective for the prevention of CVD. However, it is

23. Schröder H, Fitó M, Estruch R, et al. A short screener is valid for assessing

an error to see the MD as an optimal diet. Strong evidence indicates Mediterranean diet adherence among older Spanish men and women. J Nutr.

that a diet that is closer to optimal is a modified MD based on foods 2011;141:1140–1145.

clearly shown to be protective benefit against CVD. There are vari- 24. Visioli F, Galli C. Biological properties of olive oil phytochemicals. Crit Rev

ous gaps and weaknesses in the evidence concerning the relationship Food Sci Nutr. 2002;42:209–221.

between the MD and CVD. There is a need for improved methodol- 25. Bolling BW, Chen CY, McKay DL, et al. Tree nut phytochemicals: composi-

ogy in the conduct of observational studies that investigate how the tion, antioxidant capacity, bioactivity, impact factors. A systematic review of

MD affects the risk of CVD and risk factors for CVD. A research almonds, brazils, cashews, hazelnuts, macadamias, pecans, pine nuts, pista-

chios and walnuts. Nutr Res Rev. 2011;24:244–275.

priority should be the launching of a well-planned RCT that tests the

26. Pérez-Jiménez J, Neveu V, Vos F, et al. Identification of the 100 richest dietary

effectiveness of a modified MD for the prevention of CVD. sources of polyphenols: an application of the Phenol-Explorer database. Eur J

Clin Nutr. 2010;64(suppl 3):S112–S120.

REFERENCES 27. Ridker PM. C-reactive protein and the prediction of cardiovascular events

1. Dinu M, Pagliai G, Casini A, et al. Mediterranean diet and multiple health among those at intermediate risk: moving an inflammatory hypothesis toward

outcomes: an umbrella review of meta-analyses of observational studies and consensus. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:2129–2138.

randomised trials. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2018;72:30–43. 28. Buckland G, Gonzalez CA. The role of olive oil in disease prevention: a focus

2. Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvadó J, et al; PREDIMED Study Investigators. on the recent epidemiological evidence from cohort studies and dietary inter-

Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet. N vention trials. Br J Nutr. 2015;113(suppl 2):S94–S101.

Engl J Med. 2013;368:1279–1290. 29. Martínez-González MA, Dominguez LJ, Delgado-Rodríguez M. Olive oil

3. Willett WC, Sacks F, Trichopoulou A, et al. Mediterranean diet pyramid: a cul- consumption and risk of CHD and/or stroke: a meta-analysis of case-control,

tural model for healthy eating. Am J Clin Nutr. 1995;61(6 suppl):1402S–1406S. cohort and intervention studies. Br J Nutr. 2014;112:248–259.

4. Trichopoulou A, Costacou T, Bamia C, et al. Adherence to a Mediterranean 30. Schwingshackl L, Christoph M, Hoffmann G. Effects of olive oil on mark-

diet and survival in a Greek population. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2599–2608. ers of inflammation and endothelial function: a systematic review and meta-

5. Sofi F, Macchi C, Abbate R, et al. Mediterranean diet and health status: an analysis. Nutrients. 2015;7:7651–7675.

updated meta-analysis and a proposal for a literature-based adherence score. 31. Temple NJ. Fat, sugar, whole grains and heart disease: 50 years of confusion.

Public Health Nutr. 2014;17:2769–2782. Nutrients. 2018;10:39.

6. Grosso G, Marventano S, Yang J, et al. A comprehensive meta-analysis on 32. Rimm EB, Klatsky A, Grobbee D, et al. Review of moderate alcohol consump-

evidence of Mediterranean diet and cardiovascular disease: are individual tion and reduced risk of coronary heart disease: is the effect due to beer, wine,

components equal? Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2017;57:3218–3232. or spirits. BMJ. 1996;312:731–736.

7. Rosato V, Temple NJ, La Vecchia C, et al. Mediterranean diet and cardiovas- 33. Mukamal KJ, Jensen MK, Grønbaek M, et al. Drinking frequency, mediating

cular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. biomarkers, and risk of myocardial infarction in women and men. Circulation.

Eur J Nutr. 2017. doi: 10.1007/s00394-017-1582-0. 2005;112:1406–1413.

8. Jacobs DR. Challenges in research in nutritional epidemiology. In: Temple 34. Tavani A, Bertuzzi M, Negri E, et al. Alcohol, smoking, coffee and risk of non-

NJ, Wilson T, Jacobs DR, eds. Nutritional Health: Strategies for Disease fatal acute myocardial infarction in Italy. Eur J Epidemiol. 2001;17:1131–1137.

Prevention. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Humana Press; 2012;29–42. 35. Augustin LS, Gallus S, Tavani A, et al. Alcohol consumption and acute myo-

9. Agnoli C, Krogh V, Grioni S, et al. A priori-defined dietary patterns are cardial infarction: a benefit of alcohol consumed with meals? Epidemiology.

associated with reduced risk of stroke in a large Italian cohort. J Nutr. 2004;15:767–769.

2011;141:1552–1558. 36. Hernandez-Hernandez A, Gea A, Ruiz-Canela M, et al. Mediterranean alco-

10. D’Alessandro A, De Pergola G. Mediterranean diet and cardiovascular disease: hol-drinking pattern and the incidence of cardiovascular disease and cardio-

a critical evaluation of a priori dietary indexes. Nutrients. 2015;7:7863–7888. vascular mortality: the SUN Project. Nutrients. 2015;7:9116–9126.

11. Zaragoza-Martí A, Cabañero-Martínez MJ, Hurtado-Sánchez JA, et al.

37. Martínez-González MA, Hershey MS, Zazpe I, et al Transferability of the

Evaluation of Mediterranean diet adherence scores: a systematic review. BMJ Mediterranean diet to non-Mediterranean countries. What is and what is not

Open. 2018;8:e019033. the Mediterranean diet. Nutrients. 2017;9:1226.

130 | www.cardiologyinreview.com © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

You might also like

- Solution Manual of Modern Semiconductor Devices For Integrated Circuits (Chenming Calvin Hu)Document122 pagesSolution Manual of Modern Semiconductor Devices For Integrated Circuits (Chenming Calvin Hu)hu leo86% (7)

- CH 10Document30 pagesCH 10Narendran KumaravelNo ratings yet

- Credit Policy Sample: Accounts Receivable AnalysisDocument3 pagesCredit Policy Sample: Accounts Receivable AnalysisAlinaNo ratings yet

- Giraffe Blood CirculationDocument9 pagesGiraffe Blood Circulationthalita asriandinaNo ratings yet

- 4 Roadtec 600 Cummins QSXDocument24 pages4 Roadtec 600 Cummins QSXdavidNo ratings yet

- Article: Effects of A Mediterranean-Style Diet On Cardiovascular Risk FactorsDocument15 pagesArticle: Effects of A Mediterranean-Style Diet On Cardiovascular Risk FactorsBunga dewanggi NugrohoNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0002916522012357 MainDocument9 pages1 s2.0 S0002916522012357 MainSalvia Elvaretta HarefaNo ratings yet

- Risk Factors Associated With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and The Frequency of Nafld Affected PatientsDocument5 pagesRisk Factors Associated With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and The Frequency of Nafld Affected PatientsIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Anti Inflammatory Effects of The Mediterranean Diet The Experience of The Predimed StudyDocument8 pagesAnti Inflammatory Effects of The Mediterranean Diet The Experience of The Predimed StudyAprilia MutiaraNo ratings yet

- The Role of Diet Therapy and ECG Monitoring in Preventing Cardiovascular Diseases in Diabetes Mellitus: A ReviewDocument4 pagesThe Role of Diet Therapy and ECG Monitoring in Preventing Cardiovascular Diseases in Diabetes Mellitus: A ReviewIJRDPM JOURNALNo ratings yet

- A Mediterranean Diet and Risk of Myocardial Infarction, Heart Failure and StrokeDocument6 pagesA Mediterranean Diet and Risk of Myocardial Infarction, Heart Failure and StrokeSalome GarciaNo ratings yet

- A Contemporary Review of The Relationship BetweenDocument7 pagesA Contemporary Review of The Relationship BetweenJohn SammutNo ratings yet

- Nutrients: Mediterranean Diet E Prevention, Disease Progression, and Related Mechanisms. A ReviewDocument15 pagesNutrients: Mediterranean Diet E Prevention, Disease Progression, and Related Mechanisms. A ReviewEDER YAHIR MONROY MENDOZANo ratings yet

- The Mediterranean Diet, Its Components, and Cardiovascular DiseaseDocument20 pagesThe Mediterranean Diet, Its Components, and Cardiovascular DiseaseCristian Camilo Cardona GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Ioi 40810Document7 pagesIoi 40810jimmyneutron1337No ratings yet

- Update On Importance of Diet in GoutDocument20 pagesUpdate On Importance of Diet in GoutAngela CuchimaqueNo ratings yet

- Glycemic Index, Glycemic Load, and Blood Pressure: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled TrialsDocument15 pagesGlycemic Index, Glycemic Load, and Blood Pressure: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled TrialsLisiane PerinNo ratings yet

- Adua Et Al-2017-Clinical and Translational MedicineDocument11 pagesAdua Et Al-2017-Clinical and Translational MedicineSam Asamoah SakyiNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0002870320302143 MainDocument9 pages1 s2.0 S0002870320302143 MaindeepNo ratings yet

- Meal Timing, Meal Frequency and Metabolic SyndromeDocument10 pagesMeal Timing, Meal Frequency and Metabolic SyndromebryanleonardoripacontrerasNo ratings yet

- Cardiovascular Safety Profile of Currently Available Diabetic DrugsDocument17 pagesCardiovascular Safety Profile of Currently Available Diabetic Drugsvina_nursyaidahNo ratings yet

- Strokeaha 114 006306Document5 pagesStrokeaha 114 006306prayogarathaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0022316622164783 MainDocument10 pages1 s2.0 S0022316622164783 Mainbesti verawatiNo ratings yet

- 2016 Lacroix S Nutrition in CV RehabDocument7 pages2016 Lacroix S Nutrition in CV RehabHumamuddinNo ratings yet

- Journal Hipertensi 2Document9 pagesJournal Hipertensi 2zariaNo ratings yet

- Vegetarian Diet, Seventh Day Adventists and Risk of CardiovascularDocument7 pagesVegetarian Diet, Seventh Day Adventists and Risk of CardiovascularJohn SammutNo ratings yet

- Breakfast Skipping and CADDocument5 pagesBreakfast Skipping and CADadip royNo ratings yet

- Human C-Reactive Protein and The Metabolic SyndromeDocument13 pagesHuman C-Reactive Protein and The Metabolic SyndromeEmir SaricNo ratings yet

- Dci 210017Document3 pagesDci 210017Gloria WuNo ratings yet

- Heart Disease Literature ReviewDocument9 pagesHeart Disease Literature Reviewjyzapydigip3100% (1)

- Metabolically Healthy Obesity, Metabolic Syndrome, andDocument19 pagesMetabolically Healthy Obesity, Metabolic Syndrome, anderikafebriyanarNo ratings yet

- Fish Consumption & Risk of Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality From 58 CountriesDocument19 pagesFish Consumption & Risk of Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality From 58 CountriesSY LodhiNo ratings yet

- Adherence To The Mediterranean Diet Is Associated With Lower Platelet and Leukocyte CountsDocument8 pagesAdherence To The Mediterranean Diet Is Associated With Lower Platelet and Leukocyte CountsSotir LakoNo ratings yet

- 10 DemarinDocument12 pages10 DemarinDijana Dencic NalovskaNo ratings yet

- REVIEW - Legume-Consumption-And-Cvd-Risk-A-Systematic-Review-And-Meta-AnalysisDocument10 pagesREVIEW - Legume-Consumption-And-Cvd-Risk-A-Systematic-Review-And-Meta-AnalysisLaiane GomesNo ratings yet

- Pa Nag Iot Akos 2008Document10 pagesPa Nag Iot Akos 2008Chris ChrisNo ratings yet

- Metabolic Syndrome 2017 Diabetes Reversal by Plantbased Diet A Review Article Biswaroop Roy Chowdhury Indo Vietnam Medical BoardDocument2 pagesMetabolic Syndrome 2017 Diabetes Reversal by Plantbased Diet A Review Article Biswaroop Roy Chowdhury Indo Vietnam Medical Boardali shahidNo ratings yet

- Journal Pbio 3001561Document23 pagesJournal Pbio 3001561philosophy-thoughtNo ratings yet

- C-Dieta10añosStero 230217 100842Document9 pagesC-Dieta10añosStero 230217 100842Juan Carlos Plácido OlivosNo ratings yet

- Dietary in Ammatory Potential and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease Among Men and Women in The U.SDocument13 pagesDietary in Ammatory Potential and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease Among Men and Women in The U.SRoxana CristeaNo ratings yet

- Nihms 1020972Document11 pagesNihms 1020972Carlos Alfredo Pedroza MosqueraNo ratings yet

- ADO in BRCDocument10 pagesADO in BRCVlahtNo ratings yet

- Potato Consumption Does Not Increase Blood Pressure or Incident Hypertension in 2 Cohorts of Spanish AdultsDocument10 pagesPotato Consumption Does Not Increase Blood Pressure or Incident Hypertension in 2 Cohorts of Spanish AdultsMitha Annisa PramelyaNo ratings yet

- dm2 SubtiposDocument13 pagesdm2 SubtiposCesar GuilhermeNo ratings yet

- Dietary Patterns and Longevity: EditorialDocument2 pagesDietary Patterns and Longevity: EditorialLaura MoralesNo ratings yet

- Update On Importance of Diet in Gout: ReviewDocument6 pagesUpdate On Importance of Diet in Gout: ReviewIoana IonNo ratings yet

- NutritionDocument10 pagesNutritionDani ursNo ratings yet

- Platelets Distribution Width As A Clue of Vascular Complications in Diabetic PatientsDocument3 pagesPlatelets Distribution Width As A Clue of Vascular Complications in Diabetic PatientsDr. Asaad Mohammed Ahmed BabkerNo ratings yet

- Diabetes Treatment Literature ReviewDocument7 pagesDiabetes Treatment Literature Reviewafmzatvuipwdal100% (1)

- A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Ayurvedic Herbal Preparations For HypercholesterolemiaDocument24 pagesA Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Ayurvedic Herbal Preparations For HypercholesterolemiaSotiris AnagnostopoulosNo ratings yet

- Intakes of Dietary Fiber, VegetablesDocument7 pagesIntakes of Dietary Fiber, VegetablesaureliaricidNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Ketogenic Diet On Shared Risk Factors of Cardiovascular Disease and CancerDocument22 pagesThe Effect of Ketogenic Diet On Shared Risk Factors of Cardiovascular Disease and CancerCierra NolenNo ratings yet

- Prediabetes: Why Should We Care?: Ashkan Zand, M.D. Karim Ibrahim, M.D. Bhargavi Patham, M.DDocument9 pagesPrediabetes: Why Should We Care?: Ashkan Zand, M.D. Karim Ibrahim, M.D. Bhargavi Patham, M.DCharlotte KeckhutNo ratings yet

- Current Trends in Epidemiology of Cardiovascular Disease and Cardiovascular Risk Management in Type 2 DiabetesDocument10 pagesCurrent Trends in Epidemiology of Cardiovascular Disease and Cardiovascular Risk Management in Type 2 DiabetesAKASH BISWASNo ratings yet

- Diabetes, Pancreatogenic Diabetes, and Pancreatic CancerDocument8 pagesDiabetes, Pancreatogenic Diabetes, and Pancreatic CancerTeodoraManNo ratings yet

- Eat Nuts, Live LongerDocument3 pagesEat Nuts, Live LongerHolubiac Iulian StefanNo ratings yet

- A Changing View On Sfas and Dairy: From Enemy To Friend: EditorialDocument2 pagesA Changing View On Sfas and Dairy: From Enemy To Friend: EditorialCaio Whitaker TosatoNo ratings yet

- Effect of Mediterranean Diet in Diabetes Control and Cardiovascular Risk Modification A Systematic ReviewDocument8 pagesEffect of Mediterranean Diet in Diabetes Control and Cardiovascular Risk Modification A Systematic Reviewgizi.mapsNo ratings yet

- Control GlicemicoDocument20 pagesControl GlicemicomiguelalmenarezNo ratings yet

- Vitamin D Supplementation and Prevention of Type 2 Diabetes: Original ArticleDocument11 pagesVitamin D Supplementation and Prevention of Type 2 Diabetes: Original ArticleChristine BelindaNo ratings yet

- Cardiovascular Risk in Obese Patients With Chronic PeriodontitisDocument8 pagesCardiovascular Risk in Obese Patients With Chronic PeriodontitisThais DezemNo ratings yet

- Excess Protein Intake Relative To Fiber and Cardiovascular Events in Elderly Men With Chronic Kidney DiseaseDocument6 pagesExcess Protein Intake Relative To Fiber and Cardiovascular Events in Elderly Men With Chronic Kidney Diseaseluis Gomez VallejoNo ratings yet

- Metabolic Syndrome and Insulin Resistance: Perioperative ConsiderationsDocument18 pagesMetabolic Syndrome and Insulin Resistance: Perioperative ConsiderationsBig TexNo ratings yet

- Long-Term Dietary Adherence and Changes in Dietary Intake in Coronary Patients After Intervention With A Mediterranean Diet or A Low-Fat Diet The CORDIOPREV Randomized TrialDocument12 pagesLong-Term Dietary Adherence and Changes in Dietary Intake in Coronary Patients After Intervention With A Mediterranean Diet or A Low-Fat Diet The CORDIOPREV Randomized Trialzainab asalNo ratings yet

- Partnerships BritAc & MoL Kate Rosser FrostDocument16 pagesPartnerships BritAc & MoL Kate Rosser FrostCulture CommsNo ratings yet

- Catalogo BujesDocument120 pagesCatalogo BujesJason BurtonNo ratings yet

- New TIP Course 1 DepEd Teacher PDFDocument89 pagesNew TIP Course 1 DepEd Teacher PDFLenie TejadaNo ratings yet

- Push Button Typical WiringDocument12 pagesPush Button Typical Wiringstrob1974No ratings yet

- Advancements in Concrete Design: Self-Consolidating/Self-Compacting ConcreteDocument4 pagesAdvancements in Concrete Design: Self-Consolidating/Self-Compacting ConcreteMikhaelo Alberti Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Porter's Five Forces Model of Competition-1Document14 pagesPorter's Five Forces Model of Competition-1Kanika RustagiNo ratings yet

- 2014 Table Clinic InstructionsDocument19 pages2014 Table Clinic InstructionsMaria Mercedes LeivaNo ratings yet

- C & C++ Interview Questions You'll Most Likely Be AskedDocument24 pagesC & C++ Interview Questions You'll Most Likely Be AskedVibrant PublishersNo ratings yet

- The Truth About The Truth MovementDocument68 pagesThe Truth About The Truth MovementgordoneastNo ratings yet

- Sports and Entertainment Marketing: Sample Role PlaysDocument36 pagesSports and Entertainment Marketing: Sample Role PlaysTAHA GABRNo ratings yet

- HX Escooter Repair ManualDocument3 pagesHX Escooter Repair Manualpablo montiniNo ratings yet

- Doctor Faustus: (1) Faustus As A Man of RenaissanceDocument7 pagesDoctor Faustus: (1) Faustus As A Man of RenaissanceRavindra SinghNo ratings yet

- Aventurian Herald #173Document6 pagesAventurian Herald #173Andrew CountsNo ratings yet

- Meng 310 Exam 01 Spring 2010Document4 pagesMeng 310 Exam 01 Spring 2010Abdulrahman AlzahraniNo ratings yet

- Throwing EventsDocument11 pagesThrowing Eventsrovel shelieNo ratings yet

- 50 HaazinuDocument6 pages50 HaazinuTheodore James TurnerNo ratings yet

- Pembelajaran Literasi Membaca Di Pondok Pesantren Sidogiri Kraton PasuruanDocument17 pagesPembelajaran Literasi Membaca Di Pondok Pesantren Sidogiri Kraton Pasuruanpriyo hartantoNo ratings yet

- Media Converter Datasheet: HighlightsDocument2 pagesMedia Converter Datasheet: HighlightsJames JamesNo ratings yet

- Codemap - 2021 No-Code Market ReportDocument34 pagesCodemap - 2021 No-Code Market ReportLogin AppsNo ratings yet

- Composition 1 S2 2020 FinalDocument46 pagesComposition 1 S2 2020 Finalelhoussaine.nahime00No ratings yet

- Objective of ECO401 (1 22) Short NotesDocument11 pagesObjective of ECO401 (1 22) Short Notesmuhammad jamilNo ratings yet

- Fyp PPT FinalDocument18 pagesFyp PPT FinalasadNo ratings yet

- Ultrasound in Obstretics PDFDocument40 pagesUltrasound in Obstretics PDFcarcobe3436100% (1)

- Marking ToolsDocument14 pagesMarking ToolsFabian NdegeNo ratings yet

- Good To Great in Gods Eyes. Good To Great in God's Eyes (Part 1) Think Great Thoughts 10 Practices Great Christians Have in CommonDocument4 pagesGood To Great in Gods Eyes. Good To Great in God's Eyes (Part 1) Think Great Thoughts 10 Practices Great Christians Have in Commonad.adNo ratings yet