Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ekim, H. y Tuncer, M. (2009) - Manejo de Lesiones Traumáticas de La Arteria Braquial Informe de 49 Pacientes

Ekim, H. y Tuncer, M. (2009) - Manejo de Lesiones Traumáticas de La Arteria Braquial Informe de 49 Pacientes

Uploaded by

Edgar Geovanny Cardenas FigueroaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Ekim, H. y Tuncer, M. (2009) - Manejo de Lesiones Traumáticas de La Arteria Braquial Informe de 49 Pacientes

Ekim, H. y Tuncer, M. (2009) - Manejo de Lesiones Traumáticas de La Arteria Braquial Informe de 49 Pacientes

Uploaded by

Edgar Geovanny Cardenas FigueroaCopyright:

Available Formats

original article

Management of traumatic brachial artery

injuries: A report on 49 patients

Hasan Ekim,a Mustafa Tuncerb

From the aDepartments of Cardiovascular Surgery and bCardiology, Yüzüncü Yıl University, Van, Turkey

Correspondence: Hasan Ekim, MD · Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Yüzüncü Yıl Üniversitesi Tıp Fakültesi, Kalp ve Damar Cerrahisi

Anabilim Dalı, Van, Turkey · T: +90-0432-210-0811 F: +90-1804-749-9525 · drhasanekim@yahoo.com · Accepted for publication February

2009

Ann Saudi Med 2009; 29(2): 105-109

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVE: The brachial artery is the most frequently injured artery in the upper extremi-

ity due to its vulnerability. The purpose of our study was to review our experience with brachial artery injuries

over a 9-year period, describing the type of injury, surgical procedures, complications, and associated injuries.

PATIENTS AND METHODS: Forty-nine patients with brachial artery injury underwent surgical repair procedures

at our hospital, from the beginning of May 1999 to the end of June 2008. The brachial artery injuries were diagn-

nosed by physical examination and Doppler ultrasonography. Depending on the mode of presentation, patients

were either taken immediately to the operating room for bleeding control and vascular repair or were assessed

by preoperative duplex ultrasonography.

RESULTS: This study group consisted of 43 males and 6 females, ranging in age from 6 to 65 years with a mean

(SD) age of 27.9 (6.7) years. The mechanism of trauma was penetrating in 45 patients and blunt in the remaini-

ing 4 patients. Stab injury was the most frequent form of penetrating trauma (24 of 45). Treatment included

primary arterial repair in 5 cases, end-to-end anastomosis in 28 cases, interposition vein graft in 15 cases, and

interposition-ringed polytetrafluoroethylene graft in 1 case. Associated injuries were common and included

venous injury (14), bone fracture (5), and peripheral nerve injury (11). Fifteen patients developed postoperative

complications. One patient underwent an above-elbow amputation.

CONCLUSIONS: Prompt and appropriate management of the brachial artery injuries, attention to associated

injuries, and a readiness to revise the vascular repair early in the event of failure will maximize patient survival

and upper extremity salvage.

U

pper extremity arterial trauma may significc cidence of associated nerve injuries with brachial artery

cantly impact the outcome of the trauma patc injuries.3 The purpose of our study was to review our

tient, but the literature regarding this topic is experience with brachial artery injuries over a 9-year perc

scarce. Although relatively uncommon, injuries to the riod. The type of injury, surgical procedures, complicatc

arteries of the upper extremity are serious and have tions, and associated injuries were reviewed.

the potential to significantly impact the outcome of the

trauma patient.1 The brachial artery is the most freqc PATIENTS AND METHODS

quently injured artery in the upper extremity. Its injury Forty-nine patients with brachial artery injury underwc

accounts for approximately 28% of all vascular injuries.2 went surgical repair procedures at our hospital from the

The degree of ischemia after brachial artery injuries depc beginning of May 1999 to the end of June 2008. The

pends on whether the injury is proximal or distal to the brachial artery injuries were diagnosed by physical exac

profunda brachii.3 amination and Doppler ultrasonography. The following

All brachial artery injuries can be managed successfc findings were considered to be signs of arterial injury:

fully unless associated with severe concomitant damage brisk bleeding, expanding pulsatile hematoma, pale and

to nerves. The median nerve courses with the brachial cold upper extremities, absent or weak radial and ulnar

artery throughout its length. The radial and ulnar nerves pulses and associated profound neurological deficits. In

parallel portions of the brachial artery. Therefore, as in this series, an average brachial-brachial Doppler index

all upper extremity vascular injuries, there is a high incc less than 0.5 was considered diagnostic for brachial artc

Ann Saudi Med 29(2) March-April 2009 www.saudiannals.net 105

original article brachial artery injuries

tery injury. The initial management of the patients was prevent desiccation and disruption. All patients recc

conducted according to the principles of the advanced ceived intravenous prophylactic antibiotics, which were

trauma and life support (ATLS) guidelines for trauma continued postoperatively for 3 to 5 days, unless prolc

management.4 For patients presenting with hard signs longed use was dictated by the presence of contaminatc

of penetrating vascular injury, prompt surgical intervc tion or infection.

vention without further diagnostic evaluation was used. One month after hospital discharge, patients were

Patients with blunt arterial injury or with penetrating routinely examined in the outpatient department where

injuries with clinical soft signs (cod extremity, color segmental pressures were measured and functional statc

change, nonexpanding hematoma) underwent plain uppc tus of the upper extremity assessed. Thereafter, they

per extremity radiography and Doppler ultrasonograpc were followed at 3-month periods.

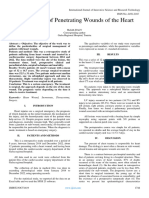

phy (Figure 1). Statistical analysis was performed using the paired

The indications for fasciotomy were clinically evident samples t test to determine whether there was any statc

or impending compartment syndrome, massive swelling tistically significant difference between preoperative

in the upper limb, ischemia lasting more than 6 hours and postoperative Doppler pressure indices. A P value

and any motor or sensory deficits. In all patients with of less than .05 was taken to indicate significance.

associated bone fracture, vascular repair always precc

ceded orthopedic reconstruction. Endoluminal shunts RESULTS

were not required in any of the patients. Successful This study group consisted of 43 males and 6 females,

repair was assessed by the return of radial and ulnar ranging in age from 6 to 65 years with a mean (SD)

pulses at the end of the operation. age of 27.9 (6.7) years. The right upper limb was the

Patients with more severe soft tissue and muscle more frequently affected side as it was involved in 28

injuries were treated with thorough debridement of all patients and the left side in 21 patients. The mechanism

grossly nonviable tissue, with removal of foreign bodic of trauma was penetrating in 45 patients and blunt in

ies and copious irrigation with isotonic saline solution, the remaining 4 patients (from road traffic accidents).

and then injured vessels were exposed. Heparin was admc Stab injury was the most frequent form of penetrating

ministered intravenously for systemic anticoagulation trauma (24 of 45). Other forms of penetrating trauma

before the vessels were clamped proximally and distally in a descending order of frequency were window glass

with nontraumatic vascular clamps. Fogarty catheters injuries in 11 patients, gunshot injuries in 9 patients,

were used for thrombectomy of the distal and proximc and industrial accident in 1 patient. Thirty-four patients

mal arterial segments. All patients received intravenous presented with hemorrhage, 28 with ischemia, 8 with

heparin for a period of 5-7 days postoperatively and hematoma and 1 with a pseudoaneurysm (Table 1).

were discharged home on oral aspirin 100 mg/day for a In 42 patients the diagnosis of arterial injury was

period of 3 months. based on clinical and hand-held Doppler examination.

Exposure of the brachial artery in the arm was alwc Preoperative duplex scan was used in only 7 patients.

ways approached with a median incision in the line of Physical examination and Doppler ultrasonography revc

the sulcus separating the biceps muscle from the triceps vealed the absence of arterial pulses in 43 patients and

muscle. The median nerve was always identified and weak arterial pulses in 6. For brachial artery injuries

separated from the brachial artery. Exposure of the artc the average brachial-brachial Doppler pressure index

tery at the elbow was performed with a skin crease incc was 0.434 (0.046), (range, 0.23 to 0.48) preoperatively,

cision made at the elbow, with longitudinal extensions and 0.894 (0.031) (range, 0.83 to 0.93) postoperatively

along the line of the brachial artery medially and down (P<.05). Treatment included primary arterial repair in 5

the brachioradialis laterally. Primary arterial repair or cases, end-to-end anastomosis in 28 cases, interposition

end-to-end anastomosis was preferred whenever possc vein graft in 15 cases and interposition ringed PTFE

sible; otherwise, the interposition saphenous vein graft graft in 1 case. There were 14 patients with associated

was used (Figure 2). brachial vein injury, of which 4 cases had primary repair,

All associated brachial venous injuries except one 8 had end-to-end anastomosis and 1 had saphenous

were repaired, in an attempt to prevent postoperative vein graft interposition. One severely injured brachial

venous hypertension and to minimize development of vein was compulsory ligated. Five of the 49 patients had

compartment syndrome. Associated nerve injuries were injuries to bony structures. Fractures occurred most freqc

repaired whenever possible. Repaired vessels, especially quently among patients with blunt trauma (3 patients);

at the anastomotic suture lines and graft location, were fracture was also detected in 2 patients with gunshot

compulsorily covered with muscles and soft tissue to wound. All fractures were treated with external fixation.

106 Ann Saudi Med 29(2) March-April 2009 www.kfshrc.edu.sa/annals

brachial artery injuries original article

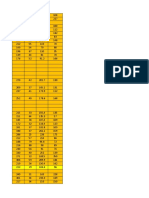

Eight patients had tendinous injuries that were repaired Table 1. Signs, symptoms, and associated injuries among 49

perioperatively by orthopedic surgeons. Additionally, patients with brachial artery injury.

fasciotomy was performed in 6 patients. Presentation No. of patients

Eleven of 49 patients had peripheral nerve injury:

2 had injuries to the median and ulnar nerves, 6 had Pulse deficit 43

injuries to the median nerve alone and 3 had injuries Pulse insufficiency 6

to the ulnar nerve alone. Eight of the 11 nerve injury

Hemorrhage 34

cases were primarily repaired perioperatively by neurosc

surgeons. Postoperatively, all patients with nerve injury Hypotension 20

underwent electromyelography for evaluation of nerve

Peripheral nerve injury 11

deficit. During the follow-up period, functional recovec

ery was achieved in 6 of these patients. In the remaining Venous injury 14

patients, functional disability was evident throughout Tendinous injury 8

follow-up period. They were followed up neurosurgery

and rehabilitation clinics. Hematoma 8

Fifteen patients developed postoperative complicatc Bone fracture 5

tions consisting of wound infection (2 patients), permanc

nent nerve damage (4 patients), ischemic symptoms due Pseudoaneurysm 1

to graft thrombosis (4 patients) and thrombosis of the Ischemia 28

venous repair (5 patients). Amputation was required in

one patient who was involved in a traffic accident and

suffered from a proximal brachial artery laceration with DISCUSSION

injuries to the brachial vein, and the median and ulnar Penetrating trauma is generally considered to be the

nerves above the elbow in association with a fracture most common cause of a vascular injury in the upper

of the humerus. He was operated on 10 hours after injc extremity.5 In addition to the usual types of blunt and

jury. Arterial flow was reestablished successfully with a penetrating injuries, supracondylar fractures or dislocatc

saphenous vein bypass graft and the brachial vein was tion of the humerus may injure the brachial artery.3

ligated, but subsequent above-elbow amputation was The role of angiography in patients with brachial artc

required due the severity of concomitant nerve and tery injury appears to be controversial.9 Upper extremic

bony injuries with a nonfunctional right upper limb and ity arterial injury often can be managed without arterioc

infection. Two patients with blunt trauma experienced ography, particularly in cases with penetrating trauma6

wound infections, but these infections were resolved as seen in this series. Bynoe et al7 has reported 99% sensc

within 15 days by antibiotic therapy. Four patients expc sitivity and 98% accuracy of duplex ultrasonography.

perienced early postoperative graft thrombosis. In these Furthermore, duplex ultrasonography has no interventc

patients, thrombectomy was performed. It was successfc tional risks and is more cost-effective for screening such

ful in three patients. Although thrombectomy was unsc injuries than angiography. Doppler ultrasonography was

successful in the remaining one patient with prosthetic found to be more sensitive than angiography in an expc

graft interposition, amputation of the limb was not reqc perimental trial, thereby supporting its use in the trauma

quired due to adequate collateral circulation. setting.8 Doppler ultrasonography of the upper extremic

Postoperatively, all patients who had brachial vein ity has been shown to be as specific and sensitive as arterc

injury experienced various degrees of edema in the uppc riography in detecting brachial artery injuries.9 If uncertc

per extremity. This edema decreased with elevation in tainty remains regarding vascular injuries after physical

all patients during the follow-up period (approximately examination and Doppler ultrasonography, angiography

15 to 45 days). Postoperative venous Doppler studies may be performed to confirm vascular injury.9

showed thrombosed repair in five cases without any The mainstay of diagnosis of brachial artery injury

complication. No patients expired and 48 patients were in our study was based on clinical assessment and hand-

discharged home with good functional vascular status held Doppler examination. Doppler ultrasonography

and limitations based on the degree of associated nerve was carried out in stable patients with associated soft

injury. signs of injury, to make a conclusive decision. We believe

The average follow-up period was 20 months (range that angiography remains an effective method for diagnc

3-32 months); follow-up visits were usually necessary nosing the vascular lesions, but it is also a time-consumic

for neurological examination. ing procedure, especially in traumatic vascular injuries

Ann Saudi Med 29(2) March-April 2009 www.saudiannals.net 107

original article brachial artery injuries

must be used during endovascular surgery.

UPPER EXTREMITY INJURIES

Normally the average brachial-brachial Doppler

Soft signs of arterial injuries

pressure index between the 2 upper extremities is appc

Hard signs of arterial injuries

proximately 0.95; it is rarely less than 0.85.11 In our serc

rious, preoperative values were significantly lower than

Prompt surgery Doppler ultrasonography normal, but postoperative values were similar to normc

mal. Duplex ultrasonography is fairly reliable, except

Negative signs Positive signs

with minor injuries, depending on the experience of the

sonographers.2 However, in addition to assessing the

Angiography Observation Operation Angiography

upper extremity for pulse pressures by physical examinc

nation and continuous-wave Doppler, neuromuscular

Positive Negative Endovascular function, soft tissue involvement, and skeletal integrity

surgery

should be evaluated.1

Operation Endovascular Observation The timing of vascular repair in relation to fracture

surgery

management has long been a source of controversy.

Because prevention of prolonged tissue ischemia is the

Figure 1. Diagnostic and therapeutic algorithm for upper extremity arterial injuries (soft objective, the standard recommendation is for vascular

signs include cool extremity, color change and nonexpanding hematoma). repair to precede fracture management.12 In contrast,

Hunt et al13 suggested that arterial revascularization

should be followed by skeletal stabilization and nerve

and tendon repair. In the rare instance when external

fixation is immediately required to stabilize the limb

following massive musculoskeletal trauma, temporary

selective use of shunts to restore circulation may be used

to allow rapid fixator placement, with later vascular and

orthopedic repair.1 Unstable fractures jeopardize arterial

repairs more in the upper extremities than in the lower

extremities because of less adjacent muscle.14 Therefore,

we have routinely controlled the repaired vessels after

bone fixation for patency.

Surgical repair of brachial artery injuries can be accc

complished by a variety of techniques, including lateral

repair, resection with end-to-end anastomosis, or interpc

position grafting, usually with a saphenous vein.3 End-

to-end anastomosis is preferable if it can be performed

without tension or damage to major collateral vessels.

Otherwise, the saphenous vein interposition graft is the

next best choice, because it has better patency rates and

better resistance to infection compared with synthetic

grafts.15 However, we had to use a ringed polytetrafc

fluoroethylene (PTFE) graft in one patient with inadec

Figure 2. Reconstruction of crushed brachial artery with

saphenous vein interposition graft.

equate saphenous vein. Endovascular techniques have

increasingly been used in the management of penetratic

ing injuries and may have some advantages even in blunt

requiring prompt surgery. Additionally, preoperative trauma.16 They are especially ideal for managing blunt

angiography did not offer any benefits in patients with axillary artery injuries that are anatomically difficult to

obvious arterial injury. Angiography may be useful, espc repair.1

pecially in patients with multiple sites of potential vasculc It is important to limit the period of ischemia, and

lar injury.10 We have used angiography in patients with so minimize the degree of ischemia-reperfusion injury

stable axillary artery injury associated with chest trauma and the systemic consequences after the arterial repair.

causing subcutaneous emphysema, which prevented ultc The extent of ischemia-reperfusion injury is directly

trasonographic examination. Additionally, angiography proportional to the severity and duration of striated

108 Ann Saudi Med 29(2) March-April 2009 www.kfshrc.edu.sa/annals

brachial artery injuries original article

muscle ischemia. Beyond a golden period of 6 to 8 hours the upper limb is not clear. Injuries of the brachial or

of ischemia, ischemia-reperfusion injury will endanger arm veins can be treated by ligation, as edema is rare.

the viability of the limb and sometimes even the patient’s However, in the case of a severe soft-tissue injury where

life.2 In this series, while 9 patients experienced a duratc maximal venous return is necessary, venous repair is

tion of ischemia longer than this period, there was only probably warranted.5 We would add that brachial venc

one amputation. The infrequent need for amputation nous continuity, when possible, is maintained.

was probably related to the rich collateral circulation in In conclusion, the elbow, like the shoulder, is known

the upper limb of most patients.2,17 Therefore, we suggc to have extensive collateral circulation that may mask

gest that all patients without obvious necrotic changes the signs of acute arterial injury,22 but whether this circc

should be operated on irrespective of time interval betc culation is adequate is debatable.23 Therefore, all bracc

tween the beginning of trauma and arrival to the operatic chial artery injuries should be repaired. Careful clinical

ing room, as was done in this series. examination, Doppler ultrasonography and pressure

Neurological injury continues to destroy the functc measurements are as important as angiography in the

tion of the upper extremity even after a successful arterc diagnosis of vascular injuries.9 Also, the superficial locc

rial repair.9 The rate of functional disability ranges from cation of brachial artery makes the diagnosis relatively

27% to 44% when injury to the upper extremity includes simple. Therefore, brachial artery injuries may be diac

nerve injuries.18 Nichols and Lillehei19 recommend primc agnosed without angiography. We believe that angiogrc

mary nerve repair for penetrating trauma (lacerations raphy should be performed when the vascular injuries

and stab wounds), while with gunshot wounds, because would be impossible to diagnose with other diagnostic

of the degree of contusion, acute nerve repair is rarely indc modalities or when endovascular procedures are reqc

dicated.20 Additionally, major venous injuries, fractures quired. Prompt and appropriate management of the

and widespread tissue destruction may also influence brachial artery injuries, attention to associated injuries

the long term function of the extremity.21 and a readiness to revise the vascular repair early in the

Venous injuries generally remain unrecognized until event of failure will maximize patient survival and upper

surgical exposure. The indication for venous repair in extremity salvage.

References

1. Franz RW, Goodwin RB, Hartman JF, et al. Mana- agnosis of arterial injury: an experimental study. J endovascular techniques. J Trauma. 2005;59:1224-

agement of upper extremity arterial injuries at an Trauma. 1992;33:627-635. 1227.

urban level 1 trauma center. Ann Vasc Surg. Forthc- 9. Ergüne_ K, Yıllık L, Özsöyler I, et al. Traumatic brac- 17. McCroskey BL, Moore EE, Pearce WH, et al.

coming 2008. chial artery injuries. Tex Heart Inst J. 2006;33:31-34. Traumatic injuries of the brachial artery. Am J Surg.

2. Zellweger R, Hess F, Nicol A, et al. An analysis of 10. Hunt CA, Kingsley JR. Vascular injuries of the 1988;156:553-555.

124 surgically managed brachial artery injuries. Am upper extremity. South Med J. 2000;93:466-468. 18. Hardin WD Jr, O’Connell RC, Adinolfi MF, et al.

J Surg. 2003;188:240-245. 11. Shalabi R, Amri YA, Khoujah E. Vascular injuries Traumatic arterial injuries of the upper extremity:

3. McCready RA. Upper-extremity vascular injuries. of the upper extremity. J Vasc Brasil. 2006;5:271- determinants of disability. Am J Surg. 1985;150:266-

Surg Clin North Am. 1988;68:725-740. 276. 270.

4. The Advanced Trauma Life Support for Physic- 12. McHenry TP, Holcomb JB, Aoki N, et al. Fract- 19. Nichols JS, Lillehei KO. Nerve injury associated

cians. Instructor Manual. Chicago: American tures with major vascular injuries form gunshot with acute vascular trauma. Surg Clin North Am.

College of Surgeons. 5th ed. 1992. wounds: implications of surgical sequence. J 1988;68:837-852.

5. Orcutt MB, Levine BA, Gaskill HV, et al. Civilian Trauma. 2002;53:717-721. 20. Cikrit DF, Dalsing MC, Bryant BJ, et al. An exper-

vascular trauma of the upper extremity. J Trauma. 13. Hunt CA, Kingsley JR. Vascular injuries of the rience with upper-extremity vascular trauma. Am J

1986;26:63-67. upper extremity. South Med J. 2000;93:466-468. Surg. 1990;160:229-233.

6. Pillai L, Luchette FA, Romanso KS, et al. Upper 14. Borman KR, Snyder WH, Weigelt JA. Civilian 21. Rich NM, Spencer FC. Vascular trauma. Philad-

extremity arterial injury. Am Surgeon. 1997;63:224- arterial trauma of the upper extremity. AM J Surg. delphia: WB Saunders; 1978. 125-156p.

227. 1984;148:796-799. 22. Sparks SR, DeLaRosa J, Bergan JJ, et al. Arter-

7. Bynoe R, Miles W, Bell R, et al. Non-invasive dia- 15. Yavuz S, Tiryakio_lu O, Celkan A, et al. Emergenc- rial injury in uncomplicated upper extremity disloc-

agnosis of vascular trauma by duplex ultrasonograp- cy surgical procedures in the peripheral vascular cations. Ann Vasc Surg. 2000;14:110-113.

phy. J Vasc Surg. 1991;14:346-352. injuries. Turk J Vasc Surg. 2000;1:15-20. 23. Sri-Ram K, Ranawat V. Significant brachial art-

8. Panetta TF, Hunt JP, Beuchter KJ, et al. Duplex 16. Lönn L, Delle M, Karlström L, et al. Should blunt tery injury in a well perfused limb following closed

ultrasonography versus arteriography in the dia- arterial trauma to the extremities be treated with elbow dislocation. Injury Extra. 2005;36:239-241.

Ann Saudi Med 29(2) March-April 2009 www.saudiannals.net 109

You might also like

- ALU 201 Practice QuestionsDocument15 pagesALU 201 Practice QuestionsPeter100% (1)

- ACLS Pocket CardDocument6 pagesACLS Pocket Cardno_spam_mang83% (6)

- Case Presentation On MIDocument40 pagesCase Presentation On MIKaku Manisha85% (13)

- Carotid Endarterectomy: Experience in 8743 Cases.Document13 pagesCarotid Endarterectomy: Experience in 8743 Cases.Alexandre Campos Moraes AmatoNo ratings yet

- Frando Final Term Learning Activity Sheet 1Document27 pagesFrando Final Term Learning Activity Sheet 1Ranz Kenneth G. FrandoNo ratings yet

- 2021 AHA ASA Guideline For The Prevention of Stroke in Patients With Stroke and TIA Clinical UpdateDocument43 pages2021 AHA ASA Guideline For The Prevention of Stroke in Patients With Stroke and TIA Clinical Updatejulioel1nico20100% (1)

- 2004 Complications in Vascular Surgery PDFDocument743 pages2004 Complications in Vascular Surgery PDFmamicanic100% (1)

- Vascular Journal Reading - Rendi KurniawanDocument6 pagesVascular Journal Reading - Rendi KurniawanChristopher TorresNo ratings yet

- Usefulness of Stent Implantation For Treatment ofDocument19 pagesUsefulness of Stent Implantation For Treatment ofAngel YapNo ratings yet

- De Neuville 2000Document5 pagesDe Neuville 2000Anonymous WPiPld6npNo ratings yet

- Principles in The Management of Arterial Injuries Associated With Fracture DislocationsDocument5 pagesPrinciples in The Management of Arterial Injuries Associated With Fracture DislocationsJohannes CordeNo ratings yet

- JurnalDocument7 pagesJurnalLaginta Revilosa ZilmiNo ratings yet

- Journal Reading DigestivDocument35 pagesJournal Reading DigestivFadliArifNo ratings yet

- Eriksen Et Al-2002-Clinical Cardiology PDFDocument5 pagesEriksen Et Al-2002-Clinical Cardiology PDFmedskyqqNo ratings yet

- Vascular InjuriesDocument7 pagesVascular Injurieskrupa kelkarNo ratings yet

- Carotid StentDocument9 pagesCarotid StentCut FadmalaNo ratings yet

- Duplex Guided Balloon Angioplasty and Subintimal DDocument8 pagesDuplex Guided Balloon Angioplasty and Subintimal DJose PiulatsNo ratings yet

- Percutaneous Transluminal Angioplasty and Stenting As First-Choice Treatment in Patients With Chronic Mesenteric IschemiaDocument6 pagesPercutaneous Transluminal Angioplasty and Stenting As First-Choice Treatment in Patients With Chronic Mesenteric IschemiaCotaga IgorNo ratings yet

- Injury: Shinsuke Tanizaki, Shigenobu Maeda, Hideyuki Matano, Makoto Sera, Hideya Nagai, Hiroshi IshidaDocument4 pagesInjury: Shinsuke Tanizaki, Shigenobu Maeda, Hideyuki Matano, Makoto Sera, Hideya Nagai, Hiroshi IshidaWinda Ayu SholikhahNo ratings yet

- Accepted Manuscript: 10.1016/j.cjtee.2015.12.015Document8 pagesAccepted Manuscript: 10.1016/j.cjtee.2015.12.015Desak PramestiNo ratings yet

- Word 1663843244389Document11 pagesWord 1663843244389Atik PurwandariNo ratings yet

- Complications of Temporomandibular Joint Arthroscopy: A Retrospective Analytic Study of 670 Arthroscopic ProceduresDocument5 pagesComplications of Temporomandibular Joint Arthroscopy: A Retrospective Analytic Study of 670 Arthroscopic ProceduresAbhishek SinghNo ratings yet

- Vascular Trauma NOR NewDocument24 pagesVascular Trauma NOR NewNorman HadiNo ratings yet

- Korean QX Total Pulm Veins 2010Document5 pagesKorean QX Total Pulm Veins 2010Dr. LicónNo ratings yet

- Predictor Mortality EVARDocument7 pagesPredictor Mortality EVARAnneSaputraNo ratings yet

- Duplex Guided Balloon Angioplasty and Stenting ForDocument6 pagesDuplex Guided Balloon Angioplasty and Stenting ForJose PiulatsNo ratings yet

- 10 1016@j Jse 2019 10 013Document12 pages10 1016@j Jse 2019 10 013Gustavo BECERRA PERDOMONo ratings yet

- Ultrasound Supraclavicular Plexus Block Enhances Arteriovenous Fistula Blood Flow in ESRDDocument14 pagesUltrasound Supraclavicular Plexus Block Enhances Arteriovenous Fistula Blood Flow in ESRDaymankahlaNo ratings yet

- Makalah Journal Reading FazaDocument11 pagesMakalah Journal Reading FazaFaza Yuspa LioshaNo ratings yet

- Artigo 3Document7 pagesArtigo 3Lucas SantosNo ratings yet

- (10920684 - Neurosurgical Focus) Falcotentorial Meningiomas - Clinical, Neuroimaging, and Surgical Features in Six PatientsDocument7 pages(10920684 - Neurosurgical Focus) Falcotentorial Meningiomas - Clinical, Neuroimaging, and Surgical Features in Six PatientsPutri PrameswariNo ratings yet

- NASCETDocument9 pagesNASCETektosNo ratings yet

- Short-And Long-Term Outcomes of Acute Upper Extremity Arterial ThromboembolismDocument4 pagesShort-And Long-Term Outcomes of Acute Upper Extremity Arterial ThromboembolismWilhelm HeinleinNo ratings yet

- Risk Factors of Venous Thromboembolism in Indian Patients With Pelvic-Acetabular TraumaDocument8 pagesRisk Factors of Venous Thromboembolism in Indian Patients With Pelvic-Acetabular TraumaFadliArifNo ratings yet

- Posttrx Empyema PDFDocument6 pagesPosttrx Empyema PDFAndyGcNo ratings yet

- Progression of Native Coronary Artery Disease at 10 Years: Ts From A Randomized Study of Medical Versus Surgical Therapy For AnginaDocument5 pagesProgression of Native Coronary Artery Disease at 10 Years: Ts From A Randomized Study of Medical Versus Surgical Therapy For AnginaprasanbhandariNo ratings yet

- 405 2013 Article 2598Document5 pages405 2013 Article 2598M Shiddiq GhiffariNo ratings yet

- CT - Cardiac Tamponade 2013Document5 pagesCT - Cardiac Tamponade 2013floNo ratings yet

- Blunt Traumatic Aortic Injury: Initial Experience With Endovascular RepairDocument6 pagesBlunt Traumatic Aortic Injury: Initial Experience With Endovascular RepairYahya AlmalkiNo ratings yet

- Estudio de Endarterectomía CarotídeaDocument9 pagesEstudio de Endarterectomía CarotídeaErnest Pardo RubioNo ratings yet

- Anestesi Luar BiasaDocument51 pagesAnestesi Luar BiasarozanfikriNo ratings yet

- Antikoagulan JurnalDocument5 pagesAntikoagulan JurnalansyemomoleNo ratings yet

- 2006 - Longterm Outcome After Surgery For Pulmonary Stenosis (A Longitudinal Study of 22-33 Years)Document7 pages2006 - Longterm Outcome After Surgery For Pulmonary Stenosis (A Longitudinal Study of 22-33 Years)Tammy Utami DewiNo ratings yet

- Asensio, JA, (2020) - Tratamiento Quirúrgico de Las Lesiones de La Arteria Braquial y Predictores de Resultado.Document12 pagesAsensio, JA, (2020) - Tratamiento Quirúrgico de Las Lesiones de La Arteria Braquial y Predictores de Resultado.Edgar Geovanny Cardenas FigueroaNo ratings yet

- Anaesthesia 1Document9 pagesAnaesthesia 1Sreekanth JangamNo ratings yet

- Management of Pseudoaneurysms in IV Drug Users: Ori Gi Nal Arti CL eDocument4 pagesManagement of Pseudoaneurysms in IV Drug Users: Ori Gi Nal Arti CL eMayur DadhaniyaNo ratings yet

- End Arte Rec To MyDocument7 pagesEnd Arte Rec To MyLuming LiNo ratings yet

- Medip, IJORO-2425 CSDocument6 pagesMedip, IJORO-2425 CSpaula sullaNo ratings yet

- Articol Medico Legal Aspects AVMDocument9 pagesArticol Medico Legal Aspects AVMVoicu AndreiNo ratings yet

- A 40 YearsDocument9 pagesA 40 YearsDra Mariana Huerta CampaNo ratings yet

- Zanaty 2014Document7 pagesZanaty 2014silvinhojr1212No ratings yet

- 08 Subasi NecmiogluDocument7 pages08 Subasi Necmiogludoos1No ratings yet

- ATLSDocument5 pagesATLSoskrxbNo ratings yet

- Case Report: Transmediastinal and Transcardiac Gunshot Wound With Hemodynamic StabilityDocument4 pagesCase Report: Transmediastinal and Transcardiac Gunshot Wound With Hemodynamic StabilityAmriansyah PranowoNo ratings yet

- Schmidt 2010Document8 pagesSchmidt 2010Billy Aditya PratamaNo ratings yet

- Guinot2017 PDFDocument9 pagesGuinot2017 PDFFIA SlotNo ratings yet

- Management of Penetrating Wounds of The HeartDocument2 pagesManagement of Penetrating Wounds of The HeartInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Trauma de CuelloDocument8 pagesTrauma de Cuellolilym.alvarez.lNo ratings yet

- Spontaneous Vertebral Artery Dissection: Report of 16 Cases: Original ArticleDocument7 pagesSpontaneous Vertebral Artery Dissection: Report of 16 Cases: Original ArticleAyu Yoniko CimplukNo ratings yet

- 2019 Unusual Cavitary Lesions of The Lung Analysis ofDocument6 pages2019 Unusual Cavitary Lesions of The Lung Analysis ofLexotanyl LexiNo ratings yet

- Outcome of Septal Dermoplasty in Patients With Hereditary Hemorrhagic TelangiectasiaDocument5 pagesOutcome of Septal Dermoplasty in Patients With Hereditary Hemorrhagic TelangiectasiaalecsaNo ratings yet

- Primary Operative Renal Salvage of Grade-4 Blunt Renal Injury: A Case ReportDocument4 pagesPrimary Operative Renal Salvage of Grade-4 Blunt Renal Injury: A Case ReportArsyad FadliNo ratings yet

- Cell Therapy in Patients With Left Ventricular Dysfunction Due To Myocardial InfarctionDocument10 pagesCell Therapy in Patients With Left Ventricular Dysfunction Due To Myocardial InfarctionMrityunjay PathakNo ratings yet

- Percutaneous Aortic Valve Implantation: The Anesthesiologist PerspectiveDocument11 pagesPercutaneous Aortic Valve Implantation: The Anesthesiologist Perspectiveserena7205No ratings yet

- Atlas of Coronary Intravascular Optical Coherence TomographyFrom EverandAtlas of Coronary Intravascular Optical Coherence TomographyNo ratings yet

- Peripheral Arterial Disease BMJ SUMARYDocument68 pagesPeripheral Arterial Disease BMJ SUMARYEdgar Geovanny Cardenas FigueroaNo ratings yet

- Diabetic Foot ComplicationsDocument66 pagesDiabetic Foot ComplicationsEdgar Geovanny Cardenas FigueroaNo ratings yet

- Asensio, JA, (2020) - Tratamiento Quirúrgico de Las Lesiones de La Arteria Braquial y Predictores de Resultado.Document12 pagesAsensio, JA, (2020) - Tratamiento Quirúrgico de Las Lesiones de La Arteria Braquial y Predictores de Resultado.Edgar Geovanny Cardenas FigueroaNo ratings yet

- Guerrero, A., (2002) - ANTICOAGULACION Pérdida de Una Extremidad Tras Un Traumatismo Arterial de La Extremidad InferiorDocument5 pagesGuerrero, A., (2002) - ANTICOAGULACION Pérdida de Una Extremidad Tras Un Traumatismo Arterial de La Extremidad InferiorEdgar Geovanny Cardenas FigueroaNo ratings yet

- 19 Cardiac DisordersDocument51 pages19 Cardiac DisordersChessie Garcia100% (1)

- Acute Myocardial InfarctionDocument42 pagesAcute Myocardial InfarctionAzra BalochNo ratings yet

- Cureus 0013 00000017832Document8 pagesCureus 0013 00000017832raulNo ratings yet

- IMA Nurse KKV SaifurDocument69 pagesIMA Nurse KKV Saifureva munartyNo ratings yet

- The Role of Imaging in Acute Ischemic Stroke: E T, M.D., Q H, M.D., P .D., J B. F, M.D., M W, M.D., M.a.SDocument17 pagesThe Role of Imaging in Acute Ischemic Stroke: E T, M.D., Q H, M.D., P .D., J B. F, M.D., M W, M.D., M.a.Schrist_cruzerNo ratings yet

- PATH 1 ALL Lectures Final1Document2,054 pagesPATH 1 ALL Lectures Final1Andleeb Imran100% (1)

- 2013 ESC Stabilna Koronarna BolestDocument66 pages2013 ESC Stabilna Koronarna BolestМилан ЛабудовићNo ratings yet

- Rivaroxaban in Peripheral Artery Disease After RevascularizationDocument11 pagesRivaroxaban in Peripheral Artery Disease After RevascularizationktorooNo ratings yet

- CV - Imaging of Heart Disease in Women - Review and Case PresentationDocument30 pagesCV - Imaging of Heart Disease in Women - Review and Case PresentationAndi Wetenri PadaulengNo ratings yet

- Pathophysiology and Clinical Manifestation of StrokeDocument42 pagesPathophysiology and Clinical Manifestation of Strokedrg Riki Indra KusumaNo ratings yet

- AV UWorld EOs (Rough Draft) - Data - Repeat LandscapeDocument139 pagesAV UWorld EOs (Rough Draft) - Data - Repeat LandscapeJonathan AiresNo ratings yet

- ArterosclerozaDocument35 pagesArterosclerozaSevda MemetNo ratings yet

- Pathology in Clinical Practice 50 Case Studies - 2009Document224 pagesPathology in Clinical Practice 50 Case Studies - 2009Omar SarvelNo ratings yet

- HemiplegiaDocument31 pagesHemiplegiaislam1111No ratings yet

- Literature Research and CodesDocument63 pagesLiterature Research and CodesMiral Sandipbhai MehtaNo ratings yet

- Bipolar Disorders - 2023 - Ponzer - Lithium and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease Dementia and Venous ThromboembolismDocument11 pagesBipolar Disorders - 2023 - Ponzer - Lithium and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease Dementia and Venous ThromboembolismKonstantinos RantisNo ratings yet

- Diabetic Foot Classifications: Review of Literature: Amit Kumar C Jain, Sunil JoshiDocument7 pagesDiabetic Foot Classifications: Review of Literature: Amit Kumar C Jain, Sunil JoshiPutriPasaribuNo ratings yet

- 2016 TechnologyWatch Vol1Document27 pages2016 TechnologyWatch Vol1amit545No ratings yet

- Stroke EssentialsDocument44 pagesStroke Essentialsapi-452244667No ratings yet

- Laporan Kasus StemiDocument41 pagesLaporan Kasus StemiNur Aisyah Soedarmin IieychaNo ratings yet

- ACS FianlDocument72 pagesACS FianlmawardikaNo ratings yet

- Molecules 28 05624Document30 pagesMolecules 28 05624Sayed Newaj ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- Myocardial Ischaemia-ReperfusionDocument17 pagesMyocardial Ischaemia-ReperfusionMateo Daniel Gutierrez CastañedaNo ratings yet

- Paper 1 MCQDocument8 pagesPaper 1 MCQmarwaNo ratings yet

- Acute Monocular Vision LossDocument9 pagesAcute Monocular Vision LossRoberto López MataNo ratings yet