Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Doesn't It Look Like An Abstract Painting That You Might Find in A Gallery Somewhere, With Dozens of Connoisseurs Surrounding It, Analyzing The Meaning Behind The Artist's Vision?

Doesn't It Look Like An Abstract Painting That You Might Find in A Gallery Somewhere, With Dozens of Connoisseurs Surrounding It, Analyzing The Meaning Behind The Artist's Vision?

Uploaded by

Nouhaila Camili0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

15 views5 pagesEarly computer art in the 1960s-1970s was created primarily by engineers and faced skepticism from the traditional art world. However, communities formed to support digital art. A pivotal moment was 1984 when the Macintosh computer and software like MacPaint made digital art accessible to a wider audience. Iconic art software in the late 80s and early 90s further lowered barriers, and dedicated digital art museums and online platforms emerged in the late 90s to promote and showcase computer-generated artwork.

Original Description:

Original Title

eg

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentEarly computer art in the 1960s-1970s was created primarily by engineers and faced skepticism from the traditional art world. However, communities formed to support digital art. A pivotal moment was 1984 when the Macintosh computer and software like MacPaint made digital art accessible to a wider audience. Iconic art software in the late 80s and early 90s further lowered barriers, and dedicated digital art museums and online platforms emerged in the late 90s to promote and showcase computer-generated artwork.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

15 views5 pagesDoesn't It Look Like An Abstract Painting That You Might Find in A Gallery Somewhere, With Dozens of Connoisseurs Surrounding It, Analyzing The Meaning Behind The Artist's Vision?

Doesn't It Look Like An Abstract Painting That You Might Find in A Gallery Somewhere, With Dozens of Connoisseurs Surrounding It, Analyzing The Meaning Behind The Artist's Vision?

Uploaded by

Nouhaila CamiliEarly computer art in the 1960s-1970s was created primarily by engineers and faced skepticism from the traditional art world. However, communities formed to support digital art. A pivotal moment was 1984 when the Macintosh computer and software like MacPaint made digital art accessible to a wider audience. Iconic art software in the late 80s and early 90s further lowered barriers, and dedicated digital art museums and online platforms emerged in the late 90s to promote and showcase computer-generated artwork.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 5

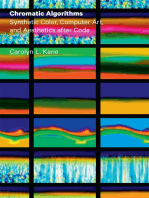

FIGURE 4.

2 First artwork from the Henry Drawing Machine

Doesn’t it look like an abstract painting that you might find in a

gallery somewhere, with dozens of connoisseurs surrounding it,

analyzing the meaning behind the artist’s vision?

Unfortunately, this wasn’t the case. Computer art, as it was referred

to back in those times, was not particularly respected by the art

world. Perhaps this was because computers were lifeless machines

that crunched numbers all day, or they resembled the machines that

churned out Coca‐Colas on a factory line. Or, perhaps it was because

their creators were nerds who obsessed over the minutiae of

something no one understood, not eccentric and lively artists with

whom you’d love to have a conversation.

Regardless of the reasons, computer art remained the distant step‐

cousin of the art world for decades. “It’s not real art” was the

popular and entirely ridiculous response to this style of creation.

Despite the hate, believers in computer art chugged along and

formed their own communities of support.

In 1967, the nonprofit Experiments in Art and Technology was

formed following a series of performances the previous year called

“9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering,” where 10 contemporary

artists joined forces with 30 engineers and scientists from Bell Labs

to showcase the use of new technologies in art.

In 1968, the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London hosted one

of the most influential early exhibitions of computer art, called

“Cybernetic Serendipity.” Also in 1968, the Computer Arts Society

was founded to promote the use of computers in artwork.

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, much of the digital art created was

dependent on the use of mathematics, using early algorithms and

math to generate abstract art. Digital art was almost entirely siloed

to the engineers interested in pushing the limits of technology or

the few artists who had the foresight to test this new form of

creation.

Artistry has always required a technical understanding of the

medium used, along with an understanding of art composition.

Whether the medium is pastel on canvas, graphite on paper, or

chisel against marble, the technical understanding of how the

materials react with the surface wasn’t insurmountable. It just took

practice.

Early digital art was no different in that you had to understand the

medium, which at the time meant understanding how computers

operated. For this reason, many of the early digital artists were

computer programmers.

Then a tectonic shift happened in 1984 that would change not only

“how” computer art was created but more importantly “who” could

create it.

Steve Jobs was on the scene at Apple, and his first major release was

the Macintosh computer, whose main advantage was the graphical

user interface (GUI). GUIs were paramount in that they presented

computing through icons and windows, allowing the average person

to interact with computers. Not to mention, for just $195, Mac users

could purchase MacPaint and have the ability to create their own

digital art. Personal computers gave every artist the ability to create

digital art. As we discussed earlier in this chapter, Commodore

followed up Apple the following year with its Amiga 1000 computer

and the Deluxe Paint software.

In the decade that followed, iconic software developed specifically

for the purposes of creating digital art began popping up: Adobe

Photoshop in 1988 and Corel Painter in 1990, for example. And then

in 1992, Wacom created one of the first tablet computers where

users interacted with the computer through a cordless stylus—a

digital artist’s dream.

Because software made the creation of digital art easier, more

artists began using the tools and forming communities to share

their experiences. Recognizing that digital art was taking off but had

no central place to display, the Austin Museum of Digital Art was

launched in 1997, entirely for the display and promotion of digital

creations. A couple of years later, the Digital Art Museum launched

the first online museum for digital art. (And a little over a decade

Acknowledgments

With much gratitude to Danny from WorldStar Hip‐Hop, Liza

Wiemer, Ryan Cowdrey, Wallon Walusayi, Wendy Souter, Joe

Marcus, Nigel Wyatt, Patrick Shea, Kathleen Mahoney, Coinbase,

MetaMask, C3 Entertainment, Inc., CoinMarketCap, Mike

Winkelmann, Elaine O’Hanrahan, Dapper Labs, shl0ms,

Scrazyone1, and WhatsGoodApps.

Thank you to anyone who has ever conversed with us about NFTs,

collected NFTs alongside us, or consulted with us about their NFTs.

All of those interactions helped make this book a reality.

—Matt Fortnow and QuHarrison Terry

WILEY END USER LICENSE AGREEMENT

Go to www.wiley.com/go/eula to access Wiley’s ebook EULA.

You might also like

- vertical XY plotter drawing robot - ٠٨٣٣٠٨Document78 pagesvertical XY plotter drawing robot - ٠٨٣٣٠٨rufaidaNo ratings yet

- How To Get More & Better From Your Agency'S Informatics Research DivisionDocument49 pagesHow To Get More & Better From Your Agency'S Informatics Research DivisionGolan Levin100% (6)

- New Media Art - Introduction - Mark Tribe - Brown University WikiDocument15 pagesNew Media Art - Introduction - Mark Tribe - Brown University WikiCode021No ratings yet

- 10 Years of Romanian Mathematical Competitions - Radu Gologan PDFDocument7 pages10 Years of Romanian Mathematical Competitions - Radu Gologan PDFDumi NeluNo ratings yet

- Chromatic Algorithms: Synthetic Color, Computer Art, and Aesthetics after CodeFrom EverandChromatic Algorithms: Synthetic Color, Computer Art, and Aesthetics after CodeRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- ARTE Mark Tribe - New Media ArtDocument31 pagesARTE Mark Tribe - New Media ArtMisael DuránNo ratings yet

- Cover FactorDocument5 pagesCover Factorselvapdm50% (2)

- 1 Digital Art Introduction and HistoryDocument60 pages1 Digital Art Introduction and Historyhazee0724No ratings yet

- Lesson 1 Technology-Based ArtDocument10 pagesLesson 1 Technology-Based ArtGerly Rana De Guzman100% (1)

- Digital paintin-WPS OfficeDocument15 pagesDigital paintin-WPS OfficeAce KingNo ratings yet

- Atestat Pastiu IoanaDocument14 pagesAtestat Pastiu IoanaPaștiu Ioana PetronelaNo ratings yet

- Adjunct Professor of Art, MFA Computer Art School of Visual ArtsDocument3 pagesAdjunct Professor of Art, MFA Computer Art School of Visual ArtsFacil SilvaNo ratings yet

- Exhibition Strategies For Digital Art - Examples and ConsiderationsDocument26 pagesExhibition Strategies For Digital Art - Examples and ConsiderationsCaín SVNo ratings yet

- 123 enDocument42 pages123 enRobert AlagjozovskiNo ratings yet

- LISA - The Futility of Media Art in A Contemporary Art WorldDocument35 pagesLISA - The Futility of Media Art in A Contemporary Art WorldMarius WatzNo ratings yet

- DangDocument11 pagesDangTubol101No ratings yet

- Technology Based ArtsDocument54 pagesTechnology Based Artsfrancisjadeluchana13No ratings yet

- Grade 10 - Arts q2Document20 pagesGrade 10 - Arts q2Mary Karen Lachica Catunao100% (5)

- What Is Digital Art?: Arts Theologists and HistoriansDocument8 pagesWhat Is Digital Art?: Arts Theologists and HistoriansYannaNo ratings yet

- Computer ArtDocument20 pagesComputer ArterokuNo ratings yet

- The Rise and Fall of Internet Art Communities, From DeviantArt To TumblrDocument13 pagesThe Rise and Fall of Internet Art Communities, From DeviantArt To TumblrAlejandro G. RuffoniNo ratings yet

- Technology Based Arts: Abalos, Abarido, Bolongon, Celedio, Morales, Ricardo and Beltran X-CepheusDocument14 pagesTechnology Based Arts: Abalos, Abarido, Bolongon, Celedio, Morales, Ricardo and Beltran X-CepheusNorene BolongonNo ratings yet

- Digital Culture & Society (DCS): Vol 8, Issue 2/2022 - Algorithmic ArtFrom EverandDigital Culture & Society (DCS): Vol 8, Issue 2/2022 - Algorithmic ArtMathias FuchsNo ratings yet

- Arte DigitalDocument6 pagesArte DigitalANTHONY ORELLANANo ratings yet

- Technology Based ArtDocument20 pagesTechnology Based ArtchatNo ratings yet

- Digital ArtDocument23 pagesDigital ArtJohn Marcus RioNo ratings yet

- Impact of Technology in ArtDocument9 pagesImpact of Technology in ArtJoyNo ratings yet

- GradeDocument16 pagesGradeOm NamaNo ratings yet

- Media Arts: Grade 7 SpaDocument11 pagesMedia Arts: Grade 7 SpaJUDYLYN MORENONo ratings yet

- Technology-Based ArtDocument9 pagesTechnology-Based ArtJohn Erniest Tabungar AustriaNo ratings yet

- WillThereBe Computer ArtDocument3 pagesWillThereBe Computer ArtNatasha LaracuenteNo ratings yet

- Digital Renaissance: The Next Frontier in Art, Design, and CreativityFrom EverandDigital Renaissance: The Next Frontier in Art, Design, and CreativityRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- SoftwareCatalog 1Document68 pagesSoftwareCatalog 110101010101010101020No ratings yet

- Gr1 Technology Based Sensitivity 20231112 091939 0000Document16 pagesGr1 Technology Based Sensitivity 20231112 091939 0000130043tiburcioNo ratings yet

- Stone Age of The Computer ArtsDocument4 pagesStone Age of The Computer ArtsDarline Loreto CastroNo ratings yet

- Zylinska 2020 AI-ArtDocument181 pagesZylinska 2020 AI-Artbruno_vianna_1100% (1)

- 7ARTS GR 10 LM - Qtr2 (8 Apr 2015) PDFDocument26 pages7ARTS GR 10 LM - Qtr2 (8 Apr 2015) PDFRodRigo Mantua Jr.No ratings yet

- Mapeh Group 2: Art PresentationDocument56 pagesMapeh Group 2: Art PresentationRaffy LlenaNo ratings yet

- 2nd Quarter Lesson 1 Technology Base Art 1Document19 pages2nd Quarter Lesson 1 Technology Base Art 1Janzelle Arman Arellano Servanda100% (1)

- CHM Revolution Discovery DeckDocument15 pagesCHM Revolution Discovery DeckhahaggergNo ratings yet

- EylemEylulAcarsoy WritingsPortfolioDocument49 pagesEylemEylulAcarsoy WritingsPortfolioEylem Eylül AcarsoyNo ratings yet

- Mapeh 10 Arts q2w4s1Document3 pagesMapeh 10 Arts q2w4s1Sharra Joy Valmoria100% (1)

- Quarter II: Technology - Base D ArtDocument35 pagesQuarter II: Technology - Base D ArtGrade EightNo ratings yet

- Manovich - Defining - AI - Arts - Three - Proposals PDFDocument9 pagesManovich - Defining - AI - Arts - Three - Proposals PDFCesarNo ratings yet

- Arts 10 Q2 M1 Technology Based Art 1Document51 pagesArts 10 Q2 M1 Technology Based Art 1aaronscimdtNo ratings yet

- Alan Kay Universal Media MachineDocument53 pagesAlan Kay Universal Media Machinetoso11793No ratings yet

- Module 10 Lesson 10, ArtDocument5 pagesModule 10 Lesson 10, ArtChristian ConsignaNo ratings yet

- 8 March Reading MCQDocument22 pages8 March Reading MCQxf1ix0i7No ratings yet

- Can Computers Create Art?: Aaron HertzmannDocument25 pagesCan Computers Create Art?: Aaron Hertzmanngheorghe garduNo ratings yet

- CHRISTIANE PAUL Renderings of Digital ArtDocument14 pagesCHRISTIANE PAUL Renderings of Digital ArtAna ZarkovicNo ratings yet

- Has Technology Influenced The Way We Make Art 2Document2 pagesHas Technology Influenced The Way We Make Art 2hlacombeNo ratings yet

- A Detailed Lesson Plan in ArtsDocument18 pagesA Detailed Lesson Plan in ArtsSherwin Caliguiran TamayaoNo ratings yet

- Q2 Arts M1Document6 pagesQ2 Arts M1VentiNo ratings yet

- Jonas MAPEHDocument1 pageJonas MAPEHjonas TiglaoNo ratings yet

- 33 Article 2002-Libre PDFDocument6 pages33 Article 2002-Libre PDFMert AslanNo ratings yet

- אמנות פוסטמודרניתDocument290 pagesאמנות פוסטמודרניתlev2468No ratings yet

- Cramer Florian Anti-Media Ephemera On Speculative Arts 2013 PDFDocument264 pagesCramer Florian Anti-Media Ephemera On Speculative Arts 2013 PDFKamen NedevNo ratings yet

- Arduino for Artists: How to Create Stunning Multimedia Art with ElectronicsFrom EverandArduino for Artists: How to Create Stunning Multimedia Art with ElectronicsRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- The Dilemma of Media Art: Cybernetic Serendipity at The ICA LondonDocument22 pagesThe Dilemma of Media Art: Cybernetic Serendipity at The ICA LondonGraciela MCNo ratings yet

- The History of Computer GraphicsDocument13 pagesThe History of Computer GraphicsjonsutzNo ratings yet

- Physics Practical-5Document12 pagesPhysics Practical-5www.jyotirmay1234No ratings yet

- Structural Design Calculation of CCT at BhimavaramDocument61 pagesStructural Design Calculation of CCT at Bhimavaramepe civilNo ratings yet

- Particle Size Distribution Sieve Analysis Lab ReportDocument2 pagesParticle Size Distribution Sieve Analysis Lab ReportSANI SULEIMAN0% (1)

- Full Paper IMPACT OF TEAMWORK ON ORGANIZATIONAL PRODUCTIVITY IN SOME SELECTED BASIC SCHOOLSDocument13 pagesFull Paper IMPACT OF TEAMWORK ON ORGANIZATIONAL PRODUCTIVITY IN SOME SELECTED BASIC SCHOOLSPrasad SirsangiNo ratings yet

- KPC3051 - KPC3052: PhotocouplerDocument4 pagesKPC3051 - KPC3052: PhotocouplerFadi NajjarNo ratings yet

- Sukatan Pelajaran Matematik KBSRDocument13 pagesSukatan Pelajaran Matematik KBSRAhimin KerisimNo ratings yet

- Latitude 3330 12275-1 - AUSTIN13 - CHIEFRIVER - MB - A00 - 0226Document106 pagesLatitude 3330 12275-1 - AUSTIN13 - CHIEFRIVER - MB - A00 - 0226Night FuryNo ratings yet

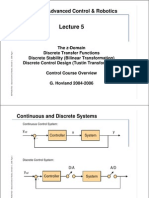

- Adv Control & Robotic Lec 5Document31 pagesAdv Control & Robotic Lec 5key3hseNo ratings yet

- Peter T. Geach - (1956) Good and Evil. Analysis 17 (2) .Document11 pagesPeter T. Geach - (1956) Good and Evil. Analysis 17 (2) .filosophNo ratings yet

- ISD1700 Design Guide - pdf1Document83 pagesISD1700 Design Guide - pdf1leomancaNo ratings yet

- Mus 105 HandoutsDocument91 pagesMus 105 HandoutsPablo Gambaccini100% (1)

- Sony Bx1s Chassis Kv-Ar14m50 SMDocument195 pagesSony Bx1s Chassis Kv-Ar14m50 SMCube7 GeronimoNo ratings yet

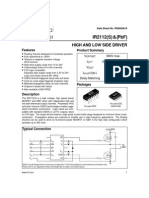

- Ir2112 (S) & (PBF) : High and Low Side DriverDocument17 pagesIr2112 (S) & (PBF) : High and Low Side DriverMugahed DammagNo ratings yet

- Operations Manual For BMR 1000Document18 pagesOperations Manual For BMR 1000johnstn4544No ratings yet

- Ratio and ProportionDocument5 pagesRatio and Proportionsathyece9086No ratings yet

- Assignment 2-Mat2377-2018 PDFDocument2 pagesAssignment 2-Mat2377-2018 PDFJonny diggleNo ratings yet

- Exhumation and Design of Anchorages in Chalk Barley Mothersille Weerasinghe Ice Publication 2003Document22 pagesExhumation and Design of Anchorages in Chalk Barley Mothersille Weerasinghe Ice Publication 2003Kenny CasillaNo ratings yet

- Conditional StatementsDocument5 pagesConditional Statementsশেখ মিশারNo ratings yet

- Practice Worksheet: Graphing Quadratic Functions in Standard FormDocument2 pagesPractice Worksheet: Graphing Quadratic Functions in Standard FormAmyatz AndreiNo ratings yet

- Alternative Client-Server Ations (A) - (E) : Types of Distributed SystemsDocument51 pagesAlternative Client-Server Ations (A) - (E) : Types of Distributed SystemsAmudha ArulNo ratings yet

- TCS Question Bank Without AnswerDocument9 pagesTCS Question Bank Without AnswerGanesh MagarNo ratings yet

- 0580 m24 Ms 32 (Provisional)Document10 pages0580 m24 Ms 32 (Provisional)Hassan HussainNo ratings yet

- Arduino Tutorial OV7670 Camera ModuleDocument18 pagesArduino Tutorial OV7670 Camera ModuleKabilesh CmNo ratings yet

- Unit 5: Central Processing UnitDocument56 pagesUnit 5: Central Processing UnitgobinathNo ratings yet

- Rotinas de Teste em C Do Arduino Com X-Plane PDFDocument20 pagesRotinas de Teste em C Do Arduino Com X-Plane PDFNamedin Pereira TelesNo ratings yet

- Trimmed 21 Es q2 Week 3.2Document6 pagesTrimmed 21 Es q2 Week 3.2Nikha Mae BautistaNo ratings yet

- C-Line Drives Engineering Guide 11-2006-EnDocument568 pagesC-Line Drives Engineering Guide 11-2006-EnysaadanyNo ratings yet

- MalpDocument4 pagesMalpsuhradamNo ratings yet