Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Name and Terminology: History of Hominoid Taxonomy

Name and Terminology: History of Hominoid Taxonomy

Uploaded by

Karthi KeyanOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Name and Terminology: History of Hominoid Taxonomy

Name and Terminology: History of Hominoid Taxonomy

Uploaded by

Karthi KeyanCopyright:

Available Formats

Not logged in Talk Contributions Create account Log in

Article Talk Read View source View history Search Wikipedia

Ape

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Main page This article is about the branch of primates. For other uses, see Ape (disambiguation).

Contents

Apes (Hominoidea /hɒmɪˈnɔɪdiːə/) are a branch of Old World tailless simians native to Africa and Southeast Asia. They are the sister group of the Old World monkeys, together forming the catarrhine clade. They are distinguished from other primates by a wider degree of freedom of motion at the shoulder joint as evolved by the

Current events Hominoids or apes

Random article influence of brachiation. In traditional and non-scientific use, the term "ape" excludes humans, and can include tailless primates taxonomically considered monkeys (such as the Barbary ape and black ape), and is thus not equivalent to the scientific taxon Hominoidea. There are two extant branches of the superfamily

Temporal range: Miocene-Holocene

About Wikipedia Hominoidea: the gibbons, or lesser apes; and the hominids, or great apes.

Contact us

The family Hylobatidae, the lesser apes, include four genera and a total of sixteen species of gibbon, including the lar gibbon and the siamang, all native to Asia. They are highly arboreal and bipedal on the ground. They have lighter bodies and smaller social groups than great apes.

Donate

The family Hominidae (hominids), the great apes, include four genera comprising three extant species of orangutans and their subspecies, two extant species of gorillas and their subspecies, two extant species of panins (bonobos and chimpanzees) and their subspecies, and one extant species of humans in a single extant

Contribute subspecies.[1][a][2][3]

Help Except for gorillas and humans, hominoids are agile climbers of trees. Apes eat a variety of plant and animal foods, with the majority of food being plant foods, which can include fruit, leaves, stalks, roots and seeds, including nuts and grass seeds. Human diets are sometimes substantially different from that of other hominoids

Learn to edit

due in part to the development of technology and a wide range of habitation. Humans are by far the most numerous of the hominoid species, in fact outnumbering all other primates by a factor of several thousand to one.

Community portal

Recent changes All non-human hominoids are rare and endangered.[citation needed] The chief threat to most of the endangered species is loss of tropical rainforest habitat, though some populations are further imperiled by hunting for bushmeat. The great apes of Africa are also facing threat from the Ebola virus. Currently considered to be the

Upload file greatest threat to survival of African apes, Ebola infection is responsible for the death of at least one third of all gorillas and chimpanzees since 1990.[4]

Tools Contents [hide]

What links here 1 Name and terminology Sumatran orangutan (Pongo abelli)

Related changes 2 Evolution

Special pages Scientific classification

3 Taxonomic classification and phylogeny

Permanent link Kingdom: Animalia

3.1 History of hominoid taxonomy

Page information

3.2 Changes in taxonomy and terminology Phylum: Chordata

Cite this page

Wikidata item 4 Characteristics Class: Mammalia

4.1 Distinction from monkeys

Order: Primates

Print/export 5 Behaviour

Suborder: Haplorhini

Download as PDF 5.1 Diet

Printable version 5.2 Cognition Infraorder: Simiiformes

6 See also Parvorder: Catarrhini

In other projects

7 Notes

Superfamily: Hominoidea

Wikimedia Commons 8 References

Gray, 1825

Wikispecies

8.1 Literature cited

Type species

Languages 9 External links

Homo sapiens

বাংলা

Linnaeus, 1758

Español

Name and terminology Families

िहन्दी

മലയാളം "Ape", from Old English apa, is a word of uncertain origin.[b] The term has a history of rather imprecise usage—and of comedic or punning usage in the vernacular. Its earliest meaning was generally of any non-human anthropoid primate, [c] as is still the case for its cognates in other Germanic languages.[5] Later, after the term †Proconsulidae

ꯃꯤꯇꯩ ꯂꯣꯟ "monkey" had been introduced into English, "ape" was specialized to refer to a tailless (therefore exceptionally human-like) primate.[6] Thus, the term "ape" obtained two different meanings, as shown in the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica entry: it could be used as a synonym for "monkey" and it could denote the tailless human- †Afropithecidae

ਪੰਜਾਬੀ like primate in particular.[7]

த"# †Pliobatidae

!"# Some, or recently all, hominoids are also called "apes", but the term is used broadly and has several different senses within both popular and scientific settings. "Ape" has been used as a synonym for "monkey" or for naming any primate with a human-like appearance, particularly those without a tail.[7] Biologists have †Dendropithecidae

中⽂ traditionally used the term "ape" to mean a member of the superfamily Hominoidea other than humans,[1] but more recently to mean all members of Hominoidea. So "ape"—not to be confused with "great ape"—now becomes another word for hominoid including humans.[3][d] Hylobatidae

The taxonomic term hominoid is derived from, and intended as encompassing, the hominids, the family of great apes. Both terms were introduced by Gray (1825). The term hominins is also due to Gray (1824), intended as including the human lineage (see also Hominidae#Terminology, Human taxonomy). Hominidae

75 more

The distinction between apes and monkeys is complicated by the traditional paraphyly of monkeys: Apes emerged as a sister group of Old World Monkeys in the catarrhines, which are a sister group of New World Monkeys. Therefore, cladistically, apes, catarrhines and related contemporary extinct groups such as sister: Cercopithecoidea

Edit links

Parapithecidaea are monkeys as well, for any consistent definition of "monkey". "Old World Monkey" may also legitimately be taken to be meant to include all the catarrhines, including apes and extinct species such as Aegyptopithecus,[8][9][10][11][citation needed] in which case the apes, Cercopithecoidea and Aegyptopithecus Synonyms

emerged within the Old World Monkeys.

Proconsuloidea

The primates called "apes" today became known to Europeans after the 18th century. As zoological knowledge developed, it became clear that taillessness occurred in a number of different and otherwise distantly related species. Sir Wilfrid Le Gros Clark was one of those primatologists who developed the idea that there were

trends in primate evolution and that the extant members of the order could be arranged in an ".. ascending series", leading from "monkeys" to "apes" to humans. Within this tradition "ape" came to refer to all members of the superfamily Hominoidea except humans.[1] As such, this use of "apes" represented a paraphyletic

grouping, meaning that, even though all species of apes were descended from a common ancestor, this grouping did not include all the descendant species, because humans were excluded from being among the apes.[e]

Traditionally, the English-language vernacular name "apes" does not include humans, but phylogenetically, humans (Homo) form part of the family Hominidae within Hominoidaea. Thus, there are at least three common, or traditional, uses of the term "ape": non-specialists may not distinguish between "monkeys" and "apes", that is, they may use the two terms

interchangeably; or they may use "ape" for any tailless monkey or non-human hominoid; or they may use the term "ape" to just mean the non-human hominoids.

Modern taxonomy aims for the use of monophyletic groups for taxonomic classification;[12][f] Some literature may now use the common name "ape" to mean all members of the superfamily Hominoidea, including humans. For example, in his 2005 book, Benton wrote "The apes, Hominoidea, today include the gibbons and orang-utan ... the gorilla and chimpanzee ...

and humans".[3] Modern biologists and primatologists refer to apes that are not human as "non-human" apes. Scientists broadly, other than paleoanthropologists, may use the term "hominin" to identify the human clade, replacing the term "hominid". See terminology of primate names.

See below, History of hominoid taxonomy, for a discussion of changes in scientific classification and terminology regarding hominoids.

Evolution

This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (September 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

Although the hominoid fossil record is still incomplete and fragmentary, there is now enough evidence to provide an outline of the evolutionary history of humans. Previously, the divergence between humans and other extant hominoids was thought to have occurred 15 to 20 million years ago, and several species of that time period, such as Ramapithecus, were once

thought to be hominins and possible ancestors of humans. But, later fossil finds indicated that Ramapithecus was more closely related to the orangutan; and new biochemical evidence indicates that the last common ancestor of humans and non-hominins (that is, the chimpanzees) occurred between 5 and 10 million years ago, and probably nearer the lower end of

that range; see Chimpanzee–human last common ancestor (CHLCA).

Taxonomic classification and phylogeny

Genetic analysis combined with fossil evidence indicates that hominoids diverged from the Old World monkeys about 25 million years ago (mya), near the Oligocene-Miocene boundary.[13][14][15] The gibbons split from the rest about 18 mya, and the hominid splits happened 14 mya (Pongo),[16] 7 mya (Gorilla), and 3–5 mya (Homo & Pan).[17] In 2015, a new genus and

species were described, Pliobates cataloniae, which lived 11.6 mya, and appears to predate the split between Hominidae and Hylobatidae.[18][19][20][3] [clarification needed]

Crown Catharrhini (31) (29) Saadanioidea (†28)

Cercopithecoidea (24) Victoriapithecinae (†19)

Crown Cercopithecoidea

Hominoidea (30)

Dendropithecidae (†7 Mya)

Ekembo heseloni (†17 Mya)

Proconsulidae (†18 Mya)

Ekembo nyanzae (†17 Mya)

(29) Equatorius (†16)

Pliobates (†11.6 Mya)

(29) Afropithecidae (28)

Morotopithecus (†20)

Afropithecus (†16)

Crown Hominoidea (22) Hominidae

Hylobatidae

Catarrhini (31.0 Mya) Hominoidea/apes (20.4 Mya) Hominidae/great apes (15.7 Mya) Homininae (8.8 Mya) Hominini (6.3 Mya)

humans (genus Homo)

chimpanzees (genus Pan)

gorillas (genus Gorilla)

Traditional apes

orangutans (genus Pongo)

gibbons/lesser apes (family Hylobatidae)

Cercopithecoidea Old World monkeys

The families, and extant genera and species of hominoids are:

Superfamily Hominoidea[21]

Family Hominidae: hominids ("great apes")

Genus Pongo: orangutans

Bornean orangutan, P. pygmaeus

Sumatran orangutan, P. abelii

Tapanuli orangutan, P. tapanuliensis[22]

Genus Gorilla: gorillas

Western gorilla, G. gorilla

Eastern gorilla, G. beringei

Genus Homo: humans

Human, H. sapiens Skeletons of members of the ape superfamily, Hominoidea. There are two extant families:

Genus Pan: chimpanzees Hominidae, the "great apes"; and Hylobatidae, the gibbons, or "lesser apes".

Common chimpanzee, P. troglodytes

Bonobo, P. paniscus

Family Hylobatidae: gibbons ("lesser apes")

Genus Hylobates

Lar gibbon or white-handed gibbon, H. lar

Bornean white-bearded gibbon, H. albibarbis

Agile gibbon or black-handed gibbon, H. agilis

Western grey gibbon or Abbott's grey gibbon, H. abbotti[23]

Eastern grey gibbon or northern grey gibbon, H. funereus[23]

Müller's gibbon or southern grey gibbon, H. muelleri

Silvery gibbon, H. moloch

Pileated gibbon or capped gibbon, H. pileatus

From left: Comparison of size of gibbon, human, chimpanzee, gorilla and orangutan. Non-

Kloss's gibbon or Mentawai gibbon or bilou, H. klossii human hominoids do not stand upright as their normal posture.

Genus Hoolock

Western hoolock gibbon, H. hoolock

Eastern hoolock gibbon, H. leuconedys

Skywalker hoolock gibbon, H. tianxing

Genus Symphalangus

Siamang, S. syndactylus

Genus Nomascus

Northern buffed-cheeked gibbon, N. annamensis

Black crested gibbon, N. concolor

Eastern black crested gibbon, N. nasutus

Hainan black crested gibbon, N. hainanus

Southern white-cheeked gibbon N. siki

White-cheeked crested gibbon, N. leucogenys

Yellow-cheeked gibbon, N. gabriellae

History of hominoid taxonomy

Further information: Human taxonomy § History

The history of hominoid taxonomy is complex and somewhat confusing. Recent evidence has changed our understanding of the relationships between the hominoids, especially regarding the human lineage; and the traditionally used terms have become somewhat confused. Competing approaches to methodology and terminology are found among current scientific

sources. Over time, authorities have changed the names and the meanings of names of groups and subgroups as new evidence — that is, new discoveries of fossils and tools and of observations in the field, plus continual comparisons of anatomy and DNA sequences — has changed the understanding of relationships between hominoids. There has been a gradual

demotion of humans from being 'special' in the taxonomy to being one branch among many. This recent turmoil (of history) illustrates the growing influence on all taxonomy of cladistics, the science of classifying living things strictly according to their lines of descent.[citation needed]

Today, there are eight extant genera of hominoids. They are the four genera in the family Hominidae, namely Homo, Pan, Gorilla, and Pongo; plus four genera in the family Hylobatidae (gibbons): Hylobates, Hoolock, Nomascus and Symphalangus.[21] (The two subspecies of hoolock gibbons were recently moved from the genus Bunopithecus to the new genus

Hoolock and re-ranked as species; a third species was described in January 2017).[24])

In 1758, Carl Linnaeus, relying on second- or third-hand accounts, placed a second species in Homo along with H. sapiens: Homo troglodytes ("cave-dwelling man"). Although the term "Orang Outang" is listed as a variety – Homo sylvestris – under this species, it is nevertheless not clear to which animal this name refers, as Linnaeus had no specimen to refer to,

hence no precise description. Linnaeus may have based Homo troglodytes on reports of mythical creatures, then-unidentified simians, or Asian natives dressed in animal skins.[25] Linnaeus named the orangutan Simia satyrus ("satyr monkey"). He placed the three genera Homo, Simia and Lemur in the order of Primates.

The troglodytes name was used for the chimpanzee by Blumenbach in 1775, but moved to the genus Simia. The orangutan was moved to the genus Pongo in 1799 by Lacépède.

Linnaeus's inclusion of humans in the primates with monkeys and apes was troubling for people who denied a close relationship between humans and the rest of the animal kingdom. Linnaeus's Lutheran archbishop had accused him of "impiety". In a letter to Johann Georg Gmelin dated 25 February 1747, Linnaeus wrote:

It is not pleasing to me that I must place humans among the primates, but man is intimately familiar with himself. Let's not quibble over words. It will be the same to me whatever name is applied. But I desperately seek from you and from the whole world a general difference between men and simians from the principles of Natural History. I certainly know

of none. If only someone might tell me one! If I called man a simian or vice versa I would bring together all the theologians against me. Perhaps I ought to, in accordance with the law of Natural History.[26]

Accordingly, Johann Friedrich Blumenbach in the first edition of his Manual of Natural History (1779), proposed that the primates be divided into the Quadrumana (four-handed, i.e. apes and monkeys) and Bimana (two-handed, i.e. humans). This distinction was taken up by other naturalists, most notably Georges Cuvier. Some elevated the distinction to the level of

order.

However, the many affinities between humans and other primates – and especially the "great apes" – made it clear that the distinction made no scientific sense. In his 1871 book The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex, Charles Darwin wrote:

The greater number of naturalists who have taken into consideration the whole structure of man, including his mental faculties, have followed Blumenbach and Cuvier, and have placed man in a separate Order, under the title of the Bimana, and therefore on an equality with the orders of the Quadrumana, Carnivora, etc. Recently many of our best

naturalists have recurred to the view first propounded by Linnaeus, so remarkable for his sagacity, and have placed man in the same Order with the Quadrumana, under the title of the Primates. The justice of this conclusion will be admitted: for in the first place, we must bear in mind the comparative insignificance for classification of the great development

of the brain in man, and that the strongly marked differences between the skulls of man and the Quadrumana (lately insisted upon by Bischoff, Aeby, and others) apparently follow from their differently developed brains. In the second place, we must remember that nearly all the other and more important differences between man and the Quadrumana are

manifestly adaptive in their nature, and relate chiefly to the erect position of man; such as the structure of his hand, foot, and pelvis, the curvature of his spine, and the position of his head.[27]

Changes in taxonomy and terminology

See also: Hominidae and Human taxonomy

Humans the non-apes: Until about 1960, taxonomists typically divided the superfamily Hominoidea into two families. The science community treated humans and their extinct relatives as the outgroup within the superfamily; that is, humans were considered as quite distant from kinship with the

"apes". Humans were classified as the family Hominidae and were known as the "hominids". All other hominoids were known as "apes" and were referred to the family Pongidae.[28]

The "great apes" in Pongidae: The 1960s saw the methodologies of molecular biology applied to primate taxonomy. Goodman's 1964 immunological study of serum proteins led to re-classifying the hominoids into three families: the humans in Hominidae; the great apes in Pongidae; and the

"lesser apes" (gibbons) in Hylobatidae.[29] However, this arrangement had two trichotomies: Pan, Gorilla, and Pongo of the "great apes" in Pongidae, and Hominidae, Pongidae, and Hylobatidae in Hominoidea. These presented a puzzle; scientists wanted to know which genus speciated first from

the common hominoid ancestor.

Gibbons the outgroup: New studies indicated that gibbons, not humans, are the outgroup within the superfamily Hominoidea, meaning: the rest of the hominoids are more closely related to each other than (any of them) are to the gibbons. With this splitting, the gibbons (Hylobates, et al.) were

isolated after moving the great apes into the same family as humans. Now the term "hominid" encompassed a larger collective taxa within the family Hominidae. With the family trichotomy settled, scientists could now work to learn which genus is 'least' related to the others in the subfamily Ponginae.

Orangutans the outgroup: Investigations comparing humans and the three other hominid genera disclosed that the African apes (chimpanzees and gorillas) and humans are more closely related to each other than any of them are to the Asian orangutans (Pongo); that is, the orangutans, not

humans, are the outgroup within the family Hominidae. This led to reassigning the African apes to the subfamily Homininae with humans—which presented a new three-way split: Homo, Pan, and Gorilla.[30]

Hominins: In an effort to resolve the trichotomy, while preserving the nostalgic "outgroup" status of humans, the subfamily Homininae was divided into two tribes: Gorillini, comprising genus Pan and genus Gorilla; and Hominini, comprising genus Homo (the humans). Humans and close relatives

now began to be known as "hominins", that is, of the tribe Hominini. Thus, the term "hominin" succeeded to the previous use of "hominid", which meaning had changed with changes in Hominidae (see above: 3rd graphic, "Gibbons the outgroup").

Gorillas the outgroup: New DNA comparisons now provided evidence that gorillas, not humans, are the outgroup in the subfamily Homininae; this suggested that chimpanzees should be grouped with humans in the tribe Hominini, but in separate subtribes.[31] Now the name "hominin" delineated

Homo plus those earliest Homo relatives and ancestors that arose after the divergence from the chimpanzees. (Humans are no longer classified as an outgroup, but are a branch, deep in the tree of the pre-1960s ape group).

Speciation of gibbons: Later DNA comparisons disclosed previously unknown speciation of genus Hylobates (gibbons) into four genera: Hylobates, Hoolock, Nomascus, and Symphalangus.[21][24]

Characteristics

This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (July 2011) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

The lesser apes are the gibbon family, Hylobatidae, of sixteen species; all are native to Asia. Their major differentiating characteristic is their long arms, which they use to brachiate through trees. Their wrists are ball and socket joints as an evolutionary adaptation to their arboreal lifestyle. Generally smaller than the African apes,

the largest gibbon, the siamang, weighs up to 14 kg (31 lb); in comparison, the smallest "great ape", the bonobo, is 34 to 60 kg (75 to 132 lb).

The superfamily Hominoidea falls within the parvorder Catarrhini, which also includes the Old World monkeys of Africa and Eurasia. Within this grouping, the two families Hylobatidae and Hominidae can be distinguished from Old World monkeys by the number of cusps on their molars; hominoids have five in the "Y-5" molar

pattern, whereas Old World monkeys have only four in a bilophodont pattern.

Further, in comparison with Old World monkeys, hominoids are noted for: more mobile shoulder joints and arms due to the dorsal position of the scapula; broader ribcages that are flatter front-to-back; and a shorter, less mobile spine, with greatly reduced caudal (tail) vertebrae—resulting in complete loss of the tail in extant

hominoid species. These are anatomical adaptations, first, to vertical hanging and swinging locomotion (brachiation) and, later, to developing balance in a bipedal pose. Note there are primates in other families that also lack tails, and at least one, the pig-tailed langur, is known to walk significant distances bipedally. The front of

the ape skull is characterised by its sinuses, fusion of the frontal bone, and by post-orbital constriction.

Distinction from monkeys

See also: Monkey § Historical and modern terminology

Cladistically, apes, catarrhines, and extinct species such as Aegyptopithecus and Parapithecidaea, are monkeys,[citation needed] so one can only specify ape features not present in other monkeys.

Unlike most monkeys, apes do not possess a tail. Monkeys are more likely to be in trees and use their tails for balance. While the great apes are considerably larger than monkeys, gibbons (lesser apes) are smaller than some monkeys. Apes are considered to be more intelligent than monkeys, which are considered to have

more primitive brains.[32]

Like those of the orangutan, the

shoulder joints of hominoids are

adapted to brachiation, or movement by Behaviour

swinging in tree branches.

Major studies of behaviour in the field were completed on the three better-known "great apes", for example by Jane Goodall, Dian Fossey and Birute Galdikas. These studies have shown that in their natural environments, the non-human hominoids show sharply varying social structure: gibbons are monogamous, territorial pair-

bonders, orangutans are solitary, gorillas live in small troops with a single adult male leader, while chimpanzees live in larger troops with bonobos exhibiting promiscuous sexual behaviour. Their diets also vary; gorillas are foliovores, while the others are all primarily frugivores, although the common chimpanzee hunts for meat.

Foraging behaviour is correspondingly variable.

Diet

Apart from humans and gorillas, apes eat a predominantly frugivorous diet, mostly fruit, but supplemented with a variety of other foods. Gorillas are predominately folivorous, eating mostly stalks, shoots, roots and leaves with some fruit and other foods. Non-human apes usually eat a small amount of raw animal foods such as insects or eggs. In the case of humans,

migration and the invention of hunting tools and cooking has led to an even wider variety of foods and diets, with many human diets including large amounts of cooked tubers (roots) or legumes.[33] Other food production and processing methods including animal husbandry and industrial refining and processing have further changed human diets.[34] Humans and other

apes occasionally eat other primates.[35] Some of these primates are now close to extinction with habitat loss being the underlying cause.[36][37]

Cognition

This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (July 2011) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

All the non-human hominoids are generally thought of as highly intelligent, and scientific study has broadly confirmed that they perform very well on a wide range of cognitive tests—though there is relatively little data on gibbon cognition. The early studies by Wolfgang Köhler demonstrated exceptional problem-solving abilities in

chimpanzees, which Köhler attributed to insight. The use of tools has been repeatedly demonstrated; more recently, the manufacture of tools has been documented, both in the wild and in laboratory tests. Imitation is much more easily demonstrated in "great apes" than in other primate species. Almost all the studies in animal

language acquisition have been done with "great apes", and though there is continuing dispute as to whether they demonstrate real language abilities, there is no doubt that they involve significant feats of learning. Chimpanzees in different parts of Africa have developed tools that are used in food acquisition, demonstrating a

form of animal culture.[38]

See also

Dawn of Humanity (2015 PBS film) List of individual apes (for notable non-fictional non-human apes) List of fictional primates

Declaration on Great Apes from the Great Ape Project List of primates by population

Notes

a. ^ Although Dawkins is clear that he uses "apes" for Hominoidea, he also uses "great apes" in ways which exclude humans. Thus in Dawkins 2005: "Long before people thought in terms of evolution ... great apes were often confused with humans" (p. 114); "gibbons are faithfully monogamous, unlike the great apes which are our closer relatives"

(p. 126).

b. ^ The hypothetical Proto-Germanic form is given as *apōn (F. Kluge, Etymologisches Wörterbuch der Deutschen Sprache (2002), online version, s.v. "Affe "; V. Orel, A handbook of Germanic etymology (2003), s.v. "*apōn " or as *apa(n) (Online Etymology Dictionary (2001–2014), s.v. "ape "; M. Philippa, F. Debrabandere, A. Quak, T.

Schoonheim & N. van der Sijs, Etymologisch woordenboek van het Nederlands (2003–2009), s.v. "aap "). Perhaps ultimately derived from a non-Indo-European language, the word might be a direct borrowing from Celtic, or perhaps from Slavic, although in both cases it is also argued that the borrowing, if it took place, went in the opposite

direction.

c. ^ "Any simian known on the Mediterranean during the Middle Ages; monkey or ape"; cf. ape-ward: "a juggler who keeps a trained monkey for the amusement of the crowd." (Middle English Dictionary, s.v. "ape ").

d. ^ Dawkins 2005; for example "[a]ll apes except humans are hairy" (p. 99), "[a]mong the apes, gibbons are second only to humans" (p. 126).

e. ^ Definitions of paraphyly vary; for the one used here see e.g. Stace 2010, pp. 106

f. ^ Definitions of monophyly vary; for the one used here see e.g. Mishler 2009, pp. 114

References

1. ^ a b c Dixson 1981, pp. 13. 10. ^ Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, M. É. (1812). "Tableau des 16. ^ Alba, D. M.; Fortuny, J.; Moyà-Solà, S. (2010). "Enamel 22. ^ Cochrane, J. (2 November 2017). "New Orangutan Species 30. ^ Goodman, M. (1974). "Biochemical evidence on hominid

2. ^ Grehan, J. R. (2006). "Mona Lisa smile: the morphological quadrumanes, ou des animaux composant le premier ordre thickness in the Middle Miocene great apes Anoiapithecus, Could Be the Most Endangered Great Ape" . The New York phylogeny". Annual Review of Anthropology. 3 (1): 203–228.

enigma of human and great ape evolution" . Anatomical de la classe des Mammifères" . Annales du Muséum Pierolapithecus and Dryopithecus" . Proceedings of the Times. Retrieved 3 November 2017. doi:10.1146/annurev.an.03.100174.001223 . A series of images showing a gorilla

d'Histoire Naturelle. Paris. 19: 85–122. Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 277 (1691): ab utilizing a small tree trunk as a tool to

Record. 289B (4): 139–157. doi:10.1002/ar.b.20107 . 23. ^ Sonstige, Wilson, Don E. 1944- Hrsg. Cavallini, Paolo 31. ^ Goodman, M.; Tagle, D. A.; Fitch, D. H.; et al. (1990).

PMID 16865704 . 11. ^ Bugge, J. (1974). "Chapter 4". Cells Tissues Organs. 87 2237–2245. doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.0218 . ISSN 0962- (2013). Handbook of the mammals of the world . Lynx "Primate evolution at the DNA level and a classification of maintain balance as she fished for

aquatic herbs

3. ^ a b c d Benton, M. J. (2005). Vertebrate Palaeontology . (Suppl. 62): 32–43. doi:10.1159/000144209 . ISSN 1422- 8452 . PMC 2880156 . PMID 20335211 . Edicions. ISBN 978-84-96553-89-7. OCLC 1222638259 . hominoids". Journal of Molecular Evolution. 30 (3): 260–266.

Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-632-05637-8. Retrieved 10 July 6405 . 17. ^ Grabowski, M.; Jungers, W. L. (2017). "Evidence of a 24. ^ a b Mootnick, A.; Groves, C. P. (2005). "A new generic name Bibcode:1990JMolE..30..260G .

2011., p. 371 12. ^ Springer; D. H. (1 July 2011). An Introduction to Zoology: chimpanzee-sized ancestor of humans but a gibbon-sized for the hoolock gibbon (Hylobatidae)". International Journal of doi:10.1007/BF02099995 . PMID 2109087 .

Mammals portal

4. ^ Rush, J. (23 January 2015). "Ebola virus 'has killed a third Investigating the Animal World. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. ancestor of apes" . Nature Communications. 8 (1): 880. Primatology. 26 (4): 971–976. doi:10.1007/s10764-005-5332- S2CID 2112935 .

of world's gorillas and chimpanzees' – and could pose p. 536. ISBN 978-0-7637-5286-6. "Through careful study Bibcode:2017NatCo...8..880G . doi:10.1038/s41467-017- 4 . S2CID 8394136 . 32. ^ Call, J.; Tomasello, M. (2007). The Gestural

greatest threat to their survival, conservationists warn" . The taxonomists today struggle to eliminate polyphyletic and 00997-4 . ISSN 2041-1723 . PMC 5638852 . 25. ^ Frängsmyr, T.; Lindroth, S.; Eriksson, G.; Broberg, G. Communication of Apes and Monkeys. Taylor & Francis

Independent. Archived from the original on 30 March 2015. paraphyletic groups and taxons, reclassifying their members PMID 29026075 . (1983). Linnaeus, the man and his work. Berkeley and Los Group/Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Retrieved 26 March 2015. into appropriate monophyletic taxa" 18. ^ "A new primate species at the root of the tree of extant Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-7112- 33. ^ Lawton, G. (2 November 2016). "Every human culture

5. ^ Terry 1977, pp. 3. 13. ^ "Fossils may pinpoint critical split between apes and hominoids" . 29 October 2015. 1841-3., p. 166 includes cooking – this is how it began" . New Scientist.

6. ^ Terry 1977, pp. 3–4. monkeys" . 15 May 2013. 19. ^ Nengo, I.; Tafforeau, P.; Gilbert, C. C.; et al. (2017). "New 26. ^ "Letter, Carl Linnaeus to Johann Georg Gmelin. Uppsala, 34. ^ Hoag, Hannah (2 December 2013). "Humans are becoming

7. ^ a b Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Ape" . Encyclopædia 14. ^ Rossie, J. B.; Hill, A. (2018). "A new species of Simiolus infant cranium from the African Miocene sheds light on ape Sweden, 25 February 1747" . Swedish Linnaean Society. more carnivorous" . Nature.

Britannica. 2 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 160. from the middle Miocene of the Tugen Hills, Kenya". Journal evolution" (PDF). Nature. 548 (7666): 169–174. 27. ^ Darwin, C. (1871). The Descent of Man. ISBN 978-0-7607- doi:10.1038/nature.2013.14282 . S2CID 183143537 .

8. ^ Osman Hill, W. C. (1953). Primates Comparative Anatomy of Human Evolution. 125: 50–58. Bibcode:2017Natur.548..169N . 7814-2. 35. ^ Callaway, E. (13 October 2006). "Loving bonobos have a

and Taxonomy I—Strepsirhini. Edinburgh Univ Pubs Science doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2018.09.002 . PMID 30502897 . doi:10.1038/nature23456 . PMID 28796200 . 28. ^ G. G., Simpson (1945). "The principles of classification and carnivorous dark side" . New Scientist. Retrieved

& Maths, No 3. Edinburgh University Press. p. 53. S2CID 54625375 . S2CID 4397839 . Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 a classification of mammals". Bulletin of the American 26 November 2014.

OCLC 500576914 . 15. ^ Rasmussen, D. T.; Friscia, A. R.; Gutierrez, M.; et al. July 2018. Retrieved 15 July 2019. Museum of Natural History. 85: 1–350. 36. ^ M., Michael. "Chimpanzees over-hunt monkey prey almost

9. ^ Martin, W. C. L. (1841). A General Introduction to the (2019). "Primitive Old World monkey from the earliest 20. ^ Dixson 1981, p. 16. 29. ^ Goodman, M. (1964). "Man's place in the phylogeny of the to extinction" . BBC Earth.

abc

Natural History of Mammiferous Animals, With a Particular Miocene of Kenya and the evolution of cercopithecoid 21. ^ Groves, C. P. (2005). Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. primates as reflected in serum proteins". In Washburn, S. L. 37. ^ "Extinction threat to monkeys and other primates due to

View of the Physical History of man, and the More Closely bilophodonty" . Proceedings of the National Academy of (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and (ed.). Classification and Human Evolution. Chicago: Aldine. habitat loss, hunting" . Science Daily.

Allied Genera of the Order Quadrumana, or Monkeys . Sciences. 116 (13): 6051–6056. Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins pp. 204–234. 38. ^ McGrew, W. (1992). Chimpanzee Material Culture:

London: Wright and Co. printers. pp. 340, 361. doi:10.1073/pnas.1815423116 . PMC 6442627 . University Press. pp. 178–184. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. Implications for Human Evolution.

PMID 30858323 . OCLC 62265494 .

Literature cited

Dawkins, R. (2005). The Ancestor's Tale (p/b ed.). London: Phoenix (Orion Books). ISBN 978-0-7538-1996-8.

Dixson, A. F. (1981). The Natural History of the Gorilla. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-77895-0.

Mishler, Brent D (2009). "Species are not uniquely real biological entities". In Ayala, F. J. & Arp, R. (eds.). Contemporary Debates in Philosophy of Biology. pp. 110–122. doi:10.1002/9781444314922.ch6 . ISBN 978-1-4443-1492-2.

Stace, C. A. (2010). "Classification by molecules: what's in it for field botanists?" (PDF). Watsonia. 28: 103–122. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

Terry, M. W. (1977). "Use of common and scientific nomenclature to designate laboratory primates". In Schrier, A. M. (ed.). Behavioral Primatology: Advances in Research and Theory. Volume 1. Hillsdale, N.J., USA: Lawrence Erlbaum.

External links

Data related to Hominoidea at Wikispecies

Look up ape in Wiktionary,

Hominoidea at Wikibooks the free dictionary.

Pilbeam D. (September 2000). "Hominoid systematics: The soft evidence" . Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97 (20): 10684–6. Bibcode:2000PNAS...9710684P . doi:10.1073/pnas.210390497 . PMC 34045 . PMID 10995486 . Agreement between cladograms based on molecular and anatomical data.

Human Timeline (Interactive) – Smithsonian, National Museum of Natural History (August 2016). Ape

at Wikipedia's sister projects

Definitions from Wiktionary

Media from Commons

News from Wikinews

Quotations from Wikiquote

Texts from Wikisource

Textbooks from Wikibooks

Resources from Wikiversity

V ·T ·E Apes [show]

V ·T ·E Notable non-human apes [show]

V ·T ·E Extant primate families [show]

V ·T ·E Haplorhini [show]

Taxon identifiers Wikidata: Q102470 · Wikispecies: Hominoidea · ADW: Hominoidea · EoL: 4529848 · Fossilworks: 40883 · iNaturalist: 1036675 · ITIS: 943782 · MSW: 12100751 · NCBI: 314295

Authority control [show]

Categories: Apes Extant Chattian first appearances Taxa named by John Edward Gray

This page was last edited on 9 January 2022, at 15:51 (UTC).

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License; additional terms may apply. By using this site, you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy. Wikipedia® is a registered trademark of the Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., a non-profit organization.

Privacy policy About Wikipedia Disclaimers Contact Wikipedia Mobile view Developers Statistics Cookie statement

You might also like

- PDF Logo Modernism English French and German Edition PDFDocument5 pagesPDF Logo Modernism English French and German Edition PDFKarthi Keyan0% (1)

- Lesson Book-Drumming MonkeyDocument51 pagesLesson Book-Drumming Monkeychewaka999100% (2)

- The Song of The Ape Understanding The Languages of ChimpanzeesDocument11 pagesThe Song of The Ape Understanding The Languages of ChimpanzeesMacmillan Publishers50% (2)

- HominidaeDocument1 pageHominidaeKarthi KeyanNo ratings yet

- HomoDocument3 pagesHomoPlanet CscNo ratings yet

- Ch-2 QAs XDocument8 pagesCh-2 QAs Xsharma.hansrajNo ratings yet

- Euro Anglais 1Document1 pageEuro Anglais 1hugoNo ratings yet

- Mario FERNÁNDEZ-MAZUECOS, Beverley J. GLOVER : BackgroundDocument1 pageMario FERNÁNDEZ-MAZUECOS, Beverley J. GLOVER : BackgroundMario Fernández-MazuecosNo ratings yet

- What Bugs Hawaii: RoachesDocument1 pageWhat Bugs Hawaii: RoachesHonolulu Star-AdvertiserNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Presocratic PhilosophyDocument26 pagesChapter 1 Presocratic Philosophyadmin0123No ratings yet

- NWFP 5 Edible NutsDocument209 pagesNWFP 5 Edible Nutscavris100% (2)

- Tropical Rainforest Biomes HandoutDocument4 pagesTropical Rainforest Biomes HandoutSamana FatimaNo ratings yet

- Law and Agriculture Final DraftDocument15 pagesLaw and Agriculture Final DraftVipul GautamNo ratings yet

- Ratfolk (DND)Document15 pagesRatfolk (DND)Lennox StevensonNo ratings yet

- Chapter 7 Intangible HeritageDocument39 pagesChapter 7 Intangible HeritageJohn JuliusNo ratings yet

- TISSUES WORKSHEET (Till Epithelial Tissue)Document4 pagesTISSUES WORKSHEET (Till Epithelial Tissue)Mohammad Saif RazaNo ratings yet

- What Is The Materials' Origin of Humans? How Did Our Universe Come Into Existence?Document1 pageWhat Is The Materials' Origin of Humans? How Did Our Universe Come Into Existence?ArselNo ratings yet

- Flobackkevin 142388 11947065 Buzz Buzz Buzz-1Document3 pagesFlobackkevin 142388 11947065 Buzz Buzz Buzz-1api-624354210No ratings yet

- Free (PDF) Download Science Encyclopedia: Atom Smashing, Food Chemistry, Animals, Space, and More! (Encyclopaedia) Book OnlineDocument1 pageFree (PDF) Download Science Encyclopedia: Atom Smashing, Food Chemistry, Animals, Space, and More! (Encyclopaedia) Book Onlinemanish_iitrNo ratings yet

- Parshas Tzav Assembly QuestionsDocument1 pageParshas Tzav Assembly QuestionsSarabayla WinebergNo ratings yet

- Thebridgelifeinthemix Info Epstein's Pandemic Web Archive Org Web 20230214150525 Thebridgelifeinthemix Info Australia PandemicDocument7 pagesThebridgelifeinthemix Info Epstein's Pandemic Web Archive Org Web 20230214150525 Thebridgelifeinthemix Info Australia PandemicCazzac111No ratings yet

- Scientists Study How A Single Gene Alteration May Have SeparatedDocument7 pagesScientists Study How A Single Gene Alteration May Have SeparatedRT CrNo ratings yet

- PALYNOLOGY For StudentDocument50 pagesPALYNOLOGY For StudentdkurniadiNo ratings yet

- Term PaperDocument7 pagesTerm Paperapi-321898622No ratings yet

- GR Test - 1 S3Document2 pagesGR Test - 1 S3Samarpana Kumar EizzinaNo ratings yet

- Document 1Document6 pagesDocument 1JoharNo ratings yet

- Giz2015 en Agrobiodiversity Factsheet Collection PDFDocument52 pagesGiz2015 en Agrobiodiversity Factsheet Collection PDFKanchan Kumar Agrawal100% (1)

- Environment and Ecology Do You Believe?Document36 pagesEnvironment and Ecology Do You Believe?blank spaceNo ratings yet

- Garrido 2014 Ceramica Punta BravaDocument18 pagesGarrido 2014 Ceramica Punta Bravacatalina.salgadmNo ratings yet

- AF-Raysofthe WorldredDocument3 pagesAF-Raysofthe WorldredHammurabi RamirezNo ratings yet

- Donkey - WikipediaDocument1 pageDonkey - WikipediajavierNo ratings yet

- Roy Berkeley 0028E 11440Document162 pagesRoy Berkeley 0028E 11440Leidy CampoNo ratings yet

- Power of Productivity LewisDocument12 pagesPower of Productivity LewissnegcarNo ratings yet

- Classic Proxy Warfare - Ethio EritreanDocument92 pagesClassic Proxy Warfare - Ethio EritreaneazeackNo ratings yet

- Los Detectiv Los Detectives Salv Es Salvajes y La No Ajes y La Novela Del Ar Ela Del Archivo Cultur o CulturalDocument21 pagesLos Detectiv Los Detectives Salv Es Salvajes y La No Ajes y La Novela Del Ar Ela Del Archivo Cultur o Culturaljorge agustin VillavicencioNo ratings yet

- (PDF) FLORA Y VEGETACIÓN DE LA COMPAÑÍA PIKYSYRY, CAACUPÉ, DEPARTAMENTO DE CORDILLERA, PARAGUAY - (Flora and Vegetation of The CDocument1 page(PDF) FLORA Y VEGETACIÓN DE LA COMPAÑÍA PIKYSYRY, CAACUPÉ, DEPARTAMENTO DE CORDILLERA, PARAGUAY - (Flora and Vegetation of The Cgj5sgwp4hzNo ratings yet

- Unit I Biological EvolutionDocument37 pagesUnit I Biological EvolutionAshishNo ratings yet

- Fibre As An Ecosystem ServiceDocument9 pagesFibre As An Ecosystem ServiceSimi ANo ratings yet

- CPI PI Unit4 1Document10 pagesCPI PI Unit4 1MikeNo ratings yet

- Sciencebrochuretemplate 1Document3 pagesSciencebrochuretemplate 1api-356824125No ratings yet

- Environment Science DADocument3 pagesEnvironment Science DAKritikaNo ratings yet

- The Linguistic Background Intellectual R PDFDocument27 pagesThe Linguistic Background Intellectual R PDFАляксандр БойкоNo ratings yet

- Diffusion and OsmosisDocument9 pagesDiffusion and OsmosisozmanNo ratings yet

- Soul of SolDocument6 pagesSoul of SolJoel KahnNo ratings yet

- Only A BinDocument1 pageOnly A Bin7115 ธนภรณ์ ผิวเกลี้ยงNo ratings yet

- Chapter.1 Introducing Biology: A. Characteristics of OrganismsDocument1 pageChapter.1 Introducing Biology: A. Characteristics of Organismsng, ashley yuet heiNo ratings yet

- NWFP 15 Non-Wood Forest Products From Temperate Broad-Leaved TreesDocument133 pagesNWFP 15 Non-Wood Forest Products From Temperate Broad-Leaved TreescavrisNo ratings yet

- Philippine AegleDocument3 pagesPhilippine AegleFon XingNo ratings yet

- Poster BDocument1 pagePoster Bc_j_grassaNo ratings yet

- Oh Say Can You Say Dinosaur - Extension FormDocument2 pagesOh Say Can You Say Dinosaur - Extension Formapi-550368270No ratings yet

- Kaitsi Kagami Reference SheetDocument2 pagesKaitsi Kagami Reference Sheetjohnathandough699No ratings yet

- Permaculture For RefugeesDocument20 pagesPermaculture For RefugeestasoscribdNo ratings yet

- CLJ 1000 1Document148 pagesCLJ 1000 1Arjay MartinezNo ratings yet

- Marion A4Document1 pageMarion A4infobitsNo ratings yet

- Exercise 12: Water Quaity Data Collection: Lake Merritt Channel StudiesDocument9 pagesExercise 12: Water Quaity Data Collection: Lake Merritt Channel StudiesBETT GIDEONNo ratings yet

- Natori Ryu Complete Skill List - Heika Jodan (Scroll 1)Document60 pagesNatori Ryu Complete Skill List - Heika Jodan (Scroll 1)Douglas RadcliffeNo ratings yet

- Duane Rousselle, PHD: Phone: +1 705 492 9823Document10 pagesDuane Rousselle, PHD: Phone: +1 705 492 9823Duane RousselleNo ratings yet

- A Study On Traditional Mother Care PlantsDocument6 pagesA Study On Traditional Mother Care PlantsBarnali DuttaNo ratings yet

- Transitions Sorting 1 Look at The Words and Divide Them Into The Categories BelowDocument2 pagesTransitions Sorting 1 Look at The Words and Divide Them Into The Categories BelowAngel SerratoNo ratings yet

- Textbook of Anatomy Upper Limb 1Document1 pageTextbook of Anatomy Upper Limb 1Karpagam S0% (1)

- Menageries Roman Empire Zoological Gardens Cultural Depictions of Lions Upper Paleolithic Lascaux Chauvet CavesDocument1 pageMenageries Roman Empire Zoological Gardens Cultural Depictions of Lions Upper Paleolithic Lascaux Chauvet CavesFranko MilovanNo ratings yet

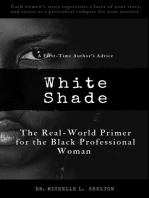

- White Shade: The Real-World Primer for the Black Professional WomanFrom EverandWhite Shade: The Real-World Primer for the Black Professional WomanNo ratings yet

- Myriad All-Flash File and Object Storage - QuantumDocument1 pageMyriad All-Flash File and Object Storage - QuantumKarthi KeyanNo ratings yet

- Myriad PB00067ADocument8 pagesMyriad PB00067AKarthi KeyanNo ratings yet

- Compass - QDE - Quantum Data EnginesDocument1 pageCompass - QDE - Quantum Data EnginesKarthi KeyanNo ratings yet

- QDE - Quantum Data Engines - 10 Years of Inspiring TrustDocument1 pageQDE - Quantum Data Engines - 10 Years of Inspiring TrustKarthi KeyanNo ratings yet

- Construction Technology - Understand Building ConstructionDocument1 pageConstruction Technology - Understand Building ConstructionKarthi KeyanNo ratings yet

- How To Vote in India? - Process, Eligibility, Documents, Registration - ILDocument1 pageHow To Vote in India? - Process, Eligibility, Documents, Registration - ILKarthi KeyanNo ratings yet

- India Vs Bangladesh Relations: Partition, Partnership & Regional StabilityDocument1 pageIndia Vs Bangladesh Relations: Partition, Partnership & Regional StabilityKarthi KeyanNo ratings yet

- FM Isecurity 524654Document1 pageFM Isecurity 524654Karthi KeyanNo ratings yet

- Marketing Procedure PDF - Google SearchDocument1 pageMarketing Procedure PDF - Google SearchKarthi KeyanNo ratings yet

- InvoiceDocument1 pageInvoiceKarthi KeyanNo ratings yet

- Scheduled Monument: 1973 Is An Act of The Parliament ofDocument1 pageScheduled Monument: 1973 Is An Act of The Parliament ofKarthi KeyanNo ratings yet

- Wik223i 1Document1 pageWik223i 1Karthi KeyanNo ratings yet

- Wiki 1Document1 pageWiki 1Karthi KeyanNo ratings yet

- Help:Pronunciation Respelling Key: Information PageDocument1 pageHelp:Pronunciation Respelling Key: Information PageKarthi KeyanNo ratings yet

- Anthropology Appreciating Human Diversity 15th Edition Kottak Test Bank Full Chapter PDFDocument47 pagesAnthropology Appreciating Human Diversity 15th Edition Kottak Test Bank Full Chapter PDFErikaJonestism100% (15)

- 1991 MC Review, Primate VisionsDocument10 pages1991 MC Review, Primate VisionsJay SunNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Anthropology: Study Guide For Module No. - 1Document44 pagesIntroduction To Anthropology: Study Guide For Module No. - 1Lysander Garcia100% (1)

- (Nathan J. Emery, Nicola S. Clayton - Comparative Animal CognitionDocument392 pages(Nathan J. Emery, Nicola S. Clayton - Comparative Animal CognitioncsuciavaNo ratings yet

- Baboons With BriefcasesDocument28 pagesBaboons With Briefcasesfawkes316No ratings yet

- Holly Fuong CVDocument4 pagesHolly Fuong CVapi-511250809No ratings yet

- The Ethnoprimatological Approach in PrimatologyDocument7 pagesThe Ethnoprimatological Approach in PrimatologyGerardo RiveroNo ratings yet

- 4 5764721416976992006 PDFDocument59 pages4 5764721416976992006 PDFMintesnot Tilahun100% (1)

- Ii¡2111 UI I 111: Biblioteca ContaderoDocument16 pagesIi¡2111 UI I 111: Biblioteca Contaderomonica Maldonado100% (1)

- Vita 2023 Post Academic Configuration Emortitus April 1 Website Version Current As of April 7 2023Document16 pagesVita 2023 Post Academic Configuration Emortitus April 1 Website Version Current As of April 7 2023api-618317598No ratings yet

- Module 1Document36 pagesModule 1David BurkeNo ratings yet

- Anthropology of Habitat and ArchitectureDocument16 pagesAnthropology of Habitat and ArchitectureJordan Kurt S. GuNo ratings yet

- A Japanese View of Nature the World of Living Things by Kinji Imanishi 今西, 錦司, Asquith, Pamela J.Document153 pagesA Japanese View of Nature the World of Living Things by Kinji Imanishi 今西, 錦司, Asquith, Pamela J.Janina TiemiNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Anthropology: Study Guide For Module No. - 1Document31 pagesIntroduction To Anthropology: Study Guide For Module No. - 1Anna LieseNo ratings yet

- Sex at DawnDocument617 pagesSex at DawnAigab072279% (14)

- Bio AnthroDocument6 pagesBio AnthroSaaraNo ratings yet

- Measuring Foraging BehaviourDocument39 pagesMeasuring Foraging BehaviourOriolNo ratings yet

- The Ape in The OfficeDocument3 pagesThe Ape in The OfficeSofia Restrepo ValenciaNo ratings yet

- Encounters With Animal Minds: Journal of Consciousness StudiesDocument17 pagesEncounters With Animal Minds: Journal of Consciousness StudiesmanuelNo ratings yet

- Early Evolution of PrimatesDocument2 pagesEarly Evolution of Primatesnikita bajpaiNo ratings yet

- Anthropology PPT (2022)Document186 pagesAnthropology PPT (2022)mulatu mokononNo ratings yet

- Unit One Introducing Anthropology and Its Subject Matter 1.1.1 Definition and Concepts in AnthropologyDocument39 pagesUnit One Introducing Anthropology and Its Subject Matter 1.1.1 Definition and Concepts in AnthropologyhenosNo ratings yet

- Anne Fausto-Sterling - Essay Review. Primate Visions, A Model For Historians of ScienceDocument5 pagesAnne Fausto-Sterling - Essay Review. Primate Visions, A Model For Historians of ScienceStathis PapastathopoulosNo ratings yet

- Monkey Smile at DuckDuckGoDocument1 pageMonkey Smile at DuckDuckGoAli AloNo ratings yet

- Sexism & Science - Evelyn ReedDocument242 pagesSexism & Science - Evelyn ReedKaveh Ahangarzadeh100% (1)

- John Warner 7Document6 pagesJohn Warner 7cesarNo ratings yet

- Apocalyptic Vision and Modernism's Dismantling of Scientific Discourse Lugones's YzurDocument13 pagesApocalyptic Vision and Modernism's Dismantling of Scientific Discourse Lugones's YzurocelotepecariNo ratings yet

- Christians en Language EvolutionDocument8 pagesChristians en Language EvolutionrolhandNo ratings yet