Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Maximum Price (AS Economics)

Maximum Price (AS Economics)

Uploaded by

Muhammad ButtOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Maximum Price (AS Economics)

Maximum Price (AS Economics)

Uploaded by

Muhammad ButtCopyright:

Available Formats

Maximum Price

The maximum price is the greatest legal price a seller is allowed to charge for its products. It is sometimes also referred to as price ceiling. As

explained in the theory, the price can fall below this level but cannot rise otherwise the government regulation/law will be violated. The government

uses a price ceiling at times when the equilibrium price set by the invisible hand (market forces of demand and supply) for necessities are unfairly high

and unaffordable for poor people like rice, lentils, wheat, sugar, etc. Other examples include oil, natural gas, and rental housing whose prices need to

be maintained at an acceptable level for ensuring consumers' welfare.

In the case where the Maximum price (MP) is set above the equilibrium price, it will have no effect as the previous equilibrium remains attainable. If,

however, MP is set below the market-clearing price, the price will decrease and is said to be effective in economic terms. The effects of the maximum

price on wheat are illustrated by the following graph;

As shown above, the equilibrium price of wheat is at p, and the quantity traded is Q initially at point B. The government believes that its price should be

decreased for societal welfare so it imposes the maximum price (MP). At this lower price, those firms with a higher average cost will supply less at Q1

at point C. Simultaneously, the fall in its price will also encourage price-insensitive customers to buy more kilos of wheat; a total of quantity Q2 as seen

on the demand curve. This mismatch between what firms want to supply and what quantity of good buyers want to purchase will cause demand to

exceed supply. Hence, the shortage of Q2-Q1 develops.

As a consequence of fixing the maximum price, some people will gain and some people will lose. As the graph tells, the businesses will lose because

they will receive lower revenue per unit from the sale of wheat. This, in turn, could provoke some firms to exit the industry thinking that the government

intervention has made its trading less or not profitable at the current established market price. On the other hand, the consumers who can purchase

wheat at a decreased price will become better off, however, those who have been rationed out and cannot buy it due to the shortage are worse off.

With the enforcement of maximum price triggering an acute shortage of products in the market, some other method of location might be used. For

instance, the small shops or supermarkets can sell their available supplies of wheat on a first come first serve basis. Long queues of vehicles at

these places will develop and the allocation will be based on luck. Alternatively, sellers may pretend that they don't have it and try to sell the remaining

wheat to their relatives, friends, etc first.

Here, the government might also intervene by introducing a system of rationing to counter the unfair distribution of goods and to make sure that the

needy people are not deprived of it. To do this, the state authorities will put a limit on the amount of wheat each person is allowed to purchase. They

can also ration the goods by giving out coupons that are sufficient to buy some of the available supplies. Other ways include distributing wheat

according to the socio-economic group, the number of children a family has, etc.

It must also be borne in mind that such market conditions usually encourage the setup of a black market (goods are sold in violation of price and

rationing laws). Its establishment depends upon the willingness of a few people to risk heavy penalties by running a black market and a large number

of customers ready to purchase the product illegally. To make this market functional, the black marketers will buy Q1 of wheat at a controlled price. It

will be then sold at a higher price at point A for earning supernormal profits.

You might also like

- Test Bank For Foundations and Adult Health Nursing 7th Edition by Kim Cooper Kelly GosnellDocument18 pagesTest Bank For Foundations and Adult Health Nursing 7th Edition by Kim Cooper Kelly Gosnellgomeerrorist.g9vfq698% (51)

- IB Economics SL Answered QuestionsDocument14 pagesIB Economics SL Answered QuestionsAlee Risco100% (1)

- Case StudyDocument4 pagesCase StudyMonina Amano100% (3)

- Sept Monthly Test EcoDocument3 pagesSept Monthly Test EcoWai HponeNo ratings yet

- Price Ceiling and FloorDocument2 pagesPrice Ceiling and Floorraquel mNo ratings yet

- Paper 1 Micro Economics Extended Response PaperDocument11 pagesPaper 1 Micro Economics Extended Response Paperanonymous100% (1)

- WEEK1-3 PriceCeilingAndFloors ElasticityDocument9 pagesWEEK1-3 PriceCeilingAndFloors ElasticityNguyễn Trần Anh VũNo ratings yet

- Government InterventionDocument8 pagesGovernment Interventionjamilhasan8No ratings yet

- Fundamental Analysis of CommoditiesDocument8 pagesFundamental Analysis of CommoditiesShraddha BhatNo ratings yet

- Topic:: Roll No. 32 Roll No. 34 Roll No. 35 Roll No. 38 Roll No. 39 Roll No. 43Document10 pagesTopic:: Roll No. 32 Roll No. 34 Roll No. 35 Roll No. 38 Roll No. 39 Roll No. 43Afifa NaikNo ratings yet

- BS1197 - 289862Document9 pagesBS1197 - 289862Cameron MoraisNo ratings yet

- SwebeDocument3 pagesSwebeJuma SimbanoNo ratings yet

- Summary MacroDocument64 pagesSummary Macrojayesh.guptaNo ratings yet

- Evaluate Why Governments Intervene in Market OutcomesDocument3 pagesEvaluate Why Governments Intervene in Market OutcomesBenNo ratings yet

- BS1197 - 289862Document9 pagesBS1197 - 289862Cameron MoraisNo ratings yet

- BS1197 - 289862 PDFDocument9 pagesBS1197 - 289862 PDFCameron MoraisNo ratings yet

- Applied Economics 1st-QRTR PPT 4.1Document19 pagesApplied Economics 1st-QRTR PPT 4.1Agnes RamoNo ratings yet

- Module 3 - Price Internaction of Demand and SupplyDocument3 pagesModule 3 - Price Internaction of Demand and SupplyjessafesalazarNo ratings yet

- ECONOMICS RevisionDocument66 pagesECONOMICS RevisionZeebaNo ratings yet

- A Price Ceiling Occurs When The Government Puts A Legal Limit On How High The Price of A Product Can Be. It Is Also Known As Maximum PriceDocument4 pagesA Price Ceiling Occurs When The Government Puts A Legal Limit On How High The Price of A Product Can Be. It Is Also Known As Maximum Pricenutsat70No ratings yet

- Econ Assignment 1Document7 pagesEcon Assignment 1IsuriNo ratings yet

- Give An Example of A Government-Created Monopoly. Is Creating This Monopoly Necessarily Bad Public Policy? ExplainDocument8 pagesGive An Example of A Government-Created Monopoly. Is Creating This Monopoly Necessarily Bad Public Policy? ExplainMasri Abdul Lasi100% (1)

- Case-1: People Respond To Incentives. It Is Important, Therefore, That These Have The Desired EffectDocument13 pagesCase-1: People Respond To Incentives. It Is Important, Therefore, That These Have The Desired EffectHarikrushan DholariyaNo ratings yet

- Bundle of EconomicsDocument217 pagesBundle of EconomicsDanny AgiruNo ratings yet

- Price Controls: Econ 360-002 Sonia Parsa Sparsa1@gmu - Edu G00509808 Word Count: 1540Document11 pagesPrice Controls: Econ 360-002 Sonia Parsa Sparsa1@gmu - Edu G00509808 Word Count: 1540Amir SaiedehNo ratings yet

- The Implications of Market Pricing Report Week 4Document4 pagesThe Implications of Market Pricing Report Week 4Ex PertzNo ratings yet

- How Is The Government Going To Control PricesDocument4 pagesHow Is The Government Going To Control PricesFakhrulrazi IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Price FloorDocument6 pagesPrice FloorUgly DucklingNo ratings yet

- Ceiling and Floor PricesDocument2 pagesCeiling and Floor PricesLagopNo ratings yet

- Price MechanismDocument2 pagesPrice MechanismdavidbohNo ratings yet

- QUESTION: Explain How Elasticity of Demand Concept May Be Used by Government andDocument5 pagesQUESTION: Explain How Elasticity of Demand Concept May Be Used by Government andChitepo Itayi StephenNo ratings yet

- Chapter 13Document9 pagesChapter 13Swastik MaheshwaryNo ratings yet

- Importance of Ed in Managerial Decision MakingDocument10 pagesImportance of Ed in Managerial Decision MakingVijay Singh Kumar Vijay100% (1)

- Vi Mô True False v2Document8 pagesVi Mô True False v2minhhieu034No ratings yet

- Lesson 13 - Econ 2 (Abegail Blanco Mm2-I)Document14 pagesLesson 13 - Econ 2 (Abegail Blanco Mm2-I)Abegail BlancoNo ratings yet

- Econs HWDocument2 pagesEcons HWngkhoinguyen3006No ratings yet

- Complementary GoodsDocument7 pagesComplementary GoodsLiaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Economics Lecture 3Document1 pageIntroduction To Economics Lecture 3Carine TeeNo ratings yet

- Question: Discuss The Causes of Market Failure and How The Government Can Intervene To Correct Market Failure?Document4 pagesQuestion: Discuss The Causes of Market Failure and How The Government Can Intervene To Correct Market Failure?Dafrosa HonorNo ratings yet

- Econ 8 Marker CWDocument1 pageEcon 8 Marker CWinaayaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4Document19 pagesChapter 4syafikaabdullahNo ratings yet

- Edexcel Economics Unit 1 Topic 5.3 Wage Rates Complete AS-level Series NotesDocument6 pagesEdexcel Economics Unit 1 Topic 5.3 Wage Rates Complete AS-level Series NotesShahab HasanNo ratings yet

- Edexcel Economics Unit 1 Topic 7.2 Goverment Faliure Complete AS-level Series NotesDocument4 pagesEdexcel Economics Unit 1 Topic 7.2 Goverment Faliure Complete AS-level Series NotesShahab HasanNo ratings yet

- Price ActDocument5 pagesPrice ActJohny TumaliuanNo ratings yet

- Applied Economics READING WEEK 2Document3 pagesApplied Economics READING WEEK 2jeanaguilos2023No ratings yet

- What Does Invisible Hand of The Marketplace DoDocument5 pagesWhat Does Invisible Hand of The Marketplace DoSadia RahmanNo ratings yet

- Governments sometimes fix maximum prices on goods for different reasonsDocument1 pageGovernments sometimes fix maximum prices on goods for different reasonsagarwalshayna20No ratings yet

- Firm Competition and Market Structure: Mark Lemuel G. PardoDocument55 pagesFirm Competition and Market Structure: Mark Lemuel G. PardoCham PiNo ratings yet

- C) The Effects of Government InterventionDocument4 pagesC) The Effects of Government InterventionjaysambakerNo ratings yet

- Price Controls Distort Economic ActivityDocument2 pagesPrice Controls Distort Economic ActivityFlakito UriNo ratings yet

- Assignment 1 Policy and GovernanceDocument5 pagesAssignment 1 Policy and Governance아사드아바스/학생/산업보안거버넌스 정책학No ratings yet

- Post MidDocument140 pagesPost MidAneeb Ur RehmanNo ratings yet

- Price Determination & Simple ApplicationsDocument4 pagesPrice Determination & Simple ApplicationsnaiNo ratings yet

- A) Maximum and Minimum PricesDocument4 pagesA) Maximum and Minimum PricesNicole MpehlaNo ratings yet

- A) Maximum and Minimum PricesDocument4 pagesA) Maximum and Minimum PricesHarinNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 FIN 306 - FinalDocument36 pagesChapter 2 FIN 306 - FinalAbid vhiNo ratings yet

- Mixed Economic SystemDocument26 pagesMixed Economic SystemFazra FarookNo ratings yet

- The Law of SupplyDocument14 pagesThe Law of SupplyHeron LacanlaleNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 - The Market SettingDocument18 pagesChapter 3 - The Market SettingJeannie Lyn Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Soci PTDocument8 pagesSoci PTquentutraNo ratings yet

- D) Government Failure in Microeconomic InterventionDocument4 pagesD) Government Failure in Microeconomic InterventionRACSO elimuNo ratings yet

- About sugar buying for jobbers: How you can lessen business risks by trading in refined sugar futuresFrom EverandAbout sugar buying for jobbers: How you can lessen business risks by trading in refined sugar futuresNo ratings yet

- Gmpanx15 enDocument31 pagesGmpanx15 enDarlenis RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Imb405 PDF EngDocument9 pagesImb405 PDF EngDiana AlzatNo ratings yet

- Havells Project ShafeeqDocument37 pagesHavells Project ShafeeqnoufaNo ratings yet

- Final Exam With AnswerDocument8 pagesFinal Exam With Answerg409863No ratings yet

- Interim Order in The Matter of Togo Retail Marketing LimitedDocument16 pagesInterim Order in The Matter of Togo Retail Marketing LimitedShyam SunderNo ratings yet

- Distribution Channel of NokiaDocument13 pagesDistribution Channel of Nokiavandanamary50% (4)

- Aarav AssociatesDocument1 pageAarav AssociatesKrishna SinghNo ratings yet

- Accounting 1Document11 pagesAccounting 1Gniese Stephanie Gallema AlsayNo ratings yet

- Pba4805 Exam Answer SheetDocument9 pagesPba4805 Exam Answer SheetPhindile HNo ratings yet

- India Skills StoryDocument26 pagesIndia Skills Storyapi-288608374No ratings yet

- Types of DebenturesDocument3 pagesTypes of DebenturesMadhumitaSinghNo ratings yet

- Information Technology For Management Digital 10Th Full ChapterDocument41 pagesInformation Technology For Management Digital 10Th Full Chapterarnold.kluge705100% (26)

- Understanding The Law of Supply and DemandDocument2 pagesUnderstanding The Law of Supply and DemandTommyYapNo ratings yet

- Chapter 13 Commercialization: Test Marketing & Launching The New Product/ Chapter 14 Managing GrowthDocument3 pagesChapter 13 Commercialization: Test Marketing & Launching The New Product/ Chapter 14 Managing GrowthMaria KristineNo ratings yet

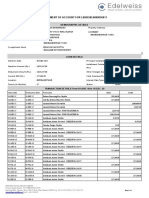

- 16 StatementofAccount LBHBSBL0000036011Document4 pages16 StatementofAccount LBHBSBL0000036011girija mohapatraNo ratings yet

- KGIC For Consolidation - Deck Kompas GramediaDocument31 pagesKGIC For Consolidation - Deck Kompas GramediarrifmilleniaNo ratings yet

- Manual On CAS For PACSDocument6 pagesManual On CAS For PACSManohara PrakashNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6 Understanding Work TeamsDocument15 pagesChapter 6 Understanding Work Teamsmuoilep1905No ratings yet

- Summer Internship Project ON A Study On Consumer Perception About Insurance CompanyDocument13 pagesSummer Internship Project ON A Study On Consumer Perception About Insurance CompanySHARMA TECHNo ratings yet

- Afar Partnerships Ms. Ellery D. de Leon: True or FalseDocument6 pagesAfar Partnerships Ms. Ellery D. de Leon: True or FalsePat DrezaNo ratings yet

- CBDT - E-Filing - ITR 3 - Validation Rules - V 1.0Document61 pagesCBDT - E-Filing - ITR 3 - Validation Rules - V 1.09o6.atharvamNo ratings yet

- Classified2019 10 1512343Document3 pagesClassified2019 10 1512343Safeer ChembanNo ratings yet

- WembleyDocument11 pagesWembleysyedamiriqbalNo ratings yet

- DMG Small CapsDocument9 pagesDMG Small Capscentaurus553587No ratings yet

- PediasureDocument4 pagesPediasureSiva Krishna Reddy NallamilliNo ratings yet

- POSTER PRESENTATION ON DataDocument1 pagePOSTER PRESENTATION ON DataNazmus SakibNo ratings yet

- Taguig City University: College of Business ManagementDocument4 pagesTaguig City University: College of Business ManagementAj LontocNo ratings yet

- CK Healthcare Solutions: Statement of WorkDocument2 pagesCK Healthcare Solutions: Statement of WorkBB StudioNo ratings yet