Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Bandura, A. Perceived Self-Efficacy and Personal Agency

Bandura, A. Perceived Self-Efficacy and Personal Agency

Uploaded by

Anabel LeeCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Schaum's Outline of Probability, Random Variables, and Random Processes, 3/EFrom EverandSchaum's Outline of Probability, Random Variables, and Random Processes, 3/ERating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (3)

- Kuratko South Asian Perspective - EntrepreneshipKuratko - Ch02Document17 pagesKuratko South Asian Perspective - EntrepreneshipKuratko - Ch02Rakshitha RNo ratings yet

- Hitchcock, Feminism, and The Patriarchal Unconscious: Tania ModleskiDocument12 pagesHitchcock, Feminism, and The Patriarchal Unconscious: Tania ModleskiAnabel LeeNo ratings yet

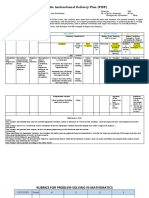

- Flexible Instructional Delivery Plan (FIDP) : What To Teach?Document3 pagesFlexible Instructional Delivery Plan (FIDP) : What To Teach?Arniel LlagasNo ratings yet

- ST ND: The Learners Demonstrat Ean Understand Ing Of: The Learners Shall Be Able To: The Learners: The LearnersDocument9 pagesST ND: The Learners Demonstrat Ean Understand Ing Of: The Learners Shall Be Able To: The Learners: The Learnersaurora pioneers memorial collegeNo ratings yet

- Journal of Applied Psychology Volume 79 Issue 3 1994 (Doi 10.1037/0021-9010.79.3.364) Lee, Cynthia Bobko, Philip - Self-Efficacy Beliefs - Comparison of Five Measures. PDFDocument6 pagesJournal of Applied Psychology Volume 79 Issue 3 1994 (Doi 10.1037/0021-9010.79.3.364) Lee, Cynthia Bobko, Philip - Self-Efficacy Beliefs - Comparison of Five Measures. PDFAjeng Tita NawangsariNo ratings yet

- Cspel 5 NarrativeDocument5 pagesCspel 5 Narrativeapi-377039370No ratings yet

- ORAL COMMUNICATION Q1 W6 Mod6 Features of Effective CommunicationDocument11 pagesORAL COMMUNICATION Q1 W6 Mod6 Features of Effective CommunicationGabriel Cabansag0% (1)

- Schoolwide BudgetDocument8 pagesSchoolwide Budgetapi-490976435No ratings yet

- 1 Perdeived Self-Efficacy in The Exercise of Personal AgencyDocument31 pages1 Perdeived Self-Efficacy in The Exercise of Personal AgencyFrance ParisNo ratings yet

- External Validity External Validity: High in Case of Field StudiesDocument39 pagesExternal Validity External Validity: High in Case of Field StudiesEmaanNo ratings yet

- Unit - Ii: Experimental DesignDocument17 pagesUnit - Ii: Experimental DesignsujianushNo ratings yet

- To Find The Motivation Level in The Organization.: Presented To: Presented byDocument30 pagesTo Find The Motivation Level in The Organization.: Presented To: Presented byRanjeeta BonalNo ratings yet

- The Research Process Part 2 CHAPTER # 4 (Page#85) : Theoretical Framework & Hypothesis DevelopmentDocument27 pagesThe Research Process Part 2 CHAPTER # 4 (Page#85) : Theoretical Framework & Hypothesis DevelopmentAb EdNo ratings yet

- Lecture 5Document32 pagesLecture 5Emeraldo Sabit Jr.No ratings yet

- Flexible Instruction Delivery Plan (FIDP) : What To Teach?Document3 pagesFlexible Instruction Delivery Plan (FIDP) : What To Teach?Nelson MaraguinotNo ratings yet

- LDM Course 2 (Module 2)Document6 pagesLDM Course 2 (Module 2)LEONARDO BAÑAGANo ratings yet

- Curriculum Map in Science 10 4th QuarterDocument13 pagesCurriculum Map in Science 10 4th QuarterLegend DaryNo ratings yet

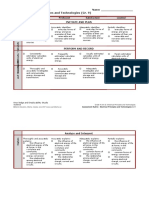

- Invasive Species RubricDocument1 pageInvasive Species Rubricapi-463570013No ratings yet

- Retrieve EmotionDocument18 pagesRetrieve Emotiondomenica.scavoneNo ratings yet

- Integrative Assessment: Master Teacher Grade Level ChairmanDocument6 pagesIntegrative Assessment: Master Teacher Grade Level Chairmanmarco medurandaNo ratings yet

- The Research Process Part 2 Chapter # 5: Theoretical Framework & Hypothesis DevelopmentDocument30 pagesThe Research Process Part 2 Chapter # 5: Theoretical Framework & Hypothesis DevelopmentIrfan ShinwariNo ratings yet

- Costs of A Predictable Switch Between Simple Cognitive TasksDocument25 pagesCosts of A Predictable Switch Between Simple Cognitive TasksFrancisco Ahumada MéndezNo ratings yet

- ATG-MET11-L1-Correlation AnalysisDocument33 pagesATG-MET11-L1-Correlation AnalysisMeljoy TenorioNo ratings yet

- Activity 5 Interview With Older AdultDocument2 pagesActivity 5 Interview With Older AdultDianneNo ratings yet

- 7787 MotivationDocument24 pages7787 Motivationtanmoy2No ratings yet

- Collaborative Learning Task - Product-Oriented Performance-Based AssessmentDocument2 pagesCollaborative Learning Task - Product-Oriented Performance-Based AssessmentchariesseNo ratings yet

- PLANES DE CLASES CCNN 5to. I Parcial 2021Document7 pagesPLANES DE CLASES CCNN 5to. I Parcial 2021Cinthia NoelyaNo ratings yet

- Qtr2 W8 DLL Science7Document3 pagesQtr2 W8 DLL Science7Charito De VillaNo ratings yet

- The Age of Surveillance Capitalism TextDocument7 pagesThe Age of Surveillance Capitalism TextwadnermanNo ratings yet

- Intro To Experiments - Ananya Singh 1065Document30 pagesIntro To Experiments - Ananya Singh 1065IT'S ANo ratings yet

- Dele Concept Ouestionnalre Objechive ÎndivitualDocument10 pagesDele Concept Ouestionnalre Objechive ÎndivitualPriaNo ratings yet

- Principles of High Quality AssessmentDocument46 pagesPrinciples of High Quality AssessmentBimbim WazzapNo ratings yet

- Experimental Research DesignDocument39 pagesExperimental Research DesignMunawar BilalNo ratings yet

- Child Development ReaderDocument65 pagesChild Development ReaderHimanshu RanjanNo ratings yet

- Or CF Sci gr09 Ud 05 AssessDocument3 pagesOr CF Sci gr09 Ud 05 Assessapi-253059746No ratings yet

- Niña Lorraine Herrera - FIDP TemplateDocument3 pagesNiña Lorraine Herrera - FIDP TemplateLorin XDNo ratings yet

- Research MethodsDocument14 pagesResearch MethodsNgoc Mai LeNo ratings yet

- Additional Reference VariableDocument8 pagesAdditional Reference VariablejackblackNo ratings yet

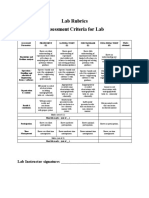

- Lab Rubrics Assessment Criteria For LabDocument8 pagesLab Rubrics Assessment Criteria For LabsamiNo ratings yet

- WORKSHEET 3 - Target SettingDocument5 pagesWORKSHEET 3 - Target SettingBitoy AlburanNo ratings yet

- RM Module 4 Part 2Document17 pagesRM Module 4 Part 2vkNo ratings yet

- Experimental Psychology PSY 433: Experiments - DesignsDocument22 pagesExperimental Psychology PSY 433: Experiments - DesignsFakiha8KhanNo ratings yet

- 4 - Teacher Resource 9.4 - Final Model RubricDocument2 pages4 - Teacher Resource 9.4 - Final Model RubricDefault AccountNo ratings yet

- Qtr2 W5 DLL Science7Document3 pagesQtr2 W5 DLL Science7Charito De VillaNo ratings yet

- Metodologi Penelitian: Prof. Dr. H. UJIANTO, MSDocument11 pagesMetodologi Penelitian: Prof. Dr. H. UJIANTO, MSRiski Arek DeathMetal SbyNo ratings yet

- Lesson 12 - Revision - Research Methods BookletDocument25 pagesLesson 12 - Revision - Research Methods BookletPranav PrasadNo ratings yet

- 02w MariaDocument2 pages02w Mariaapi-531019666No ratings yet

- Presentation On The 6 Lenses StrategyDocument15 pagesPresentation On The 6 Lenses StrategyLana Jelenjev100% (1)

- Assignment 1Document2 pagesAssignment 1Rida Asim AnwarNo ratings yet

- 5 6115923031664625580 PDFDocument3 pages5 6115923031664625580 PDFNur AthirahNo ratings yet

- BRI DGI NG THE GAP Between ART AND AGI NGDocument1 pageBRI DGI NG THE GAP Between ART AND AGI NGPriyanka KalmaniNo ratings yet

- Ejemplos 2 Masonetal.2021Document8 pagesEjemplos 2 Masonetal.2021José A. AristizabalNo ratings yet

- Image MGMTDocument18 pagesImage MGMTPoojaNo ratings yet

- 2014 C EH RuffaldiDocument9 pages2014 C EH Ruffaldijeraldjacob8aNo ratings yet

- AP Psychology Cram Unit 1 - Scientific Foundations of PsychologyDocument23 pagesAP Psychology Cram Unit 1 - Scientific Foundations of PsychologyZiyue (Sarah) YuanNo ratings yet

- Flexible Instructional Delivery Plan (FIDP) : Why Teach?Document31 pagesFlexible Instructional Delivery Plan (FIDP) : Why Teach?123 456No ratings yet

- International Council of Ophthalmology's Ophthalmology Surgical Competency Assessment Rubric (ICO-OSCAR)Document7 pagesInternational Council of Ophthalmology's Ophthalmology Surgical Competency Assessment Rubric (ICO-OSCAR)Jose Antonio Fuentes VegaNo ratings yet

- 10 Nov.4 8Document2 pages10 Nov.4 8Deo TabiosNo ratings yet

- Exp 7Document13 pagesExp 7Jhiro MartinezNo ratings yet

- Lab 4Document7 pagesLab 4jobertacunaNo ratings yet

- Handouts 1Document4 pagesHandouts 1Ken DumpNo ratings yet

- Exp Psych Midterm RevDocument4 pagesExp Psych Midterm RevNathalie ReyesNo ratings yet

- Practice Makes Perfect Latin Verb Tenses, 2nd EditionFrom EverandPractice Makes Perfect Latin Verb Tenses, 2nd EditionRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- Passive Addiction or Why We Hate Work: An Investigation of Problems in Organizational CommunicationFrom EverandPassive Addiction or Why We Hate Work: An Investigation of Problems in Organizational CommunicationNo ratings yet

- The Commons: Infrastructures For Troubling Times : Lauren BerlantDocument27 pagesThe Commons: Infrastructures For Troubling Times : Lauren BerlantAntti WahlNo ratings yet

- 0 Suner On TurkishnessDocument37 pages0 Suner On TurkishnessAnabel LeeNo ratings yet

- 0 Berghahn On Films of AkinDocument18 pages0 Berghahn On Films of AkinAnabel LeeNo ratings yet

- 0 Review On SunerDocument5 pages0 Review On SunerAnabel LeeNo ratings yet

- Bandura, A. Personal and Collective EfficacyDocument21 pagesBandura, A. Personal and Collective EfficacyAnabel LeeNo ratings yet

- History, Textuality, Nation: Kracauer, Burch and Some Problems in The Study of National CinemasDocument13 pagesHistory, Textuality, Nation: Kracauer, Burch and Some Problems in The Study of National CinemasAnabel LeeNo ratings yet

- University of Californis Residence PolicyDocument40 pagesUniversity of Californis Residence PolicyAnabel LeeNo ratings yet

- Neoliberalism Is A Serial KillerDocument43 pagesNeoliberalism Is A Serial KillerAnabel LeeNo ratings yet

- The Chronotope and The Study of Literary Adaptation: The Case of Robinson CrusoeDocument17 pagesThe Chronotope and The Study of Literary Adaptation: The Case of Robinson CrusoeAnabel LeeNo ratings yet

- Hamid Naficy Phobic Spaces and Liminal Panics IndepeDocument12 pagesHamid Naficy Phobic Spaces and Liminal Panics IndepeAnabel LeeNo ratings yet

- Ethics Lesson 2Document10 pagesEthics Lesson 2Vanessa Ambroce100% (1)

- TTL 2Document4 pagesTTL 2Christian Surio RamosNo ratings yet

- Lecture 6 Knowing How and Who Teams and GroupsDocument11 pagesLecture 6 Knowing How and Who Teams and GroupsCaleb LeongNo ratings yet

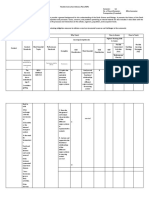

- SF9 With Modality - Grade 4-6Document27 pagesSF9 With Modality - Grade 4-6Kevz TawataoNo ratings yet

- Policy Chap 8Document8 pagesPolicy Chap 8matten yahyaNo ratings yet

- Sample Weekly Home Learning Plans - Q2W5Document14 pagesSample Weekly Home Learning Plans - Q2W5Abegail PanangNo ratings yet

- Lesson Introduction To Oral Communication: Grade 11, First Semester, Q1-Wk 1Document11 pagesLesson Introduction To Oral Communication: Grade 11, First Semester, Q1-Wk 1Jennie KimNo ratings yet

- Career Resume - SampleDocument3 pagesCareer Resume - SampleAnit Jacob PhilipNo ratings yet

- Week18 - Marking Guide ERQ Digital TechnologiesDocument3 pagesWeek18 - Marking Guide ERQ Digital TechnologiesfatimaNo ratings yet

- Murder Weapon ProfileDocument10 pagesMurder Weapon ProfileDevi Anantha SetiawanNo ratings yet

- Lesson 4 The Self As A Cognitive ConstructDocument34 pagesLesson 4 The Self As A Cognitive ConstructHisoka - sama100% (1)

- The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People Free Summary by Stephen R. Covey Et AlDocument11 pagesThe 7 Habits of Highly Effective People Free Summary by Stephen R. Covey Et AlSaunak DeNo ratings yet

- Module 2 Quarter 2Document5 pagesModule 2 Quarter 2Iyomi Faye De LeonNo ratings yet

- Business Ethics Third QTR Module Week6Document7 pagesBusiness Ethics Third QTR Module Week6Alyssa SolidumNo ratings yet

- Training and Development Midterm Quiz 2Document4 pagesTraining and Development Midterm Quiz 2Santi SeguinNo ratings yet

- 1 - Hitory of Psychology - Saundra K. Ciccarelli - J. Noland White - Psychology-Pearson (2016)Document7 pages1 - Hitory of Psychology - Saundra K. Ciccarelli - J. Noland White - Psychology-Pearson (2016)Chester ChesterNo ratings yet

- Sociology of Crimes Review QuestionsDocument19 pagesSociology of Crimes Review QuestionsJvnRodz P GmlmNo ratings yet

- In This Second Tutorial Assignmen1Document2 pagesIn This Second Tutorial Assignmen1Ace Pebri ALaNo ratings yet

- Monolog OsDocument8 pagesMonolog OsOli OlivandersNo ratings yet

- A Narrative Report On Student Teaching Experiences at Rizal National High School Rizal, Nueva EcijaDocument42 pagesA Narrative Report On Student Teaching Experiences at Rizal National High School Rizal, Nueva EcijaJerick SubadNo ratings yet

- Module IV - Building Positive AttitudeDocument22 pagesModule IV - Building Positive AttitudeAditi KuteNo ratings yet

- Developmental Milestones Timeline - Dorie Isaac 3Document31 pagesDevelopmental Milestones Timeline - Dorie Isaac 3api-584647670No ratings yet

- 11 Facts About Bullying: It's A Harmful Behavior That Impacts 1 in 5 Students in The USDocument3 pages11 Facts About Bullying: It's A Harmful Behavior That Impacts 1 in 5 Students in The USvamosala lunaelyNo ratings yet

- Primary Schools in Japan: ST THDocument14 pagesPrimary Schools in Japan: ST THyoga aji sukmaNo ratings yet

- MT Module 2Document4 pagesMT Module 2KezNo ratings yet

- Fabiano (2018) Best Practices in School Mental Health For ADHDDocument20 pagesFabiano (2018) Best Practices in School Mental Health For ADHDМаріанна КрохмальнаNo ratings yet

Bandura, A. Perceived Self-Efficacy and Personal Agency

Bandura, A. Perceived Self-Efficacy and Personal Agency

Uploaded by

Anabel LeeOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Bandura, A. Perceived Self-Efficacy and Personal Agency

Bandura, A. Perceived Self-Efficacy and Personal Agency

Uploaded by

Anabel LeeCopyright:

Available Formats

PERCEIVED SELF-EFFICACY IN THE EXERCISE OF PERSONAL AGENCY

Author(s): Albert Bandura

Source: Revista Española de Pedagogía , septiembre - diciembre 1990, Vol. 48, No. 187

(septiembre - diciembre 1990), pp. 397-427

Published by: Universidad Internacional de La Rioja (UNIR)

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23764608

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Revista Española de

Pedagogía

This content downloaded from

131.179.158.26 on Sat, 27 Feb 2021 22:56:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

PERCEIVED SELF-EFFICACY IN THE EXERCISE

OF PERSONAL AGENCY (*)

by Albert Bandura

Stanford University

The recent years have witnesser a resurgenoe of interest in self

referent phenomena. One can point to several reasons why self pro

cessus have come to pervade the research in many areas of psychology.

Self-generated activities lie at the very heart of causal processes. They

not only gîve meaning and valence to most external influences, but they

function as important proximal déterminants of motivation and action.

People make causal contributions to their own psychosocial functioning

through mechanisms of personal agency. Among the mechanisms of

agency, none is more central or pervasive than people's beliefs about

their capabilities to exercise control over events that affect their lives.

Self-beliefs of efficacy influence how people feel, think, and act. The

présent article analyses the causal function of self-percept of efficacy

and the diverse processes through which they exent their effects.

Self-Efficacy causality

A central question in any theory of cognitive régulation of motivation

and action concerns the issue of causality. Do self-efficacy beliefs operate

as causal factors in human functioning? This issue has been investigated

by a variety of experimental stratégies. Each approach tests the dual

causal link in which instating conditions affect efficacy beliefs, and

(*) This article was presented as an invited address at the annnal meeting of

The British Psychological Society, St Andrews, Scotland, April 1989. Some sections

of this article contain revised and expanded material from my article entitled,

Human agency in social cognitive theory, American Psychologist.

revista «apañóla da pedagogía

año XLVIII, n.® 187; septiembre-diciembre 1990

This content downloaded from

131.179.158.26 on Sat, 27 Feb 2021 22:56:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

398 ALBERT BANDURA

efficacy beliefs, in turn, affect

efficacy is raised in probics from

lected low, moderate, or high level

riences or simply by modeling cop

red level of efficacy was attained

As shown in Figure 1, higher le

accompanied by higher perform

relationship is repliöated across dif

group and intrasubject compariso

self-efficacy was raised by maste

influencie. Microanalysis of effica

between perceived self-efficacy an

Another aprroach to the test of

level of ability but to vary perce

level. Collins (1982) selected chil

high or low mathematical efficacy

ability. They were then given dif

level of mathematical ability, child

cacious were quicker to discard f

(Figure 2). chose to rework more

accurately. Perceived self-efficac

dent effect on performance.

A third approach to causality is

of information to affect compet

U!

O 100 o 100

z

< <

5 90 5 90b

CL o:

O O

u. 80

CL

Ui

0

70 70 -

_I

D

u.

60 60 -

V)

<A

UJ

O 50 O 50 ■

Ü INTERGROUP INTRASUBJECT U INTERGROUP INTRASUBJECT

V) 40 40 r

-1_

_L_

£

LOW MEDIUM HIGH LOW MEDIUM HIGH LOW MEDIUM LOW MEDIUM

LEVEL OF PERCEIVED SELF-EFFICACY

Figure 1. — Mean

Mean performance

performance attainments

attainments as as aa function

function of

of differential

differentiallev

lev

perceived self-efficacy.

self-efficacy. The

The two

two left

left panels

panels présent

présent the

the relationship

relationshipfor

forper

pe

self-efficacy raised

raised by

by mastery

mastery expériences;

experiences; the

the two

two right

right panels

panelsprésents

présentstht

perceived self-efficacy

tionship for perceived self-efficacy raised

raised by

by vicarious

vicarious expériences.

experiences.The

Theinter

inte

panels show

show the

the performance

performance attainments

attainments of of groups

groups ofof subjects

subjectswhose

whoseself-pe

self-p

of efficacy were

were raised

raised to

to differential

differential levels;

levels; the

the intrasubject

intrasubject panels

panelsshow

showth t

formance attainments

attainments forfor the

the same

same subjects

subjects after

after their

their self-percepts

self-perceptsof ofeff

ef

were successively

successively raised

raised to

to différent

différent levels

levels (Bandura,

(Bandura, Reese

Reese &<&Adams,

Adams, 1982

19

rev. esp poa. XL.VÍII, 187, 1980

This content downloaded from

131.179.158.26 on Sat, 27 Feb 2021 22:56:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

PERCEIVED SELF-EFFICACY IN THE EXERCISE... 399

70 efficacy. The impact of the

altered perceived efficacy on

level of motivation is t h e n

60

measured. Studies of anchoring

influences show that arbitrary

^ 50 reference points from which

judgements are adjusted either

z

g

upward or down-ward can bias

►

3

40

the judgements because the

adjustments are usually insuffi

30 cient. Cervone and Peake (1966)

used arbitrary anchor values to

S

influence self-appraisals of effi

f* 20

cacy. Self-appraisals made from

SELF- EFFICACY

an arbitrary high starting point

10

HIGH

baised students' perceived self

-• low efficacy

LOW MEDIUM HIGH

ABILITY LEVEL

Figure 2. — Mean levels o1

of mathematical solutions achieved by students as a

function of

of mathematical

mathematical ability

abilityand

andperceived

perceivedmathematical

mathematicalself-efficacy.

self-efficacy.Plotted

Plotted

from

from data

data of

of Collins,

Collins, 1982

1982

30

UJ

u

£25

-

m

ct20 "

UJ

Q_

-

% 15

.

''

h

UL 10 '

o

-

-j

IS

> 5 •

UJ

-j vV.V

0

LOWNONO HIGH

LOW HIGH LÖWLOW'

' NONQ HIGH

HIGH

ANCHOR ANCHOR ANCHOR ANCHOR ANCHOR ANCHOR

Figure 3. —

— Mean

Mean changes

changes induced

induced in

in perceived

perceived self-efficacy

self-efficacyby

byanchoring

anchoringini

and the

and the corresponding

correspondingeffects

effectsononlevel

levelofof subséquent

subséquent persévérant

persévérant effort

effort (Ce

Peake, 1986)

rev. esp ped. XLVIII, 187, 1999

This content downloaded from

131.179.158.26 on Sat, 27 Feb 2021 22:56:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

400 ALBERT BANDURA

in the positive direction, whereas a

students' appraisals of their effi

points in a sequence of performa

efficacy appraisal (Peake & Cervon

(1989) biased seif-efficacy apprai

things about the task that migh

Dwelling on formidable aspects we

but focussing on doable aspects

In all of these experiments, the hig

the longer individuáis (persevere

before they quit. Mediational ana

fluences nor cognitive focus has an

self-efficacy is partialled out. Th

performance motivation is thus c

efficacy.

A number of experiments have been conducted in which self-efficacy

beliefs are altered by bogus feedback unrelated to one's actual perfor

mance. People partly judge tbeir capabilities through social comparison.

220

200

O

Ui

</>

o )80

z

UJ

Q:

h

S 160

</>

>

X

CL

140 SELF-EFFICACY

•—• HIGH

•—• LOW

COMPETITIVE TRIES

COMPETITIVE TRIES

Figure 4.

Figure 4.—Mean

— Meantevel

íevelof

ofphysical

physical stamina

stamina mobilised

mobilised in

in compétitive situat

compétitive situat

a function of illusorily instated high or low self-precepts of physical

physical efficacy

efficacy

berg, Goud & Jackson, 1979)

rev. esp. ped. XLVIII, 187. 1960

This content downloaded from

131.179.158.26 on Sat, 27 Feb 2021 22:56:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

PERCEIVED SELF-EFFICACY IN THE EXERCISE... 401

tow HIGH

LOW HIGH LOW

LOW HIGH

HIGH

SELF-EFFICACY INDUCTION

Figure 5. — Mean changes in perceived self-efficacy induced by arbitrary norm

comparison and the corresponding effects on level of subséquent persévéra

(Jacobs, Prentice-Dunn&&Rogers,

(Jacobs, Prentice-Dunn Rogers, 1984)

1984)

Using this type of induction procédure, Weinberg, Gould and J

(1979) showed that physical stamina in compétitive situations i

ted by perceived self-efficacy. They raised the self-efficacy beliefs

group by telling thesm that they lowered the self-efficacy beliefs of a

group by telling them that they were outperformed by their com

The higher the illusory beliefs of physical strength, the more

endurance subjects displayed during compétition on a new task

ring physical stamina (Figure 4). Failure in a subséquent comp

spurred those with a high sense of perceived self-efficacy to even

physical effort, whereas failure further impaired the perform

those whose perceived self-efficacy had been undermined. Self-be

physical efficacy illusorily heightened in females and illusorily w

in males obliterated large preexisting sex différences in physical st

Another variant of social self-appraisal —«bogus normative c

son— has also been used to raise or weaken beliefs of cogniti

efficacy. Individuais are led to believe that they performed at the

or lowest percentile ranks of the reference groqp, regardless

actual performance (Jacobs, Prentice-Dunn & Rogers, 1984). Pe

self-efficacy heightened by this mean produces stronger pers

effort (Figure 5). The regulatory role of self-belief of efficacy ins

unauthentic normative comparison is replicated in a markedly dif

rev. esp. pea. XLVIII, 187, 1980

This content downloaded from

131.179.158.26 on Sat, 27 Feb 2021 22:56:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

402 ALBERT BANDURA

domain of functioning, namely

the instated belief in one's capab

Still another approach to the véri

vening experimental design in w

tioning is applied, but in ways t

changes accompanying psychologic

if not more, from instilling belief

cular skills imparted. If people'

strengthened, they approach situa

use of the skills they have. Holr

1984), demonstrated with sufferer

of biofeedback training may stem

coping efficacy than from the

feedback sessions, they trained

beknownst to another group, th

were relaxing whenever they te

tensers of facial muscles, which

headaches. Regardless of whethe

musculator, bogus feedback that t

muscular tension instilled a stron

vent the occurrence of headache

higher their perceived self-effica

ced. The actual amount of change

ment was unrelated to the incid

These diverse causal tests conduc

induction, varied populations, a

provide supporting evidence tha

significantly to level of motivat

Evidence that divergent procédu

the explanatory and prédictive ge

The findings of the preceding

mean that arbitrary persuasory i

self-efficacy beliefs in the pursui

have special bearing on the issue o

are altered independently of a p

cannot be discounted as by-produ

that changes in self-beliefs of eff

actual social practice, personal

riences is the most powerful mea

of efficacy (Bandura, 1986, 1988

with knowledge, subskïlls and the

use one's skills effectively.

rev. esp. ped. XL.VIII, 187, 1990

This content downloaded from

131.179.158.26 on Sat, 27 Feb 2021 22:56:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

PERCEIVED SELF-EFFICACY IN THE EXERCISE... 403

Efficacy-Activated. processes

Self-efficacy beliefs regúlate human functioning through four majo

prooesses. They include cognitive, motivational, affective and sélecti

processes. Some of these efficacy-activated events are of interest in th

own right rather than merely intervening influencers of action. These

processes are analysed in some detail in the sections that follow.

A. Cognitive processes

Self-beliefs of efficacy affect thought patterns that can enhance or

undermine performance. These cognitive effects take various form

Much human behavior, being purposive, is regulated by forethough

embodying cognised goals. Personal goal setting is influenced by se

appraisal of capabilities. The stronger the perceived self-efficacy, t

higher the goals people set for themselves and the firmer their comm

ment to them (Bandura & Bood, 1989; Locke, Frederick, Lee & Bobk

1984; Taylor, Locke, Lee & Gist, 1984). Ohallenging goals raise the le

of motivation and performance attainments (Locke, Shaw, Saari & L

ham, 1981; Mento, Steel & Karren, 1987).

People's perceptions of their efficacy influences the types of ant

patory scénarios they construct and reitérate. Those who have a hi

sense of efficacy visualise success scénarios that provide positive guides

for performance. Those who judge themselves as inefficacious are mor

inclined to visualise failure scénarios whidh undermine performance by

dwelling on how things will go wrong. Numerous studies have show

that cognitive simulations in which individuáis visualise themselv

executing activities skilfully enhance subséquent performance (Bandura

1986; Corbin, 1972; Feltz & Landers, 1983; Kazdin, 1978). Perceived s

efficacy and cognitive simulation affect each other bidirectionally

high sense of efficacy fosters cognitive constructions of effective actio

and cognitive réitération of efficacious courses of action strengthe

self-percepts of efficacy (Bandura & Adams, 1977; Kazdin, 1979).

A major fuction of thought is to enable people to predict the occ

rence of events and to create the means for exercising control over th

that affect their daily lives. Many activities involve iriferential jud

ment about conditional relations between events. Discovery of such pr

dictive rules requhes effective cognitive processing of multidimension

information thät contains aimbiguities and uncertainties. The fact tha

the same predictor may contribute to différent effects and the sa

effect may have multiple predictors créâtes uncertainty as to what

likely to lead to what in probabilistic environments.

r*v. eap päd. XLVIII, 18?. 1980

This content downloaded from

131.179.158.26 on Sat, 27 Feb 2021 22:56:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

404 ALBERT BANDURA

In ferreting out prédictive rules pe

ting knowledge to generate hypot

test their judgements against the re

ber which notions they had tested

requires a strong sense of efficacy

of pressing situational demans an

important repercussions.

The powerful influence of self-eff

nitive processes is revealed in a pr

organisational decision-making (W

research on human decision-makin

static environments (Beach, Barne

garth, 1981). Judgements under such

cient basis for developing either

decision-making in dynamic natu

repeated judgements governed by

nisms.

The mechanisms and outcomes of organisational decision-making

do not lend themselves readly to experimental analysis in actual organi

sational settings. Advances in this complex field can be achieved by

experimental analyses of décision making in simulated organisational

environments. A simulated environment permits systematic variation of

theoretically relevant factors and precise assessment of their impact on

organisational performance and the psychological mechanisms through

which they achieved their effects.

In this research, executives managed a computer-simulated organi

sation in which they had to allocate resources and to learn and imple

ment managerial rules to achieve organisational levels of performance

that were difficult to fulfil. At periodic intervais we measured their

perceived self-efficacy, the goals they sought to achieve, the adequacy of

their analytic thinking for discovering managerial rules, and the level

of organisational performance they realised.

Social cognitive theory explains psychosocial functioning in terms

of triadic reciprocal causation (Bandura, 1986). In this model of reci

procal determinism, cognitive and other personal factors, behaviour,

and environmental events all operate as interacting déterminants that

influence each other bidirectionally. Each of the major interactants in

the triadic causal structure - cognitive, behavioural, and environmental

- functions as an important constituent in the dynamic simulated envi

ronment. The cognitive déterminant is indexed by self-beliefs of efficacy,

personal goal-setting, and quality of analytic thinking. The managerial

choices that are actually executed constitute the behavioural determi

rev. esp. ped. XLVIII, 187, 1990

This content downloaded from

131.179.158.26 on Sat, 27 Feb 2021 22:56:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

PERCEIVED SELF-EFFICACY IN THE EXERCISE... 405

nant. The properties of the organisational environm

challenge it prescribes, and its responsiveness to ma

tions represent the environmental déterminant. Ana

processes clarify how the interactional causal struc

changes over time.

The interactional causal structure was tested in co

experimentally varied organisational properties and b

can enhance or undermine the opération of self-regulat

One important beliefs system is concerned with the co

(M. Bandura & Dweck, 1988; Dweck & Elliott, 1983; Nicholls, 1984).

Some people regard ability as an acquirable skill that can be increased

by gaining knowledge and perfecting compétences. They adopt a lear

ning goal. They seek challenges that provide opportunities to expand

their knowledge and compétences. They regard errors as a natural part

of an acquisition process. One learns from mistakes. They judge their

capabilities more in terms of personal improvement than by comparison

against the achievement of others. For people who view ability as a

more or less fixed capacity, performance level is regarded as diagnostic

of inhérent cognitive capacities. Errors and déficient performances carry

high evaluative threat. Therefore, they prefer tasks that minimise errors

and permit ready display of intellectual proficiency at the expense of

expanding their knowlëdge and compétences. High efforts is also

threatening because it presumably reveáis low ability. The successes of

others belittle their own perceived ability.

We induced these différent conceptions of ability and then examined

their effects on the self-regulatory mechanisms governing the utilisation

of skills and performance accomplishments (Wood & Bandura, 1989a).

Managers who viewed decision-making ability as reflecting basic cogni

l 3

3 1

1

THIAU

TRIAL SLOCKS

BLOCAS

Figure

Figure 6.

6. —

— Chang

Chan

set

set for

for the

the organi

organ

stratégies,

stratégies, and

andaca

ductions

ductions orders

Orders u

trial

trial block

block compr

comp

rev. esp. ped. XLVIII, 1

This content downloaded from

131.179.158.26 on Sat, 27 Feb 2021 22:56:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

406 ALBERT BANDURA

tive aptitude were beset by incre

efficacy as they encountered p

and more erratic in their analyti

tional aspirations, and they ach

nisation they were managing. I

acquirable skill fostered a highl

Under this belief system, the ma

ceived managerial self-efficacy, t

ging organisational goals, and th

ways that aided discovery of o

a self-efficacious orientation paid

Another important belief system

information is cognitively proc

about the extent to which their

trollable. This aspect to the exe

system constraint, the opportu

cacy, and the ease of access to t

nisational simulation research

ceived controllability on the sel

making that can enhance or im

1989). People who managed the

tive set that organisations are no

their decision-making capabilit

were within easy reach (Figure 7

who operated under a cognitive

displayed a strong sense of ma

increasingly challenging goals an

120

I 01

' 6 115

I o

UJ

!£ no

i

s » | 105

100

Figure 7. — Changes in strength of perceived managerial self-efficacy, the perfor

mance goals set for the organization,

Organization, and

and level

level of

of organizational

organizational performance

performance for

for

managers who operated under a cognitive set that organisations are controllable or

different production Orders

difficult to control. Each trial block comprises six différent orders

(Banjdura

(Bandura && Wood, 1989)

rev. esp. ped. XLVIII, 187, 1990

This content downloaded from

131.179.158.26 on Sat, 27 Feb 2021 22:56:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

PERCEIVED SELF-EFFICACY IN THE EXERCISE... 407

f

//

•3«

■31134»

(.34) 3* {.Ml

»{.» 221*

AAST SELF*

SELF ANALYTIC

23l^|

KRFOMUNCt SELF.

SELF* 26

2» {421

ANALYTIC

ANALYTIC

211

2« ( S9l

S9>

L1

PERFORMANCE EFFICACY EFFIEFFICACY

CACY STRATEGIES performance

Pathh anaíysis

Figure 8. — Pat analysis of

of causal

causal structures.

structures. The

The initial

initial numbers on the paths

of influence are

are the

the significant

significant standardised

standardised path

path coefficients

coefficients (ps<05);

(ps<05);the

thenumbers

numbers

in parenthèses

parenthèses are

are the

the first-order

first-order corrélations.

corrélations. The

The network

networkof ofrelation

relationononthe

theteft

left

half of the figure

figure are

are for

for the

the initial

initial managerial

managerial efforts,

efforts, and

and those

those on

on the

theright

rightare

are

for later managerial

managerial efforts

efforts (Wood

(Wood &

& Bandura,

Bandura, 1988b)

1988b)

vering effective managerial rules. They exhibited high resiliency of self

efficacy even in the face of numerous difficulties. The divergent changes

in the self-regulatory factors are accompanied by large différences in

organisational attainments.

Path analyses confirm the postulated causal ordering of self-regulatory

déterminants. When initially faced with managing a complex unfamiliar

environment, people relied heavily on their past performance in judging

their efficacy and setting their personal goals. But as they began to

form a self-schema concerning their efficacy through further experience,

the performance system is powered more strongly and intricately by

self-perceptions of efficacy (Figure 8). iPerceived self-efficacy influences

performance both directly and through its strong effects on personal

goal setting and proficient analytic thinking. Personal goals, in turn,

enhance performance attainments through the médiation of analytic

stratégies.

B. Motivational processes

Self-beliefs of efficacy play a central role in the self-regulation of

motivation. Most human motivation is cognitively generated. In cogni

tive motivation, people motivate themselves and guide their action

anticipatorily through the exercise of forethoughts. They anticípate

likely outcome of prospective actions, they set goals for themselves and

plan courses of action designed to realise valued futures.

One can distinguish three différent forms of cognitive motivators

around which différent théories have been built. These include causal

attributions, outcome \expectancies, and cognised goals. The correspon

ding théories are attribution theory, expectancy-value theory, and goal

theory, respectively. Figure 9 summarises schematically these alternative

conceptions of cognitive motivation. Outcome and goal motivators

clearly operate through the anticipation mechanism. Causal reasons con

ceived retrospectively for prior attainments can also affect future actions

rev. esp. ped. XLVIII. 187, 1990)

This content downloaded from

131.179.158.26 on Sat, 27 Feb 2021 22:56:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

408 ALBERT BANDURA

anticipatorily by altering self-appra

task demands.

The self-efficacy mechanism of personal agency operates in all of

these variant forms of cognitive motivation. Causal attributions and self

efficacy appraisals involve bidirectional causation. Self-beliefs of efficacy

bias causal attribution (Cbllins, 1982; Silver, Mitidhell & Gist, 1989). The

relative weight given to information regarding adeptness, effort, task

complexity, and situational circumstances affects self-efficacy appraisal.

Causal analyses indícate that the effects of causal attributions on per

formance attainments are mediated through self-efficacy beliefs rather

than operate directly on performance (Relich, Debus & Walker, 1986;

Schunk & Cox, 1986; Schunk & Gun, 1986; Schunk & Rice, 1986). The

stronger the self-efficacy belief, the higher the subséquent performance

attainments.

In expectancy-value theory, strenght of motivation is governed jointly

by the expectation that particular actions will produce specified outco

mes and the value placed on those outcomes (Atkinson, 1964; Feather,

1982; Fishbein, 1967; Rotter, 1954), However, people act on their beliefs

about what they can do, as well 'as their beliefs about the likely outcomes

of various actions. The effects of outcome expectancies on performance

motivation are partly governed by self-beliefs of efficacy, There are many

activities which, if done well, guarantee valued outcomes, but they are

not pursued by people who doubt they can do what it takes to succeed

(Beck & Lund, 1981; Betz & Hackett, 1986). The predictiveness of expec

tancy-value theory can be enhanced by including the self-efficacy déter

minant (McCaul, O'Nei'll & Glasgow, 1988; Wheeler, 1983).

i— COGNIZED GOALS

Forethought j

Figure

Figure 9. —

9.Schematic

— Schematic

représentation

représentation

of conceptions ofofcognitive

conceptions

motivationof

based

cognitiv

on

oncognised

cognised

goals, goals,

outcome outcome

expectations expectations

and causal attributions

and causal attribu

The degree to which outcome expectations contribute independently

to performance motivation varies depending on how tightly contingen

cies between actions and outcomes are structured, either inherently or

socially, in a given domain of functioning. For many activities, outcomes

are determined by level of compétence, Henee, the types of outcomes

rev. esp. ped. XLVIli, 187, 1990

This content downloaded from

131.179.158.26 on Sat, 27 Feb 2021 22:56:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

PERCEIVED SELF-EFFICACY IN THE EXERCISE... 409

people anticípate dépend largely on how well they believe

to perform in given situations. In most social, intelle

pursuits, those who judge themselves highly efficac

favourable outcomes, whereas those who expect poor

themselves will conjure up negative outcomes. Thus

which outcomes are highly contingent on quality of p

judged efficacy accounts for most of the variance in ex

When variations in penceived self-efficacy are partialle

mes expected for given performances do not have mu

dent effect on behaviour (Barling & Abel, 1983; Barling

Godding & Glasgov, 1985; Lee, 1984a,b; Williams & W

Self-efficacy beliefs account for only part of the var

outcomes are not completely controlled by quality of p

occurs when extraneous factors also affect outcomes, or outcomes are

socially tied to a minimum level of performance so that some variations

in quality of performance above and below the standard do not produce

differential outcomes. And finally, expected outcomes are independent

of perceived self-efficacy when contingencies are discriminatively struc

tured so that on level of compétence can produce desired outcomes. This

occurs in pursuits that are rigidly segregated by sex, race, age or some

other factor. Under such circumstances, people in the disfavoured

group expect poor outcomes however efficacious they judge themselves

to be.

The capacity to exercise self-influence by personal challenge and eva

luative reaction to one's own attainments provides a major cognitive

mechanism of motivation and self-directedness (Bandura, 1988a).A large

body of evidence is consistent is showing that explicit challenging goals

enhance and sustain motivation ('Latham & Lee, 1986; Locke, Shaw,

Saari & Latham, 1981; Mento, Steel & Karren, 1987). Goals operate lar

gely through self-referent processes rather than regúlate motivation and

action directly. Motivation based on aspirational standards involves a

cognitive comparison process. By making self-satisfaction conditional

on matching adopted goals, people give direction to their actions and

create self incentives to persist in their efforts until their performances

match their goals. They seek self-satisfactions from fulfilling valued

goals and are prompted to intensify their effort by discontent with sub

standard performances.

Activation of self-evaluation processes through cognitive comparison

requires both comparative factors - a personal standard and knowledge

of one's performance level. Simply adopting a goal, without knowing

how one is doing, or knowing how one is doing in the absence of a goal,

has no lasting motivational impact (Bandura & Cervone, 1983; Becker,

1978; Strang, Lawrence & Fowler, 1978). But the combined influence of

rev. esp. ped. XLVIII, 187, 1999

This content downloaded from

131.179.158.26 on Sat, 27 Feb 2021 22:56:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

410 ALBERT BANDURA

goals with performance feedback

Cognitive motivation based on

types of self influences: affectiv

formance, perceived self-efficacy

personal standards in light of one

contributes to motivation in sev

self-beliefs of efficacy that peopl

how much effort to expend in th

in the face of difficultés (Bandu

tacles and failures, people who h

slacken their efforts or abort the

mediocre solutions, whereas tho

capabilities exert greater effort t

vone, 1983; Cervone & Peake, 19

1984; Peake & Cervone, 1989; We

perseverance usuallly pays off in

Perceived self-efficacy contribu

discrepancy between personal s

Cervone, 1986). The stronger the

can meet chailenging standars, th

efforts (Figure 10). Discontent o

attainments fall substantially o

125

100

50

HIGH EFF.

HIGH

EFF. LOW

HIGH DIS.

LOW EFF.

DIS. LOW

EFF.HIGH

LOW DIS.

HIGHEFF.

DIS.HIGH

EFF.LOW

HIGHDIS.

LOWEFF.

DIS.LOW

EFF.HIGH

LOWOIS.

HIGHS-G

DIS.HIGH

S-G

HIGHS-G

LOW

LOW

S-GS-G

S-GLOW

LOW

HIGH

HK3H

S-GS-G

EFF.EFF.

HIGH

HIGH

LOW

S-GS-G

LOW

LOW

EFF.EFF.

LOW

HIGH

S-GS-G

HIGH

I

EFF.EFF.

LOWLOW

EFF EFF

HIGH

HIGH S-G LOW S-G

SG LOW

Figure

Figure 10.—Mean

10. — Mean percent

percentchanges

changesin motivational

in motivational levellevel

by people who are

by people whohigh

are or

high or

low

low in

in the

the self-reactive

self-reactiveinfluences

influences identified

identified by by

hierachical

hierachical

régression

régressionanalyses

analyses

as as

the

the critical

criticalmotivators

motivatorsatat each

each

ofoffourfourlevels

levels

of preset

of preset

discrepancy

discrepancybetween

between

a cha a cha

llenging

ilenging standard

standardand andlevel

levelofofpeiiormance

performance attainment.

attainment.EFF signifies

EFF signifies

strengthstrength

of of

perceivedself-efficacy

perceived self-efficacy toto attain

attain a 50a 50% increase

% increase in effort;

in effort; DIS DIS

the the

levellevel of self-dissa

of self-dissa

tisfaction

tisfactionwith

withthethesame

same level

level

ofofattainment

attainment as inas the

in the

prior

prior

attemps;

attemps;

and S-G

andthe

S-G the

goals

goals people

peoplesetsetfor

forthemselves

themselves forforthethenext

next

attempt.

attempt.The The

second

second

set of

setgraphs

of graphs

at at

the —4

the —4 % % discrepancy

discrepancylevel

level summarise

summarise thethe results

results of the

of the régression

régression analysis

analysis perforperfor

med

med with

with perceived

perceivedself-efficacy

self-efficacy averaged

averagedover over

the the

30-70%

30-70%

goal goal

attainment

attainment

rangerange

(Bandura

(Bandura &£Cervone,

Cervone,1986)1986)

rev. esp. ped. XLVIII. 187, 1990

This content downloaded from

131.179.158.26 on Sat, 27 Feb 2021 22:56:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

PERCEIVED SELF-EFFICACY IN THE EXERCISE... 411

Standard. The more self-dissatified people are with substand

ments, the more they heighten their efforts. As people approa

pass the adopted standard, they set new goals for themselves th

as additional motivators. The higher the self-set goals, the mor

invested in the endeavour. Thus, notable attainments bring t

satisfaction, but people who are assured of their capabilties e

challenges as personal motivators for further accomplishme

together this set of self-reactive influences accounts for the m

of variation in motivation.

Many théories of motivation and self-regulation are founded on a

negative feedback control model. This type of System fonctions as a

motivator and regulator of action through a discrepancy réduction me

chanism. Perceived discrepancy between performance and a reference

standard motivâtes action to reduce the incongruity. Discrepancy réduc

tion clearly plays a central role in any System of selfiregulation. However,

in the negative feedback control System, if performance matches the

standard the person does nothing. Such a feedback control system

would produce circular action that leads nowhere.

Human selfmotivation relies on both discrepancy production and

discrepancy réduction (Bandura, 1988b). It requires proactive control

as well as reactive control. People initially motívate themselves through

proactive control by setting themselves valued challenging standards

that create a staite of disequilibrium and then mobilising their effort on

the basis of anticipatory estimation of what it would take to reach them.

As previously shown, after people attain the standard they have been

pursing, those who have a strong sense of efficacy generally set a higher

standard for themselves. The adoption of forther challenges créâtes new

motivating discrepaocies to be mastered. Similarly, surpassing a stan

dard is more likely to raise aspiration than to lower subséquent perfor

mance to conform to the surpassed standard. Self-motivation thus

involves a hierachical dual control process of disequilibrating discre

pancy production followed by equilibrating discrepancy réduction.

There is a growing body of evidence that huiman attainments and

positive well-being require an optimiste sense of personal efficacy (Ban

dura, 1986). This is because ordinary social realities are strewn with

difficultés. They are foll of irapediments, failures, adversities, setgacks,

frustrations, and inequities. People must have a robuts sense of personal

efficacy to sustain the persévérant effort needed to succeed. Self-doubts

can set in fast after some failures or reverses. The important matter is

not that difficultés arouse self-doubt, which is a natural immédiate

reaction, but the speed of recovery of perceived self-efficacy from diffi

cultés. Some people quickly recover their self-assurance; others lose

rev. esp. ped. XLVIH. 187, 198«

This content downloaded from

131.179.158.26 on Sat, 27 Feb 2021 22:56:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

412 ALBERT BANDURA

faith in their capabilities. Becau

competencies usually requires sust

and setbacks, it is resiliency of se

In his informative book, titled R

vivid testimony that the striki

achieVed eminense in their fields

and a firm belief in the worth of

belief system enabled them to ov

work.

Many of our literary classics b

tions. The novelist, Saroyan, acc

before he had his first literary

Dubliners, was rejected by 22 pu

submit poems to editors for abo

cepted. Now that is invincible s

rejected a manuscript by E.E. C

blished by his mother the dedicat

no thanks to... followed by the

offering.

Early rejection is the rule, rather than the exception, in other creative

endeavours. The Impressionist had to arrange their own art exhibitions

because their works were routinely rejected by the Paris Salon. A Paris

art dealer refused Picasso shelter when he asked if he could bring in his

paintings from out of the rain. Van Gogh sold only one painting during

his life. Rodin was rejected three times by the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. The

musical works of most renowned composers were initially greeted with

dérision. Stravinsky was run out of town by an enraged audience and

critics when he first served them the Rite of Spring. Many other compo

sers suffered the same fate, especially in the early phases of their career.

The brilliant architect, Frank Lloyd Wright, was one of the more widely

rejected architects during much of his career.

To turn to more familiar examples, Hollywood initially rejected the

incomparable Fred Astaire for being only «a balding, skinny actor who

can dance a little». Decca Records turned down a recording contract

with the Beatles with the non-prophetic évaluation, «We don't like their

sound. Groups of guitars are on their way óut». Whoever issued that

rejective pronouncement must eringe at each sight of a guitar.

It is not uncommon for authors of scientific classics to experience

repeated initial rejection of their work, often with hostile embellish

ments if it is too discordant whith what is in vogue at the time. For

example, John Garcia, who eventually won well-deserved récognition for

his fundamental psychological discoveries, was once told by a reviewer

rev. esp. ped. XLVIII, 187, 1990

This content downloaded from

131.179.158.26 on Sat, 27 Feb 2021 22:56:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

PERCEIVED SELF-EFFICACY IN THE EXERCISE... 413

of his oft rejected manuscripts that one is no more l

phenomenon he discovered than bird droppings in a

Verbal droppings of this type demand tenacious self-

the tortuosus search for new Muses. Seientists often re

techonologies that are ahead of their time. Because of t

given to most innovations, the time between concept

réalisation typicallly spans several decades.

The findings of laboratory investigations are in ac

records of human triumphs regarding the centrality of

effects of self-belief s of efficacy in human attainments.

sense of efficacy to override the numerous dissuadin

significant accomplishments.

It is widely believed that misjudgement breeds dysfun

gross misjudgements can get one into trouble. Bu

appraisals of capability that are not unduly dispara

possible cain be advantageous, whereas veridical judfie

limiting. When people err in their self-appraisal they te

their capabilities. This is a benefit rather than a cognit

eradicated. If self-efficacy beliefs always reflected only

do routinely, they would rarely fail but they would no

effort needed to surpass their ordinary performanc

evidence indicates that the successful, the innovative

nonanxious, the nondespondent, and the social refor

mistic view of their personal efficacy to exercise influ

that affect their lives (Bandura, 1986). If not unrealisti

such self-beliefs enhance and sustain the level of motiv

personal and social accomplishments.

C. Effective prdeesses

People's beliefs in their capabilities affect how m

dépressions they experience in threatening or taxing si

as their level of motivation. In social cognitive theor

perceived self-efficacy to exercise control over poten

events plays a central role in anxiety arousal. Thre

property of situational events. Nor does appraisal of

aversive happenings rely solely on reading external

safety. Rather, threat is a relational property conce

between perceived coping capabilities and potentially h

the environment. Therefore, to understand people's

nal threats and their affective reactions to them it is n

their judgements of their coping capabilities which, in

mine the subjective perilousness of environmental even

rev. esp. pod. XLVIII, 187, 1990

This content downloaded from

131.179.158.26 on Sat, 27 Feb 2021 22:56:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

414 ALBERT BANDURA

People who believe they can exe

do not conjure up appreihensive co

by them. But those who believe

experience high levels of anxiety

coping deficiencies and view dang

they distress themselves and cons

ing (Beck, Emery & Greenbergs,

enbaum, 1977; Sarson, 1975).

25

tu 20

z

13 -

UJ

œ

<

m

15

O

Z 10

<

X

o

LYMPHOCYTES TOTAL T CELLS HELPER T CELLS

J

_1 :

! _i I

25

8 - 40

40

uj 20

Z

-J

UJ 30

c/>

<

03

15

20

UJ

<3

| io 10

x

o

£

SUPPRESSOB

SUPPRESSOR T CELLS HELPER/SUPPRESSOR

helper/suppressor HLA-DR

HLA-DR

-L. _L _L_

EFFICACY

8 EFFICACY MAX

MAXIMAL B EFFICACY MAXIMAL B EFFICACY MAXIMAL

GROWTH EFFICACY GROWTH EFFICACY GROWTH EFFICACY

Figurb

Figurb 11.

11.—Changes

— Changesin

inimmune

immunefuction

faction experienced

expericnced as percent of

of baseline

baseline values

values

during exposure

exposure to

to the

the phobie

phobie stressor

stressorwhile

whileaquiring

aquiringperceived

perceivedcoping

copingself-efficacy

sélf-efftcacy

(Efficacy

(Efficacy Growth)

Growth) and

and after

after perceived

perceivedcoping

copingself-efficacy

self-efficacyhad

hadbeen

beendeveloped

developedtoto

the maximal

maximal level

level (Maximal

(Maximal Efficacy)

Efficacy)(Wiedensfeld,

(Wiedensfeld,0"Leary,

O'Leary,Bandura,

Bandura,Brown,

Brown,LeLe

vine && Raska,

Raska, 1989)

1989)

rev. osp. ped. XLVIII, 167. 1990

This content downloaded from

131.179.158.26 on Sat, 27 Feb 2021 22:56:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

PERCEIVED SELF-EFFICACY IN THE EXERCISE... 415

-,S7 / fERSOKAL \ -.53 f RtSK >. fPERCEIVED

^uu«iuBiuTY/~rv^^v bisk

.41 (.01)

NEGATIVE

ANXIETY

(.003) <W«»HTSy (.004)

Figure

Figure12.12.—— PathPath

analysis

analysis

of theof causal

thestructure.

causal structure.

The numbers The

on the

numbers

paths ofon the paths of

influence

influence areare

the the

significant

significant

standardised

standardised

path coefficients;

path coefficients;

the numbers intheparen

numbers in paren

thèses

thèsesare are

thethe

significance

significance

levels. levels.

The hatchTheline

hatch

to behavior

line torepresents

behavior différent

represents différent

activities

activtties pursued

pursuedoutside the home,

outside the the

home,solid the

line solid

represents

line avoided activities

represents be

avoided activities be

cause

causeofof concern

concernoverover

personal

personal

safety (Ozer

safety& Bandura,

(Ozer &1989)

Bandura, 1989)

That perceived coping efficacy opérâtes as a cognitive mediator of

anxiety and stress reactions has been tested by creating différent levels

of perceived self-efficacy and relating tihem at a microlevel to différent

manifestations of anxiety. People display little affective arousal while

coping with potential threats they regard with high efficacy. But as

they cope with threats for which they distrust their coping efficacy,

their stress mounts, their heart rate aocelerates, their blood pressure

rises, and they display increased catecholamine sécrétion (Bandura,

Reese & Adams, 1982; Bandura, Taylor, Williams, Mefford & Bardhas,

1985). After perceived efficacy is strengthened to the maximal level by

guide mastery, previously intimidating tasks no longer elicit differential

autonomie catecholaimine reactions.

Other efficacy activated processes in the affective domain concern

the impact of perceived coping efficacy on biochemical mediators of

health funetioning. Stress has been implicated as an important contri

buting factor to many physical dysfunetions. Controllability appears to

be a key organising principie regarding the nature of these stress effects.

Exposure to Stressors with Controlling efficacy has no adverse physiolo

gical effects. But exposure to the same Stressors without Controlling

efficacy impairs the immune system (Coe & Levine, 1989; Maier, Laud

enslager & Ryan, 1985). Physiological Systems are highly interdependent.

The types of biochemical reactions that have been shown to accompany

a weak sense of copin efficacy are involved in the régulation of immune

Systems. For example, perceived weak efficacy in exercising control over

Stressors actívate endogenous opioid Systems (Bandura, Cioffi, Taylor &

Brouillard, 1988). There is evidence that some of the immunosuppressive

effects of inefficacy in Controlling Stressors are mediated by release of

endogenous Opioids. When opioid mechanisms are blocked by opiate

rev. eep. ped. XLVIII. 18?. 1990

This content downloaded from

131.179.158.26 on Sat, 27 Feb 2021 22:56:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

416 ALBERT BANDURA

antagonists, the stress of weak copi

sive capabilities (Shavit & Martin,

In the laboratory research demostr

stress médiation, controllability i

property in whidh animais either ex

Stressors, or they have no control,

powerless in the face of unremit

contrast, most human stress is act

to exercise control over recurring S

coping mastery may have very diff

situations with no prospect in sight

efficacy. It would not be evolution

invariably impaired immune fune

everyday life. If this were the cas

high vulnerability to infective agen

There would be evolutionary ben

immune funetion while one is aoqui

prolonged stress of coping ineffic

System. Indeed, we find that stre

coping efficacy over phobie Stressor

11). However, some individuáis exhib

during the efficacy acquisition phas

a good predictor of whether expo

suppresses various components of

O'Leary, Bandura, Brown, Levine &

of pereeived coping efficacy, the gr

autonomie arousal and neuroendocr

Systems status, but their impact is

Anxiety arousal in situations invol

by pereeived coping efficacy, but

distressing cognitions. The exercis

ness is summed up well in the pro

of worry and carie from flying ove

from building a nest in your kead

control is a key factor in the régula

It is not the sheer frequency of dis

inability to turn them off that is

1987; Salkovskis & Harrison, 198

cognitions is unrelated to anxiety

tions is controlled (Kent & Gibbons,

The dual control of anxiety an

efficacy and thought control efficac

rev. esp. ped. XLVIII, 187, 1990

This content downloaded from

131.179.158.26 on Sat, 27 Feb 2021 22:56:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

PERCEIVED SELF-EFFICACY IN THE EXERCISE... 417

isms governing personal empowerment over pervasive socia

(Ozer & Badura, 1989). Sexual violence toward women is a pr

Problems. Because any woman may be a potential victim, the

many women are distressed and constricted by a sense of ineffi

cope with the threat of sexual assault. To address this problem a

protective level, women participated in a mastery modelling pro

in which they mastered the physical skills to defend themselves

sfully against sexual assailants. Mastery modelling enhanced

coping efficacy and cognitive 'control efficacy, decreased percei

nerability to assault and reduced the incidence of instrusive

and anxiety arousal. These changes were accompanied by

freedom of action and decreased avoidant social behavior. Path

of the causal estructure revealed a dual path of régulation of be

by perceived self-efficacy: One path was mediated through the

perceived coping self-efficacy on perceived vulnerability and

cernment, and the other through the impact of perceived

control iself-efficacy on intrusive aversive thoughts (Figure 12).

sense of coping efficacy rooted in performance capabilities has

tial impact on perceived self-efficacy to abort the escalation

veration of perturbing cognitions.

Perceived coping efficacy reguates avoidance behaviour in

Situation, as well as anxiety arousal. The stronger the perceiv

efficacy the more venturesome thé behaviour, regardless of wh

beliefs of efficacy are strengthened by mastery expériences, m

influences, or cognitive simulations. The role of perceived self-

and anxiety arousal in the causal structure of avoidant behav

been examined in a number of studies. The results show that pe

their actions on self-percepts of efficacy in situation they regard

Williams and his colleagues (Williams, Kinney & Falbo, 1989;

Dooseman & Kleifield, 1984; Williams, Turner & Peer, 1

analysed by partial corrélation numerous data sets from st

which perceived self-efficacy, anticipated anxiety, and phobie b

were measured. Perceived self-efficacy aecount for a substantia

of variance in phobie behaviour when anticipated anxiety is

out, whereas the relationship between anticipated anxiety an

behaviour essentially disappears when perceived self-efficacy is

out (Table 1). Studies of other threatening activities similary de

the prédictive superiority of perceived self-efficacy over percei

ous outcomes in level of anxiety arousal. (Hackett & Betz, 19

1983; McAuley, 1985; Williams & Watson, 1985).

The data taken as a whole indícate that anxiety arousal and

behaviour are largely coeffects of perceived coping ineffica

rev. esp. ped. XLVIII, 187, 1998

This content downloaded from

131.179.158.26 on Sat, 27 Feb 2021 22:56:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

418 ALBERT BANDURA

Table 1

COPING BEHAVIOR

AJVnCIPATKD ANXIETY

ANTICIPATED ANXIETY PERCEIVED

PERCFJVED SELF-EFFICACY

SELF-EFFICACY

wiik

wük with

wi(h

Seif-Efficacy

Self-Efficacy ControHed

Controlled AnticHwted

Anticipated Anxiety Controlled

Controllcd

Williams

Williams & Rappoport

& Rappoport

(1983)(1983)

Pretreatment 1 —.12 .40*

Pretreatment

Pretreatment 2

2 —.28

—.28 .59**

.59»*

Posttreatment .13 .45*

Follow-up .06 .45*

Williams et al. (1984)

Pretreatment —36* .22

Posttreatment —21 .59* ••**

Williams et al. (1985)

Pretreatment

Pretreatment —.35*

—35* .28*

.28*

Posttreatment .05 .72***

Follow-up —.12 .66***

Teich et al. (1985)

Telch

Pretreatment —36*** —2&

Posttreatment .15 .48* •

Follow-up —.05 .42*

Kirsch et al. (1983)

Pretreatment —34* .54***

Posttreatment —.48** .48*

Arnow et al. (1985)

Pretreatment .17 .77* **

Posttreatment —.08 .43*

Follow-up —.06 .88**

Williams et al. (1989)

Midtreatment —.15 .65***

Posttreatment .02 .47**

Follow-up —.03

—.03 .71***

.71* ••

*p<.05

**p<J)l

***p<.001

rev. esp. ped. XLV4JI, 187. 1990

This content downloaded from

131.179.158.26 on Sat, 27 Feb 2021 22:56:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

PERCEIVED SELF-EFFICACY IN THE EXERCISE... 419

than causally linked. People avoid potentiaily threatening s

activities, not because they experience anxiety arousal or a

will be anxious, büt because they believe they will be

successfully with situations they regard as risky. They take

action regardless of whether or not they happen to be

moment. They do not have to conjure up an anxious Sta

can take action. They commonly perform risky activi

strengths of perceived self-efficacy despite high anxiety ar

1988a or b).

Perceived self-efficacy to exercise control can give rise t

as well as anxiety. The nature of the outcomes Over w

control is sought opérâtes as an important differentiating

experience anxiety when they perceive themselves rll equi

potentiaily injurious events. Atténuation or control of

mes is central to anxiety. People are saddened and depr

perceived inefficacy in gaining highly valued outcomes. Ir

or failure to gain valued outcomes figures prominently in

Several lines of evidence support the role of perceived s

in dépression. Perceived inefficacy to fulfil goals that aff

of self-worth and to secure things that bring satisfacti

can give rise to bouts of dépression (Bandura, 1988a

lahan, 1987a, b; Kanfer & Zeiss, 1983). When the perceived

involves social relationships, it can induce dépression bo

indirectly by curtailing the cultivation of the very int

tionships that can provide satisfactions and buffer the ef

daily stressors (Holahan & Holahand, 1987a). A low sense

fulfil role demans that reflect on personal adequacy also c

dépression Cutrona & Troutman, 1986). When the value

seeks also protect against future aversive circumstances, a

to secure a job jeopardises one's livelihood, perceived sel

both distressing and depressing. Because of the interd

outcomes, both anxiety and despair often accompany perc

efficacy.

Self-regulatory théories of motivation and of dépression make

seemingly contradictory prédictions regarding the effects of negative

discrepancies between attainments and standards. Standards that exceed

attainments are said to enhance motivation through goal challenges, but

negative discrepancies are also invoked as activators of despondent

mood. Moreover, when negative discrepancies do have adverse effects,

they may give rise to apathy rather than to despondency. A conceptual

scheme is needed that differentiates the conditions under which negative

discrepancies will be motivating, depressing, or induce apathy.

rev. esp. ped. XLVHI. 187. 1990

This content downloaded from

131.179.158.26 on Sat, 27 Feb 2021 22:56:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

420 ALBERT BANDURA

In accord with social cognitive theory, the d

negative goal discrepancies are predictable fro

ween perceived self-efficacy for goal attainmen

goals (Bandura & Abrams, 1986). Whether nega

motivating or depressing dépends on beliefs on on

them. Negative disparities give rise to high mot

dency when people believe they have the efficacy

and continue to strive for them. Negative dispari

and genera te despondency for people who jud'ge

cious to attain difficult goals but continue to dema

People who view difficult goals as beyond their ca

them as unrealistic for themselves become apa

pondent.

Much human dépression is oognitively generated by dejecting thought

patterns. Therefore, perceived self-efficacy to exercise control over

ruminative thought figures prominently in the occurrence, duration and

récurrence of depressive épisodes. Kavanagh and Wilson (1988) found

that the weaker the perceived efficacy to termínate ruminative thoughts

the higher the dépression (r = .51), and the stronger the perceived

thought control efficacy intilled through treatment the greater the de

cline in dépression (r = .71) and the lower the vulneräbility to récurrence

of depressive épisodes (r = -.48). Perceived self-efficacy retains its pre

dictiveness of improvement and reduced vulneräbility to relapse when

level of prior dépression is contrölled.

D. Sélection processes

People can exert some influence over their life paths by the environ

ments they select and environments they create. Thus far, the discussion

has centred on efficacy-related processes that enable people to create

bénéficiai environments and to exercise control over them. Judgements

of personal efficacy also shape developmental trajectories by influencing

sélection of activities and situations they believe exceed their coping

capabilities, but they readily undertake challenging activities and pick

social environments they judge themselves capable of handing. Any

factor that influences choice behaviour can profoundly affect the direc

tion of personal development. This is because the social influences opera

ting in selected environments continue to promote certain competencies,

values, and interests long after the decisional déterminant has rendered

its inaugurating effect (Bandura, 1968; Snyder, 1986). Thus, seemingly

inconsequential efficacy déterminants can initiate sélective associations

that produce major and enduring personal changes.

The power of self-efficacy beliefs to affect the course of life paths

rev. esp, ped. XLVIII, 187, 1990

This content downloaded from

131.179.158.26 on Sat, 27 Feb 2021 22:56:42 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

PERCEIVED SELF-EFFICACY IN THE EXERCISE... 421

tbrough choice-related processes is most clearly reveale

career decision-making and career development (Betz &

Lent & Hackett, 1987). The stronger people's self-belief