Professional Documents

Culture Documents

6.3 Political and Monetary Union

6.3 Political and Monetary Union

Uploaded by

koraOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

6.3 Political and Monetary Union

6.3 Political and Monetary Union

Uploaded by

koraCopyright:

Available Formats

986 Matthew Canzoneri et al.

robust — most significantly the first two noted previously. Others are less so.50 On

the other hand, by using the same model, we are able to make consistent comparisons

that are not otherwise possible because the existing literature uses a variety of

models.

An additional reason for placing less emphasis on particular quantitative results is

that we use a linear approximation to the model around a nonstochastic steady state.

Chari, Christiano, and Kehoe (1995) provide examples of inaccuracies that can arise

when doing so. Albanesi (2003) argues that concerns about the methods we use can

be more serious because of the unit roots or near unit roots in the responses of key

var- iable to shocks. On the other hand, both Benigno and Woodford (2006) and

Schmitt- Grohe and Uribe (2004a) find that their log-linear approximations do not

suffer from accuracy problems. Benigno and Woodford (2006) examine the model

considered by Chari et al. (1995). They find that the numerical results they obtain

using their lin- ear-quadratic methods are quite close to those Chari et al. (1995)

report based on more computationally intensive projection methods, but substantially

different from those Chari et al. (1995) report based on log- linearization. Schmitt-

Grohe and Uribe (2004a) address accuracy concerns by comparing the moments

computed from exact solution of their model with flexible prices to those computed

from a log-linear approximation. They find the differences are small, except that the

approximate solu- tion produces an inflation volatility that is about one percentage

point too low. They cannot compute the exact solution of their model when prices are

sticky but they com- pare the moments computed from a first-order approximation to

the model with those computed from a second-order approximation in samples of 100

years. They argue that if the unit root behavior is a serious problem and over 100

years variables wander far from the point around which the model is approximated,

then the errors are likely to be considerably larger in the moments computed from

the second-order approxima- tion. They find the results from the first- and second-

order approximations are very close. Our reason for reporting moments computed

from simulated samples of 200 quarterly observations is the hope of mitigating these

problems.

We begin by considering the optimal choice of inflation and the tax rate on wage

income when profits are fully taxed. The implications for optimal inflation and

interest rates are summarized in Table 3 and Figures 7A and B. Not surprisingly, the

Friedman rule is optimal when prices are flexible. The nominal interest rate is zero in

every period so that both the average interest rate and its volatility are zero. Average

inflation is approximately -1% per quarter, which is approximately minus one times

the real interest rate (gross inflation in the nonstochastic steady state is equal to b).

Unexpected

50

For example, the incentive to use inflation to tax profits is robust, but the magnitude of steady-state inflation is not.

We find positive inflation is optimal when profits are less than fully taxed. Schmitt-Grohe and Uribe (2004b) find

that nominal interest rates are positive but that deflation (albeit less deflation than under the Friedman rule) is

optimal unless the elasticity of substitution between the intermediate goods is lower than our benchmark value.

When we consider a model similar to theirs, we replicate their results.

The Politics of Monetary Policy

1045

6.3 Political and monetary union

In addition to its economic costs and benefits, the monetary union in Europe has been

seen by many as an important step toward political unification. Therefore the benefits

of the euro include its help toward political integration.

This argument has two parts: one is that political unification is desirable and, second

that the Euro will help to achieve this goal. This is not the place to discuss in detail the

first point, but political unification in Europe seems to have stalled. 52 On the second

point, using the euro as a political tool to unify Europe raises a bit of healthy skepti-

cism. To begin with only a subset of EU countries have adopted the euro. Thus if

the euro is a symbol and a necessity for political union it would imply a very strange

“United States of Europe,” which would not include the UK, Sweden, and Denmark,

countries that are an integral part of the economic union. More generally Europe is

evolving into a collection of countries that share some policies (say monetary policies)

and a collection that shares other policies (say open borders for travelers, the Schengen

Treaty). The recent enlargement of the EU to 27 country members has made it less

likely that the degree of political integration will intensify due to the large differences

of member countries. Third, recent attempts to deepen political ties, like the adoption

of a European Constitution, have received limited support from European citizens.

Finally, every time a crisis hits Europe its institutions seem to take a secondary role.

For instance, for all the talk about fiscal coordination at the onset of the recent crisis

every country went on its own and there were hints of “beggar thy neighbor poli-

cies.”53 Rather than fiscal policy coordination, in 2008 and 2009 the feeling among

member countries was to make sure that nobody benefited by other countries expan-

sionary fiscal policies and the associated domestic debts. Foreign policy disagreements

and inability to act as a unit have been even more obvious. The EU has made impor-

tant progress in establishing a common market; eliminating some, but not all, ineffi-

cient government regulations; and promoting some reforms especially in goods

markets.54 This is all good, but it is well short of political union. In fact, one may won-

der whether political union would necessarily make reforms more or less likely to be

adopted. Some commentators argue that some of the reform policies promoted by

the European Commission, regarding avoidance of government subsidies, elimination

of indirect trade barriers, and so forth have occurred precisely because this body is

relatively nonpolitical and unresponsive to the European Parliament.55 The EU is

52

See Alesina and Perotti (2004) for a critical view of the process of European Unification. Issing (2010) also noted

how the euro will have to live without a political union behind it.

53

Ireland, for instance, at the onset of the crisis introduced emergency banking policies that negatively affected British

Banks.

54

See Alesina, Ardagna, and Galasso (2010) for a recent discussion of the effect of the euro adoption on labor and good

market reforms.

55

On these issues see Alesina and Perotti (2004) and several essays in Alesina and Giavazzi (2010).

You might also like

- Ibanq Pricing ScheduleDocument8 pagesIbanq Pricing ScheduleIPTV GangNo ratings yet

- Chap 009Document99 pagesChap 009WOw Wong100% (1)

- 2015 European Guide PDFDocument127 pages2015 European Guide PDFYiannis KatsanevakisNo ratings yet

- AnswerDocument8 pagesAnswerJericho PedragosaNo ratings yet

- Cash BudgetDocument3 pagesCash BudgetJann Kerky0% (1)

- Economic Reforms in The Euro Area: Is There A Common Agenda?Document9 pagesEconomic Reforms in The Euro Area: Is There A Common Agenda?BruegelNo ratings yet

- Ribba Ecomod2016Document28 pagesRibba Ecomod2016george wilfredNo ratings yet

- International Policy Coordination and Simple Monetary Policy RulesDocument29 pagesInternational Policy Coordination and Simple Monetary Policy Rulesramadhanangsu123No ratings yet

- Media 22258 SMXXDocument34 pagesMedia 22258 SMXXMissaoui IbtissemNo ratings yet

- Perotti (2002)Document60 pagesPerotti (2002)Hoang Lan HuongNo ratings yet

- Interest Rate Pass-Through, Monetary Policy Rules and Macroeconomic StabilityDocument39 pagesInterest Rate Pass-Through, Monetary Policy Rules and Macroeconomic Stabilitybrendan lanzaNo ratings yet

- Becchetti Et Al - 2010 - The Effects of Age and Job Protection On The Welfare Costs of Inflation andDocument10 pagesBecchetti Et Al - 2010 - The Effects of Age and Job Protection On The Welfare Costs of Inflation andxintong ZHOUNo ratings yet

- Efecto de La gLOBALIZACIÓN SOBTRE LA Inflación en La Era DE Gran Moderación - Nueva Evidencia de Los Países Del G-10Document36 pagesEfecto de La gLOBALIZACIÓN SOBTRE LA Inflación en La Era DE Gran Moderación - Nueva Evidencia de Los Países Del G-10Inocente ReyesNo ratings yet

- Labor Market SclerosisDocument49 pagesLabor Market SclerosisKarthy MurthyNo ratings yet

- WK 11 SupplementDocument10 pagesWK 11 SupplementShou Yee WongNo ratings yet

- Article 1Document39 pagesArticle 1Bel Bahadur BoharaNo ratings yet

- Bargaining Success in The Reform Od The EurozoneDocument24 pagesBargaining Success in The Reform Od The EurozoneLejla ČauševićNo ratings yet

- Marattin SalottiDocument21 pagesMarattin SalottiozhKlNo ratings yet

- Fidrmuc 2013Document11 pagesFidrmuc 2013Aleksandar VučićNo ratings yet

- Cassette 2013Document20 pagesCassette 2013gas bagasNo ratings yet

- The Relative Impact of Fiscal Versus Monetary Actions On Output: A Vector Autoregressive (VAR) ApproachDocument11 pagesThe Relative Impact of Fiscal Versus Monetary Actions On Output: A Vector Autoregressive (VAR) ApproachwmmahrousNo ratings yet

- Interest Linkages Between The US, UK and German Interest Rates: Should The UK Join The European Monetary Union?Document31 pagesInterest Linkages Between The US, UK and German Interest Rates: Should The UK Join The European Monetary Union?Elishiwa MondezakiNo ratings yet

- The Regional Effects of Monetary Policy in EuropeDocument20 pagesThe Regional Effects of Monetary Policy in EuropeKanita Imamovic-CizmicNo ratings yet

- Decentralization and Supranationality: The Case of The European UnionDocument41 pagesDecentralization and Supranationality: The Case of The European UnionRicardo OrsiniNo ratings yet

- 2005 - NominalRigiditiesPM - Christiano Et - AlDocument45 pages2005 - NominalRigiditiesPM - Christiano Et - AlJuan Manuel Báez CanoNo ratings yet

- Journal - Average-Costpricing - Some Evidence and ImplicationsDocument16 pagesJournal - Average-Costpricing - Some Evidence and ImplicationsSirajudin HamdyNo ratings yet

- Demand-Side or Supply-Side Stabilisation PoliciesDocument19 pagesDemand-Side or Supply-Side Stabilisation PoliciesaronNo ratings yet

- Credit Controls Did Matter Dec.09Document62 pagesCredit Controls Did Matter Dec.09Pata nahiNo ratings yet

- Inflación Precios Relativos y RigidecsDocument25 pagesInflación Precios Relativos y RigidecsPablo GimenezNo ratings yet

- Confp 04 PDocument22 pagesConfp 04 PSherwein AllysonNo ratings yet

- Romero-Avila and Strauch (2008)Document20 pagesRomero-Avila and Strauch (2008)meone99No ratings yet

- Policy Volatility and Economic GrowthDocument40 pagesPolicy Volatility and Economic GrowthIoanNo ratings yet

- Fundamental Flaws in The European Project: George Irvin, Alex IzurietaDocument3 pagesFundamental Flaws in The European Project: George Irvin, Alex IzurietaAkshay SharmaNo ratings yet

- Art On DebtDocument24 pagesArt On DebtJosé Antonio PoncelaNo ratings yet

- Bank Credit and Economic Growth in EU-27Document10 pagesBank Credit and Economic Growth in EU-27subornoNo ratings yet

- Panteion University, Greece: T.panagiotidis@lboro - Ac.ukDocument18 pagesPanteion University, Greece: T.panagiotidis@lboro - Ac.ukHerlan Setiawan SihombingNo ratings yet

- PC 2015 09 PDFDocument23 pagesPC 2015 09 PDFBruegelNo ratings yet

- Monetary Policy, Currency Unions and Open Economy MacrodynamicsDocument50 pagesMonetary Policy, Currency Unions and Open Economy MacrodynamicsrerereNo ratings yet

- British Trade UnionsDocument15 pagesBritish Trade UnionsHemant MeenaNo ratings yet

- Markov Switching Monetary Policy in A Two-Country DSGE ModelDocument40 pagesMarkov Switching Monetary Policy in A Two-Country DSGE ModelMario RengNo ratings yet

- The Effectiveness of Tax Rebates As Countercyclical Fiscal Policy - CEPRDocument6 pagesThe Effectiveness of Tax Rebates As Countercyclical Fiscal Policy - CEPRSherry LiuNo ratings yet

- The Macroeconomic Costs and Benefits of The EMU and Other Monetary Unions: An Overview of Recent ResearchDocument40 pagesThe Macroeconomic Costs and Benefits of The EMU and Other Monetary Unions: An Overview of Recent Researchskavi_2702No ratings yet

- Does Political Instability Lead To Higher Inflation? A Panel Data AnalysisDocument16 pagesDoes Political Instability Lead To Higher Inflation? A Panel Data AnalysisMalik Moammar HafeezNo ratings yet

- Reading 5. Is Quantity Theory Still AliveDocument23 pagesReading 5. Is Quantity Theory Still Alivetranthaichau.tcNo ratings yet

- Sander (2001) Asymmetric Adjustment of Commercial Bank Interest Rates in The Euro Area An Empirical Investigation Into Interest Rate Pass-ThroughDocument21 pagesSander (2001) Asymmetric Adjustment of Commercial Bank Interest Rates in The Euro Area An Empirical Investigation Into Interest Rate Pass-ThroughБоби ПетровNo ratings yet

- Acocella - Di Bartolomeo Non-Neutrality of Monetary Policy in Policy Games (2004)Document13 pagesAcocella - Di Bartolomeo Non-Neutrality of Monetary Policy in Policy Games (2004)Juan Manuel Cisneros GarcíaNo ratings yet

- The Euro Crisis: It Isn'T Just Fiscal and It Doesn'T Just Involve GreeceDocument37 pagesThe Euro Crisis: It Isn'T Just Fiscal and It Doesn'T Just Involve GreecePuneet GroverNo ratings yet

- Does Trade Liberalization Impact in Ation Dynamics? Evidence From A Natural ExperimentDocument36 pagesDoes Trade Liberalization Impact in Ation Dynamics? Evidence From A Natural ExperimentDaniel A. DiasNo ratings yet

- Stabilization Policy EurozoneDocument28 pagesStabilization Policy EurozoneafzalNo ratings yet

- Economist and The European Democratic Deficit (O'Rourke 2015)Document6 pagesEconomist and The European Democratic Deficit (O'Rourke 2015)Latoya LewisNo ratings yet

- Monetary Policy Product MarketDocument53 pagesMonetary Policy Product MarkethearthstonetrixelNo ratings yet

- Euro 3Document38 pagesEuro 3Madalina TalpauNo ratings yet

- DP 13097Document51 pagesDP 13097zwapsNo ratings yet

- Evaluating Rules in The Fed's Report and Measuring DiscretionDocument25 pagesEvaluating Rules in The Fed's Report and Measuring DiscretionCésar ÁngelesNo ratings yet

- Política Monetaria y FiscalDocument32 pagesPolítica Monetaria y FiscalAnuar AncheliaNo ratings yet

- Old K Vs NK Government MultipiersDocument23 pagesOld K Vs NK Government MultipiersSilvio GuerraNo ratings yet

- MPRA Paper 68704Document31 pagesMPRA Paper 68704TBP_Think_TankNo ratings yet

- Rules and Risk in The Euro Area: HighlightsDocument29 pagesRules and Risk in The Euro Area: HighlightsBruegelNo ratings yet

- The G20 in The Aftermath of The Crisis: A Euro-Asian ViewDocument7 pagesThe G20 in The Aftermath of The Crisis: A Euro-Asian ViewBruegelNo ratings yet

- European Integration and Economic Policy Coordination (2000) : Assignment 1999-2000 inDocument7 pagesEuropean Integration and Economic Policy Coordination (2000) : Assignment 1999-2000 inKonstantinos KostoulasNo ratings yet

- The Driving Factors of EMU GovDocument13 pagesThe Driving Factors of EMU GovekoNo ratings yet

- PubCh09 Revised FinalDocument30 pagesPubCh09 Revised FinalKDEWolfNo ratings yet

- NBER Macroeconomics Annual 2016From EverandNBER Macroeconomics Annual 2016Martin EichenbaumNo ratings yet

- 3.2 Model Misspecification: Lars Peter Hansen and Thomas J. SargentDocument2 pages3.2 Model Misspecification: Lars Peter Hansen and Thomas J. SargentkoraNo ratings yet

- Ebouk Monetary Economics 05Document2 pagesEbouk Monetary Economics 05koraNo ratings yet

- Ebouk Monetary Economics 03Document4 pagesEbouk Monetary Economics 03koraNo ratings yet

- Ebouk Monetary Economics 08Document2 pagesEbouk Monetary Economics 08koraNo ratings yet

- Figure 2 Annual CPI Inflation Rates.: UK TheDocument2 pagesFigure 2 Annual CPI Inflation Rates.: UK ThekoraNo ratings yet

- Ebouk Monetary Economics 10Document2 pagesEbouk Monetary Economics 10koraNo ratings yet

- Ebouk Monetary Economics 03Document2 pagesEbouk Monetary Economics 03koraNo ratings yet

- Ebouk Monetary Economics 05Document2 pagesEbouk Monetary Economics 05koraNo ratings yet

- Foreword: International Monetary Stability (OUP, 2006), I Very Much Doubt Whether She Then ExpectedDocument789 pagesForeword: International Monetary Stability (OUP, 2006), I Very Much Doubt Whether She Then Expectedakshat0tiwariNo ratings yet

- BTG Pactual CEO ConferenceDocument34 pagesBTG Pactual CEO ConferenceFibriaRINo ratings yet

- Cityam 2012-02-23Document36 pagesCityam 2012-02-23City A.M.No ratings yet

- Eurocurrency MarketDocument42 pagesEurocurrency Marketsweeta333100% (8)

- ECON 1000 Midterm W PracticeDocument7 pagesECON 1000 Midterm W Practiceexamkiller100% (1)

- AUG 03 Danske EMEADailyDocument3 pagesAUG 03 Danske EMEADailyMiir ViirNo ratings yet

- ADL 84 International Business Environment V2Document16 pagesADL 84 International Business Environment V2ajay_aju212000No ratings yet

- Free Numerical Reasoning Test QuestionsDocument16 pagesFree Numerical Reasoning Test QuestionsCristina Iv100% (1)

- Business Plan MarketingDocument8 pagesBusiness Plan MarketingNadia NsiriNo ratings yet

- BLADES Chuong 4Document2 pagesBLADES Chuong 4Mỹ Trâm Trương ThịNo ratings yet

- ATFX 2023Q2 EN MY ADocument58 pagesATFX 2023Q2 EN MY Anguyen thanhNo ratings yet

- Euro Currency MarketDocument30 pagesEuro Currency MarketHarmeet KaurNo ratings yet

- Van Rompuy Report - Towards A Stronger Economic UnionDocument5 pagesVan Rompuy Report - Towards A Stronger Economic UnionTelegraphUKNo ratings yet

- 2012 Annual Report Freudenberg enDocument161 pages2012 Annual Report Freudenberg enraghavak88No ratings yet

- Shaheed Sukhdev College of Business StudiesDocument27 pagesShaheed Sukhdev College of Business StudiesAshok GuptaNo ratings yet

- SFC 2012Document950 pagesSFC 2012ckanyuckNo ratings yet

- The Economist UK Edition - May 29 2021Document88 pagesThe Economist UK Edition - May 29 2021linh myNo ratings yet

- Deal or No Deal (MATH) PDFDocument50 pagesDeal or No Deal (MATH) PDFJalal Masoumi KozekananNo ratings yet

- BBDO KNOWS Banking Industry Challenges Part OneDocument32 pagesBBDO KNOWS Banking Industry Challenges Part OneDigital LabNo ratings yet

- Cost CentersDocument46 pagesCost CentersPallavi ChawlaNo ratings yet

- Module 9 - Foreign Exchange MarketsDocument9 pagesModule 9 - Foreign Exchange MarketsChris tine Mae MendozaNo ratings yet

- CI Signature Dividend FundDocument2 pagesCI Signature Dividend Fundkirby333No ratings yet

- CafrDocument309 pagesCafrGenetopia100% (1)

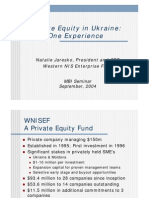

- WNISEF Experience in UkraineDocument21 pagesWNISEF Experience in UkraineVitaliy HamuhaNo ratings yet

- Publishing Proposal For The Central States Water Environment Association From Craig Kelman & AssociatesDocument4 pagesPublishing Proposal For The Central States Water Environment Association From Craig Kelman & AssociatesIndra ArdarajaNo ratings yet