Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Arts and The Mass Media by Lawrence Alloway

The Arts and The Mass Media by Lawrence Alloway

Uploaded by

macarena vOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Arts and The Mass Media by Lawrence Alloway

The Arts and The Mass Media by Lawrence Alloway

Uploaded by

macarena vCopyright:

Available Formats

warholstars.

org

news - about - citations - contents - timeline - superstars - films - art - abstract

expressionism - home

Lawrence Alloway is often incorrectly credited with the first published use of the term "Pop Art" in

the following article which first appeared in the February 1958 issue of Architectural Design &

Construction. Note that although the article does contain references to "mass popular art," the actual

term "Pop Art" is never used. The first use of "pop art" in print was in the UK - in But Today We

Collect Ads by Alison and Peter Smithson in the November 18, 1956 article in Ark. gc.

The Arts and the Mass Media

by Lawrence Alloway

In Architectural Design last December there was a discussion of "the problem that faces the architect

to-day - democracy face to face with hugeness - mass society, mass housing, universal mobility."

The architect is not the only kind of person in this position; everybody who works for the public in a

creative capacity is face to face with the many-headed monster. There are heads and to spare.

Before 1800 the population of Europe was an estimated 180 million; by 1900 this figure had risen to

460 million. The increase of population and the industrial revolution that paced it have, as everybody

knows, changed the world. In the arts, however, traditional ideas have persisted, to limit the

definition of later developments. As Ortega pointed out in The Revolt of the Masses: "the masses are

to-day exercising functions in social life which coincide with those which hitherto seemed reserved to

minorities." As a result the élite, accustomed to set aesthetic standards, has found that it no longer

possesses the power to dominate all aspects of art. It is in this situation that we need to consider the

arts of the mass media. It is impossible to see them clearly within a code of aesthetics associated

with minorities with pastoral and upperclass ideas because mass art is urban and democratic.

It is no good giving a literary critic modern science fiction to review, no good sending the theatre

critic to the movies, and no good asking the music critic for an opinion on Elvis Presley. Here is an

example of what happens to critics who approach mass art with minority assumptions. John Wain,

after listing some of the spectacular characters in P.C. Wren's Beau Geste observes: "It sounds rich.

But in fact - as the practised reader could easily forsee... it is not rich. Books with this kind of

subject matter seldom are. They are lifeless, petrified by the inert conventions of the adventure

yarn." In fact, the practised reader is the one who understands the conventions of the work he is

reading. From outside all Wain can see are inert conventions; from inside the view is better and from

inside the conventions appear as the containers of constantly shifting values and interests.

The Western movie, for example, often quoted as timeless and ritualistic, has since the end of World

War II been highly flexible. There have been cycles of psychological Westerns (complicated

characters, both the heroes and the villains), anthropological Westerns (attentive to Indian rights

and rites), weapon Westerns (Colt revolvers and repeating Winchesters as analogues of the present

armament race). The protagonist has changed greatly, too: the typical hero of the American

depression who married the boss's daughter and so entered the bright archaic world of the

gentleman has vanished. The ideal of the gentleman has expired, too, and with it evening dress

which is no longer part of the typical hero-garb.

If justice is to be done to the mass arts which are, after all, one of the most remarkable and

characteristic achievements of industrial society, some of the common objections to them need to be

faced. A summary of the opposition to mass popular art is in Avant Garde and Kitsch (Partisan

Review, 1939, Horizon, 1940), by Clement Greenberg, an art critic and a good one, but fatally

prejudiced when he leaves modern fine art. By kitsch he means "popular, commercial art and

literature, with their chromeotypes, magazine covers, illustrations, advertisements, slick and pulp

fiction, comics, Tin Pan Alley music, tap-dancing, Hollywood movies, etc..." All these activities to

Greenberg and the minority he speaks for are "ersatz culture... destined for those who are insensible

to the value of genuine culture welcomes and cultivates this insensibility" (my italics). Greenberg

insists that "all kitsch is academic," but only some of it is, such as Cecil B. De Mille-type historical

epics which use nineteenth-century history-picture material. In fact, stylistically, technically,

iconographically the mass arts are anti-academic. Topicality and a rapid rate of change are not

academic in any usual sense of the word, which means a system that is static, rigid, self-

perpetuating. Sensitiveness to the variables of our life and economy enable the mass arts to

accompany the changes in our life far more closely that the fine arts which are a repository of time-

binding values.

The popular arts of our industrial civilization are geared to technical changes which occur, not

gradually, but violently and experimentally. The rise of the electronics era in communications

challenged the cinema. In reaction to the small TV screen, movie makers spread sideways

(CinemaScope) and back into space (Vista Vision). All the regular film critics opposed the new array

of shapes, but all have been accepted by the audiences. Technical change as dramatized novelty

(usually spurred by economic necessity) is characteristic not only of the cinema but of all the mass

arts. Colour TV, the improvements in colour printing (particularly in American magazines), the new

range of paper back books; all are part of the constant technical improvements in the channels of

mass communication.

An important factor in communication in the mass arts is high redundancy. TV plays, radio serials,

entertainers, tend to resemble each other (though there are important and clearly visible differences

for the expert consumer). You can go into the movies at any point, leave your seat, eat an ice-

cream, and still follow the action on the screen pretty well. The repetitive and overlapping structure

of modern entertainment works in two ways: (1) it permits marginal attention to suffice for those

spectators who like to talk, neck, parade; (2) it satisfies, for the absorbed spectator, the desire for

intense participation which leads to a careful discrimination of nuances in the action. There is in

popular art a continuum from data to fantasy. Fantasy resides in, to sample a few examples, film

stars, perfume ads, beauty and the beast situations, terrible deaths, sexy women. This is the aspect

of popular art which is most easily accepted by art minorities who see it as a vital substratum of the

folk, as something primitive. This notion has a history since Herder in the eighteenth century, who

emphasized national folk arts in opposition to international classicism. Now, however, mass-produced

folk art is international: Kim Novak, Galaxy Science Fiction, Mickey Spillane, are available wherever

you go in the West. However, fantasy is always given a keen topical edge; the sexy model is shaped

by datable fashion as well as by timeless lust. Thus, the mass arts orient the consumer in current

styles, even when they seem purely, timelessly erotic and fantastic. The mass media give perpetual

lessons in assimilation, instruction in role-taking, the use of new objects, the definition of changing

relationships, as David Riesman has pointed out. A clear example of this may be taken from science

fiction. Cybernetics, a new word to many people until 1956, was made the basis of stories in

Astounding Science Fiction in 1950. SF aids the assimilation of the mounting technical facts of this

century in which, as John W. Campbell, the editor of Astounding put it, "A man learns a pattern of

behavior - and in five years it doesn't work." Popular art, as a whole, offers imagery and plots to

control the changes in the world; everything in our culture that changes is the material of the

popular arts.

Critics of the mass media often complain of the hostility towards intellectuals and the lack of respect

for art expressed there, but, as I have tried to show, the feeling is mutual. Why should the mass

media turn the other cheek? What worries intellectuals is the fact that the mass arts spread; they

encroach on the high ground. For example, into architecture itself as Edmund Burke Feldman wrote

in Arts and Architecture last October: "Shelter, which began as a necessity, has become an industry

and now, with its refinements, is a popular art." This, as Feldman points out, has been brought about

by a "democratization of taste, a spread of knowledge about non-material developments, and a shift

of authority about manners and morals from the few to the many." West Coast domestic architecture

has become a symbol of a style of living as well as an example of architecture pure and simple; this

has occurred not through the agency of architects but through the association of stylish interiors

with leisure and the good life, mainly in mass circulation magazines for women and young marrieds.

The definition of culture is changing as a result of the pressure of the great audience, which is no

longer new but experienced in the consumption of its arts. Therefore, it is no longer sufficient to

define culture solely as something that a minority guards for the few and the future (though such art

is uniquely valuable and a precious as ever). Our definition of culture is being stretched beyond the

fine art limits imposed on it by Renaissance theory, and refers now, increasingly, to the whole

complex of human activities. Within this definition, rejection of the mass produced arts is not, as

critics think, a defence of culture but an attack on it. The new role for the academic is keeper of the

flame; the new role for the fine arts is to be one of the possible forms of communication in an

expanding framework that also includes the mass arts.

news - about - citations - contents - timeline - superstars - films - art - abstract

expressionism - home

You might also like

- The Experience of Architecture-Thames Hudson 2016 by Henry PlummerDocument420 pagesThe Experience of Architecture-Thames Hudson 2016 by Henry PlummerAli Ahmed100% (1)

- How Architecture Learned To SpeculateDocument23 pagesHow Architecture Learned To SpeculateAsli Serbest100% (1)

- Lawrence Alloway, The Arts and The Mass Media'Document3 pagesLawrence Alloway, The Arts and The Mass Media'myersal100% (2)

- My Home Is Wider Than My Walls: Mapping The Decisions Made in The Mixed-Use Housing Cooperative Spreefeld To Find How The Public Realm Outcomes Were AchievedDocument112 pagesMy Home Is Wider Than My Walls: Mapping The Decisions Made in The Mixed-Use Housing Cooperative Spreefeld To Find How The Public Realm Outcomes Were AchievedMelissa SohNo ratings yet

- Wagner, Modern Architecture, 1896Document3 pagesWagner, Modern Architecture, 1896Nicholas YinNo ratings yet

- Robin Evans 1997 Translations From Drawing To Building PDFDocument21 pagesRobin Evans 1997 Translations From Drawing To Building PDFrainreinaNo ratings yet

- Liane Lefevre and Alexander Tzonis - The Question of Autonomy in ArchitectureDocument11 pagesLiane Lefevre and Alexander Tzonis - The Question of Autonomy in ArchitecturevarasjNo ratings yet

- Living Differently, Seeing Differently: Carla Accardi's Temporary Structures (1965-1972) Teresa KittlerDocument23 pagesLiving Differently, Seeing Differently: Carla Accardi's Temporary Structures (1965-1972) Teresa KittlerAngyvir PadillaNo ratings yet

- Latent UtopiasDocument3 pagesLatent UtopiasIrina AndreiNo ratings yet

- Architettura e o Rivoluzione Up at The PDFDocument16 pagesArchitettura e o Rivoluzione Up at The PDFrolandojacobNo ratings yet

- Colomina - Blurred Visions - X-Ray Architecture PDFDocument22 pagesColomina - Blurred Visions - X-Ray Architecture PDFSilvia AlviteNo ratings yet

- Theory155 PDFDocument2 pagesTheory155 PDFmetamorfosisgirlNo ratings yet

- Lisbet Harboe PHD Social Concerns in Contemporary ArchitectureDocument356 pagesLisbet Harboe PHD Social Concerns in Contemporary ArchitectureCaesarCNo ratings yet

- Sanford Kwinter and Umberto Boccioni Landscapes of Change Assemblage No 19 Dec 1992 PP 50 65Document17 pagesSanford Kwinter and Umberto Boccioni Landscapes of Change Assemblage No 19 Dec 1992 PP 50 65andypenuelaNo ratings yet

- Zeinstra Houses of The FutureDocument12 pagesZeinstra Houses of The FutureFrancisco PereiraNo ratings yet

- Price Seth Fuck Seth PriceDocument125 pagesPrice Seth Fuck Seth Pricealberto.patinoNo ratings yet

- Alvaro Siza - Texts From Official WebsiteDocument29 pagesAlvaro Siza - Texts From Official WebsiteHarun AnaniasNo ratings yet

- February 22 - Hilde Heynen, Architecture and Modernity A Critique 2-18Document19 pagesFebruary 22 - Hilde Heynen, Architecture and Modernity A Critique 2-18Ayşe Nur TürkerNo ratings yet

- ARCH684 Velikov Theory Since 1989Document6 pagesARCH684 Velikov Theory Since 1989mlparedes2No ratings yet

- The Imaginary Real World of CyberCitiesDocument15 pagesThe Imaginary Real World of CyberCitiesMonja JovićNo ratings yet

- Soane and SchinkelDocument15 pagesSoane and SchinkelPaul GaoNo ratings yet

- Dance For Architecture STEVEN HOLL ARCHITECTSDocument35 pagesDance For Architecture STEVEN HOLL ARCHITECTSalvin hadiwono (10303008)No ratings yet

- Kitsch: European Science Photo Competition 2015Document8 pagesKitsch: European Science Photo Competition 2015tokagheruNo ratings yet

- Pelkonen What About Space 2013Document7 pagesPelkonen What About Space 2013Annie PedretNo ratings yet

- Derrida and EisenmanDocument25 pagesDerrida and EisenmanNicoleta EnacheNo ratings yet

- Conversa Entre Peter Eisennmann e Richard SerraDocument9 pagesConversa Entre Peter Eisennmann e Richard SerraRenataScovinoNo ratings yet

- An Architecture - Brian HeagneyDocument38 pagesAn Architecture - Brian HeagneyLinda PotopeaNo ratings yet

- Somol and Whiting - DopplerDocument7 pagesSomol and Whiting - Dopplercottchen6605No ratings yet

- Allen 1999 Infrastructural+UrbanismDocument10 pagesAllen 1999 Infrastructural+UrbanismMOGNo ratings yet

- Kurokawa Philosophy of SymbiosisDocument16 pagesKurokawa Philosophy of SymbiosisImron SeptiantoriNo ratings yet

- SYLLABUS. MediaArchitecture. MatternDocument8 pagesSYLLABUS. MediaArchitecture. MatternIrene Depetris-ChauvinNo ratings yet

- Lavin Temporary ContemporaryDocument9 pagesLavin Temporary Contemporaryshumispace3190% (1)

- Globaltools SCRD PDFDocument173 pagesGlobaltools SCRD PDFDouglas PastoriNo ratings yet

- Architecture Depends by Jeremy Till: SAMPLE CHAPTER: Introduction - The Elevator PitchDocument4 pagesArchitecture Depends by Jeremy Till: SAMPLE CHAPTER: Introduction - The Elevator PitchAdministrator14% (7)

- Visualising Density Chapter 1Document28 pagesVisualising Density Chapter 1Liviu IancuNo ratings yet

- Modern Architecture Since 1900 Author William J FT CurtisDocument14 pagesModern Architecture Since 1900 Author William J FT CurtisMinotaureNo ratings yet

- Troubles in Theory III - The Dreat Divide - Technology Vs Tradition - Architectural ReviewDocument11 pagesTroubles in Theory III - The Dreat Divide - Technology Vs Tradition - Architectural ReviewPlastic SelvesNo ratings yet

- Anyone Corporation - Any PublicationsDocument7 pagesAnyone Corporation - Any Publicationsangykju2No ratings yet

- Ms. Susan M. Pojer Horace Greeley HS Chappaqua, NYDocument38 pagesMs. Susan M. Pojer Horace Greeley HS Chappaqua, NYPrakriti GoelNo ratings yet

- Invisible ArchitectureDocument2 pagesInvisible ArchitecturemehNo ratings yet

- Autonomous Architecture in Flanders PDFDocument13 pagesAutonomous Architecture in Flanders PDFMałgorzata BabskaNo ratings yet

- 3 EricOwenMoss WhichTruthDoYouWantToTellDocument3 pages3 EricOwenMoss WhichTruthDoYouWantToTellChelsea SciortinoNo ratings yet

- 1 Tschumi Get With The ProgrammeDocument3 pages1 Tschumi Get With The ProgrammeMaraSalajanNo ratings yet

- Behind The Postmodern FacadeDocument228 pagesBehind The Postmodern FacadeCarlo CayabaNo ratings yet

- Beatrice ColominaCorbusier Photography PDFDocument19 pagesBeatrice ColominaCorbusier Photography PDFToni SimóNo ratings yet

- Alto and SizaDocument14 pagesAlto and Sizashaily068574No ratings yet

- Remment Lucas KoolhaasDocument42 pagesRemment Lucas KoolhaasKu Hasna ZuriaNo ratings yet

- Typology of Public Space - Sandalack-UribeDocument41 pagesTypology of Public Space - Sandalack-UribeAubrey CruzNo ratings yet

- Hejduk's Chronotope / 1996 / K. Michael Hays, Centre Canadien D'architectureDocument2 pagesHejduk's Chronotope / 1996 / K. Michael Hays, Centre Canadien D'architectureNil NugnesNo ratings yet

- The Library As HeterotopiaDocument19 pagesThe Library As HeterotopiaguesstheguestNo ratings yet

- Heterotopian StudiesDocument13 pagesHeterotopian StudiesHernan Cuevas ValenzuelaNo ratings yet

- The MIT Press Perspecta: This Content Downloaded From 216.47.157.213 On Thu, 09 May 2019 15:20:49 UTCDocument14 pagesThe MIT Press Perspecta: This Content Downloaded From 216.47.157.213 On Thu, 09 May 2019 15:20:49 UTCPhyo Naing TunNo ratings yet

- The Parametric ParadigmDocument27 pagesThe Parametric Paradigmauberge666No ratings yet

- Eisenman Ten Canonical Buildings 1950 2000 2008 Email PDFDocument26 pagesEisenman Ten Canonical Buildings 1950 2000 2008 Email PDFVanessa Haddad0% (1)

- Alfred Preis Displaced: The Tropical Modernism of the Austrian Emigrant and Architect of the USS Arizona Memorial at Pearl HarborFrom EverandAlfred Preis Displaced: The Tropical Modernism of the Austrian Emigrant and Architect of the USS Arizona Memorial at Pearl HarborNo ratings yet

- The Canadian City: St. John's to Victoria: A Critical CommentaryFrom EverandThe Canadian City: St. John's to Victoria: A Critical CommentaryNo ratings yet

- Dingbat 2.0: The Iconic Los Angeles Apartment as Projection of a MetropolisFrom EverandDingbat 2.0: The Iconic Los Angeles Apartment as Projection of a MetropolisNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Arts TemplatesDocument3 pagesContemporary Arts Templatesana dontarNo ratings yet

- Lesson 8 Nature of Art Form in A MediumDocument5 pagesLesson 8 Nature of Art Form in A MediumGrace Tejano Sacabin-Amarga100% (1)

- Example of Art History ThesisDocument8 pagesExample of Art History Thesissew0m0muzyz3100% (2)

- SRP Source Check #3Document9 pagesSRP Source Check #3aoleson13No ratings yet

- Art App Module 3Document35 pagesArt App Module 3denjell morilloNo ratings yet

- Art HedgehogDocument4 pagesArt Hedgehogapi-528616712No ratings yet

- International Journal of Education & The ArtsDocument21 pagesInternational Journal of Education & The ArtsAndreia MiguelNo ratings yet

- Patul National High School: Content StandardDocument3 pagesPatul National High School: Content StandardRav De VeneciaNo ratings yet

- Lewis Le Val - Des Fleurs (Of The Flowers) (EMS)Document36 pagesLewis Le Val - Des Fleurs (Of The Flowers) (EMS)Anmut67% (3)

- (Download PDF) Etextbook 978 0073513591 The Art of Critical Reading 4Th Edition Full Chapter PDFDocument53 pages(Download PDF) Etextbook 978 0073513591 The Art of Critical Reading 4Th Edition Full Chapter PDFkaciubobel100% (10)

- 1000 Artists Books PDFDocument321 pages1000 Artists Books PDFcinthya100% (6)

- DadaismDocument9 pagesDadaismtulips7333No ratings yet

- Topic Facilitator:: Julito B. Bande, MAEMDocument27 pagesTopic Facilitator:: Julito B. Bande, MAEMJhoanna Marie BoholNo ratings yet

- 10 Art CrimeDocument18 pages10 Art CrimeHarri Yadi100% (1)

- How I Help My Mother EssayDocument8 pagesHow I Help My Mother Essayfeges1jibej3100% (2)

- Art Description: The Subject Matter AnswersDocument5 pagesArt Description: The Subject Matter AnswersABDULLAH RENDONNo ratings yet

- Mapeh 10 Q4 W2Document9 pagesMapeh 10 Q4 W2benitezednacNo ratings yet

- The Origins of AuraDocument8 pagesThe Origins of AurajimimavsNo ratings yet

- 1179Document26 pages1179Miko F. RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Associate of Fine ArtsDocument2 pagesAssociate of Fine ArtsBobbyNo ratings yet

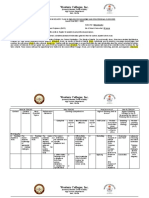

- Western Colleges, Inc.: (Formerly Western Cavite Institute)Document6 pagesWestern Colleges, Inc.: (Formerly Western Cavite Institute)Danica CorderoNo ratings yet

- What The Renaissance Was and Why It Still Matters: Renaissance Primer (1 of 2)Document42 pagesWhat The Renaissance Was and Why It Still Matters: Renaissance Primer (1 of 2)Daniela EfrosNo ratings yet

- Summative Test in Arts - Third GradingDocument2 pagesSummative Test in Arts - Third Gradingmiguela.santiagoNo ratings yet

- African Philosophy in The 21st CenturyDocument158 pagesAfrican Philosophy in The 21st CenturyTerfa Kahaga Anjov100% (5)

- STS ESSAY 3 - Music and Technology PDFDocument1 pageSTS ESSAY 3 - Music and Technology PDFFelix Arthur DiosoNo ratings yet

- Dryden's EssayDocument1 pageDryden's EssayMahbubur RahmanNo ratings yet

- Notes From The Field MaterialityDocument29 pagesNotes From The Field MaterialityGianna Marie AyoraNo ratings yet

- Divali 2014Document68 pagesDivali 2014Kumar MahabirNo ratings yet

- Module 2 - Management Concepts and FundamentalsDocument32 pagesModule 2 - Management Concepts and FundamentalsAdrian GallardoNo ratings yet

- Soto - A Retrospective ExhibitionDocument144 pagesSoto - A Retrospective ExhibitionOdalys Sánchez IINo ratings yet